Abstract

Despite advances in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the overall survival rates for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) have not changed over the last decades. Clearly, novel therapeutic strategies are needed for this cancer, which is highly immunosuppressive. Therefore, biologic therapies able to induce and/or up-regulate antitumor immune responses could represent a complementary approach to conventional treatments. Because patients with SCCHN are frequently immunocompromised due to the elimination or dysfunction of critical effector cells of the immune system, it might be necessary to restore these immune functions to allow for the generation of more effective antitumor host responses. Simultaneously, to prevent tumor escape, it might be necessary to alter attributes of the malignant cells. The present review summarizes recent advances in the field of immunotherapy of SCCHN, including techniques of nonspecific immune stimulation, the use of monoclonal antibodies, advances in adoptive immunotherapy and genetic engineering, as well as anticancer vaccines. These biologic therapies, alone or in combination with conventional treatment, are likely to develop into useful future treatment options for patients with SCCHN.

Keywords: Head neck cancer, Immune suppression, Immunotherapy, Tumor escape

Introduction

The majority of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) present at diagnosis with advanced disease and large primary lesions as well as regional lymph node metastases. Although considerable progress has been made in the refinement of the standard treatment modalities such as surgery and radiotherapy, and despite the introduction of simultaneous radio–chemotherapy, the cure rate for these patients continues to be poor. Therefore, recent research activities have increasingly focused on the exploration of novel treatment strategies, including immunotherapy. Ideally, novel therapies for SCCHN will require tumor-targeted approaches that combine tumor specificity and limited toxicity. Successful immunotherapy of SCCHN is dependent on the identification of suitable tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), which are expressed as a result of oncogenic cell transformation. TAAs are molecules processed and presented by the tumor cell, which are capable of evoking an antitumor host immune reaction, and which are targeted by the tumor-specific effector cells. It would be preferable if TAAs were absolutely restricted to tumor cells. In reality, however, normal cells may express molecules that are very similar or identical to TAAs. Therefore, abnormal cellular distribution or overexpression of cellular proteins rather than their structure characterizes the TAAs expressed by most human malignancies. In general, immunotherapeutic interventions aim to directly or indirectly develop and/or augment immunological responses against such TAAs.

Although significant advances have been made in the development of immune therapies for various cancer types, research on immunotherapy of SCCHN has been limited. On the other hand, there are various indications of interactions between the tumor and the immune system in patients with SCCHN. These tumors are located at or close to mucosal surfaces and are often surrounded by or infiltrated with immune cells. The role of these cells in tumor progression has been debated for many years, but the consensus is that despite the activated phenotype they express, the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in SCCHN are dysfunctional [1, 2]. The tumor is considered to be the major contributor to immune-cell dysfunction, and thus it has become common to refer to this state as tumor-induced immune suppression. The present article briefly reviews the phenomenon of immune suppression in SCCHN patients and subsequently focuses on strategies that could be used to augment antitumor immune responses in these patients.

Immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment

Several distinct mechanisms have been identified which are responsible for the escape of cancer cells from immune recognition. These include expression by tumors of poorly immunogenic antigens, defects in antigen processing, inadequate costimulatory interactions, production of immunosuppressive factors, or the fact that immune cells are compromised in number and/or function. SCCHN are believed to be poorly immunogenic and strongly immunosuppressive [1, 3–7]. This perception is largely based on observations made in the early 1970s that demonstrated the absence of delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTHRs) to recall antigens in patients with advanced SCCHN [8]. More recent data indicate that these patients often have reduced overall numbers of lymphocytes [9], and that in vitro proliferation of these lymphocytes in response to mitogens or antigens is significantly reduced [10]. Although malnutrition and indirect toxic influences of alcohol and tobacco abuse may have deleterious effects on the immune system, there is also evidence that tumor-induced effects or serum factors contribute to a decrease in both local and systemic immune responses in patients with SCCHN. These tumors are known to produce PGE2 [11, 12] which inhibits lymphocyte proliferation [13]. The observation that SCCHN-induced inhibition of peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proliferation could be abrogated by treatment with indomethacin indicates that PGE2 may be responsible for this inhibition [14, 15]. Other immunosuppressive factors implicated in dysfunction of immune cells in patients with SCCHN include polypeptides such as p15E and the cytokines TGF-β, interleukin (IL)-10, and GM-CSF, as well as nitric oxide, all of which have been shown to be produced by SCCHN [5, 16–20]. Soluble factors identified in supernatants of established SCCHN cell lines and in sera from patients with SCCHN have been shown to inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and generation of lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells from peripheral blood lymphocytes, but have yet not been fully characterized [10, 21]. Furthermore, circulating immune complexes were found to be elevated in sera of SCCHN patients and could contribute to immune suppression via down-regulation of natural killer (NK)-cell-mediated tumor lysis [22]. Apoptosis induced in lymphocytes by SCCHN may lead to a degradation of T-cell receptor (TCR)-associated signaling proteins, including the ζ chain [23]. Recent data indicate that membranous microvesicles (MVs) are present in sera of patients with SCCHN and that these MVs contain biologically active FasL which may be involved in mediating lysis of Fas-positive T cells in the peripheral circulation [24]. It has been convincingly demonstrated that SCCHN are able to induce functional defects and apoptosis in immune effector cells as well as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by various mechanisms [7, 25–29]. In addition to decreased numbers of myeloid dendritic cells (MDCs) in the peripheral circulation of patients with SCCHN [26], induction of immunosuppressive immature dentritic cells (DCs) or CD34+ progenitor cells in the presence of tumor has been described in these patients [30–33].

Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck not only actively interfere with cells of the immune system, but they also have developed ways of evasion or “hiding” from the host. These tumors frequently have reduced expression of costimulatory molecules [34], alterations in the MHC class I–associated epitope processing pathway [35], or they down-regulate antigen-presenting molecules [36–38]. By these means, the tumor evades recognition by tumor-specific immune effector cells. In addition, the tumor can modulate expression of antigens on its surface, and antigen-loss variants are a frequent consequence of immune selection.

In view of the well-documented existence of immune suppression and tumor evasion in SCCHN, novel approaches to therapy have to consider local and/or systemic restoration of immune functions and the development of strategies to render tumor cells more immunogenic. While the interactions between SCCHN and immune cells are complex, they suggest that the immune system is involved in the control of tumor growth, and that immunosuppression plays a relevant role in tumor progression. Consequently, therapy of SCCHN with local or systemic agents that restore immune functions appears to be indicated.

Immunotherapeutic strategies

Immunotherapeutic interventions may be classified as active or passive and nonspecific or specific. Active immunotherapy refers to the induction of immune responses through application of immunogenic tumor antigens (e.g., peptides, proteins, tumor cells, or tumor lysates), whereas passive immunization relies on the transfer of immune effector molecules or immune cells. In either mode of immunotherapy, the term “specific” indicates the ability to induce (active) or transfer (passive) tumor antigen-specific molecules (e.g., antibodies [Abs]) or cells (e.g., T cells). Antitumor vaccines represent one form of active-specific immunotherapy, as their intent is to induce vaccine- and tumor-specific T cells in the vaccine recipient. Table 1 lists various forms of immunotherapy and provides examples of clinical trials that have utilized these various immune interventions in patients with SCCHN.

Table 1.

Selected examples of immunotherapies used in clinical trials for patients with SCCHN. The selected clinical studies illustrate the different approaches to immunotherapy of SCCHN. Note that the available strategies have been only sparingly used for therapy of patients with SCCHN, although many have been used in trials designed for patients with other solid tumors

| Immunotherapy | References |

|---|---|

| Active nonspecific | |

| Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) | [21, 41, 42, 44–46] |

| Corynebacterium parvum | [139] |

| Levamisole (antihelminthic imidazole) | [8, 48] |

| Picibanil (OK 432) | [47] |

| Active-specific | |

| DC-based vaccines using autologous apoptotic tumor cells as an antigen source and delivered intranodally | [7] |

| DNA-based vaccines using semiallogeneic SCCHN cells transduced with the IL-2 gene as recipients of tumor-derived DNA | [7] |

| WT p53 peptides pulsed on autologous DC and ultrasound guided delivery to lymph nodes | [140] |

| Multiepitope vaccine using MAGE-A3/HPV16 peptides linked by the furin-sensitive linker RVKR (“Trojan” peptides) delivered with GM-CSF | S. Strome and E. Celis (personal communication, 2003) |

| Alloantigen gene therapy | [134] |

| Vaccine combining autologous tumor cells and IL-12 gene transduced fibroblasts | Tahara et al. (submitted) |

| Passive nonspecific | |

| Cytokines | |

| IL-2 administered perilymphatically | [52, 54, 141, 142] |

| IFN-γ systemic administration | [60, 63, 64, 142] |

| IFN-α systemic administration | [59, 65] |

| IRX-2 peritumoral delivery | [66–68] |

| Cellular adoptive transfer | |

| LAK cells and IL-2 administered locally | [118–120] |

| Passive-specific | |

| Antibodies | |

| Abs targeting EGFR alone | [83, 84] |

| Abs targeting EGFR together with CT/RT | [87] |

| Chimeric anti-EGFR Abs (C225) with CT/RT | [62, 88] |

| Cellular adoptive transfer | |

| T cells specific for the tumor | [121] |

Nonspecific, active immunomodulators

Many different agents have been investigated for the ability to induce active, nonspecific stimulation of the immune system. Among them are preparations containing Trypanosoma cruzi, which have been reported to induce responses in cancer patients, including those with SCCHN [39, 40]. Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) has been used in several randomized clinical trials either alone or as an adjuvant in combination with chemotherapy or surgery in head and neck cancer [41–46]. Although there were reports of increased tumor-free survival and increased overall survival with BCG after curative local therapy [41, 45, 46], conflicting results do not allow for definitive conclusions to be made. Studies of other immunomodulatory agents such as levamisole (an antihelminthic imidazole), thymic extracts or OK-432 (picibanil: a penicillin G–inactivated low-virulence group A Streptococcus pyogenes), have shown some antitumor responses but no benefits in long-term survival [8, 47, 48].

Nonspecific, passive immunotherapy

Cytokine-driven immunotherapy is a nonspecific, passive approach aiming to augment or boost immune cells with antitumor activity. Several cytokines have been used in therapy of SCCHN, as follows.

Interleukin 2

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) directly activates lymphocytes and sustains their proliferation. It has also been reported to be able to directly inhibit growth of SCCHN [49, 50]. Cortesina et al. [51] have obtained three complete responses lasting 5–6 months, three partial responses, seven minor responses, and seven nonresponses after perilymphatic injection of low doses of IL-2 in 20 patients with recurrent SCCHN, recurrence not being open to conventional therapy [52]. However, the observed responses were transient and refractory to repeated treatment. Furthermore, other subsequent studies were unable to reproduce these response rates [53–55]. Nevertheless, mechanistic investigations performed in the course of a phase Ib study with peritumoral injections of IL-2 in SCCHN patients demonstrated increased numbers and activities of both T cells and NK cells infiltrating the tumor stroma [56]. Several subsequent clinical trials have combined systemic IL-2 with interferon (IFN)-α or chemotherapy and achieved various response rates, but the individual contribution of IL-2 to these responses was difficult to determine [53, 57, 58].

Interferon α (IFN-α)

Investigators at the University of Pittsburgh [59, 60] evaluated the relative efficacy of systemic rhIFN-α in patients with SCCHN and observed a complete response rate of about 5%, with some patients achieving a stable disease status. Schrijvers et al. [61] were unable to show any improved response rates or better survival in patients with recurrent SCCHN, when IFN-α was used in a regimen containing fluorouracil and cisplatin. Recently, IFN-α in combination with 13-cis-retinoic acid (cRA) and α-tocopherol was used in an adjuvant phase II chemoprevention trial to prevent recurrence and/or secondary tumors, and it was found to be generally well tolerated [62].

IFN-γ

Interferon γ (IFN-γ) up-regulates expression of several critical cellular molecules, including TAAs, adhesion molecules, and MHC class I and II molecules. Early on, Richtsmeier [4] demonstrated a direct cytotoxic and cell-differentiation effect of IFN-γ on SCCHN cell lines. IFN-γ infusions in subsequent phase I/II clinical studies demonstrated notable responses in advanced SCCHN and induced tumor cell differentiation in several instances [63–65]. However, clinical-grade IFN-γ has not been available for human therapy for several years, and alternative strategies of adoptively transferred genetically modified producer cells had to be used instead. This has hampered the evaluation of the clinical utility of IFN-γ in patients with SCCHN. Recombinant IFN-γ is currently available for therapy, and it will be possible to reevaluate the clinical potential of this cytokine for patients with SCCHN.

Cytokine mixtures

Hadden and colleagues [66–68] have used a complex cytokine mixture (IRX-2) produced by activating normal PBMCs with a mitogen, phytohemagglutinin (PHA), to induce immune regression of SCCHN prior to conventional therapy. In addition to lymphocyte mobilization and robust cellular infiltrations of activated lymphocytes in SCCHN, they demonstrated clinical responses associated with minimal toxic effects. This cytokine mixture remains a promising approach to immunotherapy of SCCHN, and is currently being produced as a GMP therapeutic for additional clinical trials.

Specific, passive immunotherapy by antibody targeting

Antibodies bind to antigenic epitopes expressed by target cells, leading to distinct interactions of the individual cells with their targets or the attraction of NK cells, which mediate Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). The development of hybridoma technology [69] and recent progress in molecular biology has led to the generation of a great variety of biologically and genetically engineered Abs and definition of their specificity, thus initiating a new phase in the passive immunotherapy of malignancies. In particular, the successful production of chimeric and humanized monoclonal Abs (mAbs) has been an important step in avoiding the clinical problems of inducing strong and potentially neutralizing human antimouse Ab responses in patients treated with murine mAbs. For SCCHN, several tumor-associated epitopes were shown to be able to bind mAbs, thus providing a rationale for the possible future use of these Abs in antitumor therapies.

Unconjugated antibodies

Initially, Vlock et al. [70] tested sera of SCCHN patients against SCCHN cell lines and found Ab reactivity in more than 50% of cases. These investigators characterized a 60 kD SCCHN-associated glycoprotein by Western blot analysis [71], but have not performed further structural and functional analyses of this putative TAA. Another interesting SCCHN epitope identified by using Abs is the A9/α6β4 integrin [72, 73]. However, these Abs have never been applied to therapy. A group in Amsterdam has been particularly active in developing mAbs, including the well-known U36 and E48 mAbs, which recognize epitopes on SCCHN and which were evaluated for applications in the diagnosis and treatment of minimal residual disease [61, 74–78].

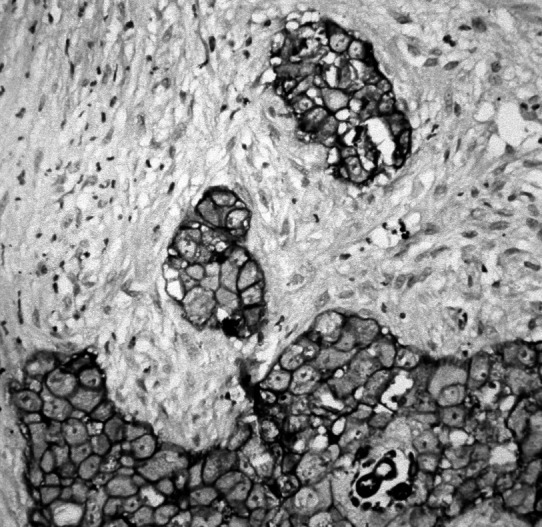

Several investigators studied the utilization of mAbs directed against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a surface antigen frequently overexpressed in SCCHN [79–82]. Clinical studies involved murine, rat, chimeric, and humanized EGFR Abs alone or in combination with standard therapy [83–85]. Furthermore, the chimeric EGFR-specific Ab, C225, was evaluated in phase I clinical trials in combination with cisplatin as well as radiotherapy with only mild toxicity [86–88]. Further studies are currently underway to evaluate the efficacy of anti-EGFR Abs in combination with radiotherapy for treatment of patients with SCCHN (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A representative section of human SCCHN stained for EGFR/erbB-1 protein and showing the characteristic membranous immunostaining. Sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor tissue of 3–5 μm thickness were air-dried, dewaxed, rehydrated, and treated with Pronase E for 15 min at 37°C to enhance immunoreactivity. Staining was performed with a mouse mAb directed against human erbB-1 (TissuGnost anti-EGF-R “P”; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) employing an avidin-biotin–based immunoperoxidase technique

Mechanisms responsible for therapeutic effects of anti-EGFR mAbs or any other antitumor Ab in general include direct cytostatic effects, ADCC mediated by NK cells [89, 90], or induction of apoptosis in SCCHN cells [91].

New technologies based on the use of Abs and on the serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries (SEREX, 110) might lead to the identification of a wide variety of human head and neck cancer antigens recognized by the humoral immune system [92].

Conjugated antibodies

Van Dongen and colleagues [78] developed a number of radioimmunoconjugates directed against TAAs of SCCHN, and tested their feasibility for radioimmunotherapy in preclinical and clinical studies. Among the most promising Abs were murine U36 and BIWA-1, which recognize the keratinocyte-specific CD44 splice variant, epican, with the epitope located in the v6 domain. Expression of v6-containing variants (CD44v6) has been related to aggressive behavior of various tumor types and was shown to be particularly high in SCCHN and, therefore, represented a suitable target for immunotherapy. In a phase I study, radioimmunotherapy with 186Re-labeled-cMAb U36 was well tolerated, with bone marrow toxicity being the dose-limiting factor [93]. Similarly, 99mTc-labeled BIWA-1 showed good specificity and low toxicity in a radioimmunoscintigraphy setting [94]. More recently, chimeric or humanized forms of the Abs have been established and shown to induce human Ab responses comparable to those induced by their murine counterparts [93].

Immunotherapy with conjugated Abs may have a drawback, however. Many immunoconjugates have a poor capacity to penetrate tumor tissues [95, 96]. Because better Ab uptake is generally found in small tumors as compared to larger tumors, radioimmunotherapy may be particularly effective in head and neck cancer patients when used in an adjuvant setting [97].

An interesting approach utilizing Abs has been described by Shibuya et al. [98]. They created surgical sutures coated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 Abs and used them as a potential local immunomodulator, with the goal of helping to attract and stimulate lymphocytes as an adjuvant after tumor ablation.

Specific and nonspecific, active immunotherapy by vaccination

Antitumor vaccines have been increasingly often considered as a promising alternative to conventional therapies. Various forms of therapeutic antitumor vaccines can be considered for SCCHN. Those that induce in vivo generation of nonspecific effector cells such as LAK cells or non-MHC-restricted T lymphocytes generally depend on therapeutic use of cytokines, growth factors, or immunostimulatory agents. By far more common today are tumor-specific vaccines designed to generate T-helper and T-cytotoxic lymphocytes responsive to TAAs.

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are a critical component of the host immune response to human tumors, and induction of strong CTL responses is the goal of most current cancer vaccine strategies. CTLs target tumors through the recognition of a self-MHC class I molecule and an antigenic peptide generally derived from endogenous tumor cell proteins. However, for CTL induction and expansion, the antigenic peptide has to be presented to precursor T cells in the context of costimulatory molecules, usually provided by professional APCs including macrophages or DCs. Delivery of exogenous antigens to the endogenous MHC class I–restricted processing pathway in professional APCs is a critical challenge in cancer vaccine design. Vaccination strategies involving DCs are relatively novel therapeutic modalities, which are currently eligible for clinical use. It has now become feasible to generate larger numbers of human DCs ex vivo and pulse them with antigenic epitopes for delivery to patients with cancer. DCs internalize and process TAAs and cross-present peptides generated from these TAAs on MHC class I molecules to T cells. Upon successful TCR-mediated recognition of these peptides, T cells expand and an antigen-specific CTL response is generated through cross-priming.

However, cross-priming of DCs with tumor-derived epitopes for generation of tumor-specific responses usually requires prior definition, characterization, and the availability of immunogenic and naturally processed epitopes. Although a significant number of TAAs have been described for SCCHN, most are either not tumor-specific or not sufficiently immunogenic to be used as TAAs for targeted immunotherapy. In the absence of well-characterized immunogenic epitopes in SCCHN, DCs coincubated or pulsed with whole tumor cells or various tumor-derived preparations could be used as vaccines. This type of strategy could potentially result in both specific and nonspecific immunization of the host to multiple TAAs, which need not be known or previously characterized.

Defined TAAs of SCCHN as potential targets

In the context of MHC class I molecules, TAAs may serve as a target for specific HLA-restricted cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. Those TAAs could be represented by overexpressed and/or mutated nonfunctioning proteins. However, compared to other human tumors, such as renal cell carcinoma or melanoma, only a few TAAs have been defined in SCCHN, and these include members of the c-erbB family, certain cancer germline antigens or telomerase [7, 80, 92, 99, 100]. These TAAs have been largely used as tumor markers and have not been tested so far for their potential as immunogens. While most tumor markers in SCCHN are antigenic, few are known to be immunogenic. Those that qualify are described below.

Tumor-suppressor gene product p53

One of the most abundantly expressed TAAs in SCCHN is the mutated tumor suppressor gene product, p53. Recently, it has been determined that the gene encoding p53 protein is mutated in 80% of SCCHN [101], which often results in accumulation (“overexpression”) of p53 molecules in these tumors. The accumulated p53 has been considered as an attractive candidate for vaccines potentially capable of inducing antitumor immune responses. Initially, individual p53 missense mutations, which are tumor-specific in nature, were considered as the most promising candidates for vaccines. Such vaccines, however, would have limited clinical usefulness, because they require that the p53 mutation occurs within, or creates, an epitope which could be presented by the MHC class I molecules expressed by the individual patient [102, 103]. In this case, a custom-made vaccine would have to be produced for each patient. As most of the p53 mutations involve an alteration of a single amino acid in overexpressed p53 molecules, most of the accumulating mutant protein resembles the wild-type (WT) p53. Enhanced presentation of WT epitopes derived from p53 molecules accumulating in tumors is therefore possible and might lead to their recognition by the immune system and the development of CTLs [102, 104–107]. We and others have shown that MHC class I–restricted WT p53 epitopes presented on DCs can induce CTLs ex vivo from precursors present in the PBMCs of normal donors or patients with SCCHN. The ability to induce CTLs recognizing WT p53 epitopes has established a basis for future development of a broadly applicable p53-based immunotherapy.

Today, WT p53 epitopes are considered attractive targets for immunotherapy of cancer. The two HLA-A2.1–restricted, human WT p53 epitopes that have been most often used in these studies are p53149-157 and p53264-272. We have previously reported on the generation of CTLs recognizing the WT p53264-272 epitope from PBMCs obtained from patients with SCCHN [105]. Surprisingly, we observed that CTLs reactive against this WT p53 epitope could only be generated from T-cell precursors in PBMCs of patients whose tumors either did not accumulate p53 or accumulated p53 but could not present this epitope [105]. In contrast, lymphocytes of the patients whose tumors accumulated p53 were tolerant against the p53264-272 epitope. To explain these observations, we hypothesized that in vivo, the presence of proliferating CTL precursors specific for the wt p53264-272 epitope leads to immunoselection, manifested by the elimination of tumors expressing the epitope and favoring the outgrowth of “epitope-loss” tumor cells able to evade the host immune system. This hypothesis has been recently confirmed by testing the precursor frequencies of p53-specific T cells in patients with SCCHN in vivo [108]. The use of tetramers made with the WT p53264-272 peptide showed that contrary to expectations, patients with tumors overexpressing mutated p53 had the lowest frequency of tetramer-positive T cells, while patients with tumors expressing WT p53 had high frequencies of such T cells [109]. This suggests that in the presence of immune effector cells, the tumor fails to overexpress p53 and becomes resistant (“hides”) to these T cells or that the tumor-specific T cells do not recognize the epitope. Strategies that might help to overcome tumor resistance or lymphocyte inability to see the “hidden” WT p53264-272 epitope include the use of altered peptide ligands (APLs) derived from WT p53264-272 [110], identification of other WT p53 epitopes which might be more immunogenic than p53264-272 as well as MHC class II–restricted epitopes to provide help for generation of antitumor effector cells [111].

Cyclin B1

Dysregulation of the cell cycle is one of the hallmarks of human cancer and, recently, peptides derived from cyclin B1 were shown to be immunogenic in an experimental SCCHN model [99]. In addition, we were able to detect memory T cells specific for cyclin B1 peptides in patients with SCCHN, and these T cells could kill tumor cell lines overexpressing cyclin B1. Further studies are in progress to test the potential of cyclin B1 to induce CTLs in an in vivo vaccination setting.

Caspase 8

Van der Bruggen and collaborators [112] identified an HLA-B×3503–restricted epitope recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human SCCHN. The antigen was encoded by a mutated form of the CASP-8 gene coding for a protease, caspase-8, which is required for induction of apoptosis through the Fas receptor and tumor necrosis factor receptor-1.

SART-1

SART-1–associated peptides with HLA-A2601 restriction were described to be immunogenic in SCCHN cell lines [113]. The HLA-A26 allele is most frequent among Japanese but is also found among Caucasians and Africans, thus potentially offering a tool for specific immunotherapy to a relatively large number of patients.

Carcinoembryonic antigen

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is an oncofetal glycoprotein generally overexpressed in gastrointestinal carcinomas. Recently, expression of CEA has been demonstrated in the majority of tested SCCHN [114]. Furthermore, reactivity of CEA-specific CTLs against CEA-expressing carcinoma cell lines derived from the head and neck has been confirmed, suggesting that CEA or its immunogenic epitopes could be considered as possible targets for specific immunotherapy of SCCHN.

Cancer-testis antigens

During the last decade, the aberrant expression of normal testicular proteins in neoplastically transformed cells became apparent. Cancer-testis antigens (CTAs) represent novel families of genes like MAGE, BAGE, GAGE, LAGE, and NY-ESO-1. About 50% of SCCHN were shown to express at least one MAGE gene at the protein level [100, 115], and HLA-A24–restricted peptides derived from this protein are known to be immunogenic in that after presentation on DCs, CTLs are able to recognize and kill MAGE+ SCCHN targets ex vivo [116].

In addition to the TAAs described above, various other specifically expressed or overexpressed and mutated gene products are found in SCCHN. However, their potential to serve as immunogens for vaccination has to await further studies. Vaccination trials similar to those ongoing in patients with melanoma are lagging behind in SCCHN. None of the above described TAA has been so far used in a vaccine. This may be largely due to two reasons. One is that no suitable animal models of SCCHN exist to support modeling of vaccines and their effects. The second is related to the immunosuppressive nature of these tumors, resulting in a concern that therapeutic vaccines may not be effective in this setting. Because of this concern, future clinical trials in patients with SCCHN should be prepared for the possibility that SCCHN are or might become resistant to specific CTLs or that T cells may be unresponsive to a selected vaccinating epitope. The use of multiple epitopes of the same TAAs, application of multiple TAAs (a cocktail of epitopes), and/or of APLs may offer alternative strategies to be considered in a design of vaccines for patients with SCCHN.

Apoptotic SCCHN as vaccines

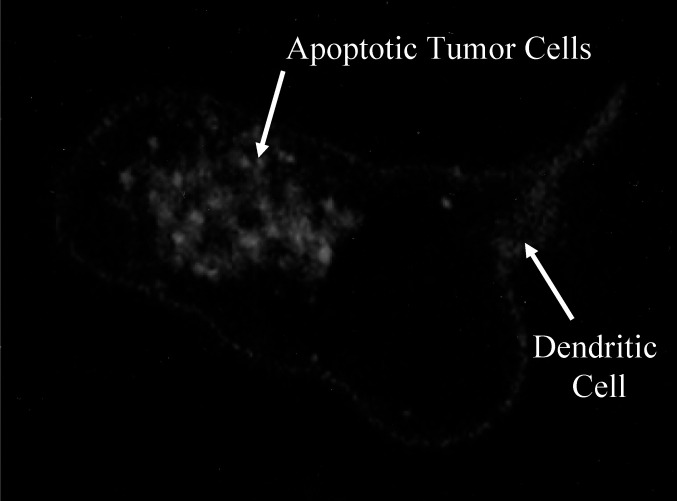

One alternative strategy already in clinical trials is the use of whole tumor cells as a vaccine. In this approach, DCs generated from the patient’s own PBMCs plus whole autologous UVB-irradiated tumor cells are used as a vaccine. Preclinical studies indicated that such a vaccine is effective in inducing robust antitumor immune responses [108]. Subsequently, a phase I clinical trial was initiated and is ongoing at the Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, PA, United States, to test safety and feasibility of such tumor vaccines in patients with advanced SCCHN. A similar clinical trial is in progress at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. These therapeutic apoptotic tumor-based vaccines are expected to show that immune response directed at the tumor can be generated in patients with advanced SCCHN without adverse effects (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Up-take of apoptotic human SCCHN cells by monocyte-derived DCs cultured in IL-4 and GM-CSF. Tumor cells were stained with (DiOC16; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) before induction of apoptosis (UVB irradiation) and cocultured with monocyte-derived (IL-4 and GM-CSF) DCs on glass coverslips. After overnight incubation, attached cells were stained with an anti-CD80 Ab (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) in combination with a rabbit antimouse Cy3-conjugated secondary Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, PA, USA). Apoptotic SCCHN were detected inside DCs by confocal laser scanning microscopy (mid plane image)

Passive specific immunization by adoptive therapy

The cellular approach of adoptive immunotherapy involves ex vivo sensitization or activation of autologous or allogeneic cells to endow them with antitumor activity, followed by infusion/injection of these cells into the patient. Adoptive immunotherapy may be specific or nonspecific, depending on the nature of cells passively transferred to patients.

The use of in vitro–expanded LAK has received considerable attention in SCCHN. LAK cells are generated from peripheral blood cells using high-dose IL-2 in culture. Such cells comprise a heterogeneous population of NK and T cells. Iwaka et al. [117] administered autologous LAK cells to four patients with carcinoma of the maxillary sinus by direct arterial infusion and documented a decrease in tumor volume as well as an increase in lymphocytic infiltration of the tumor. Ishikawa et al. [118]) have performed a clinical trial in head and neck cancer patients, using lymphocytes which were activated in mixed lymphocyte tumor cell culture (MLTC) in the presence of IL-2. They described a reduction in tumor size of the primary tumor as well as pulmonary metastases in a significant subset of patients (7/16). In a phase I trial of IL-2-LAK therapy in SCCHN patients performed by Squadrelli-Saraceno et al. [119], ten local injections of rhIL-2 were combined with an injection of autologous LAK cells on day 1. In this trial, six partial or minimal responses were observed in 14 patients. Kubota et al. [120] used a streptococcal preparation (OK-432) instead of IL-2 to stimulate PBMCs and then adoptively transferred these cells to 19 patients with head and neck cancer either alone or in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. There were no significant adverse effects observed. To et al. [121] performed a phase I study, in which irradiated autologous tumor cells were administered to the thigh, followed by the delivery of GM-CSF. After 8–10 days, inguinal lymph nodes draining the vaccination site were resected, the lymph node lymphocytes were activated in the presence of staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA), expanded and infused into the patients. The infusions were well tolerated and induced stabilization of previously progressive disease in some patients.

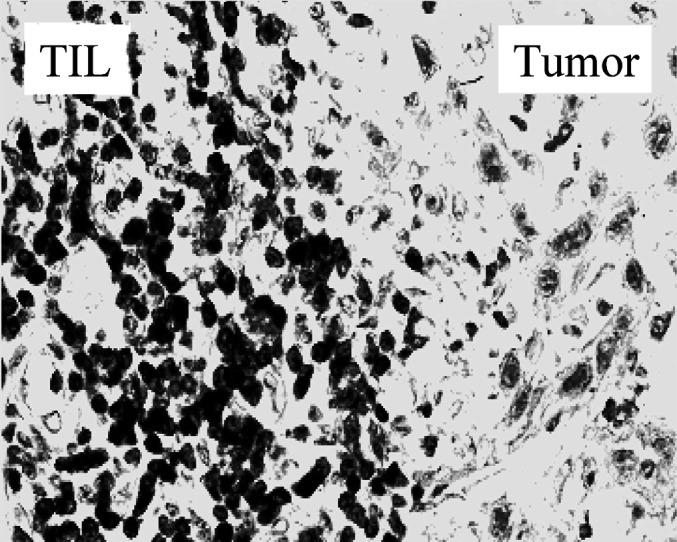

Adoptive therapy with TILs has not been extensively evaluated in SCCHN, largely because TILs isolated from SCCHN were found to be impaired in their proliferative responses and had depressed cytotoxicity against autologous and allogeneic tumor-target cells, when compared with peripheral blood lymphocytes [122–124]. However, SCCHN are generally well infiltrated by T cells (Fig. 3), and it has been suggested that these TILs are a good source of tumor-specific effector cells [123]. It appears that decreased functional activity of TILs could be partially reversed by incubation of these cells with IL-2 [125], and Hald et al. [126] reported some promising results, using TILs in an autologous in vitro setting.

Fig. 3.

A cryosection of human SCCHN immunostained with an anti-CD3 Ab, showing an extensive accumulation of CD3+ T lymphocytes at the tumor site. Immunoperoxidase staining, ×400

Overall, passive transfers of tumor reactive or tumor-specific antitumor effector cells remains one of the most interesting experimental therapies, which has been limited in its application by considerable practical difficulties in ex vivo generation of tumor-specific effector T cells and their transfer in a sufficient number to patients with SCCHN.

Gene therapy for cancer

Genetic immunization refers to treatment strategies utilizing gene transfer methods to generate immune responses against cancer. Several strategies have been developed aimed at modification of tumor cells to make them more immunogenic. For example, genetically engineered tumor cells expressing immune stimulatory genes can be administered as tumor vaccines in an attempt to up-regulate host defense against cancer. Genes encoding cytokines, including IL-2 [127–129], IL-4 [130], GM-CSF, or costimulatory molecules like B7 [131–133] have been transferred into SCCHN and the ability of genetically modified tumor cells to activate the immune cells determined in ex vivo experiments. The difficulty of this approach involves the requirement for culturing of tumor cells for implementation of genetic manipulations. As this is very difficult in SCCHN, an alternative approach of injecting selected genes directly to the tumor in situ has been introduced. For example, Gleich [134] injected genes for HLA-B7 and β2-microglobulin into SCCHN lesions in order to restore expression of the complete MHC class I molecules on the tumor cell surface and thus facilitate both recognition by tumor-specific immune effector cells and antigen presentation by the tumor. In this trial including 20 patients, two complete responses were observed and the median survival of the treated patients was prolonged [134]. In another approach, Tahara et al. (submitted) used gene therapy to deliver a vaccine intratumorally, containing autologous irradiated tumor cells admixed with autologous fibroblasts which were genetically modified with the IL-12 gene and secreted IL-12. These two examples emphasize the concept of therapy aimed at inducing changes in the tumor microenvironment in order to promote tumor demise and enhance antitumor effects of immune cells.

Another possibility is the transfer of tumor-associated genes to professional APCs such as DCs. In ex vivo studies, Nikitina et al. [135] stimulated T cells obtained from SCCHN patients with DCs transduced with an adenovirus WT p53 (Ad-p53) construct. This stimulation resulted in the generation of CTLs specific for p53-derived peptide. So far, however, this approach has not been translated into clinical protocols for patients with SCCHN.

Therapies designed to protect T cells and prevent tumor escape

Increased awareness of immune suppression and of the mechanisms resulting in tumor escape in patients with SCCHN has created an opportunity for the development of a completely novel strategy for biotherapy of these tumors. The strategy is based on the preclinical data demonstrating that: (1) Th2 skewing or polarization of cellular responses can be reversed to Th1 by the use DC1, which are matured in the presence of the modified cocktail of cytokines, including IFN-α and IFN-γ, and produce increased levels of IL-12 [136, 137]; (2) the generation and survival of tumor-specific T cells is prolonged in the presence of survival factors such as IL-7, IL-12, and IL-15 [2]; and (3) antigen-processing machinery (APM) in tumor cells can be altered by cytokines such as IFN-γ to allow for enhanced presentation of MHC molecules and epitopes recognized by immune cells [138]. These recent findings have focused attention on the fact that administration to patients with cancer of immune therapies with the purpose of activating tumor-specific immune cells is not sufficient. Instead, it might be necessary to consider counterbalancing tumor-induced effects and depolarizing immune responses toward the desirable Th1 and maintaining this type of response for a considerable time. Consequently, future biologic therapies might combine approaches optimizing antigen processing and presentation, favoring Th1-type of immune response, and prolonging survival of tumor-specific effector cells.

Conclusions

Advances in monitoring of immunological responses and the use of modern technology to generate well-characterized biologic products capable of up-regulating host antitumor defenses provide a measure of confidence that immunotherapy could be effectively used in the treatment of SCCHN. Best results will probably come from a combination of standard treatment options with immunotherapy, and the role of tumor-specific immunotherapy in the prevention of recurrence or metastasis as well as treatment of the minimal residual disease is likely to become more prominent. Although immunotherapy has yet to become a standard form of treatment for SCCHN, basic research has uncovered the complex and fascinating immunobiology of this tumor. The experimental clinical trials with immunologic agents performed to date in SCCHN should be followed by additional clinical studies designed to eliminate tumor escape and optimize antitumor functions as well as survival of immune cells. These trials will be able to take full advantage of new scientific insights and test new hypotheses. It is hoped that the new generation of upcoming clinical trials will creatively apply some of these insights to therapy of patients with SCCHN.

References

- 1.Reichert J Immunother. 1998;21:295. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteside Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:43. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadden Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:629. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(97)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richtsmeier Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:432. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860160076025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteside Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:175. doi: 10.1007/s002620050476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiteside Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:346. doi: 10.1007/s002620050585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteside Curr Oncol Rep. 2001;3:46. doi: 10.1007/s11912-001-0042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanebo Recent Results Cancer Res. 1978;68:324. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-81332-0_49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuss J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:S45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice Scand J Immunol. 1992;36:443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berlinger Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyderman Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:189. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maca Immunopharmacology. 1983;6:267. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(83)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaPointe Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:149. doi: 10.1177/019459989210600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanebo Cancer. 1988;61:462. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880201)61:3<462::aid-cncr2820610310>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J Immunol. 1995;155:2240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosbe Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:541. doi: 10.1177/019459989511300504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simons Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;38:178. doi: 10.1007/s002620050052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:251. doi: 10.1177/019459988709600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young Int J Cancer. 1996;67:333. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960729)67:3<333::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bugis Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;31:176. doi: 10.1007/BF01744733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schantz Cancer Res. 1990;50:4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gastman Blood. 2000;95:2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Immunother. 2003;26:S44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann Clin Cancer Research. 2002;8:2553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann Cancer Res. 2002;8:1787. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichert Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tas Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1993;36:108. doi: 10.1007/BF01754410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almand Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almand J Immunol. 2001;166:678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lathers Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:205. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.117871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pak Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:95. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lang Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:82. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vora Br J Cancer. 1997;76:836. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grandis Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hicklin Mol Med Today. 1999;5:178. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seliger Tissue Antigens. 2001;57:39. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057001039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clyuyeva NG, Roskin GI (1963) Biotherapy of malignant tumours. Pergamon, Oxford

- 40.Coudert Antibiotiki. 1961;2:99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amiel Recent Results Cancer Res. 1979;68:318. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-81332-0_48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bier Immunotherapy. 1981;12:71. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng Cancer. 1982;49:239. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820115)49:2<239::aid-cncr2820490208>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donaldson Am J Surg. 1973;126:507. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(73)80040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richman Cancer Treatment Rep. 1976;60:535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:544. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800220050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kitahara J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:449. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100133948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olivari Cancer Treatment Rep. 1979;63:983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rabinowich J Immunol. 1992;149:340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sacchi Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:321. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870150089012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cortesina Cancer. 1988;62:2482. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881215)62:12<2482::aid-cncr2820621205>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cortesina Head Neck. 1991;13:125. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880130208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantovani Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;47:149. doi: 10.1007/s002620050515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mattjijssen J Immunother. 1991;10:63. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vlock J Immunother. 1994;15:134. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whiteside Cancer Res. 1993;53:5654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urba Cancer. 1993;71:2326. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930401)71:7<2326::aid-cncr2820710725>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valone J Immunother. 1991;10:207. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwala Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1991;10:205. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vlock Head Neck. 1991;13:15. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schrijvers J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1054. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shin J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ikic Lancet. 1981;1:1025. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(81)92189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Medenica Cancer Drug Deliv. 1985;2:53. doi: 10.1089/cdd.1985.2.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richtsmeier Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:1271. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870110043004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barrera Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:345. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meneses Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verastegui Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:619. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(97)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kohler Nature. 1975;256:495. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vlock Cancer Res. 1989;49:1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vlock Biochem Biophys Acta. 1993;1181:174. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(93)90108-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kimmel Cancer Res. 1986;46:3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Cancer Res. 1991;51:2395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brakenhoff Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;40:191. doi: 10.1007/s002620050162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quak Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:181. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870020057015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Quak Hybridoma. 1990;9:377. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1990.9.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Int J Cancer. 1996;68:520. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961115)68:4<520::AID-IJC19>3.3.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bergler Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1989;246:121. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bier Excerpta Medica Int Congress Ser. 1996;1114:225. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Christensen Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1992;249:243. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grandis Cancer. 1996;78:1284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960915)78:6<1284::AID-CNCR17>3.3.CO;2-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bier Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;252:433. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bier Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;47:519. doi: 10.1007/s002800000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Modjtahedi Br J Cancer. 1996;73:228. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baselga J Clin Oncol. 2000;8:904. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robert J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shin Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bier Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:167. doi: 10.1007/s002620050475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sung Int J Cancer. 1995;61:1. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Modjtahedi Int J Oncol. 1998;13:335. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monji Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:734. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Colnot Head Neck. 2001;23:559. doi: 10.1002/hed.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stroomer Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dvorak Cancer Cells. 1991;3:77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shockley Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;618:367. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb27257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:1562. doi: 10.1007/s002590050336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shibuya Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:1229. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.11.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kao J Exp Med. 2001;194:1313. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kienstra Head Neck. 2003;25:457. doi: 10.1002/hed.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Balz Cancer Res. 2003;63:1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.DeLeo Crit Rev Immunol. 1998;18:29. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v18.i1-2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Offringa Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;910:223. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chikamatsu Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hoffmann J Immunol. 2000;165:5938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Röpke Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Soussi Immunol Today. 1996;17:353. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)30019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hoffmann Cancer Res. 2000;60:3542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hoffmann Cancer Res. 2002;62:3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hoffmann J Immunol. 2002;168:1338. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chikamatsu Cancer Res. 2003;63:3675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mandruzzato J Exp Med. 1997;186:785. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shichijo J Exp Med. 1998;187:277. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kass Cancer Res. 2002;62:5049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Eura Int J Cancer. 1995;64:304. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Katsura Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:117. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyd030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iwaka Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1989;16:1438. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ishikawa Acta Otolaryngol. 1989;107:346. doi: 10.3109/00016488909127519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Squadrelli-Saraceno Tumori. 1990;76:566. doi: 10.1177/030089169007600611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kubota J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21:30. [Google Scholar]

- 121.To Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:1225. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.10.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Letessier Cell Immunol. 1990;130:446. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90286-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Whiteside Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1988;26:1. doi: 10.1007/BF00199840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yasumura Cancer Res. 1993;53:1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Boscia Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988;97:414. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hald Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;41:243. doi: 10.1007/s002620050224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lin Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:1229. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880230075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.O’Malley Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:667. doi: 10.1210/me.11.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wollenberg Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:141. doi: 10.1089/10430349950019273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Myers Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:127. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Day Laryngoscope. 2001;111:801. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lang Anticancer Res. 1999;19:5335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Qiu Cancer Lett. 2002;182:147. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gleich Laryngoscope. 2000;110:708. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nikitina Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mailliard J Exp Med. 2002;195:473. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tatsumi J Exp Med. 2002;196:619. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Seliger Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:3. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vogl Cancer. 1982;50:2295. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821201)50:11<2295::aid-cncr2820501113>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ferris RL, DeLeo AB, Whiteside TL (2003) Adjuvant p53 peptide loaded DC-based therapy of subjects with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (a phase I safety and immunogenicity trial). UPCI Protocol, Pittsburgh

- 141.De J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:125. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Vlock J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:433. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gerretsen Oral Oncol. 1994;30B:82. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Schrijvers Cancer Res. 1993;53:4383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tureci Cancer Res. 1996;56:4766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]