Abstract

Because of the central role of CD4+ T cells in antitumour immunity, the identification of the MHC class II–restricted peptides to which CD4+ T cells respond has become a priority of tumour immunologists. Here, we describe a strategy permitting us to rapidly determine the immunogenicity of candidate HLA-DR–restricted peptides using peptide immunisation of HLA-DR–transgenic mice, followed by assessment of the response in vitro. This strategy was successfully applied to the reported haemaglutinin influenza peptide HA(307–319), and then extended to three candidate HLA-DR–restricted p53 peptides predicted by the evidence-based algorithm SYFPEITHI to bind to HLA-DRβ1*0101 (HLA-DR1) and HLA-DRβ1*0401 (HLA-DR4) molecules. One of these peptides, p53(108–122), consistently induced responses in HLA-DR1– and in HLA-DR4–transgenic mice. Moreover, this peptide was naturally processed by dendritic cells (DCs), and induced specific proliferation in the splenocytes of mice immunised with p53 cDNA, demonstrating that immune responses could be naturally mounted to the peptide. Furthermore, p53(108–122) peptide was also immunogenic in HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 healthy donors. Thus, the use of this transgenic model permitted the identification of a novel HLA-DR–restricted epitope from p53 and constitutes an attractive approach for the rapid identification of novel immunogenic MHC class II–restricted peptides from tumour antigens, which can ultimately be incorporated in immunotherapeutic protocols.

Keywords: Cancer immunotherapy, CD4+ T cells, HLA-DR–transgenic mice, MHC class II–binding peptide, p53

Introduction

CD4+ T cells have long been known to provide help for the development and maintenance of antitumour cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [21]. Most vaccination strategies take into account this necessity by incorporating either potent helper epitopes or proteins and/or by stimulating the immune system with strong immune danger signals like adjuvants or recombinant microbial products [20]. However, recent evidence both in mice and in humans has demonstrated that antitumour CD4+ T cells are likely to play an active role in the eradication of tumour cells [6, 7]. The mechanism of action of such antitumour CD4+ T cells is yet to be fully understood, but is likely to involve indirect cytotoxic mechanisms via the recruitment of “accessory” cells of the innate immune system at the tumour site [6]. As a consequence, the characterisation of MHC class II–restricted peptides to which antitumour CD4+ T cells respond is essential to dissect the precise role of these cells in antitumour immunity and for the incorporation of these peptides in cancer vaccines.

Several strategies have been developed in order to identify novel tumour-associated T-helper (Th) epitopes. Peptide elution from MHC class II molecules followed by mass spectrometry analysis and other elegant direct approaches based on the definition of the antigen recognised by CD4+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes have been successful in the definition of novel Th epitopes and antigens [10, 28, 29]. However, these techniques require equipment, techniques and expertise, which are not readily available in every laboratory. Therefore, most studies have used “reverse immunology” to identify MHC class II–restricted epitopes. This approach consists in screening the antigen for peptides displaying a binding motif for the HLA allele of interest, and generating T cell lines specific to these peptides in vitro from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Although most Th epitopes from tumour-associated antigens have been identified by this approach, it is usually a very long and labour-intensive procedure. Therefore, we sought to develop a more rapid screening procedure for determining the immunogenicity of HLA-DR–restricted candidate peptides using peptide-immunised HLA-DR–transgenic mice. Others have used similar approaches and identified immunogenic peptides from the tumour antigens NY-ESO-1, TRP-1 and gp100, following immunisation with purified antigens or cDNA encoding for the antigen, hence demonstrating its feasibility [25, 26, 30].

It is likely that immunisation of inbred HLA-DR–transgenic mice with candidate peptides will produce responses more frequently and consistently than multiple rounds of in vitro stimulation of human T cells. From this hypothesis, it was decided to predict HLA-DRβ1*0101 (DR1)– and HLA-DRβ1*0401 (DR4)–restricted peptides from the tumour suppressor gene p53, using the evidence-based algorithm SYFPEITHI [22] available on the World Wide Web (http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/uni/kxi), and to submit these peptides to immunogenicity analysis using HLA-DR transgenic mice. This algorithm has previously been successfully used to describe novel immunoreactive MHC class I [15] and class II ligands [14, 18].

The tumour suppressor gene p53 is mutated in 50–60% of human cancers, and can result in the stabilisation and accumulation of the inactive protein within the cancer cell [11]. Such over-expressed proteins can represent targets for the eradication of tumour cells. Indeed, not only have anti-p53 CTLs been observed in healthy donors and patients [9, 16, 19, 23], but anti-p53 antibodies can also be detected in patients [24, 27], indicating that anti-p53 CD4+ T cells responsive to p53 class II epitopes are generated. In addition, recent studies have described the generation of a CD4+ T cell line specific to p53 in patients [5]. Another study has also illustrated the existence of p53-specific Th cells by testing the responsiveness of patients’ T cells to a mixture of wild-type overlapping peptides [27]. In the present study, we have used a transgenic model for detecting immunogenic p53 HLA-DR–restricted peptides. This permitted the identification of a novel HLA-DR1– and HLA-DR4–restricted Th epitope which is naturally processed. In vitro peptide sensitisation of HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 human PBMCs from healthy donors confirmed the immunogenicity of the p53 Th epitope in man. Collectively these data demonstrated the validity of HLA-DR–transgenic mice for the rapid discovery of novel Th epitopes from tumour antigens, which can be incorporated into cancer vaccines in the future.

Materials and methods

Animals

FVB/N-DR1 mice [2] were received from Dr Altmann (MRC Clinical Sciences Centre, London) and C57BL/6-DR4 mice [13] were purchased from Taconic (USA). Colonies were bred at the Nottingham Trent University animal facility in accordance with the Home Office Codes of Practice for the housing and care of animals. HLA-DR expression was demonstrated by flow cytometry, and PCR genotyping confirmed the expression of the alleles of interest: DR1 in FVB/N-DR1 and DR4 in C57BL/6-DR4.

Peptides and immunisation

Peptides from the wild-type sequence of p53 (accession number: P04637) were selected according to their ability to bind to HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 (Table 1) as predicted by the evidence-based algorithm SYFPEITHI and synthesised by Alta Biosciences (Birmingham, UK). The influenza haemaglutinin peptide HA(307) was synthesised at the University of Nottingham. Mice were immunised twice at a 1-week interval at the base of the tail with 100 μg of peptide emulsified 1:1 in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) (Sigma, UK). For DNA vaccination, gold particles were coated with 3 μg of plasmid containing the full length cDNA encoding for p53 bearing a mutation R→H in position 273 (gift from Prof. Soussi, Marie Curie, Paris, France), and FVB/N-DR1 mice were immunised three times at 1-week intervals with a gene gun.

Table 1.

Scores for HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 binding as predicted by SYFPEITHI algorithm and sequences of the peptides used in this study. Predicted peptide core sequence is in bold

| Peptide | Sequence | DR1 score | DR4 score |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA(307–319) | PKYVKQNTLKLAT | 34 | 22 |

| p53(29–43) | NNVLSPLPSQAMDDL | 30 | 26 |

| p53(63–77) | APRMEPAAPPVAPAP | 22 | 20 |

| p53(108–122) | GFRLGFLHSGTAKSV | 31 | 26 |

Western-blotting

SaOs-2 (5–10×105) cells were lysed, spun down at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. Protein assays were performed on the samples using the Biorad DC protein assay kit (Biorad), and 10 μg of total protein was loaded per lane on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Protein were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and the membranes were blocked for 2–3 h with 5% milk in TBS + 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) at room temperature under constant agitation. Membranes were then probed overnight at 4°C with antihuman p53 (DO-7) antibody purchased from Pharmingen diluted 1:1,000 in 5% milk TBS-T. Following four washes in TBS-T, membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with goat antimouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase. Membranes were then washed four times and revealed using the ECL kit (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bone marrow–derived dendritic cell (BM-DC) generation

Bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BM-DCs) were generated as described by Inaba et al. [12] with modifications [1]. Briefly, marrow cells obtained from mouse hind limbs were cultured at 1×106 per well in 1 ml of complete BM-DC media (RPMI + 5% FCS + 10 mM HEPES buffer + 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol + 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin + 0.25 μg/ml fungizone supplemented with 10% of X-63 cell line supernatant producing murine GM-SCF equivalent to 10 ng/ml as measured by ELISA). On day 2 and 4, nonadherent cells were removed by a gentle wash with 700 μl of the media contained in the well. Wells were then replenished with 750 μl of fresh complete BM-DC media. On day 7, cells were prepared for antigen presentation.

BM-DC preparation for antigen presentation

On day 7 of culture, BM-DCs were replated in 24-well plates at a density of 0.5×106/well/ml in complete BM-DC media containing 10 μg/ml of peptide and 1 μg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma) to induce maturation. On day 8, mature BM-DCs were further pulsed with 10 μg/ml of peptide for 4–6 h at 37°C. Cells were washed twice and used as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) at a concentration of 5×103 cells per well in proliferation assays and at 5×104 cells per well in 48-well plates for cytokine measurements. For the presentation of tumour cell lysate, BM-DCs were pulsed on day 8 for 6 h with 100 μg of tumour lysate and 10 μg of mouse antihuman p53 monoclonal antibody HO-7 (gift from Prof. Soussi, Marie Curie, Paris, France), washed twice and used at the same concentration as above. Lysates were prepared by water lysis of >5×107 tumour cells for 5 min at 4°C under constant agitation, followed by 30 s vortexing and centrifugation for 30 min at 14,000 g. Supernants were then collected and assessed for protein content using the Biorad DC protein assay kit (Biorad). p53 Content of the lysate was verified by Western blotting.

In vitro peptide restimulation of splenocytes

Spleens from immunised animals were collected and processed as described previously [1]. Splenocytes were plated in 24-well plates in T-cell media (RPMI + 10% FCS + 20 mM HEPES buffer + 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol + 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin + 0.25 μg/ml fungizone) with 10 μg/ml of peptide at a density of 2.5×106/ml for FVB/N-DR1 or 3.5×106/ml for C57BL/6-DR4. To measure cytokine production, culture supernatants were collected on day 2 and 5, and stored at −20°C until analysed by ELISA. When cells were cultured for more than a week, CD8-depleted splenocytes (1–1.5×106/ml) were restimulated either with peptide-pulsed BM-DCs (1×105/ml) or mitomycin C–treated syngeneic splenocytes (1–1.5×106/ml). For cytokine measurements, CD8-depleted splenocytes were cocultured in 48-well plates at 5×105 cells/well with 5×104 BM-DCs/well. Supernatant were collected after 72 h of culture. Anti-HLA-DR antibody L243 (purified from culture supernatant, HB55; ATCC) and its isotype-matched antibody (mouse IgG2a, azide free; Pharmingen) were added at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml.

Murine proliferation assays

Splenocytes from peptide-immunised mice were depleted from CD8+ T cells after 6 days of in vitro culture using the mouse CD8 dynabeads (Dynal) and according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Preparations were shown to be typically 98% free of CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. CD8-depleted splenocytes were used as responder cells in proliferation assays performed at a density of 5×104 cells per well. Typically cells were cocultured with 5×103 BM-DCs either pulsed with the relevant or an immunogenic HLA-DR–restricted irrelevant peptide in quadruplicates in round-bottom 96-well plates. Blocking of the response with 2 μg/ml of the anti-HLA-DR antibody L243 was systematically performed. An isotype-matched antibody for L243 clone (mouse IgG2a) was also incorporated in these assays at the same concentration. Cultures were incubated for approximately 60 h at 37°C, and [3H]-thymidine was added at 37 kBq/well in the last 18 h of incubation. Plates were harvested onto 96 Uni/Filter plates (Packard), the scintillation liquid (Microscint 0; Packard) was added and the plates were counted on a Top-Count counter (Packard). Results are expressed in counts per minute (cpm) and as means of the quadruplicate wells. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test.

Generation of peptide-specific T cells from healthy donors

Heparinised blood was obtained from consenting HLA-DR1 or HLA-DR4 donors, and PBMCs were isolated using standard gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep (PAA). DRβ1 allele expression was ascertained using Dynal classic SSP kit for DRβ1*01 and DRβ1*04 (Dynal) and according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Dendritic cells were generated as previously described [17]. Briefly, after two rounds of adherence, monocyte-enriched PBMCs were cultured for 5 days with 1,000 U/ml of rhGM-CSF and 500 U/ml of rhIL-4. Nonadherent cells were frozen for use as effector cells in the generation of peptide-specific T cells. On day 6, immature DCs were harvested and replated at 5×105/well in 24-well plates with the same concentration of GM-SCF and IL-4, plus 10 ng/ml of TNF-α and 50 μg/ml of peptide. On day 7, 12.5 μg/ml of poly IC (Sigma) was added to the DCs to induce complete maturation overnight. On day 8, DCs were harvested, washed in CD4+ T cell media (RPMI + 17% AIM-V + 20 mM HEPES buffer + 1% nonessential amino acids + 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin + either 1% autologous serum or 5% AB serum), and pulsed with 10 μg/ml of peptide. Autologous nonadherent cells were thawed, and cocultured with DCs at a concentration of 1×106/ml together with 10 ng/ml of rhIL-7 (ratio, 5–10 T cells to 1 DC). In some experiments CD8+ T cells were depleted using CD8 Dynabeads and according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Dynal). Peptide restimulations were performed with autologous PBMCs irradiated and pulsed with peptide at a concentration of 1×106/ml. After 2 days of peptide restimulation, 10–20 U/ml of rhIL-2 was added to the cultures. Cells were tested after three or four in vitro restimulations.

Human proliferation assays

Proliferation assays were performed in round-bottom 96-well plates with 5×104 effector cells per well. APCs consisted of irradiated and peptide-pulsed allogeneic HLA-DR1 B-LCL for cultures from HLA-DR1 donors and irradiated and peptide-pulsed autologous PBMCs for cultures from HLA-DR4 donors. Cultures were performed for 96 h, and [3H]-thymidine was added at 37 kBq/well, 18 h prior to harvesting.

Cytokine ELISA

All cytokine measurements were performed using Duoset kits from R&D Systems and according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ELISA plates used were purchased from Costar. The lower limit detection of the assay was ~10 pg/ml. Samples were run in duplicates or triplicates, and results are presented as means of the replicates. Cytokine production was considered specific when values of cultures with the relevant peptide were above 50 pg/ml and at least twice above the background production of cultures with the irrelevant peptide.

Results

Peptide responses in HLA-DR–transgenic mice

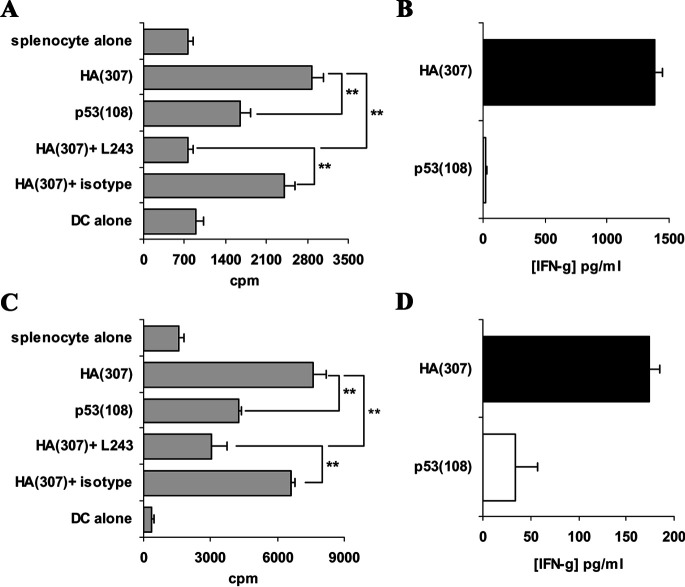

Responses to HA(307) peptide can be monitored by proliferation assays and cytokine measurement on the splenocytes of immunised mice

FVB/N-DR1 and C57BL/6-DR4 mice were immunised twice at a 1-week interval with 100 μg of HA(307) peptide emulsified in IFA. Following in vitro restimulation with the peptide for 6 days, immune splenocytes were depleted in CD8+ T cells and used as responders in a proliferation assay. Peptide-pulsed BM-DCs were used as APCs in these experiments. Proliferation was observed to the relevant peptide HA(307) but not to the control irrelevant peptide p53(108), both in FVB/N-DR1 mice (Fig. 1a) and C57BL/6-DR4 mice (Fig. 1c). These responses were blocked by the addition to the cultures of a mouse anti-HLA-DR antibody (L243), but not of an isotype-matched antibody. These data demonstrated that responses to the reported immunogenic HLA-DR–restricted peptide HA(307) can be monitored by proliferation assays on the splenocytes of immunised mice. Moreover, proliferative responses correlated with the production of IFN-γ (Fig. 1b, d), suggesting that cytokine measurement of the culture supernatants was also suitable for the detection of peptide-specific responses in these transgenic mice. Collectively, these data demonstrated that, following peptide immunisation of FVB/N-DR1 and C57BL/6-DR4 mice, HLA-DR–restricted immunogenic peptides could be detected using proliferation assays and cytokine measurements. Therefore, this procedure was extended to candidate peptides from p53.

Fig. 1.

Responses to HA(307) peptide following immunisation of FVB/N-DR1 and C57BL/6-DR4 mice. HLA-DR transgenic were immunised with HA(307) peptide twice at a 1-week interval, and splenocytes were collected and restimulated in vitro with peptide for 6 days. On day 4–5, culture supernatants were collected and reserved for analysis of cytokine production by ELISA. On day 6, these cells were depleted in CD8+ T cells and used as responders in proliferation assays. BM-DCs pulsed with peptide (relevant: HA[307], and irrelevant: p53[108]) were used as APCs. Anti-HLA-DR antibody L243 and an isotype-matched antibody were also added to the cultures in order to assess the HLA-DR restriction of the responses. Cultures were incubated for 60 h and tritiated-thymidine was added 18 h prior to harvesting the cells. Results are presented as means of the cpm of quadruplicate wells. a CD8-depleted splenocytes from FVB/N-DR1 mice proliferated to the HA(307) peptide used for immunisation but not to the irrelevant peptide p53(108). Responses were HLA-DR restricted as demonstrated by blockade of the proliferation by the addition in the cultures of L243 antibody but not of an isotype-matched antibody (HA[307] + L243 vs HA[307] + isotype). b Proliferation data correlated with peptide-specific IFN-γ production in the splenocyte cultures of FVB/N-DR1 mice. c CD8-depleted splenocytes from C57BL/6-DR4–transgenic mice proliferated specifically to the peptide in an HLA-DR–restricted manner. d Proliferation data in C57BL/6-DR4 mice correlated with peptide-specific IFN-γ production. Results presented are representative of 5 independent experiments for FVB/N-DR1 and 4 for C57BL/6-DR4. **p<0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

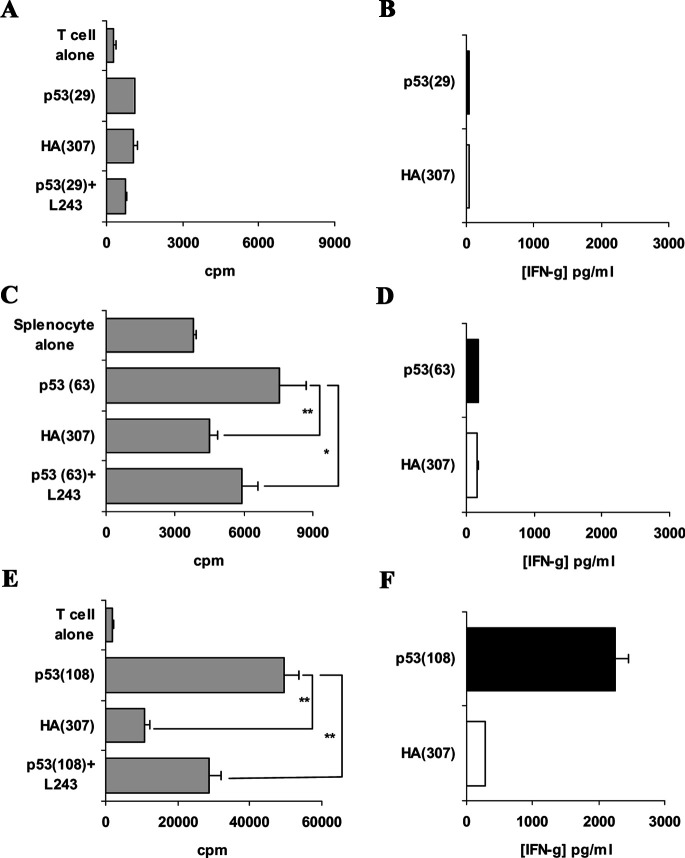

p53 Peptide immunogenicity in FVB/N-DR1 mice

p53 Peptides from the wild-type sequence of the human protein were predicted to bind to HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 according to the evidence-based computer-assisted algorithm SYFPEITHI [22]. Three peptides displaying high binding scores for both HLA-DR alleles were selected and synthesised (Table 1). All three peptide sequences are different from their murine counterparts.

FVB/N-DR1 mice were immunised with these peptides from p53, and responses were monitored by proliferation assays and cytokine measurements. The peptide p53(29) failed to generate any peptide-specific responses, whether measured by proliferation assay or cytokine production (Fig. 2a, b; Table 2). The peptide p53(63) induced proliferative responses in three out of six immunised mice (Fig. 2c; Table 2). IFN-γ was never produced specifically to the peptide (Fig. 2d; Table 2); however, in one case, low levels (<100 pg/ml) of peptide-specific IL-5 production were detected (Table 2). These proliferative responses were partially blocked by the addition of L243 in the cultures, demonstrating the HLA-DR restriction of the observed response. Peptide-specific proliferations to this peptide were confirmed following a second in vitro peptide restimulation and reassessment of the response (data not shown). CD8-depleted splenocytes of 12 out of 15 mice immunised with p53(108) peptide showed peptide-specific proliferation, which was HLA-DR-restricted as demonstrated by proliferation blockade by the addition of L243 antibody in the cultures (Fig. 2e). Moreover, cytokines (IFN-γ or IL-5) were produced in large quantities by the splenocytes cultured with the relevant peptide, but not with an irrelevant peptide (Fig. 2f; Table 2). The immunogenicity of p53(108) peptide was consistently confirmed when the CD8-depleted splenocytes were restimulated for a second week, and the response was reassessed by proliferation assays and cytokine measurements (data not shown). These data indicated that p53(63) and p53(108) peptides are immunogenic in an HLA-DR1–restricted manner in FVB/N-DR1 mice.

Fig. 2.

Responses to p53 candidate peptides in FVB/N-DR1 mice. FVB/N-DR1 mice were immunised with p53(29), and no peptide-specific responses of CD8-depleted splenocytes were observed either by proliferation assays (a) or cytokine production (b). c CD8-depleted splenocytes from mice immunised with p53(63) peptide displayed peptide-specific proliferation, which was blocked by the addition of L243 in the culture, demonstrating the HLA-DR restriction of the response. d Production of IFN-γ was not peptide specific in these experiments; however, in one case low levels of IL-5 (<100 pg/ml) were produced specifically to the peptide (data not shown). e Peptide-specific proliferation to p53(108) peptide was observed in 12 out of 15 FVB/N-DR1–immunised mice, and responses were HLA-DR–restricted, as demonstrated by blocking with L243 antibody. f Proliferation correlated either with peptide-specific IFN-γ production in eight cases, or with peptide-specific IL-5 production in four other cases (data not shown). Data presented are representative of two independent experiments for p53(29) peptide, three for p53(63) peptide and five for p53(108) peptide. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

Table 2.

Frequency of responses to HA(307) and p53 peptides in HLA-DR–transgenic mice

| Peptide | Proliferationa | IFN-γb | IL-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| FVB/N-DR1 | |||

| HA(307) | 8/10 | 8/10 | 0/10 |

| p53(29) | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| p53(63) | 3/6 | 0/6 | 1/6 |

| p53(108) | 12/15 | 8/15 | 4/10c |

| C57BL/6-DR4 | |||

| HA(307) | 6/8 | 6/8 | 0/8 |

| p53(29) | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| p53(63) | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| p53(108) | 3/8 | 0/8 | 5/8 |

aNumber of positive results (p<0.05 in proliferation assays of relevant vs irrelevant peptides) / number of animals tested

bNumber of positive results (cytokine production with relevant peptide above 50 pg/ml and at least twice above the production with irrelevant peptide) / number of tested animals

cResponses of individual mice were either biased toward a Th1 phenotype (IFN-γ production) or toward a Th2 phenotype (IL-5 production)

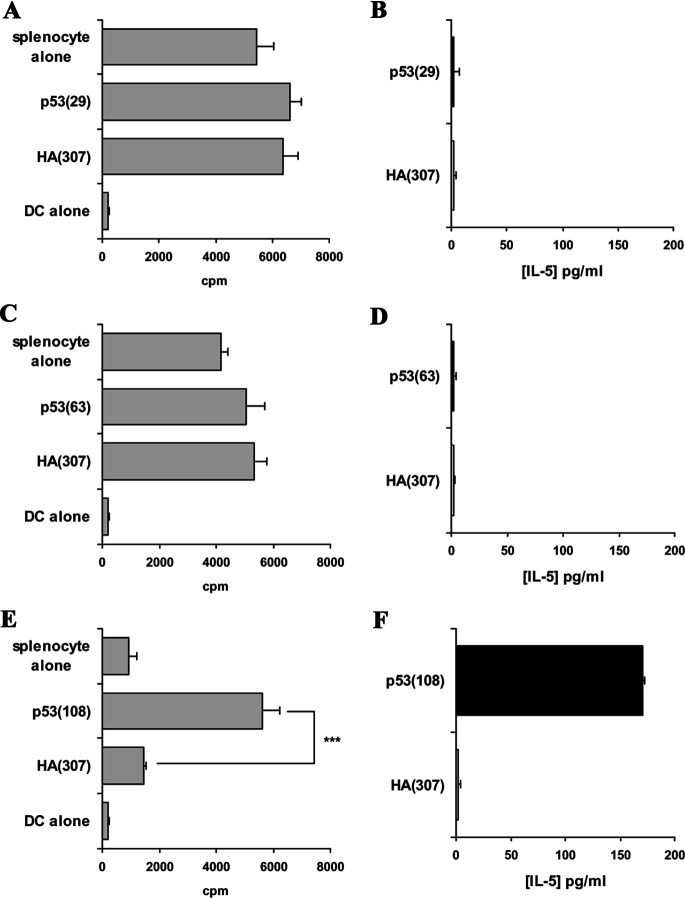

p53 Peptide immunogenicity in C57BL/6-DR4 mice

The murine MHC class II knockout C57BL/6-DR4+ mice were immunised with the same p53 peptides, and responses were monitored by proliferation assays and cytokine production after one and two in vitro restimulations. Peptides p53(29) and p53(63) failed to elicit any proliferative responses or induce IFN-γ or IL-5 production in the splenocytes of immunised mice (Fig. 3a–d). In contrast, CD8-depleted splenocytes proliferated specifically to p53(108) peptide in three out of eight immunised mice and produced IL-5 in five out of eight immunised mice (Fig. 3e, f; Table 2). It is noteworthy that no IFN-γ production was observed to p53(108) peptide in this strain (Table 2). The significance of this observation remains unclear. Proliferation blockade was observed by the addition in the cultures of the anti-HLA-DR antibody L243, demonstrating that the responses to p53(108) peptide were also HLA-DR–restricted in C57BL/6-DR4 mice (data not shown). These data demonstrated the immunogenicity of p53(108) peptide in an HLA-DR4–restricted manner in C57BL/6-DR4 mice. Because this peptide was immunogenic in two HLA-DR alleles, further investigation concentrated on this candidate Th epitope.

Fig. 3.

Responses to p53 candidate peptides in C57BL/6-DR4 mice. a and c C57BL/6-DR4 mice were immunised with p53(29) or p53(63) peptide, and CD8-depleted splenocytes displayed no proliferative responses to the peptide whether tested after one or two in vitro peptide restimulations. b and d No cytokine production was observed in the splenocytes of mice immunised with p53(29) or p53(63) peptide. e CD8-depleted splenocytes of C57BL/6-DR4 mice immunised with p53(108) peptide, displayed peptide-specific proliferation; the HLA-DR restriction of the response was demonstrated by blockade with L243 antibody (data not shown). f IL-5 was produced by splenocytes of immunised mice in response to the p53(108) peptide, but not to the irrelevant peptide HA(307); no IFN-γ production to p53(108) peptide was observed in C57BL/6-DR4 mice (data not shown). Data presented are representative of two independent experiments for p53(29) peptide, three for p53(63) peptide and four for p53(108) peptide. ***p<0.001, unpaired Student’s t test.

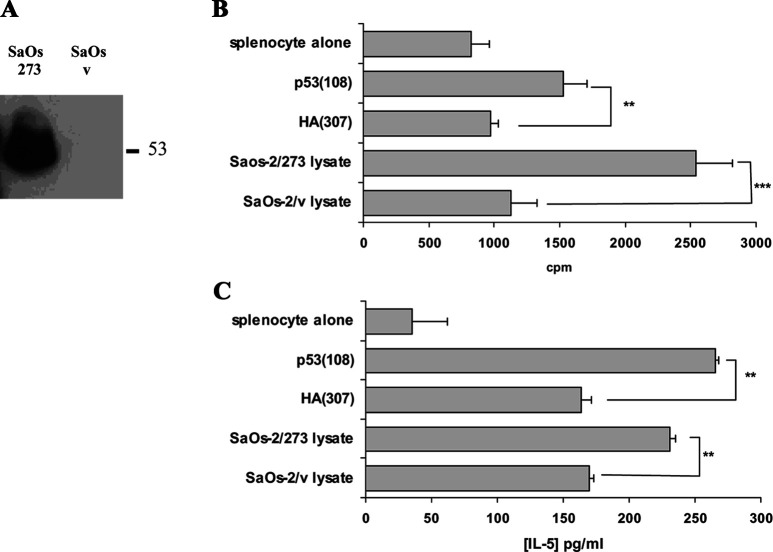

p53(108) Peptide is naturally processed

The splenocytes of mice immunised with p53(108) peptide respond to p53+ tumour cell lysate but not p53− tumour cell lysate

FVB/N-DR1 mice were immunised with p53(108) peptide as described previously and restimulated twice with peptide-pulsed mitomycin C–treated naïve syngeneic splenocytes. Proliferative responses and cytokine production to the peptide and to p53+ tumour cell lysate were then assessed by coculture with BM-DCs pulsed with the relevant peptide p53(108) and an irrelevant peptide HA(307), and also with the cell lysate of the p53− osteosarcoma cell line SaOs-2 transfected with the full length p53 cDNA bearing a point mutation in position 273 R→H (SaOs-2/273) or transfected with the transfection vector alone (SaOs-2/v) [16]. Expression of p53 protein in SaOs-2/273 cells but not in SaOs-2/v cells was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 4a) and flow cytometry (data not shown). As expected, splenocytes responded to p53(108) peptide by proliferation and IL-5 secretion (Fig. 4b, c). It was also demonstrated that these responses were HLA-DR restricted (data not shown). In two independent experiments, splenocytes cultured in presence of DCs fed with p53+ cell lysate demonstrated increased proliferation and IL-5 production when compared with the cocultures of DCs fed with p53− cell lysate (Fig. 4b, c). These data suggested that BM-DCs naturally presented p53(108) peptide onto HLA-DR molecules on the cell surface following antigen processing.

Fig. 4.

Responses of p53(108) peptide–immunised FVB/N-DR1 mice to p53+ tumour cell lysate. SaOs-2/273 have been transfected with p53 bearing the point mutation R→H in position 273, whereas SaOs-2/v have been transfected with the empty vector. a Western blot analysis of the lysate demonstrated that SaOs-2/273 expressed p53 protein, whereas SaOs-2/v showed no detectable level of p53 protein. Following two in vitro restimulations with p53(108) peptide, proliferative responses (b) and IL-5 production (c) were assessed on CD8-depleted splenocytes from peptide-immunised mice. As expected, peptide-specific proliferation and IL-5 production were increased when splenocytes were cocultured with BM-DCs pulsed with the relevant peptide p53(108). Proliferation of DCs was below 300 cpm, and no IL-5 secretion was detected in cultures of DCs alone (data not shown). Proliferation and IL-5 production were also increased in the cocultures of CD8-depleted splenocytes with DCs fed with the p53+ tumour cell lysate from SaOs-2/273, when compared with cocultures with DCs fed with the p53− tumour cell lysate from SaOs-2/v. Data presented are representative of two independent experiments. **p<0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

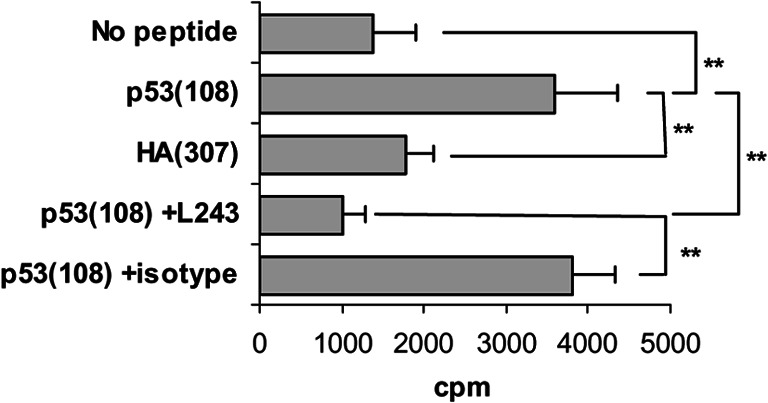

Splenocytes from p53 cDNA-immunised mice respond to p53(108) peptide

FVB/N-DR1 mice were immunised with cDNA encoding for the p53 protein bearing a point mutation in the 273 position (R→H). Proliferative responses to p53(108) peptide but not to an irrelevant peptide were observed in two out of four immunised animals (Fig. 5). The addition in the culture of the anti-HLA-DR antibody L243, but not a control antibody blocked the response, demonstrating the HLA-DR restriction of the proliferation. These data confirmed that p53(108) peptide is naturally generated by APCs following antigen processing and suggested that immune responses can be mounted to this novel Th epitope in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Splenocyte proliferation to p53(108) peptide following p53 cDNA immunisation. FVB/N-DR1 mice were immunised with p53 (273 mutation R→H) cDNA, and splenocyte proliferation was assessed in a 4-day proliferation assay to the peptide. Proliferation of splenocytes cultured with p53(108) peptide was increased as compared to splenocytes cultured with HA(307) peptide or no peptide. Addition of the anti-HLA-DR antibody L243 but not of an isotype-matched antibody blocked the response to p53(108) peptide. **p<0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

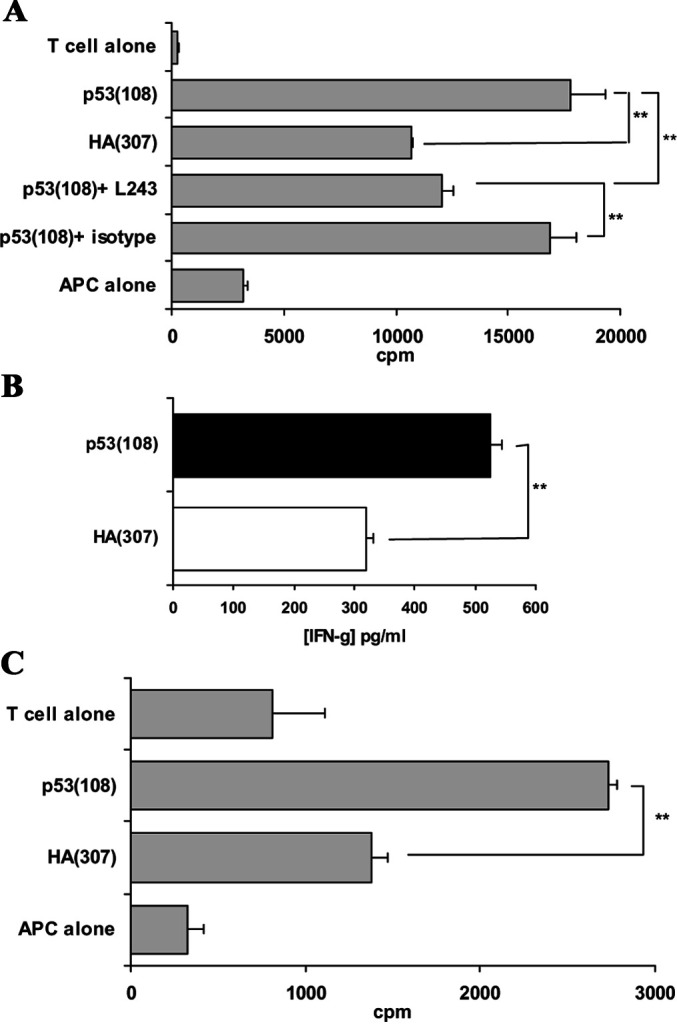

p53(108) Peptide is immunogenic in HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 healthy donors

HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 PBMCs, obtained from consenting healthy donors, were used to generate p53(108)-specific T cells. The method used consisted in stimulating nonadherent PBMCs with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs and restimulating subsequently on a weekly basis with irradiated peptide-pulsed autologous PBMCs. In two out of six healthy HLA-DR1 donors, peptide-specific proliferation was observed, and HLA-DR restriction was demonstrated by response blockade with L243 antibody but not with an isotype-matched antibody (Fig. 6a). In one case, where cell numbers permitted the measurement, peptide-specific proliferation correlated with an elevated production of IFN-γ in the cultures with relevant peptide as compared to cultures with an irrelevant peptide (Fig. 6b). Moreover, in two out of five HLA-DR4 donors peptide-specific proliferation was observed (Fig. 6c). In one case, this proliferative response correlated with peptide-specific production of low levels of GM-CSF (<100 pg/ml, data not shown). Collectively, these data demonstrated that p53(108) peptide is not only immunogenic in HLA-DR–transgenic mice but also in HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 donors, suggesting that this peptide constitutes a novel Th epitope common to HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 antigens.

Fig. 6.

Responses to p53(108) peptide in HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 healthy donors. T cells from consenting HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 healthy donors were sensitised in vitro to p53(108) peptide. After four in vitro restimulations, peptide-specificity was assessed using irradiated allogeneic HLA-DR1+ B-LCL for HLA-DR1 donors or irradiated autologous PBMCs for HLA-DR4 donors as APCs. Peptide-specific proliferations were observed both in HLA-DR1 (a) and in HLA-DR4 (c) donors. Responses were demonstrated to be HLA-DR restricted by blocking with L243 antibody but not with its isotype-matched antibody. b In one case in an HLA-DR1 donor, where the cell numbers permitted, peptide-specific proliferation was correlated with the production of IFN-γ in a peptide-specific manner. Proliferation data presented are representative of the two experiments out of six HLA-DR1 donors and the two experiments out of five HLA-DR4 donors where peptide-specific responses were observed. **p<0.01, unpaired Student’s t test.

Discussion

We sought to develop a more rapid screening procedure for determining the immunogenicity of HLA-DR–restricted candidate peptides using peptide-immunised HLA-DR–transgenic mice. Others have used similar approaches and identified immunogenic peptides from the tumour antigens NY-ESO-1, TRP-1 and gp100, following immunisation with purified antigens or cDNA encoding for the antigen, hence demonstrating its feasibility [25, 26, 30].

Since the priming of the response to the candidate peptides was performed in vivo in inbred strains of mice, it was postulated that responses would be observed more consistently and rapidly than with the human cells stimulated in vitro. Indeed, more than 70% of immunised animals responded to HA(307) peptide after only 1 week of in vitro culture with the peptide. These data demonstrated that peptide immunisation of HLA-DR–transgenic mice, followed by response monitoring for proliferation and cytokine production constituted a robust method for detecting HLA-DR–restricted immunogenic peptides. It was therefore speculated that this procedure could identify novel HLA-DR–restricted immunogenic peptides from tumour antigens.

In order to verify this hypothesis, candidate HLA-DR–restricted peptides from wild-type p53 protein were predicted using the evidence-based algorithm SYFPEITHI [11]. Three peptides displaying high scores for HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 were selected and used to immunise HLA-DR–transgenic mice. The peptide p53(29) failed to elicit any responses whether tested in FVB/N-DR1 or C57BL/6-DR4 mice. The peptide p53(63) was immunogenic in FVB/N-DR1 mice but not in C57BL/6-DR4 mice. This indicated that this peptide might only bind to HLA-DR1 molecules and therefore be immunogenic in that context. Moreover, responses were weak and usually required a second in vitro peptide restimulation to generate a significant result. Therefore, this peptide was not further investigated.

In contrast, the p53(108) peptide elicited responses consistently both in FVB/N-DR1 and C57BL/6-DR4 mice. Since proliferation assays were systematically conducted with CD8-depleted splenocytes and with addition of anti-HLA-DR blocking antibody or its relevant isotype control antibody, proliferative responses were demonstrated to be CD4 driven and HLA-DR restricted. Data from proliferation assays were confirmed by cytokine measurements in the same experimental conditions and by repeating the proliferation assays after a second in vitro restimulation. The consistency of the results obtained, particularly for p53(108) peptide, render this strategy a rapid and robust approach for determining the immunogenicity of HLA-DR–restricted candidate peptides. In conclusion, this strategy permitted the identification of two novel immunogenic HLA-DR–restricted peptides from p53.

Interestingly, the bias of the responses toward Th1 or Th2 (as measured by cytokine production) was not dependent on the peptide used for immunisation as illustrated in FVB/N-DR1 mice immunised with p53(108) peptide. However, it was consistently observed, and in accordance with previous reports [4], that repetitive in vitro peptide stimulation promoted a Th2 response as measured by augmented levels of IL-5 production in response to a second or third encounter with the antigen in vitro. The significance of these observations is unclear and may be the result of the in vitro culture conditions used in these experiments. This raised, however, the interesting observation that Th responses should be systematically monitored for Th1 and Th2 cytokines when CD4+ T cells are restimulated in vitro. Since the scope of this study was to demonstrate the existence of Th responses to the candidate peptides, independently of their bias, we decided to systematically monitor responses in HLA-DR–transgenic mice by measuring both IFN-γ and IL-5 production in all samples.

Peptide immunisation of HLA-DR–transgenic mice demonstrated that p53(108) peptide was immunogenic in an HLA-DR–restricted context. However, it was essential to demonstrate that this peptide was naturally generated by APCs. Two approaches were undertaken: (1) measurement of the response of splenocytes from peptide-immunised mice to DCs pulsed with the lysate of p53+ tumour cells, and (2) assessment of the proliferative capacity to the peptide in the splenocytes of mice immunised with cDNA encoding for p53. Both sets of experiments indicated that p53(108) peptide was naturally processed and presented on the cell surface of APCs. In two independent experiments, splenocytes from peptide-immunised mice proliferated and secreted IL-5 when co-incubated with DCs pulsed with the lysate of the p53+ transfectant SaOs-2/273 but not to the p53− transfectant SaOs-2/v. This indicated that p53(108) peptide was presented on the cell surface of DCs following processing of the antigen. Moreover, following p53 DNA immunisation of FVB/N-DR1 mice, splenocyte cultures showed peptide-specific proliferation to p53(108) peptide in a HLA-DR–restricted manner. Collectively, these data demonstrated that p53(108) peptide is not only immunogenic in HLA-DR–transgenic mice but also that APCs can process p53 protein and prime an immune response to it.

This novel, naturally processed, HLA-DR1– and HLA-DR4–restricted epitope from p53 validated the use of HLA-DR–transgenic mice for the identification of novel immunogenic tumour-specific peptides and confirmed that HLA-DR–transgenic mice possess a repertoire of T-cell reactivity which overlaps with the human repertoire.

Because p53(108) peptide was a naturally processed immunogenic HLA-DR–restricted peptide in transgenic mice, it appeared essential to verify its immunogenicity in humans. To this end, HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 PBMCs, obtained from consenting healthy donors, were used to generate p53(108)-specific T cells. In two out of six HLA-DR1 donors and in two out of five HLA-DR4 donors, proliferation was observed when the T cells were re-presented with the relevant peptide but not with an irrelevant peptide. Moreover, when the cell numbers permitted the measurement, these proliferation data correlated with cytokine production. It was also demonstrated that the responses observed were restricted to HLA-DR. Collectively, these data suggested that p53(108) was also immunogenic in HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 healthy donors. Further work is currently ongoing to demonstrate the processing of p53(108) peptide by human APCs. These data combined with the results obtained in HLA-DR–transgenic mice suggested that p53(108) peptide constitutes a novel p53 Th epitope common to HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 antigens.

Several MHC class II–restricted peptides from p53 have been described, some using normal donor PBMCs [28, 30], and in one case with patient PBMCs [5]. Interestingly, two of the peptides described in these studies encompass the same region as the p53(108) peptide described here: p53(108–122) is described by Fujita et al. [8] in a HLA-DP5 context [28], whereas in p53(110–124) is described by Chikamatsu et al. [5] in a HLA-DR4 context. It could be argued that the peptides p53(110–124) described by Chikamatsu et al. [5] and p53(108–122) described in the present study possess the same core sequence, and thereby represent the same immunogenic sequence. However, an alternative explanation can be hypothesised from the predictive score of each peptide using the SYFPEITHI algorithm. The p53(108–122) peptide scores 31 for HLA-DR1 and 26 for HLA-DR4, whereas the p53(110–124) peptide scores 26 for HLA-DR1 and 22 for HLA-DR4. This suggests that this extended sequence of p53 enhances the binding affinity for HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 molecules. Although further work is required to precisely define the core of these immunogenic peptides, it could be speculated that T cells specific for both peptides are likely to co-exist, and that this region of p53 is highly immunogenic and might contain other Th epitopes restricted to other MHC class II alleles. Indeed, Zwaveling et al. [31] have recently described a murine Th epitope in the same region of p53 (equivalent to the human p53[110–124] peptide). In their study, they succeeded in generating high affinity anti-p53 CD4+ T cells in p53 null mice, and were also capable of demonstrating the existence of anti-p53 CD4+ T cells in p53+/+ mice. Moreover, when these high affinity anti-p53 CD4+ T-cell clones were adoptively transferred into hosts bearing a p53–over-expressing tumour together with anti-p53 CTLs, therapy was improved when compared with anti-p53 CTLs transferred alone or with CD4+ T-cell clones of irrelevant specificity. This observation indicated that activation of CD4+ T cells to tumour antigens is important in promoting antitumour CTL activity particularly in the cases where only low affinity CTLs can be generated to the tumour antigen.

In conclusion, this study describes a method for the rapid detection of novel HLA-DR–restricted immunogenic peptides, which can subsequently be tested in humans. This combination of peptide immunisation of HLA-DR–transgenic mice and in vitro peptide sensitisation of T cells from healthy donors has permitted the identification of a novel HLA-DR1– and HLA-DR4–restricted Th epitope: p53(108–122). The identification of MHC class II–restricted peptides from tumour antigens will develop our understanding of the role of antitumour CD4+ T cells and ultimately lead to the improvement of immunotherapeutic strategies to cancer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the John and Lucille van Geest foundation and the National Eye Research Centre. The authors wish to acknowledge Mr Stephen Reeder for technical assistance throughout this work and Prof. Soussi (Marie Curie, Paris, France) for kindly providing the p53 plasmid and the anti-p53 antibody HO-7.

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen-presenting cell

- BM-DC

Bone marrow–derived dendritic cell

- DR1

DRβ1*0101

- DR4

DRβ1*0401

- rh

Recombinant human

- Th

T helper

References

- 1.Ali SA, Lynam J, McLean CS, Entwisle C, Loudon P, Rojas JM, McArdle SE, Li G, Mian S, Rees RC. Tumour regression induced by intratumour therapy with a disabled infectious single cycle (DISC) herpes simplex virus (HSV) vector, DISC/HSV/murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, correlates with antigen-specific adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2002;168:3512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altmann DM, Douek DC, Frater AJ, Hetherington CM, Inoko H, Elliott JI. The T cell response of HLA-DR transgenic mice to human myelin basic protein and other antigens in the presence and absence of human CD4. J Exp Med. 1995;181:867. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennouna J, Hildesheim A, Chikamatsu K, Gooding W, Storkus WJ, Whiteside TL. Application of IL-5 ELISPOT assays to quantification of antigen-specific T helper responses. J Immunol Methods. 2002;261:145. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(01)00566-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty NG, Li L, Sporn JR, Kurtzman SH, Ergin MT, Mukherji B. Emergence of regulatory CD4+ T cell response to repetitive stimulation with antigen-presenting cells in vitro: implications in designing antigen-presenting cell-based tumor vaccines. J Immunol. 1999;162:5576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chikamatsu K, Albers A, Stanson J, Kwok WW, Appella E, Whiteside TL, DeLeo AB. p53(110–124)-specific human CD4+ T-helper cells enhance in vitro generation and antitumor function of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen PA, Peng L, Plautz GE, Kim JA, Weng DE, Shu S. CD4+ T cells in adoptive immunotherapy and the indirect mechanism of tumor rejection. Crit Rev Immunol. 2000;20:17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egilmez NK, Hess SD, Chen FA, Takita H, Conway TF, Bankert RB. Human CD4+ effector T cells mediate indirect interleukin-12- and interferon-gamma-dependent suppression of autologous HLA-negative lung tumor xenografts in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita H, Senju S, Yokomizo H, Saya H, Ogawa M, Matsushita S, Nishimura Y. Evidence that HLA class II-restricted human CD4+ T cells specific to p53 self peptides respond to p53 proteins of both wild and mutant forms. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:305–316. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<305::AID-IMMU305>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gnjatic S, Cai Z, Viguier M, Chouaib S, Guillet JG, Choppin J. Accumulation of the p53 protein allows recognition by human CTL of a wild-type p53 epitope presented by breast carcinomas and melanomas. J Immunol. 1998;160:328–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halder T, Pawelec G, Kirkin AF, Zeuthen J, Meyer HE, Kun L, Kalbacher H. Isolation of novel HLA-DR restricted potential tumor-associated antigens from the melanoma cell line FM3. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991;253:49. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman RM. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito K, Bian HJ, Molina M, Han J, Magram J, Saar E, Belunis C, Bolin DR, Arceo R, Campbell R, Falcioni F, Vidovic D, Hammer J, Nagy ZA. HLA-DR4-IE chimeric class II transgenic, murine class II-deficient mice are susceptible to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2635. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knights AJ, Zaniou A, Rees RC, Pawelec G, Muller L. Prediction of an HLA-DR-binding peptide derived from Wilms’ tumour 1 protein and demonstration of in vitro immunogenicity of WT1(124–138)-pulsed dendritic cells generated according to an optimised protocol. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:271. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu J, Celis Use of two predictive algorithms of the world wide web for the identification of tumor-reactive T-cell epitopes. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McArdle SE, Rees RC, Mulcahy KA, Saba J, McIntyre CA, Murray AK. Induction of human cytotoxic T lymphocytes that preferentially recognise tumour cells bearing a conformational p53 mutant. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000;49:417. doi: 10.1007/s002620000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McArdle SE, Ali SA, Li G, Mian S, Rees RC. Phenotypic and functional differences of dendritic cells generated under different in vitro conditions. Methods Mol Med. 2003;81:359. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-372-0:359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller L, Knights A, Pawelec G. Synthetic peptides derived from the Wilms’ tumor 1 protein sensitize human T lymphocytes to recognize chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Hematol J. 2003;4:57. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nijman HW, Van der Burg SH, Vierboom MP, Houbiers JG, Kast WM, Melief CJ. p53, a potential target for tumor-directed T cells. Immunol Lett. 1994;40:171. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardoll DM. Cancer vaccines. Nat Med. 1998;4:525. doi: 10.1038/nm0598supp-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pardoll DM, Topalian SL. The role of CD4+ T cell responses in antitumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:588. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(98)80228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanovic S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ropke M, Hald J, Guldberg P, Zeuthen J, Norgaard L, Fugger L, Svejgaard A, Van der Burg S, Nijman HW, Melief CJ, Claesson MH. Spontaneous human squamous cell carcinomas are killed by a human cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone recognizing a wild-type p53-derived peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soussi T. p53 antibodies in the sera of patients with various types of cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Touloukian CE, Leitner WW, Topalian SL, Li YF, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Identification of a MHC class II-restricted human gp100 epitope using DR4-IE transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2000;164:3535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Touloukian CE, Leitner WW, Robbins PF, Li YF, Kang X, Lapointe R, Hwu P, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Expression of a “self-”antigen by human tumor cells enhances tumor antigen-specific CD4(+) T-cell function. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Der Burg SH, Menon AG, Redeker A, Franken KL, Drijfhout JW, Tollenaar RA, Hartgrink HH, Van De Velde CJ, Kuppen PJ, Melief CJ, Offringa R. Magnitude and polarization of p53-specific T-helper immunity in connection to leukocyte infiltration of colorectal tumours. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:425. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang RF. The role of MHC class II-restricted tumor antigens and CD4+ T cells in antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:269. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)01896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang RF, Wang X, Atwood AC, Topalian SL, Rosenberg SA. Cloning genes encoding MHC class II-restricted antigens: mutated CDC27 as a tumor antigen. Science. 1999;284:1351. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng G, Touloukian CE, Wang X, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, Wang RF. Identification of CD4+ T cell epitopes from NY-ESO-1 presented by HLA-DR molecules. J Immunol. 2000;165:1153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwaveling S, Vierboom MP, Ferreira Mota SC, Hendriks JA, Ooms ME, Sutmuller RP, Franken KL, Nijman HW, Ossendorp F, Van Der Burg SH, Offringa R, Melief CJ. Antitumor efficacy of wild-type p53-specific CD4(+) T-helper cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]