Abstract

Fraxinus chinensis Roxb is a deciduous tree, which is distributed worldwide and has important medicinal value. In Asia, the bark of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb is a commonly used traditional Chinese medicine called Qinpi. Esculetin is a coumarin compound derived from the bark of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb and its glycoside form is called esculin. The aim of the present study was to systematically review relevant literature on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of esculetin and esculin. Esculetin and esculin can promote the expression of various endogenous antioxidant proteins, such as superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase. This is associated with the activation of the nuclear factor erythroid-derived factor 2-related factor 2 signaling pathway. The anti-inflammatory effects of esculetin and esculin are associated with the inhibition of the nuclear factor κ-B and mitogen-activated protein kinase inflammatory signaling pathways. In various inflammatory models, esculetin and esculin can reduce the expression levels of various proinflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6, thereby inhibiting the development of inflammation. In summary, esculetin and esculin may be promising candidates for the treatment of numerous diseases associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, such as ulcerative colitis, acute lung and kidney injury, lung cancer, acute kidney injury.

Keywords: esculin, esculetin, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory

1. Introduction

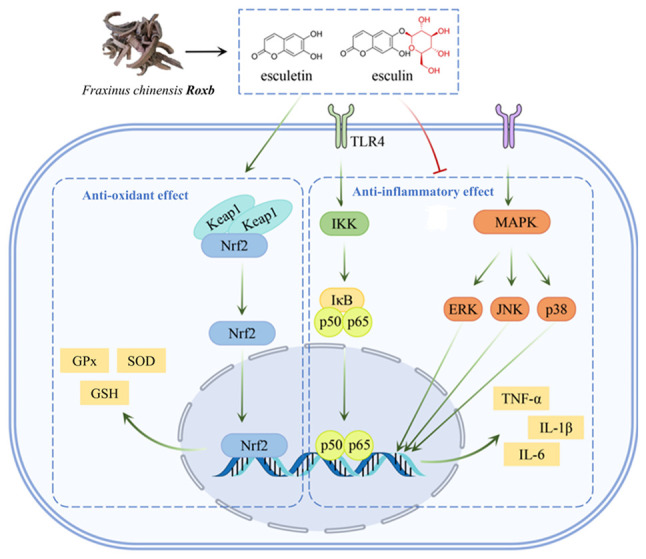

Oxidative stress is caused by the disruption of the balance between oxidative and antioxidant responses in the body. When exposed to noxious stimuli, the body is in a state of oxidative stress, and the level of free radicals is elevated, leading to apoptosis and tissues damage (1). Inflammation is the fundamental response of the body to injury and infection. However, if inflammation is not controlled, various proinflammatory factors (Interleukins, Tumor Necrosis Factor, etc.) released by persistent inflammation can induce further pathological responses (2). Previous research shows that oxidative stress and inflammation are associated with the occurrence and development of a number of diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer (3-5). Therefore, studies have been attempting to reveal additional effective drugs with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. As an important source of drugs, natural products serve a key role in the identification and development of new drugs (6). Therefore, finding new antioxidant and anti-inflammatory drugs from natural products may become an important research direction in the future. An overview of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb in Fig. 1.

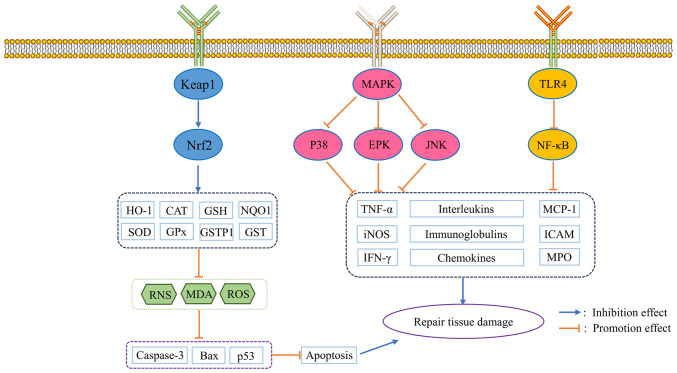

Figure 1.

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Fraxinus chinensis Roxb. TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; IKK, IκB kinase.

Fraxinus chinensis Roxb is a deciduous tree, which is distributed worldwide and has important medicinal value. In Asia, the bark of Fraxinus is a commonly used traditional Chinese medicine called Qinpi (7). The bark of Fraxinus contains 1.0~1.4%, with esculetin and its glycoside form, esculin, being the most studied active ingredients (Fig. 2) (8). The present study shows that esculetin and esculin have a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antitumor, antidiabetic, anti-atherosclerotic, and immunomodulatory effects. And esculetin and esculin are expected to be used in the treatment of various diseases, such as cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases. Further studies have shown that esculetin and esculin have prominent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which may underlie their broad pharmacological activities (9,10). Antioxidant effects of esculetin and esculin are associated with the activation of the nuclear factor erythroid-derived factor 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway (11). As a key signaling pathway for antioxidation, the Nrf2 signaling pathway can regulate the expression levels of various endogenous antioxidant proteins, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione (GSH) (11,12). The anti-inflammatory effects of esculetin and esculin are associated with the inhibition of nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), two important inflammatory signaling pathways. In various inflammatory models, esculetin and esculin can reduce the expression levels of a number of proinflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6, thereby inhibiting the development of inflammation (13,14). In summary, as natural products, esculin and esculetin may be promising candidates for the potential use as complementary and alternative medicines. The present study aimed to systematically review studies that investigated the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of esculetin and esculin, as well as to provide current and useful information.

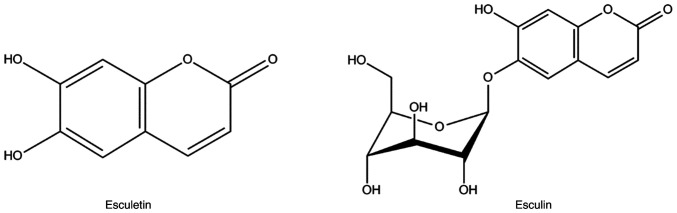

Figure 2.

Structural formula of esculetin and esculin.

2. Antioxidant activities of esculin and esculetin

It is considered that the oxidative and antioxidant reactions of the normal body are in a state of dynamic equilibrium. Oxidative stress is caused by the breakdown of this balance and the accumulation of oxidative substances such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species such as O2•−, NO•, ONOO− and OH• (15). A study confirmed that esculin and esculetin effectively scavenge free radicals (16). In addition, experimental results show that esculin and esculetin can improve various pathological processes that are associated with oxidative stress. This is associated with the activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway and the promotion of the expression of various antioxidant proteins such as GSH and SOD (15,16).

Antioxidant activities of esculetin. Free radical scavenging effects of esculetin

At present, a number of studies have determined the scavenging effect of esculetin on 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), but there are differences between the results. Wang et al (16) find that the clearance rates of DPPH with different concentrations of esculetin (0.02, 0.05, 0.08 and 0.1 mg/ml) are 28.13, 59.94, 79.68 and 100%, respectively. The SC50 values of esculetin for scavenging DPPH as determined by Jeong et al (17) and Kim et al (18) are both 14.68 µM. The SC50 value of esculetin for scavenging DPPH as determined by Vianna et al (19) is 25.18 µM, but is determined by Lee et al (20) to be 40 µM. In addition to scavenging DPPH, esculetin also has a scavenging effect on hydroxyl radicals with an SC50 value of 0.091 mg/ml (16). Hsia et al (21) also find that esculetin (50-80 µM) inhibits hydroxyl radical formation in washed human platelets. In addition, Lee et al (22) demonstrated that esculetin has a scavenging effect on superoxide anion radicals with an SC50 value of 0.6 µg/ml. In addition, esculetin inhibits peroxidase-induced oxidation in a non-competitive manner with a Ki value of 9.5 µM in the methemalbumin-H2O2-tetramethylbenzidine pseudoperoxidase system (23). By scavenging the free radicals, esculetin (10-100 mg/ml) protects human dermal fibroblasts from UVB-induced oxidative stress damage (22). Furthermore, by scavenging the O2-accumulation caused by H2O2, esculetin (100 µM) protects human leukemia NB4 cells from oxidative stress damage (24,25).

Regulated antioxidant protein action of esculetin

Studies using cells further confirm the antioxidant effect of esculetin, which regulates the expression of various antioxidant proteins (26-28). For example, in L-buthionine-sulfoximine-induced mouse cortical cells, esculetin (10-100 µM) increases GPx, glutathione reductase (GR) and GSH activities and inhibits oxidized glutathione (glutathione disulfide; GSSG) accumulation (26). In addition, esculetin (10 µM) can inhibit the accumulation of ROS in Helicobacter pylori urease-induced human vascular endothelial cells by promoting the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (27). Additionally, esculetin (10-20 µM) can increase the levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), SOD and GSH and inhibit the accumulation of ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) in tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP)-induced HepG2 cells (28,29).

Further studies show that the antioxidant activity of esculetin is associated with the regulation of multiple signaling pathways, such as inhibiting the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways (13,14,30). The Nrf2 signaling pathway is the primary defense mechanism for inhibiting oxidative stress, and it regulates the expression of a number of important antioxidant proteins such as HO-1, SOD and GPx. A large number of studies show that the antioxidant effect of esculetin is associated with the activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway (15,30,31). Sen et al (30) find that esculetin (10-20 µM) reduces the production of ROS in the high glucose-induced human renal tubular epithelial HK-2 cells and that the Nrf2 signaling pathway is activated. Furthermore, esculetin (20-500 µM) can induce SOD expression in the leukemia NB4 cells by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway (31).

Scavenging ROS effects of esculetin

Accumulation of ROS can activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and induce apoptosis, and esculetin can block this process by scavenging ROS (32). In zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, esculetin (10-30 µM) can decrease GPx and GSH depletion by inhibiting lipoxygenase expression, which ameliorates the ROS accumulation-induced apoptosis (33). Esculetin (0.1-10 µM) can also protect Aβ25-35-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells from apoptosis caused by ROS accumulation by increasing SOD, GSH and catalase (CAT) expression levels, which reduces caspase-3, cytochrome c and Bax expression levels and increases Bcl-2 expression levels (34,35). Additionally, esculetin (5-20 µM) increases SOD levels and decreases ROS levels and thus decreases lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), Bax and cleaved caspase-3 levels in hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced myocardial H9c2 cells (36).

In H2O2-induced human corneal epithelial cells, esculetin (20-100 µM) activates the Nrf2 signaling pathway, inducing the expression of multiple antioxidant genes, including HO-1, quinone 1 (NQO1), glutamate cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM), SOD1 and SOD2, thereby inhibiting ROS generation and accumulation (37). By activating the Nrf2 pathway and promoting the expression of HO-1, SOD, GPx and CAT, esculetin (12.5-100 µM) inhibits the production and accumulation of ROS in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (38). Furthermore, in H2O2-induced Caco2 cells, esculetin (100-300 µg/ml) activates the Nrf2 pathway and increases the expression of SOD, CAT and GPx (39). Esculetin (10-25 µM) also protects human hepatoma HepG2 cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway and promoting the expression of NQO1 and glutathione (40). Additionally, esculetin (10-100 µM) can restore depleted GSH levels and inhibit the production of ROS and MDA in ethanol-induced HepG2 cells by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway (41).

Amelioration of oxidative stress damage by esculetin. The results of mouse studies further show that esculetin can improve oxidative stress and associated injuries, such as nervous system injury, liver injury and kidney injury: For example, esculetin can improve nervous system injury caused by oxidative stress (42-45). Esculetin (0.5% w/w) also ameliorates 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced neurotoxicity in the substantia nigra pars compacta in mice by preventing nitrosative stress, increasing GSH levels, inhibiting the activation of caspase 3 and preventing neuronal apoptosis (42). Additionally, esculetin (20-80 mg/kg) inhibits tBCCAO-induced activation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway and autophagy in mice by reducing the expression levels of autophagy-related factors (such as Bnip3, Beclin1, Pink1 and parkin) and apoptosis-related factors (such as p53, Bax and caspase 3) by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway (43). In addition, esculetin (25 mg/kg) decreases immobility time and climbing time in the forced swim task elicited in acute restraint stress-induced rats by restoring the activities of antioxidant enzymes including CAT, SOD, GPx and GSH, and reducing the levels of GSSG in rat cortical areas (44). Another study shows that esculetin can inhibit oxidative stress in liver injury (45). In CCl4-induced liver injury rats, esculetin (35 mg/kg) increases SOD and CAT levels and decreases MDA levels (45). Furthermore, in N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced liver injury rats, esculetin (0.5% w/w) ameliorates hepatic lipid peroxidation by restoring the total glutathione levels and increasing the levels of NQO1, HO-1 and glutathione S-transferase Pi (GSTP1) (46). Esculetin can also inhibit oxidative stress in kidney injury. In high-fat diet-induced kidney injury mice, esculetin (40 mg/kg) increases the expression levels of SOD, CAT, GPx, glutathione-S-transferase (GST), non-enzymic antioxidants vitamin C and GSH, and reduces the levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), lipid hydroperoxides and co-conjugated diene (47).

Other antioxidant oxidative effects of esculetin

In addition, He et al (36) find that esculetin (5-20 µM) protects hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced myocardial H9c2 cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. This protective effect is produced by activating the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK2/STAT3) pathway (36). Notably, studies show that activation of the Nrf2 pathway is associated with the extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK) signaling pathway. Esculetin (5 µM) can activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway and promote the expression of NQO1 by activating the ERK signaling pathway in H2O2-induced C2C12 myoblasts (48,49).

The results of animal studies further show that esculetin can improve the oxidative stress caused by ischemia-reperfusion. For example, esculetin (20-40 mg/kg) restores SOD activity and reduces the levels of MDA in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion rats (50). In addition, esculetin can improve the oxidative stress in testicular tissue damage. Esculetin (50 mg/kg) ameliorates AlCl3-induced rat testicular tissue damage by activating the Nrf-2 signaling pathway, increasing the activities of GSH, GPx and CAT and preventing the activation of the apoptotic pathway (51).

In conclusion, the antioxidant effect of esculetin stems from increasing the expression levels of endogenous antioxidants such as NQO1, HO-1, GSH and SOD by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway, which enables the free radicals generated by the body to be scavenged in time to avoid lipid oxidation and apoptosis.

Antioxidant activities of esculin. Free radical scavenging effects of esculin

Free radical scavenging experiments show that esculin has scavenging effects on a variety of free radicals including O2•-, NO• and DPPH, and the SC50 values are 69.27 µg/ml, 8.56 µg/ml and 0.141 µM, respectively (52,53). Similar to the antioxidant mechanism of esculetin, the activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway is also associated with the antioxidant effect of esculin. Studies demonstrate that esculin (50-200 µmol/l) can disrupt the interaction of the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), a key negative regulator of the Nrf2 signaling pathway, with Nrf2 to activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway (54,55).

Regulated antioxidant protein action of esculin

Esculin has significant antioxidant modulating effects and ameliorates oxidative stress in kidney injury. Esculin (150 mg/kg) promotes the expression of SOD, GR and CAT in prooxidant aflatoxin B-1-induced nephrotoxicity mice (56). Similarly, esculin can inhibit the oxidative stress in pancreatic injury (57). Esculin (10-50 mg/kg) increases the expression levels of GPx, SOD and CAT in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 2 diabetic mice (57).

Scavenging ROS effects of esculin

The scavenging ROS effects of esculin have been widely reported. For example, esculin (1-100 µM) protects dopamine-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells from ROS accumulation-induced apoptosis by increasing SOD and GSH expression levels and inhibiting the expression of cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, p53, Bax and caspase 3(58). Myeloperoxidase is able to mediate oxidative stress by promoting ROS production and promoting inflammation-related signaling pathways (59). In human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, esculin reduces the dopamine-induced ROS overproduction, scavenges ROS and enhances the activities of SOD and GSH (58).

Amelioration of oxidative stress damage by esculin

Experiments using cells further confirm the antioxidant effect of esculin. For example, esculin (20-100 µM) can protect linoleic acid hydroperoxide-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells from free radical-induced oxidative stress damage (60).

The results of experiments using mice further show that esculin can decrease oxidative stress and the associated damage. Esculin can inhibit oxidative stress in liver injury, as esculin (10-40 mg/kg) can activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway to increase HO-1 expression levels and decrease the MDA content in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury mice (61). Another study demonstrates that the esculin can improve oxidative stress in gastric injury, as in ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury rats, esculin (12.5-50 mg/kg) increases the SOD levels and decreases the MDA levels (52).

Other antioxidant oxidative effects of esculin

In addition, esculin can decrease oxidative stress in colitis. For example, esculin (5-25 mg/kg) promotes the expression of GPx and partially ameliorates the intestinal injury in rats with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis (53). Furthermore, studies associated with acute lung injury (62) and diabetic nephropathy (63) demonstrate the antioxidant activity of esculin. Esculin can improve oxidative stress in arthritis and, in adjuvant-induced arthritis rats, esculin (10-40 mg/kg) promotes the expression of GPx (64).

In conclusion, esculin, as the glycoside form of esculetin, has similar antioxidant activities to esculetin. By activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway and promoting the expression of various endogenous antioxidants such as HO-1, GSH and SOD, esculin serves a protective role in the process of various tissue injuries.

3. Anti-inflammatory activities of esculetin and esculin

Inflammation is the basic response of the body to injury and infection. However, if inflammation is not controlled, persistent inflammatory responses can induce new pathological responses (such as tissue damage, fibrosis, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, etc.) and lead to the development of various diseases, such as cancer, metabolic diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and vascular diseases (65). Previous research shows that esculetin and esculin can inhibit the expression of proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in various inflammatory models (13,14,61). This is associated with the inhibition of inflammatory signaling pathways, such as NF-κB and MAPK.

Anti-inflammatory activities of esculetin

Studies using cells show that esculetin can inhibit the expression of various inflammatory markers (66). For example, esculetin can inhibit the production of nitric oxide (NO) in IL-1β stimulated rat hepatocytes with an IC50 value of 34 µM (66). Additionally, esculetin (10-100 µg/ml) inhibits IL-6 production in TNF-α stimulated human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells (67). Esculetin (1-10 µg/ml) can also inhibit the release of inflammatory mediators, such as NO, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells (68-71). Further studies demonstrate that the anti-inflammatory effect of esculetin is associated with inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway (72-77). Sun et al (72) demonstrate that esculetin (10-40 µM) inhibits the histamine-induced production of IL-6, IL-8 and mucin-5AC in human nasal epithelial cells, which is partly mediated by inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway (72). Esculetin (12 µg/ml) also inhibits the expression of inducible isoform of NO synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), TNF-α and IL-1β in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway (73). Additionally, esculetin (12.5-25 µg/ml) inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in TNF-α induced vascular smooth muscle cells, which reduces the expression levels of mitochondrial membrane potential-9 (MMP-9) and the binding activity of activating protein-1 (AP-1) (74,75). Furthermore, esculetin (30-200 µM) reduces the IL-1β, COX-2 and TNF-α levels in trimethyltin-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway (76). In addition to inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway, esculetin can also decrease the inflammatory response by inhibiting the MAPK signaling pathway. In LPS-induced human retinal pigment epithelium cells, esculetin (0.78-50 µM) decreases the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-12, TNF receptor and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand by inhibiting the ERK1/2 and NF-κB signaling pathways (77). In addition, lipoxygenases are a family of non-heme iron-containing enzymes and are involved in the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines such as leukotrienes. A previous study demonstrated that the inhibition rate of esculetin on soybean 15-lipoxygenase at a concentration of 28.1 µM is 40.50% (78). Esculetin can also inhibit the activity of 5-lipoxygenase with an IC50 value of 6.6 µM (79).

The results of study with mice further indicate that esculetin can exhibit an anti-inflammatory effect in various inflammatory models (61,63,74). This suggests that esculetin may be promising for the treatment of a variety of inflammation-related diseases, such as ulcerative colitis, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease.

Lung inflammation

A study confirms that esculetin can improve the inflammatory response in lung injury (80). Esculetin (20-40 mg/kg) reduce the histopathological changes (such as alveolar wall thickening, interstitial edema, and pulmonary congestion) and the infiltration of inflammatory cells, and inhibits the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23 and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in LPS-induced acute lung injury mice. This is associated with the inhibition of the activation of the AKT/ERK/NF-κB and retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptor γt (RORγt)/IL-17 signaling pathways (80,81). In polyhexamethylene guanidine-induced pulmonary fibrosis mice, esculetin (10 mg/kg) antagonizes macrophage infiltration, ameliorates alveolar epithelial barrier disruption and reduces the levels of MMP-9, macrophage inflammatory protein 2, IL-8 and IL-1β (82).

Esculetin decreases the inflammatory response in asthma. For example, esculetin (20 mg/kg) reduces the levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, immunoglobulin E (IgE), GATA binding protein 3 and RORγt in the lung tissue of ovalbumin-induced asthma mice (83). In addition, esculetin (10 mg/kg) improves airway inflammation, and inhibits airway eosinophilia, collagen fiber deposition and goblet cell hyperplasia in mice exposed to particles <10 µm. This is associated with the inhibition of the activation of the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway and the expression of COX-2 and nitric oxide synthase 2(84).

Inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract

Esculetin can reduce the inflammatory response in gastrointestinal injury. For example, esculetin (100 mg/kg) decreases the levels of COX-2, iNOS and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-3 in TNBS-induced colitis rats (85). Furthermore, esculetin (5 mg/kg) can inhibit the production of NO, TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain-containing in DSS-induced colitis rats by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways (86,87). Additionally, esculetin (20-40 mg/kg) inhibits the expression of iNOS, TNF-α and IL-6 in ethanol-induced gastric injury rats by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (88).

Inflammation in liver injury

Esculetin decreases the inflammatory response in liver injury. For example, esculetin (0.01%, w/w) can downregulate the expression of inflammatory genes including TLR4, myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), NF-κB, TNF-α and IL-6, and decrease the levels of blood glycated hemoglobin, TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 in high-fat diet-induced fatty liver mice (89).

Neuroinflammation

Esculetin can reduce neuroinflammation. For example, esculetin (5-25 mg/kg) can inhibit the zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced expression of IL-1β and TNF-α in rat brain tissue (90). Furthermore, esculetin (20-40 mg/kg) ameliorates LPS-induced neuroinflammation and depression-like behavior in mice by reducing the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, iNOS and COX-2 in serum and the hippocampus by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (91,92).

Skin-related inflammation

Esculetin decreases skin-related inflammation. In house dust mite (Dermatophagoides farinae extract) and 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced dermatitis mice, esculetin (2-50 mg/kg) reduces serum IgE, IgG2a and histamine levels, reduce the infiltration of inflammatory cells, and inhibits the production of TNF-α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-4, IL-13, IL-17 and IL-31 by inhibiting the STAT1 and NF-κB signaling pathways (93). Furthermore, in imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse, esculetin (50-100 mg/kg) was able to significantly reduce the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-6, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α and IFN-γ) in the skin of mice, and inhibited the phosphorylation of IKK alpha and P65 in the skin of psoriasis, consequently, inhibited the NF-KB signaling pathway (94).

Other inflammation

Esculetin can improve the inflammatory response in other pathological processes. For example, esculetin (20-60 mg/kg) can inhibit the production of inflammatory factors such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 and iNOS in Escherichia coli-induced sepsis mice by inhibiting the NF-κB and STAT1/STAT3 signaling pathways (95). In a rabbit model in which the primary lacrimal gland, sclerotial gland, and cornea were removed to induce dry eye, esculetin (0.05% of the diet) was able to inhibit the expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α by inhibiting the ERK1/2 signaling pathway and thereby suppressing IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α (96). Furthermore, esculetin (10-20 mg/kg) inhibits the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in isoproterenol induced myocardial toxicity in rats by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (97). Additionally, esculetin (2.5-10 mg/kg) can reduce reserpine-induced fibromyalgia in mice, which is associated with the inhibition of monoamine oxidase-A activity, and downregulated the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and TBARS (98). In summary, the aforementioned studies show that esculetin can reduce the expression levels of various proinflammatory factors and inhibit the infiltration of inflammatory cells in a number of inflammatory models. In addition to inhibiting the two most common inflammatory signaling pathways, NF-κB and MAPK, the anti-inflammatory effect of esculetin is also associated with inhibiting the STAT signaling pathway.

Anti-inflammatory activity of esculin

Cellular research shows that esculin (25-200 µM) reduces the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in free fatty acid-induced HepG2 cells (99). Further studies show that the anti-inflammatory effect of esculin is associated with the inhibition of the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. For example, esculin (300-500 µM) can reduce the expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway (100). In LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, esculin (10-50 µM) also inhibits the p38/MAPK signaling pathway and downregulates the MMP-9 level and AP-1 binding activity (101). Additionally, esculin (1 µg-1 mg) can inhibit the p38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and ERK1/2 signaling pathways and reduce the TNF-α and IL-6 expression levels in mouse peritoneal macrophages (102).

Studies using animals further indicates that esculin can exhibit an anti-inflammatory effect in various inflammatory models (95,96,99,100). This suggests that esculin may be promising for the treatment of a variety of inflammation-related diseases (including ulcerative colitis, chronic kidney cardiovascular disease).

Lung inflammation

Esculin can reduce lung injury-related inflammation. For example, esculin (10-50 mg/kg) decreases the levels of NO and TNF-α in hyperoxia-induced lung injury rats (61). Additionally, esculin (20-40 mg/kg) can inhibit the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulate the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in LPS-induced acute lung injury mice (103).

Inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract

Esculin can reduce the inflammatory response in gastrointestinal injury. For example, esculin (5-50 mg/kg) inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulates the levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in DSS-induced colitis mice (100). In ethanol-induced gastric injury mice, esculin (5-20 mg/kg) also inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulates the production of NO, TNF-α and IL-6(104).

Inflammation in liver injury

Esculin can reduce the inflammatory response in liver injury. For example, esculin (10-40 mg/kg) inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway and reduces the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in LPS/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury mice (62). In methionine choline-deficient diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis mice, esculin (20-40 mg/kg) also inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway, downregulates the expression of TNF-α and IL-6, and increases the expression level of the silent information regulator 1(99).

Neuroinflammation

Esculin can improve nervous system inflammation. For example, esculin (50 mg/kg) inhibits the expression of IL-12, IL-6 and TNF-α in the hippocampus of reserpine-induced depression mice (105). Furthermore, esculin (20-40 mg/kg) inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-induced depressed mice hippocampus, which increases the number of selectively activated microglia and decreases the number of classically activated microglia (106). In addition, esculin (30-90 mg/kg) can inhibit the MAPK signaling pathway and reduce the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and MCP-1 to improve memory impairment in STZ-induced diabetic rats (63).

Kidney inflammation

Esculin can improve the inflammatory response in renal injury. For example, esculin (25-100 mg/kg) inhibits the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway and downregulates the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1 and ICAM-1 in LPS-induced acute kidney injury mice (107). Similarly, esculin (30-90 mg/kg) decreases the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, ICAM-1 and NO in the kidney tissue of STZ-induced diabetic rats (108).

Other inflammation

Esculin can also improve the inflammatory response in other pathological processes. For example, esculin (10-40 mg/kg) significantly improved body weight, decreased paw volume, and the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels in adjuvant-induced arthritis rats compared to arthritic controls (64). Additionally, esculin (5-20 mg/kg) can ameliorate xylene-induced rat paw swelling by inhibiting the activation of the p38, MAPK, JNK and ERK1/2 signaling pathways and decreasing TNF-α and IL-6 levels (102). Furthermore, in LPS-induced sepsis mice, esculin (30 mg/kg) inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway and reduces the levels of TNF-α and IL-6(109). In conclusion, esculin (the glycoside form of esculetin) has anti-inflammatory effects and the mechanisms of action are similar to esculetin, inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and inhibiting the expression of various proinflammatory factors.

4. Conclusion and future perspectives

In conclusion, esculetin and esculin have been extensively studied, and studies utilizing cells and/or animals show that both possess a variety of pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-tumor, antidiabetic, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-atherosclerotic and immunomodulatory pharmacological effects (110). The antioxidant effects of esculetin and esculin have been shown in a variety of diseases, their underlying mechanisms of action and biological activities include scavenging of free radicals, promotion of the expression of endogenous antioxidant proteins (such as SOD, GPx, and GSH), modulating the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathway, regulating the cell cycle, inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and migration, etc.. Further studies reveal that this is associated with the activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway (Fig. 3). The anti-inflammatory effects of esculetin and esculin are associated with the inhibition of two important inflammatory signaling pathways, NF-κB and MAPK. In various models of inflammation, including diabetes, liver injury, tumors, bacterial, fungal, neurological, lung and respiratory inflammation, both esculetin and esculin are able to reduce the expression of various proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, thereby inhibiting the tissues damage caused by inflammation (Fig. 3, Table I and II). In conclusion, esculetin and esculin both have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, and may be used for the treatment or improvement of various diseases in the future.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of esculetin and esculin. TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; GSH, glutathione; NQO1, NADPH quinone oxidoreductase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase Pi; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; iNOS, inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; MPO, myeloperoxidase.

Table I.

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of esculetin.

| A, Antioxidant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Detail | Cell lines/model | Dosage | (Refs.) |

| Increase GPx, GR and GSH activities and inhibit GSSG accumulation | L-buthionine-sulfoximine-induced mouse cortical cells | 10-100 µM | (26) |

| Promote the expression of HO-1 | Helicobacter pylori urease-induced human vascular endothelial cells | 10 µM | (27) |

| Increase the levels of AST, ALT, SOD and glutathione and inhibit the accumulation of ROS and MDA | t-BHP-induced HepG2 cells | 10-20 µM | (28,29) |

| Decrease GPx and GSH depletion by inhibiting lipoxygenase expression | Zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 10-30 µM | (33) |

| Increase SOD, GSH and CAT expression levels, which inhibit activation of mitochondrial apoptosis pathway | Aβ25-35-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 0.1-10 µM | (34,35) |

| Increase SOD levels and decrease ROS levels and thus, inhibit activation of mitochondrial apoptosis pathway | Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced myocardial H9c2 cells | 5-20 µM | (36) |

| Induce SOD expression levels by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway | Leukemia NB4 cells | 20-500 µM | (31) |

| Activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway and induce the expression levels of multiple antioxidant genes, including HO-1, NQO1, GCLM, SOD1 and SOD2 | H2O2-induced human corneal epithelial cells | 20-100 µM | (37) |

| Activate the Nrf2 pathway and promote the expression of HO-1, SOD, GPx and CAT | 3T3-L1 preadipocytes | 12.5-100 µM | (38). |

| Activate the Nrf2 pathway and increase the expression levels of SOD, CAT and GPx | H2O2-induced Caco2 cells | 100-300 µg/ml | (39) |

| Activate Nrf2 signaling pathway and promote the expression of NQO1 and glutathione | Hydrogen peroxide-induced human hepatoma HepG2 cells | 10-25 µM | (40) |

| Restore the depleted GSH level and inhibit the production of ROS and MDA by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway | Ethanol-induced HepG2 cells | 10-100 µM | (41) |

| Activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway and promote expression of NQO1 by activating the ERK signaling pathway | H2O2-induced C2C12 myoblasts | 5 µM | (48,49) |

| Activate JAK2/STAT3 pathway | Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced myocardial H9c2 cells | 5-20 µM | (36) |

| Prevent nitrosative stress, increase GSH levels and inhibit the activation of caspase 3 | 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced neurotoxicity in mice | 0.5% w/w | (42) |

| Reduce the expression levels of autophagy-related factors (such as Bnip3, Beclin1, Pink1 and parkin) and apoptosis-related factors (such as p53, Bax and caspase 3) by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway | tBCCAO-induced mice | 20-80 mg/kg | (43) |

| Decrease immobility time and climbing time by restoring the antioxidant enzyme activities of CAT, SOD, GPx and GSH, and reducing GSSG levels | Forced swim task elicited in acute restraint stress-induced rats | 25 mg/kg | (44) |

| Increase SOD and CAT levels, and decrease MDA levels | CCl4-induced liver injury rats | 35 mg/kg | (45) |

| Restore total glutathione levels and increase the levels of NQO1, HO-1 and GSTP1 | N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced liver injury rats | 0.5% w/w | (46) |

| Increase expression levels of SOD, catalase, GPx, GST, non-enzymic antioxidants vitamin C and GSH, and reduce levels of TBARS, lipid hydroperoxides and co-conjugated diene | High-fat diet-induced kidney injury mice | 40 mg/kg | (47) |

| Restore SOD activity and reduce the amount of MDA | Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion rats | 50 mg/kg | (50) |

| Activate the Nrf-2 signaling pathway, and increase the activities of GSH, GPx and CAT | AlCl3-induced rat testicular tissue damage | 50 mg/kg | (51) |

| B, Anti-inflammatory | |||

| Detail | Cell lines/model | Dosage | (Refs.) |

| Inhibit the production of NO | IL-1β stimulated rat hepatocytes | IC50, 34 µM | (66) |

| Inhibit IL-6 production | TNF-α stimulated human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells | 10-100 µg/ml | (67) |

| Inhibit the release of NO, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1 | LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells | 1-10 µg/ml | (68-71) |

| Inhibit the production of IL-6, IL-8 and mucin-5AC by inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway | Histamine-induced human nasal epithelial cells | 10-40 µM | (72) |

| Inhibit expression of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α and IL-1β by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells | 12 µg/ml | (73) |

| Inhibit activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and reduce expression of MMP-9 and the binding activity of AP-1 | TNF-α induced vascular smooth muscle cells | 12.5-25 µg/ml | (74,75) |

| Reduce the IL-1β, COX-2 and TNF-α levels by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | Trimethyltin-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 30-200 µM | (76) |

| Decrease the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-12, TNF receptor and TRAIL by inhibiting the ERK1/2 and NF-κB signaling pathways | LPS-induced human retinal pigment epithelium cells | 0.78-50 µM | (77) |

| Inhibit the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23, myeloperoxidase and MPO by inhibiting the AKT/ERK/NF-κB and RORγt/IL-17 signaling pathways | LPS-induced acute lung injury mice | 20-40 mg/kg | (80,81) |

| Reduce the levels of MMP-9, macrophage inflammatory protein 2, IL-8 and IL-1β | Polyhexamethylene guanidine-induced pulmonary fibrosis mice | 10 mg/kg | (82) |

| Reduce the levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IgE, GATA3 and RORγt | Ovalbumin-induced asthma mice | 20 mg/kg | (83) |

| Inhibit the TLR4 signaling pathway and the expression levels of COX-2 and NOS2 | uPM10-exposed mice | 10 mg/kg | (84) |

| Decrease the levels of COX-2, iNOS and CINC-3 | TNBS-induced colitis rats | 100 mg/kg | (85) |

| Inhibit the production of NO, TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS and NLRP3 by inhibiting the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways | DSS-induced colitis rats | 5 mg/kg | (86,87) |

| Inhibit the expression of iNOS, TNF-α and IL-6 by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | Ethanol-induced gastric injury rats | 20-40 mg/kg | (88) |

| Downregulate the expression of Tlr4, Myd88, Nfkb, Tnfα, Il6, blood HbA1c, TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 | HFD-induced fatty liver mice | 0.01% w/w | (89) |

| Inhibit the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α | Zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced rats | 5-25 mg/kg | (90) |

| Reduce the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, iNOS and COX-2 by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | LPS-induced mice | 20-40 mg/kg | (91,92) |

| Reduce serum IgE, IgG2a and histamine levels, and inhibit the production of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13, IL-17 and IL-31 by inhibiting the STAT1 and NF-κB signaling pathways | House dust mite (dermatophagoides farinae extract) and 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced dermatitis mice | 2-50 mg/kg | (93) |

| Reduce the levels of IL-6, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α and IFN-γ by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mice | 50-100 mg/kg | (94) |

| Inhibit the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2 and iNOS by inhibiting the NF-κB and STAT1/STAT3 signaling pathways | Escherichia coli-induced sepsis mice | 20-60 mg/kg | (95) |

| Inhibit the expression of IL-1α, IL-1β and TNF-α by inhibiting the ERK1/2 signaling pathway | Dry eye rabbits | 0.05% of the diet | (96) |

| Inhibit the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | Isoproterenol induced myocardial toxicity rats | 10-20 mg/kg | (97) |

| Inhibit monoamine oxidase-A activity, and downregulate the IL-1β, TNF-α and TBARS levels | Reserpine-induced fibromyalgia mice | 2.5-10 mg/kg | (98) |

AP-1, Activating protein-1; COX-2, Cyclooxygenase 2; DPPH, 1,1-Diphenyl-2-Picrylhydrazyl; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; CINC-3, Cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-3; GATA3, GATA binding protein 3; GCLM, glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit; GR, Glutathione reductase; GSSG, Oxidized glutathione; HFD, High-fat diet; ICAM-1, Intracellular adhesion molecule-1; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; MPO, Myeloperoxidase; Myd88, Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor (NLR) family member pyrin domain-containing protein 3; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase 2; RORγt, Retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptor γt; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; STAT1, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; STZ, streptozotocin; tBCCAO, Transient bilateral common carotid artery occlusion; TBARS, Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; t-BHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide; TNBS, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; UVB, Ultraviolet radiation b.

Table II.

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of esculin.

| A, Antioxidant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Detail | Cell lines/model | Dosage | (Refs.) |

| Increase SOD and GSH expression levels and inhibit the expression of cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, p53, Bax and caspase 3 | Dopamine-induced human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells | 1-100 µM | (58) |

| Activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway to increase HO-1 expression levels and decrease the MDA content | LPS/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury mice | 10-40 mg/kg | (61) |

| Increase SOD levels and decrease MDA levels | Ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury rats | 12.5-50 mg/kg | (104) |

| Promote the expression of GPx | Adjuvant-induced arthritis rats | 10-40 mg/kg | (64) |

| Promote the expression of GPx | TNBS-induced colitis rats | 5-25 mg/kg | (53) |

| Promote the expression of SOD, GR and catalase | Prooxidant aflatoxin B-1-induced nephrotoxicity mice | 150 mg/kg | (56) |

| Increase the expression levels of GPx, SOD and catalase | STZ-induced type 2 diabetic mice | 10-50 mg/kg | (57) |

| B, Anti-inflammatory | |||

| Detail | Cell lines/model | Dosage | (Refs.) |

| Reduce the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 | Free fatty acid-induced HepG2 cells | 25-200 µM | (99) |

| Reduce the expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and iNOS by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway | LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | 300-500 µM | (100) |

| Inhibit p38/MAPK signaling pathway and downregulate MMP-9 levels and AP-1 binding activity | LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | 10-50 µM | (101) |

| Inhibit p38/MAPK, JNK and ERK1/2 signaling pathways and reduce the TNF-α and IL-6 expression levels | Mouse peritoneal macrophages | 1 µg-1 mg | (102) |

| Inhibit the expression levels of IL-12, IL-6 and TNF-α | Reserpine-induced depression mice | 50 mg/kg | (105) |

| Inhibit the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α | LPS-induced depressed mice | 20-40 mg/kg | (106) |

| Inhibit the MAPK signaling pathway and reduce the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, ICAM-1 and MCP-1 | STZ-induced diabetic rats | 30-90 mg/kg | (63) |

| Decrease the levels of NO and TNF-α | Hyperoxia-induced lung injury rats | 10-50 mg/kg | (61) |

| Inhibit the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulate the expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 | LPS-induced acute lung injury mice | 20-40 mg/kg | (103) |

| Inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulate the levels of IL-1β and TNF-α | DSS-induced colitis mice | 5-50 mg/kg | (100) |

| Inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulate the production of NO, TNF-α and IL-6 | Ethanol-induced gastric injury mice | 5-20 mg/kg | (104) |

| Inhibit the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway and downregulate the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1 and ICAM-1 | LPS-induced acute kidney injury mice | 25-100 mg/kg | (107) |

| Decrease the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, ICAM-1 and NO | STZ-induced diabetic rats | 30-90 mg/kg | (108) |

| Inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway and reduce the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β | LPS/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury mice | 10-40 mg/kg | (62) |

| Inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, downregulate the expression of TNF-α and IL-6, and increase the expression of the silent information regulator 1 | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis mice | 20-40 mg/kg | (99) |

| Decrease the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 | Adjuvant-induced arthritis rats | 10-40 mg/kg | (64) |

| Inhibit p38/MAPK, JNK and ERK1/2 signaling pathways and decrease the TNF-α and IL-6 levels | Xylene-induced rat paw swelling | 5-20 mg/kg | (102) |

| Inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway and reduce the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 | LPS-induced sepsis mice | 30 mg/kg | (109) |

SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; MDA, malondialdehyde; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; TNBS, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; Myd88, Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide.

Currently, the most studied components in the Chinese medicine Qinpi are esculetin and esculin, both of which belong to the coumarin group of components. It's worth looking into esculetin and esculin have relatively abundant experimental data from animals (including mice, rats, rabbits, etc.) in the treatment of a variety of diseases related to inflammation and oxidative stress, and therefore, these two components have a better prospect of clinical application. In the future research, the clinical study can be carried out to determine the esculetin and esculin in the clinical environment. antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. The development of esculetin and esculin as novel drugs for the treatment of inflammation and other associated diseases has the potential to advance the development of natural drug formulations for the treatment of inflammation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (grant no. 2023NSFSC1803), Innovative topics of Affiliated Sport Hospital of CDSU (grant no. LCCX22B01), and the Project of Sichuan Provincial Administration of TCM (grant nos. 2023MS271, 2023MS268).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

SJ conceived and revised the review. YT and QW performed the literature. LZ and KW drafted the review article and revised the manuscript. CW and MW reviewed and helped to modify the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chen Z, Zhong C. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:271–281. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller N, Myint AM, Schwarz MJ. Inflammation in schizophrenia. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2012;88:49–68. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398314-5.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Li Y, Sun C, Liu S, Yan Y, Pan H, Fan M, Xue L, Nie C, Zhang H, et al. Geniposide reduces cholesterol accumulation and increases its excretion by regulating the FXR-mediated liver-gut crosstalk of bile acids. Pharmacol Res. 2020;152(104631) doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández-Sánchez A, Madrigal-Santillán E, Bautista M, Esquivel-Soto J, Morales-González A, Esquivel-Chirino C, Durante-Montiel I, Sánchez-Rivera G, Valadez-Vega C, Morales-González JA. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:3117–3132. doi: 10.3390/ijms12053117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Xiang D, Xiang D, He W, Liu Y, Lan L, Li G, Jiang C, Ren X, Liu D, Zhang C. Baicalin protects against 17α-ethinylestradiol-induced cholestasis via the sirtuin 1/hepatic nuclear receptor-1α/farnesoid X receptor pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2020;10(1685) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler MS, Robertson AAB, Cooper MA. Natural product and natural product derived drugs in clinical trials. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1612–1661. doi: 10.1039/c4np00064a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarfraz I, Rasul A, Jabeen F, Younis T, Zahoor MK, Arshad M, Ali M. Fraxinus: A plant with versatile pharmacological and biological activities. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017(4269868) doi: 10.1155/2017/4269868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong S, Kim MM. Aesculetin inhibits cell invasion through inhibition of MMP-9 activity and antioxidant activity. J Life Sci. 2016;26:673–679. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li CX, Li JC, Lai J, Liu Y. The pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of esculin: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2022;36:2434–2448. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Xie Q, Li X. Esculetin: A review of its pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Phytother Res. 2022;36:279–298. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Q, Wang W, Li X, Lun J, Shao T. Ameliorative effect of esculetin against streptozotocin-induced experimental dementia via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 axis and suppression of NF-κB. Lat Am J Pharm. 2017;36:399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medina ME, Galano A, Alvarez-Idaboy JR. Theoretical study on the peroxyl radicals scavenging activity of esculetin and its regeneration in aqueous solution. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1039/c3cp53889c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhen AX, Piao MJ, Kang KA, Fernando PDSM, Kang HK, Koh YS, Hyun JW. Esculetin prevents the induction of matrix metalloproteinase-1 by hydrogen peroxide in skin keratinocytes. J Cancer Prev. 2019;24:123–128. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2019.24.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grover J, Jachak SM. Coumarins as privileged scaffold for anti-inflammatory drug development. RSC Adv. 2015;5:38892–38905. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diniz BS, Mendes-Silva AP, Silva LB, Bertola L, Vieira MC, Ferreira JD, Nicolau M, Bristot G, da Rosa ED, Teixeira AL, Kapczinski F. Oxidative stress markers imbalance in late-life depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Zhang Y, Ekunwe S, Yi X, Liu X, Wang H, Pan YM. Antioxidant activity and inhibition effect on the growth of human colon carcinoma (HT-29) cells of esculetin from Cortex Fraxini. Med Chem Res. 2011;20:968–974. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong GS, Yoon KH, Kim HC, Oh SH, Kim M, Kang DG, Lee HS, Kim YC. Cytoprotective constituents of the stem barks of Fraxinus rhynchophylla on mouse hippocampal HT22 cells and their antioxidative activity. Korean J Pharmacogn. 2007;38:287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HC, An RB, Jeong GS, Kim YC. 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging compounds of Fraxini Cortex. Nat Prod Sci. 2005;11:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vianna DR, Bubols G, Meirelles G, Silva BV, Da Rocha A, Lanznaster M, Monserrat JM, Garcia SC, Von Poser G, Eifler-Lima VL. Evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of synthesized coumarins. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:7260–7270. doi: 10.3390/ijms13067260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JM, Tseng TH, Lee YJ. An efficient synthesis of neoflavonoid antioxidants based on Montmorillonite K-10 catalysis. Synthesis. 2001:2247–2254. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsia CW, Lin KC, Lee TY, Hsia CH, Chou DS, Jayakumar T, Velusamy M, Chang CC, Sheu JR. Esculetin, a coumarin derivative, prevents thrombosis: Inhibitory signaling on PLCγ2-PKC-AKT activation in human platelets. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(2731) doi: 10.3390/ijms20112731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee BC, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Sim GS, Kim JH, Kim JH, Cho YH, Lee DH, Pyo HB, Choe TB, et al. Anti-oxidative and photo-protective effects of coumarins isolated from Fraxinus chinensis. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/BF02980270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potapovich MV, Metelitsa DI, Shadyro OI. Antioxidant activity of hydroxy derivatives of coumarin. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol. 2012;48:282–288. (In Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubio V, García-Pérez AI, Herráez A, Tejedor MC, Diez JC. Esculetin modulates cytotoxicity induced by oxidants in NB4 human leukemia cells. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2017;69:700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubio V, García-Pérez AI, Tejedor MC, Herráez A, Diez JC. Esculetin neutralises cytotoxicity of t-BHP but Not of H2O2 on human leukaemia NB4 cells. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017(9491045) doi: 10.1155/2017/9491045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CR, Shin EJ, Kim HC, Choi YS, Shin T, Wie MB. Esculetin inhibits N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotoxicity via glutathione preservation in primary cortical cultures. Lab Anim Res. 2011;27:259–263. doi: 10.5625/lar.2011.27.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Jesus Souza M, De Moraes JA, Da Silva VN, Helal-Neto E, Uberti AF, Scopel-Guerra A, Olivera-Severo D, Carlini CR, Barja-Fidalgo C. Helicobacter pylori urease induces pro-inflammatory effects and differentiation of human endothelial cells: Cellular and molecular mechanism. Helicobacter. 2019;24(e12573) doi: 10.1111/hel.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdallah H, Farag M, Osman S, Kim DH, Kang K, Pan CH, Abdel-Sattar E. Isolation of major phenolics from Launaea spinosa and their protective effect on HepG2 cells damaged with t-BHP. Pharm Biol. 2016;54:536–541. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1052885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong S, Heo H, Lee H, Lee M, Lee J, Park JH. Protective effects of the methanol extract from calyx of Diospyros kaki on alcohol-induced liver injury. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2021;50:339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sen Z, Weida W, Jie M, Li S, Dongming Z, Xiaoguang C. Coumarin glycosides from Hydrangea paniculata slow down the progression of diabetic nephropathy by targeting Nrf2 anti-oxidation and smad2/3-mediated profibrosis. Phytomedicine. 2019;57:385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubio V, García-Pérez AI, Herráez A, Diez JC. Different roles of Nrf2 and NFKB in the antioxidant imbalance produced by esculetin or quercetin on NB4 leukemia cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;294:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao Y, Shi W, Yao H, Ai Y, Li R, Wang Z, Liu T, Dai W, Xiao X, Zhao J, et al. An integrative pharmacology based analysis of refined liuweiwuling against liver injury: A novel component combination and hepaprotective mechanism. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12(747010) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.747010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JH, Jeong MS, Kim DY, Her S, Wie MB. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce lipoxygenase-mediated apoptosis and necrosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem Int. 2015;90:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao JL, Gong XY. Esculetin attenuates neurotoxicity induced by Aβ25-35 in SH-SY5Y cells via inhibiting oxidative stress and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Acta Pol Pharm. 2018;75:1177–1185. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pruccoli L, Morroni F, Sita G, Hrelia P, Tarozzi A. Esculetin as a bifunctional antioxidant prevents and counteracts the oxidative stress and neuronal death induced by amyloid protein in SH-SY5Y cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9(551) doi: 10.3390/antiox9060551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He Y, Li C, Ma Q, Chen S. Esculetin inhibits oxidative stress and apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes following hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;501:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, An Y, He X, Zhang D, He W. Esculetin protects human corneal epithelial cells from oxidative stress through Nrf-2 signaling pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2021;202(108360) doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y, Lee J. Esculetin inhibits adipogenesis and increases antioxidant activity during adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2017;22:118–123. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2017.22.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi T, Li T, Jiang X, Jiang X, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wang L, Qin X, Zhang W, Zheng Y. Baicalin protects mice from infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus via alleviating inflammatory response. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;108:1829–1839. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3AB0820-576RRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramaniam SR, Ellis EM. Esculetin-induced protection of human hepatoma HepG2 cells against hydrogen peroxide is associated with the Nrf2-dependent induction of the NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;250:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Yang J, Jeon J, Jeong HS, Lee J, Sung J. Hepatoprotective effect of esculetin on ethanol-induced liver injury in human HepG2 cells and C57BL/6J mice. J Funct Foods. 2018;40:536–543. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramaniam SR, Ellis EM. Neuroprotective effects of umbelliferone and esculetin in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:453–461. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu BR, Zhu LY, Chu J, Ma Z, Fu Q, Wei W, Deng X, Ma S. Esculetin improves cognitive impairments induced by transient cerebral ischaemia and reperfusion in mice via regulation of mitochondrial fragmentation and mitophagy. Behav Brain Res. 2019;372(112007) doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martín-Aragón S, Villar Á, Benedí J. Age-dependent effects of esculetin on mood-related behavior and cognition from stressed mice are associated with restoring brain antioxidant status. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;65:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atmaca M, Bilgin HM, Obay BD, Diken H, Kelle M, Kale E. The hepatoprotective effect of coumarin and coumarin derivates on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury by antioxidative activities in rats. J Physiol Biochem. 2011;67:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s13105-011-0103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subramaniam SR, Ellis EM. Umbelliferone and esculetin protect against N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Cell Biol Int. 2016;40:761–769. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prabakaran D, Ashokkumar N. Protective effect of esculetin on hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative damage in the hepatic and renal tissues of experimental diabetic rats. Biochimie. 2013;95:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han MH, Park C, Lee DS, Hong SH, Choi IW, Kim GY, Choi SH, Shim JH, Chae JI, Yoo YH, Choi YH. Cytoprotective effects of esculetin against oxidative stress are associated with the upregulation of Nrf2-mediated NQO1 expression via the activation of the ERK pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:380–386. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arora R, Sawney S, Saini V, Steffi C, Tiwari M, Saluja D. Esculetin induces antiproliferative and apoptotic response in pancreatic cancer cells by directly binding to KEAP1. Mol Cancer. 2016;15(64) doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0550-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiwei T, Ting Z, Chunhua M, Hongyan L. Suppressing receptor-interacting protein 140: A new sight for esculetin to treat myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. RSC Adv. 2016;6:112117–112128. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Türk E, Ozan Tekeli I, Özkan H, Uyar A, Cellat M, Kuzu M, Yavas I, Alizadeh Yegani A, Yaman T, Güvenç M. The protective effect of esculetin against aluminium chloride-induced reproductive toxicity in rats. Andrologia. 2021;53(e13930) doi: 10.1111/and.13930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owczarek A, Kolodziejczyk-Czepas J, Woźniak-Serwata J, Magiera A, Kobiela N, Wąsowicz K, Olszewska MA. Potential activity mechanisms of aesculus hippocastanum bark: Antioxidant effects in chemical and biological in vitro models. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10(995) doi: 10.3390/antiox10070995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Witaicenis A, Seito LN, da Silveira Chagas A, de Almeida LD Jr, Luchini AC, Rodrigues-Orsi P, Cestari SH, Di Stasi LC. Antioxidant and intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of plant-derived coumarin derivatives. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raghunath A, Nagarajan R, Sundarraj K, Palanisamy K, Perumal E. Identification of compounds that inhibit the binding of Keap1a/Keap1b Kelch DGR domain with Nrf2 ETGE/DLG motifs in zebrafish. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;125:259–270. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hassanein EHM, Sayed AM, Hussein OE, Mahmoud AM. Coumarins as modulators of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020(1675957) doi: 10.1155/2020/1675957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naaz F, Abdin MZ, Javed S. Protective effect of esculin against prooxidant aflatoxin B1-induced nephrotoxicity in mice. Mycotoxin Res. 2014;30:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s12550-013-0185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yao Y, Zhao X, Xin J, Wu Y, Li H. Coumarins improved type 2 diabetes induced by high-fat diet and streptozotocin in mice via antioxidation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;96:765–771. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao DL, Zou LB, Lin S, Shi JG, Zhu HB. Anti-apoptotic effect of esculin on dopamine-induced cytotoxicity in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:724–732. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wispriyono B, Jalaludin J, Kusnoputranto H, Pakpahan S, Aryati GP, Pratama S, Librianty N, Rozaliyani A, Taufik FF, Novirsa R. Glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels among junior high school students induced by indoor particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposure. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(2372) doi: 10.4081/jphr.2021.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaneko T, Baba N, Matsuo M. Protection of coumarins against linoleic acid hydroperoxide-induced cytotoxicity. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;142:239–254. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qi SP, Yu JC. Protective effect of esculin in hyperoxic lung injury in neonatal rats. La Am J Pharm. 2016;35:1177–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu A, Shen Y, Du Y, Chen J, Pei F, Fu W, Qiao J. Esculin prevents Lipopolysaccharide/D-Galactosamine-induced acute liver injury in mice. Microb Pathog. 2018;125:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song Y, Wang X, Qin S, Zhou S, Li J, Gao Y. Esculin ameliorates cognitive impairment in experimental diabetic nephropathy and induces anti-oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory effects via the MAPK pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:7395–7402. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng L, Yang L, Wang Z, Chen C, Su Y. Protective effect of Esculin in adjuvant-induced arthritic (AIA) rats via attenuating pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2015;61:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee H, Lee JH, Koh SJ, Park H. Bidirectional relationship between atopic dermatitis and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1385–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakajima A, Yamamoto Y, Yoshinaka N, Namba M, Matsuo H, Okuyama T, Yoshigai E, Okumura T, Nishizawa M, Ikeya Y. A new flavanone and other flavonoids from green perilla leaf extract inhibit nitric oxide production in interleukin 1β-treated hepatocytes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79:138–146. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2014.962474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim AR, Jin Q, Jin HG, Ko HJ, Woo ER. Phenolic compounds with IL-6 inhibitory activity from Aster yomena. Arch Pharm Res. 2014;37:845–851. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang F, Jia QW, Yuan ZH, Lv LY, Li M, Jiang ZB, Liang DL, Zhang DZ. An anti-inflammatory C-stiryl iridoid from Camptosorus sibiricus Rupr. Fitoterapia. 2019;134:378–381. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu J, Zhao L, Li N, Yang Y, Qu T, Ren H, Cui X, Tao H, Chen Z, Peng Y. Investigation of the active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms of Porana sinensis Hemsl. Against rheumatoid arthritis using network pharmacology and experimental validation. PLoS One. 2022;17(e0264786) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee MW, Kang SJ, Park M, Yoon JH, Han BH, Choi SE, Lee MW. Anti-oxidative and nitric oxide production inhibitory activities of phenoliccompounds from the fruits of actinidia arguta. Nat Prod Sci. 2006;12:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim Y, Park Y, Namkoong S, Lee J. Esculetin inhibits the inflammatory response by inducing heme oxygenase-1 in cocultured macrophages and adipocytes. Food Funct. 2014;5:2371–2377. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00351a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun B, Wang B, Xu M. Esculetin inhibits histamine-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines and mucin in nasal epithelial cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:821–827. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hong SH, Jeong HK, Han MH, Park C, Choi YH. Esculetin suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory mediators and cytokines by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB translocation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:3241–3246. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee SJ, Lee US, Kim WJ, Moon SK. Inhibitory effect of esculetin on migration, invasion and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in TNF-α-induced vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4:337–341. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xie C, Li Y, Gao J, Wang Y. Esculetin regulates the phenotype switching of airway smooth muscle cells. Phytother Res. 2019;33:3008–3015. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Song WJ, Yun JH, Jeong MS, Kim KN, Shin T, Kim HC, Wie MB. Inhibitors of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-2 attenuate trimethyltin-induced neurotoxicity through regulating oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Sci. 2021;11(1116) doi: 10.3390/brainsci11091116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ozal SA, Turkekul K, Gurlu V, Guclu H, Erdogan S. Esculetin protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and cell death. Curr Eye Res. 2018;43:1169–1176. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2018.1481517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Torres R, Mascayano C, Núñez C, Modak B, Faini F. Coumarins of haplopappus multifolius and derivative as inhibitors of lox: Evaluation in-vitro and docking studies. J Chil Chem Soc. 2013;58:2027–2030. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kwon OS, Choi JS, Islam MN, Kim YS, Kim HP. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase and skin inflammation by the aerial parts of Artemisia capillaris and its constituents. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:1561–1569. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0919-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee HC, Liu FC, Tsai CN, Chou AH, Liao CC, Yu HP. Esculetin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice via modulation of the AKT/ERK/NF-κB and RORγt/IL-17 pathways. Inflammation. 2020;43:962–974. doi: 10.1007/s10753-020-01182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen T, Guo Q, Wang H, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhang P, Meng S, Li Y, Ji H, Yan T. Effects of esculetin on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury via regulation of RhoA/Rho Kinase/NF-кB pathways in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic Res. 2015;49:1459–1468. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2015.1087643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oh SY, Kim YH, Kang MK, Lee EJ, Kim DY, Oh H, Kim SI, Na W, Kang YH. Aesculetin attenuates alveolar injury and fibrosis induced by close contact of alveolar epithelial cells with blood-derived macrophages via IL-8 signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5518) doi: 10.3390/ijms21155518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hongyan L. Esculetin attenuates Th2 and Th17 responses in an ovalbumin-induced asthmatic mouse model. Inflammation. 2016;39:735–743. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oh SY, Kim YH, Kang MK, Lee EJ, Kim DY, Oh H, Kim SI, Na W, Kang IJ, Kang YH. Aesculetin inhibits airway thickening and mucus overproduction induced by urban particulate matter through blocking inflammation and oxidative stress involving TLR4 and EGFR. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10(494) doi: 10.3390/antiox10030494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yum S, Jeong S, Lee S, Kim W, Nam J, Jung Y. HIF-prolyl hydroxylase is a potential molecular target for esculetin-mediated anti-colitic effects. Fitoterapia. 2015;103:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang SK, Chen TX, Wang W, Xu LL, Zhang YQ, Jin Z, Liu YB, Tang YZ. Aesculetin exhibited anti-inflammatory activities through inhibiting NF-кB and MAPKs pathway in vitro and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;296(115489) doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Witaicenis A, Luchini AC, Hiruma-Lima CA, Felisbino SL, Justulin LA Jr, Garrido-Mesa N, Utrilla P, Gálvez J, Di Stasi LC. Mechanism and effect of esculetin in an experimental animal model of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Inflamm. 2013;11:433–446. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu J, Wang H, Wen H, Zhang J, Wu A. Evaluation of antioxidant, antiulcer, and analgesic activities of esculetin. La Am J Pharm. 2021;40:1584–1591. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Choi RY, Ham JR, Lee MK. Esculetin prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver in diabetic mice fed high-fat diet. Chem Biol Interact. 2016;260:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Song WJ, Kim J, Shin T, Jeong MS, Kim KN, Yun JH, Wie MB. Esculetin and fucoidan attenuate autophagy and apoptosis induced by zinc oxide nanoparticles through modulating reactive astrocyte and proinflammatory cytokines in the rat brain. Toxics. 2022;10(194) doi: 10.3390/toxics10040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhu L, Nang C, Luo F, Pan H, Zhang K, Liu J, Zhou R, Gao J, Chang X, He H, et al. Esculetin attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammatory processes and depressive-like behavior in mice. Physiol Behav. 2016;163:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sulakhiya K, Keshavlal GP, Bezbaruah BB, Dwivedi S, Gurjar SS, Munde N, Jangra A, Lahkar M, Gogoi R. Lipopolysaccharide induced anxiety- and depressive-like behaviour in mice are prevented by chronic pre-treatment of esculetin. Neurosci Lett. 2016;611:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jeong NH, Yang EJ, Jin M, Lee JY, Choi YA, Park PH, Lee SR, Kim SU, Shin TY, Kwon TK, et al. Esculetin from Fraxinus rhynchophylla attenuates atopic skin inflammation by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory cytokines. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;59:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen Y, Zhang Q, Liu H, Lu C, Liang CL, Qiu F, Han L, Dai Z. Esculetin ameliorates psoriasis-like skin disease in mice by inducing CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9(2092) doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cheng YJ, Tian XL, Zeng YZ, Lan N, Guo LF, Liu KF, Fang HL, Fan HY, Peng ZL. Esculetin protects against early sepsis via attenuating inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and STAT1/STAT3 signaling. Chin J Nat Med. 2021;19:432–441. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(21)60042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jiang D, Liu X, Hu J. Topical administration of Esculetin as a potential therapy for experimental dry eye syndrome. Eye (Lond) 2017;31:1724–1732. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pullaiah CP, Nelson VK, Rayapu S, G V NK, Kedam T. Exploring cardioprotective potential of esculetin against isoproterenol induced myocardial toxicity in rats: In vivo and in vitro evidence. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;22(43) doi: 10.1186/s40360-021-00510-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Singh L, Kaur A, Garg S, Singh AP, Bhatti R. Protective effect of esculetin, natural coumarin in mice model of fibromyalgia: Targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines and MAO-A. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:2364–2374. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-03095-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang XD, Chen Z, Ye L, Chen J, Yang YY. Esculin protects against methionine choline-deficient diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by regulating the Sirt1/NF-κ B p65 pathway. Pharm Biol. 2021;59:922–932. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2021.1945112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tian X, Peng Z, Luo S, Zhang S, Li B, Zhou C, Fan H. Aesculin protects against DSS-induced colitis though activating PPARγ and inhibiting NF-кB pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;857(172453) doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Choi HJ, Chung TW, Kim JE, Jeong HS, Joo M, Cha J, Kim CH, Ha KT. Aesculin inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression via p38 mitogen activated protein kinase and activator protein 1 in lipopolysachride-induced RAW264.7 cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Niu X, Wang Y, Li W, Zhang H, Wang X, Mu Q, He Z, Yao H. Esculin exhibited anti-inflammatory activities in vivo and regulated TNF-α and IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages in vitro through MAPK pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;29:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tianzhu Z, Shumin W. Esculin inhibits the inflammation of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice via regulation of TLR/NF-κB pathways. Inflammation. 2015;38:1529–1536. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0127-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li W, Wang Y, Wang X, Zhang H, He Z, Zhi W, Liu F, Niu X. Gastroprotective effect of esculin on ethanol-induced gastric lesion in mice. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2017;31:174–184. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim YR, Park BK, Seo CS, Kim NS, Lee MY. Antidepressant and anxiolytic-like effects of the stem bark extract of fraxinus rhynchophylla hance and its components in a mouse model of depressive-like disorder induced by reserpine administration. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021;15(650833) doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.650833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen T, Zheng M, Li Y, Liu S, He L. The role of CCR5 in the protective effect of Esculin on lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive symptom in mice. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:755–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cheng X, Yang Y, Li W, Liu M, Zhang S, Wang Y, Du G. Esculin alleviates acute kidney injury and inflammation induced by LPS in mice and its possible mechanism. J Chin Pharm Sci. 2020;29:322–332. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang YH, Liu YH, He GR, Lv Y, Du GH. Esculin improves dyslipidemia, inflammation and renal damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15(402) doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0817-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]