Key Points

Question

Do bisexual and lesbian women have higher risks of premature mortality than heterosexual women?

Findings

Bisexual and lesbian participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II died an estimated 37% and 20% sooner, respectively, than heterosexual participants.

Meaning

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual women experienced earlier all-cause mortality, highlighting the need to address upstream individual and structural determinants of health disparities.

Abstract

Importance

Extensive evidence documents health disparities for lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) women, including worse physical, mental, and behavioral health than heterosexual women. These factors have been linked to premature mortality, yet few studies have investigated premature mortality disparities among LGB women and whether they differ by lesbian or bisexual identity.

Objective

To examine differences in mortality by sexual orientation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cohort study examined differences in time to mortality across sexual orientation, adjusting for birth cohort. Participants were female nurses born between 1945 and 1964, initially recruited in the US in 1989 for the Nurses’ Health Study II, and followed up through April 2022.

Exposures

Sexual orientation (lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual) assessed in 1995.

Main Outcome and Measure

Time to all-cause mortality from assessment of exposure analyzed using accelerated failure time models.

Results

Among 116 149 eligible participants, 90 833 (78%) had valid sexual orientation data. Of these 90 833 participants, 89 821 (98.9%) identified as heterosexual, 694 (0.8%) identified as lesbian, and 318 (0.4%) identified as bisexual. Of the 4227 deaths reported, the majority were among heterosexual participants (n = 4146; cumulative mortality of 4.6%), followed by lesbian participants (n = 49; cumulative mortality of 7.0%) and bisexual participants (n = 32; cumulative mortality of 10.1%). Compared with heterosexual participants, LGB participants had earlier mortality (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.64-0.84]). These differences were greatest among bisexual participants (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.51-0.78]) followed by lesbian participants (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In an otherwise largely homogeneous sample of female nurses, participants identifying as lesbian or bisexual had markedly earlier mortality during the study period compared with heterosexual women. These differences in mortality timing highlight the urgency of addressing modifiable risks and upstream social forces that propagate and perpetuate disparities.

This prospective cohort study compares the differences in time to mortality across sexual orientation in female nurses participating in the Nurses’ Health Study II.

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) women have systematically worse physical,1 mental,1,2 and behavioral health2,3 than heterosexual women. These disparities are due to chronic and cumulative exposure to stressors (including interpersonal and structural stigma4) that propagates and magnifies ill health throughout the life course, manifesting in disparities across a breadth of adverse health outcomes that tend to become more pronounced as individuals age (ie, weathering).5

National surveys started enumerating sexual orientation only within the past decade, and very few longitudinal cohort studies collect sexual orientation data. Therefore, despite extensive evidence of sexual orientation–related disparities in risk factors, few studies have been able to examine mortality differences by sexual orientation.6,7 Even fewer studies have focused on LGB women specifically, though some have demonstrated higher premature mortality risks for LGB women than heterosexual women.8,9 One study found the risk for premature mortality doubled among LGB women.8

Research on sexual orientation–related premature mortality has not elucidated differences within subgroups of LGB women; this is concerning because bisexual women experience unique stressors related to sexual orientation concealment,10,11 which may result in worse health.12 For example, bisexual women have higher magnitudes of disparities in substance use,13 cardiovascular disease,2 depression,14 and anxiety14 than lesbian women. Given these elevated risks, mortality disparities may be more pronounced among bisexual women than among lesbian women. A study conducted in Sweden found bisexual women had the highest hazard of all-cause mortality of any LGB subgroup under examination.15 To date, no studies examining mortality disparities in the US have differentiated between the sexual orientations of bisexual and lesbian.

We examined differences in mortality by sexual orientation in a longitudinal study of female nurses assessed over 3 decades. We hypothesized that LGB women would have earlier mortality than heterosexual women, but the risks would vary and bisexual women would have more pronounced mortality disparities.

Methods

The Nurses’ Health Study II is a longitudinal cohort of 116 429 female nurses born between 1945 and 1964 and recruited in 1989 (recruitment and survey details appear in eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1).16 This analysis refers to the participants as women, although gender identity was not assessed in this sample; all participants were recruited based on female sex and self-report of being female.

Eligible participants were those alive in 1995 (N = 116 149; >99% of original cohort) when sexual orientation was first assessed by asking, “Whether or not you are currently sexually active, what is your sexual orientation or identity? (Please choose one answer.)” Participants could choose 1 of the following responses: heterosexual; lesbian, gay, or homosexual (henceforth, lesbian); bisexual; none of these; or prefer not to answer. In the sensitivity analyses described below, associations with mortality for participants who were missing sexual orientation or responded as “none of these” or “prefer not to answer” were investigated.

The main outcome of interest was time to all-cause mortality from assessment of exposure. Mortality was determined in the Nurses’ Health Study II when (1) study personnel were notified about a participant’s death via correspondence with a close contact and the death was subsequently confirmed in the National Death Index (NDI) or (2) a participant had not responded to several questionnaires in a row (study personnel checked to see if they had a death record in the NDI).

The linkages to the NDI were confirmed via names and other identifying information such as social security numbers or birth dates. The linkages to the NDI were confirmed through December 31, 2019; however, ongoing death follow-up (eg, via family communication that was not yet confirmed with the NDI) was assessed through April 30, 2022. In the sensitivity analyses, only NDI-confirmed deaths (ie, through December 31, 2019) were examined.

Because younger cohorts endorse LGB orientation at higher rates,17,18 to account for the possibility of spurious associations due to cohort we adjusted for birth cohort, which was categorized in 5-year increments (ie, 1945-1949, 1950-1954, 1955-1959, 1960-1964). We chose not to further control for other health-related variables that vary in distribution across sexual orientation (eg, diet, smoking, alcohol use) because these are likely on the mediating pathway between LGB orientation and mortality. Therefore, controlling for these variables would be inappropriate because they are not plausible causes of both sexual orientation and mortality (ie, confounders) and their inclusion in the model would likely attenuate disparities between sexual orientation and mortality.19 However, to determine whether disparities persisted above and beyond the leading cause of premature mortality (ie, smoking20), we conducted sensitivity analyses among the subgroup of participants (n = 59 220) who reported never smoking between 1989 and 1995 (year when sexual orientation information was obtained).

The association between sexual orientation and mortality was quantified using time-to-event analyses. Specifically, unadjusted probability of mortality, stratified by sexual orientation, was first examined with Kaplan-Meier curves. Next, time to mortality was modeled using accelerated failure time models,21 which focus on comparisons between groups in terms of the relative timing of events rather than the risk or the hazard at a particular point in time (as is the case for the Cox model); comparisons based on the timing are likely more relevant to this study because LGB individuals are vulnerable to psychosocial and physical stressors that accumulate over the life course, which is consistent with the weathering hypotheses.5 However, as a secondary analysis, Cox proportional hazards models were used.

The time scale for the analyses was the number of years since exposure ascertainment (ie, 1995), with person-time right censored at the final date of mortality assessment (ie, April 30, 2022). After reviewing Cox-Snell residuals and an assessment of a variety of choices using the Akaike information criterion, the results are reported based on accelerated failure time models with a log-logistic distribution for the baseline error terms (ie, in the referent category of heterosexual women). Throughout, estimation and inference were based on maximum likelihood methods. In sensitivity analyses, estimates are shown using alternative distributions.

We tested for differences in time to death comparing LGB women vs heterosexual women, as well as comparing bisexual women vs lesbian women, using Wald tests with an α value of .05. We first examined the timing of mortality comparing LGB participants vs heterosexual participants and then further compared risks among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual participants. From these models, estimates (after exponentiating the slope parameters) can be interpreted as acceleration factors, which quantify how much sooner (if the estimated acceleration factor is <1.0) or later (if the estimated acceleration factor is >1.0) events occur in time.22,23

Sexual orientation was missing for 25 316 participants (22.0% of eligible sample). Thirteen percent of participants (n = 15 092) were missing data on sexual orientation due to item nonresponse (n = 14 478) or because they selected “none of these” or “prefer not to answer” (n = 614). Other participants did not return a 1995 questionnaire (n = 10 224; 9%). The results are presented using complete case analyses (n = 90 833). Sensitivity analyses were conducted across different patterns of missingness (additional details on missingness appear in eAppendix 2 in Supplement 1) as well as using multiple imputation to predict missing sexual orientation for all participants who responded to the 1995 survey. The analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

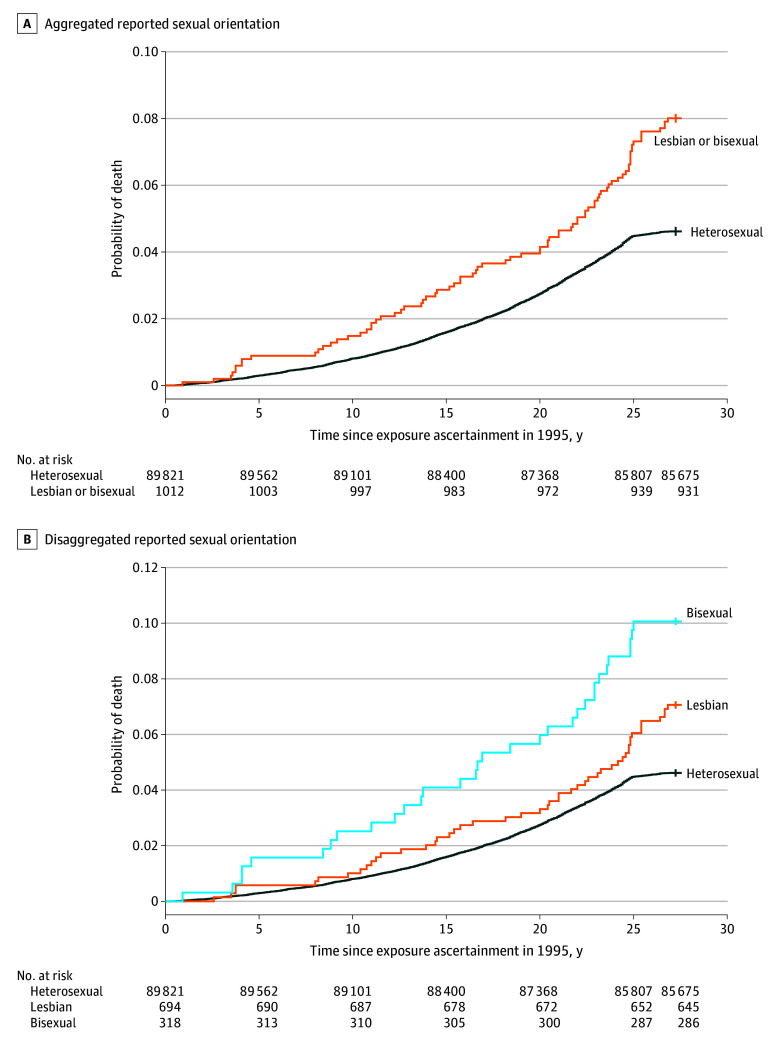

Among 90 833 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II with valid sexual orientation data, 89 821 (98.9%) identified as heterosexual, 694 (0.8%) identified as lesbian, and 318 (0.4%) identified as bisexual (Table). Overall, 4227 deaths were reported. The cumulative mortality over the 27-year study period was 4.6% (n = 4146) for heterosexual participants and 8.0% (n = 81) for LGB participants (corresponding to 7.0% [n = 49] for lesbian participants and 10.1% [n = 32] for bisexual participants). Heterosexual and LGB participants were equally likely to belong to minoritized racial or ethnic groups (both 6.1%). A larger proportion of heterosexual participants (65.4%) reported never smoking relative to LGB participants (46.1%).

Table. Distribution of All Study Variables Among Participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II by Reported Sexual Orientation.

| No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual (n = 89 821; 98.9%) |

Lesbian (n = 694; 0.8%) |

Bisexual (n = 318; 0.4%) |

|

| Birth cohort | |||

| 1945-1949 | 16 254 (18.1) | 164 (23.6) | 62 (19.5) |

| 1950-1954 | 30 011 (33.4) | 236 (34.0) | 118 (37.1) |

| 1955-1959 | 28 525 (31.8) | 211 (30.4) | 101 (31.8) |

| 1960-1964 | 15 031 (16.7) | 83 (12.0) | 37 (11.6) |

| Minoritized racial or ethnic identity | 5440 (6.1) | 34 (4.9) | 28 (8.8) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 47 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Asian | 1151 (1.3) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Black | 1203 (1.3) | 6 (0.9) | 7 (2.2) |

| Latino | 1477 (1.6) | 8 (1.2) | 8 (2.5) |

| Multiracial | 1503 (1.7) | 16 (2.3) | 11 (3.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 59 (0.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 83 689 (93.2) | 657 (94.7) | 287 (90.3) |

| Other or unknown race or ethnicity | 692 (0.8) | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.9) |

| Reported never smoking during 1989-1995 | 58 754 (65.4) | 320 (46.1) | 146 (45.9) |

| Died by April 2022 | 4146 (4.6) | 49 (7.0) | 32 (10.1) |

The mortality curves increased faster for LGB participants (P < .001 using the log-rank test; Figure 1). Compared with lesbian participants, there was more divergence for bisexual participants from heterosexual participants, but it did not reach statistical significance (P = .09 using the log-rank test for the comparison between bisexual participants and lesbian participants).

Figure 1. Probability of Death Through April 2022 in Participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II, by Reported Sexual Orientation.

The cohort-adjusted, model-based estimates for the sexual orientation differences in time to mortality (with adjustment for birth cohort) appear in Figure 2. The unadjusted estimates appear in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Compared with heterosexual women, LGB women had earlier mortality (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.64-0.84]). Examining subgroups within LGB women, bisexual participants died sooner (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.51-0.78]) than lesbian participants (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]), relative to heterosexual participants, though the results did not reach significance at the .05 level (adjusted acceleration factor, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.59-1.02] comparing bisexual women vs lesbian women).

Figure 2. Model-Based Estimates of Acceleration Factors for Time to Mortality From Baseline in Participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II.

All estimates were adjusted for birth cohort (1945-1949, 1950-1954, 1955-1959, and 1960-1964). The whiskers correspond to the 95% CI.

In a secondary analysis, disparities with interaction by race and ethnicity were examined. Disparities in mortality were higher in magnitude among racial and ethnic minority LGB women (acceleration factor, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.31-0.75]; eTable 2 in Supplement 1) than among non-Hispanic White, LGB women (acceleration factor, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.67-0.89). The patterning in differences in magnitude were consistent across lesbian and bisexual subgroups, but did not achieve statistical significance due to small numbers.

The secondary and sensitivity analyses with other model distributions for the mortality outcomes, using Cox proportional hazards models, and using only NDI-confirmed deaths appear in eTables 3, 4, and 5 in Supplement 1, respectively. Outcomes of models stratified by sources of missing and with imputed values for missing sexual orientation appear in eTables 6 and 7 in Supplement 1. The results of these analyses reported in Supplement 1 did not meaningfully vary from the results or interpretation shown here. However, the disparities for NDI-confirmed deaths were lower in magnitude due to a smaller number of deaths overall. Among those who reported never smoking (n = 59 220), LGB women had earlier mortality than heterosexual women (acceleration factor for all LGB women, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.62-0.96]; acceleration factor for lesbian participants, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.61-1.05]; acceleration factor for bisexual participants, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.50-1.04]). These estimates were very similar in magnitude and direction to the other analyses; however, the sample size was reduced, leading to very wide 95% CIs for the subgroups of LGB women.

Discussion

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual women died 26% earlier than heterosexual women in a longitudinal cohort of nurses followed up for 3 decades. Both lesbian and bisexual women experienced earlier mortality than heterosexual women; however, the risk was most pronounced among the bisexual participants who died 37% earlier (20% earlier for lesbian participants) than the heterosexual participants.

These dramatic differences highlight the burden of health disparities faced by LGB women. Although a robust literature has elucidated these disparities and processes, these findings are among the first to document the substantial effect these cumulative experiences have on premature mortality among LGB women. Prior research in this cohort demonstrated that LGB women had markedly higher risks of poor chronic and behavioral health than heterosexual women.1 In particular, risk factors for breast cancer and cardiovascular disease were elevated, with both lesbian and bisexual participants reporting twice as much alcohol and tobacco use as heterosexual participants.

Bisexual participants, in particular, had a 50% higher prevalence of hypertension than heterosexual participants. Consistent with findings from other samples,24,25 LGB women had elevated risks of depression as well. These prior health findings were documented when this cohort was in midlife (2 decades ago). Therefore, the majority of the mortality disparity found in the present study is likely attributable to preventable health behaviors and conditions that lead to a range of causes of death. These mechanisms are multifactorial and corroborated by the sensitivity analysis showing that the direction and magnitude of the mortality disparities were largely unchanged even among participants who reported never smoking. Although this analysis did not include cause of death because of extensive missingness (eTable 8 in Supplement 1), the leading causes of death for LGB women in this sample were cancer, respiratory disease, suicide, and cardiovascular disease, consistent with the elevated risk factors demonstrated 20 years ago in this same sample.

A key strength of this study is the ability to ascertain differential risks for bisexual and lesbian women. Critically, bisexual women had the most pronounced disparities in all-cause mortality in this sample. Even though this finding did not achieve statistical significance relative to lesbian women, the magnitude of the disparity was consistent with the study hypothesis, given that bisexual women have higher risks of substance use and have poorer physical and mental health than lesbian women.1,12,13,26,27,28,29 The underlying cause of these disparities is thought to be related to unique stressors that bisexual individuals face relative to other LGB groups. Specifically, bisexual orientation may be more concealable than lesbian orientation because many bisexual women have male partners. Therefore, stressors related to disclosure or staying closeted may be more salient for bisexual women, who are less likely than lesbian women to disclose their identities to their social networks.10,11 This can have both positive and negative effects on mental health.30,31

Nondisclosure has historically been thought of as a protective mechanism (ie, to buffer against interpersonal discrimination by passing); however, emerging evidence suggests that concealing one’s bisexual orientation may lead to more negative internalizing processes, confusion, and isolation from the queer community, which increase risks of adverse health behaviors to cope.32 Indeed, previous studies of mortality among LGB women found that the risks were most pronounced among women who did not disclose their sexual orientation to their immediate family.33 These findings affirm the importance of evaluating health and mortality risks for LGB women as well as the need to probe what specific factors may buffer the effects of adverse social forces that affect LGB women.

Health disparities for LGB women are consequences of structural and interpersonal marginalization, which are woven into the day-to-day lives of LGB women in ways that systematically undermine their access to health services and health-promoting behaviors.34,35,36 Lesbian, gay, and bisexual women who disclose their orientation experience high rates of discrimination by health care clinicians,37 leading them to forego or avoid preventive care.30 Furthermore, LGB women experience discrimination from employers, landlords, and service providers,31,38,39,40 leading to financial insecurity, housing instability, and food insecurity41,42 and thereby limiting financial and neighborhood resources for healthy options and health services,43 as well as widening disparities in health insurance.44

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual women often experience disapproval or rejection from their families,45 leading to limited social resources46,47,48,49 and unstable relationships50 that are disproportionately characterized by violence and abuse.51 To cope with these collective stressors, many LGB women self-medicate with tobacco, alcohol, or other drugs,52,53 which increase the risk of chronic health problems and lead to further avoidance of health care for fear of judgment.54,55 Collectively, these experiences of chronic stress may damage the body by dysregulating cardiovascular, metabolic, and immune systems, making LGB women more susceptible to disease and premature death.5 As a result, LGB women are vulnerable to increased risk of premature mortality attributable to a wide range of preventable causes of death, given that these social processes permeate health and health behaviors at all levels, and these health disparities are implicated in multiple disease pathways.

Given that biases in care based on sexual orientation occur at every point in the care continuum, clinicians and health care organizations at all levels, in every specialty, and for all ages have opportunities to intervene in ways that can reduce these disparities and contribute to better health outcomes. Actionable first steps include evidence-based preventive screening for LGB women without making assumptions based on orientation. For example, LGB women are less likely than heterosexual women to receive screening for sexually transmitted infections despite their increased risks because clinicians often assume that LGB women primarily have female sexual partners and are at lower risk.30,56,57,58,59

Screening and treatment referral for tobacco, alcohol, and other substance use need to be available without judgment.60 Recent estimates suggest that 70% of primary care clinicians do not feel comfortable meeting the needs of LGB individuals.61 Many clinicians do not receive mandatory, culturally informed training on caring for LGB patients.62 Training in cultural competency will benefit all clinicians who provide care for LGB individuals—because all clinicians likely do—and will facilitate more open dialogue regarding disclosure and risk assessment. At the structural level, discriminatory laws cause dramatic increases in suicidality, adverse health behaviors, adverse physical health, and experiences of discrimination.4 In its Declaration of Professional Responsibility, the American Medical Association calls for physicians to “advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”63

Limitations

These findings should be interpreted in light of their limitations. First, these findings may underestimate the true disparity in the general US population. The Nurses’ Health Study II is a sample of racially homogeneous female nurses with high health literacy and socioeconomic status, predisposing them to longer and healthier lives than the general public.64,65 The secondary analyses examining disparities demonstrated racial and ethnic minority LGB women had more pronounced disparities than non-Hispanic White LGB women; however, due to sample limitations this analysis did not fully explore the extent of these disparities. Although this sample’s relative homogeneity could adversely affect inference for some research questions, the ability to glean a mortality difference of this magnitude in a sample that otherwise has limited variability speaks to the strength of the association.

Second, the proportion of lesbian- and bisexual-identifying women in the analytic sample (0.8% and 0.3%, respectively) is lower than current population estimates of 1% of US adults (of any gender) identifying as lesbian and 4.2% identifying as bisexual.66 Even though the population proportion of LGB adults has been increasing over the past 3 decades (primarily driven by increases among young people) compared with contemporaneous national surveys from the 1990s, the current sample proportion of lesbian and bisexual women was low.18 This analysis did not adjudicate between a truly lower proportion of LGB women vs misclassification or nonresponse due to concealment and stigma. However, sensitivity analyses imputing missing sexual orientation information based on demographics and responses to subsequent surveys in 2009 and 2017 (when available) did not meaningfully influence the estimates of the disparity.

Third, even though this analysis did not examine changes in sexual orientation over time due to concerns related to inducing selection bias, only a small proportion of participants (3.7% of women identifying as LGB in 1995 and 6.8% of women identifying as heterosexual in 1995) reported a different sexual orientation at a later time point when the national climate was more accepting. Therefore, we anticipate that sexual orientation identities were largely stable over the duration of the study and that any misclassification based on using the 1995 measure underestimates the true disparity. However, the sexual orientation measure available in 1995 assessed only 3 (lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual) identities and no sexual behavior or attractions, which are important dimensions of sexual orientation and may be critical sources of heterogeneity that warrant future inquiry.

Conclusions

In an otherwise largely homogeneous sample of female nurses, participants identifying as lesbian or bisexual had markedly earlier mortality during the study period compared with heterosexual women. These differences in mortality timing highlight the urgency of addressing modifiable risks and upstream social forces that propagate and perpetuate disparities.

eAppendix 1. Recruitment strategy for the Nurses’ Health Study 2

eAppendix 2. Missingness

eTable 1. Unadjusted model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2

eTable 2. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, with interaction by race and ethnicity

eTable 3. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, modeled using alternative distributions for mortality outcomes

eTable 4. Model-based risk for survival by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, modeled using Cox Proportional Hazards models

eTable 5. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, using only NDI-confirmed deaths with linked data through 2019

eTable 6. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, including those who were missing measures of sexual orientation

eTable 7. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2 with missing sexual orientation values imputed

eTable 8. Cause-specific mortality among participants in Nurses’ Health Study 2, by reported sexual orientation

eReferences

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, et al. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13(9):1033-1047. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caceres BA, Makarem N, Hickey KT, Hughes TL. Cardiovascular disease disparities in sexual minority adults: an examination of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (2014-2016). Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(4):576-585. doi: 10.1177/0890117118810246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Martin K, Matthews AP, Johnson TP. Alcohol use among sexual minority women: methods used and lessons learned in the 20-Year Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women Study. Int J Alcohol Drug Res. 2021;9(1):30-42. doi: 10.7895/ijadr.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatzenbuehler ML, Lattanner MR, McKetta S, Pachankis JE. Structural stigma and LGBTQ+ health: a narrative review of quantitative studies. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9(2):e109-e127. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00312-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geronimus AT. Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Ordinary Life in an Unjust Society. Little, Brown Spark; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and mortality among US men aged 17 to 59 years: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1133-1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Mortality risks among persons reporting same-sex sexual partners: evidence from the 2008 General Social Survey-National Death Index data set. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):358-364. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laughney CI, Eliason EL. Mortality disparities among sexual minority adults in the United States. LGBT Health. 2022;9(1):27-33. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochran SD, Björkenstam C, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 years, 2001-2011. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):918-920. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arena DF, Jones KP. To “B” or not to “B”: assessing the disclosure dilemma of bisexual individuals at work. J Vocat Behav. 2017;103. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinstein BA, Dyar C, London B. Are outness and community involvement risk or protective factors for alcohol and drug abuse among sexual minority women? Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(5):1411-1423. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyar C, Taggart TC, Rodriguez-Seijas C, et al. Physical health disparities across dimensions of sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and sex: evidence for increased risk among bisexual adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(1):225-242. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuler MS, Collins RL. Sexual minority substance use disparities: bisexual women at elevated risk relative to other sexual minority groups. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107755. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Björkenstam C, Björkenstam E, Andersson G, Cochran S, Kosidou K. Anxiety and depression among sexual minority women and men in Sweden: is the risk equally spread within the sexual minority population? J Sex Med. 2017;14(3):396-403. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindström M, Rosvall M. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study in southern Sweden. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2020;1:100032. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, et al. Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1573-1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flores AR, Conron KJ; Williams Institute . Adult LGBT population in the United States. Accessed March 26, 2024. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/adult-lgbt-pop-us/

- 18.Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L. Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography. 2000;37(2):139-154. doi: 10.2307/2648117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds CA, Chen J, Charlton BM. Covariate adjustment in LGBTQ+ health disparities research: aligning methods with assumptions. Presented at: Society for Epidemiologic Research annual meeting; June 15, 2023; Portland, Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy M. Smoking remains leading cause of premature death in US. BMJ. 2014;348:g396. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein JP, van Houwelingen HC, Ibrahim JG, Scheike TH. Handbook of Survival Analysis. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2016. doi: 10.1201/b16248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei LJ. The accelerated failure time model: a useful alternative to the Cox regression model in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1992;11(14-15):1871-1879. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swindell WR. Accelerated failure time models provide a useful statistical framework for aging research. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44(3):190-200. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross LE, Salway T, Tarasoff LA, MacKay JM, Hawkins BW, Fehr CP. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Res. 2018;55(4-5):435-456. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King M, Semlyn J, Tai SS, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simoni JM, Smith L, Oost KM, Lehavot K, Fredriksen-Goldsen K. Disparities in physical health conditions among lesbian and bisexual women: a systematic review of population-based studies. J Homosex. 2017;64(1):32-44. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1174021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caceres BA, Brody AA, Halkitis PN, Dorsen C, Yu G, Chyun DA. Cardiovascular disease risk in sexual minority women (18-59 years old): findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2001-2012). Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(4):333-341. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma Y, Bhargava A, Doan D, Caceres BA. Examination of sexual identity differences in the prevalence of hypertension and antihypertensive medication use among US adults: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15(12):e008999. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.122.008999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis RJ, Ehlke SJ, Shappie AT, Braitman AL, Heron KE. Health disparities among exclusively lesbian, mostly lesbian, and bisexual young women. LGBT Health. 2019;6(8):400-408. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight DA, Jarrett D. Preventive health care for women who have sex with women. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(5):314-321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed AM, Andersson L, Hammarstedti M. Are gay men and lesbians discriminated against in the hiring process? South Econ J. 2013;79(3):565-585. doi: 10.4284/0038-4038-2011.317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz CT, Glatt EM, Stamates AL. Risk factors associated with alcohol and drug use among bisexual women: a literature review. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;30(5):740-749. doi: 10.1037/pha0000480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everett BG, Wall M, Shea E, Hughes TL. Mortality risk among a sample of sexual minority women: a focus on the role of sexual identity disclosure. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113731. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(5):521-548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer IH, Frost DM. Chapter 18: Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. In: Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation; 2013:252-266. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199765218.003.0018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Link BG, Phelan JC, Hatzenbuehler ML. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Health Inequality. Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayhan CHB, Bilgin H, Uluman OT, Sukut O, Yilmaz S, Buzlu S. A systematic review of the discrimination against sexual and gender minority in health care settings. Int J Health Serv. 2020;50(1):44-61. doi: 10.1177/0020731419885093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ro H, Olson ED. Gay and lesbian customers’ perceived discrimination and identity management. Int J Hospit Manag. 2020;84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casey LS, Reisner SL, Findling MG, et al. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(suppl 2):1454-1466. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozeren E. Sexual orientation discrimination in the workplace: a systematic review of literature. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;109. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Downing JM, Rosenthal E. Prevalence of social determinants of health among sexual minority women and men in 2017. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):118-122. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burn I. Not all laws are created equal: legal differences in state non-discrimination laws and the impact of LGBT employment protections. J Labor Res. 2018;39(4):462-497. doi: 10.1007/s12122-018-9272-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):125-145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Charlton BM, Gordon AR, Reisner SL, Sarda V, Samnaliev M, Austin SB. Sexual orientation–related disparities in employment, health insurance, healthcare access and health-related quality of life: a cohort study of US male and female adolescents and young adults. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e020418. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pistella J, Salvati M, Ioverno S, Laghi F, Baiocco R. Coming-out to family members and internalized sexual stigma in bisexual, lesbian and gay people. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(12). doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0528-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valentova M. How do traditional gender roles relate to social cohesion? focus on differences between women and men. Soc Indic Res. 2016;127(1):153-178. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-0961-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teo C, Chum A. The effect of neighbourhood cohesion on mental health across sexual orientations: a longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113499. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henning-Smith C, Gonzales G. Differences by sexual orientation in perceptions of neighborhood cohesion: implications for health. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):578-585. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0455-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsieh N. Explaining the mental health disparity by sexual orientation: the importance of social resources. Soc Ment Health. 2014;4(2). doi: 10.1177/2156869314524959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barrantes RJ, Eaton AA, Veldhuis CB, Hughes TL. The role of minority stressors in lesbian relationship commitment and persistence over time. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2017;4(2):205-217. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Published 2013. Accessed March 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf

- 52.Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Woody A. Minority stress, substance use, and intimate partner violence among sexual minority women. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17(3). doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldbach JT, Gibbs JJ. Strategies employed by sexual minority adolescents to cope with minority stress. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2015;2(3):297-306. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.St Pierre M. Lesbian disclosure and health care seeking in the United States: a replication study. J Lesbian Stud. 2018;22(1):102-115. doi: 10.1080/10894160.2017.1282283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charlton BM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun HJ, et al. Structural stigma and sexual orientation–related reproductive health disparities in a longitudinal cohort study of female adolescents. J Adolesc. 2019;74(1):183-187. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Missmer SA, et al. Influence of hormonal contraceptive use and health beliefs on sexual orientation disparities in Papanicolaou test use. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):319-325. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kerr DL, Ding K, Thompson AJ. A comparison of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual female college undergraduate students on selected reproductive health screenings and sexual behaviors. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(6):e347-e355. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Operario D, Gamarel KE, Grin BM, et al. Sexual minority health disparities in adult men and women in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2010. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e27-e34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blume AW. Advances in substance abuse prevention and treatment interventions among racial, ethnic, and sexual minority populations. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):47-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nowaskie DZ, Sowinski JS. Primary care providers’ attitudes, practices, and knowledge in treating LGBTQ communities. J Homosex. 2019;66(13):1927-1947. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1519304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pregnall AM, Churchwell AL, Ehrenfeld JM. A call for LGBTQ content in graduate medical education program requirements. Acad Med. 2021;96(6):828-835. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.American Medical Association . AMA Declaration of Professional Responsibility. Published online 2001. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ama-declaration-professional-responsibility

- 64.Fan Z, Yang Y, Zhang F. Association between health literacy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00648-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750-1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones JM. US LGBT identification steady at 7.2%. Published February 22, 2023. Accessed March 26, 2024. https://news.gallup.com/poll/470708/lgbt-identification-steady.aspx

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Recruitment strategy for the Nurses’ Health Study 2

eAppendix 2. Missingness

eTable 1. Unadjusted model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2

eTable 2. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, with interaction by race and ethnicity

eTable 3. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, modeled using alternative distributions for mortality outcomes

eTable 4. Model-based risk for survival by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, modeled using Cox Proportional Hazards models

eTable 5. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, using only NDI-confirmed deaths with linked data through 2019

eTable 6. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2, including those who were missing measures of sexual orientation

eTable 7. Model-based estimates of acceleration factors (AF), for time to mortality from baseline by reported sexual orientation among participants in the Nurses’ Health Study 2 with missing sexual orientation values imputed

eTable 8. Cause-specific mortality among participants in Nurses’ Health Study 2, by reported sexual orientation

eReferences

Data sharing statement