Abstract

Bacteria have acquired sophisticated mechanisms for assembling and disassembling polysaccharides of different chemistry. α-d-Glucose homopolysaccharides, so-called α-glucans, are the most widespread polymers in nature being key components of microorganisms. Glycogen functions as an intracellular energy storage while some bacteria also produce extracellular assorted α-glucans. The classical bacterial glycogen metabolic pathway comprises the action of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase and glycogen synthase, whereas extracellular α-glucans are mostly related to peripheral enzymes dependent on sucrose. An alternative pathway of glycogen biosynthesis, operating via a maltose 1-phosphate polymerizing enzyme, displays an essential wiring with the trehalose metabolism to interconvert disaccharides into polysaccharides. Furthermore, some bacteria show a connection of intracellular glycogen metabolism with the genesis of extracellular capsular α-glucans, revealing a relationship between the storage and structural function of these compounds. Altogether, the current picture shows that bacteria have evolved an intricate α-glucan metabolism that ultimately relies on the evolution of a specific enzymatic machinery. The structural landscape of these enzymes exposes a limited number of core catalytic folds handling many different chemical reactions. In this Review, we present a rationale to explain how the chemical diversity of α-glucans emerged from these systems, highlighting the underlying structural evolution of the enzymes driving α-glucan bacterial metabolism.

1. Introduction to Glucans in Chemistry and Biology

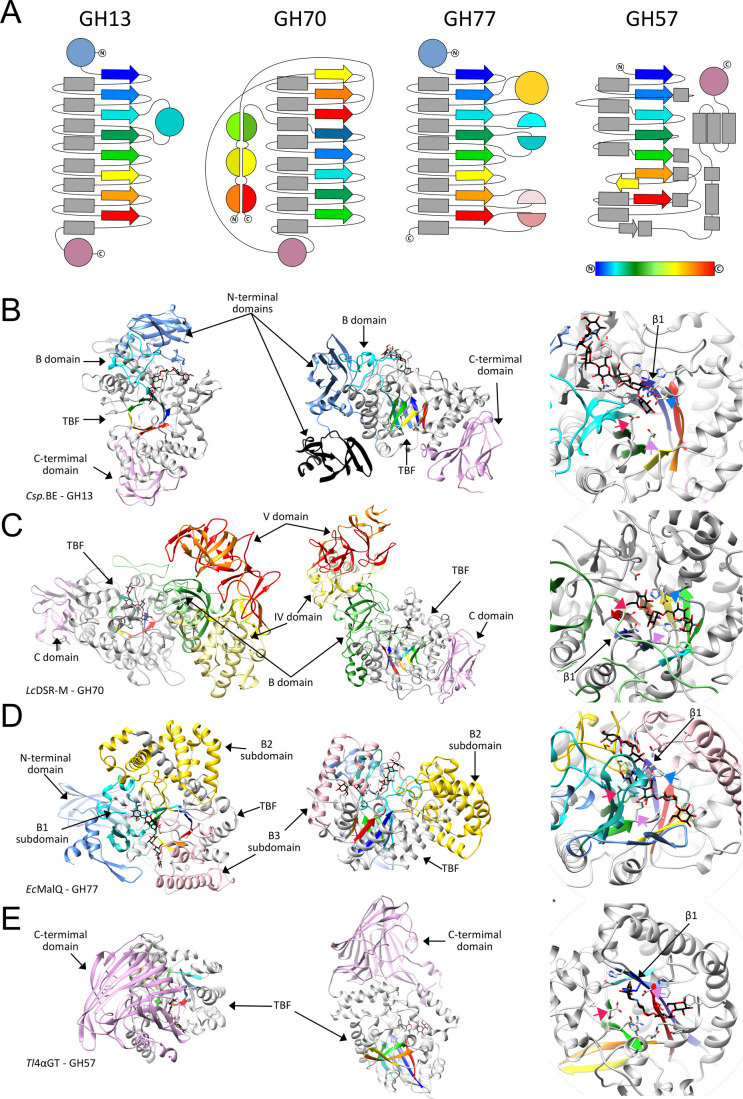

1.1. Historical Perspective

Glucans are glucose homopolymers that cumulatively represent one of the largest deposits of biological carbon in nature. These ubiquitous polymers, whose primary examples are cellulose, starch, and glycogen, play essential roles in the carbon cycle and biosphere transformations. The omnipresent nature of these polysaccharides makes us overlook they are the main constituent of natural raw materials gathered by man since prehistoric times; glucans are the main energy component in food crops and the main constituent of wood for fuel and shelter. Thus, the transformation of glucan materials spans the whole of human existence. Early records on the extraction of cellulose fibers for flax linen, fermentation of starchy grains for beer brewing, and purification of starch used as glue or cosmetic powder can be traced to ancient civilizations. Arguably, uncountable observations of natural and man-made glucan transformations predate modern investigations.

The beginning of glucan chemistry can be stated with the discovery of glucose as a substance purified from raisins by Andreas Marggraf in 1747 and the subsequent discovery of the conversion of starch to glucose by acids by Gottlieb Kirchhof in 1811.1 In 1833, Anselme Payen and Jean-François Persoz isolated a substance that accelerated the transformation of starch into maltose, the diastase, which was the first enzyme produced in concentrated form. In 1860, Pierre Berthelot isolated the enzyme invertase that hydrolyzes sugar cane into glucose and fructose. In 1837, Payen also discovered cellulose composed of glucose residues and isomeric with starch.2 Jacob Berzelius, who coined the concepts of catalyst and polymers, aware of Kirchhof and Payen’s findings, stated, “...chemical processes in living nature, we regard them in a new light. For example, since nature has placed diastase around the eyes of potatoes...we find that the insoluble starch in the tuber is changed to gum and sugar by catalytic power...” and “...One can hardly assume that this catalytic process is the only one...”3 These early findings paved the way to advance the view of life based on enzyme-driven chemical transformations.

Most of the early observations on the biochemistry of glucans were extracted from fermentation studies. Louis Pasteur discovered the production of dextran during the fermentation of wine, which Philippe van Tieghem later assigned to a bacterial activity.4 Adrian Brown found that bacteria can also synthesize cellulose.5 In 1865, Claude Bernard discovered glycogen as an energy reserve substance in liver tissue.6 The occurrence of glycogen in bacterial cells was later confirmed by Arthur Meyer.7 Wilhelm Kühne advance the concept of the separation between a ferment (zyme) and the active component for these conversions, the enzymes. In 1878, Wilhelm Kühne used for the first time the word “enzyme” to describe the ability of yeast to produce alcohol from sugars. In 1897, Eduard Buchner discovered that yeast extract with no living cells can form alcohol from a sugar solution. The conclusion was that biochemical processes do not necessarily require living cells, but are driven by special substances, enzymes, formed in cells, ending the “vitalist” view of living processes.

The modern vision of glucan and sugar biochemistry was established early in the 20th century. Emil Fisher in his Nobel lecture already stated that polysaccharides were nothing other than the glucosides of the sugars.8 This idea was confirmed by Walter Haworth, Edmund Hirst, and co-workers with the first description of the chemical architecture of several glucans, among other polysaccharides.9,10 Later, Haworth received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on carbohydrates, the structure of complex sugars, and the structure of Vitamin C. Previously in 1894, Fisher proposed the “lock-and-key” model for enzyme function,11−13 and soon after, Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten presented their seminal work on enzyme kinetics working on invertase.14 Jakub Parnas and Tadeusz Baranowski discovered phosphorolysis in glycogen metabolism,15 while Arthur Harden and Hans von Euler-Chelpin used fermentation of sugar and fermentative enzymes, identifying the role of phosphate in accelerating sugar fermentation, receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1929.16,17 Harden also reported that acellular fermentation was maintained due to the presence of glycogen, needing a factor “co-zymase”, the NADH.18 The studies of Gustav Embden, Otto Meyerhof, and Parnas on glucose and glycogen fermentation were critical in articulating the first reported pathway: glycolysis.19 Later in 1952, an alternative glycolytic pathway was described by Nathan Entner and Michael Doudoroff in Pseudomonas saccharophila.20 Charles Hanes observed the differential endo- and exohydrolytic action of α- and β-amylases.21 He also proposed the first tridimensional structure of a macromolecule, the helical amylose, and synthesized the first macromolecule in vitro: starch.22

Glycogen study was greatly propelled by Gerty Cori and Carl Cori, who reported the very first purification to homogeneity of a glycogen phosphorylase (GP).23 They discovered that GP can catalyze both the synthesis and degradation of glycogen, being activated by AMP.24 This activation was the first report of an allosteric effector, a concept developed by Jacques Monod, Jeffries Wyman, and Jean-Pierre Changeux.25 In 1956, Edwin Krebs and Edmond Fischer reported the discovery of the GP-kinase, revealing the importance of posttranslational modification in metabolic regulation.26 Meanwhile, Luis Leloir and co-workers revealed the origin of glycogen and starch metabolism with the discovery of the sugar-nucleotides, their synthetic enzymes, including the glycogen synthase.27,28 Earl Sutherland reported the mechanism of hormone-induced glycogen breakdown in the liver, linking the action of the endocrine system with glycogen metabolism.29

Altogether, glucans markedly impact and transverse our understanding of key chemical transformations in living matter. With this perspective, we review from the fundamentals of glucan chemistry to the biology of these polymers, providing a framework to conceptualize how the chemical diversity of α-glucans emerges from the structural evolution of the enzymatic machinery in bacteria.

1.2. The Origin of Glucan Unit: d-Glucose

The emergence of sugars under abiotic conditions from formaldehyde onto alumina and aluminosilicates into monosaccharides represents a model that could explain the primordial origin of these molecules.30 Sugars could also have been interconverted before living organisms arose, possibly giving rise to various types of monosaccharides.31,32 In present living organisms, 3 of the 16 possible aldohexoses are physiologically relevant, d-glucose, d-galactose, and d-mannose, all of which displaying d-isomery (Figure 1). d-Glucose was selected by nature as the central molecule in energy metabolism (Figure 1A). d-Glucose is the most abundant in all life kingdoms, pointing to a central role of this sugar at the origin of life (Figure 1B). There is no final understanding on how hexoses d-isomery prevailed in nature, and how d-glucose became the most common monosaccharide in life. d-Isomery asymmetry may have been selected and perpetuated with the emergence of proteo- or ribo-enzymes,33 as with other synthetic asymmetric catalysts.34 Nevertheless, symmetry-breaking events appear to be a distinct possibility within self-organizing chemical systems. This suggests that homochirality might have been a prevalent trait among the initial biopolymers, possibly evolving alongside their self-replication capabilities at the origin of protometabolism.33 The high intrinsic stability of d-glucose likely played a role in its selection. It is worth noting that the keto-hexose fructose can be converted to stable aldohexoses, i.e., glucose and mannose (2-epi-glucose), by Lobry de Bruyn-Van Ekenstein rearrangement35 (Figure 1D). Interestingly, d-glucose synthesis (gluconeogenesis), glycolysis, and the pentose pathways presumably existed in prebiotic metabolism as they have been assessed to be generated in abiotic conditions.36 In addition, genomic analysis of enzymes of the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway from archaea and hyperthermophilic bacteria support a gluconeogenic origin of metabolism.37 Arguably, the selection and centrality of d-glucose occurred in the transition between prebiotic and biotic world.

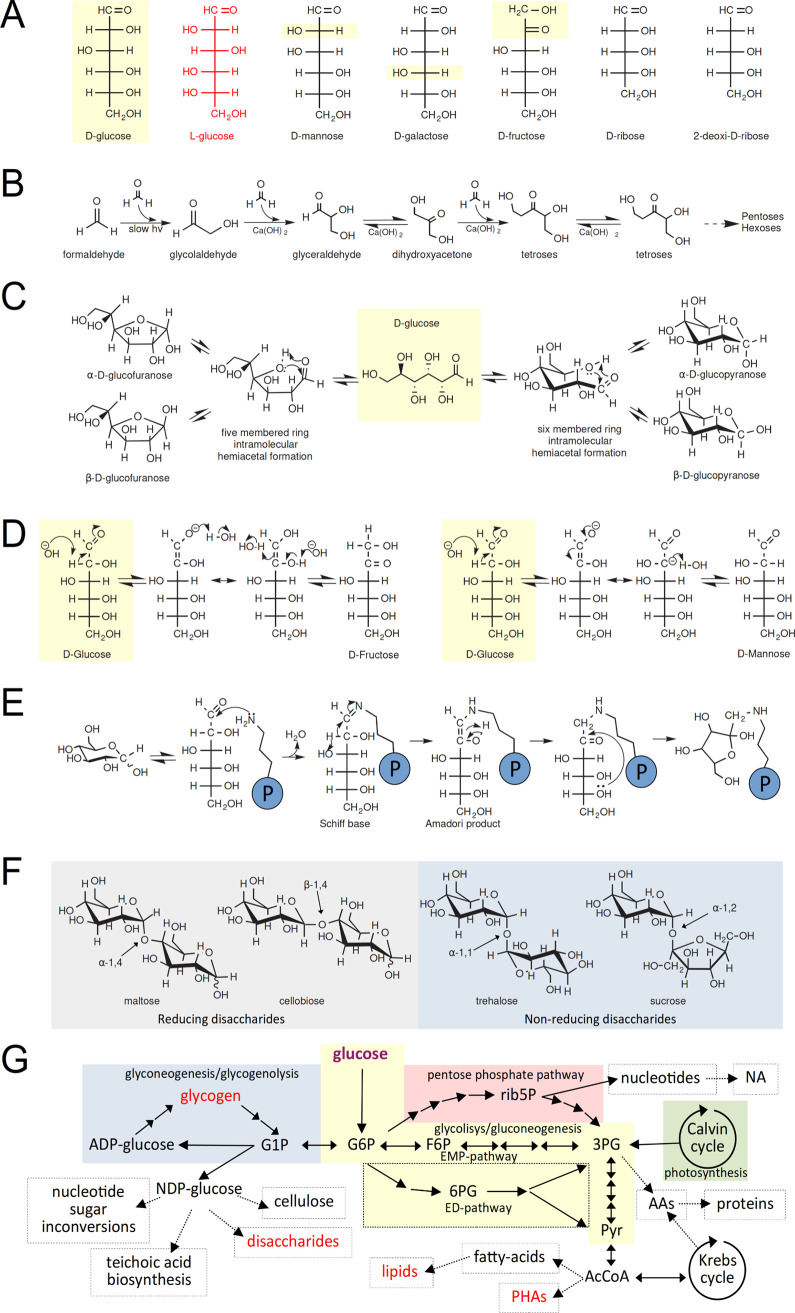

Figure 1.

Glucose, the central sugar in life. (A) Fischer projections of d-glucose (yellow shade), its non-biological occurring stereoisomer l-glucose (red), and the most common monosaccharides, hexoses and pentoses, found in nature. Differences between d-glucose with close related hexoses, d-mannose, d-galactose, and d-fructose, are highlighted in yellow. Note that the orientation of the last stereocenter is responsible for the d- and l-denominations of these sugars. (B) A schematic sequence of reactions of formaldehyde to form glycolaldehyde and subsequent aldoses and ketoses, the so-called formose reactions, that have been proposed as the abiotic origin of sugars. (C) Equilibrium of cyclization of linear d-glucose in solution. Glucose cyclizes, and the hydroxyl group on either position C4 or C5 undergoes an intramolecular reaction with the C1 carbonyl group of the aldehyde. As a result, the product formed is a hemiacetal resulting in either a 5- or 6-membered ring, in which the resulting hydroxyl group could present two orientations α- or β- concerning the ring plane. (D) Reactivity of d-glucose in solution leads to common sugars (i) d-fructose by an enediol rearrangement, and (ii) epimerization to d-mannose via an enolate intermediate. (E) Damaging of d-glucose with proteins, showing the reaction with lysine side chains via Schiff base formation and Amadori rearrangement, which ends in cyclic fructosamine. (F) Structure of common glucose disaccharides, showing maltose and cellobiose reducing disaccharides (grey shade) free anomeric hydroxyl group that can undergo a reducing reaction, while non-reducing disaccharides trehalose and sucrose (blue shade) compromise both anomeric carbons, therefore unavailable for reaction. (G) Overall metabolism of glucose. The glycolic and gluconeogenesis pathways (yellow), showing the classic Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway (EMP) and its variant Entner–Doudoroff pathway (ED; dashed box). This pathway integrates main pathways such as the Pentose phosphate pathway (PP; red shade), the tricarboxylic Krebs cycle, the photosynthetic Calvin cycle (green shade), and the glyconeogenesis/glycogenolysis pathways (blue shade). Other metabolic pathways are shown linked to this central energy metabolism (black dashed). Other molecules can serve as energy deposits (red letters). It is worth noting that glycogen is the energy closest storage molecule, directly linked to the initial point of glycolysis.

1.3. d-Glucose Biochemistry

d-Glucose participates in several acid–base catalyzed reactions, including mutarotation, enolization, and β-elimination, and also has reducing power. d-Glucose generally presents a cyclic pyranose conformation in equilibrium with minor amounts of tautomeric linear and cyclic furanose forms. The cyclization results from an intramolecular hemiacetal formation whose hydroxyl group can take two anomeric positions leading to the α-d-glucose and β-d-glucose forms that exist in a mutarotation equilibrium (Figure 1C). The β-d-glucose predominates because the hydroxyl group of the anomeric carbon is in the more stable equatorial position. Notably, the hemiacetal confers a highly reactive character to the C1 that often participates in d-glucose enzymatic transformations. d-Glucose is the preferred energy source through glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, mediating the biosynthesis of several key compounds in the cell (Figure 1G). d-Glucose is converted into other major hexoses as d-fructose by isomerization, and d-galactose and d-mannose by epimerization. In addition, d-glucose is converted via the pentose pathway to d-ribose, a central constituent of nucleic acids, while fatty acids and most amino acids can be synthesized from d-glucose. Therefore, d-glucose is a molecule that plays a central role in producing all major components of the cell: proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides. Supporting this notion, most organisms can synthesize d-glucose de novo via gluconeogenesis to maintain homeostasis.38 In addition, several microorganisms can grow using d-glucose as the sole energy and carbon source.39 Despite this importance, it is worth noting that free d-glucose accumulation in the cell can be harmful to the cell machinery due to its reactivity favors the formation of non-enzymatic covalent adducts with proteins and DNA via Schiff base and Amadori rearrangement40,41 (Figure 1E). In addition, high levels of intracellular glucose induce high osmotic pressure that is not compatible with cellular life. From an evolutionary perspective, the acquisition of mechanisms to safely store d-glucose may provide an advantage to a living organism when competing for environmental glucose.

1.4. Glucose Disaccharides

The condensation of monosaccharides to form disaccharides is the minimal event for the polymerization of sugars. The most common disaccharides comprise at least one d-glucose moiety, possibly due to the abundance of this monosaccharide in nature (Table 1). The biosynthesis of disaccharides involves the linkage between the anomeric carbon of a first sugar with any of the hydroxyl groups of a second monosaccharide forming a glycosidic bond. In principle, since the bonding can involve hydroxyl groups in different positions and in two anomeric configurations, the condensation between two monosaccharides can produce an extensive disaccharide repertoire. According to their redox capacity, disaccharides are classified in (i) reducing, where only one anomeric carbon is compromised in the linkage, and (ii) non-reducing, where both anomeric carbons are linked to each other (Figure 1F).

Table 1. Most Common Glucose Disaccharides.

| Name | Monosaccharide 1 (glycosyl) | Monosaccharide 2 | Glycosidic bond | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reducing | Trehalose | Glucose | Glucose | α(1→1)α |

| Sucrose | Glucose | Fructose | α(1→2)β | |

| Reducing | Maltose | Glucose | Glucose | α(1→4) |

| Isomaltose | Glucose | Glucose | α(1→6) | |

| Cellobiose | Glucose | Glucose | β(1→4) | |

| Lactose | Galactose | Glucose | β(1→4) |

The metabolism and function of disaccharides containing d-glucose are diverse across organisms. The non-reducing disaccharides trehalose and sucrose play a central role in energy storage in several living organisms due their stability,42 also having properties that aid the cells in enduring environmental stress, such as protecting membranes and proteins from freezing and dehydration.43 Furthermore, due to their small size, disaccharides are used to transport carbohydrates; trehalose is present in high concentration in insects’ hemolymph, while sucrose is transported in plants’ phloem. Trehalose synthesis is widely distributed in nature and found in Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota.44,45 Sucrose synthesis is restricted to plants and some photosynthetic bacteria,46,47 while most organisms can use it as a carbon and energy source. In contrast, disaccharides with a reducing end are not the best suited as storage compounds due to their reactive nature. This is the case for maltose and cellobiose, disaccharides that originate from the breakdown of glucans,48,49 and lactose, a special reducing disaccharide synthesized exclusively by mammals as the main energy component of milk, also fermented by microorganisms.50

1.5. Glucose Polysaccharides

Glucans are broadly classified according to the anomeric configuration of the d-glucose moieties in α-glucans, β-glucans, and mixed α/β-glucans (Figure 2).51 Glucans can also be classified as branched or unbranched polysaccharides according to the presence/absence of ramifications.51 Glucans can adopt a high degree of structural complexity, such as the ramified glycogen comprising α(1→4) backbones with α(1→6) branches while its topoisomer starch is composed of two different α-glucans, amylose, a linear unbranched α(1→4)-glucan, and amylopectin, a branched chain containing α(1→4) and α(1→6)-glucose linkages (Figure 2A). It is worth noting that, under a common denomination, a particular glucan can display structural variability, size, or branching level due to organism-specific biosynthetic machinery or the metabolic state of the organism.52,53 α-Glucans are generally viewed as polymers with an energy storage function in the cell, like glycogen and starch; however, they also play other important roles, including structural roles as exopolysaccharides, or as cell wall components. Similarly, β-glucans are usually associated with extracellular structural functions. This is well represented by cellulose, the most abundant biomolecule in the biosphere, and the main component of the plant cell wall (Figure 2A,B). β-Glucans can play other functions, including (i) cellulose as a fibrous structural component of bacterial biofilms, it forms a mechanically strong hydrogel with high water adsorption capabilities,54 (ii) cyclic β-glucans act as messengers in plant-microbe interactions,55 (iii) internal and external energy storages.56 The fungal cell wall is composed of a polysaccharide-based three-dimensional network that is continuously adapting to growth and environmental conditions and is essential for cell survival (1). The central core consists of a branched β(1→3)-glucan with 3% to 4% interchain linked (via β(1→4)-linkage) to chitin. Laminarin, a branched β(1→3)-glucan from brown algae, and paramylon, a β(1→3)-glucan synthesized by the flagellate Euglena, both are internal energy reserves with parallel function to glycogen. The curdlan-like β(1→3)-glucan exopolysaccharides are used as external energy storage molecules in Cellulomonas flavigena(57) (Figure 2A,B).

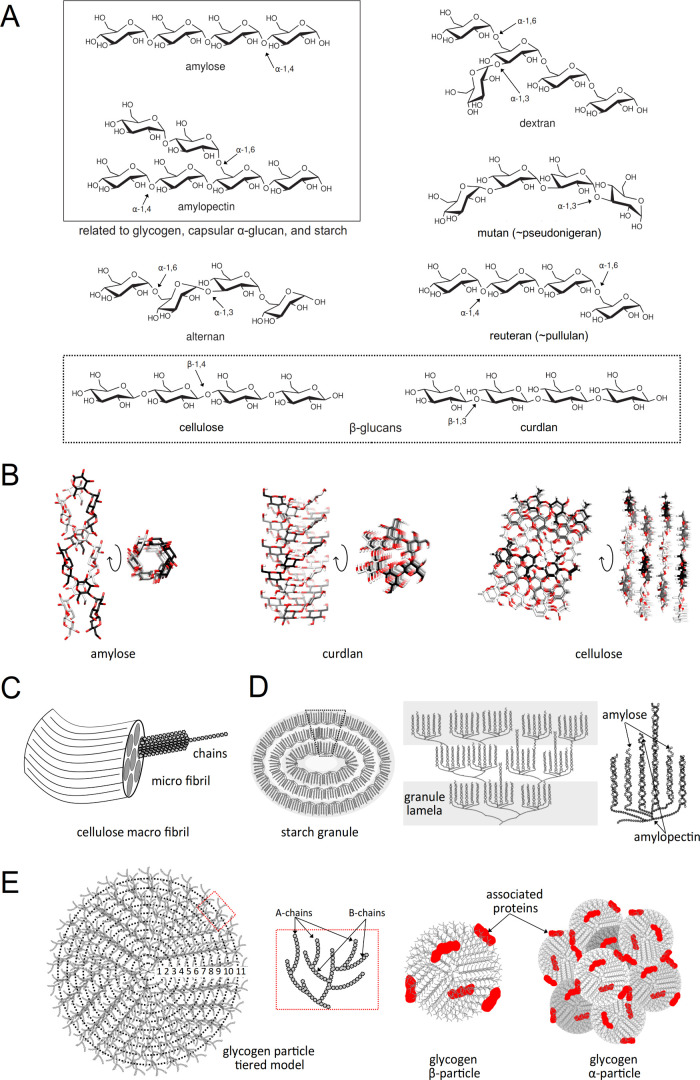

Figure 2.

Structure of glucans. (A) Chemical structure of common glucans produced by bacteria. Arrows indicate the main bonds found in amylose, amylopectin, dextran, altenan, and mutan, all representative α-glucans. Amylose and amylopectin are framed by a continuous line, indicating their structures can be found in glycogen, capsular α-glucans, and starch. Structures of cellulose and curdlan (framed by a dotted box) are also presented as examples of β-glucans. (B) Two perpendicular views of the three-dimensional structures obtained by X-ray crystal diffraction of (i) the double helical structure of the α-glucan amylose, (ii) the triple helical arrangement of curdlan, and (iii) the linear chains of cellulose, showing individual glucan chains in black, grey, and white carbon bonds. Structures have been obtained from PolySac3DB (https://polysac3db.cermav.cnrs.fr/home.html). (C–E) The biological organization of glucans. (C) Diagram showing the structural arrangement of macro and microfibrils formed by cellulose chains. (D) Diagrams showing the structural arrangement of starch, from left to right, (i) the starch granule, (ii) the lamellas, and (iii) the amylose and amylopectin complex. (E) Diagrams showing the structural arrangement of glycogen, from left to right, (i) the tiered model of glycogen, comprising the non-branched A-chains and branched B-chains (dashed red box), and (ii) the β-particle and its assembly product, the α particle. Proteins associated with particles are shown as red spots.

The chemistry and resulting architecture of glucans can certainly be correlated to the biological role they play. For instance, in (1→4) linkages, the α(1→4) anomeric configuration results in a helical structure of amylose, a component of glycogen and starch, while the β(1→4) anomeric configuration results in the classical straight chain polymer of cellulose (Figure 2B). This difference makes cellulose perfectly insoluble,58 forming crystalline matrices and fibers with high tensile strength and resistance to enzymatic digestion (Figure 2B,C), desired properties of a structural component. It is worth noting that the extra degrees of freedom provided by the rotation about the C5 and C6 bonds gives (1→6) linked homoglucans higher solution entropy values (Figure 2A).59 Altogether, glucan functions concern not solely the anomeric configuration (α or β) of the polymer but also the architecture and cellular localization. In the following sections, we will focus on α-glucans and related metabolism to discuss the biological machinery that generates their diversity.

2. Architecture of α-Glucans

2.1. Overview of Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic α-Glucans and Their Localization

Glycogen represents a form of soluble α(1→4)-glucan comprising α(1→6) branches of bacterial or heterotrophic eukaryotic origin60 (Figure 2A), whose main characteristic is to form non-crystalline particles with a wide range of size. Overall, glycogen synthesis is mainly based on the use of nucleotide-diphospho-sugar (NDP-sugar) donors, UDP-glucose in heterotrophic eukaryotes, and ADP-glucose in bacteria.61 In eukaryotic cells, glycogen particles present a buried protein, glycogenin (GN), that acts as the primer for glycogen synthesis, remaining covalently bound at the particle core.62 Different types of glycogen particles are observed in eukaryotic cells, classified as α-, β-, and γ-particles, representing different levels of α-glucan polymers organization63 (Figure 2E). The β-granules are individual glycogen particles comprising several protein-rich γ-particles that act as subunits, while α-granules are a structure of clustered β-granules glued together by the GN.64 The occurrence of “glycosomes”, dedicated dynamic organelles for glycogen metabolism, has been suggested,65 comprising a glycogen-protein complex, where the protein component provides the enzymatic machinery of the organelle, and glycogen is the product of its synthetic activity.65 Glycogen is also present as α- and β-granules in several bacterial species, including mycobacteria, streptomyces, and enterobacteria.66,67 However, since bacterial glycogen does not present any protein content to cluster the β-particles, the similar shape of eukaryotic and prokaryotic granules seems to appear as a result of convergent evolution.66 Starch can be considered a topoisomer of glycogen, primarily known for its ability to create insoluble crystalline structures. The starch granule is insoluble in water and densely packed, but still accessible to the plants’ metabolic enzymes. Plants and green algae form starch in plastid compartments such as the chloroplast of the leaf or amyloplasts.68 Plant starch consists of two types of molecules tightly clustered together, the linear α(1→4)-amylose and amylopectin containing α(1→6)-linked branches of α(1→4)-glucan69 (Figure 2D). One of the low energy conformations of the flexible amylose chain leads to single strands that readily form rigid double helices. These double helices associate in pairs, stabilized by hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces. These pairs associate to give the A or B structures, depending on their chain length and water content.70 On the other hand, Floridian starch is present in the cytoplasm of glaucophytes and red algae, forming crystalline granules with radially oriented fibrils and concentric layers of amylopectin.71,72 The metabolism of these two types of starch relies on different nucleotide sugar donors, ADP-glucose for the plastidial plant starch and UDP-glucose for the cytosolic Floridian starch.73 Interestingly, in cyanobacteria, α-glucan was observed in two forms, glycogen or crystalline semi-amylopectin, also called cyanobacterial starch,74,75 indicating an evolutionary transition from soluble α-glucan states toward crystalline α-glucan storages in photosynthetic organisms. These pieces of evidence in the evolution of organisms show that starch metabolism is important to trace the cyanobacterial origin of plastid endosymbionts into photosynthetic eukaryotes.76−78

α-Glucans are major components of the cell wall, capsules, or slimes on the exterior of fungi and bacterial cells, displaying diverse α-linkages.79 Fungi present several types of α-glucan polysaccharides as extracellular or cell wall components, mostly forming linear backbones, some made only with homogeneous linkages, such as α(1→3), α(1→4), or α(1→6), and also mixed linkages of alternating α(1→3) and α(1→6),80 like in alternan (Figure 2A). Solid-state NMR studies showed that α-glucans associations with other polysaccharides allow the formation of a rigid and impermeable scaffold protecting fungal cells from external stresses.81 Bacteria present two main types of α-glucans outside the cell envelope, capsular α-glucans and dextrans.82,83 The capsular α-glucans are present in Actinobacteria and resemble glycogen but with shorter α(1→4) linear chains,84 while dextrans refer to a large and diverse group of α-glucans with different linkages, including dextrans, alternans, mutans, and reuteran, that form polymer matrix biofilms providing protection to colonizing bacteria85−87 (Figure 2A).

2.2. The Architecture of α-Glucans in Bacteria

2.2.1. The Cytosolic Bacterial Glycogen

Glycogen represents the most important intracellular carbon and energy storage polymer in bacteria. Glycogen follows the three principles for a compound to be considered an energy reserve: (i) the compound accumulates when there is a surplus in energy, (ii) the compound is used when the energy supply from exogenous sources is insufficient for optimal maintenance of the cell, and (iii) the compound provides an advantage compared with an organism lacking this storage mechanism.85,88 Glycogen particles accumulate in bacteria preponderantly during the stationary phase, in the presence of an excess carbon source, and under environmental conditions of slow growth or no growth,89−91 playing a major role in awakening from dormancy.92Escherichia coli mutants lacking functional enzymes associated with glycogen biosynthesis can grow as well as their wild type parent strains, indicating that glycogen is not required for bacterial growth.88 However, glycogen accumulation prolongs the survival rate, resistance to starvation, low temperatures, and desiccation of bacteria compared to mutants without glycogen.93−95 These observations suggest that under conditions of no available carbon source, glycogen is probably utilized to preserve cell integrity, providing the energy required by the bacteria for maintenance.96

The glycogen architecture and chemical structure were originally investigated and discussed based on animal glycogen and plant starch. Early investigations based on stepwise enzymatic degradation97,98 revealed that these α-glucan polysaccharides are composed of irregular tree-like structures as originally proposed by Meyer99 instead of comb-like (each side branch arises from a single main branch) or laminated structures (branch arises from a preceding branch). This tree-like structure is composed of linear chains of α(1→4)-linkages with α(1→6)-linkages at branching points with an apparent random arrangement,66 in contrast to the high-ordered structures required to form crystalline arrays as observed in starch. The α(1→4)-linked chains’ average span comprised 8–12 glucosyl residues.91,100 This short chain length enhances bacterial viability by altering glycogen degradation rate.101 Bacterial and eukaryotic glycogen branching account for 7–10% of the total linkages.78 As a consequence, the branched polymer results in a highly water-soluble 3D fractal-like structure,102 allowing the storage of large amounts of glucose, without causing osmotic stress. Specifically, the high number of terminal non-reducing glucose units are readily accessible to hydrolytic enzymes in case the bacterium needs energy because of starvation. Biophysical characterization and visualization of glycogen extracted from bacteria by electron microscopy revealed a size of ca. 20 nm for β-particles and ca. 40 nm for α-particles, the latter showing a rosette-like appearance (Figure 2).66 α-Particles can break into β-particles. α-Particles can show two structural states, (i) fragile (high-density) and (ii) stable (low-density).66 In animals, it has been observed that the small β-particles degrade more easily to glucose than α-particles.103 Recent studies in bacteria indicate that α-particles states are modulated by the association of enzymes, accounting for fragile and stable states due to changes in average chain length, allowing for the control of glycogen storage and degradation.104

The internal structure and architecture of the glycogen particle were first conceptualized by the “tiered model” based on the molecular arrangement of the α-glucan presenting two chain types: unbranched A-chains and branched B-chains105−107 (Figure 2E). Specifically, branches in B-chains are uniformly distributed, comprising two branches that generate further A- or B-chains. Mathematical calculations indicate that glycogen can arrange in up to 12 concentric tiers.108 This branching spherical growth of the particle leads to a progressively more packed structure toward the periphery allowing only A-chains in the most external tier while preventing the addition of further tiers due to the lack of space for the enzymes to process the polysaccharide, therefore self-limiting the size. Thus, the glycogen particle displays a molecular size between 107 and 108 Da comprising ca. 55,000 glucose units distributed in 12 tiers, and 20 to 50 nm in size.107–109 While the “tiered model” offers a fascinating perspective on understanding the organization of glucan chains within glycogen particles, it is worth noting that a combination of experimental and computational approaches has challenged the fractal-like organization of glycogen particle.102 Surprising findings from small angle X-ray scattering analysis (SAXS) of β-particles have revealed a high density at the center of particles, contradicting the notion of a fractal-like organization and instead suggesting a randomly branched polymer.110 Recent Monte Carlo simulations of the glycogen particle biosynthetic process support these experimental data, showing that enzymatic activities and hindrance may control the chain length, radial density distributions, and particle size.111

2.2.2. The Chemical Structure of α-Glucans as Extracellular Components

Glycogen was first recognized as an intracellular polymeric material thought to function as an inert storage deposit for carbon and energy. In recent years, however, it became evident that some bacteria can deposit polymers with a glycogen-like architecture outside the cells. Furthermore, the synthesis and deposition of extracellular α-glucans exhibiting a variety of structures differing from glycogen have been long known from bacteria producing an extracellular matrix and forming biofilms. These extracellular α-glucans are either synthesized outside the cells employing secreted polymerases or are first synthesized intracellularly and subsequently secreted (Figure 3). Their structures and physicochemical properties differ strongly from intracellular α-glucans as they fulfill other functions outside of the cells (Table 2).

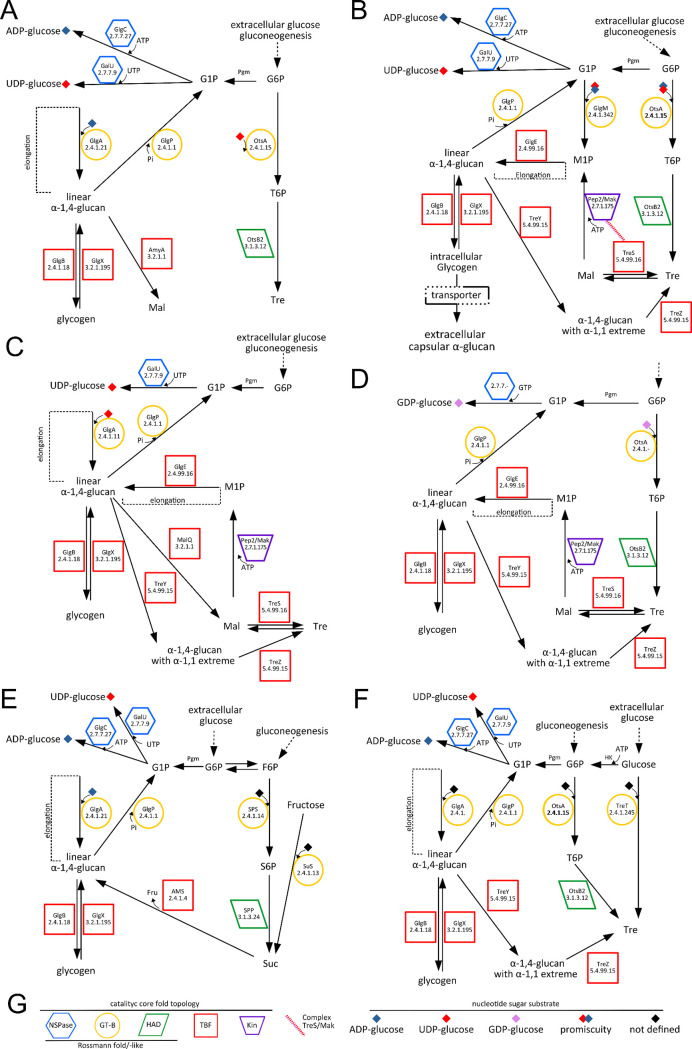

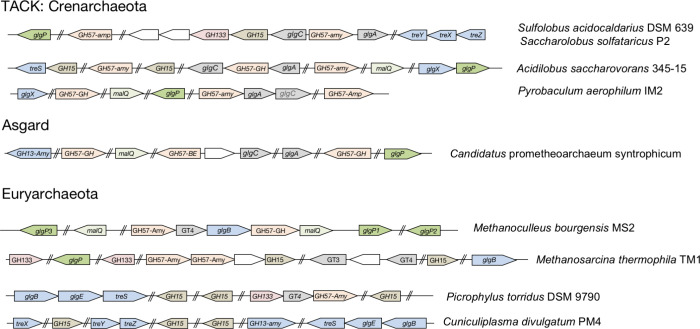

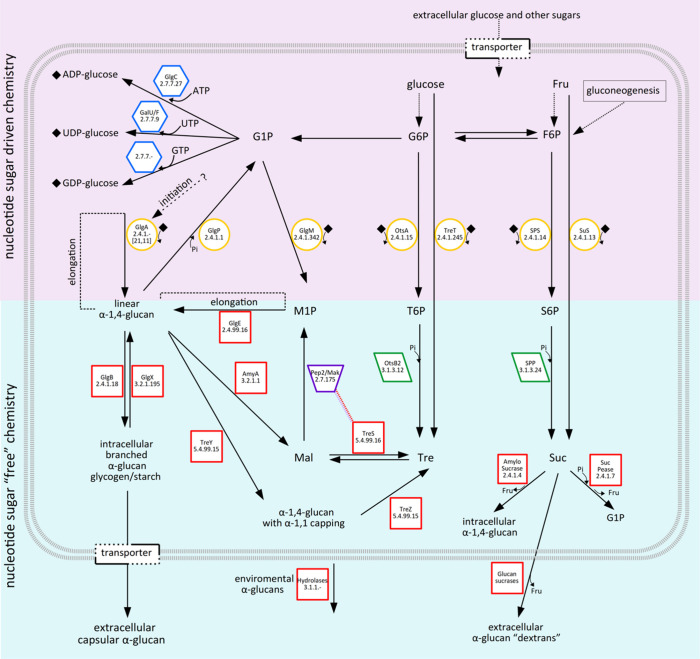

Figure 3.

Diversity of metabolic arrangements for α-glucan and disaccharide pathways in the context of prokaryotes. (A) The classical glycogen metabolism (GlgC-GlgA-GlgB) and independent trehalose metabolism (OtsA-OtsB) pathways in E. coli. (B) The glycogen metabolism via maltose 1-phosphate (M1P; GlgM-GlgE) is connected with the production of extracellular capsular α-glucan in M. tuberculosis. Essential wiring of the trehalose metabolism (TreS-Pep2/Mak; TreZ-TreY) permits the redundancy for the production of trehalose or α-glucan. (C) The glycogen metabolism in P. aeruginosa highlights the use of an UGPase (lack of GlgC/AGPase) for the GlgA-dependent biosynthesis of α(1→4)-glucan. It is worth noting the presence of GlgE, concurrent in the synthesis of α(1→4)-glucan via maltose 1-phosphate and TreS-Pep2/Mak. P. aeruginosa lacks a direct/dedicated pathway for the biosynthesis of trehalose, relying on maltose interconversions via the MalQ and TreZ-TreY pathways. (D) The glycogen metabolism of S. venezuelae relies on the trehalose pathway via an OtsA GDP-glucose-dependent synthesis. (E) An overall view of the cyanobacteria classical glycogen metabolism (GlgC-GlgA-GlgB). The sucrose synthesis is via SPS/SPP or SuS, and the alternative production of α(1→4)-glucan via amylosucrase (AMS). (F) An overall view of the archaea classical glycogen metabolism (GlgC-GlgA-GlgB). Note the alternative production of trehalose via TreT. (G) Charts showing the different folds of enzymes geometric symbols used for NDP-sugar pyrophosphorylases (blue hexagons), GT-B GTs (yellow circles), TIM barrel folds (red boxes), HAD domain phosphorylases (green parallelograms), and the maltokinase (violet trapezium). Nucleotide sugars are indicated with small colored rhombuses according to the legend.

Table 2. Representative α-d-Glucans Chemical Diversity and Their Distribution in Nature.

| Eukaryotes | Name | Geometry | Backbone | Branching | Location/Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animals, fungi and protozoa | Glycogen | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | Intracellular. Cytosol. Storage |

| Higher plants and green algae | Starch amylopectin | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | Intracellular. Plastids. Storage |

| Starch amylose | Linear | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | Intracellular. Plastid. Storage | ||

| Red algae, glaucophytes | Floridean starch | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | Intracellular. Cytosol. Storage |

| Fungi | Nigeran | Linear | Alternating (1→3)α(1→4)-α-d-glucan | Wall component | |

| Fungi | Pseudonigeran | Linear | (1→3)-α-d-glucan | Wall component | |

| Fungi | Pullulan | Linear | (1→4)α(1→4)(1→6)-α-d-glucan | Extracellular | |

| Prokaryotes | |||||

| Bacteria | Glycogen | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | Intracellular. Cytosol. Storage |

| Archaea | Glycogen | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | Intracellular. Cytosol. Storage |

| Bacteria | Capsular α-glucan | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | Extracellular Capsular component |

| Bacteria | Dextran | Branched | (1→6)-α-d-glucan | α(1→2,3,4) | Exopolysaccharide |

| Bacteria | Alternan | Branched | Alternating α(1→3)α(1→6)- d-glucan | α(1→3) | Exopolysaccharide |

| Bacteria | Mutan | Branched | α(1→3)- d-glucan | α(1→6) | Exopolysaccharide |

| Bacteria | Reuteran | Branched | (1→4)-α-d-glucan, including α(1→6) | α(1→6) | Exopolysaccharide |

| Bacteria | Amylose | linear | (1→4)-α-d-glucan | Exopolysaccharide |

2.2.3. The Capsule of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The ability to form a capsule surrounding the cells is a feature frequently found among pathogenic bacteria and, in most cases, an important virulence factor. In contrast to most other capsule-forming bacteria, the presence of an outermost capsular layer surrounding cells of the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been a matter of debate for many years. In contrast to typical bacterial capsules, the mycobacterial capsular layer is thin, not visible using light microscopy, and has a loosely-attached structure sensitive to agitation and the presence of detergents typically added to liquid culture media to minimize clumping of mycobacterial cells. More recently, ultrastructural studies employing advanced cryo-electron microscopy techniques could unambiguously prove the capsule’s existence in M. tuberculosis and visualize it in a close-to-native state.112 The mycobacterial capsule is mainly composed of neutral polysaccharides and additionally also contains proteins and lower amounts of lipids.113,114 The capsular polysaccharides identified in M. tuberculosis comprise three types of polymers: (i) a branched, high-molecular-weight α-d-glucan mainly comprising an α(1→4)-linked core with α(1→6)-branches every 5 or 6 residues by mono- and di- glucosides, with a molecular mass estimated to be ca. 100 kDa by gel permeation chromatography;113−116 (ii) a d-arabino-d-mannan heteropolysaccharide exhibiting an apparent molecular weight of 13 kDa;117 and (iii) a d-mannan homopolysaccharide with an apparent molecular weight of 4 kDa exhibiting α(1→6)-glycosidic linkages with α(1→2)-branches.117 Of the three mentioned polysaccharides, α-glucan is the major capsular polysaccharide constituent of M. tuberculosis, representing up to 80% of the extracellular polysaccharides.113,115,116 Using an α-glucan-specific monoclonal antibody, the production of extracellular α-glucan material has also been demonstrated to occur during infection for M. tuberculosis cells grown in mice.118 Structural analyses of the intracellular (i.e., glycogen) and extracellular α-glucans produced by slow-growing mycobacteria revealed a similar composition and architecture indicative of a common biosynthetic origin.116,117 However, depending on the analytical methods used, also differences were reported with capsular α-glucan possessing a higher molecular mass and a more compact spatial organization than the glycogen isolated from the same species, which has led to the speculation that specific enzymes might be responsible for the synthesis of each polymer.115 More recently, a combination of enzymatic characterizations and biochemical analyses of mutant strains resulted in the discovery of the metabolic network and configuration of pathways required for intra- and extracellular α-glucans in M. tuberculosis(119) (Figure 3B). This study unambiguously showed that both forms of α-glucan polymers are synthesized by the same enzymatic machinery. Synthesis occurs intracellularly, and a portion of the produced material is exported to yield the extracellular α-glucan that build up the capsule. As will be elaborated in more detail in section 3.2, α-glucan in M. tuberculosis is produced by iterative cooperation of the maltose 1-phosphate-dependent maltosyltransferase GlgE and the branching enzyme GlgB (Figure 3B).84 The polymer produced in this iterative process comprises C chains of DP ∼9, A and B chains of DP ∼7–8, and a mean number of branches per B chain of 1.2–1.6, which is considerably lower than the value of 1.8–1.9 reported for classical glycogens. Thus, the resulting molecule is a high-molecular weight glycogen-like polysaccharide of ∼5 × 106 Da but has a much less arboreal structure compared to glycogen described from other bacteria and from eukaryotic organisms and exhibits an A:BC chain ratio that is the smallest reported for α-glucans.84,120 Both the intracellular and extracellular polymers isolated from M. tuberculosis cells comprised β-particles that have diameters ranging from ∼30 to ∼60 nm and occasionally aggregate into larger α particles. The synthetic material produced in vitro using purified M. tuberculosis GlgE and GlgB proteins and maltose 1-phosphate as a substrate formed β-particles with similar diameter and morphology as the biological polymers isolated from M. tuberculosis cells.84 With an intracellular biosynthetic origin of all α-glucans in M. tuberculosis, the existence of a transport mechanism(s) for translocation of the polymer to the capsular space has to be postulated. However, such an α-glucan transporter has not been identified yet. It is tempting to speculate that the peculiar structure of M. tuberculosis α-glucan with a reduced degree of branching and a less arboreal architecture might be a feature facilitating export. However, no reports are available yet addressing the impact of α-glucan structure on extracellular deposition. M. tuberculosis has been shown to release extracellular vesicles that originate from the cytoplasmic membrane and contain cytosolic cargo. While it is theoretically conceivable that α-glucan is packed into the lumen of such vesicles for secretion, ELISA employing an α-glucan-specific monoclonal antibody could not detect this polysaccharide in purified vesicle preparations.121 Finally, theoretically it is possible that capsular α-glucan is produced extracellularly by secreted GlgE and GlgB proteins in a nucleoside-sugar-free biochemical reaction. However, this would necessitate secretion of substantial amounts of maltose 1-phosphate as substrate for the maltosyltransferase GlgE, but detection of this phosphosugar in cell-free culture supernatants has never been reported.

2.2.4. α-Glucans in Biofilm Forming Bacteria

Many bacteria are capable of forming biofilms, which are microbial communities characterized by their adhesion to solid surfaces of biotic and abiotic origin. An essential element in establishment and maintenance of a biofilm is the production of an extracellular matrix of exopolymeric substances (EPS) consisting of polysaccharides, proteins, DNA, and lipids. The EPS surrounds the microorganisms lending structural integrity, mechanical stability, and cohesiveness to the biofilm. The composition of the exopolymeric polysaccharides is diverse and can be complex comprising a mixture of several different types of molecules. Various types of α-glucans have been reported as a minor or major component of exopolymeric polysaccharides for some biofilm-producing bacteria (Table 2).

A group of bacteria notoriously forming α-glucan-containing biofilms are lactic acid bacteria. Synthesis of α-d-glucans by lactic acid bacteria occurs extracellularly using sucrose as a substrate and only requires secretion of single GH70 glucansucrase enzymes, which employ an α-retaining double displacement mechanism. The specificities of these glucansucrases differ, leading to production of various types of α-glucans with diverse linkages of the glucose units as well as the branching pattern. Thus, these extracellular α-glucans also exhibit very different physicochemical properties. Based on the linkage composition, these α-d-glucan polysaccharides are classified into dextran with mainly α(1→6) linkages, mutan with predominate α(1→3) linkages, alternan with alternating α(1→6) and α(1→3) linkages, and reuteran with mainly α(1→4) linkages.122−125 In addition, some lactic acid bacteria produce and secrete GH70 branching sucrases that can add single α(1→2) or α(1→4)-branched residue using dextran as an acceptor, resulting in highly branched polysaccharides with comb-like structure.126

Dextran is a homopolysaccharide which is composed of d-glucose monomers with mainly consecutive α(1→6) linkages in the backbone and branches connected via α(1→3) and occasionally α(1→2) and α(1→6) linkages (Figure 2A).127 The sucrose-dependent GH70 glucansucrase enzymes that synthesize dextran are termed dextransucrases.128Leuconostoc mesenteroides produces dextran consisting of 95% α(1→6) linkages and 5% α(1→3) branching linkages.123 Concerning the length of the branches, differing values have been reported depending on the studied strain of L. mesenteroides. 40% of the branching side chains of dextran produced by L. mesenteroides strain NRRL B-512 contain only one glucosyl unit, while 45% of the branching side chains possess two glucosyl units, and the remaining are longer than two glucosyl units.129 Similarly, branches from dextran obtained from strain L. mesenteroides NRRL B-1397 were reported to possess α(1→2) branches comprising just one glucosyl unit and longer α(1→3) branches comprising on average five glucosyl units,130 whereas dextran from L. mesenteroides strain NRRL B-512F was demonstrated to contain side chains up to 33 glucose residues.131 The molecular weight of dextran produced by dextransucrase enzymes from different bacteria generally varies in the range of 9–500 × 106 Da depending on the producing strains and enzymes. Dextran produced by L. mesenteroides exhibits a molecular weight of >2.0 × 106 Da, while that produced by Weissella cibaria was described to have a higher-molecular weight of 4 × 108 Da.128,132Oenococcus kitaharae DSM17330 synthesizes a dextran of over 109 Da, which is the largest dextran reported to date.133 Linear dextrans exhibiting exclusively α(1→6) linkages are very flexible polymers that are generally highly soluble in water. The water solubility of different dextrans is modulated by their branching linkage pattern and degree of branching.134 The high-molecular weight dextran from O. kitaharae DSM17330 was reported to exhibit a gel-like behavior.133 Cryo-TEM and dynamic light scattering analysis revealed that the dextran synthesized in vitro by the dextransucrase of L. mesenteroides strain D9909 displayed well-defined spheroidal particles in solution, with diameters ranging from 100 to 450 nm.135

Mutans are water-insoluble α-glucans, mainly consisting of consecutive α(1→3) linkages in the glucan chain backbone but may also contain a minority of consecutive α(1→6) linkages as well as α(1→3) and α(1→6) branches (Figure 2A).136 Mutans are generally produced from Streptococcus strains by specific sucrose-dependent GH70 glucansucrase enzymes termed mutansucrases and are associated with the development of dental caries.137 Structural analysis of a water-insoluble mutan produced by Streptococcus mutans strain 6715 revealed the presence of 67% of continuous α(1→3) linkages in the backbone and 33% α(1→6) linkages extending linearly from the branches.138Streptococcus salivarius strain HHT produced a water-insoluble mutan containing a high proportion of 80% of α(1→3) linkages and short side chains of α(1→4) and α(1→6) linkages.139 The molecular weight of mutans produced by S. mutans strains has been reported to be in the range of ca. 2.4 × 103 Da.140 Scanning electron microscopic examination of the mutan produced by S. mutans strain 20381 revealed a fibrillary structure consisting of granular formations.141

Reuterans are glucopolysaccharides found in Lactobacillus reuteri consisting of alternating consecutive α(1→4) linkages and single α(1→6) linkages in the glucan chain backbone as well as α(1→6) branches. The specific sucrose-dependent GH70 glucansucrase enzymes capable of forming alternating α(1→4) and α(1→6) linkages for synthesis of reuteran are termed reuteransucrases.142 Structural analysis of the reuteran produced by the reuteransucrase GtfA of L. reuteri strain 121 revealed a composition of 58% α(1→4) and 42% α(1→6) linkages, with a molecular weight of 34.6 × 106 Da.143,144 It is built up from maltose, maltotriose, and maltotetraose building blocks connected by single α(1→6) linkages, with some of the α(1→4) linked building blocks carrying α(1→6) branches.143 The reuteran polysaccharide produced by the reuteransucrase GtfO of L. reuteri strain ATCC 55730 is composed of 80% α(1→4) linkages and 20% α(1→6) linkages, suggesting the presence of longer stretches with consecutive α(1→4) linkages instead of alternating α(1→4) and α(1→6) linkages.128 Similarly, the exopolysaccharide produced by L. reuteri strain SK24.003 possesses predominantly α(1→4) linkages (80%) and a lower degree of α(1→6) linkages with a molecular weight of 43.1 × 106 Da and a radius of gyration of 43.6 nm.145 Structural modelling of reuteran from L. reuteri strain SK24.003 revealed that its alternating α(1→4)/α(1→6) backbone and branches are packed into a helical groove, generating a helical conformation in solution.146

Alternan is a high-molecular weight α-d-glucan homopolymer containing alternating α(1→6) and α(1→3) linkages (Figure 2A). The production of alternan has mainly been reported for strains of L. mesenteroides and Leuconostoc citreum. The specific sucrose-dependent GH70 glucansucrase enzymes capable of forming alternating α(1→6) and α(1→3) linkages for synthesis of alternan are termed alternansucrases.147 Alternan is a branched α-d-glucan with 7–11% 3,6-sustituted-d-glucosyl residues.148L. citreum strain ABK-1 encodes an alternansucrase that catalyzes the synthesis of an α-d-glucan with 60% α(1→6) linkages and 40% α(1→3) linkages.149 The molecular sizes of alternans produced by L. citreum strains SK24.002 and L3C1E7 were determined as 46.2 × 106 Da and 5.88 × 106 Da, respectively.150,151

In addition to typical glucansucrases, some lactic acid bacteria, particularly strains of L. citreum, have been reported to produce and secrete a distinct group of GH70 family enzymes, designated branching sucrases.126 Unlike typical glucansucrases, branching sucrases use sucrose as a substrate but do not catalyze α-d-glucan polysaccharide formation. They rather hydrolyze sucrose and transfer the glucosyl moiety to introduce branches into α-glucans produced by regular GH70 glucansucrases of the same bacterial strain.126,152 When dextran is provided as an acceptor substrate, branching sucrases catalyze the synthesis of α(1→2) or α(1→3) linked single glucosyl unit branches onto dextran, generating highly branched dextran with a comb-like structure, where up to 50% of the glucosyl monomers of the linear glucan backbone carry branches.126 The presence of α(1→2) or α(1→3) branches in branched dextran renders the polymer resistant to the hydrolysis by digestive enzymes of the gastrointestinal tract of mammals.153–155

In addition to capsular α-glucans present in M. tuberculosis as described above in section 2.2.3, extracellular α-d-glucan homopolymers with a glycogen-like structure comprising an α(1→4) linked core with α(1→6) branches have also been reported for some biofilm-forming bacteria. Species of the genus Neisseria express a GH13 amylosucrase, which is a sucrose-dependent α-amylase family enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of a high-molecular weight linear α(1→4) linked core.156 First, this enzyme has been identified in the cytosol in some Neisseria species, leading to intracellular glycogen production.157 Later, this enzyme was also found to be secreted by Neisseria polysaccharea isolated from the throats of healthy children leading to extracellular polymer formation.158In vitro, in the presence of an activator α-glucan starter molecule (e.g., glycogen), purified amylosucrase protein catalyzes the synthesis of a linear amylose-like polysaccharide composed of only α(1→4) glucosidic linkages using sucrose as the substrate, exhibiting a DP of ∼55.159,160 In contrast, the α-glucan isolated from cells of N. polysaccharea, N. perflava, and others isolated from human dental plaque have been reported to comprise between 6 and 9% α(1→6)-linked branches,161−164 indicative of the presence of a branching enzyme acting on the linear α(1→4)-linked polysaccharide produced by GH13 amylosucrases.165 While initially thought to be restricted to species of the genus Neisseria, more recently GH13 amylosucrases have also been described for bacteria outside this genus such as various Deinococcus species, Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus, Alteromonas macleodii, Methylobacillus flagellatus, the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp., and the halotolerant methanotrophic bacterium Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum, indicating that this mechanism of producing glycogen-like α-glucan is more widespread.126

For members of the genus Aeromonas, which are Gram-negative, water-borne bacteria that are ubiquitously found in aquatic environments, a surface α-glucan consisting of α(1→4)-linked glucosyl units with α(1→6)-branches has been described for A. piscicola AH-3 and Aeromonas hydrophila strains AH-1 and PPD134/91.166−168 The α-glucan is produced intracellularly by the UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGPase) GlgC and the glycogen synthase GlgA. In contrast to the classical GlgC-GlgA pathway for glycogen biosynthesis, Aeromonas GlgC synthesizes UDP-glucose instead of ADP-glucose, while Aeromonas GlgA can utilize both UDP-glucose and ADP-glucose as substrates.166−168 For A. hydrophila AH-3, it was demonstrated that the intracellularly produced glycogen-like α-glucan is exported to the cell surface involving WecP,168 which is the enzyme catalyzing the transfer of N-acetylgalactosamine to undecaprenyl phosphate to initiate O-antigen lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis.169 The exported glycogen-like α-glucan is attached to the surface involving the O34-antigen polysaccharide ligase WaaL,168 which is the enzyme that ligates the O-antigen LPS to the LPS-core.170

Presence of extracellular α-glucan consisting of α(1→4)-linked glucosyl units with α(1→6) branches has further been described for the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens.171 In addition, an α(1→4)-linked α-glucan has been identified as part of the EPS produced by the biofilm-forming plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae strain NZ V-13.172 While α-glucan biosynthesis has not been investigated in P. fluorescens and P. syringae pv. actinidiae yet, the configuration of pathways leading to α-glucan formation in the related bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 has recently been elucidated, revealing a central role of the GlgE pathway in this organism.173 Thus, it is likely that α-glucan formation occurs on a similar pathway in all Pseudomonads (Figure 3C). For P. aeruginosa PAO1, however, it is unclear whether intracellularly produced α-glucan is secreted to become surface-exposed similar to P. fluorescens and P. syringae pv. actinidiae.

3. α-Glucan Metabolism

3.1. The Classical GlgC-GlgA Pathway in Bacteria

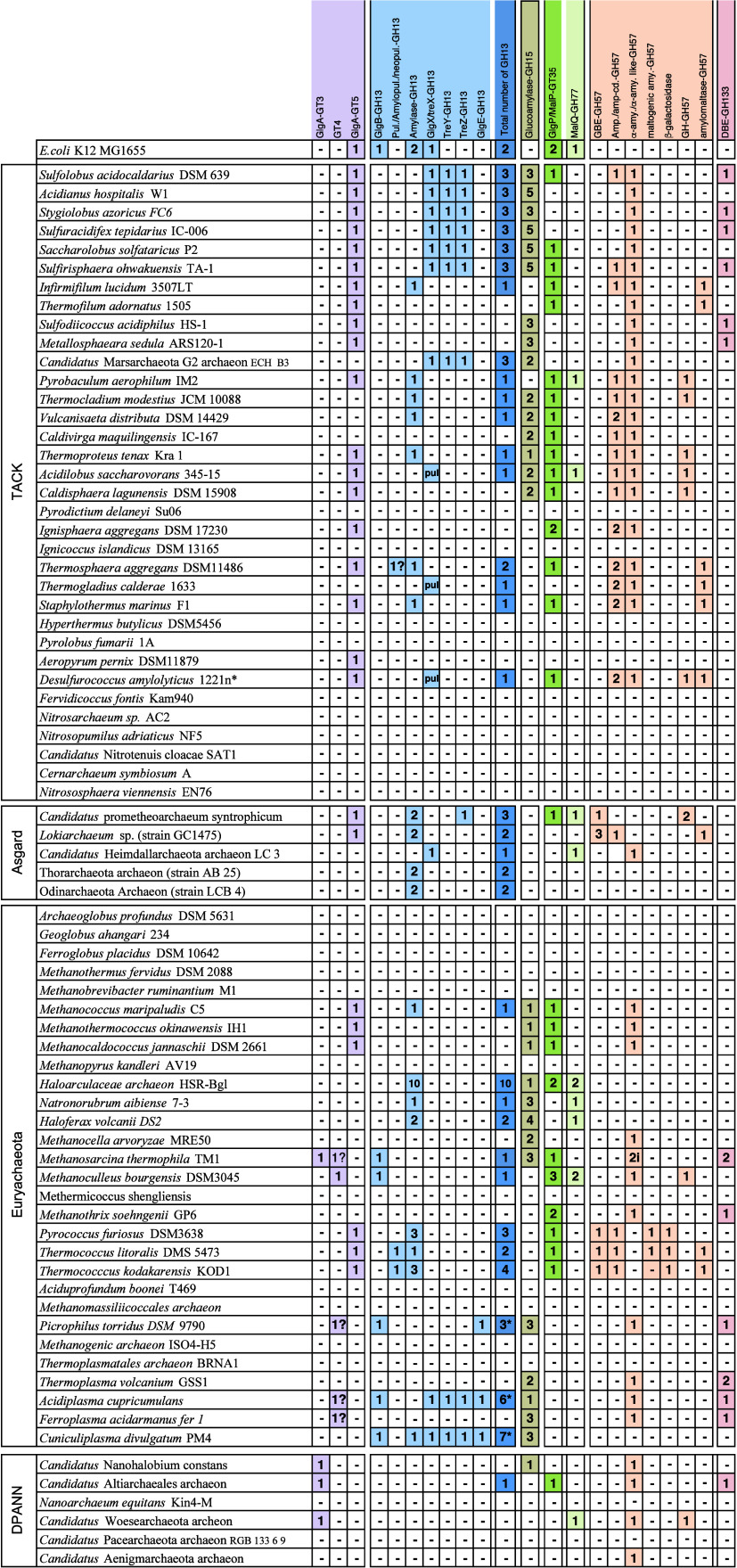

The classical bacterial glycogen metabolic pathway involves genes encoding the action of five enzymes. Three enzymes are involved in the anabolic route, (i) AGPase (glgC) activating the glucose moiety, (ii) glycogen synthase (glgA; GS) generating α(1→4)-linked linear glucose chains, and (iii) glycogen branching enzyme (glgB; GBE) introducing α(1→6)-linked glucan branches; while two enzymes are involved in the catabolic route, (i) glycogen debranching enzyme (glgX; GDE) cleaving α(1→6)-linked glucan branches, and (ii) glycogen phosphorylase (glgP; GP)61 (Figure 3A). Genes involved in the classical pathway of glycogen metabolism are often clustered in a single operon.174−177 In the case of the paradigmatic E. coli, these genes are located in a cluster of 15 kb organized in two neighboring operons.89,91,178 The most frequent order for the glgA/B/C triplet is BCA but the order CBA and BAC are also observed. The glgP and glgX genes are not always present near the glgA/B/C triplet, but if they are, their order is highly variable.179 The duplication of genes involved in glycogen metabolism was observed in several bacterial species, likely providing (i) functional redundancy, (ii) different kinetics, substrate specificities and/or expression profiles, and (iii) functional promiscuity/specialization of genes as a source of diversity and evolution of the metabolic pathways.180,181 Interestingly, certain bacterial species display additional functions clustered in the glg operon, as the amy (α-amylase) and pgm/phx (phosphoglucomutase) genes.182

3.1.1. Biosynthesis

Glucose 1-phosphate plays a central role in the metabolism of glycogen (Figure 3A).183 Glucose 1-phosphate is produced by the phosphoglucomutase (Pgm) from glucose 6-phosphate. In turn, glucose 6-phosphate is produced either by phosphorylation of extracellular glucose by the hexokinase, or from the final steps of gluconeogenesis by transforming fructose 6-phosphate by the phosphoglucoisomerase.38 The activation of glucose 1-phosphate is the first committed and rate-limiting step of the classic glycogen biosynthetic pathway, involving the formation of ADP-glucose mediated by AGPase. AGPase catalyzes a condensation reaction between ATP and glucose 1-phosphate releasing pyrophosphate (PPi) diphosphate and ADP-glucose, requiring Mg2+ for activity.61,184 AGPase displays a bi–bi mechanism with ATP binding first, followed by glucose 1-phosphate and by the ordered release of PPi and ADP-glucose.185 Importantly, AGPase displays positive and negative allosteric regulation.186−188 The second step is carried out by GS, which generates linear α(1→4)-linked glucose chains.61,189 It is well established that the initiation step of glycogen biosynthesis in yeast and mammals requires the action of the enzyme glycogenin (GN), which is considered the first acceptor of glucose units.190,191 GN catalyzes an autoglycosylation reaction, the transfer of a glucose residue from UDP-glucose to a tyrosine residue (Tyr195 in human GN1).192 Fully sequenced genomes of bacteria known to accumulate glycogen have failed to reveal the presence of GN homologs.193 It was found that GS from Agrobacterium tumefaciens can not only elongate α(1→4)-linked glucans but also generate the primer required for the elongation process by catalyzing its own glycosylation.194 The oligosaccharides formed by GS were composed of two to nine glucose residues and, in addition, this α-glucan was released from the enzyme.194 Thus, it was proposed that bacterial GSs use this de novo synthesis mechanism in the absence of available soluble α(1→4)-glucans to provide itself with an initial substrate. It is speculated that GS preferentially catalyzes an elongation reaction of (i) malto-oligosaccharide primers generated during the initiation step or (ii) glycogen, inducing an apparent inhibition of the initiation reaction.194 The third step catalyzed by the GBE enzyme produces α(1→6)-linked glucan branches in the polymer. Biochemical and structural data indicate that GBEs only act on long polymers to transfer chains no shorter than six units and preferring chains eight or more sugars in length.195

3.1.2. Degradation

The recovery of glucose 1-phosphate from the glycogen degradation pathway is carried out by GP.196 GP catalyzes the reversible phosphorolysis of α(1→4)-glucans to obtain glucose 1-phosphate,197 requiring pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) as a prosthetic group.198 GlgP acts directly on the glycogen polymer, while MalP most likely catabolize soluble malto-oligosaccharides. The majority of characterized polyglucan phosphorylases are unable to act on chains smaller than five glucose residues in length. GlgP is unable to bypass or hydrolyze the α(1→6) linkages and therefore stops two, three, or four residues from the first α(1→6) branch encountered to generate the so-called β-limit dextrin.199 Glucose 1-phosphate is subsequently converted to glucose 6-phosphate to enter into the glycolytic pathway providing energy to the cell. Due to the high degree of branching present in the glycogen molecule, a second type of enzyme is required to cleave the α(1→6)-glucosidic bonds that remain uncleaved by GP. Bacterial GDEs display only α(1→6)-glucosidase activity. GDE cleaves the α(1→6)-glucosidic linkage between these glucose residues and the linear α(1→4)-glucan chains of glycogen and relies on MalP and GP to process the remaining α(1→4)-bonds in this short-released chain.

3.1.3. Regulation

The main regulatory step in the bacterial glycogen biosynthetic pathway is carried out by AGPase.61 This markedly contrast with the metabolic regulation of glycogen biosynthesis and degradation mechanisms in eukaryotic cells.109 AGPase has the ability to sense the energy status of the cell controlling its enzymatic activity by the action of allosteric regulators.185,187 AGPase activators are metabolites that reflect signals of high carbon and energy content of a particular bacteria or tissue, whereas inhibitors of the enzyme indicate low metabolic energy levels.78,200 Based on the regulatory profiles to different allosteric effector AGPases were classified into nine different classes.200

Bacterial AGPases are encoded by a single gene, producing a native homotetrameric protein (α4) with a molecular mass of ca. 200 kDa.61,186,188 The paradigmatic bacterial AGPase from E. coli (EcAGPase), is positively regulated by glycolytic intermediates, including fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) as the main activator with pyruvate acting synergistically, and negatively regulated by AMP generated from the general metabolism.187,200,201 Covalent binding of pyridoxal resulted in permanent activation of EcAGPase, while the presence of FBP protected the enzyme from binding to the compound, allowing the identification of Lys39 as a key residue in the activation mechanism.202,203 The structural and mechanistic aspects of this exquisite allosteric regulation arise from the AGPase tetrameric architecture that will be discussed in Section 5.1.1.1. Interestingly, histidine phosphotransporter protein (HPr), a protein associated with the PTS system and subject to phosphorylation/phosphorolysis modification, interacts with E. coli GP (EcGP) regulating its oligomeric status and enzymatic activity.204,205 Therefore, this second point of regulation in the classical pathway prevents glycogen synthesis from acting like a futile cycle, tightly controlling the state of the pathway.

Finally, the glycogen metabolism regulation in E. coli also involves a complex assemblage of factors that are adjusted to the physiological and energetic status of the cell.91 At the level of gene expression, several factors have been described to control bacterial glycogen accumulation, including (i) the PhoP–PhoQ regulatory system,206 (ii) the carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS),207 (iii) the carbon storage regulator CsrA,208,209 and (iv) and the cAMP-CRP responsive inner-membrane nucleoside transporters.210

3.2. The GlgE Pathway in Bacteria

The GlgC-GlgA pathway has been thought to be the only route for synthesizing intracellular glycogen-like α-glucan consisting of α(1→4)-linked glucosyl units with α(1→6)-branches in bacteria. However, in 2010, the presence of an alternative route that is not relying on a nucleoside diphosphate-activated donor substrate was discovered for glycogen-like α-glucan biosynthesis in mycobacteria, the GlgE pathway.211,212 Subsequently, it was found that the GlgE pathway is almost as frequently distributed among bacteria as the GlgC-GlgA pathway, being present in 14% of sequenced bacterial and archaeal genomes, whereas the GlgC-GlgA pathway is found in 20% of bacterial genomes.213 The GlgE pathway is very intimately connected and interrelated both in terms of biosynthesis and degradation with trehalose metabolism, as trehalose is a precursor for the formation of the activated donor substrate for GlgE, maltose 1-phosphate, and the glycogen-like α-glucan produced by the GlgE pathway can readily be mobilized to yield trehalose (Figure 3B).

3.2.1. Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of α-glucans via the GlgE pathway has first and best been studied in actinomycetes and particularly in mycobacteria (Figure 3B). In the GlgE pathway, α(1→6)-branched α(1→4)-glucans are produced by iterative cooperation of two essential enzymes, the maltosyltransferase GlgE (systematic name (1→4)-α-d-glucan:phosphate α-d-maltosyltransferase) and the branching enzyme GlgB.84,212 Both enzymes are GH13 family members.226 The maltosyltransferase GlgE uses maltose 1-phosphate as the activated donor substrate to produce linear α(1→4)-linked maltooligosaccharides.212 As soon as GlgE has formed a linear chain of ∼16 glucosyl residues, GlgB introduces an α(1→6)-branch of ∼7–8 glucosyl residues in length employing a strictly intrachain transfer mechanism. GlgE then preferentially extends the newly formed branch until it is long enough to undergo branching again by GlgB. Only occasionally, GlgE also extends previous branches so that they might become long enough to allow a second branching by GlgB. Therefore, each branched chain mostly carries just one further branch. These specificities of GlgE and GlgB promote an iterative process that results in a glucan polymer that exhibits a significantly lower degree of branching, resulting in a less pronounced arboreal structure compared to glycogen from other bacteria and from mammals.84 The branching enzyme GlgB from bacteria employing the GlgE pathway does not substantially differ from that of bacteria using the classical GlgC-GlgA pathway for glycogen formation,214,215 indicating that the evolution of the maltosyltransferase GlgE was key for the establishment of the GlgE pathway. Consistent with the strictly iterative process of synthesis of a glycogen-like polysaccharide via the GlgE pathway, the genes encoding GlgE and GlgB are co-transcribed as part of an operon in mycobacteria and all other bacteria possessing the GlgE pathway.213 However, while protein structures of GlgE216−221 and GlgB215 have individually been resolved from different organisms possessing the GlgE pathway, it is unknown whether direct physical interaction between both proteins occurs to mediate the iterative synthesis of α(1→6)-branched α(1→4)-glucans. GlgE from actinomycetes has been shown to form a homodimer and to catalyze the α-retaining transfer of maltosyl units from α-maltose 1-phosphate to maltooligosaccharides using a double-displacement mechanism, i.e., a ping-pong mechanism involving the release of the glucan extended by a maltosyl unit prior to the next reaction.212,221In vitro experiments using only purified GlgE and GlgB proteins recombinantly expressed from M. tuberculosis as well as maltose 1-phosphate as the donor substrate resulted in the formation of high-molecular-weight α(1→6)-branched α(1→4)-glucan particles resembling in chemical structure and supramolecular architecture those natively isolated from cells of M. tuberculosis and Streptomyces venezuelae,84 indicating that GlgE can initiate de novo α-glucan synthesis without the need of a primer, similar to the priming function of GlgA activity in the GlgC-GlgA pathway.194 In absence of maltose 1-phosphate substrate and presence of maltooligosaccharides, GlgE can also mediate disproportionation by transfer of maltosyl units from the non-reducing end of a donor molecule to the non-reducing end of an acceptor maltooligosaccharide.212 In addition to GlgE from actinomycetes, the maltosyltransferase has also biochemically been studied in great detail in recombinantly expressed form from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1173 (Figure 3C) and Estrella lausannensis(222) revealing very similar enzymatic characteristics of the GlgE proteins of different origin.

3.2.2. Formation of the Maltose 1-Phosphate Donor Substrate

In contrast to glucosyltransferases such as the glycogen synthase GlgA that uses nucleoside diphosphate-coupled glucosyl units such as UDP-glucose or ADP-glucose as activated donor substrate, GlgE employs maltose 1-phosphate as activated donor substrate. Two alternative routes for biosynthesis of maltose 1-phosphate have been described, the GlgC-GlgM and the TreS-Pep2 (named TreS-Mak in some organisms) pathways. In actinomycetes such as M. tuberculosis, both pathways operate simultaneously, while other bacteria possessing the GlgE pathway only employ the TreS-Pep2 / TreS-Mak route (Figure 3B,C).

Both routes are closely connected to trehalose metabolism. Trehalose is an α,α(1→1)-linked glucose dimer that is abundant in many pro- and eukaryotic organisms. Trehalose is not representing an α-glucan sensu stricto and plays a broad variety of biological functions dependent on the producing organism, most of them being unrelated to α-glucan metabolism as has already extensively been reviewed.223 However, due to its important connection to the GlgE pathway, trehalose biosynthesis pathways will briefly be described here. Bacteria possessing the GlgE pathway for α-glucan production employ one or both of two alternative routes for de novo synthesis of trehalose. The most widespread route in prokaryotes is the OtsA-OtsB pathway. The trehalose 6-phosphate synthase OtsA (a Leloir-type glycosyltransferase) catalyzes the transfer of nucleoside diphosphate-activated glucose to glucose 6-phosphate to yield trehalose 6-phosphate with release of nucleoside diphosphate. In most cases, OtsA uses UDP-glucose. However, OtsA of M. tuberculosis (Rv3490) has been demonstrated to exhibit a 10-fold higher affinity for ADP-glucose than for UDP-glucose.224 The trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase OtsB then catalyzes the dephosphorylation of trehalose 6-phosphate to release free trehalose and inorganic phosphate. The M. tuberculosis genome encodes two genes with homology to bacterial trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatases, otsB1 (Rv2006) and otsB2 (Rv3372). The encoded OtsB1 protein is much larger than OtsB2 (1327 aa vs. 391 aa, respectively). However, only the essential OtsB2 expresses trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase activity and is relevant for trehalose biosynthesis225 while a ΔotsB1 mutant of M. tuberculosis showed no obvious phenotype so that the function of OtsB1 is yet unknown.226 In the alternative route, the TreY-TreZ pathway, the maltooligosyltrehalose synthase TreY converts the terminal α(1→4)-glycosidic linkage at the reducing end of a linear α(1→4)-glucan into an α-1,1-bond yielding maltooligosyltrehalose. Maltooligosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase TreZ then hydrolytically liberates trehalose. As this pathway requires linear glucans, branched α-glucans first need to be processed by glycogen phosphorylase GlgP, which reduces the branch length by releasing glucose 1-phosphate, followed by debranching enzyme TreX, which hydrolyzes the α(1→6)-glycosidic branch linkages. TreX, TreY, and TreZ all belong to the GH13 protein family227 (Figure 3).

In the most common route for maltose 1-phosphate biosynthesis, the TreS-Pep2/TreS-Mak pathway, the trehalose synthase TreS mediates the conversion of trehalose to maltose by converting the α(1→1)-bond into an α(1→4)-glycosidic bond. Subsequently, maltose is rapidly and quantitatively phosphorylated in an ATP-dependent reaction to maltose 1-phosphate by the maltose kinase (systematic name ATP:α-maltose 1-phosphotransferase), which is named Pep2 or Mak depending on the organism.228,229 Previously, TreS was thought to exclusively mediate trehalose formation from maltose. However, although the equilibrium of purified TreS favors the formation of trehalose from maltose in vitro, flux through TreS in vivo is in the opposite direction whenever a maltose kinase is expressed,230 driven by the rapid and irreversible ATP-dependent phosphorylation of the formed maltose to maltose 1-phosphate by the maltose kinase.216,229 The observed finding of the direction of flux through TreS for consumption of trehalose is supported by the fact that TreS and Pep2/Mak are expressed as a fusion protein in many organisms with the exception of actinobacteria (i.e., mycobacteria and Streptomycetes).213 Recombinant bifunctional TreS-Mak from Estrella lausannensis has been enzymatically characterized and was found to exhibit an apparent molecular weight of 256 kDa. The TreS-Mak fusion protein produced maltose 1-phosphate in the presence of nucleoside triphosphates and trehalose concentration resembling physiological intracellular conditions.222 Likewise, the TreS-Pep2 fusion protein from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 has been reported to exhibit similar enzymatic properties and to synthesize maltose 1-phosphate from trehalose and ATP, although the supramolecular architecture has not been studied.173 In contrast, TreS and Pep2 are expressed as individual proteins in actinobacteria. Here, they form a hetero-octameric complex composed of four subunits of TreS and four subunits of Pep2 with an apparent molecular weight of ca. 490 kDa, in which a homotetramer of TreS forms a platform to recruit dimers of Pep2 via a specific interaction domain as observed in Mycolicibacterium smegmatis.231,232

More recently, a second route for formation of maltose 1-phosphate was discovered in M. tuberculosis, the GlgC-GlgM pathway119 (Figure 3B). While M. tuberculosis GlgM (Rv1212c) was previously believed to be a glycogen synthase and named GlgA accordingly, it was shown that GlgM is a maltose 1-phosphate-producing glucosyltransferase (formal name ADP-α-d-glucose:α-d-glucose-1-phosphate 4-α-d-glucosyltransferase) three orders of magnitude more efficient at transferring glucose from ADP-glucose to glucose 1-phosphate than to glycogen.119 Recently, GlgM from the related bacterium M. smegmatis has been crystallized, and enzymatically characterized revealing very similar properties to the enzyme from M. tuberculosis.233 GlgM from mycobacteria is a GT4 family enzyme employing an α-retaining mechanism, while bona fide bacterial glycogen synthases are GT5 family members. Bioinformatic analysis of bacterial genomes revealed that ∼32% of all annotated GlgA homologues exhibit GT4 membership. It is striking that in every case where GlgA and GlgE coexist in Gram-positive bacteria (typically actinomycetes including mycobacteria and streptomycetes), the GlgA belongs exclusively to the GT4 family and never to the GT5 family. This coexistence strongly suggests that all these GlgA homologues actually have no glycogen synthase activity but rather represent maltose 1-phosphate-producing ADP-α-d-glucose:α-d-glucose 1-phosphate 4-α-d-glucosyltransferases and should be named GlgM accordingly.119 This finding also implies that the proportion of microbes that possess the classical GlgC-GlgA glycogen pathway is only ∼20% and thus lower than previously estimated.213 GlgM prefers ADP-glucose as the donor substrate and can use UDP-glucose at ca. 10-fold lower efficiency. Thus, GlgM is essentially linked to GlgC for the production of ADP-glucose. Similarly, the affinity of trehalose 6-phopshate synthase OtsA from M. tuberculosis for ADP-glucose was found to be one order of magnitude higher than for UDP-glucose.224 Mutational studies in M. smegmatis revealed that GlgM and OtsA are the main consumers of ADP-glucose in this organism as revealed by substantial intracellular ADP-accumulation in the M. smegmatis ΔglgA(u) ΔotsA double mutant. Furthermore, it was found that there is a redirection of the flux of ADP-glucose since neither the M. smegmatis ΔglgA nor the ΔotsA single mutants accumulated detectable amounts of ADP-glucose. When GlgM is inactivated, ADP-glucose is redirected through OtsA promoting trehalose formation, whereas the increased trehalose level in turn stimulates maltose 1-phosphate synthesis via TreS-Pep2.119 Thus, the TreS-Pep2 and GlgC-GlgM pathways for maltose 1-phosphate synthesis are linked via the shared use of the intermediate ADP-glucose by GlgM and OtsA. The flux of ADP-glucose seems to be sufficiently redirected such that the net rate of maltose 1-phosphate generation and α-glucan accumulation can be balanced to some extent when one of the two routes is perturbed.119

3.2.3. Degradation