Abstract

Background

The review represents one in a family of four reviews focusing on a range of different interventions for drug‐using offenders. This specific review considers pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing drug use or criminal activity, or both, for illicit drug‐using offenders.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders in reducing criminal activity or drug use, or both.

Search methods

We searched Fourteen electronic bibliographic databases up to May 2014 and five additional Web resources (between 2004 and November 2011). We contacted experts in the field for further information.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials assessing the efficacy of any pharmacological intervention a component of which is designed to reduce, eliminate or prevent relapse of drug use or criminal activity, or both, in drug‐using offenders. We also report data on the cost and cost‐effectiveness of interventions.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as expected by Cochrane.

Main results

Fourteen trials with 2647 participants met the inclusion criteria. The interventions included in this review report on agonistic pharmacological interventions (buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone) compared to no intervention, other non‐pharmacological treatments (e.g. counselling) and other pharmacological drugs. The methodological trial quality was poorly described, and most studies were rated as 'unclear' by the reviewers. The biggest threats to risk of bias were generated through blinding (performance and detection bias) and incomplete outcome data (attrition bias). Studies could not be combined all together because the comparisons were too different. Only subgroup analysis for type of pharmacological treatment were done. When compared to non‐pharmacological, we found low quality evidence that agonist treatments are not effective in reducing drug use or criminal activity, objective results (biological) (two studies, 237 participants (RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.00); subjective (self‐report), (three studies, 317 participants (RR 0.61 95% CI 0.31 to 1.18); self‐report drug use (three studies, 510 participants (SMD: ‐0.62 (95% CI ‐0.85 to ‐0.39). We found low quality of evidence that antagonist treatment was not effective in reducing drug use (one study, 63 participants (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.70) but we found moderate quality of evidence that they significantly reduced criminal activity (two studies, 114 participants, (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.74).

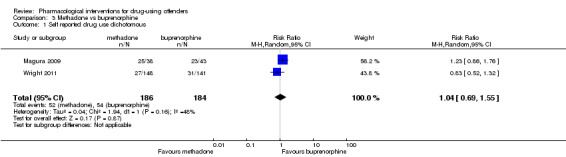

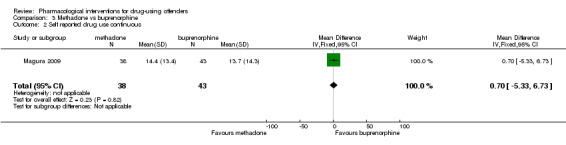

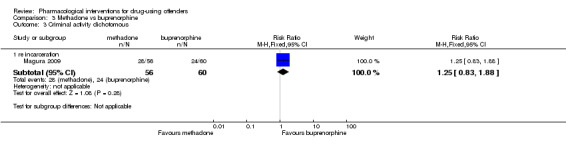

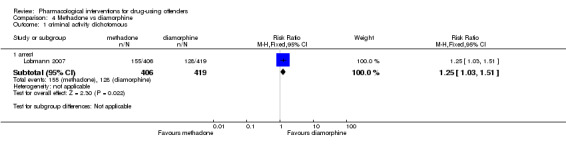

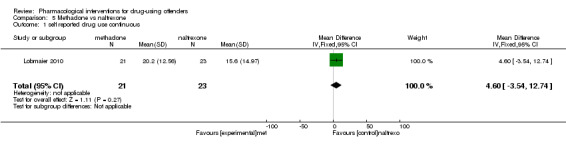

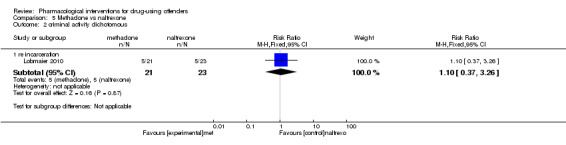

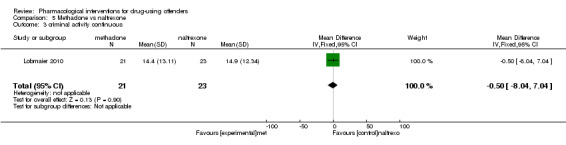

Findings on the effects of individual pharmacological interventions on drug use and criminal activity showed mixed results. In the comparison of methadone to buprenorphine, diamorphine and naltrexone, no significant differences were displayed for either treatment for self report dichotomous drug use (two studies, 370 participants (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.55), continuous measures of drug use (one study, 81 participants, (mean difference (MD) 0.70, 95% CI ‐5.33 to 6.73); or criminal activity (one study, 116 participants, (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.88) between methadone and buprenorphine. Similar results were found for comparisons with diamorphine with no significant differences between the drugs for self report dichotomous drug use for arrest (one study, 825 participants, (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.51) or naltrexone for dichotomous measures of reincarceration (one study, 44 participants, (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.37 to 3.26), and continuous outcome measure of crime, (MD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐8.04 to 7.04) or self report drug use (MD 4.60, 95% CI ‐3.54 to 12.74).

Authors' conclusions

When compared to non‐pharmacological treatment, agonist treatments did not seem effective in reducing drug use or criminal activity. Antagonist treatments were not effective in reducing drug use but significantly reduced criminal activity. When comparing the drugs to one another we found no significant differences between the drug comparisons (methadone versus buprenorphine, diamorphine and naltrexone) on any of the outcome measures. Caution should be taken when interpreting these findings, as the conclusions are based on a small number of trials, and generalisation of these study findings should be limited mainly to male adult offenders. Additionally, many studies were rated at high risk of bias.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Criminals, Buprenorphine, Buprenorphine/therapeutic use, Crime, Crime/prevention & control, Heroin, Heroin/therapeutic use, Methadone, Methadone/therapeutic use, Naltrexone, Naltrexone/analogs & derivatives, Naltrexone/therapeutic use, Narcotics, Narcotics/therapeutic use, Opiate Substitution Treatment, Opiate Substitution Treatment/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Substance‐Related Disorders, Substance‐Related Disorders/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders

Background

Drug‐using offenders by their nature represent a socially excluded group in which drug use is more prevalent than in the rest of the population. Pharmacological interventions play an important role in the rehabilitation of drug‐using offenders. For this reason, it is important to investigate what we know works when pharmacological interventions are provided for offenders.

Study characteristics

The review authors searched scientific databases and Internet resources to identify randomised controlled trials (where participants are allocated at random to one of two or more treatment groups) of interventions to reduce, eliminate, or prevent relapse of drug use or criminal activity of drug‐using offenders. We included males and female of any age or ethnicity.

Key results

We identified 14 trials of pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders. The interventions included: (1) naltrexone in comparison with routine parole, social psychological treatment or both; (2) methadone maintenance in comparison with different counselling options; and (3) naltrexone, diamorphine and buprenorphine in comparison with a non‐pharmacological alternative and in combination with another pharmacological treatment. Studies could not be combined all together because the comparisons were too different. When compared to non‐pharmacological, we found low quality evidence that agonist treatments are not effective in reducing drug use or criminal activity . We found low quality of evidence that antagonist treatment was not effective in reducing drug use but we found moderate quality of evidence that they significantly reduced criminal activity. When comparing the drugs to one another we found no significant differences between the drug comparisons (methadone versus buprenorphine, diamorphine and naltrexone) on any of the outcome measures suggesting that one pharmacological drug does not preside over another. One study provided some cost comparisons between buprenorphine and methadone, but data were not sufficient to generate a cost‐effectiveness analysis. In conclusion, we found that pharmacological interventions do reduce subsequent drug use and criminal activity (to a lesser extent). Additionally, we found individual differences and variation between the degree to which successful interventions were implemented and were able to sustain reduction of drug use and criminal activity.

Quality of evidence

This review was limited by the lack of information reported in this group of trials and the quality of the evidence was low. The evidence is current to May 2014.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings for the main comparisons: Agonist pharmacological compared to no intervention for drug‐using offenders.

| Agonist pharmacological compared to no intervention for drug‐using offenders | ||||||

| Patient or population: drug‐using offenders Settings: criminal justice Intervention: Agonist pharmacological Comparison: no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No intervention | Agonist pharmacological | |||||

| Drug use (objective) hair and urine analyses Follow‐up: 3 months to 4 years | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.51 to 1) | 237 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 43 per 100 | 31 per 100 (22 to 43) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 36 per 100 (25 to 50) | |||||

| Drug use self reported dichotomous self report information Follow‐up: 3 months to 4 years | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.31 to 1.18) | 317 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 74 per 100 | 45 per 100 (23 to 88) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 74 per 100 | 45 per 100 (23 to 88) | |||||

| Drug use self reported continuous self report information Follow‐up: 9 months to 4 years | The mean drug use self reported continuous in the intervention groups was 0.62 standard deviations lower (0.85 to 0.39 lower) | 510 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6 | SMD ‐0.62 (‐0.85 to ‐0.39) | ||

| Criminal activity dichotomous ‐ Arrests official records Follow‐up: median 9 months | Study population | RR 0.6 (0.32 to 1.14) | 62 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7, 10 | ||

| 55 per 100 | 33 per 100 (18 to 63) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 55 per 100 | 33 per 100 (18 to 63) | |||||

| Criminal activity dichotomous ‐ Re‐incarceration official records Follow‐up: 7 months to 4 years | Study population | RR 0.77 (0.36 to 1.64) | 472 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low8,9 | ||

| 66 per 100 | 51 per 100 (24 to 100) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 83 per 100 | 64 per 100 (30 to 100) | |||||

| Criminal activity continuous mean number of crime dayes Follow‐up: median 9 months | The mean criminal activity continuous in the intervention groups was 74.21 lower (133.53 to 14.89 lower) | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7, 11 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Across the two studies 10 of the 18 risk of bias items in total were rated as unclear. 2 The total number of events across the two studies is less than 300. This is a threshold rule of thumb based on Muller et al Ann Intern Med. 2007; 146: 878‐881. 3 Across the three studies 17 items were rated as unclear out of a total of 27 items. 4 The P value for heterogenity is less than 0.05 and the I2 is 89% suggesting significant inconsistency between the studies. 5 Across the three studies 16 of the 27 items on risk of bias were rated as unclear 6 The P value for heterogenity is less than 0.05 and the I2 is 99% suggesting significant inconsistency across the studies. 7 6 of the 9 risk of bias items were rated as unclear 8 Across the three studies 17 of the 27 risk of bias items in total were rated as unclear 9 The P value for heterogenity is less than 0.05 and the I2 is 74% suggesting significant heterogenity.

10 only 1 study with 62 participants

11 only 1 study with 51 participants

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings for the main comparisons: Antagonost (Naltrexone) compared to no pharmacological for drug‐using offenders.

| Antagonost(Naltrexone) compared to no pharmacological for drug‐using offenders | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with drug‐using offenders Settings: criminal justice Intervention: Antagonost(Naltrexone) Comparison: no pharmacological | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No pharmacological | Antagonost(Naltrexone) | |||||

| Criminal activity dichotomous ‐ Reincarceration official records Follow‐up: 6 months | Study population | RR 0.4 (0.21 to 0.74) | 114 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 39 per 100 | 16 per 100 (8 to 29) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 44 per 100 | 17 per 100 (9 to 32) | |||||

| drug use (objective) urine screen Follow‐up: 30 days prior to 6 months | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.28 to 1.7) | 63 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 28 per 100 | 19 per 100 (8 to 48) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 28 per 100 | 19 per 100 (8 to 48) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Across the two studies 9 of the 18 risk of bias items were rated as unclear 2 5 of the 9 risk of bias items was rated as unclear

3 only 1 study with 63 participants

Background

This review represents part of a family of four reviews undertaken to closely examine what works in reducing drug use and criminal activity among drug‐using offenders. Overall, the four reviews contain over 100 trials, generating a number of publications and numerous comparisons (Perry 2013a; Perry 2013b; Perry 2013c). The four reviews represent specific interests in pharmacological interventions, non‐pharmacological interventions, female offenders and offenders with co‐occurring mental illness. All four reviews stem from an updated previous Cochrane systematic review (Perry 2006). In this set of four reviews, we consider the effectiveness of interventions based on two key outcomes and analyse the impact of setting and intervention type. Presented here is the revised methodology for this individual review, focusing on the impact of pharmacological interventions provided for drug‐using offenders.

Description of the condition

Offenders as a socially excluded group of people demonstrate significant drug use and subsequent health problems. Studies investigating the prevalence of drug dependence in UK prisons report variable results of 10% (Gunn 1991), 39% (Brooke 1996), and 33% (Mason 1997). Similar trends have been reported elsewhere. In France, 30% of prison inmates are heroin addicted, and in Australia, 59% of prison inmates report injecting (primarily heroin) drug use histories. In the US, it is recognised that many offenders are in need of treatment to tackle their drug use (Lo 2000).The link between drug use, subsequent health and social and criminological consequences is well documented in the literature (e.g. Michel 2005), and offenders have a high risk of death from opioid overdose within two weeks of release from incarceration (Bird 2003; Binswanger 2007). Substance use disorders are linked to criminal behaviour and are a significant burden on the criminal justice system. Approximately 30% of acquisitive crime is committed by individuals supporting drug use with the use of criminal acts (Magura 1995).

Description of the intervention

Internationally, methadone maintenance has been the primary choice for chronic opioid dependence in prisons and jails, including those in the Netherlands, Australia, Spain and Canada, and it is being increasingly implemented in the criminal justice setting (Moller 2007; Stallwitz 2007). The US has not generally endorsed the use of methadone treatment, and only 12% of correctional settings offer this option for incarcerated inmates (Fiscella 2004). Reasons for this lack of expansion suggest that public opinion and that of criminal justice system providers consider methadone treatment as substituting one addiction for another. In contrast, buprenorphine appears not to carry the same social stigma associated with methadone treatment and has been used in France, Austria and Puerto Rico (Catania 2003; Reynaud‐Maurupt 2005; Garcia 2007). Naltrexone treatment has shown some promising findings, but associated problems surrounding high attrition and low medication compliance in the community and high mortality rates (e.g. Gibson 2007; Minozzi 2011) pose concerns. Trials conducted in the criminal justice setting are still lacking, and continuity of care is considered crucial in the treatment of drug‐involved offenders who transition between prison and the community.

How the intervention might work

A growing body of evidence shows the effects of pharmacological interventions for drug use among the general population. Existing reviews have focused on naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence (Amato 2005; Lobmaier 2008; Minozzi 2011); and the efficacy of methadone (Marsch 1998; Faggiano 2003; Mattick 2009); and buprenorphine maintenance (Mattick 2009). Recent guidance has been provided from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence on evidence‐based use of naltrexone, methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence (NICE 2007a; NICE 2007b). Five Cochrane reviews (including 52 studies) reported on the effectiveness of opiate methadone therapies (Amato 2005). Findings showed that methadone maintenance therapies at appropriate doses were most effective in retaining participants in treatment and in suppressing heroin use, but evidence of effectiveness for other relevant outcome measures such as criminal activity was weak and was not systematically evaluated.

Systematic reviews evaluating treatment programs more generally for offender populations have focused on evaluating treatment in one setting such as community‐based programmes, (e.g. Mitchell, 2012a; Mitchell, 2012b); or have based their evidence on literature from one country (e.g. Germany or the US) (Chanhatasilpa 2000; Egg 2000); or a number of specific treatments (Mitchell 2006). Pharmacological systematic reviews of offender treatment appear to be sparse. We identified two previous reviews, one focusing on specific drug‐ and property‐related criminal behaviours in methadone maintenance treatment (Marsch 1998); and an evaluation of the effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment (OMT) in prison and post‐release (Hedrich 2011). The later of these two reviews identified six experimental studies up until January 2011 (Hedrich 2011). The authors found that OMT in prison was significantly associated with reduced heroin use, injecting and syringe sharing. Use of pre‐release OMT was also found to have important implications for associated treatment uptake after release, but the impact on criminal activity was equivocal.

Why it is important to do this review

The current review provides a systematic examination of trial evidence relating to the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders. We believe it is important to conduct this review because the evidence about pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders has not been evaluated in this manner before. In order to address this broad topic a series of questions will consider the effectiveness of different interventions in relation to criminal activity, drug misuse treatment setting and type of treatment. The review will additionally report descriptively on the costs and cost effectiveness of such treatment programs.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders in reducing criminal activity or drug misuse or both. The review addressed the following questions:

Does any pharmacological treatment for drug‐using offenders reduce drug use?

Does any pharmacological treatment for drug‐using offenders reduce criminal activity?

Does the treatment setting (e.g. court, community, prison/secure establishment) affect outcome(s) of pharmacological treatments?

Does one type of pharmacological treatment perform better than one other?

Additionally, this review aimed to report on the cost and cost‐effectiveness of interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Types of participants

We included illicit drug‐misusing offenders in the review regardless of gender, age, ethnicity or psychiatric illness. Drug misuse includes individuals occasionally using drugs, or who are dependent on, or are known to abuse, drugs. Offenders are defined as individuals who were subject to the criminal justice system.

Types of interventions

Included interventions were designed, wholly or in part, to eliminate or prevent relapse to drug use or criminal activity, or both, among participants. We defined relapse as individuals who may have returned to an incarcerated setting, or had subsequently been arrested or had relapsed back into drug misuse, or both. We included a range of different types of interventions in the review.

Experimental interventions included in the review:

Any pharmacological intervention (e.g. buprenorphine, methadone)

Control interventions included in the review.

No treatment

Minimal treatment

Waiting list

Treatment as usual

Other treatment (e.g. pharmacological or psychosocial)

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

For the purpose of our review we categorised our primary outcomes into those relating to dichotomous and continuous drug use or criminal activity, or both. Where papers reported a number of different follow‐up periods, we report the longest time period, as we felt that such measures provide the most conservative estimate of effectiveness. For specific meta‐analyses of sub‐groupings, we reviewed all reported follow‐up periods to select the most appropriate time period for combining comparable studies.

Drug use measures were reported as:

self‐report drug use (unspecified drug, specific drug use not including alcohol/tobacco, Addiction Severity Index drug composite scores); and

biological drug use (measured by drugs tested by urine or hair analysis).

Criminal activity as measured by:

self‐report or official report of criminal activity (including arrest for any offence, drug offences, reincarceration, convictions, charges and recidivism).

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcome reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness information. We used a descriptive narrative for these findings. We undertook a full critical appraisal based on the Drummond 1997 checklist for those studies presenting sufficient information.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Electronic searches

The update searches identified records from 2004 to May 2014.

CENTRAL (Issue 5, 2014).

MEDLINE (1966 to May 2014).

EMBASE (1980 to May 2014).

PsycINFO (1978 to April 2014).

Pascal (1973 to November 2004)a.

SciSearch (Science Citation Index) (1974 to April 2014).

Social SciSearch (Social Science Citation Index) (1972 to April 2014).

ASSIA (1987 to May 2014).

Wilson Applied Science and Technology Abstracts (1983 to October 2004)a.

Inside Conferences (1993 to November 2004)a.

Dissertation Abstracts (1961 to October 2004)a.

NTIS (1964 to April 2014).

Sociological Abstracts (1963 to April 2014).

HMIC (to April 2014).

PAIS (1972 to April 2014).

SIGLE (1980 to June 2004)b.

Criminal Justice Abstracts (1968 to April 2014).

LILACS (2004 to April 2014).

National Research Register (March 2004)c.

Current Controlled Trials (December 2009).

Drugscope (February 2004)-unable to access.

SPECTR (March 2004)d.

aUnable to access further to 2004 search. bDatabase not updated since original 2004 search. cNo longer exists. dNow Campbell Collaboration searched on line.

To update the original review (Perry 2006), the search strategy was restricted to studies that were published or unpublished from 2004 onwards. A number of original databases were not searched for this update (indicated by the key at the end of the database list). Pascal, ASSIA, Wilson Applied Science and Technology Abstracts, Inside Conferences and Dissertation Abstracts were not searched. These databases are available only via the fee‐charging DIALOG online host service: we did not have the resources to undertake these searches. The National Research Register no longer exists, and SIGLE has not been updated since 2005. Drugscope is available only to subscribing members. The original searches were undertaken by Drugscope staff.

Search strategies were developed for each database to exploit the search engine most effectively and to make use of any controlled vocabulary. Search strategies were designed to restrict the results to RCTs. No language restriction was placed on the search results. We included methodological search filters designed to identify trials. Whenever possible, filters retrieved from the InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub‐Group (ISSG) Search Filter Resource site (http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/intertasc/) were used. If filters were unavailable from this site, search terms based on existing filters were used instead.

In addition to the electronic databases, a range of relevant Internet sites (Home Office, National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) and European Association of Libraries and Information Services on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ELISAD)) were searched. Directory web sites, including OMNI (http://www.omni.ac.uk), were searched up until November 2011. The review did not place any language restrictions on identification and inclusion of studies in the review.

Details of the update search strategies and results and of the Internet sites searched are listed in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12; Appendix 13.

Searching other resources

Reference checking

We scrutinised the reference lists of all retrieved articles for further references, and also undertook searches of the catalogues of relevant organisations and research founders.

Personal communication

We contacted experts for their knowledge of other studies, published or unpublished, relevant to the review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently inspected the search hits by reading the titles and abstracts, and obtained each potentially relevant study located in the search as a full‐text article to independently assess them for inclusion. In the case of discordance, a third independent author arbitrated. One author undertook translation of articles not written in the English language.

The screening process was divided into two key phases. Phase one used the initial seven key questions reported in the original new reference review. These were:

Prescreening criteria: phase one

Is the document an empirical study? [If "no" exclude document.]

Does the study evaluate an intervention, a component of which is designed to reduce, eliminate or prevent relapse among drug‐using offenders?

Are the participants referred by the criminal justice system at baseline?

Does the study report pre‐programme and post‐programme measures of drug use?

Does the study report pre‐programme and post‐programme measures of criminal behaviour?

Is the study a randomised controlled trial?

Do the outcome measures refer to the same length of follow‐up for two groups?

After relevant papers from phase one had been identified, phase two screening was performed to identify papers reporting on pharmacological interventions. Criteria included the following.

Prescreening: phase two

Is the intervention a pharmacological intervention? [if "yes" include document]

Drug‐using interventions were implied if the programme targeted reduced drug use in a group of individuals. Offenders were individuals either residing in special hospitals, prisons, the community (i.e. under the care of the probation service) or diverted from court or placed on arrest referral schemes for treatment. We included studies in the review where the sample were not entirely drug‐using, but reported pre‐ and post‐measures. The study setting could change throughout the process of the study, e.g. offenders could begin in prison but progress through a work‐release project into a community setting. Finally, studies did not need to report both drug and criminal activity outcomes: if either of these was reported we included the study in the review.

Data extraction and management

We used data extraction forms to standardise the reporting of data from all studies obtained as potentially relevant. Two authors independently extracted data and subsequently checked them for agreement.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Five independent review authors (AEP, JMG, MM‐SJ, MN, RW) assessed risk of bias in all included studies using risk of bias assessment criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

The risk of bias assessment for RCTs in this review was performed using the criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in a Cochrane Review involves the use of a two‐part tool that addresses six specific domains, namely, sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other sources of bias. The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement related to the risk of bias for that entry in terms of low, high or unclear risk. To make these judgements, we used the criteria indicated by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as adapted for the addiction field.

The domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) were addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessor (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias) was considered separately for objective outcomes (e.g. dropping out, using substance of abuse as measured by urinalysis, relapsing of participants at the end of follow‐up, engaging of participants in further treatments) and subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, participant self‐reported use of substance, side effects, social functioning as integration at school or at work, family relationships).

Incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) were considered for all outcomes except dropping out of treatment, which very often is the primary outcome measure in trials on addiction. See Appendix 14 for details.

For studies identified in the most recent search, the review authors attempted to contact study authors to establish whether a study protocol was available.

Measures of treatment effect

The mean differences (MD) were used for outcomes measured on the same scale and the standardised mean difference (SMD) for outcomes measured on different scales. Higher scores for continuous measures are representative of greater harm. We present dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RR), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

To avoid double counting of outcome measures (e.g. arrest and parole violation) and follow up time periods (e.g. 12, 18 months) all trials were checked to ensure that multiple studies reporting the same evaluation did not contribute towards multiple estimates of programme effectiveness. We followed Cochrane guidance and where appropriate we combined intervention and control groups to create a single pairwise comparison. Where this was not appropriate we selected one treatment arm and excluded the others.

Dealing with missing data

Where we found data was missing in the original publication, we attempted to contact the study authors via email to obtain the missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogenity was assessed using I² and Q statistics (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

The RevMan software package was used to perform a series of meta‐analyses for continuous and dichotomous outcome measures (Review Manager 2014). A random‐effects model was used to account for the fact that participants did not come from a single underlying population. A narrative review were performed to address each of the key questions outlined in the objectives. The narrative tables included a presentation of study details (e.g. author, year of publication, and country of study origin), study methods (e.g. random assignment), participants (e.g. number in sample, age, gender, ethnicity, age, mental health status), interventions (e.g. description, duration, intensity, setting), outcomes (e.g. description, follow‐up period, reporting mechanism), resource and cost information and resource savings (e.g. number of staff, intervention delivery, estimated costs, estimated savings), and notes (e.g. methodological and quality assessment information). For outcomes of criminal activity, data were sufficient to allow the review authors to divide this activity into "re‐arrest" and reincarceration categories.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A separate subgroup analysis of the studies was planned by different types of treatments and different settings.

Sensitivity analysis

When appropriate, sensitivity analyses were planned to assess the impact of studies with high risk of bias. Because of the overall high risk of bias of the included studies, this analysis was not conducted.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Original review

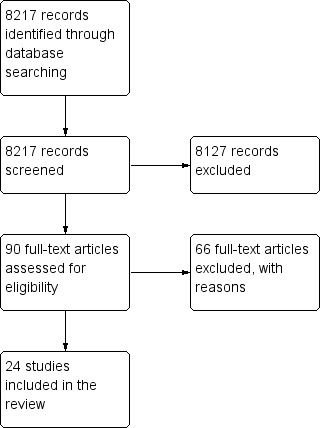

The original searches spanned from database inception to October 2004. This identified a total of 8217 records after duplication. We acquired a total of 90 full text papers for assessment and excluded 66 papers, bringing 24 trials to the review (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram of paper selection: Original Review

First update

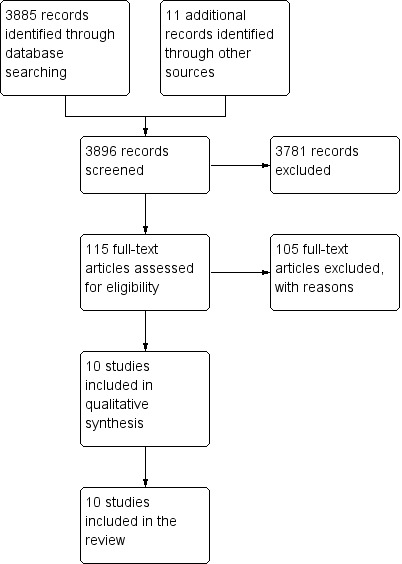

The updated searches spanned from October 2004 until March 2013. This identified a total of 3896 records after duplication. We acquired a total of 115 full text papers for assessment and excluded 105 papers, bringing 10 new trials to the review (see Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram of paper selection: First Update

Second update

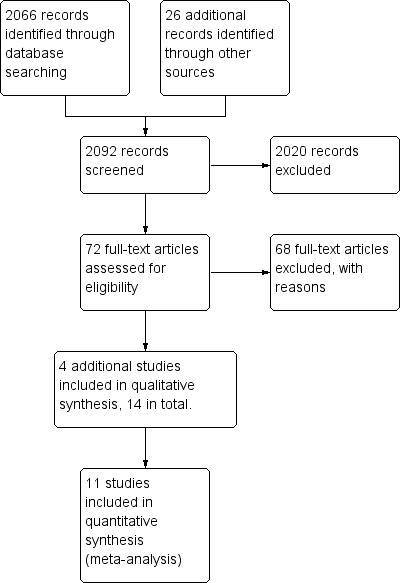

The updated searches spanned from March 2013 until May 2014. This identified a total of 2092 records after duplication. We acquired a total of 72 full text papers for assessment and excluded 68 papers, bringing four new trials to the review making a total of 14 trials (see Figure 3).

3.

Study flow diagram of paper selection: Second Update

Included studies

The studies were published between 1969 and 2014 and represented 14 trials, including 2647 participants. The 14 trials consisted of 18 trial publications on different interventions (Bayanzadeh 2004; Brown 2013; Cornish 1997; Cropsey 2011; Coviello 2010; Dolan 2003; Dole 1969; Howells 2002; Kinlock 2005; Kinlock 2007; Lobmaier 2010; Lobmann 2007; Magura 2009; Wright 2011). Two trials represented data from multiple follow‐up publications. The Dolan studies published data on the primary study and four year follow‐up data (Dolan 2003); and Kinlock and colleagues reported on outcome measures and a secondary analysis of the data in two subsequent publications (see Kinlock 2007). See Table 3 for a summary of study information and outcomes.

1. Table 1 summary of outcomes and comparisons.

| Study | Setting | Intervention | Comparison group | Follow‐up period | Outcome type | Outcome description |

| Bayanzadeh 2004 | Prison | Methadone treatment in combination with CBT and widely focused on coping and problem‐solving skills. | Non‐methadone drugs plus standard psychiatric services and therapeutic medications | 6 months | Biological drug use Self‐report drug use |

Drug use yes/no Frequency of drug injections (percentage) Syringe sharing Morphine urine analysis |

| Brown 2013 | Community | Methadone | Primary care plus suboxone (buprenorphine and naloxone) | 6 months 12 months |

Biological drug use Self report drug use |

Frequency and pattern of daily drug use Addiction Severity Index (self report). Lite, HIV risk behaviours (RAB ‐ Risk Assessment Battery short version), and health services utilization. Urine drug screens were collected as a part of routine management. |

| Cornish 1997 | Community | Naltrexone | Routine parole/probation | 6 months and during 6 months of treatment | Criminal activity dichotomous | % reincarcerated during 6 months of follow‐up |

| Coviello 2010 | Community | Naltrexone | Psychosocial treatment only | 6 months | Biological drug use dichotomous Criminal activity dichotomous |

% positive urine drug screen opioids % positive urine drug screen cocaine % violating parole/probation |

| Cropsey 2011 | Community | Buprenorphine | Placebo | End of treatment 3 months |

Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous |

% positive urine opiates % self‐report injection drug use |

| Dolan 2003 | Prison | Pharmacological (methadone) | Waiting list control | 4 months 2 months 3 months |

Biological drug use continuous Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous |

% hair positive for morphine % self‐reported any injection % self‐reported heroin injection |

| Dole 1969 | Prison | Methadone | Waiting list control. | At between 7 and 10 months At 50 weeks |

Biological drug use continuous Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous |

Heroin use Reincarceration Treatment retention Employment |

| Howells 2002 | Prison | Methadone and placebo | Lofexidine and placebo | Post treatment | Self report data on withdrawl Severity of psychological dependence |

Withdrawal symptom severity measured using two withdrawal scales: the 20‐item Withdrawal Problems Scale (WPS), and the eight item Short Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS). Secondary outcome measures were rates and timing of withdrawal from the detoxification programme so that the relationship between failure to complete detoxification and severity of withdrawal symptoms could be measured. The Severity of Dependency Scale (SDS) was also used to assess the severity of psychological aspects of drug dependence. |

|

Kinlock 2007 |

Prison | Counselling + methadone initiation pre‐release(a) and post‐release (b) | Counselling only | 1 month 3 months 6 months 12 months |

Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous Criminal activity dichotomous |

% positive for urine opioids % positive for urine cocaine % self‐reported 1 or more days heroin n used heroin for entire 180‐day follow‐up period Re‐incarcerated Self‐reported criminal activity |

| Kinlock 2005 | Prison | Prison based levo alpha acetyl methanol and transfer to methadone after release | untreated controls | During 9 months | Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous Criminal activity dichotomous |

Heroin use Arrest Re incarceration Frequency of illegal activity Admission drug use Average weekly income |

| Lobmaier 2010 | Prison | Naltrexone | Methadone | 6 months | Criminal activity continuous Criminal activity dichotomous Self‐report drug use continuous |

Mean days of criminal activity % re‐incarcerated Mean days of heroin use Mean days of benzodiazepine use Mean days of amphetamine use |

| Lobmann 2007 | Community | Pharmacological (diamorphine) | Methadone | 12 months | Criminal activity dichotomous | % self‐reported criminal activity % police‐recorded offences |

| Magura 2009 | Prison | Buprenorphine | Methadone | 3 months | Criminal activity dichotomous Self‐report drug use continuous Self‐report drug use dichotomous |

% re‐incarcerated % arrested for property crime % arrested for drug possession Mean days of heroin use % any heroin/opioid use |

| Wright 2011 | Prison | Buprenorphine | Methadone | 1 month 3 months 6 months post detoxification |

Biological drug test Self report official drug records |

Abstinence from illicit opiates at 8 days post detoxification, as indicated by a urine test. If the participant had been released, local community drugs service records were accessed to verify abstinence. |

A number of studies produced different comparisons and were combined appropriately according to time point of measurement (e.g. 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months) and type of outcome.

Treatment regimens and settings

Thirteen studies used methadone as the intervention or for comparison (Bayanzadeh 2004; Brown 2013; Dolan 2003; Dole 1969; Howells 2002; Kinlock 2005; Kinlock 2007; Lobmaier 2010; Lobmann 2007; Magura 2009; Wright 2011). Brown 2013 compared specialist treatment plus suboxone or methadone versus primary care plus suboxone; Lobmann 2007 compared methadone with diamorphine; and Magura 2009 and Wright 2011 compared methadone with buprenorphine. One study compared methadone to lofexidine (Howells 2002). All other studies compared methadone maintenance with interventions where there was no drugs administration (waiting list or counselling alone).

Three studies used naltrexone in oral and implantation formats in comparison with probation or parole (Cornish 1997); psychosocial therapy (Coviello 2010); and methadone (Lobmaier 2010).

One study compared the use of buprenorphine with a placebo (Cropsey 2011).

The studies were categorised by setting; five studies were conducted in the community (Cornish 1997; Lobmann 2007; Coviello 2010; Cropsey 2011; Brown 2013); and the remainder in secure settings (Dole 1969; Dolan 2003; Bayanzadeh 2004; Kinlock 2005; Kinlock 2007; Magura 2009; Lobmaier 2010; Howells 2002; Wright 2011).

One study was conducted using a jail diversion scheme for either a drug treatment court or Treatment Alternative Program (TAP) (Brown 2013).

Different outcome measures were presented for each study, and just over half of all studies reported four or more outcome measures (see Table 3). Criminal justice and drug outcomes were measured by all studies except four. Cornish 1997 and Lobmann 2007 reported on criminal activity outcomes only; and Bayanzadeh 2004, Brown 2013, Dolan 2003, Cropsey 2011 and Wright 2011 reported on drug use only.

Countries in which the studies were conducted

Nine studies were published in the US, two in England, one in Iran, one in Australia, one in Norway and one in Germany.

Duration of trials

Most studies (n = 10) reported outcomes of six months or less, and the longest follow‐up period was four years.

Participants

The fourteen studies included adult drug‐using offenders: twelve of the fourteen studies used samples with a majority of men and one study used female offenders only (Cropsey 2011). In two studies, gender was not reported (Lobmann 2007; Wright 2011).

The average age of study participants ranged from 27 years to 40.9 years.

Excluded studies

We excluded 165 studies. See Characteristics of excluded studies for further details. Reasons for exclusion were: lack of criminal justice involvement in referral to the intervention; not reporting relevant drug or crime outcome measures or both at both the pre‐ and post‐intervention periods; allocation of participants to study groups that were not strictly randomised or did not contain original trial data. The majority of studies were excluded because the study population were not offenders. One study was excluded because follow‐up periods were not equivalent across study groups (Di Nitto 2002); and Berman 2004 was excluded because the intervention (acupuncture) did not measure our specified outcomes of drug use or criminal activity. One study reported the protocol of a trial only (Baldus 2011); while another only contained conference proceedings (Kinlock 2009a). We were unable to obtain the data for one trial (Cogswell 2011); or the full‐text version of another (Rowan‐Szal 2005).

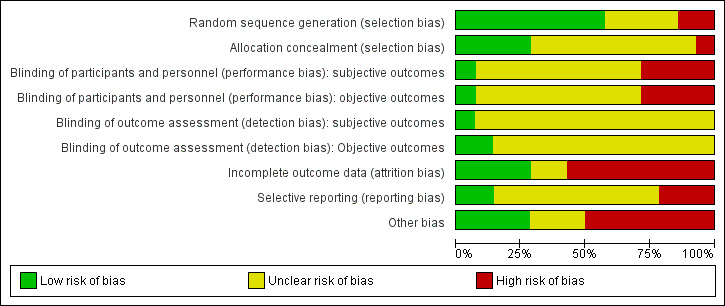

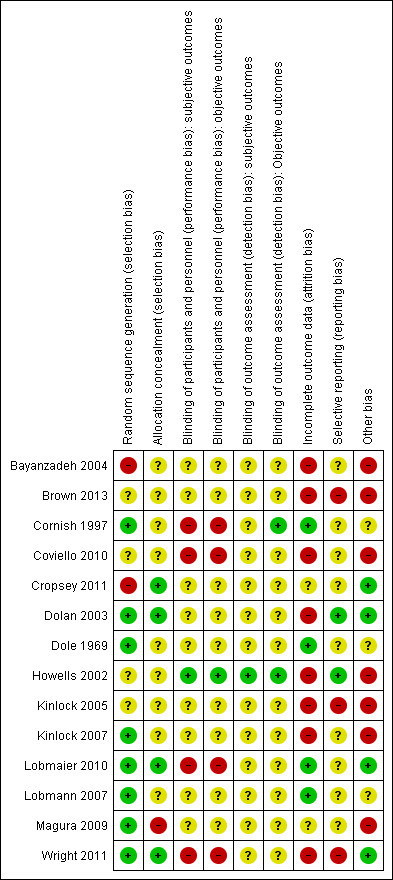

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 4 and Figure 5 for further information.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation: All of the 14 included studies were described as randomised. In four studies, the reporting of this information was noted as unclear, as it was difficult to find an accurate description of the methodology used (Brown 2013; Coviello 2010; Howells 2002; Kinlock 2005). Two studies were reported at high risk of bias (Bayanzadeh 2004; Cropsey 2011); and the remaining eight studies at low risk of bias.

Allocation concealment: Of the 14 included studies, only four reported that the allocation process was concealed and were rated at low risk of bias (Cropsey 2011; Dolan 2003; Lobmaier 2010; Wright 2011). One study was rated at high risk of bias (Magura 2009). All of the remaining nine studies were rated as unclear, and the review author was not able to decide whether allocation concealment had occurred within the studies.

Blinding

Blinding was assessed across four dimensions considering performance and detection bias across subjective and objective measures (see Appendix 14). Nine studies were rated as unclear risk of bias providing no information on blinding across all four domains (Bayanzadeh 2004; Brown 2013; Cropsey 2011; Dolan 2003; Dole 1969; Kinlock 2005; Kinlock 2007; Lobmann 2007; Magura 2009). Four studies were rated at high risk of bias for participant and personnel blinding (Cornish 1997; Coviello 2010; Lobmaier 2010; Wright 2011). Cornish 1997 was rated at low risk of outcome assessors on objective measures.

Incomplete outcome data

Four studies were noted at low risk of bias (Cornish 1997; Dole 1969; Lobmaier 2010; Lobmann 2007); eight studies were noted at high risk of bias; and two studies were rated as unclear (Cropsey 2011; Magura 2009).

Selective reporting

Of the 14 studies, nine studies were rated as unclear, and two studies were rated at low risk (Dolan 2003; Howells 2002). Three studies were rated at high risk of bias (Brown 2013; Kinlock 2005; Wright 2011).

Other potential sources of bias

Threats to other bias within the study designs generally yielded mixed results. In total, seven studies were rated at high risk. Low risk was noted in four further studies (Cropsey 2011; Dolan 2003; Lobmaier 2010; Wright 2011); and three studies were rated as unclear (Cornish 1997; Dole 1969; Lobmann 2007).

Effects of interventions

Of the 14 studies, 11 were included in a series of meta‐analyses and the main comparisons are presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2). Three studies were not included in the meta‐analyses: Bayanzadeh 2004 because it compared methadone + CBT versus not further specified non‐pharmacological treatment, so it was not possible to ascertain the effect of methadone treatment alone; Brown 2013 because it compared specialist treatment plus suboxone or methadone versus primary care plus suboxone, so it was not possible to ascertain the effect of methadone or suboxone alone; moreover it did not assess the outcomes of interest; and Howells 2002 because it did not assess the outcomes of interest and repeated attempted contact with the authors asking for more information was unsuccesful. For those studies that were included we grouped them by drug and criminal activity outcomes (re‐arrest and reincarceration), setting (community and secure establishment), and intervention type (buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone). Tests for heterogeneity at the 0.01 level revealed that across all meta‐analyses, the studies were found to be homogeneous.

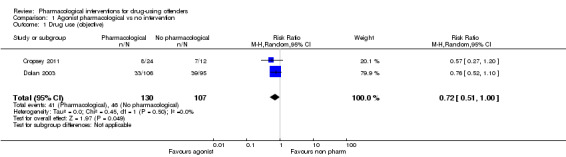

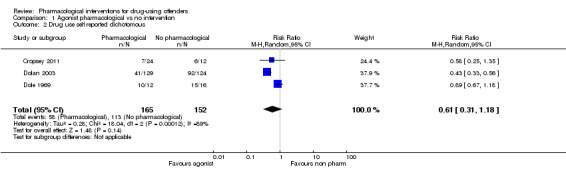

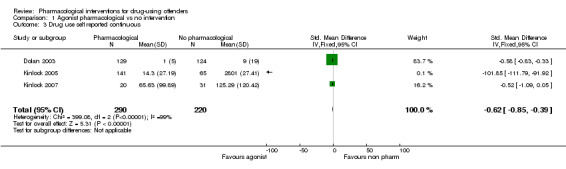

1. Agonist pharmacological interventions vs no non‐pharmacological treatment

Drug use

See Table 1

For dichotomous measure, results did not show reduction in drug use for objective results (biological), two studies, 237 participants: (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.00), low quality of evidence and for subjective (self‐report), three studies, 317 participants: (RR 0.61 95% CI 0.31 to 1.18), low quality of evidence. Also for continuous measures, self‐report drug use did not show differences, three studies, 510 participants: (SMD ‐0.62 95% CI ‐0.85 to ‐0.39), low quality of evidence, see Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; and Analysis 1.3.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agonist pharmacological vs no intervention, Outcome 1 Drug use (objective).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agonist pharmacological vs no intervention, Outcome 2 Drug use self reported dichotomous.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agonist pharmacological vs no intervention, Outcome 3 Drug use self reported continuous.

Criminal activity

See Table 1

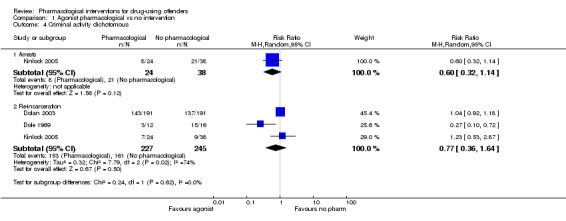

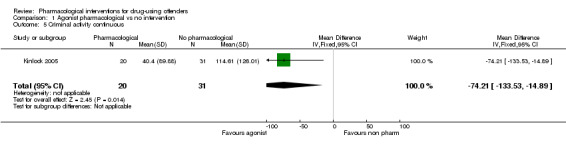

All data come from studies assessing the efficacy of methadone treatment. Both for reincarceration three studies, 472 participants (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.64) low quality of evidence; and re‐arrests, one study, 62 participants (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.14), low quality of evidence, the studies did not show difference (see Analysis 1.4). The impact on criminal activities was evaluated also utilising continuous measures in one study, 51 participants: MD of ‐74.21 (95% CI ‐133.53 to ‐14.89), low quality of evidence, the result is in favour of pharmacological interventions, (see Analysis 1.5).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agonist pharmacological vs no intervention, Outcome 4 Criminal activity dichotomous.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Agonist pharmacological vs no intervention, Outcome 5 Criminal activity continuous.

2. Antagonist (Naltrexone) pharmacological treatment vs non ‐pharmacological treatment?

See Table 2

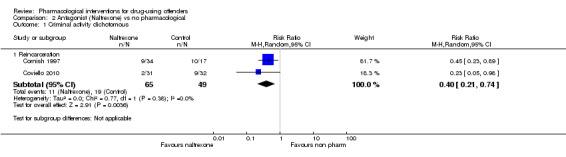

Two studies, 114 participants focused on the use of naltrexone versus no pharmacological treatment and subsequent criminal activity. The results indicate that naltrexone does appear to reduce subsequent reincarceration, with an RR of 0.40 (95% CI 0.21, 0.74), moderate quality of evidence, see Analysis 2.1

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antagonist (Naltrexone) vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Criminal activity dichotomous.

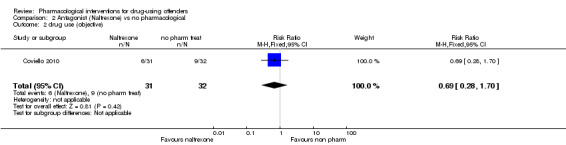

One study, 63 participants (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.70) did not show statistically significant difference, low quality of evidence, see Analysis 2.2,

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antagonist (Naltrexone) vs no pharmacological, Outcome 2 drug use (objective).

3. Methadone versus buprenorphine

Drug use

Two studies (Magura 2009; Wright 2011), showed a reduction in self report drug use for 370 participants using a dichotomous outcome (RR 1.04. 95% CI 0.69 to 1.55) altough the result is not statistically significant. Continuous outcomes, one study with 81 participants, (MD 0.70, 95% CI ‐5.33 to 6.73) see Analysis 3.1 and Analysis 3.2 .

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 1 Self reported drug use dichotomous.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 2 Self reported drug use continuous.

Criminal activity

Magura 2009 showed a non‐statistically significant reduction in criminal activity for 116 participants (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.88) see Analysis 3.3.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 3 Criminal activity dichotomous.

4. Methadone versus diamorphine

Drug use: the study did not assess this outcome

Criminal activity

Rearrest: One study, (Lobmann 2007) 825 participants shows a non‐statistically significant reduction in criminal activity for re‐arrests: (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.51 see Analysis 4.1.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Methadone vs diamorphine, Outcome 1 criminal activity dichotomous.

5. Methadone vs naltrexone

Drug use

Lobmaier 2010, 44 participants, showed a non‐statistically significant reduction in self reported drug use continuous MD 4.60 (95% CI ‐3.54 to 12.74) see Analysis 5.1.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 1 self reported drug use continuous.

Criminal activity

Lobmaier 2010, 44 participants, showed a non‐statistically significant reduction in dichotomous reincarceration, outcomes (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.37 to 3.26) and continuous outcomes (MD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐8.04 to 7.04) see Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 2 criminal activity dichotomous.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 3 criminal activity continuous.

Does setting of intervention (community, prison/secure establishment) affect outcomes of pharmacological interventions?

All the studies comparing methadone versus non‐pharmacological intervention were conducted in a secure setting; the only study comparing buprenorphine with non‐pharmacological intervention was conducted in the community, as well as the two studies comparing naltrexone with non‐pharmacological treatment. In the other comparison only one study was included for each, so it was not possible to perform a subgroup analysis for setting of the intervention.

Cost and cost‐effectiveness

The Magura study noted differences in the costs of administering buprenorphine and methadone, but were not sufficient for us to conduct a full cost effectiveness appraisal (Magura 2009). The investigators estimated that about ten times as many inmates can be served with methadone as with buprenorphine with the same staff resources. This cost implication is also endorsed in the community, where physicians have difficulty in obtaining reimbursement for buprenorphine treatment for released inmates, making the continued use of buprenorphine problematic after release.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review provides evidence from 14 trials producing several meta‐analyses. Studies could not be combined all together because the comparisons were too different. Only subgroup analysis for type of pharmacological treatment was done. Findings of the effects of individual interventions on drug use and criminal activity show mixed results. When compared to non‐pharmacological, we found low quality evidence that agonist treatments are not effective in reducing drug use or criminal activity. We found low quality of evidence that antagonist treatment was not effective in reducing drug use but we found moderate quality of evidence that they significantly reduced criminal activity. When comparing the drugs to one another we found no significant differences between the drug comparisons (methadone versus buprenorphine, diamorphine and naltrexone) on any of the outcome measures suggesting that no one pharmacological drug is more effective than another. Two studies provided some cost comparisons, but data were not sufficient to generate a cost‐effectiveness analysis. In conclusion, we found that pharmacological interventions do reduce subsequent drug use and (to a lesser extent) criminal activity. Additionally, we found individual differences and variation on different outcome measures when pharmacological interventions were compared to a non‐pharmacological treatment but no significant differences when compared to another pharmacological treatment.

Buprenorphine

The Cropsey study specifically evaluated buprenorphine for opioid‐dependent women with HIV risk and found that buprenorphine given to participants in prison (followed by its use upon release into the community) was beneficial in preventing or delaying relapse to opioid use (Cropsey 2011). The findings of this study add to the growing body of evidence (which primarily includes men) suggesting that outcomes with buprenorphine are comparable with what others have found with both methadone and methadone maintenance (Lobmaier 2010). The findings however were not sustained post treatment, and most women had relapsed to active opioid treatment at the three‐month follow‐up point. Future studies on the use of buprenorphine in women should evaluate its impact on long‐term effects with the goal of assessing its effect on opioid abstinence and prevention of associated criminal activity (Cropsey 2011). Overall, the dosage of buprenorphine varied between studies; in one study, instances of 30 mg rising to 130 mg were reported (Lobmaier 2010). A meta‐analysis of buprenorphine dose and treatment outcome found that a higher dosage (16 to 32 mg per day) predicted better retention in treatment when compared with a lower dosage (Fareed 2012). Another Cochrane review (outside the prison environment) indicated that buprenorphine detoxification and maintenance studies concluded that completion of withdrawal treatment is possibly more likely when managed with buprenorphine compared to methadone although the difference was not statistically significant, leading the authors to conclude that more research is needed to evaluate the possible differences between the two medications (Gowing 2009). The Wright 2011 study in this review suggests that there is equal clinical effectiveness between buprenorphine and methadone in maintaining abstinence at eight days post detoxification in prison. As many prisoners are eventually released back into the community the authors note that GPs need to be aware of the few trials which compare two of the most common detoxification agents in the UK. The research currently supports the use of either buprenorphine or methadone within a detoxification setting (Wright 2011).

Methadone

Two studies showed a decrease in self‐report methadone treatment upon release into the community (Dole 1969; Magura 2009). The Dole study, albeit small, found that 3 of 12 prisoners who started using methadone before release were convicted of new crimes during an 11.5‐month follow‐up compared with 15 of 16 prisoners randomly assigned to a control condition (Dole 1969); and a larger, more recent study found that Rikers Island MMT programme in New York significantly facilitated entry and retention at six months in post release programmes (Magura 2009). In contrast, another study reported on opioid agonist maintenance by examining levo‐alpha‐acetylmethadol (LAAM) before prison release and found no significant differences with regard to subsequent arrest of participants who received LAAM and a control group at nine months post‐release (Kinlock 2005). Subsequent Kinlock studies involving evaluations of counselling only and counselling with transfer in comparison with counselling and methadone support the findings of Dole 1969 and Dolan 2003 suggesting that methadone programmes can provide effective opioid agonist therapy for prisoners with a history of heroin addiction but not arrest at 12 month post prison release (Kinlock 2007). Taken together, the findings also suggest that increased criminal activity and overdose death are disproportionately likely to occur within one month of release from incarceration. The authors conclude that making connections with drug treatment services at release from prison is likely to help sustain treatment for opiod addictions; such findings are supported by other studies which found that offering pre‐release MMT and payment assistance was significantly associated with increased enrolment in post‐release MMT and reduce time to enter community‐based MMT (e.g. Binswanger 2007). Additionally, in support of methadone treatment, the World Health Organisation has listed methadone as an essential medication and has strongly recommended that treatment should be made available in prison and supported subsequently within the community to significantly reduce the likelihood of adverse health and criminogenic consequences (Hergert 2005).

Dosage of methadone treatment varied across studies. For example, Magura 2009 reported problems with the use of suboptimal doses of methadone when higher doses were available. Investigators argue that higher doses appear to reflect participant preference because most did not intend to continue treatment after release. The Dolan study reported moderate doses of methadone (61 mg) and noted that outcomes might have improved if higher doses had been given (Dolan 2003). Significantly lower doses of methadone were noted in the Dole study, in which 10 mg of methadone per day was increased to a dosage of 35 mg per day (Dole 1969). Participants in the Kinlock 2005 study were medicated three times per week, starting at 10 mg and increasing by 5 mg every third medication day during incarceration to a target dose of 50 mg. Evidence from the Amato 2005 review suggests that low dosages of methadone maintenance lead to compromise in the effectiveness of treatment and that recommendations for dosage should be monitored at around 60 mg. Additional systematic review evidence considering the use of methadone and a tapered dose for the management of opioid withdrawal shows a wide range of programmes with differing outcome measures, making the application of meta‐analysis difficult (Amato 2013). The authors conclude that slow tapering with temporary substitution of long‐acting opioids can reduce withdrawal severity; however, most participants still relapsed to heroin use (Amato 2013).

Naltrexone

For evaluation of naltrexone, two studies (one pilot: Cornish 1997) and Coviello 2010, a subsequent larger replication trial, show that use of a larger sample size consisting of a diverse group of offenders resulted in no differences in criminal behaviour between naltrexone and treatment‐as‐usual groups. The authors note that one of the major differences between the two studies remains the extent and quality of supervision provided by parole officers. The authors suggest that for treatment to be successful, use of oral naltrexone by probationers and parolees requires more supervision than is typically available within the criminal justice system. Study authors reported instances of 35 mg of naltrexone rising to 300 mg (Coviello 2010). Other research evidence related to naltrexone use and mortality rates highlights possible concerns about the high risk of death after treatment. Gibson 2007 compared mortality rates associated with naltrexone and methadone by using retrospective data analysis of coronial participants between 2000 and 2003. Findings show that participants receiving naltrexone were up to 7.4 times more likely to die after receiving treatment when compared with those using methadone over the same time period. Although this study was not conducted in a population of prisoners, it is likely that such risks are comparable; therefore generalised use of naltrexone and associated subsequent supervision of those taking naltrexone in its oral form require careful consideration.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall, the findings of this review suggest that pharmacological interventions have an impact on reducing self‐report drug use. Individual pharmacological drugs had differing effects, particularly in relation to subsequent drug use. Promising results highlight the use of methadone or buprenorphine (although this was only one study) within a prison environment but may be limited to shorter‐term outcomes when prisoners are released into the community. For naltrexone, the evidence is sparse and presents problems associated with different mechanisms of drug administration (e.g. oral versus implants). We can say little about the cost and cost‐effectiveness of these studies. One study reported some descriptive cost information, but the information was insufficient to generate a cost analysis (Magura 2009). In conclusion, high‐quality research is required to evaluate the processes involved in the engagement of offenders mandated to substance abuse programmes to enable us to understand better why one programme works and another does not.

Quality of the evidence

A number of limitations within each of the studies are highlighted by the authors. High dropout rates were noted in the methadone group after prison release in the Lobmaier study and appear to be more difficult to maintain in offender populations (Lobmaier 2010). Major limitations of the Coviello 2010 study included low treatment retention and low six‐month follow‐up rates. Most offenders did not return for the follow‐up evaluation because they could not be located (63%). Only two‐thirds of treated participants remained in treatment in the Dolan study (Dolan 2003). As a consequence, the study does not provide conclusive evidence regarding the efficacy of oral naltrexone in this offender sample. Attrition was also a problem in Kinlock 2005; this was due in part to the fact that individuals were being transferred to other prisons or were having their sentences extended because of pre‐existing charges (Kinlock 2005). Similiar problems of segregation and impact of sentence releases affected the sample size in the Bayanzadeh 2004 and Wright 2011 studies whereby transfer to other prison establishments with little prior warning made follow‐up data difficult to collect. Such attrition within studies threatens the comparability of experimental and control groups, thereby ensuring that any conclusions should be taken with considerable caution. In particular, the Bayanzadeh 2004 study noted some of the practical difficulties associated with contamination between experimental and control groups, given that the ideal would be to keep the groups apart. In contrast the pilot study by Brown 2013 produced a study retention rate of 80%; the authors note that this may be due to the coercive nature of participation in jail diversion programs in which successful completion may result in the dismissal or reduction of criminal charges. Although this finding is represented by only one study it suggests the possibility that completion of drug treatment programs might fare best when an incentive which effects sentence or charge outcome can be sustained.

Sample sizes were considered modest in a number of studies, with attrition presenting difficulties in interpretation of study findings. For example, 30% attrition at follow‐up producing possible threats to the internal validity of the study design in Magura 2009 and similar small sample sizes in the Lobmaier trial may have been too small to reveal any differences between the two treatment conditions (Lobmaier 2010). The Cropsey 2011 study identified a sample of 36 women and randomly allocated 15 to the intervention and 12 to the placebo group. Investigators note that although the potency of buprenorphine for control of opioid use is clearly demonstrated, a larger sample size may be needed to detect significant differences between groups on other variables of interest. Larger trials are therefore required to assess the possible advantages of one treatment over the other. Additionally, the study was limited to three months of treatment, and further studies should explore the provision of buprenorphine for longer periods of time to prolong opioid abstinence and prevent associated criminal activity. Similiar short follow‐up periods were noted in other trials, including Dolan 2003.

Potential biases in the review process

Despite limitations associated with the literature, two limitations in review methodology were achieved. Specifically, the original review included an additional five fee paying databases and one search using DrugScope. In this current review resources did not allow such extensive searching. Whislt the electronic databases searches have been updated to April 2014. the web site search has been updated to November 2011. As a result some literature may have been missed from this current review

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

When compared to non‐pharmacological treatments, agonist treatments did not seem effective in reducing drug use or criminal activity Antagonist treatment was not effective in reducing drug use but significantly reduced criminal activity. When comparing the drugs to one another we found no significant differences between the drug comparisons (methadone versus buprenorphine, diamorphine and naltrexone) on any of the outcome measures. Caution should be taken when interpreting these findings, as the conclusions are based on a small number of trials, and generalisation of these study findings should be limited mainly to male adult offenders. Additionally, many studies were rated at high risk of bias because trial information was inadequately described.

Implications for research.

Several research implications can be identified from this review.

Generally, better quality research is required to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions with extended long‐term effects of aftercare following release into the community.

Buprenorphine research in the prison environment requires evidence of the long‐term impact and larger studies, currently an equivalence of buprenorphine and methadone exists.

Evidence for naltrexone is less convincing. Trials evaluating differences between oral and implantation naltrexone and associated supervision requirements under the criminal justice system are required.

Only one court diversion study was identified: exploration of some court diversionary schemes using different pharmacological interventions would be useful.

Future clinical trials should collect information from all sectors of the criminal justice system. This would enhance the heterogeneous nature of the included studies and would facilitate generalisation of study findings.

Evidence of comparable mortality rates in prisoners using pharmacological interventions (particularly after release) needs to be explored to assess the long‐term outcomes of such treatments.

The link between dosage, treatment retention and subsequent criminal activity should be examined across all three pharmacological treatment options. Evidence from other trial data suggests that dose has important implications for retention in treatment; in future studies, this should be considered alongside criminal activity outcomes.

Cost and cost‐effectiveness information should be standardized within trial evaluations; this will help policymakers to decide upon health versus criminal justice costs.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 March 2015 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | In the previous version pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders appeared to reduce overall subsequent drug use and criminal activity (but to a lesser extent), while with the introduction of new studies agonist treatments did not seem effective in reducing drug use or criminal activity. |

| 29 July 2014 | New search has been performed | This latest update reflects an additional four new trials (and one ongoing trial) with new follow‐up data on two existing trials with searches conducted up until May 2014 |

History

Review first published: Issue 12, 2013

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 January 2014 | Amended | Plain language summary title correction |

| 16 July 2012 | New search has been performed | This review has been updated using searches to 21 March 2013. The review represents one in a family of four reviews. The other reviews cover non‐ pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders and interventions for drug‐using female offenders and offenders with co‐occurring mental illness. This new review of pharmacological interventions with drug‐using offenders contains 17 randomised controlled trials. Six of the 17 trials are awaiting classification for the review; the remaining 11 trials represent a total of 2,678 participants. |

| 2 March 2012 | New search has been performed | The updated edit of this review produced a new document with additional findings reflecting searches up to 11 November 2011. Five new review authors have been added to this version of the review, including Steven Duffy, Rachael McCool, Matthew Neilson, Catherine Hewitt and Marrissa Martyn‐St James. |

| 19 May 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the help of the York Health Economics Consortium and The Health Sciences Department at the University of York and the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

| MEDLINE search |

| 1. exp "Substance‐Related‐Disorders"/ |

| 2. ((drug or substance) adj (abuse* or addict* or dependen* or misuse*)).ti,ab |

| 3. (drug* adj (treat* or intervention* or program*) |

| 4. substance near (treat* or intervention* or program*) |

| 5.(detox* or methadone) in ti,ab |

| 6. narcotic* near (treat* or intervention* or program*) |

| 7. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| 8. prison*. ti,ab |

| 9. exp "Prisoners"/ |

| 10. offender* or criminal* or inmate* or convict* or probation* or remand or felon*).ti,ab |

| 11. exp "Prisons"/ |

| 12. 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 |

| 13. 7 and 12 |

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

| Embase search |

| 1. (detox$ or methadone or antagonist prescri$).ti,ab. |

| 2. detoxification/ or drug detoxification/ or drug withdrawal/ or drug dependence treatment/ or methadone/ or methadone treatment/ or diamorphine/ or naltrexone/ |

| 3. (diamorphine or naltrexone or therapeutic communit$).ti,ab. |

| 4. morality/ |

| 5. (motivational interview$ or motivational enhancement).ti,ab. |

| 6. (counselling or counseling).ti,ab. |

| 7. exp counseling/ |

| 8. (psychotherap$ or cognitive behavioral or cognitive behavioural).ti,ab. |

| 9. exp psychotherapy/ |

| 10. (moral adj3 training).ti,ab. |

| 11. (cognitive restructuring or assertiveness training).ti,ab. |

| 12. reinforcement/ or self monitoring/ or self control/ |

| 13. (relaxation training or rational emotive or family relationship therap$).ti,ab. |

| 14. social learning/ or withdrawal syndrome/ or coping behavior/ |

| 15. (community reinforcement or self monitoring or self control or self management or interpersonal skills).ti,ab. |

| 16. (goal$ adj3 setting).ti,ab. |

| 17. (social skills adj3 training).ti,ab. |

| 18. anger/ or lifestyle/ |

| 19. (basic skills adj3 training).ti,ab. |

| 20. (relapse adj3 prevent$).ti,ab. |

| 21. (craving adj3 (minimi$ or reduc$)).ti,ab. |

| 22. (trigger or triggers or coping skills or anger management or group work).ti,ab. |

| 23. (lifestyle adj3 modifi$).ti,ab. |

| 24. (high intensity training or resettlement or throughcare or aftercare or after care).ti,ab. |

| 25. aftercare/ or halfway house/ |

| 26. (brief solution or brief intervention$ or minnesota program$ or 12 step$ or twelve step$).ti,ab. |

| 27. (needle exchange or nes or syringe exchange or dual diagnosis or narcotics anonymous).ti,ab. |

| 28. self help/ or support group/ |

| 29. (self‐help or selfhelp or self help or outreach or bail support or arrest referral$).ti,ab. |

| 30. exp urinalysis/ or rehabilitation/ or rehabilitation center/ |

| 31. (diversion or dtto or dttos or drug treatment or testing order$ or carat or carats).ti,ab |

| 32. (combined orders or drug‐free or drug free).ti,ab. |

| 33. (peer support or evaluation$ or urinalysis or drug testing or drug test or drug tests).ti,ab. |

| 34. ((rehab or rehabilitation or residential or discrete) adj2 (service$ or program$)).ti,ab. |

| 35. (asro or addressing substance$ or pasro or prisons addressing or acupuncture or shock or boot camp or boot camps).ti,ab. |

| 36. (work ethic camp$ or drug education or tasc or treatment accountability).ti,ab |

| 37. exp acupuncture/ |

| 38. or/1‐36 |

| 39. (remand or prison or prisoner or prisoners or offender$ or criminal$ or probation or court or courts).ti,ab. |

| 40. (secure establishment$ or secure facilit$).ti,ab. |

| 41. (reoffend$ or reincarcerat$ or recidivi$ or ex‐offender$ or jail or jails or goal or goals).ti,ab. |

| 42. (incarcerat$ or convict or convicts or convicted or felon or felons or conviction$ or revocation or inmate$ or high security).ti,ab. |

| 43. criminal justice/ or custody/ or detention/ or prison/ or prisoner/ or offender/ or probation/ or court/ or recidivism/ or crime/ or criminal behavior/ or punishment/ |

| 44. or/39‐43 |

| 45. 38 and 44 |

| 46. (substance abuse$ or substance misuse$ or substance use$).ti,ab. |

| 47. (drug dependanc$ or drug abuse$ or drug use$ or drug misuse$ or drug addict$).ti,ab. |

| 48. (narcotics adj3 (addict$ or use$ or misuse$ or abuse$)).ti,ab. |

| 49. (chemical dependanc$ or opiates or heroin or crack or cocaine or amphetamines or addiction or dependance disorder or drug involved).ti,ab. |

| 50. substance abuse/ or drug abuse/ or analgesic agent abuse/ or drug abuse pattern/ or drug misuse/ or intravenous drug abuse/ or multiple drug abuse/ |

| 51. addiction/ or drug dependence/ or narcotic dependence/ or exp narcotic agent/ or narcotic analgesic agent/ |

| 52. opiate addiction/ or heroin dependence/ or morphine addiction/ |

| 53. cocaine/ or amphetamine derivative/ or psychotropic agent/ |

| 54. or/46‐53 |

| 55. 45 and 54 |

Appendix 3. PsycInfo search strategy

| PsycInfo |