Abstract

Whereas the conventional anti-dihalogenation of alkenes is a valuable synthetic tool with highly predictable stereospecificity, the restricted reaction mechanism makes it challenging to alter the diastereochemical course into the complementary syn-dihalogenation process. Only a few notable achievements were made recently by inverting one of the stereocenters after anti-addition using a carefully designed reagent system. Here, we report a conceptually distinctive strategy for the simultaneous double electrophilic activation of the two alkene carbons from the same side. Then, the resulting vicinal leaving groups can be displaced iteratively by nucleophilic halides to complete the syn-dihalogenation. For this purpose, thianthrenium dication is employed, and all possible combinations of chlorine and bromine are added onto internal alkenes successfully, particularly resulting in the syn-dibromination and the regiodivergent syn-bromochlorination.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Stereochemistry, Reaction mechanisms

Restricted reaction mechanism of anti-dihalogenation of alkenes makes it challenging to alter the diastereochemical course into the complementary syn-dihalogenation process. Here, the authors report a conceptually distinctive strategy for the simultaneous double electrophilic activation of the two alkene carbons from the same side to realize syn-dihalogenation.

Introduction

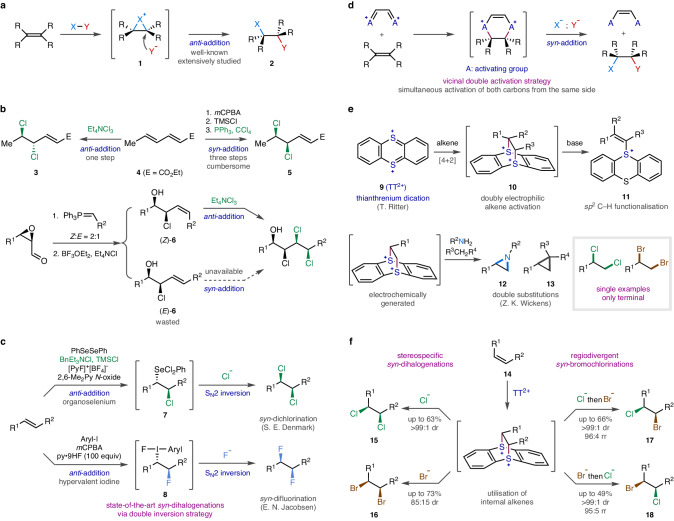

Traditional oxidative 1,2-dihalogenation of alkenes with common electrophilic reagents such as elemental dihalogens (Cl2, Br2) generally proceeds via the intermediacy of a cationic cyclic species (1), a haliranium ion, resulting in stereospecific anti-addition (2) upon the subsequent stereo-invertive SN2 displacement by halide from the opposite side (Fig. 1a)1. Such transformation is one of the oldest and most well-established reactions in organic chemistry and thus has been widely utilised as a straightforward synthetic tool to access vicinal dihalides from geometrically defined alkenes with predictable stereospecificity2. However, because of the highly restricted reaction mechanism, it has been nearly impossible to alter the stereochemical course. Consequently, the complementary syn-dihalogenation process is rare3 and often approached via a multi-step operation4–7. For example, cis−1,2-dichlorocyclohexane is produced through a sequence relying on an available syn-stereospecific alkene activation such as epoxidation followed by deoxydichlorination8, which indicates that syn-dichlorination methods are underdeveloped. Moreover, the relative configuration of vicinal dihalide products is dependent on the geometry of the starting alkenes, and thus the synthetic utility of dihalogenations has often been limited by the accessibility of the desired alkene geometry because only one diastereochemical course has been available (Fig. 1b). During the study on conformational and configurational analysis of chlorinated natural products by the Carreira group9, the preparation of anti-dichloride (3) was easily accomplished by the straightforward single-step dichlorination of the naturally occurring E-isomer of ethyl sorbate (4) with Et4NCl3. On the other hand, the corresponding syn-dichloride (5) had to be synthesised by a cumbersome three-step operation involving alkene epoxidation and two iterative deoxychlorinations because the Z-isomer of ethyl sorbate was not readily available. syn-Dihalogenation would also be useful when the alkene reactant is produced as a separable mixture of geometrical isomers. For instance, the alkene intermediates 6 were obtained with poor E/Z selectivity via the Wittig or the Julia olefinations during the syntheses of chlorosulfolipids by the Vanderwal group10–14 and the Carreira group15–17, and only (Z)-6 could be further utilised for the subsequent anti-dichlorination step. The presence of a syn-addition method would have enabled the transformation of (E)-6 into the same desired dichlorination product, thereby increasing the overall efficiency of the synthesis. Additionally, instead of relying on poorly Z-selective Wittig olefination in the previous step, it would have been possible to consider highly E-selective olefination, which was unfortunately not a viable option. Clearly, it is highly desirable to develop diverse syn-stereospecific alternatives, which will greatly simplify the current multi-step synthetic route and provide invaluable synthetic tools for organic chemists.

Fig. 1. Research outline.

a Traditional anti-dihalogenation. b Needs for complementary syn-dihalogenation. c Current state-of-the-art via double inversion strategy. d Our approach of vicinal double activation strategy. e Thianthrenium dication as doubly electrophilic alkene activator and its usage. f This work: syn-stereospecific and regiodivergent dihalo- and interhalogenations.

In the past decade, whereas the conventional anti-dihalogenation chemistry has advanced remarkably, as highlighted by the realisations of enantioselective variants18–25, the stereochemically opposite syn-dihalogenation has received much less attention. Only recently, a few notable accomplishments have been reported (Fig. 1c). In 2015, the Denmark group developed the first example of generally applicable, one-step syn-dichlorination of alkenes by taking advantage of organoselenium’s susceptibility to oxidation26,27. After the well-established anti-addition of phenylselenyl chloride across a C=C bond, the facile in-situ oxidation of the selenium(II) species leads to the formation of a highly electron-deficient selenium(IV) leaving group (7), allowing the subsequent SN2 displacement by chloride to result in overall syn-addition. Shortly after, in 2016, diastereoselective 1,2-difluorination of alkenes including syn-stereospecific examples was developed by the Jacobsen group with hypervalent iodine(III) difluoride28. This reaction proceeds in a similar fashion via anti-iodofluorination (8) followed by stereo-invertive nucleophilic substitution of iodine(III) with fluoride. Although these two pioneering examples are remarkable achievements, there still are drawbacks. The reaction conditions involve either a complex combination of several reagents or a large excess of toxic substance. In addition, E2 elimination is often accompanied as a competing side reaction. Moreover, syn-dibromination remains elusive29. Furthermore, scope expansion with two different halogen species would be an even harder challenge, which cannot be addressed by the currently available approaches. Therefore, this important research field is still at a very early stage of development, and the invention of a mechanistically distinctive syn-dihalogenation is highly desired.

To that end, we devised a synthetic strategy, in which the two carbons of alkene are simultaneously activated from the same side with two electron-deficient moieties via a stereospecific transformation such as cycloaddition (Fig. 1d). Then, each electrophilic carbon can be displaced by halide to give the syn-dihalogenated product. Whereas one leaving group is shared by both carbons in the traditional alkene dihalogenation, allowing only one substitution, each carbon has its own leaving group in our case, and thus two displacements can proceed to alter the diastereochemical outcome. A reagent with such a doubly electrophilic property has been recently developed by the Ritter group (Fig. 1e)30,31. It was reported that thianthrenium dication (9, TT2+) could be utilised for the stereospecific construction of two vicinal C–S+ bonds on the same side of alkenes simultaneously through a hetero Diels–Alder reaction. However, this species has rarely been employed for substitution chemistry. In most cases, the bissulfonium intermediate (10) was treated with a base to form S-alkenyl thianthrenium cation (11), which was then manipulated in various ways, resulting in overall sp2 C–H functionalisation. Furthermore, although the cycloadducts have been characterised with internal alkenes such as (E)- and (Z)−4-octenes30, the typical substrate scope includes mostly terminal alkenes and a few cyclic ones. The most notable examples of double substitutions were disclosed recently by the Wickens group for the efficient synthesis of N-alkyl aziridines (12)32 and cyclopropanes (13)33 as well as for regiospecific 1,2-aminofunctionalisations34. In their study, a cationic pool of the thianthrenium-activated species was generated via a carefully modulated electrochemical oxidation and subsequently reacted with various nitrogen or carbon nucleophiles35. Then, as a scope expansion, other nucleophiles including halides were also examined, and the feasibility of 1,2-dihalogenation was demonstrated32. However, only a single example for each halogen (Cl and Br) was described. More critically, only terminal alkenes could be employed in their reaction system, and thus complex stereochemical aspects such as stereospecificity could not be addressed. Nonetheless, on the basis of these precedents, we saw a promising potential from TT2+ as it possesses the desired properties for our reaction concept of stereospecific vicinal double electrophilic activation of alkenes.

Herein, we describe syn-stereospecific and regiodivergent installations of all possible combinations of chlorine and bromine onto alkenes utilising TT2+ and organic-soluble halides (Fig. 1f). Remarkably, it is worth noting that syn-dibromination (16) and syn-bromochlorinations (17 and 18) are accomplished through this approach. Furthermore, the evidence for direct stereospecific substitutions of the dicationic alkene-TT2+ adduct is provided through mechanistic studies.

Results and discussion

Stereospecific syn-dihalogenations

Our initial reaction condition screening was carried out with a disubstituted (Z)-alkene 14a (1.0 equiv), thianthrene-S-oxide (19, TTO, 1.0 equiv), triflic anhydride (Tf2O, 1.0 equiv), and tetra-n-butylammonium chloride (3.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C (Table 1). After the formation of the cycloadduct 10, SN2 substitutions of the sulfoniums by two chlorides afforded the desired syn-dichlorinated product 15a in 61% yield with complete diastereoselectivity (entry 1). When a smaller amount of chloride was used, the product yield was decreased because of the incomplete conversion (entry 2). The use of an excess amount of n-Bu4NCl led to a slightly improved yield, but the operation became cumbersome (entry 3). No meaningful change was observed upon dilution or concentration (entries 4 and 5). Moreover, the chlorination step at different temperatures resulted in attenuated yield and/or diastereoselectivity (entries 6 and 7). In addition, the examination of another quaternary ammonium countercation, Me3PhNCl as a chloride source provided a lower yield (entry 8). Furthermore, an extensive survey of solvents was conducted, but inferior conversions were obtained mostly because of the poor solubility of the ionic intermediate 10 and/or halide reagent (See Section 2.6 of the Supplementary Information).

Table 1.

Reaction condition optimisation for syn-dichlorinationa

| Entry | Deviation from standard conditions | Yield (%)b | drc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 61 | >99:1 |

| 2 | 2.0 equiv of n-Bu4NCl | 52 | >99:1 |

| 3 | 5.0 equiv of n-Bu4NCl | 63 | >99:1 |

| 4 | 0.13 M concentration | 62 | >99:1 |

| 5 | 0.40 M concentration | 56 | >99:1 |

| 6 | n-Bu4NCl addition at rt | 55 | 97:3 |

| 7 | n-Bu4NCl addition at –20 °C | 57 | >99:1 |

| 8 | Me3PhNCl as chloride source | 44 | >99:1 |

Bz benzoyl, TTO thianthrene-S-oxide, Tf trifluoromethanesulfonyl, dr diastereomeric ratio.

aStandard conditions: 1.0 mmol scale at 0.25 M concentration.

bIsolated yields after column chromatography.

cDetermined by 1H NMR analysis of the purified materials.

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, the scope of syn-dihalogenation was evaluated (Fig. 2). When the benzoate group was located in closer proximity to the alkene compared to 15a, a reasonably high diastereoselectivity was obtained with a similar yield (15b). The marginal erosion of stereospecificity may have been caused by the competitive anchimeric assistance of the pendant nucleophile36. A slightly bulkier ethyl group was well-tolerated, providing a good yield and an excellent diastereoselectivity (15c). The impact of steric hindrance became apparent with the introduction of a β-branched isobutyl group, leading to a substantially attenuated yield but with a still excellent diastereoselectivity (15d). In the absence of nearby branching, long primary alkyl chains were amenable on both sides of alkene (15e). A few heteroatom-containing moieties such as thiophene (15f), benzodioxole (15g), and phthalimide (15h) were also compatible. Unfortunately, a tethered alkyl ether function appeared to cause the decomposition of the bissulfonium intermediate. Nonetheless, by conducting the chlorination immediately, one minute after thianthrenation, the reactive cycloadduct could be preserved in some degree, and the desired product was obtained with moderate efficiency (15i). Such interference was marginally alleviated by employing a bulky silyl ether, providing 15j in an improved yield. However, aryl ether was even more problematic because TT2+ (9) was intercepted by electron-rich arene, and thus the corresponding dichloride was not detected at all (not shown), being consistent with the well-established aryl C–H activating property of 937–42. In the presence of two electronically distinct alkenes, chemoselectivity was observed as only the relatively electron-rich alkene underwent syn-dichlorination (15k). Subsequently, the halogen scope was expanded to syn-dibromination, which has never been realised before. Gratifyingly, 16a was obtained by employing tetra-n-butylammonium bromide in a high yield with an appreciable level of 83:17 diastereoselectivity, constituting a significant example of syn-dibromination. The slight loss of stereospecificity compared to the chlorination counterpart (15a) was probably caused by the neighbouring group participation of the first-installed bromine substituent, which would promote the anti-addition pathway involving a cyclic bromiranium species43–47. From the examination of a few other substrates, the corresponding syn-dibrominated products (16f, 16h, and 16m) were successfully afforded with synthetically useful yields and diastereoselectivities. Subsequently, the influence of alkene geometry was evaluated. To our delight, a complete diastereoselectivity was obtained from syn-dichlorination of (E)-alkene (15l) although a prolonged reaction time was required to achieve a reasonable yield. In the case of syn-dibromination, the high reactivity was maintained, but the portion of the syn-addition isomer was decreased (16l) probably because the bromiranium formation became geometrically favourable enough to outcompete the second bromide attack. On the other hand, the attempts with iodide and fluoride nucleophiles did not provide the 1,2-dihalides under similar reaction conditions.

Fig. 2. Substrate scope of syn-dichlorination and syn-dibromination.

aAll reactions were performed on 1.0 mmol scale at 0.25 M concentration. Isolated yields after column chromatography are given. Diastereomeric ratios (dr) were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the purified materials. bChlorination at –40 °C. cWith 1.2 equiv of TTO and Tf2O. dThianthrenation for 1 minute. eWith 1.1 equiv of Tf2O. fChlorination for 5 hours. (Phth = phthaloyl, TBDPS = tert-butyldiphenylsilyl).

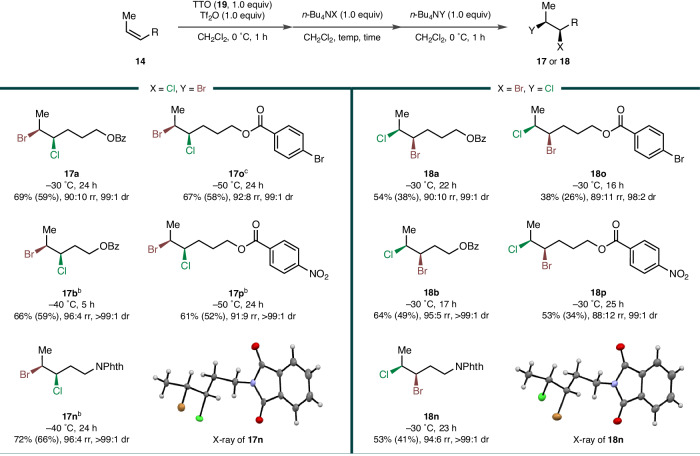

Regiodivergent syn-bromochlorination

During the optimisation of the reaction conditions, it was noticed that the first nucleophilic substitution occurred significantly faster than the second substitution. Furthermore, it was observed that the first halide addition exhibited high site-selectivity, leading to the formation of a monohalogenated TT+ intermediate with excellent isomeric purity (Fig. 3). Therefore, it was hypothesised that the second halogenation could be performed with a different halide. Indeed, the sequential treatment with chloride and then bromide resulted in a syn-interhalogenation. Although site-selective difunctionalisation of terminal alkene-TT2+ adduct was reported before34, such high positional discrimination with internal alkenes had never been realised prior to our work. Even more remarkably, the regiochemistry could be inverted simply by reversing the addition order, allowing access to both constitutional isomers 17 and 18.

Fig. 3. Regiodivergent syn-Interhalogenation.

Site-selective sequential additions of two different halides.

For the successful operation of these site-selective interhalogenations, the first halogenation must be completed without overhalogenation. The premature addition of the second halide before the full consumption of the bissulfonium species would complicate the reaction outcome via unordered halogen combinations such as homo-dihalogenation and halogen scrambling. Therefore, the first step was conducted at a low temperature with strictly one equivalent of the halide reagent for an extended period of time. Even though the reaction is substantially slowed down, especially with less nucleophilic chloride, an excess amount should not be used. Furthermore, in some cases, the ionic reaction intermediates became insufficiently soluble under the modified conditions, which necessitated the addition of a polar solvent such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) to compensate for the decreased solubility and thereby increase the reaction rate.

The scope of regiodivergent syn-bromochlorination was examined with several (Z)-alkenes 14 under slightly adjusted conditions for each substrate (Fig. 4) (See Sections 2.7 and 2.8 of the Supplementary Information). Although small amounts of homo-dihalides and constitutional isomers were formed as inseparable side products, the desired syn-bromochlorides 17 and 18 were successfully obtained as the major components with high site-selectivity and excellent diastereoselectivity. Again, benzoates and phthalimide at variable proximity were tolerated. Notably, when the electron-withdrawing group was closer to the reacting alkene, the site-selectivity was improved (17a/18a vs 17b/18b). The efficiency was somewhat attenuated when bromide was added first (18) probably because of the internal nucleophilic participation of the bromine substituent as the formation of a transient bromiranium intermediate may have scrambled the position of the second substitution. Nonetheless, such high levels of controllable regiochemical discretion have never been realised even for the more studied anti-bromochlorination19,22,24,47. The site-selectivity and syn-stereospecificity of both bromochlorinations were unambiguously established by the X-ray crystallographic analysis of 17n and 18n (See Section 3.1 of the Supplementary Information).

Fig. 4. Substrate scope of regiodivergent syn-bromochlorination.

aAll reactions were performed on 1.0 mmol scale at 0.25 M concentration. Yields of the isolated materials after column chromatography are given, and the calculated yields of the interhalides are shown in the parenthesis. Diastereomeric ratios (dr) and regioisomeric ratios (rr) were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the purified materials. bWith 0.3 mL of DMF. cWith 0.5 mL of DMF.

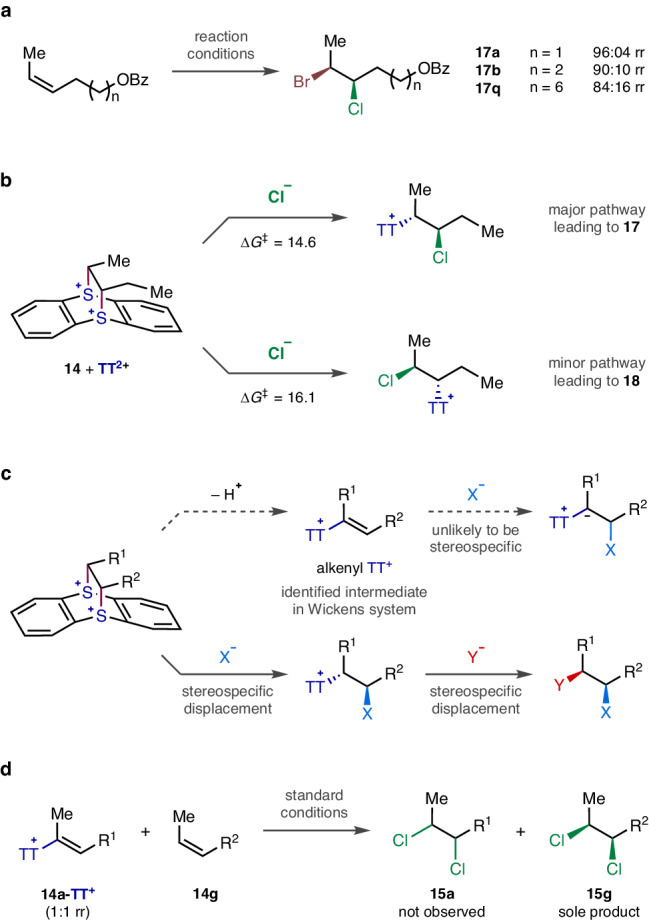

Mechanistic studies

Through the inspection of the experimental results from the bromochlorinations, a few mechanistic aspects regarding selectivities are discussed (Fig. 5). At first glance, the site-selectivity appears to be influenced to some extent by the electronic difference between the two alkyl substituents because the selectivity decreases as the electron-withdrawing benzoate group moves away from the reacting alkene (Fig. 5a, 17a vs 17b). To test this hypothesis, a substrate with a much longer alkyl tether was examined so that the electronic bias would become negligible. However, only a marginally altered, still comparably high site-selectivity was obtained (17q), suggesting that the electronic effect is a minor determining factor. Instead, the steric difference is more likely to be responsible for the discriminated attack of nucleophile48. To account for the observed site-selectivity, the first halogenation must take place preferably at the more substituted methylene side. The nucleophilic chlorination of a bissulfonium species (14 + TT2+) was analysed as a representative process via the density functional theory calculation using the GAMESS(US) 2018 software package49–51 at the wB97X-D/6-31 + G(d,p)/PCM(CH2Cl2) level of theory (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Data 1)52–56. The computed activation energy difference between the two isomeric pathways is ca. 1.5 kcal/mol favouring the major constitutional isomer, which appears to be promoted by relieving the steric congestion in the more crowded side of the alkene-TT2+ adduct. This argument is supported by an NCI plot analysis57,58 that allows the comparison between methyl and ethyl groups. Whereas the methyl group does not engage in any apparent interactions, the ethyl group experiences repulsive forces with the thianthrene moiety (See Section 3.2 of the Supplementary Information). Furthermore, a plausible reaction pathway was proposed on the basis of the observed excellent stereospecificity (Fig. 5c). Alkenyl TT+ species has been identified as a key intermediate from the studies by the Wickens group on their double nucleophilic functionalisations of terminal alkenes under basic conditions33. In addition, the direct transformations of isolated alkenyl TT+ into various cyclic compounds have been shown by the Ritter group31 and the Shu group59. However, such an elimination process is likely to cause a loss of stereochemical information in our system that employs internal alkenes. For the subsequent hydrohalogenation to be stereospecific, the protonation must take place both selectively from the same side with halide and rapidly prior to the C–C bond rotation, which are quite demanding requirements to meet. Instead, our syn-dihalogenations under neutral conditions are likely to proceed via two sequential SN2 displacements without involving an alkenyl TT+ species because excellent stereospecificity was observed from both alkene geometrical isomers. To support our mechanistic hypothesis regarding the reactive intermediate, a control experiment was performed (Fig. 5d). An alkenyl TT+ (14a-TT+) was prepared separately30 and subjected to the standard reaction of a different alkene substrate (14g). As expected, no dihalogenated product (15a) derived from alkenyl TT+ was observed while the syn-dichlorination of alkene proceeded uneventfully to give 15g, confirming that alkenyl TT+ is not an active species in our reaction.

Fig. 5. Mechanistic discussion.

a Examination of the substituent effect on the site-selectivity of bromochlorination. b Computational analysis on the site-selectivity of initial chlorination (wB97X-D/6-31 + G(d,p)/PCM(CH2Cl2), free energies in kcal/mol). c Probable consequence of an alkenyl TT+ intermediate and the likely pathway of our system. d Experimental validation of the reactive species.

In conclusion, we have developed a distinctive synthetic method for the syn-stereospecific alkene dihalogenations through the simultaneous activation of C–C double bonds from the same side. To realize this electrophilic vicinal double activation strategy, thianthrenium dication was successfully utilised for the concerted installation of vicinal double leaving groups on internal alkenes. Then, the iterative nucleophilic displacements with chloride and/or bromide enabled syn-additions of all possible halogen combinations with excellent diastereoselectivities. In particular, syn-dibromination and regiodivergent syn-bromochlorinations were accomplished. Upon the analysis of the experimental data, the site-selectivity appeared to be dominated by steric effect, which was supported by DFT calculation, and the exquisite stereospecificity was attributed to the absence of the competing elimination pathway under our mild reaction conditions, avoiding the formation of commonly observed alkenyl thianthrenium cation. Our work provides a mechanistically unique approach toward syn-stereospecific alkene dihalogenations, and the scope of this underdeveloped transformation has been greatly expanded.

Methods

A representative procedure for syn-dichlorination of alkenes

To a stirred solution of alkene 14a (204 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and thianthrene-S-oxide (19, 232 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added Tf2O (168 μL, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) at 0 °C. After 1 hour, a solution of n-Bu4NCl (834 mg, 3.00 mmol, 3.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (8 mL) was added. After 1 hour, H2O (10 mL) was added, and the organic layer was separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL × 3), and the combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4 (2 g), filtered through a glass frit, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was diluted with Et2O (5 mL), filtered through a pad of SiO2 (ϕ = 2.0 cm, l = 4.0 cm, Et2O, 150 mL), and concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, ϕ = 5.5 cm, l = 15 cm, EtOAc/hexanes = 1/30, Rf = 0.30) and Kugelrohr distillation (0.15 mmHg, 220 °C) to afford 15a (169 mg, 61%, >99:1 dr) as a colourless oil. Data for 15a60: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.06–8.03 (m, 2H), 7.59–7.55 (m, 1H), 7.47–7.43 (m, 2H), 4.42–4.33 (m, 2H), 4.12 (appr. pent, J = 6.6, 1H), 4.00 (ddd, J = 9.2, 6.7, 2.8, 1H), 2.26–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.98–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.65 (d, J = 6.4, 3H).

A representative procedure for syn-bromochlorination of alkenes

To a stirred solution of alkene 14a (204 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and thianthrene-S-oxide (19, 232 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added Tf2O (168 μL, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) at 0 °C. After 1 hour, the reaction mixture was cooled to −30 °C, and a solution of n-Bu4NCl (278 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (2.5 mL) was added. After 24 hours, the reaction mixture was warmed to 0 °C, and a solution of n-Bu4NBr (322 mg, 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (2.5 mL) was added. After 1 hour, H2O (10 mL) was added, and the organic layer was separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL × 3), and the combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4 (2 g), filtered through a glass frit, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was diluted with Et2O (5 mL), filtered through a pad of SiO2 (ϕ = 2.0 cm, l = 4.0 cm, Et2O, 150 mL), and concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, ϕ = 4.0 cm, l = 11 cm, CH2Cl2/hexanes = 1/3, Rf = 0.30) and Kugelrohr distillation (0.15 mmHg, 230 °C) to afford a colourless oil (220 mg, 69% (59% 17a), 99:1 dr, 90:10 rr). Data for 17a: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.06–8.03 (m, 2H), 7.59–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.47–7.43 (m, 2H), 4.39–4.36 (m, 2H), 4.23–4.16 (m, 1H), 4.08–4.04 (m, 1H), 2.32–2.23 (m, 1H), 2.14–2.05 (m, 1H), 2.00–1.88 (m, 2H), 1.84 (d, J = 6.7, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.7, 133.1, 130.3, 129.7, 128.5, 66.9, 64.2, 52.1, 33.0, 25.7, 23.6; HRMS (ESI): [M + H]+ calcd for C13H1779Br35ClO2, [C13H1781Br35ClO2 + C13H1779Br37ClO2], C13H1781Br37ClO2: 319.0095 (76.5%), 321.0073 (100.0%), 323.0050 (25.2%); found: 319.0108 (76.1%), 321.0086 (100.0%), 323.0059 (23.2%).

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Korea Toray Science Foundation (W.J.C.). We thank the Surface Physical Property Lab at GIST Central Research Facilities (GCRF) for the X-ray crystallographic analysis of 17n and 18n.

Author contributions

W.J.C. conceived the research concept. J.H.C. directed the computational study. W.J.C., H.M. and J.J. designed the synthetic strategy. H.M. and J.J. performed the synthetic work. W.J.C. and H.M. conducted the DFT calculation. W.J.C., H.M., and J.J. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to editing the manuscript and preparing the Supplementary Information.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article and its Supplementary Information, which includes experimental details, characterisation data, copies of NMR spectra for all new compounds, and DFT calculation data. The computation output files are provided as Supplementary Data 1. Crystallographic data for 17n and 18n have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2262333 and 2262334. Copies of the data can be accessed free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hyeon Moon, Jungi Jung.

Contributor Information

Jun-Ho Choi, Email: junhochoi@gist.ac.kr.

Won-jin Chung, Email: wjchung@gist.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-47942-w.

References

- 1.Roberts I, Kimball GE. The halogenation of ethylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937;59:947–948. doi: 10.1021/ja01284a507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung W-j, Vanderwal CD. Stereoselective halogenation in natural product synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:4396–4434. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cresswell AJ, Eey ST-C, Denmark SE. Catalytic, stereoselective dihalogenation of alkenes: challenges and opportunities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:15642–15682. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshimitsu T, Fukumoto N, Tanaka T. Enantiocontrolled synthesis of polychlorinated hydrocarbon motifs: a nucleophilic multiple chlorination process revisited. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:696–702. doi: 10.1021/jo802093d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denton RM, Tang X, Przeslak A. Catalysis of phosphorus(V)-mediated transformations: dichlorination reactions of epoxides under Appel conditions. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4678–4681. doi: 10.1021/ol102010h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimitsu T, Fukumoto N, Nakatani R, Kojima N, Tanaka T. Asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-hexachlorosulfolipid, a cytotoxin isolated from adriatic mussels. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:5425–5437. doi: 10.1021/jo100534d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimitsu T, Nakatani R, Kobayashi A, Tanaka T. Asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-danicalipin A. Org. Lett. 2011;13:908–911. doi: 10.1021/ol1029518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver JE, Sonnet PE. cis-Dichloroalkanes from epoxides: cis-1,2-dichlorocyclohexane. Org. Synth. 1978;58:64. doi: 10.15227/orgsyn.058.0064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilewski C, Geisser RW, Ebert M-O, Carreira EM. Conformational and configurational analysis in the study and synthesis of chlorinated natural products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15866–15876. doi: 10.1021/ja906461h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedke DK, et al. Relative stereochemistry determination and synthesis of the major chlorosulfolipid from Ochromonas danica. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7570–7572. doi: 10.1021/ja902138w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedke DK, Shibuya GM, Pereira AR, Gerwick WH, Vanderwal CD. A concise enantioselective synthesis of the chlorosulfolipid malhamensilipin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2542–2543. doi: 10.1021/ja910809c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung W-j, Carlson, J S, Bedke DK, Vanderwal CD. A Synthesis of the chlorosulfolipid mytilipin A via a longest linear sequence of seven steps. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:10052–10055. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung W-j, Carlson, J S, Vanderwal CD. General approach to the synthesis of the chlorosulfolipids danicalipin A, mytilipin A, and malhamensilipin A in enantioenriched form. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:2226–2241. doi: 10.1021/jo5000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung W-j, Vanderwal CD. Approaches to the chemical synthesis of the chlorosulfolipids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:718–728. doi: 10.1021/ar400246w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilewski C, Geisser RW, Carreira EM. Total synthesis of a chlorosulpholipid cytotoxin associated with seafood poisoning. Nature. 2009;457:573–574. doi: 10.1038/nature07734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilewski C, et al. Synthesis of undecachlorosulfolipid A: re-evaluation of the nominal structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7940–7943. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sondermann P, Carreira EM. Stereochemical revision, total synthesis, and solution state conformation of the complex chlorosulfolipid mytilipin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:10510–10519. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b05013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolaou KC, Simmons NL, Ying Y, Heretsch PM, Chen JS. Enantioselective dichlorination of allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8134–8137. doi: 10.1021/ja202555m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu DX, Shibuya GM, Burns NZ. Catalytic enantioselective dibromination of allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12960–12963. doi: 10.1021/ja4083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soltanzadeh B, et al. Highly regio- and enantioselective vicinal dihalogenation of allyl amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:2132–2135. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wedek V, Van Lommel R, Daniliuc CG, De Proft F, Hennecke U. Organocatalytic, enantioselective dichlorination of unfunctionalized alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:9239–9243. doi: 10.1002/anie.201901777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu DX, Seidl FJ, Bucher C, Burns NZ. Catalytic chemo-, regio-, and enantioselective bromochlorination of allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3795–3798. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S, et al. Urea group-directed organocatalytic asymmetric versatile dihalogenation of alkenes and alkynes. Nat. Catal. 2021;4:692–702. doi: 10.1038/s41929-021-00660-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lubaev AE, Rathnayake MD, Eze F, Bayeh-Romero L. Catalytic chemo-, regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective bromochlorination of unsaturated systems enabled by Lewis base-controlled chloride release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:13294–13301. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c04588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, et al. Enantioselective anti-dihalogenation of electron-deficient olefin: a triplet halo-radical pylon intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145:4808–4818. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cresswell AJ, Eey ST-C, Denmark SE. Catalytic, stereospecific syn-dichlorination of alkenes. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:146–152. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert BB, Eey ST-C, Ryabchuk P, Garry O, Denmark SE. Organoselenium-catalyzed enantioselective syn-dichlorination of unbiased alkenes. Tetrahedron. 2019;75:4086–4098. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2019.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banik SM, Medley JW, Jacobsen EN. Catalytic, diastereoselective 1,2-difluorination of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5000–5003. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinfeld G, Lozan V, Kersting B. cis-Bromination of encapsulated alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:2261–2263. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Li J, Plutschack MB, Berger F, Ritter T. Regio- and stereoselective thianthrenation of olefins to access versatile alkenyl electrophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:5616–5620. doi: 10.1002/anie.201914215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juliá F, Yan J, Paulus F, Ritter T. Vinyl thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate: a practical and versatile vinylating reagent made from ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:12992–12998. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holst DE, Wang DJ, Kim MJ, Guzei IA, Wickens ZK. Aziridine synthesis by coupling amines and alkenes via an electrogenerated dication. Nature. 2021;596:74–79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim MJ, et al. Diastereoselective synthesis of cyclopropanes from carbon pronucleophiles and alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202303032. doi: 10.1002/anie.202303032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holst DE, Dorval C, Winter CK, Guzei IA, Wickens ZK. Regiospecific alkene aminofunctionalization via an electrogenerated dielectrophile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145:8299–8307. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M, Targos K, Holst DE, Wang DJ, Wickens ZK. Alkene thianthrenation unlocks diverse cation synthons: recent progress and new opportunities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024;63:e202314904. doi: 10.1002/anie.202314904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson NM, Ward AD. The preparation and some chemistry of 2,2-dimethyl-1,2-dihydroquinolines. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2004.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berger F, et al. Site-selective and versatile aromatic C−H functionalization by thianthrenation. Nature. 2019;567:223–228. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engl PS, et al. C–N cross-couplings for site-selective late-stage diversification via aryl sulfonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13346–13351. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sang R, et al. Site-selective C−H oxygenation via aryl sulfonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:16161–16166. doi: 10.1002/anie.201908718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, et al. Photoredox catalysis with aryl sulfonium salts enables site-selective late-stage fluorination. Nat. Chem. 2020;12:56–62. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez EM, Karl T, Berger F, Torkowski L, Ritter T. Late-stage heteroarylation of hetero(aryl)sulfonium salts activated by α-amino alkyl radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:13609–13613. doi: 10.1002/anie.202103085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lansbergen B, Granatino P, Ritter T. Site-selective C–H alkylation of complex arenes by a two-step aryl thianthrenation-reductive alkylation sequence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:7909–7914. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c03459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braddock DC, et al. The generation and trapping of enantiopure bromonium ions. Chem. Commun. 2009;7:1082–1084. doi: 10.1039/b816914d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denmark SE, Burk MT, Hoover AJ. On the absolute configurational stability of bromonium and chloronium Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1232–1233. doi: 10.1021/ja909965h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlama T, et al. Total synthesis of (±)-halomon by a Johnson–Claisen rearrangement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2085–2087. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<2085::AID-ANIE2085>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morimoto Y, Okita T, Takaishi M, Tanaka T. Total synthesis and determination of the absolute configuration of (+)-intricatetraol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1132–1135. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burckle AJ, Gál B, Seidl FJ, Vasilev VH, Burns NZ. Enantiospecific solvolytic functionalization of bromochlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:13562–13569. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b07792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Umemura K, Matsuyama H, Kamigata N. Alkylation of several nucleophiles with alkylsulfonium salts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1990;63:2593–2600. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.63.2593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt MW, et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. doi: 10.1002/jcc.540141112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon, M. S. & Schmidt, M. W. Advances in electronic structure theory: Gamess a decade later (Elsevier, 2005).

- 51.Barca, G. M. J. et al. Recent developments in the general atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 154102 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Chai J-D, Head-Gordon M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008;10:6615–6620. doi: 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimme S. Accurate description of van der Waals complexes by density functional theory including empirical corrections. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1463–1473. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miertuš S, Scrocco E, Tomasi J. Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilizaion of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem. Phys. 1981;55:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pascual-Ahuir JL, Silla E, Tuñón I. GEPOL: An improved description of molecular surfaces. III. A new algorithm for the computation of a solvent-excluding surface. J. Comput. Chem. 1994;15:1127–1138. doi: 10.1002/jcc.540151009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barone V, Cossi M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:1995–2001. doi: 10.1021/jp9716997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson ER, et al. Revealing noncovalent interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6498–6506. doi: 10.1021/ja100936w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Contreras-García J, et al. NCIPLOT: A program for plotting noncovalent interaction regions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:625–632. doi: 10.1021/ct100641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu MS, Du HW, Cui JF, Shu W. Intermolecular metal-free cyclopropanation and aziridination of alkenes with XH2 (X = N, C) by thianthrenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202209929. doi: 10.1002/anie.202209929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sarie JC, Neufeld J, Daniliuc CG, Gilmour R. Catalytic vicinal dichlorination of unactivated alkenes. ACS Catal. 2019;9:7232–7237. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b02313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article and its Supplementary Information, which includes experimental details, characterisation data, copies of NMR spectra for all new compounds, and DFT calculation data. The computation output files are provided as Supplementary Data 1. Crystallographic data for 17n and 18n have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2262333 and 2262334. Copies of the data can be accessed free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.