Abstract

Background

In multiple sclerosis (MS), disturbance of the plasminogen activation system (PAS) and blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption are physiopathological processes that might lead to an abnormal fibrin(ogen) extravasation into the parenchyma. Fibrin(ogen) deposits, usually degraded by the PAS, promote an autoimmune response and subsequent demyelination. However, the PAS disruption is not well understood and not fully characterized in this disorder.

Methods

Here, we characterized the expression of PAS actors during different stages of two mouse models of MS (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis—EAE), in the central nervous system (CNS) by quantitative RT-PCR, immunohistofluorescence and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). Thanks to constitutive PAI-1 knockout mice (PAI-1 KO) and an immunotherapy using a blocking PAI-1 antibody, we evaluated the role of PAI-1 in EAE models and its impact on physiopathological processes such as fibrin(ogen) deposits, lymphocyte infiltration and demyelination.

Results

We report a striking overexpression of PAI-1 in reactive astrocytes during symptomatic phases, in two EAE mouse models of MS. This increase is concomitant with lymphocyte infiltration and fibrin(ogen) deposits in CNS parenchyma. By genetic invalidation of PAI-1 in mice and immunotherapy using a blocking PAI-1 antibody, we demonstrate that abolition of PAI-1 reduces the severity of EAE and occurrence of relapses in two EAE models. These benefits are correlated with a decrease in fibrin(ogen) deposits, infiltration of T4 lymphocytes, reactive astrogliosis, demyelination and axonal damage.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that a deleterious overexpression of PAI-1 by reactive astrocytes leads to intra-parenchymal dysfibrinolysis in MS models and anti-PAI-1 strategies could be a new therapeutic perspective for MS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-022-04340-z.

Keywords: EAE, Intraparenchymal fibrinolysis, Astrocytes, PAI-1

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), characterized by infiltration of immune cells concomitant to progressive damage to myelin sheaths. These events are preceded by blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption leading to an extravasation of serum proteins, including fibrin and its precursor fibrinogen which are absent from the CNS in physiological conditions [1]. In MS and its animal model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), fibrin(ogen) deposits into the parenchyma are correlated with the occurrence of clinical signs and may lead to an exacerbation of axonal injury [1–3]. A recent study demonstrated that injection of fibrinogen into the brain parenchyma promotes an autoimmune response against myelin that recapitulates some aspects of MS [4]. Noteworthy, this pathological response is blocked by fibrin-targeting immunotherapy [4].

Activation of the coagulation cascade leads to the cleavage of inactive prothrombin into active thrombin, which forms fibrin from fibrinogen protein. Plasminogen activation system (PAS) refers to the enzymatic processes leading to fibrin degradation. This system, initially described in the vasculature, consists in the catalysis of plasminogen, an inactive zymogen, into active plasmin by tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), which is inhibited essentially by neuroserpin (NSP) and the type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1). Several other regulators of this system exist such as the protease nexin-1 (PN-1; inhibiting thrombin activity) and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI; inhibiting the binding of plasmin to fibrin). The balance between tPA and PAI-1 regulates the fibrinolysis in the vasculature. Interestingly, PAS components are also found within the CNS, where they are expressed by neurons and glial cells [5, 6]. In physiological conditions, astrocytes act as a crossroad of PAS regulation in the CNS by producing PAI-1 during inflammation [7], buffering neuron-derived tPA [8, 9], offering a surface for plasminogen activation [10] and uptaking plasminogen and plasmin through cell surface actin-mediated endocytosis [10]. In the CNS, the PAS is known to interfere with pathological mechanisms including BBB dysfunction, neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation [11]. For this reason, studies in animal models have suggested that the main components of the PAS may be involved in the physiopathology of MS [3, 12–14].

In accordance with these studies in animal models, histological studies from brain tissues of MS patients showed the presence of fibrin deposits surrounding demyelinated axons, associated with an increase in PAI-1 expression and tPA/PAI-1 complex, and resulting in a decrease in tPA activity [3]. It has also been shown that the expression of PAI-1 is more important in cortical areas containing substantial fibrinogen deposits [15]. Although the source of PAI-1 in MS brain tissues is still unclear, both intracellular and extracellular PAI-1 were observed in post-mortem biopsies of MS patients, suggesting a local expression of PAI-1 [15]. In addition, increased PAI-1 concentrations were measured in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients, and the level of plasma PAI-1 was higher in active MS compared to stable MS and was also related to neurological impairment and disability [16–18].

Taken together, these experimental and clinical data support the idea that PAI-1 activity is deleterious in MS and its animal models. Because the increase in PAI-1 activity in the parenchyma can lead in fine to a reduction of fibrinolysis and fibrin deposits (dysfibrinolysis), and given the consequences of fibrin deposits on autoimmunity and neuroinflammation, we hypothesize that PAI-1 may exert its deleterious effect by reducing intraparenchymal fibrinolysis.

Given their location and their key role in BBB function, astrocyte endfeet are particularly exposed when BBB integrity is altered [19]. Various alterations of their functions are then observed such as loss of structural role in BBB permeability, changes in polarity or redistribution of water channels [20]. However, the involvement of the astrocytic PAS system in the MS physiopathology is unknown.

In the present study, we characterized the expression of the PAS actors during the different stages of two animal models of MS (chronic MOG-induced EAE and relapsing–remitting PLP-induced EAE). We report a robust PAI-1 overexpression in perivascular reactive astrocytes during symptomatic phases of EAE models. This increase coincided in time and space with lymphocyte infiltration at disease onset. Consistent with a role of PAI-1 in EAE, we showed that disease severity was reduced in PAI-1-deficient mice. Moreover, the inhibition of PAI-1 activity by injecting a blocking antibody at the onset of relapsing–remitting EAE abolished the occurrence of relapse. Our results highlight a crucial role of reactive astrocytes in which dysregulation of PAS leads to dysfibrinolysis in CNS tissues during EAE and participates in symptom onset.

Methods

Animals/ethical statements

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the French (Decree 87/848) and European (Directive 2010/63/UE) guidelines, following recommendations of our local ethical committee (CENOMEXA; Project #10799) within the expertise of the French Ministry for university teaching, research and innovation. C57BL/6J and SJL/J mice were purchased from Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) and PAI-1-deficient mice and their wild-type littermate were bred in the Centre Universitaire de Ressources Biologiques (CURB; Center Agreement F14118001; Caen, France). All animals were maintained under standard conditions with food and water given ad libitum and acclimated to the local animal facility for at least 2 weeks before the experiments.

EAE models

Chronic EAE (MOG-induced EAE) was induced in 10-week-old male C57BL6/J mice (n = 32) and in 10-week-old male PAI-1 WT and PAI-1 KO mice (C57BL6/J genetic background; n = 28 and n = 29, respectively) immunized subcutaneously with 200 µg of recombinant myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide (MOG35–55, Cambridge Research Biochemicals, Cleveland, UK) in an emulsion mixed (volume ratio 1:1) with complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA; Difco Laboratories—Fisher Scientific, Illkrich, France) containing 800 μg of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (MBT; Difco Laboratories). The emulsion was administered to regions above the shoulder and the flanks (total of four sites; 50 μL at each injection site). Control animals (sham; n = 8) were injected with saline mixed with CFA containing 800 μg of heat-killed MBT. Relapsing–remitting EAE (PLP-induced EAE) was induced in 10-week-old female SJL/J mice (n = 110) according to the same protocol except that MOG peptide was replaced by recombinant proteolipidic protein peptide (PLP139–151; Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). Sham animals (n = 11) were injected with saline mixed with CFA containing 800 μg of heat-killed MBT. All animals (MOG- and PLP-induced EAE and sham) were additionally intraperitoneally injected with 200 ng of pertussis toxin derived from Bordetella pertussis (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France) in 200 μL of saline at the time of and at 48 h after immunization.

All animals were weighed and examined daily for clinical signs of EAE. In both EAE models, clinical scores (Sc) were recorded in a blinded manner by ascending hind limb paralysis: 0, no symptoms; 1, loss of tail tonicity; 2, partial hind limb weakness; 3, partial hind limb paralysis; 4, complete hind limb paralysis; 5, moribund or death. In PLP-induced EAE, a relapse was defined as a sustained increase (minimum duration of 2 days) of at least 0.5 in clinical score after a clinical symptom-free period of at least 2 days (remission).

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Deeply anesthetized mice (n = 5 per condition) were transcardially perfused with cold heparinized saline solution (40 mL). Total RNA was isolated from whole spinal cords, forebrains (cortex and subcortical areas) and cerebellum (separated from hindbrain) with TRI-reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, then treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion, Saint Aubin, France) to avoid DNA contamination and finally quantified by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Total RNA was reverse-transcribed by using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma) with the following cycle conditions: 20 °C (10 min); 37 °C (50 min); 85 °C (10 min). The cDNA products were then stored at − 20 °C until their use.

Quantitative PCR

RT-qPCR was performed from 1:20 diluted cDNA in iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-rad, Marnes La Coquette, France) containing 200 nM of each primer. Based on mRNA coding sequences (www.ensembl.org), mouse specific primers (Table 1) were designed by using the Primer3Plus software (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi). Samples were run in triplicate on the CFX96 Real-Time system c1000 thermal cycler (Bio-rad), with the following cycle conditions: 95 °C (3 min); [95 °C (2 s), 60 °C (20 s)] × 40; 70 °C (30 s).

Table 1.

Mouse qPCR primer sequences

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Plasminogen activation system | ||

| Plat (tPA) | AGGCAACCAAGACCTCCAC | GTGTAGACCCCAGGCACATC |

| Serpine1 (PAI-1) | AGTCTTTCCGACCAAGAGCA | GACAAAGGCTGTGGAGGAAG |

| Serpini1 (Neuroserpin) | GAGGGTCTGAAAGGTGGTGA | GGAGTTAGCCACAGCCACAT |

| Plg (Plasminogen) | GCTGCCTGTGATTGAGAACA | CTCGAAGCAAACCAGAGGTC |

| Cpb2 (TAFI) | CTTCTGAGGCACGTGGATTT | CGGTTGTTCTTGTGAGCAGA |

| Serpine2 (PN-1) | CCCTACCATGGTGAGAGCAT | GAGGGATGATGGCAGACAGT |

| F2 (Pro-thrombin) | CAGCTATGAGGAGGCCTTTG | TCACACCCAGATCCATAGCA |

| Serpinf2 (α2 anti-plasmin) | GCTGCCTAAACTCCATCTGC | TCAGAGATCCCACGAAGGTC |

| Housekeeping | ||

| Ppib | CAGCAAGTTCCATCGTGTCA | GATGCTCTTTCCTCCTGTGC |

| Rpl13a | TACGCTGTGAAGGCATCAAC | GGGAGGGGTTGGTATTCATC |

| Hmbs | GAAATCATTGCTATGTCCACCA | GGGTTTTCTAGCTCCTTGGTAA |

| Hprt | CTTTGCTGACCTGCTGGATT | TATGTCCCCCGTTGACTGAT |

qPCR analysis

Data analysis was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, Cq values were obtained from the Bio-rad CFX manager software (Bio-rad). Relative gene expression values (starting quantity) were calculated with the Bio-rad CFX manager software and corrected with each efficiency (E) inferred from fivefold standard dilution series.

GeNorm algorithm, associated with QBase + ™ software (Biogazelle, Zwijnaarde, Belgium), was used to normalize gene of interest to reference genes. According to the V and M GeNorm values, the two best reference genes specific for each organ and model were selected with the lowest pairwise variability (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of selected housekeeping genes for each structure in EAE models

| EAE model and structure | Housekeeping genes | |

|---|---|---|

| MOG-EAE | ||

| Forebrain | Ppib | Rpl13a |

| Cerebellum | Hmbs | Hprt |

| Spinal cord | Rpl13a | Ppib |

| PLP-EAE | ||

| Forebrain | Rpl13a | Hmbs |

| Cerebellum | Rpl13a | Hmbs |

| Spinal cord | Ppib | Rpl13a |

Immunohistochemistry

Deeply anesthetized mice (n = 3 per condition) were transcardially perfused with cold heparinized saline solution (40 mL). Spinal cords were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (PB; 24 h; 4 °C) and cryoprotected (sucrose 20% in PBS; 24 h; 4 °C) before freezing in Cryomatrix (Thermo Scientific–Fisher Scientific). Transverse sections (10 µm) were obtained using a cryostat (Leica, CM3050S, Wetzlar, Germany), collected on poly-lysine slides and stored at − 80 °C until processing. Sections were washed three times in PBS–azide (0.0125%) at room temperature (RT) and then co-incubated in PBS–Triton 100X (0.25%) overnight with the appropriate antibodies at RT. The following antibodies were used: anti-PAI-1 (1:500, ab28207, Abcam), anti-fibrinogen (1:10,000, purified Serum from sheep immunized with fibrinogen, gift by Dr Angles-Cano), anti-CD4 (1:25; 14-0042-82, eBioscience, Fisher Scientific), anti-Ly-6G (1:500, 60031, Stemcell, Grenoble, France), anti-CD68 (1:800, ab53444, Abcam), anti-Iba-1 (1:1000, ab5076, Abcam), anti-GFAP (1:1000, ab4647, Abcam), anti-collagen type IV (1:1500, 1340, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA), anti-C3 (complement 3 protein; 1:500, A0063, DAKO, Santa Clara, CA, USA), anti-MBP (1:800, ab40390, Abcam), and anti-SMI-32 (1:1000; ab24570, Abcam). After three rinses in PBS, primary antibodies were revealed using adapted secondary antibodies linked to FITC, Cy3 or Cy5 (1:800, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) diluted in PBS–Triton 100X (0.25%) at RT for 1 h 30 min. Some control experiments were conducted: (1) omission of the primary antibodies was done for every immunohistochemistry experiment. No immunostaining was observed revealing that the secondary antibodies bound specifically to their primary antibody; (2) immunohistochemistry against PAI-1 was performed on EAE-induced PAI-WT and KO brain tissues. No PAI-1 immunoreactivity was observed in PAI-1 KO animals (data not shown). Washed sections were coverslipped with antifade medium containing DAPI and images were digitally captured using a Leica DMI6000 microscope coupled with Hamamatsu Orca Flash 4.0 camera (Iwata, Japan) and visualized with Metamorph 7.8.13.0 software or a confocal microscope (SP5, Leica) using the LAS-AF software (Leica). Images were processed using ImageJ 1.52f software (NIH). All analyses were performed blinded to the experimental data.

Cell counting and immunofluorescence quantification

All quantitative analyses were performed in the four main spinal cord regions (cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar) and three sections from each region were analyzed for each animal (3 animals per condition). The spinal cord regions were determined using the mouse spinal cord atlas [22]. For some analyses (when the spinal cord region is not specified), the four spinal cord regions were pooled.

The total number of CD4-positive cells was counted on mosaic images of whole spinal cord sections. The white matter area of each section was measured, and the number of positive cells was expressed per mm2 of spinal cord white matter tissue.

For PAI-1, fibrinogen and MBP immunofluorescence quantification, a Yen threshold was applied on all quantified images. Positive staining area was measured and expressed as a percentage of white matter area.

For GFAP quantifications, two measures were obtained (surface of immunoreactivity and intensity of immunoreactivity). The same threshold was applied on all images for both quantifications. For the surface of positive immunoreactivity, the surface of positive staining was measured and expressed as a percentage of total spinal cord area. For intensity of immunoreactivity, we measured the area of integrated intensity and the mean gray values in positive cells and negative cells (to obtain the background). We calculated the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF as follows: CTCF = integrated density – (area of selected cell × mean fluorescence of background readings).

For C3 quantification, the same threshold was applied on all images and the C3 CTCF was quantified in the GFAP-positive area.

For SMI32 quantification, the same threshold was applied on all images. The surface of positive staining was measured and expressed as a percentage of spinal cord white matter area.

P-selectin molecular MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

P-selectin molecular MRI was performed as previously described [23]. Briefly, purified anti-mouse P-selectin antibodies (40 µg, AF737; R&D Systems) were covalently conjugated to 1 mg of micro-sized particles of iron oxide (MPIO; 1.08 µm diameter) with p-toluenesulfonyl reactive surface groups (Invitrogen) in borate buffer (pH 9.5) by a 48 h incubation at 37 °C. MPIO coated with P-selectin antibodies (P-sel MPIOs) were then washed in PBS containing 0.5% BSA at 4 °C and incubated for 24 h at RT. P-sel MPIOs were rinsed in PBS (0.1% BSA) and sonicated at low intensity for 60 s to disperse MPIOs aggregates. P-sel MPIOs were stored at 4 °C in PBS under constant agitation to prevent settling and aggregate formation. Mice received intravenous injection of 1 mg/kg (equivalent Fe) of P-sel MPIOs, and imaging was performed 10 min after MPIOs administration. MRI experiment was carried out on a Pharmascan 7 T/12 cm system using surface coils (Brucker). Mice were deeply anaesthetized with isoflurane (induction 5%, maintenance to ensure immobility during MRI 2% in 70/30% NO2/O2). MPIOs were visualized in hypo-signal on a 3D respiration-gated T2*-weighted gradient echo imaging with flow compensation (GEFC; spatial resolution of 150 µm × 75 µm × 75 µm interpolated to an isotropic resolution of 75 µm) with TE: 8.6 ms; TR: 200 ms and a flip angle of 25° (acquisition time: 10 min). The mice were then affiliated to “P-selectin positive” and “P-selectin negative” groups by careful examination of MRI images by an experienced examiner (n = 3 per group). The presence of P-selectin signal was confirmed by measurement of signal void [23]. After MRI examination, mice were transcardially perfused with cold heparinized saline solution (40 mL). Spinal cords were collected and submitted to immunohistochemistry.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was performed on fresh frozen brain sections (n = 3 per group), post-fixed with 4% PFA/PBS during 15 min using the RNAscope® Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 and specific probes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc., Newark, CA, USA). Hybridization of a probe against the Bacillus subtilis dihydrodipicolinate reductase (dapB) gene was used as negative control. After the FISH procedure, GFAP was detected by immunofluorescence. Three independent experiments were performed and imaged with Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems), visualized with LAS-AF software. For FISH quantification, the same threshold was applied on all images. Positive staining was measured and expressed as a percentage of total spinal cord area.

Intracisternal injection

At the day of the symptom onset, PLP-induced EAE animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (5%) in 70%/30% NO2/O2 and maintained with 2.5% isoflurane in 70%/30% NO2/O2. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C with a rectal temperature probe and homoeothermic heating pad. One µl of anti-PAI-1 (MA-MP6H6 provided by Dr. Declerck; n = 29) or IgG isotype (with any known specificity; ab37355, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; n = 18) antibodies were administered (Antibodies concentration: 4.26 mg/mL diluted in saline) into the cisterna magna using a pulled glass micropipette as previously described [20]. The micropipette was left in place for one additional minute and then the wound was closed.

Statistics

All analyses were performed in a blinded manner. Results are represented on graphs as mean ± S.E.M. Data and statistical processing were achieved with GraphPad Prism 8 software. Statistical significance across groups defined by one factor was performed using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a false discovery rate (FDR) as post hoc test. Multiple comparisons were statistically evaluated by a two-way ANOVA with FDR post hoc test. Survival, incidence and stratification curves were analyzed with Mantel–Cox test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Dysregulation of PAS results in reduction of fibrinolysis capacity in EAE

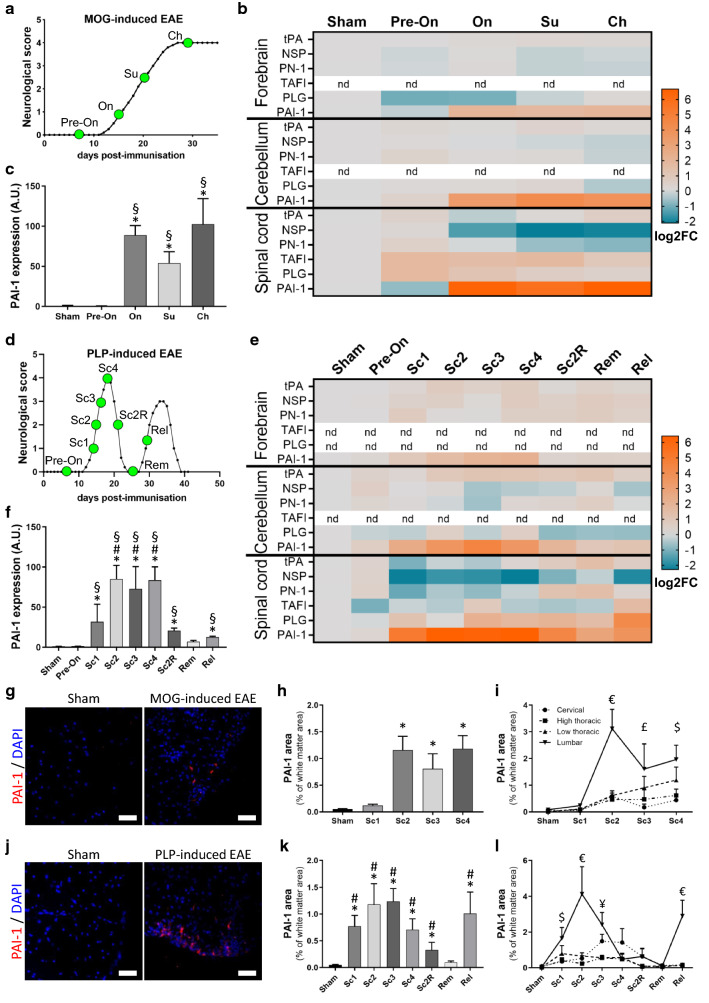

We first assessed by qPCR the expression of the different actors of the PAS in the forebrain, cerebellum, and spinal cord of mice at typical stages of MOG-induced EAE (pre-onset, symptom onset, surge, and chronic stage; Fig. 1a). Most of the studied genes, including tPA, NSP, PN-1, TAFI and plasminogen (PLG), showed slight modifications of expression in the different regions (Fig. 1b; Additional file 1: Fig. S1). In contrast, we observed a dramatic upregulation (up to 70-fold) of PAI-1 mRNA in the spinal cord at all symptomatic stages (Fig. 1b, c). This upregulation was also observed, although with a lower intensity, in the cerebellum and forebrain (Fig. 1b and Additional file 1: Fig. S1k–l).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of plasminogen activation system expression reveals a major PAI-1 increase during the EAE course. a Average clinical score evolution in MOG-induced EAE. CNS tissues were harvested from MOG-induced EAE mice at different time points of disease course represented by green dots: pre-onset (Pre-On), onset (On), surge (Su), chronic (Ch). b Heatmap (log2FC) showing expression of PAS genes in the forebrain, cerebellum and spinal cord during the course of MOG-induced EAE. c PAI-1 expression (RT-qPCR) in the spinal cord during the course of MOG-induced EAE. d Average clinical score evolution in PLP-induced EAE. CNS tissues were harvested at different time points represented by green dots: score = Sc, score 2 remitting (Sc2R), remission (Rem) and relapse (Rel). e Heatmap (log2FC) of PAS genes expression in the forebrain, cerebellum and spinal cord during the course of PLP-induced EAE. f PAI-1 expression (RT-qPCR) in the spinal cord during the course of PLP-induced EAE. g Representative images of PAI-1 immunostaining (red) in the lumbar region of white matter spinal cord from sham and symptomatic MOG-induced EAE mice (DAPI: blue). h, i Quantification of PAI-1 positive area in the total spinal cord as percentage of white matter area (h) and in the cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic, lumbar sections (i) from sham and MOG-induced EAE animals. j Representative images of PAI-1 immunostaining (red) in the lumbar region of white matter spinal cord from sham and symptomatic PLP-induced EAE mice (DAPI: blue). k, l Quantification of PAI-1-positive area in the total spinal cord as percentage of white matter area (k) and in the cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic, lumbar sections (l) from sham and PLP-induced EAE animals. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 5 or n = 3 per condition (for RT-qPCR or for immunohistochemistry, respectively). c, f, h, k Kruskal–Wallis test followed by FDR post hoc test with *, §, # indicating significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to sham, Pre-On and Rem, respectively. i, l Two-way ANOVA test followed by FDR post hoc test with € indicating significant difference (p < 0.05) between the lumbar and all other levels; $ between the lumbar and cervical/high thoracic; ¥ between the lumbar and high/low thoracic; £ between the lumbar and cervical. tPA tissue-type plasminogen activator, NSP neuroserpin, PN-1 protease-nexin 1, TAFI thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, PLG plasminogen, PAI-1 type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor

Next, we addressed whether similar changes were observed in a relapsing–remitting context. For this, we assessed the expression of the same genes at typical stages of PLP-induced EAE (pre-onset; clinical scores 1, 2, 3, 4; remitting score 2, complete remission and relapse; Fig. 1d). The results corroborate the above observations with slight modifications of most of the studied genes (Fig. 1e; Additional file 2: Fig. S2) and a dramatic (up to 80-fold) increase in PAI-1 mRNA at symptomatic stages in the spinal cord (Fig. 1f) and, with lesser intensity, in the forebrain and cerebellum (Fig. 1e and Additional file 2: Fig. S2k–l). Interestingly, the expression of PAI-1 followed the relapsing–remitting course of EAE, with a drop during remitting phase, a return to basal levels at complete remission and a second raise at the onset of relapse (Fig. 1f).

Noteworthy, the expression of tPA, the key protease in the PAS system, showed only slight modifications at the mRNA levels in the different conditions (Fig. 1b,e; Additional file 1: Fig. S1a–c and Additional file 2: Fig. S2a–c). In addition, prothrombin (the precursor of thrombin) and α2-antiplasmin (an inhibitor of plasmin) have been studied, but their expression is below the detection threshold at all phases of the two EAE models (data not shown).

Because the spinal cord is, on the one hand, the most affected area in both EAE models [20] and, on the other hand, the region where PAI-1 overexpression is the strongest, we focused on this region for the following parts of the study.

We confirmed that the transcriptional regulation of PAI-1 in MOG-induced EAE is followed by an increase in PAI-1 protein, detected by immunohistofluorescence. Although PAI-1 was hardly found in sham animals, spots of PAI-1 expression were observed within the spinal cord of symptomatic animals (Fig. 1g and corresponding quantification, Fig. 1h). Furthermore, PAI-1 expression followed the typical caudo-rostral progression over time, in relation to clinical score of the disease (Fig. 1i; Additional file 3: Fig. S3). Indeed, at the symptom onset, PAI-1 immunoreactivity is only detected in caudal regions (lumbar then low thoracic) and is almost absent in rostral ones (high thoracic and cervical). With the increase of clinical score, PAI-1 immunoreactivity appeared also in the rostral zones of spinal cord. Similar spatiotemporal dissemination was observed in the PLP-induced EAE model (Fig. 1j–l; Additional file 4: Fig. S4). PAI-1 immunofluorescence was more extended in caudal regions of the spinal cord during active phases of the disease (symptom onset and second relapse) compared to rostral ones, while PAI-1 immunoreactivity area was larger at higher score in rostral areas compared to caudal ones. Noteworthy, PAI-1 immunofluorescence dropped during remission and increased again in the lumbar region at the beginning of relapse (Fig. 1l; Additional file 4: Fig. S4).

In summary, the slight modifications of tPA, PLG, most of the serpins, and the dramatic upregulation of PAI-1 argue for a decrease in fibrinolytic capacity during symptomatic stages of the two EAE models.

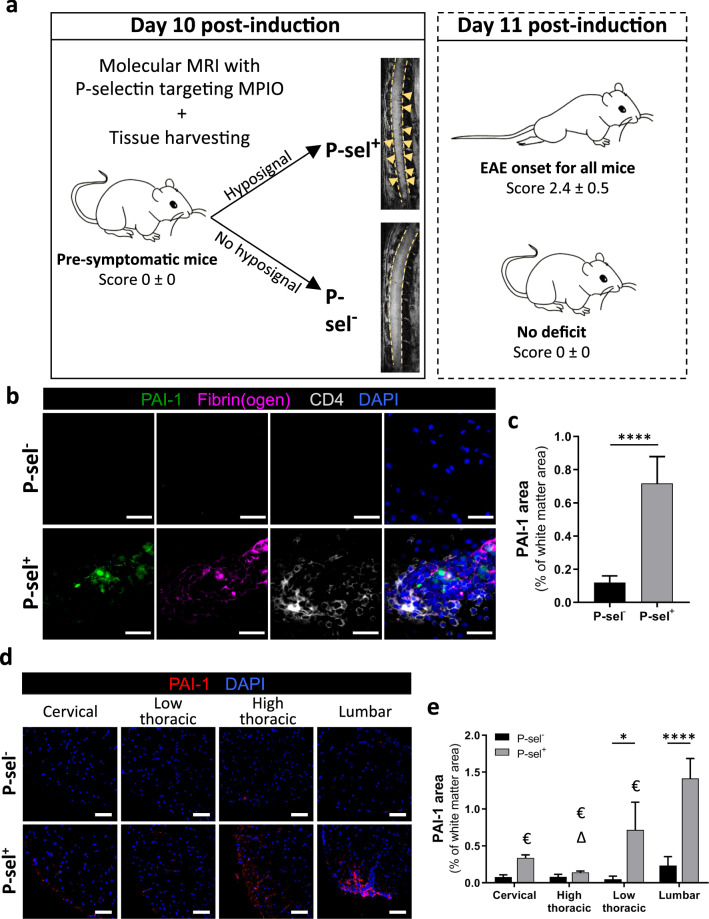

PAI-1 expression is detected at the earliest events of EAE

To foresee a causal role for PAI-1 overexpression in symptom onset, we next focused on this expression at presymptomatic stages. We previously described an MRI method based on molecular imaging of P-selectin that proved efficiency in predicting symptom onset in EAE animals within a delay of 24 h [23]. By using this method, we were able, at the earliest stage of the disease to select presymptomatic P-selectin-positive animals (P-sel+) and to compare them with non-presymptomatic animals (P-selectin negative, P-sel−; Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

PAI-1 is already detected at the earliest events of EAE onset. a Experimental design of the discrimination by molecular MRI (MPIO-anti P-selectin) at day 10 post-induction of pre-symptomatic (P-sel+) and non-pre-symptomatic (P-sel−) EAE animals. b Representative images of PAI-1 (red), fibrin(ogen) (cyan) and CD4 (T4 lymphocytes, green) immunostaining on the lumbar region of spinal white matter from P-sel− and P-sel+ EAE mice (DAPI: blue). c Quantification of PAI-1-positive area in the total spinal cord as percentage of white matter area from P-sel− and P-sel+ EAE mice. d, e Representative images (d) of PAI-1 (red) immunostaining and its relative quantification (e) on the lumbar, low thoracic, high thoracic and cervical regions of spinal white matter from P-sel− and P-sel+ EAE mice (DAPI: blue). Data are represented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with c Mann–Whitney U test and a two-way ANOVA. Two-way ANOVA test followed by FDR post hoc test with € indicating significant difference (p < 0.05) between the lumbar and all other levels; Δ significant difference (p < 0.05) between the low thoracic and cervical/high thoracic. *p < 0.05, and ****p < 0.0001. n = 3 per condition. Scale bars: 20 µm

We collected spinal cords from P-sel+ and P-sel− animals and performed immunostaining to characterize PAI-1 expression. After quantification, we observed that PAI-1 is overexpressed in P-sel+ animals compared to P-sel− animals (Fig. 2b and corresponding quantification, Fig. 2c). In P-sel+ animals, patches of PAI-1 were exclusively present in specific areas where BBB permeability was altered (indicated by the presence of fibrin(ogen) immunostaining) and where CD4+ cell infiltration took place (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, we revealed a spatial dissemination of PAI-1 in P-sel+ mice (Fig. 2d and e). In fact, PAI-1 overexpression followed a caudo-rostral progression with a higher expression in caudal spinal cord areas compared to higher regions (Fig. 2d and e). Therefore, PAI-1 is detected in the parenchyma at the time and site of early EAE events.

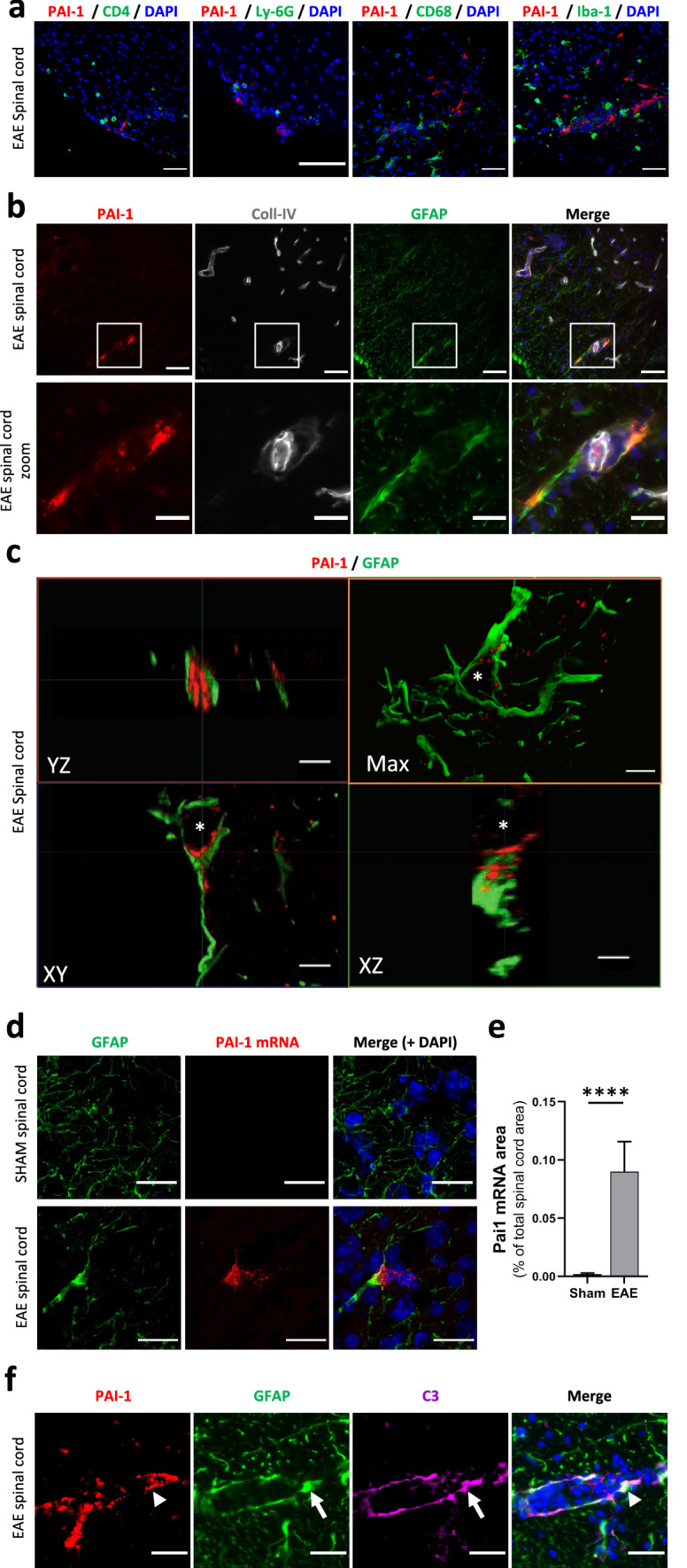

PAI-1 is expressed in reactive astrocytes

Next, we assessed the cellular origin of PAI-1 overexpression in the spinal cord of EAE animals. Although we observed PAI-1 immunostaining in regions of cellular infiltration (Fig. 2b), we did not find this serpin in inflammatory cells typically involved in the physiopathology of EAE and MS such as T4 lymphocytes (CD4+ cells), neutrophils (Ly-6G+ cells) or macrophages/microglia (CD68+ and Iba-1+cells; Fig. 3a). Rather, we detected PAI-1 immunostaining in astrocytes at the vicinity of collagen-IV blood vessels (GFAP+ cells; Fig. 3b). We confirmed that PAI-1 protein was found within astrocytes by confocal microscopy and 3D reconstruction (Fig. 3c). To confirm that the overexpression of PAI-1 results from local synthesis in astrocytes (and is not due, for instance, to its extravasation consecutive to BBB opening and its subsequent endocytosis by astrocytes), we performed fluorescent in situ hybridization. We detected PAI-1 mRNAs in GFAP-positive cells of the spinal cord of symptomatic EAE mice compared to sham animals (Fig. 3d). After quantification, we noticed that PAI-1 mRNA is overexpressed in spinal cord of EAE mice compared to sham animals (Fig. 3e). Finally, PAI-1 (arrowhead) was detected in GFAP+/C3+ reactive astrocytes (arrow) located close to cell infiltration areas (Fig. 3f), which supports an expression of this serpin in reactive astrocytes.

Fig. 3.

PAI-1 is expressed in activated astrocytes. a Representative immunostaining of PAI-1 (red) in combination with a set of inflammatory cell-type markers (green): T4 lymphocytes (CD4); neutrophils (Ly-6G); macrophages/microglia (CD68 and Iba-1) on the lumbar spinal cord from symptomatic EAE mice (DAPI: blue). b Representative immunostaining of PAI-1 (red), Coll-IV (blood vessels, grey) and GFAP (astrocytes, green) on the spinal cord from symptomatic EAE mice (DAPI: blue). c 3D reconstruction (by maximal intensity projection: max) and orthogonal sections of representative confocal imaging of PAI-1 (red) and GFAP (green) immunostaining on the lumbar spinal cord from symptomatic EAE mice (asterisk: nucleus). d, e Representative image of fluorescent in situ hybridization (d) of PAI-1 mRNA (red) and GFAP immunostaining (green) on the lumbar spinal cord from sham and symptomatic EAE mice (DAPI: blue) and its relative quantification (e) as percentage of the total spinal cord area n = 3. Data are represented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with a Mann–Whitney U test. ****p < 0.0001. f Representative immunostaining of PAI-1 (red, arrowhead), GFAP (green, arrow) and C3 (magenta, arrow) on the lumbar spinal cord from symptomatic EAE mice (DAPI: blue). Scale bars: 50 µm in a and upper b; 20 µm in lower b and d; 10 µm in c and f

Together, these data indicate that reactive astrocytes are the main source of PAI-1 within the spinal cord of EAE mice.

PAI-1 is deleterious in EAE by impairing fibrinolysis and promoting fibrin(ogen) deposits

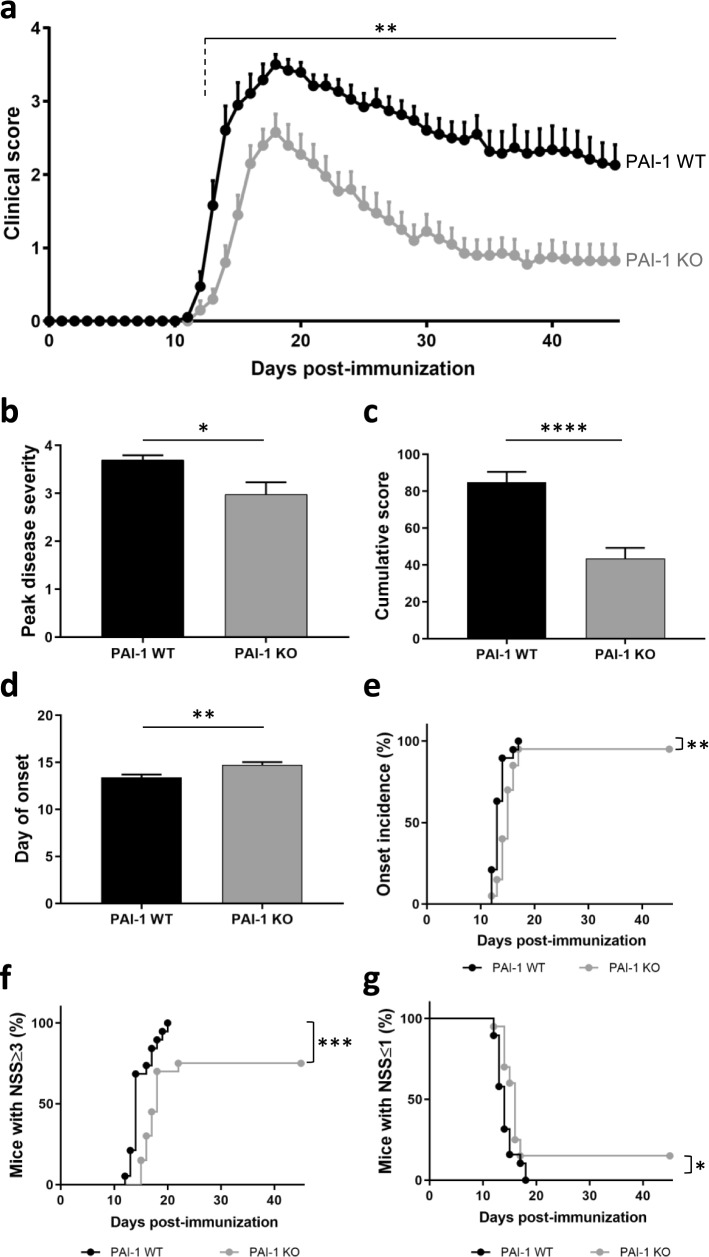

The overexpression of PAI-1 in symptomatic animals suggests a role of this protein in the physiopathology of EAE. To test the role of PAI-1 we compared the course of EAE in PAI-1 knockout mice (PAI-1 KO) and wild-type (WT) littermates (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

PAI-1-deficient mice develop less severe MOG-induced EAE. a Clinical score evolution, b peak disease severity, c cumulative score over 45 days, d day of onset, e incidence of onset, f mice with neurological severity score (NSS) ≥ 3 and g mice with NSS ≤ 1 of MOG-induced EAE in PAI-1 WT (n = 19) and PAI-1 KO (n = 20) mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with a two-way ANOVA, b-d Mann–Whitney U test and e–g log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001

PAI-1 KO mice exhibited a reduced clinical score compared to WT mice from day 13 (Fig. 4a), with reduced peak score (2.98 ± 0.26 vs. 3.69 ± 0.1; Fig. 4b), reduced cumulative score (43.6 ± 5.84 vs. 85 ± 5.43; Fig. 4c) and later day of onset (14.7 ± 0.3 vs. 13.4 ± 0.3; Fig. 4d). The incidence of disease (Fig. 4e) and the severity of symptoms were lower in PAI-1 KO mice compared to WT (Fig. 4f, g). While all WT mice displayed a clinical score equal to or greater than 3 (corresponding to partial hindlimb paralysis) from day 20, only 75% of PAI-1 KO mice had reached this score at day 22 (Fig. 4f). Conversely, we noticed that 15% of PAI-1 KO mice remained with a clinical score equal to or lower than 1 (corresponding to tail flaccidity) at day 45, while all WT mice had reached a score higher than 1 from day 18 (Fig. 4g). These results indicated that deletion of PAI-1 protects the mice from EAE and support a deleterious role of PAI-1 in MOG-induced EAE.

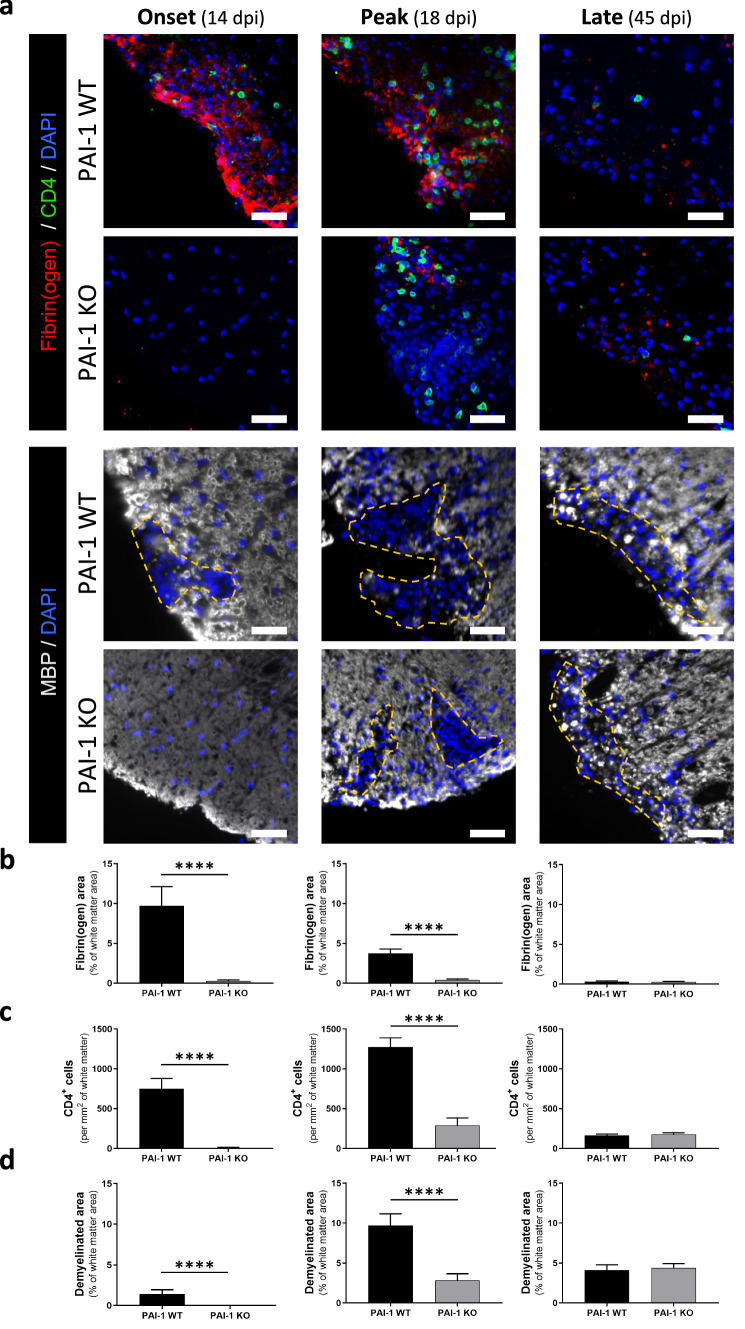

Next, we evaluated by immunohistochemistry in PAI-1 KO and WT animals the pathological signs that may be related to the reduced EAE severity in PAI-1 KO mice: fibrin(ogen) deposits, infiltration of T4 lymphocytes, demyelination, reactive astrogliosis and axonal damage, at three critical time points that are onset (14 dpi), peak of symptoms (18 dpi) and late stage (45 dpi; Figs. 5 and 6; Additional file 5: Fig. S5a–b).

Fig. 5.

PAI-1 KO mice exhibit less fibrin(ogen) deposits, CD4+ cells infiltration and demyelination at early stages of MOG-induced EAE. a Representative immunostaining of fibrin(ogen; red), CD4 (yellow) and myelin (MBP, grey) in the lumbar spinal cord from PAI-1 WT and PAI-1 KO mice at onset (14 dpi), peak (18 dpi) and late stages (45 dpi) during MOG-induced EAE, (DAPI: blue). Demyelinated areas are defined by the dashed yellow line. Corresponding quantifications of b fibrin(ogen) deposits, c CD4+ cell infiltration and d demyelination. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 per condition. Mann–Whitney U test; ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars: 50 µm

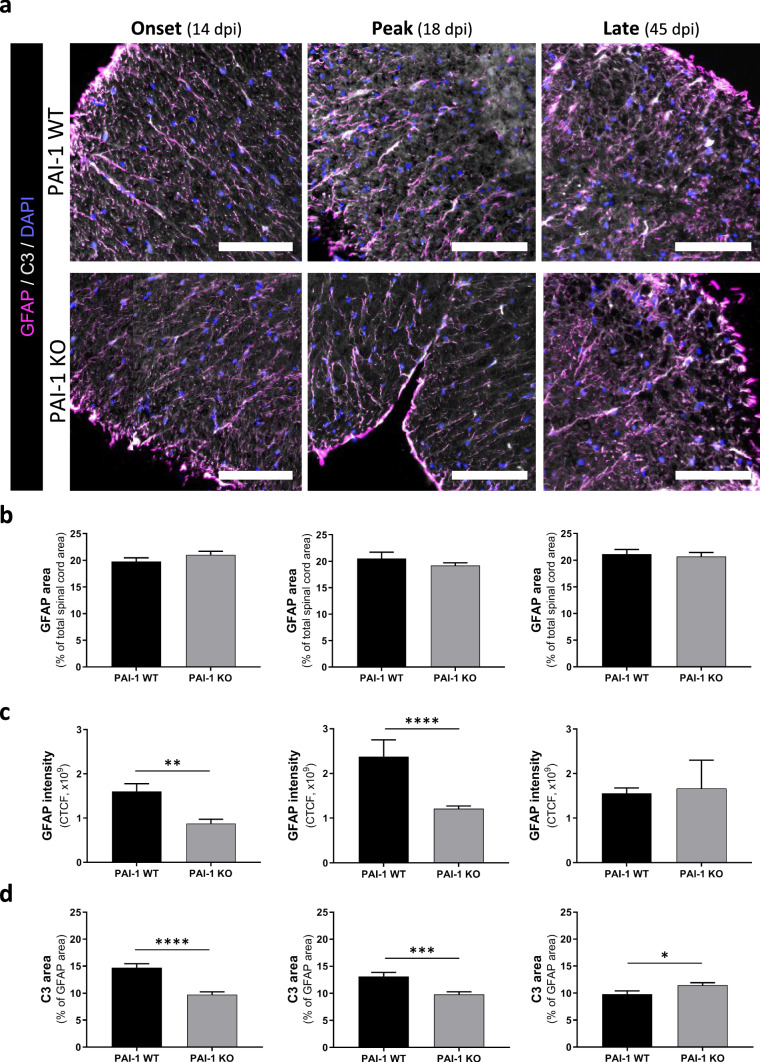

Fig. 6.

PAI-1 KO mice exhibit less reactive astrogliosis of MOG-induced EAE mice. a Representative immunostaining of GFAP (magenta) and C3 (grey) in the spinal cord from PAI-1 WT and PAI-1 KO mice at onset (14 dpi), peak (18 dpi) and late stages (45 dpi) during MOG-induced EAE (DAPI: blue). At 14, 18 and 45 dpi, the spinal cord region is, respectively, the low thoracic, lumbar and cervical area. b-d Corresponding quantifications of (b) GFAP area, (c) GFAP intensity and (d) C3 area in astrocytes (GFAP positive area). CTCF: corrected total cell fluorescence. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 per condition Mann–Whitney U test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars: 40 µm

Fibrin(ogen) deposits were present in WT mice from 14 dpi (EAE onset) and decreased along the course of EAE to become practically absent at 45 dpi (Fig. 5a and corresponding quantification, Fig. 5b). In PAI-1 KO mice, in contrast, these deposits were hardly detected at any stage (Fig. 5a, b).

Lymphocyte infiltration was prominent from day 14 in WT mice (EAE onset), peaked at 18 dpi (acute phase) and decreased at 45 dpi (Fig. 5a, c). In PAI-1 KO, T4 lymphocytes were practically absent at 14 dpi (previous to onset in PAI-1 KO animals) and, although their number increased at 18 dpi, it remained much below the values of WT mice. Finally, it remained rather stable at 45 dpi, when no difference was observed between WT and PAI-1 KO mice (Fig. 5a and corresponding quantification, Fig. 5c).

Demyelination and axonal damage paralleled the pattern of lymphocyte infiltration: apparent at 14 dpi only in WT mice, peak at 18 dpi in both genotypes though with lower intensity in PAI-1 KO and stabilization at 45 dpi, with equivalent intensity in WT and PAI-1 KO mice (Fig. 5a and corresponding quantification, Fig. 5d; Additional file 5: Fig. S5a, b).

The reactive astrogliosis was assessed by the distribution of astrocytes, their GFAP intensity and their potential immunological polarization (C3 immunoreactivity). No significant difference in GFAP immunopositive surface was detected at any EAE stages in the entire spinal cord and in both strains (Fig. 6a, b). By measuring the intensity of GFAP and the presence of C3 marker in the astrocytes (GFAP-positive cells; [24]) in PAI-1 WT and KO animals, we noticed that the reactive astrogliosis (intensity of GFAP and C3 immunoreactivity) followed the same pattern as the other pathological signs (fibrinogen deposits, infiltration of CD4+ lymphocytes and demyelination). Indeed, in WT mice, we detected an increase in GFAP immunoreactivity from 14 dpi (EAE onset) to 18 dpi (acute phase) and a decrease at 45 dpi (late). In PAI-1 KO animals, reactive astrogliosis was less important at 14 and 18 dpi compared to PAI-1 WT mice. At 45 dpi, a stabilization was detected with no more difference between WT and KO animals (Fig. 6a–c). Regarding C3 immunoreactivity, at the onset and peak of the disease, C3 was significantly more important in PAI-1 WT compared to KO animals, while at the late phase of the disease, the C3 marker was significantly more expressed in PAI-KO astrocytes (GFAP-positive cells) than in WT animals (Fig. 6a–d). Hence, we can conclude that although there is no difference in the number of GFAP positive cells (i.e., astrocytes), there is an increase in the reactive astrogliosis in PAI-WT compared to KO animals.

These data support the causal link between fibrinogen deposits, lymphocyte infiltration, reactive astrogliosis, demyelination, and axonal damage in EAE [4, 14] and suggest that, when PAI-1 action is abolished as in PAI-1 KO mice, fibrin(ogen) deposition is reduced and delayed, and this cascade of events is impaired. This may explain the lesser severity of EAE in PAI-1 KO mice (Fig. 4) and support a deleterious role of PAI-1 in this model.

Blocking PAI-1 action improves EAE symptomatology and reduces fibrinogen deposits

Considering the possible deleterious role of PAI-1 in EAE, our next objective was to assess the therapeutic potential of an intervention aimed at blocking the effects of PAI-1 in a model relevant to the most frequent clinical form of MS, the relapsing–remitting form. For that, we injected in PLP-induced EAE animals the blocking antibody MA-MP6H6 [25] directed against PAI-1. This injection was performed at the onset of symptoms, to adopt a regimen of treatment as compatible as possible with the clinical situation. Animals injected with a control isotype showed a classical course of PLP-induced EAE, with a first surge between 10 and 15 dpi, a progressive recovery between 15 and 25 dpi, a nearly complete remission between 25 and 32 dpi and a biphasic relapse between 32 dpi and the end of the experiment (45 dpi; Fig. 7a). Surprisingly, although we expected a reduction already in the first surge of the disease, the injection of anti-PAI-1 antibody did not influence it, but rather strongly reduced the occurrence of relapse in this model (Fig. 7). Indeed, although 66.7% of isotype-treated animals experienced a relapse, only 13.3% of anti-PAI-1 animals did (Fig. 7a, f).

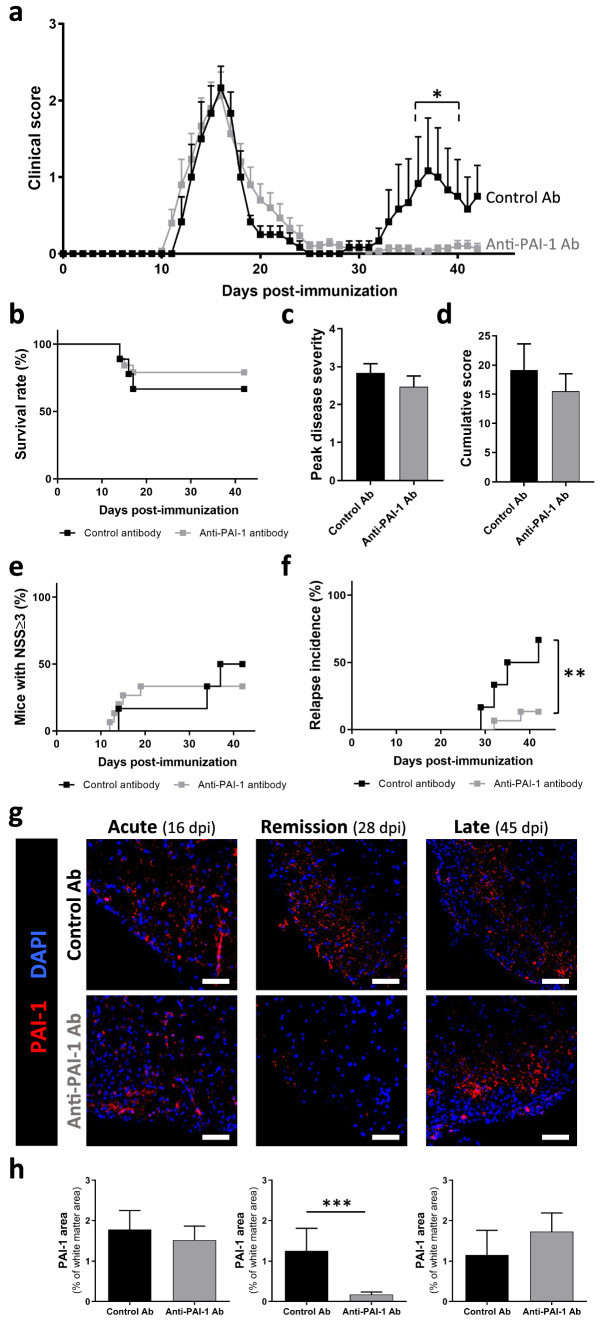

Fig. 7.

Intracisternal administration of anti-PAI-1 antibody abolish EAE relapses of PLP-induced EAE mice. a Clinical score evolution, b survival curves, c peak disease severity, d cumulative score, e incidence of mice with NSS ≥ 3 and f incidence of relapse for PLP-induced EAE animals treated with control antibody (n = 9) or anti-PAI-1 antibody (MA-MP6H6; n = 19). Antibodies were administered in the cisterna magna at the day of EAE onset. g Representative immunostaining of PAI-1 in the high thoracic spinal cord from PLP-induced EAE animals treated with control antibody or anti-PAI-1 antibody at acute (16 dpi), remission (28 dpi) and late stages (45 dpi) during PLP-induced EAE (DAPI: blue) and h the PAI-1 positive area quantification in the total spinal cord as percentage of white matter area (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with a Two-way ANOVA followed by FDR test, b, e, f log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test and c, d, h Mann–Whitney U test *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Scale bars: 20 µm

To assess the effects of injected antibodies on PAI-1 expression itself, we performed immunohistochemistry experiments in PLP-induced EAE treated with MA-MP6H6 antibody or the isotype control at different phases of the disease (Fig. 7g, h). At the acute phase of the disease (16 dpi), an increase of PAI-1 expression is observed in the whole spinal cord in both groups (isotype-, anti-PAI-1-injected mice; Fig. 7g, h, left). During remission, PAI-1 expression remained stable in isotype-injected animals, whereas in animals treated with anti-PAI-1, its expression is highly decreased (Fig. 7g, h, middle). At the late phase of the pathology, no significant difference was detected between the two groups (Fig. 7g, h, right). These results indicate the administration of anti-PAI-1 antibody decreased PAI-1 immunoreactivity in the CNS of EAE animals.

We next evaluated by immunohistochemistry in animals injected with control isotype or anti-PAI-1 antibody the pathological signs that may be related to the blockade of EAE relapse in anti-PAI-1-injected mice: fibrin(ogen) deposits, infiltration of CD4+ lymphocyte, demyelination and axonal damage, at the acute phase (16 dpi), during the remission phase (28 dpi) and late stage (45 dpi; Fig. 8; Additional file 5: Fig. S5c, d).

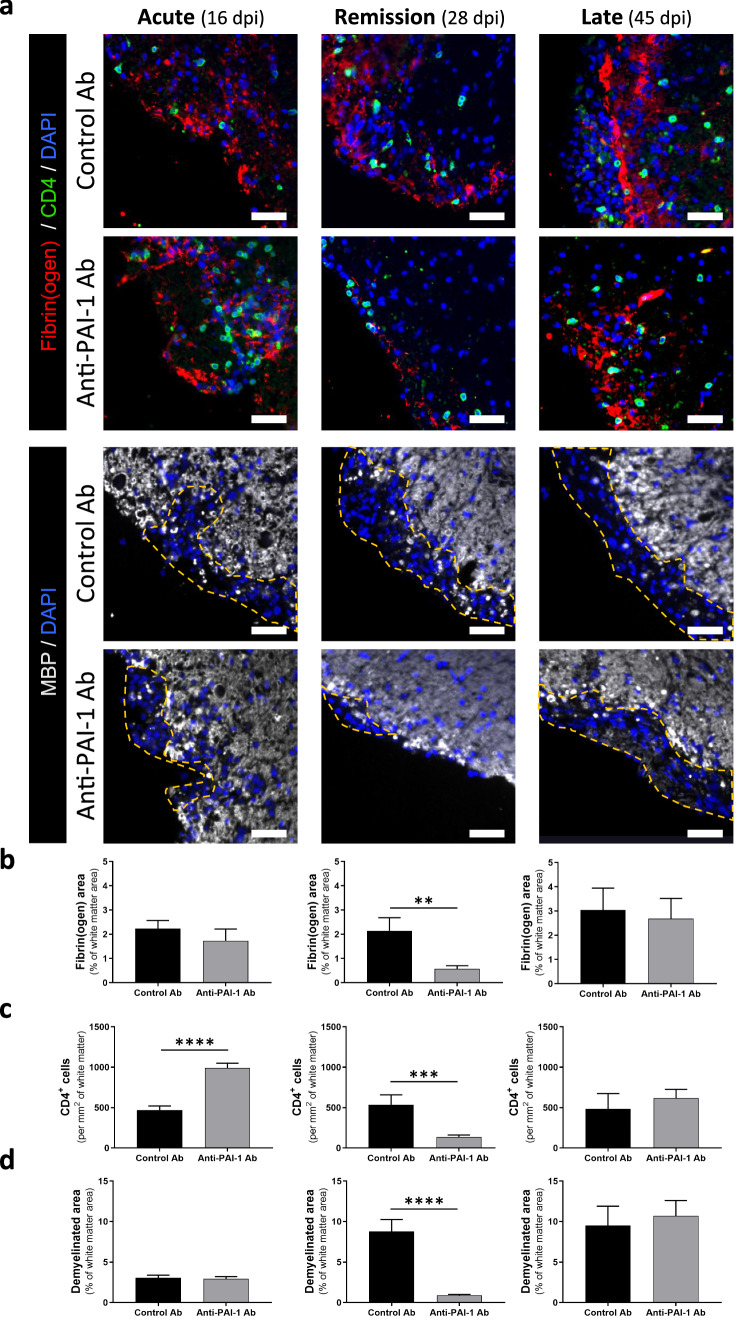

Fig. 8.

Immunotherapy targeting PAI-1 improves pathological signs of PLP-induced EAE animals. a Representative immunostaining of fibrin(ogen) (red), CD4 (yellow) and myelin (MBP, grey) in the spinal cord from control and anti-PAI-1 antibody-treated mice at acute (16 dpi), remission (28 dpi) and late stages (45 dpi) during PLP-induced EAE, (DAPI: blue). Demyelinated areas are defined by the dashed yellow line. The representative images for acute stages are from the cervical region and for remission and late stages are from the lumbar area. Corresponding quantifications of b fibrin(ogen) deposits, c CD4+ cells infiltration and d demyelination. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 per condition. Mann–Whitney U test. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Scale bars: 50 µm

We observed no reduction of pathological signs, and even an increase in the number of T4+ cells at the acute phase of disease (16 dpi) in anti-PAI-1-injected mice (Fig. 7). During remission, fibrinogen deposits and the number of CD4+ cells remained stable in isotype-injected animals, and demyelination increased (Fig. 8). In contrast, in animals treated with anti-PAI-1 antibodies, the three pathological signs decreased (Fig. 8). Finally, at late stage of the disease, no difference of fibrin(ogen) deposits, infiltration of CD4+ lymphocyte and demyelination were observed between the two groups (Fig. 8b–d). Surprisingly, no significant differences in axonal damage (SMI32 immunopositive staining) were detected between isotype and anti-PAI-1-injected mice (Additional file 5: Fig. S5c, d).

Discussion

This work reports a link between intraparenchymal fibrinolysis and neuroinflammation in EAE orchestrated by the astrocytic production of PAI-1. We propose the following sequence of events: in the early, presymptomatic phase of EAE, the increase in BBB permeability allows the extravasation of blood protein, among which fibrin(ogen). The deposition of this protein is initially impeded by the fibrinolytic cascade. This control is then gradually inhibited by the overexpression of PAI-1 in reactive astrocytes that coincides in time and space with EAE onset. This dysfibrinolysis leads to the deposition of fibrin(ogen) at sites of BBB dysfunction, reactive astrogliosis, recruitment of lymphocytes and subsequent demyelination and axonal damage [4, 14]. Accordingly, abolishing PAI-1 action by genetic invalidation or by the injection of a blocking antibody improves EAE.

Among all the members of PAS assessed by RT-qPCR in this study, PAI-1 is the most consistently and highly regulated gene in both EAE models. Moreover, we describe that PAI-1 overexpression precedes and predicts the appearance of lesions in asymptomatic animals and, after onset, progresses following a caudo-rostral gradient that parallels the one of EAE lesions. These observations support the idea that the regulation of PAS via PAI-1 is an important element of neuroinflammatory process in the chronic context of EAE and MS. This adds to previous reports in MS [15] and in other models of neurological diseases such as stroke [5], brain trauma [26], Alzheimer’s disease [27] or prion disease [28] in which PAI-1 overexpression is also observed at time and/or sites of lesions. Further experiments will be addressed to investigate PAI-1 as a peripheral biomarker in EAE. In this study, a second observation on PAS modification is the decrease of NSP in the spinal cord of EAE models. Previous studies on MS patients have shown that NSP is highly reduced in CSF and in MS lesions [3, 29]. As NSP is mainly expressed in neurons, its decrease could be due to axonal damage following inflammatory reaction [3]. A third statement of the RT-qPCR analysis is the PAI-1 mRNA increase without an up-regulation of tPA mRNA. In physiological conditions, an increase of PAI-1 generally results in an upregulation of tPA [30]. However, and consistent with our results, it has been demonstrated that in pathological conditions, PAI-1 can be raised without an increase of tPA [31]. The absence of tPA mRNA upregulation can be explained by the fact that there is only an increase of tPA protein secretion without any rise of tPA mRNA. As tPA can be stored in various vesicles such as dense core vesicles in neurons [32], this release of tPA can only be due to the secretion of stored tPA without an upregulation of its transcripts.

In MS tissues, studies have revealed an increase of PAI-1 expression in cell bodies of normal appearing and lesioned motor cortical layers without identifying the cell type [15]. Our study identified astrocytes as the main cellular source of PAI-1 overexpression in EAE. This increase in PAI-1 is consistent with previous observations in other models of neurological disorders with neuroinflammatory components [5, 33, 34]. Nevertheless, in a context of increased BBB permeability, it cannot be fully excluded that part of PAI-1 accumulated in inflamed tissues originates from the blood. Indeed, blood-derived PAI-1 has been suggested earlier to play a role in MS, after the clinical observation that elevated circulating PAI-1 levels are correlated to higher EDSS scores [18]. However, PAI-1 does not seem to systematically extravasate through impaired BBB, as we observed that zones of leaky BBB do not always show PAI-1 immunostaining (data not shown). The respective roles of blood- and astrocyte-derived PAI-1 and the investigation of PAI-1 as a peripheral biomarker in EAE should be addressed in further studies.

Interestingly, our data show that the astrocytes overexpressing PAI-1 display the subtype marker C3, which suggests that these cells are responsible for the dysfibrinolysis and its pathological consequences observed in EAE. Moreover, we observed that reactive astrogliosis (GFAP and C3 immunoreactivities) is reduced in PAI-KO compared to WT mice. These data are in accordance with previous work where C3-positive astrocytes are found in human post-mortem active MS lesions [24]. However, reactive astrocytes can display various phenotypes [35], such as a recently described profile characterized by the expression of the transcription factor c-Fos [36]. Although this novel phenotype has not been fully characterized yet, it may be an intermediate phenotype. Further studies are needed to give a thorough description of the spatiotemporal distribution and phenotypes of reactive astrocytes in EAE and MS [37, 38]. Future works may address whether these additional subtypes can be a source of PAI-1.

We describe that fibrin(ogen) deposits are associated in space and time with PAI-1 overexpression. This suggests that although fibrin(ogen) extravasates through the impaired BBB, it does not accumulate in the tissue as long as the fibrinolytic cascade is efficient (i.e., as far as PAI-1 is not overexpressed). The fibrinolytic system would thus prevent fibrin(ogen)-induced leukocyte recruitment. However, when PAI-1 is overexpressed, the fibrinolytic balance is impaired and extravasated fibrin(ogen) forms deposit in the tissue, which promotes lymphocyte infiltration, demyelination and axonal damage. Furthermore, in MS tissues, it has been shown that cortical PAI-1 is overexpressed with significant fibrinogen deposits [15]. Thus, this proposed model is supported by the present observation that leukocyte infiltration is found only in regions where BBB is impaired and PAI-1 is overexpressed.

The link between fibrin(ogen) deposits and inflammation has been described by the group of Akassoglou and resides mainly in the ability of fibrin to trigger microglia response by activating CD11b/CD18 receptor, leading to oxidative stress via activation of NADPH oxidase [39] and chemokine release [4] that drive peripheral cell recruitment. In accordance with this, we describe here that CD4+ cell infiltration occurs at sites where BBB impairment and PAI-1 overexpression occur together. These two processes concur to fibrin(ogen) accumulation in the tissue, by respectively and consecutively allowing its extravasation and its deposition. In addition to this mechanism, PAI-1 can have opposite effects on immune cells: it can promote the recruitment and the infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, while it can decrease T regulator (CD25+) lymphocyte infiltration and polarize macrophages into a M2 phenotype [40–43]. Altogether, we can hypothesize that PAI-1 influences immune cell recruitment by promoting the infiltration of pro-inflammatory immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages) and decreasing that of anti-inflammatory (T regulator lymphocytes and M2 macrophages) leading to an exacerbation of inflammatory response in MS.

The description of this deleterious effect of PAI-1 in EAE prompted us to evaluate the therapeutic efficiency of the injection of an anti-PAI-1 blocking antibody (MA-MP6H6) previously shown to effectively neutralize active PAI-1 and to restore fibrinolysis [25]. We chose to inject MA-MP6H6 at the onset of symptoms to give a more realistic consistency with the clinical situation. This therapeutic strategy did not affect the first peak of disease. Although surprising in the first place, this may be explained by the fact that PAI-1 overexpression and fibrin(ogen) deposits appear at presymptomatic stages of the disease and may thus not be efficiently targeted by a treatment applied at symptomatic stages. Accordingly, PAI-1, fibrin(ogen) deposits and CD4+ infiltration were not reduced during the first peak by MA-MP6H6 injection.

In contrast, the first relapse (second peak) was abolished by MA-MP6H6 injection. A possible explanation is that although injecting MA-MP6H6 at symptomatic onset was too late to influence the first peak, it was efficient to prevent the rebound of neuroinflammatory processes announcing relapse. In accordance with this, although PAI-1, fibrin(ogen) deposits and CD4+ cells were maintained in the spinal cord of isotype-injected mice during the remission phase, these three pathological processes were reduced in MA-MP6H6-injected animals. Interestingly, previous works in a relapsing–remitting model reported that, in contrast to wild-type mice, PAI-1 KO mice require an immune recall during the remission phase to develop a clinical relapse [13]. This is consistent with the idea that PAI-1 action in the early phases of EAE can have consequences on the relapse.

These data open further perspectives for the use of anti-PAI-1 immunotherapy in MS, in addition or as an alternative to currently developed anti-fibrin immunotherapy [39], with the common objective to inhibit the deleterious consequences of dysfibrinolysis and fibrin deposition in inflamed CNS tissues. Anti-fibrin immunotherapy has also proved efficient in models of Alzheimer’s disease in which PAI-1 overexpression has been reported. This should foster the design of future studies to evaluate the efficiency of anti-PAI-1 strategies in models of Alzheimer’s disease or other neurological diseases with neuroinflammatory components.

Conclusions

The present study shows that the PAS is dysregulated with a strong PAI-1 overexpression in reactive astrocytes during the symptomatic phases of EAE. PAI-1-deficient mice exhibit a reduced EAE severity due to a delayed and reduced fibrin(ogen) deposits, lymphocyte infiltration and demyelination. The same results were obtained when PAI-1 was neutralized thanks to a blocking antibody. These data highlight a crucial role of reactive astrocytes in which PAS dysregulation leads to dysfibrinolysis in CNS tissues during EAE and participates in symptom onset, suggesting that PAI-1 could be targeted as a new therapeutic strategy for MS.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Additional file 1: Figure S1. PAS gene expression in forebrain, cerebellum and spinal cord during the course of MOG-induced EAE. Gene expression of a-c tPA, d-f NSP, g-i PN-1, j TAFI, k, l PAI-1 and m-o PLG in a, d, g, j, m the spinal cord, b, e, h, k, n the cerebellum and c, f, i, l, o the forebrain of mice during the course of MOG-induced EAE. RT-qPCR results expressed as mean ± SEM, n=5 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: * and § indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham and Pre-On respectively, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. tPA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; NSP: Neuroserpin; PN-1: protease nexin-1; PLG: Plasminogen; TAFI: thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor; PAI-1: type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. Pre-On: pre-onset; On: onset; Su: surge; Ch: chronic as depicted in Fig. 1a. (PDF 235 KB)

Supplementary file2 Additional file 2: Figure S2.PAS gene expression in forebrain, cerebellum and spinal cord during the course of PLP-induced EAE. Gene expression of a-c tPA, d-f NSP, g-i PN-1, j TAFI, k, l PAI-1 and m, n PLG in a, d, g, j, m the spinal cord, b, e, h, k, n the cerebellum and c, f, i, l the forebrain of mice during the course of PLP-induced EAE. RT-qPCR results expressed as mean ± SEM, n=5 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: *, §, #, † indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham, Pre-On, Rem and Rel respectively, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. tPA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; NSP: Neuroserpin; PN-1: protease nexin-1; PLG: Plasminogen; TAFI: thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor; PAI-1: type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. Pre-On: pre-onset; On: onset; Sc1/2/3/4/2R: score 1/2/3/4/2 remitting; Rem: remission; Rel: relapse as depicted in Fig. 1d. (PDF 295 KB)

Supplementary file3 Additional file 3: Figure S3: PAI-1 immunostaining quantification in white matter spinal cord sections during the course of MOG-induced EAE model. a Representative PAI-1 immunostaining (red) in cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar sections of spinal cord from Sham and MOG-induced EAE mice for each stage of the disease (DAPI: blue). b Quantification of PAI-1 immunostaining coverage in cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar sections of spinal cord from Sham and MOG-induced EAE mice. Histograms show mean ± SEM, n=3 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: * indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. Sc1/2/3/4: score 1/2/3/4. Scale bars: 50µm. (PDF 496 KB)

Supplementary file4 Additional file 4: Figure S4: PAI-1 immunostaining quantification in white matter spinal cord sections during the course of PLP-induced EAE model. a Representative PAI-1 immunostaining (red) in cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar sections of spinal cord from Sham and PLP-induced EAE mice for each stage of the disease (DAPI: blue). b PAI-1 immunostaining coverage in cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar sections of spinal cord from Sham and PLP-induced EAE mice. Histograms show mean ± SEM, n=3 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: *, §, #, † indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham, Pre-on, Rem and Rel respectively, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. Sc1/2/3/4/2R: score1/2/3/4/2 remitting; Rem: remission; Rel: relapse. Scale bars: 50µm. (PDF 672 KB)

Supplementary file5 Additional file 5: Figure S5: SMI32 immunostaining quantification in white matter spinal cord sections during the course of EAE models. a Representative SMI-32 immunostaining (red) in cervical spinal cord from PAI-1 WT and PAI-1 KO mice at onset (14 dpi), peak (18 dpi) and late stages (45 dpi) during MOG-induced EAE (DAPI: blue). b Corresponding quantifications of axonal damage in cervical spinal cord from PAI-1 WT and PAI-1 KO mice. c Representative SMI32 immunostaining (red) in spinal cord from control and anti-PAI-1 antibody-treated mice at acute (16 dpi), remission (28 dpi) and late stages (45 dpi) during PLP-induced EAE (DAPI: blue). d Corresponding quantifications of axonal damage in spinal cord from control and anti-PAI-1 antibody-treated mice. Histograms show mean ± SEM, n=3 per condition. Mann-Whitney U test; *p < 0.05. Scale bars: 40µm. (PDF 543 KB)

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the French Ministry of Higher Education, the INSERM (French National Institute for Health and Medical Research), the regional Council of Normandy, the ARSEP foundation and the FRM (Fondation pour la recherche médicale). We thank Dr Paul Declerck for the gift of PAI-1 blocking antibody.

Abbreviations

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CTCF

Corrected total cell fluorescence

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- KO

Knockout

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- NSP

Neuroserpin

- PAI-1

Type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor

- PAS

Plasminogen activation system

- PLG

Plasminogen

- PN-1

Protease nexin 1

- TAFI

Thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor

- tPA

Tissue-type plasminogen

- WT

Wild type

Author contributions

HL designed the experiments, performed in vitro and in vivo studies, analyzed data, and participated in manuscript preparation. SG analyzed data and participated in manuscript preparation. AP performed reactive astrogliosis and axonal damage experiments and analyzed data. AF generated P-sel+ and P-sel− tissues. A-CB set up and performed FISH study. DV drafted the manuscript. MC-S gave expertise in the design of FISH study and drafted the article. FD designed the study and wrote the article. IB designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the French Ministry of Higher Education, the INSERM (French National Institute for Health and Medical Research), the regional Council of Normandy, the ARSEP foundation and the FRM (Fondation pour la recherche médicale).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with French ethical laws (Decree 87/848) and European guidelines (Directive 2010/63/UE) for the care and use of laboratory animals. Experiments were undertaken in the housing and laboratories (approval #F14118001) and have been approved by the ethics committee no. 52 on animal experiments (CENOMEXA) and by the French Ministry of Research under the project license number #10799. All experiments were performed following the ARRIVE guidelines (www.nc3rs.org.uk), including randomization of treatment as well as analysis blind to the treatment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fabian Docagne and Isabelle Bardou have equal contribution.

References

- 1.Petersen MA, Ryu JK, Akassoglou K. Fibrinogen in neurological diseases: mechanisms, imaging and therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(5):283–301. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gveric D, Hanemaaijer R, Newcombe J, van Lent NA, Sier CF, Cuzner ML. Plasminogen activators in multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the inflammatory response and axonal damage. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 10):1978–1988. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gveric D, Herrera B, Petzold A, Lawrence DA, Cuzner ML. Impaired fibrinolysis in multiple sclerosis: a role for tissue plasminogen activator inhibitors. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 7):1590–1598. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryu JK, Petersen MA, Murray SG, Baeten KM, Meyer-Franke A, Chan JP, et al. Blood coagulation protein fibrinogen promotes autoimmunity and demyelination via chemokine release and antigen presentation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8164. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Docagne F, Nicole O, Marti HH, MacKenzie ET, Buisson A, Vivien D. Transforming growth factor-beta1 as a regulator of the serpins/t-PA axis in cerebral ischemia. FASEB J. 1999;13(11):1315–1324. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.11.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louessard M, Lacroix A, Martineau M, Mondielli G, Montagne A, Lesept F, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator expression is restricted to subsets of excitatory pyramidal glutamatergic neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(7):5000–5012. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buisson A, Nicole O, Docagne F, Sartelet H, Mackenzie ET, Vivien D. Up-regulation of a serine protease inhibitor in astrocytes mediates the neuroprotective activity of transforming growth factor beta1. FASEB J. 1998;12(15):1683–1691. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández-Monreal M, López-Atalaya JP, Benchenane K, Léveillé F, Cacquevel M, Plawinski L, et al. Is tissue-type plasminogen activator a neuromodulator? Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25(4):594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassé F, Bardou I, Danglot L, Briens A, Montagne A, Parcq J, et al. Glutamate controls tPA recycling by astrocytes, which in turn influences glutamatergic signals. J Neurosci. 2012;32(15):5186–5199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5296-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briens A, Bardou I, Lebas H, Miles LA, Parmer RJ, Vivien D, et al. Astrocytes regulate the balance between plasminogen activation and plasmin clearance via cell-surface actin. Cell Discov. 2017;3:17001. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehra A, Ali C, Parcq J, Vivien D, Docagne F. The plasminogen activation system in neuroinflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2016;1862(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.East E, Baker D, Pryce G, Lijnen HR, Cuzner ML, Gverić D. A role for the plasminogen activator system in inflammation and neurodegeneration in the central nervous system during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(2):545–554. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62996-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.East E, Gverić D, Baker D, Pryce G, Lijnen HR, Cuzner ML. Chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (CREAE) in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 knockout mice: the effect of fibrinolysis during neuroinflammation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34(2):216–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davalos D, Ryu JK, Merlini M, Baeten KM, Le Moan N, Petersen MA, et al. Fibrinogen-induced perivascular microglial clustering is required for the development of axonal damage in neuroinflammation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1227. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yates RL, Esiri MM, Palace J, Jacobs B, Perera R, DeLuca GC. Fibrin(ogen) and neurodegeneration in the progressive multiple sclerosis cortex: Fibrin(ogen) and Neurodegeneration in MS Cortex. Ann Neurol août. 2017;82(2):259–270. doi: 10.1002/ana.24997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akenami FO, Koskiniemi M, Färkkilä M, Vaheri A. Cerebrospinal fluid plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in patients with neurological disease. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50(2):157–160. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onodera H, Nakashima I, Fujihara K, Nagata T, Itoyama Y. Elevated plasma level of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1999;189(4):259–265. doi: 10.1620/tjem.189.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Martín MY, González-Platas M, Jiménez-Sosa A, Plata-Bello J, Carrillo-Padilla FJ, Franco-Maside A, et al. Can fibrinolytic system components explain cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis? J Neurol Sci. 2017;382:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundgaard I, Osório MJ, Kress BT, Sanggaard S, Nedergaard M. White matter astrocytes in health and disease. Neuroscience. 2014;276:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fournier AP, Gauberti M, Quenault A, Vivien D, Macrez R, Docagne F. Reduced spinal cord parenchymal cerebrospinal fluid circulation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39(7):1258–1265. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18754732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruckert G, Vivien D, Docagne F, Roussel BD. Normalization of reverse transcription quantitative PCR data during ageing in distinct cerebral structures. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1540–1550. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson C, Paxinos G, Kayalioglu G, Heise C. Chapter 16 - Atlas of the Mouse Spinal Cord. In: Watson C, Paxinos G, Kayalioglu G, editors. The Spinal Cord [Internet] San Diego: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 308–379. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fournier AP, Quenault A, Martinez de Lizarrondo S, Gauberti M, Defer G, Vivien D, et al. Prediction of disease activity in models of multiple sclerosis by molecular magnetic resonance imaging of P-selectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(23):6116–6121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619424114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liddelow SA, Barres BA. Reactive astrocytes: production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity. 2017;46(6):957–967. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van De Craen B, Scroyen I, Abdelnabi R, Brouwers E, Lijnen HR, Declerck PJ, et al. Characterization of a panel of monoclonal antibodies toward mouse PAI-1 that exert a significant profibrinolytic effect in vivo. Thromb Res. 2011;128(1):68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietzmann K, Bossanyi Pv, Krause D, Wittig H, Mawrin Ch, Kirches E. Expression of the plasminogen activator system and the inhibitors PAI-1 and PAI-2 in posttraumatic lesions of the CNS and brain injuries following dramatic circulatory arrests: an immunohistochemical study. Pathol Res Practice. 2000;196(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(00)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu R-M, van Groen T, Katre A, Cao D, Kadisha I, Ballinger C, et al. Knockout of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene reduces amyloid beta peptide burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(6):1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boche D, Cunningham C, Docagne F, Scott H, Perry VH. TGFβ1 regulates the inflammatory response during chronic neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22(3):638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroksveen AC, Opsahl JA, Guldbrandsen A, Myhr K-M, Oveland E, Torkildsen Ø, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid proteomics in multiple sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854(7):746–756. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emeis JJ, Hoekzema R, de Vos AF. Inhibiting interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha does not reduce induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 by endotoxin in rats in vivo. Blood. 1995;85(1):115–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.V85.1.115.bloodjournal851115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Z, Nakamura K, Gershbaum S, Wang X, Thomas S, Bessler M, et al. Interacting hepatic PAI-1/tPA gene regulatory pathways influence impaired fibrinolysis severity in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(8):4348–4359. doi: 10.1172/JCI135919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenoir S, Varangot A, Lebouvier L, Galli T, Hommet Y, Vivien D. Post-synaptic release of the neuronal tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:164. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hultman K, Blomstrand F, Nilsson M, Wilhelmsson U, Malmgren K, Pekny M, et al. Expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and protease nexin-1 in human astrocytes: Response to injury-related factors. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(11):2441–2449. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko HM, Lee SH, Kim KC, Joo SH, Choi WS, Shin CY. The role of TLR4 and Fyn interaction on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated PAI-1 expression in astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;52(1):8–25. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8837-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Escartin C, Galea E, Lakatos A, O’Callaghan JP, Petzold GC, Serrano-Pozo A, et al. Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(3):312–325. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00783-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groves A, Kihara Y, Jonnalagadda D, Rivera R, Kennedy G, Mayford M, et al. A functionally defined in vivo astrocyte population identified by c-Fos activation in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis modulated by S1P signaling: immediate-early astrocytes (ieAstrocytes) eNeuro. 2018;5(5):ENEURO.0239-18.2018. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0239-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Itoh N, Itoh Y, Tassoni A, Ren E, Kaito M, Ohno A, et al. Cell-specific and region-specific transcriptomics in the multiple sclerosis model: focus on astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(2):E302–E309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716032115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borggrewe M, Grit C, Vainchtein ID, Brouwer N, Wesseling EM, Laman JD, et al. Regionally diverse astrocyte subtypes and their heterogeneous response to EAE. Glia. 2021;69(5):1140–1154. doi: 10.1002/glia.23954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryu JK, Rafalski VA, Meyer-Franke A, Adams RA, Poda SB, Rios Coronado PE, et al. Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(11):1212–1223. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0232-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baumeier C, Escher F, Aleshcheva G, Pietsch H, Schultheiss H-P. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 reduces cardiac fibrosis and promotes M2 macrophage polarization in inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2021;116(1):1. doi: 10.1007/s00395-020-00840-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubala MH, Punj V, Placencio-Hickok VR, Fang H, Fernandez GE, Sposto R, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promotes the recruitment and polarization of macrophages in cancer. Cell Rep. 2018;25(8):2177–2191.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poggi M, Paulmyer-Lacroix O, Verdier M, Peiretti F, Bastelica D, Boucraut J, et al. Chronic plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) overexpression dampens CD25+ lymphocyte recruitment after lipopolysaccharide endotoxemia in mouse lung. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(12):2467–2475. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thapa B, Kim YH, Kwon H-J, Kim D-S. The LRP1-independent mechanism of PAI-1-induced migration in CpG-ODN activated macrophages. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;49:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Additional file 1: Figure S1. PAS gene expression in forebrain, cerebellum and spinal cord during the course of MOG-induced EAE. Gene expression of a-c tPA, d-f NSP, g-i PN-1, j TAFI, k, l PAI-1 and m-o PLG in a, d, g, j, m the spinal cord, b, e, h, k, n the cerebellum and c, f, i, l, o the forebrain of mice during the course of MOG-induced EAE. RT-qPCR results expressed as mean ± SEM, n=5 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: * and § indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham and Pre-On respectively, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. tPA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; NSP: Neuroserpin; PN-1: protease nexin-1; PLG: Plasminogen; TAFI: thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor; PAI-1: type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. Pre-On: pre-onset; On: onset; Su: surge; Ch: chronic as depicted in Fig. 1a. (PDF 235 KB)

Supplementary file2 Additional file 2: Figure S2.PAS gene expression in forebrain, cerebellum and spinal cord during the course of PLP-induced EAE. Gene expression of a-c tPA, d-f NSP, g-i PN-1, j TAFI, k, l PAI-1 and m, n PLG in a, d, g, j, m the spinal cord, b, e, h, k, n the cerebellum and c, f, i, l the forebrain of mice during the course of PLP-induced EAE. RT-qPCR results expressed as mean ± SEM, n=5 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: *, §, #, † indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham, Pre-On, Rem and Rel respectively, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. tPA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; NSP: Neuroserpin; PN-1: protease nexin-1; PLG: Plasminogen; TAFI: thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor; PAI-1: type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. Pre-On: pre-onset; On: onset; Sc1/2/3/4/2R: score 1/2/3/4/2 remitting; Rem: remission; Rel: relapse as depicted in Fig. 1d. (PDF 295 KB)

Supplementary file3 Additional file 3: Figure S3: PAI-1 immunostaining quantification in white matter spinal cord sections during the course of MOG-induced EAE model. a Representative PAI-1 immunostaining (red) in cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar sections of spinal cord from Sham and MOG-induced EAE mice for each stage of the disease (DAPI: blue). b Quantification of PAI-1 immunostaining coverage in cervical, high thoracic, low thoracic and lumbar sections of spinal cord from Sham and MOG-induced EAE mice. Histograms show mean ± SEM, n=3 per condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by FDR post-hoc test: * indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Sham, Δ indicates other significant differences (p < 0.05) between specific stages. Sc1/2/3/4: score 1/2/3/4. Scale bars: 50µm. (PDF 496 KB)