Abstract

Haematopoietic Stem cells (HSCs) have the potential for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation, and their behaviours are finely tuned by the microenvironment. HSC transplantation (HSCT) is widely used in the treatment of haematologic malignancies while limited by the quantity of available HSCs. With the development of tissue engineering, hydrogels have been deployed to mimic the HSC microenvironment in vitro. Engineered hydrogels influence HSC behaviour by regulating mechanical strength, extracellular matrix microstructure, cellular ligands and cytokines, cell–cell interaction, and oxygen concentration, which ultimately facilitate the acquisition of sufficient HSCs. Here, we review recent advances in the application of hydrogel-based microenvironment engineering of HSCs, and provide future perspectives on challenges in basic research and clinical practice.

Keywords: Engineered biomaterial, Haematopoietic stem cell (HSC), Bone marrow microenvironment, Stem cell niche, HSCT, HSC expansion

Introduction

Stem cells usually refer to cell clone with the ability to both self-renew and differentiate in multi-direction [1]. The specific function of stem cells is dependent on their status of proliferation or differentiation. There are three states of stem cells in vivo: a quiescent state with a lower metabolism and in the absence of differentiation, a self-renewal state to maintain and expand the stem cell pool, and a differentiated state towards mature lineage cell types [2]. These states are in dynamic balance and are closely related to the microenvironment known as the stem cell niche, which is a concept proposed by Schofield in 1978 and it was later found to be strongly associated with ageing, tissue degeneration, and malignant diseases [3].

Longitudinal studies have shown that stem cells possess immense potential in clinical application. Stem cell therapy can regenerate patient-specific dysfunctional tissues and provide new therapeutic options against complicated diseases such as leukaemia, heart failure, and neurodegenerative disease. However, most clinical trials with stem cells have not yet shown satisfactory results. The generation of the stem cell pool, maintenance of stemness, and control of the cell state before and after transplantation are still obstacles to the clinical translation of stem cell therapy. Thus, it is particularly important to delineate the stem cell microenvironment for a new research trend to artificially mimic the stem cell microenvironment in vitro to facilitate the expansion of stem cells in a quiescent and undifferentiated state.

Among diverse stem cell populations, haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have been the first and most widely used in clinical application considering their remarkable success in the treatment of haematopoietic malignancies. One of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved stem cell products is CD34+ haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from either donor-derived peripheral blood or umbilical cord blood, which benefits patients suffering from haematopoietic malignancies [4, 5]. However, there still exists a huge unmet need in HSCT due to the limited number of HLA-matched HSC donors. In addition, acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) are major life-threatening complications in patients who receive allogeneic HSCT. To solve these problems, scientists have developed multiple strategies to manipulate the cells from autologous origin, including editing the abnormal genes, expanding HSCs ex vivo, selectively differentiating embryonic stem cells (ESCs)/induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into HSCs [6].

To facilitate ex vivo HSC expansion or in vitro differentiation of iPSCs into HSCs, researchers have drawn from what is known about the mutual regulation between HSCs and their supporting niche, and successfully recapitulated an artificial HSC niche using nanomaterials such as hydrogels. Hydrogel elasticity, biocompatibility, and microstructure can vary, which makes hydrogels ideal culture substrates. Studies have documented hydrogels are suitable for forming artificial microenvironments in vitro by modulating crucial parameters, such as mechanical strength, extracellular matrix microstructure, cellular ligands and cytokines, cell–cell interaction, and oxygen concentration. Moreover, recent studies have shown that stem cells generated from hydrogel-culturing system exert better therapeutic effects [1, 7, 8].

Here, we describe in detail how the stem cell microenvironment reshaped by hydrogels influence HSCs behaviour. Furthermore, based on the special characteristics of HSCs and the unique properties of hydrogels, we propose multiple strategies for improving HSC expansion and differentiation for HSCT and summarize the current progress in the clinical application. In the future, hydrogel-based microenvironment engineering for stem cell therapy will exert better clinical efficacy.

Haematopoietic stem cells and the haematopoietic stem cell microenvironment

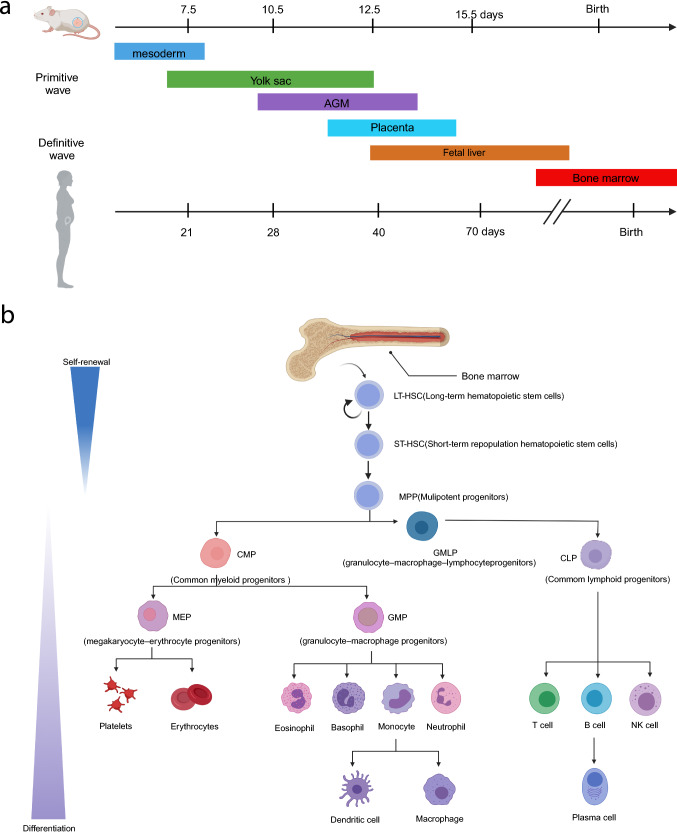

Haematopoiesis is a highly dynamic physiological process in which a small number of HSCs continuously produce all the blood cells of the human body. During foetal development, primitive haematopoiesis occurs first in the yolk sac, followed by the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) kidney region, then in the placenta, foetal liver (FL), spleen, and finally in the bone marrow (BM) [9]. According to the different developmental stages of the haematopoietic system, HSCs can be divided into embryonic HSCs and adult HSCs with distinct function and behaviour, which are closely related to their microenvironment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Development and hierarchy of HSCs in mouse and human. a Embryonic sites of blood development in mice and humans. b Overview of the haematopoietic hierarchy. Created with BioRender.com

Embryonic haematopoietic stem cells

During embryonic development, the haematopoietic system is gradually formed, starting with the primitive haematopoiesis that arises from the embryonic mesoderm and progresses to the yolk sac to produce erythrocytes and other myeloid cells. As the embryo develops, multilineage HSPCs begin to emerge from the AGM region to derive HSCs with ever-changing surface markers [10–14].For the first time, Liu et al. used single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to analyse isolated humans HSC precursors with high-purity, and elucidated molecular mechanisms of HSC generation, development, and maturation [15]. The results revealed an additional distinct intermediate stage with differential RUNX1 dosage, accompanied by increased chromatin accessibility of motifs in SOX, FOX, GATA and SMAD [16], which profoundly influenced the process of endothelial-to-haematopoietic transition (EHT). Humans embryonic HSCs then primarily migrate to FL for expansion and differentiation, then being incorporated into the BM through the recruitment of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) shortly before birth. Other factors, such as C-X-C Chemokine Receptor 4 (CXCR4), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), the neuronal guidance protein Robo4, C-kit, and calcium-sensing receptor (CaR), all promote HSC translocation into the BM as the main site for the generation of adult HSCs [17] (Fig. 1a).

Adult haematopoietic stem cells

Adult HSCs mainly exist in the BM, but they can also be isolated from cord blood or peripheral blood with a rare population of approximately 0.005–0.01% compared to that in the BM [18, 19]. Adult HSCs have the property of self-renewal and are capable of differentiating into all functional haemocytes. The self-renewal prolongs the lifespan of stem cells, while differentiation maintains haematopoietic homeostasis through mature haemocyte production [20]. Specifically, long-term haematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) maintain the ultimate haematopoietic function and can differentiate into short-term haematopoietic stem cells (ST-HSCs), and then multipotential progenitor cells (MPPs). The self-renewal ability of progenitors gradually declines, while preserving pluripotent differentiation potential. MPPs continue to derive myeloid cells (erythrocytes, platelets, granulocytes, macrophages) and lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells). In the BM, most HSCs are in the quiescence state, named the G0 stage. Only upon stimulation can HSCs be activated and generate more mature haemocytes or proliferate to maintain the pool. In addition to BM localization, HSCs also traverse and circulate in peripheral blood dependent on biomolecular signalling (Fig. 1b). Circulating HSCs also contribute to emergent haematopoiesis under stress [21].

HSPCs subsets can be distinguished and separated according to specific surface antigens by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. However, some specific HSCs subtypes lack appropriate markers for isolation due to poor understanding or definition. Therefore, it is necessary to explore more specific HSCs surface antigens (CD38, CD90, and CD150) [22]. The early expression of HSCs surface antigens during different stages in mice and human is comprehensively enumerated in Table 1. Adult HSCs possess the ability to undergo complete and long-term haematopoietic regeneration after transplantation. With the development of novel technology, such as chromatin immunoprecipitation and high throughput sequencing (CHIP-seq), CD49f+ HSCs was discovered to have long-term haematopoietic reconstruction ability after transplantation, determined by the haematopoietic damage reconstruction experiment and the competitive reconstruction or restrictive dilution experiments [23]. Functional HSCs could also be detected by colony-forming units (CFU) in the long-term culture-initiating cell assays and the cobblestone-area forming cell assays in vitro [24].

Table 1.

Early expression of surface antigens on human or murine HSPCs, HSCs, and other committed progenitors [25, 26]

| Human | Mice | |

|---|---|---|

| HSPCs | Lin−CD34+CD38− | Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+(LSK) |

| HSCs | Lin−CD34+CD38−CD90+CD45RA− | Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+Flk2−CD34−Slamf1+ |

| MPPs | Lin−CD34+CD38−CD90−CD45RA− | Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+Flk2+CD34+ |

| CLPs | Lin−CD34+CD38+CD10+ | Lin− Flk2+IL7Rα+ CD34+ |

|

CMPs MEPs |

Lin− CD34+CD38+IL3RαlowCD45RA− Lin−CD34+CD38+IL3Rα−CD45RA− |

Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγII/IIIRlo CD34+ Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγII/IIIR−CD34− |

| GMPs | Lin−CD34+CD38+ IL3Rα+CD45RA− | Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγII/IIIRhi CD34+ |

HSPC haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell, HSC haematopoietic stem cell, MPP multipotential progenitor cell, CLP common lymphoid progenitor, CMP common myeloid progenitor, MEP megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor, GMP granulocyte–macrophage progenitor

Haematopoietic stem cell microenvironment

During the transition in the mode of haematopoiesis, the cellular kinetics of HSCs vary remarkably. Thus, it is essential to understand how the HSC microenvironment influences HSCs behaviour.

Embryonic hematopoietic stem cell microenvironment

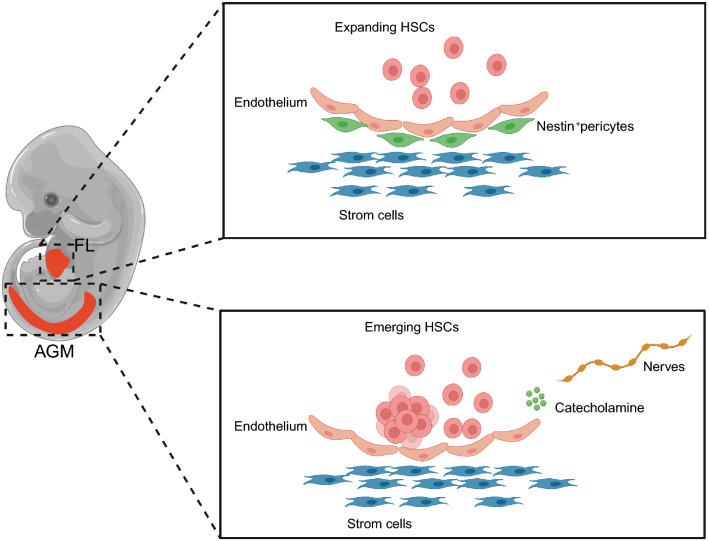

Embryonic HSCs originated from AGM further translocate into the FL and expand their population. Particularly, AGM-derived stromal cells and endothelial cells maintain the stemness of embryonic HSCs [27, 28]. In addition, sympathetic nervous system participates in the establishment of the AGM microenvironment to regulate the development of embryonic HSCs, which is tightly relied on a network of transcription factors, especially the GATA family [29]. Specifically, GATA3 deletion in embryos leads to sympathetic neuron defects and reduced levels of catecholamine in the AGM region [30]. Embryonic HSCs maintain self-renewal through adrenergic receptor-mediated signalling pathways in response to catecholamine in the AGM microenvironment. Therefore, signalling from the sympathetic nervous system dependent on GATA3 is essential for HSCs during embryogenesis [31]. The FL is the major organ for HSC expansion. Studies have shown that stem cell factor (SCF)+DLK+ FL progenitor cells promote HSC expansion by secreting angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3), CXCL12, insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), SCF, and thrombopoietin (TPO) [32]. In addition, vascular cells and vascularity-related transcription factors also contribute to HSC maintenance. For example, Nestin+neuron-glial 2 (NG2)+ pericytes associated with portal vessels provide the FL microenvironment for HSC expansion [33]. Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) promotes HSC maintenance by upregulating ANGPTL3 expression in the microenvironment [34]. These effectors subsequently mediate the migration of HSCs into the spleen and terminal localization of HSCs in the BM, paving the way for adult haematopoiesis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

HSC niche during embryonic development in mice. The magnified images (right) show the embryonic HSC microenvironment in the AGM and FL. In the AGM, stromal cells and catecholamines released from the sympathetic nervous system regulate HSC differentiation. In the FL liver, HSCs undergo dramatic expansion before colonizing the BM. AGM aorta-gonad-mesonephros, FL foetal liver. Created with BioRender.com

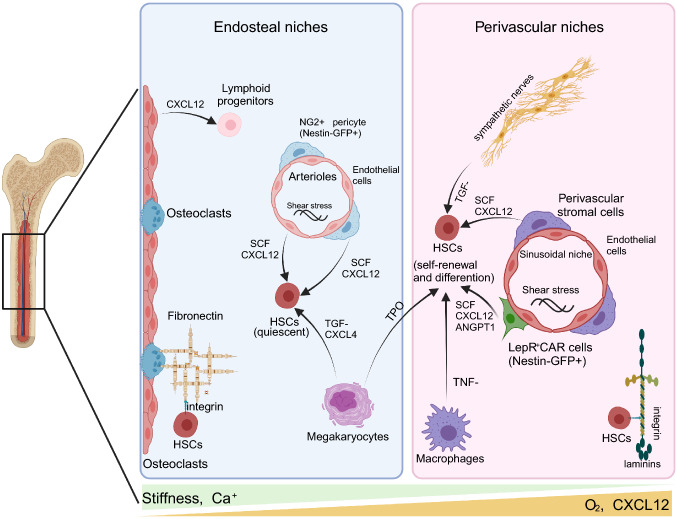

Adult haematopoietic stem cell microenvironment

The BM microenvironment contains the endosteal niche formed by osteoblasts and the perivascular niche composed of cells around blood vessels, in which HSCs migrate between the two components [35] (Fig. 3). Diverse HSCs subsets have different positions in the BM, such as the endosteal niche, arteriole niches, and sinusoidal niches. Quiescent HSCs are located close to arteriole niches, while self-renewing HSCs are enriched in endosteal zones [36]. Recently, controversy and amendments have been raised regarding the definition of the HSC niche due to the discovery of specific HSCs surface markers as well as improvements in microscopic in vivo imaging and three-dimensional (3D) visualization technology. Mendez-Ferrer et al. found that mouse HSCs were distributed near Nestin−GFP+ mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) around blood vessels in an irradiation transplantation experiment [37]. Nombela-Arrieta et al. also demonstrated that endogenous HSCs were located in perivascular niches near the intima of bone by quantitative imaging of bone sections [36]. 3D imaging revealed that some quiescent HSCs were distributed in the niches of the NG2+ arterioles while proliferating HSCs were far away from the niches [38]. Therefore, microenvironmental components in the BM are particularly important for maintaining the dynamic balance between self-renewal and differentiation of HSCs.

Fig. 3.

Distinct niches in the adult bone marrow. The BM mainly includes the endosteal and perivascular niches. The endosteal niche, adjacent to the endosteum of the trabecular bone, contributes to maintaining quiescent HSCs, while the perivascular niche initiates HSC self-renewal and differentiation. Angpt1 angiopoietin-like 3, FL foetal liver, CAR cell cxcl12-abundant reticular cell, CXCL12 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12, HSC hematopoietic stem cell, LepR leptin receptor-expressing, NG2 neuron-glial 2, SCF stem cell factor, TGF-β transforming growth factor-β, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-alpha, TPO thrombopoietin. Created with BioRender.com

Extracellular matrix

The extracellular matrix (ECM) provides structural support for HSCs and serves as an important element in the BM microenvironment. The BM ECM has unique physical structures with specific matrix stiffness and adhesion ligands.

The morphology and function of HSCs are closely related to matrix stiffness. Mechanical analysis of porcine BM indicates that the marrow is elastic with an effective Young’s modulus ranging from 0.25 to 24.7 kPa [39]. HSCs remain round on soft matrices (3.7 kPa) but are more scattered with elongated and polarized cell bodies on stiff matrices (> 44 kPa). HSCs also exhibit enhanced differentiation ability on stiff substrates (CFU-EM and CFU-GEMM), as proven by clone formation experiments [40]. Similarly, BM-derived LSK (Lin−Sca1+cKit+) cells have reduced proliferation on a stiffer matrix but have increased clonogenesis [41]. The adhesion and migration of HSCs increase with osteoblast stiffness in the intima niche [42].

In addition to matrix stiffness, matrix viscoelasticity also influences HSC expansion. Tropoelastin, a soluble precursor of elastin with a propensity to self-aggregate through coacervation, significantly promoted mouse and human HSC expansion [43]. Furthermore, the EMC exerts tension on HSCs that regulates the stem cell ability of proliferation, differentiation potential, and secretion [44]. For example, HSCs are constantly subjected to haemodynamic forces in the perivascular niche with maternal blood flow creating a shear force that promotes the differentiation of embryonic HSCs [45]. HSCs can sense dynamic changes in the ECM mechanical signals and transmit signalling to the nucleus through mechanical transduction pathways, initiating intracellular biochemical reactions [46].

Various ECM proteins exert effects on HSC function. Fibronectin promotes the long-term maintenance and expansion of HSCs cultured in vitro [40]. A higher level of fibronectin accumulates near the endosteal niche, while a higher expression of laminin is observed in the arteriole niche. In addition, integrins and other cell receptors together mediate the interaction between stem cells and ECM microenvironment. Integrins are the primary receptors for the ECM proteins, interacting with a variety of growth factor receptors, cytokine receptors, and other cell-surface adhesion molecules [47]. As heterodimeric transmembrane receptors, integrins affect the migration, proliferation, survival, and differentiation of HSCs by connecting the extracellular environment and the intracellular cytoskeleton. This process is achieved by activating downstream signalling pathways through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and PI3 kinase (PI3K) [48]. Nearly half of the integrin family bind to the ECM molecules through RGD (R: Arginine; G: Glycine; D: Aspartic acid), indicating that the RGD peptide sequence plays a central role in cell surface adhesion [49]. Moreover, the RGD peptide sequence mediates cell adhesion among diverse cell populations and induces specific cellular responses [50].

Signalling pathways

Biochemical factors and associated signalling pathways have a tremendous impact on HSC maintenance in the BM microenvironment. SCF is an important regulator expressed in endothelial cells and perivascular cells that regulates HSC proliferation. Zhang et al. combined four cytokines in culture, including SCF, TPO, IGF-2, and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-1, to amplify the number of mouse HSCs in approximately 20 times [51]. The Notch and Wnt signalling pathways contribute most to HSC function. Ciofani et al. found that Notch1 promoted T lymphocyte differentiation, while Notch2 was associated with erythroid progenitor cell differentiation [52]. Notch ligands have also been found to promote the maintenance and expansion of LT-HSCs [53]. Similarly, activation of β-catenin in the Wnt signalling pathway promotes the expansion of HSCs and maintains their ability of self-renewal [54]. Yamazaki et al. found that glial cells in the perivascular niche secrete transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-activating molecules and maintain the self-renewal of HSCs by inducing the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 in the TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway [55]. Interestingly, North et al. found that vitamin D increased the number of embryonic HSCs through the inflammatory chemokine CXCL8 [56].

Chemokines in the BM microenvironment also influence the behaviour of HSCs. CXCL12 is a chemokine mainly produced by CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells in the perivascular niche [57]. CXCL12 selectively promotes HSC quiescence and self-renewal, and it is associated with HSC homing, migration, retention, and long-term proliferation potential through the CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling cascade [58]. CXCR4 deficiency leads to a severe reduction in HSCs in the BM [59].

Cell–cell interactions

The communication between stem cells and other intrinsic niche cells is mediated by secretory factors and direct cell–cell interactions [60]. In the endosteal niche, osteoblasts are important for the maintenance of HSCs [61]. Studies have found that osteoblasts specifically express parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-associated protein receptor (PPR). Stimulation of PPR increases the number of osteoblasts and affects HSC expansion through the Notch signalling pathway, also known as the N-cadherin-mediated osteoblast-HSC interaction [62]. Precursor osteoblasts, such as Nestin+ MSCs, also promote HSC enrichment by expressing SCF [37]. Moreover, HSCs and osteoblasts are increased in bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A (BMP1A)-deficient mice [63]. For the vascular niche, the function of vascular endothelial cells and stromal cells is crucial for HSC mobilization and homing both in the BM and peripheral blood [64]. During embryonic development, the embryonic head serves as the site of embryonic HSCs production, with the proinflammatory factor tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) produced by macrophages in the head promoting the expansion and maturation of embryonic HSCs [65]. On the one hand, endothelial cells stimulate the incremental expansion of HSCs through direct cell–cell contact [66]. On the other hand, endothelial cells activated by the Akt/mTOR signalling pathway support the self-renewal and expansion of LT-HSCs (CD34−Flt3−LSK) by regulating vascular secretory factors [53]. Except for vascular endothelial cells, Nestin-GFP+ cells participate in the maintenance of HSCs by expressing high levels of Angpt1, SCF, and CXCL12 [37]. Nestin-GFP+ cells show MSCs and form pluripotent, self-renewing intermediate spheres [37]. Platelet-derived growth factorsα (PDGFRα) and CD51 are also highly expressed on the cell surface and contribute to the maintenance and expansion of human HSCs [67]. Meanwhile, macrophages, adipocytes, CXCL12 abundant reticulum cells, and nerve cells also exert positive effects on the behaviour of HSCs.

Other factors

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are also essential for the regulation of HSCs. ROS induces the mTOR pathway activation and the Wnt/β-catenin protein inactivation, resulting in HSC migration, differentiation, and ageing [68, 69]. The BM provides a hypoxic microenvironment, which limits the production of ROS and wields long-term protection for HSCs [70]. Specifically, the hypoxic microenvironment supports the self-renewal, stemness, and expansion of HSCs via the transcriptional activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) [71]. In addition, hypoxia at the EHT stage significantly activates artery-related signalling genes and promotes embryonic HSC regeneration [72]. Several other factors, including calcium ions and oxygen tension, also participate in the regulation of HSCs.

Due to the limitation of in vivo experiments, HSC microenvironment simulation in vitro has become a new research strategy to modulate the fate of HSCs. With the development of biomaterials, hydrogel platforms have been adopted to mimic the stem cell microenvironment in order to regulate the self-renewal and differentiation behaviour of stem cells by controlling biochemical and biophysical properties. Hopefully, the novel hydrogel platform may facilitate better clinical application of HSCs.

Engineering hydrogels to recapitulate the HSC microenvironment

The HSCs microenvironment has a great influence on the generation, self-renewal, and differentiation of HSCs. Hydrogels have made significant progress in reshaping the cell microenvironment in vitro, and they can be redirected to influence stem cell behaviour [73].

Hydrogels

Hydrogels are three-dimensional structure formed by hydrophilic polymer chains with high water content and the ability to expand [77]. Due to their flexibility, biocompatibility, and ability to mimic the ECM, hydrogels have a wide range of applications in biomedical research, such as drug delivery, regenerative medicine, and tissue engineering [78].

The polymers that form hydrogels can be either natural or synthetic. Natural hydrogels usually include sodium alginate, collagen, gelatine, chitosan, hyaluronic acid, and fibrin [74]. In addition to their degradability and biocompatibility, natural hydrogels are widely available to provide a natural adhesion site for cells and other bioactive agents, which can be used for drug release and tissue regeneration [75]. For example, hyaluronic acid (HA) is a natural component of the ECM. Currao et al. used synthetic methacrylate hyaluronan hydrogel to embed CD34+ cells and found that HA can more closely mimic the BM niche for inducing the differentiation and function of megakaryocyte HSCs [76]. The gelation process and mechanical properties of natural hydrogels can be difficult to control, but the chemical structure of synthetic hydrogels is adjustable, and their physicochemical and mechanical properties can be optimized. Commonly used polymers of synthetic hydrogels include polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), poly (L-lactide) (PLLA), and polyacrylamide (PAM). However, synthetic hydrogels are limited by a lack of adhesion sites, biocompatibility, and difficulty in degradation. Therefore, natural hydrogels and synthetic hydrogels have complementary advantages in their characteristics. The purpose of studying hydrogels and stem cell niches is to design artificial microenvironments similar to those in vivo that induce stem cell behaviour, thus improving biocompatibility, promoting stem cell expansion, and facilitating subsequent mechanism research and clinical application. Many natural chemicals are being explored to supplement synthetic hydrogels with more bioactivity [77].

Different crosslinking methods have been developed to improve the stability and mechanical properties of hydrogels in addition to functional groups (sulfate, acrylate) or other components (gelatine, collagen, etc.), by changing the volume, shape, and viscoelasticity for the preparation of hydrogels with excellent structures and ideal properties [78]. Physical crosslinks include ionic/electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, crystallization, and thermally induced hydrophobic interactions based on lower critical solution temperature (LSCT) [79] or upper critical solution temperature (UCST) [80]. As no chemical crosslinking agent is involved, the potential cytotoxicity is avoided [81]. Physically crosslinked hydrogels are self-healing and injectable at room temperature so that living cells and therapeutic drugs could be easily delivered. Chemical crosslinks include photopolymerization [82], enzyme-induced crosslinking [83, 84], and “click” chemistry [85] (Michael type-addition [86, 87], Diels–Alder “click” reaction [86], and Schiff base formation [88]). Under physiological condition, chemically crosslinked hydrogels exhibit higher stability, more adjustable degradation, and better mechanical properties than physically crosslinked hydrogels. In addition, with the rapid development of tuneable and modifiable hydrogels, smart hydrogel that can crosslink itself in response to physical or chemical stimulus has wider prospects in application [89]. For example, thermoresponsive hydrogels undergo gelation from liquid after injection at room temperature [77]. In addition, the ability of biodegradation is also important for the application of hydrogels [90, 91].

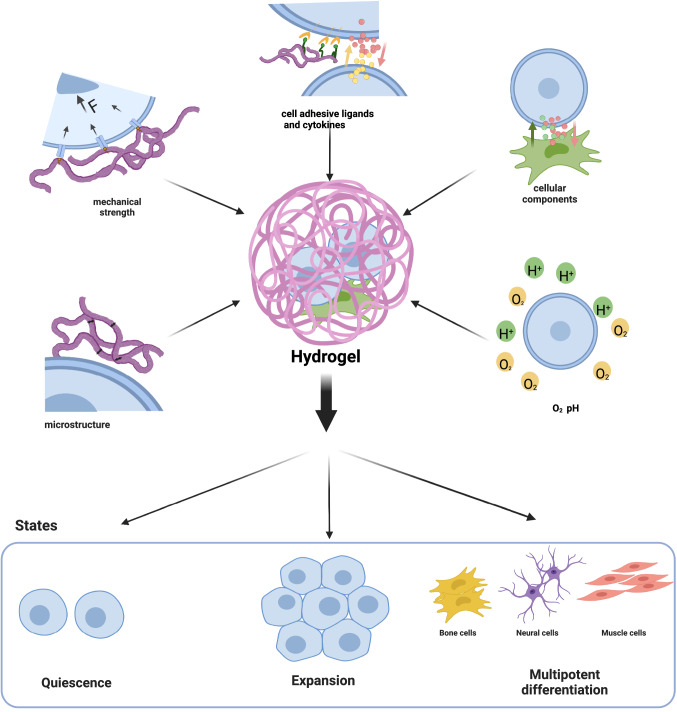

Key factors of the HSC microenvironment in engineered hydrogels

Engineered hydrogels could mimic the stem cell microenvironment from the following aspects: mechanics, ECM microstructure, cellular ligands and cytokines, cellular components, and oxygen concentration (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The engineered HSC microenvironment known to regulate HSC states. To regulate HSC behaviour in vitro, the hydrogels mimic some aspects of the stem cell microenvironment, such as the mechanics, extracellular matrix microstructure, cell adhesive, cellular ligands and cytokines, cell–cell interactions, and oxygen concentration. Created with BioRender.com

ECM mechanics

Stiffness

Stiffness is a measure of elastic deformation under stress and is usually determined by the elastic modulus or Young’s modulus. Hydrogel stiffness can be controlled by the polymer molecular weight, concentration, and degree of crosslinking [46, 92]. The hydrogel stiffness used for stem cell culture ranges from 0.1 kPa (containing 99.95% water) to hundreds of kPa [93].

Stiffness has profound effects on stem cell behaviour, in which BM-MSCs present the most prominent alteration during multilineage differentiation [94]. Studies have shown that stem cell favours differentiation into cell lineages related to soft tissue (brain, adipose tissue, and muscle) when under softer hydrogel culture, while the differentiation into stiff tissue-related cell lineages, such as cartilage and precalcified bone, is more dependent on stiff hydrogel culture [95]. Soft matrix stiffness (0.1–1 kPa) induces the production of neuronal precursors from human BM-MSCs, whereas stiff matrix stiffness (25–40 kPa) is associated with osteogenic differentiation [96, 97]. To better mimic the in vivo stem cell microenvironment and reduce cytotoxicity, more efforts have been made to develop a 3D culture matrix to embed cells with biocompatible materials such as PEG and HA. One study found that 3D hydrogels with different stiffnesses can induce osteogenic or lipogenic differentiation of MSCs. However, the change in hydrogel stiffness did not significantly affect the cell morphology of MSCs but did affect the formation of cell-RGD bonds, which ultimately affected the direction of MSC differentiation [98]. The effect of stiffness on stem cells was initially studied on a 2D matrix (polyacrylamide hydrogel) [95]. Keming et al. found that hESCs proliferated well and maintained self-renewal in a 350 Pa HA-tyramine hydrogel [99]. Specifically, the thin layer protein-coated soft hydrogel promoted neuron regeneration at the injury site in the central nervous system and inhibited astrocyte growth. Adult neural stem cells (NSCs) were cultured on a synthetic interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) hydrogel with stiffness adjusted between 10 and 10,000 Pa. When the stiffness of hydrogels coated with fibronectin is close to that of brain tissue (100–500 Pa), it is beneficial to neuron proliferation and survival, while stiffer hydrogels (1000–10,000 Pa) promote differentiation into glial cells [100]. Through bioinformatics analysis, Darnell et al. discovered that hydrogel stiffness could regulate embedded mouse MSCs to secrete various cytokines to correspondingly affect HSC differentiation [101]. The study also found that the growth morphology and proliferative ability of HSCs cultured in 3.4 kPa hydrogel were better than those cultured in 44 kPa hydrogel or glass stiffness, indicating that stiffness affects HSC self-renewal and differentiation to a certain extent [40].

In conclusion, stiffness interplays with multiple environmental features, especially surface ligand and stress relaxation, and it regulates a variety of stem cell behaviour. In addition to proliferation and differentiation, specific stem cell function could be influenced more strongly by hydrogel stiffness [101].

Viscoelasticity

Biopolymer hydrogels also exhibit unique viscoelasticity, which is a time-related mechanical property specifically referring to the behaviour of stress relaxation (where stress decreases with time) or creep deformation (where strain increases with time under constant stress) [102]. Collagen and fibrin in the natural ECM possess viscoelasticity independent of matrix stiffness [103]. When applying constant stress, partial stress relaxation occurs. Hydrogel viscoelasticity can be altered by changing the hydrogel polymer molecular weight, chain length or degradation [104, 105]. Polymer molecular weight reduction and calcium concentration alteration for crosslinking accelerate stress relaxation of hydrogels without affecting the initial elastic modulus [106]. In addition, the polymer concentration and crosslinking density also influence the viscoelasticity and change the hydrogel stiffness as well [107, 108].

Hydrogel viscoelasticity has a significant effect on stem cell behaviour, such as morphological changes, migration, and proliferation [106]. Increased stress relaxation is correlated with improved MSCs proliferation, differentiation, and bone regeneration [106]. It also maintains the stemness of neuronal progenitor cells [109]. Chaudhuri et al. found that cell proliferation was reduced in an alginate elastic matrix compared with a soft matrix under the same modulus [110]. Hydrogel viscoelasticity combined with pore size and matrix degradability influences mechanical confinement, thus affecting cell migration ability [102]. Hydrogel viscoelasticity also influences differentiation. For example, a microenvironment with high stress relaxation promotes MSCs expansion, which in turn induces transcription factors for osteogenic differentiation via mechanotransduction at the cell membrane [111]. More importantly, the matrix viscoelasticity may regulate cellular behaviour and initiate matrix remodelling or deposition by complex interactions, which is worth further research [102]. Last but not least, some factors related to viscoelasticity, including viscoplasticity, nonlinear elasticity, and poroelasticity, may also differentially regulate stem cell behaviour [102]. For instance, viscoplasticity and viscoelasticity have opposite effects on cell spreading [112].

ECM microstructure

Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture technology has been standardized for the use of established cell lines in drug screening or disease modelling [113]. However, stem cells proliferating into a single layer in a 2D culture system could alter stem cell fate. HSCs, as a rare population suitable for suspension culture, are very sensitive to microenvironment elasticity. Studies have shown that HSCs cultured in a 2D system cannot maintain self-renewal in the initial population and behave abnormally in a nonphysiological way [114, 115]. One possible mechanism behind this behaviour is morphological alteration. Specifically, the internal cytoskeleton and nuclear structure are remodelled, which affects stemness-related gene expression and protein synthesis, resulting in a flattened shape and abnormal cellular behaviour [116]. In addition, insufficient ECM components, nutrients or oxygen may also contribute to the regulation of stem cell fate [117]. In addition, 2D cell culture systems do not properly mimic the microenvironment in vivo so that they are unsuitable for large-scale production.

In contrast, 3D culture hydrogel systems provide better microenvironment conditions for stem cell expansion and function by manipulating the microstructure (size, shape, porosity) and mechanical properties using a range of preparation methods, such as emulsion templating [118], freeze-drying [119], electrospinning [120], selective laser sintering [121], and 3D cell printing [122]. 3D cell printing is often used to induce MSCs osteogenic differentiation [123]. McKee et al. developed a self-assembled 3D hydrogel combined with sulfhydryl-functionalized dextran (Dex-SH) and tetraacrylate-functionalized PEG (PEG-4-Acr) [124]. The method maintained the self-renewal of mouse ESCs for more than 6 weeks and enhanced the expression of Oct4, Nang, and Klf4 during long-term culture. Gerecht et al. found that long-term 3D culture of human ESCs in a photopolymerized HA hydrogel allowed cells to maintain the potential for self-renewal with an undifferentiated state and normal karyotype for 20 days [125]. Moreover, the 3D coculture of MSCs and HSCs could significantly amplify CD34+ cells in cord blood in vitro. CD34+ cells exhibited superior morphology, migration, and adhesion properties in 3D hydrogel scaffolds (especially fibrin hydrogel scaffolds) compared to 2D cultures. Long-term transplantations also showed that 3D hydrogels had a higher chimerism rate [126]. MSCs-HSCs culture environment that mimics the in vivo haematopoietic chamber would be more beneficial for improving HSC function [127].

Cellular ligands and cytokines

The hydrogel system is an ideal platform for the incorporation of adhesive peptides and protein ligands since peptides can be coupled with the polymer chain. Combining adhesive peptides into a hydrogel system facilitates the regulation of ligand distribution in space. The concentration of cell adhesion ligands and the extent of ligand clustering affect stem cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration [128]. As discussed above, the interaction between RGD and other ligands is necessary to induce normal stem cell behaviour. In addition to RGD, other short peptide sequences that include collagen-derived ligands GFOGER and DGEA, as well as lamellar protein-derived ligands YIGSR and IKVAV, could also serve as adhesion ligands [129]. Mehta et al. found that alginate hydrogels enhanced the osteogenic differentiation of mouse MSCs in 3D culture, suggesting that the ligand DGEA could independently regulate stem cell behaviour [130]. In addition, the Notch ligand delta-like 1 (DL1) hydrogel scaffolds promote HSC differentiation into T cells [131].

Cytokines in the stem cell microenvironment are crucial for the regulation of stem cell fate. Accumulating evidence has indicated that hydrogels supplemented with cytokines mimic the in vivo stem cell microenvironment and provide better support for stem cell function. Heparan sulfate or peptide sequences could be incorporated to engineer hydrogel-based artificial niches containing signalling factors [132, 133]. For example, Douet et al. found that the sulfate component in the subventricular zone (SVZ) contributes to NSCs proliferation and function by increasing levels of FGF-2 in the niche [134]. Fibronectin, collagen, and proteoglycan can bind with originally insoluble growth factors, such as FGF, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and TGF-β, which establish a concentration gradient by local release depending on metalloproteinases, affecting stem cell migration or tissue morphogenesis accordingly. Currently, microfluidics, as a novel technology that allows accurate observation of molecular distribution and cell response through fluorescence microscopy, have been applied to hydrogel engineering. In the future, microfluidics may facilitate the incorporation of growth factors into the artificial niche [135].

Cellular components

Hydrogels provide a better platform with an adjustable microenvironment for stem cell coculture. As previously mentioned, co-culturing HSCs with osteoblasts or MSCs in vitro can partially modulate HSC behaviour in the BM microenvironment in vivo; the effect is clearer in the 3D cell culture system. Leisten et al. discovered that compared with HSC suspension culture alone (culture on top of a hydrogel), a coculture of HSCs with MSCs in a collagen hydrogel had a higher number of original HSCs in the presence of endosteal parts [136]. A functional large-pore PEG hydrogel scaffold developed by Raic et al. was used to recapitulate the 3D structure from the corresponding bone region, in which RGD was biofunctionalized to provide adhesive sites and MSCs were used as supporting stromal cells to promote the maintenance of HSPCs stemness [137]. Hydrogel-based MSCs 3D culture systems create a microenvironment with ECM proteins and integrins, promoting HSC maintenance and expansion. This system can be used to recapitulate the functional HSC niche and study the mechanism of HSCs fate regulation in vitro [138]. In addition, ECs are an important component of the retinal stem and progenitor cell (RSPC) niche. Aizawa et al. designed an agarose hydrogel to achieve the coculture of ECs and RSPCs and found that ECs inhibited the proliferation and differentiation of RSPCs [139]. Ding et al. used an injectable nanocomposite hydrogel to mimic the extracellular microenvironment and cocultured smooth muscle cells (SMCs) with MSCs in the system to promote cell migration and angiogenesis [140]. A recent study utilized NSCs-MSCs co-culturing hydrogel system to improve neuronal differentiation in vivo [141]. Han et al. co-cultured NSCs and ECs in chitosan (CS)-HA substrate to form a 3D-printed hydrogel, and indicated that the ECs in this system had enhanced angiogenic ability, which could be used for the personalized design of neurovasculature [142].

Oxygen concentration

The oxygen concentration in the ECM regulates stem cell behaviour. Furthermore, oxygen is necessary to ensure stem cell survival and achieve satisfactory therapeutic effects during stem cell therapy.

Thorpe et al. used a temperature-sensitive hydrogel system to cultivate human MSCs in a hypoxic environment (5% oxygen) to mimic the intervertebral disc microenvironment, with an observed effect on cell differentiation [143]. They found that the pore size of hydrogels increased under hypoxic conditions. The hypoxic hydrogel system accelerated human MSCs differentiation into nucleus pulposus cells in the absence of cartilage induction medium or other growth factors, thus restoring the mechanical function of intervertebral discs.

Studies have shown that oxygen constantly interacts with other factors to regulate stem cell behaviour and influence therapeutic efficacy. Xu et al. cultured MSCs with PNIPAM, a biodegradable and thermosensitive hydrogel containing bFGF, and established an angiogenesis-promoted environment in vitro [144]. The study found that bFGF released in vitro significantly improved the MSCs survival and paracrine effect under nutrition-deficient and hypoxic conditions (serum-free media and 1% oxygen). Cao et al. discovered that MSCs cultured in PEG hydrogels containing RGD displayed better chondrogenic differentiation under hypoxia (5% oxygen) than under normal oxygen (21% oxygen) [145].

In conclusion, hydrogel-based microenvironments regulate stem cell behaviour through ECM mechanics, ECM microstructure, cell–cell interactions, and oxygen concentration. In fact, the research mentioned above did not discuss the contribution from a single factor in the stem cell microenvironment but rather a consequence of the combination of multiple factors. Therefore, a thorough understanding about the stem cell microenvironment is urgently needed to achieve a better effect on stem cell expansion and function and to facilitate relevant clinical applications, such as tissue regeneration and drug screening.

Potential applications of engineered hydrogels in HSCs/HSPCs

Acquisition of haematopoietic stem cells for transplantation

HSCs are responsible for producing numerous haemocytes; however, disruption in this process can lead to a range of diseases, such as leukaemia and BM hypoplasia. HSCT is currently the only curative strategy for the treatment of patients with these fatal haematological malignancies [5, 146, 147]. HSCT was first proposed in the 1950 s by E. Donnall Thomas [148]. There are three main sources of HSCs for transplantation: autologous HSCs, allogeneic HSCs, and cord blood. HSCs from the host or matched donor are obtained first, followed by myelodepletion, and then HSCs are reinfused into the patient to rebuild the haemopoietic system and exert therapeutic efficacy. Studies have shown that the proportion and quantity of CD34+ HSCs are related prognosis. An infusion with a higher content of CD34+ HSCs improves the success rate of transplantation and patient survival [149]. Indeed, the CD34+ cell population consists of most haematopoietic progenitor cells and LT-HSCs with reserved haemopoietic potential.

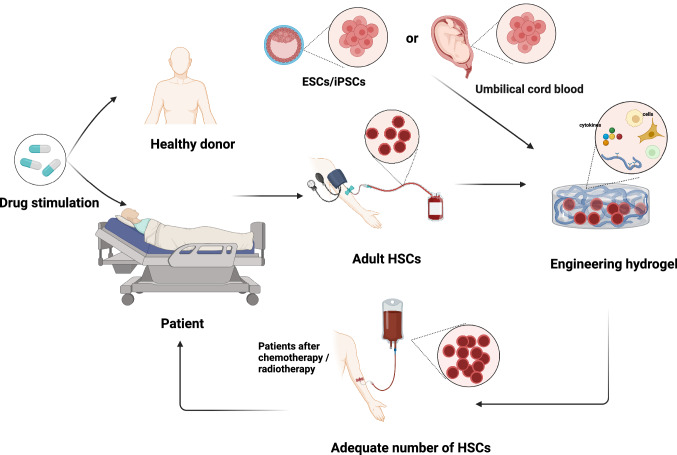

In fact, HSCT also faces challenges. Specifically, autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT) is confronted with a relatively higher risk of relapse, potentially due to failed HSC mobilization and functional deficiency inherited from the host, while allogeneic HSCT (allo-HSCT) struggles in the selection of HLA-matched donors and higher nonrelapse mortality (NRM) due to GVHD, which significantly affects the overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QOL) of patients [150]. Therefore, haploidentical stem cell transplantation (Haplo) and unrelated cord blood transplantation (UCBT) are novel alternative options to treat high-risk patients unresponsive to previous therapy or infirm patients who are intolerant to traditional intensive chemotherapy [151, 152]. Unfortunately, the main limitation lies with the low stem cell content in a single cord blood unit, which results in unresponsiveness and early relapse, hindering the broad application of UCBT. And the real clinical efficacy of Haplo and UCBT remains unclear due to insufficient patient numbers [153]. Therefore, promoting HSC expansion to obtain enough quantity is the key element to the successful application of HSCT (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic of HSC transplantation combined with hydrogel platform. HSCs are obtained by stimulated mobilization or cord blood separation. Then, sufficient HSCs can be obtained by an engineered hydrogel platform mimicking the HSC microenvironment in vitro, and the HSCs are transfused into patients. Created with BioRender.com

In addition to gene engineering, there are safer methods to expand HSCs with limited numbers into ideal quantities for clinical treatment. These methods use a hydrogel platform to mimic the HSCs microenvironment and selectively direct the differentiation of ESCs/iPSCs into HSCs or induce the expansion of adult HSCs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Potential applications of HSC-hydrogel systems

| Cell type | Materials | Factors | Potential application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse HSPCs | Lginate | Stiffness | Lin−/CD45+cells expansion | [101] |

| CB-CD34+ cell | PCL, PLGA, fibrin and collagen | Microstructure/cell–cell interactions | CB-CD34+ cell expansion and multilineage differentiation | [126] |

| Human HSCs | Notch ligand delta-like 1 (DL1) | Cellular ligands | HSC differentiation into T-cells | [131] |

| Human HSPCs | Collagen | Cell–cell interactions | HSPC expansion and lineage commitment | [136] |

| Human HSPCs | PEG | Cell–cell interactions /microstructure | HSPC from CB expansion and stemness maintenance | [137] |

| Human bone marrow-derived CD34+cells | Puramatrix gel | Cell–cell interactions/oxygen concentration/microstructure | HSC quiescence and stemness maintenance | [138] |

| Mouse ESCs | Agarose | Microstructure/cytokine | ESC differentiation into HSPCs | [154] |

| Mouse iPSCs | Peptides (RGD) | Microstructure/cytokine | iPSC-derived HSCs differentiation and HSCT | [155, 156] |

| Mouse HSPCs | GelMA | Stiffness/cell–cell interactions/oxygen concentration | HSPCs expansion and HSCT | [157, 158] |

| Human CD34+HSPCs | Poly(carboxybetaine acrylamide (CBAA)) |

Oxygen concentration /stiffness/microstructure |

LT-HSCs expansion and HSCT | [159] |

| CB-CD34+ cells | PAA | Microstructure/cytokine | HSPCs differentiation into functional platelets | [160] |

| Mouse HSPCs | PEG | Microstructure/cytokine/cellular ligands | HSPCs expansion and stemness maintenance | [161] |

| Circulating HSPCs (cHSPCs) in blood | Peptides (RGD) | Microstructure/cytokine | HSPCs expansion and HSCT | [162] |

PCL polycaprolactone, PLGA poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), PEG polyethylene glycol, GelMA gelatin methacrylate, PAA phenylazoaniline, CBAA carboxybetaine acrylamide

Directed differentiation of ESCs/iPSCs into HSCs

As a potential source of embryonic HSCs, pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) consisting of ESCs and iPSCs are often used to study the molecular mechanism of embryonic haematopoietic development. ESCs are derived from the enrichment of pluripotent cells capable of self-renewal from mouse or human blastocyst cell masses [163, 164]. ESCs are able to differentiate into endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm in vitro to generate various cell types, such as haematopoietic cells, neurons, cardiomyocytes, and intestine cells [164]. However, there is ethical and practical controversy with human embryonic stem cell research.

For the first time, Yamanaka and Takahashi successfully reprogrammed mouse embryonic fibroblasts into iPSCs by using four transcription factors (Sox2, Oct3/4, C-Myc and Klf4), which represents a major breakthrough in iPSC technology [165]. Furthermore, directed differentiation into HSCs from iPSCs and ESCs in vitro provides a feasible strategy for HSCs-based therapy for haematological malignancies [166]. At present, the application of HSCs derived from iPSCs/ESCs in vitro can be classified into three categories. The first is to induce the formation of a cystic-like structure as an embryoid body (EB). EBs can simulate temporal and spatial interactions among cells in normal embryonic development to induce germ-layer differentiation [164]. Elizabeth S et al. form EBs and generated approximately 500 haematopoietic progenitors from a single human ESC in serum-free culture supplemented with haematopoietic factors [167]. Similarly, Ye et al. induced EBs from myeloproliferative disorder (MPD)-human iPSCs in the same way as the successful generation of CD45+CD34+ HSPCs, which provided a model for studying the pathogenesis of MPD [168]. In addition, a co-culture of ESCs/iPSCs with feeder cells also induced HSC generation. BM-derived stromal cells in the AGM region are able to promote haematopoietic differentiation of mouse and human ESCs by secreting cytokines [169]. Weisel et al. first co-cultured mouse ES cells with OP9 cells and the supernatant was further added into the culture of AGM stromal cells on Day 9 or 11 [170]. The results showed that this system significantly promoted the production of HSPCs. Demirci et al. induced the differentiation of ESCs into EBs with centrifugation and serum-free culture and then cocultured them with OP9 [171]. After 10 days, the proportion of HSPCs was 7.6–8.9%. ECM coating with collagen, laminin or fibronectin induces ESCs differentiation into mesoderm and accelerates the generation of C-kit+CD45+ HSCs [172]. In addition, NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated production of interleukin 1-β (IL-1β) stimulates the differentiation of human iPSCs into HSPCs [173]. In conclusion, the novel technology with induction of haematopoietic differentiation from iPSCs/ESCs in vitro reveals the importance of the extracellular microenvironment in the regulation of HSC function.

Engineered hydrogels provide artificial niches and microenvironments with a combination of iPSCs/ESCs in vitro that can effectively control cytokine and protein release. Rahman et al. stimulated ESCs differentiation into HSPCs with immobilized VEGFA in serum-free 3D agarose, which is better than soluble VEGFA [154]. However, in one study, researchers speculated that the effective induction of iPSCs to produce transplantable CD34+ haematopoietic cells may be restrained by the nonphysiological haematopoietic niche [155]. To address this problem, they used a custom-synthesized hydrogel to improve the microenvironment for haematopoietic differentiation with coculture of mouse iPSCs and OP9 cells, and successfully generated CD34+ HSCs with stemness and the ability of multipotential differentiation, which could be used for haematopoietic reconstruction after transplantation. Similarly, Shan et al. achieved the same results by using a self-assembled polypeptide hydrogel system to culture EBs [156]. They found the 3D hydrogel coculture of OP9 cells to be better at inducing a higher proportion of CD201+c-Kit+ cells and differentiation of ESCs into HSPCs than the 0.1% gelatine system, with the notch signalling pathway involved in the process [174].

Maintenance and expansion of adult HSCs

The expansion of HSCs is a key aspect related to the clinical efficacy of HSCT for the treatment of haematological diseases [175]. Studies have confirmed the possibility of direct reprogramming of somatic cells into iPSCs and then into HSCs. However, most transcription factors related to the generation of HSCs during this process also participate in leukemogenesis. Therefore, there is a risk of malignant transformation with the iPSCs system [176].

In vitro simulation of the HSC microenvironment can increase the content of HSCs and maintain the stemness of HSCs without malignant transformation. Adult HSCs mainly exist in the BM microenvironment under Young’s modulus of 0.25–24.7 kPa [39]. Since the major challenge for HSCT application lies in the compromised long-term haematopoiesis, the hydrogel platform mimics HSC niche and provides stimulative signals in the microenvironment to promote the expansion of HSCs and HSPCs populations without the cost of exhaustion of HSC subpopulations at rest. For example, MSCs paracrine factors such as CXCL12, IL-6, and TPO mediate the stasis and differentiation of HSCs [177].

MSCs in the HSC niche play important roles in the regulation of HSCs expansion and differentiation. The hydrogel system encapsulates HSCs and MSCs together in coculture, which maintains the high activity and expansion of HSCs. Gilchrist et al. cocultured HSPCs and BM-MSCs at different ratios by using a biodegradable acrylamide-functionalized gelatine hydrogel [157]. They found that a small mesh constrained secreted biomolecules in HSCs-MSCs cocultures, affecting autocrine signalling. However, as the mesh size increased, autocrine feedback was reduced, and paracrine signalling began to dominate cell–cell interactions. When the ratio of HSPCs: MSCs was 1:1 at high stiffness (4.80 ± 0.3 kPa), the number of HSPCs could be maintained for more than 7 days, which promoted the retention of the stationary HSCs (G0) population [158]. The expansion of HSCs was clearly improved by coculture with MSCs in a microenvironment at a high density. The team next modified the hydrogel system to effectively avoid ROS production by substituting crosslinking agents with adjustable biophysical properties, intrinsic cellular interaction motifs, and bioactive crosslinking characteristics for conjugation.

In addition to 3D culture, the recent development of amphoteric hydrogels also enhances the expansion or stemness maintenance of HSPCs. Bai et al. developed a biodegradable zwitterionic hydrogel to culture human CD34+ HSPCs derived from cord blood and the BM [159]. Within the study, the LT-HSCs expanded 73 times with retained potential for multidirectional differentiation. The transplanted cells in immunodeficient NOD- scid IL-2 receptor subunit gamma (IL2rg) (null) (NSG) mice rebuilt haematopoietic system with an excellent 24-week implantation rate. The hydrogel system might also reduce the production of excessive ROS by inhibiting oxygen-related metabolism. Thus, reduced energy production in HSCs tends to maintain stemness rather than induce differentiation, providing a new approach for the effective amplification of HSCs by hydrogels.

Cytokines can also be added to hydrogels in vitro to promote the expansion or induce directed HSC differentiation. Sullenbarger et al. designed a one-way 3D perfusion bioreactor system to cultivate CD34+ cells from umbilical cord blood by using polyacrylamide hydrogel scaffolds [160]. They successfully induced HSPCs differentiation with only cytokines rather than the cell feeding layer and established the continuous production of functional platelets. However, the generated platelets seemed to be already activated and less responsive to stimulus. Alternatively, Pietrzyk-nivau et al. focused on promoting megakaryocyte differentiation to increase functional platelet production and investigated intrinsic mechanisms [178]. The 3D hydrogel improved mature megakaryocyte enlargement with increased platelet production under flow conditions. Cuchiara et al. covalently fixed RGDs, SCF, and SDF-1α on PEG-DA hydrogels to effectively control the adhesion and diffusion of the 32D haematopoietic cell line in vitro [179]. Subsequently, Cuchiara et al. found that SCF and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) covalently fixed to a PEG hydrogel achieved significant amplification of HSPCs with maintained stemness [161]. Recently, Xu et al. used a self-assembled 3D polypeptide RGD hydrogel system combined with traditional haematopoietic growth factors (SCF, TPO, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3 L), IL-3, and IL-6) and VEGF, and significantly increased the number of rare circulating HSPCs in the peripheral blood [162]. The results demonstrated that the amplified HSPCs maintained long-term self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation potential.

Conclusions and future perspectives

In conclusion, we summarized the landscape of hydrogel-based engineering system for providing necessary factors to mimic in vivo microenvironment of HSCs, which is beneficial to promote the acquisition of functional HSCs. Acquisition of sufficient HSCs with physiological function is fundamental to the extensive clinical application of HSCT. The ability of HSC self-renewal and differentiation is the combinational results of multiple regulatory factors in the microenvironment. Hydrogel materials provide a platform in vitro for the comprehensive action of various factors, and therefore they can systemically and accurately mimic the complex HSC microenvironment in vivo in regarding mechanical strength, space dimensionality, cell adhesion, cellular interaction, and oxygen concentration, thus realizing the acquisition of functional HSCs within defined purpose. Meanwhile, they also provide a platform to study the different contributions of a single regulatory factor during the process of HSC expansion ex vivo, and therefore promoting the clinical translations of HSCT.

However, ex vivo expanding of HSCs while maintaining their long-term repopulating capacity needed for clinical applications remains challenging. In this context, biodegradable components such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), which could support long-term ex vivo HSC expansion allow nonconditioned transplantation, can serve as an alternative anchor for other bioactive agents to support HSC survival and phenotypic maintenance in vitro so that avoiding extensive chemoradiotherapy precondition before transplantation.in patients. Although accumulating studies have highly confirmed the value of hydrogel-culturing system for HSC expansion and maintenance, most researches are based on murine models, and further explorations warranted in primate models would provide better understandings about the cellular and molecular mechanisms to move forward clinical applications.

Overall, the articles reviewed above are still in its infancy, and unknown fields remain to be further explored, especially for biocompatibility. Excitingly, the technology of freeze-tine, electrospinning, selective laser volume, and 3D cell printing have significantly advanced the development of synthetic hydrogels to artificially adjust the microenvironmental parameters during the culture. These strategies combined with high-resolution imaging and single-cell sequencing facilitate the study of cellular and molecular mechanisms behind the regulation of HSC self-renewal and differentiation. Hopefully, engineered hydrogels as a suitable platform for mimicking HSC niche in vitro are expected to produce functional HSCs for clinical applications in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Core Facilities, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Author contributions

MZ and QW: contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, visualization and writing—original draft preparation, MZ and QW: literature searching and summary, MZ, TG, YH, XZ, JXL and JD: Funding acquisition, HH: conceptualization, reviewing and supervision, PXQ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

P.Q. is supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1103500, 2018YFA0109300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82222003, 81870080, 91949115, 82161138028), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19H080001), the Leading Innovative and Entrepreneur Team Introduction Program of Zhejiang (2020R01006). Q.W. is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82000149), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ21H180006), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (CPSF) (2021M702853).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Meng Zhu and Qiwei Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

He Huang, Email: huanghe@zju.edu.cn.

Pengxu Qian, Email: axu@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Mcculloch JETA. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14(2):213–222. doi: 10.2307/3570892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman IL. Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell. 2000;100(1):157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4(1–2):7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Therapies., F.w.a.s.c (2017) US Food & Drug Administration https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm286155.htm

- 5.Choi JS, Mahadik BP, Harley BA. Engineering the hematopoietic stem cell niche: frontiers in biomaterial science. Biotechnol J. 2015;10(10):1529–45. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel MG, et al. Making a hematopoietic stem cell. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(3):202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang G, et al. Enhancing efficacy of stem cell transplantation to the heart with a PEGylated fibrin biomatrix. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(6):1025–1036. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu J, et al. The use of human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in RGD modified alginate microspheres in the repair of myocardial infarction in the rat. Biomaterials. 2010;31(27):7012–7020. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkola HK, Orkin SH. The journey of developing hematopoietic stem cells. Development. 2006;133(19):3733–3744. doi: 10.1242/dev.02568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fau MM, Metcalf D, Metcalf D. Ontogeny of the haemopoietic system: yolk sac origin of in vivo and in vitro colony forming cells in the developing mouse embryo. Br J Haematol. 1970;18(3):279–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1970.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanovs A, et al. Highly potent human hematopoietic stem cells first emerge in the intraembryonic aorta-gonad-mesonephros region. J Exp Med. 2011;208(12):2417–2427. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinney-Freeman SL, et al. Surface antigen phenotypes of hematopoietic stem cells from embryos and murine embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2009;114(2):268–278. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-193888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferkowicz MJ, et al. CD41 expression defines the onset of primitive and definitive hematopoiesis in the murine embryo. Development. 2003;130(18):4393–4403. doi: 10.1242/dev.00632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ema M, et al. Primitive erythropoiesis from mesodermal precursors expressing VE-cadherin, PECAM-1, Tie2, endoglin, and CD34 in the mouse embryo. Blood. 2006;108(13):4018–4024. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-012872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou F, et al. Tracing haematopoietic stem cell formation at single-cell resolution. Nature. 2016;533(7604):487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature17997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Q, et al. Developmental trajectory of prehematopoietic stem cell formation from endothelium. Blood. 2020;136(7):845–856. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020004801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pietras EM, Warr Mr Fau E, Passegué E. Cell cycle regulation in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Biol. 2011;195(5):709–720. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson A, Trumpp A. Bone-marrow haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(2):93–106. doi: 10.1038/nri1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szilvassy SJ, et al. Quantitative assay for totipotent reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells by a competitive repopulation strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(22):8736–8740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cullen SM, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell development: an epigenetic journey. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2014;107:39–75. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416022-4.00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonig H, Papayannopoulou T. Hematopoietic stem cell mobilization: updated conceptual renditions. Leukemia. 2013;27(1):24–31. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiel MJ, et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121(7):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notta F, et al. Isolation of single human hematopoietic stem cells capable of long-term multilineage engraftment. Science. 2011;333(6039):218–221. doi: 10.1126/science.1201219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry JM, Li L. Functional assays for hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;636:45–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-691-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Challen GA, et al. Mouse hematopoietic stem cell identification and analysis. Cytometry A. 2009;75(1):14–24. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Galen P, et al. The unfolded protein response governs integrity of the haematopoietic stem-cell pool during stress. Nature. 2014;510(7504):268–272. doi: 10.1038/nature13228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu MJ, et al. Stimulation of mouse and human primitive hematopoiesis by murine embryonic aorta-gonad-mesonephros-derived stromal cell lines. Blood. 1998;92(6):2032–2040. doi: 10.1182/blood.V92.6.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohneda O, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and differentiation are supported by embryonic aorta-gonad-mesonephros region-derived endothelium. Blood. 1998;92(3):908–919. doi: 10.1182/blood.V92.3.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsarovina K, et al. Essential role of Gata transcription factors in sympathetic neuron development. Development. 2004;131(19):4775–4786. doi: 10.1242/dev.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriguchi T. Development and carcinogenesis: roles of GATA factors in the sympathoadrenal and urogenital systems. Biomedicines. 2021 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9030299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maestroni GJM. Adrenergic modulation of hematopoiesis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020;15(1):82–92. doi: 10.1007/s11481-019-09840-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou S, Flygare J, Lodish HF. Fetal hepatic progenitors support long-term expansion of hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2013;41(5):479–490.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan JA, et al. Fetal liver hematopoietic stem cell niches associate with portal vessels. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2016;351(6269):176–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y, et al. ATF4 plays a pivotal role in the development of functional hematopoietic stem cells in mouse fetal liver. Blood. 2015;126(21):2383–2391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nombela-Arrieta C, et al. Quantitative imaging of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell localization and hypoxic status in the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):533–543. doi: 10.1038/ncb2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendez-Ferrer S, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466(7308):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunisaki Y, et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;502(7473):637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jansen LE, et al. Mechanics of intact bone marrow. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2015;50:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi JS, Harley BAC. Marrow-inspired matrix cues rapidly affect early fate decisions of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Sci Adv. 2017;3(1):e1600455. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chitteti BR, et al. Modulation of hematopoietic progenitor cell fate in vitro by varying collagen oligomer matrix stiffness in the presence or absence of osteoblasts. J Immunol Methods. 2015;425:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee-Thedieck C, et al. Impact of substrate elasticity on human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell adhesion and motility. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(16):3765–3775. doi: 10.1242/jcs.095596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holst J, et al. Substrate elasticity provides mechanical signals for the expansion of hemopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1123–1128. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huebsch N, et al. Matrix elasticity of void-forming hydrogels controls transplanted-stem-cell-mediated bone formation. Nat Mater. 2015;14(12):1269–1277. doi: 10.1038/nmat4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamo L, et al. Biomechanical forces promote embryonic haematopoiesis. Nature. 2009;459(7250):1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature08073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma Y, et al. 3D spatiotemporal mechanical microenvironment: a hydrogel-based platform for guiding stem cell fate. Adv Mater. 2018;30(49):e1705911. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brizzi MF, Tarone G, Defilippi P. Extracellular matrix, integrins, and growth factors as tailors of the stem cell niche. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24(5):645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Legate KR, Wickstrom Sa Fau R, Fassler R. Genetic and cell biological analysis of integrin outside-in signaling. Genes Dev. 2009;23(4):397–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.1758709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfaff M. Recognition sites of RGD-dependent integrins. In: Eble JA, editor. Springer. US; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. RGD modified polymers biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4385–4415. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang CC, Lodish HF. Murine hematopoietic stem cells change their surface phenotype during ex vivo expansion. Blood. 2005;105(11):4314–4320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ciofani M, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Notch promotes survival of pre-T cells at the beta-selection checkpoint by regulating cellular metabolism. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(9):881–888. doi: 10.1038/ni1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobayashi H, et al. Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(11):1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/ncb2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reya T, et al. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423(6938):409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamazaki S, et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2011;147(5):1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cortes M, et al. Developmental vitamin D availability impacts hematopoietic stem cell production. Cell Rep. 2016;17(2):458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suda T, Takubo K, Semenza G. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(4):298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding L, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature. 2013;495(7440):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugiyama T, et al. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25(6):977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Little L, Healy KE, Schaffer D. Engineering biomaterials for synthetic neural stem cell microenvironments. Chem Rev. 2008;108(5):1787–1796. doi: 10.1021/cr078228t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taichman RS, Reilly MJ, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support human hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro bone marrow cultures. Blood. 1996;87(2):518–524. doi: 10.1182/blood.V87.2.518.bloodjournal872518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425(6960):836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber JM, Calvi LM. Notch signaling and the bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell niche. Bone. 2010;46(2):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z, et al. A role for macrophages in hematopoiesis in the embryonic head. Blood. 2019;134(22):1929–1940. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018881243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Butler JM, et al. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(3):251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pinho S, et al. PDGFRα and CD51 mark human nestin+ sphere-forming mesenchymal stem cells capable of hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion. J Exp Med. 2013;210(7):1351–1367. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshida S, et al. Redox regulates mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity by modulating the TSC1/TSC2-Rheb GTPase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32651–32660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.238014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shin SY, et al. Hydrogen peroxide negatively modulates Wnt signaling through downregulation of β-catenin. Cancer Letters. 2004;212(2):0–231. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jang YY, Sharkis SJ. A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood. 2007;110(8):3056–3063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-087759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kocabas F, et al. Hypoxic metabolism in human hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Biosci. 2015;5:39–39. doi: 10.1186/s13578-015-0020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shen J, et al. Single-cell transcriptome of early hematopoiesis guides arterial endothelial-enhanced functional T cell generation from human PSCs. Sci Adv. 2021;7(36):9787–9787. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abi9787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lutolf MP. Spotlight on hydrogels. Nat Mater. 2009;8(6):451–453. doi: 10.1038/nmat2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsou YH, et al. Hydrogel as a bioactive material to regulate stem cell fate. Bioacti Mater. 2016;1(1):39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim J, et al. Bone regeneration using hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel with bone morphogenic protein-2 and human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28(10):1830–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Currao M, et al. Hyaluronan based hydrogels provide an improved model to study megakaryocyte-matrix interactions. Exp Cell Res. 2016;346(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nicodemus GD, Bryant SJ. Cell encapsulation in biodegradable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14(2):149–165. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xue X, et al. Fabrication of physical and chemical crosslinked hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Bioact Mater. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xue SW, Hoffman AS, Yager P. Synthesis and characterization of thermally reversible macroporous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels. J Polym Sci Polym Chem. 1992;30(10):2121–2129. doi: 10.1002/pola.1992.080301005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boustta M, et al. Versatile UCST-based thermoresponsive hydrogels for loco-regional sustained drug delivery. J Control Release. 2014;174:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Berger J, et al. Structure and interactions in covalently and ionically cross-linked Chitosan hydrogels for biomedical applications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;57(1):19–34. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(03)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mironi-Harpaz I, et al. Photopolymerization of cell-encapsulating hydrogels: crosslinking efficiency versus cytotoxicity. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(5):1838–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]