Abstract

The human gene encoding α1-antitrypsin (α1AT, gene symbol PI) resides in a cluster of serine protease inhibitor (serpin) genes on chromosome 14q32.1. α1AT is highly expressed in the liver and in cultured hepatoma cells. We recently reported the chromatin structure of a >100 kb region around the gene, as defined by DNase I-hypersensitive sites (DHSs) and matrix-attachment regions, in expressing and non-expressing cells. Transfer of human chromosome 14 by microcell fusion from non-expressing fibroblasts to rat hepatoma cells resulted in activation of α1AT transcription and chromatin reorganization of the entire region. In the present study, we stably introduced cosmids containing α1AT with various amounts of flanking sequence and a linked neo selectable marker into rat hepatoma cells. All single-copy transfectants with >14 kb of 5′ flanking sequence expressed wild-type levels of α1AT mRNA in a position-independent manner. In contrast, expression of transgenes containing only ∼1.5–4 kb of flanking sequence was highly variable. Long-term culture of transfectant clones in the absence of selection resulted in gradual loss of neo expression, but expression of the linked α1AT gene remained constant. DHS mapping of cosmid transgenes integrated at ectopic sites revealed a hepatoma-specific chromatin structure in each transfectant clone. The implications of these findings are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The gene encoding human α1-antitrypsin (α1AT, gene symbol PI) resides in a cluster of serine protease inhibitor (serpin; for review see 1) genes on chromosome 14q32.1. This ∼320 kb gene cluster also includes the genes encoding α1-antichymotrypsin (AACT), protein C inhibitor (PCI), kallistatin (KAL, gene symbol PI4), corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG) and an antitrypsin-related pseudogene (ATR, gene symbol PIL) (2–4). The six genes are organized into two discrete subclusters of three genes, which have similar genomic organizations. The proximal (α1AT-ATR-CBG) and distal (KAL-PCI-AACT) subclusters are separated by ∼170 kb of genomic DNA (5).

The serpin genes at 14q32.1 are expressed in a tissue-specific manner: they are all highly expressed in liver and cultured hepatoma cells, but they are transcriptionally repressed in most cell types. Other cells, such as monocytes/macrophages and intestinal epithelial cells, express some but not all of the serpin genes in the cluster (6,7). Therefore, these genes provide a useful model system to study the cell-specific regulation of gene activity and chromatin structure in a large genomic region.

Mechanisms that regulate gene activity and chromatin structure seem to be intimately linked (for reviews see 8–14). To explore these mechanisms within the serpin cluster, we began by characterizing the chromatin structure of an ∼130 kb region around α1AT-ATR-CBG. To do this, we mapped DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) and matrix-attachment regions (MARs) in the region extending from ∼25 kb upstream of α1AT to ∼20 kb downstream of CBG in expressing and non-expressing cells. DHSs are often located at important cis-regulatory elements (15,16), and MARs may be important determinants of individual chromatin domains (for reviews see 17,18).

The α1AT-ATR-CBG region contains five MARs. There is a strong matrix-binding element ∼16 kb upstream of α1AT, three MARs are located between ATR and CBG, and one MAR is within CBG intron 1 (19). These MARs were matrix-associated in all cell types tested. In contrast, most of the DHSs in this region were cell-specific: there were 29 DHSs in expressing cells, but only seven of these sites were found in non-expressing cells. Furthermore, when human chromosome 14 was transferred from non-expressing to expressing cells by microcell fusion, human α1AT and CBG gene expression was activated, and the chromatin structure of the entire locus was reorganized to an expressing cell-typical state (20). Both gene activation and chromatin remodeling required hepatocyte nuclear factors-1α and -4 (HNF-1α and HNF-4) (21). These data indicate that the terminally differentiated recipient cells used in these chromosome transfer experiments contained all the trans-acting regulatory factors necessary for both the establishment and the maintenance of cell-specific patterns and gene activity and chromatin structure (19,20). As such, this provides a basis for functional analysis of the locus by targeted mutagenesis using recombination-proficient microcell hybrids (22).

The data summarized above indicate that the human α1AT gene is expressed in a stable, cell-specific manner when the locus is transferred to rat hepatoma recipient cells by microcell fusion, that is, when the human α1AT gene is in its normal chromosomal context. In contrast, stably integrated transgenes are generally expressed at highly variable levels, presumably due to transgene rearrangements and/or chromosomal position effects at the sites of transgene insertion (23–28). In this study, we determined the expression patterns and chromatin organizations of large (∼40 kb) α1AT transgenes that were stably integrated at ectopic chromosomal sites. To do this, human α1AT cosmids containing various amounts of 5′ flanking sequence linked to a dominant selectable marker (neo) were transfected into rat hepatoma cells by electroporation. Transfectant clones were isolated, and the expression phenotypes of single copy transfectants were compared. Transgenes with large (∼14–24 kb) 5′ flanking regions were highly expressed in the hepatoma transfectants, and α1AT gene expression was position-independent. In contrast, expression of similarly sized transgenes with less 5′ flanking DNA was more variable. α1AT expression in six different clones tested was stable in the absence of selection, although expression of the linked neo marker was not. DHS mapping experiments indicated that all transgenes tested displayed expressing cell-typical patterns of DHSs. These data suggest that α1AT transgenes recapitulate at least some aspects of the regulation of the normal chromosomal allele.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions

Fao-1 is a hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase-deficient, ouabain-resistant rat hepatoma cell line derived from H4IIEC3 (29). The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 and the cervical carcinoma line HeLa S3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). F(14n) series microcell hybrids were prepared by transferring human chromosome 14 from HDm-5, a mouse fibroblast (3T6) that contains a neo-marked human chromosome 14 derived from diploid fibroblasts (30), to Fao-1 rat hepatoma cells, as described (20,31). R(14n)6 was prepared similarly by transferring human chromosome 14 from HDm-5 to Rat-2 rat fibroblasts. All cells were grown in 1:1 Ham’s F12:Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (F/DV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD). F(14n) microcell hybrids and R(14n)6 cells were grown in medium containing 250 µg/ml G418.

Cosmid transfections

The various cosmids containing different parts of the human α1AT-ATR region were subcloned from YAC305a11 from the CEPH library (32), as described (5). The SuperCos1 vector used (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) contained a neo expression cassette under the control of the SV40 promoter, allowing selection in mammalian cells. Transfections into Fao-1 rat hepatoma cells were performed as follows: exponentially growing Fao-1 cells (∼1.2 × 107 cells/transfection) were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold F/DV, and ∼12 µg of MluI- or PvuI-linearized cosmid DNA was added. The cells were electroporated at 960 µF and 300 V using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (Hercules, CA). After ∼30 h in non-selective medium (F/DV + 10% FBS), 500 µg/ml G418 were added, and pools or individual clones were picked after ∼3 weeks and expanded.

RNA and DNA blot hybridizations

Cytoplasmic RNAs were isolated from the cells and analyzed on 1.2% agarose–formaldehyde gels as described (20). The different probes used were: α1AT, a 567 bp BamHI–DraI fragment from cosmid αATc1 (33) which contained most exon II of human α1AT; this probe did not cross-hybridize with rat α1AT mRNA. As loading controls, intensities of the ethidium bromide-stained ribosomal RNA bands were compared. Alternatively, filters were stripped and rehybridized with a rat cyclophilin cDNA probe (34). The neo probe was an ∼1.3 kb StuI–SmaI fragment from cosmid vector SuperCos1.

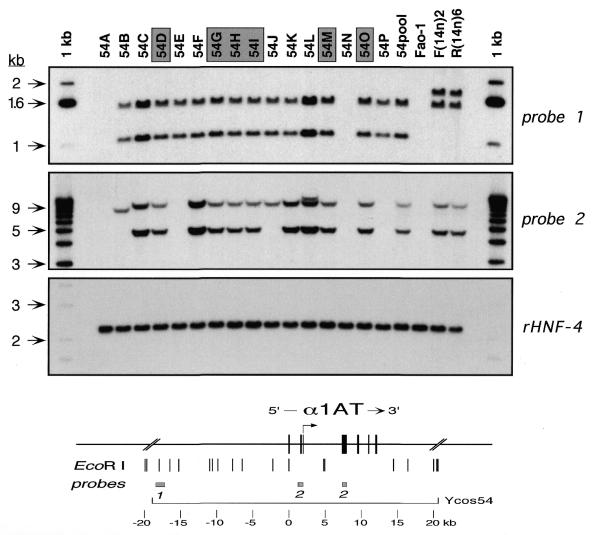

Genotypic analyses of the various transfectant clones were performed by Southern hybridization as described (20), using a variety of unique probes from the α1AT-ATR region. All probes were isolated from a collection of plasmid subclones derived from individual cosmids as described (5,35). For example, in Figure 2, probe 1 was an ∼1.1 kb HindIII–NcoI fragment isolated from an ∼8.6 kb HindIII subclone (19) from Ycos117 (5); probe 2 was a mixture of an ∼0.7 kb SphI–BamHI and a 567 bp BamHI–DraI fragment containing most of α1AT exon II. The rHNF-4 probe was an ∼1.1 kb SphI–BamHI fragment from pLEN4S (36) containing 3′ untranslated sequences of rat HNF-4 cDNA.

Figure 2.

Genotypic analysis of Ycos54 transfectants. Genomic DNAs from individual cosmid transfectants (54A, 54B, etc.) and from a polyclonal mixture of approximately 30 clones (54pool) were prepared, and 5 µg of each were digested with EcoRI. The restriction digests were analyzed by Southern hybridization using various probes in and around the human α1AT gene, as well as with a control rat probe (rHNF-4). Control DNAs were prepared from untransfected rat hepatoma cells (Fao-1) and from rat hepatoma [F(14n)2] or fibroblast [R(14n)6] microcell hybrids containing human chromosome 14. The map at the bottom of the figure shows the human α1AT gene with the hepatocyte-specific transcription start site (arrow) and relevant flanking sequences, including genomic EcoRI sites and the locations of probes 1 and 2. These probes are described in Materials and Methods. The rHNF-4 probe was an ∼1.1 kb SphI–BamHI fragment from pLEN4S (36) containing 3′ untranslated sequences of rat HNF-4 cDNA. Shaded boxes over individual transfectants indicate clones that contained single copy, intact transgenes. Arrows beside the gels show the positions (in kb) of size markers (1 kb ladder).

DNase I hypersensitive site mapping

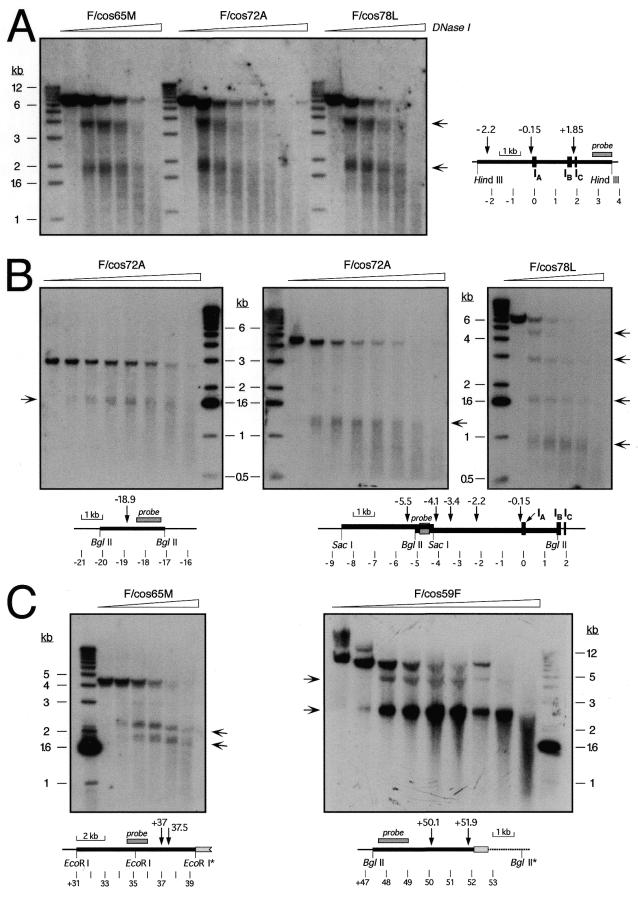

Nuclei from the various cell lines were isolated and digested with increasing concentrations of DNase I. Genomic DNAs were purified, digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme, and analyzed by Southern hybridization using a variety of unique-sequence probes from the α1AT-ATR region, as described (20,21). The same range of DNase I concentrations was used for each cell line. The following probes were used for the experiments shown in Figure 5: an ∼0.9 kb SpeI–HindIII fragment from, approximately, map position +3 kb (Fig. 5A); an ∼1.1 kb HindIII–NcoI fragment (approximately position –18 kb; Fig. 5B, left); an ∼0.4 kb HindIII–ClaI fragment (approximately position –4.7 kb; Fig. 5B, center and right); an ∼1.4 kb ScaI–TaqI fragment (approximately position +35 kb; Fig. 5C, left), and an ∼1.4 kb SacI fragment (approximately position +48 kb; Fig. 5C, right). Most DHSs were mapped using two or more different combinations of probes and/or restriction enzymes, as described (20). Usually, samples from expressing and non-expressing control cell lines were analyzed in parallel.

Figure 5.

DNase I-hypersensitive site mapping in cosmid transfectants. Nuclei from the indicated single-copy, intact cosmid transfectants were treated with increasing concentrations of DNase I. DNA was purified, digested with HindIII (A), BglII (B, left and right; C, right), SacI (B, center), or EcoRI (C, left) and analyzed by Southern hybridization using specific probes around α1AT described in Materials and Methods. The diagrams indicate the positions of relevant restriction sites, DHSs, probes and α1AT exons, using as coordinate zero an EcoRI site in the middle of exon IA of α1AT. Light gray boxes in (C) indicate a fragment of the SuperCos1 vector at the 3′ end of the transgene, and restriction sites with an asterisk are either in the vector or at the integration site of the cosmid in the rat genome. The ∼4.1 kb EcoRI fragment without DHSs (C, left; approximately position +31 to +35.1 kb) only hybridized weakly to the probe used, and is barely visible below the stronger ∼4.3 kb fragment recognized by the probe. Arrows beside the autoradiographs indicate the positions of sub-fragments generated by DNase I cleavage at specific DHSs. A 1 kb ladder was used as a size standard, and the positions of diagnostic bands are indicated beside the autoradiographs.

RESULTS

Transfection of human α1AT cosmids into Fao-1 rat hepatoma cells

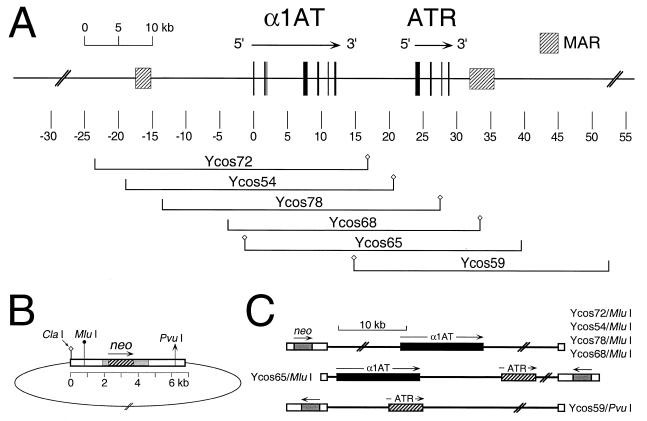

Microcell transfer of a neo-tagged human chromosome 14 from non-expressing fibroblasts to Fao-1 rat hepatoma cells results in activation of human α1AT transcription to high, recipient cell-typical levels (20). To determine whether α1AT cosmid transgenes might be expressed in a similar manner, we transfected six different, similarly sized cosmids into Fao-1 cells by electroporation. Five of these cosmids contained the complete α1AT coding region, plus various amounts of 5′ and 3′ flanking DNA (Fig. 1A). Ycos72 contained ∼24 kb of 5′ flanking DNA. Ycos54 and Ycos78 contained ∼19 and ∼14 kb of 5′ flanking DNA, respectively, and they differed primarily by the presence or absence of the α1AT 5′ MAR (19). Ycos68 and Ycos65 contained <5 kb of 5′ flanking DNA. Ycos59 did not contain α1AT coding sequences, but it did contain ATR and DNA sequences extending ∼26 kb downstream. The SuperCos vector used to isolate these cosmids contained the bacterial aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene (Fig. 1B, neo, hatched box) under the control of SV40 regulatory sequences (gray boxes), thus allowing selection in mammalian cells. Prior to transfection, the cosmids were linearized with either PvuI (Ycos59) or MluI (others). The positions and orientations of the neo and α1AT transcription units in these linear DNA molecules, and in presumptive single copy integrants, are shown in Figure 1C.

Figure 1.

Genomic map of the α1AT region and cosmids used in this study. (A) Physical map of the α1AT-ATR region. The map is drawn to scale, with position zero defined as an EcoRI site in macrophage-specific exon IA of α1AT (5,35). Exons are indicated by black boxes, and MARs as hatched boxes. The positions and names of relevant cosmids used in this study are shown below the map. Small diamonds on either side of the genomic inserts represent the diagnostic ClaI site of the cosmid vector. (B) Schematic representation of the SuperCos1 vector ligated to a genomic insert. White boxes indicate λ or plasmid sequences. The bacterial aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (neo) gene (hatched box) is under the control of SV40 promoter and polyadenylation signals (gray boxes). Relevant restriction sites used to determine insert orientations and/or to linearize constructs for electroporation are indicated. (C) Diagrammatic representation of various linearized cosmid clones, showing the presumptive genomic organization of single-copy, intact integrants. The relative positions and orientations of neo (gray boxes) and α1AT (black boxes) and/or ATR (hatched boxes) in the various linearized templates are indicated.

Genotypic analysis of cosmid transfectants

The six cosmids (Fig. 1A) were transfected into Fao-1 cells by electroporation, and pools and individual clones were isolated and expanded for analysis. Genomic DNAs from the cells were prepared and analyzed by Southern hybridization to determine copy number and integrity of the cosmid transgenes. An example of this analysis for Ycos54 transfectants using two different probes is shown in Figure 2. Untransfected rat hepatoma cells (Fao-1) were used as a negative control, and rat hepatoma [F(14n)2] (31) and fibroblast [R(14n)6] (20) microcell hybrids containing human chromosome 14 served as positive controls.

Only a subset of the transfectant clones contained intact transgenes. Rearrangements and/or deletions were observed in six of the 16 clones analyzed. As the precise arrangements of transgene sequences in such transfectants are difficult or impossible to determine, these clones are useless for genotype/phenotype correlations. Furthermore, transfectants with transgene rearrangements constituted nearly 40% of the clones in this experiment, so analyses of polyclonal mixtures of transfectant clones would be expected to be similarly uninformative. These considerations have often been disregarded in the interpretation of the phenotypes of stable transfectants.

A variety of transgene rearrangements were observed in the Ycos54 transfectants. For example, transfectants 54A and 54N had deleted virtually all α1AT sequences (Fig. 2 and data not shown), and retained just enough of the cosmid vector to allow expression of the selected neo marker. Other clones had deletions of α1AT coding regions, but contained upstream sequences (Fig. 2; 54E and 54P). Using the probes shown in Figure 2, 10 of the 16 transfectant clones appeared to contain intact transgenes (Fig. 2; 54C, 54D, 54F, 54G, 54H, 54I, 54K, 54L, 54M and 54O).

To assess transgene copy number in individual transfectant clones, the filters used in the Southern hybridizations were stripped and rehybridized with a probe to rat HNF-4 (Fig. 2, panel rHNF-4), and band intensities among the various α1AT- and HNF-4-hybridizing fragments were compared. As shown in Figure 2, it was readily apparent that four of the 16 transfectant clones contained multiple copies of the α1AT transgene (Fig. 2; 54C, 54F, 54K and 54L).

Similar genotypic analyses were performed on clones obtained by transfecting the five other α1AT cosmids (Fig. 1; Ycos59, Ycos65, Ycos68, Ycos72 and Ycos78) into Fao-1 cells (data not shown). The distributions of clones with single copy, intact transgenes, multiple copy insertions, and deletions and/or rearrangements of α1AT coding sequences (as assessed by the absence of one or both EcoRI fragments that hybridized with probe 2; Fig. 2) are summarized in Table 1. Transfectant clones with single copy, intact transgenes generally constituted only ∼25–50% of the clones. The Ycos59 transfectants, containing human ATR but not α1AT (Fig. 1), were used in DHS mapping experiments (below) but not for phenotypic tests; these clone are not included in Table 1.

Table 1. Transgene genotypes of cosmid transfectants.

| Cosmid transfecteda | Number of clones | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-copy | Multi-copy | Rearranged | Total | |

| Ycos72 (23.5 kb) |

3 |

5 |

3 |

11 |

| Ycos54 (19 kb) |

6 |

4 |

6 |

16 |

| Ycos78 (14 kb) |

7 |

6 |

3 |

16 |

| Ycos68 (4 kb) |

7 |

3 |

5 |

15 |

| Ycos65 (1.4 kb) | 4 | 3 | 8 | 15 |

aCosmids used (Fig. 1) with the approximate length of the α1AT 5′ flanking region in parentheses.

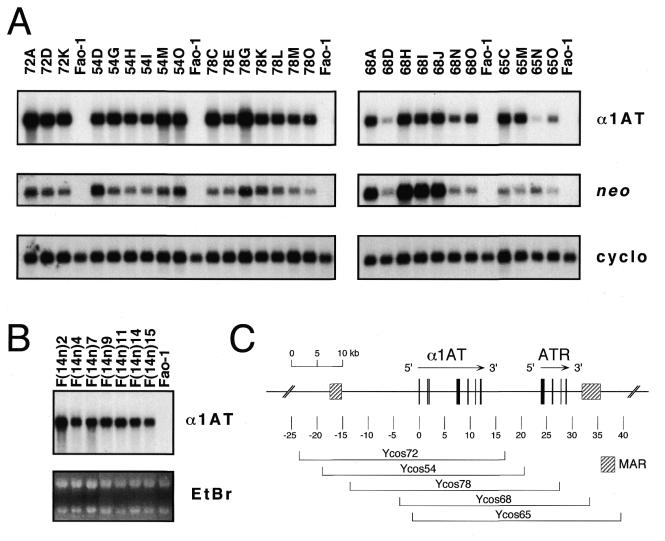

Expression of human α1AT mRNA in rat hepatoma transfectants

To determine whether the cosmid transfectants expressed human α1AT, cytoplasmic RNAs were prepared, and steady-state levels of α1AT mRNA were assayed by northern hybridization using a human exon II probe that did not cross-hybridize with rat α1AT sequences. Neo mRNA levels were also assessed, as were levels of rat cyclophilin mRNA, which served as a loading control. Figure 3A shows an example of this analysis for the five different families of single-copy, intact cosmid transfectants.

Figure 3.

Expression of human α1AT mRNA in single-copy cosmid transfectants. (A) Cytoplasmic RNAs (5 µg/lane) from the indicated single copy Ycos72, Ycos54, Ycos78, Ycos68 and Ycos65 transfectant clones or untransfected rat hepatoma cells (Fao-1) were prepared, and steady-state levels of human α1AT mRNA were analyzed by northern hybridization. The α1AT probe was a human-specific exon II DNA fragment that did not cross-hybridize with rat α1AT sequences. Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (neo) mRNA levels from the SuperCos1 vector were also assayed. As a loading control, the filters were stripped and rehybridized with a rat cyclophilin (cyclo) probe. (B) Seven rat hepatoma microcell hybrids containing an apparently intact human chromosome 14 (31) were analyzed for human α1AT mRNA levels as above. As loading controls, the intensities of the ethidium bromide-stained ribosomal RNA bands (EtBr) are shown. These images are composites made from two different gels. (C) The map shows the extent of each cosmid insert, together with the position of the serpin genes and the MARs, as described in the legend to Figure 1.

All three Ycos72 transfectants and six Ycos54 transfectants that contained single, intact transgenes (Fig. 3; 72A, 72D and 72K, and 54D, 54G, 54H, 54I, 54M and 54O), expressed high levels of human α1AT mRNA. Furthermore, α1AT mRNA levels in these clones varied only ∼2–3-fold among the clones. Thus, the α1AT mRNA expression phenotypes of the Ycos72 and Ycos54 transfectants were similar to those of rat hepatoma microcell hybrids containing human chromosome 14, in which human α1AT resides in its normal chromosomal context (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that Ycos72 and Ycos54, with ∼23 and 19 kb of sequences upstream of α1AT and ∼4.9 and 8.5 kb downstream, respectively (Fig. 3C), contain all of the cis-regulatory sequences necessary for recipient cell-typical, position-independent α1AT expression in rat hepatoma cells. α1AT mRNA was also expressed at high levels in the seven Ycos78 transfectants, although perhaps more variably. Thus, the presence (in Ycos54) or absence (in Ycos78) of the α1AT 5′ MAR had little effect on α1AT transgene expression in this assay.

In marked contrast to the α1AT expression phenotypes of the Ycos72, Ycos54 and Ycos78 transfectants, α1AT mRNA expression in transfectants that contained similarly sized trangenes with relatively small 5′ flanking regions was highly variable (Fig. 3A). For example, Ycos68 and Ycos65 transgenes, which contained only ∼4 and 1.4 kb of 5′ flanking DNA, respectively (Fig. 3C), were expressed at very different levels in different single copy, intact transfectant clones. Furthermore, some of the Ycos68 and Ycos65 transfectants expressed very low levels of human α1AT mRNA (Fig. 3A; 68D and 65N). Thus, expression of these transgenes was sensitive to chromosomal position effects at the site of transgene insertion, effects that were not observed in transgenes with larger 5′ flanking segments.

Levels of neo mRNA in the various transfectant clones were also assessed and compared to levels of α1AT mRNA (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Neo mRNA expression was highly variable among the transfectant clones, and there was no apparent correlation between α1AT and neo mRNA levels. Thus, although neo expression appeared to be subject to chromosomal position effects at the site of transgene insertion, the linked α1AT gene was not. This was observed whether the neo expression cassette was positioned upstream or downstream of the α1AT gene in the linearized cosmid vector (Fig. 3A and data not shown).

Finally, all single copy transfectants analyzed that contained an intact α1AT structural gene expressed α1AT mRNA that could be detected by northern hybridization. In this sense, expression of these transgenes, including those with small 5′ flanking segments, appeared position-independent. Clones that contained multiple α1AT transgenes generally, but not always, expressed higher levels of α1AT mRNA than single-copy clones (data not shown).

Stable long-term α1AT expression in the absence of selection

Transgene expression often decays with time in culture when selective pressure is removed (for review see 27,28). Furthermore, expression of the selected neo marker was not correlated with expression of the linked α1AT gene in our cosmid transfectants (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we determined the stability of neo and human α1AT mRNA expression in the absence of selection. We were particularly interested in determining whether the presence or absence of the α1AT 5′ MAR affected gene silencing in this assay.

Three single-copy, intact Ycos72 transfectants (Fig. 3; 72A, 72D and 72K) and Ycos68 transfectants (Fig. 3; 68H, 68J and 68N), containing ∼23.5 and 4 kb of α1AT 5′ flanking DNA, respectively (Fig. 1), were cultured in the absence of G418 selection for more than 30 passages by splitting the cells ∼1:10 twice a week. Cytoplasmic RNAs were isolated at intervals and used in northern hybridizations to assess neo and human α1AT mRNA levels. As shown in Figure 4, neo mRNA levels decreased with time in non-selective medium in each of the six transfectants. In contrast, expression of the linked α1AT gene was constant over the same time course, and no decay in α1AT expression was observed for either transgene at the six different integration sites tested.

Figure 4.

Expression of neo and human α1AT mRNAs in the absence of selection. Six single-copy, intact cosmid transfectant clones (F/cos72A, F/cos72D, F/cos72K, F/cos68H, F/cos68J and F/cos68N) were grown in the absence of G418 selection for more than 30 passages, and cytoplasmic RNAs (5 µg/lane) were prepared after 3, 6, 12 and 16 weeks (lanes marked 3, 6, 12 and 16) and analyzed for neo, human α1AT and rat cyclophilin mRNA expression as described in the legend to Figure 3. Lanes marked ‘0’ are two separate RNA samples from the cell lines prior to removal of G418. Lanes marked F contained RNA from parental Fao-1 rat hepatoma cells.

Chromatin organization of single-copy cosmid transfectants

We previously mapped 22 DHSs in the ∼85 kb region extending from ∼30 kb upstream of α1AT to ∼25 kb downstream of ATR in expressing cells, but only six of those sites were found in non-expressing cells. Furthermore, transfer of human chromosome 14 from non-expressing fibroblasts to expressing rat hepatoma cells activated α1AT and CBG transcription, and this was accompanied by the de novo formation of expression-associated DHSs (20). To determine whether recipient cell-typical patterns of DHSs could be formed on shorter genomic templates, we mapped DHSs in four single-copy, intact α1AT cosmid transfectants.

Nuclei from transfectant clones F/cos72A, 78L, 65M and 59F (Figs 1 and 3) were isolated and treated with increasing concentrations of DNase I. DNA was purified and digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, and the presence of specific DHSs was assessed by Southern hybridization, as described previously (20,21). An example of this analysis is shown in Figure 5A, where the α1AT promoter region was analyzed. All three transfectants used in this experiment exhibited two strong DHSs at, approximately, positions +1.85 and –0.15 kb. The DHS at about –0.15 kb is a constitutive site that was found in all cells previously examined (20,21,37), whereas the site at approximately +1.85 kb, at the liver-specific α1AT promoter, was expression associated. On this particular blot, the DHS at about position –2.2 kb was masked by the strength of the two other sites present in this restriction fragment, but it was easily observed using other restriction enzyme/probe combinations (e.g. Fig. 5B and data not shown).

Another example of DHS mapping in α1AT upstream region is shown in Figure 5B. F/cos72A cells showed two DHSs at, approximately, positions –18.9 and –5.5 kb (left and middle panels), whereas in F/cos78L cells, three DHSs, at about positions –4.1, –3.4 and –2.2 kb (right panel), were observed in addition to the constitutive site at about –0.15 kb (Fig. 5A and B). Moving downstream of α1AT, between ATR and CBG, F/cos65M cells exhibited two DHSs at approximately +37 and +37.5 kb, typical of expressing cells (Fig. 5C, left panel). Similarly, F/cos59F cells contained sites at approximately +50.1 and +51.9 kb (Fig. 5C, right panel).

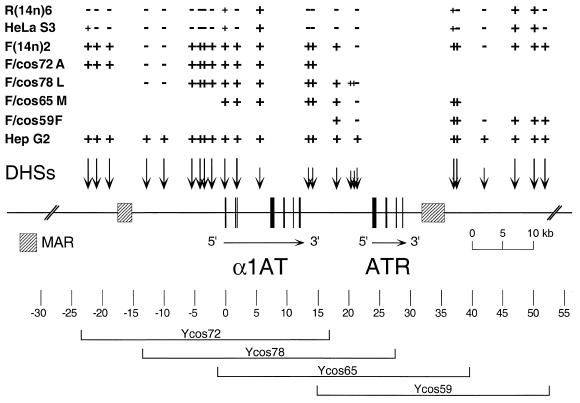

Similar DHS mapping experiments were performed throughout the region (from approximately –30 to +55 kb relative to the macrophage-specific promoter of α1AT) on the four single-copy transfectants. Results of these experiments are summarized in Figure 6, where the DHS maps of the cosmid alleles are compared to those of expressing (HepG2), non-expressing (HeLa S3), activated [F(14n)2] and extinguished [R(14n)6] serpin alleles. Most DHSs were mapped using two different probe/restriction enzyme combinations, and, as shown in the figure, the DHS maps of the cosmid transfectants perfectly recapitulated the structures of activated α1AT alleles in rat hepatoma microcell hybrids (with the exception of two novel, weak sites at about +20 kb in F/cos78L). Significantly, F/cos59F cells displayed a hepatoma-typical pattern of DHSs, despite the fact that this serpin transgene was transcriptionally inactive, as it contained only the ATR pseudogene (2–4).

Figure 6.

Long-range DHS map of α1AT-ATR alleles. The map is drawn to scale, with position zero defined as an EcoRI site in exon IA of α1AT. Exons are indicated as black boxes, with arrows showing the transcriptional orientations of the genes. MARs are shown as hatched boxes. DHSs are depicted above the map as vertical arrows. Long arrows indicate strong DHSs, and short arrows weak sites in the HepG2 cells. The presence or absence of specific DHSs in various microcell hybrids containing human chromosome 14 and single-copy cosmid transfectants [HepG2, expressing human hepatoma allele; HeLa S3, non-expressing human allele; F(14n)2, activated allele in rat hepatoma cells; R(14n)6, extinguished allele in rat fibroblasts; F/cos72A, F/cos78L, F/cos65M and F/cos59F, cosmid transfectants; see Figs 1 and 3] is indicated above the map by + or – signs. Small + indicates a DHS weaker than that of the expressed HepG2 allele. The positions of the genomic inserts of the four transfectants analyzed are indicated below the map.

Together with a previous study showing that MAR sequences are matrix associated in cosmid transfectants (19), the data reported here demonstrate that cosmids containing various portions of the human 14q32.1serpin gene cluster are organized into an expressing cell-typical chromatin structure in transfected cells. Thus, the transgenes contain cis-regulatory sequences that are sufficient for the formation of stable, liver-specific chromatin structures, and the differentiated rat hepatoma recipient cells provide the trans-acting factors that are required for establishing and maintaining these cell-specific chromatin structures at ectopic chromosomal sites.

DISCUSSION

The human serpin gene cluster at 14q32.1 is a useful model system for studying relationships between cell-specific gene expression and chromatin structure. The five protein-coding genes of the cluster, α1AT, AACT, CBG, KAL and PCI, are all expressed in the liver and cultured hepatoma cells, but they are transcriptionally inactive in most cell types. Other cells express a subset of the serpin genes; for example, macrophages and intestinal epithelial cells express α1AT but not CBG (6,7). In macrophages, a distinct promoter ∼2 kb upstream of the liver/intestinal promoter is employed (37,38).

Transgenes have been used extensively in both cultured cells and transgenic animals to study the cell-specific regulation of gene activity. In stable transfectants, transgene expression is generally unpredictable, expression levels vary from clone to clone, and expression does not generally correlate with transgene copy number. It is believed that these variations are largely due to position effects at the sites of transgene insertion (for reviews see 23–28). Furthermore, stably integrated transgenes are generally expressed at levels that are lower than those of the corresponding chromosomal alleles. This may be due to the generally suppressive effects of chromatin structure on gene expression in mammalian cells (8,24,39). Stable transfectants also tend to delete and/or rearrange transgene sequences, and many of them contain concatemeric transgene arrays that are prone to transcriptional silencing (27,40,41). All of these factors conspire to make phenotype/genotype correlations in stable transfectants far less straightforward than they might seem.

In this study, we tested whether cosmids containing the human α1AT gene and various amounts of flanking DNA were properly regulated in stable rat hepatoma transfectants. The experiments were designed to circumvent some of the problems that are generally encountered in transfection studies, as follows. First, the transgenes that we employed contained a selection cassette, neo, at one end of the linearized vector and the test gene, human α1AT, as a linked genomic DNA segment of at least ∼30 kb. Thus, the transfectants contained not only the α1AT gene itself (∼12 kb), but considerable segments of flanking DNA. Second, the transgenes were introduced into Fao-1 rat hepatoma recipient cells by electroporation, which tends to yield single or low copy number transfectants. This avoids issues associated with concatemeric transgene arrays. Third, individual transfectant clones were isolated, and their transgene genotypes were carefully determined by Southern hybridization using a variety of specific probes from the α1AT-ATR region. This allowed us to identify those clones that contained single, intact transgene insertions. Fourth, we analyzed the expression phenotypes of several independent, single copy clones for each transgene used, and we compared α1AT mRNA levels both within and among the different transfectant classes. In these studies we used human α1AT mRNA levels in rat hepatoma microcell hybrids, which we showed to be relatively constant, as the wild-type standard for comparison.

Five different cosmids containing α1AT coding sequences plus various amounts of 5′ and 3′ flanking DNA yielded multiclonal pools of transfectants that expressed comparable levels of α1AT mRNA, regardless of the flanking sequences in the transgenes (from ∼24 to ∼1.4 kb upstream and ∼4.8 to ∼27 kb downstream of α1AT, data not shown). However, only ∼25–50% of individual transfectant clones contained single copy, intact transgenes. Once these clones were identified and characterized, variations in steady-state levels of α1AT mRNA were apparent. In particular, single copy transfectants containing short 5′ flanking regions (∼1.4 and ∼4 kb) were expressed much more variably and usually at lower levels than similarly sized transgenes with 14–24 kb of 5′ flanking DNA. These data suggest that chromosomal position effects commonly occur in transgenes with relatively short 5′ flanking sequences, when the test gene is near the end of the transgene insertion, but transgenes with longer 5′ flanking segments are largely immune to these effects. Accordingly, our α1AT transgenes with 23.5, 19 and 14 kb of 5′ flanking DNA were all expressed at high levels in single copy transfectants, levels that were comparable to those of hepatoma microcell hybrids that retained an intact human chromosome 14. Whether there are specific cis-elements that mediate these effects, or whether non-specific buffering is involved, is not presently known. Clearly, however, the presence or absence of the α1AT 5′ MAR (19) had little effect on transgene expression in these assays, and it did not affect the yields of neo-resistant clones in cosmid transfection experiments.

A caveat in the interpretation of virtually all stable transfection experiments concerns the effects of the selected marker. Irrespective of whether the marker under selection is part of the test vector, as in this study, or is cotransfected as a separate plasmid, both genes almost invariably become integrated at a common chromosomal site (for example see 40,42). Those sites must allow for expression of the selected marker, and this may bias the kinds of integration sites that can be sampled by this method. In the transfectants described in this report, there was no correlation between levels of neo mRNA and α1AT mRNA in individual transfectant clones, although both genes were integrated together. Furthermore, the position of the neo expression cassette, either upstream or downstream of α1AT, did not affect α1AT mRNA levels (compare Ycos65 and Ycos68 transfectants in Fig. 3). Similarly, linearizing Ycos54, Ycos72 and Ycos78 with PvuI instead of MluI gave rise to transgene insertions with the neo cassette downstream rather than upstream of α1AT, but this had no effect on α1AT mRNA levels (data not shown). Finally, α1AT mRNA expression in these transfectants was stable in the absence of selection, but neo mRNA expression was not.

There are two aspects of our transfectants’ phenotypes that are noteworthy. First, in three different families of transfectants with large (14–24 kb) 5′ flanking regions, α1AT mRNA was expressed at recipient-typical levels that were mostly invariant among single copy clones and stable in the absence of selection. These phenotypes are very different from those of most stable transfectants (for example see 21,42). Second, neo and α1AT mRNA levels in the transfectants were not correlated in either the presence or absence of selection. What could account for these unusual properties? One important factor may be the strength of the α1AT promoter/enhancer. The α1AT gene is one of the most highly expressed genes in the liver, and the α1AT promoter is strongly activated by two liver-enriched transactivators, HNF-1α and HNF-4 (43–45). HNF-1α and HNF-4 bind to specific sites in the hepatocyte promoter at about –70 and –110 bp, respectively. Strong activation through this promoter might render the α1AT transcription unit relatively insensitive to chromosomal position effects, so that high levels of transgene expression might be observed in most single copy clones. This would also explain why neo and α1AT mRNA levels were not correlated, as neo transcription was initiated from a viral promoter that is much less active than the α1AT promoter in this cell type. Strong promoter/enhancer combinations are known to make genes relatively insensitive to position effects in yeast and other systems (for example see 42,46,47). On the other hand, the α1AT promoter is not in itself sufficient for high level transgene expression, because cosmid transgenes with only ∼1.4 or 4 kb of 5′ flanking DNA were variably expressed. Thus, the 5′ flanking DNA played a role, either specific or non-specific, in insulating transgene expression in the transfectants. In transgenic mice, α1AT constructs with only ∼2–7 kb of 5′ flanking DNA were expressed at high levels in the liver, although these transgenes were usually present in multicopy arrays (33,48,49).

Relative promoter strength might also explain why α1AT mRNA expression was stable in the absence of selection, but neo expression was not. Transgenes integrated at different chromosomal sites are often subject to gradual silencing in the absence of selection (27,28,42,47). This process seems to involve transgene relocalization within the nucleus to a repressive chromatin environment (for review see 50). Functional enhancers can suppress transgene silencing (51), and there is evidence that some chromosomal boundary elements, like the chicken β-globin HS4, play critical roles in protecting transgenes from silencing and/or position effects (42,52–54). We were interested in determining whether the α1AT 5′ MAR would protect transgenes from silencing upon cultivation in non-selective medium. Surprisingly, we found that expression of all of the α1AT transgenes we tested was stable in the absence of selection. The relative strength of the α1AT promoter/enhancer likely plays a dominant role in maintaining this stable expression phenotype.

The chromatin structure of the α1AT-ATR-CBG region, as assessed by distributions of DHSs, is correlated with gene activity in expressing versus non-expressing cells (20,21,37). HepG2 cells display 29 DHSs in this ∼130 kb interval, while non-expressing HeLa S3 cells have only seven of those sites. Microcell transfer of human chromosome 14 from non-expressing fibroblasts to rat hepatoma cells resulted in activation of α1AT and CBG transcription and the formation of expression-associated DHSs. In hepatic cells, both gene activation and chromatin remodeling required HNF-1α and HNF-4 (20,21). To assess whether cell-specific chromatin structures could form on shorter templates, we mapped DHSs in α1AT cosmid transgenes. These experiments revealed that α1AT cosmids integrated at ectopic chromosomal sites in rat hepatoma cells were appropriately structured; the distributions of DHSs in the transgenes were identical to those of the human α1AT locus in rat hepatoma microcell hybrids. Significantly, Ycos59F, a cosmid transfectant that expresses neo but no serpin gene (it contains the non-expressed ATR pseudogene but no α1AT genomic sequences), displayed all of the expression-associated DHSs typical of the region. Thus, cis-acting elements and not transcription per se seem to be sufficient for the formation of cell-specific DHSs on α1AT templates in an expressing cell environment. However, this interpretation is subject to the caveat that transcription of the linked neo marker might play a role in establishing an open chromatin configuration of the entire transgene. Further work will be required to address this issue. Nonetheless, both DHSs and matrix associations of MARs within α1AT transgenes (19) are recapitulated in cosmid transfectants.

In summary, the data presented here indicate that transgenes in cosmid transfectants can be expressed and organized in a manner similar to the corresponding chromosomal alleles. An important future goal will be to assess the roles of promoters, enhancers and other regulatory elements in contributing to these stable expression phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mark Groudine, Claire Francastel and Stephanie Namciu for their comments on the manuscript. These studies were supported by grant GM26449 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. P.R. was supported by fellowships from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss League against Cancer, and the Schweizerische Stiftung für Medizinisch-Biologische Stipendien.

REFERENCES

- 1.Potempa J., Korzus,E. and Travis,J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 15957–15960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao J.J., Reed-Fourquet,L., Sifers,R.N., Kidd,V.J. and Woo,S.L. (1988) Genomics, 2, 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofker M.H., Nelen,M., Klasen,E.C., Nukiwa,T., Curiel,D., Crystal,R.G. and Frants,R.R. (1988) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 155, 634–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelsey G.D., Parkar,M. and Povey,S. (1988) Ann. Hum. Genet., 52, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rollini P. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1997) Genomics, 46, 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perlmutter D.H., Cole,F.S., Kilbridge,P., Rossing,T.H. and Colten,H.R. (1985) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 795–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlmutter D.H., Daniels,J.D., Auerbach,H.S., De Schryver-Kecskemeti,K., Winter,H.S. and Alpers,D.H. (1989) J. Biol. Chem., 264, 9485–9490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenfeld G. (1992) Nature, 355, 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownell J.E. and Allis,C.D. (1996) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 6, 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingston R.E., Bunker,C.A. and Imbalzano,A.N. (1996) Genes Dev., 10, 905–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsukiyama T. and Wu,C. (1997) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 7, 182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolffe A.P., Wong,J. and Pruss,D. (1997) Genes Cells, 2, 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadonaga J.T. (1998) Cell, 92, 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Struhl K. (1998) Genes Dev., 12, 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elgin S.C. (1988) J. Biol. Chem., 263, 19259–19262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross D.S. and Garrard,W.T. (1988) Annu. Rev. Biochem., 57, 159–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli U.K., Kas,E., Poljak,L. and Adachi,Y. (1992) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 2, 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bode J., Stengert-Iber,M., Kay,V., Schlake,T. and Dietz-Pfeilstetter,A. (1996) Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr., 6, 115–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollini P., Namciu,S.J., Marsden,M.D. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 3779–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rollini P. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1999) Genomics, 56, 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rollini P. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1999) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 10308–10313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieken E.S., Epner,E.M., Fiering,S., Fournier,R.E.K. and Groudine,M. (1996) Nature Genet., 12, 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kucherlapati R. and Skoultchi,A.I. (1984) CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem., 16, 349–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmiter R.D. and Brinster,R.L. (1986) Annu. Rev. Genet., 20, 465–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark A.J., Bissinger,P., Bullock,D.W., Damak,S., Wallace,R., Whitelaw,C.B. and Yull,F. (1994) Reprod. Fertil. Dev., 6, 589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop J.O. (1996) Reprod. Nutr. Dev., 36, 607–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin D.I.K. and Whitelaw,E. (1996) Bioessays, 18, 919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivella S. and Sadelain,M. (1998) Semin. Hematol., 35, 112–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitot H.C., Peraino,C., Morse,P.A. and Potter,V.R. (1964) Natl Cancer Inst. Monogr., 13, 229–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lugo T.G., Handelin,B., Killary,A.M., Housman,D.E. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1987) Mol. Cell. Biol., 7, 2814–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapero M.H., Langston,A.A. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1994) Somat. Cell Mol. Genet., 20, 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albertsen H.M., Abderrahim,H., Cann,H.M., Dausset,J., Le Paslier,D. and Cohen,D. (1990) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 4256–4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelsey G.D., Povey,S., Bygrave,A.E. and Lovell-Badge,R.H. (1987) Genes Dev., 1, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danielson P.E., Forss-Petter,S., Brow,M.A., Calavetta,L., Douglass,J., Milner,R.J. and Sutcliffe,J.G. (1988) DNA, 7, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rollini P. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1997) Mamm. Genome, 8, 913–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sladek F.M., Zhong,W.M., Lai,E. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1990) Genes Dev., 4, 2353–2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollini P. and Fournier,R.E.K. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1767–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perlino E., Cortese,R. and Ciliberto,G. (1987) EMBO J., 6, 2767–2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eissenberg J.C. and Elgin,S.C. (1991) Trends Genet., 7, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalos M. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henikoff S. (1998) Bioessays, 20, 532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pikaart M.J., Recillas-Targa,F. and Felsenfeld,G. (1998) Genes Dev., 12, 2852–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Simone V., Ciliberto,G., Hardon,E., Paonessa,G., Palla,F., Lundberg,L. and Cortese,R. (1987) EMBO J., 6, 2759–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y., Shen,R.F., Tsai,S.Y. and Woo,S.L. (1988) Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 4362–4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bulla G.A., DeSimone,V., Cortese,R. and Fournier,R.E.K. (1992) Genes Dev., 6, 316–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renauld H., Aparicio,O.M., Zierath,P.D., Billington,B.L., Chhablani,S.K. and Gottschling,D.E. (1993) Genes Dev., 7, 1133–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walters M.C., Magis,W., Fiering,S., Eidemiller,J., Scalzo,D., Groudine,M. and Martin,D.I.K. (1996) Genes Dev., 10, 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruther U., Tripodi,M., Cortese,R. and Wagner,E.F. (1987) Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 7519–7529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sifers R.N., Carlson,J.A., Clift,S.M., DeMayo,F.J., Bullock,D.W. and Woo,S.L. (1987) Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 1459–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cockell M. and Gasser,S.M. (1999) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 9, 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Francastel C., Walters,M.C., Groudine,M. and Martin,D.I.K. (1999) Cell, 99, 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung J.H., Whiteley,M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1993) Cell, 74, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inoue T., Yamaza,H., Sakai,Y., Mizuno,S., Ohno,M., Hamasaki,N. and Fukumaki,Y. (1999) J. Hum. Genet., 44, 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walters M.C., Fiering,S., Bouhassira,E.E., Scalzo,D., Goeke,S., Magis,W., Garrick,D., Whitelaw,E. and Martin,D.I.K. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 3714–3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]