This randomized clinical trial seeks to determine the efficacy and safety of cytisinicline vs placebo to produce abstinence from e-cigarette use in adults seeking to quit vaping nicotine.

Key Points

Question

Is cytisinicline an effective and safe pharmacotherapy to help adults stop vaping nicotine e-cigarettes?

Findings

In a multisite randomized clinical trial that included 160 adults who vaped nicotine e-cigarettes but did not smoke cigarettes, a 12-week course of cytisinicline with behavioral support was more effective than placebo with behavioral support and was very well tolerated, producing significantly more continuous abstinence from e-cigarette use than placebo during the last 4 weeks of drug treatment (31.8% vs 15.1%).

Meaning

Cytisinicline is a potentially effective and safe pharmacotherapy for vaping cessation in adults who use nicotine e-cigarettes and seek to quit vaping.

Abstract

Importance

The prevalence of e-cigarette use among US adults, especially young adults, is rising. Many would like to quit vaping nicotine but are unable to do so. Cytisinicline, a plant-based alkaloid, targets nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reduces nicotine dependence, and helps adults to stop smoking cigarettes. Cytisinicline may also help e-cigarette users to quit vaping.

Objective

To determine the efficacy and safety of cytisinicline vs placebo to produce abstinence from e-cigarette use in adults seeking to quit vaping nicotine.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial compared 12 weeks of treatment with cytisinicline vs placebo, with follow-up to 16 weeks. It was conducted from July 2022 to February 2023 across 5 US clinical trial sites. A total of 160 adults who vaped nicotine daily, sought to quit, and did not currently smoke cigarettes were enrolled, and 131 (81.9%) completed the trial.

Intervention

Participants were randomized (2:1) to cytisinicline, 3 mg, taken 3 times daily (n = 107) or placebo (n = 53) for 12 weeks. All participants received weekly behavioral support.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Biochemically verified continuous e-cigarette abstinence during the last 4 weeks of treatment (weeks 9-12; primary outcome) and through 4 weeks posttreatment (weeks 9-16; secondary outcome). Missing outcomes were counted as nonabstinence.

Results

Of 160 randomized participants (mean [SD] age, 33.6 [11.1] years; 83 [51.9%] female), 115 (71.9%) formerly smoked (≥100 lifetime cigarettes). Continuous e-cigarette abstinence in cytisinicline and placebo groups occurred in 34 of 107 participants (31.8%) vs 8 of 53 participants (15.1%) (odds ratio, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.06-7.10; P = .04) at end of treatment (weeks 9-12) and in 25 of 107 participants (23.4%) vs 7 of 53 participants (13.2%) during weeks 9 to 16 (odds ratio, 2.00; 95% CI, 0.82-5.32; P = .15). There was no evidence, based on nonsignificant interactions, that cytisinicline efficacy differed in subgroups defined by demographic characteristics, vaping pattern, e-cigarette dependence, or smoking history. Cytisinicline was well tolerated, with 4 participants (3.8%) discontinuing cytisinicline due to an adverse event.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, cytisinicline for 12 weeks, with behavioral support, demonstrated efficacy for cessation of e-cigarette use at end of treatment and was well tolerated by adults, offering a potential pharmacotherapy option for treating nicotine e-cigarette use in adults who seek to quit vaping. These results need confirmation in a larger trial with longer follow-up.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05431387

Introduction

E-cigarettes are battery-operated devices that heat a liquid containing nicotine, propylene glycol, and/or glycerin and flavorings, producing an aerosol that users inhale (“vape”).1,2 The prevalence of e-cigarette use by US adults, especially young adults, is rising, reaching 4.5% among all adults and 11.0% among adults aged 18 to 24 years in 2021.3,4 In surveys, more than half of adults who vape nicotine plan to quit using e-cigarettes, and one-quarter report having attempted to do so in the past year.5,6,7 Some succeed on their own, but many need help to quit vaping.7

Evidence from clinical trials to guide vaping cessation treatment, especially pharmacotherapy, is limited.8,9,10,11,12,13 Varenicline demonstrated efficacy for e-cigarette cessation among adults in a randomized trial,8 and a pilot trial suggested efficacy for nicotine replacement.9 No medication has approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for vaping cessation. The UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency has approved a nicotine-containing mouth spray, already licensed for smoking cessation, to be marketed for vaping cessation.14 With nicotine-containing e-cigarette use rising, safe and effective treatments to help individuals who wish to stop vaping is an urgent need.

Cytisinicline, a partial agonist at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that mediate nicotine dependence, has shown efficacy for cigarette smoking cessation.15,16,17,18,19,20 Because cytisinicline use is associated with reduced nicotine dependence,15 we hypothesized that the medication would also help adults to quit vaping nicotine. This phase 2 multisite double-blind randomized clinical trial tested the efficacy and safety of cytisinicline at a dose of 3 mg 3 times daily for 12 weeks compared with placebo to help adults who vape nicotine to quit. Both groups received behavioral support, and the trial excluded current cigarette smokers (ie, dual users).

Methods

Setting and Participants

The trial was conducted at 5 US sites. Adults 18 years and older were eligible if they reported current daily use of a nicotine-containing e-cigarette, had a positive (≥30 ng/mL) saliva cotinine test result,21 intended to quit vaping, and were willing to set a quit date 7 to 14 days after starting the study drug and participate in vaping-cessation behavioral support. To isolate the effects of cytisinicline for quitting nicotine vaping, we excluded dual users, defined as individuals who reported having smoked a cigarette or used another combustible or noncombustible tobacco product in the 4 weeks prior to study randomization or who had an expired air carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or higher. Other exclusion criteria included past-month use of smoking cessation medication (eg, bupropion, varenicline, nortriptyline, nicotine-replacement product); a plan to use cigarettes or any nicotine-containing nonvaping product during study drug treatment; a positive urinary screen for illicit drugs (not including cannabis); uncontrolled hypertension (blood pressure ≥160/100 mm Hg); kidney or hepatic impairment; past 3-month history of acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, cerebrovascular incident, or hospitalization for congestive heart failure; past-month unstable pulmonary disease; diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, current psychosis, or suicidal ideation or suicide risk in the past 3 months22; moderate to severe depression symptoms23; and being pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to use acceptable birth control methods during the study. Individuals who used cannabis could enroll but were asked to refrain from smoking cannabis during the study.

The ORCA-V1 (Ongoing Research of Cytisinicline for Addiction) trial was approved by a centralized institutional review board (Advarra). Participants provided written informed consent and were randomized from July to November 2022. Data collection ended in February 2023. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines. Full protocol details are presented in Supplement 1.

Recruitment and Assignment to Condition

At a screening visit, individuals provided written informed consent; completed a medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and laboratory tests; agreed to a quit date 7 to 14 days after study drug initiation; and provided a record of e-cigarette use on 7 consecutive days. A saliva sample for cotinine measurement and a breath sample for carbon monoxide measurement were collected. At visit 2, participants who met inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to study group, received brief vaping-cessation counseling, and set their quit date. Participants started study medication the next day. A predetermined central computer-generated randomization sequence assigned participants in a 2:1 ratio to receive cytisinicline or placebo for 12 weeks. The 2:1 randomization allowed more participants to report cytisinicline safety data. Randomization was stratified by lifetime history of cigarette smoking, defined as having smoked more than 100 cigarettes.3 Participants and study staff at all sites were blinded to study group assignment throughout the data collection period.

Interventions

The study medication was identical-appearing tablets containing 3 mg of cytisinicline or placebo taken orally 3 times daily for 12 weeks. Participants were followed up for 4 additional weeks after treatment ended. At each of 13 visits from randomization through week 12, trained counselors offered all participants 10 minutes of brief vaping-cessation support (total of ≤130 minutes) using methods adapted from smoking cessation motivational and cognitive-behavioral treatment.

Assessments

Baseline data collection included sociodemographic characteristics, smoking history, e-cigarette history, e-cigarette dependence,24 device type used, e-liquid flavor used, reason to quit vaping, motivation for and confidence to quit, and mood symptoms.23 A telephone call at day 1 verified participants’ initial medication adherence and recorded any adverse events. At weekly in-person visits (weeks 1-12) and at week 16, 4 weeks after treatment ended, participants reported nicotine e-cigarette use since the last visit and provided a breath sample to measure carbon monoxide and a saliva sample to measure cotinine, a nicotine metabolite. A carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or higher was interpreted as evidence of having smoked a combustible product, and these participants were asked about past week smoking of tobacco or cannabis.

Safety was assessed at weekly visits by measurement of vital signs and participants’ report of adverse events using open-ended questions. Blood and chemistry laboratory tests were completed at baseline and weeks 1, 6, and 12. Electrocardiograms were completed at baseline and weeks 6 and 12. Clinically significant adverse events were followed until resolution or week 16.

Outcome Measures

The primary end point was cotinine-verified continuous e-cigarette abstinence during the last 4 weeks of treatment, defined as self-reported e-cigarette abstinence since the last weekly visit during weeks 9 to 12 and confirmed by a saliva cotinine level of less than 10 ng/mL, using tandem mass spectrometry (1 ng/mL lower limit of quantitation). Participants not meeting these criteria or with missing data were considered nonabstinent. Exploratory analyses assessed effect modification in subsets defined by baseline attributes including age, sex, race, history of prior cigarette smoking, age of initial e-cigarette use, e-liquid flavor used, and e-cigarette dependence level.23

Four secondary outcome measures of vaping behavior were (1) a 4-week period of cotinine-verified continuous vaping abstinence earlier during treatment (weeks 3-6 and 6-9); (2) cotinine-verified continuous vaping abstinence from end of treatment through 4 weeks posttreatment (weeks 9-16); (3) cotinine-verified point-prevalence e-cigarette abstinence at each weekly visit from weeks 2 to 12 and at week 16; and (4) quantitative cotinine level, a measure of nicotine intake, assessed by weekly saliva cotinine levels at weeks 2 to 12. An additional outcome was the proportion of participants with evidence suggesting tobacco smoking during the last 4 weeks of treatment, defined as self-report of cigarette smoking or breath carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or higher at a weekly visit. This measure excluded participants with a carbon monoxide level of 10 ppm or higher who reported past-week cannabis use and denied past-week cigarette smoking. Safety outcomes included the incidence of treatment-emergent serious and nonserious adverse events and clinically significant changes in vital signs, laboratory tests, or electrocardiogram results during the study.

Statistical Analysis

The overall statistical goal was to obtain effect outcomes to inform the design of future studies. Analyses for binary efficacy outcomes were based on exact analyses 2 × 2 tables. Analysis of the primary outcome was stratified by lifetime history of cigarette smoking. A target sample of 150 participants (100 in the cytisinicline group and 50 in the placebo group) was estimated to provide 95% power to detect a difference of 18% vs 6% in continuous vaping abstinence at weeks 9 to 12 with a type I error of 2-sided α = .05. Sensitivity analyses included assessments of effect modification of the primary outcome in subsets defined by baseline attributes using logistic and cumulative logit models; these effect modification assessments were not stratified by lifetime history of cigarette smoking due to absence of effect modification of this randomization stratifier. Safety analyses included all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of the study drug.

All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and all tests were 2-sided. Additional information is available in the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2).

Results

Participants

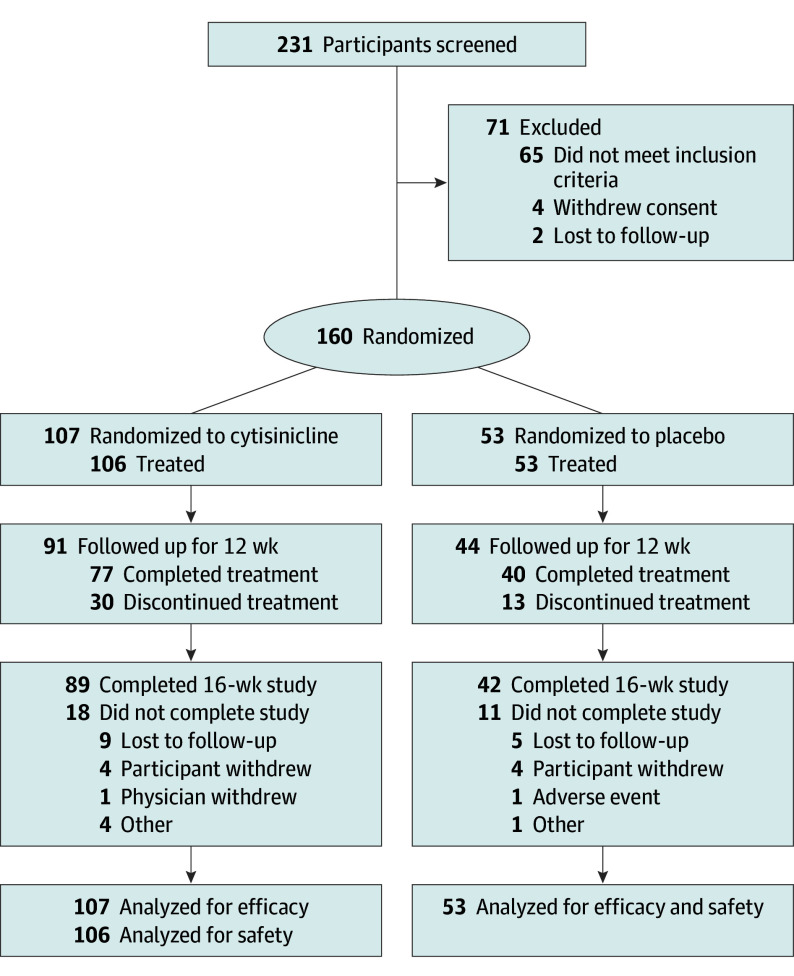

Of 231 individuals screened, 160 were eligible and randomized to cytisinicline (n = 107) or placebo (n = 53) (Figure 1). Efficacy analyses included all 160 randomized participants. Safety analyses excluded 1 participant assigned to cytisinicline who discontinued the study before receiving the drug.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Follow-up assessments at the end of the study (week 16) were completed by 131 participants (81.9%), 89 (83.2%) in the cytisinicline group and 42 (79.2%) in the placebo group. Study completers did not differ from noncompleters in age, sex, race and ethnicity, or baseline e-cigarette use. Study drug compliance was high: 77 (72.7%) and 35 (66.0%) participants randomized to the cytisinicline and placebo groups, respectively, took 90% or more of study drug doses. Of the 13 planned behavioral support sessions during the study, the mean (SD) number of sessions completed by participants were 11.9 (2.44) in the cytisinicline group and 11.4 (3.29) in the placebo group.

Baseline characteristics were similar between study groups (Table 1). Participants had a mean (SD) age of 33.6 (11.1) years, 83 (51.9%) were female, 6 (3.8%) were Asian, 14 (8.8%) were Black or African American, 135 (84.4%) were White, 5 (3.1%) were another race, and 9 (5.6%) were of Hispanic ethnicity. Overall, 126 participants (78.8%) had ever smoked a cigarette, and 115 (71.9%) had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Participants who previously smoked reported a mean (SD) of 12.6 (9.6) cigarettes daily. No participant reported smoking tobacco in the 30 days before enrollment, and all baseline carbon monoxide levels were less than 10 ppm. Participants who had ever smoked reported a median (IQR) of 2 (0.5-5.0) years since their last cigarette. Among 126 participants who had ever smoked cigarettes, 119 (94.4%) identified methods used in their most recent quit attempt, and 98 of 119 (82.4%) cited e-cigarettes.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants by Treatment Group.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytisinicline (n = 107) | Placebo (n = 53) | |

| Age, y | ||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 33.6 (11.2) [18-62] | 33.5 (10.9) [20-65] |

| Quartiles | ||

| <24.5 | 28 (26.2) | 12 (22.6) |

| ≥24.5 to <31 | 22 (20.6) | 13 (24.5) |

| ≥31 to <40 | 27 (25.2) | 15 (28.3) |

| ≥40 | 30 (28.0) | 13 (24.5) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 54 (50.5) | 29 (54.7) |

| Male | 53 (49.5) | 24 (45.3) |

| Racea | ||

| Asian | 3 (2.8) | 3 (5.7) |

| Black or African American | 9 (8.4) | 5 (9.4) |

| White | 92 (86.0) | 43 (81.1) |

| Another | 3 (2.8) | 2 (3.8) |

| Hispanic ethnicitya | 4 (3.7) | 5 (9.4) |

| Cigarette use | ||

| History of any cigarette smoking | 86 (80.4) | 40 (75.5) |

| Smoked ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 77 (72.0) | 38 (71.7) |

| Smoked a cigarette in past 30 d | 0 | 0 |

| Expired carbon monoxide level, mean (SD), ppm | 3.0 (2.2) | 3.7 (2.3) |

| E-cigarette use | ||

| Age at first e-cigarette use, y | ||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 29.4 (11.4) [12-58] | 28.2 (11.3) [16-60] |

| Median (IQR) | 27 (20-37) | 24 (20-33) |

| Device type most often used in past 30 d | ||

| Disposable | 38 (35.5) | 29 (54.7) |

| Rechargeable | 69 (64.5) | 24 (45.3) |

| Prefilled pod | 33 (30.8) | 14 (26.4) |

| User-filled pod | 18 (16.8) | 6 (11.3) |

| User-filled tank | 18 (16.8) | 4 (7.5) |

| E-cigarette liquid flavors used in past 30 db | ||

| Fruit | 61 (57.0) | 33 (62.3) |

| Mint or menthol | 36 (33.6) | 17 (32.1) |

| Candy, dessert, or sweet | 17 (15.9) | 3 (5.7) |

| Tobacco | 11 (10.3) | 4 (7.5) |

| E-cigarette nicotine dependence scale, mean (SD)c | 12.9 (4.1) | 13.5 (3.9) |

| Saliva cotinine, mean (SD), ng/mLd | 316.2 (182.1) | 315.5 (176.9) |

| Made a prior e-cigarette quit attempt | 50 (46.7) | 33 (62.3) |

| Desire to quit vaping now, median (IQR)e | 4 (4-5) | 5 (4-5) |

| Confidence to quit vaping now, median (IQR)f | 4 (3-4) | 4 (3-4) |

| Most important reason for current quit attempt | ||

| Health effects | 67 (62.6) | 35 (66.0) |

| Money/cost | 18 (16.8) | 5 (9.4) |

| Freedom from addiction | 12 (11.2) | 9 (17.0) |

| For another person | 5 (4.7) | 3 (5.7) |

| Other | 5 (4.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| HADS questionnaire total score, mean (SD)g | 7.0 (4.8) | 7.9 (5.3) |

Abbreviation: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Race and ethnicity were assessed by a participant’s response to a fixed-category question. Races in the another category were grouped together owing to small sample sizes.

Multiple responses were allowed to the question about flavors used in the past 30 days.

As measured by the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index,24 a 10-item scale with a range of scores from 0 to 20. Higher scores indicate greater dependence (not dependent [score 0-3], 4 participants; low dependence [score 4-8], 16 participants; medium dependence [score 9-12], 45 participants; high dependence, [score ≥13], 94 participants).

Data were missing for 2 participants in the cytisinicline group and 1 in the placebo group.

Scale with scores from 1 to 5 (not at all to very much).

Scale with scores from 1 to 5 (not at all to extremely).

HADS is a 14-item scale with a range of scores from 0 to 42.23 Higher scores indicate more symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Participants had begun vaping at a median (IQR) age of 26 (20-36) years (range, 12-60 years) and had a medium to high level of e-cigarette dependence (Table 1). Participants cited rechargeable (n = 93 [58.1%]) and disposable (n = 67 [41.9%]) devices as their most often used product. Past-month e-liquid flavors used included fruit (n = 94 [58.8%]), menthol or mint (n = 53 [33.1%]), candy or sweet (n = 20 [12.5%]), and tobacco (n = 15 [9.4%]).

Of the 160 participants, 83 (51.9%) had previously tried to quit nicotine e-cigarettes (median [IQR] prior attempts, 2 [1.0-4.0]). Most had tried to quit without treatment, but 16 of the 83 (19.3%) had used a nicotine replacement medication. The most important reason cited by participants for attempting to quit vaping now was health (n = 102 [63.8%]), followed by cost (n = 23 [14.4%]), and freedom from addiction (n = 21 [13.1%]). Eighty participants (50.0%) rated their motivation to quit now as “very much,” but only 39 (24.4%) were “extremely confident” of their ability to do so.

Effectiveness

A higher proportion of participants assigned to cytisinicline than to placebo achieved the primary outcome, biochemically confirmed continuous e-cigarette abstinence during the last 4 weeks of treatment (weeks 9-12: 34 of 107 [31.8%] vs 8 of 53 [15.1%]; odds ratio [OR], 2.64; 95% CI, 1.06-7.10; P = .04). Analyses of secondary end points produced results with similar directionality but without statistical significance for the difference between groups (Table 2). Those in the cytisinicline group vs placebo group reported more biochemically confirmed continuous abstinence extending 4 weeks posttreatment (weeks 9-16: 25 of 107 [23.4%] vs 7 of 53 [13.2%]; OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 0.82-5.32; P = .15).

Table 2. Biochemically Confirmed Continuous E-Cigarette Abstinence by Treatment Group.

| Outcome measurea | No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytisinicline (n = 107) | Placebo (n = 53) | |||

| Primary outcome: weeks 9-12 (end of treatment)b | 34 (31.8) | 8 (15.1) | 2.64 (1.06-7.10) | .04 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Before end of treatment periodc | ||||

| Weeks 3-6 | 26 (24.3) | 8 (15.1) | 1.81 (0.77-4.55) | .22 |

| Weeks 6-9 | 33 (30.8) | 9 (17.0) | 2.18 (0.97-5.20) | .09 |

| Sustained after the end of treatment (weeks 9-16) | 25 (23.4) | 7 (13.2) | 2.00 (0.82-5.32) | .15 |

Abstinence from e-cigarette smoking was defined as a self-report of no cigarettes since last visit that was confirmed by a saliva cotinine level less than 10 ng/mL. Participants with a saliva cotinine level higher than 10 ng/mL or missing outcome data were counted as not abstinent from e-cigarettes.

E-cigarette abstinence reported and validated at weeks 9, 10, 11, and 12.

E-cigarette abstinence reported and validated at weeks 3, 4, 5, and 6 or at weeks 6, 7, 8, and 9.

Effect modification analyses using subgroups defined by age, sex, race, cigarette smoking history, age of first e-cigarette use, e-cigarette dependence, and e-liquid flavor used found no evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of cytisinicline on the primary outcome, using a criterion of P ≤ .10 for the interaction of baseline characteristics by drug assignment (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Verified past 7-day e-cigarette abstinence was consistently higher in the cytisinicline group than in the placebo group (Figure 2A). Mean and median saliva cotinine levels, which measured any nicotine use, were similar at baseline, declined substantially by week 2, and remained below baseline levels through 4 weeks posttreatment (Figure 2B). Twelve participants (7.5%) had evidence suggestive of tobacco smoking during the last 4 weeks of treatment; there was no statistically significant difference between cytisinicline (7 of 107 [6.5%]) and placebo (5 of 53 [9.4%]) groups. Adding the posttreatment period did not change the finding: 14 participants (8.8%) had evidence of smoking between weeks 9 and 16, with no statistically significant group difference (cytisinicline, 8 of 107 [7.5%]; placebo, 6 of 53 [11.3%]). Eleven of 14 participants (78.6%) with evidence of combustible tobacco use in the trial were former smokers.

Figure 2. Other Measures of Treatment Effectiveness During and After Treatment.

A, At each week, participants reported whether they had used an e-cigarette in the past 7 days (or since the last visit at week 16). A participant was classified as abstinent for that week if no e-cigarette use was reported and was biochemically confirmed. Missing assessments were classified as nonabstinent to include all randomized. The prevalence probabilities and exact 95% CIs (error bars) were estimated at each week. B, Saliva cotinine samples were collected at each week during treatment and at 16-week follow-up. The figure compares the saliva cotinine values of 157 participants randomized to cytisinicline (n = 105) or placebo (n = 52). Circles represent mean values at each week. Diamonds represent median values. Numbers below the x-axis indicate the number of participants in each randomized group who contributed data for analysis at each visit. The cotinine assay has a lower limit of detection of 1 ng/mL, and the figure illustrates that after randomization, materially more participants in the cytisinicline group had assay results below the limit of detection.

Safety

Overall, treatment-emergent adverse events reported by participants were similar between groups: 54 (50.9%) in the cytisinicline group and 29 (54.7%) in the placebo group (Table 3). Adverse events were attributed to the study drug in 30 participants (28.3%) receiving cytisinicline and 10 (18.9%) receiving placebo. No serious adverse events were reported. All but 1 of the nonserious adverse events had mild or moderate severity. The most common (>5%) adverse events among those in the cytisinicline group were abnormal dreams, insomnia, anxiety, headache, fatigue, and upper respiratory tract infection (Table 3). Nausea occurred in 5 participants (4.7%) receiving cytisinicline compared with 6 (11.3%) in the placebo group. An adverse event led to study drug treatment discontinuation in 4 participants (3.8%) receiving cytisinicline and 3 (5.7%) receiving placebo. No clinically meaningful changes in blood pressure, heart rate, laboratory values, or electrocardiogram results occurred during treatment.

Table 3. Summary of Adverse Events by Treatment Group.

| Outcome measure | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytisinicline (n = 106)a | Placebo (n = 53) | |

| Any treatment-emergent adverse event | 54 (50.9) | 29 (54.7) |

| Any treatment-related adverse event | 30 (28.3) | 10 (18.9) |

| Any serious adverse event | 0 | 0 |

| Drug discontinuation due to an adverse event | 4 (3.8) | 3 (5.7) |

| Treatment-emergent adverse events, No./total No. (%) | ||

| Mild | 92/119 (77.3) | 38/68 (55.9) |

| Moderate | 26/119 (21.8) | 30/68 (44.1) |

| Severe | 1/119 (0.8) | 0 |

| Most frequent treatment-emergent adverse eventsb | ||

| Abnormal dreams | 13 (12.3) | 1 (1.9) |

| Insomnia | 11 (10.4) | 1 (1.9) |

| Anxiety | 10 (9.4) | 4 (7.5) |

| Headache | 7 (6.6) | 5 (9.4) |

| Fatigue | 6 (5.7) | 2 (3.8) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 6 (5.7) | 3 (5.7) |

| Nausea | 5 (4.7) | 6 (11.3) |

| COVID-19 | 3 (2.8) | 6 (11.3) |

Using safety set for analysis of safety outcomes. One participant in the cytisinicline group took no study medication, so the denominator is 106.

Includes all treatment-emergent adverse events reported by 5% or more of participants in any study arm, using MedDRA preferred term. Listed in descending order for cytisinicline.

Discussion

This multisite phase 2 placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial tested the efficacy and safety of 12 weeks of cytisinicline, combined with behavioral support, to aid nicotine e-cigarette cessation among adults who vaped nicotine daily, did not smoke, and sought to quit vaping. Cytisinicline treatment more than doubled the odds of achieving the primary outcome, biochemically confirmed continuous e-cigarette abstinence at the end of treatment (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.06-7.10; P = .04). There was no evidence that the effect differed by subgroups defined by age, sex, race, history of cigarette smoking, e-cigarette dependence, age of vaping initiation, or e-liquid flavor used. Cytisinicline was well tolerated by participants, who reported no treatment-related serious adverse events and few troubling adverse effects, and adhered well to the treatment schedule.

Secondary study outcomes supported the finding of an overall benefit of cytisinicline over placebo to aid nicotine vaping cessation. Participants assigned to cytisinicline consistently reported more past-week e-cigarette abstinence throughout the treatment period and remained abstinent for 4 weeks after treatment ended. Differences in the secondary end points did not achieve statistical significance in part due to the small sample size. These promising findings warrant confirmation in a trial with a larger sample size and longer duration of posttreatment follow-up.

Attempting to quit vaping could potentially lead some individuals, especially former cigarette smokers, to transition from e-cigarettes back to smoking cigarettes or to dual use of both products to sustain nicotine dependence. During the last 4 weeks of treatment, 7.5% of participants met criteria for possible cigarette smoking, with similar rates in cytisinicline and placebo groups. Cytisinicline used for vaping cessation does not appear to increase the risk of relapse to smoking or dual use, a finding consistent with cytisinicline’s demonstrated efficacy for smoking cessation and its hypothesized method of action as a partial nicotine receptor agonist that blocks the reinforcement of smoking.

This study adds to the meager evidence of pharmacotherapy for vaping cessation. To our knowledge, it is the first trial to test cytisinicline for this indication, and it did so using a new dosing regimen with demonstrated smoking cessation efficacy in a US population.17 The only previously reported placebo-controlled randomized vaping cessation trial tested varenicline, a smoking cessation aid whose mechanism of action resembles cytisinicline.8 Both trials administered drugs for 12 weeks, accompanied by behavioral support, and assessed cotinine-verified abstinence vs placebo at the end of treatment and after treatment ended. Varenicline’s end-of-treatment OR of 2.67 (95% CI, 1.25-5.68) resembles cytisinicline’s OR of 2.64 (95% CI, 1.06-7.10) in this trial. While both drugs were well tolerated, nausea was much less frequent in the cytisinicline trial (4.7%) than in the varenicline trial (20%). Study participants also differed. Trial participants receiving varenicline were older (mean age, 52 years), all former smokers, and primarily used tanktype devices with tobacco-flavored e-liquids. The present trial of cytisinicline enrolled a younger sample of participants who used devices and flavors more representative of current e-cigarette use in the US.3,25,26 In young adults, an open-label pilot trial of nicotine replacement found potential vaping cessation efficacy,9 and text messaging was effective in a large trial.10 Promising data have come from pilot trials of other behavioral treatments.11,12,13

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations in overall generalizability and statistical power to detect differences, specifically in subgroups. The predominantly White study sample limits generalizability to individuals of other races; this may partly reflect the higher prevalence of e-cigarette use among White non-Hispanic adults relative to other racial and ethnic groups.3 Exclusion criteria for serious mental illness, unstable cardiovascular disease, drug use other than cannabis, age younger than 18 years, and dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes limit generalizability of the findings to these groups. Dual users were excluded to isolate the effect of cytisinicline for quitting nicotine vaping. The trial’s size was insufficient to detect uncommon adverse events, although cytisinicline has been used for decades as a cessation aid by millions in Central and Eastern Europe with a good safety record.15 Participants were followed up for only 4 weeks after the study drug treatment ended; the trial cannot assess a longer period of posttreatment abstinence. The intensity of behavioral support and attention to treatment adherence provided likely exceeds what health care settings typically provide.

Conversely, the importance of this study is to demonstrate the potential of cytisinicline to be a nonnicotine treatment for quitting nicotine vaping. This might be particularly attractive to adults who switched from smoking to vaping to reduce health risks and subsequently want to end their addiction to nicotine. Cytisinicline’s low adverse effect profile (especially nausea) may lead to high treatment adherence and facilitate successful quit attempts. Furthermore, the efficacy of cytisinicline for smoking cessation16,17 suggests that it might be a treatment option for individuals seeking to quit both smoking and vaping (dual users).

Conclusions

This double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial provides strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that cytisinicline has efficacy and excellent tolerability as a treatment to help adults quit vaping nicotine. While these findings warrant confirmation in a phase 3 trial with a larger sample size and longer follow-up, they are consistent with the demonstrated efficacy of cytisinicline for cigarette smoking cessation.16,17 For individuals seeking to quit vaping, cytisinicline might fill the existing gap in pharmacologic treatments and enhance the emerging evidence of efficacy of behavioral treatments for vaping cessation.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure 1. Effect Modifier Analysis of Verified Continuous Vaping Cessation during Weeks 9-12

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL, eds. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. The National Academies Press; 2018. doi: 10.17226/24952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Simonavicius E, Robson D. Vaping in England: evidence update February 2021. Public Health England . February 23, 2021. Accessed March 26, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaping-in-england-evidence-update-february-2021

- 3.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(18):475-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanford BT, Brownstein NC, Baker NL, et al. Shift from smoking cigarettes to vaping nicotine in young adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(1):106-108. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen RL, Steinberg ML. Interest in quitting e-cigarettes among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):857-858. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer AM, Smith TT, Nahhas GJ, et al. Interest in quitting e-cigarettes among adult e-cigarette users with and without cigarette smoking history. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e214146. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garey L, Mayorga NA, Peraza N, et al. Distinguishing characteristics of e-cigarette users who attempt and fail to quit: dependence, perceptions, and affective vulnerability. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80(1):134-140. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Ahluwalia JS, et al. Varenicline and counseling for vaping cessation: a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02919-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer AM, Carpenter MJ, Rojewski AM, Haire K, Baker NL, Toll BA. Nicotine replacement therapy for vaping cessation among mono and dual users: a mixed methods preliminary study. Addict Behav. 2023;139:107579. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham AL, Amato MS, Cha S, Jacobs MA, Bottcher MM, Papandonatos GD. Effectiveness of a vaping cessation text message program among young adult e-cigarette users: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(7):923-930. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer AM, Tomko RL, Squeglia LM, et al. A pilot feasibility study of a behavioral intervention for nicotine vaping cessation among young adults delivered via telehealth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;232:109311. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raiff BR, Newman ST, Upton CR, Burrows CA. The feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a remotely delivered, financial-incentive intervention to initiate vaping abstinence in young adults. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;30(5):632-641. doi: 10.1037/pha0000468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan N, Berg CJ, Le D, Ahluwalia J, Graham AL, Abroms LC. A pilot randomized controlled trial of automated and counselor-delivered text messages for e-cigarette cessation. Tob Prev Cessat. 2023;9(February):04. doi: 10.18332/tpc/157598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridley D. J&J’s Nicorette becomes world’s first licensed vaping and smoking cessation therapy. HBW Insight . January 24, 2023. Accessed October 29, 2023. https://hbw.citeline.com/RS153291/JJs-Nicorette-Becomes-Worlds-First-Licensed-Vaping-And-Smoking-Cessation-Therapy

- 15.Tutka P, Vinnikov D, Courtney RJ, Benowitz NL. Cytisine for nicotine addiction treatment: a review of pharmacology, therapeutics and an update of clinical trial evidence for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2019;114(11):1951-1969. doi: 10.1111/add.14721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livingstone-Banks J, Fanshawe TR, Thomas KH, et al. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;5(5):CD006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, Prochaska J, et al. Cytisinicline for smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(2):152-160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.10042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West R, Zatonski W, Cedzynska M, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of cytisine for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1193-1200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker N, Howe C, Glover M, et al. Cytisine versus nicotine for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(25):2353-2362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pastorino U, Ladisa V, Trussardo S, et al. Cytisine therapy improved smoking cessation in the randomized Screening and Multiple Intervention on Lung Epidemics lung cancer screening trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(11):1276-1286. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.iScreen OFD cotinine test device. Package insert. Alere. Accessed October 29, 2023. https://cliawaived.com/amfile/file/download/file/614/product/4630/

- 22.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, et al. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking e-cigarette users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):186-192. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali FRM, Seidenberg AB, Crane E, Seaman E, Tynan MA, Marynak K. E-cigarette unit sales by product and flavor type, and top-selling brands, United States, 2020-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(25):672-677. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7225a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birdsey J, Cornelius M, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among U.S. middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(44):1173-1182. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7244a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure 1. Effect Modifier Analysis of Verified Continuous Vaping Cessation during Weeks 9-12

Data Sharing Statement