Abstract

The OMICs cascade describes the hierarchical flow of information through biological systems. The epigenome sits at the apex of the cascade, thereby regulating the RNA and protein expression of the human genome and governs cellular identity and function. Genes that regulate the epigenome, termed epigenes, orchestrate complex biological signaling programs that drive human development. The broad expression patterns of epigenes during human development mean that pathogenic germline mutations in epigenes can lead to clinically significant multi-system malformations, developmental delay, intellectual disabilities, and stem cell dysfunction. In this review, we refer to germline developmental disorders caused by epigene mutation as “chromatinopathies”. We curated the largest number of human chromatinopathies to date and our expanded approach more than doubled the number of established chromatinopathies to 179 disorders caused by 148 epigenes. Our study revealed that 20.6% (148/720) of epigenes cause at least one chromatinopathy. In this review, we highlight key examples in which OMICs approaches have been applied to chromatinopathy patient biospecimens to identify underlying disease pathogenesis. The rapidly evolving OMICs technologies that couple molecular biology with high-throughput sequencing or proteomics allow us to dissect out the causal mechanisms driving temporal-, cellular-, and tissue-specific expression. Using the full repertoire of data generated by the OMICs cascade to study chromatinopathies will provide invaluable insight into the developmental impact of these epigenes and point toward future precision targets for these rare disorders.

Introduction

The human body is made of trillions of cells and hundreds of unique cell types, which arose from a single cell. The nucleus of the primordial single cell: the zygote, includes two sets of instructions that guide human development: the genome and the epigenome. The genome (i.e., deoxyribonucleic acid; DNA) remains constant across all cells in an organism while the epigenome varies between cells and directs cell-type specification by controlling DNA organization through chemical modifications (Deans and Maggert 2015). Each human possesses thousands of cell-type-specific epigenomes (Moss et al. 2018; Horvath 2013; Mo et al. 2015) that are inherited during cell division (Lacal and Ventura 2018).

This review covers core concepts in gene regulation, epigenomics, and human disease. We collectively refer to human developmental disorders caused by germline mutations in genes that control epigenome function as “chromatinopathies''. Each chromatinopathy is considered a rare disorder, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States (Hoskins 2022). First, we define the epigenome and use large-scale data to expand the number of monogenic disorders defined as chromatinopathy syndromes. Previous reviews have restricted the definition of chromatinopathies to neurodevelopmental disorders caused by pathogenic mutations in canonical chromatin-modifier or chromatin-remodeler genes (Berdasco and Esteller 2013; Bjornsson 2015; Fahrner and Bjornsson 2019; Van Gils et al. 2021; Luperchio et al. 2021). The second major focus in the review is on -OMICs technology which is used to elucidate causal mechanisms driving these rare and severe developmental disorders. We review established and emerging molecular technologies designed to assess layers in the -OMICs cascade and how these assays have been implemented to investigate the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of select chromatinopathies.

Defining the epigenome

The epigenome was originally defined as the study of heritable changes in gene expression and function which do not alter the DNA (Wu and Morris 2001). In Fig. 1, a key function of the epigenome is to regulate the three-dimensional (3D) organization of chromatin to partition the genome such that only a fraction of genomic DNA is physically accessible to biological machinery for transcription into ribonucleic acid (RNA). In combination with the human genome, this enables the epigenome to control the spatial and temporal timing of gene expression in a cell-specific manner. There are five major chemical modifications present on chromatin that influence the cell’s epigenetic state: DNA methylation, histone methylation, histone acetylation, histone phosphorylation, and histone ubiquitination as well as dozens of low-abundance chemical modifications (Ludwig and Bintu 2019). In this review, we define ‘epigenes’ as genes encoding proteins that affect a cell's epigenome (Sadakierska-Chudy et al. 2015; Medvedeva et al. 2015). These epigenes can be divided into four groups: (1) ‘chromatin-modifiers’ are proteins that interact and/or regulate histone post-translational modifications, (2) ‘chromatin remodelers’ are proteins that regulate the structure/organization of chromatin, (3) proteins that modulate chemical modification present on DNA/RNA, and lastly (4) accessory proteins that are essential in epigenome-altering processes (Sadakierska-Chudy et al. 2015; Sadakierska-Chudy and Filip 2015; Javaid and Choi 2017) and their functions are reviewed in Medvedeva et al.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of omics layers in biological systems. A Snapshot of gene regulation in Eukaryotic cell by the epigenome and genome. DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) write/deposit DNA methylation, while ten-eleven translocation (TETs) enzymes erase/remove methyl-groups from DNA. While different classes of enzymes write/deposit, erase/remove, and maintain the 4 major histone post-translational modifications shown above. B Snapshot of neurons communicating to product a cellular phenotype that can be assessed through electrophysiology to measure rate of synaptic transmission. Synaptic transmission can be driven by changes in histone acetylation, which is a metabolic reaction mediated by genes encoding lysine (K) acetyltransferases (KATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) to cause changes in gene expression which translates to changes in protein abundance within neurons

In addition to transcriptomic regulation through histone post-translational modifications, transcript expression can be regulated through direct post-transcriptional modifications to nucleic acids (i.e., DNA/RNA). For example, some epigenes modulate the presence of chemical modifications on messenger (mRNA) and regulate their stability within a cell, thereby influencing gene expression (Chen et al. 2016, 2020; Roundtree et al. 2017). However, significantly fewer chemical modifications are known to exist on DNA/RNA as compared to histones (Ludwig and Bintu 2019). Nucleic acid methylation occurring at cytosine or adenine nucleotides is the most abundant and best studied epigenetic chemical modification on DNA. However the proteins responsible for writing, erasing, or reading RNA methylation are still being identified (Boo and Kim 2020). The last group of epigenes indirectly function in epigenome-altering processes by serving as chaperones, scaffolds, or cofactors (Medvedeva et al. 2015). Thus, these epigenes collectively regulate an organism’s epigenome through a multitude of biological and molecular processes. While the epigene definition here does not explicitly include non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), it is important to highlight that ncRNAs are critical gene regulatory elements that regulate fundamental processes, such as X-inactivation (Engreitz et al. 2013; Chitiashvili et al. 2020), and are reviewed in (Beermann et al. 2016). This review primarily focuses on genetic syndromes caused by germline mutations in protein-coding epigenes (Berdasco and Esteller 2013).

Expanding the chromatinopathy landscape through data mining

A comprehensive study of epigenetic factors identified 720 epigenes after filtering out 95 genes that encode histones and protamines (Medvedeva et al. 2015). To illuminate the extent to which pathogenic epigene mutations cause monogenic developmental disorders, a.k.a chromatinopathies, we filtered 720 epigenes against the largest publicly-available human geno-phenotype database: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (Hamosh et al. 2005; Amberger et al. 2015). We found that 29.6% (213/720) of epigenes are associated with at least one human morbidity. We identified these genes by mapping their HGNC IDs to OMIM’s morbid accession IDs using the ensembl database for human genes (GRCh38.p13; downloaded June 2022 through the R package biomaRt (Smedley et al. 2009). Collectively, these 213 unique epigenes are mapped to 322 OMIM morbid accession IDs, resulting in a list of 322 genotype–phenotype pairs that contained repeated elements due to the polygenic-nature of some OMIM phenotypes and the pleiotropic-nature of some epigenes.

Therefore, to generate a high-confidence list of chromatinopathies shown in Table 1, we then filtered these 322 genotype–phenotype pairs to remove entries that were not monogenic developmental disorders/syndromes. Specifically, genotype–phenotype entries were removed if the OMIM phenotype: (1) did not have a clear mode of inheritance, (2) was caused by somatic mutations, or (3) was not a syndromic developmental disorder. After filtering these 322 genotype–phenotype pairs, we found that 20.6% (148/720) of all epigenes cause at least one chromatinopathy (Table 1). Specifically, we identified 179 chromatinopathies that are caused by pathogenic germline mutations in 148 distinct epigenes using our data-mining strategy. This doubles previous estimates, which report 40–70 chromatinopathy-causing epigenes (Fahrner and Bjornsson 2019; Valencia and Pașca 2022). The ability to expand the current Chromatinopathy landscape, which we extensively cataloged in Table 1, is fueled by two evolving sources of information: (1) the continuous identification of novel genes associated with genetic syndromes and (2) the elucidation of the mechanistic basis underlying a protein’s capacity to influence gene regulation through the epigenome. Accordingly, we expect the proportion of chromatinopathy-causing epigenes will increase as more children are diagnosed using state-of-the-art genome sequencing technologies.

Table 1.

Summary of 179 Chromatinopathies caused by germline mutations in 148 epigenes

| HGNC ID: | HGNC Symbol: | Epigenome Function: | OMIM ID: | Inheritance: | Condition: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 132 | ACTB | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 243,310 | AD | BARAITSER–WINTER SYNDROME 1; BRWS1. (Alternative name: FRYNS–AFTIMOS SYNDROME) |

| 160 | ACTL6B | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 618,468 | AR | DEVELOPMENTAL AND EPILEPTIC ENCEPHALOPATHY 76; DEE76 |

| 160 | ACTL6B | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 618,470 | AD | INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH SEVERE SPEECH AND AMBULATION DEFECTS; IDDSSAD |

| 15,766 | ADNP | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 615,873 | AD | HELSMOORTEL–VAN DER AA SYNDROME; HVDAS |

| 13,203 | AICDA | DNA modification | 605,258 | AR | HYPER-IgM SYNDROME 2 |

| 360 | AIRE | Histone modification read, TF | 240,300 | AD, AR | AUTOIMMUNE POLYENDOCRINE SYNDROME, TYPE I, WITH OR WITHOUT REVERSIBLE METAPHYSEAL DYSPLASIA; APS1 |

| 11,110 | ARID1A | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 614,607 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 2; CSS2 |

| 18,040 | ARID1B | Histone modification write | 135,900 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 1; CSS1 |

| 18,037 | ARID2 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 617,808 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 6; CSS6 |

| 19,088 | ASH1L | Histone modification write | 617,796 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 52; MRD52 |

| 18,318 | ASXL1 | Histone modification erase, Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 605,039 | AD | BOHRING–OPITZ SYNDROME; BOS |

| 23,805 | ASXL2 | Histone modification read | 617,190 | AD | SHASHI–PENA SYNDROME; SHAPNS |

| 29,357 | ASXL3 | Scaffold protein, Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 615,485 | AD | BAINBRIDGE–ROPERS SYNDROME; BRPS |

| 795 | ATM | Histone modification write | 208,900 | AR | LOUIS–BAR SYNDROME |

| 3033 | ATN1 | Histone modification erase cofactor | 125,370 | AD | HAW RIVER SYNDROME; HRS |

| 882 | ATR | Histone modification write | 210,600 | AR | SECKEL SYNDROME 1; SCKL1 |

| 882 | ATR | Histone modification write | 614,564 | AD | CUTANEOUS TELANGIECTASIA AND CANCER SYNDROME, FAMILIAL; FCTCS |

| 886 | ATRX | Chromatin remodeling | 301,040 | XLD | ALPHA-THALASSEMIA/MENTAL RETARDATION SYNDROME, X-LINKED; ATRX |

| 886 | ATRX | Chromatin remodeling | 309,580 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION-HYPOTONIC FACIES SYNDROME, X-LINKED, 1; MRXHF1. (Alternative names: SMITH–FINEMAN–MYERS SYNDROME 1, CARPENTER–WAZIRI SYNDROME, CHUDLEY–LOWRY SYNDROME, HOLMES–GANG SYNDROME) |

| 950 | BAP1 | Histone modification erase, Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 614,327 | AD | TUMOR PREDISPOSITION SYNDROME; TPDS |

| 20,893 | BCOR | Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 300,166 | XLD | MICROPHTHALMIA, SYNDROMIC 2; MCOPS2 |

| 25,657 | BCORL1 | Histone modification erase cofactor | 301,029 | XLR | SHUKLA–VERNON SYNDROME; SHUVER |

| 3581 | BPTF | Chromatin remodeling | 617,755 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH DYSMORPHIC FACIES AND DISTAL LIMB ANOMALIES; NEDDFL |

| 1100 | BRCA1 | Histone modification write cofactor, TF | 617,883 | AR | FANCONI ANEMIA, COMPLEMENTATION GROUP S; FANCS |

| 1101 | BRCA2 | Histone modification write | 605,724 | AR | FANCONI ANEMIA, COMPLEMENTATION GROUP D1; FANCD1;;FAD1 |

| 14,255 | BRPF1 | Histone modification read | 617,333 | AD | INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH DYSMORPHIC FACIES AND PTOSIS; IDDDFP |

| 17,342 | BRWD3 | Histone modification read | 300,659 | XLR | X-LINKED INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER 93; XLID93 |

| 1744 | CDC6 | Chromatin remodeling | 613,805 | AR | MEIER-GORLIN SYNDROME 5; MGORS5 |

| 16,783 | CDC73 | Histone modification write cofactor | 145,001 | AD | HYPERPARATHYROIDISM-JAW TUMOR SYNDROME; HPT-JT |

| 1915 | CHD1 | Chromatin remodeling | 617,682 | AD | PILAROWSKI–BJORNSSON SYNDROME; PILBOS |

| 1917 | CHD2 | Chromatin remodeling | 615,369 | AD | DEVELOPMENTAL AND EPILEPTIC ENCEPHALOPATHY 94; DEE94 |

| 1918 | CHD3 | Chromatin remodeling | 618,205 | AD | SNIJDERS BLOK–CAMPEAU SYNDROME; SNIBCPS |

| 1919 | CHD4 | Chromatin remodeling | 617,159 | AD | SIFRIM–HITZ–WEISS SYNDROME; SIHIWES |

| 20,626 | CHD7 | Chromatin remodeling | 214,800 | AD | CHARGE SYNDROME |

| 20,626 | CHD7 | Chromatin remodeling | 612,370 | AD | HYPOGONADOTROPIC HYPOGONADISM 5 WITH OR WITHOUT ANOSMIA; HH5 |

| 1974 | CHUK | Histone modification write | 613,630 | AR | FETAL ENCASEMENT SYNDROME |

| 1974 | CHUK | Histone modification write | 619,339 | AR | BARTSOCAS–PAPAS SYNDROME 2; BPS2 |

| 18,688 | CRB2 | Histone modification read | 219,730 | AR | VENTRICULOMEGALY WITH CYSTIC KIDNEY DISEASE; VMCKD. (Alternative name: genetic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome) |

| 18,688 | CRB2 | Histone modification read | 616,220 | AR | FOCAL SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS 9; FSGS9. (Alternative name: genetic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome) |

| 2348 | CREBBP | Histone modification write | 180,849 | AD | RUBINSTEIN–TAYBI SYNDROME 1; RSTS1 |

| 2348 | CREBBP | Histone modification write | 618,332 | AD | MENKE–HENNEKAM SYNDROME 1; MKHK1 |

| 2457 | CSNK2A1 | Histone modification | 617,062 | AD | OKUR–CHUNG NEURODEVELOPMENTAL SYNDROME; OCNDS |

| 2494 | CTBP1 | Chromatin remodeling | 194,190 | AD | WOLF–HIRSCHHORN SYNDROME; WHS |

| 2494 | CTBP1 | Chromatin remodeling | 617,915 | AD | HYPOTONIA, ATAXIA, DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY, AND TOOTH ENAMEL DEFECT SYNDROME; HADDTS |

| 13,723 | CTCF | Chromatin remodeling, TF | 615,502 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 21; MRD21 |

| 2553 | CUL3 | Histone modification write | 619,239 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH OR WITHOUT AUTISM OR SEIZURES; NEDAUS |

| 2555 | CUL4B | Histone modification write | 300,354 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC, CABEZAS TYPE; MRXSC. (Alternative name: CABEZAS SYNDROME) |

| 2717 | DDB1 | Histone modification write | 619,426 | AD | WHITE–KERNOHAN SYNDROME; WHIKERS |

| 2976 | DNMT1 | DNA modification | 604,121 | AD | CEREBELLAR ATAXIA, DEAFNESS, AND NARCOLEPSY, AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT; ADCADN |

| 2976 | DNMT1 | DNA modification | 614,116 | AD | NEUROPATHY, HEREDITARY SENSORY, TYPE IE; HSN1E |

| 2978 | DNMT3A | DNA modification | 615,879 | AD | TATTON–BROWN–RAHMAN SYNDROME; TBRS |

| 2978 | DNMT3A | DNA modification | 618,724 | AD | HEYN–SPROUL–JACKSON SYNDROME; HESJAS |

| 2979 | DNMT3B | DNA modification | 242,860 | AR | IMMUNODEFICIENCY-CENTROMERIC INSTABILITY-FACIAL ANOMALIES SYNDROME 1; ICF1 |

| 9964 | DPF2 | Chromatin remodeling | 618,027 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 7; CSS7 |

| 3188 | EED | Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 617,561 | AD | COHEN–GIBSON SYNDROME; COGIS |

| 24,650 | EHMT1 | Histone modification write | 610,253 | AD | KLEEFSTRA SYNDROME 1; KLEFS1 |

| 5959 | ELP1 | Scaffold protein | 223,900 | AR | NEUROPATHY, HEREDITARY SENSORY AND AUTONOMIC, TYPE III; HSAN3. (Alternative name: RILEY–DAY SYNDROME) |

| 3373 | EP300 | Histone modification write | 613,684 | AD | RUBINSTEIN–TAYBI SYNDROME 2; RSTS2 |

| 3373 | EP300 | Histone modification write | 618,333 | AD | MENKE–HENNEKAM SYNDROME 2; MKHK2 |

| 3438 | ERCC6 | Chromatin remodeling | 133,540 | AR | COCKAYNE SYNDROME B; CSB |

| 3438 | ERCC6 | Chromatin remodeling | 214,150 | AR | CEREBROOCULOFACIOSKELETAL SYNDROME 1; COFS1 |

| 3438 | ERCC6 | Chromatin remodeling | 278,800 | AR | DE SANCTIS–CACCHIONE SYNDROME |

| 3438 | ERCC6 | Chromatin remodeling | 600,630 | AR | UV-SENSITIVE SYNDROME 1; UVSS1 |

| 17,097 | EXOSC2 | Scaffold protein, RNA modification | 617,763 | AR | Retinitis pigmentosa-hearing loss-premature aging-short stature-facial dysmorphism syndrome |

| 3519 | EYA1 | Histone modification erase | 113,650 | AD | BRANCHIOOTORENAL SYNDROME 1; BOR1. (Alternative name: MELNICK–FRASER SYNDROME) |

| 3519 | EYA1 | Histone modification erase | 166,780 | AD | OTOFACIOCERVICAL SYNDROME 1; OTFCS |

| 3519 | EYA1 | Histone modification erase | 602,588 | AD | BRANCHIOOTIC SYNDROME 1; BOS1 |

| 3527 | EZH2 | Histone modification write, Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 277,590 | AD | WEAVER SYNDROME; WVS |

| 3823 | FOXP1 | Recruits specific chromatin-modifying complexes with HDAC activity, TF | 613,670 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION WITH LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT AND WITH OR WITHOUT AUTISTIC FEATURES |

| 13,875 | FOXP2 | Recruits specific chromatin-modifying complexes with HDAC activity, TF | 602,081 | AD | SPEECH AND LANGUAGE DISORDER WITH OROFACIAL DYSPRAXIA |

| 6106 | FOXP3 | Recruits specific chromatin-modifying complexes with HDAC activity, TF | 304,790 | XLR | IMMUNODYSREGULATION, POLYENDOCRINOPATHY, AND ENTEROPATHY, X-LINKED syndrome; IPEX |

| 30,778 | GATAD2B | Histone modification read | 615,074 | AD | GAND SYNDROME; GAND |

| 4839 | HCFC1 | Chromatin remodeling | 309,541 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED 3; MRX3 |

| 14,063 | HDAC4 | Histone modification erase | 600,430 | AD | CHROMOSOME 2q37 DELETION SYNDROME. (Alternative name: BRACHYDACTYLY-MENTAL RETARDATION SYNDROME) |

| 13,315 | HDAC8 | Histone modification erase | 300,882 | XLD | CORNELIA DE LANGE SYNDROME 5; CDLS5 |

| 4861 | HELLS | Chromatin remodeling | 616,911 | AR | IMMUNODEFICIENCY-CENTROMERIC INSTABILITY-FACIAL ANOMALIES SYNDROME 4; ICF4 |

| 30,892 | HUWE1 | Histone modification write | 309,590 | XLD, XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC, TURNER TYPE; MRXST. (Alternative names: JUBERG–MARSIDI SYNDROME, BROOKS–WISNIEWSKI–BROWN SYNDROME) |

| 24,565 | KANSL1 | Histone modification write cofactor | 610,443 | AD | KOOLEN–DE VRIES SYNDROME; KDVS |

| 5275 | KAT5 | Histone modification write | 619,103 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH DYSMORPHIC FACIES, SLEEP DISTURBANCE, AND BRAIN ABNORMALITIES; NEDFASB |

| 13,013 | KAT6A | Histone modification write | 616,268 | AD | ARBOLEDA–THAM SYNDROME; ARTHS. (Alternative name: KAT6A SYNDROME) |

| 17,582 | KAT6B | Histone modification write | 603,736 | AD | SAY–BARBER–BIESECKER–YOUNG–SIMPSON SYNDROME; SBBYSS. (Alternative name: OHDO SYNDROME, SBBYS VARIANT) |

| 17,582 | KAT6B | Histone modification write | 606,170 | AD | GENITOPATELLAR SYNDROME; GTPTS |

| 17,933 | KAT8 | Histone modification write | 618,974 | AD | LI–GHORBANI–WEISZ–HUBSHMAN SYNDROME; LIGOWS |

| 29,079 | KDM1A | Histone modification erase | 616,728 | AD | CLEFT PALATE, PSYCHOMOTOR RETARDATION, AND DISTINCTIVE FACIAL FEATURES; CPRF |

| 1337 | KDM3B | Histone modification erase | 618,846 | AD | DIETS–JONGMANS SYNDROME; DIJOS |

| 29,136 | KDM4B | Histone modification erase | 619,320 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 65, MRD65 |

| 18,039 | KDM5B | Histone modification erase | 618,109 | AR | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE 65; MRT65 |

| 11,114 | KDM5C | Histone modification erase | 300,534 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC, CLAES-JENSEN TYPE; MRXSCJ |

| 12,637 | KDM6A | Histone modification erase | 300,867 | XLD | KABUKI SYNDROME 2; KABUK2 |

| 29,012 | KDM6B | Histone modification erase | 618,505 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH COARSE FACIES AND MILD DISTAL SKELETAL ABNORMALITIES; NEDCFSA |

| 7132 | KMT2A | Histone modification write | 605,130 | AD | WIEDEMANN–STEINER SYNDROME; WDSTS |

| 13,726 | KMT2C | Histone modification write | 617,768 | AD | KLEEFSTRA SYNDROME 2; KLEFS2 |

| 7133 | KMT2D | Histone modification write | 147,920 | AD | KABUKI SYNDROME 1; KABUK1 |

| 18,541 | KMT2E | Histone modification write | 618,512 | AD | O'DONNELL–LURIA–RODAN SYNDROME; ODLURO |

| 24,283 | KMT5B | Histone modification write | 617,788 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 51; MRD51 |

| 25,726 | LAS1L | Histone modification write cofactor | 309,585 | XLR | WILSON–TURNER X-LINKED MENTAL RETARDATION SYNDROME |

| 6518 | LBR | Anchors the lamina and the heterochromatin to the inner nuclear membrane | 613,471 | AD | REYNOLDS SYNDROME |

| 6859 | MAP3K7 | Histone modification write | 157,800 | AD | CARDIOSPONDYLOCARPOFACIAL SYNDROME; CSCF |

| 20,444 | MBD5 | Chromatin remodeling | 156,200 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 1; MRD1 |

| 6990 | MECP2 | Histone modification write cofactor, TF | 300,055 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC 13; MRXS13 |

| 6990 | MECP2 | Histone modification write cofactor, TF | 300,260 | XLR | LUBS X-LINKED MENTAL RETARDATION SYNDROME; MRXSL. (Alternative name: MECP2 DUPLICATION SYNDROME) |

| 6990 | MECP2 | Histone modification write cofactor, TF | 312,750 | XLD | RETT SYNDROME; RTT |

| 7010 | MEN1 | Histone modification write cofactor | 131,100 | AD | WERMER SYNDROME (Alternative name: MEN1 syndrome) |

| 7329 | MSH6 | Histone modification read | 619,097 | AR | MISMATCH REPAIR CANCER SYNDROME 3; MMRCS3 |

| 7370 | MSL3 | Histone modification read | 301,032 | XLD | BASILICATA–AKHTAR SYNDROME |

| 29,401 | MYSM1 | Histone modification erase | 618,116 | AR | BONE MARROW FAILURE SYNDROME 4; BMFS4 |

| 7652 | NBN | Chromatin remodeling | 251,260 | AR | NIJMEGEN BREAKAGE SYNDROME; NBS |

| 18,591 | NEK9 | Histone modification write | 617,022 | AR | LETHAL CONGENITAL CONTRACTURE SYNDROME 10; LCCS10 |

| 28,862 | NIPBL | Histone modification erase cofactor | 122,470 | AD | CORNELIA DE LANGE SYNDROME 1; CDLS1 |

| 14,234 | NSD1 | Histone modification write | 117,550 | AD | SOTOS SYNDROME 1 |

| 12,766 | NSD2 | Histone modification write | 194,190 | AD | WOLF–HIRSCHHORN SYNDROME; WHS |

| 8127 | OGT | Histone modification write | 300,997 | XLR | X-LINKED INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER 106; XLID106 |

| 18,337 | PADI3 | Histone modification | 191,480 | AR | UNCOMBABLE HAIR SYNDROME 1; UHS1 |

| 12,929 | PCGF2 | Polycomb group (PcG) protein | 618,371 | AD | TURNPENNY–FRY SYNDROME; TPFS |

| 8729 | PCNA | Chromatin remodeling | 615,919 | AR | ATAXIA-TELANGIECTASIA-LIKE DISORDER 2; ATLD2 |

| 24,156 | PHF21A | Histone modification erase cofactor | 618,725 | AD | INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH BEHAVIORAL ABNORMALITIES AND CRANIOFACIAL DYSMORPHISM WITH OR WITHOUT SEIZURES; IDDBCS |

| 20,672 | PHF8 | Histone modification erase | 300,263 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC, SIDERIUS TYPE; MRXSSD |

| 15,673 | PHIP | Histone modification read | 617,991 | AD | CHUNG–JANSEN SYNDROME; CHUJANS |

| 18,801 | POGZ | Histone modification read | 616,364 | AD | WHITE–SUTTON SYNDROME; WHSUS |

| 9299 | PPP2CA | Histone modification write | 618,354 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER AND LANGUAGE DELAY WITH OR WITHOUT STRUCTURAL BRAIN ABNORMALITIES; NEDLBA |

| 9386 | PRKAG2 | Histone modification write cofactor | 194,200 | AD | WOLFF–PARKINSON–WHITE SYNDROME |

| 9399 | PRKCD | Histone modification | 615,559 | AR | AUTOIMMUNE LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE SYNDROME, TYPE III; ALPS3 |

| 25,557 | PRMT7 | Histone modification write | 617,157 | AR | SHORT STATURE, BRACHYDACTYLY, IMPAIRED INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT, AND SEIZURES; SBIDDS |

| 9817 | RAD51 | Histone modification erase | 617,244 | AD | FANCONI ANEMIA, COMPLEMENTATION GROUP R; FANCR |

| 9831 | RAG1 | Histone modification write | 603,554 | AR | OMENN SYNDROME |

| 9832 | RAG2 | Histone modification read | 603,554 | AR | OMENN SYNDROME |

| 9834 | RAI1 | Chromatin remodeling | 182,290 | AD | SMITH–MAGENIS SYNDROME; SMS |

| 13,429 | RLIM | Histone modification erase cofactor | 300,978 | XLR | TONNE–KALSCHEUER SYNDROME; TOKAS |

| 26,661 | RNF168 | Histone modification write | 611,943 | AR | RIDDLE SYNDROME; RIDL |

| 10,061 | RNF2 | Histone modification write | 619,460 | AD | LUO–SCHOCH–YAMAMOTO SYNDROME; LUSYAM |

| 10,432 | RPS6KA3 | Histone modification write cofactor | 303,600 | XLD | COFFIN–LOWRY SYNDROME; CLS |

| 10,432 | RPS6KA3 | Histone modification write cofactor | 300,844 | XLD | X-LINKED INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER 19; XLID19 |

| 10,541 | SATB1 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 619,229 | AD | KOHLSCHUTTER–TONZ SYNDROME-LIKE; KTZSL |

| 10,541 | SATB1 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 619,228 | AD | DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY WITH DYSMORPHIC FACIES AND DENTAL ANOMALIES; DEFDA |

| 21,637 | SATB2 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 612,313 | AD | GLASS SYNDROME |

| 10,760 | SET | Histone modification | 618,106 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 58; MRD58 |

| 29,010 | SETD1A | Histone modification write | 618,832 | AD | EPILEPSY, EARLY-ONSET, WITH OR WITHOUT DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY; EPEDD |

| 29,010 | SETD1A | Histone modification write | 619,056 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH SPEECH IMPAIRMENT AND DYSMORPHIC FACIES; NEDSID |

| 29,187 | SETD1B | Histone modification write | 619,000 | AD | INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH SEIZURES AND LANGUAGE DELAY; IDDSELD |

| 18,420 | SETD2 | Histone modification write | 616,831 | AD | LUSCAN–LUMISH SYNDROME; LLS |

| 25,566 | SETD5 | Histone modification write | 615,761 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 23; MRD23 |

| 19,353 | SIN3A | Histone modification erase cofactor, TF | 613,406 | AD | WITTEVEEN–KOLK SYNDROME; WITKOS |

| 11,098 | SMARCA2 | Histone modification read, TF | 601,358 | AD | NICOLAIDES–BARAITSER SYNDROME; NCBRS |

| 11,098 | SMARCA2 | Histone modification read, TF | 619,293 | AD | BLEPHAROPHIMOSIS-IMPAIRED INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT SYNDROME; BIS |

| 11,100 | SMARCA4 | Histone modification read, TF | 613,325 | AD | RHABDOID TUMOR PREDISPOSITION SYNDROME 2; RTPS2 |

| 11,100 | SMARCA4 | Histone modification read, TF | 614,609 | AD | COFFIN-SIRIS SYNDROME 4; CSS4 |

| 18,398 | SMARCAD1 | Chromatin remodeling | 129,200 | AD | BASAN SYNDROME |

| 18,398 | SMARCAD1 | Chromatin remodeling | 181,600 | AD | HURIEZ SYNDROME; HRZ |

| 11,103 | SMARCB1 | Histone modification read | 609,322 | AD | RHABDOID TUMOR PREDISPOSITION SYNDROME 1; RTPS1 |

| 11,103 | SMARCB1 | Histone modification read | 614,608 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 3; CSS3 |

| 11,105 | SMARCC2 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 618,362 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 8; CSS8 |

| 11,106 | SMARCD1 | Chromatin remodeling | 618,779 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 11; CSS11 |

| 11,109 | SMARCE1 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor | 616,938 | AD | COFFIN–SIRIS SYNDROME 5; CSS5 |

| 11,094 | SNAI2 | Histone modification erase cofactor | 608,890 | AR | WAARDENBURG SYNDROME, TYPE 2D |

| 11,254 | SPOP | Histone modification write | 618,828 | AD | NABAIS SA–DE VRIES SYNDROME, TYPE 1; NSDVS1 |

| 11,254 | SPOP | Histone modification write | 618,829 | AD | NABAIS SA–DE VRIES SYNDROME, TYPE 2; NSDVS2 |

| 16,974 | SRCAP | Chromatin remodeling, Histone modification erase | 619,595 | AD | DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY, HYPOTONIA, MUSCULOSKELETAL DEFECTS, AND BEHAVIORAL ABNORMALITIES; DEHMBA |

| 16,974 | SRCAP | Chromatin remodeling, Histone modification erase | 136,140 | AD | FLOATING-HARBOR SYNDROME; FLHS |

| 11,465 | SUPT16H | Histone modification read | 619,480 | AD | NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER WITH DYSMORPHIC FACIES AND THIN CORPUS CALLOSUM; NEDDFAC |

| 17,101 | SUZ12 | Histone modification write cofactor, Polycomb group (PcG) protein, TF | 618,786 | AD | IMAGAWA–MATSUMOTO SYNDROME; IMMAS |

| 11,535 | TAF1 | Histone modification write | 300,966 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC 33; MRXS33 |

| 11,535 | TAF1 | Histone modification write | 314,250 | XLR | X-linked torsion dystonia-parkinsonism syndrome. (Alternative name: Lubag Syndrome) |

| 11,536 | TAF2 | Part of novel TFTC-HAT complex, TF | 615,599 | AR | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE 40; MRT40 |

| 11,540 | TAF6 | Histone chaperone | 617,126 | AR | ALAZAMI–YUAN SYNDROME; ALYUS |

| 29,529 | TBL1XR1 | Targets NCoR repressive complex to deacetylated histones | 602,342 | AD | PIERPONT SYNDROME; PRPTS |

| 29,529 | TBL1XR1 | Targets NCoR repressive complex to deacetylated histones | 616,944 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 41; MRD41 |

| 28,313 | TET3 | DNA modification | 618,798 | AD, AR | BECK–FAHRNER SYNDROME; BEFAHRS |

| 11,842 | TLK2 | Histone modification write | 618,050 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 57; MRD57 |

| 11,998 | TP53 | Histone modification write cofactor, TF | 151,623 | AD | LI–FRAUMENI SYNDROME; LFS |

| 11,998 | TP53 | Histone modification write cofactor, TF | 618,165 | AD | BONE MARROW FAILURE SYNDROME 5; BMFS5 |

| 12,347 | TRRAP | Histone modification write cofactor | 618,454 | AD | DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY WITH OR WITHOUT DYSMORPHIC FACIES AND AUTISM; DEDDFA |

| 12,472 | UBE2A | Histone modification write | 300,860 | XLR | MENTAL RETARDATION, X-LINKED, SYNDROMIC, NASCIMENTO TYPE; MRXSN |

| 12,630 | USP7 | Histone modification erase, DNA modification cofactor | 616,863 | AD | HAO–FOUNTAIN SYNDROME; HAFOUS |

| 12,679 | VDR | Chromatin remodeling cofactor, TF | 277,440 | AR | RICKETS–ALOPECIA SYNDROME |

| 12,718 | VRK1 | Histone modification write | 607,596 | AR | PONTOCEREBELLAR HYPOPLASIA, TYPE 1A; PCH1A |

| 17,327 | WAC | Histone modification write cofactor | 616,708 | AD | DESANTO–SHINAWI SYNDROME; DESSH |

| 12,856 | YY1 | Chromatin remodeling cofactor, TF | 617,557 | AD | GABRIELE–DE VRIES SYNDROME; GADEVS |

| 16,966 | ZMYND11 | Histone modification read | 616,083 | AD | MENTAL RETARDATION AUTOSOMAL DOMINANT 30; MRD30 |

| 13,128 | ZNF711 | Histone modification erase cofactor | 300,803 | XLR | X-LINKED INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER 97; XLID97 |

AD autosomal dominant, AR autosomal recessive, XLD X-linked dominant, XLR X-linked dominant, TF transcription factor

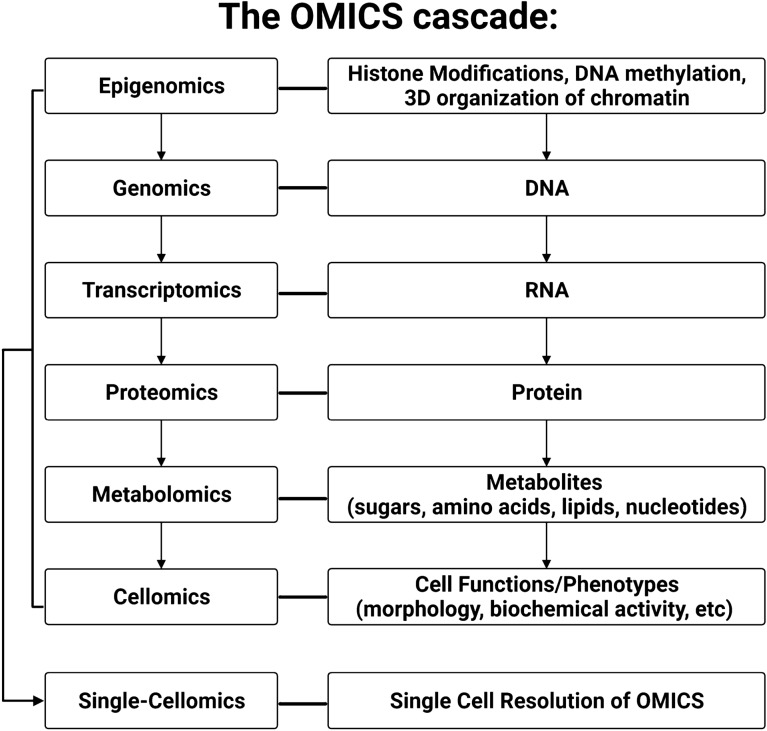

The OMICs cascade to study pathogenic mutations driving chromatinopathies

The suffix -OMICs is appended to a given field of biology to denote use of high-throughput and high-resolution technologies (Veenstra 2021). Genetic information flows through a 5-layer, hierarchical biological system where each OMICs layer can influence or be influenced by adjacent layers, and all layers can all be assessed at single-cell resolution, referred to here as the “OMICs cascade” (Dettmer et al. 2007) As shown in Fig. 2, each layer of the OMICs cascade highlights a unique biochemical snapshot of a biological system (e.g., cell, tissue, organ, or organism).

Fig. 2.

Graphical overview of the OMICs Cascade

The flow of biological information through the -OMICs cascade starts at the epigenome which controls specific activation of cellular programs through chemical modifications on nucleic acids and histones that drive transcription of DNA into RNA. The transcriptome is composed of all the RNA molecules in a cell that are either translated into protein by ribosomes or remain untranslated and function as non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs; e.g., microRNAs, small interfering RNAs, and long ncRNAs). These ncRNA indirectly or directly regulate the expression of their chosen targets through mechanisms such as altered transcript stability (Beermann et al. 2016; Roundtree et al. 2017). The proteome that is encoded by mRNA consists of all the proteins in a biological system (Wilkins 1994) and orchestrates an array of biological processes from cellular homeostasis via ion channels gradients to highly specialized tasks like cell-to-cell communication (Wilkins 2009). Finally, as we move beyond the central dogma of biology, we can assess the metabolome, which is defined as the low molecular weight molecules (i.e., metabolites) present in a biological system that participate in or are a product of biochemical reactions. Metabolites are required for a cell’s normal function, growth, and maintenance (Mosleth et al. 2020; Oliver et al. 1998). The integration of extrinsic stimuli with intrinsic cellular data culminates in cellular phenotypes, termed the cellome (Taylor 2007; Rosato et al. 2021) that are ever expanding with advancements in robotics and imaging capabilities.

The interconnected nature of each OMICs layer enables propagation of perturbations through a biological system. While essential biological processes have developed redundancies to buffer the impact of strong environmental insults, cellular responses are not adapted to respond to exceedingly rare, high effect genetic mutations. Therefore, these rare epigene mutations overwhelm a cell’s buffering capacity, resulting in clinically significant phenotypes or non-viability. Often, a single heterozygous mutation (i.e., one mutated allele and one normal allele) can disrupt multiple cell types and tissues by aberrant activation or repression of signaling pathways, resulting in congenital syndromes (Lin et al. 2022). For example, mutations in the epigene, CREBBP cause Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome 1 (RSTS1; MIM180849) and is a histone acetyltransferase. The -OMICs cascade can be assessed in samples harboring CREBBP mutations to assess the cascading effect of the genetic mutation on the epigenome as well as studies of the transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome. Together, these lead to an organismal phenotype seen in the RSTS1 patients and Crebbp knockout mouse models on learning and memory (Lipinski et al. 2022). Targeted studies highlight how aberrant histone acetylation can disrupt multiple layers of molecular and cellular phenotypes. To bridge this gap in knowledge, genome-wide studies of comprehensive OMICs cascade in human and model organisms harboring pathogenic epigene mutations are critical first steps. With multiple epigenes, cell types, and conditions, there are thousands of independent experiments needed to dissect out these complex interplay of the histone code.

Introduction to performing multi-omic studies on chromatinopathy-related specimens

The dissection of OMICs layers across multiple cell and tissue types can unravel molecular mechanisms driving clinical phenotypes in chromatinopathy patients. Epigenes function at the epigenomic layer at the top of the OMICs cascade. Therefore pathogenic germline mutations in epigenes result in a hierarchical cascading effect through four downstream OMICs layers. The coordinated biochemical disturbances across multiple OMICs layers provide clues about disease pathophysiology and can guide improved diagnostics and therapeutics for the disease. In the following section, we review key examples of the multiple experimental tools (Table 2) that can be used to assay each OMICs layer in chromatinopathies.

Table 2.

Summary of OMICs techniques

| OMICs layer | Molecular aspect assayed | Name of assay |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence |

Sanger Sequencing (Sanger et al. 1977) Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) (Lionel et al. 2018) Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) (Lee et al. 2014) Microarray-based Genotyping |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation | Methylation Microarrays(Chater-Diehl et al. 2021), Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) (Meissner et al. 2008), Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) (Olova et al. 2018), Methyl Cytosine sequencing (MethylC-seq) (Lister et al. 2008), Methyl DNA ImmunoPrecipitation analyzed by sequencing (MeDIP-seq) (Down et al. 2008), Methyl-CpG Binding Domain-isolated genomic DNA analyzed by sequencing (MBD-seq) (Serre et al. 2010) |

| Genomic coordinates of Histone Post-Translational Modifications or Chromatin-associated proteins | Chromatin ImmunoPrecipitation and Sequencing (ChIP-seq) (Johnson et al. 2007) | |

| Chromatin Accessibility | DNase-seq (Crawford et al. 2006), Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq) (Buenrostro et al. 2013), Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements and Sequencing (FAIRE-seq) (Giresi et al. 2007), MNase-seq (Chereji et al. 2019) | |

| Chromatin Conformation | Hi-C(Lieberman-Aiden et al. 2009) | |

| Chromatin Conformation specific for Chromatin-associated proteins | Chromatin Interaction Analysis with Paired-End-Tag sequencing (ChIA-PET) (Fullwood et al. 2009) | |

| Genomic coordinates of Histone Post-Translational Modifications or Chromatin-associated proteins | Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) (Skene and Henikoff 2017), Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) (Kaya-Okur et al. 2019) | |

| Transcriptomics | RNA sequence | Short-read RNA sequencing (Lowe et al. 2017), Pacbio's Long-read Isoform sequencing (ISO-seq) (Leung et al. 2021), Oxford Nanopore's Long-read Sequencing (Wang et al. 2021) |

| Proteomics | Proteins | Western Blots (Pillai-Kastoori et al. 2020), Flow cytometry(Bendall et al. 2012), Mass Spectrometry (MS) (Yates et al. 2009), Multiplexed ImmunoHistoChemistry (IHC) / ImmunoFluorescence (IF) (Tan et al. 2020), Protein Microarrays(Chandra et al. 2011), SOMAscan, a High-throughput proteomics platform(Kim et al. 2018), Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) (Weibrecht et al. 2010), Proximity Extension Assay (PEA) (Assarsson et al. 2014) |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites | Mass Spectrometry (MS) (Perez-Ramirez and Christofk 2021), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) (Perez-Ramirez and Christofk 2021), Biochemical assays(Perez-Ramirez and Christofk 2021), Image-based technologies (Perez-Ramirez and Christofk 2021), Cellomics Cellinsight High Content Screening Platform (Ardashov et al. 2019), Cellomics ArrayScan platform (Williams et al. 2006), Opera™ LX (PerkinElmer) automated confocal microscopy system (Rosato et al. 2021) |

Websites Accessed https://epifactors.autosome.org/, version 1.7.3

A successful multi-omics study design in human specimens can be achieved using multiple strategies and cell types. Assessing an epigene’s RNA and protein expression profile can identify which cell- or tissue-type(s) will yield the most meaningful results. In the context of Mendelian Syndromes, this type of multi-tissue sampling strategy can identify pathogenic mechanisms that remain constant across multiple cellular contexts (Lin et al. 2022; Götz et al. 2008). Furthermore, a multi-omics approach can identify which cells and tissues are particularly vulnerable or resilient to disruption of a specific epigene. In some cases, sampling of most appropriate cells or tissues is not possible, as there are ethical limitations or impossible to obtain. Therefore, in vitro modeling of specific cell types using stem cells is an attractive and highly relevant alternative approach. For chromatinopathy syndromes, many of the epigenes are highly expressed in early mammalian embryonic development (Nestorov et al. 2015), and functional studies in model organisms have shown that they are critically important in regulating stem cell pluripotency and differentiation (Katsumoto et al. 2006; Gan et al. 2007; Alari et al. 2018).

To assay the tissue-specific effects of pathogenic epigene mutations with the -omics techniques listed in Table 2, we can use human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) harboring patient-specific mutations or artificially created using gene editing. Since iPSCs have the potential to differentiate into all three germ layers (endoderm, ectoderm, and mesoderm) and all somatic cell types, they enable the in vitro recapitulation of early developmental in vivo events (Tiscornia et al. 2011; Loh et al. 2014, 2016; Tchieu et al. 2017; Durbin et al. 2018; Rowe and Daley 2019). iPSC models allow researchers to investigate disease-associated mechanisms in a temporal- and cell-type specific manner (Matheus et al. 2019; Carosso et al. 2019; Calzari et al. 2020). While iPSC-derived cells allow study of unobtainable cell types, it is known that stem cell studies suffer from problems with reproducibility that can be caused by: technical variability, genetic heterogeneity, and biological variation (Volpato and Webber 2020). However, the stem cell field is actively devising guidelines and testing methodologies to improve reproducibility as iPSCs are invaluable for in vitro disease modeling (Volpato et al. 2018; Anderson et al. 2021; Reed et al. 2021; Birbrair 2021; Brunner et al. 2022).

Performing these experiments across all epigenes, cell types and experimental conditions would cost billions of dollars and therefore creative methods for combining samples and decreasing sample requirements can improve our ability to comprehensively study the role of the epigenome in human disease. Despite the potential roadblocks to high-quality multi-omics studies, we believe assaying even a subset of cell types across the mutational spectrum will identify targetable and novel pathogenic mechanisms, potential disease-modifying gene networks, and diagnostic and monitoring biomarkers (Awamleh et al. 2022) for use in clinical trials.

For the following OMICs subsections, we first briefly introduce technologies that are commonly used to assay a given layer, we then highlight salient examples where these OMICs technologies were applied to chromatinopathy-related biological specimens such that novel disease-associated properties were identified. We highlight the fact that of the 179 chromatinopathies identified in this review (Table 1), only six chromatinopathies (i.e., Kabuki Syndrome 1 and 2, Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome 1 and 2, Rett Syndrome, and Bohring Opitz Syndrome) have been thoroughly studied using a multi-omics approach in disease-relevant cell types (Berdasco and Esteller 2013; Bjornsson 2015; Fallah et al. 2020; Fahrner and Bjornsson 2014; Faundes et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2022). There remains a huge potential for major discoveries in the chromatinopathy field that will lead to the development of novel therapeutics.

Epigenomics

Each aspect of the epigenome can be precisely measured using high-throughput techniques to understand how the epigenome changes across biological contexts (Mehrmohamadi et al. 2021). The most progress has been made in developing DNA methylation-based epi-signatures, which capture the DNA methylation changes caused by a pathogenic mutation that can then be used to distinguish genetic variants of uncertain significance as benign or pathogenic (Chater-Diehl et al. 2021; Awamleh et al. 2022). These tools can be used as a next-line test to end the diagnostic odyssey by classifying a variant as causal for the syndrome or as a benign variant. Another use of epigenetic biomarkers is for therapeutic monitoring to determine whether precision targeted treatments drugs can reverse the effect of pathogenic mutation on the DNA methylation episignature (Butcher et al. 2017; Awamleh et al. 2022). To generate DNA methylation episignatures, patient DNA undergoes bisulfite chemical conversion (Fig. 1) and then is profiled on a methylation array containing 850,000 CpG methylation sites or by sequencing (Pidsley et al. 2016). A recent paper demonstrated that ASXL1 mutations that cause Bohring–Opitz Syndrome (BOS) have a distinct methylation episignature from other chromatinopathy disorders, like Kabuki syndrome, Sotos syndrome, and Weaver syndrome (Awamleh et al. 2022). Specifically, 763 differentially methylated CpG sites in BOS patients were used to develop the episignature and these classified variants of unknown significance (VUS) in ASXL1 by combining machine learning with the BOS episignature—thereby expanding the diagnostic tools available for this chromatinopathy (Awamleh et al. 2022). In a separate study, researchers derived methylation signatures from patients with 50 different chromatinopathies and created a Methylation Variant Pathogenicity (MVP) score which quantifies the probability that a score matches a specific disease (Sadikovic et al. 2021). One major challenge in rare disease studies is the need for robust replication and reproducibility of biomarkers. The standard in the field is to provide the basic summary of which methylation sites were used to generate the episignatures (Choufani et al. 2020). However, availability of raw data would provide immense benefit to the rare disease community. To date, many studies fail to provide raw or summary data which prevent validation in other data sets and reproducibility (Levy et al. 2022).

Genomics

Pathogenic mutations in epigenes that occur in the germline leads to Chromatinopathies and mutations that arise in somatic cells lead to cancer development. (Berdasco and Esteller 2013; Fahrner and Bjornsson 2014; Bjornsson 2015; Wainwright and Scaffidi 2017; French and Pauklin 2021). Cataloging common mechanisms caused by epigene mutations across disease can point toward precision therapies for both types of disorders (Russell et al. 2015; Slatnick et al. 2023). Investigating the specific epigene mutations that cause existing chromatinopathies remains critical as mutations within several epigenes (e.g., CREBBP, EP300, KAT6B, DNMT3A) cause more than one developmental syndrome with no established mechanism for the distinct clinical presentations. For example, mutations predicted to cause premature truncation variants in KAT6B cause two recognized syndromes: Genitopatellar Syndrome (GPS) (Campeau et al. 2012) and Say–Barber–Biesecker–Young–Simpson Syndrome (SBBYSS) (Clayton-Smith et al. 2011). However, a recent study highlighted a significant overlap and presence of an intermediate clinical phenotype with features of both GPS or SBBYSS (Zhang et al. 2020) and that these differences may be due to the variable location of the pathogenic mutation within the gene body of KAT6B (Yabumoto et al. 2021). The paralog of KAT6B, which is KAT6A, causes a single chromatinopathy called Arboleda–Tham Syndrome (ARTHS) and patients display phenotypic variability that is correlated with location of the mutation within the gene body of KAT6A (Kennedy et al. 2018). Understanding how truncations affect gene and protein function can influence response to precision therapies, when they become available. A clear understanding how specific mutations drive different causal mechanisms and clinical phenotypes will be essential to determining whether therapies will be equally effective across all mutations observed in patients.

Transcriptomics

The ability to vary exon usage in a transcript exponentially increases the diversity of RNA isoforms possible within a cell and ultimately drives the protein diversity. Many genes expressing multiple isoforms per cell type (Djebali et al. 2012). Pathogenic epigene mutations can disrupt gene expression, splicing, alternative polyadenylation, and accessibility of transcriptional start sites which leads to disease phenotypes. RNA sequencing technologies (Bolisetty et al. 2015; Jeffries et al. 2020) allows study of isoforms-specific effects of epigene mutations that translate across cell and developmental time. These studies have the power to inform the effect of genomic variants that fall outside of the canonical protein-coding regions and affect splice isoforms.

Recently, the clinical utilities of transcriptome studies have been used to functionally validate rare pathogenic splice variants that disrupt genes causing rare Mendelian Disease (Cummings et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2020). Transcriptomic analysis can also reveal isoform-specific pathogenic mechanisms underlying chromatinopathy syndromes. In Rett syndrome, an X-linked chromatinopathy caused by heterozygous mutations in the gene MECP2, researchers discovered alternative splicing of the MECP2 transcript led to the production of a novel isoforms with different N-terminus relative to the canonical MECP2 transcript (Kriaucionis and Bird 2004; Mnatzakanian et al. 2004). Specifically, at the time, the canonical MECP2 transcript included exons 1 through 4 and translation of this isoform began at the “ATG” present in exon 2 (MECP2e2)—while the newly discovered MECP2 transcript excluded exon 2 via alternative splicing to generate a novel isoform whose translation begins at the “ATG” present in exon 1 (MECP2e1) (Kriaucionis and Bird 2004; Mnatzakanian et al. 2004). A subset of Rett syndrome patients had mutations affecting only MECP2e1—suggesting that the exon1 ATG isoform was the critical isoform leading to Rett Syndrome (Djuric et al. 2015). iPSCs carrying a MECP2e1-specific mutation (Djuric et al. 2015) caused reduced neuron soma size and altered synaptic activity compared to controls (Djuric et al. 2015). Exogenous expression of wild-type MECP2e1, but not wild-type MECP2e2, resulted in the phenotypic rescue of neuron cell-body size (Djuric et al. 2015).

Proteomics

The human proteome represents the functional biological machinery and is the primary target for disease-modifying therapies. Protein abundance is regulated by the rates of translation and degradation, and protein function and stability is mediated by post-translational modifications. Mutations in epigenes are most frequently considered to disrupt the ability to identify, add, or remove post-translational modifications from histone marks (Aebersold and Mann 2016; Li et al. 2021). The workhorse machine driving proteomics-based discovery is the mass spectrometer (MS) which leverages differences in peptide mass-to-charge ratios to identify thousands of proteins and hundreds of protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) in tandem (Witze et al. 2007; Bantscheff et al. 2012; Silva et al. 2013). In the context of human disease, MS-based techniques are mainly used to quantify relative or absolute differences in peptide abundance across affected and unaffected individuals to pinpoint disease-specific proteomic changes (Altelaar et al. 2013). Importantly, these disease-specific proteomic changes can be used as biomarkers in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of various human morbidities, ranging from genetic disorders to infectious diseases and cancers (Fleurbaaij et al. 2015; Diedrich and Dengjel 2017; Daniel and Turner 2018; Chapman and Thoren 2020; Pančík et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2022). Since the epigenome has been implicated in various human morbidities and histone PTMs play a pivotal role in modulating the epigenome (Figs. 1, 2), it is no surprise that histone PTMs are being profiled to understand disease pathophysiology (Thygesen et al. 2018; Cobos et al. 2019; Azevedo et al. 2022; Lempiäinen and Garcia 2023).

In the context of chromatinopathies, a majority of the proteomic data that exists from patient-derived biological specimens (i.e., plasma, fibroblasts, iPSC-derived lineages) pertains to Rett syndrome (Cortelazzo et al. 2013; Pecorelli et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2019; Varderidou-Minasian et al. 2020; Cicaloni et al. 2020b, a). In an unbiased proteomic approach using label-based MS, researchers found that neural lineages generated from Rett syndrome iPSCs showed aberrant protein expression in genes related to differentiation (Kim et al. 2019). In this time-course study, they performed MS on Rett syndrome and control iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neural cultures (Kim et al. 2019). Their proteomic analyses revealed NPCs derived from Rett syndrome patients displayed significantly reduced glial fate (GFAP +) and increased neuronal fate (MAP2 +) after three weeks of differentiation (Kim et al. 2019). Moreover, they found the suppression of glial fate in MECP2 mutant NPCs (i.e., those from Rett syndrome iPSCs) is due to overexpression of LIN28, a RNA binding protein that had been previously shown to blocks the differentiation into glia and increases differentiation into neurons (Balzer et al. 2010). The multi-faceted proteomics data suggest that Rett syndrome’s neuropathology is due to a cell-fate timing defect in early brain development. This study demonstrates proteomic approaches can uncover potential disease-causing mechanisms and underscores the importance of studying chromatinopathies in disease-relevant cell types at various points across developmental time.

Metabolomics

The metabolome is made up of low molecular weight metabolites, such as sugars, amino acids, lipids, and nucleotides (Dettmer et al. 2007), many of which are used in post-translational histone modifications that are important for writing the ‘histone code’ (Fig. 1) (Cheng and Kurdistani 2022; Hsieh et al. 2022). Metabolic phenotyping across samples with epigene mutations can identify novel biomarkers for disease (Remmel et al. 2016; Dettmer et al. 2007; Nicholson et al. 2012; Justice et al. 2013) due to the build-up of certain metabolic by products (Moser et al. 2007) and also serve as a marker as to whether a given treatment is having an effect. The metabolome of cells can be measured both quantitatively and qualitatively using various techniques that can be divided into four general categories: MS, nuclear magnetic resonance, biochemical assays/panels, and imaging-based analyses (Lu et al. 2017; Perez-Ramirez and Christofk 2021). However, the most common metabolomic approach is to assay metabolites in biological specimens using LC–MS/MS which couples liquid with dual mass spectrophotometry detectors for enhanced coverage of metabolites. As of 2022, ~ 253,000 metabolites and their reference spectra have been cataloged in The Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) which contains 61 different types of biological specimens (Wishart et al. 2022), understanding the cause-and-effect driving metabolic changes in patients with epigene mutations is vital to developing therapeutics for these disorders.

Most of the existing metabolomics data generated from chromatinopathy biological specimens relate to the study of Rett syndrome (Pecorelli et al. 2016; Cappuccio et al. 2019; Neul et al. 2020), Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome 1 and 2 (Welters et al. 2019), and Kabuki syndrome (Pacelli et al. 2020). The first publication to identify a metabolic defect in Rett syndrome found Rett syndrome patients had high lipid levels (i.e., total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol) (Sticozzi et al. 2013). In Rett syndrome fibroblasts, the hyperlipidemia is caused by altered PTM of SRB1, which encodes a receptor modulating cholesterol trafficking (Shen et al. 2018). A third independent study used MS to analyze over 900 plasma metabolites in Rett syndrome patients (Cappuccio et al. 2019). Pathway-based analysis for Rett syndrome dysregulated metabolites identified sphingolipid metabolism as a core pathway (Cappuccio et al. 2019). Taken together, these three independent metabolomic studies corroborated the hypothesis that lipid dysregulation is a key feature in Rett syndrome. These studies serve as a potential framework for other chromatinopathies that have metabolic disease-associated phenotypes.

Cellomics

The biological information from the upstream OMICs layers is integrated into a unique molecular state that produces a cellular phenotype, termed cellome. The cellome is traditionally assayed using high-content screens that capture cell properties, such as proliferation, size, migration (Matheus et al. 2019), morphology (Rosato et al. 2021), signaling (Gierisch et al. 2020), cell death, cell cycle, and organelle morphology (Iannetti et al. 2019) and density (Dawes et al. 2007; Taylor 2007). These dynamic cell properties are can be quantified using high-throughput fluorescent microscopy, flow cytometry, and plate readers and more automated systems quantifying specific phenotypes remain to be seen. Using functional assays and fluorescent microscopy, the following example identifies the aberrant cell phenotypes observed in lineages descending from BOS patient iPSCs, thereby expanding our understanding of BOS pathology (Matheus et al. 2019). In the case of rare chromatinopathies, it may not be possible to generate multiple patient iPSC lines. Therefore, genome editing of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) offers an alternative approach increasing the total number of independent biological replicates that can be used to study pathogenic mutations. Matheus et al. used iPSC lines derived from two BOS patients, in conjunction with four biologically-independent ASXL1 lines that were created via genome editing, to study dosage (heterozygous vs homozygous) and the effect of overexpression of the full-length and truncated mutant. They demonstrated that in all ASXL1 truncation paradigms, hPSC-derived neural crest (NC) cells showed significantly decreased migration in vitro and in vivo compared to controls (Matheus et al. 2019). Comparing the knockout and overexpression ASXL1 hPSC-derived NC models, demonstrated that full-length ASXL1 is required for normal NC migration and that the presence of any truncated ASXL1 protein is sufficient for perturbation of NC migration. Using disease-relevant cell types, this study identifies aberrant mechanisms that likely underlie the NC-related phenotypes observed in BOS.

Discussion

This review establishes a broader definition of chromatinopathy-causing epigenes and more than double the number of chromatinopathy syndromes previously reported in the literature (Table 1). The new list includes 720 epigenes with expanded definition of epigene functions. A total of 17 unique functions were described for proteins that directly alter the epigenome: (1) histone “writer”, (2) histone “eraser”, (3) histone “reader”, (4) chromatin “remodeler”, (5) histone chaperone, (6) scaffold protein, (7) DNA modifier, (8) RNA modifier, (9) polycomb group protein, (10) transcription factor, (11) protein cofactor for histone “writer”, (12) protein cofactor for histone “eraser”, (13) protein cofactor for histone “reader”, (14) protein cofactor for chromatin “remodeler”, (15) protein cofactor for histone chaperone, (16) protein cofactor for DNA modifier, and (17) protein cofactor for RNA modifier. Protein cofactors are essential for the optimal activity of complexes formed by epigenes that perform the associated epigenome-related function. A prime example of a protein cofactor is the chromatinopathy-causing epigene TRRAP, which is considered a histone “writer” cofactor because it binds to chromatin to recruit histone acetyltransferase complexes to a target sites (Murr et al. 2007; Cogné et al. 2019; Yin and Wang 2021). It is difficult to directly compare our approach to curation used by earlier publications describing chromatinopathy-causing genes due to insufficient description of their curation approach (Berdasco and Esteller 2013; Gabriele et al. 2018; Fahrner and Bjornsson 2019; Wilson et al. 2022; Nothof et al. 2022). Our list of chromatinopathy-causing epigenes (Table 1) creates a valuable resource for the scientific community.

Across the chromatinopathy genes, it is evident we have only scratched the surface of epigene mechanisms in human development and disease. Studies of rare chromatinopathies using patient- biospecimens will be essential to understanding how epigene mutations perturbs essential downstream pathways to cause disease. OMICs studies can link pathogenic mutations with specific biological perturbations and the emerging single-cell approaches will offer improved resolution of the biological changes within a disease state. For example, developing an integrated understanding of the multiple layers of the OMICs cascade can improve our identification of cell-, tissue- and developmentally specific markers. The novel information gained from multi-omic studies can be used to develop diagnostic biomarkers, to discover new chromatinopathies, to identify potential disease-modifying pathways, and pinpoint disease-causing mechanisms. There exist several reviews that cover the logistics of performing multi-omic studies and what computational tools are available for integration of data from multiple OMICs layers (Misra et al. 2018; Subramanian et al. 2020; Hill and Gerner 2021). Finally, to ensure reproducibility, it is imperative that researchers publish detailed information on experimental design, data analysis pipelines and raw data from their large-scale studies (Krassowski et al. 2020). Furthermore, national and global institutions have begun to address the lack of reproducibility by requiring that the raw data be easily accessible to prevent siloing of precious patient-data and fabrication of results. Chromatinopathy disorders are rare and every study, particularly those that use patient-derived samples, is a step toward identifying disease mechanisms and drug targets. With increased sharing of OMICs data derived from chromatinopathy patients, we can make true progress in the diagnosis and treatment of these rare disorders.

Author contributions

AAN and VAA conceptualized and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the following funding sources awarded to V.A.A.: NIH DP5OD024579, ASXL Research Related Endowment Pilot Grant (2020–2022), and the UCLA Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research Rose Hills Foundation Innovator Award 2022–2023. This work was supported by the following funding sources awarded to A.A.N.: the Broad Stem Cell Research Center Training Fellowship (2021–2022) and the Eugene V. Cota-Robles Fellowship (2019–2023).

Data Availability

All analyses from this study is available in the supplementary files or main text. We did not generate raw data for this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature. 2016;537:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature19949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alari V, Russo S, Terragni B, et al. iPSC-derived neurons of CREBBP- and EP300-mutated Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome patients show morphological alterations and hypoexcitability. Stem Cell Res. 2018;30:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altelaar AFM, Munoz J, Heck AJR. Next-generation proteomics: towards an integrative view of proteome dynamics. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:35–48. doi: 10.1038/nrg3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, et al. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D789–D798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NC, Chen P-F, Meganathan K, et al. Balancing serendipity and reproducibility: Pluripotent stem cells as experimental systems for intellectual and developmental disorders. Stem Cell Reports. 2021;16:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardashov OV, Pavlova AV, Mahato AK, et al. A novel small molecule supports the survival of cultured dopamine neurons and may restore the dopaminergic innervation of the brain in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10:4337–4349. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assarsson E, Lundberg M, Holmquist G, et al. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awamleh Z, Chater-Diehl E, Choufani S, et al. DNA methylation signature associated with Bohring-Opitz syndrome: a new tool for functional classification of variants in ASXL genes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41431-022-01083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo R, Jacquemin C, Villain N, et al. Mass spectrometry for neurobiomarker discovery: the relevance of post-translational modifications. Cells. 2022 doi: 10.3390/cells11081279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer E, Heine C, Jiang Q, et al. LIN28 alters cell fate succession and acts independently of the let-7 microRNA during neurogliogenesis in vitro. Development. 2010;137:891–900. doi: 10.1242/dev.042895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantscheff M, Lemeer S, Savitski MM, Kuster B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: critical review update from 2007 to the present. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:939–965. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beermann J, Piccoli M-T, Viereck J, Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in development and disease: background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:1297–1325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendall SC, Nolan GP, Roederer M, Chattopadhyay PK. A deep profiler’s guide to cytometry. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdasco M, Esteller M. Genetic syndromes caused by mutations in epigenetic genes. Hum Genet. 2013;132:359–383. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, editor. Current progress in iPSC disease modeling. San Diego: Academic Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson HT. The Mendelian disorders of the epigenetic machinery. Genome Res. 2015;25:1473–1481. doi: 10.1101/gr.190629.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolisetty MT, Rajadinakaran G, Graveley BR. Determining exon connectivity in complex mRNAs by nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. 2015;16:204. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0777-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boo SH, Kim YK. The emerging role of RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:400–408. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0407-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner JW, Lammertse HCA, van Berkel AA, et al. Power and optimal study design in iPSC-based brain disease modelling. Mol Psychiatry. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01866-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, et al. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher DT, Cytrynbaum C, Turinsky AL, et al. CHARGE and Kabuki syndromes: gene-specific DNA methylation signatures identify epigenetic mechanisms linking these clinically overlapping conditions. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:773–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzari L, Barcella M, Alari V, et al. Transcriptome analysis of iPSC-derived neurons from Rubinstein-Taybi patients reveals deficits in neuronal differentiation. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57:3685–3701. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01983-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau PM, Kim JC, Lu JT, et al. Mutations in KAT6B, encoding a histone acetyltransferase, cause Genitopatellar syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio G, Donti T, Pinelli M, et al. Sphingolipid metabolism perturbations in Rett syndrome. Metabolites. 2019 doi: 10.3390/metabo9100221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosso GA, Boukas L, Augustin JJ, et al. Precocious neuronal differentiation and disrupted oxygen responses in Kabuki syndrome. JCI Insight. 2019 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.129375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra H, Reddy PJ, Srivastava S. Protein microarrays and novel detection platforms. Expert Rev Proteom. 2011;8:61–79. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JR, Thoren KL. Tracking of low disease burden in multiple myeloma: using mass spectrometry assays in peripheral blood. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2020;33:101142. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2020.101142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater-Diehl E, Goodman SJ, Cytrynbaum C, et al. Anatomy of DNA methylation signatures: emerging insights and applications. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:1359–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Zhao BS, He C. Nucleic acid modifications in regulation of gene expression. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-Q, Zhao W-S, Luo G-Z. Mapping and editing of nucleic acid modifications. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Kurdistani SK. Chromatin as a metabolic organelle: Integrating the cellular flow of carbon with gene expression. Mol Cell. 2022;82:8–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chereji RV, Bryson TD, Henikoff S. Quantitative MNase-seq accurately maps nucleosome occupancy levels. Genome Biol. 2019;20:198. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1815-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitiashvili T, Dror I, Kim R, et al. Female human primordial germ cells display X-chromosome dosage compensation despite the absence of X-inactivation. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22:1436–1446. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-00607-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choufani S, Gibson WT, Turinsky AL, et al. DNA methylation signature for EZH2 functionally classifies sequence variants in three PRC2 complex genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;106:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicaloni V, Pecorelli A, Cordone V, et al. A proteomics approach to further highlight the altered inflammatory condition in Rett syndrome. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2020;696:108660. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2020.108660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicaloni V, Pecorelli A, Tinti L, et al. Proteomic profiling reveals mitochondrial alterations in Rett syndrome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;155:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton-Smith J, O’Sullivan J, Daly S, et al. Whole-exome-sequencing identifies mutations in histone acetyltransferase gene KAT6B in individuals with the Say-Barber-Biesecker variant of Ohdo syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos SN, Bennett SA, Torrente MP. The impact of histone post-translational modifications in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:1982–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogné B, Ehresmann S, Beauregard-Lacroix E, et al. Missense variants in the histone acetyltransferase complex component gene TRRAP cause autism and syndromic intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:530–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo A, Guerranti R, De Felice C, et al. A plasma proteomic approach in Rett syndrome: classical versus preserved speech variant. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:438653. doi: 10.1155/2013/438653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford GE, Holt IE, Whittle J, et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) Genome Res. 2006;16:123–131. doi: 10.1101/gr.4074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings BB, Marshall JL, Tukiainen T, et al. Improving genetic diagnosis in Mendelian disease with transcriptome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2017 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Y, Turner C. Newborn sickle cell disease screening using electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Screening. 2018;4:35. doi: 10.3390/ijns4040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes LJ, Angell H, Sleeman M, Sleeman JR. TGFβ isoform dependent Smad2/3 kinetics in human lens epithelial cells: a Cellomics analysis. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(5):1009–12. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans C, Maggert KA. What do you mean, “epigenetic”? Genetics. 2015;199:887–896. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.173492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer K, Aronov PA, Hammock BD. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26:51–78. doi: 10.1002/mas.20108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich B, Dengjel J. Insights into autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease by quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;369:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuric U, Cheung AYL, Zhang W, et al. MECP2e1 isoform mutation affects the form and function of neurons derived from Rett syndrome patient iPS cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;76:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Down TA, Rakyan VK, Turner DJ, et al. A Bayesian deconvolution strategy for immunoprecipitation-based DNA methylome analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:779–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin MD, Cadar AG, Chun YW, Hong CC. Investigating pediatric disorders with induced pluripotent stem cells. Pediatr Res. 2018;84:499–508. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM, Pandya-Jones A, McDonel P, et al. The Xist lncRNA exploits three-dimensional genome architecture to spread across the X chromosome. Science. 2013;341:1237973. doi: 10.1126/science.1237973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrner JA, Bjornsson HT. Mendelian disorders of the epigenetic machinery: tipping the balance of chromatin states. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2014;15:269–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090613-094245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrner JA, Bjornsson HT. Mendelian disorders of the epigenetic machinery: postnatal malleability and therapeutic prospects. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28:R254–R264. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallah MS, Szarics D, Robson CM, Eubanks JH. Impaired regulation of histone methylation and acetylation underlies specific neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Genet. 2020;11:613098. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.613098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faundes V, Newman WG, Bernardini L, et al. Histone lysine methylases and demethylases in the landscape of human developmental disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleurbaaij F, van Leeuwen HC, Klychnikov OI, et al. Mass spectrometry in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Chromatographia. 2015;78:379–389. doi: 10.1007/s10337-014-2839-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- French R, Pauklin S. Epigenetic regulation of cancer stem cell formation and maintenance. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:2884–2897. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullwood MJ, Liu MH, Pan YF, et al. An oestrogen-receptor-alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature. 2009;462:58–64. doi: 10.1038/nature08497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele M, Lopez Tobon A, D’Agostino G, Testa G. The chromatin basis of neurodevelopmental disorders: Rethinking dysfunction along the molecular and temporal axes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84:306–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Q, Yoshida T, McDonald OG, Owens GK. Concise review: epigenetic mechanisms contribute to pluripotency and cell lineage determination of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierisch ME, Giovannucci TA, Dantuma NP. Reporter-based screens for the ubiquitin/proteasome system. Front Chem. 2020;8:64. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giresi PG, Kim J, McDaniell RM, et al. FAIRE (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 2007;17:877–885. doi: 10.1101/gr.5533506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz A, Isohanni P, Pihko H, et al. Thymidine kinase 2 defects can cause multi-tissue mtDNA depletion syndrome. Brain. 2008;131:2841–2850. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, et al. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]