Abstract

Background

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) characterized by degeneration of knee cartilage and subsequent bone hyperplasia is a prevalent joint condition primarily affecting aging adults. The pathophysiology of KOA remains poorly understood, as it involves complex mechanisms that result in the same outcome. Consequently, researchers are interested in studying KOA and require appropriate animal models for basic research. Chinese herbal compounds, which consist of multiple herbs with diverse pharmacological properties, possess characteristics such as multicomponent, multipathway, and multitarget effects. The potential benefits in the treatment of KOA continue to attract attention.

Purpose

This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the advantages, limitations, and specific considerations in selecting different species and methods for KOA animal models. This will help researchers make informed decisions when choosing an animal model.

Methods

Online academic databases (e.g., PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and CNKI) were searched using the search terms “knee osteoarthritis,” “animal models,” “traditional Chinese medicine,” and their combinations, primarily including KOA studies published from 2010 to 2023.

Results

Based on literature retrieval, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the methods of establishing KOA animal models; introduces the current status of advantages and disadvantages of various animal models, including mice, rats, rabbits, dogs, and sheep/goats; and presents the current status of methods used to establish KOA animal models.

Conclusion

This study provides a review of the animal models used in recent KOA research, discusses the common modeling methods, and emphasizes the role of traditional Chinese medicine compounds in the treatment of KOA.

Keywords: animal models, knee osteoarthritis, system review, traditional Chinese medicine

Classification of knee osteoarthritis animal models based on etiology and the mechanism of action. Different methods of establishing knee osteoarthritis animal models have their own advantages and limitations, and researchers need to choose the right model according to their research purposes and problems.

1. INTRODUCTION

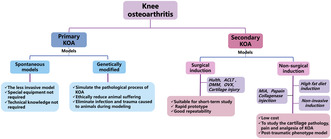

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), also known as degenerative arthritis, is a disease caused by degenerative pathological changes, including bone hyperplasia, synovial inflammatory lesions, cartilage degeneration, and sclerosis of the underlying bone. 1 China is accelerating into an aging society. As a common age‐related disease, KOA can lead to chronic knee pain, loss of motor function, and even disability in the elderly population. 2 A 4‐year follow‐up national population survey study showed that the cumulative incidence of symptomatic KOA over 4 years was 8.5% in Chinese adults aged ≥45 years. 3 KOA can greatly reduce the living quality of patients, 4 and the management cost of KOA is extremely high, resulting in a heavy burden on families and society. According to epidemiological surveys, 5 symptomatic KOA is widespread in China, with a higher prevalence in women than in men; the prevalence varies based on sociodemographic, economic, and geographic factors. At present, the causes of KOA, such as aging, obesity, osteoporosis, inflammation, genetics, and metabolic disorders, 4 , 6 are still unclear and are considered to affect the pathological factors of KOA (Figure 1). The main pathophysiological mechanisms of KOA include subchondral bone changes, osteophyte formation, degenerative meniscus, Baker's cyst, and contraction of inflammatory synovium, bursa, and tendon. 7 The imbalance of synthesis and degradation of chondrocytes, extracellular matrix (ECM), and subchondral bone eventually lead to KOA, but the specific pathogenesis has not been unified.

FIGURE 1.

The pathological factors of KOA (knee osteoarthritis).

Nonpharmacologic treatment options for patients with KOA include weight loss, exercise, and orthotics, whereas medical treatment includes oral pain management medications or intra‐articular injections. A range of surgical options are also available, including lower‐extremity reconstructive osteotomy, arthroscopy, and partial or total knee replacement. The clinical practice guidelines of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons conclude that exercise and physical therapy are effective ways to address pain and function in patients with KOA. 8 Dietary supplements, such as glucosamine, chondroitin, turmeric, ginger extract, and vitamin D, have long been considered as alternative medicines for the treatment of KOA symptoms. Data from studies have demonstrated that dietary supplement therapy significantly reduces pain and improves motor function in patients with KOA, with relatively minimal risk involved, but the major barrier is the high cost of treatment. 9 , 10 Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, aclofenac, celecoxib, 11 and acetaminophen have been widely used in the treatment of KOA. These drugs can relieve pain and improve joint function in patients with KOA. 12 Although effective, these drugs often cause drug‐related adverse effects. Intra‐articular injections are widely used in patients, and the most common injection methods are corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, and platelet‐rich plasma. However, the efficacy and safety of intra‐articular injection are still controversial. 13 Surgical treatment has restrictions on patients' age, gender, and underlying diseases. Total knee arthroplasty is an effective and cost‐effective treatment for severe KOA, 14 but its high risk of postoperative infection makes it unsuitable for young patients with active KOA. The long‐term effects of periknee osteotomies are uncertain, 15 and the relative risks and benefits should be fully considered in the treatment. Numerous potential treatment schemes provide clinicians with many options for treating patients with KOA, but these recommendations are limited in some fields due to low quality or insufficient evidence.

Limited by ethical examination, some programs for studying KOA cannot be implemented in clinical practice, whereas experimental research based on animal models can further study its pathogenesis and treatment methods. In recent years, various KOA animal models have been widely used to study disease pathways and preclinical testing of new therapies. It is clear that animal models are an important tool to study the development of KOA. The transferability of the results for each model to human clinical conditions is different. 16 In recent years, many models have been developed and widely reported to study various characteristics of KOA. Traditional Chinese medicines (TCM), including acupuncture, moxibustion, herbal medicine, and massage, have been used in China for thousands of years to treat many diseases. These methods have been practiced worldwide, mainly as adjunctive treatments for chronic pain and diseases. 17 TCM is a common complementary therapy for KOA. Previous studies have shown that TCM is an effective treatment for relieving pain and swelling and improving knee joint function in patients with KOA. 18 Among them, the intervention treatment for KOA using Chinese medicine compounds has achieved good results. The mechanism of treating KOA with TCM is very complex, which involves promoting the differentiation of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells into chondrocytes, regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis, and downregulating the inflammatory reaction of knee joint caused by inflammatory factors such as interleukin (IL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). 19 In recent years, much progress has been made in the use of TCM compounds applied to the KOA model to treat KOA. 20 Several promising ingredients and herbal formulations have been identified to delay the progression of KOA, promote cartilage repair, and improve knee disease.

This article reviewed the animal models used in the study of KOA in recent years and summarized the use of TCM compounds in the developed KOA model, to aid in KOA research, help scholars make the best model selection, and obtain the best‐expected results in KOA research.

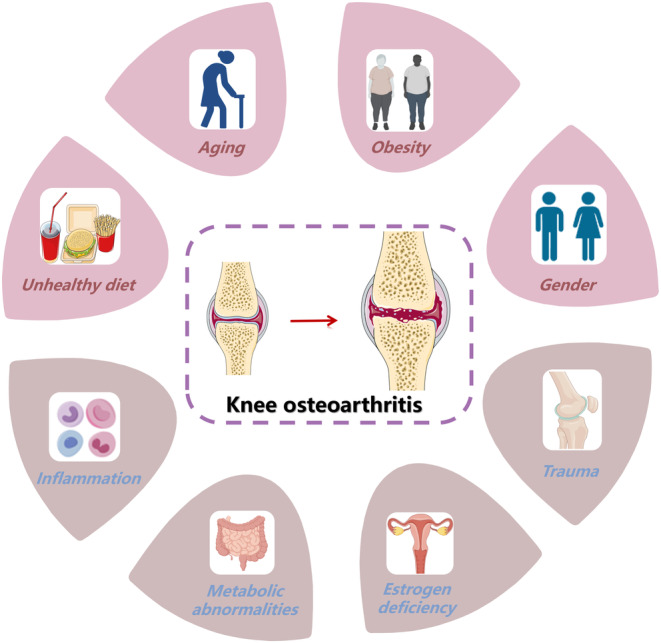

2. CLASSIFICATION OF KOA EXPERIMENTAL ANIMALS

The selection of experimental animals is a primary concern for researchers before conducting research on KOA. Choosing the right animal model for KOA is the first step to successful experiments. At present, many experimental animals such as rodents, primates, canids, and rabbits, are used in the study of KOA (Figure 2). To select the suitable animal for KOA experiments, researchers should consider the aim of the research, experimental protocol, ethical regulations, feeding difficulty, and other issues.

FIGURE 2.

Classification of KOA (knee osteoarthritis) experimental animals.

2.1. Rodent models

Rodents are currently most commonly used as KOA models, which are often used for drug screening and research on the pathological mechanisms of KOA, 21 Mice, especially STR/ort and C57BL/6, are the commonly used KOA mouse models. The anatomical structure and biomechanics of the knee joint of mice are similar to those of humans, but the cartilage of mice is relatively thin, ~0.03 mm, which is 1/70th that of humans. 21 , 22 Wang et al. 23 performed aseptic surgical resection of the medial meniscus of the left knee for 12‐week‐old male C57LB/6 mice to construct an animal model of KOA and found that irisin inhibited inflammatory‐mediated oxidative stress and insufficient ECM production by preserving mitochondrial biogenesis, kinetics, and autophagy, playing a therapeutic role in the development of KOA. Three weeks is the minimum age recommended for various experimental studies in rats. 24 And the older the rats, the more severe the KOA after modeling. The average cartilage thickness of rats is 0.1 mm, about thrice that of mice, and they also have a larger joint cavity, making them more commonly used for surgical or chemical‐induced KOA models. In addition, due to their thick cartilage layer, it is convenient to induce partial‐ and full‐layer cartilage defects in the KOA model, which can be used for artificial cartilage implantation, growth factors, and nerve‐related research. 24 , 25 Lv et al. 26 selected 8‐week‐old male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats as KOA animal models and established the KOA rat model by excising the medial meniscus and transecting the anterior meniscus to study the specific molecular mechanism of quercetin in the treatment of KOA.

The advantages of rodent models include easy access, low cost, and minimal breeding difficulty. 22 Nevertheless, the use of rodent models has its own limitations, such as age and sex differences and gait differences between rodents and humans. Relatively, rats do not have spontaneous osteoarthritis (OA), so they are not an ideal choice for studying spontaneous KOA. 25 The main disadvantages of these models are that the knee joint is small, resulting in a small amount of tissue available for research.

2.2. Rabbit models

Rabbits are gentle and easy to raise, with a larger knee joint cavity and thicker cartilage (0.2–0.7 mm), 21 making it easier for rabbits to undergo surgical modeling and obtain specimens. 27 Rebai et al. 28 selected female New Zealand rabbits and injected 0.2 mL of MIA solution under the patella of the left knee joint to induce OA, so as to simulate several aspects of human pathology, emphasizing the advantages of the monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)–induced arthritis model. Huang et al. 29 selected mature female New Zealand white rabbits for unilateral knee anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT) surgery to study the changes in subchondral bone and articular cartilage in rabbits with knee arthritis at 2 weeks (early OA) and 8 weeks (late OA) after ACLT.

The selection of rabbits also has certain disadvantages, as the biomechanics of the rabbit knee joint is completely different from that of humans. 30 First, the flexion angle of the rabbit knee joint is much higher than that of humans. Second, the lateral space of the rabbit knee joint has a greater load‐bearing capacity rather than the medial joint space. 31 , 32 Third, the chondrocytes and meniscus cells of rabbits are more numerous and dense, and have stronger self‐healing ability compared to humans. 33

2.3. Canine models

The knee joint structure of a dog is similar to that of humans, except for a sesamoid bone and extensor tendon. The larger body size of dogs makes their joint cavities larger and joint cartilage thicker (0.6–1.3 mm), 21 and is suitable for splint, bandage interventions, arthroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination. Therefore, the dog is currently the closest animal model to the gold standard. 22 , 34 Korchi et al. 35 induced KOA by transecting the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) of the right knee of dogs. Conventional MRI, enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, quantitative digital subtraction angiography, and dynamic‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the emergence of KOA after ACL injury was accompanied by synovial inflammation and vascular hyperplasia in canine models. This model is suitable for studying the development of angiogenesis in KOA. Kim et al. 36 used 60 beagles to induce OA via ACLT surgical manipulation; this study is the first to demonstrate that intra‐articular injection of human synovium‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells (hSD‐MSCs) can improve OA progression in dogs by repairing cartilage, promoting ECM synthesis, and inhibiting inflammatory response.

The knee joint cavity of dogs is larger, and the joint cartilage is thicker, which is similar to the anatomical structure of humans. The congenital advantage of canine models makes it easy to perform imaging examinations and arthroscopic interventions, and collect synovial fluid. The main disadvantages of canine models are high cost, difficulty in handling interventions, longer maturation time, and slower disease progression.

2.4. Sheep/goat models

Because sheep/goats have low feeding costs (compared to other large animals) and highly similar joint anatomical structures to humans, they are commonly used as surgical models. 31 Veronesi et al. 37 selected 12 female Bergamasca‐Masseses sheep to perform bilateral meniscectomy and treated the in vivo model of early OA in sheep using three different cell therapies cul‐expanded adipose‐derived stem cells (ADSCs), stromal vascular fraction (SVF), and cul‐expanded amniotic epithelial stem cells (AECs). All treatments improved the macroscopic appearance of the cartilage surface and reduced pro‐inflammatory cytokines in the synovial fluid. Of the three treatments, SVF was the best, whereas ADSC was the worst.

Moreover, the meniscus of sheep is larger, making it particularly suitable for studying meniscus degeneration. However, it is worth noting that the specificity of the digestive system in ruminants may have an impact on drug experiments. 38

2.5. Nonhuman primates

The knee joint of primates such as short‐tailed monkeys, macaques, and baboons is highly similar to that of humans, and their genome is highly similar to that of humans. The physiological structure and pathological changes in the knee joint are most similar to those of humans, 39 and it is relatively easy to develop a model. Housman et al. 40 collected the trabecular bone and cartilage from the medial condyle of femur of adult female baboon, scored the OA severity of each specimen, and used 450,000 array to measure the whole genome DNA methylation of baboon tissue to explore the relationship between methylation and OA in baboon. Spontaneous OA in rhesus monkeys is similar to that in humans, maintaining an upright body posture and exhibiting bone biomechanical properties very similar to humans. Yan et al. 41 used this model to study the relationship between OA and intestinal microbiota, and found that the diversity and composition of intestinal microbiota in OA monkeys were different from those in normal monkeys, suggesting that microorganisms may be biomarkers for the diagnosis of OA.

Nonhuman primates are closely related to humans, but they are rarely used at present due to high feeding cost, long observation period, and constraints of sources and ethics.

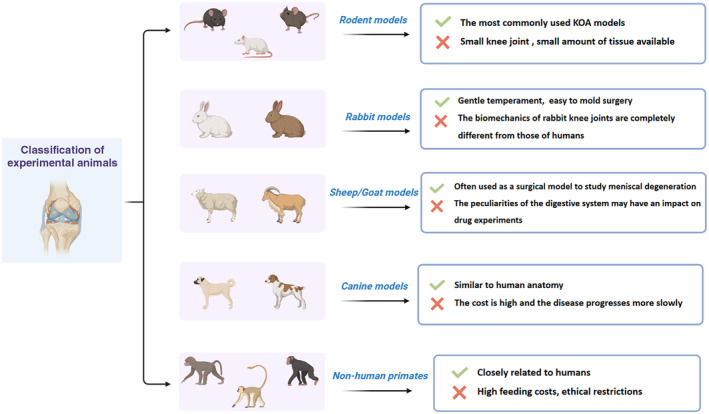

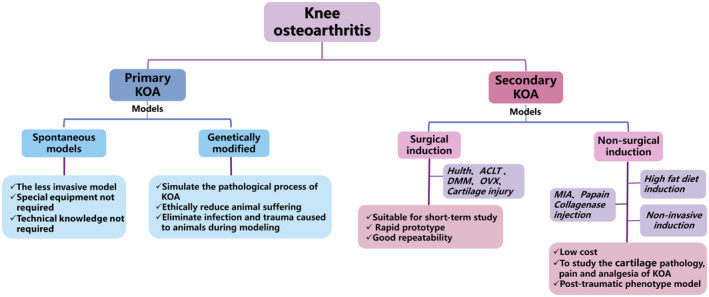

3. METHODS OF ESTABLISHING KOA ANIMAL MODELS

This part mainly discusses various methods of establishing animal models utilized in KOA research. The discussion revolves around the different approaches that researchers have taken to replicate specific aspects of knee joint pathology to gain a deeper understanding of the disease mechanisms in KOA. Different methods of establishing KOA animal models have their own advantages and limitations (Figure 3), and researchers need to choose the right model based on their research purposes and problems.

FIGURE 3.

Classification of KOA (knee osteoarthritis) animal modeling methods.

3.1. Spontaneous models

The spontaneous models refer to the KOA spontaneously induced in experimental animals without any conscious manual intervention. These models are useful because the similarity between the model and KOA in humans enables researchers to observe and study a pathological change progression of KOA. Also, it is relatively easy to implement as no specialized equipment is needed, nor is there a need for a surgeon with technical expertise. 42

Adipose‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells (adMSCs) have immune modulation, anti‐inflammation, and angiogenesis properties. 43 Afzali et al. 44 used the Hartley guinea pig model of spontaneous OA to evaluate the effects of systemic intravenous (IV) injection of adMSCs on OA animal models. The results showed that the gait parameters of guinea pigs significantly improved and the secretion of proinflammatory mediators in the whole body and joints reduced. A study used an Str/ort mouse model of spontaneous OA and a posttraumatic model to investigate pathological changes in the knee meniscus and ligaments during disease progression. The study found abnormal patterns of chondrogenesis, ossification, cell hypertrophy, meniscal erosion, and loss of fiber alignment in ligaments in both models. 45 Although researchers can test various therapeutic methods in animal models of spontaneous KOA, the long production cycle, the ethical implications of using nonhuman primates such as baboons and rhesus macaque, and the high cost of care are the reasons for the limited application of such models. 46

3.2. Secondary models

The secondary models can be caused by physical or chemical pathogenic factors to induce certain damage to animal tissues, organs, or the whole body, and some symptoms similar to those of human diseases. The physically induced model produces KOA by causing instability during surgery, such as ACLT and meniscectomy. 47 , 48 Chemically induced KOA is caused by injecting chemical drugs, such as MIA, papain, and collagenase, to alter homeostasis and destroy joint structure. 49 , 50 , 51 In addition to the aforementioned methods, there are many other methods to induce the KOA model, such as freezing and fat induction. Because of its high efficiency, stability, and repeatability, the induced KOA animal model is mainly used to study the treatment of drugs and pathogenesis of KOA.

3.2.1. Surgical induction

Hulth method

Hulth method is the classic method of KOA surgical modeling. The traditional Hulth method through the removal of experimental animals around the knee joint cross toughening zone and medial collateral ligament and the medial meniscus, experimental animals caused by joint instability, articular cartilage surface friction increases, cartilage wear increasingly forming a KOA. However, due to the trauma of this method, experimental animals are often affected by postoperative infection, and the inflammatory factors produced will interfere with the results of the research experiment. Therefore, in recent years, most researchers have used the modified Hulth methods to build the KOA model. 52 , 53

The modified Hulth method is based on excising the anterior cruciate ligament and then the medial collateral ligament or the inner/lateral meniscus, which have the characteristics of relatively less trauma, good stability, and good repeatability. Li et al. 54 used the modified Hulth method to expose the right‐knee cavity of SD rats for medial parapatellar incision. The study severed the medial collateral and anterior cruciate ligaments in the model rats and then excised the medial meniscus. Finally, the incisions were sutured in layers. After 12 weeks of modeling, pathological section staining showed attenuation of the hyaline cartilage layer, rough surface of cartilage, and sparse arrangement of bone trabeculae. Scanning electron microscopic image showed surface degeneration of cartilage. Wei et al. 55 selected New Zealand white rabbits as experimental subjects, made a medial parapatellar incision, exposed the knee joint, and transected the anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus to establish the right KOA model. Four weeks after surgery, one rabbit in the KOA group was randomly selected to anatomize the right‐knee joint; partial articular cartilage defects, incomplete surface, and hyperemia of synovial tissue were observed visually, indicating that the rabbit KOA model was successfully established. One study has shown that the intensity of autophagy changes as KOA severity progresses. 56 In this study, the Hulth‐modified method was used to establish the KOA model by stripping the medial collateral ligament of male SD rats to dislocate the patella valgus, bending the knee joint to cut the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, and dislocating the knee joint to remove the medial meniscus.

ACLT method

The ACLT method, which is one of the commonly used modeling methods for studying KOA, is developed by changing the stability of the knee joint and accelerating cartilage wear. ACLT changes were identical to human KOA histological findings, such as cartilage damage, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. 57 The principle of modeling is the same as the Hulth method; it induces less damage to the knee joint structure, and the knee joint is relatively stable after operation.

The ACL is an important structure to maintain the stability of the knee joint. 58 Its main role is to prevent the tibia from moving forward when bending the knee, prevent the knee from hyperextension when stretching the knee, and help control the rotation of the knee joint. It has been reported that ACL injury significantly increases the prevalence of KOA in patients. 59 The involvement of NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of OA is closely related to ACLT. Sun et al. 60 established an animal model of C57BL/6 mouse OA using ACLT, and adeno‐associated virus (AAV)–expressing Never in mitosis gene A (NIMA)–related kinase 7 (NEK7)–specific shRNA was injected into the knee joint of mice. It was found that NEK7 was highly expressed in the joint tissues of ACLT mice. Co‐inmunoprecipitation analysis showed that NEK7 and NLRP3 interacted in the knee tissues of ACLT mice, and NEK7 shRNA delivered by AAV inhibited the levels of TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐1β, and IL‐18. It also increased the level of IL‐10, suggesting that downregulation of NEK7 may play an anti‐OA role by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Yang et al. 61 used ACLT surgery to simulate the clinical characteristics of KOA, anesthetized male SD rats, and performed arthrotomy to expose the right‐knee joint and excise the ACL. Six weeks after ACLT, right‐knee samples of SD rats were subjected to immunohistochemistry staining. The results showed that the synthesis of IL‐1β and TNF‐α, key pro‐inflammatory factors related to the progression of KOA, in cartilage and synovium of the ACLT group was significantly increased. Similarly, rat KOA models were induced by ACLT surgery, and the rats showed mild cartilage destruction 4 weeks after surgery. In addition, the pathogenesis of KOA induced by ACLT surgery mainly focuses on the mechanical stress of articular cartilage overload and inflammation of synovium. 62 Qian et al. 63 established a moderate mouse KOA model using ACLT, and hematoxylin–eosin (HE) and safranin‐O (S‐O) staining were used to detect pathological changes in knee cartilage at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after surgery. It was found that the characteristics of cartilage degeneration in mice were time dependent and the expression of inflammatory factors was high, which were basically consistent with the degree of KOA, ensuring the success of the model.

Meniscectomy

The occurrence of KOA involves not only joint instability but also meniscus dysfunction. Meniscectomy results in pathological manifestations of KOA by disrupting the joint structure and causing stress imbalance. The meniscus acts as a joint filler, alleviating the friction of the femur and tibia, cushioning the impact of the joint capsule and synovium, and enhancing the stability of the joint in all directions. Once meniscus function is impaired, the meniscus cannot provide articular cartilage protection, which increases the risk and incidence of joint degeneration.

Meniscectomy interferes minimally with the intra‐articular environment and stable modeling, and can reflect the characteristics of early OA. This modeling approach is often used in studies to demonstrate the role of different kinases and transcription factors in cartilage degradation, to evaluate KOA‐related pain mechanisms, and to test drug interventions for KOA pain. 64 , 65 Wakayama et al. 66 made a small (3–5 mm) medial parapatellar skin incision on the right hind limb of 8‐week‐old female C57BL/6 mice, incised the joint capsule on the medial side of the patellar tendon, and transected the medial meniscotibial ligament to induce unilateral KOA by destabilization medial meniscus (DMM). The histological analysis of the knee at 12 weeks after the operation showed that the DMM‐induced articular cartilage destruction was serious, and the microcomputed tomography evaluation revealed that subchondral osteosclerosis mainly occurred on the medial tibial plateau. Inflammation promotes the development of OA with clinical features such as effusion or synovitis due to thickening of the synovium. 67 TNF‐α is a key inflammatory cytokine associated with cartilage degeneration in OA. 68 The medial tibial meniscus ligament was excised in 3‐month‐old male C57BL/6J skeletal mature mice to establish an unstable medial meniscus model. It has been found that low‐frequency vibration promotes the production of TNF‐α and thus increases cartilage degeneration in KOA. 69 Kaneko et al. 70 used meniscectomy to construct a rat model of KOA and demonstrated that oral administration of N‐acetylcysteine slowed the development of KOA in the rat model. In this study, the model was constructed using a parapatellar approach to reach the intra‐articular space of the knee through a median incision above the patella. Histological and pathological evaluation of bilateral knee joints of rats showed decreased S‐O staining and increased Mankin score, indicating the development of KOA.

Cartilage injury method

The whole process of knee degenerative changes after articular cartilage injury can be directly observed by using cartilage injury modeling in experimental animals. It is a relatively simple operation and a minimal damage modeling method in surgical induction. Articular cartilage is susceptible to injury by trauma, repeated shear, and torsion acting on joint surfaces. Although most of these lesions are asymptomatic, knee cartilage defects still represent a large source of pain and disability. 71 Tawonsawatruk et al. 72 compared the ACLT and cartilage injury induction models. The study found that pain patterns were different in the ACLT and cartilage injury models, where pain had subsided by 3 weeks after surgery, whereas in the ACLT model, pain persisted throughout the study period. Histological analysis showed that the ACLT model produced more significant changes in KOA than the cartilage injury model. These findings may reflect differences in clinical presentation after knee injury, so the selection of an appropriate KOA model in preclinical studies should be specific and relevant to clinical scenarios.

Ovariectomy

Ovariectomy (OVX) is the only surgical induction method that does not involve modeling the knee itself. Estrogen receptors are associated with the risk of developing KOA. 73 There is a considerable relationship between cartilage degeneration and OVX in mature animals. 74 By removing ovaries of experimental animals, the production and metabolism of estrogen and its analogues can act on articular cartilage or subchondral bone and directly induce chondrocyte apoptosis. KOA is most likely to occur in postmenopausal women or older adults with osteoporosis. 75 The rat is the most commonly used animal model, and its simulated objects are mainly postmenopausal women, menopausal women, or the elderly with osteoporosis, which can be used as a special model for relevant research. It can also be used to study the mechanism of estrogen action and its analogues on knee cartilage. Fontinele et al. 76 divided 6‐month‐old female Wistar rats into a control group without oophorectomy and exercise, a sedentary group with bilateral oophorectomy and no exercise, and a training group with bilateral oophorectomy and exercise. All the rats were euthanized at age 9 months. Morphological and stereological assessments were performed using histological sections stained with H&E and Sirius. It was found that the decrease in estrogen level caused important changes in the tibial cartilage of Wistar rats, the thickness of the surface part of the cartilage increased, and the nuclear volume of the superficial chondrocytes of the articular cartilage decreased. However, there is some debate on the effectiveness of this modeling method. The difficulty in operation and the strict requirements of experimental conditions are the disadvantages of OVX induction.

3.2.2. Nonsurgical induction

Iodoacetate‐induced model

Inducing the KOA model by drug injection is often used to study cartilage pathology, pain, and the analgesic effect of KOA. 77 , 78 , 79 Iodoacetate is a metabolic inhibitor, which can inhibit glycolysis, disrupt the cellular aerobic glycolysis pathway, and lead to a decrease in the quantity and quality of ECM proteoglycan synthesis, leading to chondrocyte apoptosis. Ikeda et al. 80 selected 6‐week‐old male SD rats. Rats in the MIA group were injected intra‐articularly with a single dose of 3 mg of MIA in 50 mL of physiological saline through the infrapatellar ligament using a 27‐gauge needle to establish a rat KOA model. Piezoelectric mRNA levels were measured in the knee joint and dorsal root ganglion and were not upregulated. Spassim et al. 81 divided 40 Wistar rats into four groups: G1: no joint disease, no treatment; G2: MIA‐induced joint disease, no treatment; G3: MIA‐induced joint lesions, treated with 5‐μg/mL intra‐articular ozone; and G4: MIA‐induced joint lesions, treated with 10‐μg/mL intra‐articular ozone; the experiment lasted for 60 days, the rats were euthanized, the volume density of the tibial and femur joints was measured, and histophysiological analysis was performed. The results showed that MIA can cause degeneration of articular cartilage and chondrocyte death. Yamada et al. 82 showed that injection of 1.5 mg of MIA into the knee joint of rats induced an inflammatory process manifested by pain, edema, increased neutrophil count, and joint damage. The level of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the knee joint, spinal cord, and brain stem of rats decreased significantly, whereas MDA was increased in the focal and distant sites of oxidative stress. It can be seen that an appropriate dose of MIA can effectively simulate the symptom features of early OA. The merits of the KOA model induced by MIA are low cost, speed, and reproducibility. Although this model notably avoids delicate and risky surgical operations, 28 it is difficult to control the progression of joint damage.

Collagenase induction model

Another frequently used enzyme‐based model for drug injection is the collagenase‐induced KOA model, where high‐purity collagenase is injected intra‐articularly and affects joint ligaments, resulting in joint instability. Pishgahi et al. 83 injected collagenase into the joint cavity of male New Zealand white rabbits to induce KOA and injected autologous conditioned serum (ACS) into KOA rabbits to evaluate its function. It was found that ACS improved the function and activity of KOA rabbits, and shortened the recovery time. Yu et al. 84 injected 25 μL of 500 U type II collagenase dissolved in normal saline into the right‐knee cavity of rats using a microsyringe, micro computed tomography (micro‐CT) was used to evaluate knee joint injury at weeks 3 and 6 after injection of type II collagenase. The results showed that cartilage damage began to appear in the knee structure of rats in the third week, and obvious synovial hyperplasia and osteophyte formation were observed in the sixth week, suggesting that a better KOA model could be established after the sixth week of knee joint induced by type II collagenase.

Papain induction model

Papain is a proteolytic enzyme that degrades proteoglycans in cartilage, thereby releasing chondroitin sulfate from the matrix. The papain‐induced KOA model was constructed by injecting 0.15 mL of mixed solution (2% papain: 0.03 mol/L l‐cysteine = 2:1) into the right‐knee cavity using 1 mL syringes and repeated injection 4 and 7 days later. H&E staining results showed that the chondrocytes were disordered, the cytoplasm was swollen, and the number of chondrocytes was significantly reduced for the model group. Mankin score was significantly increased compared to the control group, suggesting that the early KOA model was successfully established. 85 Such models induced by drug injection are suitable for short‐term studies to observe the pathological changes in the end stage of KOA cartilage. They are not suitable for the study of early‐stage pathogenesis and have destructive effects, nor do they mimic the natural pathogenesis.

High‐fat‐diet induction

Obesity is a risk factor for the occurrence and development of KOA, so the relationship between obesity and KOA can be further studied by establishing an obesity model through high‐fat‐diet (HFD) feeding and other methods. Obese patients have high knee load, and weight control can reduce the incidence of KOA. Endisha et al. 86 found that the plasma level of miR‐34a‐5p in an obese mouse model induced by HFD for 19 weeks was significantly higher than that of lean‐meat‐diet mice during the same period, and the expression of miR‐34a‐5p in mouse cartilage and synovial membrane was significantly increased. C57BL/6J male mice aged 9 weeks were fed either a HFD or a lean diet (LD) until 18 weeks, and the results showed that HFD‐fed mice showed increased body weight, body area, body fat percentage, bone mineral content, fasting glucose levels, and insulin levels at 18 weeks compared to LD‐fed mice. 87 Excessive and abnormal fat accumulation can increase the mechanical force on weight‐bearing joints and is an important risk factor for increasing the incidence of KOA. 88 However, the consistency between the KOA model induced by this method and the degree of human KOA lesions remains to be further explored.

Noninvasive induction method

The three main noninvasive KOA models were the intra‐articular fracture of the tibial plateau, cyclic articular cartilage compression of the tibia, and ACL rupture via excessive compression of the tibia. 46 The main advantage of noninvasive OA models is their noninvasive nature, where no specific microsurgical skills are needed, as well as the reduced potential impact of surgery on disease development. 89 A few noninvasive models have been described for posttraumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) studies. Sclerosin (SOST) is a Wnt antagonist involved in the regulation of chondrocyte function in KOA. A study using SOST transgenic and knockout mice fixed the right knee of the mouse to apply a single dynamic compression load to replace the femoral condyle above the tibial condyle, resulting in ACL rupture and inducing the tibial compression OA injury model. It was found that the SOST transgene showed a significantly lower late PTOA phenotype at 16 weeks after injury compared to the knockout mice. 90 For KOA studies using noninvasive injury methods, careful consideration should be given to appropriate controls, each animal phenotype should be carefully described, and appropriate controls should be utilized to ensure the fidelity of results obtained using these models. 91

3.3. Model of genetic engineering technology

With the continuous progress of gene technology, methods to obtain desired specific gene defects and expressions through gene knockout, insertion, and transfection have also been applied to KOA research. Animal studies have identified a number of genes that may contribute to the development of KOA, such as TNF‐α, the cartilage catabolic factor, and matrix metalloproteinase. 92 , 93 A study using a gene mouse model of PTEN deficiency found that restriction Akt1 signaling reversed the OA phenotypes. 94 Wang et al. 95 used the Del1‐Lacz knock‐in mouse to demonstrate that DEL1, an ECM‐associated integrin‐binding protein, has a powerful biological function in chondrocytes as an antiapoptotic factor. In addition, DEL1‐deficient mice were found to have reduced amounts of cartilage measured using histomorphology and increased susceptibility to OA. There have been mouse mutations in a number of key regulatory genes and, among various other effects, increased intra‐articular chondrocyte apoptosis. 96 Yamamoto et al. 97 used 12‐week‐old SIRT1‐KI mice and wild‐type mice as control. SIRT1‐kI mice were obtained through mating of heterozygous SIRT1‐kI mice with wild‐type littermates; the KOA animal model was induced by medial meniscus instability. Immunostaining results showed that the proportion of SIRT1 and type II collagen‐positive chondrocytes in SIRT1‐kI mice was significantly higher than that in control mice. This suggests that SIRT1 overexpression may be a promising strategy for the treatment of OA, and the study has shown that delayed progression of OA is associated with reduced levels of chondrodegrading enzymes, acetylated NF‐κB p65, and markers of apoptosis.

Transgenic technology avoids possible operational errors in artificial modeling, eliminates additional damage to animals caused by infection and trauma in the process of modeling, and reduces the pain of animals ethically. These are the advantages of the application of this technology. However, because the transgenic technology is not fully mature at the present stage, there are still uncontrollable factors such as gene knockout and insertion. It is difficult to determine whether these factors will regulate the expression of some unknown proteins in the process of gene change and affect other physiological changes in the body. Therefore, the application of transgenic animal models still needs the continued development of technology.

4. ANIMAL MODEL OF KOA WITH INTERVENTION OF CHINESE HERBAL COMPOUNDS

In recent years, TCM has gained traction in the treatment of KOA with little adverse reactions. The results of meta‐analysis based on clinical randomized controlled trials showed that the efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal compounds in the treatment of KOA were superior to Western medicines or placebo, which have broad clinical application prospects. 20 The theory of Chinese medicine states five main TCM syndromes of KOA: qi stagnation and blood stasis, cold and damp obstruction, dampness–heat obstruction, liver and kidney deficiency, and qi and blood weakness, which involve many TCM compounds. TCM compounds have multicomponent, multipathway, and multitarget characteristics. In the prevention and treatment of KOA, it is safe and effective and possesses syndrome differentiation. It can improve local microcirculation, accelerate the metabolism of inflammatory substances, reduce inflammatory factors in the knee tissue, and prevent the apoptosis of chondrocytes. KOA belongs to TCM “bi syndrome bone Bi” and other categories; its pathogenesis is still under study. 98

The basic pathogenesis of KOA is dampness, heat, and deficiency, and the treatment should be based on methods that can remove dampness and heat, eliminate discomfort, and relieve pain. Duhuo Jisheng Decoction is a traditional prescription for the treatment of KOA, which has not only remarkable clinical effects but also a few adverse reactions, and plays an important role in anti‐inflammation, cartilage protection, anti‐oxidation, and anti‐apoptosis. 99 Chen et al. 100 induced the KOA mouse model by injecting 0.1 mL of 4% papain solution into the right‐knee cavity of mice. After 3 weeks, mice in the model group were administrated low (2 g/kg) and high doses (4 g/kg) of Duhuo Jisheng Decoction to evaluate the efficacy of Duhuo Jisheng Decoction in the KOA mouse model. The results showed that Duhuo Jisheng Decoction could alleviate papain‐induced cartilage injury in KOA mice, which was related to regulating the immune function of spleen and reducing the overactivation of NLRP3 in knee cartilage. Qinghe dispel paralysis decoction is a common TCM formula for removing qi, dispelling wind and dampness, and strengthening spleen. 101 A study combining Western medicine with Qinghe dispel paralysis decoction to treat patients with KOA found that it can better relieve joint pain, improve motor ability, and reduce the development of inflammation in the organism, with high safety and effectiveness. 102 Paeonia lactiflora and Commiphora myrrha have been used in traditional medicines for treating joint diseases. Lee et al. 103 mixed the two herbs in the ratio 3:1 and named the herbal mixture HT083. It was injected into the MIA‐induced KOA SD rat model. HT083 in this study has exhibited remarkable analgesic properties by increasing weight‐bearing capacities in MIA rats and decreasing twisting responses in ICR mice induced by acetic acid.

In recent years, researchers have mainly explored the mechanism of TCM compounds in treating KOA using aspects of Wnt/β‐catenin, TLR4/MyD88/NF‐κB, p38 MAPK, and PI3K/AKT and other signaling pathways. For instance, Ju et al. 104 induced the KOA model by injecting 1 mg of MIA into the right‐knee joint of rats and administered Huoxuezhitong capsule (HXZT) powder suspension 2 days after the successful establishment of the model. This study confirmed that HXZT can reverse the lipopolysaccharide‐induced cellular inflammatory response by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/NF‐κB pathway to alleviate the progression of KOA. Shaoyao‐Gancao Tang (SGT) is the most commonly used treatment for inflammatory pain‐related disorders in clinical practice. Sui et al. 105 injected Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA) into the left hind paw of rats to induce pain models of arthritis rats. It was confirmed that SGT has significant analgesic and anti‐inflammatory effects on arthritis rats, and its therapeutic activity may be achieved by reversing FCA‐induced elevation of TRPV1 channel expression and function. Ruyi Zhenbao Pill (RZP) is a traditional Tibetan OA treatment formula. Li et al. 106 used high‐performance liquid chromatography to identify the active components of RZP and injected 0.15 mL of 4% papain solution into the knee joint of rats to induce OA animal models. After 28 days of intragastric administration of RZP (0.45, 0.9 g/kg), clinical observation was performed to detect pathological changes and serum biochemical indexes. The results showed that RZP may inhibit knee swelling and arthralgia in OA rats by inhibiting IL‐1β/NF‐κB pathway and inhibiting inflammatory response through various compounds of RZP. To sum up, the results of a number of studies indicate that TCM compounds have a significant effect on the treatment of KOA, but the composition of TCM compounds is complex. Further exploration is required to confirm the effectiveness of different components in the treatment of KOA and the specific mechanism of action.

5. CONCLUSION AND PROSPECT

KOA is a chronic degenerative joint disease characterized by the destruction and proliferation of bone inflammation. The pathogenesis of KOA has long been under research and exploration. It is well accepted that the pathogenesis of KOA is related to the interaction between three major factors, aging, genetic susceptibility, and environmental influence, 107 but a few effective treatments can slow the progression of KOA. Therefore, it is important to select suitable animal models of KOA to further study the pathogenesis and treatment strategies of the disease. At present, various KOA models have been established for scientific and experimental research. The existing animal models of KOA include the genetic model, surgical‐induced model, and drug‐induced model. The spontaneous model is an ideal method similar to the pathological process of KOA, but its modeling cycle is long and the cost is high. Drug‐induced models, such as the sodium iodoacetate intra‐articular injection model and collagenase induction model, are widely used in the screening and comparison of KOA drugs and the evaluation of therapeutic intervention efficacy, and the modeling cycle is short and the cost is low. However, drug‐induced models do not fully simulate the natural onset of human KOA and the study of traumatic KOA in humans. Surgical induction models, such as intra‐articular membrane‐forming models with a high success rate, good controllability, and strong targeting, are most suitable for the study of tissue and pathological characteristics of KOA at different traumatic stages. However, surgically induced trauma causes early release of inflammatory substances, which is not suitable for the study of inflammatory factors in KOA. Based on the evidence summarized earlier, almost all animal models of KOA have some limitations.

TCM has a long history and extensive experience in the treatment of KOA, and its treatment methods are based on the theory of TCM, including acupuncture, internal administration of TCM, external application, and massage. 18 Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of KOA with integrative medicine based on TCM concluded that KOA can be divided into the following syndrome types: dampness‐cold obstruction syndrome, dampness–heat obstruction syndrome, qi‐blood stagnation syndrome, deficiency in liver and kidney, and qi‐blood weakness syndrome. 108 TCM is effective in the prevention and treatment of KOA, and the adverse reactions are minimal, and patient compliance is high; compared with side effects like trauma and high cost of Western medicine treatment of KOA, TCM has many unique advantages. As a traditional treatment method, Chinese medicine compounds have shown certain efficacy in alleviating knee pain, reducing inflammation, and improving knee joint function. In clinic, compared to single herbs, doctors prefer to treat KOA with TCM compounds, which are complex mixtures of numerous herbs to maximize efficacy, and toxicity or adverse effects are minimized through the interaction of different herbs. 18 However, the drug composition of Chinese medicine compounds is relatively complex, and the effective composition and the specific mechanism of action are not clear; relevant basic research needs to be further strengthened. TCM classifies KOA into kidney deficiency and pulp deficiency, Yang deficiency and cold coagulation, and blood stasis blocking, which are often confused with existing animal models.

Thus far, there is no effective and recognized modeling method, and there are many limitations to the study of TCM treatment of KOA. Therefore, the combined model of disease and syndrome has become an important trend in the development of animal models of TCM treatment of KOA. In general, the selection and research of animal models of KOA should be aimed at better understanding the pathogenesis of this disease, discovering new therapeutic approaches, properly considering the ethical and legal issues in animal research, and making them better mimic the pathological characteristics and clinical manifestations of human KOA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Rong Sun designed and supervised the manuscript. Xuyu Song and Ying Liu wrote the manuscript. Lei Zhang and Hang Du revised the manuscript. Siyi Chen, Huijie Zhang, and Xianhui Shen contributed to manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Cutting Edge Development Fund of Advanced Medical Research Institute (GYY2023QY01) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (certificate number: 2023M732093).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This review article adheres to ethical principles. All sources are appropriately credited, and any potential biases are minimized. The information presented is accurate and objective, ensuring a fair and transparent exploration of the topic.

Song X, Liu Y, Chen S, et al. Knee osteoarthritis: A review of animal models and intervention of traditional Chinese medicine. Anim Models Exp Med. 2024;7:114‐126. doi: 10.1002/ame2.12389

Xuyu Song and Ying Liu have contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Phillips M, Bhandari M, Grant J, et al. A systematic review of current clinical practice guidelines on intra‐articular hyaluronic acid, corticosteroid, and platelet‐rich plasma injection for knee osteoarthritis: an international perspective. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(8):23259671211030272. doi: 10.1177/23259671211030272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun X, Zhen X, Hu X, et al. Osteoarthritis in the middle‐aged and elderly in China: prevalence and influencing factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4701. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ren Y, Hu J, Tan J, et al. Incidence and risk factors of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis among the Chinese population: analysis from a nationwide longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1491. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09611-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vitaloni M, Botto‐van Bemden A, Sciortino Contreras RM, et al. Global management of patients with knee osteoarthritis begins with quality of life assessment: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):493. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2895-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang X, Wang S, Zhan S, et al. The prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in China: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(3):648‐653. doi: 10.1002/art.39465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rezus E, Burlui A, Cardoneanu A, Macovei LA, Tamba BI, Rezus C. From pathogenesis to therapy in knee osteoarthritis: bench‐to‐bedside. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):2697. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kandemirli GC, Basaran M, Kandemirli S, Inceoglu LA. Assessment of knee osteoarthritis by ultrasonography and its association with knee pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2020;33(4):711‐717. doi: 10.3233/bmr-191504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non‐surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(11):1578‐1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Puigdellivol J, Comellas Berenger C, Pérez Fernández M, et al. Effectiveness of a dietary supplement containing hydrolyzed collagen, chondroitin sulfate, and glucosamine in pain reduction and functional capacity in osteoarthritis patients. J Diet Suppl. 2019;16(4):379‐389. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2018.1461726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martello E, Bigliati M, Adami R, et al. Efficacy of a dietary supplement in dogs with osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo‐controlled, double‐blind clinical trial. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allaeys C, Arnout N, Van Onsem S, Govaers K, Victor J. Conservative treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2020;86(3):412‐421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wolff DG, Christophersen C, Brown SM, Mulcahey MK. Topical nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Phys Sportsmed. 2021;49(4):381‐391. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2021.1886573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao J, Huang H, Liang G, Zeng LF, Yang W, Liu J. Effects and safety of the combination of platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03262-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang H, Ma B. Healthcare and scientific treatment of knee osteoarthritis. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:5919686. doi: 10.1155/2022/5919686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15. Peng H, Ou A, Huang X, et al. Osteotomy around the knee: the surgical treatment of osteoarthritis. Orthop Surg. 2021;13(5):1465‐1473. doi: 10.1111/os.13021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malfait AM, Little CB. On the predictive utility of animal models of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0747-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu FS, Li Y, Guo XS, Liu RC, Zhang HY, Li Z. Advances in traditional Chinese medicine as adjuvant therapy for diabetic foot. World J Diabetes. 2022;13(10):851‐860. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v13.i10.851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang M, Liu L, Zhang CS, et al. Mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine in treating knee osteoarthritis. J Pain Res. 2020;13:1421‐1429. doi: 10.2147/jpr.S247827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fan Z, Bai‐yi C, Kang W, et al. Mechanism and experimental verification of jiawei duhuo jisheng mixture intreatment of knee osteoarthritis based on network pharmacology. Chin Pharmacol Bull. 2023;39(2):340‐347. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liang Y, Xu Y, Zhu Y, Ye H, Wang Q, Xu G. Efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine for knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytomedicine. 2022;100:154029. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCoy AM. Animal models of osteoarthritis: comparisons and key considerations. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(5):803‐818. doi: 10.1177/0300985815588611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gregory MH, Capito N, Kuroki K, Stoker AM, Cook JL, Sherman SL. A review of translational animal models for knee osteoarthritis. Art Ther. 2012;2012:764621. doi: 10.1155/2012/764621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang FS, Kuo CW, Ko JY, et al. Irisin mitigates oxidative stress, chondrocyte dysfunction and osteoarthritis development through regulating mitochondrial integrity and autophagy. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(9):810. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poole R, Blake S, Buschmann M, et al. Recommendations for the use of preclinical models in the study and treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(Suppl 3):S10‐S16. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gerwin N, Bendele AM, Glasson S, Carlson CS. The OARSI histopathology initiative – recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the rat. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(Suppl 3):S24‐S34. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lv S, Wang X, Jin S, Shen S, Wang R, Tong P. Quercetin mediates TSC2‐RHEB‐mTOR pathway to regulate chondrocytes autophagy in knee osteoarthritis. Gene. 2022;820:146209. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lozano J, Saadat E, Li X, Majumdar S, Ma CB. Magnetic resonance T(1 rho) imaging of osteoarthritis: a rabbit ACL transection model. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27(5):611‐616. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rebai MA, Sahnoun N, Abdelhedi O, et al. Animal models of osteoarthritis: characterization of a model induced by Mono‐Iodo‐Acetate injected in rabbits. Libyan JMed. 2020;15(1):1753943. doi: 10.1080/19932820.2020.1753943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang L, Riihioja I, Tanska P, et al. Early changes in osteochondral tissues in a rabbit model of post‐traumatic osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2021;39(12):2556‐2567. doi: 10.1002/jor.25009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cook JL, Hung CT, Kuroki K, et al. Animal models of cartilage repair. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3(4):89‐94. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.34.2000238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Proffen BL, McElfresh M, Fleming BC, Murray MM. A comparative anatomical study of the human knee and six animal species. Knee. 2012;19(4):493‐499. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teeple E, Jay GD, Elsaid KA, Fleming BC. Animal models of osteoarthritis: challenges of model selection and analysis. AAPS J. 2013;15(2):438‐446. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9454-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lampropoulou‐Adamidou K, Lelovas P, Karadimas EV, et al. Useful animal models for the research of osteoarthritis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(3):263‐271. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1205-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moreau M, Pelletier JP, Lussier B, et al. A posteriori comparison of natural and surgical destabilization models of canine osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:180453. doi: 10.1155/2013/180453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Korchi AM, Cengarle‐Samak A, Okuno Y, et al. Inflammation and hypervascularization in a large animal model of knee osteoarthritis: imaging with pathohistologic correlation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(7):1116‐1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2018.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim YS, Kim YI, Koh YG. Intra‐articular injection of human synovium‐derived mesenchymal stem cells in beagles with surgery‐induced osteoarthritis. Knee. 2021;28:159‐168. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Veronesi F, Berni M, Marchiori G, et al. Evaluation of cartilage biomechanics and knee joint microenvironment after different cell‐based treatments in a sheep model of early osteoarthritis. Int Orthop. 2021;45(2):427‐435. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04701-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Orth P, Meyer HL, Goebel L, et al. Improved repair of chondral and osteochondral defects in the ovine trochlea compared with the medial condyle. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(11):1772‐1779. doi: 10.1002/jor.22418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cox LA, Comuzzie AG, Havill LM, et al. Baboons as a model to study genetics and epigenetics of human disease. ILAR J. 2013;54(2):106‐121. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilt038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Housman G, Havill LM, Quillen EE, Comuzzie AG, Stone AC. Assessment of DNA methylation patterns in the bone and cartilage of a nonhuman primate model of osteoarthritis. Cartilage. 2019;10(3):335‐345. doi: 10.1177/1947603518759173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yan Y, Yi X, Duan Y, et al. Alteration of the gut microbiota in rhesus monkey with spontaneous osteoarthritis. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21(1):328. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02390-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Poulet B. Models to define the stages of articular cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis development. Int J Exp Pathol. 2017;98(3):120‐126. doi: 10.1111/iep.12230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gadelkarim M, Abd Elmegeed A, Allam AH, et al. Safety and efficacy of adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and m‐analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2022;89(5):105404. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2022.105404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Afzali MF, Pannone SC, Martinez RB, et al. Intravenous injection of adipose‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells benefits gait and inflammation in a spontaneous osteoarthritis model. J Orthop Res. 2023;41(4):902‐912. doi: 10.1002/jor.25431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramos‐Mucci L, Javaheri B, van 't Hof R, et al. Meniscal and ligament modifications in spontaneous and post‐traumatic mouse models of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02261-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuyinu EL, Narayanan G, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. Animal models of osteoarthritis: classification, update, and measurement of outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;11:19. doi: 10.1186/s13018-016-0346-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ishaq N, Gul S, Gul M, Ata N, Batool S, Mehdi Q. Chondroprotective effects of intra‐articular hyaluronic acid and triamcinolone in murine model of osteoarthritis. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2022;34(1):82‐86. doi: 10.55519/jamc-01-9566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kong G, Wang J, Li R, Huang Z, Wang L. Ketogenic diet ameliorates inflammation by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s13075-022-02802-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Juskovic A, Nikolic M, Ljujic B, et al. Effects of combined allogenic adipose stem cells and hyperbaric oxygenation treatment on pathogenesis of osteoarthritis in knee joint induced by monoiodoacetate. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):7695. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Park J, Lee J, Kim KI, et al. A pathophysiological validation of collagenase II‐induced biochemical osteoarthritis animal model in rabbit. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;15(4):437‐444. doi: 10.1007/s13770-018-0124-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Go EJ, Kim SA, Cho ML, Lee KS, Shetty AA, Kim SJ. A combination of surgical and chemical induction in a rabbit model for osteoarthritis of the knee. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2022;19(6):1377‐1388. doi: 10.1007/s13770-022-00488-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gu W, Shi Z, Song G, Zhang H. MicroRNA‐199‐3p up‐regulation enhances chondrocyte proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in knee osteoarthritis via DNMT3A repression. Inflamm Res. 2021;70(2):171‐182. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01430-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang XD, Wan XC, Liu AF, Li R, Wei Q. Effects of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells loaded with graphene oxide granular lubrication on cytokine levels in animal models of knee osteoarthritis. Int Orthop. 2021;45(2):381‐390. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04584-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li X, Xu Y, Li H, et al. Verification of pain‐related neuromodulation mechanisms of icariin in knee osteoarthritis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;144:112259. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wei B, Zhang Y, Tang L, Ji Y, Yan C, Zhang X. Protective effects of quercetin against inflammation and oxidative stress in a rabbit model of knee osteoarthritis. Drug Dev Res. 2019;80(3):360‐367. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang SL, Zhang KS, Wang JF, et al. Corresponding changes of autophagy‐related genes and proteins in different stages of knee osteoarthritis: an animal model study. Orthop Surg. 2022;14(3):595‐604. doi: 10.1111/os.13057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang L, Li M, Li X, et al. Characteristics of sensory innervation in synovium of rats within different knee osteoarthritis models and the correlation between synovial fibrosis and hyperalgesia. J Adv Res. 2022;35:141‐151. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Luc B, Gribble PA, Pietrosimone BG. Osteoarthritis prevalence following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and numbers‐needed‐to‐treat analysis. J Athl Train. 2014;49(6):806‐819. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Webster KE, Hewett TE. Anterior cruciate ligament injury and knee osteoarthritis: an umbrella systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin J Sport Med. 2022;32(2):145‐152. doi: 10.1097/jsm.0000000000000894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sun W, Yue M, Xi G, Wang K, Sai J. Knockdown of NEK7 alleviates anterior cruciate ligament transection osteoarthritis (ACLT)‐induced knee osteoarthritis in mice via inhibiting NLRP3 activation. Autoimmunity. 2022;55(6):398‐407. doi: 10.1080/08916934.2022.2093861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yang SY, Fang CJ, Chen YW, et al. Hericium erinaceus mycelium ameliorates in vivo progression of osteoarthritis. Nutrients. 2022;14(13):2605. doi: 10.3390/nu14132605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bai H, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. L‐theanine reduced the development of knee osteoarthritis in rats via its anti‐inflammation and anti‐matrix degradation actions: in vivo and in vitro study. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):1988. doi: 10.3390/nu12071988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Qian JJ, Xu Q, Xu WM, Cai R, Huang GC. Expression of VEGF‐A signaling pathway in cartilage of ACLT‐induced osteoarthritis mouse model. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):379. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02528-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Culley KL, Singh P, Lessard S, et al. Mouse models of osteoarthritis: surgical model of post‐traumatic osteoarthritis induced by destabilization of the medial meniscus. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2221:223‐260. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0989-7_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Qian Z, Ru X, Liu C, Huang X, Sun Q. Fraxin prevents knee osteoarthritis through inhibiting chondrocyte apoptosis in an experimental rat osteoarthritis model. Protein Pept Lett. 2021;28(11):1298‐1302. doi: 10.2174/0929866528666211022152556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wakayama T, Saita Y, Nagao M, et al. Intra‐articular injections of the adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cells suppress progression of a mouse traumatic knee osteoarthritis model. Cartilage. 2022;13(4):148‐156. doi: 10.1177/19476035221132262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Deng Z, Chen F, Liu Y, et al. Losartan protects against osteoarthritis by repressing the TGF‐β1 signaling pathway via upregulation of PPARγ. J Orthop Translat. 2021;29:30‐41. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2021.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhou H, Shen X, Yan C, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate osteoarthritis of the knee in mice model by interacting with METTL3 to reduce m6A of NLRP3 in macrophage. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yu PM, Lin Y, Zhang C, et al. Low‐frequency vibration promotes tumor necrosis factor‐α production to increase cartilage degeneration in knee osteoarthritis. Cartilage. 2021;13(2_suppl):1398s‐1406s. doi: 10.1177/1947603520931178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kaneko Y, Tanigawa N, Sato Y, et al. Oral administration of N‐acetyl cysteine prevents osteoarthritis development and progression in a rat model. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):18741. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55297-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zamborsky R, Danisovic L. Surgical techniques for knee cartilage repair: an updated large‐scale systematic review and network meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(3):845‐858. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.11.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tawonsawatruk T, Sriwatananukulkit O, Himakhun W, Hemstapat W. Comparison of pain behaviour and osteoarthritis progression between anterior cruciate ligament transection and osteochondral injury in rat models. Bone Joint Res. 2018;7(3):244‐251. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.73.Bjr-2017-0121.R2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yazdi MM, Jamalaldini MH, Sobhan MR, et al. Association of ESRα gene Pvu II T>C, XbaI a>G and BtgI G>a polymorphisms with knee osteoarthritis susceptibility: a systematic review and meta‐analysis based on 22 case‐control studies. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2017;5(6):351‐362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sniekers YH, Weinans H, Bierma‐Zeinstra SM, van Leeuwen JP, van Osch GJ. Animal models for osteoarthritis: the effect of ovariectomy and estrogen treatment – a systematic approach. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(5):533‐541. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang SP, Wu PK, Lee CH, Shih CM, Chiu YC, Hsu CE. Association of osteoporosis and varus inclination of the tibial plateau in postmenopausal women with advanced osteoarthritis of the knee. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):223. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04090-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Fontinele RG, Mariotti VB, Vazzoleré AM, Ferrão JS, Kfoury JR Jr, De Souza RR. Menopause, exercise, and knee. What happens? Microsc Res Tech. 2013;76(4):381‐387. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Arai T, Suzuki‐Narita M, Takeuchi J, et al. Analgesic effects and arthritic changes following intra‐articular injection of diclofenac etalhyaluronate in a rat knee osteoarthritis model. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):960. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05937-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Liu Y, Xu S, Zhang H, et al. Stimulation of α7‐nAChRs coordinates autophagy and apoptosis signaling in experimental knee osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(5):448. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03726-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Deshmukh V, O'Green AL, Bossard C, et al. Modulation of the Wnt pathway through inhibition of CLK2 and DYRK1A by lorecivivint as a novel, potentially disease‐modifying approach for knee osteoarthritis treatment. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(9):1347‐1360. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ikeda R, Arimura D, Saito M. Expression of piezo mRNA is unaffected in a rat model of knee osteoarthritis. Molecular Pain. 2021;17:17448069211014059. doi: 10.1177/17448069211014059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Spassim MR, Dos Santos RT, Rossato‐Grando LG, et al. Intra‐articular ozone slows down the process of degeneration of articular cartilage in the knees of rats with osteoarthritis. Knee. 2022;35:114‐123. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2022.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yamada EF, Salgueiro AF, Goulart ADS, et al. Evaluation of monosodium iodoacetate dosage to induce knee osteoarthritis: relation with oxidative stress and pain. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(3):399‐410. doi: 10.1111/1756-185x.13450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pishgahi A, Zamani M, Mehdizadeh A, et al. The therapeutic effects of autologous conditioned serum on knee osteoarthritis: an animal model. BMC Res Notes. 2022;15(1):277. doi: 10.1186/s13104-022-06166-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yu M, Wang D, Chen X, Zhong D, Luo J. BMSCs‐derived mitochondria improve osteoarthritis by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis in chondrocytes. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18(8):3092‐3111. doi: 10.1007/s12015-022-10436-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Cong S, Meng Y, Wang L, et al. T‐614 attenuates knee osteoarthritis via regulating Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):403. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02530-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Endisha H, Datta P, Sharma A, et al. MicroRNA‐34a‐5p promotes joint destruction during osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):426‐439. doi: 10.1002/art.41552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Datta P, Zhang Y, Parousis A, et al. High‐fat diet‐induced acceleration of osteoarthritis is associated with a distinct and sustained plasma metabolite signature. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8205. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07963-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Silverwood V, Blagojevic‐Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan JL, Protheroe J, Jordan KP. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(4):507‐515. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Poulet B. Non‐invasive loading model of murine osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(7):40. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0590-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chang JC, Christiansen BA, Murugesh DK, et al. SOST/sclerostin improves posttraumatic osteoarthritis and inhibits MMP2/3 expression after injury. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(6):1105‐1113. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Christiansen BA, Guilak F, Lockwood KA, et al. Non‐invasive mouse models of post‐traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(10):1627‐1638. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Arakawa K, Takahata K, Enomoto S, et al. Effect of suppression of rotational joint instability on cartilage and meniscus degeneration in mouse osteoarthritis model. Cartilage. 2022;13(1):19476035211069239. doi: 10.1177/19476035211069239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Fan Q, Liu Z, Shen C, et al. Microarray study of gene expression profile to identify new candidate genes involved in the molecular mechanism of leptin‐induced knee joint osteoarthritis in rat. Hereditas. 2018;155:4. doi: 10.1186/s41065-017-0039-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Xie J, Lin J, Wei M, et al. Sustained Akt signaling in articular chondrocytes causes osteoarthritis via oxidative stress‐induced senescence in mice. Bone Res. 2019;7:23. doi: 10.1038/s41413-019-0062-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wang Z, Tran MC, Bhatia NJ, et al. Del1 knockout mice developed more severe osteoarthritis associated with increased susceptibility of chondrocytes to apoptosis. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Momoeda M, de Vega S, Kaneko H, et al. Deletion of hyaluronan‐binding protein involved in hyaluronan depolymerization (HYBID) results in attenuation of osteoarthritis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2021;191(11):1986‐1998. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yamamoto T, Miyaji N, Kataoka K, et al. Knee osteoarthritis progression is delayed in silent information regulator 2 ortholog 1 knock‐in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10685. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Primorac D, Molnar V, Rod E, et al. Knee osteoarthritis: a review of pathogenesis and state‐of‐the‐art non‐operative therapeutic considerations. Genes. 2020;11(8):854. doi: 10.3390/genes11080854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zi‐Qi Z, Xue‐Feng G, Yong‐ju Y. Research progress on the mechanism of Duhuo Jisheng decoction in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Tradit Chin Med. 2021;36. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Chen W, Zhuang Y, Peng W, Wei C, Zhang S, Jian‐wei W. Duhuo Jizhi decoction can relieve cartilage damage in mice with knee osteoarthritis by regulating immune function effect. Chin Tradit Patent Med. 2023;45(8):2726‐2731. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Guo JM, Xiao Y, Cai TY, et al. Chinese medicine involving triple rehabilitation therapy for knee osteoarthritis in 696 outpatients: a multi‐center, randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2021;27(10):729‐736. doi: 10.1007/s11655-021-3488-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Xie L, Li M. Analysis of clinical efficacy of clearing heat and dispelling paralysis soup in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee joint and its effect on patients' motor function. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:5104121. doi: 10.1155/2022/5104121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 103. Lee D, Ju MK, Kim H. Commiphora extract mixture ameliorates monosodium iodoacetate‐induced osteoarthritis. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1477. doi: 10.3390/nu12051477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ju L, Hu P, Chen P, et al. Huoxuezhitong capsule ameliorates MIA‐induced osteoarthritis of rats through suppressing PI3K/Akt/NF‐κB pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;129:110471. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sui F, Zhou HY, Meng J, et al. A Chinese herbal decoction, Shaoyao‐Gancao Tang, exerts analgesic effect by down‐regulating the TRPV1 channel in a rat model of arthritic pain. Am J Chin Med. 2016;44(7):1363‐1378. doi: 10.1142/s0192415x16500762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Li Q, Xu JY, Hu X, et al. The protective effects and mechanism of Ruyi Zhenbao pill, a Tibetan medicinal compound, in a rat model of osteoarthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;308:116255. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Dunn CM, Jeffries MA. The microbiome in osteoarthritis: a narrative review of recent human and animal model literature. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2022;24(5):139‐148. doi: 10.1007/s11926-022-01066-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Zeng L, Zhou G, Yang W, Liu J. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of knee osteoarthritis with integrative medicine based on traditional Chinese medicine. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1260943. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1260943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]