Abstract

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are aquatic vertebrates with significant homology to their terrestrial counterparts. While zebrafish have a centuries-long track record in developmental and regenerative biology, their utility has grown exponentially with the onset of modern genetics. This is exemplified in studies focused on skeletal development and repair. Herein, the numerous contributions of zebrafish to our understanding of the basic science of cartilage, bone, tendon/ligament, and other skeletal tissues are described, with a particular focus on applications to development and regeneration. We summarize the genetic strengths that have made the zebrafish a powerful model to understand skeletal biology. We also highlight the large body of existing tools and techniques available to understand skeletal development and repair in the zebrafish and introduce emerging methods that will aid in novel discoveries in skeletal biology. Finally, we review the unique contributions of zebrafish to our understanding of regeneration and highlight diverse routes of repair in different contexts of injury. We conclude that zebrafish will continue to fill a niche of increasing breadth and depth in the study of basic cellular mechanisms of skeletal biology.

Keywords: zebrafish, skeleton, development, regeneration, genetic engineering, transgenesis

1. Introduction

Animal models have played important roles in uncovering the genetic basis of skeletal development, disorders, homeostasis, and diseases. Traditionally, mice have been the model organism of choice due to the large number of available genetic tools and the ability to induce targeted genetic modifications in embryonic stem cells. The recent development of a wide array of new techniques for genetic manipulation has broadened the range of model organisms that can efficiently be genetically modified. Among these, the zebrafish has become a powerful vertebrate model system due to its external fertilization, rapid early development, high fecundity, and transparency at embryonic stages [1]. Most importantly, zebrafish share 70% of genes with humans, making zebrafish an ideal system to model human development and diseases [2]. While the zebrafish has predominantly been used to study early developmental processes, more recently this small freshwater fish has also been used to interrogate post-embryonic stages, especially with regard to the musculoskeletal system [3–12].

A broad range of methods are available to genetically modify zebrafish and are being used in both forward and reverse genetic approaches. The recent adaptation of the clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) system for genome editing significantly expanded the options for genetic modifications in zebrafish. This has led to a large increase in the number of generated targeted mutants and transgenic lines. Currently, there are 53,522 mutant alleles and 31,964 transgenic lines recorded in the Zebrafish Information Network (https://zfin.org/) [13]. These genetically modified animals can now be readily combined with single cell genomic technologies at both a tissue and whole organism level to define pathways important in skeletal development, regeneration and disease. In this review, we will highlight the methods available for genetic manipulation and how these tools have been used to study skeletal development and regeneration.

2. Tools for Genetic Manipulation in Zebrafish

The zebrafish gained popularity as a model system because of its amenability to genetic manipulation, especially as a means to perform large scale forward genetic screens in a vertebrate. Forward genetic screens are a powerful approach to identify genes important for a specific developmental process in an unbiased manner. Here, mutations are randomly induced throughout the genome and mutant progeny are identified by their altered phenotype, followed by mapping to identify the underlying genetic change. On the other hand, targeted mutagenesis allows for the genetic manipulation of a specific gene of interest to study its function. In this section we describe the different methods available for genetic modification of zebrafish and the approaches they are used in.

2.1. Random mutagenesis

In random mutagenesis, mutations are induced throughout the genome to discover gene function. This technique has been used in both forward and reverse genetic approaches. Several methods have been shown to be effective in zebrafish, including induction of mutations through gamma-rays and ultraviolet (UV) light [14–16]. The two major forms of mutagenesis employed in zebrafish today are: (1) chemical and (2) insertional mutagenesis and are discussed in more detail in the sections below.

2.1.1. Chemical mutagenesis

The chemical N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) is a highly potent mutagen and is widely used for the random induction of point mutations. In zebrafish, point mutations can be generated at a frequency of about 1 in 500–1000, although with varying frequency for different loci [17–19]. Multiple large scale forward genetic screens using chemical mutagenesis have been performed in zebrafish, including screens for early craniofacial development and changes in adult skeletal morphology [20–30]. They have led to the discovery of many genes and gene networks that play a role in skeletal development and disease. Identification of the underlying genetic changes used to be very time consuming and labor intensive, but the recent adaptation of next-generation sequencing methods to map mutations has sped up this process significantly [31–40]. However, due to the high number of polymorphisms in the zebrafish genome and the lack of inbred strains, some phenotype-causing mutations, especially in non-coding regions, remain challenging to identify. Therefore, insertional mutagenesis tools have been developed which allow for the rapid identification of the integration site and thereby of the affected gene (see section 2.1.2).

In addition to forward genetic screens, ENU mutagenesis has also been employed in reverse genetic approaches, such as Targeting Induced Local Lesions in Genomes (TILLING). Here, progeny of mutagenized fish are screened for mutations in genes of interest by amplification of the region of interest followed by either Cel1 digestion or sequencing, before phenotyping [41]. Initially this approach was used to target a single gene. However, taking advantage of next-generation sequencing technologies allowing for the sequencing of entire exomes and genomes, the Zebrafish Mutation Project used exome sequencing of a large population of F1 progeny from mutagenized fish to identify ENU induced coding mutations genome-wide [42]. Using this approach, knockout alleles in over 60% of zebrafish genes were identified and are available to the community (Table 1) (https://www.sanger.ac.uk/collaboration/zebrafish-mutation-project/,https://zmp.buschlab.org/).

Table 1.

Databases and collections of genetically modified zebrafish

| Zebrafish Mutation Project (ZMP) | ENU induced mutants, predicted loss-of-function mutations in > 60% of genes of the zebrafish genome | https://zmp.buschlab.org/ [42] |

| Zebrafish Insertion Collection (ZInC) | Retroviral insertion lines, over 3000 mutated genes | https://research.nhgri.nih.gov/ZinC/ [43] |

| Zebrafish Gene Trap and Enhancer Trap Database (zTRAP) | GFP and Gal4FF expressing gene and enhancer traps | https://ztrap.nig.ac.jp/ztrap/ [44] |

| NIGKOF Knock Out Fish Project | Knockout lines generated through transposon insertions in the zTRAP project | https://ztrap.nig.ac.jp/knockout/faces/insertion/FindInsertion.jsp |

| ZETRAP 2.0 | GFP and KillerRed expressing enhancer trap lines | [45] |

| FlipTrap | Cre mediated switch between protein and gene trap, constructs are flanked by FRT sites allowing replacement of the FlipTrap cassette | https://fliptrap.usc.edu/static/contact.html [46] |

| CreZoo | Gene trap lines expressing mCherry-T2A-CreERT2 | https://dresden-technologieportal.de/en/services/view/id/209 [47] |

| trap-TRAP | Enhancer trap lines for Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification (TRAP) | https://amfermin.wixsite.com/website [48] |

| ZAKOC | Zebrafish All-Gene KO Consortium for Chromosome 1 |

http://www.zfish.cn/TargetList.aspx

http://zfin.org/action/publication/ZDB-PUB-171002-4/feature-list [49] |

| zfishbook | International Zebrafish Protein Trap Consortium database, lines generated with gene-break transposons | http://www.zfishmeta.org/ [50] |

| Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN) | The most comprehensive database of genetic and genomic data for zebrafish, including mutant alleles and transgenic lines | https://zfin.org/ [13] |

| Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC) | A central repository for zebrafish wildtype and mutant strains, as well as zebrafish related materials. | http://zebrafish.org |

| European Zebrafish Resource Center (EZRC) | Repository for zebrafish lines from European researchers and materials | https://www.ezrc.kit.edu/ |

| China Zebrafish Resource Center (CZRC) | Repository for zebrafish lines, resources and technology | http://en.zfish.cn/ |

2.1.2. Insertional mutagenesis

The drawback of chemical mutagenesis is the potential difficulty in identifying the underlying gene mutation, which can be alleviated through the use of insertional mutagenesis methods. In insertional mutagenesis, random integration of DNA into the genome is used as a mutagen, which enables rapid identification of the mutated region as the donor DNA works as a tag for the integration site [51]. The first insertional screens in zebrafish have been performed by injection of pseudotyped retrovirus into blastula stage embryos [52, 53]. Subsequently, the viral DNA integrates into the genome and, when integrated into the germline, is transmitted to the progeny. These retroviral insertion screens have achieved efficiencies of mutagenesis of about one ninth of that observed with ENU [53]. As mutations are caused by integration of DNA, the type of mutations that are being created are typically restricted to loss-of-function or hypomorphic alleles, while ENU can also induce neomorphic and antimorphic alleles. Several large-scale insertional mutagenesis experiments have been performed [43, 53–56] and a large number of mutants have been identified, including mutants with defects in the development of the skeleton [57]. With adaptation of Illumina sequencing methods, it is possible to identify the integration sites quickly and efficiently. Over 6000 F1 progeny carrying integrations were archived and mapped, with over 3700 carrying integrations predicted to cause null-or hypomorphic alleles [43] (Table 1).

While retrovirus-mediated mutagenesis has proven to be a very efficient method, handling and preparation of the retrovirus is challenging. Therefore, alternative methods have been explored, of which transposon-mediated random integration of DNA into the zebrafish genome was found to be the most efficient [58]. Transposon systems have been used successfully to deliver genetic material into plants and invertebrates. Several of these transposon systems have been found to work in zebrafish, including the synthetic Sleeping Beauty, the maize Ac/Dc, zebrafish TC1/mariner (ZB) and medaka Tol2 systems, with the Tol2 system being the most widely used with observed evidence of germline integration in about 50% of injected fish [59–63] Transposases recognize terminal inverted repeats (TIR), excise the TIR-flanked DNA and insert it into a different location in the genome, with different transposases showing preferences for integrations in specific regions of the genome [64]. Similar to the retrovirus insertions, depending on the location, the insertions can inactivate genes or change gene expression. For mutagenesis, TIRs are cloned into transposon donor-plasmids to facilitate integration of the insert DNA into the genome when injected with transposase mRNA. Coding sequences of fluorescent proteins or transcriptional activators can be cloned into the donor-plasmid and enable visual screening of insertion events into enhancer or coding regions, which at the same time enables investigation of expression patterns of the affected gene.

The flexible design options of the transposon donor plasmid have expanded the utility of the approach beyond the generation of loss-of-function alleles [65]. A wide variety of constructs has been used in enhancer, gene or protein trap screens, including flippase (Flp) or Cre recombinase activatable and switchable conditional cassettes [46–48, 66–69]. This has led to the generation of a large collection of available enhancer, gene and protein trap lines and new lines using new versions of donor-plasmids with novel functionalities are constantly being added (Table 1). In addition, transposon-based mutagenesis methods have been extensively used for the generation of reporter, overexpression and conditional lines (see section 2.3).

2.2. Targeted mutagenesis

While random mutagenesis is a very powerful approach, this strategy requires the generation of a large number of mutagenized fish to screen and phenotype in order to identify mutations in a specific gene of interest. In addition, not every gene is mutated with the same efficiency, and thereby, finding a mutation in a specific gene even in a large population is not guaranteed. Target specific DNA nucleases circumvent this problem and can be used to induce sequence specific double-strand breaks which can result in the formation of small INDELs at the cut site due to error prone repair during non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [70]. In addition, homology-directed repair (HDR) mechanisms enable precise, target-site specific integration of donor templates with homology arms. While the induction of INDELs using nucleases is highly efficient, methodologies for HDR in zebrafish are still evolving, with many different strategies succeeding at variable efficiencies [71].

The first nucleases shown to be effective in zebrafish were the zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) [72, 73] and the transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [74, 75]. However, after the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas system for genome editing and its successful application in zebrafish, ZFNs and TALENs have been largely replaced by the CRISPR/Cas system due to easier design and synthesis and higher versatility [76–79]. The CRISPR/Cas system for genome engineering is based on an adaptive defense mechanism in bacteria [80, 81]. It uses synthetic guide RNAs to direct a Cas protein to a target site for genome editing. Target sites consist of 17–24 nucleotides which are being integrated into the guide RNA and are restricted to loci adjacent to short protospacer-adjacent motifs (PAM), which are required for Cas protein function. The length of the target site as well as the PAM sequences are protein specific and new variations of Cas proteins are constantly added to the repertoire. Available Cas proteins include nucleases for the induction of double-strand breaks, nickases inducing single strand cuts, base editors for precise induction of base changes, transposase fusions to facilitate DNA integration and prime editors for induction of mutations through reverse transcription [82]. Many of these have been shown to be active in zebrafish, expanding the application of CRISPR/Cas beyond its utility to generate double stranded breaks for knock-outs and knock-ins [83, 84]. CRISPR/Cas tools have been developed to generate global and tissue specific knock-outs, knock-ins and point mutations and to trace individual cells through generation of CRISPR barcodes (Table 2).

Table 2:

Subset of available zebrafish CRISPR/Cas tools

| Design tools | CRISPRscan | guide RNA design tool and off target prediction | https://www.crisprscan.org/ [87] |

| CRISPRon/CRISPRoff | on-target and off-target predictions for CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing | https://rth.dk/resources/crispr/ [92, 93] | |

| Breaking-Cas | variable design of gRNAs for CRISPR/Cas for all eukaryotic genomes available on Ensembl | https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/breakingcas/ [94] | |

| CCTop/CRISPRater | tunable CRISPR/Cas target online predictor and effectivity predictor | https://cctop.cos.uni-heidelberg.de/index.html [95, 96] | |

| AceofBASEs | sgRNA design and off-target prediction tool for adenine and cytosine base editors | https://aceofbases.cos.uni-heidelberg.de/index.html [97] | |

| CHOPCHOP | CRISPR and TALEN design tool | https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/ [88, 98, 99] | |

| CRISPOR | guide RNA design tool and off target prediction | http://crispor.org [100] | |

| CRISPRdirect | guide RNA design tool and off target prediction | http://crispr.dbcls.jp/ [101] | |

| CRISPRseek | software package for gRNA design | [102] | |

| GT-Scan appsuite | gRNA and HDR template design tools(GT-Scan, TUSCAN, CUNE) | https://gt-scan.csiro.au/ [103–105] | |

| CRISPR RGEN Tools | Tools for RNA-guided endonucleases, including off target prediction, Cas gRNA design, base editing and primer editing tools | http://www.rgenome.net/cas-designer/ [106–110] | |

| Gene Sculpt Suite | tools for genome editing including design of short oligonucleotides for homology-based gene editing (GtagHD), prediction of extend of microhomology-mediated end joining repair (MEDJED) and prediction of locations with just 1–2 MMEJ alleles (MENTHU) | http://www.genesculpt.org/ [111] | |

| Mojo Hand | CRISPR and TALEN design tool | https://talendesign.org/ [112, 113] | |

| CRISPR-ERA | gRNA design tool for genome editing, repression and activation | http://crispr-era.stanford.edu/ [114] | |

| CRISPR-SKIP | design of exon skipping mutations using single-base editors | https://knoweng-0.igb.illinois.edu/crispr-skip/ [115] | |

| Databases | CRISPRz | database of validated CRISPR targets in zebrafish | https://research.nhgri.nih.gov/CRISPRz/ |

| iSTOP | database of sgRNAs for generating STOP codons | http://www.ciccialab-database.com/istop [116] | |

| SpCas9 alternatives | Spg | NGN Pam | [117] |

| SpRY | NRN PAM | [117] | |

| LbCpf1 (Cas12a) | TTTV PAM | [118] | |

| SpCas9 VQR | NGAN, NGNG PAM | [119] | |

| SpCas9 EQR | NGAG PAM | [119] | |

| SpCas9 VRER | NGCG PAM | [119] | |

| SpCas9 KKH | NNNRRT PAM | [120] | |

| SauCas9 | NNGRRT PAM | [121] | |

| AsCpf1 | TTTV PAM | [121] | |

| Nme2Cas9 | NNNNCC PAM | [121] | |

| ErCas12a | YTTN PAM | [122] | |

| ScCas9 | NNG PAM | [123] | |

| Transgenic lines | 4xUAS:NLS-Cas9,myl7:RFP | Gal4 effector line for Cas9 expression with red heart transgenesis marker | [124] |

| 4xUAS:NLS-Cas9,cryaa:EGFP | Gal4 effector line for Cas9 expression with green eye transgenesis marker | [124] | |

| hsp70l:LOXP-DsRed-LOXP-Cas9-GFP,rnu6–32:CRISPR1-tyr | Cre and heat shock controlled Cas9-GFP fusion expression | [125] | |

| ef1a:Cas9-NLS | ubiquitous expression of Cas9 | [126] | |

| actb2:NLS-zCas9-NLS,cryaa:TagRFP | ubiquitous expression of Cas9 with red eye transgenesis marker | [127] | |

| hsp70l:LOXP-mCherry-LOXP-NLS-zCas9-NLS | Cre and heat shock controlled Cas9 expression | [127] | |

| ubb:NLS-zCas9-NLS,myl7:EGFP | ubiquitous expression of Cas9 with green heart transgenesis marker | [127] | |

| hsp70l:Cas9-IRES-EGFP,myl7:EGFP | heat shock inducible co-expression of Cas9 and EGFP with green heart transgenesis marker | [128] | |

| hsp70l:Cas9-P2A-mCherry,myl7:EGFP | heat shock inducible co-expression of Cas9 and mCherry with green heart transgenesis marker | [128] | |

| lyzC:Cas9,cryaa:GFP | Neutrophil-specific expression of Cas9 with green eye transgenesis marker | [129] | |

| hsp70l:zCas9-T2A-GFP,5x(U6:sgRNA) | heat shock inducible simultaneous expression of Cas9 and GFP, ubiquitous expression 5 guide RNAs for lineage tracing using GESTALT | [130] | |

| hsp70l:DsRed-v7,myl7:EGFP | CRISPR array, with green heart transgenesis marker for lineage tracing using GESTALT | [130] | |

| UAS:Cas9T2AGFP;U6:sgRNA1;U6:sgRNA2 | Gal4 effector line for simultaneous Cas9 and GFP expression | [131] | |

| Base editors (BE) | BE4max | cytosine BE | [132] |

| zABE7.10 | adenine BE | [133] | |

| BE, BE-VQR, dBE-VQR | cytosine BE | [134] | |

| zAncBE4max | cytosine BE | [135] | |

| BE4-Gam | cytosine BE | [97, 136] | |

| ABE8e | adenine BE | [97] | |

| ancBE4max-SpymacCas9 | cytosine BE | [136] | |

| ancBE4max | cytosine BE | [97, 132, 136] | |

| evoBE4max | cytosine BE | [97] | |

| CBE4max-SpRY | cytosine BE | [137] | |

| zAncBE4max | cytosine BE | [135] | |

| Transcriptional regulators | dCas9-KRAB | repressor | [138] |

| dCas9-VP160 | activator | [138] | |

| dCas9-Eve | repressor | [139] | |

| Lineage tracing | GESTALT (genome editing of synthetic target arrays for lineage tracing) | lineage tracing through modification of a CRISPR/Cas target array | [140] |

| scGESTALT (single-cell GESTALT) | GESTALT combined with transcriptome profiling | [130] | |

| LINNAEUS (lineage tracing by nuclease-activated editing of ubiquitous sequences) | lineage tracing through Cas9 induced INDELs in a multicopy transgene combined with transcriptome profiling | [141] | |

| ScarTrace | lineage tracing through Cas9 induced INDELs in a multicopy transgene combined with transcriptome profiling | [142] | |

| Screening tools | MIC-Drop (multiplexed intermixed CRISPR droplets) | microfluidics based generation of a library of droplets containing different RNP complexes together with DNA barcodes for injection | [86] |

One advantage of the CRISPR/Cas system over ZFNs and TALENs is the relative ease of guide RNA design and synthesis and the ability to simultaneously target multiple genes, which has been used in several high-throughput mutagenesis experiments in zebrafish [49, 79, 85, 86]. Besides generating large mutant collections, these large-scale screens have provided important information on the efficiency of INDEL induction, accessibility of target sites, and off-target effects which has aided in the development of easy-to-use guide RNA design tools (Table 2). Now, with commercially synthesized guide RNAs, Cas mRNA or protein, the CRISPR/Cas system is widely accessible in zebrafish [87, 88]. CRISPR/Cas genome editing has successfully been used to generate models of human skeletal diseases [8] and due to the high efficiency in the induction of mutations, skeletal phenotypes can readily be detected and analyzed in the F0 generation, further accelerating the discovery process [89–91].

In addition to its gene editing applications, the CRISPR/Cas system, like the Tol2 integration system, has emerged as an important tool to make targeted reporters, enabling the quick and reliable creation of new reporter lines and Cre drivers, as reviewed in detail in the next section.

2.3. Transgenesis

One main advantage of the zebrafish is the ability to perform in vivo labeling and imaging due to its small size and transparency during early developmental stages. Optically clear mutants (casper, crystal) have been generated by combining different pigment mutants to enhance in vivo imaging capabilities beyond larval stages [143, 144]. For the generation of transgenic fish, a number of different techniques have been explored for the delivery of foreign DNA, including retroviral infection, electroporation, particle bombardment and microinjection [145–149]. To date, microinjection is the most widely used technique for the generation of transgenic zebrafish due to its fast and easy application.

Initially, only circular or linearized DNA had been injected into fertilized eggs, which resulted in relatively low transgenesis rates [146, 150, 151]. Modification of the donor DNA and addition of I-SceI meganuclease or Tol2 transposase to the injection mix did increase the transgenesis rate significantly [152, 153]. Meganuclease or Tol2 recognition sequences are integrated into the donor DNA to allow linearization and integration of the DNA into the genome. To facilitate easy design of Tol2 plasmids for transgenesis, plasmid collections for modular design of donor-plasmids using the Gateway cloning system have been generated and are constantly expanded [154]. Combination of identified, tissue specific promoters with conditional expression systems and fluorophores targeted to different subcellular compartments provide limitless options for the design and generation of transgenic zebrafish for in vivo imaging and analysis as well as manipulation of gene function (Table 3) [155].

Table 3:

Subset of available transgenic tools

| Commonly used genetically encoded fluorophores | tagBFP Ex 402, Em 457 [186] mCerulean Ex 433, Em 475 [187] CFP Ex 456, Em 480 [188] mTFP1 Ex 462, Em 492 [189] EGFP Ex 488, Em 507 [190] lanYFP Ex 513, Em 524 [191] mVenus Ex 515, Em 527 [192] E2-Orange Ex 540, Em 561 [193] tdTomato Ex 554, Em 581 [194] dsRed Ex 558, Em 583 [195] mCherry Ex 587, Em 610 [194] RFP Ex 587, Em 637 [196] mKate2 Ex 588, Em 633 [197] For a more comprehensive list of available fluorophores see: https://www.fpbase.org/ [198] |

| Localization signals |

cell membrane: Lyn myristoylation and palmitoylation sequence [199–201] CAAX motif [202] nucleus: histone H2A.F/Z fusion [202] histone H2B fusion [203] hmgb1 fusion [204] SV40 nuclear localization signal (NLS) [205] nucleoplasmin NLS [206] actin cytoskeleton: Lifeact [207] microtubules: ensconsin microtubule-binding domain fusion [208] |

| Transcriptional activator systems | Gal4-UAS [209] QF-QUAS [210] KalTA4-UAS [210] |

| Conditional expression systems | Cre-loxP/lox2272/loxN [211, 212] Flp-FRT [213] Dre-Rox [214] |

| Inducible gene expression systems | Cre-ERT2 + Tamoxifen [215] LexPR + mifepristone [216] TetA-GBD + doxycycline and dexamethasone [217] TetA-EcR + doxycycline and tebufenozide [217] hsp70l promoter + heat shock [218] GV-EcR + tebufenozide [219] IQ-Switch + tebufenozide [220] GAVPO + blue light [219] |

| Cell ablation systems | Nitroreductase + metronidazole [221–223] KillerRed + intense green or white light [224] M2H37A [219] Kid + Kis anti-toxin [225] PhoCl-Bid [225] |

| Signaling pathway activity reporter systems |

Wnt signaling: TOPdGFP [226] Tcf/Lef-mini:dGFP [227] TCFsiam [228] BMP signaling: BMP-responsive element [229–232] dominant negative Bmpr1a-GFP [233] FGF signaling: dusp6:d2EGFP [234] dominant negative hsp70:dn-fgfr1 [235] Notch pathway: Tp1bglob [204] her12-Kaede [236] Hedgehog signaling: ptc1-Kaede [237] ssh-GFP [238] Erk signaling: Erk KTR [239] TGF-beta signaling: 12xSBE:EGFP [240] 12xSBE:nls-mCherry [240] |

| Genetically encoded Ca sensors | GFP-aequorin [241, 242] GCamp [243] CaMPARI [244] |

| Apoptosis marker | AnnexinV-YFP [245] NES-DEVD-mCardinal-NLS [246] genetically encoded death indicators (GEDIs) [247] |

| Autophagic flux sensor | GFP-LC3-RFP-LC3DG [248] |

| FUCCI (Fluorescent Ubiquitination-based Cell Cycle Indicator) | hGeminin [162, 249] zCdt1 [162, 249] |

| Lineage tracing tools |

Photoconvertible proteins: Dendra Ex 488, Em 505 > Ex 556, Em 575 [250] Kaede Ex 508, Em 518 > Ex 572, Em 580 [251] mEos2 Ex 506, Em 519 > Ex 573, Em 584 [252] Kikume Ex 507, Em 517 > Ex 583, Em 593 [253] Zebrabow, priZm (Lox2272-LoxP-RFP-Lox2272-CFP-LoxP-YFP) [254, 255] Palmskin (LoxN-Lox2272-LoxP-H2B-EBFP2-LoxN-palm-mCherry-Lox2272-palm-mEYFP-LoxP-palm-mCerulean) [256] FRaeppli-nls (UAS-attB-Lox2272-STOP-Lox2272-phiC31-cmlc2-mTurquoise-attP-nls-E2-Orange-attP-nls-mKate2-attP-nls-mTFP1-attpP-nls-TagBFP) [257] FRaeppli-caax (UAS-attB-Lox2272-STOP-Lox2272-phiC31-cmlc2-mTurquoise-attP-E2-Orange-CAAX-attP-mKate2-CAAX-attP-mTFP1-CAAX-attpP-TagBFP-CAAX) [257] |

| Plasmid collections |

Tol2 kit (

http://tol2kit.genetics.utah.edu

) [154]

CRISPR/Cas9 vector system for tissue-specific gene disruption [258] Addgene ( https://www.addgene.org/ ) |

The ability to target transgene expression to a specific cell type is dependent on the availability and identification of specific promoter and/or enhancer elements. Due to their capability to contain large fragments of genomic DNA (up to 300kb), modified bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) have been used to drive transgene expression in zebrafish [156, 157]. BAC modifications include the addition of I-SceI or Tol2 sites to increase transgenesis efficiency and addition of reporter genes through homologous recombination. While BACs efficiently capture most regulatory elements of a gene, their handling and modification is not trivial. The identification of smaller and easier to handle regulatory elements alleviates this problem but can be laborious and time consuming. Due to the more compact genome and conserved regulatory mechanisms, regulatory elements from another freshwater teleost, medaka (Oryzias latipes), are commonly used to drive gene expression in zebrafish [158]. One example is the use of the medaka osterix promoter to drive gene expression in zebrafish preosteoblasts and osteoblasts (Table 4) [159–163].

Table 4:

Commonly used musculoskeletal transgenic lines

| Cell type | Musculoskeletal transgenes and papers of origin | Origin of regulatory element used |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoblast lineage | (1) osx:EGFP [259] (2) osx:kaede [162] (3) osx:nuGFP [160] (4) osx:Venus-hGeminin [162] (5) osx:mCherry-zCdt1 [162] (6) osx:mCherry-NTR [163] (7) osx:H2A-mCherry [162] (8) osx:mTagBFP-2A-CreER [163] (9) entpd5a:pkRED [260] (10) runx2:eGFP [161] (11) osc:eGFP [161] (12) osc:GFP [261] (13) osx:CreERT2-P2A-mCherry [161] (14) entpd5a:YFP [262] (15) entpd5a:Citrine [263] (16) entpd5a:Kaede [264] (17) runx2:GAL4-VP16_2A-mCherry) [265] (18) osx:Lifeact-mCherry [266] (19) col10a1:mCitrine [267] (20) col10a1:GFP [268] (21) sp7:luciferase [269] |

(1) BAC containing the osterix locus (CH73–243G6) (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (13), (18), (21) 4.1 kb upstream regulatory region of medaka osterix gene (9), (14), (15), (16) BAC containing the entpd5 locus (10), (17) 557bp enhancer from the last intron of human RUNX2 fused to the mouse cFos minimal promoter (11) 3.7kb upstream promoter sequence of medaka osteocalcin (12) 3.5kb upstream regulatory region of medaka osteocalcin [270] (19) BAC containing the col10a1 locus (20) 2.2 kb upstream promoter of zebrafish col10a1 |

| Cartilaginous cells | (1) col2a1a:eGFP [271] (2) col2a1a:CreERT2 [272] (3) col9a2:GFPCaaX [273] (4) col2a1a:mCherry [267] |

(1), (2) R2 element upstream the transcription initiation site (358bp enhancer) (3) 2048bp of zebrafish col9a2 promoter upstream of the start of translation (4) BAC containing the col2a1a locus |

| Tendon/ligament cells | (1) scxa:mcherry [274] (2) scxa:gal4-vp16 [275] (3) col1a2:loxP-mCherry-NTR [276] (4) nkx3.1:gal4-vp16 [277] (5) col1a2:Gal4-VP16 [277] (6) col1a2:GFP [277] |

(1), (2) BAC CH211 251g8 containing the entire scxa genomic locus (3), (5), (6) BAC CH211–122K13 containing col1a2 locus (4) BAC zC21G15 from the CHORI-211 library containing the nkx3.1 locus |

| Joint cells | (1) irx7:GFP [278] (2) trps1:GFP [279] |

(1), (2) SAGp11A, Tol2-mediated gene trap insertions into the endogenous locus [61] |

| Osteoclast | (1) ctsk:FRT-dsRed-FRT-Cre [280] (2) trap:GFP-CAAX [266] (3) ctsk:EGFP [281] (4) ctsk:Citrine [263] |

(1), (3) 3kb upstream regulatory region of medaka cathepsin K gene (2) 6kb upstream regulatory region of the zebrafish trap (acp5a) gene (4) BAC containing the cathepsin K locus |

| Neural crest-derived skeletal cells | (1) sox10:ERT2-Cre [282] (2) sox10:GFP [283] (3) sox10:CreERT2 [272] (4) sox10:dsRED [284] |

(1) 4.9kb of zebrafish sox10 promoter sequence upstream of the start of translation (2) 4725bp of zebrafish sox10 promoter upstream of the start of translation (3), (4) 4.9kb of zebrafish sox10 promoter sequence upstream of the start of translation |

While meganuclease and transposase based transgenesis methods are very efficient, they often lead to the integration of multiple copies of the transgene and integration site-specific effects on expression [164, 165]. This can be avoided through integration of the expression plasmid into a predefined landing site using the phiC31 integrase system [166]. Alternatively, to circumvent the need for identification of regulatory elements, integration of expression constructs can now be targeted to specific locations in the genome to capture the surrounding regulatory region to drive gene expression. Here ZFNs, TALENs or CRISPR/Cas are being used to create double strand breaks at the desired integration site and co-injected donor DNA is integrated into the cut site. A large number of different knock-in strategies are being explored and show different levels of efficiency, often leading to imprecise integration into the genome [71, 167, 168]. For target integration using homology directed repair, a number of different template designs have been used. Designs differ in the length of the homology arms as well as the type of DNA template used (single stranded oligonucleotides, double stranded linear, in vivo linearized or circular DNA) [169–177]. In addition to different template designs, simultaneous inhibition of the non-homologous end joining DNA repair pathway has been explored to improve precise integration [178–180].

However, not all transgenesis strategies require homology arms, and donor DNA without any homology can successfully be integrated through homology-independent DNA repair [181, 182]. DNA constructs similar to those used in enhancer, gene and protein trap screens can be used to generate reporter lines for genes of interest.

In the skeletal field, live imaging and manipulation of transgenic zebrafish has been used to capture crucial events during development and regeneration of tendon/ligament, bone and cartilage and is discussed in the sections below. The zebrafish is also an excellent vertebrate model for high-throughput chemical screening using whole organisms. Chemical libraries are commercially available or can be accessed through screening centers at some academic institutions or commercially. Many libraries are assembled to contain known biologically active compounds, for which there is some information about the molecular target, and more specific chemical libraries targeting particular molecular processes, such as kinase or chromatin targeting libraries, can be selected. Although some chemical screens were performed using morphology or staining methods as assays, transgenic fish have enabled automation of the screening platform, enabling larger scale screening efforts [183–185]. These studies highlight the major opportunities available to use chemical screens to interrogate skeletal development and repair, which will serve as an important platform to inform both basic and translational research. Table 3 summarizes available expression and cell labeling systems and musculoskeletal system specific transgenic lines are listed in Table 4.

3. The Zebrafish Skeleton

The adult zebrafish skeleton can be divided into the endoskeleton, consisting of the cranial, axial and appendicular skeleton and the dermoskeleton, including scales, teeth, and fin rays. Despite a divergence in the number of skeletal elements and the shape of the skeleton in zebrafish, decades of research have demonstrated the deeply conserved mechanisms that control skeletal development in vertebrates. Like mice and humans, the adult zebrafish skeleton is composed of bones joined by fibrous or cartilaginous joints, ligaments that connect neighboring bones, and tendons that attach muscles to bones. While the craniofacial skeleton derives from both neural crest and mesoderm, the axial skeleton arises from mesoderm.

Despite some differences from their mammalian counterparts, the zebrafish skeletal system provides powerful models to understand skeletal development and model human disease. In this section, we summarize the basic building blocks of the zebrafish skeleton and highlight some of the studies that illustrate the conserved genetic requirements for skeletal system development. As a detailed discussion of specific skeletal elements, like the vertebral column or the paired pectoral fins, is outside the scope of this review, we refer the reader to several excellent reviews [4, 285–290]. These reviews carefully summarize the homology of specific skeletal elements to their mammalian counterparts and highlight discoveries and recent advances made using zebrafish models. Likewise, although there is a wealth of skeletal research using the other teleost model, medaka, and most of the methods for genetic modification described also work in this model, our review will specifically focus on studies in the zebrafish. We refer interested readers to recent work and reviews describing medaka as a model of human skeletal diseases and illustrating how innovative imaging methods can be used to gain new insight into skeletal biology processes such as bone remodeling [7, 291–293]

3.1. Cartilage

The earliest chondrocytes in the zebrafish skeleton emerge from neural crest cells within the craniofacial skeleton by 56 hours post fertilization (hpf) [294]. By 72hpf, the craniofacial cartilaginous template is fully formed in the craniofacial skeleton, robustly expresses classic chondrocyte markers like col2a1a [271, 295], and can be readily detected by Alcian blue staining of glycosaminoglycans and glycoproteins (Figure 1A). These cartilages are typically 1–3 chondrocyte layers in thickness, with perichondrium surrounding the cartilage. In contrast to cartilages found in the craniofacial skeleton, the cartilages in the axial skeleton, including those along the vertebrae and at the base of fins, emerge later in larval development [296]. Along vertebrae 1–5, basidorsal cartilages form that will later become the neural arches [296]. However, unlike mammalian vertebral bodies which form through endochondral ossification and are patterned following somite boundaries, zebrafish vertebrae are pre-patterned by notochordal signals that induce ossification of notochord sheath cells (chordacentra). These provide a template for autocentrum formation by sclerotome derived osteoblasts and only the patterning of the hemal and neural arches is somite dependent [297].

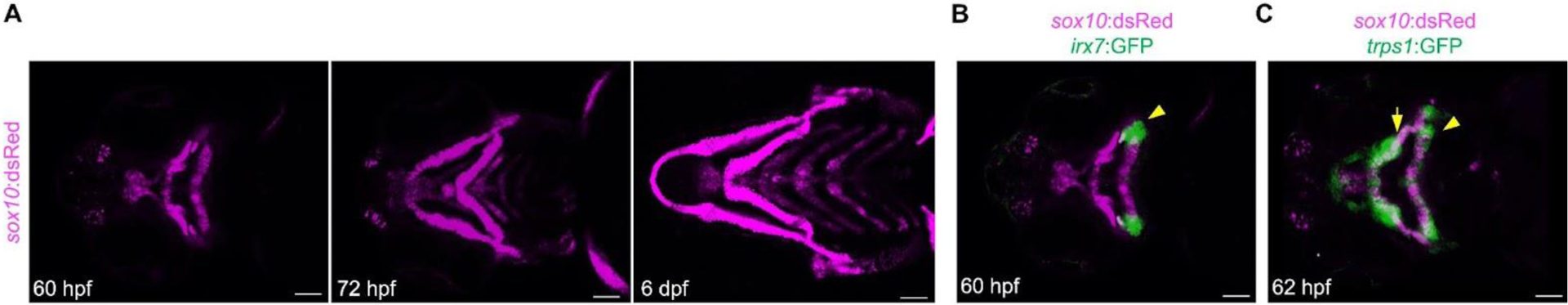

Figure 1.

Cartilage and joint development in zebrafish. (A) A time series of cartilage development in the zebrafish lower jaw skeleton using the sox10:dsRed reporter to label chondrocytes. Cartilage formation is clearly apparent within the craniofacial skeleton at 60 hpf. (B) The hyoid joint (arrowhead) that connects the hyomandibular and ceratohyal cartilage expresses irx7:GFP. (C) trps1:GFP is enriched at joints in the craniofacial skeleton, including the hyoid joints (arrowhead) and jaw joints (arrows). Scale bars, 50 μm.

The mechanisms that govern cartilage specification, differentiation, and growth have been extensively researched using zebrafish, especially within the craniofacial skeleton [298–300]. Chondrocytes in the craniofacial skeleton derive from barx1+ condensations that express sox9 [294, 301, 302], like the gene expression patterns characterized in mice [303, 304]. Due to the teleost-specific whole genome duplication, sox9 in zebrafish, like many other genes, has two orthologs, sox9a and sox9b [2, 240, 305, 306]. While one copy of 50–90% of genes duplicated through a whole genome duplication tends to mutate to a pseudogene, the genes maintained as functional pairs provide unique advantages for the study of gene function [307]. Gene pairs evolve and one gene copy can develop new functions (neofunctionalization) or the expression domains or function of the original gene can be subdivided between pairs (subfunctionalization) [308]. The subfunctionalization of sox9 for example, allows for the analysis of aspects of sox9 function not possible in mice where haploinsufficiency of sox9 leads to early lethality [309]. Like in mouse models [310, 311], zebrafish chondrocyte differentiation and maturation rely on Sox transcription factors. Mutant alleles for sox9a were independently generated using ENU (jeftw37) and retroviral (hi1134) mutagenesis, and mutant fish displayed severely reduced and absent cartilages throughout the craniofacial skeleton and fins [53, 312, 313]. In contrast, sox9b (b971), mutated using gamma radiation, is predominately required in the lower jaw cartilages, with many neurocranium and fin cartilages intact. Simultaneous deletion of sox9a and sox9b eliminates all cartilages throughout the skeleton, highlighting the conserved requirement for the Sox family to properly establish cartilages in vertebrates [314].

3.2. Bone

Bone formation takes various forms in the zebrafish skeleton, and includes intramembranous, perichondral, and endochondral ossification. The earliest bones develop via intramembranous ossification, directly differentiating into osteoblasts from mesenchymal progenitors, independent of cartilage formation [315]. A mineralized opercle is readily detectable by 3 days post fertilization (dpf) [316]. Thereafter, dermal bones will continuously emerge throughout larval and juvenile development within both the craniofacial and axial skeletons (Figure 2A) [296, 317]. Perichondral ossification is apparent around cartilaginous elements between 5–7dpf, particularly around the developing Meckel’s and ceratohyal cartilages [316], while endochondral ossification arises later at juvenile stages of development [272, 318]. Like endochondral bones in other vertebrates, endochondral bones in the zebrafish contain growth plates composed of proliferative and hypertrophic chondrocytes, are surrounded by perichondrium that forms cortical bone, and have a marrow space [272, 318]. However, unlike mammals, the endochondral marrow space does not contain hematopoietic tissue, but instead contains adipocytes distributed within the marrow cavity, as hematopoiesis occurs in the zebrafish head kidney [272, 319].

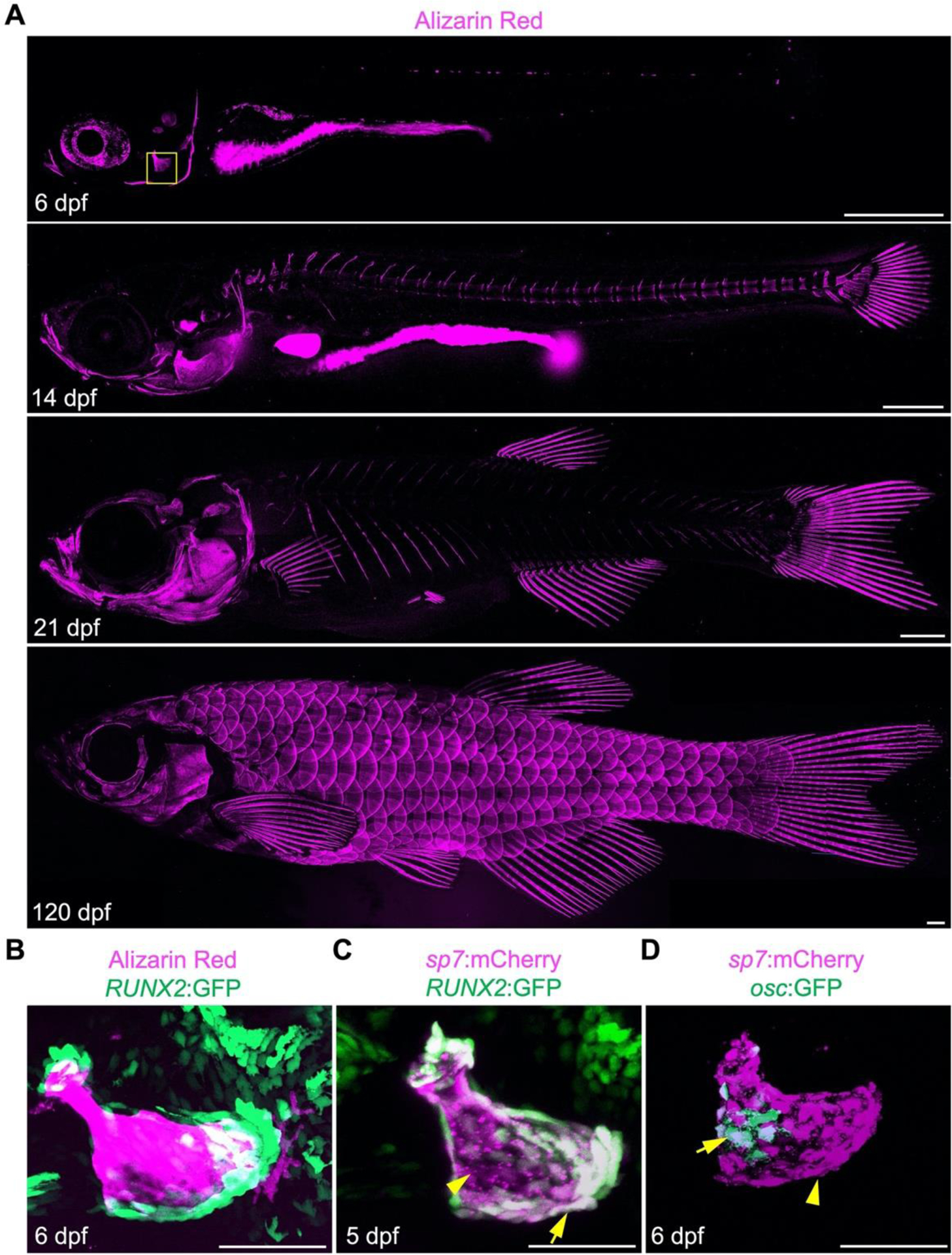

Figure 2.

Bone development in zebrafish. (A) Developmental series of alizarin red stained zebrafish from larval, juvenile and adult stages. Mineralized bones are detected earliest in the craniofacial skeleton and later appear within the axial and fin skeleton. Scales emerge later in development. Scale bars, 500 μm. (B-D) Osteogenesis in the larval opercula (boxed in A at 6 dpf). (B) RUNX2:GFP preosteoblasts are enriched at the tips of the mineralized larval opercular. (C) sp7:mCherry high cells are enriched along the surface of the opercular, while sp7:mCherry; RUNX2:GFP pre-osteoblast are abundant at the bone tips. (D) osc:GFP+ osteoblasts are restricted to the most mature osteoblasts away from the edges of the opercule. Scale bars for B-D, 50 μm.

Generally, the adult zebrafish skeleton is composed of four major classes of bone: compact bone, spongy bone, tubular bone and chondroid bone [318]. These bones exist as both cellular bone and acellular bone, with many dermal bones (like the frontal and parietal bones) lacking the many embedded osteocytes that are pervasive in mouse and human bone. Across all bones, osteoblast differentiation takes a similar path as in mice and humans, with osteoblasts expressing runx2a/b [320], osterix (osx/sp7), and eventually osteonectin (osn), osteocalcin (bglap) and col10a1a (Figure 2B–D) [315]. Like in mice [321], mutants for sp7 (hu2790), isolated through TILLING, develop skeletal defects driven by impaired osteoblast differentiation [322, 323]. Zebrafish models also uncovered mechanisms of bone mineralization. The characterization and mapping of two mutants identified in a forward genetic screen led to the discovery of reciprocal roles for enpp1 and entpd5 for phosphate/pyrophosphate regulation and bone mineralization, with enpp1 (hu4581) mutants displaying ectopic mineralization and entpd5a (h3718, hu5310) mutants lacking mineralized bone [262].

As in mammals, normal development, homeostasis and repair of the zebrafish skeleton is dependent on the presence and function of osteoclasts. Osteoclasts are hematopoietic cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage that possess the ability to not only resorb bone, but also to regulate bone formation [324]. Osteoclasts can be identified by the expression and activity of the lysosomal enzyme tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), encoded by the acp5 gene. Detailed histological analysis in combination with TRAP staining showed that bone resorption predominantly occurs through mononucleated osteoclasts in juvenile zebrafish, while predominantly multinucleated cells are found in adults [325]. Analysis of TRAP expression in the zebrafish lower jaw captured TRAP+ mononucleated osteoclasts at 20 dpf, and multinucleated osteoclasts by 40 dpf, although the emergence of osteoclast types is likely site specific [319, 325]. This presence of mono- and multinucleated osteoclasts was confirmed by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) of cells isolated from ctsk:DsRed transgenic fish, taking advantage of the unique possibility in zebrafish to isolate primary osteoclasts from entire fish [280]. In both mammals and zebrafish, the ETS-domain transcription factor Pu.1 as well as signaling through colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (Csf1r) play critical roles in myelopoiesis. Analysis of ENU generated mutants in pu.1 (G242D), as well as csf1ra (j4e1, j4blue), showed a significant decrease in myeloid cells and therewith osteoclasts [281, 326]. Double mutant analysis revealed a predominant function of pu.1 in osteoclastogenesis, while csf1ra function is important during osteoclast maturation. In mammals, loss of osteoclast function leads to osteopetrosis, however the consequences of loss of Csf1r function to the zebrafish skeleton are milder and can be detected as shape changes of vertebral bodies, hemal and neural arches, as well as an increase in bone mineral density [280, 281, 327]. While a lot of research in zebrafish has focused on defining the different stages and sites of hematopoiesis, as well as defining developmental trajectories of hematopoietic cell lineages, the precise origins of osteoclasts in zebrafish remain an active field of investigation [328–331].

3.3. Joints

Articulations between neighboring bones play critical roles in modulating growth, movement and flexibility. Like in other vertebrate models, the zebrafish contains a variety of joint types, including fibrous joints and cartilaginous joints. Fibrous joints typically form between two dermal bones in the craniofacial skeleton. One example are the zebrafish cranial sutures, which display conserved requirements during skull development as zebrafish carrying mutations in cyp26b1 (t24295, generated through ENU mutagenesis) or combinatorial deletions in twist1b (el570) and tcf12 (el548), both generated using TALENS, fail to form select sets of cranial sutures, similar to mice and humans [160, 332, 333]. Cartilaginous joint specification has been extensively researched in zebrafish, with several mutant lines or morpholino treated embryos leading to the loss or gain of cartilaginous joints, including the Iroquois homeobox factor family, nkx3.2, and barx1 [278, 279, 334–336] and transgenic reporters to label developing joints (Figure 1B–C). Furthermore, recent work has demonstrated the presence of synovial joints in the zebrafish jaw and fins and a conserved requirement for Prg4 (also known as Lubricin), demonstrated by deleting prg4b (el594) using TALENS to reveal arthritis phenotypes in mutants [337]. Another recent study identified a highly conserved nkx3.2 enhancer that is essential for jaw joint formation in zebrafish [338]. These findings highlight the zebrafish as a powerful system to interrogate joint degenerative and developmental diseases.

3.4. Tendons and Ligaments

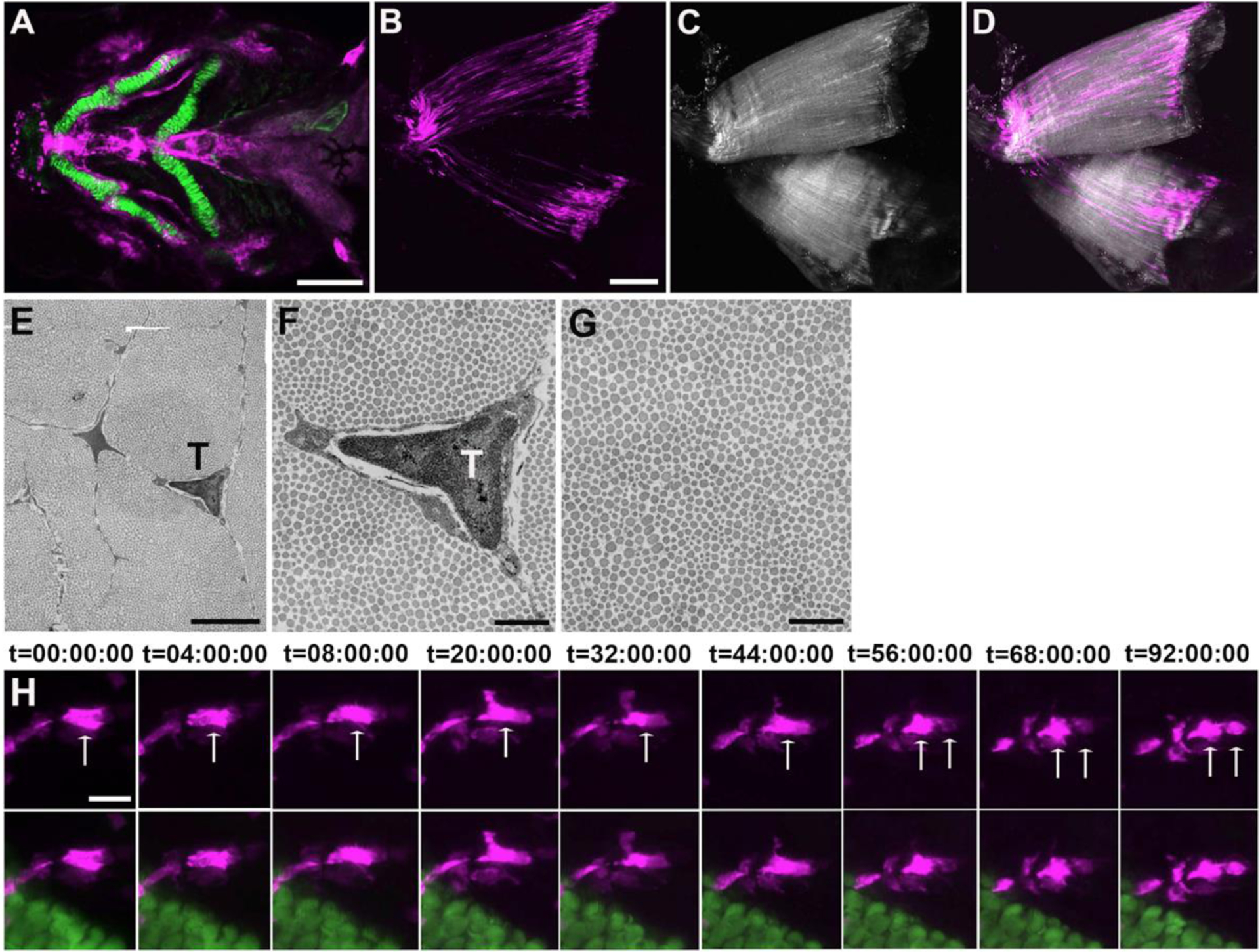

Conserved with that of chick and mouse [339, 340], zebrafish tendon development is marked by early expression of scleraxis a (scxa) (Figure 3A), a transcription factor found in tendon cells at all stages, in the cranial regions after 40 hpf and the axial regions after 30 hpf [274, 275, 277, 341–343]. Around 60 hpf, tendon cells express the matrix genes, tenomodulin (tnmd), col1a1a, col1a1b, and col1a2, signifying their differentiation and maturation (Figure 3B–G) [341]. Zebrafish tendon cells also express a second scleraxis paralog, scleraxis b (scxb) [341, 343]. Generally, the genes expressed by tendons, including scxa/b, also label ligaments, making it difficult to molecularly distinguish them although they have unique characteristics at the structural and functional level and can readily be identified based on their attachment points [341, 344]. In zebrafish, the majority of cranial tendons originate from the cranial neural crest [341, 345], with the exception of the sternohyoideus tendon which is contributed by two germ layers, the neural crest and the mesoderm [275]. Zebrafish pectoral fin tendons are derived from lateral plate mesoderm [275, 285] and axial tendons arise from the sclerotome compartment in the somites [277].

Figure 3.

Zebrafish craniofacial tendon and tendon cell division during tendon regeneration. (A) A double transgenic line shows scxa:mcherry; col2a1a:eGFP expression at 3dpf. Scale bar, 50μm; (B-D) Multiphoton images of sternohyoideus tendon at 180 dpf show scxa:gal4-vp16; uas:epNTR-RFP+ tendon cells (B, D) and second harmonic generation (SHG) of collagen fibril (C, D). Scale bar, 100μm; (E) Ultrastructural examination of tendon cells and collagen fibrils by TEM. Scale bar, 2μm; (F, G) Magnified examination of tendon cells and collagen fibrils in (E). Scale bar, 0.5μm; (H) Time lapse imaging of ceratohyal cartilage region shows tendon cell division during tendon regeneration. scxa:gal4-vp16; uas:epNTR-RFP+ labels tendon cells (white arrows indicate a cell undergoing division) and col2a1a:eGFP labels ceratohyal cartilage. Scale bar, 25μm. In (H), tendon cells were ablated at 3–5 dpf, t=00:00:00 was immediately after the cell ablation. T, tendon cell. Images A-D, H, anterior to the left. Images E-G, transverse section.

Zebrafish tendons rely on conserved regulatory programs found in mice and humans. Similar to Scx mutant mice [346], knockout of scxa (kg170) or scxa and scxb (kg107) together using CRISPR/Cas in zebrafish resulted in decreased tnmd expression. Notably, the zebrafish mutants also had defects in cranial tendon and ligament development and differentiation, resulting in detached muscle fibers, abnormal swimming behavior, and reduced numbers of intermuscular bones [343, 347]. Proper matrix assembly is important for the formation and integrity of the tendon attachment as morpholino knock-down of thrombospondin 4b (tsp4b) resulted in muscle detachment [348]. Consistent with research in mice [349] and chicken [350], studies in zebrafish have shown that muscles are required for axial tendon induction but dispensable for induction of cranial and pectoral fin tendon progenitors. However, muscles are necessary for the maintenance of scxa expression in the cranial and pectoral fin tendons at later stages [341]. In turn, problems with the myotendinous matrix can affect the muscle, resulting in movement impairment and muscle weakness [351]. In contrast, cartilage does not appear to be required for the induction of tendon progenitors in the cranial, pectoral fin and axial regions [341]. Several pathways have conserved requirements for tendon development in zebrafish, including the Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGF) [341] and Transforming Growth Factors β (TGF-β) pathways [341, 352]. More recently, the zebrafish model has been used to identify novel signaling pathways regulating tendon cell formation, such as Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) [275], Hedgehog [277], and mevalonate [277] pathways. Additionally, a recent study showed mechanical force regulates the cellular projections from tendon cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) production [352]. These studies highlight the conserved requirement of tendon formation across development, as the number of studies using zebrafish as models for tendon biology grow.

3.5. Teeth

Zebrafish have pharyngeal teeth located at the fifth ceratobranchial bone [353]. These teeth have many morphological similarities to vertebrate teeth, including the presence of enameloid, dentin, pulp, and odontoblasts. They are shed and replaced throughout the animal’s lifespan, making them a compelling model for tooth regeneration [353]. Using TRAP staining and ctsk:DsRed transgenic lines, large numbers of osteoclasts can be detected at the base of teeth, where resorption of attachment bone is required for tooth replacement. Consequently, loss of osteoclasts in csf1ra/b double mutants (mh5, and mh108, mh112) leads to an increase in tooth number due to tooth retention [280, 319]. The signaling pathways involved in the development and mineralization of zebrafish teeth overlap significantly with vertebrates [354–357], and several genes have been shown to be essential for tooth formation, including ext2 [358] and the foxf family [300]. Zebrafish teeth are a largely untapped model for biomineralization, tooth development and regeneration and future research is warranted to expand the mechanisms of tooth biology using the zebrafish model.

3.6. Scales

Although absent in mammalian and avian models of skeletal development, zebrafish scales have proven to be a rich resource to understand bone biology. Scales are ectoderm-derived calcified organs that cover the body. The external side of each individual scale has four discrete zones, all of which contain mineralized circuli of various stages. Dynamic mineral labeling using calcein and alizarin red show that one circulus is added to each scale per week in growing young adult fish, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity is seen in differentiating osteoblasts along the margins of new circuli, but not old circuli [359]. Like other bones, scales are remodeled by osteoclasts and are often utilized as a proxy to assess osteoclast number and activity in mutant models, using TRAP staining for osteoclasts and von Kossa staining to detect mineralized tissue and assess resorptive activity [280, 360–363]. For example, analysis of scales from csf1ra/b double mutants did show a complete loss of TRAP staining and no signs of bone resorption, confirming the importance of Csf1r function for osteoclastogenesis [280]. Recent transcriptional analysis of CRISPR generated low-density liporpotein receptor-related 5 (lrp5) mutants showed an enrichment in genes involved in both osteoblast signaling and function and osteoclast differentiation, suggesting a novel role for Lrp5 during osteoclastogenesis. Detailed analysis of osteoclast behavior in mutant scales supported a role for Lrp5 in osteoclastogenesis as mutants displayed an increase in TRAP staining and an increase in resorbed area, suggesting an increase in osteoclast number and/or activity [363].

Zebrafish scales can be easily harvested from adult zebrafish and cultured for up to 72 hours in vitro [359]. Several studies have utilized ex-vivo scale culture systems to uncover basic interactions between osteoblasts and osteoclasts, to model skeletal changes in pathological conditions, and to perform chemical screens to identify novel regulators of osteoblast and osteoclast activity [364–366]. For example, ontogenetic scales from sp7:luciferase transgenic fish have been cultured in osteogenic media to successfully screen for novel drugs with osteogenic potential [269]. These tissue explants also show endogenous interactions between osteoblasts and osteoclasts, something not attainable in monolayer cell cultures. Thus, the zebrafish model provides novel mechanisms to understand skeletal development through the utility of structures absent from alternative models.

4. Regeneration in the zebrafish skeleton

Zebrafish have profound regenerative capacity. Numerous examples show that tissue repair in zebrafish exceeds its mammalian counterparts [367, 368]. The zebrafish is also one of the earliest model organisms used to study musculoskeletal regeneration [369]. Bone regeneration employs multiple distinct cellular methods based on the anatomical location and the extent of injury. Among the diverse routes towards regeneration, fin amputation is the only injury that results in a classical blastema, which is evolutionarily conserved with axolotl [370]. However, fin crush injuries undergo intramembranous repair, and mandible resection heals by endochondral ossification. This diversity of regenerative programs means that an injury can be selected to model a specific mammalian repair mechanism or to examine mechanisms distinct to the zebrafish. The use of transgenic lines together with in vivo imaging allows for the observation of cell behavior during the regeneration process in real time.

The different regeneration models (Figure 4) will be further elaborated in the following section. In addition, this section will also highlight the regenerative strategies for the skeletal components that support bone, including cartilage and tendons/ligaments.

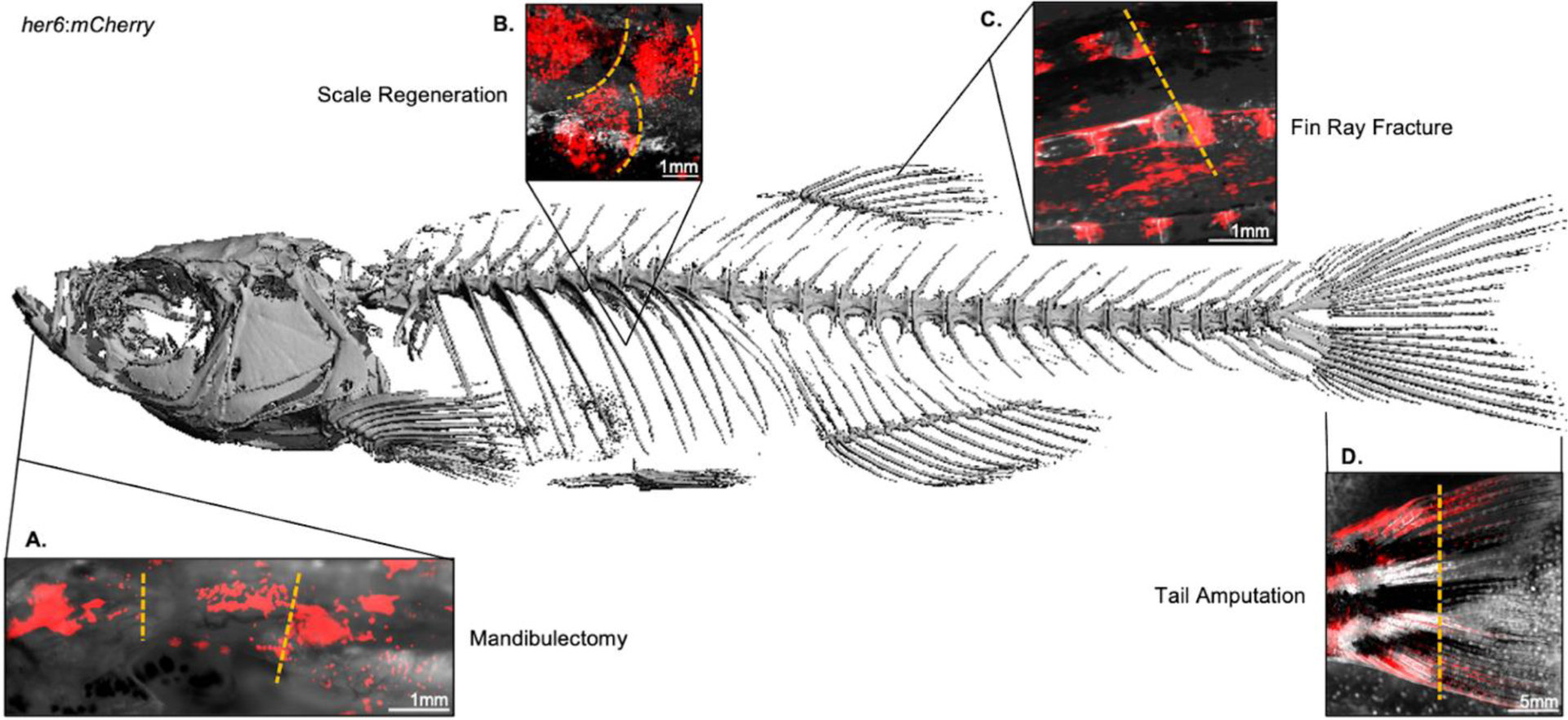

Figure 4.

Diverse regenerative processes activate notch signaling in the zebrafish skeleton. Micro-computed tomography reconstruction of the adult zebrafish skeleton, obtained in a Scanco μCT40 at 12μm^3 resolution with a lower threshold of 250 mgHA/ccm. Microscopy of zebrafish expressing the Notch signaling reporter her6:mCherry demonstrates ability to perform longitudinal intravital imaging of fluorescent transgenes under anesthesia using a stereomicroscopy. Representative images are shown 10 days following each of the following model injuries: (A) unilateral mandibulectomy; (B) scale plucking; (C) dorsal fin ray fracture; and (D) partial tail amputation, which were performed in different animals. Yellow dashed lines in A-D represent approximate injury margins.

4.1. Fin Amputation

Epimorphosis is a process by which complex structures are regenerated by a highly organized cluster of proliferative, undifferentiated cells called a blastema. Amputation of the zebrafish caudal fin is a classic example of this phenomenon, and has been known to science for more than two centuries [369]. The advent of transgenesis has greatly accelerated our understanding of this process. There is an immense body of literature describing caudal fin regeneration [371], and this section will summarize in brief and highlight specific emerging transgenic techniques that have contributed to the field.

The caudal fin faithfully regenerates its native structure and function following serial amputations [372]. This remarkable epimorphic regeneration process is believed to largely mirror both the cell types and signaling mechanisms present during development [373]. Within 24 hours of amputation, small clusters of mesenchyme known as blastemas aggregate at the distal ray stumps enveloped by a wound epithelium. Outgrowth of bone and supporting tissues then occurs over a period of weeks until new rays achieve their original sizes and organization [371]. Regenerative osteoblasts derive from multiple proliferative populations including cells derived from intra-ray mesenchyme [163], and to a lesser extent, dedifferentiated osteoblasts activated from the remaining bone tissue [161, 374]. With the multitude of available transgenic lines and lineage tracing techniques, these processes can easily be traced and visualized by time lapse imaging in vivo in the easily accessible and relatively thin (less than 200um thick) zebrafish caudal fin. We refer readers to existing reviews that describe this process in further cellular detail [374, 375].

Signaling cascades important for regenerative outgrowth following caudal fin amputation include Notch [376], FGF [377], TGFβ [378], Wnt [379], Hedgehog [380], and numerous others. Much of this work has been performed using traditional gene knockouts and reporters, with a more recent trend towards incorporating transcriptomics, epigenetic profiling, and inducible genetic approaches. One example is identification of a tissue-specific leptin b-linked enhancer element as essential to the regenerative response of intraray mesenchyme [381]. Live clonal analysis using tph1b:CreER; priZm animals indicate these activated mesenchymal cells exhibit significant positional and functional heterogeneity that is acquired within the first 2–3 days post-amputation [382]. The transient wound epidermis has also been tracked using fn1b:creERt2-mediated fate mapping [383], and found to orchestrate early osteoblast patterning [384].

4.2. Fin Ray Fracture

Crush injury to the caudal fin hemirays, including intra-ray arteries and nerve fibers, produces a callus that is reminiscent of those seen in mammalian fractures [385]. The gene expression profile of the callus shares many markers in common with caudal fin amputation including msxb (early blastema marker), osterix, collagen 1, osteonectin, osteopontin and Tenascin C. Similar to mammalian fracture repair, the fin ray fracture involves the FGF, retinoic acid, and Wnt signaling pathways [264]. Osteocalcin:GFP and runx2:GFP fish were leveraged to show that mature fin ray osteoblasts decreased osteocalcin expression and increased runx2 expression around fracture sites, suggesting dedifferentiation of osteoblasts in this model. Entpd5:Kaede and osterix:CreERT2-p2a-mCherry ; hsp70l:loxP-DsRed2-loxP-nlsEGFP transgenic animals have shown that dedifferentiated osteoblasts migrate towards the fracture site from adjacent fin ray segments, proliferate and then mineralize the injury site [264].

The fin ray fracture has also been used to study fracture healing in a zebrafish osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) disease model, which showed that similar to human patients, OI zebrafish suffered non-union in about 30% of fractures, whereas non-union essentially never occurs in wild type animals. Bisphosphonates reduced osteoclast activity and therefore healing in wild-type animals, while reducing incidence of spontaneous fractures in the OI fish. Additionally, bacterial infection by S. aureus was shown to impair fracture healing in zebrafish using this model [386]. Furthermore, the fin ray fracture model has been used to show that osteocytes are responsible for the improved fracture healing observed with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy [387], and wnt16 mutant (bi667 and bi451) zebrafish showed increased vulnerability to spontaneous fractures and delayed osteoblast recruitment and bone mineralization during fracture healing [388]. The fin ray fracture is an accessible and clinically relevant model of intramembranous regeneration, with increased reliance on osteoblast differentiation versus what is currently understood in mammals.

4.3. Calvarial Trepanation

Surgical defects of the cranial vault—trepanation of the frontal and/or parietal bones—are commonly used to model intramembranous regeneration in rodents. These models have been adapted to zebrafish; a 0.5 mm defect regenerates in 14 days [264]. Reporter animals including runx2:GFP, sp7:GFP, and bglap:GFP bred on a casper double-mutant background (lacking pigment) have been used for serial intravital imaging of the differentiation process [264]. This group used sp7:CreERT2-mediated lineage tracing to reveal contribution of resident calvarial osteoblasts to the repair process. Intravital optical coherence tomography has also been recently applied to monitor small molecule-induced changes to defect regeneration [389].

4.4. Mandibulectomy

The mandible is developmentally derived from neural crest cells of the first pharyngeal arch, and ossification occurs around a central cartilage template (Meckel’s cartilage) that persists through adulthood [390]. Mandibulectomy is the only endochondral bone repair model in zebrafish. There are two approaches: bilateral amputation of the distal aspect including the mandibular symphysis [391], and unilateral resection of the mandibular body including the Meckel’s cartilage [392].

Amputation of the distal 1/3 of the mandible results in endochondral repair that fully ossifies and does not restore the cartilaginous mandibular symphysis [391]. RNA sequencing of regenerating tissue at day 4 revealed upregulation of numerous genes associated with neural crest cells and their differentiating progeny. Using a follow-up knockdown approach, foxi1 was identified as regulating sox9a+ progenitor cells adjacent to the Meckel’s cartilage that are required for bone outgrowth from the amputated stumps [393]. The bone formed in this model is believed to primarily derive from mesenchymal cells of the mandible located adjacent to the injury. Some genes representative of epimorphic regeneration of the fin, such as msxb, are expressed in this model, but the primary mechanism is believed to be endochondral regeneration [394]. Interestingly, this process is not dependent on Wnt signaling [394].

Regenerative cartilage formed after resection of the mandibular body is continuous with Meckel’s cartilage, if any remains following the procedure [394], yet the regeneration process is distinct from developmental endochondral ossification [392]. The repair cartilage cells, lineage-traced with col2a1a:GFP, stain for osteoblast-specific spp1 and embed themselves in alizarin-labeled new bone, and this process requires ihha signaling [392]. Zebrafish mandible regeneration is therefore believed to incorporate highly regenerative hybrid cartilage-bone cells with enhanced plasticity relative to most mammalian models [395]. A her6:mCherry transgenic reporter shows that Notch signaling is active during the early phases of regeneration, and regenerate bone volume is proportional to early Notch signaling levels [396] (Figure 4). hsp70l:Gal4; UAS:myc-Notch1a-intra mediated overexpression of the Notch1a receptor’s intracellular domain accelerates the conversion of cartilage to bone [396].

4.5. Scale Regeneration

Adult zebrafish scales regenerate following loss. RNA-seq of both ontogenetic and regenerating scales shows conservation of osteogenesis programs between zebrafish and mammals [397]. A prednisolone-induced osteoporosis model was found to impact scale regeneration by inhibiting the size of the new scale and increasing osteoclast activity [361]. Osteoblast-associated genes like sp7 and runx2a are expressed very early in scale regeneration, and Hh signals shha, ihha, and ptch1 are all expressed by day 2 of scale regeneration. Small-molecule inhibition of Hh signaling results in a reduction in the number of central and marginal osteoblasts by impacting the recruitment of precursors and osteoblast differentiation [398]. Using osx:H2A-mCherry fish, osteoblasts can be seen as early as 24 hours post scale plucking (hpp). Genetic ablation of homeostatic osteoblasts using osx:mCherry-NTR animals shows similar rates of scale regeneration as control animals, indicating de novo osteoblasts contribute to scale regeneration. This was confirmed by using osx:kaede photoconvertible animals, which shows that new osteoblasts do not result from proliferation of pre-injury osteoblast populations. osx:Venus-hGeminin and osx:mCherry-zCdt1 animals enable discrimination between cell cycle phases, which helped determine the proliferation patterns of osteoblasts in the regenerating scales. fgf20a:EGFP transgenic fish have also been used to show fgf20a is expressed in the osteoblasts of regenerating scales, and hsp70l:dnfgfr1-GFP animals have been used to induce heat-shock controlled inhibition of fgf receptors, which resulted in decreased scale regeneration. The poor regeneration in these animals was found to result from decreased proliferation of osteoblasts [162].

Erk activity, dependent on Fgf receptors and MAPKK in scale osteoblasts, is activated in repeated waves that travel from the center to the periphery of regenerating scales once every two days. Osteoblast growth, and therefore scale growth, correlates with the speed and number of Erk waves [239]. To investigate the intercellular interaction between osteoblasts and osteoclasts during osteoclast differentiation, trap:GFP; osterix:mCherry double-transgenic fish were generated to visualize both osteoclasts and osteoblasts in a fracture scale model in zebrafish. Flow cytometry sorting followed by confocal microscopy revealed that most trap:GFP+ cells had mCherry+ particles in their cytoplasm, which were thought to be osteoblast-derived extracellular vesicles. This was confirmed after transplantation of kidney marrow cells from trap:GFP fish into irradiated osterix:mCherry fish resulted in GFP+/mCherry+ double positive cells at fracture sites, as well as after live imaging of fractured scales showed osteoclasts actively interacting with osteoblasts by engulfing their mCherry+ particles. These osteoblast-derived extracellular vesicles were determined to promote osteoclast differentiation and fusion in cell culture [266].

4.6. Tendon and ligament regeneration

Over 14 million tendon injuries are reported in the United States each year [399], yet their lasting repair remains a significant clinical challenge. Most studies of tendon injury mechanisms employ mammalian models such as mouse and rat, which are characterized by non-regenerative healing through scar formation. These studies have explored the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying mammalian tendon injury and repair and have improved our understanding of the cell types and pathways involved in the repair process [400–405]. Neonatal mice, which have been found to undergo regenerative tendon healing, have been used to dissect the cellular, mechanical, and structural mechanisms and have shown that Scx-lineage cells contribute to functional repair [403, 406]. The zebrafish provides a new system to study tendon and ligament regeneration; however, the model is in its infancy and much work is needed to fully understand the mechanisms guiding tendon and ligament regeneration. Recently, genetic tools were developed to ablate scxa+ tendon cells in zebrafish and it was discovered that the larvae were able to fully regenerate their tendon composition and pattern (Figure 3H) [275, 407]. Using live imaging and lineage tracing, they established that the new cells were recruited from sox10+ perichondral cells and nkx2.5+ cells surrounding the muscle and identified BMP signaling as an essential regulator of tendon regeneration. Interestingly, they found ablation in adults also resulted in regeneration of the scxa+ tendon cells. Using a similar ablation methodology in the zebrafish, another group depleted tenocytes in the trunk myotendinous junction via nkx3.1:Gal4; UAS:NTR-mCherry and col1a2:Gal4; UAS:NTR-mCherry transgenic lines and found disrupted muscle morphology [277]. In contrast to tendon cell ablation in zebrafish which caused defective myotendinous junction function, Scleraxis-lineage cell depletion in mice however improved the biomechanical properties of the tendon after injury [408]. It is unclear why in some contexts Scx-lineage cells are important for proper healing and regeneration, but not in others. Clearly, more work is necessary to dissect the complexities of tendon healing in regenerative and non-regenerative contexts. The zebrafish provides a key platform for in vivo examination of tenocyte regeneration in the future.

More recently, a zebrafish model of ligament injury was established with the goal of testing jaw joint cartilage regeneration [409]. The jaw joint damage was introduced by transecting the interopercular–mandibular ligament that can cause jaw joint destabilization. They showed, through transgenic reporter imaging, genetic ablation and single-cell RNA sequencing, multiple cellular populations including sox10+ and grem1a+ cells contributed to jaw joint cartilage regeneration. However, the ability of the zebrafish to regenerate the ligament in this context remains unexplored. Certainly, this is an exciting direction given the frequency of ligament tears in humans, particularly for the anterior cruciate ligament, which cannot reattach without surgical intervention. The emerging models for tendon and ligament regeneration often focus on the cranial or axial tendons and ligaments as the adult pectoral fins consist of distal fin rays connected by muscles to the proximal pectoral girdle, but without long tendinous attachments as found in mammalian limbs [410–412]. These recent works lay a critical foundation for employing zebrafish to understand tendon and ligament regeneration, and the zebrafish model will very likely emerge as a powerful model for discoveries into the cellular and molecular mechanisms of tendon and ligament development and repair.

5. Discussion and future directions

Research in the zebrafish model has grown exponentially in the past two decades. The feasibility of genetic manipulations, imaging, and lineage tracing techniques along with a relatively low cost to maintain zebrafish lines compared to mammalian housing has made it an accessible model for many labs. Technological advancement in genetic editing tools and next generation sequencing strategies have further accelerated work in this system. With high gene homology to humans and conserved developmental processes between vertebrates, the zebrafish is an attractive model for both understanding foundational mechanisms underlying developmental and regenerative biology and also in modeling human diseases. As described throughout this review, these studies include generating zebrafish mutants to model human disease, but they can also be predictive of human disease loci [9]. For example, Frank Eames and colleagues identified mutants with reduced cartilage matrix and increased perichondral bone formation in an ENU mutagenesis screen [413]. Positional cloning revealed mutations in enzymes in the proteoglycan synthesis pathway, fam20b and xylosyltransferase1 (xylt1), as phenotype causing, highlighting the critical function of proteoglycan synthesis in endochondral ossification. Several years later, studies showed that mutations of FAM20B and XYLT1 in humans are associated with Desbuquois skeletal dysplasia (DBSD), a chondrodysplasia characterized by skeletal changes including increased ossification with short limbs and stature [414, 415]. Complementing these studies, the robust regenerative abilities of the fish have been examined in cellular and molecular detail, providing a blueprint for improving healing mechanisms in humans.

The zebrafish model has also emerged as a prominent model for understanding developmental biology at a single cell resolution. A number of groups have utilized single-cell technologies to understand embryogenesis in zebrafish, including studies focused on neural crest, which gives rise to most of the craniofacial skeleton [416–423]. In the context of skeletal development, a recent study carefully mapped neural crest derivatives in the craniofacial skeleton across zebrafish development, generating both scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets for a range of timepoints as early as 36 hpf and as late as 6 months of age. The authors showed that skeletogenic identities within neural crest are progressively prefigured at an epigenetic level and identified transcriptional signatures for putative multipotent skeletal progenitors and metabolically unique fibroblasts that support the craniofacial skeleton [423]. These datasets will undoubtedly be a staple for zebrafish researchers interested in the development and regeneration of skeletal tissues, and it will be very interesting to understand how the programs and cell types captured in these datasets relate to programs that are activated during regenerative processes. Such work is already underway in the zebrafish fin with recent reports describing fin regeneration at single cell resolution and demonstrating the pathways required within macrophages, epithelia and osteoprogenitors during fin regeneration [424–426]. Single cell genomics is also now being integrated with lineage tracing tools, enabling gene expression and epigenetic analyses to be combined with lineage data in a single experiment [130, 140–142, 417]. These tools will drive discovery across species and tissues, and the ease of transgenesis and mutagenesis will make zebrafish a leader in developmental and regenerative biology.

As indicated throughout this review, the zebrafish has been a powerful model to understand skeletal development, and specifically bone and cartilage development. Research investigating osteoclasts, tendons and ligaments, and teeth remain growing areas in the zebrafish community. As these emerging research areas mature, the zebrafish’s strengths with respect to imaging and genetics will enable researchers to investigate the complex tissue interactions that drive skeletal shape and function. Complemented with new genomic technologies and precise genetic editing, and considering the relatively low cost to maintain zebrafish, the growing number of disease models, and the advent of multiplex single cell experiments [427–429], the zebrafish model will be a critical discovery model for skeletal development and regeneration.

Acknowledgements

DTF was supported by the HHMI Hanna Gray Fellows Program. X.N. and J.L.G. were supported by the NIH/NIAMS AR074541 and the Conine Family Fund.

References

- 1.Kimmel CB, Genetics and early development of zebrafish. Trends Genet, 1989. 5(8): p. 283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howe K, et al. , The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature, 2013. 496(7446): p. 498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli F, et al. , Zebrafish: A Resourceful Vertebrate Model to Investigate Skeletal Disorders. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2020. 11: p. 489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietrich K, et al. , Skeletal Biology and Disease Modeling in Zebrafish. J Bone Miner Res, 2021. 36(3): p. 436–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valenti MT, et al. , Zebrafish: A Suitable Tool for the Study of Cell Signaling in Bone. Cells, 2020. 9(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergen DJM, Kague E, and Hammond CL, Zebrafish as an Emerging Model for Osteoporosis: A Primary Testing Platform for Screening New Osteo-Active Compounds. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2019. 10: p. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lleras-Forero L, Winkler C, and Schulte-Merker S, Zebrafish and medaka as models for biomedical research of bone diseases. Dev Biol, 2020. 457(2): p. 191–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu N, et al. , The Progress of CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing in Generating Mouse/Zebrafish Models of Human Skeletal Diseases. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2019. 17: p. 954–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mari-Beffa M, Mesa-Roman AB, and Duran I, Zebrafish Models for Human Skeletal Disorders. Front Genet, 2021. 12: p. 675331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]