Abstract

Aim

To develop and user test an evidence-based patient decision aid for children and adolescents who are considering anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.

Design

Mixed-methods study describing the development of a patient decision aid.

Setting

A draft decision aid was developed by a multidisciplinary steering group (including various types of health professionals and researchers, and consumers) informed by the best available evidence and existing patient decision aids.

Participants

People who ruptured their ACL when they were under 18 years old (ie, adolescents), their parents, and health professionals who manage these patients. Participants were recruited through social media and the network outreach of the steering group.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Semistructured interviews and questionnaires were used to gather feedback on the decision aid. The feedback was used to refine the decision aid and assess acceptability. An iterative cycle of interviews, refining the aid according to feedback and further interviews, was used. Interviews were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

We conducted 32 interviews; 16 health professionals (12 physiotherapists, 4 orthopaedic surgeons) and 16 people who ruptured their ACL when they were under 18 years old (7 were adolescents and 9 were adults at the time of the interview). Parents participated in 8 interviews. Most health professionals, patients and parents rated the aid’s acceptability as good-to-excellent. Health professionals and patients agreed on most aspects of the decision aid, but some health professionals had differing views on non-surgical management, risk of harms, treatment protocols and evidence on benefits and harms.

Conclusion

Our patient decision aid is an acceptable tool to help children and adolescents choose an appropriate management option following ACL rupture with their parents and health professionals. A clinical trial evaluating the potential benefit of this tool for children and adolescents considering ACL reconstruction is warranted.

Keywords: adolescents, knee, orthopaedic sports trauma, paediatric orthopaedics, paediatric orthopaedic & trauma surgery, rehabilitation medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

We developed a decision aid that satisfies the International Patient Decision Aid Standards criteria and used mixed methods to evaluate acceptability of the decision aid.

One-on-one interviews conducted with participants from different countries allowed for in-depth feedback to be gathered on the decision aid, but the usability of the decision aid may be limited by the number of interviews with participants from each country.

We were able to interview health professionals who manage children who have ruptured their anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) but were unable to recruit children–participants to interview with their parents.

Our patient decision aid was limited by the lack of high-quality evidence comparing rehabilitation only to ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation in children and adolescents.

The systematic review used to inform estimates of benefits and harms included older studies that did not always report details of rehabilitation and may not reflect advances in treatment.

Introduction

The incidence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures continues to increase.1 The total annual incidence of ACL ruptures in children and adolescents rose by 46% between 1994 and 2013 in the USA and the overall annual rate increased by 147.8% between 2005 and 2015 in Australia.2 3 This increase has been linked to more children and adolescents participating in organised sport, increased intensity of training, and, potentially, a focus on single-sport specialisation at an earlier age.4–6 The number of ACL reconstruction surgeries in children and adolescents is also increasing globally1 6–8 despite non-surgical treatment (rehabilitation only) being an option.9

Recommended management options following ACL rupture include rehabilitation only, rehabilitation with the choice to undergo ACL reconstruction at a later time or early ACL reconstruction.10 11 Research comparing these options is scarce, particularly in children and adolescents.9 Two randomised control trials (RCT) (n=16711; n=121,10) have shown that early ACL reconstruction in adults does not result in superior knee function, sports participation and quality of life compared with rehabilitation only with the option for delayed ACL reconstruction. A third RCT (n=31612) found that ACL reconstruction was clinically superior to rehabilitation alone for adults with non-acute ACL injury and long-term knee instability. However, there are no RCTs directly comparing these treatment options in children or adolescents.13

All treatment options following ACL rupture have risks, with recent guidelines and systematic reviews highlighting uncertainty regarding which approach is superior for children and adolescents. International consensus guidelines state rehabilitation only is a viable and safe option following ACL rupture in skeletally immature children without associated injuries or major instability problems.9 14 However, some guidelines also state ‘repairable’ injuries (eg, bucket-handle meniscal tear) associated with an ACL rupture should be considered an indication for early ACL reconstruction and meniscal repair.9 15 Two recent systematic reviews13 16 present conflicting evidence on the certainty of meniscus injury risk when choosing rehabilitation alone or considering the timing of a potential ACL reconstruction. Given this uncertainty and potential impact of poor management choices, there is a need for better evidence-based resources.

Patient decision aids are resources that present balanced information on the benefits and harms of different treatment options. They aim to improve the likelihood of informed choices and active participation of patients in healthcare decisions without negative patient outcomes.17 Supporting shared decision-making in children and adolescents following ACL rupture is necessary given the possible consequences of poorly individualised treatment.9 18 19 Currently, there is no patient decision aid for children and adolescents who have ruptured their ACL. A patient decision aid could help align expectations with evidence and improve patient satisfaction.

Our aim was to develop and user-test a patient decision aid for children and adolescents following ACL rupture to be used with parents and health professionals that presents evidence-based information on treatment options.

Methods

Initial design of the decision aid

We developed a patient decision aid informed by the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) checklist and Collaboration Evidence Update 2.0.20 A multidisciplinary steering group was assembled (study authors), including topic experts on ACL injury and physiotherapists with experience managing ACL ruptures (AG, JZ, MM, DA, EP, CM, SF and SM), people who have experienced an ACL rupture (SF, MM, EP and IAC) and one who was 18 years old when they ruptured their ACL (SF), an orthopaedic surgeon (IH) and patient decision aid and shared decision-making experts (KM, TH and RT). The first draft of the decision aid was informed by a template used for previous decision aids (for Achilles rupture,21 shoulder pain,22 antibiotics23 and knee arthroscopy24) developed by some authors in the steering group (JZ, MM, KM, TH, RT, CM and IH). Key features adopted from these decision aids included questions to consider when talking to health professionals, icon arrays to present statistics, and a table comparing the potential benefits and harms of each management option. Decision science evidence suggests these features improve patient decision-making.25–28 We also included statements of the quality of evidence, study participants demographic information and a reference list to give further context to statistics used in the decision aid.

We used evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis on rehabilitation only and early or delayed ACL reconstruction in children and adolescents to inform the numeric estimates of benefits and harms.13 We decided not to present benefits and harms data from the RCTs comparing rehabilitation only or delayed ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation to early ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation in adults.10–12 19 The decision to exclude adult data was to avoid overloading children and adolescents with statistics that may not be relevant to them. Expert opinion and consensus from the multidisciplinary steering group were used to inform all information presented in the decision aid (eg, the benefits, harms and practical issues of each management option). The steering group provided feedback on the first draft of the decision aid before we began semistructured interviews.

Recruitment

All participant groups were recruited through social media, snowballing and using the steering group’s collaboration network. Health professionals who participated in the study also assisted with recruitment of adolescent, adult and parent participants through referrals.

Using a preinterview questionnaire, we purposively sampled participants to achieve diversity in age, gender and ethnicity. For health professionals, we also purposively sampled to achieve diversity in profession, years of experience and country of practice. We adjusted our purposive sampling to recruit people with different characteristics from those already recruited. Before proceeding to the preinterview questionnaire, all participants provided consent by checking a box that confirmed they had read the participant information sheet and consent form and agreed to participate in the study.

Data collection

The data collection process involved a preinterview questionnaire (online supplemental files 1–4), semistructured interview (online supplemental files 5–7) and acceptability questionnaire (online supplemental files 8 and 9).

bmjopen-2023-081421supp001.pdf (147KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp002.pdf (150KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp003.pdf (148.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp004.pdf (94.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp005.pdf (120.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp006.pdf (120.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp007.pdf (114.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp008.pdf (38.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp009.pdf (34.3KB, pdf)

Preinterview questionnaires

For adolescent, adult and parent participants, we gathered data on demographics (eg, gender, age), country of birth, schooling/employment details, time since first ACL rupture, details about any other structures that were damaged, use of ACL reconstruction, rerupture, previous and current sports participation level, and factors related to treatment decision-making (online supplemental files 1–3).

For health professionals, we gathered data on demographics, profession and country of training/qualification, type of health professional, years of experience, clinical setting, average number of patients they manage with an ACL rupture per year and the percentage of patients they advise to have ACL reconstruction (online supplemental file 4).

Semistructured interviews

In accordance with IPDAS guidance,29 30 semistructured interviews were used to gather feedback on participant’s views of the decision aid and establish the best way to present different aspects such as treatment options, numeric estimates of benefits and harms, questions to ask health professionals, practical issues and visual layout. Interview guides were created to provide structure and group-specific prompts (online supplemental files 5–7). A trial interview was conducted as a test prior to beginning formal interviews. Interviews were conducted online via video conference (Zoom) by male researchers with experience in conducting qualitative interviews (AG and IAC), and lasted between 30 and 50 min. Four interviews were conducted by physiotherapy students who were under the supervision of the lead author.

Participants were informed of the reason for the study and provided a draft decision aid to view prior to the interview. However, not all participants viewed the decision aid before the interview. Changes to the decision aid were made throughout the interview process and participants were shown modifications against previous versions so they could provide input on whether changes were useful (online supplemental file 10). All interviews were recorded (with verbal consent obtained from participants). Participants were asked to ‘think out loud’ and encouraged to provide feedback as they viewed each page of the decision aid (eg, if they thought aspects of the decision aid could be improved or could be presented in a different way). During participant interviews, the interviewer took notes to highlight key concepts emerging from the interview and direct further questioning as needed. Following each interview, participants were sent an email thanking them for their time to participate; there was no incentive offered to participate in the study. All interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis and participants had the opportunity to review the transcript of their interview prior to data analysis if they wished.

bmjopen-2023-081421supp010.pdf (4.3MB, pdf)

Acceptability questionnaires

Following each interview, an acceptability questionnaire was completed by participants, either during the interview or via a questionnaire link sent via email following the interview. A separate acceptability questionnaire, adapted from The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute,31 was created for adolescent, adult and parent participants (online supplemental file 8) and health professional participants (online supplemental file 9).

Data analysis

We reported the qualitative aspects of this study according to the 32-item Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (online supplemental file 11).32 The COREQ is a 32-item checklist that allows for reporting of important aspects of the research team, study methods, context of the study, findings, analysis and interpretation.

bmjopen-2023-081421supp011.pdf (132.3KB, pdf)

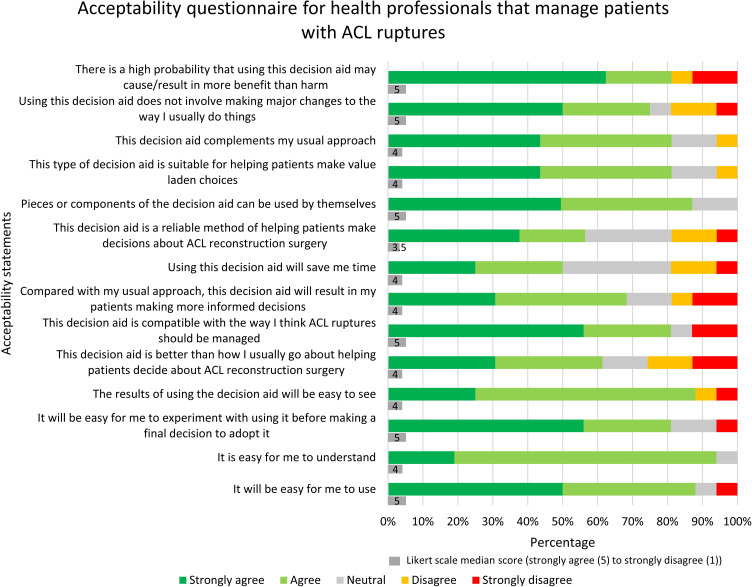

Preinterview and acceptability questionnaire responses were summarised using descriptive statistics (means and SDs, counts and percentages). Adolescent, adult and parent participant acceptability questionnaires (online supplemental file 10) involved rating sections of the decision aid as ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’ or ‘excellent’, the length of the decision aid, balance of information presented and its potential usefulness. The health professional participant acceptability questionnaire (online supplemental file 11) used a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree=5; strongly disagree=1) to assess agreement with various statements. We presented Likert scores as the percentage of responses for each category and as means (SD).

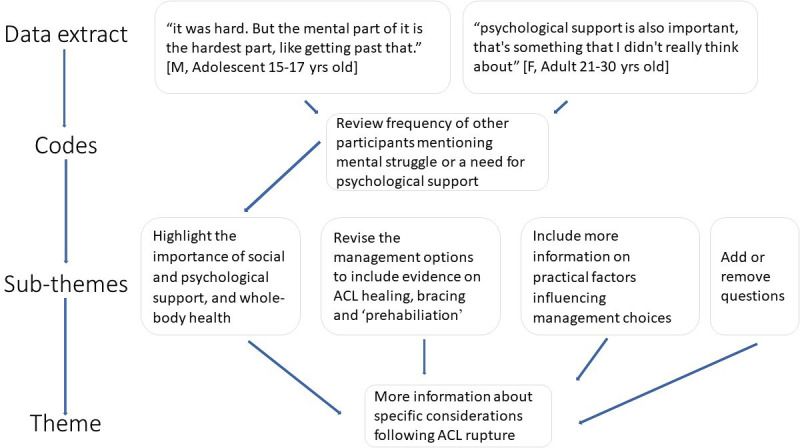

All interview data were analysed using thematic analysis; a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns within data.33 Grounded theory using an inductive approach underpinned how data were collected and analysed. Two researchers (AG and SM) independently familiarised themselves with the interviews (via audio recordings or transcripts), recorded initial observations and identified concepts relevant to the questions asked. The two researchers developed a framework to organise concepts into broader themes and subthemes in Excel. Any disagreements in categorising concepts into themes and subthemes were discussed and resolved with a third author (JZ). The mapping of themes and subthemes (figure 1) was iterative as new data emerged so that the decision aid was continually updated before new interviews were conducted. Multiple iterative cycles of revisions were performed, and new versions of the decision aid were circulated to the steering group to reach consensus following changes from interviews. Consensus was reached by the majority of the steering group agreeing with proposed changes. In some cases, revisions were very minor changes (eg, correcting typos, rewording a sentence). No further interviews were conducted once data saturation was achieved (no new feedback emerged) and participants had an overall positive impression of the decision aid.

Figure 1.

Formation of subthemes and themes.

Patient and public involvement

People who experienced an ACL rupture were part of the authorship group (SF, MM, EP and IAC). One was 18 years old when they ruptured their ACL (SF).

Results

Adherence to the IPDAS criteria and user-centredness

The decision aid (online supplemental file 12) met all 6 of the criteria to be considered a decision aid, all 6 of the criteria to reduce the risk of harmful bias, and 21 of the 23 quality criteria according to the IPDASi checklist (V.4.0)34 (online supplemental file 13). The two IPDASi criteria that were not met involved evaluating the decision aid. Readability was assessed including all the decision aid text (Grade 11.8) and without necessary complex words (Grade 9.7) using the SHeLL Editor (https://shell.techlab.works). Our decision aid also met 10 of the 11 criteria for user-centredness (online supplemental file 14) as assessed by the user-centred design 11-item measure.35

bmjopen-2023-081421supp012.pdf (6.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp013.pdf (45.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp014.pdf (33KB, pdf)

Participant characteristics and decision aid acceptability

A total of 32 initial interviews were completed; 16 health professionals who manage ACL ruptures (12 physiotherapists, 4 orthopaedic surgeons) and 16 people who had ruptured their ACL (7 adolescents and 9 who were now adults), 8 of these interviews were with a parent (1 parent was interviewed with 2 adolescents, 1 with an adult and 1 alone). Additional interviews were conducted with three health professionals (2 physiotherapists and 1 orthopaedic surgeon) who wanted to give further feedback but ran out of time in their initial interview. No participants withdrew from the study once their interview had commenced. One parent and adolescent did not participate in an arranged interview as they had not been offered rehabilitation only treatment and the parent did not want to potentially upset them. Participant characteristics are presented in tables 1 and 2. All participants completed the acceptability questionnaire except one adolescent participant (figure 2 and table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who sustained an ACL rupture and parents of adolescent children who sustained an ACL rupture

| Participant groups preinterview questionnaire responses (all statistics are reported as mean (SD) or N (%), unless specified otherwise) | Adolescents (n=7) | Adults (n=9) | Parents (n=8) |

| Age (years) range | 16 (1) 15–17 | 26 (5.1) 18–33 | 46 (3.8) 41–51 |

| Female | 5 (71%) | 3 (33%) | 8 (100%) |

| Country of birth | |||

| Australia | 3 (43%) | 7 (78%) | 3 (38%) |

| Philippines | – | – | 1 (13%)* |

| USA | 2 (29%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (25%) |

| South Africa | 2 (29%) | – | 1 (13%) |

| Sri Lanka | – | 1 (11%)* | – |

| Sweden | – | – | 1 (13%) |

| Current grade at school | |||

| Grade 10 | 4 (57%) | – | – |

| Grade 11 | 1 (14%) | – | – |

| Grade 12 or completed grade 12 | 2 (28%) | – | – |

| Highest level of education | |||

| University graduate or postgraduate degree/s | – | 6 (66%) | 7 (88%) |

| TAFE/trade | – | 1 (11%) | 1 (13%) |

| High school (completed) | – | 2 (22%) | – |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed full time | – | 5 (56%) | 3 (38%) |

| Employed part time or casual | – | 3 (33%) | 3 (38%) |

| Student | – | 1 (11%) | – |

| Other (eg, self-employed) | – | – | 2 (25%) |

| Private health insurance | 7 (100%) | 7 (78%) | 7 (88%) |

| Age at the time of ACL rupture (years) range | 14.7 (1) 13–16 | 15.7 (1) 14–17 | 14.4 (1) 13–16‡ |

| Concomitant injury at the time of ACL rupture§ | 4 (57%) | 6 (67%) | 6 (75%)‡ |

| Lateral meniscus | 2 (29%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (25%)‡ |

| Medial meniscus | 3 (43%) | 4 (44%) | 3 (38%)‡ |

| MCL | – | 1 (11%) | 2 (25%)‡ |

| PCL | 1 (14%) | – | – |

| Cartilage damage | – | 2 (22%) | – |

| Unsure of additional damaged structures | – | 1 (11%) | – |

| Had ACL reconstruction | 3 (43%) | 9 (100%) | 4 (50%)‡ |

| Had a subsequent ACL rupture (ipsilateral or contralateral) at the time of the interview¶ | 0 (0%) | 4 (44%) | 0 (0%)‡ |

| Had another ACL reconstruction¶ | 0 (0%) | 3 (33%) | 0 (0%)‡ |

| Time since ACL reconstruction¶ | |||

| 6–12 months | 2 (66%) | – | 1 (25%)‡ |

| 12–24 months | – | 2 (22%) | 3 (75%)‡ |

| >24 months | 1 (33%) | 7 (78%) | – |

| Highest level of activity participation prior to ACL rupture† (Median score (IQR)) | 9 (1) | 7 (2) | 9 (1.75)‡ |

| Highest current level of activity participation† (median score (IQR)) | 6 (6) | 4 (3.5) | 2 (7.5)‡ |

| Which one factor most influenced the decision to have (or not have) an ACL reconstruction | |||

| Someone you know (eg, a friend) | 2 (29%) | – | – |

| Choice due to age (eg, being young) | 1 (14%) | – | – |

| Wanting to return to sport | 2 (29%) | 4 (44%) | 2 (25%) |

| Prevent further damage | – | 2 (22%) | – |

| Recommendation from a health professional | 2 (29%) | 3 (33%) | 4 (50%) |

| Other (eg, research and beliefs) | – | – | 2 (25%) |

| Happiness with treatment choice | |||

| Extremely happy | 5 (71%) | 6 (66%) | 2 (25%) |

| Somewhat happy | – | 1 (11%) | 2 (25%) |

| Neither happy nor unhappy | 1 (14%) | 1 (11%) | 1 (13%) |

| Somewhat unhappy | 1 (14%) | – | 1 (13%) |

| Extremely unhappy | – | 1 (11%) | 2 (25%) |

One parent was interviewed without their adolescent; one parent was interviewed with an adult and one parent was interviewed with two adolescents.

*Management of ACL rupture were in Australia and not the country of birth.

†Scores are based on the Tegner Activity Scale (0–10), higher scores equal higher levels of patient-reported activity.

‡Refers to data reported by parents about their adolescent child.

§Some people had more than one concomitant injury to their ACL rupture.

¶Percentage of those who had ACL reconstruction.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; MCL, medial collateral ligament; N, number of adolescents and adults who ruptured their ACL and parents of adolescent children who ruptured their ACL; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament; TAFE, technical and further education.

Table 2.

Characteristics of health professionals that manage patients with ACL ruptures

| Participant groups preinterview questionnaire responses (all statistics are reported as mean (SD) or N (%), unless specified otherwise) | Health professionals (n=16) |

| Age (years) range | 39 (8.6) 23–54 |

| Female | 3 (19%) |

| Country of health professional training* | |

| Australia | 11 (69%) |

| Germany | 1 (6%) |

| Switzerland | 1 (6%) |

| UK | 1 (6%) |

| USA | 2 (13%) |

| Role | |

| Physiotherapist | 12 (75%) |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 4 (25%) |

| Years of experience | 11.5 (7.3) |

| Work setting | |

| Private practice | 11 (63%) |

| Private hospital | 1 (6%) |

| Public hospital | 4 (25%) |

| Other | 1 (6%) |

| Average number of patients with ACL rupture managed per year | |

| 5 | 1 (6%) |

| 5–10 | 5 (31%) |

| 10–20 | 2 (13%) |

| 20–30 | 3 (19%) |

| >50 | 5 (31%) |

| The percentage of patients recommended to have ACL reconstruction following ACL rupture | 67 (20.3) |

*All health professional participants were practising in their country of training at the time of interviews.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; N, number of health professionals that manage patients with ACL ruptures.

Figure 2.

Acceptability questionnaire for health professionals that manage patients with ACL ruptures (n=16; 12 physiotherapists, 4 orthopaedic surgeons).

Table 3.

Acceptability questionnaire for people who sustained an ACL rupture (n=16) (adolescents (n=7)*, adults (n=9)) and parents of adolescent children who sustained an ACL rupture (n=8)

| Acceptability items (All statistics are reported as N (%)) | Adolescents, adults and parents (n=23) |

| Section of decision aid rated as excellent or good | |

| Who should read this decision aid? | 23 (100%) |

| Diagram of management options following ACL rupture | 23 (100%) |

| The treatment options covered in this decision aid | 23 (100%) |

| Comparing benefits and harms of each management option for those aged under 18 years old | 22 (96%) |

| Summary of benefits and harms of each management option for those aged under 18 years old | 23 (100%) |

| The length of the decision aid was | |

| Just right | 23 (100%) |

| The amount of information was | |

| Just right | 21 (91%) |

| Too little | 1 (4%) |

| Too much | 1 (4%) |

| I found the decision aid | |

| Balanced | 18 (78%) |

| Slanted towards rehab only (or delayed ACL surgery) | 2 (9%) |

| Slanted towards ACL reconstruction surgery (early ACL surgery) | 3 (13%) |

| Agreed they would have found this decision aid ‘extremely useful’ or ‘very useful’ when making the decision about ACL reconstruction surgery | 18 (78%) |

| Agreed this decision aid would have made their decision easier | 20 (87%) |

*One adolescent participant did not complete the acceptability questionnaire.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; N, number of adolescents and adults who have sustained an ACL rupture and parents of adolescent children who sustained an ACL rupture.

Feedback for each section of the decision aid

Although most suggestions were implemented, some conflicted with others or were not possible to implement. Online supplemental file 15 outlines feedback we did not incorporate in the decision aid and our justification for this.

bmjopen-2023-081421supp015.pdf (68KB, pdf)

Thematic analysis of interviews

Summary of interview themes and subthemes:

Themes 1 and 2: positive and negative feedback

Most participants gave positive feedback about the design and usability of the decision aid, but health professionals expressed a range of views on the content.

I wish I had something like this for either of my ACLs. Just to have it all in one place, is good (M, 21–30 years old, adult).

It would be wonderful to have this handed out (F, 41-50 years old, parent).

It’s well thought out, nice and balanced. It’s good (M, 31-40 years old, orthopaedic surgeon).

I really would suggest that you reconsider what you’re doing (M, 51-60 years old, orthopaedic surgeon).

I found the whole thing very wordy (M, 41-50 years old, orthopaedic surgeon).

Theme 3: how to use the decision aid in practice

Some health professionals suggested clarifying the influence of additional injuries (eg, meniscus tear) or instability on management decisions. Most participants suggested the decision aid should not replace professional advice and it should promote individual management.

I also feel you have to have a health professional to guide you (F, 41-50 years old, parent).

I think a lot of it just comes down to the individual’s context, and their goals, and then also their present functional limitation (F, 21–30 years old, physiotherapist).

Theme 4: more information about specific considerations following ACL rupture

Adolescents frequently suggested including social and psychological support and whole-body health. Adolescents also suggested including information on planning for additional support and show fear of further injury or difficulties maintaining motivation is normal. Some health professionals suggested including ACL guidelines (eg, professionally endorsed ACL guidelines) and revising management options to include ACL healing, bracing and ‘prehabilitation’. Some participants suggested including practical information on time needed to book ACL reconstruction, graft options, size of scars and loss of muscle strength and control. Modifying questions to ask health professionals were frequently suggested and some parents were particularly concerned about costs and pain relief.

They don’t talk about the psychological effects that it has on someone (F, 15-17 years old, adolescent).

As far as this child is going to really need high care and nurturing, what have you got in place to ensure this person’s needs are going to be met? (F, 41–50 years old, parent).

The potential for the ACL to heal, I think parents and kids would be very interested in that (M, 31-40 years old, physiotherapist).

Theme 5: change or add information on rehabilitation, exercise and return to sport

Some health professionals suggested return to sport following ACL rupture is not guaranteed but most participants agreed rehabilitation timeframes gave realistic expectations. All participant groups mentioned rehabilitation testing should be included (eg, strength and hop tests) and to differentiate between restricted/unrestricted training and competition sport. Most participants also suggested including consideration for long-term goals and continuing to exercise beyond 12 months.

It’s easy to get ahead of yourself and many times parents want to rush as well (F, 41-50 years old, parent).

Some people may think once I finished my nine months of therapy, I’m done. But it’s like, it’s a lifelong journey (F, 41–50 years old, parent).

You need a certain level of dedication (F, 15-17 years old, adolescent).

Theme 6: modify language and formatting used

Simple language, being concise and removing unnecessary text were frequently suggested. All participant groups suggested modifications to formatting such as layout, graphs, colour, pictures or icons and statistics (eg, most preferred icon array images to bar graphs or ‘x in 100 people’ to percentages).

Positive presentation of information, harms and return to sport was frequently suggested by all participant groups. Mixed views were expressed about risk of additional injury (eg, the relationship between meniscus damage and osteoarthritis), general surgery, paediatric specific risks and return to sport.

I feel like the language is too academic. To me, I think it could be dumbed down more (M, 31-40 years old, physiotherapist).

You want them to be finding the success stories and, yeah, have a positive outlook as well, rather than focusing on who didn't get back (F, 41–50 years old, parent).

You could say potential harms and precautions (F, 41-50 years old, parent).

Theme 7: understanding the translation of research

Some health professionals suggested the decision aid should be seen before an appointment with a health professional (eg, before seeing an orthopaedic surgeon). Participants frequently suggested difficulty navigating the uncertainty of returning to sport with both treatment options. Participants more frequently had views to remove adult data, but some suggested providing context to adult statistics.

When patients are overwhelmed, they, tend to just kind of they grasp for certainty (M, 31-40 years old, physiotherapist).

You’re using adult data in a decision aid for children, and you can’t do that (M, 51-60 years old, orthopaedic surgeon).

I would rather they have information that is relevant to their population and their category only, even if it is lower quality (M, 31–40 years old orthopaedic surgeon).

Discussion

Summary of findings

Most adolescents, parents and adults rated all aspects of the decision aid as good-excellent (eg, presentation, comprehensibility, length, graphics, formatting and amount of information). Following interviews, we identified seven main themes with subthemes (online supplemental file 16). The interviews highlighted agreement with most of the decision aid content (eg, management options, questions to ask health professionals, summary of benefits and harms). Most health professionals selected ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ when asked to rate statements about the decision aid but some health professionals had opposing views on components of the decision aid (eg, using statistics from studies including participants over 18 years old, potential risks and return to sport).

bmjopen-2023-081421supp016.pdf (154.8KB, pdf)

Meaning of the study

Analysis of the interviews revealed that most aspects of the decision aid were agreed on by participants despite suggestions for refinement. However, some health professionals had divided opinions on the evidence used to inform content and rehabilitation time frames. Feedback from all participant groups consistently highlighted the importance of positive messaging, social and psychological support and considering long-term goals. Most participant groups also gave positive feedback on ‘questions to consider asking health professionals’.

Most participants agreed the decision aid clearly outlines its intended users and treatment options but there were mixed views on deciding optimal management. Some participants suggested bringing more attention to the impact of additional injury (eg, meniscus damage) to decision-making or adding other treatment options (eg, bracing, ACL healing and ‘prehabilitation’). We decided to present only two management options side by side for ease of comparison, which is similar to other decision aids for musculoskeletal conditions.21 22 Opinions of the optimal management for children and adolescents who have additional injuries to their ACL rupture were mixed and evidence remains uncertain.13 16 The decision aid prompts patients to confirm their diagnosis with a team of health professionals to gain a balanced opinion on their individual circumstance and discuss multiple factors that may influence their choice (eg, presence of ‘repairable’ injuries, if their knee gives way and activity levels9).

Some physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons had conflicting views on using evidence from research that included participants over 18 years old. Given the decision aid is not for adults with an ACL rupture, we decided not to present data from studies on people over 18 years to avoid children and adolescents having to consider multiple data sources and potentially becoming confused.36 The decision aid is designed for children and adolescents and includes prompts to encourage management that considers individual circumstances and different rates of child development (eg, questions to consider when talking to a health professional and key points).

Although children and adolescents should be encouraged to take an active role in the decision-making process, interviews with parents suggested that individual circumstances may dictate how the decision aid is best used. Some parents suggested the decision aid would save them time when researching information to help with making treatment choices (eg, getting this handout instead of me having to go home and Google, I Googled many, many nights trying to find you know, something like this’ (F, 41–50 years old, parent)). One parent withdrew their adolescent child before the interview due to concerns that discussion of potential harms could disrupt their child’s focus on rehabilitation. This adolescent recently had ACL reconstruction and was not given the option to have non-surgical management based on their injuries. Overall, parents and health professionals should consider encouraging children and adolescents to be involved in shared decision-making9 37 38 and consider that the decision aid is designed to be used before making the management decision. Once a decision is made, particularly an irreversible decision, parents and health professionals may have an important role in guiding focus and promoting optimism.

The decision aid can facilitate parents discussing their child’s treatment preference, sport choice and potential harms of participation. Parents and health professionals should acknowledge their supporting role in treatment decisions (eg, ‘it’s important that we listen to the kids and what they have to say, it’s their body’ (F, 41–50 years old, parent)). Discussions of sporting choice may solidify a decision or lead to diversifying sporting participation that has been shown to encourage the development of resilient self-identities.36 Parental anxiety or pain catastrophising has been shown to negatively influence children’s anxiety, postoperative pain and ability to perform rehabilitation.39 While potential harms and uncertainty of returning to sport can be a sensitive topic, their acknowledgement could also provide reassurance to children and adolescences if something goes wrong (eg, ‘as a parent you’re trying to make sure they understand the decision they’re making’ (F, 41–50 years old, parent)).

Avoiding unrealistic expectations and including children and adolescents in decision-making was frequently mentioned by all participant groups. Using the decision aid could prevent decisions being made based on unrealistic expectations and help improve treatment satisfaction. It is accepted that patient satisfaction has been closely linked to expectations,40 the decision aid may help improve the mismatch between expectations and evidence. Many young athletes (86%) expect to return to sport following ACL reconstruction by 6 months which is much sooner than is recommended in accepted professional guidelines.41 42 While return to sport rates may be higher in children who have ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation compared with rehabilitation only,13 subsequent ipsilateral or contralateral ACL rupture following ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation can be as high as 32% in paediatric athletes.39 The reality is that despite anatomical surgical success or well-designed rehabilitation programmes, many athletes may never return to their preinjury athletic performance level or their primary sport.43

Interviews frequently highlighted that information regarding psychological and social support should be included in the decision aid. Sudden changes to sport participation can affect self-identity in children and adolescents who particularly mentioned the mental struggle of recovering post ACL rupture (eg, ‘the point that stands out to me, that was probably the stay positive one. Because the other year, it was hard. But the mental part of it is the hardest part, like getting past that’ (M, 15–17 years old, adolescent)). Children and adolescent self-identities can be fragile and absence from participating in a sport they depend on can be psychologically traumatising.39 Therefore, we decided to include messages to encourage the discussion and planning for psychological support. Health professionals should give early recognition to psychosocial factors that have been shown to affect mental well-being and ability to recover from injury.43 The decision aid incorporates reassurance and encourages monitoring physical and psychological recovery.

Strengths and limitations

Our development process (online supplemental file 17) had several strengths. The steering group includes people who experienced an ACL rupture and one who was 18 years old when they ruptured their ACL, the manuscript is transparent about the authors’ professional backgrounds, the design, conduct and reporting of this study were guided by the IPDAS criteria, we conducted one-on-one interviews with participants which allowed for in-depth feedback to be gathered on the decision aid, and used mixed methods to evaluate acceptability of the decision aid. The readability of our tool measured higher (grades 9–11) than recommendations (grade 8) but contains multiple features to support understanding and readability that align with best practice44 including bullet points, white space, images and subheaders. The tool, therefore, performs well relative to existing decision aids in terms of its attention to health literacy.44 We also included justification of the evidence used to inform numeric estimates of benefits and harms in the decision aid and used the highest quality evidence available comparing rehabilitation only and ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation for children and adolescents.13

bmjopen-2023-081421supp017.pdf (66.1KB, pdf)

Our patient decision aid was limited by the lack of high-quality evidence comparing rehabilitation only to ACL reconstruction followed by rehabilitation in children and adolescents. Emergence of future studies related to this topic will likely warrant an update of the evidence used in the decision aid. Another limitation is that evidence from older studies did not always report details of rehabilitation or consider advances in treatment to know if they reflect current recommended practice. We were unable to recruit any children participants to interview and adolescent participants were aged between 15 and 17 years old. We did interview health professionals who treat children and younger adolescents, but not being able to recruit children participants means the decision aid was not directly influenced by children’s feedback. Most authors are physiotherapists, and most health professional participants were physiotherapists (75%), trained in Australia (69%) and worked in private practice (63%) which may impact the themes that emerged from interviews (eg, views on costs and waiting time for ACL reconstruction). Recruitment of participants was difficult which was expected without offering incentives for their time. We did not directly involve children or adolescents in all stages of the study as consumers, and stakeholder involvement heavily influenced the design of the decision aid via feedback during online interviews and questionnaires on the acceptability of the decision aid. Our aim was to interview participants until we achieved data saturation, but we acknowledged that the majority of participants were Australian (60%). Including participants from several different countries may have made the decision aid more globally acceptable (eg, feedback was influenced by different cultures and healthcare systems) but the sample size of participants from each country may limit the usability of the decision aid for use in different countries. Future work includes adapting this decision aid for culturally and linguistically diverse populations as it is only presented in English.

Conclusion

Our patient decision aid appears to be an acceptable tool to help children and adolescents following ACL rupture choose between surgical and non-surgical management, with support from their parents and health professionals. Feedback from adolescents frequently suggested the importance of planning to include psychological and social support during rehabilitation. Feedback also suggested that health professionals should use positive messaging despite uncertainty of outcomes while avoiding the creation of unrealistic expectations. Our patient decision aid is a user-friendly tool that could improve decision-making in children and adolescents following ACL rupture. A randomised controlled trial evaluating its impact is the next important step.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

@AndrewGam, @marneemac, @davidandersonu1, @evpappas, @DrIanHarris, @stephfilbay, @rachelthomp, @Tsmmy_Hoffmann, @CGMMaher, @zadro_josh

Contributors: All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. Please find below a detailed description of the role of each author. ARG: developed and designed data collection tools, conducted data collection, analysed, and interpreted data, drafted and revised the manuscript and approved the final version to be published. MJM: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. DBA: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. EP: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published IAC: developed and designed data collection tools, conducted data collection, analysed, and interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. SM: developed and designed data collection tools, analysed and interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. IAH: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to published. SRF: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. KM: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. TCH: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. RT: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. CGM: developed and designed data collection tools, interpreted data and approved the final version to be published. JRZ: developed and designed data collection tools, conducted data collection, analysed, and interpreted data, drafted, and revised the manuscript and approved the final version to be published. The corresponding author (ARG) attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. As the guarantor, the corresponding author (ARG) accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. Artificial intelligence (AI) was only used to transcribe audio recordings of interviews for analysis.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: TH, KM and RT are unpaid members of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration Steering Committee.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author, Andrew R Gamble at andrew.gamble@sydney.edu.au.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (project number: 2022/008). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Zbrojkiewicz D, Vertullo C, Grayson JE. Increasing rates of anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000–2015. Med J Aust 2018;208:354–8. 10.5694/mja17.00974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beck NA, Lawrence JTR, Nordin JD, et al. ACL tears in school-aged children and adolescents over 20 years. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20161877. 10.1542/peds.2016-1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaw L, Finch CF. Trends in pediatric and adolescent anterior Cruciate ligament injuries in Victoria, Australia 2005–2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:599. 10.3390/ijerph14060599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perkins CA, Willimon SC. Pediatric anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am 2020;51:55–63. 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, et al. Sport-specific yearly risk and incidence of anterior Cruciate ligament tears in high school athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2016;44:2716–23. 10.1177/0363546515617742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dodwell ER, Lamont LE, Green DW, et al. 20 years of pediatric anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction in New York State. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:675–80. 10.1177/0363546513518412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Werner BC, Yang S, Looney AM, et al. Trends in pediatric and adolescent anterior Cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. J Pediatr Orthop 2016;36:447–52. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tepolt FA, Feldman L, Kocher MS. Trends in pediatric ACL reconstruction from the PHIS database. J Pediatr Orthop 2018;38:e490–4. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ardern CL, Ekås G, Grindem H, et al. International Olympic committee consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of Paediatric anterior Cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018;26:989–1010. 10.1007/s00167-018-4865-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, et al. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior Cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med 2010;363:331–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reijman M, Eggerding V, van Es E, et al. Early surgical reconstruction versus rehabilitation with elective delayed reconstruction for patients with anterior Cruciate ligament rupture: COMPARE randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021;372:n375. 10.1136/bmj.n375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beard DJ, Davies L, Cook JA, et al. Rehabilitation versus surgical reconstruction for non-acute anterior Cruciate ligament injury (ACL SNNAP): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2022;400:605–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01424-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. James EW, Dawkins BJ, Schachne JM, et al. Early operative versus delayed operative versus Nonoperative treatment of pediatric and adolescent anterior Cruciate ligament injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2021;49:4008–17. 10.1177/0363546521990817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Eitzen I, et al. Functional outcomes following a non-operative treatment algorithm for anterior Cruciate ligament injuries in Skeletally immature children 12 years and younger. A prospective cohort with 2 years follow-up. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:488–94. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krych AJ, Pitts RT, Dajani KA, et al. Surgical repair of Meniscal tears with concomitant anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients 18 years and younger. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:976–82. 10.1177/0363546509354055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ekås GR, Ardern CL, Grindem H, et al. Evidence too weak to guide surgical treatment decisions for anterior Cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review of the risk of new Meniscal tears after anterior Cruciate ligament injury. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:520–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision AIDS for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD001431. 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maguire E, Hong P, Ritchie K, et al. Decision aid prototype development for parents considering Adenotonsillectomy for their children with sleep disordered breathing. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;45:57. 10.1186/s40463-016-0170-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saueressig T, Braun T, Steglich N, et al. Primary surgery versus primary rehabilitation for treating anterior Cruciate ligament injuries: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:1241–51. 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stacey D, Volk RJ, IPDAS Evidence Update Leads (Hilary Bekker, Karina Dahl Steffensen, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Kirsten McCaffery, Rachel Thompson, Richard Thomson, Lyndal Trevena, Trudy van der Weijden, and Holly Witteman) . The International patient decision aid standards (IPDAS) collaboration: evidence update 2.0. Med Decis Making 2021;41:729–33. 10.1177/0272989X211035681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gan JFL, McKay MJ, Jones CMP, et al. Developing a patient decision aid for Achilles tendon rupture management: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2023;13:e072553. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zadro J, Jones C, Harris I, et al. Development of a patient decision aid on Subacromial decompression surgery and rotator cuff repair surgery: an international mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e054032. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coxeter PD, Mar CD, Hoffmann TC. Parents’ expectations and experiences of antibiotics for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:149–54. 10.1370/afm.2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O’Connor D, Hoffmann T, McCaffery K, et al. 85 evaluating a patient decision aid for people with degenerative knee disease considering Arthroscopic surgery: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Preventing Overdiagnosis Abstracts, December 2019, Sydney, Australia; December 2019. 10.1136/bmjebm-2019-POD.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoffmann TC, Bakhit M, Durand M-A, et al. Basing information on comprehensive, critically appraised, and up-to-date syntheses of the scientific evidence: an update from the International patient decision aid standards. Med Decis Making 2021;41:755–67. 10.1177/0272989X21996622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martin RW, Brogård Andersen S, O’Brien MA, et al. Providing balanced information about options in patient decision AIDS: an update from the International patient decision aid standards. Med Decis Making 2021;41:780–800. 10.1177/0272989X211021397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bonner C, Trevena LJ, Gaissmaier W, et al. Current best practice for presenting probabilities in patient decision AIDS: fundamental principles. Med Decis Making 2021;41:821–33. 10.1177/0272989X21996328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trevena LJ, Bonner C, Okan Y, et al. Current challenges when using numbers in patient decision AIDS: advanced concepts. Med Decis Making 2021;41:834–47. 10.1177/0272989X21996342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Witteman HO, Maki KG, Vaisson G, et al. Systematic development of patient decision AIDS: an update from the IPDAS collaboration. Med Decis Making 2021;41:736–54. 10.1177/0272989X211014163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trenaman L, Jansen J, Blumenthal-Barby J, et al. Are we improving? update and critical appraisal of the reporting of decision process and quality measures in trials evaluating patient decision AIDS. Med Decis Making 2021;41:954–9. 10.1177/0272989X211011120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Connor AC . A. User manual - acceptability, Available: http://www.ohri.ca/decisionaid/

- 32. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol 2016;12:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision AIDS: A modified Delphi consensus process. Med Decis Making 2014;34:699–710. 10.1177/0272989X13501721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Witteman HO, Vaisson G, Provencher T, et al. An 11-item measure of User- and human-centered design for personal health tools (UCD-11): development and validation. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e15032. 10.2196/15032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nyland J, Pyle B. Self-identity and adolescent return to sports post-ACL injury and rehabilitation: will anyone listen? Arthrosc. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022;4:e287–94. 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boland L, Graham ID, Légaré F, et al. Barriers and Facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2019;14:7. 10.1186/s13012-018-0851-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Opel DJ. A 4-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2018;142:S149–56. 10.1542/peds.2018-0516E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Matsuzaki Y, Chipman DE, Hidalgo Perea S, et al. Unique considerations for the pediatric athlete during rehabilitation and return to sport after anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022;4:e221–30. 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cole BJ, Cotter EJ, Wang KC, et al. Patient understanding, expectations, outcomes, and satisfaction regarding anterior Cruciate ligament injuries and surgical management. Arthroscopy 2017;33:1092–6. 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Armento A, Albright J, Gagliardi A, et al. Patient expectations and perceived social support related to return to sport after anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction in adolescent athletes. Phys Ther Sport 2021;47:72–7. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Webster KE, Feller JA. Expectations for return to Preinjury sport before and after anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2019;47:578–83. 10.1177/0363546518819454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vutescu ES, Orman S, Garcia-Lopez E, et al. Psychological and social components of recovery following anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction in young athletes: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:9267. 10.3390/ijerph18179267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Muscat DM, Smith J, Mac O, et al. Addressing health literacy in patient decision AIDS: an update from the International patient decision aid standards. Med Decis Making 2021;41:848–69. 10.1177/0272989X211011101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-081421supp001.pdf (147KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp002.pdf (150KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp003.pdf (148.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp004.pdf (94.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp005.pdf (120.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp006.pdf (120.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp007.pdf (114.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp008.pdf (38.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp009.pdf (34.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp010.pdf (4.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp011.pdf (132.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp012.pdf (6.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp013.pdf (45.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp014.pdf (33KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp015.pdf (68KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp016.pdf (154.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-081421supp017.pdf (66.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author, Andrew R Gamble at andrew.gamble@sydney.edu.au.