Summary:

Concurrent global rises in temperatures, rates and incidence of species decline, and emergence of infectious diseases represent an unprecedented planetary crisis. Recent intergovernmental reports have drawn focus to the escalating climate and biodiversity crises, and the connections between them, but interactions among all three pressures have been largely overlooked. Non-linearities and dampening and reinforcing interactions among pressures make considering interconnections essential to anticipating planetary challenges. Here, we elucidate the interconnections amongst the three global pressures of climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease. We define and exemplify causal pathways that link these axes of global change to provide a framework for probing their interconnections. A literature assessment and case studies show that the mechanisms between some pairs of pressures are better understood than others and the full triad of interactions is rarely considered. While challenges to evaluating these interactions are significant—including a mismatch in scales, data availability, and methodology—current approaches would benefit from expanding scientific cultures to embrace interdisciplinarity, and integrating animal, human, and environmental perspectives. Considering the full suite of connections would be transformative for planetary health by identifying potential for co-benefits, win-win-win scenarios, and highlighting where a narrow focus on solutions to one pressure might aggravate another.

We are experiencing profound planetary changes. The climate is now warmer than at any time in the past 125,000 years,1 extreme climatic events are more frequent,2,3 and global average temperature increases relative to the 1850–1900 average already exceed 1°C, and may top 1.5–2°C in the next two decades.4 Natural habitat is increasingly fragmented and intact fragments are decreasing in size.5 This twofold change, in climate and natural habitat, is shifting species distributions and rearranging the composition of ecological communities, and an estimated one million species are at risk of extinction.6 Simultaneously, we are witnessing widespread increases in emergence, spread, and reemergence of infectious diseases in wildlife, domestic animals, plants, and people.7–9 These major environmental trends are often attributed to common anthropogenic drivers, including pollution, deforestation, and agricultural expansion (Fig. 1). However, while meta-analyses draw focus to the strength of connections between disease and global change pressures of climate change and biodiversity loss,10 the science that mechanistically links all three is surprisingly lacking.

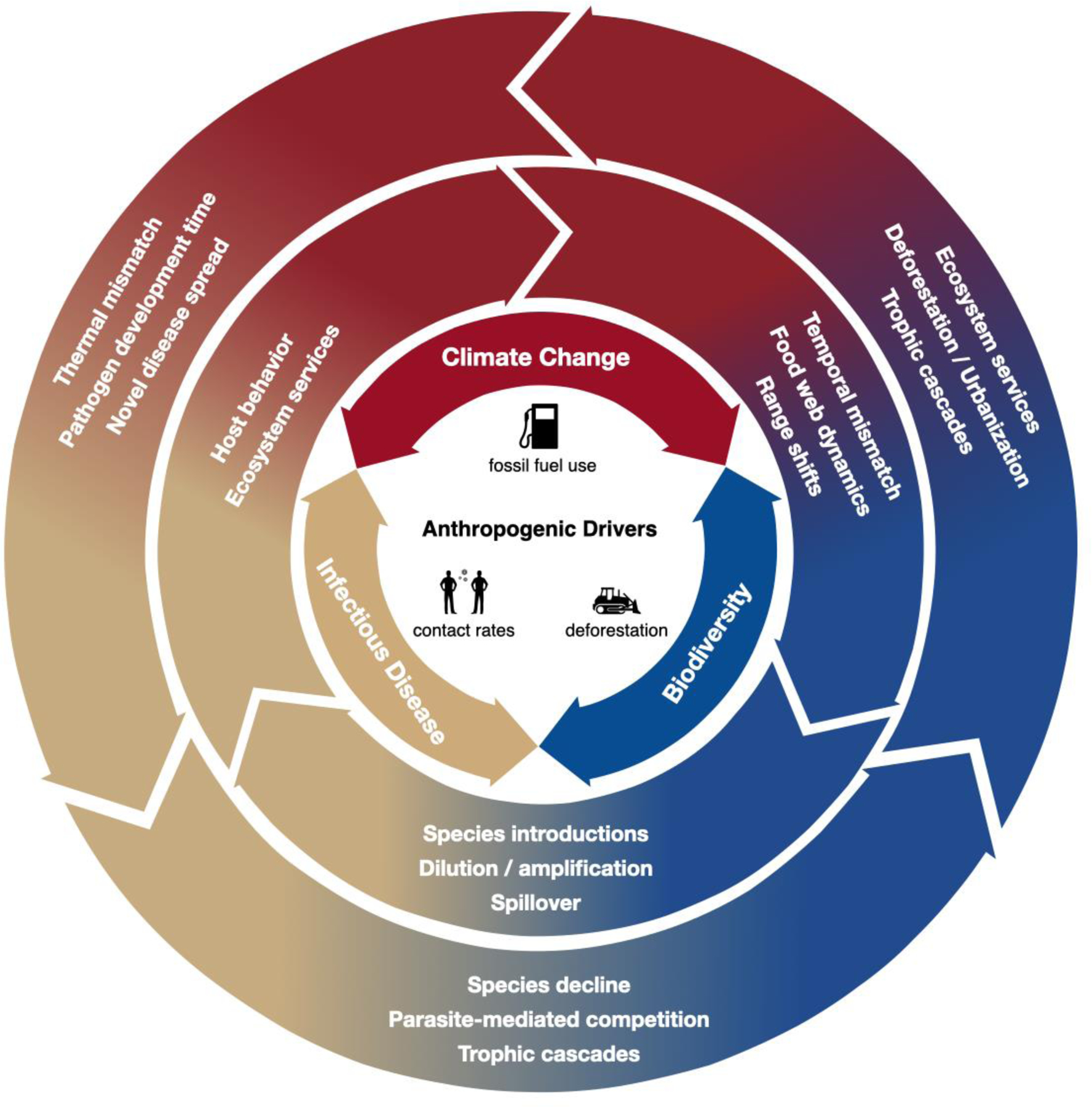

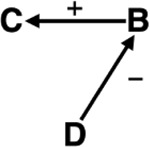

Fig 1: Directionality of mechanistic links between climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease.

Anthropogenic drivers, such as fossil fuel use, deforestation and agriculture, and human population growth, are accelerating increases in global temperatures, losses of biodiversity, and infectious disease outbreaks. These three global pressures can be connected mechanistically (examples listed in the two outer rings illustrate directional links, shown by arrows, between pressures) with cascading consequences. In addition to linear paths linking pressures, these mechanisms can lead to feedback loops between pressures, stepping from one ring to the next. Mechanisms match those identified in Table 1 and are discussed in more detail in the main text, but represent only a subset of the many possible mechanisms that connect pressures. The 2022 IPCC report provides examples of how the human system can be similarly integrated and connected to climate and biodiversity.

The connections between biodiversity loss and climate change have been highlighted in recent intergovernmental global assessments (e.g., Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services [IPBES], 6 Intergovernmental Platform on Climate Change [IPCC],4,11 IPBES-IPCC co-sponsored workshop report,12 United Nations’ Global Environmental Outlook [GEO],13 World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report [WWF]),14 establishing a process of identifying common drivers and responses to inform policy and solution pathways.15 The strong interconnections between infectious disease and biodiversity, and infectious disease and climate change are also increasingly well recognized.9,16–19 There is a pressing need to now investigate the expansion and effects of disease as primary and secondary drivers as well as a consequence of biodiversity-climate relations.16,20

The World Health Organization’s One Health initiative,21 IPCC, IBES, and GEO all recognize the need for a holistic approach to planetary health, but the three global pressures of climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious disease are rarely considered together (Box 1). We argue that considering the three pressures together is essential for identifying effective management solutions and win-win-win scenarios, and avoiding ecological surprises. For example, when implemented thoughtfully, nature-based solutions to manage biodiversity can have co-benefits of improving health and mitigating climate change (Box 2),22 but when designed poorly may result in trade-offs, such as climate mitigation policy supporting planting of non-native trees.23 Further, by investigating the interactions among pressures we can also gain new insights into system dynamics; for instance, amphibian declines could be explained by the interaction between temperature (extremes) and infectious disease, but not by either pressure alone (Box 2).24

Box 1. What is the current state of research on the triple crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious disease?

The biodiversity crisis: nature and biodiversity loss, encompassing the decline or disappearance of biological diversity, from genes to ecosystems.

The climate crisis: long-term shifts in the means and variances of temperatures and weather patterns (including shifts in seasonality, and incidences of extremes in climate variables as well as changes in spatial and temporal correlations among climate variables).

The crisis in infectious diseases: increasing frequency and prevalence of emerging infectious diseases in plants, animals, and people.

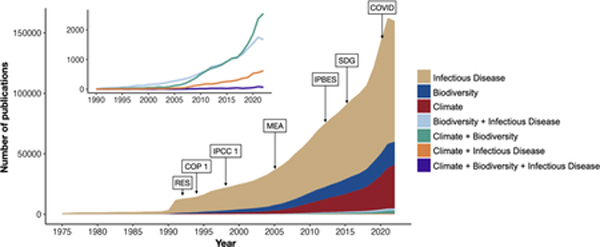

Number of publications retrieved for different combinations of search terms associated with biodiversity, climate change, and infectious disease research. Literature trends are based on Web of Science searches for terms related to climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease. Major events related to the study of climate change, biodiversity, or infectious disease are indicated: The Rio Earth Summit (RES) in 1992; the first Convention of Biological Diversity (COP 1) in 1994; the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 1) meeting in 1998; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) published in 2005; the formation of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2012; the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) published in 2015; and COVID-19 (COVID) became pandemic in 2020. Literature reflecting pairwise and three-way combinations of search terms are highlighted in the inset.

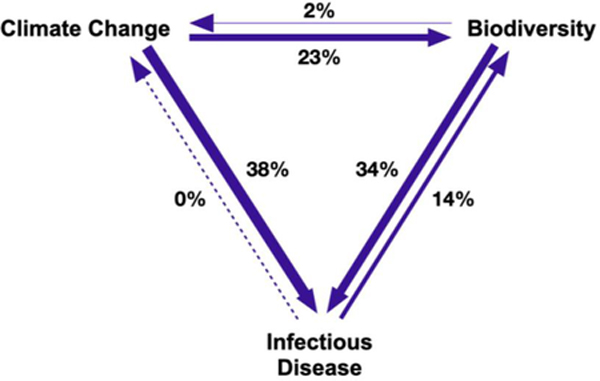

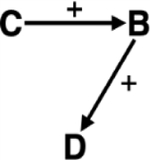

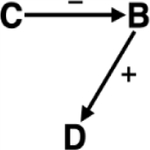

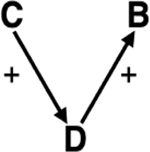

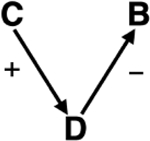

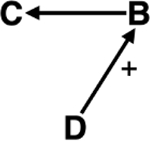

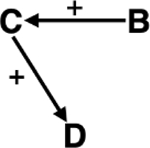

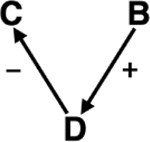

Number of publications that discuss mechanistic links between biodiversity, climate change, and infectious disease. Mechanistic links describe a process by which one global pressure drives another. Mechanisms were identified through our reading of the literature, including the papers cited in Table 1, and are consistent across Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Table 1. Arrows illustrate the direction of mechanistic links between pressures; arrow width is weighted by relative number of publications (percent of the 128 publications is noted next to each arrow), as a proxy for research effort.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We conducted a series of literature searches via the Web of Science Core Collection for publications between 1975–2022 using key search terms to identify papers on biodiversity, climate change and infectious disease (see Supplementary Methods for full details of search criteria). Our search returned 1,878,560 primary research and review articles. Among individual drivers, infectious disease had the most publications (1,347,124), followed by climate change (282,122), and then biodiversity (235,048). Unsurprisingly, there has been an increase in the number of infectious disease studies in the past 10 years, and we detect a ‘COVID surge’ represented by a 33.3% increase between 2019 and 2021. Pairwise combinations of these global pressures returned far fewer publications: infectious disease and biodiversity (17,580), biodiversity and climate change (17,652), and infectious disease and climate change (4,751).

We identified 505 studies that matched our search terms for biodiversity and climate change and infectious disease within a single publication’s title, abstract, or keywords. Within this intersection, we found that few studies (n = 128, 25.3%) discuss mechanistic links (see Supplementary Methods) connecting climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease. Only 29 papers (5.7%) quantified measures of climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease, and seven of these were on a single disease system, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, the causative agent of chytridiomycosis in amphibians.

Undoubtedly, some relevant papers were missed because of our choice of search terms (e.g., we did not include more general terms such as “temperature”, “abundance”, or “disease” because these are often used in contexts other than the three pressures of focus in this synthesis); however, the overall proportion of papers that intersect axes of each global pressure is unlikely to be greatly impacted by their exclusion – few papers consider pairwise terms, fewer still consider all three, and those that do tend to focus on a single study system.

Box 2. Connecting climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease.

Malaria: Climate → Biodiversity → Infectious Disease

Human malaria, which results from transmission of Plasmodium parasites by Anopheles mosquito vectors, involves multiple vector and parasite species with varying climate responses and contributions to disease transmission.113–115 Vector biodiversity affects malaria transmission through interspecific variation in competence, feeding behavior, and seasonality.115–118 For example, the presence of species that can aestivate during the dry season sustains high malaria transmission in arid climates such as the Sahel desert,119 and both high abundances of anthropophilic vector species and co-occurrence of dry and rainy season vectors have been associated with increased disease prevalence in Kenya.120,121 Similarly, the presence and abundances of Plasmodium species with dormant life stages (e.g., P. vivax) and alternative hosts (e.g., P. knowlesi) can affect long-term transmission dynamics through parasite reactivation and spillover events, respectively.116,122–125 Climate has complex, nonlinear relationships with vector and parasite species distributions and life history traits that contribute to disease transmission.126,127 Precipitation impacts the availability and stability of aquatic breeding habitat required by mosquitoes,128,129 and temperature impacts vector and parasite development rates as well as vector survival, lifespan, reproduction, and biting rates that determine contact rates between infected and uninfected hosts and vectors.84,126 These climatic influences are reflected in malaria incidence patterns that follow rainfall and temperature gradients and seasonality,130 and generate complex nonlinearities that are not well-captured by simple linear models.84,131 Critically, ignoring the diversity of Anopheles vectors, which are each characterized by distinct temperature dependencies (influencing developmental rates, biting rates, fecundity etc.), could shift forecasts of both the magnitude and direction of temperature effects on disease prevalence.84

Amphibian declines: Climate → Infectious Disease → Biodiversity

Chytridiomycosis, a disease caused by the pathogenic chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, Bd,132,133 is known to infect over 1000 amphibian species, many of which are considered Threatened by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.134 The disease has resulted in mass mortality and amphibian biodiversity declines globally.135,136 Climate change has multiple points of impact, including on host abundance, disease prevalence, and pathogen transmission.137–139 However, responses of Bd to temperature vary across species,140 life stages,141 and pathogen isolates.142 For example, there is empirical evidence for increased Bd prevalence in cold-adapted systems under unusually warm temperatures (and vice versa)—c.f. thermal mismatch hypothesis89 (but see 143)—driving amphibian declines in some warming habitats. Disease-driven declines in amphibians were thus only revealed when examining the interaction between climate (temperature extremes) and pathogen presence, whereas considering either in isolation fails to capture the critical dynamics underlying declines24. While this is one of the few systems where the links between climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease have been explored together, more work is needed on how the mechanistic links between chytridiomycosis and amphibian biodiversity will evolve over time.

Blue Carbon: Infectious Disease → Biodiversity → Climate

Vegetated marine ecosystems often support high biodiversity and productivity144,145. These biodiverse regions provide critical ecosystem functions including water purification, maintenance of fisheries, and carbon sequestration.146–148 Radiocarbon dating in mangrove soil, salt marshes, and seagrass indicates that these ecosystems can store carbon for thousands of years.149–153 However, biodiversity loss due to changes in marine and land use (e.g., aquaculture and urban development) can release stored carbon—transforming them into a carbon source.154,155 The degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems is estimated to release 0.45 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year.156 Disease is one of several factors exacerbating biodiversity loss and decline in these productive ecosystems. Eelgrass wasting disease, for example, has caused large declines in eelgrass density across locations and time,157–159 which reduces the habitat quality of eelgrass beds supporting coastal biodiversity. Recent epidemics have been linked to increased temperatures.159,160 The interactions between climate change and ecosystem health in these systems thus creates a vicious cycle. Eelgrass habitat degradation releases stored carbon, which contributes to further climate change and climate related stressors—increase in air temperature, ocean acidification, sea level changes—feeding back to further degrade these biodiverse ecosystems directly, and indirectly through altered disease outbreaks. In addition, because eelgrass growth is lower in disease-impacted systems, the ability to sequester carbon is also reduced, and ignoring disease status could mislead global estimates of Blue Carbon storage capacity.161

Here, we elucidate the interactions amongst the three global pressures of changes in climate (encompassing shifts in the means, variability, seasonality, and incidences of extremes in climate variables as well as changes in spatial and temporal correlations among climate variables), biodiversity sensu lato (defined as “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”, following the Convention on Biological Diversity), 25 and infectious disease. Using case studies to illustrate the causal pathways between them (Table 1), we demonstrate that the mechanisms between some pairs of pressures are better understood than others and that the body of research addressing all pairwise interactions is growing rapidly (Box 1). We highlight that (i) the pairwise interactions between biodiversity and infectious disease have been extensively studied, although underlying mechanisms remain hotly debated, and (ii) climate variability and change has major impacts on both biodiversity and disease, while (iii) the paths from biodiversity and disease to climate are less frequently observed and likely to be weak, at least over the timescales that define the Anthropocene. We discuss how our understanding of the connections among these three global pressures can be enhanced by bridging across scales and research disciplines, benefitting ecosystem and human health. Finally, we identify outstanding research questions to help advance science at this interface.

Table 1.

Case studies illustrating mechanistic links connecting climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease. A) Climate → Biodiversity → Infectious disease B) Climate → Infectious disease → Biodiversity C) Infectious disease → Biodiversity → Climate D) Biodiversity → Climate → Infectious disease E) Biodiversity → Infectious disease → Climate F) Infectious disease → Climate → Biodiversity. Each pathway is discussed in further details in section Mechanistic Links.

| A) Climate → Biodiversity | Biodiversity → Disease | Case Study | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation & Food web dynamics | Dilution / Amplification | Elevated precipitation increases resource production, which in turn increases reservoir species richness and abundance, amplifying Lyme disease.201–206 |

|

| Addition of host species with low reservoir competence to a community with low species richness reduces Borrelia burgdorferi infection in nymphal ticks, and thus Lyme disease prevalence.207,208 | |||

| Vector population | Drought induced changes in water depth and patchiness, disrupting aquatic food webs, and control of larval mosquitoes by fish.209 The increase in mosquito populations210 and the concentration of avian hosts around remaining watering holes211 increases West Nile virus transmission. |

|

|

| Temporal mismatch | Migration | Climate induced shifts in the phenology of milkweed, leading to changes in Monarch butterfly migration, which acts as a filter for diseased individuals—disease prevalence is higher at the end of breeding season than at overwintering sites.212 | |

| Gradual climate change & Species introductions | Novel disease spread | Permafrost melt releases active bacteria and viruses from thawing carcasses, leading to anthrax outbreaks.95,213 | |

| Migration / Range shifts | Spillover | Change in migratory behavior of harp seals following increased sea ice melt, increased opportunities for disease spillover and outbreaks of phocine distemper.96,214–215 | |

| Dilution / Amplification | Sea ice melt alters the migration of caribou, a seasonal disease escape strategy. Increased contact between geographically separated ungulate species, facilitating spillover of diseases into communities that were previously isolated.96 | ||

| Extreme wetness and dryness decrease richness of insect-pollinated plants, reshaping the distribution of their pollinators.216 Increased length of pollinator foraging distances, and floral trait variation drive increases in pathogen transmission and disease intensity.217 |

|

||

| B) Climate → Disease | Disease → Biodiversity | Case Study | Pathway |

| Novel disease spread & Spillover | Trophic cascade | Severe storms and warmer water are associated with amoebiasis outbreaks in sea urchins.218 Mass mortality of sea urchins releases kelp forests from predation,219,220 increasing local species richness.221 |

|

| Thermal mismatch | Parasite mediated competition | Shorter winters favor temperature dependent growth of Geomyces destructans,222 which is linked to White Nose Syndrome (WNS) in bats.223 WNS reduces the abundance of dominant bat species in the community,224 favoring less dominant bat species. | |

| Extirpation | Cold-adapted and warm-adapted amphibian hosts are more susceptible to Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) fungus at relatively warm and cool temperatures, respectively.86 Bd infection has caused amphibian population declines and extirpation.135,136 |

|

|

| Climate related shifts in habitat suitability for white pine blister rust resulted in a decline in prevalence in arid regions and an increase in colder regions—causing extirpation.178 | |||

| Temperature & Physiology | Species decline | Temperature dependent virulence of Vibrio spp.,105 which are associated with coral bleaching and disease.225 Coral declines are associated with fish biodiversity loss.226 | |

| Warming temperatures increase the occurrence and severity of Ranavirus,227 a disease linked to mass mortality events and population declines in the common frog.228 | |||

| Behavior | Drought increased foraging distances in the blue orchard bee, resulting in the increase of parasitism rates by the blister beetle and subsequent species decline.229,230 | ||

| Development time of pathogens | Extirpation | Decreased larval development times of the lung-dwelling nematode, Umingmakstrongylus pallikuukensis, of muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) increases infection pressure,231 which cascades to elevated predation risk from polar bears.232 | |

| Novel disease spread & Spillover | Shifts in timing of end of the dry season when Ebola outbreak risk is highest.233–235 Mortality induced changes in local primate community assemblages.236,237 | ||

| C) Disease → Biodiversity | Biodiversity → Climate | Case Study | Pathway |

| Species decline / Extirpation | Ecosystem services | The loss of keystone and mesopredators due to Sea star wasting disease (SSWD) reduces kelp forest resilience.238,239 Loss of kelp forest could reduce potential to capture and store (blue) carbon.240,241 |

|

| Eelgrass wasting disease and loss of eelgrass beds159,242 may reduce potential carbon sequestration.243 | |||

| The chestnut blight fungus, native to East Asia, effectively removed a dominant forest tree in the Eastern US.177,244 The death and decay of mature American chestnuts resulted in a pulse of released carbon and removed an important carbon sink.245 | |||

| Haplosporidium nelsoni (MSX) influences shellfish populations, and epizootic outbreaks have led to large population declines.246 Oyster beds provide a range of ecosystem services, including habitat for fish, water filtration, and shoreline protection.247,248 | |||

| Trophic cascade | Rinderpest reduced herbivore density in the Serengeti. Decreased grazing released vegetation from top-down control and increased fires, shifting the habitat to a net carbon source.249,250 | ||

| Parasite mediated competition | Ecosystem services | Foliar fungal pathogens increase plant biodiversity by reducing above ground plant biomass.251 Reduced biomass may decrease ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration; however, more diverse grasslands are suggested to sequester more carbon.252 |

|

| D) Biodiversity → Climate | Climate → Disease | Case Study | Pathway |

| Deforestation | Development time of pathogens | Deforestation effects on microclimate may increase local warming, shortening the development time of Plasmodium falciparum within their mosquito vector, increasing malaria risk.253 |

|

| Urbanization | Development time of vectors | Land use change, industrialization, and replacement of vegetation with heat absorbing surfaces, such as roads and buildings, can lead to urban heat islands. 46,254–260 Warmer local temperatures can shorten the development time of disease vectors,261 increasing disease transmission.84 | |

| E) Biodiversity → Disease | Disease → Climate | Case Study | Pathway |

| Species introductions & Novel disease spread | Ecosystem services | Introduced non-native species and their pathogens, i.e., Cryptococcus fagisuga causing beech bark disease,261,262 can result in tree damage and death, reducing forest biomass and potential carbon sequestration capabilities.263 |

|

| Dilution / Amplification | Tree diversity has a hump-shaped relationship with pest diversity (at low tree diversity pests are amplified and at high tree diversity pests are diluted).264 Mountain pine beetle infestation reduces forest biomass and carbon sequestration capabilities. 265 |

|

|

| F) Disease → Climate | Climate → Biodiversity | Case Study | Pathway |

| Behavior | Ecosystem services | Parasitic plants, such as Striga hermonthica—a parasite of sorghum-–may modify their microclimate via high transpiration rates. 266 Forest microclimate influences soil microbial composition, impacting primary productivity, and plant communities. 267 |

|

| Climate-induced biodiversity decline (various mechanisms) | The mitigation strategies used at the emergence of COVID-19 (travel bans, social distancing, suspended industrial production) also mitigated climate change by decreasing daily CO2 emissions.110,111,268 |

Mechanistic Links

Climate Change → Biodiversity

Species may adjust to climate change by shifting in space (range shift) and/or time (phenology), thermal plasticity and/or acclimation and evolutionary adaptations.26–30 Rapid changes in local climate and extreme climatic events (e.g., heatwaves, floods, hurricanes) can result in local extirpations, and even global extinctions,31–33 reducing the richness of local communities. Climate induced range shifts beyond historical distributions can lead to novel community compositions without historical analogs,34 reshaping species interactions (Table 1A).

Climate change will restructure biological communities via multiple mechanisms. Changes in temperature and precipitation can impact resource production and the flow of energy through ecological networks (Table 1A). Warmer temperatures will additionally shift species thermal ecologies, decreasing generation times, increasing metabolic needs (Table 1A), changing dispersal patterns, and altering seasonal phenologies.35 These climate-induced changes can modify the strength of species interactions and the resilience of food webs,36,37 which could cascade to species extirpations.38,39

Biodiversity → Climate Change

In general, increases in biodiversity are associated with reducing the effects of climate change. For instance, more diverse and species rich natural forests and grasslands have higher carbon sequestering potential (Table 1C),40 reflecting the general positive biodiversity-productivity relationship.41,42 Conversely, the loss of biodiversity through deforestation reduces carbon sequestration, and simultaneously increases greenhouse emissions by increasing the plant biomass undergoing decomposition. Post-deforestation land is often used for agriculture or urban development, both of which contribute to global greenhouse emissions (17% and 60% of global greenhouse emissions respectively).43 Deforested lands left unmanaged typically undergo succession toward forest regrowth, but this secondary forest can have lower diversity, be more fire-prone, and provide fewer ecosystem services than primary forest (Table 1C).44,45

At local scales, changes in biodiversity due to loss of natural habitat, agricultural expansion, and urbanization can alter the microclimate (Table 1D). Urban areas have higher air and surface temperatures compared to surrounding areas—urban heat islands—due to their lack of vegetation and greenspace.46 Local extirpations that include the loss of a keystone species can have downstream effects that decrease the abundance of primary producers important for carbon sequestration (Table 1B). Much of the evidence to support top-down effects, in which the loss of consumer diversity results in reduced primary productivity and carbon sequestration, comes from the blue carbon (carbon stored in coastal or marine systems) literature, with ongoing debate on the role of blue carbon in climate change accounting.47 In terrestrial systems, the release of producers from top-down control can lead to greater biomass accumulation; however, during a temporary carbon sink, increased biomass can exacerbate wildfires, leading to a net increase in atmospheric CO2 emissions (Table 1C).

Biodiversity → Infectious Disease

Changes in biodiversity are often linked with a change in disease prevalence.48–53 Greater biodiversity can decrease (dilution effect) or increase (amplification effect) disease exposure and incidence.53–55 The amplifying and diluting effects of biodiversity on disease prevalence are complex, and likely capture multiple mechanisms, sometimes simultaneously.56 Changes in reservoir host populations, specifically the introduction of new reservoir species or the increase in abundance of existing reservoir species, can additionally increase the potential for novel disease spillover,57,58 while decreases in biodiversity can decrease pathogen prevalence if infected individuals die or migrate out of a population (Table 1A) or if key reservoir or vector species are removed. Similarly, changes in vector abundance, for example as a result of ecological release, species introductions, or climate induced range shifts (Table 1A), can also alter disease transmission, with either positive or negative effects on disease prevalence.59–61

In human-managed ecosystems, such as agricultural landscapes, a focus on enhancing productivity and efficiency has led to extensive planting of monocultures, vulnerable to disease outbreaks.62,63 In contrast, the practice of adding biodiversity (agrobiodiversity) can enhance agricultural productivity by reducing crop losses,64 for example, via the dilution effect. Increasing genetic or species diversity, specifically including disease-resistant host genotypes or promoting natural enemies of pests, can reduce the likelihood and severity of pathogen and pest outbreaks.65

Infectious Disease → Biodiversity

Infectious disease is a direct driver of biodiversity loss through species declines, local extirpation, and extinction.66 Infectious diseases can cause population declines by reducing the development, fitness, and survival of their hosts (Table 1B), and pose a particular risk to already threatened and endangered species.67 In turn, species declines can cascade to wider community impacts through competitive release, the removal of top-down regulation, and the loss of foundational species (Table 1C).68 Disease can also manipulate the behavior of hosts.69,70 For example, parasites can modify host feeding behavior at infection (reviewed in 71), leading to increases (hyperphagia) or decreases (anorexia) in the uptake of resources.

Not all pathways linking disease to biodiversity are negative. Disease maintains or promotes biodiversity through indirect (parasite-mediated) competition or by occupying a critical role in a trophic cascade. Parasites increase biodiversity where frequency dependent parasitism increases intraspecific relative to interspecific competition—Janzen-Connell hypothesis72,73—and when parasites are more detrimental to competitively superior or more abundant species (Table 1C).74–76 There is increasing evidence that parasites can also function as the top predator in trophic networks, either by directly killing their hosts or indirectly by mediating host behavior, altering the flow of nutrients within and between habitats.77–79

Climate Change → Infectious Disease

The effects of climate change on infectious disease are well studied (see Box 1) but have largely focused on vector borne diseases. Climate change can have a direct impact on disease prevalence by altering physiological processes of the host—impacting immune activity—and the pathogens or their vectors—modifying generation times, development times, and fitness.19 Increases in temperature decrease generation times for pathogens and vectors, increasing disease spread and the potential for outbreaks (Table 1D).80,81 However, the effects of temperature on infectious disease are often nonlinear,82–84 and vary by parasite, host, and vector, depending on species’ thermal optima and disease ecology.85 Under the thermal mismatch hypothesis, parasites are suggested to have a broader thermal niche than their hosts, and thus should maintain thermal performance over a broader range of temperatures, driving outbreaks at temperatures at which host performance is diminished.86,87 In some systems, thermal performance curves indicate that climate change may reduce disease burden over longer timescales due to a lower survival probability of infected hosts at higher temperatures.88,89 Broader climatic shifts, such as changes in the length of a wet or dry season, can also alter disease dynamics by increasing or decreasing the time when the environment is suitable for transmission.86

In general, the relationships between climate change and non-vectored microparasites have been less well studied, in part, because of scale differences in dynamics (see Discrepancies in scale). Nonetheless, seasonal weather patterns might alter host behaviour and contact rates.90 Thus, shifts in seasonality due to climate forcing can drive shifts in infection dynamics for diseases such as cholera.91 Climate change can also impact more directly the spread of some airborne infections, such as chickenpox (varicella), through changes in humidity.92 Similarly, infection risk from fungal pathogens in plants is often closely linked to humidity or dew,93 and dispersal of spores can be strongly weather dependent.94

Gradual climatic shifts, including polar ice and permafrost melting, could lead to disease spread by releasing pathogenic fungi and viruses (Table 1A),95 and providing new opportunities for spillover.96 Hosts shifting distributions to track changing climate (see Climate Change → Biodiversity) increase the potential for disease spillover between previously geographically distant species.58,97,98 Climate-induced range shifts have been predicted for pathogen vectors,99,100 and shifting disease pressure with climate change has been the focus of much recent attention.101,102 However, in many systems it is unclear which climatic factors limit the distribution of hosts and parasites, making it difficult to generate robust projections.19,103,104

Extreme climate events, such as heat waves or deluges—modify disease pressure through induced stress responses and lowered host immunity. Extreme heat and drought can additionally have indirect effects on host immunological competence via, for example, food shortages.105 Extreme climate events also impact transmission dynamics. For instance, in water limited environments, droughts lead to more hosts congregating around scarce water sources, facilitating transmission of waterborne or environmentally transmitted diseases (Table 1A), and flash floods that cause damage to wastewater and potable water infrastructure may increase the transmission of waterborne pathogens in people.106

Infectious Disease → Climate Change

Evidence for direct mechanistic links by which infectious disease alters climate is generally lacking. Here we speculate on some possible associations (Table 1F). Disease can modify the greenhouse gas emissions of wild and domestic animals, for example, livestock infected with helminths release more methane than their unparasitized conspecifics,107,108 but it is difficult to know whether such relationships generalize or scale to a magnitude likely to affect the global climate. In human systems, healthcare has a large and expanding carbon footprint;109 however, when infectious disease occurs at a larger scale, as was the case for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, policies put in place by governing bodies (e.g., stay-at-home orders, travel bans) could reduce transport related CO2 emissions.110–112

We have highlighted some of the many pairwise links between climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease. There are varying degrees of empirical evidence for different links (Table 1), and the mechanisms between some pairs of pressures are better studied than others, but the volume of research linking pressures is growing (Box 1). These pairwise mechanisms are often intricately interconnected, resulting in feedbacks and chains of interactions, as we illustrate in the case studies presented in Box 2; however, they are rarely studied together.

Key challenges to connecting climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease

What prevents studies of climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease connectedness? Some impediments likely relate to research pedagogy, while other barriers reflect the practical challenges of working with complex systems, and access to funding to support interdisciplinary research. Ecosystems are complex, dynamic, and nonlinear. The current literature addressing the mechanistic links among all three pressures thus comprises a tangled web of empirical, conceptual, and synthetic studies, encompassing diverse taxa and a myriad of ecological processes (Fig. 2). Changes in infectious disease, climate, and biodiversity are often impossible to experimentally manipulate at large scales. Most research investigating interactions among all three is observational or based on natural experiments, and interactions are intrinsically difficult to analyze and interpret.

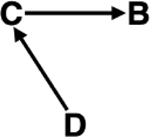

Fig. 2: Classification of literature that discusses mechanistic links between all three pressures: climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease.

Summary of the 128 studies that discuss climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease. Each study was scored for publication type, ecosystem (focal habitat), taxon (focal organism), and mechanisms. The study specific mechanisms described in each publication were assigned to the broader mechanism categories discussed in this synthesis (Table 1). For example, studies that describe general increases in temperature and precipitation were included in the ‘gradual climate change’ mechanism, whereas studies on extreme heatwaves were included in ‘climatic pulse events.’ Line width represents the number of studies (n = 128). Further details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Multiple axes of variation

Climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease are measured in multiple ways, operationally tailored to specific questions. For example, numerous climate variables and their means, variability, and extremes can be calculated. Measures of biodiversity and disease are equally multifaceted,162 and indicators of connectedness amongst the three must consider unit scales ranging from local microclimate measures (e.g., °C, millimeters, meters/second) to indicators of decline and health in species biodiversity (e.g., species richness, Shannon’s entropy, Simpson’s Index, phylogenetic diversity, He, IUCN Red List classification) to transmission rates and measures of disease epidemiology (e.g., susceptible populations, infected individuals, recovery rates, R0). Even when units are compatible, collecting data in overlapping places and times can be difficult, though the increasingly widespread availability of remotely sensed environmental data and global databases of species occurrences is improving the outlook (see Overcoming Barriers to Research).

Nonlinearity

Trends describing human-caused changes to the environment are non-linear. The growing impact of humanity on the Earth System—interacting physical, biological, and chemical processes—over the last seven decades has been described as the Great Acceleration.163 It is perhaps unsurprising that biological responses to these changes also show nonlinearities. For example, phenological responses to recent warming appear to be slowing down164 (but see 165), and temperature effects on biological rates—metabolic functions, life history, etc.—are frequently described by non-linear curves that vary among species and traits.166,167 Linear predictions will, therefore, often fail. Common machine learning tools, such as Random Forest, Neural Networks, and Support Vector Machines allow the fit of complex non-linearities, but mechanistic models that capture underlying biological and physical process will be required for making predictions beyond the training data that informs them, critical for robust future forecasting.82,168,169

Complex Systems

The nexus of climate change, biodiversity of ecosystems, and the transmission of infectious diseases presents a complex system that confounds long-term predictability. Complex systems are networks of components without central control that can give rise to complicated behaviors.170 Critically, complex systems exhibit emergent and self-organizing behaviors that usually cannot be anticipated simply by understanding the properties of the constituent parts. The climate system is recognized as a complex system.171 Simulations of Agent-Based Models (ABM) are one approach to modeling complex systems. ABM models start with a set of beliefs about the rules governing the constituent sub-systems and simulate (rather than solve for) the possible trajectories of the system. However, there are significant challenges to using ABMs for forecasting, including lack of robustness to the underlying models, a tendency to overfitting, high computational cost and data demands, and scalability. Another approach, perhaps better suited to studying the climate, biodiversity, disease nexus, is to represent complex systems as sets of coupled nonlinear differential equations. Here the challenge is a lack of realism and the use of highly simplified models for the behavior of the individual parts. However, more recently developed machine learning tools, such as symbolic regression172 and physics-informed neural networks173, allow for the construction of more complex nonlinear dynamical systems models informed by data (rather than theory).

Discrepancies in scale

A mismatch in the temporal and spatial scales at which relevant mechanisms act creates an additional barrier to studying the three-way interaction between pressures. Changes in biodiversity and infectious disease prevalence are commonly measured at the community and population levels, respectively, at time scales of months to years and spatial scales of meters to hectares14,174. The large interannual and spatial variability in climate leads most estimates of climate change to be measured at time scales of decades and large spatial scales, and complex processes shape how climate change filters down to alter the microclimates organisms experience3,175. If pressures interact at different scales, then it is also likely that no single scale will capture their full impacts.176

Because of this scale mismatch, it is unsurprising that the bidirectional interactions between biodiversity changes and infectious disease prevalence have been more thoroughly investigated, whereas the tripartite of interacting pressures including climate change are only rarely considered (Box 1). However, there is strong support for both the independent pairwise interactions between biodiversity and infectious disease, and between biodiversity and climate change (Table 1A). Further, if changes in infectious disease prevalence or biodiversity are widespread, then their effects will be felt at much larger time scales, such as the wholesale elimination of the American chestnut in eastern U.S. forests due to blight177 and ongoing climate-driven impacts of white pine blister rust on western U.S. forests,178 narrowing the mismatch in scales. But whether these effects propagate to impact the climate system will depend on the unique role of extirpated species in their ecosystems. In the chestnut example, above, if functionally similar species (e.g., oaks and maples) perform the roles previously played by the lost elements of biodiversity (i.e., chestnuts), then there are limited large-scale effects on the climate system, despite large effects at the community and ecosystem scales.

Of course, interactions between climate change (operating at large scales) and infectious disease or biodiversity dynamics (operating at finer scales) can also be affected through local environmental conditions created by the larger climate system. For instance, a warming climate can change the average temperature experienced by disease vectors, impacting growth rates and carrying capacity, with implications for disease transmission (Table 1B). Similarly, climate-induced range shifts can alter population abundances and local community composition, as documented in Thoreau’s woods (Table 1A).179 Thus, processes that propagate down from the climate system to biodiversity and disease transmission are both more prevalent and easier to detect than interactions of biodiversity and disease transmission that propagate up to the climate system.

Multi-scale modeling provides a key methodology for better understanding the up-scaling and down-scaling of interactions. In multi-scale models, the dynamical transitions among states are commonly solved at two different space and time resolutions.176,180 Changes in the fine-grained scale (here, changes to biodiversity and infectious disease prevalence) are studied at a high resolution and then aggregated to provide average changes of state that are relevant to the dynamics of the coarse-grained system. Solutions of the coarse-grained system are then obtained to provide initial states and boundary conditions for the next solution of the fine-grained system.

Expanding research cultures

Current methods of research and education on climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease do not facilitate thorough understanding of three-way interactions. Attempts to broaden cultures, as also advocated in the 2022 report by the IPCC,11 and integrate animal, human and environmental perspectives are captured in the One Health181 and Planetary Health182 approaches.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s One Health approach acknowledges the climate-biodiversity-disease interface: prioritizing local, regional, and global workshops on disease emergence, connectedness of zoonotic spillover, likelihood of significant impact on animal and human health, and coordination of medical networks. However, gaps remain, for example, disease prioritization in the United States—with priority diseases including rabies, salmonellosis, West Nile, plague, and Lyme disease—recognizes shifts in range distributions attributed to habitat losses and fragmentation, yet climatic effects are not factored in.183 Extensive policy plans that are in the works, such as The One Health Joint Plan of Action, with commitment of the Quadripartite organizations (Food & Agriculture Organization [FAO], United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], World Health Organization [WHO] and World Organisation for Animal Health [WOAH]), advocate for the joint consideration of animal, human and environmental health systems; but we show that the science has been lagging and the integration of climate impacts and feedbacks remains ambiguous.

A shift to Planetary Health thinking acknowledges that improvements in human health over the past century have come at an environmental cost, achieved through unsustainable exploitation of natural resources.182 While many concepts central to Planetary Health are not new, by explicitly recognising the interconnections between climate, biodiversity, and human health, Planetary Health is a call for greater collaboration across disciplines and national boundaries. To be successful, however, funding bodies need to recognise and support such collaboration.

Other Challenges

While we have highlighted some of the key challenges to considering the intersecting pressure of climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious disease, our list is far from comprehensive. In addition, each pressure is accompanied by its own unique list of challenges. Studies of infectious disease can be limited by restrictions on data sharing, disease incidence is frequently underreported or biased, with different reporting standards over space and time, historical records are often sparse, and seroprevalence data can be unreliable. Studies of biodiversity change are difficult to compare because our indices often measure different axes of biodiversity, we still lack data for most species, many of which have yet to be described, and ecological forecasting is still in its infancy. Climate change science has progressed rapidly over recent decades, and advances in climate change attribution have been particularly useful in communicating impacts; nonetheless, working with data from climate models is not straightforward for non-experts, forecasts come with large uncertainties, the temporal resolution of model projections does not necessarily match to species life cycles and activity patterns, and we are better at modeling some climate attributes (e.g. mean temperatures) than others (e.g. weather anomalies and extremes).

Overcoming Barriers to Research

Challenges to evaluating the interactions amongst climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease remain significant. Interdisciplinary collaboration will be increasingly important, as the expertise required, for example, on species identification and environmental sensing, is often not available within a single research group. However, differences in methodology, statistical frameworks, corpus of literature, and even language present barriers to effective interdisciplinary research.184 There is additionally a need for data that can be integrated across scales, capturing nonlinear effects and feedback loops, and which can be projected forward in time. For instance, there is debate in biodiversity and climate change research about what types of data are needed to detect climate change effects,185,186 in infectious disease and biodiversity research on both what data and scale are best to evaluate relationships,52,53 and in climate change and infectious disease research on how to integrate nonlinear effects of temperature along with other concurrent drivers of disease dynamics.84,90

Addressing the intersection of climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease will require appropriate field observational data for all three pressures, collected at relevant time and spatial scales, paired with experiments and mechanistic models (Fig. 3). Global efforts, such as Global Biodiversity Information Facility [GBIF], Group on Earth’s Observations Biodiversity Observation Network [GEO BON], Global Forest Watch, Integrated Ocean Observing System [IOOS], National Ecological Observatory Network [NEON], and Ocean Biodiversity Information System [OBIS], provide useful examples of large-scale data collection and curation. Citizen science data (e.g., USA National Phenology Network and eBird), distributed experiments (e.g., Nutrient Network [NutNet]), and Indigenous knowledge networks187 represent novel and increasingly important types of information, but such data remain undervalued and need to be better integrated.188

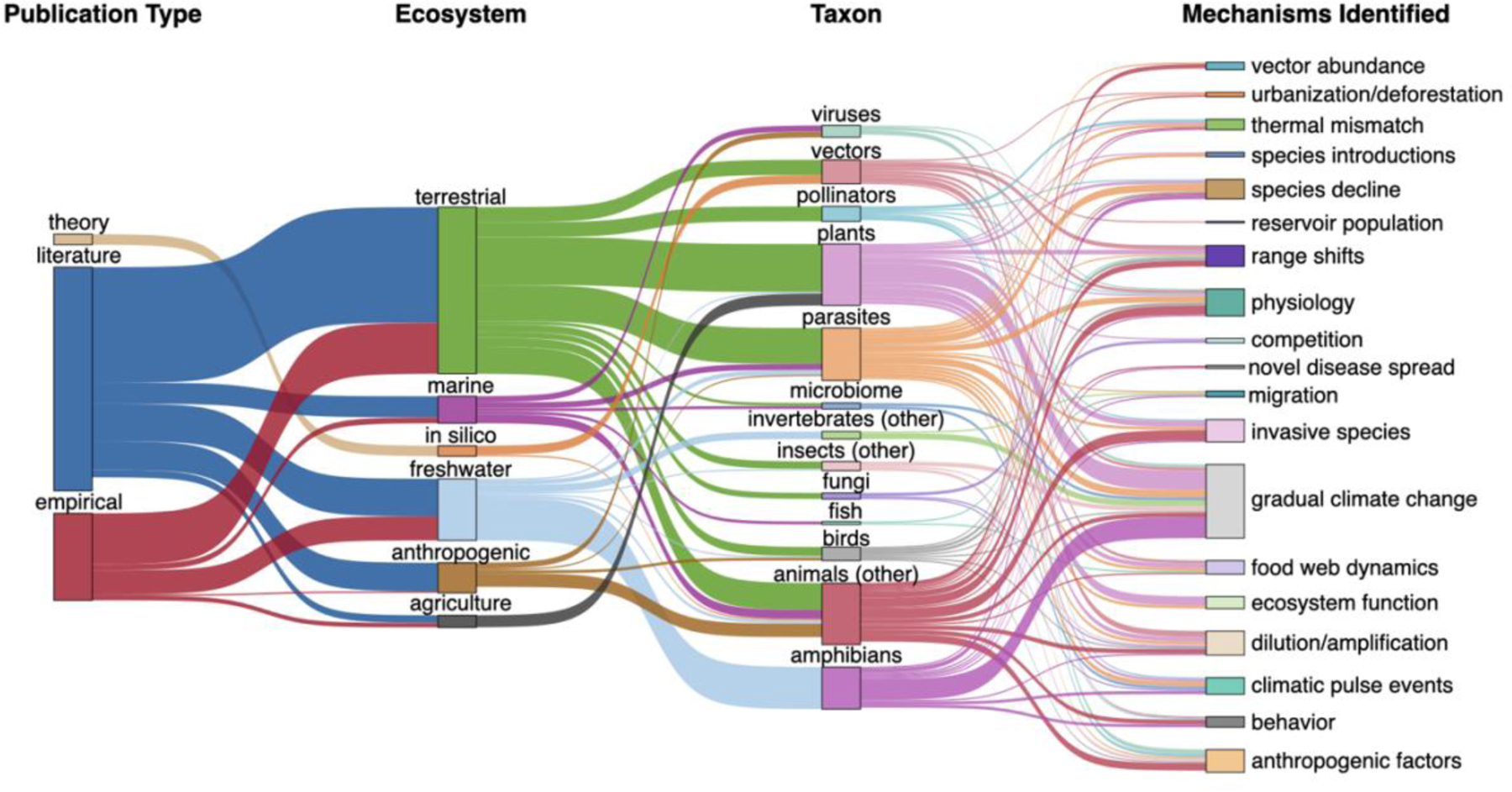

Fig. 3: Schematic illustrating mechanisms underlying key pathways and feedbacks linking between biodiversity, disease dynamics and the climate system (numbers), and the research tools and data types that allow us to quantify them (letters).

Climate determines rates of primary productivity (central arrow). Warming temperatures and CO2 fertilisation (1) accelerate plant growth (2) and the timing of annual life cycle events (3). Increased plant growth sequesters atmospheric CO2 (4), but warming soils elevate respiration and decomposition rates of soil microbes (5) which releases CO2 back into the atmosphere. Increased biodiversity enhances ecosystem productivity (6), and thus rates of CO2 fixation. Pests and disease can regulate and maintain biodiversity through Janzen-Connell effects (7) while biodiversity can modify disease outbreaks through the dilution effect (8). General climate circulation models (A) and synthesis reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provide projections of likely climate responses to variation in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Remote sensing using satellites and drones (B) allows for real-time monitoring of plant phenological responses (C) to changes in climate and associated changes in vegetation structure (D). Remote sensed data and ‘on the ground’ biodiversity surveys (E) inform ecological forecasts (F) in combination with species distribution modelling (G). Experimental manipulations, such as experimental warming (H), and new genomic tools (I) that can detect evidence of selection provide quantitative measures of species’ adaptive and plastic potential to environmental changes. Nature-based solutions (J), including tree planting (see The Bonn Challenge: https://www.bonnchallenge.org/), provide potential for win-win-win scenarios, but only if enacted thoughtfully. See Table 1 for citations. We use a terrestrial forest ecosystem as example to illustrate system complexity; equivalent schematics could be generated for marine and freshwater ecosystems. We do not show interactions with the socio-economic system, including feedbacks with public health policy, disease surveillance, clean energy pathways etc. which would add further complexity.

Ultimately, we need to expand research frameworks to truly integrate climate and habitat changes, wildlife conservation, food security, and modern agricultural practices, considering both their direct and indirect effects, as well as the feedbacks and nonlinearities in the pathways that connect them. Expanding course curricula to advance core competencies (e.g., integration of animal, human, and environmental sciences, and application of research to policy, public health and clinical programs),189 while supporting interdisciplinary hiring clusters, and research coordinated networks, will provide part of the solution.190 In addition, we must motivate experts to “transgress” outside of their given expertise, to build on, and carry over inherent strengths to other fields. For example, predictive, analytical models that are not typically applied in clinical areas of veterinary sciences would extend methods and concepts from ecology and environmental sciences. Likewise, advances in medical and veterinary fields, alongside their more immediate solutions focus, provide important grounding for ecological theory and practice.

Outlook and Future Directions

There is growing urgency for major global action on climate change, biodiversity, and infectious diseases, and the international community has responded. The 2022 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), highlighting widespread human and environmental impacts of climate change that are already occurring and which are expected to accelerate without extreme and rapid changes in carbon emission mitigation, inspired calls for international policy shifts at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP27). The 2022 meeting of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) resulted in the unprecedented commitment to protect 30% of land and sea area by 2030 by participating countries; an action considered essential for safeguarding Earth’s remaining biodiversity. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic encouraged the establishment of various international pathogen surveillance and pandemic prevention initiatives (e.g., WHO’s Global Genomic Surveillance Strategy191). These combined efforts look to address the primary crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious disease, and increasingly the connections between them.11,12 By recognizing their interconnectedness, there is an opportunity to identify shared drivers and develop sustainable solutions with multiple co-benefits (see Box 2).192,193 However, doing so requires new approaches to scientific research and communication across disciplines.

Given the challenges, how can we advance research and policy at the interface of climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease? Researching the interactions of all three global pressures is certainly more complex than studying them individually or in pairs; yet, elucidating the full connectedness of climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease may be possible through integrating theory and data across temporal and spatial scales using data-driven models. Such efforts could be transformative for planetary health, allowing the identification of win-win-win scenarios (e.g. compared to continued planting of fast growing tree monocultures, preserving older and more biodiverse forests stores more carbon and increases resistance to climate extremes and disease23) and, conversely, highlighting where a focus on solutions to one pressure can aggravate another (e.g. tree planting in ancient grasslands to mitigate climate drives biodiversity loss and likely overestimates net carbon benefits194).

Empirical research that considers the mechanistic links amongst all three global pressures is currently aggregated in a few well-studied systems—amphibian chytridiomycosis, forest health, and Lyme disease. For instance, chytridiomycosis in amphibians comprises approximately a quarter of the studies we identified that jointly address climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease measures (Box 1). Although we undoubtedly missed some relevant literature, our analysis considered over 1.8 million publications, and demonstrates the relative rarity of such integrative research. While these few well-studied systems provide useful case studies, there is an urgent need to expand beyond them. Encouragingly, we show that there is already a substantial body of research addressing many of the pairwise connections (Table 1). We suggest, however, that Table 1 presents more than a list of case studies; it serves as a guide for mapping how all three global pressures can be mechanistically linked by identifying adjacent pathways.

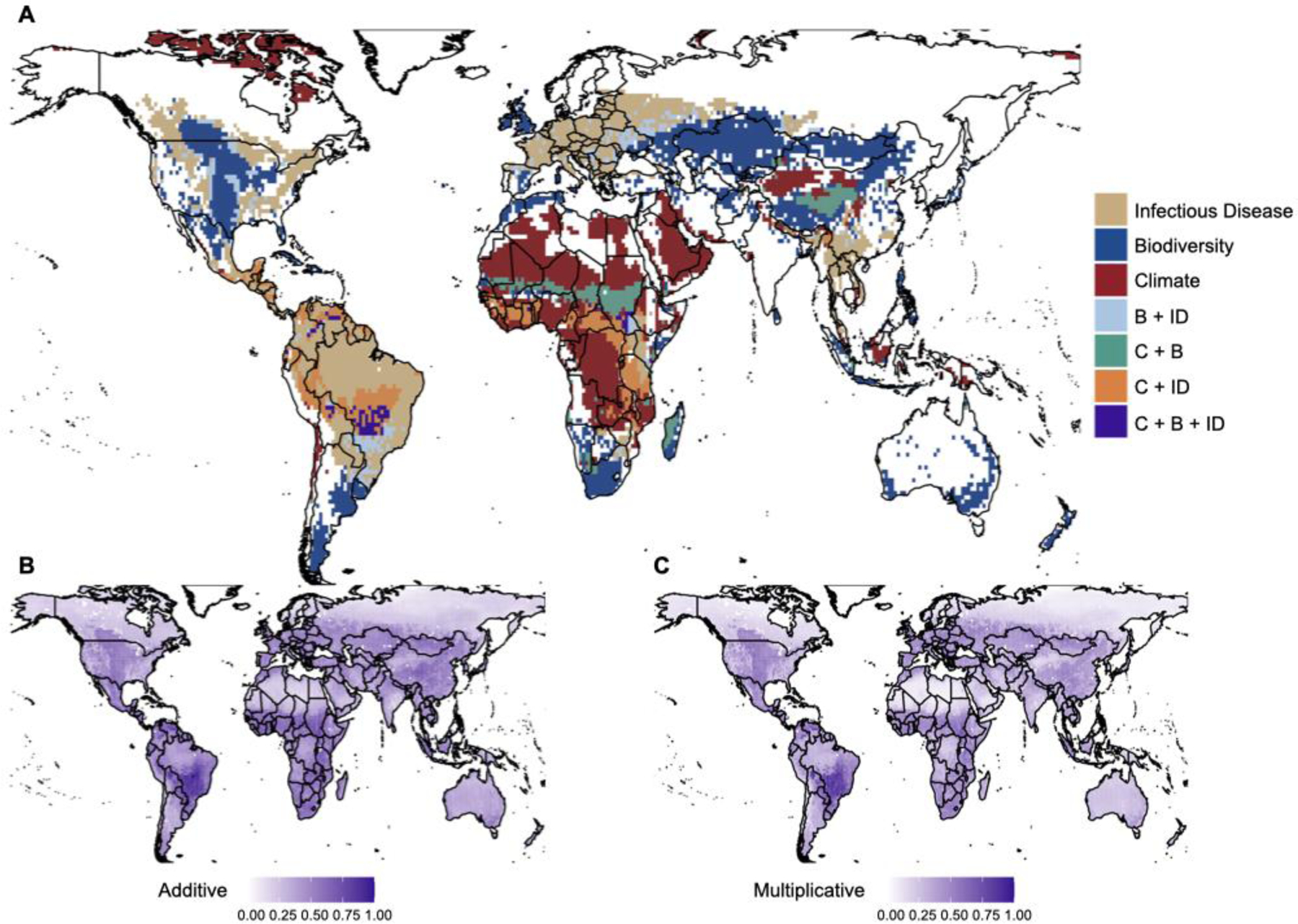

One approach for identifying where interactions between pressures could be important is to examine how they overlap in space or time. While each pressure can be characterized along multiple dimensions, by mapping the axes relevant to a specific mechanistic pathway on a common spatial or temporal scale, it is possible to then examine their intersection. For example, the intersection between climate and biodiversity loss might exacerbate risk of zoonotic spillover in central Brazil given the high richness of zoonotic hosts in that region, whereas low zoonotic host diversity might reduce risk of spillover in Australia, despite exposure to similar biodiversity loss and climate hazards (Fig. 4). Of course, such coarse scale approaches only provide a guide to potential interactions between pressures, and are unlikely to accurately capture dynamics for any one particular system; for example, the loss of biodiverse native forests in Australia has been linked to increased aggregation of bats in human-managed gardens, leading to spillover of Hendra virus to horses.195 Nonetheless, such approaches allow for scenario modeling, for example, contrasting additive versus multiplicative or threshold-type interactions (Fig. 4A–C). Improved data at appropriate scales coupled with a mechanistic understanding of the connections among pressures would allow for more fine-grained predictions, such as shifts in transmission of mosquito-borne diseases with warming100,196,197 and impacts of the chytrid fungus, B. dendrobatidis, on global amphibian declines (see Box 2).24

Fig. 4: Visualizing how pressures overlap in space could reveal the potential for interactions between them.

Maps depicting geographical overlap of global pressures: climate risk (C), biodiversity risk (B), and infectious disease risk (ID). A) Pressure hotspots, defined as cells falling within the upper 20% quantile of each pressure; B) Global pressures combined additively (datasets rescaled to between 0 and 1); and C) Global pressures combined multiplicatively (datasets rescaled to between 1 and 2). Climate change risk is measured as the standard Euclidean distance across multiple climate metrics between a baseline (1995–2014) and future (2080–2099) period under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 2–4.5 scenario;198 Biodiversity is represented as the inverse of the Biodiversity Intactness Index (1-BII), which reflects the proportional loss of species richness in a given area relative to minimally-impacted baseline sites in 2005;199 Disease risk is represented by mammal zoonotic host richness,200 a measure of both biodiversity and zoonotic infectious disease burden. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

We have focused our review at the nexus of the intersecting pressure of climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious disease. We have outlined the benefits of considering these three pressures together, and some of the costs of failing to do so. Ultimately, there is a need to design solution pathways to jointly reduce pressures, and this will require coordinated efforts in science and policy.15 Below, we highlight outstanding questions to further advance the integration of climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease research, and address the combined pressures they pose to ecosystem integrity and human well-being. By better understanding the interactions among pressures, we can better map out the solution space. Identifying the most effective policy and socioeconomic levers to achieve (transformative) change will present new challenges at the interface of natural and human systems.6,11,12

Open questions to further our understanding of the interconnections among climate change, biodiversity, and infectious disease:

How can existing data sets be augmented to address the data gaps in our understanding of the mechanistic pathways linking climate, biodiversity, and infectious disease?

At what temporal and spatial scales are interactions between pressures most likely to arise?

Does the spatial coincidence of multiple pressures increase the likelihood of interactions?

Are the interactions between pressures mostly reinforcing or dampening?

Which are the climate axes, disease attributes, and dimensions of biodiversity that are most likely to drive, and be impacted by, three-way interactions among pressures?

What are the solution pathways that can be targeted by policy and management strategies to maximize co-benefits?

How might AI and new Machine Learning tools and data streams (genomics, remote sensing, social network analysis, etc.) contribute to improving models of the interactions among pressures?

How will future global change (e.g., climate change, human population growth and movement, and habitat transformation) shift interactions among pressures in addition to the intensity of the pressures?

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies and the UBC Biodiversity Research Centre for supporting author collaboration, and Chiyuan Miao for providing climate data. Sheila Allen, Jason Rohr, and two anonymous reviewers provided valuable feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Funding:

AP-B is supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant awarded to TJD. LB is supported by the National Science Foundation (DBI-1349865). JMD is supported by the National Science Foundation (DEB-220015 and DEB-171728) and National Institutes of Health (NIH Al156866). JF was supported by the Bing-Mooney Fellowship. MJF is supported by an NSERC PDF. A-LMG is supported by the Tula Foundation. EAM is supported by the National Science Foundation (DEB-1518681, with Fogarty International Center), the National Institutes of Health (R35GM133439, R01AI168097, R01AI102918), the Stanford King Center on Global Development, Woods Institute for the Environment, and Center for Innovation in Global Health. PS is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Al156866). JLG is supported by Binational Science Foundation grant #2021030 and the University of Georgia Foundation. TJD is supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant. Additional working group funding was provided by a GCRC grant to TJD through the Biodiversity Research Centre at UBC, and the UGA Foundation

Glossary

- Behavior

the way an organism acts, e.g., foraging, movement, social interactions

- Climatic pulse events

rapid changes in climate that occur over a short window of time.

- Deforestation

intentional clearing of forested land.

- Development time of pathogens

the progressive life history changes a pathogen undergoes in its lifetime.

- Development time of vectors

the progressive life history changes a pathogen’s vector (organism that transmits pathogens between humans and animals) undergoes in its lifetime.

- Dilution / Amplification

when the presence of a species in a population either dilutes or amplifies the transmission of pathogens.

- Ecosystem services

benefits humans obtain from nature, e.g., carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, and flood regulation.

- Extirpation

the loss of a species from a particular geographic area, local extinction.

- Food web dynamics

changes in flow or structure of the food chains in an ecosystem.

- Gradual climate change

slow and consistent changes in climate over time.

- Migration

regular and repeated movements between different areas of an organism’s home range.

- Novel disease spread

transmission of a new disease through a population.

- Parasite mediated competition

competition between two species driven by parasitism in one or both species.

- Physiology

referring to the physiological mechanisms of an organism, e.g., cellular and metabolic processes.

- Range shifts

a spatial change in the geographic distribution of a species.

- Species decline

decrease in habitat, geographic range, or population sizes of a particular species.

- Species introductions

the arrival of species into a new geographic area.

- Spillover

contact of a host population with pathogen propagules from another host population as a result of high pathogen abundance in a population where the pathogen can be permanently maintained, reservoir population.

- Temporal mismatch

misalignment of organismal processes or organisms in time. The temporal mismatch theory ties the fitness of an organism to the temporal synchrony of the offspring’s energetic needs and food source.

- Thermal mismatch

misalignment of temperature required for organismal processes. The thermal mismatch hypothesis suggests that smaller-bodied parasites will generally be favored over larger-bodied parasites due to their broader thermal niches and ability to quickly adapt to changing environmental conditions.

- Trophic cascade

reciprocal changes in the food web as a result of the addition or removal of a top predator.

- Urbanization

the process in which large numbers of people concentrate in proportionally small geographic areas.

- Vector population

the vector species that occupy a particular geographical area.

References

- 1.Tollefson J IPCC climate report: Earth is warmer than it’s been in 125,000 years. Nature. 2021. Aug 9;596(7871):171–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai W, Borlace S, Lengaigne M, van Rensch P, Collins M, Vecchi G, et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat Clim Change. 2014. Feb;4(2):111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NOAA. Annual 2021 Global Climate Report | National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202113 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad NM, Brudvig LA, Clobert J, Davies KF, Gonzalez A, Holt RD, et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci Adv 2015. Mar 20;1(2):e1500052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IPBES. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services [Internet]. Zenodo; 2019. May [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/6417333 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith KF, Goldberg M, Rosenthal S, Carlson L, Chen J, Chen C, et al. Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks. J R Soc Interface. 2014. Dec 6;11(101):20140950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife--Threats to biodiversity and human health. Science. 2000. Jan 21;287(5452):443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker RE, Mahmud AS, Miller IF, Rajeev M, Rasambainarivo F, Rice BL, et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022. Apr;20(4):193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahon MB, Sack A, Aleuy OA, Barbera C, Brown E, Buelow H, et al. Global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease [Internet]. bioRxiv; 2022. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. p. 2022.07.21.501013. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.21.501013v1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2023. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/climate-change-2022-impacts-adaptation-and-vulnerability/161F238F406D530891AAAE1FC76651BD [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pörtner HO, Scholes RJ, Agard J, Archer E, Arneth A, X. Bai, et al. IPBES-IPCC co-sponsored workshop report synopsis on biodiversity and climate change. IPBES and IPCC; 2021. p. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4782538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Environment UN. UNEP - UN Environment Programme. 2019. [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Global Environment Outlook 6. Available from: http://www.unep.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-6

- 14.Living Planet Report 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Available from: https://livingplanet.panda.org/

- 15.Pörtner HO, Scholes RJ, Arneth A, Barnes DKA, Burrows MT, Diamond SE, et al. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science. 2023. Apr 21;380(6642):eabl4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein AS, Ando AW, Loch-Temzelides T, Vale MM, Li BV, Li H, et al. The costs and benefits of primary prevention of zoonotic pandemics. Sci Adv 2022. Feb 4;8(5):eabl4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daszak P, das Neves Carlos, Amuasi John, Haymen David, Kuiken Thijs, Roche Benjamin, et al. Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Pandemics of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services | QUT ePrints [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 3]. Available from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/208149/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Climate change 2007: the physical science basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 976. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altizer S, Ostfeld RS, Johnson PTJ, Kutz S, Harvell CD. Climate change and infectious diseases: from evidence to a predictive framework. Science. 2013. Aug 2;341(6145):514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobson AP, Pimm SL, Hannah L, Kaufman L, Ahumada JA, Ando AW, et al. Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention. Science. 2020. Jul 24;369(6502):379–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FAO, UNEP, WHO, and WOAH. One health joint plan of action (2022‒2026): working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment [Internet]. Rome; 2022. [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Available from: 10.4060/cc2289en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colléony A, Shwartz A. Beyond assuming co-benefits in nature-based solutions: A human-centered approach to optimize social and ecological outcomes for advancing sustainable urban planning. Sustainability. 2019. Jan;11(18):4924. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seddon N, Chausson A, Berry P, Girardin CAJ, Smith A, Turner B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2020. Jan 27;375(1794):20190120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen JM, Civitello DJ, Venesky MD, McMahon TA, Rohr JR. An interaction between climate change and infectious disease drove widespread amphibian declines. Glob Change Biol 2018;25(3):927–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Convention on Biological Diversity [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 2]. The Convention on Biological Diversity. Available from: https://www.cbd.int/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams SE, Shoo LP, Isaac JL, Hoffmann AA, Langham G. Towards an integrated framework for assessing the vulnerability of species to climate change. PLOS Biol 2008. Dec 23;6(12):e325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valladares F, Matesanz S, Guilhaumon F, Araújo MB, Balaguer L, Benito-Garzón M, et al. The effects of phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation on forecasts of species range shifts under climate change. Ecol Lett 2014;17(11):1351–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pecl GT, Araújo MB, Bell JD, Blanchard J, Bonebrake TC, Chen IC, et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science. 2017. Mar 31;355(6332):eaai9214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuert CR, Marcoux M, Hussey NE, Heide-Jørgensen MP, Dietz R, Auger-Méthé M. Decadal migration phenology of a long-lived Arctic icon keeps pace with climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2022. Nov 8;119(45):e2121092119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGaughran A, Laver R, Fraser C. Evolutionary responses to warming. Trends Ecol Evol 2021. Jul 1;36(7):591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pörtner HO, Farrell AP. Physiology and climate change. Science. 2008. Oct 31;322(5902):690–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smale DA, Wernberg T. Extreme climatic event drives range contraction of a habitat-forming species. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2013. Mar 7;280(1754):20122829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDowell W g., McDowell W h., Byers J e. Mass mortality of a dominant invasive species in response to an extreme climate event: Implications for ecosystem function. Limnol Oceanogr 2017;62(1):177–88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams JW, Jackson ST. Novel climates, no-analog communities, and ecological surprises. Front Ecol Environ 2007;5(9):475–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Springate DA, Kover PX. Plant responses to elevated temperatures: a field study on phenological sensitivity and fitness responses to simulated climate warming. Glob Change Biol 2014;20(2):456–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sentis A, Hemptinne JL, Brodeur J. Effects of simulated heat waves on an experimental plant–herbivore–predator food chain. Glob Change Biol 2013;19(3):833–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartley TJ, McCann KS, Bieg C, Cazelles K, Granados M, Guzzo MM, et al. Food web rewiring in a changing world. Nat Ecol Evol 2019. Mar;3(3):345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunne JA, Williams RJ, Martinez ND. Network structure and biodiversity loss in food webs: robustness increases with connectance. Ecol Lett 2002;5(4):558–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilbert B, Tunney TD, McCann KS, DeLong JP, Vasseur DA, Savage V, et al. A bioenergetic framework for the temperature dependence of trophic interactions. Ecol Lett 2014;17(8):902–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osuri AM, Gopal A, Raman TRS, DeFries R, Cook-Patton SC, Naeem S. Greater stability of carbon capture in species-rich natural forests compared to species-poor plantations. Environ Res Lett 2020. Feb;15(3):034011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cardinale BJ, Matulich KL, Hooper DU, Byrnes JE, Duffy E, Gamfeldt L, et al. The functional role of producer diversity in ecosystems. Am J Bot 2011;98(3):572–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isbell F, Calcagno V, Hector A, Connolly J, Harpole WS, Reich PB, et al. High plant diversity is needed to maintain ecosystem services. Nature. 2011. Sep;477(7363):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.FAO. Emissions due to agriculture. Global, regional and country trends 2000–2018. FAOSTAT Anal Brief Ser 2020;Series No. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson TRH, Brown S, Murray L, Sidman G. Greenhouse gas emissions from tropical forest degradation: an underestimated source. Carbon Balance Manag 2017. Feb 14;12(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Andrade RB, Balch JK, Parsons AL, Armenteras D, Roman-Cuesta RM, Bulkan J. Scenarios in tropical forest degradation: carbon stock trajectories for REDD+. Carbon Balance Manag 2017. Mar 9;12(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akbari H, Pomerantz M, Taha H. Cool surfaces and shade trees to reduce energy use and improve air quality in urban areas. Sol Energy. 2001. Jan 1;70(3):295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macreadie PI, Anton A, Raven JA, Beaumont N, Connolly RM, Friess DA, et al. The future of Blue Carbon science. Nat Commun 2019. Sep 5;10(1):3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keesing F, Belden LK, Daszak P, Dobson A, Harvell CD, Holt RD, et al. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature. 2010. Dec;468(7324):647–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wood CL, Lafferty KD. Biodiversity and disease: A synthesis of ecological perspectives on Lyme disease transmission. Trends Ecol Evol 2013. Apr 1;28(4):239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Civitello DJ, Cohen J, Fatima H, Halstead NT, Liriano J, McMahon TA, et al. Biodiversity inhibits parasites: Broad evidence for the dilution effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015. Jul 14;112(28):8667–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young HS, Parker IM, Gilbert GS, Guerra AS, Nunn CL. Introduced species, disease ecology, and biodiversity–disease relationships. Trends Ecol Evol 2017. Jan 1;32(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halliday FW, Rohr JR. Measuring the shape of the biodiversity-disease relationship across systems reveals new findings and key gaps. Nat Commun 2019. Nov 6;10(1):5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]