Abstract

Citrus is an important genus in the Rutaceae family, and citrus peels can be used in both food and herbal medicine. However, the bulk of citrus peels are discarded as waste by the fruit processing industry, causing environmental pollution. This study aimed to provide guidelines for the rational and effective use of citrus peels by elucidating the volatile and nonvolatile metabolites within them using metabolomics based on headspace-gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–Q-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry. In addition, the antioxidant activities of the citrus peels were evaluated using DPPH radical scavenging, ABTS radical scavenging, and ferric reducing antioxidant power. In total, 103 volatile and 53 nonvolatile metabolites were identified and characterized. Alcohols, aldehydes, and terpenes constituted 87.36% of the volatile metabolites, while flavonoids and carboxylic acids accounted for 85.46% of the nonvolatile metabolites. Furthermore, (Z)-2-penten-1-ol, L-pipecolinic acid, and limonin were identified as characteristic components of Citrus reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan (PK), C. reticulata ‘Unshiu’ (CLU), and C. reticulata ‘Wo Gan’ (WG), respectively. Principal component analysis and partial least squares discriminant analysis indicated that C. reticulata Blanco ‘Chun Jian’ (CJ), PK, CLU, and C. reticulata ‘Dahongpao’ (DHP) were clustered together. DHP is a traditional Chinese medicine documented in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, suggesting that the chemical compositions of CJ, PK, and CLU may also have medicinal values similar to those of DHP. Moreover, DHP, PK, C. reticulata ‘Ai Yuan 38′(AY38), CJ, C. reticulata ‘Gan Ping’(GP), and C. reticulata ‘Qing Jian’(QJ) displayed better antioxidant activities, recommending their use as additives in cosmetics and food. Correlation analysis suggested that some polyphenols including tangeritin, nobiletin, skullcapflavone II, genistein, caffeic acid, and isokaempferide were potential antioxidant compounds in citrus peel. The results of this study deepen our understanding of the differences in metabolites and antioxidant activities of different citrus peel varieties and ultimately provide guidance for the full and rational use of citrus peels.

Keywords: Citrus peel, HS-GC-IMS, LC-Qtrap-MS, Volatile and nonvolatile metabolites, Antioxidant activity

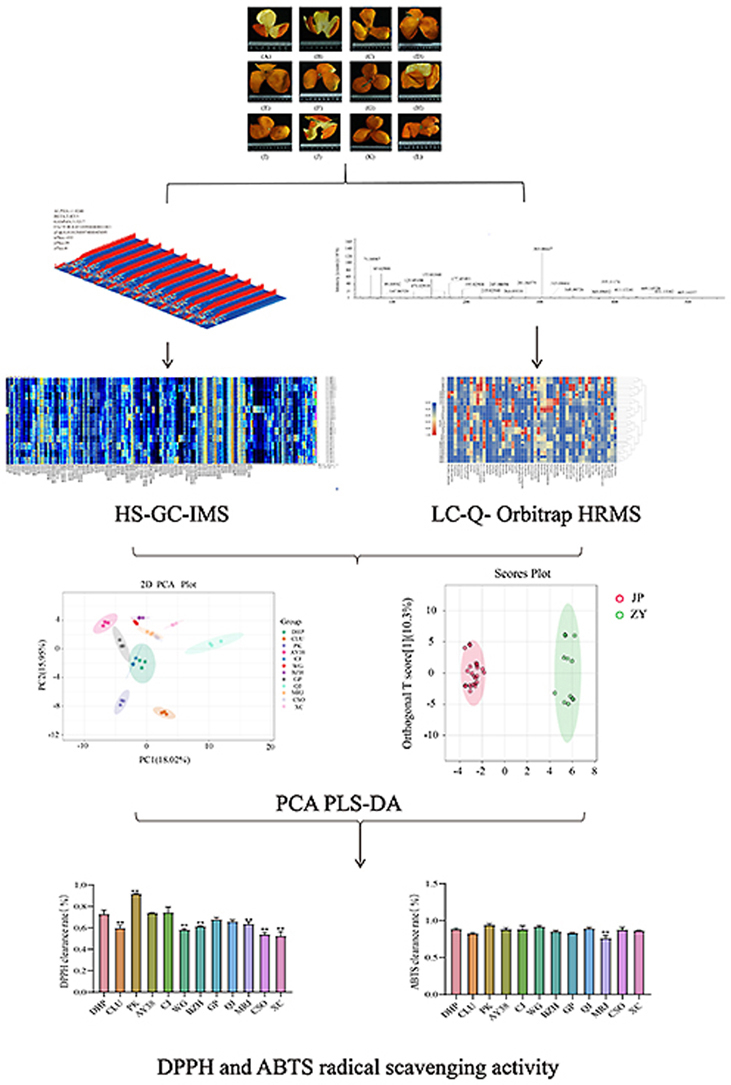

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This paper elucidates the volatile and non-volatile metabolites in 12 citrus peels.

-

•

The chemical composition of different citrus peels has both significant commonalities and differences.

-

•

In this study, we screened some citrus fruit peels for their medicinal value or strong antioxidant activity.

1. Introduction

Citrus fruits, which belong to the Rutaceae family, are the most popular and widely grown type of fruit in the world (Zou et al., 2016). China is the largest producer and consumer of citrus fruits, with the largest production and planting area estimates in the world (Chen et al., 2021). Citrus fruits account for half of the fruit processing industry (Cui et al., 2020). The thousands of tons of peels generated during citrus juice processing are ordinarily considered as agro-industrial waste (Mandalari et al., 2006), which may become a source of economic and environmental concern when the peels undergo fermentation and microbial spoilage (Tundis et al., 2023). Interestingly, citrus peels have a significantly higher antioxidant activity than any other part of a citrus fruit because of their higher phenolic acid and flavonoid content (Manthey and Grohmann, 2001; Singh et al., 2020). In addition, citrus peels contain numerous active biological components, mainly including carotenoids, vitamin E, limonin, polysaccharides, lignin, cellulose, pectin, and essential oils (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2019). In 2002, the Ministry of Health of China announced the “Notice on Further Regulating the Management of Health Food Raw Materials,” which stipulated that citrus peel was a dual-use item, to be used as medicine and food (Health, 2002). Four cultivars of Citrus reticulata are officially listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 version) for clinically treating cough with phlegm, vomiting and diarrhea, and stomach ache: “Chachi,” “C. reticulata ‘Dahongpao’ (DHP),” “Tangerina,” and “C. reticulata ‘Unshiu’(CLU)” (Committee, 2020). The different citrus varieties, the active components of the peel, and the medicinal and edible values will be different (Kim et al., 2021; Y. Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, the compositions of citrus peels must be comprehensively evaluated.

In recent years, the chemical composition of citrus peels has been intensively investigated because of their potential applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries (Maqbool et al., 2023). Na Liu et al. noted that citrus peels mainly contained volatile and nonvolatile metabolites (Liu et al., 2021). The volatile compounds, such as esters, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, sulfides, and terpenes, exhibit strong pharmacological bioactivities, such as antimicrobial (Lin et al., 2021, Lin et al., 2021), antioxidant (Vitalini et al., 2021), anti-inflammatory (C. Li et al., 2022), anti-melanoma (Kulig et al., 2022), and anti-cancer properties (Tundis et al., 2023). D-limonene was reported to alleviate phlegm accumulation and inhibit cancer cells (Vigushin et al., 1998). Linalool was shown to effectively mitigate inflammation (Peana, D'Aquila, Panin, Serra, Pippia and Moretti, 2002). (E)-a-bergamotene and (E)-b-farnesene indirectly defend the plant from Lepidoptera larvae by attracting agricultural and forestry pests (Schnee et al., 2006). The nonvolatile metabolites mainly include flavonoids, alkaloids, and limonoids. Flavonoids, which are divided into flavonoid glycosides and polymethoxyflavones, possess a wide range of biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant (D. Li et al., 2023), immunomodulatory (Mawatari et al., 2023), anti-diabetic, bacteriostatic, and neuroprotective activities (Qiu et al., 2023). Naringin, hesperidin, nobiletin, and tangeretin are the main citrus flavonoids. Nobiletin and tangeretin are beneficial to human health, especially by serving as antioxidants (Choi et al., 2007; Manthey and Grohmann, 2001; Soobrattee et al., 2005). Thus, the chemical compositions of different varieties of citrus peels must be comprehensively evaluated to make better use of this byproduct of the fruit processing industry.

Metabolomics can effectively reveal the variations in metabolite content in different citrus cultivars. Headspace-gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC–IMS) is commonly used in food flavor analysis, especially for separating and detecting volatile organic compounds (S. Wang et al., 2020). Asikin et al. revealed differences in the compositions of volatile aroma compounds in different citrus cultivars using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Asikin et al., 2012). Zhang et al. screened 30 potential volatile biomarkers to distinguish among loose-skin mandarins, sweet oranges, pomelos, and lemons and 17 effective biomarkers to distinguish clementine mandarins from the other loose-skin mandarins and sweet oranges (Zhang et al., 2019). Wang et al. used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to analyze the volatile components of Zangju peel during the whole growth period, which provided a basis for comprehensively understanding its flavor characteristics in the post-ripening period and its applications in food, cosmetics, flavors, and fragrances (P. Wang et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023). Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry has also become a central platform in metabolomics, specifically in the study of natural products and the plant sciences (Salem et al., 2020). Using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, Afifi et al. found that the C. reticulata cultivars “Shiyueju,” “C. reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan (PK),” “Tribute,” and “Bayueju” were effective sources of “chen pi” (Afifi et al., 2023). Luo et al. used ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC–Q-TOF-MS) to clarify the unique properties of Citri Reticulatae Chachi Pericarpium compared with Citri Reticulatae Blanco Pericarpium as well as to delineate the changes in its composition when stored for different number of years (Luo et al., 2019). Wang et al. compared the chemical compositions of two closely related DHP and C. reticulata Blanco ‘Bu Zhi Huo’ (BZH), using UPLC–electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS (F. Wang et al., 2021). By combining HS-GC–IMS and UPLC–Q-TOF-MS we can more comprehensively elucidate the differences in the chemical compositions of samples and the factors affecting them. The cultivation system and the origin of citrus cultivars affect their metabolites and volatile organic compounds, which may ultimately influence their flavor quality (Asikin et al., 2023; Pieracci et al., 2022). Agricultural scientists have bred a wide variety of citrus hybrids in the pursuit of excellent properties, such as high sugar and low acidity, tenderness and low dregs, easy peeling, rich nutritional value, high yield, and easy management.

By far, the most consumed citrus fruits in China are mandarine DHP, CLU, and PK and orange C. sinensis Osbeck'Qicheng’ (CSO) and C. sinensis ‘blood orange’ (XC). Some hybrid citrus species are also becoming popular, such as C. reticulata ‘Ai Yuan 38' (AY38; [CLU × ‘Cramadin’] × ‘Xizhixiang’), C. reticulata ‘Chun Jian’ (CJ; ‘Qing Jian’ × PK F-2432), C. reticulata ‘Wo Gan’ (WG; [mandarin × sweet orange] × ‘Dan Xi’), BZH ('Qing Jian’ × PK Nakano 3), C. reticulata ‘Gan Ping’ (GP; ‘Xizhixiang’ × PK), C. reticulata ‘Qing Jian’ (QJ; C. sinensis ‘Trovita sweet orange’ × CLU), and C. reticulata ‘Mingri Jian’ (MRJ; ('Xingjin No. 46' × CJ) (Jeong et al., 2022). Most of these new citrus varieties have excellent traits, such as high and stable yields, easy management and cultivation, fewer pests and diseases, broad market prospects, and high economic benefits. However, the volatile and nonvolatile metabolites in their citrus peels have been less studied, resulting in a significant waste of resources.

This study aimed to investigate the characteristics and differences in the volatile and nonvolatile metabolites in different varieties of citrus peels. First, nontargeted metabolomics, based on UPLC–Q-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and HS-GC–IMS, was used to evaluate the volatile and nonvolatile metabolites in different varieties of citrus peels. Then, multivariate analyses, such as principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), were applied to mine valuable information from the UPLC–Q-Orbitrap HRMS and HS-GC–IMS data, respectively. In addition, the antioxidant properties of the peels were evaluated. The results of this study will deepen our understanding of the differences in metabolites and antioxidant activities of different varieties of citrus peels and provide guidance for their full and rational use.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and standards

Acetonitrile, formic acid (98–100%), and methanol were procured from American Sigma Company. High-purity deionized water was obtained from a UPT-I-10 ultrapure water system (Chengdu Ultra Pure Technology Co., Ltd.).

2.2. Sample information

Citrus peels were obtained from 12 different varieties of plants (n = 3 per variety) growing in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (Table 1). Citrus plants with consistent growth and no disease were randomly selected, and the samples were picked from three different positions on the plant. Each sample was 20–30 citrus fruits and randomly divided into three replicates. After harvesting the sample, the citrus peel was peeled, washed with water, dried at 50 °C, ground to a powder, passed through a mesh, and stored in a desiccator until further use (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Information about the citrus varieties used in this study.

| Number | Description of sample | Source | Collection sites | Acquisition time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHP | Citrus reticulata ‘Dahongpao’ | – | Qing baijiang district of chengdu | 2022.12 |

| CLU | Citrus reticulata ‘Unshi’ | – | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2022.11 |

| PK | Citrus reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan | – | Qing baijiang district of chengdu | 2022.12 |

| AY38 | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Ai Yuan 38′ | ((C. reticulata ‘Unshiu’ × C. reticulata ‘Cramadin’) × C. reticulata ‘Xizhixiang’) | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2022.11 |

| CJ | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Chun Jian' | (C. reticulata ‘Qing Jian’ × C. reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan F-2432) | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2022.12 |

| WG | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Wo Gan' | ((Mandarin × sweet orange) × C. reticulata ‘Dan Xi’) | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2023.03 |

| BZH | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Bu Zhi Huo' | (C. reticulata ‘Qing Jian’ × C. reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan Nakano 3) | Jintang County, Chengdu | 2023.02 |

| GP | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Gan Ping' | (C. reticulata ‘Xizhixiang’ × C. reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan) | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2022.12 |

| QJ | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Qing Jian' | (C. sinensis ‘Trovita sweet orange’ × C. reticulata ‘Unshiu’) | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2023.03 |

| MRJ | Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Mingri Jian' | (C. reticulata ‘Xingjin No.46' × C. reticulata ‘Chun Jian') | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2023.02 |

| CSO |

Citrus sinensis Osbeck 'Qicheng’ |

Washington navel orange bud from Duarte, California, USA | Jintang County, Chengdu | 2023.02 |

| XC | Citrus sinensis ‘blood orange' | Originally from Italy, it was introduced by Citrus Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in 1992. | Pujiang County, Chengdu | 2023.02 |

Note: Indicates unhybridized varieties.

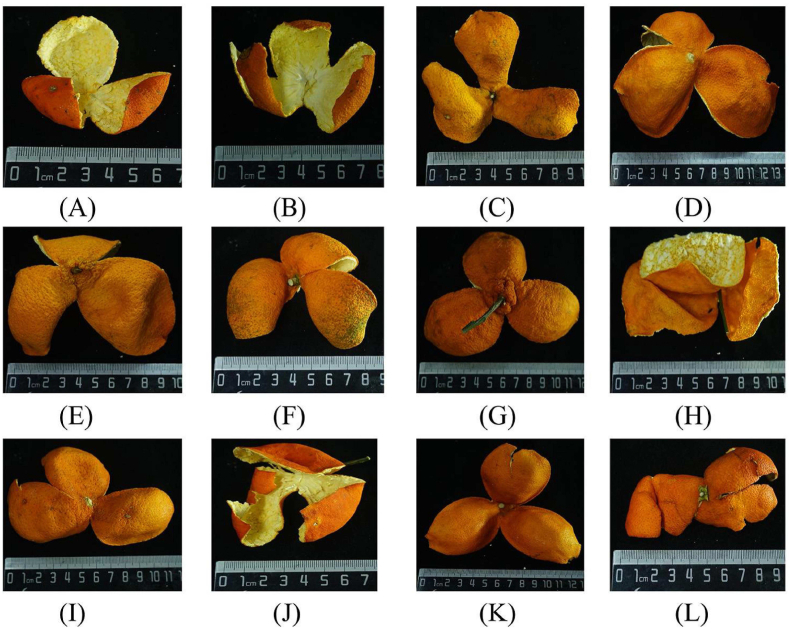

Fig. 1.

Different varieties of citrus peels. (A) C. reticulata ‘Dahongpao’; (B) C. reticulata ‘Unshiu’; (C) C. reticulata Blanco cv. Ponkan; (D) C. reticulata ‘Ai Yuan 38'; (E) C. reticulata ‘Chun Jian’; (F) C. reticulata ‘Wo Gan’; (G) C. reticulata ‘Bu Zhi Huo’; (H) C. reticulata ‘Gan Ping’; (I) C. reticulata ‘Qing Jian’; (J) C. reticulata ‘Mingri Jian’; (K) C. sinensis Osb. var. brasiliensis Tanaka; (L) C. sinensis ‘blood orange'. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

2.3. Sample extraction

2.3.1. Extraction of headspace volatile organic compounds

The samples were processed according to a previously reported method with a few adjustments (Hu et al., 2019). After the citrus peel was cut into pieces, 0.2 g was placed in a 20-mL headspace bottle and incubated at 80 °C for 15 min. Then, 200 μL of the headspace sample was pumped into a heated injector with nitrogen (99.99% purity) at 85 °C.

2.3.2. Extraction for metabolite profiling

The appropriate amount of citrus peel was crushed through a 50-mesh sieve. To about 0.5 g of the powder, 30 mL of 70% methanol was added. Metabolites were ultrasonically extracted in an ultrasonic cleaner for 30 min, and the mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. Finally, the supernatant was passed through a 0.22-μm membrane.

2.4. Instrumentations

The FlavourSpec system (Shandong Hai Neng Science Instrument Co. Ltd., Dezhou, China) was used to perform HS-GC–IMS. The samples were passed through an MXT-5 capillary column (15 m × 0.53 mm) set at 60 °C. The carrier gas flow rate was adjusted as follows: 0–2 min, 2 mL/min; 2–10 min, 2–10 mL/min; 10–20 min, 10–100 mL/min; 20–30 min, 100–150 mL/min; and 30–59 min, 150 mL/min. IMS was performed at 45 °C with nitrogen (purity ≥99.999%) as the drift gas (E1) and carrier gas (E2). The flow rate of the drift gas was set to 150 mL/min from 30 to 59 min.

Metabolite extracts were analyzed using UPLC–Q-TOF-MS (Vanquish, Thermo Fisher Scientific Corp., USA). The Agilent Extend C18 column (100 mm × 3 mm, particle size 1.8 μm) was used. The experiment was conducted in California, USA. The injection volume was 5 μL, the column temperature was 30 °C, and the flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. Mobile phase A was 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water, while phase B was acetonitrile. The 60-min UPLC gradient program was as follows: 0% B, 0∼5 min; 0∼25% B, 5∼12 min; 25∼35% B, 12∼20 min; 35∼45% B, 20∼30 min; 45∼55% B, 30∼40 min; 55∼65% B, 40∼45 min; 65∼100% B, 45∼50 min; 100% B, 50∼52 min; 100∼0% B, 52∼60 min. ESI and positive ion mode were used for detection. The ion source parameters are listed below: spray voltage, 3.2 kV; ion source temperature, 350 °C; sheath gas flow rate, 35 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas flow rate, 10 arbitrary units; ion transport tube temperature, 320 °C; scanning mode, full scan/data-dependent two-stage scan (full MS/dd-MS2); first-order resolution, 70,000; second-order resolution, 17,500; scanning range, 100∼1500; and a collision energy gradient of 20, 40, and 60 eV. Metabolites were identified by matching their MS2 spectral data with peaks displaying comparable fragmentation patterns that were sourced from the literature or from databases (mzCloud, mzVault, PubChem).

2.5. Determination of antioxidant properties

2.5.1. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity

DPPH was detected based on a previously reported method by Singh with some modifications (Singh et al., 2020). Briefly, 100 μL of sample solution was mixed with 100 μL of DPPH working solution (0.0404 mg/mL) and placed at room temperature in the dark for 30 min, after which its absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader. The blank group was established by mixing 95 μL of 95% alcohol with 100 μL of sample solution. The control group was established by mixing 100 μL of 95% alcohol with 100 μL of DPPH solution. The DPPH radical cation scavenging activity was calculated using the following equation. A standard curve for the concentration of the standard compound and the DPPH radical scavenging rate was plotted using Trolox. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the sample was expressed as mg standard compound equivalents/g TE.

| (1) |

In this equation, As indicates the absorbance of the sample group, A0 indicates the absorbance of the blank group, and A1 indicates the absorbance of the control group.

2.5.2. 2,2-Azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS+) radical scavenging activity

ABTS+ was detected according to a previously reported method by Singh et al. (2020). Briefly, 5 mL of ABTS reagent (6.94 mM) was combined with 5 mL of potassium persulfate (2.6 mM), placed at room temperature in the dark for 14 h, and diluted with water to obtain a working solution whose absorbance was 0.7 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. The sample solution (20 μL) was incubated with 200 μL of ABTS+ working solution for 40 min at room temperature in the dark, after which its absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader. The blank group was established by mixing 200 μL of water with 20 μL of sample solution. The control group was established by mixing 20 μL of water with 200 μL of ABTS+ solution. The ABTS+ radical cation scavenging activity was calculated using the following equation. A standard curve was prepared using Trolox, and the ABTS radical scavenging ability was expressed as mg equivalent/g TE.

| (2) |

In this equation, AS indicates the absorbance of the sample group, A0 indicates the absorbance of the blank group, and A1 indicates the absorbance of the control group.

2.5.3. Determination of ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

FRAP was detected according to a previously reported method by Singh et al. (2020). The FRAP reagent was prepared by mixing TPTZ (1 mM), FeCl3•6H2O (2 mM), and 300 mM acetate buffer in a ratio of 10:1:1 at 37 °C. 25 μL of 1 mg/mL extract was mixed with 175 μL of FRAP reagent. A final volume of 200 μL reaction mixture was incubated in the dark for 10 min at 25 °C before taking the absorbance readings at 590 nm. A standard curve was prepared using Trolox, and the ABTS radical scavenging ability was expressed as mg equivalent/g TE.

2.6. Data processing and multivariate statistical analysis

The VOCal software employs the National Institute of Standards and Technology and IMS databases integrated within it to qualitatively analyze substances using their spectra and data. The spectra consist of individual points, each corresponding to a volatile component. The Reporter plug-in analyzes the variations in spectral content among samples by comparing three-dimensional (3D) and differential spectrograms. The Gallery Plot plugin conducts fingerprint comparison to visually and quantitatively analyze the variations in volatile components among various samples. PCA and PLS-DA were performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. HS-GC–IMS analysis of volatile metabolites

3.1.1. Identification of major volatile metabolites

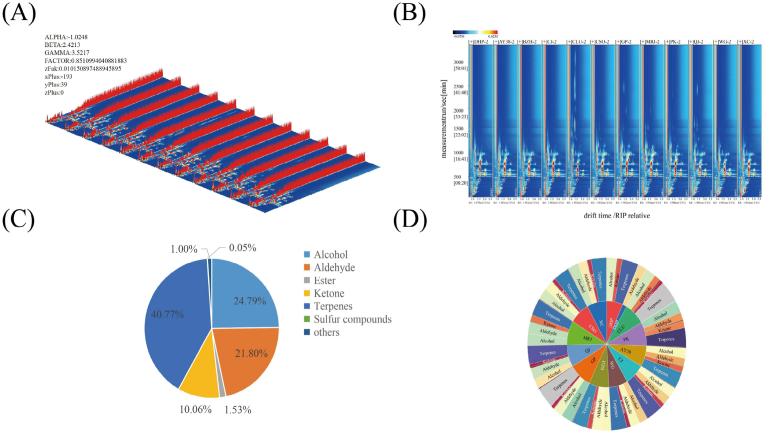

Fig. 2A displays the three-dimensional (3D) surface representations of the volatile metabolites found in the different varieties of citrus peels. We evaluated a range of volatile compounds based on their retention time, drift time, and peak intensity from three different angles. The amount of volatile chemical compounds and the strength of their signals varied slightly among the 12 samples. A planform of the 3D plot, known as the topographic spectrum, was acquired in two-dimensional format (Fig. 2B). In this graph, a red vertical line is positioned at x-coordinate 1. The reactive ion peak at 0 is represented by each node as a normalized volatile metabolite. Many volatile metabolites from the citrus peels were concentrated in the area, with a drift time of 1.0–2.5 s and a retention time of 100–1000 s. Meanwhile, the spectral signals were marked by numbers.

Fig. 2.

Volatile metabolites in different citrus varieties. (A) Three-dimensional topographic plots; (B) Two-dimensional topographic plots; (C) Circular graph of relative content of various volatile metabolites; (D) Volatile metabolites category distribution sun diagram.

A total of 103 volatile metabolites were identified from the GC–IMS library (Table 2), including esters (8), alcohols (25), aldehydes (29), ketones (15), sulfides (1), terpenes (23), and others (2). Alcohols, aldehydes, and terpenes accounted for 87.36% of the volatile metabolites. The other main compounds were esters (1.53%), ketones (10.06%), sulfides (1.00%), and others (0.05%) (Fig. 2C). The volatile metabolites were similarly distributed in the different varieties of citrus peels (Fig. 2D). Previous research has also revealed that alcohols, aldehydes, and terpenoids are the dominant volatile metabolites in citrus peels (Schwab et al., 2008).

Table 2.

Volatile metabolites were identified in different varieties of citrus peels by headspace-gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry.

| Class | Compound | CAS# | Formula | MW | RI | Rt [sec] | Dt [a.u.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Nerolidol | 7212-44-4 | C15H26O | 222.4 | 1567.7 | 3059.1330 | 1.4866 |

| Ethanol(M) | 64-17-5 | C2H6O | 46.1 | 492.9 | 105.6470 | 1.0523 | |

| Ethanol(D) | 64-17-5 | C2H6O | 46.1 | 492.0 | 105.3950 | 1.1348 | |

| 1-Butanol(M) | 71-36-3 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 677.5 | 172.5980 | 1.1832 | |

| 1-Butanol(D) | 71-36-3 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 677.1 | 172.4280 | 1.3827 | |

| 1-Penten-3-ol | 616-25-1 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 694.6 | 182.1030 | 0.9443 | |

| 1-Nonanol | 143-08-8 | C9H20O | 144.3 | 1155.7 | 901.0090 | 1.5374 | |

| 1-heptanol | 111-70-6 | C7H16O | 116.2 | 964.9 | 498.5290 | 1.3931 | |

| 1-Hexanol(M) | 111-27-3 | C6H14O | 102.2 | 874.9 | 356.5090 | 1.3246 | |

| 1-Hexanol(D) | 111-27-3 | C6H14O | 102.2 | 877.1 | 359.2100 | 1.6411 | |

| 1-Pentanol | 71-41-0 | C5H12O | 88.1 | 768.6 | 244.5170 | 1.2554 | |

| Isopulegol | 89-79-2 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1144.0 | 870.3370 | 1.3700 | |

| Isopulegol | 89-79-2 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1144.0 | 870.3370 | 1.8998 | |

| Linalool(M) | 78-70-6 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1108.9 | 784.3190 | 1.2245 | |

| Linalool(P) | 78-70-6 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1107.0 | 779.8210 | 1.6940 | |

| Linalool(P) | 78-70-6 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1106.2 | 777.9370 | 1.7592 | |

| Linalool(P) | 78-70-6 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1107.8 | 781.7050 | 2.2372 | |

| alpha-Terpineol(M) | 98-55-5 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1174.7 | 953.2470 | 1.2979 | |

| alpha-Terpineol(P) | 98-55-5 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1176.2 | 957.4140 | 1.7866 | |

| 2-Methylpropan-1-ol M | 78-83-1 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 630.4 | 152.3040 | 1.1776 | |

| 2-Methylpropan-1-ol D | 78-83-1 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 629.2 | 151.7970 | 1.3611 | |

| (Z)-2-Penten-1-ol | 1576-95-0 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 762.5 | 238.6420 | 1.4511 | |

| Geraniol | 106-24-1 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1246.9 | 1180.9060 | 1.2317 | |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol M | 137-32-6 | C5H12O | 88.1 | 744.1 | 221.8530 | 1.2287 | |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol D | 137-32-6 | C5H12O | 88.1 | 741.2 | 219.2900 | 1.4797 | |

| Aldehyde | Butanal | 123-72-8 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 601.3 | 140.9740 | 1.2896 |

| 2-Methylbutanal M | 96-17-3 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 664.7 | 166.8480 | 1.1663 | |

| 2-Methylbutanal D | 96-17-3 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 665.9 | 167.3550 | 1.4025 | |

| (E)-2-pentenal M | 1576-87-0 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 751.7 | 228.6410 | 1.1077 | |

| (E)-2-pentenal D | 1576-87-0 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 752.6 | 229.4380 | 1.3616 | |

| 3-Methyl-2-butenal M | 107-86-8 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 778.6 | 254.5330 | 1.0948 | |

| 3-Methyl-2-butenal D | 107-86-8 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 778.0 | 253.9220 | 1.3653 | |

| 1-Hexanal M | 66-25-1 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 788.7 | 264.3130 | 1.2610 | |

| 1-Hexanal D | 66-25-1 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 788.0 | 263.7020 | 1.5638 | |

| Heptanal-M | 111-71-7 | C7H14O | 114.2 | 902.2 | 393.1490 | 1.3265 | |

| Heptanal-D | 111-71-7 | C7H14O | 114.2 | 901.7 | 392.3500 | 1.7014 | |

| Octanal | 124-13-0 | C8H16O | 128.2 | 1017.0 | 597.0060 | 1.8263 | |

| Decanal M | 112-31-2 | C10H20O | 156.3 | 1190.9 | 1000.2970 | 1.5387 | |

| DecanaI D | 112-31-2 | C10H20O | 156.3 | 1188.4 | 992.6940 | 2.0484 | |

| Dodecanal | 112-54-9 | C12H24O | 184.3 | 1413.5 | 1936.1840 | 1.6544 | |

| Undecanal | 112-44-7 | C11H22O | 170.3 | 1285.9 | 1325.6690 | 1.5976 | |

| Furfural | 98-01-1 | C5H4O2 | 96.1 | 826.9 | 301.7580 | 1.0883 | |

| 2-Methylpropanal M | 78-84-2 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 561.1 | 126.6460 | 1.1141 | |

| 2-Methylpropanal D | 78-84-2 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 558.0 | 125.6400 | 1.2836 | |

| (E)-2-Hexenal M | 6728-26-3 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 851.6 | 328.7900 | 1.1833 | |

| (E)-2-Hexenal D | 6728-26-3 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 850.5 | 327.5900 | 1.5145 | |

| Nonanal(M) | 124-19-6 | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1100.4 | 764.6700 | 1.4795 | |

| Nonanal(D) | 124-19-6 | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1102.4 | 769.3210 | 1.9491 | |

| Pentanal M | 110-62-3 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 700.1 | 186.1440 | 1.1858 | |

| Pentanal D | 110-62-3 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 699.4 | 185.6130 | 1.4199 | |

| 2-Methyl-2-propenal M | 78-85-3 | C4H6O | 70.1 | 568.1 | 129.0400 | 1.0512 | |

| 2-Methyl-2-propenal D | 78-85-3 | C4H6O | 70.1 | 571.9 | 130.3680 | 1.2287 | |

| 3-Methylbutanal M | 590-86-3 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 650.3 | 160.5910 | 1.1832 | |

| 3-Methylbutanal D | 590-86-3 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 651.5 | 161.0980 | 1.4025 | |

| Ester | Geranyl acetate | 105-87-3 | C12H20O2 | 196.3 | 1384.3 | 1775.2690 | 1.2161 |

| Neryl acetate | 141-12-8 | C12H20O2 | 196.3 | 1358.5 | 1644.6450 | 1.2262 | |

| Butyl isovalerate | 109-19-3 | C9H18O2 | 158.2 | 1028.3 | 617.4230 | 1.8877 | |

| Acetic acid ethyl ester(M) | 141-78-6 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 607.2 | 143.1720 | 1.0938 | |

| Acetic acid ethyl ester(D) | 141-78-6 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 604.0 | 141.9880 | 1.3329 | |

| Ethyl butanoate | 105-54-4 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 810.0 | 284.5660 | 1.2097 | |

| Isobutyl acetate | 110-19-0 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 780.0 | 255.8990 | 1.6067 | |

| 2-nonynoic acid methyl ester | 111-80-8 | C10H16O2 | 168.2 | 1297.2 | 1371.0250 | 1.4670 | |

| Ketone | Carvone (M) | 99-49-0 | C10H14O | 150.2 | 1207.6 | 1050.9830 | 1.3112 |

| Carvone (D) | 99-49-0 | C10H14O | 150.2 | 1220.3 | 1091.5320 | 1.8166 | |

| 1-Penten-3-one | 1629-58-9 | C5H8O | 84.1 | 688.4 | 177.7240 | 1.0825 | |

| 2-Butanone(M) | 78-93-3 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 595.0 | 138.6060 | 1.0647 | |

| 2-Butanone(D) | 78-93-3 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 595.0 | 138.6060 | 1.2444 | |

| 2-Pentanone | 107-87-9 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 689.1 | 178.1790 | 1.1206 | |

| Cyclohexanone(M) | 108-94-1 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 894.8 | 382.2440 | 1.1547 | |

| Cyclohexanone(D) | 108-94-1 | C6H10O | 98.1 | 896.0 | 384.0630 | 1.4492 | |

| 2-Heptanone M | 110-43-0 | C7H14O | 114.2 | 888.5 | 373.6670 | 1.2627 | |

| 2-Heptanone D | 110-43-0 | C7H14O | 114.2 | 889.3 | 374.7070 | 1.6190 | |

| 2-Hexanone M | 591-78-6 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 779.8 | 255.7320 | 1.1909 | |

| 2-Hexanone D | 591-78-6 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 780.3 | 256.2640 | 1.5039 | |

| Acetone | 67-64-1 | C3H6O | 58.1 | 509.3 | 110.3700 | 1.1184 | |

| 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone | 513-86-0 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 711.7 | 194.9390 | 1.3274 | |

| 2,3-Butanedione | 431-03-8 | C4H6O2 | 86.1 | 581.8 | 133.8480 | 1.1803 | |

| Terpenes | farnesene-(M) | 502-61-4 | C15H24 | 204.4 | 1500.1 | 2502.9580 | 1.4332 |

| farnesene-(P) | 502-61-4 | C15H24 | 204.4 | 1506.9 | 2553.7280 | 1.4742 | |

| p-mentha-1,5-diene | 99-83-2 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1008.2 | 581.6800 | 1.6828 | |

| Myrcene(M) | 123-35-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 993.5 | 555.5820 | 1.2750 | |

| Myrcene(P) | 123-35-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 993.9 | 556.3340 | 1.7116 | |

| Myrcene(P) | 123-35-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 994.1 | 556.7100 | 1.9191 | |

| Myrcene(P) | 123-35-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 994.1 | 556.7100 | 2.1439 | |

| alpha-Pinene(M) | 80-56-8 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 936.5 | 447.5680 | 1.2155 | |

| alpha-Pinene(P) | 80-56-8 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 935.1 | 445.2690 | 1.2942 | |

| alpha-Pinene(P) | 80-56-8 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 936.8 | 448.1420 | 1.6690 | |

| alpha-Pinene(P) | 80-56-8 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 932.7 | 441.2470 | 1.7313 | |

| gamma-Terpinene(M) | 99-85-4 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1068.4 | 695.4080 | 1.2152 | |

| gamma-Terpinene(P) | 99-85-4 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1067.6 | 693.7680 | 1.6973 | |

| Limonene M | 138-86-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1041.1 | 641.3330 | 1.2105 | |

| Limonene P | 138-86-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1039.6 | 638.5680 | 1.2887 | |

| Limonene P | 138-86-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1039.6 | 638.5680 | 1.6622 | |

| Limonene P | 138-86-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1041.1 | 641.3330 | 1.7228 | |

| Limonene P | 138-86-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1043.1 | 645.2050 | 2.1628 | |

| beta-Pinene(M) | 127-91-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 975.7 | 519.2280 | 1.2161 | |

| beta-Pinene(P) | 127-91-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 975.9 | 519.7380 | 1.6290 | |

| beta-Pinene(P) | 127-91-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 973.1 | 514.1280 | 1.7175 | |

| beta-Pinene(P) | 127-91-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 973.8 | 515.6580 | 2.1624 | |

| beta-Pinene(P) | 127-91-3 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 972.5 | 513.1080 | 2.5680 | |

| Sulfur compounds | beta-Ionene | 14901-07-6 | C13H20O | 192.3 | 1485.4 | 2396.1810 | 1.4736 |

| others | Dimethyl sulfide | 75-18-3 | C2H6S | 62.1 | 541.1 | 120.1070 | 0.9631 |

| (1r,4r)-(+)-campho | 464-49-3 | C10H16O | 152.2 | 1144.4 | 871.2550 | 1.8639 |

3.1.2. Screening of major volatile metabolites

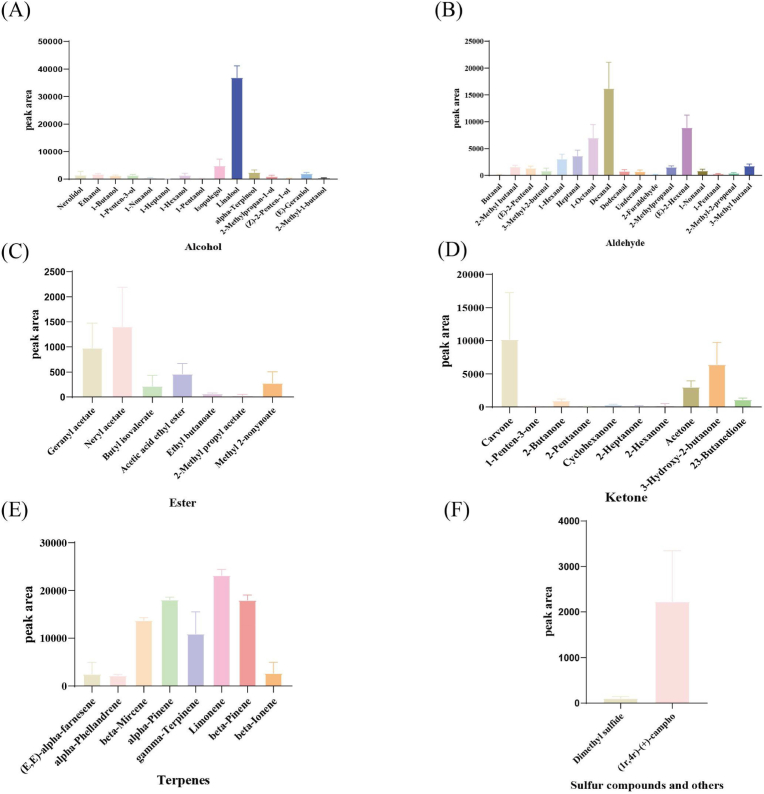

Linalool, isopulegol, and alpha-terpineol together accounted for 79.22% of all alcohols identified in this study (Fig. 3A). Linalool, as an aromatic oil, has a light citrus note and woody floral aroma (Machado et al., 2015) and possesses analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-ultraviolet-skin-damage properties (Tsai et al., 2023). Isopulegol, a citrusy, cool, and herbal odor, is a potential therapeutic agent for clinical complications associated with Parkinson's disease and the restoration of glucose homeostasis because it exhibits antianxiety, anticonvulsion, gastric protection, and antioxidant properties (Kang et al., 2021). Alpha-terpineol is a monoterpene alcohol found to be effective against various tumor cell lines, including lung, breast, leukemia, and colorectal cells (Negreiros et al., 2021). Various other bioactive components were also identified, such as nerolidol, which has a citrusy and woody-floral aroma, and geraniol, which has a rose aroma, both of which are used in cosmetics and fine fragrances (Dosoky and Setzer, 2018).

Fig. 3.

Average content of volatile metabolites in citrus peels. (A) Alcohols; (B) Aldehydes; (C) Esters; (D) Ketones; (E) Terpenes; (F) Sulfur compounds and others.

Aldehydes are key aroma contributors to citrus essential oils, with a sweet, waxy aroma and citrus peel-like odor (Dosoky and Setzer, 2018). Decanal, (E)-2-hexenal, and 1-octanal constituted 68.27% of all aldehydes detected in this study (Fig. 3B). Octanal and decanal are known to be natural aromatic compounds that significantly enhance floral products and perfumes (Deterre et al., 2023). 2-methylbutanal and 3-methylbutanal were identified as characteristic aroma compounds of malt (Majcher et al., 2020). (E)-2-Hexenal as a natural food flavoring (Ma et al., 2022). In addition to their odor contribution, aldehydes are also inhibitory to a wide range of fungi. 3-methylbutanal showed a significant positive correlation with the rates of C. gloeosporioides inhibition (Gao et al., 2018). (E)-2-hexenal inhibited Aspergillus flavus (Ma et al., 2022) and Botrytis cinerea.

Terpenoids are the most important volatiles in the peel of citrus fruits (De-Oliveira et al., 1997). Limonene, beta-pinene, and alpha-pinene accounted for 66.88% of all terpenes identified in this study (Fig. 3E). Limonene is an essential element of many citrus essential oils, gives off an aroma (Sawamura et al., 2004), has been used as a flavoring and food preservative, and is universally recognized for its safety. It also has anti-obesity, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties (Anandakumar et al., 2021). α-pinene has a citrus and spicy, woody pine, and turpentine-like aroma (Vespermann et al., 2017). β-pinene has a characteristically fresh, piney, woody, and resinous taste at 15–100 ppm and a slight nuance of spicy, minty, and camphor (Vespermann et al., 2017). α- and β-pinene have antibiotic resistance-modifying, anticoagulant, antitumor, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antileishmanial, and analgesic effects (Salehi et al., 2019). In addition, many terpenoids have their own biological activities. Farnesene may be a safe, anti-necrotic, and neuroprotective agent against Alzheimer's disease (Arslan et al., 2021). Myrcene has anxiolytic, antioxidant, anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic bioactivities (Surendran et al., 2021).

Esters and ketones make up a relatively low proportion of volatile metabolites. Geranyl and neryl acetate accounted for 60.71% of all esters detected in this study (Fig. 3C). Carvone, acetone, and 3-hydroxy-2-butanone constituted 84.49% of all ketones screened in this study (Fig. 3D).

In summary, the higher-content volatile metabolites in citrus peels included linalool, 1-octanal, decanal, (E)-2-hexenal, carvone, 3-hydroxy-2-butanone, beta-myrcene, alpha-pinene, gamma-terpinene, limonene, and beta-pinene. These compounds contribute significantly to the aroma of the volatile components of citrus peels and have a variety of biological activities with potential applications.

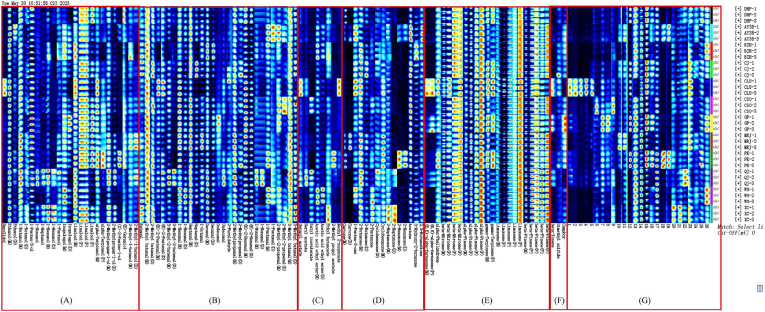

3.1.3. Identification and analysis of differential volatile metabolites

The library drawing plug-in was used to plot the fingerprints of volatile substances, which can allow us to more intuitively compare the relative contents of volatile substances in the different varieties of citrus peels. In the fingerprint, each row represents a sample (three parallel at each stage), and each column represents a volatile component (the darker the color, the higher the content). The main volatile metabolites in citrus peels were alcohols, aldehydes, esters, ketones, terpenes, etc (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The fingerprints of volatile metabolites in different varieties of citrus peel. (A) Alcohols; (B) aldehydes; (C) esters; (D) ketones; (E) terpenes; (F) sulfur compounds and others; (G) unidentified compounds.

Linalool, which possesses notable anti-inflammatory properties, was the principal volatile metabolite in citrus peels (Peana et al., 2002). It was highly expressed in DHP, PK, CJ, GP, MRJ, CSO, and XC. Octanal plays an important role in determining citrus flavor. It was significantly lower in CLU compared with the other varieties, implying that the flavor of CLU may differ significantly from that of the other varieties (Deterre et al., 2023). Decanal and (E)-2-hexenal exhibit excellent antibacterial properties (Gil et al., 2023; Ma et al., 2023, Ma et al., 2023). Decanal was highly expressed in all varieties. The content of (E)-2-hexenal did not differ significantly between DHP and GP, while it was significantly lower in all other varieties. The concentration of carvone, which exerts anti-inflammatory effects, was high in DHP, AY38, MRJ, and PK (Moço et al., 2023). Beta-myrcene, alpha-pinene, beta-pinene, ethanol, and limonene were highly expressed in all citrus varieties. The content of gamma-terpinene was higher in DHP, CJ, CLU, GP, and PK.

2-Penten-1-ol can be considered a characteristic compound of PK. It is a fast-acting fungicidal agent that shows greater effects against Pseudogymnoascus destructans than any other species from that genus (Micalizzi and Smith, 2020). 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone can serve as the characteristic compound of BZH, while methyl 2-nonynoate and nerolidol can serve the same purpose for CLU. Nerolidol is used medicinally to treat colon cancer and can also be used in cosmetics and food regulators (Chan et al., 2016; Raj et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). 1-Nonanol, 1-hexanol, 2-methylpropan-1-ol, and 1-heptanol can be used as characteristic compounds of QJ and XC. The content of 2-methyl-1-butanol, which inhibits fungi and oomycetes, was higher in CJ, MRJ, and BZH than in the other varieties (Costa et al., 2022). 3-Methyl-2-butenal, 1-nonanal, neryl acetate, and undecanal can be used as QJ-characteristic compounds. Dodecanal and 2-heptanone can be used as GP- and XC-characteristic compounds. The relative concentration of farnesene was higher among the terpenoids in CLU and GP. This compound serves as a crucial raw material in agriculture, aviation fuel, and the chemical industry (S. Wang et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023). Geranyl acetate was more elevated in QJ and CLU. Higher concentrations of 2-hexanone in AY38 and PK are responsible for their floral odor (Q. Lin et al., 2021). The total concentration of volatile substances varies considerably among different citrus peels. These waste peels can be good materials for volatile metabolism studies or for the essential oil industry.

3.2. UPLC–Q-Orbitrap HRMS analysis of nonvolatile metabolites

3.2.1. Identification of major nonvolatile metabolites

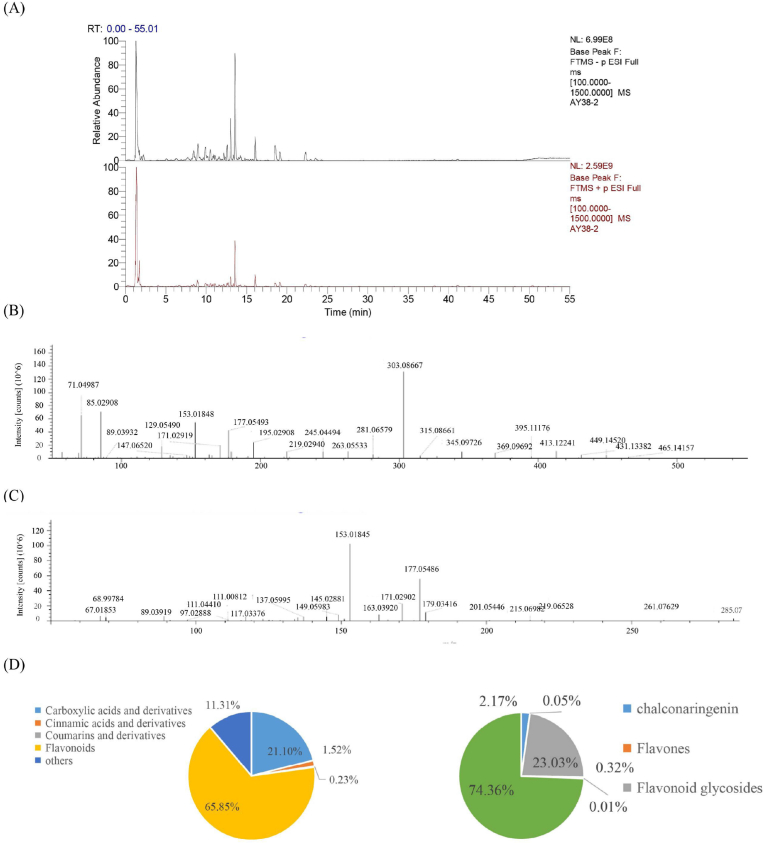

HRMS was performed using ESI, positive and negative ion-switching modes, and the full MS/dd-MS2 scanning mode (Fig. 5A). The multilevel ion fragmentation data were qualitatively analyzed by combining them with data from the mzCloud and mzVault self-built databases, the PubChem network database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), and the literature. A total of 53 nonvolatile metabolites were identified (Table 3), including 23 flavonoids, 12 carboxylic acids and their derivatives, 4 cinnamic acids and their derivatives, 2 coumarins and their derivatives, and 12 compounds from other classes. Flavonoids accounted for 66.02% of all nonvolatile metabolites, carboxylic acids and their derivatives for 19.44%, cinnamic acids and their derivatives for 1.63%, other compounds for 12.82%, and coumarins and their derivatives for only 0.1% (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Total ion current diagram, secondary mass spectrum, and classification of typical nonvolatile metabolites in citrus peels. (A) Total ion current diagram; (B) Second-order mass spectrometry of hesperidin compounds; (C) Second-order mass spectrometry of hesperetin metabolites; (D) Circular graph of the relative contents of nonvolatile metabolites.

Table 3.

Nonvolatile metabolites annotated in various citrus peels via ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–Q-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry using both the positive and negative ionization modes.

| No. | tR/min | compounds | Molecular Formula | m/z | [M−H]−/[M + H]+ | Mass Error (ppm) | HR-MS/MS Product Ions (m/z) | Chemical Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.236 | L-Histidine | C6H9N3O2 | 156.07699 | 155.06963[M+H]+1 | +1.01 | 156.07695,110.07171,95.06095 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 2 | 1.257 | DL-Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | 173.104 | 174.11184[M-H]-1 | +0.96 | 175.11951,116.07106,70.06589 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 3 | 1.259 | Choline | C5H13NO | 104.10745 | 103.10018[M+H]+1 | +4.48 | 104.10750,87.04470,60.08154 | Others |

| 4 | 1.273 | Aspartic acid | C4H7NO4 | 134.04494 | 133.03766[M+H]+1 | +1.14 | 88.03992,74.02437,75.02769 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 5 | 1.326 | D-(+)-Proline | C5H9NO2 | 116.07092 | 115.06364[M+H]+1 | +2.72 | 116.07095,70.06583 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 6 | 1.342 | L(−)-Pipecolinic acid | C6H11NO2 | 130.08642 | 129.07914[M+H]+1 | +1.26 | 130.08653,84.08143 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 7 | 1.402 | Phloroglucinol | C6H6O3 | 127.03919 | 126.03191[M+H]+1 | +1.71 | 127.03927,109.02886,81.03418 | Others |

| 8 | 1.41 | Synephrine | C9H13NO2 | 168.10203 | 167.09475[M+H]+1 | +0.72 | 150.09158,135.06812,91.05485 | Others |

| 9 | 1.421 | D-(+)-Malic acid | C4H6O5 | 133.01352 | 134.0208[M-H]-1 | −5.41 | 133.01363,115.00294,72.99220,71.01292 | Others |

| 10 | 1.456 | 2-Furoic acid | C5H4O3 | 111.00797 | 112.01527[M-H]-1 | −6.91 | 111.00803,83.01294,78.95819,67.01799 | Others |

| 11 | 1.499 | L-Tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | 182.08151 | 181.07424[M+H]+1 | +1.89 | 164.05484,136.07587,123.04435 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 12 | 1.703 | Betaine | C5H11NO2 | 118.08667 | 117.0794[M+H]+1 | +3.57 | 118.08659,72.08419,59.07371 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 13 | 1.713 | Nicotinic acid | C6H5NO2 | 124.0396 | 123.03232[M+H]+1 | +2.36 | 140.03438,124.03957,96.04493 | Others |

| 14 | 1.729 | Citric acid | C6H8O7 | 210.061 | 192.02688[M + NH4]+1 | −0.66 | 191.01956,111.00803,87.00790,85.02863 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 15 | 1.735 | 4-Oxoproline | C5H7NO3 | 128.03465 | 129.04227[M-H]-1 | −2.49 | 128.03462,82.02896, | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 16 | 1.949 | Isoleucine | C6H13NO2 | 132.10224 | 131.09496[M+H]+1 | +2.52 | 90.94827,86.09702,72.93781,69.07069 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 17 | 1.96 | Succinic acid | C4H6O4 | 117.01867 | 118.02595[M-H]-1 | −5.62 | 117.01852,99.00787,73.02851 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 18 | 3.242 | L-Phenylalanine | C9 H11NO2 | 164.07136 | 165.07912[M-H]-1 | +0.87 | 120.08101,107.04958,103.05463 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 19 | 6.604 | D-(+)-Tryptophan | C11H12N2O2 | 203.08253 | 204.09013[M-H]-1 | +1.26 | 188.07077,146.06018,118.06548 | Others |

| 20 | 7.622 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 181.04975 | 180.04247[M+H]+1 | +1.20 | 163.3918,145.02867,135.04433 | Cinnamic acids and derivatives |

| 21 | 7.808 | 4-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 165.05491 | 164.04763[M+H]+1 | +1.73 | 147.04422,119.0495091.05483 | Cinnamic acids and derivatives |

| 22 | 9.988 | Isoferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 195.06542 | 194.05814[M+H]+1 | +1.19 | 177.05481,145.02858,117.03384 | Cinnamic acids and derivatives |

| 23 | 10.155 | Sinapinic acid | C11H12O5 | 207.06546 | 206.05817[M+H]+1 | +0.94 | 207.06557,175.03925,147.04422 | Cinnamic acids and derivatives |

| 24 | 10.923 | Narirutin | C27H32O14 | 581.18669 | 580.17941[M+H]+1 | +0.36 | 273.07590,195.02898,153.01839,85.02901 | Flavonoids |

| 25 | 12.175 | Fisetin | C15H10O6 | 287.0549 | 286.04762[M+H]+1 | −0.41 | 287.05511,153.01833,135.04404 | Flavonoids |

| 26 | 12.367 | Hyperoside | C21H20O12 | 463.08909 | 464.09632[M-H]-1 | +1.81 | 303.05020,153.01839,85.02904 | Flavonoids |

| 27 | 12.947 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 317.06573 | 316.05846[M+H]+1 | +0.49 | 317.06570,302.04224,153.01842 | Flavonoids |

| 28 | 13.003 | Rhoifolin | C27H30O14 | 579.17112 | 578.16397[M+H]+1 | +0.72 | 433.11346,271.06021,153.01846 | Flavonoids |

| 29 | 13.008 | Naringin | C15H12O5 | 273.07569 | 272.06841[M+H]+1 | +0.39 | 273.07587,171.02887,153.01834,147.04417 | Flavonoids |

| 30 | 13.008 | Naringeninchalcone | C27H32O14 | 579.17232 | 580.17943[M-H]-1 | −0.25 | 273.07587,171.02887,153.01834,147.04417 | Flavonoids |

| 31 | 13.362 | Diosmetin | C28H32O15 | 609.18206 | 608.17486[M+H]+1 | −0.22 | 463.12402,301.07089,286.04742 | Flavonoids |

| 32 | 13.55 | Hesperidin | C28H34O15 | 609.18312 | 610.18998[M-H]-1 | +0.34 | 303.08636,153.01833,85.02896 | Flavonoids |

| 33 | 13.551 | Hesperetin | C16H14O6 | 303.08626 | 302.07894[M+H]+1 | −0.33 | 303.08640,177.05472,153.01831 | Flavonoids |

| 34 | 13.664 | Homoplantaginin | C22H22O11 | 463.12372 | 462.11653[M+H]+1 | +0.70 | 301.07089,286.04742,258.5258 | Flavonoids |

| 35 | 13.85 | Neohesperidin | C28H34O15 | 609.1839 | 610.19112[M-H]-1 | +2.22 | 609.18396,301.07214,151.00313 | Flavonoids |

| 36 | 14.363 | Scoparone | C11H10O4 | 207.06551 | 206.05823[M+H]+1 | +1.57 | 207.06523,192.04176,151.07545 | Coumarins and derivatives |

| 37 | 15.788 | Pinocembrin | C15H12O4 | 257.08102 | 256.07375[M+H]+1 | +0.74 | 257.08150,171.02901,153.01846,131.04939 | Flavonoids |

| 38 | 18.033 | Isokaempferide | C16H12O6 | 299.05649 | 300.06372[M-H]-1 | +1.09 | 301.07086,286.04736,258.05280 | Flavonoids |

| 39 | 18.26 | Genistein | C15H10O5 | 269.04605 | 270.05331[M-H]-1 | +1.81 | 271.06027,153.01822,119.04935 | Flavonoids |

| 40 | 18.287 | Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 271.06179 | 272.06904[M-H]-1 | +2.09 | 271.06174,151.00311,119.04951 | Flavonoids |

| 41 | 18.518 | Hispidulin | C16H12O6 | 299.05646 | 300.06373[M-H]-1 | +1.14 | 299.05655,284.03308,136.98741 | Flavonoids |

| 42 | 20.216 | Moxonidine | C9H12ClN5O | 240.06686 | 241.07413[M-H]-1 | +4.55 | 242.08118,227.05780,200.07069 | Others |

| 43 | 22.123 | Monobutyl phthalate | C12H14O4 | 221.08195 | 222.08922[M-H]-1 | +0.06 | 221.08167,121.02860,71.04923 | Others |

| 44 | 22.24 | Tangeritin | C20H20O7 | 373.12855 | 372.12126[M+H]+1 | +0.97 | 373.12814,357.09683,343.08121 | Flavonoids |

| 45 | 22.373 | Scrophulein | C17H14O6 | 315.08661 | 314.07948[M+H]+1 | +1.40 | 315.08652,282.05246,254.05754 | Flavonoids |

| 46 | 23.77 | Limonin | C26H30O8 | 471.20206 | 470.19474[M+H]+1 | +1.44 | 471.20306,425.19720,161.06006 | Others |

| 47 | 24.709 | Nobiletin | C21H22O8 | 403.1392 | 402.13192[M+H]+1 | +1.14 | 403.13907,373.09204,183.02911 | Flavonoids |

| 48 | 25.003 | 6-Demethoxytangeretin | C19H18O6 | 343.11795 | 342.11067[M+H]+1 | +0.98 | 343.11777,313.07074,299.09158 | Flavonoids |

| 49 | 25.404 | Skullcapflavone II | C19H18O8 | 375.10771 | 374.10048[M+H]+1 | +0.84 | 375.10706,345.06061,327.05011 | Flavonoids |

| 50 | 28.806 | Eupatilin | C18H16O7 | 345.0975 | 344.09022[M+H]+1 | +1.80 | 345.09720,330.07339,329.06473 | Flavonoids |

| 51 | 33.685 | Osthol | C15H16O3 | 245.11773 | 244.11045[M+H]+1 | +2.09 | 245.11766,189.05495,131.04945 | Coumarins and derivatives |

| 52 | 37.289 | Nootkatone | C15H22O | 219.17459 | 218.16731[M+H]+1 | +1.14 | 219.17464,163.11180,81.07054 | Others |

| 53 | 37.741 | Hexadecanamide | C16H33NO | 256.26331 | 255.25603[M+H]+1 | −0.73 | 256.26309,153.65048,88.07630 | Others |

Identification of flavonoid glycosides: Flavonoids possess a parent nucleus consisting of a C6–C3–C6 structure. Flavonoid glycosides, such as flavone-O-glycosides and flavone-C-glycosides, are abundantly found in citrus peels. Flavone-O-glycosides are characterized by glycosidic substituents being linked to the flavonoid skeleton through the hydroxyl group at position 7, whereas flavone-C-glycosides contain glycosidic substituents directly attached to the carbon atoms found on the A ring of flavone (S. S. Li et al., 2014). For example, in the negative ion mode, the m/z obtained for the excimer ion [M-H]−1 was 610.18998, and the predicted molecular formula was C28H34O15. In secondary MS, fragment ions with m/z values of 303.08636 [M + H–C6H6O3]+ and 153.01833 [M + H–C9H10O2]+ were formed after retro-Diels-Alder cleavage. After database retrieval and literature comparison, the parent compound was confirmed to be hesperidin (Fig. 5B).

Identification of polymethoxyflavones: Polymethoxyflavones are important flavonoids found in citrus fruits, especially oranges and lemons. These flavonoids possess several methoxyl groups, exhibit low polarity, and have a flat structure (Yang et al., 2021). Their molecular weights vary depending on the number of methoxyl and hydroxyl groups, considering their basic unit of 222 Da (Zhou et al., 2009). For example, a quasimolecular ion [M + H]+ with an m/z of 303.0866 was obtained in the positive ion mode, and the predicted molecular formula was C16H14O6. In secondary MS, fragment ions with m/z values of 177.0554 [M + H–C6H6O3]+ and 153.0190 [M + H–C9H10O2]+ were formed after retro-Diels-Alder cleavage. After database retrieval and literature comparison, the compound was confirmed to be hesperetin (Yang et al., 2021), (Fig. 5C).

3.2.2. Screening of major nonvolatile metabolites

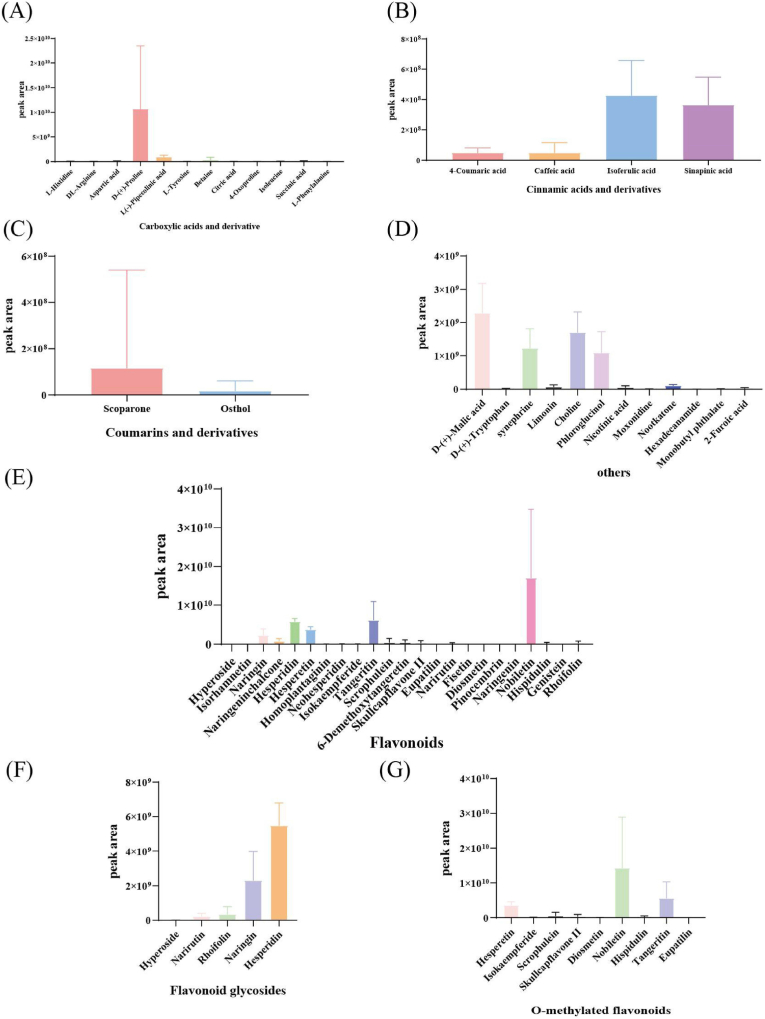

Amino acids are major primary metabolites and important components for the internal quality of citrus fruit (Matsumoto and Ikoma, 2012). D-(+)-proline, L-(−)-pipecolinic acid, and betaine accounted for 95.31% of the carboxylic acids and derivatives detected in this study (Fig. 6A). The aromatic amino acids L-tyrosine and L-phenylalanine are used as dietary supplements to build muscle (Church et al., 2020). Isoleucine and D-(+)-proline are used as dietary supplements to promote the growth of small intestines and skeletal muscles or to reduce excess body fat (Wu, 2013). In addition, betaine has anti-fatty liver, anti-hypertensive, anti-tumor, and other pharmacological effects (Dobrijević et al., 2023).

Fig. 6.

Average content of nonvolatile metabolites in citrus peels. (A) Carboxylic acids and derivatives; (B) cinnamic acids and derivatives; (C) coumarins and derivatives; (D) other compounds; (E) flavonoids; (F) flavonoid glycosides; (G) O-methoxylated flavonoids.

Flavonoids are important bioactive organic compounds found in citrus peels. Flavonoids are expressed by two main categories of compounds (polymethoxylated flavones and glycosylated flavanones) in most of the citrus fruit peels (Ting et al., 2013) (Fig. 6F and G). The flavonoid glycosides naringin, naringenin chalcone, and hesperidin and the O-methoxylated flavonoids hesperetin, tangeritin, and nobiletin together accounted for 93.27% of all flavonoids screened in this study. Naringin, naringenin chalcone, and hesperidin all have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-tumor, antidiabetic, and hepatoprotective potentials (Dias et al., 2021). Polymethoxyflavonoids are a class of flavonoids extracted from citrus plants with a wide range of biological activities and neuroprotective effects. Nobiletin and tangeretin are the most abundant and biologically active polymethoxyflavonoids. Recent studies have shown that nobiletin and tangeretin could be novel drugs for the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer's disease (Matsuzaki and Ohizumi, 2021). In addition, many biologically active natural compounds, such as narirutin, fisetin, and so on, have been identified as having antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer activities (Dias et al., 2021).

Phenolic acids have many biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anticancer activities, making them suitable for use in traditional medicines or as dietary supplements in modern nutritional products (Singh et al., 2020). 4-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, isoferulic acid, and sinapinic acid were prevalent among the cinnamic acid and coumarin compounds screened, in agreement with previous studies (Singh et al., 2020).

D-(+)-malic acid, synephrine, choline, and phloroglucinol made up 92.74% of the other compounds identified in this study (Fig. 6D). Recent studies have shown that the alkaloidal fraction of dried citrus peels has a significant expectorant effect. Synephrine, the most abundant alkaloid in dried citrus peels, has been shown to constrict blood vessels, increase high blood pressure, dilate the airways, improve metabolism, and increase calorie consumption (Perova et al., 2021). Choline used as food supplements has been shown to represent an effective strategy for boosting memory and enhancing cognitive function (Kansakar et al., 2023).

In summary, the compounds with important biological activities found in citrus peels include amino acids (D-(+)-proline, L(−)-pipecolinic acid, and betaine), flavones (naringin, naringenin chalcone, hesperidin, hesperetin, tangeritin, and nobiletin), cinnamic acid and coumarin compounds (4-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, isoferulic acid, and sinapinic acid), alkaloids (synephrine), and limonin. All these findings are consistent with existing research (Benedetto et al., 2023).

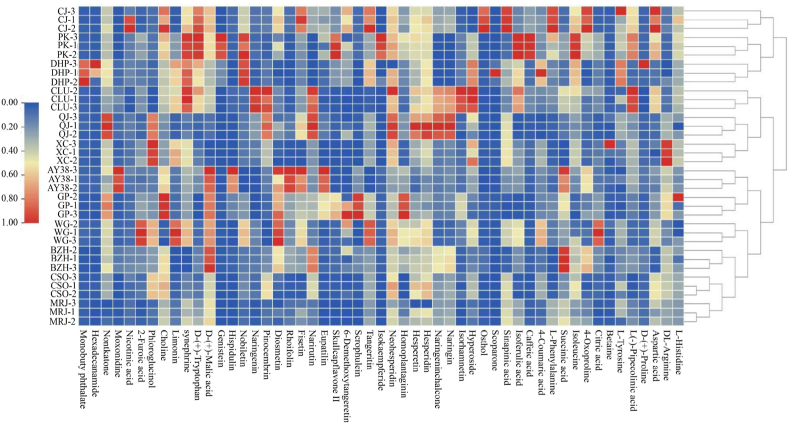

3.2.3. Identification and analysis of differential nonvolatile metabolites

L-pipecolinic acid, which was significantly elevated in CLU, can regulate intestinal microecology (T. T. Ma et al., 2023). Flavonoids including naringin, naringenin chalcone, hesperidin, and hesperetin, which can be used as dietary supplements, were significantly upregulated in QJ (Guan et al., 2023). Tangeritin was significantly upregulated in CJ and WG and is often used as a dietary supplement because of its potent antioxidant effect (How et al., 2023). Nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid with potent pharmacological activity, was significantly upregulated in DHP and PK. 4-Coumaric acid was significantly upregulated in DHP and WG and can regulate the intestinal microflora to protect the gastrointestinal barrier (Z. Y. Wang et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2023). Caffeic acid and isoferulic acid can be used as characteristic metabolites to identify PK, and their supplementation can enhance intestinal integrity and barrier function by modulating the intestinal microbiota and its metabolites (Jiang et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2023). Sinapinic acid alleviates acute pancreatitis in association (Huang et al., 2022). Osthole has exhibited neuroprotective properties against some neurodegenerative diseases (Barangi et al., 2023). Both of these compounds were significantly upregulated in CJ and can be used to characterize this cultivar. Synephrine, which is widely used as an ingredient in dietary supplements and specialty foods to lose weight and improve health (Perova et al., 2021), was significantly upregulated in PK, DHP, and CLU. Limonin was significantly upregulated in WG and serves as an activator of AMP-activated protein kinase with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (Liang et al., 2023). Hispidulin, a promising anticancer agent (Chaudhry et al., 2023), was significantly upregulated in AY38 and could be considered a characteristic metabolite of this cultivar. The above is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Correlation heat map between different varieties of citrus peels and nonvolatile metabolites. Red indicates a strong correlation, blue indicates a weak correlation, and the redder the color, the greater the correlation coefficient (r ≥ 0.9 and P < 0.0001). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.3. Multivariate statistical analyses

3.3.1. Differential volatile and nonvolatile metabolite analysis based on PCA

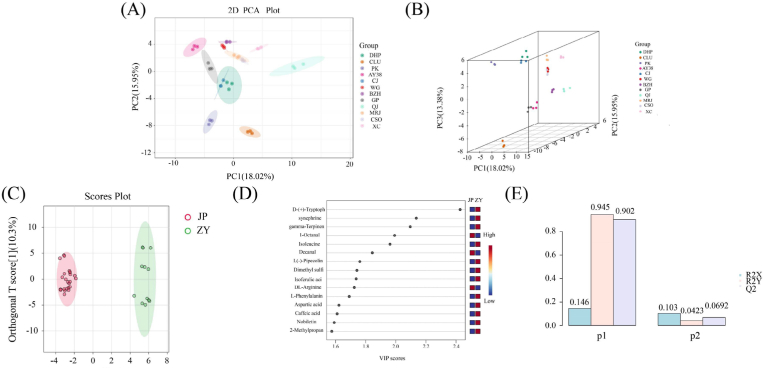

PCA is a detection technique based on the principles of multivariate analysis. It can convert numerous indicators into comprehensive ones, extract characteristics, and unveil the correlation between variables. PCA has been extensively used in the realm of food categorization, particularly for determining the significant organic components within raw materials or food items and showcasing the impact of technical procedures (Venturini et al., 2014).

In this study, two principal components, PC1 and PC2, were extracted and found to be 18.02% and 15.95%, respectively. In the PCA score plot, DHP, PK, CLU, CJ, AY38, WG, BZH, GP, QJ, MRJ, CSO, and XC were clearly separated, and the repeated samples were compactly aggregated (Fig. 8A), indicating that the experiment was reproducible and reliable. The difference between volatile and nonvolatile metabolites was more intuitively appreciated after PCA. The coordinates in the PCA diagram were divided into two groups: Group 1 (ZY) included DHP, CJ, PK, and CLU, and Group 2 (JP) included AY38, WG, BZH, GP, QJ, MRJ, CSO, and XC. DHP and CLU are included in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 edition). The two groups likely differ in some important pharmacodynamic materials.

Fig. 8.

PCA and PLS-DA based on UPLC–Q-Orbitrap HRMS and HS-GC–IMS data. (A) two-dimensional PCA plot; (B) 3D PCA plot; (C) PLS-DA score plot; (D) variable importance in projection scores; and (E) cross-validation results.

3.3.2. Differential volatile and nonvolatile metabolite analysis based on PLS-DA

The first and second components accounted for 10.3% and 14.6%, respectively (Fig. 8C). R2Y and Q2 exhibited exceptional precision, surpassing thresholds of 0.945 and 0.902, respectively (Fig. 8E), indicating that the model was both accurate and reliable (Szymańska et al., 2012). To further determine the volatile and nonvolatile compounds in different citrus peels, the variable importance in projection value was used to evaluate the degree of influence and explanatory power of each variable on sample classification. The 15 characteristic metabolites were selected based on variable importance in projection >1 and p-value <0.01, revealing different applications for different varieties of citrus peels (Fig. 8D).

3.4. Determination of antioxidant properties

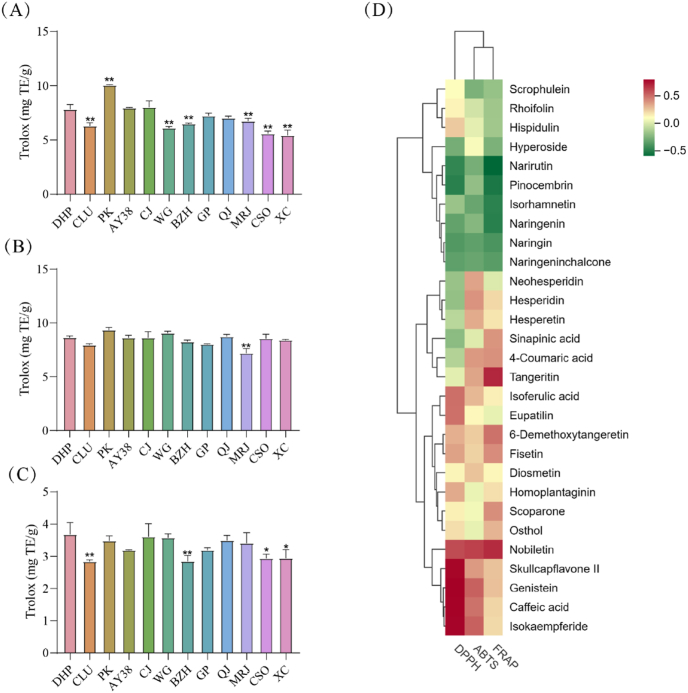

The in vitro antioxidant activities of citrus peels and citrus pulps have been examined by diverse chemical assays, such as ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), and 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (Shang et al., 2018). DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP were used to determine the antioxidant abilities of the different citrus peel extracts. The DPPH free radical scavenging activity of DHP was significantly higher than that of CLU, WG, BZH, MRJ, CSO, and XC (Fig. 9A). The ABTS free radical scavenging activity of DHP was significantly higher than that of MRJ (Fig. 9B). DHP had significantly higher FRAP values than CLU, BZH, CSO, and XC (Fig. 9C). In summary, DHP, PK, AY38, CJ, GP, and QJ displayed good prospects for antioxidant applications (see Table 4).

Fig. 9.

Correlation between antioxidant activities and phenolic compound of the different varieties of citrus peels. (A) DPPH radical scavenging activity; (B) ABTS radical scavenging activity; (C) Ferric reducing antioxidant power; and (D) Correlation heat map. The error bars indicate the standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance plus post-hoc Ducan's test, and * (P < 0.05) indicates a significant difference from DHP.

Table 4.

Antioxidant activities of the citrus varieties peel extracts.

| Sample | DPPH(mg TE/g) | ABTS(mg TE/g) | FRAP(mg TE/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHP | 7.84 ± 0.35 | 8.66 ± 0.11 | 3.68 ± 0.30 |

| CLU | 6.30 ± 0.24a | 7.96 ± 0.08 | 2.84 ± 0.04a |

| PK | 10.07 ± 0.03 | 9.35 ± 0.19 | 3.48 ± 0.13 |

| AY38 | 7.97 ± 0.03 | 8.63 ± 0.19 | 3.20 ± 0.01 |

| CJ | 8.03 ± 0.47 | 8.63 ± 0.46 | 3.62 ± 0.33 |

| WG | 6.11 ± 0.11a | 9.06 ± 0.14 | 3.58 ± 0.09 |

| BZH | 6.50 ± 0.04a | 8.27 ± 0.11 | 2.85 ± 0.15a |

| GP | 7.24 ± 0.18 | 8.04 ± 0.02 | 3.20 ± 0.06 |

| QJ | 7.03 ± 0.15 | 8.74 ± 0.15 | 3.50 ± 0.13 |

| MRJ | 6.76 ± 0.20a | 7.19 ± 0.34a | 3.41 ± 0.26 |

| CSO | 5.59 ± 0.19a | 8.55 ± 0.32 | 2.95 ± 0.10b |

| XC | 5.44 ± 0.39a | 8.41 ± 0.03 | 2.95 ± 0.21b |

Note: Compared with DHP.

P<0.01.

P < 0.05.

Citrus peel contains a large number of phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, flavanones, and polymethoxylated flavones), which have a wide range of biological activities. Antioxidant properties have been widely studied, so in this paper, phenolic acids and antioxidant activities were correlated and analyzed (Singh et al., 2020). The results showed a positive correlation between multiple components. Correlation analysis suggested that some polyphenols, including tangeritin, nobiletin, skullcapflavone II, genistein, caffeic acid, and isokaempferide, were potential antioxidant compounds in citrus peel (Fig. 9D).

4. Conclusions

In this study, we determined the volatile and nonvolatile metabolites and the antioxidant activities in the peels of mainstream and new hybrid varieties of citrus fruits. We noted significant commonalities as well as differences in the chemical components of the different citrus peels.

The citrus peels shared some common volatile metabolites, including linalool, decanal, (E)-2-hexenal, beta-myrcene, alpha-pinene, ethanol, limonene, and beta-pinene. Some citrus peels were associated with the accumulation of certain specific volatile metabolites, such as PK with (Z)-2-penten-1-ol, BZH with 3-hydroxy-2-butanone, and GP with dodecanal. These citrus peels can be used to extract essential oils and to explore other applications of their volatile compounds. The citrus peels also contained nonvolatile metabolites with important biological activities, such as amino acids (D-(+)-proline and betaine), flavones (naringin, naringenin chalcone, hesperidin, hesperetin, tangeritin, and nobiletin), cinnamic acid and coumarin compounds (4-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, isoferulic acid, and sinapinic acid), and alkaloids (synephrine). Some citrus peels were associated with the accumulation of certain specific nonvolatile metabolites, such as PK with caffeic and isoferulic acids, CLU with L-pipecolinic acid, and WG with limonin. The commonalities and differences in the metabolites within different citrus peels provide an important reference for their nutritional and pharmacological values.

PCA and PLS-DA indicated that CJ, PK, CLU, and DHP were clustered together. The fact that DHP is a traditional Chinese medicine documented in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia implies that the chemical compositions of CJ, PK, and CLU may have medicinal values similar to those of DHP. DHP, PK, AY38, CJ, GP, and QJ exhibited better antioxidant activities, recommending their use as additives in cosmetics and food. Correlation analysis suggested that some polyphenols including tangeritin, nobiletin, skullcapflavone II, genistein, caffeic acid, and isokaempferide were potential antioxidant compounds in citrus peel.

The findings of this study deepen our understanding of the commonalities and differences in the volatile and nonvolatile metabolites within different varieties of citrus peels. Moreover, they provide guidance for the full and rational utilization of citrus peels.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 82104340 and the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province, China, grant number 2022NSFSC1450.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Haifan Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Peng Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Fu Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Resources. Hongping Chen: Investigation, Software. Lin Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology. Yuan Hu: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Youping Liu: Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who contributed directly or indirectly to the project. In addition, we thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Handling Editor: Dr. Maria Corradini

Contributor Information

Yuan Hu, Email: huyuan@cdutcm.edu.cn.

Youping Liu, Email: youpingliu@cdutcm.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Afifi S.M., Kabbash E.M., Berger R.G., Krings U., Esatbeyoglu T. Comparative untargeted metabolic profiling of different parts of citrus sinensis fruits via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry coupled with multivariate data analyses to unravel authenticity. Foods. 2023;12(3) doi: 10.3390/foods12030579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandakumar P., Kamaraj S., Vanitha M.K. D-limonene: a multifunctional compound with potent therapeutic effects. J. Food Biochem. 2021;45(1) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan M.E., Türkez H., Mardinoğlu A. In vitro neuroprotective effects of farnesene sesquiterpene on alzheimer's disease model of differentiated neuroblastoma cell line. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021;131(8):745–754. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1754211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asikin Y., Taira I., Inafuku-Teramoto S., Sumi H., Ohta H., Takara K., Wada K. The composition of volatile aroma components, flavanones, and polymethoxylated flavones in Shiikuwasha (Citrus depressa Hayata) peels of different cultivation lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(32):7973–7980. doi: 10.1021/jf301848s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asikin Y., Tamura Y., Aono Y., Kusano M., Shiba H., Yamamoto M.…Wada K. Multivariate profiling of metabolites and volatile organic compounds in citrus depressa hayata fruits from kagoshima, okinawa, and taiwan. Foods. 2023;12(15) doi: 10.3390/foods12152951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barangi S., Hosseinzadeh P., Karimi G., Tayarani Najaran Z., Mehri S. Osthole attenuated cytotoxicity induced by 6-OHDA in SH-SY5Y cells through inhibition of JAK/STAT and MAPK pathways. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2023;26(8):953–959. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2023.68292.14905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetto N., Carlucci V., Faraone I., Lela L., Ponticelli M., Russo D.…Milella L. An insight into citrus medica linn.: a systematic review on phytochemical profile and biological activities. Plants. 2023;12(12) doi: 10.3390/plants12122267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W.K., Tan L.T., Chan K.G., Lee L.H., Goh B.H. Nerolidol: a sesquiterpene alcohol with multi-faceted pharmacological and biological activities. Molecules. 2016;21(5) doi: 10.3390/molecules21050529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry G.E., Zeenia, Sharifi-Rad J., Calina D. Hispidulin: a promising anticancer agent and mechanistic breakthrough for targeted cancer therapy. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00210-023-02645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Pan H., Hao S., Pan D., Wang G., Yu W. Evaluation of phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of different varieties of Chinese citrus. Food Chem. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.Y., Ko H.C., Ko S.Y., Hwang J.H., Park J.G., Kang S.H.…Kim S.J. Correlation between flavonoid content and the NO production inhibitory activity of peel extracts from various citrus fruits. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007;30(4):772–778. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church D.D., Hirsch K.R., Park S., Kim I.Y., Gwin J.A., Pasiakos S.M.…Ferrando A.A. Essential amino acids and protein synthesis: insights into maximizing the muscle and whole-body response to feeding. Nutrients. 2020;12(12) doi: 10.3390/nu12123717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee N.P. China Medical Science and Technology Press; Beijing: 2020. Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- Costa A., Corallo B., Amarelle V., Stewart S., Pan D., Tiscornia S., Fabiano E. Paenibacillus sp. strain UY79, isolated from a root nodule of Arachis villosa, displays a broad spectrum of antifungal activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022;88(2) doi: 10.1128/aem.01645-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Ren W., Zhao C., Gao W., Tian G., Bao Y.…Zheng J. The structure-property relationships of acid- and alkali-extracted grapefruit peel pectins. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;229 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-Oliveira A.C., Ribeiro-Pinto L.F., Paumgartten J.R. In vitro inhibition of CYP2B1 monooxygenase by beta-myrcene and other monoterpenoid compounds. Toxicol. Lett. 1997;92(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(97)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deterre S.C., Jeffries K.A., McCollum G., Stover E., Leclair C., Manthey J.A.…Plotto A. Sensory quality of Citrus scion hybrids with Poncirus trifoliata in their pedigrees. J. Food Sci. 2023;88(4):1684–1699. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias M.C., Pinto D., Silva A.M.S. Plant flavonoids: chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules. 2021;26(17) doi: 10.3390/molecules26175377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrijević D., Pastor K., Nastić N., Özogul F., Krulj J., Kokić B.…Kojić J. Betaine as a functional ingredient: metabolism, health-promoting attributes, food sources, applications and analysis methods. Molecules. 2023;28(12) doi: 10.3390/molecules28124824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosoky N.S., Setzer W.N. Biological activities and safety of citrus spp. essential oils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(7) doi: 10.3390/ijms19071966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Li P., Xu X., Zeng Q., Guan W. Research on volatile organic compounds from Bacillus subtilis CF-3: biocontrol effects on fruit fungal pathogens and dynamic changes during fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:456. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil S.S., Cappellari L.D.R., Giordano W., Banchio E. Antifungal activity and alleviation of salt stress by volatile organic compounds of native Pseudomonas obtained from mentha piperita. Plants. 2023;12(7) doi: 10.3390/plants12071488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mejía E., Rosales-Conrado N., León-González M.E., Madrid Y. Citrus peels waste as a source of value-added compounds: extraction and quantification of bioactive polyphenols. Food Chem. 2019;295:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.05.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan T., Bian C., Ma Z. In vitro and in silico perspectives on the activation of antioxidant responsive element by citrus-derived flavonoids. Front. Nutr. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1257172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health M.o. 2002. Notice of the Ministry of Health on Further Regulating the Management of Health Food Raw Materials. [Google Scholar]

- How C.M., Cheng K.C., Li Y.S., Pan M.H., Wei C.C. Tangeretin supplementation mitigates the aging toxicity induced by dietary benzo[a]pyrene exposure with aberrant proteostasis and heat shock responses in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023 doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c02307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Wang R., Guo J., Ge K., Li G., Fu F.…Shan Y. Changes in the volatile components of candied kumquats in different processing methodologies with headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry. Molecules. 2019;24(17) doi: 10.3390/molecules24173053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.W., Tan P., Yi X.K., Chen H., Sun B., Shi H.…Fu W.G. Sinapic acid alleviates acute pancreatitis in association with attenuation of inflammation, pyroptosis, and the AMPK/NF-[Formula: see text]B signaling pathway. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022;50(8):2185–2197. doi: 10.1142/s0192415x2250094x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong B.G., Gwak Y.J., Kim J., Hong W.H., Park S.J., Islam M.A.…Chun J. Antioxidative properties of machine-drip tea prepared with citrus fruit peels are affected by the type of fruit and drying method. Foods. 2022;11(14) doi: 10.3390/foods11142094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Xie M., Chen G., Qiao J., Zhang H., Zeng X. Phenolics and carbohydrates in buckwheat honey regulate the human intestinal microbiota. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6432942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B., Li N., Liu S., Qi S., Mu S. Protective effect of isopulegol in alleviating neuroinflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced BV-2 cells and in Parkinson disease model induced with MPTP. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2021;40(3):75–85. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2021038944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansakar U., Trimarco V., Mone P., Varzideh F., Lombardi A., Santulli G. Choline supplements: an update. Front. Endocrinol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1148166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.S., Lee S., Park S.M., Yun S.H., Gab H.S., Kim S.S., Kim H.J. Comparative metabolomics analysis of citrus varieties. Foods. 2021;10(11) doi: 10.3390/foods10112826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulig M., Galanty A., Grabowska K., Podolak I. Assessment of safety and health-benefits of Citrus hystrix DC. peel essential oil, with regard to its bioactive constituents in an in vitro model of physiological and pathological skin conditions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022;151 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Zhu H., Zhao K., Li X., Tan Z., Zhang W.…Zhang L. Chemical constituents, biological activities and anti-rheumatoid arthritic properties of four citrus essential oils. Phytother Res. 2022;36(7):2908–2920. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Yang L., Wang W., Song C., Xiong R., Pan S.…Geng Q. Eriocitrin attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung injury in mice by regulating MKP1/MAPK pathway mediated-glycolysis. Int. Immunopharm. 2023;118 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.S., Wu J., Chen L.G., Du H., Xu Y.J., Wang L.J.…Wang L.S. Biogenesis of C-glycosyl flavones and profiling of flavonoid glycosides in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) PLoS One. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., Liu G., Fan Q., Nie Z., Xie S., Zhang R. Limonin, a novel AMPK activator, protects against LPS-induced acute lung injury. Int. Immunopharm. 2023;122 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Ni H., Wu L., Weng S.Y., Li L., Chen F. Analysis of aroma-active volatiles in an SDE extract of white tea. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021;9(2):605–615. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Cao S., Sun J., Lu D., Zhong B., Chun J. The chemical compositions, and antibacterial and antioxidant activities of four types of citrus essential oils. Molecules. 2021;26(11) doi: 10.3390/molecules26113412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Li X., Zhao P., Zhang X., Qiao O., Huang L.…Gao W. A review of chemical constituents and health-promoting effects of citrus peels. Food Chem. 2021;365 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Zeng W., Huang K.E., Li D.X., Chen W., Yu X.Q., Ke X.H. Discrimination of Citrus reticulata Blanco and Citrus reticulata 'Chachi' as well as the Citrus reticulata 'Chachi' within different storage years using ultra high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometry based metabolomics approach. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019;171:218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Yang N., Xie Y., Li Y., Xiao Q., Li Q.…Liu W. Effect of the probiotic strain, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum P9, on chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pharmacol. Res. 2023;191 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Zhao L., Johnson E.T., Xie Y., Zhang M. Natural food flavour (E)-2-hexenal, a potential antifungal agent, induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in Aspergillus flavus conidia via a ROS-dependent pathway. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022;370 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.109633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Zhao L., Johnson E.T., Xie Y., Zhang M. Corrigendum to "Natural food flavour (E)-2-hexenal, a potential antifungal agent, induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in Aspergillus flavus conidia via a ROS-dependent pathway". Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023;394 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2023.110185. [Int. J. Food Microbiol. 370 (2022) 109633] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado B.A., Barreto Gde A., Costa A.S., Costa S.S., Silva R.P., da Silva D.F.…Padilha F.F. Determination of parameters for the supercritical extraction of antioxidant compounds from green propolis using carbon dioxide and ethanol as Co-solvent. PLoS One. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majcher M.A., Olszak-Ossowska D., Szudera-Kończal K., Jeleń H.H. Formation of key aroma compounds during preparation of pumpernickel bread. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68(38):10352–10360. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandalari G., Bennett R.N., Bisignano G., Saija A., Dugo G., Lo Curto R.B.…Waldron K.W. Characterization of flavonoids and pectins from bergamot (Citrus bergamia Risso) peel, a major byproduct of essential oil extraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54(1):197–203. doi: 10.1021/jf051847n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey J.A., Grohmann K. Phenols in citrus peel byproducts. Concentrations of hydroxycinnamates and polymethoxylated flavones in citrus peel molasses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49(7):3268–3273. doi: 10.1021/jf010011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]