A fundamental principle of health ethics is the preservation of human life, though disagreements may arise on how this is best achieved in times of war. With ongoing events in Israel and Gaza, concerns have been raised about the betrayal of this core ethic.1 Because of the possibility of war crimes and the scale of Palestinian morbidity and mortality, the rate and sum of which are unprecedented in the 21st century and still growing, it is crucial to find a way to adjudicate two opposing claims. Is the Israeli military (a) taking appropriate precaution to avoid harming civilians, or (b) making no or insufficient attempt to avoid killing civilians?

A new study by Poole and colleagues adds some evidence to address this by examining the pattern of damage to medical buildings compared to non-medical buildings in Gaza. The authors conducted a geospatial analysis of infrastructure damage between 7 October and 7 November 2023 and found no convincing evidence that medical complexes were spared bombing damage relative to non-medical buildings .2 Of 167 292 buildings assessed for damage, including 106 medical complexes, 9% of both medical and non-medical buildings were damaged during the first month of bombardment. Given the protected status of healthcare entities under international humanitarian law (IHL), and their crucial role in serving civilians in war time, Poole et al raise the larger question of whether IHL’s three principles of engagement—distinction, proportionality and precaution—are being honoured by Israeli forces with respect to civilian objects in Gaza. Scrutinising Palestinian mortality data, we offer additional insights.

The gravity of civilian casualties demands particularly close attention to context and relevant statements. On the one hand, the UK prime minister claimed 19th October 2023, with the USA echoing soon after, that Israel is ‘taking every precaution to avoid harming civilians’.3 But Israeli leaders expressed intent to “cause maximum damage” and to “flatten” the Gaza Strip4 alongside plans for ethnic cleansing. In light of these statements and the extensive bombing, UN experts and scholars of genocide and Holocaust studies warned as early as October of genocidal intent, impending genocide or even a ‘textbook case of genocide’.5 Such violence in the service of native elimination is a near-universal feature of settler colonial projects.6 This backdrop contextualises the declaration from Israeli President Isaac Herzog that ‘[w]e intend to take over the entire Gaza Strip and change the course of history’.7

Israel also has a record of deliberate attacks on civilian targets. In 2014, during the most extensive attack on Gaza prior to the one currently unfolding, historian Rashid Khalidi addressed the question of whether Israel was attempting to limit civilian casualties: ‘To believe that is to willfully suspend belief and to ignore the nature of the weapons used—and, equally important, it is to ignore Israel’s established military doctrine’.8 The so-called Dahiya Doctrine, which references the destruction of the Dahiya quarter of Beirut by Israel’s military in 2006, was revealed publicly 2 years later by former army chief of staff, now Israeli parliament member, Gadi Eizenkot. He stated that ‘disproportionate force’ on civilian quarters ‘is not a recommendation. This is a plan. And it has been approved.’8

Despite the Dahiya Doctrine’s precedent and Israeli leaders’ expressed intentions during the ongoing attacks, the interrogation of Israel’s conduct regarding civilian welfare remains as contested as ever in 2023. Leaving aside the legal question of whether Israel has the right to defend itself from a population it occupies, at the heart of the issue is the civilian targeting exception within international humanitarian law (IHL): civilian infrastructures—hospitals, homes, apartments, schools, etc—cannot be targeted in war except if they are being used to commit ‘acts harmful to the enemy’, and after a required warning.9 If combatants take up military positions within such facilities, they should demonstrate that attacks on these infrastructures further military objectives and that the rule of proportionality demanding minimised, incidental harm to civilians is upheld. That no evidence was found for a military command centre within Gaza’s largest hospital,10 disproving Israeli and US claims, suggests suggests more robust protection mechanisms are needed.

Given the currently limited access into Gaza, it is difficult for external parties to directly investigate whether the IHL caveat on targeting civilian infrastructure is being respected. But the geospatial analysis by Poole and colleagues suggests that the high threshold of the civilian targeting exception within IHL may not have been met. This study also comes on the heels of an investigation by two Israeli journalism organisations, +972 Magazine and Local Call, that shows Israel’s willingness in 2023 to target civilian infrastructure and families.11 Based on conversations with Israeli intelligence officials and Palestinian witnesses, the report revealed that new strategies of the Israeli military, often accomplished with artificial intelligence-based systems and ‘contrary to the protocol used…in the past’, have included the foregoing of warning shots along with strikes on residential buildings with no active military targets. The intelligence officials who were interviewed all understood ‘that damage to civilians is the real purpose of these attacks’, generating civilian casualty numbers in the many thousands that are largely consistent across tallies from the Israeli military, the Ministry of Health in Gaza and independent researchers.11 12 The extensive use of US-made 2000-pound bombs, which kill anyone within 30 meters and often well beyond, further corroborates these accounts – especially when used in Gaza’s densely populated cities and refugee camps.13

A US medical ethicist, Matthew Wynia, recently proposed that the intentional killing of civilians in Gaza may be ethical, even beyond what is permitted under IHL.14 Providing a few ‘impossible questions’ where ‘people with equally strong commitments to human rights’ may disagree, he suggests that killing injured children or blocking essential medications may be morally justifiable if combatants are nearby. Whether these are truly impossible ethical questions has been challenged.15 Wynia’s analysis also neglects the salient context that most people in the Gaza Strip are refugees who, denied their right of return, do not willingly choose to live in a landscape where the ‘unavoidable tragedy of urban warfare’ makes them exceedingly vulnerable to death.14 We must also consider the ethics of denying water, food, fuel, and electricity to an entire population, as similar tactics were widely condemned as criminal in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war.

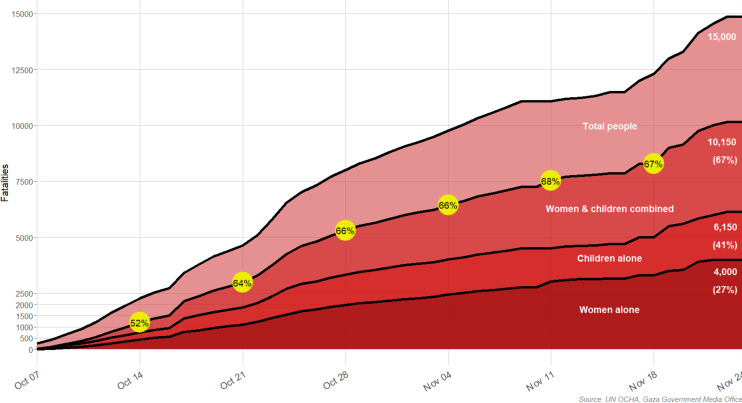

Beyond the geospatial evidence from Poole and colleagues, the pattern of civilian casualties in the Gaza Strip from 7 October until the truce beginning 24 November (figure 1), is instructive. 1

Figure 1.

Cumulative Palestinians Killed in the Gaza Strip, Oct 7-Nov 24, 2023.

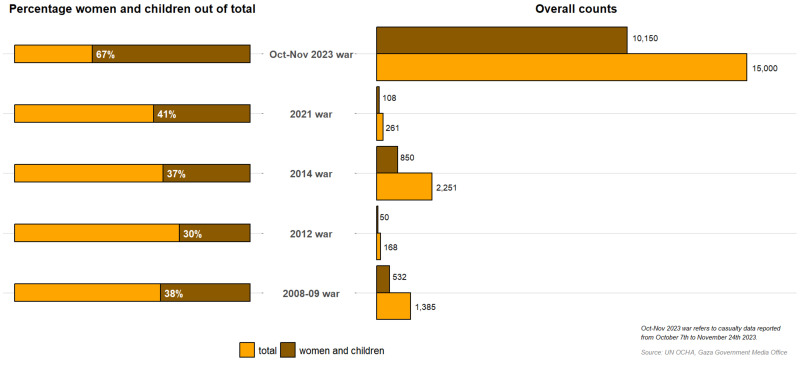

Children make up 47% of the population in the Gaza Strip,16 but from 7 October to 24 November they were killed at a nearly equivalent proportion of 41%. Of note, 3.2% (36 of 1139) of people killed during Hamas’ attacks in Israel on 7 October were children, which garnered global condemnation and provided justification for the subsequent bombardment of Gaza.17 While large numbers of children and women have been killed in attacks on Gaza over the last 15 years, the proportions during the initial phase of the latest offensive are conspicuously higher (figure 2). Women and children were 30–41% of those killed in attacks on Gaza in 2008–2009, 2012, 2014 and 2021, but they make up 67% killed from 7 October to 24 November. This striking increase in mortality, which suggests an indiscriminate approach to civilian targets, is concordant with the investigative report11 and Poole and colleagues’ study demonstrating a lack of special protection for hospitals.3

Figure 2.

Proportion of Women and Children Killed and Overall Numbers Killed in the Gaza Strip During the Wars of 2008-2009, 2012, 2014, 2021, and Oct-Nov 2023.

Surveying Gaza’s mortality data in figure 2, it is notable that the proportion of women and children killed would be indistinguishable if Israel were known to be indiscriminately bombing civilians. Considering this alongside the geospatial data, large bombs used in densely populated areas, and statements from Israeli military officials and politicians, we are left with strong reasons to believe that insufficient attempts are being made to avoid civilian casualties in Gaza. Because this would amount to a war crime and a plausible breach of the Genocide Convention,18 and because many Western governments have provided material and diplomatic support for Israel’s bombardments, we recommend that investigative and accountability mechanisms should be considered to address the roles of all complicit parties.

bmjgh-2023-014756supp001.pdf (90.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp002.pdf (47.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp003.pdf (58.1KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp004.csv (235B, csv)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp005.csv (2.8KB, csv)

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: BW, DM, YMA, and WH conceived of this manuscript and BW prepared a first full draft. DK compiled the data and produced the figures. AKA conceived and drafted legal arguments. All authors reviewed the draft and provided edits, additions, and comments.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: BW, DM, YMA and WH are co-directors of the Palestine Program for Health and Human Rights. AKA serves as Special Advisor on the right to health for Human Rights Watch. We do not have professional or financial relationships with the authors of the Poole et al study.

Provenance and peer review: Initially submitted as a commentary, the manuscript was revised as an editorial at the invitation of the journal’s Editor in Chief. Internally peer reviewed.

Author note: Additional references are available as a online supplemental file 2.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

It is not currently possible to distinguish adult male civilians from combatants, the latter of whom are fewer than 5% of adult men, so the presented data represent a significant undercount of total civilian mortality while also inappropriately simplifying all women as non-combatants. See supplemental text on data for further information on data sources and calculation.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information (online supplemental files 3–5)

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

No ethics approval required.

References

- 1. Hadi S, Aswad L, Shami S. Israel is bombing hospitals in Gaza with Israeli doctors’ approval. 2023. Available: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/11/11/israel-is-bombing-hospitals-in-gaza-with-israeli-doctors-approval [Accessed 30 Nov 2023].

- 2. Poole DN, Andersen D, Raymond NA, et al. Damage to medical complexes RAISES concern for lack of protection in Israel-Hamas war: evidence from a Geospatial analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sunak R. PM statement at press conference with Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel, 19 October . 2023. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-statement-at-press-conference-with-prime-minister-netanyahu-of-israel-19-october-2023 [Accessed 30 Nov 2023].

- 4. McKernan B, Kierszenbaum Q. Emphasis is on damage, not accuracy’: ground offensive in Gaza seems imminent. 2023. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/10/right-now-it-is-one-day-at-a-time-life-on-israels-frontline-with-gaza [Accessed 30 Nov 2023].

- 5. Pilkington E. Top UN official in New York steps down citing ‘genocide’ of Palestinian Civiliants. 2023. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/31/un-official-resigns-israel-hamas-war-palestine-new-york [Accessed 24 Dec 2023].

- 6. Wolfe P. Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research 2006;8:387–409. 10.1080/14623520601056240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tharoor I. Israel is struggling to destroy Hamas, but it’s destroying Gaza. 2023. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/20/israel-battlefield-gaza-defeat-hamas/ [Accessed 23 Dec 2023].

- 8. Khalidi R. The Dahiya doctrine, proportionality, and war crimes. J of Palest Stud 2014;44:5–13. 10.1525/jps.2014.44.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. International Committee of the Red Cross . Geneva convention (I) on wounded and sick in armed forces in the field, 1949: article 21 – discontinuance of protection of medical establishments and units. Geneva: International Humanitarian Law Databases; 1952. Available: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gci-1949/article-21/commentary/1952 [Accessed 24 Apr 2024]. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loveluck L, Hill E, Baran J. The case of al-Shifa: investigating the assault on Gaza’s largest hospital. 2023. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/21/al-shifa-hospital-gaza-hamas-israel/ [Accessed 27 Dec 2023].

- 11. Abraham Y. A mass assassination factory: inside Israel’s calculated bombing of Gaza. 2023. Available: https://www.972mag.com/mass-assassination-factory-israel-calculated-bombing-gaza/ [Accessed 30 Nov 2023].

- 12. Jamaluddine Z, Checchi F, Campbell OMR. Excess mortality in Gaza: Oct 7-26. Lancet 2023;402:2189–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02640-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frankel J. Israel’s military campaign in Gaza seen as among the most destructive in recent history, experts say. 2023. Available: https://apnews.com/article/israel-gaza-bombs-destruction-death-toll-scope-419488c511f83c85baea22458472a796419488c511f83c85baea22458472a796 [Accessed 25 Dec 2023].

- 14. Wynia M. Health professionals and war in the Middle East. 2023;330(22):2155-2156. JAMA 2023;330:2155–6. 10.1001/jama.2023.24247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alser O, Gilbert M, Loubani T. Health care workers and war in the Middle East. JAMA 2023;331:77. 10.1001/jama.2023.26407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics . Almost half of the Palestinian society are children. 2023. Available: https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/portals/_pcbs/PressRelease/Press_En_ChildDayE2022.pdf [Accessed 30 Nov 2023].

- 17. AFP . Israel social security data reveals true picture of Oct 7 deaths. 2023. Available: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20231215-israel-social-security-data-reveals-true-picture-of-oct-7-deaths [Accessed 25 Dec 2023].

- 18. International Court of Justice . 26 January 2024 order; application of the convention of the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide in the Gaza strip (South Africa v. Israel). Available: https://icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/192/192-20240126-ord-01-00-en.pdf [Accessed 26 Apr 2024].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2023-014756supp001.pdf (90.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp002.pdf (47.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp003.pdf (58.1KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp004.csv (235B, csv)

bmjgh-2023-014756supp005.csv (2.8KB, csv)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information (online supplemental files 3–5)