Abstract

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the social conditions in which people are born, live, and work. SDOH offers a more inclusive view of how environment, geographic location, neighborhoods, access to health care, nutrition, socioeconomics, and so on are critical in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. SDOH will continue to increase in relevance and integration of patient management, thus, applying the information herein to clinical and health systems will become increasingly commonplace. This state-of-the-art review covers the 5 domains of SDOH, including economic stability, education, health care access and quality, social and community context, and neighborhood and built environment. Recognizing and addressing SDOH is an important step toward achieving equity in cardiovascular care. We discuss each SDOH within the context of cardiovascular disease, how they can be assessed by clinicians and within health care systems, and key strategies for clinicians and health care systems to address these SDOH. Summaries of these tools and key strategies are provided.

Keywords: built environment, community, economic stability, education, health care access, social environment

The United States’ focus on reducing health disparities primarily based on race and gender intensified after the Healthy People 2010 initiative. The World Health Organization introduced the term social determinants of health (SDOH) in 2003.1 SDOH are the social conditions in which people are born, live, and work. SDOH offers a more inclusive view of how environment, geographic location, neighborhoods, access to health care, nutrition, socioeconomics, and so on are critical in morbidity and mortality.

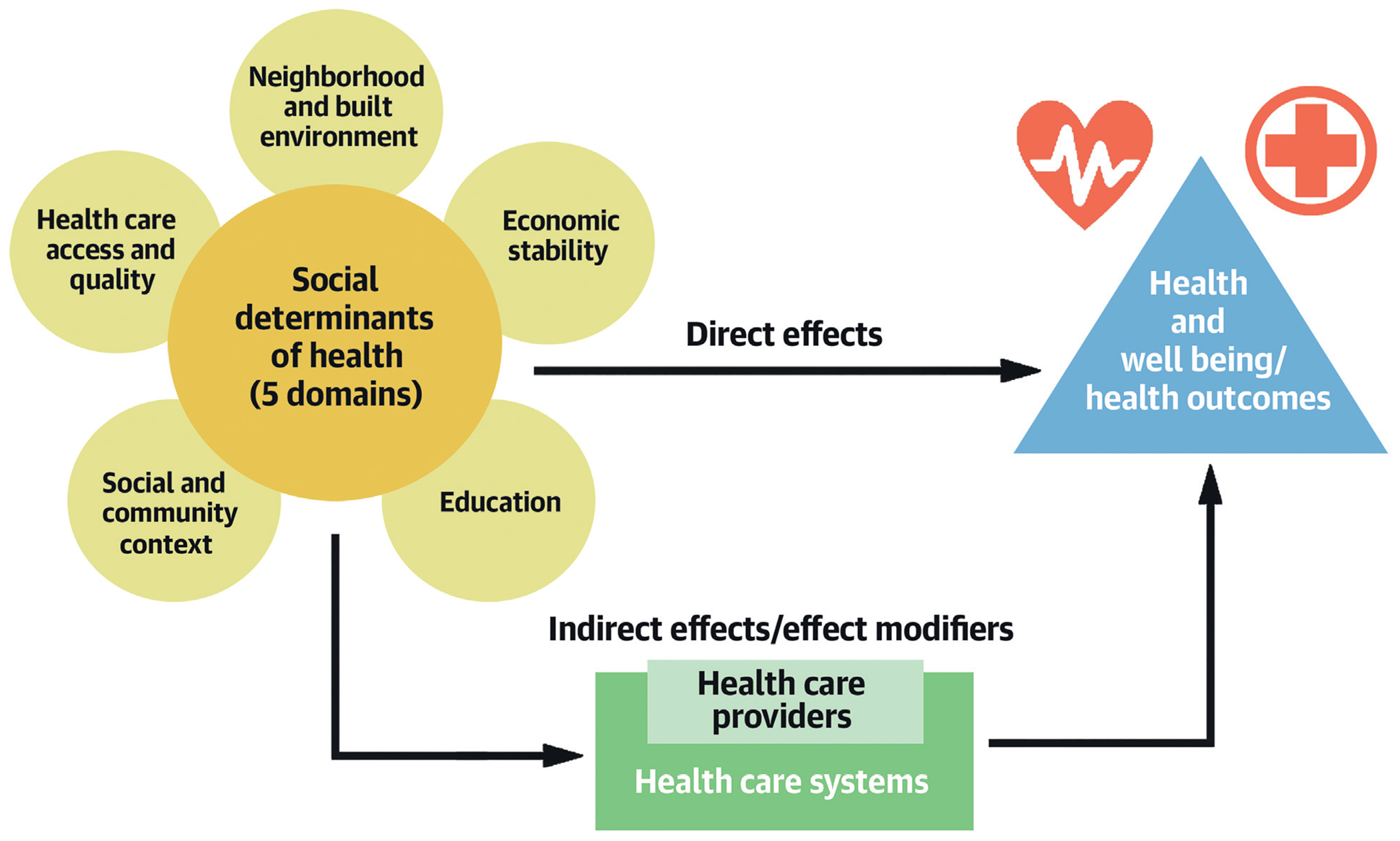

The 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) recommends that clinicians evaluate SDOH to inform treatment decisions.2 Addressing SDOH requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes individual clinician visits and health systems. It requires us to overcome our biases and treat all patients with dignity and respect while becoming culturally competent and sensitive. This paper provides an overview of the impact of individual SDOH on cardiovascular health outcomes. We discuss how to assess SDOH and how to address SDOH within clinical settings and health systems. We work within a modified World Health Organization framework of SDOH and discuss how health care providers and health systems intersect with SDOH and health outcomes (Central Illustration). We cover commonly recognized SDOH (Table 1), which are categorized into the 5 SDOH domains recognized in U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People 2030: economic stability, education, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment (the physical infrastructure of one’s community), and social and community context.3 This paper aims to guide health care professionals who will need to address SDOH as major drivers of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including providing summaries of SDOH assessment tools (Table 2) and key strategies on addressing SDOH in health systems (Table 3).

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Health Through Health Care Providers and Systems.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health People 2030 recognizes 5 domains of social determinants of health, including economic stability, education, health care access and quality, social and community context, and neighborhood and built environment. The World Health Organization framework of social determinants of health recognizes that these social determinants of health directly and indirectly impact health and well-being as well as health outcomes. Both health care providers and the health system can act as indirect modifiers for how these social determinants of health impact health, well-being, and health outcomes.

TABLE 1.

Social Determinants of Health Within the 5 Domains Recognized by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People 2030

| Domain | Subdomain |

|---|---|

| Economic stability | Economic stability |

| Education | Education/health literacy |

| Healthcare access and quality | Primary care access |

| Neighborhood and built environment | Housing Tobacco Physical activity Racial segregation Transportation |

| Social and community context | Internet access/telemedicine Rurality Sex and gender Social inclusion Food and nutrition insecurity |

TABLE 2.

Summary of Social Determinants of Health Adverse Outcomes, Documentation Codes, and Assessment Tools

| Social Determinant of Health | Associated Adverse Outcomes of Being Impacted by SDOH | Documentation Codes (Z-codes) | Name and Reference for Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic stability | ↓ lifespan ↑ prevalence of CVD, diabetes, and obesity ↓ healthy food purchases ↓ less guideline-recommended therapies to managed CVD (statins, beta-blockers, cardiac rehabilitation) |

Z56: problems related to education and literacy (several subcategories) Z59: problems related to housing and economic circumstances (Z59.5: extreme poverty, Z59.6: low income, Z59.7: insufficient social insurance and welfare support) |

Medicare and Medicaid Innovation - Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool102 |

| Education access and quality | ↑ acute myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, sudden cardiac death, all-cause mortality ↓ medication adherence |

Z55: problems related to education and literacy (several subcategories) | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported tools: 1. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Literacy Measurement Tools21 2. TheHealth Literacy Tool Shed22 Health Literacy and Cardiovascular Disease: Fundamental Relevance to Primary and Secondary Prevention: a Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association23 |

| Housing | ↓ overall physical and mental health ↑ odds for developing CVD and CV death ↑ prevalence CVD risk factors |

Z59: problems related to housing and economic circumstances (Z59.0: homelessness; Z59.1: inadequate housing | Medicare and Medicaid - 10-item Screening Tool30 |

| Tobacco | ↑ heart disease, stroke, many cancers, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other lung diseases, adverse pregnancy outcomes, death (note these may not be limited to first hand exposure only) | Z72.0: tobacco use Z57.31: occupational exposure to environmental tobacco smoke |

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence103 Time to First Cigarette34 |

| Physical Activity | ↑ diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, CVD | Z72.3: lack of physical exercise | International Physical Activity Questionnaires104 Modifiable Activity Questionnaire105 Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire106 Previous Day Physical Activity Recall107 |

| Racial segregation | ↑ social vulnerability secondary to historic redlining practices into less desirable locations with less public funding/attention • ↓ cholesterol screening and clinical follow-up • ↑ uninsured • ↑ cardiometabolic risk factors (obesity, tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes) • ↑ coronary artery disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease Racism included ↑ inflammation (C-reactive protein), adverse epigenetic changes, and hormonal response |

Z60: problems related to social environment (Z60.3 - acculturation difficulty; Z60.5 target of [perceived] adverse discrimination and persecution) | Social Vulnerability index108 |

| Transportation | ↓ timeliness of care, access to care | Z75.3: unavailability and inaccessibility of health-care facilities Z75.4: unavailability and inaccessibility of other helping agencies |

Kaiser Permanente tool61 The Transportation Security Index109 |

| Internet access/telemedicine | Telehealth access can: • ↓ HF hospitalization • ↑ atrial fibrillation monitoring to promote improve rate control • ↓ barriers to care: wait time, travel, time off work, childcare needs |

Z60: problems related to social environment | TeleCheck-AF110 Digitally Empowered71 Maryland Health commission-Telehealth readiness assessment72 Preparing for a Virtual Visit (Department of Health and Human Services73 |

| Sex and gender | CVD is the leading cause of death in pregnancy • ↓ delivery of CV care to women and socially disadvantaged groups • ↑ myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolic disease among transgendered people Women-specific factors: • ↑ mortality after CV events compared to men • ↓ recognition of women-specific CV risk factors |

Z70: counseling related to sexual attitude, behavior and orientation | Human Rights Campaign’s Glossary of Terms for Sexual Orientation and Gender Expressions)111 |

| Social inclusion | ↑ premature mortality, smoking, blood pressure ↓ physical activity |

Z60: problems related to social environment (Z60.2: problems related to living alone; Z60.4: social exclusion and rejection) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale112 De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale113 Campaign to End Loneliness Measurement89 Lubben Social Network Scale114 Berkman-Syme Social Network Index115 |

| Food and nutrition insecurity | ↑ CVD and CVD risk factors: diabetes, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia ↓ quality diet |

Z59 (Z59.4: lack of adequate food; Z59.48: other specific lack of adequate food) | Two Question Food Insecurity Screener116 |

There are proposed changes to these Z-codes, including addition of new Z-codes to better define social determinants of health.

CV = cardiovascular; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HF = heart failure; SDOH = social determinants of health.

TABLE 3.

Summary of Key Strategies for Health Care Systems to Address Social Determinants of Health

| Social Determinant of Health | Key Health System Strategy | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Economic stability | Anticipate being an active partner in addressing economic stability Launch initiatives within the community leaders to improve economic stability |

Oregon state providers collaborate with meals on wheels to deliver meals to recently discharged patients New York and Louisiana: development of programs to support retainment of stable housing Requirements from Managed Care Organization funded effort toward housing stability and food insecurity Affordable Care Act community benefits toward community groups and community building activities |

| Education access and quality | Work toward achieving AHRQ suggested attributes of a health literate health care organization | Evaluating the health system population to determine health literacy needs Provide health literacy education to hospital staff and appropriate materials for staff and patients Collaborate with local communities to form programs centered on increasing health literacy or increasing high school graduation rates |

| Health care access and quality | Improve local primary care access, which may improve referral and access to specialists | Decreasing proximities to primary care services in low-income urban areas and increasing number of rural outreach clinics Focus primary care within the patient centered medical home |

| Housing | Enhancing understanding of community resources and creating partnerships to address unique local housing circumstances | Provide financial support to organizations that house homeless people Developing or partnering with medical respite programs |

| Tobacco | Promote well-coordinated interventions with dedicated policies/standards of practice | Implementing tobacco user identification at each health care encounter Advocating for increase coverage of tobacco-dependence treatments Participating in programs that provide financial incentives for tobacco cessation |

| Physical activity | Support multidisciplinary teams that can provide physical activity recommendations/support (exercise physiologist, nutritionists, social workers) | Multidisciplinary fitness programs that help manage patients with cardiometabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease (eg, the University of Michigan Metabolic Fitness program) |

| Racial segregation | Develop initiative to dismantle institutional racism in pursuit for equitable health outcome Increasing understanding of community needs and barriers to equitable care |

Partnership with nontraditional treatment locations to provide medical care (eg, barbershops and faith-based centers to manage hypertension) CommunityRx - e-prescribing system that connects patients to health promoting community resources Increasing workforce and trainee diversity |

| Transportation | Invest in programs to address transportation needs in disadvantaged patients Invest in nontraditional methods for patient interaction (see internet access/telemedicine) |

• The Veterans Health Administration provides transportation for their patients to get to routine local appointments or care in other regions for unavailable local specialty care • Mobile health programs provide in-community care • Decrease need for multiple transportations for care management (eg, same-day PCI, or coordinate computed tomography and echo scan on same day before TAVR) |

| Internet access/telemedicine | Advocate against reducing reimbursements for telehealth encounters | Collaborating with payors to address access to telemedicine, mobile health technology, and asynchronous communications Align with novel technologies to improve patient outcomes (eg, telehealth visits for frequent HF follow-up, telecheck for atrial fibrillation monitoring) Use of community benefit to partner with program to improve broadband to low internet access communities Provide resources (eg, Digitally Empowered) and guides (eg, the DHHS telehealth guide) for patients to participate in virtual care |

| Rurality | Recognize rurality’s interaction with other SDOH | Improve care access through aforementioned transportation and telehealth examples |

| Sex and gender | Develop policies/programs to improve equity in care across sex and gender | Establishing a dedicated Women’s CV prevention clinic Provide curricula on understanding needs of transgender patients Increasing workforce and trainee diversity |

| Social isolation | Develop a systematic approach and plan that will identify people at high risk for social isolation | Routine identification of socially isolated individuals and standard resources for management Expansion of telehealth resources Expansion of social media utilization targeted toward locally communities |

| Food and nutrition insecurity | Ensure eligible patients for federal and local food programs are actively enrolled Develop programs and collaborate with other community resources |

Provide Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program enrollment information Provide local food resources (pantries, double-up food bucks participants, produce prescriptions) In-clinic food pantries Participation in state programs to utilize “food is medicine” into medicine, such as with medically tailored meals (Massachusetts, California) or partnerships with Meals on Wheels (Oregon) |

AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; DHHS = Department of Health and Human Services; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; other abbreviations as in Table 2.

ECONOMIC STABILITY

Economic stability is a person’s ability to possess, maintain, or acquire the necessary resources for a healthy life. Income and financial health (ie, expenses, debt) are the strongest and most well-studied factors. Other factors include employment and work environment (ie, worker protections, paid sick leave, child-care services).

Lower household income has been associated with purchasing fewer healthy foods,4 engaging in less physical activity,5 and higher prevalence of CVD, diabetes, and obesity.6 Using 1.4 billion deidentified U.S. tax records (1999-2014), lower income was associated with a 14.6-year (95% CI: 14.4-year to 14.8-year) shorter lifespan for men and 10.1-year (95% CI: 9.9-year to 10.3-year) shorter for women between the poorest and richest individuals.7 Difference can be seen even at the neighborhood level; every $10,000 increase in neighborhood median income is associated with a 10% reduction in mortality from acute myocardial infarction (AMI).8 Differences in mortality may be attributed to access to care because residents in lower income areas are less likely to receive cardiac catheterization within 24 hours of acute coronary syndromes.9 Moreover, patients at lower income levels are less likely to receive guideline-recommended therapies such as statins and beta-blockers.10

Employment status is another strong predictor of CVD. Within the first year of unemployment, there was a 35% increased risk for an AMI (95% CI: 10%-66%, adjusted for socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical variables) and the longer the unemployment, the higher the risk.11 Similarly, there was a 20% (95% CI: 4%-39%) increase in risk of cardiovascular events in an unemployed person without pre-existing CVD living in France after adjustment for demographic and behavioral factors.12 Although these studies are informative, the observational nature makes it unclear if income-related factors are additive or synergistic.

ASSESSMENT.

Economic stability is not often discussed during clinic appointments. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation has created the health-related social needs (HRSN) screening tool, which enables health care and social services providers to screen for economic instability.13 As of July 2021, 29 organizations are participating in the Accountable Health Communities Model, a program designed to test whether systematically addressing needs identified by the HRSN survey will decrease health care costs and utilization. These organizations have screened patients using the HRSN survey and randomized patients to community service referrals only (control group); community referrals plus assistance to access community services (Assistance Track); or community service referrals, assistance to services, and assurance of community responsiveness to requests (Alignment Track). From 2017-2020, among 482,967 participants screened, 34% had ≥1 health resource social need. Having 2 to 4 HRSN was associated with more emergency department (ED) visits (OR: 1.8-9.5).14 Navigation-eligible beneficiaries were more likely to be low income, racial and ethnic minorities, and (among Medicaid beneficiaries) disabled. In the first year, those randomized to the Assistance Track had 9% fewer ED visits. Clearly, social needs assessments can be made actionable and impactful with appropriate support.

CLINICAL AND HEALTH CARE SYSTEM ACTIONS.

Clinicians should begin by incorporating assessments of economic stability, such as by using the HRSN screening tool. Those having HRSNs can be referred to appropriate programs within the health care organization or community. Alternatively, clinicians can simply ask about employment or if their income meets basic food, shelter, and health needs. If employment or income limitations concerns arise, then the patient can be connected to social services for appropriate support.

Health care systems should anticipate being active partners in addressing economic stability. State Medicaid programs have launched initiatives to improve economic stability. In Oregon, providers work with Meals on Wheels to deliver meals to recently discharged patients who may need food delivery as part of their recovery. New York and Louisiana have started programs to support housing-related activities that connect and retain individuals in stable housing. Finally, several states (Arizona, Massachusetts, and California) are requiring Medicaid Managed Care Organizations to address economic instability, especially housing and food security. Furthermore, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires nonprofit hospitals to provide a community benefit. A large portion of these are allocated to financial assistance (mostly to fund unreimbursed care, at 6.4% of tax-exempt hospital expenses) and only a small portion contributing to community groups (0.4%) or community-building activities (0.1%).15 A reallocation of more funds to support community groups and community-building activities could help to alleviate financial barriers to care.

EDUCATION ACCESS AND QUALITY

Limited education, which leads to reduced health literacy, may prevent people from using medications properly and navigating health services.16 In general, lower educational level is associated with higher risk for AMI, coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure (HF), all-cause mortality, and sudden cardiac death.17-19 However, it is important to acknowledge the diminished returns of higher education among racially minoritized communities, such as non-Hispanic Black people, whose experiences with chronic discrimination may supersede the protective effects of higher education.20

ASSESSMENT.

Multiple screening tools are available for clinicians to assess education or reduced health literacy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report 2 tools to measure health literacy in adults. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Literacy measurement tools measures English and Spanish speaking individuals’ reading comprehension in a medical context.21 Second, the Health Literacy Tool Shed is an online database of health literacy measures including their psychometric properties.22 Each tool will systematically evaluate and compare the understandability and actionability of patients to medical educational materials. The choice of tool applied should be determined based on patient population characteristics and time availability.

CLINICAL AND HEALTH CARE SYSTEM ACTIONS.

The provider should always be aware and try to understand the patient’s level of health literacy. As an example of its importance, someone with poor health literacy with hypertension may take medication irregularly or inappropriately. As part of overcoming this, providers should adopt teaching methods that may enhance patient understanding or health literacy. This includes using open-ended questions or teach-back methods. Other actions include empowering patients and promoting attendance of health literacy classes or other courses (eg, guided smoking cessation classes rather than tackling materials alone). A recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association provides additional detailed strategies to address health literacy–induced barriers to CVD management, including strategies related to informed consent.23

Health systems can play a role in improving health literacy by developing pathways to simplify health educational information and integration of comprehensive health literacy checks during patient interactions. Health systems can collaborate with local communities for their community health action requirements to form programs centered on increasing health literacy. For example, because increasing education level is tied to health literacy, partnering in programs to enhance high school graduation is an important step in promoting health equity. Additionally, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality suggests a list of 10 attributes of a health literate health care organization that can be used as a toolkit for evolving health systems, which include understanding and meeting the needs of the population served and ensuring that the workforce is educated on strategies to promote health literacy, among others.24

HEALTH CARE ACCESS AND QUALITY

PRIMARY CARE ACCESS (ADULT AND PEDIATRIC).

Primary care provider (PCP) utilization is on the decline (−24% between 2008 and 2016), especially among young adults and those in low-income areas.25 Improving access to PCPs is critical in the delivery of health services, especially given the increasing burden of preventable chronic disease. Primary health care services are also important in facilitating access to specialty care and linking families with important resources (eg, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP] and healthy parenting skills). New models of health care delivery that emphasize better integration between primary and specialty care are being proposed. These health care delivery models are less likely to be successful if SDOH are not addressed holistically. A patient-centered system of care that ensures timely access to specialty care for the patient by addressing SDOH is therefore desirable.

Although pediatrics is not the primary focus of this paper, primary care’s role in assessing SDOH is critical for children with congenital heart disease. Lower socioeconomic status was associated with decreased prenatal diagnosis of and increased incidence of congenital heart disease and worse postoperative and neurodevelopmental outcomes.26

CLINICAL AND HEALTH CARE SYSTEM ACTIONS.

Primary care has an irreplaceable role for primordial CVD prevention. Screening and referral for PCP access should be incorporated into all health-related visits.

Health care systems can participate in initiatives that improve primary health care access. This can include programs that decrease proximity to PCP services and rural outreach clinics, which also may result in improved access to specialist care in remote locations. Further improvements may need to come from payment and insurance reforms, including expansion of medical insurance coverage for improved primary care access. The ACA partially addresses this by refocusing on population health management, accountable care organizations, and the patient-centered medical home. In the patient-centered medical home each patient has a PCP who provides care in a single health system with a team of support staff (eg, dietician, case manager, and so on). This addresses several aspects of continuity of care, information sharing, and case management for more holistic patient management.

NEIGHBORHOOD AND BUILT ENVIRONMENT

HOUSING.

For this review, the term “housing instability” includes homelessness, poor housing quality, or difficulty paying mortgage or rent. Housing instability is a worsening nationwide phenomenon with structural economic causes. The prevalence of CVD risk factors and odds of developing CVD are higher among individuals facing housing unaffordability.27 Among adults experiencing housing instability, CVD is also a major cause of death; adults with unstable housing have 2 to 3 times higher CVD mortality than the general population.28 Given the rising prevalence, clinicians will increasingly encounter patients with concurrent housing instability and CVD.

Assessment.

Housing instability can and should be addressed in the clinical setting. The population of housing-unstable individuals is large and heterogeneous; thus, experts recommend universal screening.29 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed a 10-item screening tool to identify patient needs that can be addressed through community services.30 Two of these items address housing instability: “What is your housing situation today” and “Think about the place you live. Do you have problems with any of the following,” with answer options ranging from “bug infestation” to “water leaks.” These questions may identify beneficiaries experiencing homelessness and poor-quality housing. Outside of screening, if housing issues emerge during the clinical interaction, it is critical that clinicians ask open-ended questions and attempt to understand living situations.

Clinical and health care system actions.

If a patient screens positive for housing instability, clinicians can perform several actions. For chronic CVDs requiring frequent medication titration, simplifying drug regimens may reduce treatment burdens. Housing-unstable patients often face difficult tradeoffs between housing and other basic necessities. Clinicians should be attuned to these tradeoffs when providing CVD-specific education with anticipatory guidance geared toward the unique circumstances of housing-unstable individuals. One example involves instructing patients regarding diuretic titration or recognition of changes in HF symptomatology in the absence of reliable access to objective measures (eg, daily weight).31 Also, researchers have long recognized the importance of provider language in shaping attitudes and treatment decisions in stigmatized conditions. It is imperative that clinicians employ nonstigmatizing discourse when interacting with housing-unstable patients to engender mutual respect and trust.31

For homeless patients in particular, health systems often struggle in providing complete care, because these patients often lack a stable discharge destination. Health systems may partner with community housing providers, providing critical financial support to these organizations that can fulfill their ACA required community health benefit. Creating safe discharge destinations for homeless patients may ease the burden on hospitals and EDs. Medical respite programs are another example of a safe discharge location. These medically supervised environments, often located within the shelter system, have been successfully established in localities across the United States in partnership with health systems. Medical respite programs are associated with lower hospital readmission rates and may ease patients’ recovery after cardiac procedures.28 Patients hospitalized for HF and discharged to medical respite can regain a sense of stability, form routines around health-related behaviors, and experience freedom from difficult tradeoffs.31

TOBACCO.

Tobacco use causes heart disease, stroke, multiple cancers, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, among other diseases.32 In 2020, tobacco use in the United States continued to decline at 19.0%, with cigarettes (12.5%) and e-cigarettes (3.7%) as the most common forms.33 Tobacco use was most prevalent among men (24.5%); 25- to 44-year-olds (22.9%); American Indian/Alaskan Native non-Hispanic individuals (34.9%); rural-dwellers (27.3%); low-income earners (<$35,000 annually; 25.2%); those with lower education attained (40% with GED and 24.8% with no high school diploma); those identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (25.1%); or those with a disability (25.4%).33

Assessment.

Tobacco use can be in the form of cigarettes, vapes, bidis, cigars, pipes, hookahs, chewing tobacco, and snuff, among other forms. The U.S. Public Health Services’ Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline recommends tobacco use to be addressed by every clinician, for every patient, at every single visit.32 Given the higher prevalence of smoking in communities already at high risk for marginalization, cultural sensitivity is critical in this process.

Tobacco dependence can also be assessed to guide management. Time from awakening to first cigarette predicts abstinence and latency to first relapse after cessation attempt.34 Time to first cigarette <30 minutes is associated with greater likelihood of lapse, despite control of cigarettes smoked per day and craving.35

Clinical and health care system actions.

Clinicians interact with >70% of smokers annually, often with multiple missed opportunities to screen, despite the majority of tobacco users being willing to quit.32,36 The U.S. Public Health Services suggests application of the “5 A’s” model (ask, advice, assess, assist, arrange).32 For example, once asked, a tobacco user should be advised to quit in a personalized manner. Once willingness to quit is assessed, the clinician should help set a quit date, instruct on telling families and friends, anticipate challenges, and suggest removing all tobacco products. Assistance using medications, practical counseling, and reading material should be provided. Follow-up is then arranged.

The health system’s critical role is to promote well-coordinated interventions with dedicated health care policies. For instance, insurance coverage of tobacco-dependence treatment increases the likelihood of tobacco cessation.37 Additionally, institutional policies may facilitate interventions for tobacco dependence, including implementing a tobacco-user identification for patient visits and providing training, resources, and feedback for consistent delivery of treatments.37 Further, the combination of patient navigation and financial incentives for quitting increased the likelihood of sustained biochemically confirmed smoking cessation, especially among elderly (19.8% vs 1.0%), women (16.8% vs 2.2%), low household income (15.5% vs 3.1%), and non-White participants (15.2% vs 3.0%; all P < 0.01).38

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY.

Benefits to performing recommended levels of physical activity (PA) include prevention of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CVD, among others. It is recommended that adults perform 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic PA per week and muscle-strengthening exercises at least twice per week.39 Yet, <50% of U.S. adults achieve aerobic PA recommendations, <25% achieve strengthening exercise recommendations, and about 20% meet both goals.39 There are differences in PA among racial and ethnic groups. The CDC 2018 National Health Information Survey reported that non-Hispanic White men (60.6%) and women (54.7%) had the highest rates of achieving PA recommendations, followed by non-Hispanic Black men (53.3%) and women (40.5%), and Hispanic men (51.7%) and Hispanic women (43.2%).39

There are multilevel barriers to achieving PA goals, which can be categorized into 3 domains of a social ecological framework: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community/environmental factors.40 Intrapersonal factors include lack of knowledge regarding PA (eg, unaware of recommendations), inability to afford exercise facilities, lack access to transportation/time, or be unmotivated.40 Interpersonal factors include social relationships and their cultural norms (eg, lack of workout partners, time to participate because of family needs).41 Community/environmental factors (ie, the built environment) play a particularly important role in PA. Communities with poorer built environments to support PA have significant disparities in PA participation.40,41 The extent of the impact of the built environment on PA and the variable impact between communities is the subject of ongoing research and interventions.

Assessment.

With multilevel potential barriers to PA, it is essential to obtain a comprehensive assessment, including a determination of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community/environmental factors. Baseline activity levels can be assessed either through formal exercise programs or with review of daily activities. PA can be assessed by self-reported surveys: International PA Questionnaires, Modifiable Activity Questionnaire, Recent PA Questionnaire, Previous Day PA Recall, and Previous Week Modifiable Activity Questionnaire.42 Wearable fitness device data such as from pedometers, accelerometers, heart rate monitors, and armbands can also be reviewed to assess PA.

Clinical and health care system actions.

Health coaches can be utilized to create customized plans taking into consideration individual circumstances, especially one’s built environment, which can result in sustained weight loss in underserved populations.43 Clinicians can also determine eligibility for prescription PA programs. Medicare beneficiaries over 65 years of age may qualify for enrollment in low or no-cost Silver Sneakers exercise classes.44 Additionally, community centers (eg, YMCA, senior centers) have PA facilities available at a reduced cost through insurance providers and help overcome barriers of unsafe exercise environments within some communities. For those with qualifying diagnoses, referral to cardiac rehabilitation and physical therapy for cardiac conditioning can be considered (see example in the following text). In the context of built environments, safe exercise can be promoted by suggesting to exercise in well-lit areas with sidewalks/pathways that avoid dangers from traffic, considering exercising near their work-site instead of home (if safer), or pursuing in-home exercise activities.39

Health care systems can also play a role in enhancing PA through applying a multidisciplinary approach. This approach includes a comprehensive assessment of patients’ PA participation and screening for the multilevel barriers to achieving PA targets by health care providers, then integrating referral to appropriate care providers.45 This includes exercise therapists who can provide routine assessment of physical limitations and recommendations for individualized PA programs.44 Nutritionists can provide dietary counseling and recommendations based on metabolic requirements. In addition, social workers or community health workers can work closely with individual patients to understand the safety of their built environments. Behavioral counselors can follow-up on PA activities and address barriers. In this manner, health care systems can fill knowledge gaps and improve long-term sustainable PA. One example is University of Michigan’s Metabolic Fitness Program, which takes place within cardiac rehabilitation facilities and includes exercise physiologists for PA recommendations and monitoring, nutritionist-designed dietary materials and classes, and a behavioral/stress management curricula.46 This program has resulted in decreased weight, waist circumference, blood pressure (BP), triglycerides, glucose in diabetic patients, and depressive symptoms; overall 19.4% no longer qualified for metabolic syndrome.

RACIAL SEGREGATION.

Among people of color, especially non-Hispanic Black families, racial segregation is exemplified by the historical practice of redlining (denying a home loan to a credit-worthy applicant for perceived racial or ethnic association). In the past, under the guise of “stabilizing the housing market,” the Home Owners Loan Corporation classified neighborhoods using a color system. “Redlined” districts were considered high lending risk, and appraisers were discouraged from insuring these mortgages. It was no coincidence that redlined neighborhoods were inhabited by non-Hispanic Black families. Redlining steered families who identify as Black, Indigenous, and people of color, prevented their upward mobility, and effectively segregated communities—often physically with a highway. Although redlining based on racial grounds is now illegal, examples of housing discrimination continue to exist.

The legacy of this unethical approach is an example of systemic racism, which has contributed to segregation, wealth gaps, and disparate health outcomes. The CDC has mapped these areas via a social vulnerability index. Demographic data have revealed higher rates of CVD among those living in lower socioeconomic status “redlined” communities.47 Redlined districts, which were disproportionately non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic, were found to have lower cholesterol screening and clinical follow-up, higher uninsured, and higher cardiometabolic risk factors (eg, obesity, tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes). Hard outcomes (coronary artery disease, stroke, and chronic kidney disease) were also increased. These findings are possibly related to factors of the built environment (eg, air pollution, public transit access, proximity to clinics, green spaces, grocery stores).48 In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, individuals living in redlined neighborhoods had lower cardiovascular health scores. Social environment modified the strength of association, wherein neighborhoods with strong social environments had weaker (but still statistically significant) associations between cardiovascular health and Home Owners Loan Corporation grade.49

Systemic racism has unique influences on the health outcomes of American Indian and Alaskan Native patients. One-quarter of the American Indian and Alaskan Native population live below the federal poverty line—a rate 143% higher than non-Hispanic White populations. Many of these individuals are uninsured. Access to healthy food and traditional tribal food sources on reservation land is often limited. The nutritional deficits of Native populations trace back to forced relocation of tribes and subsequent reliance on the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations that distributes heavily processed and nutrient-poor foods.50 Finally, access to care is severely limited. Despite 60% of American Indian and Alaskan Native individuals living outside of their home reservation, the Indian Health Service funds <1% of health care outside reservation land, forcing patients to drive long distances.51

Racism has additional effects outside of the direct impact from the built environment. Racial discrimination and race-related stress is associated with an inflammatory response that can increase likelihood of developing atherosclerosis. Higher rates of inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein have been observed among non-Hispanic Black individuals who self-report experiences of discrimination.52 Adverse childhood experiences, which disproportionately affect children of racial and ethnic subpopulations, also increase risk of developing CVD, likely via increased inflammatory stress response, epigenetic and hormonal changes, and depression.53

Clinical and health care system actions.

Racial disparities in CVD are deeply rooted in systemic racism and generational trauma. It is imperative to understand this historical context to provide culturally competent care and effectively partner with patients to enact individualized and sustainable treatment plans. Given the numerous SDOH that complicate access to care, adopting a multidisciplinary approach to ensure carry-through of the plan outside the clinic is important. For example, the CDC’s WISEWOMAN program for clinics serving low-income and underinsured women age 40 to 64 years.54 WISEWOMAN provides funding to institute a series of strategies (ie, a team-based approach with pharmacists, health coaches, and so on) to inspire patient buy-in and ensure appropriate follow-up and timely interventions, which has resulted in improved hypertension control.

On a health systems level, understanding the needs of one’s community of patients and their barriers to care can give way to meaningful social programs. Clinical studies have shown that moving care such as hypertension management into nontraditional treatment locations, such as barbershops (22 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP) and faith-based centers (5.8 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP), is one way health systems may provide care through trusted community partners.55 Furthermore, CommunityRx is an innovative e-prescribing system for health systems that connects patients to health promoting community resources. Data from CommunityRx corresponding to geographic neighborhoods of patients can reveal specific community needs.56 For example, data from CommunityRx that shows a predominance of “prescriptions” to local dieticians and fresh food markets may indicate a higher rate of obesity and a need for healthy food options in that neighborhood.

Finally, advocating to dismantle institutional racism is central to our pursuit for equitable health care outcomes. As demonstrated in this paper, numerous SDOH instrumental to the development of CVD are the consequence of systemic racism. Promoting diversity within medicine and fostering a workforce that more accurately mirrors that of our patient population is of utmost importance to closing the gaps that exist between our current medical system and our Black, Indigenous, and people of color patient populations.57 Project Dulce provided one example; diabetes care was provided to Hispanic/Latino participants through a nurse-led team of bilingual/bicultural diabetes educators, medical assistants, and dieticians who trained patient leaders as peer educators, with 1-year improved diabetes (hemoglobin A1c from 12.0% to 8.3%) and lipid control (LDL from 3.35 to 2.79 mmol/L).58

TRANSPORTATION.

Access to transportation is an essential component of timely and appropriate health care. Transportation barriers delay medical care with disproportionate effects on the elderly, racial and ethnic minority groups, lower socioeconomic status individuals, under/uninsured, and rural residents.59 Transportation-disadvantaged individuals may face challenges to attending clinic visits, seeking hospital care, refilling prescriptions, obtaining diagnostic studies, and fulfilling exercise recommendations, among others.59

Assessment.

Assessment can start with a single question about whether transportation barriers limit access to medical care.60 Another example, from the Kaiser Permanente tool, asks about both the financial burden of transportation and whether transportation barriers affect access to medical care, picking up medications, and activities of daily living, with the opportunity to request transportation assistance.61 If screening is positive, this can prompt a more in-depth assessment as needed, such as with the validated Transportation Security Index.62

Clinical and health care system actions.

If transportation is a barrier, the clinician should intentionally align care to limit trips. Coordinating across departments to condense the anticipated work-up can prevent multiple trips and minimize loss to follow-up. The clinic model can also be restructured so that multiple needs are met in a single visit (eg, labs and imaging coordinated the day of the visit). For example, one model incorporated into routine care is the practice of ordering computed tomography scans and echo imaging the day before a scheduled transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Health care systems can also invest in programs to address transportation limitations, including transportation assistance, community-based point-of-care, and building robust virtual visit programs. For example, the Veterans Health Administration provides a van transportation program and will cover airfare (and transportation) to receive locally unavailable specialty care. The Veterans Health Administration has also used telehealth for decades to minimize transportation barriers for patients requiring chronic disease monitoring, with consequent reductions in no-shows and ED visits.63 Mobile health programs can also further facilitate access to care. Support for clinical programs, such as same day percutaneous coronary intervention, can eliminate the need for an accompanying driver to stay overnight. There are also models for community partnership (eg, volunteer programs or rideshare companies) that can expand the hospital’s capacity to fill transportation gaps. Additional discussion on telehealth, a natural remedy for some transportation limitations, are continued in the following text.

SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY CONTEXT

INTERNET ACCESS/TELEMEDICINE.

Outside of increasing access to outpatient visits and among several other examples, telemedicine was found to reduce 30-day hospitalizations for HF.64 Also, TeleCheck-AF, an on-demand mHealth intervention that remotely measures heart rate and rhythm initially developed for COVID-19, is used for remote atrial fibrillation control and atrial fibrillation ablation follow-up.65

A silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to broadly define telehealth tools to reduce health care disparities, although this remains unclear. Telemedicine may decrease wait times, travel, time off work, and childcare concerns, but telemedicine use lags among the elderly, non-English speakers, and technology impaired. Early findings are promising; a recent study shows that Medicare patients in poor neighborhoods benefited most from telehealth expansion during the pandemic. Those living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods had the highest odds of using telehealth services.66 Further research is needed to ensure that access to telemedicine will not worsen disparities.

Assessment.

Although there are many tools to assess the satisfaction and usability of telehealth,67 there are no specific validated tools to assess the skills and tools to use telemedicine. However, simply inquiring about whether a patient has a computer or smartphone with internet access, webcam, microphone, and ability to perform a virtual visit can be sufficient to understand whether virtual visits could be considered.

Clinical and health care system actions.

Clinicians should continue routine offerings for virtual visits because they may disrupt the limitations of in-person visits. Furthermore, asynchronous communications (ie, remote monitoring for hypertension) are other mobile health technologies that can deliver personalized dynamic interventions directly to patients in real-time to assist managing chronic diseases.68 Both virtual and asynchronous communications are increasingly billable encounters with similar reimbursement levels to in-person visits. Now that clinicians are set up for telehealth, clinicians should consider rapidly integrating it as a potential tool to disrupt health disparities. Our leaders must prioritize access and equity. A recent study shows an increase in telehealth implementation since COVID-19 with the adoption of payment parity by the Department of Health and Human Services, CMS, and Medicaid. This form of telecommunication has the potential to bridge a gap in health inequities and needs to be solidified within payment models.

Additional practices and policies that recognize and bridge digital divides are imperative. Health care systems can act as strong proponents against reducing reimbursements for telehealth over unfounded concerns of overuse. Furthermore, they can be advocates for its potential to address disparities, which is important because Black patients and Medicaid members had significantly higher odds of unsuccessful telemedicine visits.69 Because health systems must fulfill an ACA community health benefit, promoting community and corporate partnerships to improve broadband access and reversing policies that limit telehealth services is also key.

Several IT help apps or digital navigators help patients onboard to the virtual environment. Previsit checklists or forms can be filled by students, volunteers, or entrepreneurs, or a patient can phone a digital friend or a third party that logs into their computer and helps with check-in, download an app, or “share a screen.” Three-way calling is also available (eg, the Veteran Health Affairs’ Video Connect platform).70 Other health literacy tools, like Digitally Empowered, help patients become more tech-savvy to self-navigate virtual environments.71 Advocacy groups like the National Patient Advocate Foundation help patients work together with their clinical team members to maximize a telehealth visit. For small practices, the Telehealth Readiness Assessment from the Maryland Health Commission helps determine level of readiness and moving toward offering telehealth services.72 Last, comprehensive guides have been developed by the Department of Health and Human Services to help guide patients through the telehealth process.73

RURALITY.

Rurality, although not recognized as an individual subdomain within our paradigm, is a sociodemographic measure that plays into many of the other domains and subdomains described herein. It is estimated that 15% of the U.S. population lives in areas considered “rural”: areas that have low population density and are located outside of major metropolitan areas. Many studies over several decades have shown that significant disparities in health outcomes exist between rural and urban inhabitants. According to the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report Chartbook on Rural Healthcare, ischemic heart disease death rates are highest in the most rural counties where the death rates for rural men have been shown to be about 18% higher than in urban counties, and 20% higher for rural women.74 Blacks make up <8% of the rural population, but Blacks living in rural areas appear to be at particular risk for poor outcomes. Age-adjusted mortality rates in rural areas are substantially higher for Black adults compared with White adults.75

Clinical and health care system actions.

Rurality is a built-in sociodemographic that interacts with many other subdomains in this review. Readers should take care to review individual discussions on rurality within this paper, particularly the sections on primary care access, tobacco, transportation, and internet access/telemedicine.

SEX AND GENDER.

CVD has historically been believed to affect men more than women. Although awareness of CVD is on the rise, not all women have benefited equally in mortality reduction. CVD is the leading cause of death in pregnancy, and the postpartum period with higher rates of mortality among Black and lower socioeconomic status women.76 Inequities in the delivery of cardiovascular care have contributed to poor clinical outcomes and worsening CVD risk factors for women in socially disadvantaged subgroups. Many women-specific factors may go under-recognized, including polycystic ovary syndrome, menopause, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, among other differences in risk factors between men and women (Table 4).77,78 This may explain that although women usually have lower CVD incidence than men, women have a higher mortality rate and poorer prognosis following acute cardiovascular events.79 Other sex differences have been observed, including stroke types (women more likely to have cardioembolic strokes, men to have lacunar strokes), HF (women with higher incidence, hospitalization, and mortality), and abdominal aortic aneurysm (under-recognized, higher risk of rupture, and postoperative mortality).80,81

TABLE 4.

Differences in Risk Factors Between Men and Women

| Men > Women | Women > Men | Men-Specific Risks | Women-Specific Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Smoking | Testosterone | Menopause/hormone therapy related |

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Prostate cancer | Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Total cholesterol | Triglyceride | Testicular disease | Uterine disease |

| LDL cholesterol | HDL cholesterol | Breast cancer | |

| Gestational | |||

| Pregnancy related |

HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein.

Unlike sex, which is often defined based on biology, gender refers to the social and behavioral expression on the spectrums of masculinity and femininity, and is also a key SDOH. Although many people identify with the gender based on their sex assigned at birth (eg, man or woman), it is important to acknowledge the population of individuals who identify with a different gender or who transition to a different gender (eg, transgender man or woman). There is a small but limited literature examining the burden of CVD within this population, which suggests higher risk for AMI and venous thromboembolism.82 However, it is important to acknowledge the potential exposures to stress and discrimination that gendered minoritized groups may experience and their contribution to poorer CVD health.

Assessment and clinical and health care system action actions.

Sex and gender’s impact in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of CVD should be considered in every patient because the treatments of some diseases have considerable differences. However, these are not always taken into account when setting diagnostic criteria or surgical thresholds, which can lead to poor CVD outcomes. The characteristics of pregnancy-related disorders provide a unique opportunity for a better cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention.

There are several actions that could help bring positive changes to ensure equity in care across sex and gender. For example, establishing a dedicated women’s CVD prevention clinic. A diverse team of providers and staff can bring more value to how patients access care, especially if conscious and unconscious biases are considered and education is provided. As we consider the needs of transgender patients, it is important to consider implementing comprehensive curricula during medical training and clinical rotations to better understand the needs of this community.

SOCIAL INCLUSION.

Adults who have few social contacts or feel unhappy about their social relationship are at increased risk of premature mortality.83 Cardiovascular risk behaviors associated with loneliness and social isolation include low PA, smoking, and higher BP.84

Assessment.

Health care providers have an important role to play in acknowledging the importance of social isolation. Behforouz et al85 propose that clinicians should be encouraged to take a more indepth social history on all patients that includes topics relating to life circumstances and emotional health.86 Social isolation screening is more effective when multiple domains of social isolation are assessed. It has been reported that health care providers who feel at ease asking about social isolation during clinical care are more likely to address these issues with their patients.87 Therefore, appropriate comprehensive assessment is key to identifying people who may benefit from intervention. A variety of validated scales and measures exist to assess social isolation and related concepts (eg, loneliness, disconnectedness), which can prompt clinician action. For loneliness, validated assessment tools include the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale,88 and Campaign to End Loneliness Measurement Tool.89 For social support/connectedness, these include the Lubben Social Network Scale88 and Berkman-Syme Social Network Index.90

Clinical and health care system actions.

In patients found to be vulnerable for loneliness and social isolation, providers can discuss the impact it may have on their health outcome. In addition, providers may work with the social work team or public health worker to help with navigation of services that align with the needs of the patient.

Dozens of potential strategies have been studied to address social isolation, as outlined in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s report, “Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, Opportunities for the Health Care System.”91 A systematic approach wherein SDOH are routinely identified, including social isolation, can lead to a social prescription or a referral for specific resources from the health system or community organizations (eg, YMCA, adult day care programs, or behavior health services). In addition, health systems can identify this as a focus to fulfill their ACA-required community health benefit and enhance methods to decrease social isolation while working toward equitable care. Last, health systems could continue to expand the use of technology, including virtual care, which can help access those that are socially isolated caused by lack of transportation or being far from care resources (eg, rural-dwelling).

Social media has become another powerful tool for patient information, education, and advocacy. Clinicians and trainees have developed a myriad of content for medical education (often under ‘#MedEd’) on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. In 2022, the Pew Research Center published that 61% of older adults (age ≥65 years) and 96% of young adults (age 18-29 years) own a smartphone.92 Also, 45% of those older adults and 84% of young adults reported using social media. In a 2021 Pew report, 7 of 10 Twitter users reported getting their news and headlines on Twitter.93 These numbers suggest that social media is a viable platform for promoting public health information and cardiovascular health awareness in otherwise isolated individuals.

FOOD AND NUTRITION INSECURITY.

Food insecurity (FI) is “having limited or uncertain access to adequate food,” whereas nutrition insecurity (NI) is limited “availability, access, affordability, and utilization of foods and beverages that promote well-being and prevent and treat disease.”94 Adults experiencing FI have poorer-quality diets, including lower fruits and vegetables intake.95 Poorer quality diets can increase risk for developing CVD, likely via intermediary conditions like diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia.95 CVD remains the top cause of death in the United States, and diet is the greatest contributor to death from CVD, which suggests that those experiencing FI and NI likely shoulder an even greater burden from diet-related CVD.96 Often unrecognized in clinical settings, those with CVD (coronary artery disease, stroke, or HF) are twice as likely to experience FI.97 Fortunately, FI can be rapidly assessed and acted upon.

Assessment of FI.

The gold standard assessment of FI includes 18 questions. However, a 2-question FI screen has been validated: “Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more” and “Within the past 12 months the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”98 An affirmative response to either question is positive for FI.

Clinical and health care system actions.

Although additional research and quality improvement projects are needed to determine optimal ways to address FI and NI, tools are already available. FI and NI can be addressed through a team-based approach that incorporates clinicians, registered dietitians, social workers, case managers, or referral to state social service departments. Clinicians can make patients aware of within-system resources (eg, clinic food pantry, produce prescriptions) and refer to social workers or case managers for other local resources and whether they are eligible for government food programs (eg, SNAP, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children). It is not uncommon that someone is unaware they are SNAP eligible.

Identifying eligibility for a program may affect clinical outcomes. SNAP, the largest public food benefit program, decreases FI and associates with higher prescription adherence and lower medical costs and hospitalizations.99,100 If someone is participating in SNAP, they could utilize the Double Up Food Bucks program (active in 25 states), which allows participants to double SNAP dollars (≤$20/d) for fruits and vegetables. The Double Up Food Bucks program improves fruit and vegetable consumption and FI.101 We expect addressing FI and NI to increasingly become part of usual cardiovascular care, especially with the recent “food is medicine” push and investments that integrate nutrition into medicine (eg, Massachusetts’ and California’s medically tailored meals programs and Oregon’s partnerships with Meals on Wheels).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we reviewed key SDOH (which often overlap), their applicability to CVD, and how they can be addressed by clinicians and health care systems. Given that SDOH require broad approaches, a large investment is needed from health care systems in expanding personnel (eg, social workers) who are trained to link patients to SDOH-appropriate resources. Furthermore, addressing SDOH is complex and unique to local resources, and clinicians and health care systems should generate locally tailored plans or lists of resources to address them. To optimize the utility of these discussions, we provided a summary of the assessment tools and key strategies to address each SDOH (Tables 2 and 3). Alongside the assessment tools there are corresponding International Classification of Diseases-10th Revision Z-codes, which clinical providers can use in the electronic health record to document the presence of SDOH. Many health systems now prioritize the documentation of Z-codes because of the implications of SDOH on health outcomes like CVD. This coding practice can give way to meaningful public health interventions and systems actions, especially when SDOH data are used to anticipate patient needs and close care gaps. One can expect that SDOH will continue to increase in relevance and integration of patient management; thus, applying the information herein to clinical and health systems will become increasingly commonplace.

HIGHLIGHTS.

The social conditions in which people are born, live, and work have a broad impact on cardiovascular health, care, and outcomes.

Addressing these social determinants of health is an important step toward achieving equity in cardiovascular care.

Strategies are available for both clinicians and health systems to address each of the 5 domains underlying social determinants of health.

FUNDING SUPPORT AND AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATION AND ACRONYMS

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- BP

blood pressure

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- ED

emergency department

- FI

food insecurity

- HF

heart failure

- HRSN

health-related social needs

- NI

nutrition insecurity

- PA

physical activity

- PCP

primary care provider

- SDOH

social determinants of health

- SNAP

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Satcher D. Include a social determinants of health approach to reduce health inequities. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):6–7. 10.1177/00333549101250s402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;140: e563–e595. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

- 4.French SA, Tangney CC, Crane MM, Wang Y, Appelhans BM. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: the SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):231. 10.1186/s12889-019-6546-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong S, Wong CA, Perrin E, Page S, Sibley L, Skinner A. Association of physical activity with income, race/ethnicity, and sex among adolescents and young adults in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8):732–740. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S186–S196. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. 10.1001/jama.2016.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Killian JM, Therneau TM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL. Neighborhood income and individual education: effect on survival after myocardial infarction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(6): 663–669. 10.4065/83.6.663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong CM, Abnousi F, Asch SM, Heidenreich PA. Socioeconomic inequalities in quality of care and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome in the modern era of drug eluting stents. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001029. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanley GE, Morgan S, Reid RJ. Income-related inequity in initiation of evidence-based therapies among patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1329–1335. 10.1007/s11606-011-1799-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupre ME, George LK, Liu G, Peterson ED. The cumulative effect of unemployment on risks for acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(22):1731–1737. 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Méjean C, Droomers M, van der Schouw YT, et al. The contribution of diet and lifestyle to socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(6):5190–5195. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities— addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11. 10.1056/NEJMp1512532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holcomb J, Highfield L, Ferguson GM, Morgan RO. Association of Social Needs and Healthcare Utilization Among Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries in the Accountable Health Communities Model. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37: 3692–3699. 10.1007/s11606-022-07403-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Hospital Association. Results from 2019 Tax-Exempt Hospitals’ Schedule H Community Benefit Reports. 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/06/aha-2019-schedule-h-reporting.pdf

- 16.Koh HK, Piotrowski JJ, Kumanyika S, Fielding JE. Healthy people: a 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(6):551–557. 10.1177/1090198111428646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igland J, Vollset SE, Nygård OK, Sulo G, Ebbing M, Tell GS. Educational inequalities in acute myocardial infarction incidence in Norway: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(9): e106898. 10.1371/journal.pone.0106898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett S Socioeconomic inequalities in coronary heart disease and stroke mortality among Australian men, 1979-1993. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25(2):266–275. 10.1093/ije/25.2.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu K, Cedres LB, Stamler J, et al. Relationship of education to major risk factors and death from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular diseases and all causes, findings of three Chicago epidemiologic studies. Circulation. 1982;66(6):1308–1314. 10.1161/01.cir.66.6.1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assari S, Cobb S, Saqib M, Bazargan M. Diminished returns of educational attainment on heart disease among Black Americans. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2020;14:5–12. 10.2174/1874192402014010005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health Literacy Measurement Tools (Revised). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Published November 2019. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/research/tools/index.html

- 22.Health Literacy Tool Shed. Published August 2. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://healthliteracy.bu.edu/

- 23.Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, et al. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: a scientific statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138(2):e48–e74. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brach C, Keller D, Hernandez LM, et al. Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations. NAM Perspectives. Published online June 19, 2012. 10.31478/201206a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganguli I, Shi Z, Orav EJ, Rao A, Ray KN, Mehrotra A. Declining use of primary care among commercially insured adults in the United States, 2008-2016. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(4):240–247. 10.7326/M19-1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davey B, Sinha R, Lee JH, Gauthier M, Flores G. Social determinants of health and outcomes for children and adults with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Pediatr Res. 2021;89(2):275–294. 10.1038/s41390-020-01196-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charkhchi P, Fazeli Dehkordy S, Carlos RC. Housing and food insecurity, care access, and health status among the chronically ill: an analysis of the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):644–650. 10.1007/s11606-017-4255-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baggett TP, Liauw SS, Hwang SW. Cardiovascular disease and homelessness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2585–2597. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Byrne TH, Kane VR, Culhane DP. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S210–S211. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billioux K, Verlander A, Susan A, Dawn A. Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: the Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. 2017. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Standardized-Screening-for-Health-Related-Social-Needs-in-Clinical-Settings.pdf

- 31.Pendyal A, Rosenthal MS, Spatz ES, Cunningham A, Bliesener D, Keene DE. When you’re homeless, they look down on you:” a qualitative, community-based study of homeless individuals with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2021;50(1):80–85. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):397–405. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence, Baker TB, Piper ME, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S555–S570. 10.1080/14622200701673480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweitzer MM, Denlinger RL, Donny EC. Dependence and withdrawal-induced craving predict abstinence in an incentive-based model of smoking relapse. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):36–43. 10.1093/ntr/nts080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sims TH, Meurer JR, Sims M, Layde PM. Factors associated with physician interventions to address adolescent smoking. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(3):571–586. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00245.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–176. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lasser KE, Quintiliani LM, Truong V, et al. Effect of patient navigation and financial incentives on smoking cessation among primary care patients at an urban safety-net hospital: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1798–1807. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joseph RP, Ainsworth BE, Keller C, Dodgson JE. Barriers to Physical Activity Among African American Women: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Women Health. 2015;55(6):679–699. 10.1080/03630242.2015.1039184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNeill LH, Kreuter MW, Subramanian SV. Social environment and physical activity: a review of concepts and evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):1011–1022. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sylvia LG, Bernstein EE, Hubbard JL, Keating L, Anderson EJ. Practical guide to measuring physical activity. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(2):199–208. 10.1016/j.jand.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katzmarzyk PT, Martin CK, Newton RL Jr, et al. weight loss in underserved patients - a clusterrandomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):909–918. 10.1056/NEJMoa2007448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.AuYoung M, Linke SE, Pagoto S, et al. Integrating physical activity in primary care practice. Am J Med. 2016;129(10):1022–1029. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koorts H, Eakin E, Estabrooks P, Timperio A, Salmon J, Bauman A. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: the PRACTIS guide. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):51. 10.1186/s12966-018-0678-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubenfire M, Mollo L, Krishnan S, et al. The metabolic fitness program: lifestyle modification for the metabolic syndrome using the resources of cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2011;31(5):282–289. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e318220a7eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114696. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Motairek I, Lee EK, Janus S, et al. Historical neighborhood redlining and contemporary cardiometabolic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(2): 171–175. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mujahid MS, Gao X, Tabb LP, Morris C, Lewis TT. Historical redlining and cardiovascular health: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.2021;118(51):e2110986118. 10.1073/pnas.2110986118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warne D, Wescott S. Social Determinants of American Indian Nutritional Health. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Suppl 2):12–18. 10.1093/cdn/nzz054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hutchinson RN, Shin S. Systematic review of health disparities for cardiovascular diseases and associated factors among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. PLoS One. 2014;9(1): e80973. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]