Abstract

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has been an economic and health burden in most countries around the world. Reperfusion is a standard treatment for AMI as it can actively restore blood supply to the ischemic site. However, reperfusion itself can cause additional damage; a process known as cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Although several pharmacological interventions have been shown to reduce tissue damage during I/R injury, they usually have undesirable effects. Therefore, endogenous substances such as melatonin have become a field of active investigation. Melatonin is a hormone that is produced by the pineal gland, and it plays an important role in regulating many physiological functions in human body. Accumulated data from studies carried out in vitro, ex vivo, in vivo, and also from clinical studies have provided information regarding possible beneficial effects of melatonin on cardiac I/R such as attenuated cell death, and increased cell survival, leading to reduced infarct size and improved left-ventricular function. This review comprehensively discusses and summarizes those effects of melatonin on cardiac I/R. In addition, consistent and inconsistent reports regarding the effects of melatonin in cases of cardiac I/R together with gaps in surrounding knowledge such as the appropriate onset and duration of melatonin administration are presented and discussed. From this review, we hope to provide important information which could be used to warrant more clinical studies in the future to explore the clinical benefits of melatonin in AMI patients.

Keywords: Melatonin, Melatonin receptors, Ischemia/reperfusion, Left-ventricular function, Infarct size

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has been an economic and health burden in most countries around the world [1–5]. AMI is a situation where coronary arteries are blocked, resulting in a reduced blood and oxygen supply to the heart muscle [6]. Therefore, the restoration of the blood flow to the heart as soon as possible has been established as the treatment of choice to prevent further tissue injury, the process known as reperfusion therapy [7–9]. The reperfusion could be achieved by thrombolytic drugs, bypass surgery, and balloon angioplasty via percutaneous coronary intervention. Although reperfusion therapy is the most effective treatment, the process of reperfusion itself can cause additional damage such as increased cardiomyocyte death, increased infarct size, and microvascular dysfunction, together known as cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [7–9]. Despite the undesirable effects, reperfusion is the only method that can restore the blood flow into the ischemic myocardium [7–9]. For this reason, the therapeutic strategies that protect cardiac tissues from I/R injury may need to be emphasized rather than just focusing on the reperfusion therapy alone.

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an endogenous substance that is mainly produced by the pineal gland in the brain [10]. The use of specific molecular biology techniques revealed that serotonin-N-acetyltransferase (arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, AANAT) and acetylserotonin-O-methyltransferase (ASMT) are the key enzymes involved in the production of melatonin. Both AANAT and ASMT are found in the pineal gland and the other vital organs such as brain, eye, skin, stomach and heart [11], suggesting that melatonin can also be produced in these vital organs. In addition, melatonin is also found in various food such as meat, beer, red wine, and a very large number of fruits [11, 12].

One important role of melatonin is to regulate circadian rhythms and the sleep–wake pattern [10]. In addition, melatonin has been shown to exert protective effects against various types of cancer such as cancer of the breast, prostate, ovaries, and lung [13]. Moreover, melatonin has been shown to attenuate the complications of the age-related disease such as Alzheimer’s disease [14]. Several pieces of evidence have reported the potential benefit of melatonin in the treatment of heart diseases such as myocardial I/R injury, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and valvular heart disease [15]. These reports suggest that melatonin may exert benefits beyond its well-established roles in circadian regulation.

Cardiac I/R injury results in an excess amount of oxidative stress, inflammation, cardiac cell death, infarct size expansion, and impaired left-ventricular (LV) function [16–19]. Moreover, it has been shown that the levels of melatonin were reduced in patients with AMI, and patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention [20, 21]. These findings suggest that melatonin could play an important role in the prevention of cardiac I/R injury. In cases of cardiac I/R injury, the mechanism of melatonin has been involved both melatonin receptor-dependent and independent activity [15, 22–25]. As melatonin is a small-sized and amphiphilic molecule, it can easily pass through the cell membrane and exert its biological function intracellularly [24, 25]. As regards melatonin receptor-independent activity, melatonin directly activates several proteins, kinases, to exert beneficial effects during cardiac I/R [23]. For melatonin receptor-dependent activity, melatonin binds to its receptors which can be categorized into melatonin membrane receptors and melatonin nuclear receptors, thus activating downstream signaling [12], resulting in cardioprotection against I/R injury. Furthermore, evidence from in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo studies shows that melatonin can improve LV function, and reduce infarct size and cell death following cardiac I/R [26, 27].

In this review, the roles of melatonin in the heart during cardiac I/R from in vitro and in vivo studies have been summarized and discussed. Also, clinical reports regarding the use of melatonin as an intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and in cases of ischemic heart disease patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) have been presented. In addition, controversial reports are discussed, and potential future studies are suggested. Finally, we believe that this review will provide valuable information regarding the effects of melatonin in the cardiac I/R model, which could be used to encourage more clinical studies in the future to warrant its use in providing clinical benefits to AMI patients.

Role of melatonin in cardiac I/R: in vitro reports

Using cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats and H9C2 cells treated with melatonin prior subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R), it has been demonstrated that melatonin effectively increased cell viability after H/R via activating both JAK/STAT and Notch 1 pathways [28]. In this JAK/STAT pathway, melatonin increased p-JAK and p-STAT, resulting in ameliorated mitochondrial oxidative stress, increased levels of antioxidants, and reduced apoptosis [28]. Melatonin also activated Notch1/Hes1 proteins, followed by increasing the function of Akt as indicated by an increase in p-Akt, which is a survival protein, leading to reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis in H9C2 cells with H/R injury [26]. When JAK2 siRNA, and Notch1 siRNA were used, and the cells were treated with melatonin prior to H/R [26, 28], the results showed that the beneficial effects of melatonin against H/R injury were nullified in the absence of JAK2, and Notch1 [26, 28]. These findings confirm the vital role of the JAK/STAT and Notch 1 pathways.

In addition to JAK/STAT and Notch1, PKG1α, PI3K/Akt, ERK1/2, and STAT3 activation were also essential, to enable the melatonin to exert cardioprotective effects against I/R injury. When PKG1α siRNA, LY294002 (a PI3K/Akt inhibitor), U0126 (an ERK1/2 inhibitor), and AG490 (a STAT3 inhibitor) were used in H9C2 cells, melatonin did not protect the cells against H/R injury [29, 30]. Furthermore, melatonin also protected cardiac microcirculation endothelial cells (CMEC) against H/R injury via activating AMPKα, resulting in the inhibition of the mitochondrial fission-VDAC1-HK2-mPTP-mitophagy axis [31]. These data suggested that pre-treatment with melatonin increased cell survival via the activation of JAK/STAT, STAT3, Notch1/Hes1, PKG1α, PI3K/Akt, ERK1/2, and AMPKα, thus leading to a reduction in mitochondrial and cellular oxidative stress, mitochondrial fission, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis.

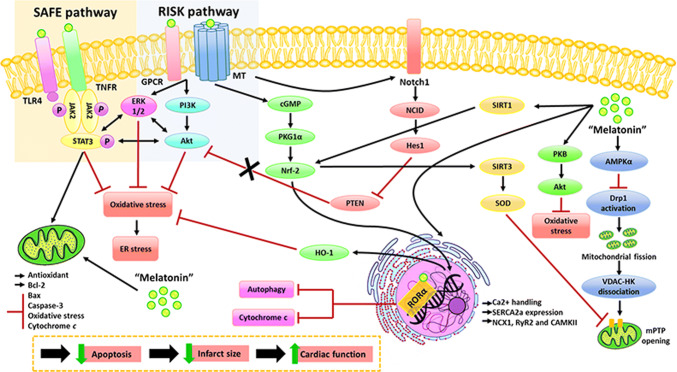

Despite the evidence that melatonin could help to reduce mitochondrial oxidative stress, enhance levels of mitochondrial antioxidants, and inhibit mitochondrial fission, the effects of melatonin on mitochondrial function and the underlying mechanisms have not been fully investigated. In addition, most in vitro studies treated the cells with melatonin prior to H/R injury. A single recent study showed that administration of melatonin onto the H9C2 cells during reoxygenation increased cell viability via reducing apoptosis and oxidative stress, and increasing antioxidant levels [32]. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the temporal effect of melatonin administration on the cells with H/R injury and the information regarding the effect of melatonin administration on mitochondrial function is still unknown. These crucial pieces of evidence will provide more mechanistic insights and clinically relevant information. The summarized effects of melatonin following H/R injury in in vitro studies are described in Table 1, and portrayed in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Role of melatonin in cardiac I/R: in vitro reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration | Major findings | Interpretation | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondria markers | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

Cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats H/R: 2 h/4 h |

2 µM/2 h prior to H/R |

↓Mito MDA ↑Mito SOD ↑SDH ↑COX |

↑Cell viability ↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Bax, Cyto cyt c ↑Bcl2 |

↑p-JAK2, p-STAT3 | Pre-treatment with melatonin increased cell survival and reduced cell death via activating JAK/STAT pathway, and decreasing mitochondrial oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes with H/R | [28] |

| Mel + JAK2 siRNA vs. Mel alone |

↑Mito MDA ↓Mito SOD ↓SDH ↓COX |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Bax, Cyto cyt c ↓Bcl2 |

↓p-JAK2, p-STAT3 | |||

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 2 h/4 h |

100 µM/4 h prior to H/R | – |

↑Cell viability ↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3, Bax ↑Bcl-2 |

↓Oxidative stress Survival proteins ↑Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt/Akt ↓PTEN |

Pre-treatment with melatonin increased cell survival and reduced cell death and oxidative stress via activation of Notch1/Hes1 signaling pathway | [26] |

| Mel + Hes1 siRNA vs. Mel alone | – |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3, Bax ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress Survival proteins ↓Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt/Akt ↑PTEN |

|||

| Mel + Notch siRNA vs. Mel alone | – |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↑Bax ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress Survival proteins ↓Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt/Akt ↑PTEN |

|||

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 2 h/4 h |

Mel + PKG1α siRNA vs. vehicle 10 µM/6 h prior to H/R |

– |

↔Cell viability ↔TUNEL+ cells ↔Caspase-3, Bax |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants Survival kinase ↓PKG1α, p-VASP/VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↑p-JNK, p-ERK, p-p38 MAPK |

The beneficial effects of melatonin in H/R were nullified in the absence of PKG1α | [29] |

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 2 h/4 h |

100 µM/8 h prior to H/R | – |

↑Cell viability ↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3, Bax ↑Bcl-2 |

↓Oxidative stress ↓ER stress Other ↑p-STAT3, p-Akt, p-GSK3β, p-ERK1/2 |

Pre-treatment with melatonin increased cell survival via inhibiting PERK-elF2α-ATF4-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress, reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis in H9C2 cells with H/R. These beneficial effects were nullified in the absence of PI3K, Akt, ERK1/2, and STAT3 | [30] |

|

Mel + LY294002 vs. Mel alone PI3K/Akt inhibitor (LY294002) µM |

– |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↑Bax ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress ↑ER stress Other ↓p-STAT3, p-Akt, p-GSK3β, p-ERK1/2 |

|||

|

Mel + U0125 vs. Mel alone ERK1/2 inhibitor (U0125) 5 µM |

– |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3, Bax ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress ↑ER stress Other ↓p-STAT3, p-Akt, p-GSK3β, p-ERK1/2 |

|||

|

Mel + AG490 vs. Mel alone STAT3 inhibitor (AG490) 40 µM |

– |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3, Bax ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress ↑ER stress Other ↓p-STAT3, p-Akt, p-GSK3β, p-ERK1/2 |

|||

|

Cardiac microcirculation endothelial cells (CMEC) isolated from hearts of C57BL/6 mice H/R: 30 min/120 min |

5 µM/12 h prior to H/R |

↓Mito were consumed by lysosome,PINK1, Parkin, MMP change, mPTP opening, fragmentation ↑HK2 ↑VDAC1 ↓Dimer & trimer VDAC1 ↓Mito pDrp1-616 ↑Mito pDrp1-637 |

↓TUNEL+ cells |

Autophagy markers ↓LCII/LCI |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced CMEC cell death by inhibiting mitochondrial fission-VDAC1-HK2-mPTP-mitophagy pathway in CMEC with H/R, these beneficial effects were nullified in the absence of AMPK. | [31] |

|

Cardiac microcirculation endothelial cells (CMEC) isolated from hearts of AMPK−/− mice H/R: 30 min/120 min |

↑Mito were consumed by lysosome, Mito PINK1, Parkin, MMP change, mPTP opening, fragmentation ↓Mito HK2 ↓VDAC1 ↑Dimer & trimer VDAC1 ↑Mito pDrp1-616 ↓Mito pDrp1-637 |

↑TUNEL+ cells |

Autophagy markers ↑LCII/LCI |

|||

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 1 h/4 h |

100 µM/at the onset of reoxygenation | ↓Mito-Bax |

↑Cell viability ↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Bax ↓Caspase-3 ↓C-caspase-3 ↑Bcl-2 ↓Cyto cyt c |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidant Survival proteins ↑SIRT1,3, NQO1 |

Treatment with melatonin at the onset of reoxygenation increased cell survival and reduced cell death via increasing antioxidants, reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis, and these beneficial effects were nullified in the absence of SIRT1 and SIRT3. | [32] |

| Mel + SIRT3 siRNA vs. Mel alone | ↑Mito-Bax |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Bax ↑Caspase-3 ↑C-caspase-3 ↓Bcl-2 ↑Cyto cyt c |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidant Survival proteins ↓SIRT1,3, NQO1 |

|||

| Mel + SIRT1 siRNA vs. Mel alone | – | – |

↓Antioxidant Survival proteins ↓SIRT1,3 |

|||

|

Mel + EX527 vs. Mel alone SIRT1 inhibitor (EX527) |

– | – |

↓Antioxidant Survival proteins ↓SIRT1,3 |

|||

Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Melatonin activated several survival protein kinases including RISK, SAFE, and Notch pathways [26, 30, 41]. RISK or reperfusion injury salvage kinase is activated by PI3K, followed by an activation of its downstream signaling including Akt and ERK [63]. Melatonin activated PI3K, lead to Akt and ERK phosphorylation [30]. Phosphorylated Akt and ERK inhibit mPTP opening, resulting in apoptosis reduction following cardiac I/R [30]. SAFE or the survivor activating factor enhancement pathway is activated by JAK phosphorylation [64]. Several studies showed that melatonin increased JAK phosphorylation, which subsequently phosphorylates STAT and form a STAT dimer. STAT dimers translocate to the nucleus, and promote antioxidant genes expression, leading to reduced oxidative stress in the heart with cardiac I/R injury [30, 41]. Moreover, STAT inhibited Bax translocation, enhanced Bcl2 expression, and suppressed mPTP opening, resulting in a reduced cell apoptosis [30, 41]. In addition, melatonin activates the Notch1/Hes1 pathway, thus increasing Akt function, leading to a decrease in pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bax) and enhanced the production of anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bcl-2) [26]. All of these findings demonstrated that melatonin effectively reduced apoptosis, leading to infarct size reduction, and finally resulting in improved LV function

Roles of melatonin in cardiac I/R: ex vivo reports

In reports using the ex vivo I/R model, the isolated perfused rat and mouse hearts were subjected to either global I/R or regional I/R. From investigations using the global I/R model, it has been shown that pre-treatment with melatonin effectively reduced the infarct size [33], and improved LV function [33, 34] following I/R. In addition, melatonin attenuated oxidative stress [35], reduced apoptosis [35], preserved cardiac mitochondrial function [36], and improved mitochondrial Ca2+ handling in the myocardium [33]. The opening of a mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) has been shown to be a key mediator of cell death in the heart subjected to I/R injury [37]. Pertinent to this, in cases of I/R injury calcium overload, adenine nucleotide depletion, and oxidative stress are key factors in the induction of the opening of mPTP [38], leading to the release of cytochrome c which subsequently activates the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis and causes infarct size expansion [33]. In isolated perfused rat hearts, melatonin given at 15 min prior to global I/R reduced Ca2+-induced mPTP opening and inhibited mitochondrial cytochrome c release into cytosol levels, resulting in reduced myocardium apoptosis and infarct size reduction, leading to improved LV function [33]. However, Dobsak and colleagues found that pre-treatment with 50 µM-melatonin at 3 min before I/R injury increased cardiac output via reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis; however, it did not affect heart rate in rats with global cardiac I/R [35]. This discrepancy could be due to the different timing of the administration of the melatonin. These data also suggested that to maximize the cardioprotective effects of melatonin it needs to be given at least 15 min before I/R in the ex vivo hearts with global I/R injury.

In the case of the regional I/R model in ex vivo hearts, left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) ligation was used to induce myocardial ischemia. The reports indicated that pre-treatment with melatonin exerted cardioprotective effects by reducing the infarct size [39–42], attenuating cellular apoptosis [28], decreasing oxidative stress [40] and inflammation [39], enhancing antioxidant enzymes [39], reducing the incidence of reperfusion arrhythmias [43], and improving LV function [28, 34, 39]. It has been shown that I/R injury impaired sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) function, resulting in impaired Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to intracellular Ca2+ overload, and damaging the contractility of the rat cardiomyocytes [42–44]. Melatonin did increase SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) protein levels, leading to increased SR Ca2+ levels, and decreased cytosolic Ca2+ levels [39, 40], thus improving calcium homeostasis during cardiac I/R injury [39, 40]. However, melatonin did not affect ryanodine receptors and sodium/calcium exchanger levels in this particular situation [40]. Recently, a report has described that treatment with melatonin at the onset of reperfusion reduced infarct size, but it did not improve LV function in I/R rats [45]. However, the mechanism responsible for this infarct size reduction has not been investigated.

The impact of melatonin on cardiac mitochondrial redox capacity has been reported. Yang and colleagues showed that melatonin improved mitochondrial redox potential by passing through the mitochondrial membrane leading to a decrease in mitochondrial oxidative stress and increased antioxidant enzymes in mitochondria [28]. However, the effects of melatonin on mitochondrial function and their dynamics in cardiac I/R injury have not been fully investigated. GPX1−/− mice were used to investigate the mechanism of the action of melatonin during cardiac I/R. In these mice, the activity of glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX) is less than 10% of the pertinent activity in wild-type mice, indicating low antioxidant levels, but those mice are physically healthy [46]. Treatment with melatonin in the GPX1−/− mice which had undergone I/R injury led to improved LV function and reduced cardiac tissue damage in these mice, suggesting that these beneficial effects of melatonin were independent of the GPX1 pathway [34].

Despite the accumulative data from ex vivo studies, there is still a large gap of information regarding the temporal effect of melatonin administration during cardiac I/R periods. In most studies, melatonin was given prior to cardiac I/R injury, a procedure which is not clinically relevant when the focus is on AMI patients. Information on the effects of melatonin given after ischemia and/or at the onset of reperfusion is essential to encourage further clinical investigation, and to give weight to the argument for the clinical usefulness of melatonin in AMI patients in the future. The summarized effects of melatonin following I/R injury in ex vivo studies are depicted in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Role of melatonin in cardiac I/R: ex vivo reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Mitochondria markers | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Global I/R: 30 min/45 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/3 min prior to I/R |

↔ CO ↔ HR |

– | – | - ↓TUNEL+ cells | ↓Oxidative stress | Although pre-treatment with melatonin reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis, it did not improve LV function during I/R | [35] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Global I/R: 30 min/15 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/15 min prior to I/R |

↑LVDP ↓LVEDP |

– |

↓Mito lipid peroxidation ↑Mito state3 respiration ↔ Mito state4 respiration ↔Mito respiratory control ratio ↑Mito complex I,III activity ↓Mito H2O2 ↑Mito cardiolipin ↓Peroxidized cardiolipin |

– | – | Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function by preserving cardiac mitochondrial function in rats with I/R | [36] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Global I/R: 30 min/15 and 120 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/15 min prior to I/R |

↑LVDP ↓LVEDP ↔HR |

↓%Infarct size |

↓Ca2+ induced mPTP opening ↑NAD+ ↑Mito cyt c |

– |

Cardiac tissue damage ↓LDH |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced infarct size in rats with I/R via improving mitochondria Ca2+ handling and reducing apoptosis | [33] |

|

Isolated perfused mouse heart Global I/R: 40 min/45 min |

150 µg/kg/30 min prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↑ ± dP/dt ↑LVDP ↔HR ↑LVDP x HR ↔Coronary flow ↓EDP |

– | – | – |

Cardiac tissue damage ↓LDH |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced cardiac tissue damage in mice with I/R, and these beneficial effects were independent of GPX1 pathway | [34] |

|

Isolated perfused heart of GPX1−/− mouse Global I/R: 40 min/45 min |

↑ ± dP/dt ↑LVDP ↔HR ↑LVDP × HR ↔Coronary flow |

– | – | – |

Cardiac tissue damage ↓LDH |

|||

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 10 min/15 min |

5, 10, 20, 50 µM/immediately prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↔HR ↔Coronary flow ↔Ischemic depolarization ↔APD90 ↓Incidence of reperfusion arrhythmias |

– | – | – | ↑Antioxidant | Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced the incidence of reperfusion arrhythmias in rats with I/R via enhancing the antioxidants. | [43] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 45 min/60 min |

5 µM added in perfusate/5 min prior to I/R |

↑ + dP/dt ↓LVDP ↓HR ↑Coronary flow |

↔Infarct size |

↑Mito redox potential (GSH/GSSH) ↑Mito SOD activity ↓Mito H2O2 ↓Mito MDA |

↓Bax ↑Bcl-2 |

Cardiac tissue damage ↓LDH |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function by reducing mitochondrial oxidative stress and decreasing apoptosis. However, it did not reduce infarct size in rats with I/R | [28] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 33 min/60 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R |

↔Aortic output ↔CO ↔Peak systolic pressure ↔HR ↔Total work |

↓Infarct size | – | – | – | Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size in rats with I/R, but it did not improve LV function | [54] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 35 min/120 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R | ↔CO, aortic output, HR, peak systolic pressure, coronary flow, total work | ↓Infarct size | – | – | – | Although pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size, it did not improve LV function in rats with I/R | [42] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

75 ng/L added in perfusate/15 min prior to I/R |

↔LVDP ↔HR ↔ Coronary flow |

↓Infarct size | – | – | – | Although pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size, it did not improve LV function in rats with I/R | [41] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

10 mg/kg/day 4 weeks prior to I/R i.p. injection |

↓Systolic pressure | ↓Infarct size | – | – |

↓LV remodeling ↓Oxidative stress ↓Inflammation ↑Ca2+handling Cardiac tissue damage ↓LDH |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced systolic pressure, infarct size, and cardiac remodeling in rats with I/R via reducing oxidative stress, and inflammation, and improving Ca2+ handling | [39] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

10 mg/kg/day 4 weeks prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

– | ↓Infarct size | – | – |

↓LV remodeling ↓Oxidative stress ↑Ca2+ handling Cardiac tissue damage ↓LDH Others ↔ %Hct |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size and cardiac hypertrophy in rats with I/R via reducing oxidative stress and improving Ca2+ handling | [40] |

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 33 min/60 min |

5 µM added in perfusate/at the onset of reperfusion |

↔ Time & level of maximum ischemia contraction ↔ HR ↔ Aortic pressure |

↓Infarct size | – | – | ↔LV remodelling | Although treatment with melatonin at the onset of reperfusion reduced infarct size in rats with I/R, it did not improve LV function | [45] |

Roles of melatonin in cardiac I/R: in vivo reports

Sprague–Dawley rats, Wistar rats, and mice underwent LAD ligation to induce I/R. All of these reports used melatonin at various doses and they were injected into the animals prior to I/R. Several studies reported that melatonin reduced infarct size [26, 27, 29–31, 34, 47, 48], and improved LV function [28–30, 32, 33]. It has been shown that melatonin activates the Notch1/Hes1 pathway, thus increasing Akt function, leading to a decrease in pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bax) and enhanced the production of anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bcl-2) [26]. In addition, melatonin ameliorated oxidative stress by activating the SIRT1/FoxO and PKG1α-Nrf2/HO-1 pathways and enhanced antioxidant enzymes [27, 29]. Although most in vivo studies reported cardioprotective effects, there is a report demonstrating that although melatonin reduced infarct size, and increased antioxidants, melatonin had no significant effect on hemodynamic parameters during I/R [47]. This inconsistent finding could be due to the timing of the melatonin administration. In this study, melatonin was given 10 min prior to I/R, while in other studies, given time varies from 15 min to 4 weeks prior to I/R. Therefore, these in vivo reports indicated that the time of melatonin administration before ischemia is crucial to preserve LV function in rodents subjected to 30-45 min ischemia followed by 20 min—72 h reperfusion.

Several specific inhibitors were used to confirm the potential signaling that is involved in the action of melatonin during cardiac I/R [26, 27, 29, 48]. KT5823, EX527, 3-TYP, DAPT, and ATR (which are a PKG inhibitor, SIRT1 inhibitor, SIRT3 inhibitor, Notch1 inhibitor, and ADP/ATP translocase inhibitor, respectively) were used to confirm their crucial roles in the action of melatonin. The results indicated that melatonin did not protect the heart from I/R injury in the absence of these signaling proteins. In addition, GPX1−/− mice were used to evaluate whether melatonin took action through GPX1 [34]. The results showed that melatonin reduced infarct size via reducing apoptosis and oxidative stress and the beneficial effects of melatonin were independent of GPX1 [34]. Data from these in vivo studies suggested that melatonin improved LV function, reduced infarct size, attenuated apoptosis, ameliorated oxidative stress, and enhanced antioxidant enzymes by activating the Notch1/Hes1 and SIRT1/FoxO signaling pathways as well as the PKG1α-Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

Mitochondria are known as cellular powerhouses that release the majority of energy in the cell [49]. In addition to energy production, mitochondria have other important roles, including calcium homeostasis and regulation of program cell death or apoptosis, and these processes require regulation of the mitochondrial dynamics [49, 50]. Although mitochondria are critical targets and at the root of tissue injury, particularly cardiac I/R injury [51], there is still a lack of information regarding the effects of melatonin on mitochondrial function in cardiac I/R injury. Importantly, even though many studies have shown the potential benefit of melatonin in protecting the heart against I/R injury, in most studies the melatonin treatment was given prior to ischemia. In the normal clinical setting, patients with AMI only arrive at the hospital when they have symptoms. Therefore, melatonin given after ischemia, or during reperfusion could provide more clinically relevant information. Recently, only one study has reported on treatment with melatonin during ischemia (10 min before reperfusion) which attenuated cardiac dysfunction and reduced infarct size in I/R mice via reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis, and enhancing antioxidant levels. They also suggested that the beneficial effects of melatonin are dependent upon the activation of SIRT3 [32]. However, the comparison of the efficacy of the temporal effects of the administration of melatonin during cardiac I/R in the in vivo model has never been investigated. The summarized effects of melatonin following I/R injury in in vivo studies are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Role of melatonin in cardiac I/R: in vivo reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

SD rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

10 mg/kg/Onset of I/R/i.v. injection | – | ↓Infarct size | – |

↓Porimin ↑NAD+ |

Pre-treatment with melatonin did not reduce infarct size in the absence of ADP/ATP translocase | [48] |

|

Mel + ATR vs. vehicle Melatonin 10 mg/kg/ Onset of I/R/i.v. injection ADP/ATP translocase inhibitor (ATR) 5 mg/kg/15 min prior to I/R/i.v. injection |

– | ↔Infarct size | – |

↓Porimin ↑NAD+ |

|||

|

Male Wistar rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

10 mg/kg 10 min prior to I/R i.v. injection |

↔BP ↔HR |

↓Infarct size | – |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidant |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size in rats with I/R via reducing oxidative stress and increasing antioxidant enzyme activity. However, it did not alter BP and HR | [47] |

|

Male New Zealand white rabbits Regional I/R: Coronary artery occlusion 30 min/3 h |

10 mg/kg 10 min prior to I/R/i.v. injection |

↔HR ↔BP ↔Regional myocardial blood flow |

↔Infarct size | – | – | Pre-treatment with melatonin did not affect LV function and infarct size in rabbits with I/R | [17] |

|

SD rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 20 min/20 min |

50 mg/kg 30 min prior to I/R/ i.p. injection |

– | – |

↓Fas ↑Bcl-2 |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidant ↑Inflammation Cardiac tissue damage ↓cTn-T |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced apoptosis, oxidative stress, and enhanced antioxidant activity in rats with I/R | [16] |

|

Wild type mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/3 h |

150 µg/kg/ 30 min prior to I/R/ i.p. injection |

– | ↓Infarct size | ↓%ISOL+ Myocyte | ↓Oxidative stress | Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size in rats with I/R via reducing apoptosis and oxidative stress and the beneficial effects of melatonin were independent of GPX1 pathway | [34] |

|

GPX1−/− mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/3 h |

– | ↓Infarct size | ↓%ISOL+ Myocyte | ↓Oxidative stress | |||

|

C57BL/6 mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

20 mg/kg/ 12 h prior to I/R/ i.p. injection |

↑LVEF ↓LVDd ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size | ↓TUNEL+ |

Cardiac tissue injury ↓LDH, TropT, CK-MB Other ↑eNOS, regular RBC morphology, VE-cadherin ↓Gr1 + neutrophil infiltration, albumin leakage |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced infarct size in rats with I/R. The beneficial effects of melatonin were nullified in the absence of AMPKα | [31] |

|

AMPKα−/− mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

↓LVEF ↑LVDd ↓LVFS |

↑Infarct size | ↑TUNEL+ |

Cardiac tissue injury ↑LDH, TropT, CK-MB Other ↓eNOS, Regular RBC morphology, VE-cadherin ↑Gr1 + neutrophil infiltration, Albumin leakage |

|||

|

C57BL/6 mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/4, 6 and 72 h |

300 µg/25 g/day/3 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↑LVEF ↑LVFS |

– |

↓Bax ↑Bcl2 ↓Caspase3 ↓TUNEL+ cells |

↓Oxidative stress ↓ER stress Other ↑p-STAT3/STAT, p-Akt/Akt, p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β, p-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function by reducing oxidative stress, apoptosis and inhibiting ER stress. However, these beneficial effects were nullified in the absence of PI3K/Akt, ERK1/2 and STAT3 | [30] |

|

Mel + LY294002 vs. Mel alone PI3K/Akt inhibitor (LY294002) 800 µg/25 g/day/3 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

– |

↑Bax ↓Bcl2 ↑Caspase3 ↑TUNEL+ cells |

↑Oxidative stress ↑ER stress Other ↓p-STAT3/STAT, p-Akt/Akt, p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β, p-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 |

|||

|

Mel + U0125 vs. Mel alone ERK1/2 inhibitor (U0125) 300 µg/25 g/day/3 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

– |

↑Bax ↓Bcl2 ↑Caspase3 ↑TUNEL+ cells |

↑Oxidative stress ↑ER stress Other ↓p-STAT3/STAT, p-Akt/Akt, p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β, p-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 |

|||

|

Mel + AG490 vs. Mel alone STAT3 inhibitor (AG490) 800 µg/25 g/day/3 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

– |

↑Bax ↓Bcl2 ↑Caspase3 ↑TUNEL+ cells |

↑Oxidative stress ↑ER stress Other ↓p-STAT3/STAT, p-Akt/Akt, p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β, p-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 |

|||

|

Male wistar rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/120 min |

Mel + L-NAME vs. L-NAME alone Melatonin 10 mg/kg/day/5 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection Non-specific NOS inhibitor (L-NAME) 40 mg/kg/day/15 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↓Systolic blood pressure ↓Diastolic blood pressure ↓Mean blood pressure |

– | – |

↓Oxidative stress ↓Inflammation |

Pre-treatment with melatonin decreased blood pressure in L-NAME induced hypertensive rats with I/R by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation | [18] |

|

SD rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/180 min |

10 mg/kg/day/5 days prior to I/R/PO And 10 mg/kg/10 min prior reperfusion/i.p. injection |

↑LVSP ↑ + dP/dtmax ↑ − dP/dtmax |

↓Infarct size |

↓%TUNEL+ cells ↓Bax ↓Caspase-3 ↑Bcl-2 |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidants Survival proteins ↑PKG1α, p-VASP/ VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↓p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced infarct size in rats with I/R via activating PKG1α pathway, reducing oxidative stress, and apoptosis, and increasing anti-oxidants. Moreover, the beneficial effects of melatonin were nullified in the absence of PKG1α | [29] |

|

Mel + KT5823 vs. Mel alone PKG inhibitor (KT5823) 1 mg/kg/20 min prior to reperfusion onset/i.p. injection |

↓LVSP ↓+ dP/dtmax ↓− dP/dtmax |

↑Infarct size |

↑%TUNEL+ cells ↑Bax ↑Caspase-3 ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants Survival proteins ↓PKG1α, p-VASP/ VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↑p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK |

|||

|

SD rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/6 h |

10 mg/kg/day/7 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection And 15 mg/kg/15 min before reperfusion/i.p. injection |

↑LVEF ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size |

↓TUNEL+ cells ↑Bcl-2 ↓Bax ↓Caspase-3 ↓C caspase-3 ↓AcFoxo1 |

Cardiac injury enzymes ↓CK, LDH Survival protein ↑SIRT1 ↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidants |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced infarct size in rats with I/R via the SIRT1 signaling pathway, reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis. Moreover, the beneficial effects of melatonin were nullified in the absence of SIRT1. | [27] |

|

Mel + EX527 vs. Mel alone SIRT1 inhibitor (EX527) 15 mg/kg/day/7 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

↑Infarct size |

↑TUNEL+ cells ↓Bcl-2 ↑Bax ↑Caspase-3 ↑C caspase-3 ↑AcFoxo1 |

Cardiac injury enzymes ↑CK, LDH Survival protein ↓SIRT1 ↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants |

|||

|

SD rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/4, 6 and 24 h |

10 mg/kg/day/4 weeks prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↔HR ↔Diastolic diameter - ↓Systolic diameter - ↔IVS, PW thickness - ↑LVEF - ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size | ↓TUNEL+ cells |

Survival proteins ↑Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced infarct size in rats with I/R via the Notch1 signaling pathway and reducing apoptosis. In addition, the beneficial effects of melatonin were nullified in the absence of Notch1. | [26] |

|

Mel + DAPT vs. Mel alone Notch inhibitor (DAPT) 50 mg/kg/10 min after the beginning of I/R/i.p. injection |

↔HR ↔Diastolic diameter ↑Systolic diameter ↔IVS, PW thickness ↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

↑Infarct size | ↑TUNEL+ cells |

Survival proteins ↓Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt |

|||

|

C57BL/6 mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/24 h |

20 mg/kg/10 min prior to reperfusion/i.p. injection |

↑LVEF ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size | ↓TUNEL+ cells |

Cardiac damage enzyme ↓LDH |

Treatment with melatonin during ischemia improved LV function and reduced infarct size via decreasing LDH and apoptosis. These beneficial effects were nullified in the absence of SIRT3 in I/R rats | [32] |

|

Mel + 3-TYP vs. Mel alone Selective SIRT3 inhibitor 3-(1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl) pyridine (3-TYP) 50 mg/kg/every 2 days for a total 3 doses prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

↑Infarct size | ↑TUNEL+ cells |

Cardiac damage enzyme ↑LDH |

|||

|

C57BL/6 mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/3 h |

20 mg/kg/ 10 min prior to reperfusion/i.p. injection |

– | – |

↓Bax ↑Bcl2 ↓Caspase3 |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidant Survival proteins ↑SIRT1,SIRT3 |

Treatment with melatonin during ischemia increased antioxidants, reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis via increased SIRT1 and 3. These beneficial effects were nullified in the absence of SIRT3 | |

|

Mel + 3-TYP vs. Mel alone Selective SIRT3 inhibitor 3-(1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl) pyridine (3-TYP) 50 mg/kg/ Every 2 days for a total of 3 doses prior to I/R/ i.p. injection |

– | – |

↑Bax ↓Bcl2 ↑Caspase3 |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidant Survival proteins ↔SIRT1 ↓SIRT3 |

|||

|

Female Danish Landrace pigs Regional I/R: Inflation of angioplasty balloon 45 min/4 h |

0.4 mg/ml/5 min prior to reperfusion/i.v. injection And 0.4 mg/ml/1 min prior to reperfusion/i.c. injection |

↔HR | ↔Infarct size | – |

↔Temp ↔hs-TnT |

Treatment with melatonin during ischemia did not reduce infarct size in pigs with I/R. | [19] |

Roles of melatonin receptors in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury

In mammals, three subtypes of melatonin membrane receptors have been identified. They are melatonin membrane receptor 1 (MT1), melatonin membrane receptor 2 (MT2), and melatonin membrane receptor 3 (MT3). These consist of seven transmembrane proteins, and they belong to the group of G-protein coupled receptors [52]. Both MT1 and MT2 are coupled to Gi/o-type proteins, and the MT1 is also coupled to a Gq-type protein receptor [52]. In humans, the MTNR1A gene encoding MT1 is located on chromosome 4q35.1 and the MTNR1B gene encoding MT2 on chromosome 11q21-q22 [53].

The cardioprotective effects of melatonin are mainly associated with melatonin membrane receptors. Results from in vitro studies have demonstrated that melatonin increased cell viability via the activation of several kinases including Notch1/Hes1 and PKG1α-Nrf2/HO-1, leading to reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis [26, 29]. Luzindole, which is a non-specific melatonin receptor antagonist, was used to confirm the cardioprotective effect of melatonin through activating its receptor [26, 29, 54]. 4-P-PDOT was also used to specifically antagonize MT2 [29]. These findings suggested that melatonin acts through its receptors to increase cell viability, and this effect was dependent on MT2. A previous ex vivo study has found that pre-treatment with melatonin and a melatonin receptor agonist (N-acetyltryptamine) had similar efficacy in reducing infarct size after I/R, these benefits being nullified when luzindole was administered [42]. In addition, administration of melatonin at the onset of reperfusion in an ex vivo heart reduced infarct size, and this beneficial effect was also blocked by luzindole [45]. Information from these reports suggested that administration of melatonin prior to I/R and given at the onset of reperfusion exerted cardioprotective effects in a melatonin membrane receptor dependent manner. However, the effects of melatonin, when given during the ischemic period, have never been investigated. Moreover, the efficacy of melatonin administration at different time points during cardiac I/R injury has not been elucidated. Moreover, future studies are needed to investigate whether the MT3 plays a role in cardioprotection.

The retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs) are nuclear hormone receptors and are also classified as nuclear melatonin receptors. There are three subtypes of RORs including RORα, RORβ, and RORγ [55]. In addition to their role in metabolic and immune regulation, RORs are well known circadian clock proteins involved in diurnal rhythm regulation [55, 56], and disturbance of the circadian rhythm leads to cardiovascular diseases including cardiac I/R injury. Expression of the proteins RORα and RORγ were found in the mouse heart model, but only RORα was downregulated in the I/R heart, whereas RORγ expression was not affected by cardiac I/R [55]. Since administration of melatonin in RORα deficient mice did not protect the heart from I/R injury [55], these findings suggested that RORα is an important melatonin nuclear receptor responsible for I/R injury. The summarized effects of melatonin on melatonin receptors are shown in Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7, and illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 4.

Role of melatonin membrane receptors in cardiac I/R: in vitro reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration | Major findings | Interpretation | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 2 h/4 h |

100 µM/4 h prior to H/R |

↑Cell viability ↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3 ↓Bax ↑Bcl-2 |

↓Oxidative stress Survival proteins ↑Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt/Akt ↓PTEN |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced cell death via activating the Notch1/Hes1 pathway, and decreasing cellular oxidative stress in H9C2 cells with H/R. These effects were dependent on melatonin membrane receptors | [26] |

|

Mel + Luz vs. Mel alone Melatonin receptor antagonist (Luzindole) 10 µM/ 4 h prior to H/R |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↑Bax ↓Bcl-2 |

↑Oxidative stress Survival proteins ↓Notch1, NICD, Hes1, p-Akt/Akt ↑PTEN |

|||

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 2 h/4 h |

10 µM/6 h prior to H/R |

↑Cell viability ↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3 ↓Bax |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidants Survival kinase ↑PKG1α, p-VASP/VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↓p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK |

Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced cell death via activating the PKG1α pathway, enhancing activity of antioxidant enzymes, and reducing cellular oxidative stress in H9C2 cells with H/R. These effects were dependent on melatonin receptor2 (MT2) | [29] |

|

Mel + Luz vs. Mel alone Melatonin receptor antagonist (Luzindole) 3 µM/6 h prior to H/R |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↑Bax |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants Survival kinase ↓PKG1α, p-VASP/VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↑p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK |

|||

|

H9C2 cells H/R: 2 h/4 h |

Mel + 4-P-PDOT vs. Mel alone MT2 receptor antagonist (4P-PDOT) 5 µM/6 h prior to H/R |

↓Cell viability ↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↑Bax |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants Survival kinase ↓PKG1α, p-VASP/VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↑p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK |

||

Table 5.

Role of melatonin membrane receptors in cardiac I/R: ex vivo reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 33 min/60 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R |

↔Aortic output ↔CO ↔Peak systolic pressure ↔HR ↔Total work |

↓Infarct size | – | Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size via activating NOS and guanylate cyclase in rats with I/R, and these beneficial effects were dependent on melatonin receptor activation. However, pre-treatment with melatonin did not improve LV function in rats with I/R | [54] |

|

Mel + Luz vs. Mel alone Melatonin receptor antagonist (Luzindole) 5 µM/15 min prior to I/R |

↓Aortic output ↓CO ↔Peak systolic pressure ↔HR ↓Total work |

↑Infarct size | – | |||

|

Mel + L-NAME vs. Mel alone Non-specific NOS inhibitor (L-NAME) 100 µM/15 min prior to I/R |

↓Aortic output ↓CO ↔Peak systolic pressure ↔HR ↓Total work |

↑Infarct size | – | |||

|

Mel + BIM vs. Mel alone Protein kinase C inhibitor (BIM) 5 µM/15 min prior to I/R |

↔Aortic output ↔CO ↔Peak systolic pressure ↔HR ↔Total work |

↔Infarct size | – | |||

|

Mel + ODQ vs. Mel alone Guanylyl cyclase inhibitor (ODQ) 20 µM/15 min prior to I/R |

↓Aortic output ↓CO ↔Peak systolic pressure ↔HR ↓Total work |

↑Infarct size | – | |||

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 35 min/120 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R | – | ↓Infarct size | – | Pre-treatment with melatonin reduced infarct size in rats with I/R, and this beneficial effect was dependent on melatonin membrane receptors | [42] |

|

Mel + Luz vs. Mel alone Melatonin receptor antagonist (Luzindole) 5 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R |

– | ↑Infarct size | – | |||

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 35 min/120 min |

50 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R | – | ↓Infarct size | – | Pre-treatment with melatonin and melatonin receptor agonists shared similar efficacy in reducing infarct size in rats with I/R | [42] |

|

Mel + NAT vs. Mel alone Melatonin receptor agonist (NAT) 5 µM added in perfusate/10 min prior to I/R |

– | ↔ Infarct size | – | |||

|

Isolated perfused rat heart Regional I/R: LAD ligation 33 min/60 min |

5 µM added in perfusate/at the onset of reperfusion |

↔ Time of maximum ischemia contraction ↔ Level of maximum ischemia contraction ↔ HR ↔ Aortic pressure |

↓Infarct size | ↔LV remodeling | Treatment with melatonin at the onset of reperfusion reduced infarct size in rats with I/R. This beneficial effect was dependent on melatonin receptors. However, treatment with melatonin at the onset of reperfusion did not improve LV function in rats with I/R | [45] |

|

Mel + Luz vs. Control Melatonin receptor antagonist (Luzindole) 5 µM added in perfusate/ At the onset of reperfusion |

↔ Time of maximum ischemia contraction ↔ Level of maximum ischemia contraction ↔ HR ↔ Aortic pressure |

↑Infarct size | ↔LV remodeling | |||

Table 6.

Role of melatonin membrane receptors in cardiac I/R: in vivo reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

SD rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/6 h |

10 mg/kg/day/7 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection And 15 mg/kg/15 min before reperfusion/i.p. injection |

↑LVEF ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size |

↓TUNEL+ cells ↑Bcl-2 ↓Bax ↓Caspase-3 ↓C caspase-3 ↓Ac-Foxo1 |

Cardiac injury enzymes ↓CK, LDH Survival protein ↑SIRT1 ↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidants |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function and reduced infarct size in I/R rats via reducing oxidative stress, apoptosis and increasing antioxidant enzymes. These effects were dependent on melatonin membrane receptor | [27] |

|

Mel + Luz vs. Mel alone Melatonin receptor antagonist (Luzindole) 1 mg/kg/day/7 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection And 2 mg/kg/20 min prior to reperfusion/i.p. injection |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

↑Infarct size |

↑TUNEL+ cells ↓Bcl-2 ↑Bax ↑Caspase-3 ↑C caspase-3 ↑Ac-Foxo1 |

Cardiac injury enzymes ↑CK, LDH Survival protein ↓SIRT1 ↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants |

|||

Table 7.

Role of melatonin nuclear receptors in cardiac I/R: in vivo reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

Wild type mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/30 min |

150 µg/kg/30 min prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↑LVEF ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size |

↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3 ↓Caspase-9 ↓Caspase-12 ↓Cyt c levels |

Autophagy ↓CHOP, LC3-II/LC3-I, p62 ↓Oxidative stress |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function, and reduced infarct size via decreasing oxidative stress and apoptosis in mice with I/R. These beneficial effects were dependent on melatonin nuclear receptors | [55] |

|

RORα-deficient staggerer mice Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/30 min |

↓LVEF ↓LVFS |

↑Infarct size |

↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↑Caspase-9 ↑Caspase-12 ↑Cyt c levels |

Autophagy ↑CHOP, LC3-II/LC3-I, p62 ↓Oxidative stress |

|||

Effects of melatonin administration on cardiac I/R: clinical reports

At this time there are three clinical studies available describing the effects of melatonin administration on cardiac I/R (Table 8). In the first study published in 2016, melatonin (10 and 20 mg/day) was given orally in 45 patients with ischemic heart disease prior to undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery. The results indicated that melatonin attenuated myocardial I/R injury by improving LV function via reducing oxidative stress, and inflammation, and ameliorating cardiac apoptosis [57]. In 2017, another clinical study was published, and the results showed that intravenous administration of 0.1 mg/ml melatonin and intracoronary administration of 0.1 mg/ml at the onset of reperfusion did not improve LV function, or reduce infarct size and improve clinical outcomes in 48 ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients [58]. However, a recent report published in 2017 by Dominguez–Rodriguez and colleagues demonstrated that the intravenous administration of 51.7 µmol melatonin at 60 min prior to reperfusion and use of an intracoronary bolus of 8.6 µmol melatonin at the onset of reperfusion in 146 patients with STEMI led to a reduction in infarct size; however, it did not improve the LV function [59].

Table 8.

Effect of melatonin on cardiac I/R: clinical reports

| Study models (n) | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients (48) | 0.1 mg/ml of which 10 ml was administered/immediately after pPCI/intracoronary and i.v. injection |

↔ LVEDV ↔ LVESV ↔ LVEF |

↔Infarct size | – |

↔ Inflammation ↔ Oxidative stress Cardiac tissue damage ↔ hs-TnT, CK-MB Other ↔ Fatal clinical events |

Melatonin did not improve LV function and clinical outcomes in patients with STEMI | [58] |

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients (146) |

51.7 µmol/60 min prior to pPCI/i.v. injection And 8.6 µmol/at the onset of reperfusion/intracoronary bolus |

↔ LVEDV ↔ LVESV ↔ Total LV mass |

↓Infarct size in patient with symptom 136 ± 23 min after onset ↔ Infarct size in patient with symptom 196 ± 19 min and 249 ± 41 min after onset |

– | – | Early melatonin administration reduced infarct size in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients | [59] |

| Ischemic heart disease patients undergoing elective CABG (45) | 10 and 20 mg/day/5 days prior to surgery)/PO |

↑LVEF ↓HR |

– | Plasma caspase-3 |

Cardiac tissue damage ↓cTn-I ↓Inflammation |

Melatonin attenuated I/R injury in ischemic heart disease patients undergoing CABG via reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis | [57] |

These arguably inconclusive results might be due to the differences in time of melatonin administration, the severity of AMI, and the age of patients in each study. Early melatonin administration may result in greater cardioprotective effects compared to delayed administration [59]. Dominguez-Rodriguez et al. found that melatonin given approximately 2.5 h after the onset of chest pain could reduce the infarct size by approximately 40% as measured by cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) [59]. Furthermore, the routes of melatonin administration also affect the outcomes because the pharmacokinetics of orally administered melatonin and its metabolites may confer more advantages than other routes [58]. The summary of studies using different time points of melatonin administration in cardiac I/R models is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Summary of referenced studies that investigated the effects of melatonin given before ischemia, during ischemia, and at reperfusion in cardiac I/R models

In addition to the protective effects of melatonin against cardiac I/R, a recent study from Sirma Geyik and colleagues found that patients undergoing elective CABG in the morning (8:00 a.m.) had less deterioration in neurocognitive function than those who underwent their operation in the afternoon (1:00 p.m.) [60]. This benefit was associated with the higher level of melatonin in the morning than in the afternoon, therefore melatonin might reduce damage from I/R injury and preserved neurocognitive function by anti-oxidant, anti-inflammation, anti-amyloid, and vasodilator effects [60].

Effects of melatonin administration in diabetic model with cardiac I/R

There are three studies that reported the effects of melatonin in diabetic rats with cardiac I/R injury. It has been shown that pre-treatment with melatonin at 10 mg/kg/day for 5 days effectively reduced the infarct size and improved the LV function by activating cGMP/PKG signaling pathway [29]. AMPK/SIRT3 pathway, and/SIRT1 pathway [61, 62], leading to improved cardiac mitochondrial redox system, decreased cellular oxidative stress, enhanced cellular antioxidant enzymes, and reduced cell apoptosis in diabetic rat models [29, 61, 62]. These data indicated that melatonin also have potential cardioprotective effects against cardiac I/R in the rat model of diabetes. However, melatonin was given only prior to cardiac I/R. The effects of melatonin administration at various points in time during cardiac I/R such as during an ischemic period and upon the onset of reperfusion have not been investigated. The summarized effects of melatonin administration in diabetic model with cardiac I/R are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Role of melatonin in diabetic model with cardiac I/R: in vivo reports

| Study models | Dose/time of administration/route | Major findings | Interpretation | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV function/hemodynamic parameters | Infarct size | Cell death markers | Other biomarkers | ||||

|

STZ induced T1DM rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/3, 6 h |

10 mg/kg/5 days prior to I/R/i.p. injection |

↑LVSP ↑ + dP/dtmax ↑ − dP/dtmax |

↓Infarct size |

↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3 ↑Bcl2 ↓Bax |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidants Survival kinase ↑PKG1α, p-VASP/VASP, cGMP, HO-1 ↓p-JNK/JNK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK ↑p-ERK/ERK |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function, and reduced infarct size via decreasing oxidative stress and apoptosis, and increasing antioxidants in T1DM rats with I/R. The beneficial effects of melatonin were abolished in the absence of PKG | [29] |

|

Mel + KT5823 vs. Mel alone PKG inhibitor 1 mg/kg/ 20 min prior to I/R/ i.v. injection |

↓LVSP ↓+ dP/dtmax ↓− dP/dtmax |

↑Infarct size |

↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↓Bcl2 ↑Bax |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants Survival kinase ↓PKG1α, p-VASP/VASP, HO-1, p-ERK/ERK ↑p-JNK/JNK, p-p38 MAPK/p38 MAPK ↔ cGMP |

|||

|

STZ induced T1DM rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/3 h |

10 mg/kg/ 5 days prior to I/R/PO |

↑LVSP ↑ + dP/dtmax ↑ − dP/dtmax |

↓Infarct size |

↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3 ↑Bcl2 ↓Bax |

↑Mitochondrial parameters ↑Mito SOD, ATP ↓Mito MDA, H2O2 ↑Mito Biogenesis Survival kinase ↑p-AMPK/AMPK, SIRT3 ↑Antioxidants ↑SOD2 |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function, and reduced infarct size via improving mitochondrial redox system, and increasing survival proteins and antioxidants in T1DM rats with I/R. The beneficial effects of melatonin were abolished in the absence of AMPK. | [61] |

|

Mel + compound c vs. Mel alone AMPK inhibitor 0.25 mg/kg/15 min prior to reperfusion/i.v. injection |

↓LVSP ↓+ dP/dtmax ↓− dP/dtmax |

↑Infarct size |

↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↓Bcl2 ↑Bax |

↓Mitochondrial parameters ↓Mito SOD, ATP ↑Mito MDA, H2O2 ↓Mito Biogenesis Survival kinase ↓p-AMPK/AMPK, SIRT3 ↓Antioxidants ↓SOD2 |

|||

|

HFD + STZ induced T2DM rats Regional I/R: LAD ligation 30 min/4, 6, 72 h |

10 mg/kg/ 1 week prior to I/R/PO |

↑LVEF ↑LVFS |

↓Infarct size |

↓TUNEL+ cells ↓Caspase-3 ↑Bcl2 ↓Bax |

↓Oxidative stress ↑Antioxidants ↓ER stress ↓p-PERK/PERK, p-ElF2α/ElF2α, ATF4, CHOP |

Pre-treatment with melatonin improved LV function, and reduced infarct size via reducing cell apoptosis, ER stress, and increasing antioxidants in T2DM rats with I/R. However, the beneficial effects of melatonin were abolished in the absence of SIRT1 | [62] |

|

Mel + Sirtinoid vs. Mel alone SIRT1 inhibitor 15 mg/kg/15 min prior to reperfusion/i.p. injection |

-↓LVEF -↓LVFS |

-↑Infarct size |

↑TUNEL+ cells ↑Caspase-3 ↓Bcl2 ↑Bax |

↑Oxidative stress ↓Antioxidants ↑ER stress ↑p-PERK/PERK, p-ElF2α/ElF2α, ATF4, CHOP |

|||

Conclusion

Melatonin plays an important role in normal physiological functions in our body. Evidence from in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo studies demonstrates the potential cardioprotective effects of melatonin against cardiac I/R injury, the main advantages being reduction the infarct size, and a decrease in apoptotic cell death and oxidative stress, resulting in improved LV function. However, the detailed mechanisms of the cardioprotective effects of melatonin including mitochondrial function are still unclear. In addition, there are many gaps in the knowledge around this area which still need to be filled including the effects of melatonin given at different time points during the process of cardiac I/R. Future studies are needed to fill the gaps in this information as enhanced knowledge about this chemical will confer great benefits on AMI patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Thailand Research Fund grants: RTA 6080003 (SCC), TRG6080005 (NA); the Royal Golden Jubilee Program (KS and NC); the NSTDA Research Chair grant from the National Science and Technology Development Agency Thailand (NC), and the Chiang Mai University Center of Excellence Award (NC).

Author contributions

SCC and NC: Conception; KS, NA, SCC, and NC: drafting of the manuscript, revision of the manuscript, and final approval.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zhao Z, Winget M. Economic burden of illness of acute coronary syndromes: medical and productivity costs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seo H, et al. Recent trends in economic burden of acute myocardial infarction in South Korea. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen TP, Nguyen T, Postma M. Economic burden of acute myocardial infarction in Vietnam. Value Health. 2015;18:A389. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacey L, Tabberer M. Economic burden of post-acute myocardial infarction heart failure in the United Kingdom. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarride JE, Lim M, DesMeules M, Luo W, Burke N, O’Reilly D, Bowen J, Goeree R. A review of the cost of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:e195–e202. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70098-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambrose JA, Singh M. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease leading to acute coronary syndromes. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7:8. doi: 10.12703/P7-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribichini F, Wijns W. Acute myocardial infarction: reperfusion treatment. Heart. 2002;88:298–305. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy K, Khaliq A, Henning RJ. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction. World J Cardiol. 2015;7:243–276. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i5.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rentrop KP, Feit F. Reperfusion therapy for acute myocardial infarction: concepts and controversies from inception to acceptance. Am Heart J. 2015;170:971–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Maestroni GJ, Zisapel N, Cardinali DP. Physiological effects of melatonin: role of melatonin receptors and signal transduction pathways. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;85:335–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acuna-Castroviejo D, et al. Extrapineal melatonin: sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2997–3025. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Favero G, Franceschetti L, Buffoli B, Moghadasian MH, Reiter RJ, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Melatonin: protection against age-related cardiac pathology. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;35:336–349. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Li S, Zhou Y, Meng X, Zhang JJ, Xu DP, Li HB. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39896–39921. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karasek M. Melatonin, human aging, and age-related diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1723–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun H, Gusdon AM, Qu S. Effects of melatonin on cardiovascular diseases: progress in the past year. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27:408–413. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceyran H, Narin F, Narin N, Akgun H, Ceyran AB, Ozturk F, Akcali Y. The effect of high dose melatonin on cardiac ischemia- reperfusion Injury. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:735–741. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.5.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dave RH, Hale SL, Kloner RA. The effect of melatonin on hemodynamics, blood flow, and myocardial infarct size in a rabbit model of ischemia–reperfusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 1998;3:153–160. doi: 10.1177/107424849800300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahna E, Deniz E, Bay-Karabulut A, Burma O. Melatonin protects myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury in hypertensive rats: role of myeloperoxidase activity. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30:673–681. doi: 10.1080/10641960802251966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekelof SV, et al. Effects of intracoronary melatonin on ischemia-reperfusion injury in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2016;31:88–95. doi: 10.1007/s00380-014-0589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Garcia MJ, Sanchez J, Marrero F, de Armas-Trujillo D. Decreased nocturnal melatonin levels during acute myocardial infarction. J Pineal Res. 2002;33:248–252. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2002.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Arroyo-Ucar E, Reiter RJ. Decreased level of melatonin in serum predicts left ventricular remodelling after acute myocardial infarction. J Pineal Res. 2012;53:319–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tengattini S, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Terron MP, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Cardiovascular diseases: protective effects of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, et al. A review of melatonin as a suitable antioxidant against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and clinical heart diseases. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:357–366. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emet M, Ozcan H, Ozel L, Yayla M, Halici Z, Hacimuftuoglu A. A review of melatonin, its receptors and drugs. Eurasian J Med. 2016;48:135–141. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2015.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Galano A. Melatonin: exceeding expectations. Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29:325–333. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00011.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu L, et al. Membrane receptor-dependent Notch1/Hes1 activation by melatonin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:420–433. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu L, et al. Melatonin receptor-mediated protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: role of SIRT1. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:228–238. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, et al. JAK2/STAT3 activation by melatonin attenuates the mitochondrial oxidative damage induced by myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Pineal Res. 2013;55:275–286. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu LM, et al. Melatonin protects diabetic heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury, role of membrane receptor-dependent cGMP-PKG activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1864:563–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu L, et al. Melatonin reduces PERK-eIF2alpha-ATF4-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of RISK and SAFE pathways interaction. Apoptosis. 2016;21:809–824. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H, et al. Melatonin protects cardiac microvasculature against ischemia/reperfusion injury via suppression of mitochondrial fission-VDAC1-HK2-mPTP-mitophagy axis. J Pineal Res. 2017;63:e12413. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhai M, et al. Melatonin ameliorates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury through SIRT3-dependent regulation of oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Pineal Res. 2017;63:e12419. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petrosillo G, Colantuono G, Moro N, Ruggiero FM, Tiravanti E, Di Venosa N, Fiore T, Paradies G. Melatonin protects against heart ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1487–H1493. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00163.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Z, Chua CC, Gao J, Chua KW, Ho YS, Hamdy RC, Chua BH. Prevention of ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiac apoptosis and injury by melatonin is independent of glutathione peroxdiase 1. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobsak P, et al. Melatonin protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury and inhibits apoptosis in isolated working rat heart. Pathophysiology. 2003;9:179–187. doi: 10.1016/S0928-4680(02)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrosillo G, et al. Protective effect of melatonin against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with cardiac ischemia- reperfusion: role of cardiolipin. FASEB J. 2006;20:269–276. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4692com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong R, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore and calcium handling. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;810:235–242. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morciano G, Giorgi C, Bonora M, Punzetti S, Pavasini R, Wieckowski MR, Campo G, Pinton P. Molecular identity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;78:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeung HM, Hung MW, Lau CF, Fung ML. Cardioprotective effects of melatonin against myocardial injuries induced by chronic intermittent hypoxia in rats. J Pineal Res. 2015;58:12–25. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeung HM, Hung MW, Fung ML. Melatonin ameliorates calcium homeostasis in myocardial and ischemia-reperfusion injury in chronically hypoxic rats. J Pineal Res. 2008;45:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nduhirabandi F, Lamont K, Albertyn Z, Opie LH, Lecour S. Role of toll-like receptor 4 in melatonin-induced cardioprotection. J Pineal Res. 2016;60:39–47. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lochner A, Genade S, Davids A, Ytrehus K, Moolman JA. Short- and long-term effects of melatonin on myocardial post-ischemic recovery. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diez ER, Prados LV, Carrion A, Ponce ZA, Miatello RM. A novel electrophysiologic effect of melatonin on ischemia/reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in isolated rat hearts. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osada M, Netticadan T, Tamura K, Dhalla NS. Modification of ischemia-reperfusion-induced changes in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by preconditioning. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H2025–H2034. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.6.H2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroethoff M, Behmenburg F, Spittler K, Raupach A, Heinen A, Hollmann MW, Huhn R, Mathes A. Activation of melatonin receptors by Ramelteon induces cardioprotection by postconditioning in the rat heart. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:2112–2115. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Bronson RT, Cao J, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk CD. Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16644–16651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sahna E, Parlakpinar H, Turkoz Y, Acet A. Protective effects of melatonin on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion induced infarct size and oxidative changes. Physiol Res. 2005;54:491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu LF, Qian ZH, Qin Q, Shi M, Zhang H, Tao XM, Zhu WP. Effect of melatonin on oncosis of myocardial cells in the myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rat and the role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:7481–7489. doi: 10.4238/2015.July.3.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shpilka T, Haynes CM. The mitochondrial UPR: mechanisms, physiological functions and implications in ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:109–120. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maneechote C, Palee S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Roles of mitochondrial dynamics modulators in cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:2643–2653. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial dysfunction and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion: implications for novel therapies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:535–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slominski RM, Reiter RJ, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Ostrom RS, Slominski AT. Melatonin membrane receptors in peripheral tissues: distribution and functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;351:152–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jockers R, Delagrange P, Dubocovich ML, Markus RP, Renault N, Tosini G, Cecon E, Zlotos DP. Update on melatonin receptors: IUPHAR review 20. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:2702–2725. doi: 10.1111/bph.13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Genade S, Genis A, Ytrehus K, Huisamen B, Lochner A. Melatonin receptor-mediated protection against myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury: role of its anti-adrenergic actions. J Pineal Res. 2008;45:449–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He B, Zhao Y, Xu L, Gao L, Su Y, Lin N, Pu J. The nuclear melatonin receptor RORalpha is a novel endogenous defender against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Pineal Res. 2016;60:313–326. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jetten AM. Retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs): critical roles in development, immunity, circadian rhythm, and cellular metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dwaich KH, Al-Amran FG, Al-Sheibani BI, Al-Aubaidy HA. Melatonin effects on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: impact on the outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ekeloef S, et al. Effect of intracoronary and intravenous melatonin on myocardial salvage index in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2017;10:470–479. doi: 10.1007/s12265-017-9768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, et al. Usefulness of early treatment with melatonin to reduce infarct size in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction receiving percutaneous coronary intervention (from the melatonin adjunct in the acute myocardial infarction treated with angioplasty trial) Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geyik S, Yiğiter R, Akçalı A, Deniz H, Geyik AM, Elçi MA, Hafız E. The effect of circadian melatonin levels on inflammation and neurocognitive functions following coronary bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;21:466–473. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.14-00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu L, et al. Melatonin ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in type 1 diabetic rats by preserving mitochondrial function: role of AMPK-PGC-1alpha-SIRT3 signaling. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41337. doi: 10.1038/srep41337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu L, et al. Reduced silent information regulator 1 signaling exacerbates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in type 2 diabetic rats and the protective effect of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:376–390. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rossello X, Yellon DM. The RISK pathway and beyond. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;113:2. doi: 10.1007/s00395-017-0662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hadebe N, Cour M, Lecour S. The SAFE pathway for cardioprotection: is this a promising target? Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;113:9. doi: 10.1007/s00395-018-0670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]