Abstract

The gut microbiota is essential to health and has recently become a target for live bacterial cell biotherapies for various chronic diseases including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity and neurodegenerative disease. Probiotic biotherapies are known to create a healthy gut environment by balancing bacterial populations and promoting their favorable metabolic action. The microbiota and its respective metabolites communicate to the host through a series of biochemical and functional links thereby affecting host homeostasis and health. In particular, the gastrointestinal tract communicates with the central nervous system through the gut–brain axis to support neuronal development and maintenance while gut dysbiosis manifests in neurological disease. There are three basic mechanisms that mediate the communication between the gut and the brain: direct neuronal communication, endocrine signaling mediators and the immune system. Together, these systems create a highly integrated molecular communication network that link systemic imbalances with the development of neurodegeneration including insulin regulation, fat metabolism, oxidative markers and immune signaling. Age is a common factor in the development of neurodegenerative disease and probiotics prevent many harmful effects of aging such as decreased neurotransmitter levels, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis—all factors that are proven aggravators of neurodegenerative disease. Indeed patients with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases have a high rate of gastrointestinal comorbidities and it has be proposed by some the management of the gut microbiota may prevent or alleviate the symptoms of these chronic diseases.

Keywords: Gut microbiota, Probiotics, Gut-brain-axis, Neurodegeneration, Oxidative stress, Short-chain fatty acids

The gut microbiota and the gut–brain axis

The gut microbiota is composed of a vast plethora of bacterial species residing within the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The importance of the gut microbiota to human health has recently been recognized due to the bacterial community’s bilateral connectivity to the rest of the body, and notably, the brain. The GIT and the central nervous system (CNS) are intricately connected through a network of signaling pathways collectively known as the gut–brain axis. The gut–brain axis is a dynamic bidirectional neuroendocrine system consisting of direct neurological connections, endocrine signals and immunological factors [1–3]. The gut microbiota conveys information contained in the ingested components passing through the GIT (i.e., vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, etc.) with the CNS via the aforementioned routes to elicit a systemic response reflecting nutritional and energy states. When the relative microbial populations fall out of balance (dysbiosis), the messages sent to the brain propagate unhealthy signals manifesting in low-grade inflammation, increased oxidative stress, unbalanced energy homeostasis and a general increase in cellular degeneration [4]. Many recent studies suggest that microbial dysbiosis contributes to the pathology of multiple neurological diseases including depression, anxiety and neurodegeneration [5, 6]. This article describes several possible mechanisms of gut–brain axis communication and how manipulation of the gut microbiota with probiotics can influence neurodegenerative diseases by improving inflammatory markers, modulating neurological signaling and reducing the levels of oxidative stress: the main common features of idiopathic neurodegeneration.

The gut microbiota

The gut microbiota consists of a diverse community of bacterial species in the GIT existing symbiotically with the human host. The majority of the microbiota belongs to the phyla Firmicutes (~51%) including the Clostridium coccoides and Clostridium leptum groups and the well-known Lactobacillus genera and the phyla Bacteroidetes (~48%) including the well-known genera Bacteroides and Prevotella [7]. The remaining 1% is constituted by other less populous phyla, including Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria (including the Bifidobacteria genera), Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, Verrucomicrobia and Lentisphaerae [8]. Modern sequencing technology has identified at least 1000 species and more than 7000 strains of bacteria composing the 1013–1014 microorganisms of the microbiota [9]. There are high inter-individual variations in the gut microbial populations; however, the overall functionality is conserved, suggesting that a core gut microbiota is required to maintain a basic set of physiological functions [10]. The gut microbiota may be considered an organ onto itself, being responsible for a variety of physiological activities including host metabolism, neurological development, energy homeostasis, immune regulation, vitamin synthesis and digestion [11].

The gut–brain axis

The gut–brain axis is a dynamic bidirectional neuroendocrine system describing the connections between the GIT and the nervous system. There are many common regulatory factors between the enteric nervous system (ENS) and the CNS [12]. Many of the hormones and metabolites secreted by the microbiota and intestinal enterochromaffin (EC) cells intersect with biochemical pathways that influence CNS processes creating a means of direct communication between the external environment in contact with the gut microbiota and the brain, which is isolated from the environment by the blood–brain barrier (BBB).

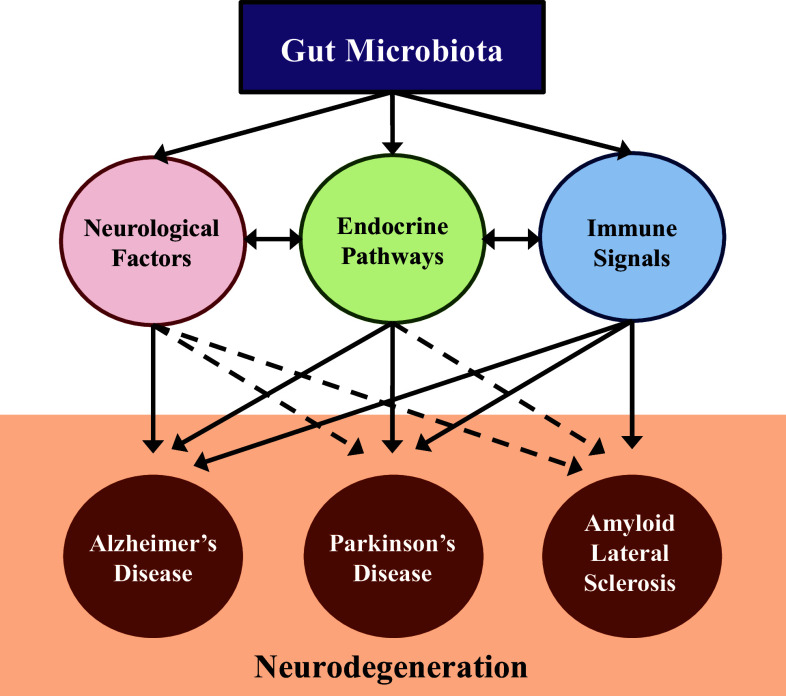

The gut–brain axis consists of the entirety of the intestinal microbiota, ENS, parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, CNS, neuroendocrine connections, humoral pathways, cytokines, neuropeptides and signaling molecules [13]. There are three main modes of communication between the gut and the brain, namely (1) neuronal messages carried by vagal afferents, (2) endocrine messages carried by gut hormones and (3) immune messages carried by cytokines [1, 14] (Fig. 1). The impact of the gut microbiota on the brain is profound and has been recognized to affect behavior (anxiety, depression, learning and memory, sociability), microglial activity, BBB integrity, neurogenesis, and neurotransmitter production (reviewed in Ref. [15]). Recently, it has been realized that brain injury and different psychological states can also affect the composition of the gut microbiota and possibly precipitate disease. For example, brain injury in the form of stroke was shown to alter the composition of the caecal microbiota in mice with specific changes to Peptococcaceae and Prevotellaceae, correlating to the extent of injury [16].

Fig. 1.

Gut microbiota influences neurodegenerative diseases through various pathways. Research linking changes in the gut microbiota to neurodegenerative diseases is still emerging. There are many established studies linking the pathways influenced by the gut microbiota (neurological, endocrine and immune) to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration; however, further studies confirming these microbiota-related linkages are required. In addition, there are many studies that confirm a relationship between the endocrine, neurological and immune signaling pathways contributing to the complexity of the neurodegenerative pathology. In the figure, solid lines represent pathways that are confirmed and the dotted lines have yet to be fully established

Gut dysbiosis is linked to disease

Evidence suggests that the gut microbiota, especially when in a state of dysbiosis, can influence neurological disease progress and even initiate disease onset [17]. There is also a growing realization that the reduced diversity in the aging gut microbiota may be a major factor in the development of neurodegeneration [18, 19]. One of the major mechanisms linking the microbiota to age-related diseases is neuroinflammation [20]. The gut microbiota plays a key role in the activation of microglia [21] and it has been suggested that manipulation of the gut microbiome, especially with short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria, could modulate neuroimmune activation [18, 22]. This relationship could explain the high percentage of gastrointestinal disturbances comorbid with neurodegenerative disease including microbial dysbiosis, constipation, diarrhea, vitamin deficiencies, obesity and diabetes [23–25]. The prevalence of these comorbidities is indisputable, indicating strong functional consequences of the gut–brain axis in neurodegeneration [26].

Neurodegenerative diseases commonly have a sporadic pathology meaning that the disease is triggered by an accumulation of harmful and random interactions with the environment. For example, Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are both linked to the exposure of environmental toxins, such as herbicides, fungicides and pesticides [27], in addition to lifestyle habits such as diet and stress [28]. Notably, in response to environmental stressors such as oxidative stress, the relative balance of microbiota population, and consequently its metabolic and genomic expression is altered implementing broad physiological changes in metabolism, endocrine signaling and innervation in the human host [29]. Further, many of the early symptoms of neurodegenerative disease reside in the GIT, suggesting that dysbiosis may even trigger neurodegenerative disease [30].

Neurological disorders and their connection to gut microbiota

AD, PD, multiple sclerosis (MS) and amyloid lateral sclerosis (ALS) are categorized as neurodegenerative diseases. Although each of these diseases has distinct physiological manifestations, they do have common underlying etiologies linking their pathology, most of which are associated with normal aging. Interestingly, the gut microbiota and its downstream effectors broadly intersect many of these pathways, indicating that management of the microbiota could have therapeutic potential for the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Common pathways in neurodegeneration

Oxidative damage and inflammation are two major systemic conditions that aggravate neurodegeneration and both states are fueled by the normal physiological decline that occurs with age. Generation of reactive oxidative species (ROS) primarily occurs in the mitochondria where 0.4–4% of electrons traveling through the electron transport chain (ETC) escape and react with an oxygen molecule to create a superoxide radical [31]. Normally, these escaped radicals are converted to harmless species by the cells’ anti-oxidant defense systems; however, with age, the progressive loss of cellular defenses leads to an accumulation of cellular, genetic and membrane damage and eventually cell death [32]. The brain is particularly sensitive to oxidative damage as neurons have high energy demands and are almost exclusively post-mitotic cells making their polyunsaturated fatty acid rich membranes more sensitive to ROS-induced peroxidative damage [33]. Indeed, oxidative damage in PD and AD is a major factor in their progression, especially considering that the areas affected by the degeneration are selectively sensitive to oxidative stress, particularly in AD [34]. The slow accumulation of ROS in neurons stimulates cytokine release and consequently microglial activation and neuroinflammation. The pathology of oxidative damage and inflammation creates a vicious cycle cumulatively known as ‘inflamm-aging’, which is defined as a chronic low-grade systemic proinflammatory state characterized by elevated cytokines and inflammatory mediators with no precipitated cause [35]. Inflamm-aging describes a common basis for a broad spectrum of age-related pathologies, including neurodegeneration [36].

Recently, disrupted energy metabolism, such as that present in diabetes and obesity, has been linked to the development and prognosis of neurodegenerative disease. Several comprehensive reviews have been written on this topic [5, 6, 18, 19, 37], so further elaboration will not be done here.

Age-related changes in the gut microbiota observed in neurodegenerative diseases

Aging is associated with clear shifts in the composition of the gut microbiota. In general, there is a loss of gut microbial diversity in the aging gut [38, 39]. The phyla Bacteriodetes and Firmicutes remain dominant, although their relative proportions may change. There may also be an increase in pathogenic bacteria (pathobionts) at the expense of beneficial bacteria (symbionts), an increase in Proteobacteria spp. with a decrease in Bifidobacteria spp., a reduction in butyrate-producing species (Ruminococcus spp., Faecalibacterium spp., etc.) and an increase in microbiota known to stimulate an inflammatory response (Escherichia spp., Enterobacteriaceae spp., Bacteroides spp., Clostridium difficile, etc.) [36, 38, 39]. Interestingly, centenarians typically do not experience these harmful changes and have marked differences in their microbiota populations compared to other elderly populations, indicating that a healthy microbiota may be one of the keys to longevity [36, 39].

Striking variations in the composition of the gut microbiota of aging patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases has also been observed. One study found that the bacterial metabolite indican, a marker of intestinal dysbiosis, was significantly elevated in PD patients indicating a broad microbial dysbiosis [40]. In a large study cohort including 72 PD and 72 healthy subjects, high-resolution 16S sequencing revealed a 77.6% decrease in Prevotellaceae in the PD patients. This is significant as Prevotellaceae is one of the main producers of mucin, a highly glycosylated protein that produces a barrier along the epithelial wall against invading pathogens. This group also found a significant increase in Enterobacteriaceae, which was positively correlated with postural instability [41]. In a similar study, intestinal biopsies of PD patients indicated marked differences in the sigmoid mucosa, significant reductions in anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria (i.e., Roseburia and Faecalibacterium spp.) and a clear increase in proinflammatory Proteobacteria species of the genus Ralstonia compared to healthy age-matched controls [42]. This group has also shown that the accumulation of α-synuclein (α-Syn) neurons tend to first occur in the sigmoid mucosa of patients, 2–5 years before developing neurological symptoms of PD [43]. Based on these findings, this group hypothesized that PD pathology is subsequently manifested to the brain via α-Syn translocation in a prion-like fashion or through the induction of inflammation and oxidative stress. Variations in the PD gut microbiota have also been associated with reduced levels of fecal SCFAs, which were postulated to induce alterations in the ENS contributing to the reduced gastrointestinal motility observed in PD patients [44]. Reductions in butyrate is notable in PD patients as sodium butyrate is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor that protects dopaminergic neurons from degeneration by upregulating neurotrophic factors including brain-derived growth factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [45, 46]. Interestingly, metagenomic studies also indicated lower counts of metabolic genes indicating metabolic dysregulation in PD patients [42]. In PD patients, it has been found that fecal transplants from healthy donors improve both the motor and non-motor symptoms of PD outlining a novel therapeutic option by modifying of the gut microbiota [47]. To test this effect directly, it was found that germ-free α-Syn overexpressing mice retained higher physical coordination than their wild-type counterparts, indicating that the microbiota is responsible for the manifestation of the physical symptoms of PD. α-Syn mice with a complex microbiota developed the same physical impairments and physiological effects as the germ-free PD mice; however, the effects were significantly delayed by 12 weeks. In addition, it was found that microbes in the disease model promote α-Syn-dependent activation of microglia within the brain regions affected in PD, which exacerbates the disease phenotype by promoting inflammation [22]. Interestingly, transplant of fecal samples from PD patients into GF mice promoted significant α-Syn-mediated motor dysfunctions in the humanized PD mice, but not in mice inoculated with fecal matter from healthy individuals [22].

In AD, there is also evidence for gut dysbiosis, however, less direct. Several bacterial species have been found to produce or aggravate the production of amyloid β (Aβ) plaques including B. subtilis, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Mycobacterium spp., Salmonella spp., Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp. [6]. There have also been reports of increased proportions of Gram-negative bacteria in AD patients coupled with mucosal disruption in response to this dysbiosis. Nonetheless, there are clear connections between a disrupted gut microbiota and the pathology of AD that could be targeted with probiotic and prebiotic therapy to alleviate its underlying symptoms.

The influence of gut microbiota, gut–brain axis and probiotics in neurodegenerative disease

There are many interlocking hormonal and biochemical pathways relating the health of the GIT to the brain creating a strong therapeutic potential for the use of probiotics against neurodegeneration. One common theme linking specific microbiota to the prevention of neurodegeneration is a broad and potent anti-inflammatory action. Embedded in the subepithelial lamina propria tissue of the GIT are antigen-presenting innate immune cells including dendritic cells and macrophages. This positioning puts the immune cells in close proximity to the gut microbiota, invading pathogens and antigens that breach the protective epithelial barrier allowing efficient immunological communication between the external environment and the systemic immune system [48]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) on these cells recognize the microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) from bacteria and other microbes, which trigger signaling cascades leading to pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokine expression. This is highly significant as neuroinflammation is highly correlated with neurodegeneration, behavioral and other neurological deficits [49, 50]. In addition, through the production of secondary metabolites, the microbiota can orchestrate several levels of communication with host physiology including insulin control, lipogenesis, apoptosis, neuronal and hormonal signaling. The action of several microbial species on each of these aspects is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the effect of specific probiotics on neurological disorders

| Probiotic strain | Model | Neurological effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroprotection | |||

| Clostridium butyricum | Male ICR mice (cerebral I/R injury; stroke) |

C. butyricum improved neurological deficits Improved anti-oxidant capacity (increase in SOD and decrease in MDA levels) Decreased apoptosis (caspase-3 and Bax levels decreased, Bcl-2/Bax ratio increased) |

[152] |

|

L. helveticus R0052 B. longum R0175 |

WT mice stressed with water avoidance stress (WAS) |

Probiotic treatment attenuated HPA axis and ANS activities in response to WAS Prevented WAS-induced decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis and expression changes in hypothalamic genes involved in synaptic plasticity |

[153] |

| Multiple sclerosis | |||

| B. animalis | Rat model of EAE: autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

Probiotic reduced duration of clinical symptoms Improved body weight gain Reduced cytokine expression |

[154] |

|

B. fragilis PSA |

In vivo mouse model of EAE |

Prophylactic treatment delayed EAE symptom onset and reduced symptom severity Reduced expression of cytokines (IL-17), IFNγ and RORγt Therapeutic treatment reduced disease severity |

[155] |

|

L. paracasei DSM 13434 L. plantarum DSM 15312 L. plantarum DSM 15313 |

In vivo mouse model of EAE |

Probiotic treatment reduced neuroinflammation Induced regulatory T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes Enhanced TGFβ1 expression Combination of three strains suppressed progression and reversed clinical histological signs of EAE |

[156–159] |

|

L. casei L. acidophilus L. reuteri B. bifidum S. thermophilus |

Mouse model of EAE: MOG35055 peptide in CFA containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis and pertussis toxin |

Prophylactic treatment suppressed EAE development and delayed progression Inhibited proinflammatory Th1/Th17 polarization Induced IL-10 and/or Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells |

[158] |

| Anxiety and memory deficits | |||

| L. helveticus R0052 | WT and IL-10 deficient 129/SvEv mice on normal or Western-style diet |

Prevented anxiety-like behavior and memory impairment in mice with proinflammatory state and western diet Decreased inflammation and fecal corticosterone in WT mice on western diet |

[160] |

|

L. helveticus L. rhamnosus |

Streptozocin injected mice (diabetes model) |

Probiotics improved the impaired special memory in the diabetic animals Recovered declined basic synaptic transmission Restored hippocampal long-term potentiation |

[161] |

|

L. rhamnosus R0011 L. helveticus R0052 L. casei Shirota |

Female SPF mice | Memory impairment induced by C. rodentium infection was prevented by daily probiotic treatment | [162] |

| Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome | Probiotic treatment significantly reduced anxiety symptoms | [163] | |

| Neurodegeneration | |||

| L. fermentum NCIMB 5221 |

Strains of L. fermentum potently secrete FA, a molecule that has potent anti-AD activity FA reduced Aβ fibril formation, neuroinflammation and restores learning and memory deficits in AD models |

[61, 164] | |

| VSL#3 | Aged (20–22 months) Wistar rats |

Probiotic treatment attenuated the age-related deficits in long-term potentiation Decreased markers of microglial activation Increased expression of BDNF and synapsin Strong downregulation of genes involved in neurodegeneration (Alox15, Nid2,PLA2G3) |

[165] |

|

L. rhamnosus R0011 L. helveticus R0052 |

Myocardial infarction rats |

Prophylactic probiotic treatment reduced the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 proapoptotic activity in the amygdala and dendrite gyrus Akt activity was increased in similar areas |

[166] |

|

L. helveticus R0052 B. longum R0175 |

WT mice stressed with water avoidance stress (WAS) |

Probiotic treatment attenuated HPA axis and ANS activation in response to WAS Prevented WAS-induced decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis and expression changes in hypothalamic genes involved in synaptic plasticity |

[153] |

| C. butyricum | Mouse model of vascular dementia (permanent right unilateral common carotid arteries occlusion) |

Significantly attenuated the cognitive dysfunction and histopathological changes Increased levels of BDNF and Bcl-2, decreased levels of Bax supporting anti-apoptotic state Induced Akt phosphorylation Reduced neuronal apoptosis |

[167] |

Biomolecules in neurological disease that can be targeted by manipulating gut microbiota

Commensal microbiota produces a variety of neuroactive molecules that directly or indirectly impact signaling in the CNS (rev in Ref. [51]). In addition, there are extensive endocrine and molecular signaling cascades interlacing the gut and brain that co-regulate key processes. Below is an overview of how biomolecules derived from the gut microbiota impact various hormonal and molecular signaling pathways in the CNS and can be important towards the development of neurodegenerative disease.

Gut-derived ferulic acid impacts neurological health

Ferulic acid (FA), or trans-4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid, is a phenolic compound abundantly found in seed plants (rice, wheat and oats), vegetables (tomatoes and carrots) and fruits (pineapple and orange). Traditionally, plants and herbs containing high levels of FA have been used in Chinese medicine for its potent inhibition of ROS generation and anti-inflammatory properties [52, 53]. In modern medicine, FA is recognized as a potent ROS scavenger with therapeutic potential in various chronic diseases including neurodegeneration, cancer, accelerated cell aging, obesity and diabetes [54]. Considering neurodegeneration, FA directly impacts neurons and can stimulate proliferation of neural stem cells both in vitro and in vivo [55]. For the latter, FA increased the number of neurons in the dentate gyrus of corticosterone-treated mice, indicating the potent ability of FA to stimulate neurogenesis in vivo. Therapeutically, FA was shown to reverse the morphological damage sustained through a chronic mild stress depression paradigm in rats by inducing neurogenesis via upregulation of nerve growth factor (NGF) and BDNF [56]. More recently, FA has become a key target for mediating communication between the commensal microbiota and the brain. Apart from dietary sources, FA is rapidly and abundantly synthesized by some gut microbiota via a ferulic acid esterase gene, the most potent being L. fermentum NCIMB 5221 [57] and B. animalis [58]. There are several other species that contain feruloyl esterase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes and releases FA from its bound state including L. plantarum NCIMB 8826 [57, 59], indicating the necessity of having a complete community of healthy microbiota to support the action of ferulic acid.

There has been extensive research linking the pathology of AD with the therapeutic potential of FA. FA was shown to prevent Aβ-related toxicity both in vitro and in vivo AD models by directly inhibiting Aβ aggregation and β-secretase activity [60, 61]. Indeed, oral FA treatment administered for six months reduced several typical AD behavioral phenotypes in mice while simultaneously reducing Aβ fibril formation, the cleavage of β-carboxy-terminal amyloid precursor protein (APP), neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [61]. In a similar long-term administration model, FA was shown to destabilize Aβ1–42-induced learning and memory deficits and amyloid deposition [62].

Accumulation of ROS underlines a key pathological feature of most neurodegenerative diseases and FA has been shown to be protective against oxidative neurological damage in several disease models. For example, FA is neuroprotective against cerebral ischemia in rats, whose major pathological feature is oxidative stress [63], via its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects [64]. To delineate these effects, FA administered to rats 2 h prior, concurrently or 2 h following induction of cerebral ischemia was found to be neuroprotective and downregulated glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and several apoptotic markers including mitochondrial Bax, cytochrome c and cleaved caspase c [65]. One mechanism explaining FA’s protective action against ROS can be explained by the regulation of peroxiredoxins (PRX) and thioredoxin (Trx) [66]. PRX and Trx are ubiquitous anti-oxidant proteins that regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis while providing neuroprotection (rev. in Ref. [67]). Notably, the expression of PRX proteins is inversely correlated with aging, which could correlate with the simultaneous rise of ROS [67]. PRX-2 is important to maintain cellular redox homeostasis in neurons and it was shown that transgenic expression of PRX-2 in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia protected neurons from stressful ischemic insults by preventing apoptosis and improving neurological recovery [68]. PRX-2 normally keeps certain peroxides, such as Trx, in a reduced state, thereby signaling a pro-survival state and resistance to oxidative stress. When there is an over-consumption of PRX-2 due to increased oxidative stress, Trx is converted to its oxidized state leading to the activation of pro-death cascades including apoptosis signaling kinase 1 (ASK1) and the downstream MKK/JNK pro-death signaling pathway [68, 69]. Interestingly, PRX and Trx protein expression are consistently dysregulated in neurodegenerative diseases and are related to elevated microglial activation and reduced anti-oxidant activity (rev in Ref. [67]). Based on these mechanisms and relation to neurodegeneration, it is significant to note that FA prevents both the ischemia-mediated attenuation of PRX and the corresponding oxidation of Trx and the dissociation of Trx from ASK1, therefore preventing apoptosis and providing neuroprotection [66].

FA also inhibits caspase-3 expression following ischemic damage, which is a major source of apoptotic cell death in neurodegenerative diseases [70]. For example, neuronal ischemic stress is associated with reduced levels of phosphorylated Akt [71], and correspondingly, elevated levels of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), which is the main activator of collapsing response mediator protein 2 (CRMP-2), an initiator of apoptosis [72] and mediator of neurite retraction [73]. Indeed, phosphorylated CRMP-2 is associated with high neurofibrillary tangle formation in AD [74] and prevention of neurite outgrowth in damaged neurons [75], and may even precede physiological symptoms of AD [76]. FA can inhibit apoptosis by preventing CRMP-2 expression by upregulating signaling through Akt consequently inhibiting the GSK3β pathway [71]. Not only does this have direct implications for stress-induced apoptosis, but the Akt pathway is highly integrated in the pathophysiology of PD outlining a possible broad mechanism of action in neurodegeneration.

Short-chain fatty acids manipulate neurodegenerative disease via the gut microbiota

The microbiota is responsible for the production of several metabolites formed by the fermentation of soluble fibers such as galacto-oligosaccharides and fructo-oligosaccharides. These metabolites include the SCFAs acetate, propionate and butyrate and are produced by fermentation mediated by Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Roseburia and Prevotella species [77]. The type of SCFAs produced depends both on the type of fiber consumed and the relative population of microbiota in the gut. For instance, microbes in the Firmicutes phyla, particularly the genera Roseburia, Eubacterium and Lachnospiraceae of the Clostridia class actively produce butyrate while Bifidobacteria spp. produce lactate and acetate [78]. In contrast, the actions of SCFAs also influence the functional profile of gut microbiota, especially with regards to endocrine signaling.

SCFAs have a range of regulatory activities beneficial to the host, notably the regulation of systemic energy homeostasis and colonocyte metabolism [79]. In the GIT, SCFAs implement signaling through the G-protein coupled free fatty acid receptors (FFAR)2 and FFAR3 on the gut epithelium, but can also be passively or actively transported into central circulation where they have broad physiological effects [80] which play a role in lipid, glucose and cholesterol metabolism [81–83]. SCFAs are also well-known to have potent anti-inflammatory effects, which have been described in detail in several reviews and will not be further elaborated here [84–86].

In particular, propionate initiates intestinal gluconeogenesis via FFAR3 signaling [87]. The released glucose from the gluconeogenesis processes enters directly into the portal vein where glucose sensors transduce the glucose satiation signals to the brain [88]. It is through these afferent circuits that the SCFA’s action on the glucose regulation in the gut lumen influences central signaling processes. One of the direct targets of propionate-induced intestinal gluconeogenesis is the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV), which receives inputs from the ventral vagus nerve [89]. This is a notable interaction as the activity in the DMV is an early indicator of PD and AD [90], indicating that the production and regulation of propionate intestinal gluconeogenesis could be a major factor in the early stages of neurodegeneration. Butyric acid also has a direct effect on vagal afferents [91], a stimulation that has been shown in clinical trials to be beneficial for cognition in AD patients [92, 93].

Apart from energy homeostasis and direct vagal stimulation, SCFAs can act as endocrine signaling molecules and influence a number of biochemical pathways systemically and in the brain. SCFAs can easily enter circulation from the gut and be transported across the BBB by monocarboxylate transporters [94], directly influencing brain biochemistry [87, 95]. For example, butyrate inhibits HDAC activity resulting in hyper acetylation and loosening of the chromatin. Consequently, there is an alteration of epigenetic signatures facilitating access of DNA repair enzymes [96] to transcribe various regulatory genes. Through this mechanism, butyrate, upregulates the regulatory regions of the Forkhead box (Foxo) gene locus, which are particularly sensitive to regulation by acetylation [97]. FOXO is a central factor to longevity as it induces expression of several life-promoting processes including anti-oxidant genes, autophagic factors and stress-response genes [98]; however, in disease states, such as patients afflicted with PD, FOXO, which also transcriptionally regulates apoptotic genes, can induce cell death [99], indicating that the tight regulation of FOXO is critical for the balance between cell death and cell survival. Particularly in neurodegeneration, the induction of autophagic genes by FOXO has proven to be a key neuroprotective function [99, 100].

There have been several studies indicating the direct neuroprotective potential of butyrate through its HDAC inhibitory action and effects on FOXO expression in both in vitro and in vivo models of neurodegenerative disease. In mouse primary cultured neurons, the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate, also an HDAC inhibitor, was shown to be neuroprotective by inhibiting apoptosis pathways in an NMDA-induced excitotoxicity model [101]. Further, in an aged C. elegans model engineered to express a temperature-sensitive human transgene of Aβ, β-hydroxybutyrate delayed AD’s Aβ toxicity and decreased Parkinson’s α-Syn aggregation in a DAF-16/FOXO-dependent manner [102]. A similar result was seen with butyrate itself through the histone acetyltransferase action of CREB-binding protein in the hypothalamus [103]. Similarly in C. elegans, inhibition of the insulin signaling pathway (daf-2 RNAi) reduced Aβ1–42 toxicity due to aging in a DAF-16/FOXO-dependent manner indicating that FOXO is essential for regulating the age-induced toxicity of Aβ aggregation [104]. In PD, it was shown in a Drosophila melanogaster early onset PD model that FOXO was protective against PD by managing mitochondrial dynamics [105]. Altogether, manipulation of FOXO, possible through the HDAC inhibitory activity of butyrate, can be a potential therapeutic and preventative target for neurodegenerative diseases.

SCFAs modulate neurotransmitter synthesis and expression of several neurotransmitter receptors including nicotinic and GABA receptors [106]. The ability of SCFAs to have such a broad effect on neurogenesis genes is attributed to their HDAC inhibitory activity and the corresponding increase in acetylation of neurotrophic genes including BDNF and NGF [107]. Interestingly, only propionic acid and not butyric acid was able to modulate serotonergic signaling by inducing the expression of tryptophan 6-hydroxylase 1 in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells [106]. Similarly, in a conventional and GF mouse humanized with a healthy human microbiota, an increase in tryptophan hydroxylase 1 was noted, an effect deemed to be dependent on the action of SCFAs on EC cells [108]. Further, in an ex vivo rat colonic model, SCFAs were shown to increase serotonin secretion into the lumen possibly from the stimulation of serotonin receptors on the vagal sensory fibers [109]. These findings are significant as the majority (>90%) of the body’s serotonin is produced in the intestinal EC cells making SCFA regulation imperative for serotonin regulation in the brain [110]. SCFAs, especially butyrate and propionate, can also control the production of catecholamines by regulating tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression [111] in addition to several dopamine biosynthesis, degradation and transport genes [106]. This is very significant in the pathology of PD as tyrosine hydroxylase is the rate-limiting step to dopamine synthesis, which is often downregulated in the substantia nigra region of affected patients. A further study found in PC12 cells that both butyric and propionic acid significantly downregulated amyloid beta A4 protein precursor expression by approximately six- and threefold, respectively [106], indicating the potential neuroprotective roles against AD. Indeed, butyrate through its HDAC inhibitory activity has been shown to improve memory function in a late-stage AD mouse model and increase expression of genes implicated in associative learning [112].

The role of microbiota-produced gut histamine in neurodegenerative disease

Histamine was recently identified as a possible therapeutic agent against neurodegenerative diseases, notably MS and AD [113]. Histamine is a biogenic monoamine that is produced by EC cells in the GIT and is directly released from certain Lactobacillus spp. It plays a role in a wide variety of physiological functions including cell proliferation, allergic reactions, wound healing and regulation of immune cells as well as acting as a neurotransmitter in the brain [114]. There is a high density of histamine receptors on neurons of the striatum, thalamus, hippocampus, substantia nigra, amygdala and other areas, indicating the broad effects of histamine throughout the CNS.

Depending on the receptor that it acts upon, histamine can have either pro- or anti-inflammatory properties [113, 115]. In the brain, histamine induces an allergic inflammatory response by increasing the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6 and various chemokines. However, the action of histamine through a different receptor, namely H4R, induces an anti-inflammatory response which is particularly critical in the CNS [113]. H4R leads to the activation of several signaling factors including the JAK-STAT, MAPK/ERK and PI3 K, ultimately leading to the regulation of cytokine release, dendritic cell function and recruitment of T regulatory cells to sites of acute inflammation [116, 117]. Interestingly, histamine was recently found to be a product of gut microbial metabolism. Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Streptococcus, Pediococcus and Enterococcus spp. all have the histidine decarboxylase gene and can produce histamine [118]. L. reuteri, which converts the dietary l-histidine into histamine, was previously identified as an immunomodulatory probiotic that can suppress TLR signaling and ultimately reduce the expression of TNFα through the modulation of PKA and ERK signaling [119].

In the context of neurodegeneration, elevated levels of histamine have been found associated with AD and are thought to elevate nitric oxide levels, thereby stimulating neuroinflammation [120]. This parallels the hypothesis that low-grade inflammation contributes to the development of neurodegenerative diseases. However, there have also been reports of deficit histaminergic signaling in the rats afflicted with vascular dementia [121]. Clearly, the concentration and localization of particular histamine receptors both centrally and systemically have a wide range of effects on the development of neurodegeneration making its regulation through the gut microbiota a possible route for therapy [114].

Microbiota-modulated ghrelin impacts neurological function

Ghrelin is a peptide produced in the GIT that acts both as a hormone to convey satiety signals and as a neuropeptide in the CNS. Ghrelin is secreted when the stomach is empty to facilitate the feeling of hunger. Apart from this, ghrelin is a key regulatory factor for many metabolic processes including energy homeostasis, inflammation and neuromodulation [122, 123]. Ghrelin receptors are diffused throughout the brain but have particularly high concentrations in the hippocampus, substantia nigra [124], raphe nuclei and ventral tegmental area [125]. Gut hormones such as PYY and cholecystokinin produced by the EC cells under the influence of the microbiota, interact with ghrelin signaling to induce feelings of satiety and direct other regulatory events [126]. Notably, the administration of prebiotics that alter microbiota populations such as Bifidobacterium spp., have been shown to reduce ghrelin secretion in humans [127]. Further, there is a clear correlation between ghrelin and the composition of the gut microbiota in rats under various nutritional statuses and levels of physical activity indicating the influence of gut microbiota dynamics on ghrelin secretion [128]. Ghrelin secretion is significant in the context of neurodegeneration as ghrelin has been shown to elicit neuroprotective effects in both AD and PD [129].

The neuroprotective abilities of ghrelin were first shown in ischemic damage models in rats where exogenous ghrelin treatment reduced ROS accumulation, protected mitochondrial integrity, and therefore promoted an anti-apoptotic environment [130]. Since then, ghrelin has been implicated in promoting synaptic plasticity and rescuing memory deficits in AD models [123]. In addition, in an Aβ mouse model of AD, ghrelin was shown to reduce the toxic accumulation of Aβ while inhibiting the excessive inflammatory response [131]. Correspondingly, AD patients have a reduced ghrelin representation in the brain, indicating that ghrelin does play a key role in its pathology [123].

In PD, activation of ghrelin receptors on substantia nigra neurons stimulates tyrosine hydroxylase expression, the rate-limiting step in dopamine synthesis. Further, ghrelin provided protection against a toxic model of PD by reducing dopaminergic cell loss and protecting mitochondrial integrity [132]. This and other studies were followed up by more mechanistic-based approaches to understand the role of ghrelin in PD, and it was found that acylated ghrelin protected 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced loss of tyrosine hydroxylase in mice while protecting GFAP expression [133]. It is clear that ghrelin has both broad-acting and local responses in the brain leading to its neuroprotective effects and the ghrelin-producing abilities of gut bacteria make it a promising therapeutic target for neurodegeneration.

Kynurenine pathway signaling in the gut–brain axis

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid critical for the synthesis of serotonin. Over 90% of serotonin is found in the GIT where it is absorbed from the diet or synthesized by EC cells from tryptophan [110]. Serotonin plays a key role in secretion, peristalsis, vasodilation, perception of pain and nausea through the 5-HT receptors in the GIT. Notably, tryptophan from the GIT can enter circulation, cross the BBB and initiate serotonin synthesis in the brain making tryptophan metabolism in the GIT critical for central serotonergic signaling.

The kynurenine pathway (KP) is the major route of tryptophan catabolism. This pathway is of interest not only because it regulates the amount of bioavailable serotonin, but also because it produces several neuroactive intermediates that have implications in neurodegenerative disorders [134]. Dysregulation of serotonergic and kynurenine routes of tryptophan metabolism influences CNS pathological conditions including dementia, Huntington’s disease and AD [135]. Of interest, probiotic treatment alters kynurenine levels [136].

Two of the key intermediate metabolites of the KP are quinolinic acid (QA) and kynurenic acid (KA). QA stimulates the overactivation of NMDA receptors and consequently stimulates excitotoxicity and neuronal cell death [137]. KA, on the other hand, is an endogenous NMDA receptor antagonist that can modulate the neurotoxic effects of QA and provide neuroprotection [138]. Notably, kynurenine produced in the gut can effectively cross the BBB and contribute to the production of these metabolites directly in the brain. Another metabolite of the KP, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA), induces oxidative stress and promotes ROS production contributing to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases [139]. The balance of QA and KA levels determines the level 3-HAA toxicity in the CNS and their relative abundance in controlled by the expression of the rate-limiting enzymes in the KP.

The rate-limiting enzymes responsible for the initiation of the KP are the hepatic tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and the extra hepatic indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Both enzymes catalyze the conversion of tryptophan to l-kynurenine. TDO is the more processive and dominant enzyme which is inducible by glucocorticoids, whereas IDO is ubiquitously expressed and induced by inflammatory mediators such as IFN-γ [135]. The activity of IDO and TDO leads to the production of the neuroactive metabolites KA, QA and 3-HAA, via separate downstream pathways. A marker of IDO/TDO activity is the kynurenine per tryptophan quotient (KYN/TRP ratio) and it has been shown that the increase in this quotient is proportional to the level of cognitive impairment [140].

The composition of the gut microbiota has a profound effect on the metabolism of tryptophan and regulation of the KP. GF mice have increased levels of tryptophan, which can be normalized following the colonization of mice immediately post-weaning [141, 142]. Interestingly, administration of B. infantis in rats reduced the levels of 5-HIAA, the main metabolite of serotonin and reliable marker of its abundance, in the frontal cortex and also increased plasma tryptophan and KA [136].

There is also evidence that the gut microbiota can directly regulate/impact the activity of the key enzymes in KP. GF mice have reduced IDO activity, which is normalized following the induction of gut microbiota immediately post-weaning [141]. Administration of L. johnsonii leads to the reduction of serum kynurenine levels and was also shown to reduce IDO activity in vitro. The possible mechanism could be linked to the increased secretion of hydrogen peroxide, which activates the peroxidase function of IDO inhibiting its enzymatic activity [143]. This is intriguing as hydrogen peroxide is commonly released in many lactic acid bacteria adding another level of regulation [144].

Apart from excitotoxicity, increased levels of QA promote tau phosphorylation and tangle formation, therefore directly linking this pathway to AD pathogenesis [145]. IDO activity is also upregulated in the AD hippocampus, enriched in the senile plaques of AD [146] and the level of IDO activity is correlated with the level of cognitive impairment [140].

IDO inhibitors are currently being tested for their ability to protect neurons against oxidative damage, and thereby alleviate symptoms of cognitive impairment. Inhibitors of IDO can counter balance their inflammatory-induced induction and consequently reduce QA induction while increasing KA production [147]. There are also other inhibitors that can be exploited in altering the balance of KA and QA such as Ro61-8048 which inhibits kynurenine hydroxylase and has been shown to be protective against HD [148]. Considering the influence of the gut microbiota on regulation of the KP and tryptophan availability, it is possible that proper probiotic therapy could be beneficial in regulating KP dynamics either prophylactically or therapeutically in patients with neurodegenerative disorders.

Microbial-produced neurometabolites

There are many neurometabolites secreted directly from the microbiota and produced by the stimulatory action of the microbiota on secretory epithelial cells. These neurometabolites include neurotransmitters that act directly on CNS signaling cascades and through other biochemical effectors that have direct or indirect implications on CNS health [149, 150]. For example, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains can produce large quantities of GABA in the presence of a suitable substrate [151]. Gut-derived neurometabolites communicate to the CNS by local stimulation of vagal afferents and through their distal endocrine action after being absorbed into the blood stream. These variations in neurotransmitter levels manifest in behavioral changes, such as increased spontaneous motor activity from the elevated levels of dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin in the striatum [150]. This is critical in the management of neurodegenerative disease as there is often a dysregulation of neurotransmitter production in these conditions that ultimately fuel disease progression. In Table 2, a list of neurotransmitters directly secreted by various probiotics is listed.

Table 2.

Potential mechanisms of action of probiotics in neurodegenerative disease

| Probiotic | Neurological factors | Endocrine factors | Immunological factors | References | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vagal | GABA | NA | 5-HT | DA | His | ACh | BDNF | NO | Other | ROS | FA | HPA/Cort | Insulin | Leptin | Ghrelin | IPA | EFA | KP | SCFAs | IL-6 | TNFα | IL-1β | IL-10 | IL-12 | ||||

| Act | But | Pro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bifidobacterium spp. | Y | Y | Y | Y | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | Y | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [151, 168–170] | |||||||||||

| B. animalis | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [32, 58, 171] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| B. breve | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [172–174] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| B. infantis |

↑ cFos |

↓ | Y | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [134, 175–178] | ||||||||||||||||||

| B. longum | Y | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [169] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacillus spp. | ++ | Y | Y | Y | [51] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| B. fragilis | ++ | [179] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B. subtilis | Y | Y | [51] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lactobacillus spp. | ++ | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

↑ PYY |

↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | [118, 151, 180–185] | ||||||||||

| L. acidophilus | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [186, 187] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. brevis | Y | ↑ | [151] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. lactis | Y | Y | ↑ | ↑ | [51, 185] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. reuteri | ++ | Y | Y | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [179, 188–190] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| L. rhamnosus | Y |

P75 P40 |

↓ | X | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [190–195] | |||||||||||||||||||

| L. fermentum |

↓ GF AP |

↓ | ↑ | ↑a | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [189, 190, 196, 197] | ||||||||||||||||

| L. plantarum | Y | Y | Y | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [182, 198] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Escherichia spp. | Y | Y | Y | ↓ | Y | Y | Y | [199, 200] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Streptococcus spp. | Y | Y | Y | ↑ | [118, 180, 185, 199] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enterococcus spp. | Y | Y | ↑ | [118, 185, 201] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacillus spp. | Y | Y | Y | ↑ | [151, 185, 199] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clostridium spp. | Y | Y | ↑ | Y | Y | Y | Y | [78, 185, 202] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacteroides spp. | ↑ | Y | Y | [185, 203] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The bold texts represent a heading of a particular group of probiotics. They represent various sub-species within that group have the indicated effect

Vagal Vagal stimulation, GABA gamma-aminobutyric acid, NA noradrenaline (norepinephrine), 5HT serotonin, DA dopamine, Hist histamine, ACh acetylcholine, BDNF brain derived neurotrophic factor, NO nitric oxide, p75 PYY peptide YY, p75/p40 anti-apoptotic proteins, GFAP glial fibrillary acidic protein, ROS reactive oxygen species, FA ferulic acid, HPA/CORT hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis/cortisol, IPA indole-3-propionic acid, EFA essential fatty acids, KP kynurenine pathway, Act acetate, But butyrate, Pro propionate

a L. fermentum reduces insulin resistance, hence increases insulin in pathological metabolic disorders. ‘++’ indicated a strong direct nervous connection. ‘↑’ The known effect of a certain probiotic is an increase in the respective factor. ‘↓’ The known effect of a certain probiotic is a decrease in the respective factor. ‘Y’ indicates that the effect of a certain probiotic is modulatory. ‘X’ indicated that it is known that a certain probiotic does not cause an effect. ‘ ’ No indication means that the effect of a particular probiotic has not been reported or was not found

Conclusion

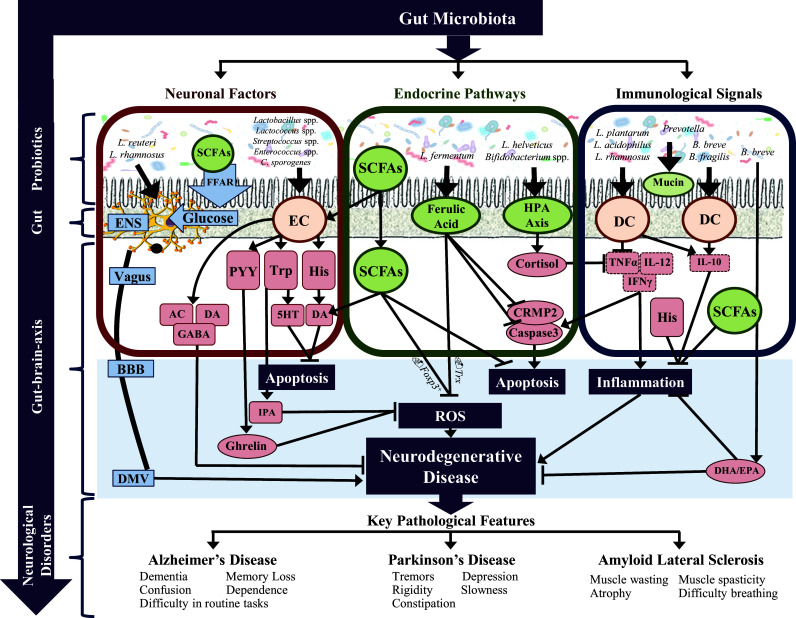

The gut–brain axis encompasses several biochemical pathways that functionally link the health of the gut microbiota and the CNS (Fig. 2). Any imbalance in the commensal gut microbiota leads to aberrant endocrine, immunological and neuronal signals that ultimately harm neuronal development and aggravate the age-related symptoms of neurodegenerative disease. The major common feature of neurodegeneration is the gradual failure of physiological systems with age, and this includes the shifting populations of the gut microbiota that propagate an inflammatory response, stimulate oxidative stress, unfavorably alter production of neuroactive molecules and modulate metabolic signals that disrupt energy metabolism in the brain. Biotherapy using probiotics shows immense potential as therapeutic or prophylactic agents against neurodegenerative disease as they reinstate balance to the microbiota and the corresponding pathways that link microbial and host metabolism. The further development and characterization of the biochemical effects of probiotic consumption on people suffering from neurodegenerative disease needs to be investigated to fully elucidate the scope of probiotics for these debilitating diseases.

Fig. 2.

Investigating the mechanisms of probiotic treatment in neurological signaling. The gut microbiota impacts neurological disease via three main modalities: (1) neuronal factors, (2) endocrine pathways and (3) immunological signals. The microbiota present in the gut lumen plays a specific role in influencing these three pathways. (1) Individual bacteria can both produce certain neurotransmitters such as DA and ACh while the same and others stimulate neurotransmitter production via the secretory ECs such as 5HT and GABA. The ECs cells can also produce several neuroactive factors including PYY, Typ and His. The neurotransmitters and neuroactive molecules enter blood circulation and cross the BBB influencing CNS signaling. Some neuroactive components also go further to stimulate the production of gut hormones in the CNS such as ghrelin and IPA that have dual roles in the CNS including neuroprotection. Further, individual microbiota species can directly stimulate electrical signals in the ENS, thereby propagating signals through the vagus nerve to stimulate the DMV. Finally, the microbiota through the production of SCFAs and FFAR signaling, releases glucose which also propagates signals through the ENS. (2) The gut microbiota directly and indirectly produces a battery of endocrine signaling molecules. SCFAs, including propionate, butyrate and acetate, are major signaling molecules produced by the microbiota that have many roles including stimulation of neurotransmitter synthesis in the periphery and centrally, inhibiting ROS production by upregulating FoxP + transcription and inhibiting apoptosis through caspase cascades. A major mechanism instigated by the gut microbiota is HPA axis stimulation and the consequent release of cortisol. Cortisol suppresses the inflammatory response and influences a number of neurological processes. Ferulic acid is another key molecule produced directly by the microbiota that has a variety of functions including suppression of ROS both directly and by indirectly by PRX/Trx signaling, suppression of apoptosis by inhibiting CRMP2 and caspase 3 expression and either directly or indirectly, suppressing the inflammatory response. (3) A healthy gut microbiota suppresses inflammation, both chronic and pathological. The MAMPs such as LTA and SlpA on the surface of microbiota directly stimulate receptors (TLR and ICAM, respectively) on immunological cells such as DCs. This interaction propagates an anti-inflammatory response with an upregulation of anti-inflammatory factors (IL-10 and IL-4) while suppressing proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6). In addition, some microbiota also directly suppresses proinflammatory cytokines such as the action of B. animalis on IL-6. Finally, the gut microbiota influences the production of mucin, an inhibitory chemical gel that blocks the penetrance of pathogens through the gut. 5HT serotonin, Ach acetylcholine, BBB blood–brain barrier, CRMP2 collapsin response mediator protein family, DA dopamine, DHA docosahexaenoic acid, DMV dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, EC enterochromaffin cell, ENS enteric nervous system, EPA eicosapentaenoic acid, FFAR free fatty acid receptor, GABA gamma-aminobutyric acid, His histamine, HPA hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, IFNγ interferon gamma, IL-10 interleukin 10, IL-12 interleukin 12, IPA indole-3-propionic acid, NA noradrenaline, PRX peroxiredoxin, PYY peptide YY, ROS reactive oxygen species, SCFAs short-chain fatty acids, TNFα tumor necrosis factor alpha, Trp tryptophan, Trx thioredoxin

Author contributions

This review was conceptualized and written by SW with supporting sections written and edited by NL and SYD. Advisement and manuscript suggestions were provided by SPS and SP.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest or competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Burokas A, Moloney RD, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota regulation of the mammalian gut–brain axis. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2015;91:1–62. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsythe P, Bienenstock J, Kunze WA. Microbial endocrinology: the microbiota–gut–brain axis in health and disease. New York: Springer; 2014. Vagal pathways for microbiome–brain–gut axis communication; pp. 115–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer KC, Huus KE, Finlay BB. Microbes and the mind: emerging hallmarks of the gut microbiota–brain axis. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:632–644. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noble EE, Hsu TM, Kanoski SE. Gut to brain dysbiosis: mechanisms linking western diet consumption, the microbiome, and cognitive impairment. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulak A, Bonaz B. Brain–gut–microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. WJG. 2015;21:10609–10620. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedland RP. Mechanisms of molecular mimicry involving the microbiota in neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:349–362. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Smidt H, de Vos WM. Diversity of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2125–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandal RS, Saha S, Das S. Metagenomic surveys of gut microbiota. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2015;13:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everard A, Cani PD. Gut microbiota and GLP-1. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns AJ. Migration of neural crest-derived enteric nervous system precursor cells to and within the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;49:143–150. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041935ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Mahony SM, Clarke G, Borre YE, et al. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain–gut–microbiome axis. Behav Brain Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochoa-Reparaz J, Mielcarz DW, Begum-Haque S, Kasper LH. Gut, bugs, and brain: role of commensal bacteria in the control of central nervous system disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:240–247. doi: 10.1002/ana.22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luczynski P, McVey Neufeld K-A, Oriach CS, et al. Growing up in a bubble: using germ-free animals to assess the influence of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(8):234–248. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houlden A, Goldrick M, Brough D, et al. Brain injury induces specific changes in the caecal microbiota of mice via altered autonomic activity and mucoprotein production. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;57:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catanzaro R, Anzalone MG, Calabrese F, et al. The gut microbiota and its correlations with the central nervous system disorders. Panminerva Med. 2014;57(3):127–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Gut instincts: microbiota as a key regulator of brain development, ageing and neurodegeneration. J Physiol. 2017;595:489–503. doi: 10.1113/JP273106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler CA, Maes M, Slyepchenko A, et al. The gut–brain axis, including the microbiome, leaky gut and bacterial translocation: mechanisms and pathophysiological role in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:6152–6166. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160907093807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jyothi HJ, Vidyadhara DJ, Mahadevan A, et al. Aging causes morphological alterations in astrocytes and microglia in human substantia nigra pars compacta. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:3321–3333. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erny D, Hrabe de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:965–977. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2016;167(1469–1480):e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alam MZ, Alam Q, Kamal MA, et al. A possible link of gut microbiota alteration in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenicity: an update. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:383–390. doi: 10.2174/18715273113126660151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naseer MI, Bibi F, Alqahtani MH, et al. Role of gut microbiota in obesity, type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:305–311. doi: 10.2174/18715273113126660147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekkering P, Jafri I, van Overveld FJ, Rijkers GT. The intricate association between gut microbiota and development of type 1, type 2 and type 3 diabetes. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9:1031–1041. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2013.848793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao M, Gershon MD. The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:517–528. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baltazar MT, Dinis-Oliveira RJ, de Lourdes Bastos M, et al. Pesticides exposure as etiological factors of Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases—a mechanistic approach. Toxicol Lett. 2014;230:85–103. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Virmani A, Pinto L, Binienda Z, Ali S. Food, nutrigenomics, and neurodegeneration–neuroprotection by what you eat! Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8498-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science. 2008;320:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.1155725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldman JG, Postuma R. Premotor and nonmotor features of Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27:434–441. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitsuma T, Odajima H, Momiyama Z, et al. Enhancement of gene expression by a peptide p(CHWPR) produced by Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12. Microbiol Immunol. 2008;52:144–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Michaelis EK. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu X, Raina AK, Lee H-G, et al. Oxidative stress signalling in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2004;1000:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M, et al. Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, et al. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease—is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng J, Palva AM, de Vos WM, Satokari R. Contribution of the intestinal microbiota to human health: from birth to 100 years of age. In: Dobrindt U, Hacker JH, Svanborg C, editors. Between pathogenicity and commensalism. Berlin: Springer; 2013. pp. 323–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassani E, Barichella M, Cancello R, et al. Increased urinary indoxyl sulfate (indican): new insights into gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PAB, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov Disord. 2014;30(3):350–358. doi: 10.1002/mds.26069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keshavarzian A, Green SJ, Engen PA, et al. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1351–1360. doi: 10.1002/mds.26307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shannon KM, Keshavarzian A, Dodiya HB, et al. Is alpha-synuclein in the colon a biomarker for premotor Parkinson’s disease? Evidence from 3 cases. Mov Disord. 2012;27:716–719. doi: 10.1002/mds.25020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unger MM, Spiegel J, Dillmann K-U, et al. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age-matched controls. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;32:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kidd SK, Schneider JS. Protection of dopaminergic cells from MPP+-mediated toxicity by histone deacetylase inhibition. Brain Res. 2010;1354:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Chen PS, Dallas S, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors up-regulate astrocyte GDNF and BDNF gene transcription and protect dopaminergic neurons. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:1123–1134. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guseo A. The Parkinson puzzle. Orv Hetil. 2012;153:2060–2069. doi: 10.1556/OH.2012.29461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith PD, Smythies LE, Shen R, et al. Intestinal macrophages and response to microbial encroachment. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:31–42. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faden AI, Loane DJ. Chronic neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury: Alzheimer disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or persistent neuroinflammation? Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0319-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vivekanantham S, Shah S, Dewji R, et al. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: role in neurodegeneration and tissue repair. Int J Neurosci. 2015;125:717–725. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2014.982795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, et al. Minireview: gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1221–1238. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mancuso C, Santangelo R. Ferulic acid: pharmacological and toxicological aspects. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;65:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trombino S, Cassano R, Ferrarelli T, et al. Trans-ferulic acid-based solid lipid nanoparticles and their antioxidant effect in rat brain microsomes. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;109:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu C-T, Wu J-R, Cheng C-C, et al. Reactive oxygen species-mediated PKC and integrin signaling promotes tumor progression of human hepatoma HepG2. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2011;28:851–863. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yabe T, Hirahara H, Harada N, et al. Ferulic acid induces neural progenitor cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Neuroscience. 2010;165:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu L, Zhang Y, Liao M, et al. Neurogenesis-enhancing effect of sodium ferulate and its role in repair following stress-induced neuronal damage. WJNS. 2011;1(2):9–18. doi: 10.4236/wjns.2011.12002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomaro-Duchesneau C, Saha S, Malhotra M, et al. Probiotic ferulic acid esterase active Lactobacillus fermentum NCIMB 5221 APA microcapsules for oral delivery: preparation and in vitro characterization. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2012;5:236–248. doi: 10.3390/ph5020236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szwajgier D, Dmowska K. Novel ferulic acid esterases from Bifidobacterium sp. produced on selected synthetic and natural carbon sources. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2010;9:305–318. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhathena J, Martoni C, Kulamarva A, et al. Orally delivered microencapsulated live probiotic formulation lowers serum lipids in hypercholesterolemic hamsters. J Med Food. 2009;12:310–319. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Durairajan SSK, Yuan Q, Xie L, et al. Salvianolic acid B inhibits Abeta fibril formation and disaggregates preformed fibrils and protects against Abeta-induced cytotoxicty. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:741–750. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mori T, Koyama N, Guillot-Sestier M-V, et al. Ferulic acid is a nutraceutical β-secretase modulator that improves behavioral impairment and Alzheimer-like pathology in transgenic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan J-J, Jung J-S, Kim T-K, et al. Protective effects of ferulic acid in amyloid precursor protein plus presenilin-1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:140–143. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang L, Wang H, Wang T, et al. Ferulic acid ameliorates nerve injury induced by cerebral ischemia in rats. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:972–976. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srinivasan M, Sudheer AR, Menon VP. Ferulic acid: therapeutic potential through its antioxidant property. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;40:92–100. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.40.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng C-Y, Tang N-Y, Kao S-T, Hsieh C-L. Ferulic acid administered at various time points protects against cerebral infarction by activating p38 MAPK/p90RSK/CREB/Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic signaling in the subacute phase of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sung J-H, Gim S-A, Koh P-O. Ferulic acid attenuates the cerebral ischemic injury-induced decrease in peroxiredoxin-2 and thioredoxin expression. Neurosci Lett. 2014;566:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patenaude A, Murthy MRV, Mirault M-E. Emerging roles of thioredoxin cycle enzymes in the central nervous system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1063–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gan Y, Ji X, Hu X, et al. Transgenic overexpression of peroxiredoxin-2 attenuates ischemic neuronal injury via suppression of a redox-sensitive pro-death signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:719–732. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, et al. Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma YH, Su N, Chao XD, et al. Thioredoxin-1 attenuates post-ischemic neuronal apoptosis via reducing oxidative/nitrative stress. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gim S-A, Sung J-H, Shah F-A, et al. Ferulic acid regulates the AKT/GSK-3β/CRMP-2 signaling pathway in a middle cerebral artery occlusion animal model. Lab Anim Res. 2013;29:63. doi: 10.5625/lar.2013.29.2.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gao C, Holscher C, Liu Y, Li L. GSK3: a key target for the development of novel treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer disease. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23:1–11. doi: 10.1515/rns.2011.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshimura T, Kawano Y, Arimura N, et al. GSK-3beta regulates phosphorylation of CRMP-2 and neuronal polarity. Cell. 2005;120:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu Y, Hamajima N, Ihara Y. Neurofibrillary tangle-associated collapsin response mediator protein-2 (CRMP-2) is highly phosphorylated on Thr-509, Ser-518, and Ser-522. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4267–4275. doi: 10.1021/bi992323h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petratos S, Li Q-X, George AJ, et al. The beta-amyloid protein of Alzheimer’s disease increases neuronal CRMP-2 phosphorylation by a Rho-GTP mechanism. Brain. 2008;131:90–108. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soutar MPM, Thornhill P, Cole AR, Sutherland C. Increased CRMP2 phosphorylation is observed in Alzheimer’s disease; does this tell us anything about disease development? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:269–278. doi: 10.2174/156720509788486572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verbeke KA, Boobis AR, Chiodini A, et al. Towards microbial fermentation metabolites as markers for health benefits of prebiotics. Nutr Res Rev. 2015;28:42–66. doi: 10.1017/S0954422415000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tagliabue A, Elli M. The role of gut microbiota in human obesity: recent findings and future perspectives. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kasubuchi M, Hasegawa S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients. 2015;7:2839–2849. doi: 10.3390/nu7042839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:1509–1517. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fushimi T, Suruga K, Oshima Y, et al. Dietary acetic acid reduces serum cholesterol and triacylglycerols in rats fed a cholesterol-rich diet. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:916–924. doi: 10.1079/BJN20061740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Todesco T, Rao AV, Bosello O, Jenkins DJ. Propionate lowers blood glucose and alters lipid metabolism in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:860–865. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saad MJA, Santos A, Prada PO. Linking gut microbiota and inflammation to obesity and insulin resistance. Physiology (Bethesda) 2016;31:283–293. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Soldavini J, Kaunitz JD. Pathobiology and potential therapeutic value of intestinal short-chain fatty acids in gut inflammation and obesity. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2756–2766. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brahe LK, Astrup A, Larsen LH. Is butyrate the link between diet, intestinal microbiota and obesity-related metabolic diseases? Obes Rev. 2013;14:950–959. doi: 10.1111/obr.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Goncalves D, et al. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut–brain neural circuits. Cell. 2014;156:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]