Abstract

Fungal disease is an increasing problem in both agriculture and human health. Treatment of human fungal disease involves the use of chemical fungicides, which generally target the integrity of the fungal plasma membrane or cell wall. Chemical fungicides used for the treatment of plant disease, have more diverse mechanisms of action including inhibition of sterol biosynthesis, microtubule assembly and the mitochondrial respiratory chain. However, these treatments have limitations, including toxicity and the emergence of resistance. This has led to increased interest in the use of antimicrobial peptides for the treatment of fungal disease in both plants and humans. Antimicrobial peptides are a diverse group of molecules with differing mechanisms of action, many of which remain poorly understood. Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly apparent that stress response pathways are involved in the tolerance of fungi to both chemical fungicides and antimicrobial peptides. These signalling pathways such as the cell wall integrity and high-osmolarity glycerol pathway are triggered by stimuli, such as cell wall instability, changes in osmolarity and production of reactive oxygen species. Here we review stress signalling induced by treatment of fungi with chemical fungicides and antifungal peptides. Study of these pathways gives insight into how these molecules exert their antifungal effect and also into the mechanisms used by fungi to tolerate sub-lethal treatment by these molecules. Inactivation of stress response pathways represents a potential method of increasing the efficacy of antifungal molecules.

Keywords: Fungi, Antifungal peptides, Fungicides, Stress signalling, Hog1, Cell wall integrity

Introduction

Many antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) exert their function primarily through disruption of bacterial, fungal or viral membranes [1]. These peptides are generally cationic and disulphide rich or amphipathic α-helices, and they act by binding to bilayers, disrupting the ordered array of lipids and allowing leakage of intracellular contents [1–4]. Some AMPs have more complicated mechanisms of action, ranging from interaction with surface receptors and triggering of signal transduction pathways, to internalisation of the AMPs followed by interaction with specific intracellular targets [5–8]. These mechanisms are diverse and their true complexity remains poorly defined. Recently, it has become apparent that cellular stress response pathways have a crucial role in protecting fungi against the deleterious effects of antimicrobial peptides. Activation of these pathways also enhances tolerance to antifungal drugs. Conversely, inactivation of the pathways can render fungal cells hypersensitive to antifungal agents.

Stress signalling pathways in fungi

In order to overcome environmental stresses, fungi, like other eukaryotes, rely on the rapid transduction of signals through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [9–11]. These pathways signal through successive phosphorylation of protein kinases. After detection of an upstream signal, a MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) phosphorylates and activates a MAP kinase kinase (MAPKK), which in turn phosphorylates the MAP kinase (MAPK). The activated MAPK can then translocate to the nucleus and induce changes; such as activation of transcription factors, cell cycle regulation and kinase activation, which create an adaptive response to the stress [10, 12–14].

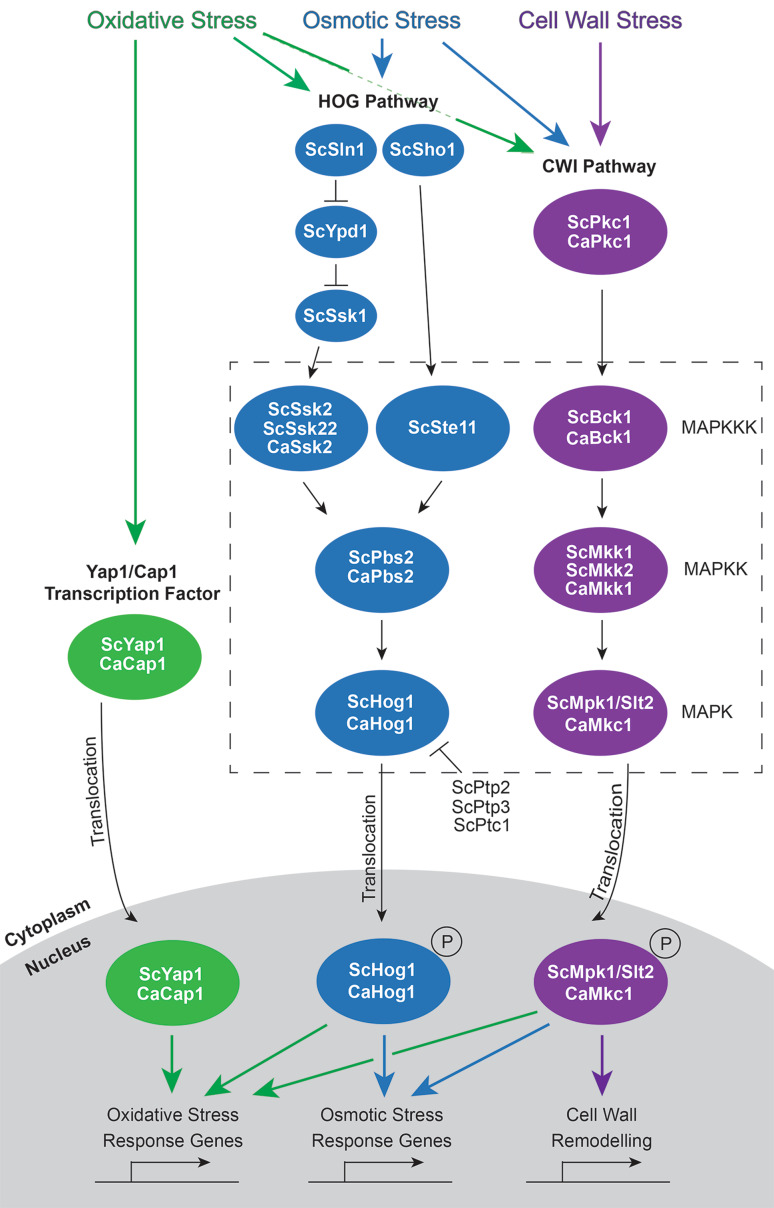

There are several MAP kinase pathways in fungi, controlling functions as diverse as the mating response, cell wall integrity, invasive growth and stress responses [12–14]. The high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) and cell wall integrity (CWI) pathways are particularly important in fungi for response to osmotic, oxidative and cell wall stresses (Fig. 1) [10, 12, 15–20]. Components of these stress response pathways, particularly the terminal MAPKs, are well conserved in diverse fungal species [9]. However, across fungal species, the MAPKs may have different or additional roles in stress tolerance [10, 21]. For example, the HOG pathway is activated by heat and cold stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but these stressors do not activate the HOG pathway in Candida albicans [10].

Fig. 1.

Oxidative, osmotic and cell wall integrity pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. The HOG and cell wall integrity (CWI) MAPK pathways and the ScYap1/CaCap1 transcription factor are responsible for oxidative, osmotic and cell wall stress responses in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans. Phosphorylation cascades result in phosphorylation and activation of a MAPK which translocates to the nucleus and affects expression of stress response genes. The ScYap1/CaCap1 transcription factor resides in the cytoplasm until activated by oxidative stress, whereupon it moves to the nucleus and regulates gene expression. Purple arrows represent cell wall stress, blue arrows represent osmotic stress and green arrows are oxidative stress. Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Ca, Candida albicans

Chemical fungicides and antifungal peptides (AFPs) are diverse molecules with different targets and mechanisms of action [6, 22]. When low concentrations of these antifungal molecules damage the cell, activation of one or more stress response pathways allows the cell to respond to the damage and survive. However, higher concentrations of these molecules generally overwhelm the fungal stress response system leading to inhibition of growth or cell death. In general, low concentrations of antifungal molecule are used to investigate the tolerance mechanisms employed by the fungus to survive antifungal treatment. Knowledge of the pathway that is activated in response to a particular antifungal molecule gives insight into the mechanism of action of that molecule, although it is important to keep in mind that some antifungal molecules may have different mechanisms at higher concentrations.

Oxidative and osmotic stress response

The high-osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway

The HOG pathway is an important stress response pathway in fungi, and is responsible for survival of the fungus in periods of high osmolarity or oxidative stress [16, 23–26]. Ultimately, activation of the HOG pathway leads to an increase in intracellular glycerol which provides protection against osmotic stress [18]. In C. albicans, mitochondrial function appears to be required for activation of CaHog1 in response to oxidative stress [27]. In S. cerevisiae, ScHog1 activation can also lead to downregulation of ergosterol biosynthesis and adaption to osmotic stress through changes in membrane fluidity [28]. While there is low conservation of upstream kinases of the HOG pathway, the MAPK has high sequence identity across many fungal species [9]. C. albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans Hog1 have 80 % and 77 % sequence identity with S. cerevisiae, respectively. Hog1 from the filamentous fungi Aspergillus nidulans (76 %), Neurospora crassa (78 %) and the plant pathogens Fusarium graminearum (79 %) and Magnaporthe grisea (82 %) are also very similar to S. cerevisiae ScHog1 [9]. In S. cerevisiae, this pathway has the MAPKK ScPbs2, which can be activated by three MAPKKKs (ScSsk2, ScSsk22 or ScSte11) (Fig. 1). ScPbs2 activation occurs through two separate osmo-sensing pathways, with signalling through the histidine kinases ScSln1, ScYpd1 and ScSsk1 in one pathway leading to ScSsk2 and ScSsk22 activation, and signalling via ScSho1 in the other pathway resulting in activation of ScSte11 [13, 14, 29–31]. ScSln1 and ScYpd1 are negative regulators of the osmotic stress pathway, and, consequently, Scsln1Δ and Scypd1Δ mutations lead to over activation of the pathway and cell death [30, 31]. ScHog1p activity is also negatively regulated by the action of the protein-tyrosine phosphatases ScPtp2 and ScPtp3 and the Ser/Thr phosphatase ScPtc1 [32, 33]. In C. albicans, this pathway signals a single MAPKKK, CaSsk2, and the MAPKK, CaPbs2 [12, 26, 34, 35]. In both species, activation of Pbs2 results in phosphorylation of Hog1, which translocates to the nucleus [35–37]. Hog1 homologs have also been identified in the filamentous fungi M. grisea (MgOsm1), N. crassa (NcOs-2), Colletotrichum lagenarium (ClOsc1), Botrytis cinerea (BcSak1), A. nidulans (AnHogA), Cochliobolus heterostrophus (BmHog1) and Fusarium species [13, 38–44].

The transcription factors Yap1 and Cap1

The S. cerevisiae bZip transcription factor ScYap1 and its C. albicans homolog CaCap1 are also involved in oxidative stress response (Fig. 1). These transcription factors are translocated to the nucleus during oxidative stress [16, 45]. Further evidence for their role in protection from oxidative stress has come from observations that mutants lacking Cacap1 are more sensitive to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [46] and that CaCAP1 expression is induced by oxidative stress [23]. Furthermore, CaCap1 and CaHog1 act independently in response to oxidative stress and induce expression of different genes during oxidative stress [23]. Deletion of Cahog1 does not affect nuclear translocation of CaCap1 after oxidative stress and Cacap1Δ mutants exhibit the same level of CaHog1 phosphorylation as the wild-type during oxidative stress [24]. Yeast with deletions of Cacap1 are also more sensitive to low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) than Cahog1Δ, while a Cahog1Δ/cap1Δ double deletion had sensitivity comparable to that of the single Cacap1 deletion at low ROS levels [23]. Thus, CaCap1 is required for cell survival under conditions of both low and high levels of oxidative stress, whereas CaHog1 activation only occurs at high levels of oxidative stress. ScYap1 homologs have also been identified in other fungi, including the filamentous plant pathogens such as Magnaporthe oryzae (MoAp1), B. cinerea (BcBap1) and C. heterostrophus (CHAP1) where they are also involved in response to oxidative stress. In M. oryzae, MoAp1 also has a role in pathogenesis [47–49]. However, the potential role of these transcription factors in enhancing tolerance to antifungal molecules has not been reported and; hence, they will not be discussed further in this review.

Cell wall stress response

The cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway

The CWI pathway is involved in sensing cell wall stress and inducing changes to cell wall biogenesis, β-glucan synthesis and the organisation of the actin cytoskeleton [20]. This pathway is responsible for maintenance of an osmotically stable cell wall, as well as cell integrity during cell growth, and is activated in response to oxidative stress, changes in osmotic pressure, cell wall damage, ER stress and alteration of growth temperature [16, 19, 20, 50]. The function of the CWI pathway has been described in most detail for S. cerevisiae, but it also operates in other fungal species such as C. albicans (CaMkc1), Aspergillus fumigatus (AfMpkA), C. neoformans (CnMpk1), B. cinerea (BcBmp3), F. graminearum (FgMgv1) and M. grisea (MgMps1) [50–55]. In S. cerevisiae and C. albicans the CWI MAPK cascade involves activation of the MAPKKK Bck1, the MAPKKs Mkk1 and Mkk2 (only Mkk1 in C. albicans) and the MAPK Mpk1\Slt2 (known as Mkc1 in C. albicans) (Fig. 1). Regulation of this pathway is dependent on the kinase Pkc1, which is upstream of the Bck1 MAPKKK [12, 50, 56, 57]. In S. cerevisiae, targets of phosphorylated ScMpk1/Slt2 include the transcription factors ScRlm1 and ScSBF [also known as the SCB (Swi4, Swi6-dependent cell cycle box) binding factor] [58–60]. ScRlm1 is responsible for most of the transcriptional changes in the cell that occur after activation of the CWI pathway and causes induction of genes involved mainly in cell wall biogenesis [56, 61]. ScSBF is a protein complex which normally regulates transcription at G1 phase of the cell cycle. ScSBF consists of two components, ScSwi4 and ScSwi6. The ScSwi4 component binds SCB sequences in cell cycle specific promoters and ScSwi6 regulates this binding by removing ScSwi4 auto-inhibition. Independent of its cell cycle function, ScSBF is also involved in transcription during cell stress. Under stress conditions, ScMpk1/Slt2 forms a complex with ScSwi4 and can bind to promoters of cell wall stress related genes independently of ScSwi6 [20, 59].

Calcineurin signalling

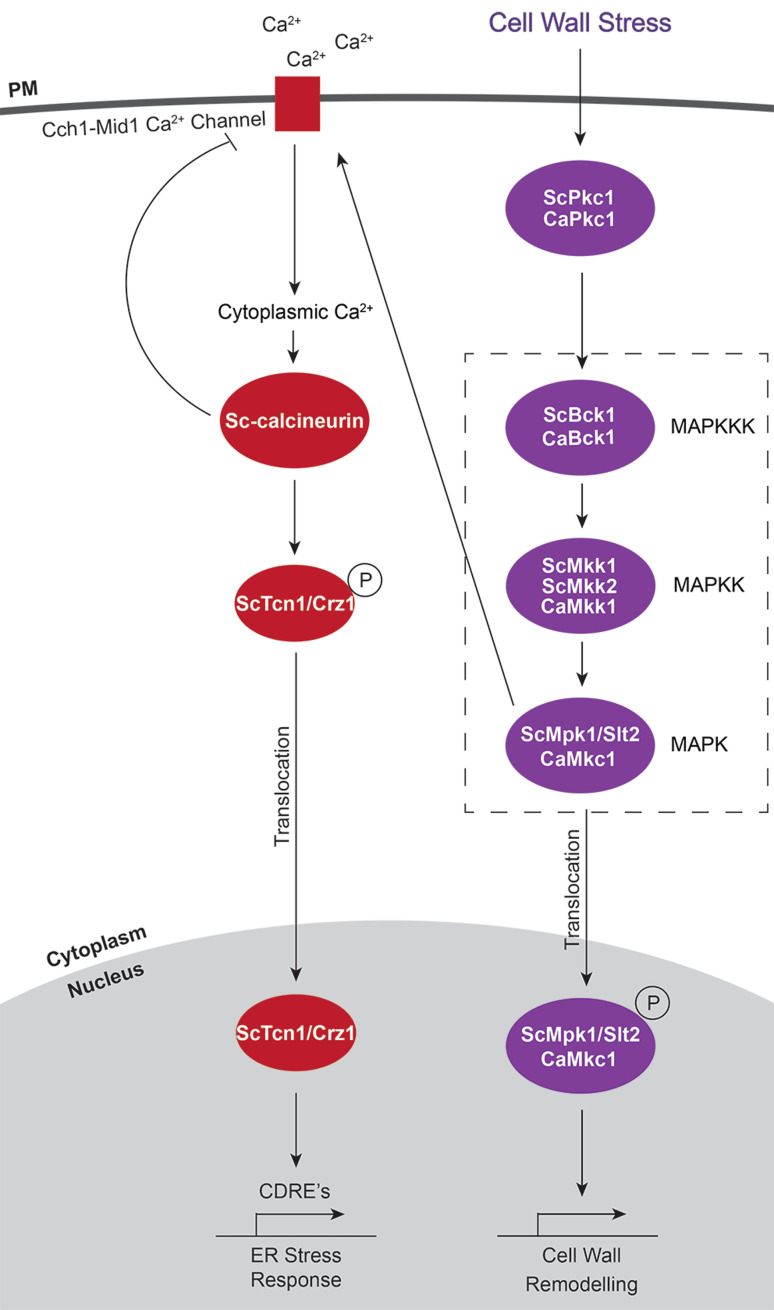

The protein phosphatase calcineurin is activated by many of the stresses that activate CWI signalling, including ER stress, heat shock and hypo-osmotic shock [20]. Calcineurin is also essential for survival in S. cerevisiae mutants with cell wall defects (such as Scmpk1/slt2Δ and Scpkc1Δ) [62]. Together, this indicates a role for Sc-calcineurin in survival after cell wall stress. However, the interaction between the CWI pathway and calcineurin are not fully understood. Under certain stress conditions, the pathways appear to be linked and on other occasions they may be activated independently. For example, during ER stress Sc-calcineurin activation requires phosphorylated ScMpk1/Slt2, the terminal MAPK of the CWI pathway [63]. In other cases, such as during heat-shock, the CWI pathway is not required for activation of Sc-calcineurin [64].

The first step of Sc-calcineurin activation requires an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels. This occurs during stress when the ScCch1-Mid1 Ca2+ channel in the plasma membrane is activated, causing an influx of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm and subsequent activation of Sc-calcineurin [65]. Sc-calcineurin in turn regulates the activity of the ScCch1-Mid1 Ca2+ channel though feedback inhibition [66]. Sc-calcineurin activates genes with calcineurin-dependent response elements (CDREs) via the transcription factor ScTcn1/Crz1 (Fig. 2). Activation of the transcription factor requires Sc-calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation of ScTcn1/Crz1 which then translocates to the nucleus and induces gene expression (Fig. 2) [65, 67, 68]. These genes include those encoding integral membrane proteins, plasma membrane and minor cell wall components, as well as proteins involved in trafficking, lipid synthesis and protein degradation [65].

Fig. 2.

Calcineurin signalling. Activation of the calcium channel Cch1-Mid1 in response to ER stress requires ScMpk1p/Slt2p, which is phosphorylated after activation of the cell wall integrity stress pathway. Activation of the calcium channel results in an increase in intracellular calcium which in turn leads to activation of Sc-calcineurin and dephosphorylation of the transcription factor ScTcn1/Crz1. The transcription factor translocates to the nucleus and induces expression of genes which contain calcineurin-dependent response elements (CDREs)

Other downstream effects of calcineurin include inactivation of a vacuolar H+/Ca2+ exchanger (ScVcx1) and cell cycle arrest through activation of the kinase ScSwe1 [69, 70]. ScSwe1 activation requires cooperative action of both calcineurin and the CWI pathway [70]. Sc-calcineurin is stabilised by the action of S. cerevisiae Hsp90 homologs. Thus, S. cerevisiae deficient in Hsp90 exhibit a decrease in the stability, as well as decreased activation, of Sc-calcineurin [71]. The role of Hsp90 in calcineurin activation has also been demonstrated in C. albicans [72]. The role of calcineurin in maintenance of CWI has been described for C. albicans, C. neoformans and M. oryzae [52, 73, 74]. In C. albicans, CWI and calcineurin pathways are required for stress-induced chitin synthesis. Chitin synthesis in response to cell wall perturbing agents involves the HOG pathway in this pathogen [73].

The role of stress pathways in tolerance to fungicides and antifungal proteins

There are increasing reports about the role of the CWI and HOG pathways in protection of fungi against the damaging effects of chemical fungicides and antifungal proteins. Genetic deletions that inactivate the pathway generally render the fungi more susceptible to growth inhibition or death by the fungicides and AFPs. Conversely, in wild-type fungi the pathways are activated after exposure to these compounds and in some cases activation provides adequate modulation of cellular processes to allow the fungus to survive. Identification of the stress responses that are activated by antimicrobial molecules provides insight into their mechanism of action. For example, if the Hog1 pathway is activated by a particular antifungal molecule it is likely the molecule causes oxidative and/or osmotic stress. In the same vein, if the CWI pathway is activated, the molecule probably damages the cell wall, although it could also be causing oxidative or osmotic stress. Although identifying which stress response pathways are activated will provide insight into how antifungal molecules are damaging cells, further work needs to be undertaken to identify the primary target of these molecules that trigger these responses. Understanding the mechanisms of antifungal molecules is not only important from a basic science perspective, but will assist in the selection of molecules for combinatorial therapies.

Stress signalling in response to chemical fungicides

Three major classes of antifungal agents are used in the clinic for treatment of human infections. Molecules from two of these classes, the azoles and the polyenes, target the integrity of the plasma membrane [75]. The third class, the echinocandins, inactivate cell wall biogenesis by inhibiting the enzyme β-1,3-glucan synthase. Beta-glucan is a major component of the fungal cell wall and; hence, a decrease in the level of this component affects cell integrity [76]. These antifungal drugs have major limitations in the clinical setting. Resistance commonly occurs with the azoles, and toxicity is common with polyenes. Echinocandins require intravenous administration and have low efficacy against some pathogens. Even with drugs, such as the echinocandins, for which resistance has not been common, resistant strains are emerging [77–79].

Induction of cell wall stress by chemical fungicides

The cell walls of both yeast and filamentous fungi contain common molecules, such as chitin, glucans, mannans and glycoproteins. These components are cross-linked to maintain cell shape and integrity; factors which are important in protecting the cell from environmental stresses and osmotic pressure [80]. Detection and response to cell wall stress enhances tolerance to several chemical fungicides.

Echinocandins

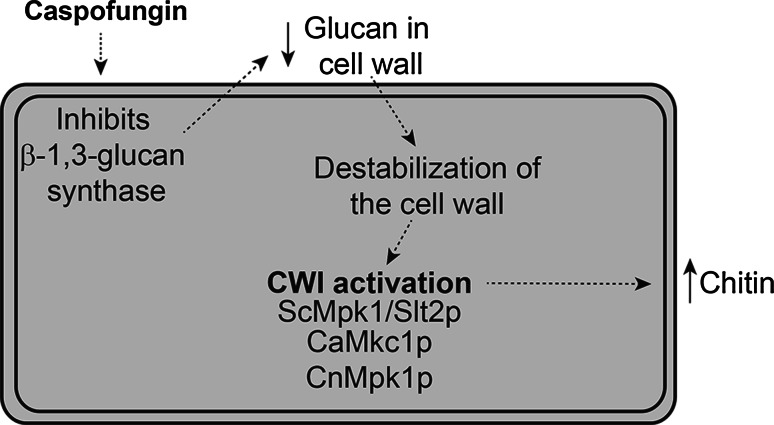

The CWI pathway is activated by the antifungal echinocandin drug caspofungin [81], which targets β-1,3-glucan synthase and, thus, decreases the levels of β-1,3-glucan in the cell wall [76]. Activation of the CWI pathway in response to caspofungin treatment was demonstrated in a microarray analysis of S. cerevisiae, which revealed an up-regulation of ScMPK1/SLT2. In addition, ScMpk1/Slt2 is phosphorylated and activated after caspofungin treatment. Tolerance to caspofungin requires an active ScMpk1/Slt2 kinase, as Scmpk1/slt2 deletions are hypersensitive to caspofungin treatment compared to wild-type [81]. The role of the CWI pathway in enhancing tolerance to caspofungin has been reported for C. albicans and C. neoformans and for another echinocandin drug micafungin in Candida glabrata [21, 52, 82]. Activation of the CWI pathway in response to caspofungin leads to a compensatory increase in chitin which stabilizes the fungal cell wall when β-1,3-glucan levels are diminished [83, 84]. An overview of the involvement of the CWI pathway in caspofungin tolerance is presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The cell wall integrity pathway is activated in response to caspofungin treatment. Caspofungin inhibits β-1,3-glucan synthase, leading to a decrease in β-1,3-glucan in the cell wall and cell wall destabilization. The decrease in β-1,3-glucan activates the CWI pathway in S. cerevisiae, C. albicans and C. neoformans and induces expression of genes to combat the cell wall changes

Calcineurin signalling also enhances tolerance to echinocandin drugs. Ca-calcineurin is required for C. albicans survival after treatment with micafungin. Blocking Ca-calcineurin activity using the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporin A or FK506 decreases tolerance of C. albicans to micafungin [72]. This is supported by the observation that blockage of Hsp90 function destabilises Ca-calcineurin and increases sensitivity to the drugs micafungin and caspofungin [72]. In addition, Ca-calcineurin is required for the up-regulation in chitin biosynthesis that allows C. albicans to survive caspofungin treatment [84].

Furthermore, the CWI pathway and calcineurin signalling may play a role in the paradoxical effect observed after treatment of Candida species with echinocandin drugs. Strains displaying the paradoxical effect have normal susceptibility at lower drug levels, but increased tolerance to echinocandins at higher concentrations [78, 79]. Involvement of the CWI pathway is supported by observations that Camkc1Δ mutants have a diminished paradoxical effect and that transcription of CaMkc1 (CWI pathway) is elevated in C. albicans treated with high but not low concentrations of caspofungin. That is, higher CaMkc1 levels are likely to be responsible for increased caspofungin tolerance at higher drug doses. Interestingly, the paradoxical effect is abolished in the presence of the calcineurin inhibitor, cyclosporine [85].

Nikkomycin Z

Another drug which affects the integrity of the cell wall is nikkomycin Z, a chitin synthase inhibitor [86]. Treatment with Nikkomycin Z results in activation of CnMpk1 in C. neoformans which enhances tolerance to the drug. Conversely, deletion of Cnmpk1 in C. neoformans and C. albicans Camkc1Δ results in enhanced sensitivity to nikkomycin [52, 87].

Ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors

The CWI pathway is activated by exposure of fungi to ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors [88]. Azole drugs, such as fluconazole, act by inhibiting the activity of 14α-demethylase, which is encoded by ERG11. This enzyme catalyses the production of ergosterol which is required for fluidity and integrity of fungal membranes. Inhibition of the enzyme leads to an accumulation of sterol precursors which are toxic to the cell [75]. It has been proposed that a loss of membrane fluidity could lead to disruptions in the interaction between the plasma membrane and the cell wall, affecting cell wall biosynthesis and resulting in cell wall weakness [89, 90]. Thus, activation of the CWI pathway in response to inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis may be due to the loss of membrane fluidity and the associated cell wall weakness. Alternatively, inhibitors of ergosterol biosynthesis may affect the cell wall directly. Fluconazole treatment induces alterations in the cell wall proteome in C. albicans, that include changes in the abundance of proteins involved in CWI [90]. Ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, such as fluconazole, are generally fungistatic, rather than fungicidal. However, fluconazole is fungicidal against S. cerevisiae when signalling through the CWI pathway is blocked by deletion of Scpkc1, supporting the hypothesis that activation of the CWI pathway enhances tolerance to the drug (Fig. 1). Similarly, deletion of Scpkc1 also converts two other ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, fenpropimorph and terbinafine, which target different components of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (ERG2 and ERG1, respectively), from fungicidal to fungistatic molecules.

In another example, deletion of Scbck1 or Scmpk1/slt2 in S. cerevisiae, which encode kinases in the CWI pathway (Fig. 1), also creates hypersensitivity to all three ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors confirming the role of the CWI pathway in enhancing tolerance to this group of drugs. Despite these drugs having similar mechanisms, the downstream fungal response to the drugs differs. That is, fluconazole and fenpropimorph appear to modulate expression of targets of the ScSBF transcription factor. In addition, the transcription factor ScRlm1 may be involved in tolerance to fenpropimorph in the absence of ScSBF, but is not involved in tolerance to fluconazole. For terbinafine, Scswi4 acts independently of ScSBF in tolerance [88].

Calcineurin is also involved in tolerance to ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors. This was demonstrated by monitoring the effect of fluconazole, fenpropimorph and terbinafine on ScTcn1/Crz1 activity, the transcription factor downstream of Sc-calcineurin. Targets of this transcription factor are up-regulated in response to these drugs in S. cerevisiae [88]. In addition, mutants with inactive Sc-calcineurin (deletion of the calcineurin regulatory subunit Sccnb1Δ) display decreased tolerance to these inhibitors. Sc-calcineurin activation in response to all three drugs was dependent on the CWI pathway. That is, the three ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors did not cause activation of Sc-calcineurin in the absence of ScMpk1/Slt2 [88]. However, the mechanism of activation of Sc-calcineurin differs between the drugs. The activation of Sc-calcineurin in response to fluconazole and fenpropimorph appears independent of ScCch1-Mid1 because deletion of Sccch1 or Scmid1 does not alter sensitivity to these drugs [88]. For terbinafine, the ScCch1-Mid1 Ca2+ channel may be required since deletion of channel components (Sccch1Δ and Scmid1Δ) did increase sensitivity [88]. In summary, the S. cerevisiae calcineurin signalling and CWI pathways have different downstream targets that are involved in tolerance to ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors. These differences in signalling may be due to different targets for these drugs in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (ERG11 for fluconazole, ERG1 for terbinafine and ERG2 for fenpropimorph) [75, 91, 92].

The involvement of the CWI pathway in enhancing tolerance to inhibitors of ergosterol biosynthesis has been confirmed in C. albicans. In this organism, mutants of the CWI pathway (Capkc1, Cabck1 and Camkc1) are hypersensitive to fluconazole, fenpropimorph and terbinafine. Furthermore, exposure to the three drugs results in phosphorylation of CaMkc1 (Fig. 1). The CaSBF transcription factor is the likely downstream target of CaMkc1 when the CWI pathway has been activated by the three ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors [88]. Deletion of Caswi4 or Caswi6 causes hypersensitivity, while deletion of Carlm1 has no effect on tolerance. As in S. cerevisiae, inactivation of the CWI pathway through deletion of Capkc1 converted the drugs from fungistatic to fungicidal. However, this fungicidal effect was not obtained with C. albicans Cabck1Δ or Camkc1Δ mutants, suggesting that CaPkc1 may also signal through other downstream targets in response to these drugs [88].

As observed in S. cerevisiae, the ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors fluconazole, fenpropimorph and terbinafine activate calcineurin signalling in C. albicans. However, deletion of Capkc1 does not block Ca-calcineurin activation, indicating the Ca-calcineurin signalling is not dependent on the CWI pathway for activation in C. albicans. The CaCch1-Mid1 channel appears to be important for tolerance to these drugs as deletion of the channel made cells hypersensitive. Thus, it has been proposed that the CWI pathway and calcineurin act in parallel to provide tolerance of C. albicans to fluconazole [88].

Amphotericin B

Another antifungal drug that targets the cell membrane, amphotericin B, activates the CWI pathway in C. albicans [19]. Amphotericin B is a polyene drug naturally found in Streptomyces nodosus which acts through formation of pores and leakage of intracellular contents [93]. Like fluconazole, treatment with amphotericin B results in phosphorylation of CaMkc1 in the CWI pathway [19].

Induction of oxidative and osmotic stress response by chemical fungicides

The Hog1 MAPK is activated in response to several antifungal agents, such as caspofungin, tunicamycin and fludioxonil.

Echinocandins

As described previously, caspofungin targets β-1,3-glucan synthase, reduces β-1,3-glucan in the cell wall [76] and activates the CWI pathway. In addition, the CaHog1 pathway and CaCap1 transcription factor are activated after treatment of C. albicans with this cell wall perturbing drug [94]. It has been reported that the compensatory increase in chitin synthesis that occurs after treatment with caspofungin is induced by the CWI, calcineurin and HOG pathways in C. albicans [84]. However, subsequent research has also revealed induction of oxidative stress related genes in response to caspofungin treatment. That is, phosphorylation of CaHog1 and its translocation to the nucleus, as well as translocation of the CaCap1 transcription factor into the nucleus, in caspofungin treated cells, is consistent with their roles in protecting cells against oxidative stress. This is supported by the observation that pre-treatment of C. albicans with hydrogen peroxide, to prime the cells for oxidative stress, results in increased tolerance of the pathogen to caspofungin [94].

Nikkomycin Z

Contradictory to the finding that CaHog1 activates chitin synthesis [73, 84], C. albicans Cahog1Δ mutants are resistant to the chitin synthesis inhibitor nikkomycin Z when grown at 37 °C [95]. It would be expected that the inability of Cahog1Δ mutants to up-regulate chitin levels would exacerbate sensitivity to nikkomycin Z, rather than provide resistance. There are also no differences in chitin content of the wild-type and Cahog1Δ mutant that could account for the increased resistance [95]. Thus, the HOG pathway has an as yet undetermined role in the sensitivity of yeast to this chitin synthesis inhibitor.

Tunicamycin

Fungal cells rely on ScHog1 to protect themselves from the antifungal drug tunicamycin, which inhibits N-linked glycosylation and causes ER stress. Blockage of Hog1 activity by deletion of Schog1 or Scpbs2, results in enhanced sensitivity to tunicamycin. Conversely, two mutants that display hyper-active ScHog1 pathways (Scptp2Δ and Scptp3ΔI) are resistant to tunicamycin. Signalling in response to tunicamycin depends on the ScSln1 branch of ScPbs2 activation, as Scssk1Δ mutants, but not Scsho1Δ mutants, are sensitive to treatment with this drug (Fig. 1). Tunicamycin treated cells also have higher glycerol levels, supporting activation of the ScHog1 pathway. Interestingly, tunicamycin treatment does not result in an increase in phosphorylation or nuclear translocation of ScHog1, suggesting the response is dependent on the basal activity of ScHog1p and cytosolic functions of the kinase [96].

Tolerance to tunicamycin also involves ScMpk1/Slt2 and Sc-calcineurin, likely due to the ER stress that the molecule induces. Tunicamycin treatment increases ScCch1-Mid1 activity in S. cerevisiae and this Ca2+ channel activity is dependent on ScMpk1 as evidenced by decreased activity of this channel in CWI mutants (Scmpk1/slt2Δ, Scbkc1Δ and Scpkc1Δ). Cells expressing a nonphosphorylatable mutant of ScMpk1 also fail to activate the ScCch1-Mid1 channel in response to tunicamycin [63].

Phenylpyrroles

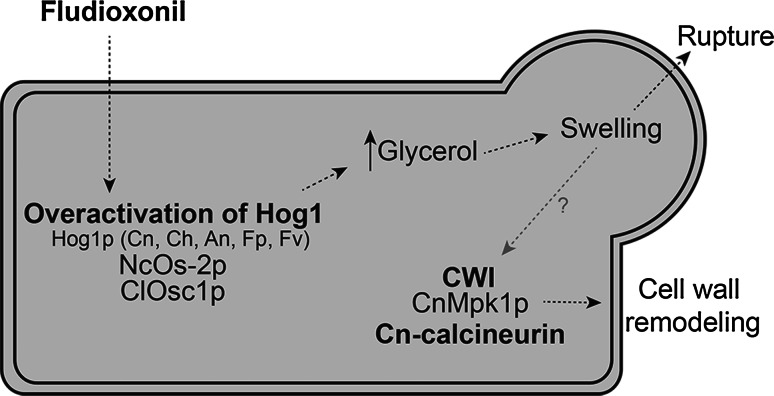

The Hog1 pathway has been implicated in the mechanism of action of phenylpyrrole fungicides (fludioxonil and fenpiclonil) in several filamentous fungal species. The phenylpyrrole fungicides are interesting because they exploit this natural fungal defense mechanism to kill the cells. That is, activation of Hog1 leads to increased sensitivity to these drugs rather than tolerance as described for other drugs in this review. Phenylpyrrole fungicides are derived from the antibiotic pyrrolnitrin, a secondary metabolite of Pseudomonas pyrrocinia [97]. Fludioxonil is used in seed treatments and foliar sprays for prevention of infection by the plant pathogen B. cinerea [97]. Bcsak1, the Hog1 homolog in B. cinerea, is phosphorylated in response to fludioxonil consistent with activation of the Hog1 pathway [40]. Fludioxonil induced activation of Hog1 is not restricted to B. cinerea. Os-2, the N. crassa Hog1 homolog, is also involved in the sensitivity of this fungus to phenylpyrroles, as deletion of Ncos-2 results in enhanced tolerance to fludioxonil and fenpiclonil [39]. Fludioxonil treatment causes wild-type N. crassa conidia and hyphae to swell and rupture, which has led to the hypothesis that over-activation of NcOs-2 by fludioxonil may induce over accumulation of glycerol and increased internal pressure [39]. Indeed, others have reported that glycerol accumulation occurs in response to fludioxonil and fenpiclonil in N. crassa [98]. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that overactivation of ScHog1 through deletion of Scsln1 and Scypd1 leads to cell death. Similarly, a S. cerevisiae mutant with hyperactive a ScHog1 exhibits increased growth inhibition compared to wild-type [31, 99]. The activity of fludioxonil is also mediated by the Hog1-like MAPKs, ClOsc1 and MoOsm1, in the plant pathogens C. lagenarium and M. oryzae, respectively [40, 100]. Closc1Δ mutants have increased tolerance to fludioxonil. Exposure to the fungicide leads to phosphorylation of ClOsc1 and translocation to the nucleus [40]. MoOsm1 is also phosphorylated in response to fludioxonil [100]. Similarly, deletion of Hog1-like MAPKs causes resistance to fludioxonil in the filamentous fungi C. heterostrophus [44], Fusarium proliferatum and Fusarium verticilliodes [43]. The HOG pathway is also required for the transcriptional response to fludioxonil in A. nidulans [42].

Similar to filamentous fungi, activation of the Hog1 pathway in response to phenylpyrrole fungicides also occurs in yeast. For example, the yeast C. neoformans activates CnHog1 in response to fludioxonil treatment. CnHog1 activation in C. neoformans strain H99 differs from other yeast, because CnHog1 is phosphorylated under normal conditions and is activated by dephosphorylation under stress conditions [101]. In this strain, fludioxonil treatment leads to dephosphorylation of CnHog1 and deletion of Cnhog1 and Cnpbs2 results in increased tolerance to the fungicide. Furthermore, fludioxonil induced activation of CnHog1 leads to accumulation of glycerol and morphological defects [102]. Glycerol accumulation in response to fludioxonil has also been observed in C. albicans [103]. Interestingly, S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans strain JEC21, which has typical Hog1 activation, are normally resistant to fludioxonil and do not show any phenotypic change in hog1 knockouts. In addition, no Hog1 phosphorylation is detected after fungicide treatment [102]. An overview of the involvement of the HOG pathway in response to fludioxonil treatment is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The HOG pathway is activated in response to fludioxonil treatment. Treatment of the several filamentous fungi and the yeast C. neoformans with fludioxonil results in overactivation of Hog1 and an increase in cellular glycerol levels. Increased internal pressure puts mechanical stress on the cell wall that can lead to rupture of the cell. The cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway is also activated upon treatment with fludioxonil and leads to reinforcement of the cell wall. Activation of the CWI pathway may be a consequence of the swelling of the cell and associated perturbation of the cell wall

While the HOG pathway is required for sensitivity to fludioxonil, the CWI pathway plays a role in tolerance to this drug in C. neoformans. The C. neoformans CWI pathway mutants (Cnmpk1Δ, Cnbck1Δ and Cnmkk1Δ) are hypersensitive to fludioxonil treatment and treatment with the fungicide in the presence of 1 M sorbitol, as an osmotic stabiliser, partially rescues these mutants [102]. It has been proposed that the CWI pathway is activated by fludioxonil as a result of cell swelling and increased pressure in the cells. Reinforcement of the cell wall may occur in an attempt to prevent cell rupture [102]. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that activation of the CWI pathway occurs in S. cerevisiae in response to increased internal turgor pressure in mutants that are unable to regulate K+ levels [104]. This process may also involve the calcineurin signalling as fludioxonil, which is normally fungistatic against C. neoformans H99, was fungicidal in Cn-calcineurin mutants [102].

Dicarboximides

As observed with the phenylpyrroles, the dicarboximide fungicide iprodione induces activation of Hog1 which results in increased sensitivity to the fungicide rather than tolerance. This is supported by the observation that deletion of Bcsak1, the Hog1 homolog in B. cinerea, renders the fungus more resistant to this class of fungicides [41]. Likewise, deletion of the Hog1 homolog in C. heterostrophus (Bmhog1Δ) or C. lagenarium (Scosc1Δ) causes resistance to iprodione treatment [40, 44]. Phosphorylation of B. cinerea BcSak1 after treatment with iprodione confirmed that the Hog1 pathway is activated by this fungicide [41].

Fluconazole and amphotericin B

As described previously, the CWI pathway plays a large role in tolerance of fungi to fluconazole. The CaCap1/ScYap1 transcription factor (Fig. 1) is also involved in resistance to this drug. Thus, Cap1 overexpression in S. cerevisiae leads to tolerance to fluconazole treatment [105]. In addition, ScYap1 or expressed Cap1 bring about fluconazole resistance through activation of ScFLR1 (Fluconazole Resistance 1) in S. cerevisiae. Thus, mutants lacking Scflr1 are not resistant to fluconazole [105]. ScFLR1 is homologous to the C. albicans MDR1 efflux pump [46]. CaMDR1 expression can be induced by hydrogen peroxide exposure and this increase in expression is not observed in Cacap1Δ mutants [106]. Constitutive expression of CaMdr1 in C. albicans leads to fluconazole resistance, as does increased CaMdr1 expression induced by a hyperactive truncated form of CaCap1 [46, 106].

Although there is no evidence that fluconazole and amphotericin B activate the HOG pathway, modulation of this pathway can change the tolerance of C. neoformans to these drugs. In C. neoformans H99, Cnhog1 deletion results in increased ergosterol biosynthesis, increased levels of ergosterol in the membrane and increased resistance to fluconazole. Conversely, increases in ergosterol levels increases sensitivity to amphotericin B [107]. This effect may be species specific as C. albicans Cahog1Δ mutants do not have altered sensitivities to these drugs [95].

A summary of stress signalling in response to antifungal agents is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of antifungal agents that stimulate stress signalling

| Agent | Drug Family/Function | MAPKs Involved | Pathway | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caspofungin | Echinocandin |

ScMpk1/Slt2 CaMkc1 CnMpkl Ca-calcineurin CaHogl CaCapl |

CWI Calcineurin HOG Cap1 oxidative stress |

Reinoso-Martín et al. [81] Blankenship et al. [21] Kraus et al. [52] Singh et al. [72] Kelly et al. [94] |

| Micafungin | Echinocandin |

CgSlt2 Ca-calcineurin |

CWI Calcineurin |

Miyazaki et al. [82] Singh et al. [72] |

| Nikkomycin Z | Chitin synthase inhibitor |

CnMpkl CaMkc1 CaHogl |

CWI HOG |

Kraus et al. [52] Navarro-García et al. [87] Alonso-Monge et al. [95] |

| Fluconazole | Ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitor |

ScMpkl CaMkc1 CaCapl Sc-calcineurin Ca-calcineurin CnHogl |

CWI Cap1 oxidative stress Calcineurin HOG |

LaFayette et al. [88] Alarco et al. [105] Ko et al. [107] |

| Fenpropimorph | Ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitor |

ScMpkl CaMkd Sc-calcineurin Ca-calcineurin |

CWI Calcineurin |

LaFayette et al. [88] |

| Terbinafine | Ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitor |

ScMpkl CaMkc1 Sc-calcineurin Ca-calcineurin |

CWI Calcineurin |

LaFayette et al. [88] |

| Amphotericin B | Polyene |

CaMkc1 CnHogl |

CWI HOG |

Navarro-García et al. [19] Ko et al. [107] |

| Fludioxonil | Phenylpyrrole |

CnMpkl CnHogl Cn-calcineurin NcOs-2 ClOsc1 BmHogl AnHogA FpHogl FvHogl MoOsml BcSakl |

CWI HOG Calcineurin |

Kojima et al. [102] Zhang et al. [39] Kojima et al. [40] Yoshimi et al. [44] Hagiwara et al. [42] Nagygyörgy et al. [43] Motoyama et al. [100] |

| Tunicamycin | N-linked glycosylation inhibitor |

ScHogl Sc-calcineurin |

HOG Calcineurin |

Torres-Quiroz et al. [96] Bonilla et al. [63] |

| Fenpiclonil | Phenylpyrrole | NcOs-2 | HOG | Zhang et al. [39] |

| Iprodione | Dicarboximide |

BmHogl ClOsc1 BcSakl |

HOG |

Yoshimi et al. [44] Kojima et al. [40] Segmüller et al. [41] |

A list of MAPKs and stress signalling pathways required in fungal tolerance to chemical fungicides. The nomenclature of the MAPKs varies between organisms

Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Ca, Candida albicans; Cg, Candida glabrata; Cn, Cryptococcus neoformans; Nc, Neurospora crassa; Cl, Colletotrichum lagenarium; Bm, Cochliobolus heterostrophus; An, Aspergillus nidulans; Fp, Fusarium proliferatum; Fv, Fusarium verticilliodes; Mo, Magnaporthe oryzae; Bc, Botrytis cinerea

Stress signalling in response to antifungal peptides

Antifungal peptides are expressed by many forms of life. They are a crucial component of innate immune systems that provide a first, and often only, line of defense against fungal pathogens. These proteins have evolved to specifically eliminate competing fungi from environments where other cells are also present. This has led several groups to investigate their potential application in control of fungal pathogens in agriculture and clinical settings since their activities are often specific to fungi, minimizing toxicity to the host. Clinical isolates that are resistant to the established chemical fungicides mentioned in the previous section are often sensitive to AFPs, furthering the interest surrounding the application of AFPs from natural sources in control of fungal pathogens. Although the same stress response pathways are activated by AFPs and chemical fungicides, the mechanisms of fungal cell damage differ significantly. The mechanism of action for most AFPs remains to be elucidated [6] and so far involvement of stress pathways in protection of cells from the toxic effects of AFPs has only been investigated for a handful of plant defensins, a fungal peptide, as well as the human peptides, histatin 5 and β-defensin 2.

Cell wall stress response to antifungal peptides

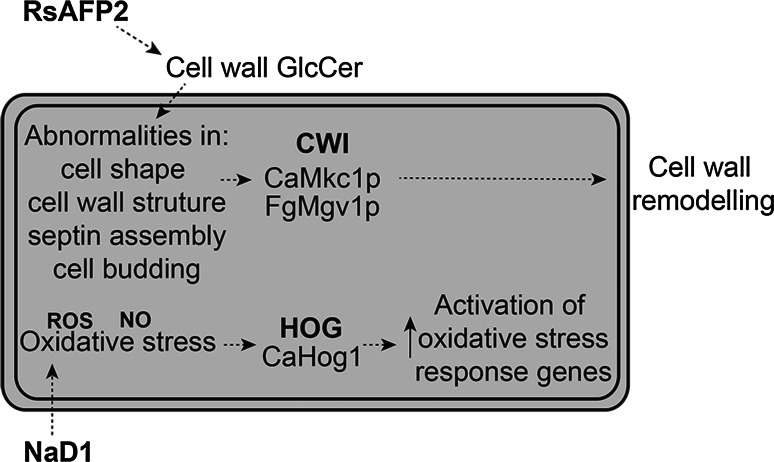

Tolerance to the plant defensin RsAFP2 (from radish) involves the CWI pathway in C. albicans [108]. RsAFP2 interacts with glucosylceramides (GlcCer) in the fungal cell wall and causes abnormalities in cell shape, cell wall structure, cell budding and septin formation [108, 109]. Treatment of C. albicans with RsAFP2 results in phosphorylation of the CaMkc1 MAPK (Fig. 1) [108]. Tolerance to related defensins DmAMP1 (from Dahlia merckii) and Pn-AMP1 (from Pharbitis nil) also depends on the CWI pathway. Mutants lacking the CaMkc1 MAPK (Camkc1Δ) are more sensitive to DmAMP1 and mutants lacking CaBck1 (Cabck1Δ) are hypersensitive to Pn-AMP1 [110, 111]. This phenomenon is not restricted to yeast. The CaMkc1 homolog (FgMgv1) has been implicated in protection of the filamentous plant pathogen, F. graminearum, from the toxic effects of the plant defensins RsAFP2 (radish), MsDef1 (alfalfa) and MtDef2 (Medicago trancatula) [112]. As well as activating the CWI pathway, these defensins induce signalling through the F. graminearum FgGpmk1 pathway, which is homologous to the ScFus3 mating response pathway in S. cerevisiae [112, 113]. Deletion of F. graminearum Fgste11, a MAPKKK which phosphorylates FgGpmk1, resulted in hypersensitivity to MsDef1. Therefore, this pathway, when functional, is able to protect F. graminearum from the toxic effects of MsDef1 [112]. The role of the CWI and mating pathways in protection of cells was verified by deletion of Fggpmk1 and Fgmgv1. These mutants were hypersensitive to RsAFP2, MsDef1 and MtDef2. Interestingly, the FgHog1 pathway was not involved in the response to these three plant defensins, as deletion of the F. graminearum Fghog1 homolog did not alter sensitivity to any of the three defensins [112]. An overview of the action of RsAFP2 and the involvement of the CWI pathway is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The CWI pathway is activated by the plant defensin RsAFP2, whereas the Hog1 pathway is activated by the plant defensin NaD1. RsAFP2 interacts with GlcCer in the fungal cell wall causing abnormalities in cell shape, cell wall structure, septin assembly and cell budding. These changes to the cell wall cause activation of the CWI pathway [108]. In contrast, NaD1 enters C. albicans cells and induces production of reactive oxygen species. The cell activates the CaHog1 pathway in response to this oxidative stress [111]

Another peptide which induces CWI signalling is the Aspergillus giganteus peptide AFP. This peptide inhibits chitin synthesis and causes activation of the CWI pathway in Aspergillus niger. Activation of the CWI pathway was established by monitoring expression of the α-1,3-glucan synthase gene, a gene up-regulated by many cell wall affecting drugs, in A. niger [114]. A screen of S. cerevisiae deletion mutants revealed that Scmpk1Δ was slightly more sensitive to AFP than the wild-type. However, mutants with deficient Sc-calcineurin signalling (deletion of the ScCch1-Mid1 channel or the transcription factor ScCrz1) were much more sensitive to the effects of AFP. Chitin synthase genes we also more highly expressed in AFP treated cells, and this increase was dependent on functional Sc-calcineurin signalling. Thus, the primary mode of tolerance to AFP is activation of Sc-calcineurin, which increases expression of chitin synthase genes [115].

Induction of oxidative and osmotic stress by antifungal peptides

The CaHog1 pathway is activated in C. albicans by two human antifungal peptides, histatin 5 and human β-defensin 2 (hβD2). Inactivation of the CaHog1 pathway renders cells more sensitive to these antifungal peptides. That is, C. albicans Cahog1 and Capbs2 deletion mutants are hypersensitive to human β-defensin 2 and Cahog1 knockouts are hypersensitive to histatin 5 [116, 117]. In wild-type C. albicans, treatment with histatin 5 leads to phosphorylation of CaHog1 and histatin 5 treatment induces genes required for the osmotic stress response and a consequent increase in intracellular glycerol levels [116]. To confirm that osmotic stress is responsible for cell death, cells were pre-treated with sorbitol to prime the cells for an adaptive response to osmotic stress. The sorbitol pre-treated cells were less sensitive to histatin 5 treatment. Furthermore, when histatin 5 was added simultaneously with sorbitol, the cells were hypersensitive suggesting that the combined osmotic stress overwhelmed the cells. However, when low concentrations of histatin 5 were added simultaneously with hydrogen peroxide, a molecule that creates oxidative stress, sensitivity was not altered. Interestingly, Cacap1Δ mutants were sensitive to histatin 5 treatment, but only at high histatin 5 concentrations. This led to the hypothesis that CaHog1 activation in response to low levels of histatin 5 results from osmotic stress, and that production of reactive oxygen species is a secondary effect of histatin 5 treatment at high concentrations (>32 μM) [116]. The CWI pathway is not involved in response to histatin 5, as C. albicans with an Camkc1 deletion had no change in tolerance [116].

In contrast to the plant defensins RsAFP2, MsDef1 and MtDef2 mentioned previously, the plant defensin NaD1 activates the CaHog1 pathway in treated cells [111]. NaD1 acts via a three step mechanism involving binding to the fungal cell wall, movement through the plasma membrane and entry into the cytoplasm [118]. It has been hypothesised that NaD1 binds intracellular target(s), leading to cell death. Activation of the CaHog1 pathway is required for C. albicans survival following treatment with low concentrations of NaD1 [111]. This was revealed when C. albicans Cahog1 and Capbs2 deletion mutants (Fig. 1) were found to be hypersensitive to NaD1 and the observations that CaHog1 is phosphorylated in wild-type C. albicans in response to NaD1 treatment. Activation of CaHog1 by NaD1 is initiated by oxidative rather than osmotic stress, since cells treated with NaD1 and sorbitol simultaneously were not altered in their sensitivity to NaD1. Production of ROS occurs during NaD1 treatment and reducing the levels of NaD1-induced ROS by co-treatment with the antioxidant ascorbate reduces the activity of NaD1. CaHog1 activation in response to oxidative stress is consistent with the production of ROS upon treatment of cells with NaD1 [111]. The CWI pathway and CaCap1 transcription factor are not involved in response to NaD1, as Camkc1 and Cacap1 deletion mutants did not have altered sensitivity relative to wild-type cells [111]. An overview of the action of NaD1 and the involvement of the HOG pathway is shown in Fig. 5.

As mentioned previously, CWI mutants in C. albicans are sensitive to the plant defensin DmAMP1, but tolerance to DmAMP1 also involves the CaHog1 pathway since mutants in this pathway (Cahog1Δ and Capbs2Δ) are hypersensitive to DmAMP1 treatment [111].

Interestingly, deletion of Captc1, which causes overactivation of the CaHog1 pathway, results in resistance of C. albicans to the plant defensin HsAFP1 (from Heuchera sanguinea) [119]. This indicates that CaHog1 functions in sensitivity to this antifungal peptide. This peptide may be working in a similar mechanism to fludioxonil, in which CaHog1 induced glycerol accumulation contributes to cell death.

A summary of stress signalling in response to antifungal peptides is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of stress signalling in response to antifungal peptides

| Peptide | Peptide Family | MAPKs Involved | Pathway | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RsAFP2 | Plant defensin |

CaMkcl FgMgvl FgGpmkl |

CWI Mating |

Thevissen et al. [108] Ramamoorthy et al. [112] |

| MsDef1 | Plant defensin |

FgMgvl FgGpmkl |

CWI Mating |

Ramamoorthy et al. [112] |

| MtDef2 | Plant defensin |

FgMgvl FgGpmkl |

CWI Mating |

Ramamoorthy et al. [112] |

| Pn-AMP1 | Plant defensin | CaMkcl | CWI | Koo et al. [110] |

| AFP | Fungal peptide |

ScMpkl Sc-calcineurin |

CWI Calcineurin |

Ouedraogo et al. [115] |

| Histatin 5 | Salivary histatin |

CaHogl CaCapl |

HOG Cap1 oxidative stress |

Vylkova et al. [116] |

| hβD2 | Human β-defensin | CaHogl | HOG | Argimon et al. [117] |

| HsAFPI | Plant defensin | CaHogl | HOG | Aerts et al. [119] |

| NaD1 | Plant defensin | CaHogl | HOG | Hayes et al. [111] |

| DmAMPI | Plant defensin |

CaHogl CaMkcl |

HOG CWI |

Hayes et al. [111] |

A list of MAPKs and stress signalling pathways required in fungal tolerance to antifungal peptides. The nomenclature of the MAPKs varies between organisms

Ca, Candida albicans; Fg, Fusarium graminearum; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Conclusions

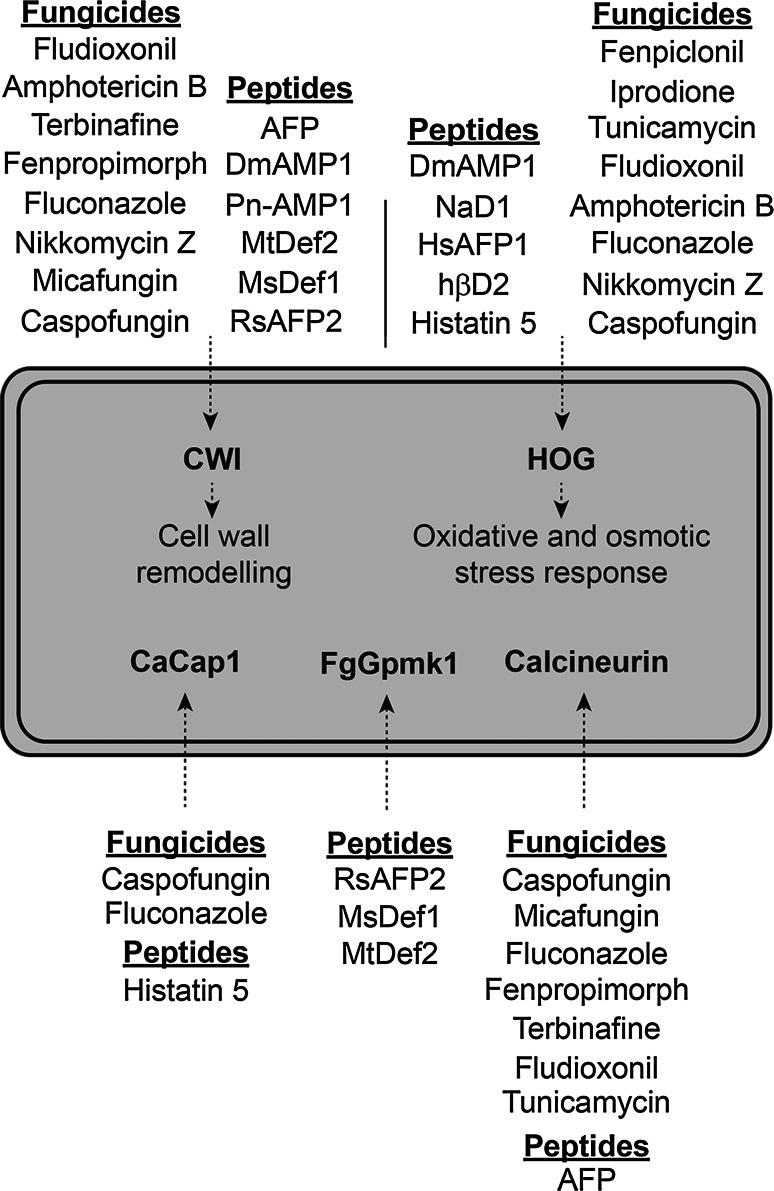

Stress signalling pathways enhance tolerance of both filamentous fungi and yeast to chemical fungicides and antimicrobial peptides. An overview of stress response pathways implicated in response to fungicide and antifungal peptide treatments is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Stress response pathways involved in response to fungicides and AFPs. The CWI pathway, HOG pathway, F. graminearum Gpmk1 mating response pathway, the CaCap1 transcription factor and calcineurin are activated to different extents by various fungicides and antifungal peptides

The activation of MAPK stress response pathways helps the fungal cells to survive when challenged by these antifungal agents. For this reason, targeting and impairment of MAPK pathways is a potential avenue for combating fungal resistance and improving efficacy of antifungal molecules. Inhibitors of kinases within MAPK pathways have already been reported to improve the activity of antifungal agents. For example, cercosporamide, a CWI Pkc1 inhibitor, increases the antifungal activity of both echinocandin and azole drugs [88, 120]. In another example, inhibition of the calcineurin with the inhibitor FK506 has a synergistic effect in combination with the antifungal agents fludioxonil, caspofungin and fluconazole (all of which activate the calcineurin to some extent) against C. neoformans [102, 121] and with azole drugs against several Candida species [122]. There is also evidence that simultaneous activation of multiple MAPK pathways may have an inhibitory effect on pathway activation. For example, when pheromone, which stimulates the ScFus3 pathway, and sorbitol, which stimulates the ScHog1 pathway, are used in combination then either ScFus3 was activated or ScHog1was activated, but never both. The ScFus3 and ScHog1 pathways share the MAPKKK ScSte11. Thus, these pathways have developed a switch-like mechanism to prevent simultaneous activation of both pathways by this shared MAPKKK. After activation of one of the pathways, a higher degree of stimulation of the opposing pathway is required to make the ‘switch’ and direct signalling away from the first pathway and instead allow signalling through the second pathway [123]. This observation may prove useful in designing combinatorial treatments. For example, if two fungicides or antifungal peptides which activate different pathways were selected, perhaps the second signalling pathway could not be activated, resulting in increased sensitivity to the fungicide which normally activates that pathway. However, there is no evidence that this outcome is possible with co-stimulation of other combinations of MAPK pathways, such as HOG and the CWI pathway or CWI and mating pathways (ScFus3). A shared upstream component, such as the MAPKKK ScSte11, may be required for this situation to occur.

Applications of MAPK inhibitors in treatment of human fungal disease may be limited due to the high similarity of yeast and human MAP kinases. Specific inhibitors of calcineurin signalling may have more potential, at least for filamentous fungi, since a serine-proline rich region has been identified in A. fumigatus that is unique to filamentous fungi and is absent in human calcineurin [124].

Knowledge of MAPK pathways triggered by antifungal peptides may also give insight into the mechanism of action of antifungal drugs and provide a new approach to narrow down the search for possible targets of these agents.

In summary, fungal pathogens have a serious impact on agricultural production and human health. Many of the chemical fungicides currently used for the control of fungal pathogens are not sustainable due to problems associated with toxicity, efficacy and fungal resistance. This opens the opportunity to develop antifungal peptides for implementation in fungal control because they have diverse mechanisms of action and can be used in combination with each other and/or chemical fungicides for more sustainable management of disease. Understanding the mechanisms of action of chemical fungicides and AFPs is, thus, crucial for the design and implementation of novel antifungal therapies. There is also a need to understand the role stress response pathways play in enhancing tolerance and how this can be circumvented. As the field of antifungal therapies progresses, the study of the fungal stress responses will continue to be central in our understanding of fungal pathogens and how we can minimize their effects on society.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Discovery Project from the Australian Research Council (ARC, DP120102694). B. H. was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award. Work in the A.T. lab on C. albicans is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and the Monash University Researcher Accelerator (MRA) Grant.

Footnotes

N. L. van der Weerden and M. R. Bleackley contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Nicole L. van der Weerden, Email: N.VanDerWeerden@latrobe.edu.au

Mark R. Bleackley, Email: M.Bleackley@latrobe.edu.au

References

- 1.Jenssen H, Hamill P, Hancock RE. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):491–511. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock REW, Lehrer R. Cationic peptides: a new source of antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16(2):82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415(6870):389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oren Z, Shai Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Pept Sci. 1998;47(6):451–463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<451::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolas P. Multifunctional host defense peptides: intracellular-targeting antimicrobial peptides. FEBS J. 2009;276(22):6483–6496. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weerden NL, Bleackley MR, Anderson MA. Properties and mechanisms of action of naturally occurring antifungal peptides. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(19):3545–3570. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theis T, Stahl U. Antifungal proteins: targets, mechanisms and prospective applications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(4):437–455. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3231-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cudic M, Otvos L., Jr Intracellular targets of antibacterial peptides. Curr Drug Targets. 2002;3(2):101–106. doi: 10.2174/1389450024605445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikolaou E, Agrafioti I, Stumpf M, Quinn J, Stansfield I, Brown A. Phylogenetic diversity of stress signalling pathways in fungi. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9(1):44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith DA, Morgan BA, Quinn J. Stress signalling to fungal stress-activated protein kinase pathways. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;306(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso-Monge R, Román E, Arana DM, Pla J, Nombela C. Fungi sensing environmental stress. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:17–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monge RA, Román E, Nombela C, Pla J. The MAP kinase signal transduction network in Candida albicans . Microbiol. 2006;152(4):905–912. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J-R. MAP kinases in fungal pathogens. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;31(3):137–152. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustin M, Albertyn J, Alexander M, Davenport K. MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(4):1264–1300. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1264-1300.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst JF, Pla J. Signaling the glycoshield: maintenance of the Candida albicans cell wall. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301(5):378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikner A, Shiozaki K. Yeast signalling pathways in the oxidative stress response. Mutat Res. 2005;569(1–2):13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrero de Dios C, Roman E, Alonso Monge R, Pla J. The role of MAPK signal transduction pathways in the response to oxidative stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: implications in virulence. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2010;11(8):693–703. doi: 10.2174/138920310794557655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito H, Posas F. Response to hyperosmotic stress. Genetics. 2012;192(2):289–318. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.140863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarro-García F, Eisman B, Fiuza SM, Nombela C, Pla J. The MAP kinase Mkc1p is activated under different stress conditions in Candida albicans . Microbiol. 2005;151(8):2737–2749. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin DE. Regulation of cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the cell wall integrity signaling pathway. Genetics. 2011;189(4):1145–1175. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.128264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blankenship JR, Fanning S, Hamaker JJ, Mitchell AP. An extensive circuitry for cell wall regulation in Candida albicans . PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(2):e1000752. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirooka T, Ishii H. Chemical control of plant diseases. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2013;79(6):390–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enjalbert B, Smith DA, Cornell MJ, Alam I, Nicholls S, Brown AJP, Quinn J. Role of Hog-1 stress-activated protein kinase in the global transcriptional response to stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans . Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1018–1032. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alonso-Monge R, Navarro-García F, Román E, Negredo AI, Eisman B, Nombela C, Pla J. The Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase is essential in the oxidative stress response and chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans . Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2(2):351–361. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.2.351-361.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San José C, Monge RA, Pérez-Díaz R, Pla J, Nombela C. The mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog HOG1 gene controls glycerol accumulation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans . J Bacteriol. 1996;178(19):5850–5852. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5850-5852.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheetham J, Smith DA, da Silva Dantas A, Doris KS, Patterson MJ, Bruce CR, Quinn J. A single MAPKKK regulates the Hog1 MAPK pathway in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans . Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(11):4603–4614. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas E, Roman E, Claypool S, Manzoor N, Pla J, Panwar SL. Mitochondria influences CDR1 efflux pump activity, Hog1-mediated oxidative stress pathway, iron homeostasis and ergosterol levels in Candida albicans . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(11):5580–5599. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00889-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montañés FM, Pascual-Ahuir A, Proft M. Repression of ergosterol biosynthesis is essential for stress resistance and is mediated by the Hog1 MAP kinase and the Mot3 and Rox1 transcription factors. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79(4):1008–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda T, Takekawa M, Saito H. Activation of yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science. 1995;269(5223):554–558. doi: 10.1126/science.7624781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda T, Wurgler-Murphy S, Saito H. A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:242–245. doi: 10.1038/369242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Posas F, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Maeda T, Witten EA, Thai TC, Saito H. Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the SLN1–YPD1–SSK1 “two-component” osmosensor. Cell. 1996;86(6):865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacoby T, Flanagan H, Faykin A, Seto AG, Mattison C, Ota I. Two protein-tyrosine phosphatases inactivate the osmotic stress response pathway in yeast by targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase, Hog1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(28):17749–17755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warmka J, Hanneman J, Lee J, Amin D, Ota I. Ptc1, a type 2C Ser/Thr phosphatase, inactivates the HOG pathway by dephosphorylating the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(1):51–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.51-60.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arana DM, Nombela C, Alonso-Monge R, Pla J. The Pbs2 MAP kinase kinase is essential for the oxidative-stress response in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans . Microbiol. 2005;151(4):1033–1049. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith DA, Nicholls S, Morgan BA, Brown AJP, Quinn J. A conserved stress-activated protein kinase regulates a core stress response in the human pathogen Candida albicans . Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(9):4179–4190. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrigno P, Posas F, Koepp D, Saito H, Silver PA. Regulated nucleo/cytoplasmic exchange of HOG1 MAPK requires the importin [beta] homologs NMD5 and XPO1. EMBO J. 1998;17(19):5606–5614. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vr Reiser, Ruis H, Ammerer G. Kinase activity-dependent nuclear export opposes stress-induced nuclear accumulation and retention of Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(4):1147–1161. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dixon KP, Jin-Rong X, Smirnoff N, Talbot NJ. Independent signaling pathways regulate cellular turgor during hyperosmotic stress and appressorium-mediated plant infection by Magnaporthe grisea . Plant Cell. 1999;11(10):2045–2058. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.10.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Lamm R, Pillonel C, Lam S, Xu J-R. Osmoregulation and fungicide resistance: the Neurospora crassa os-2 gene encodes a HOG1 mitogen-activated protein kinase homologue. Appli Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(2):532–538. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.532-538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kojima K, Takano Y, Yoshimi A, Tanaka C, Kikuchi T, Okuno T. Fungicide activity through activation of a fungal signalling pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(6):1785–1796. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segmüller N, Ellendorf U, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P. BcSAK1, a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase, is involved in vegetative differentiation and pathogenicity in Botrytis cinerea . Eukary Cell. 2007;6(2):211–221. doi: 10.1128/EC.00153-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hagiwara D, Asano Y, Marui J, Yoshimi A, Mizuno T, Abe K. Transcriptional profiling for Aspergillus nidulans HogA MAPK signaling pathway in response to fludioxonil and osmotic stress. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46(11):868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagygyörgy ED, Hornok L, Ádám AL. Role of MAP kinase signaling in secondary metabolism and adaptation to abiotic/fungicide stress in Fusarium. In: Thajuddin N, editor. Fungicides—beneficial and harmful aspects. Rijeka, Croatia: InTechWeb; 2011. pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshimi A, Kojima K, Takano Y, Tanaka C. Group III histidine kinase is a positive regulator of Hog1-type mitogen-activated protein kinase in filamentous fungi. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4(11):1820–1828. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.11.1820-1828.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, De Micheli M, Coleman ST, Sanglard D, Moye-Rowley WS. Analysis of the oxidative stress regulation of the Candida albicans transcription factor, Cap1p. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(3):618–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alarco A, Raymond M. The bZip transcription factor Cap1p is involved in multidrug resistance and oxidative stress response in Candida albicans . J Bacteriol. 1999;181(3):700–708. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.700-708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Temme N, Tudzynski P. Does Botrytis cinerea ignore H2O2-induced oxidative stress during infection? Characterization of Botrytis activator protein 1. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22(8):987–998. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-8-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo M, Chen Y, Du Y, Dong Y, Guo W, Zhai S, Zhang H, Dong S, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Wang P, Zheng X. The bZIP transcription factor MoAP1 mediates the oxidative stress response and is critical for pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(2):e1001302. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lev S, Hadar R, Amedeo P, Baker SE, Yoder OC, Horwitz BA. Activation of an AP1-like transcription factor of the maize pathogen Cochliobolus heterostrophus in response to oxidative stress and plant signals. Eukary Cell. 2005;4(2):443–454. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.443-454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Navarro-García F, Sánchez M, Pla J, Nombela C. Functional characterization of the MKC1 gene of Candida albicans, which encodes a mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog related to cell integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(4):2197–2206. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valiante V, Heinekamp T, Jain R, Härtl A, Brakhage AA. The mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkA of Aspergillus fumigatus regulates cell wall signaling and oxidative stress response. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45(5):618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraus PR, Fox DS, Cox GM, Heitman J. The Cryptococcus neoformans MAP kinase Mpk1 regulates cell integrity in response to antifungal drugs and loss of calcineurin function. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48(5):1377–1387. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rui O, Hahn M. The Slt2-type MAP kinase Bmp3 of Botrytis cinerea is required for normal saprotrophic growth, conidiation, plant surface sensing and host tissue colonization. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8(2):173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hou Z, Xue C, Peng Y, Katan T, Kistler HC, Xu J-R. A mitogen-activated protein kinase gene (MGV1) in Fusarium graminearum is required for female fertility, heterokaryon formation, and plant infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15(11):1119–1127. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.11.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu J-R, Staiger CJ, Hamer JE. Inactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Mps1 from the rice blast fungus prevents penetration of host cells but allows activation of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(21):12713–12718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levin D. Cell wall integrity signalling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69(2):262–291. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.262-291.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee K, Irie K, Watanabe Y, Araki H, Nishida E, Matsumoto K, Levin D. A yeast mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog (Mpk1p) mediates signalling by protein kinase C. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(5):3067–3075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madden K, Sheu Y-J, Baetz K, Andrews B, Snyder M. SBF cell cycle regulator as a target of the yeast PKC-MAP kinase pathway. Science. 1997;275(5307):1781–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baetz K, Moffat J, Haynes J, Chang M, Andrews B. Transcriptional coregulation by the cell integrity mitogen-activated protein kinase Slt2 and the cell cycle regulator Swi4. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(19):6515–6528. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6515-6528.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dodou E, Treisman R. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MADS-box transcription factor Rlm1 is a target for the Mpk1 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(4):1848–1859. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jung US, Levin DE. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression regulated by the yeast cell wall integrity signalling pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34(5):1049–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garrett-Engele P, Moilanen B, Cyert MS. Calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, is essential in yeast mutants with cell integrity defects and in mutants that lack a functional vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(8):4103–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bonilla M, Cunningham KW. Mitogen-activated protein kinase stimulation of Ca2+ signaling is required for survival of endoplasmic reticulum stress in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(10):4296–4305. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao C, Jung US, Garrett-Engele P, Roe T, Cyert MS, Levin DE. Temperature-induced expression of yeast FKS2 is under the dual control of protein kinase C and calcineurin. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(2):1013–1022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cyert MS. Calcineurin signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: how yeast go crazy in response to stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311(4):1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muller EM, Locke EG, Cunningham KW. Differential regulation of two Ca2+ influx systems by pheromone signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics. 2001;159(4):1527–1538. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matheos DP, Kingsbury TJ, Ahsan US, Cunningham KW. Tcn1p/Crz1p, a calcineurin-dependent transcription factor that differentially regulates gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genes Dev. 1997;11(24):3445–3458. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stathopoulos-Gerontides A, Guo JJ, Cyert MS. Yeast calcineurin regulates nuclear localization of the Crz1p transcription factor through dephosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1999;13(7):798–803. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cunningham KW, Fink GR. Calcineurin inhibits VCX1-dependent H+/Ca2+ exchange and induces Ca2+ ATPases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(5):2226–2237. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mizunuma M, Hirata D, Miyaoka R, Miyakawa T. GSK-3 kinase Mck1 and calcineurin coordinately mediate Hsl1 down-regulation by Ca2+ in budding yeast. EMBO J. 2001;20(5):1074–1085. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Imai J, Yahara I. Role of HSP90 in salt stress tolerance via stabilization and regulation of calcineurin. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(24):9262–9270. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9262-9270.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh SD, Robbins N, Zaas AK, Schell WA, Perfect JR, Cowen LE. Hsp90 governs echinocandin resistance in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans via calcineurin. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(7):e1000532. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Munro CA, Selvaggini S, De Bruijn I, Walker L, Lenardon MD, Gerssen B, Milne S, Brown AJP, Gow NAR. The PKC, HOG and Ca2+ signalling pathways co-ordinately regulate chitin synthesis in Candida albicans . Mol Microbiol. 2007;63(5):1399–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choi J, Kim Y, Kim S, Park J, Lee Y-H. MoCRZ1, a gene encoding a calcineurin-responsive transcription factor, regulates fungal growth and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae . Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46(3):243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(4):501–517. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Denning DW. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet. 2003;362:1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baixench M-T, Aoun N, Desnos-Ollivier M, Garcia-Hermoso D, Bretagne S, Ramires S, Piketty C, Dannaoui E. Acquired resistance to echinocandins in Candida albicans: case report and review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(6):1076–1083. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perlin DS. Current perspectives on echinocandin class drugs. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(4):441–457. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walker LA, Gow NAR, Munro CA. Fungal echinocandin resistance. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47(2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bowman SM, Free SJ. The structure and synthesis of the fungal cell wall. BioEssays. 2006;28(8):799–808. doi: 10.1002/bies.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reinoso-Martín C, Schüller C, Schuetzer-Muehlbauer M, Kuchler K. The yeast protein kinase C cell integrity pathway mediates tolerance to the antifungal drug caspofungin through activation of Slt2p mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2(6):1200–1210. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.6.1200-1210.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miyazaki T, Inamine T, Yamauchi S, Nagayoshi Y, Saijo T, Izumikawa K, Seki M, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Miyazaki Y, Kohno S. Role of the Slt2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in cell wall integrity and virulence in Candida glabrata . FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10(3):343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Munro CA. Chapter four—chitin and glucan, the yin and yang of the fungal cell wall, implications for antifungal drug discovery and therapy. In: Sima S, Geoffrey MG, editors. Adv Appl Microbiol. London: Academic Press; 2013. pp. 145–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Walker LA, Munro CA, de Bruijn I, Lenardon MD, McKinnon A, Gow NAR. Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues Candida albicans from echinocandins. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(4):e1000040. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wiederhold NP, Kontoyiannis DP, Prince RA, Lewis RE. Attenuation of the activity of caspofungin at high concentrations against Candida albicans: possible role of cell wall integrity and calcineurin pathways. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(12):5146–5148. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5146-5148.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gaughran JP, Lai MH, Kirsch DR, Silverman SJ. Nikkomycin Z is a specific inhibitor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chitin synthase isozyme Chs3 in vitro and in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(18):5857–5860. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5857-5860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]