Abstract

The function and survival of pancreatic β cells critically rely on complex electrical signaling systems composed of a series of ionic events, namely fluxes of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Cl− across the β cell membranes. These electrical signaling systems not only sense events occurring in the extracellular space and intracellular milieu of pancreatic islet cells, but also control different β cell activities, most notably glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Three major ion fluxes including K+ efflux through ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, the voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) channel-mediated Ca2+ influx and K+ efflux through voltage-gated K+ (KV) channels operate in the β cell. These ion fluxes set the resting membrane potential and the shape, rate and pattern of firing of action potentials under different metabolic conditions. The KATP channel-mediated K+ efflux determines the resting membrane potential and keeps the excitability of the β cell at low levels. Ca2+ influx through CaV1 channels, a major type of β cell CaV channels, causes the upstroke or depolarization phase of the action potential and regulates a wide range of β cell functions including the most elementary β cell function, insulin secretion. K+ efflux mediated by KV2.1 delayed rectifier K+ channels, a predominant form of β cell KV channels, brings about the downstroke or repolarization phase of the action potential, which acts as a brake for insulin secretion owing to shutting down the CaV channel-mediated Ca2+ entry. These three ion channel-mediated ion fluxes are the most important ionic events in β cell signaling. This review concisely discusses various ionic mechanisms in β cell signaling and highlights KATP channel-, CaV1 channel- and KV2.1 channel-mediated ion fluxes.

Keywords: Calcium mobilization, Electrophysiology, Exocytosis, Ion channel, Pancreatic endocrine cell, Protein kinase

Introduction

Pancreatic β cells are a major cellular component of the islets of Langerhans. These cells are exquisitely sensitive to glucose. They secrete insulin, which is the only hormone capable of lowering blood glucose in the body, and thus play a unique role in glucose homeostasis. To timely and accurately release insulin in response to changes in blood glucose levels, a series of ionic events, namely fluxes of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Cl− across the β cell membranes occur [1, 2]. The electrically excitable β cell employs these ion fluxes to constitute complex ionic mechanisms that sense events occurring in its extracellular space and intracellular milieu and control different β cell activities [1–8]. This is because these ionic mechanisms are sooner or later coupled to the versatile intracellular signal Ca2+ that participates in the regulation of all known molecular and cellular events, such as exocytosis, endocytosis, protein phosphorylation, gene expression, metabolism, differentiation, growth and even cell death [7, 8]. This review summarizes current knowledge of various ionic mechanisms and their building blocks, ion channels, in β cell signaling.

Among the complex ionic mechanisms, ion fluxes through ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) channels and voltage-gated K+ (KV) channels are the most important ionic events in β cell signaling. KATP, CaV and KV channels take center stage in generation of electrical activities to control glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Disturbances in these three ion channel-mediated ion events inevitably impair β cell function and survival, and thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of diabetes. This review highlights the KATP, CaV and KV channel-mediated ionic events, their functional significances and the general structure and important regulation of KATP channels, CaV1 channels and KV2.1 channels on top of the general discussion of the various ionic mechanisms.

Ionic mechanisms operate in various subcellular compartments of the β cell

The complexity of ionic mechanisms relies on the diversity of their elementary building blocks, ion channels. The β cell accommodates more than 16 ion channel families consisting of about 60 different types of ion channels responsible for complex ionic mechanisms (Table 1) [1, 2, 5–80]. We summarize these ion channels with emphasis on their ion selectivity, activators, blockers and function in Table 1 to provide a concise guide to β cell ion channel research. These ion channels operate not only in the β cell plasma membrane but also in subcellular organelle membranes to generate sophisticated electrical activities and specific ionic milieus, such as cytosolic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) and pH, for complex β cell signaling.

Table 1.

Ion channel families and their members in different subcellular compartments of the pancreatic β cell

| Families | Members | Ion selectivity | Activators | Blockers | Function in the β cell | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma membrane | ||||||

| Voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channel | NaV1.3 channel | Na+ | Batrachotoxin, veratridine | Saxitoxin, tetrodotoxin | – | [9, 10] |

| NaV1.6 channel | Na+ | Batrachotoxin, veratridine | Saxitoxin, tetrodotoxin | Action potential upstroke in the human β cell | [1, 10–13] | |

| NaV1.7 channel | Na+ | Batrachotoxin, veratridine | Saxitoxin, tetrodotoxin | Action potential upstroke in the human β cell | ||

| Voltage-gated calcium (CaV) channel | CaV1.2 channel | Ca2+ | FPL64176, (S)-(−)-Bay K8644, SZ(+)-(S)-202-791 | Calciseptine, diltiazem, nifedipine, verapamil | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | [1, 7, 8, 11, 13–16] |

| CaV1.3 channel | Ca2+ | (S)-(−)-Bay K8644 | Nifedipine, verapamil | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| CaV2.1 channel | Ca2+ | – | ω-Agatoxin IVA | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| CaV2.2 channel | Ca2+ | – | ω-Conotoxin GVIA | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| CaV2.3 channel | Ca2+ | – | SNX 482 | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| CaV3.1 channel | Ca2+ | – | Mibefradil, NNC 55-0396, TTA-A2, TTA-P2, Z944 | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| CaV3.2 channel | Ca2+ | – | Mibefradil, NNC 55-0396, TTA-A2, TTA-P2, Z944 | Action potential upstroke, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| Voltage-gated potassium (KV) channel | KV1.4 | K+ | – | α-Dendrotoxin, margatoxin, noxiustoxin, tetraethylammonium, 4-aminopyridine | – | [1, 6, 10, 11, 13, 17–22] |

| KV1.5 | K+ | – | α-Dendrotoxin, margatoxin, noxiustoxin, tetraethylammonium, 4-aminopyridine | – | ||

| KV1.6 | K+ | – | α-Dendrotoxin, margatoxin, noxiustoxin, tetraethylammonium, 4-aminopyridine | – | ||

| KV2.1 | K+ | – | Stromatoxin-1, tetraethylammonium | Action potential downstroke in the rodent β cell | ||

| KV2.2 | K+ | – | Stromatoxin-1, tetraethylammonium | – | ||

| KV3.2 | K+ | – | 4-Aminopyridine, tetraethylammonium, sea anemone toxin BDS-I | – | ||

| KV6.2 | Modifier/silencer | – | – | – | ||

| KV9.3 | Modifier/silencer | – | – | – | ||

| ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel | Kir6.2/SUR1 channel | K+ | Diazoxide | ATP/ADP ratio, sulfonylureas, glinides | Resting membrane potential | [1, 2, 5, 13, 15, 23] |

| Calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channel | BK channel (KCa1.1, KCNMA1) | K+ | Voltage-dependent, [Ca2+]i, NS004, NS1619 | Charybdotoxin, iberiotoxin, tetraethylammonium | Modulation of action potential shape and firing, action potential downstroke in the human β cell | [1, 10, 11, 13, 15] |

| SK1 channel (KCa2.1, KCNN1) | K+ | [Ca2+]i | Apamin? UCL 1684 | Repolarization of plateau potentials, [Ca2+]i oscillation | [1, 6, 24–28] | |

| SK2 channel (KCa2.2, KCNN2) | K+ | [Ca2+]i | Apamin, UCL 1684 | Repolarization of plateau potentials, [Ca2+]i oscillation | ||

| SK3 channel (KCa2.3, KCNN3) | K+ | [Ca2+]i | Apamin, UCL 1684 | Repolarization of plateau potentials, [Ca2+]i oscillation | ||

| IK channel (KCa3.1, KCNN4, SK4) | K+ | [Ca2+]i | Charybdotoxin | Repolarization of plateau potentials, [Ca2+]i oscillation | ||

| TRP channel | TRPA1 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Thermosensitive (<17 °C)? voltage-dependent, [Ca2+]i, mechanical stress, isothiocyanates, icilin, allicin, H2O2, 1,4-dihydropyridines | Ruthenium red | Ca2+ influx, depolarization, insulin secretion | [10, 29, 30] |

| TRPC1 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Membrane stretch, store depletion, NO-mediated cysteine S-nitrosylation | 2-APB, Gd3+, La3+, SKF96365 | – | [10, 30, 31] | |

| TRPC3 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Diacylglycerols | 2-APB, Gd3+, La3+, Ni2+, SKF96365, pyrazole-3 | – | [10, 32] | |

| TRPC4 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | NO-mediated cysteine S-nitrosylation, Gq-PLC pathways, La3+ (μM) | 2-APB, La3+ (mM), niflumic acid, SKF96365 | – | [10, 30, 31] | |

| TRPC5 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | NO-mediated cysteine S-nitrosylation? extracellular H+, [Ca2+]i, La3+ (μM) | 2-APB, chlorpromazine, flufenamic acid, La3+ (mM), SKF96365 | – | [10, 32] | |

| TRPC6 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Gq-PLC pathways/diacylglycerols, 2,4 diahexanxoylphloroglucinol, flufenamate, hyperforin | 2-APB, amiloride, Cd2+, Gd3+, extracellular H+, SKF96365 | – | [10, 30, 31] | |

| TRPM2 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Thermosensitive (~35 °C), H2O2, [Ca2+]i, ADPR, cADPR, arachidonic acid | Extracellular H+, Zn2+, 2-APB, clotrimazole | Ca2+ influx, insulin secretion, H2O2-induced apoptosis | [10, 30, 31, 33, 34] | |

| TRPM3 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Thermosensitive (15–25 °C), hypotonic cell swelling, steroid hormones, nifedipine | Intracellular Mg2+, extracellular Na+, 2-APB, Gd3+, La3+ | Ca2+ influx, Zn2+ influx | [10, 30, 31, 35, 36] | |

| TRPM4 | Non-selective/Ca2+-impermeable | Voltage-dependent, thermosensitive (15–25 °C at +25 mV), [Ca2+]i (transient activation), decavanadate | 9-Phenanthrol, clotrimazole, flufenamic acid, intracellular spermine, ATP, ADP, AMP, adenosine | Depolarization, insulin secretion? | [10, 30, 31, 37, 38] | |

| TRPM5 | Non-selective/Ca2+-impermeable | Voltage-dependent, thermosensitive (15–25 °C at −75 mV), [Ca2+]i (transient activation) | Flufenamic acid, intracellular spermine, extracellular H+ | Depolarization, [Ca2+]i oscillation, insulin secretion | [10, 30, 31, 39, 40] | |

| TRPV1 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Voltage-dependent, thermosensitive (>43 °C), NO-mediated cysteine S-nitrosylation, camphor, capsaicin, extracellular H+ | 2-APB, allicin, ruthenium red | Insulin secretion | [10, 30, 31, 41] | |

| TRPV2 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Thermosensitive (>35 °C), voltage, 2-APB | Amiloride, ruthenium red, SKF96365 | Ca2+ influx, insulin secretion | [10, 30, 31, 42] | |

| TRPV4 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Constitutively active, thermosensitive (>24–32 °C), mechanical stimuli, NO-mediated cysteine S-nitrosylation | Gd3+, La3+, ruthenium red | Ca2+ influx, apoptosis | [10, 30, 31, 43] | |

| Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channel | HCN1 channel | Na+, K+ | cAMP, cGMP | Cs+, ivabradine, ZD7288 | Insulin secretion under hypokalemic conditions | [10, 44, 45] |

| HCN2 channel | Na+, K+ | cAMP, cGMP | Cs+, ivabradine, ZD7288 | Insulin secretion under hypokalemic conditions | ||

| HCN3 channel | Na+, K+ | – | Cs+, ivabradine, ZD7288 | Insulin secretion under hypokalemic conditions | ||

| HCN4 channel | Na+, K+ | cAMP, cGMP | Cs+, ivabradine, ZD7288 | Insulin secretion under hypokalemic conditions | ||

| Purinergic P2X receptor channel | P2X1 receptor channel | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | ATP, αβ-meATP, 2-meSATP | Suramin, PPADS | Ca2+ influx, depolarization, insulin secretion | [46, 47] |

| P2X3 receptor channel | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | ATP, αβ-meATP, 2-meSATP | Suramin, PPADS | Ca2+ influx, depolarization, insulin secretion | ||

| Glutamate receptor ion channel | α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor channel | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Glutamate, AMPA | NBQX, CNQX | Ca2+ influx, depolarization, insulin secretion | [48, 49] |

| Kainate receptor channel | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Glutamate, kainate | NS102, CNQX | Ca2+ influx, depolarization, insulin secretion | ||

| N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channel | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Glutamate, aspartate, NMDA, voltage-dependent | Mg2+, Zn2+, amantadine, MK-801 | Ca2+ influx, depolarization, insulin secretion | ||

| γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor ion channel | – | Cl− | GABA, muscimol, benzodiazepine | Bicuculline, picrotoxin, gabazine | Depolarization, insulin secretion | [50–52] |

| Chloride channel | Volume-regulated anion channel | Cl− | Swelling, ATP, cAMP, glyburide, tolbutamide, glibenclamide | DIDS, NPPB, DCPIB, tenidap | Depolarization, insulin secretion | [1, 53–56] |

| CFTR chloride channel | Cl− | PKA phosphorylation, bacterial enterotoxins | Glibenclamide, diphenylamine-2-carboxylate, NPPB, niflumic acid | – | [57, 58] | |

| Endoplasmic reticulum/nuclear envelope | ||||||

| ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel | Kir6.2/SUR1 channel | K+ | Diazoxide | ATP/ADP ratio, tolbutamide | Nuclear Ca2+ signaling | [59–61] |

| Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) ion channel | IP3R1 channel | Ca2+ | IP3, cytosolic ATP, [Ca2+]i, adenophostin A | Heparin, caffeine, decavanadate, PIP2, xestospongin C | Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | [62, 63] |

| IP3R2 channel | Ca2+ | IP3, [Ca2+]i, adenophostin A | Heparin, decavanadate | Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| IP3R3 channel | Ca2+ | IP3, [Ca2+]i | Heparin, decavanadate | Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| RyR ion channel | RyR1 channel | Ca2+ | [Ca2+]i, voltage-dependent, ATP, caffeine, ryanodine (nM–μM) | Mg2+, dantrolene, ryanodine (>100 μM), ruthenium red, [Ca2+]i (>100 μM) | Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | [64, 65] |

| RyR2 channel | Ca2+ | [Ca2+]i, ATP, caffeine, ryanodine (nM–μM) | Mg2+, ryanodine (>100 μM), ruthenium red, [Ca2+]i (>1 mM) | Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| RyR3 channel | Ca2+ | [Ca2+]i, ATP, caffeine, ryanodine (nM–μM) | Mg2+, dantrolene, ruthenium red, [Ca2+]i (>1 mM) | Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, Ca2+ signaling, insulin secretion | ||

| Insulin granule | ||||||

| ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel | Kir6.2/SUR1 channel | – | – | – | – | [66] |

| Chloride channel | ClC-3 Cl− channel | Cl− | ATP/ADP ratio | DIDS, ClC-3 Cl− channel antibody | Acidification and priming of insulin granules | [67–70] |

| TRP channel | TRPV5 | highly Ca2+-permeable | Constitutively active/inactivated by [Ca2+]i | Econazole, Mg2+, miconazole, ruthenium red | Ca2+ mobilization from insulin granules? | [10, 30, 31] |

| Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) ion channel | IP3R3 channel? | – | – | – | Ca2+ mobilization from insulin granules? | [71] |

| RyR ion channel | – | Ca2+ | Caffeine, 4-chloro-3-ethylphenol, cADPR | – | Ca2+ mobilization from insulin granules | [72] |

| Chromogranin-positive/insulin-negative granule | ||||||

| ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel | Kir6.2/SUR1 channel | – | – | – | Glucose-induced recruitment of KATP channels from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane | [73] |

| Mitochondrion | ||||||

| Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) | VDAC1 channel | ATP, ADP, pyruvate, malate, and other metabolites, ions | Bax | Bcl-xL, NADH | Metabolite transport, ion transport | [74–76] |

| VDAC2 channel | ATP, ADP, pyruvate, malate, and other metabolites, ions | Bax | Bcl-xL, NADH | Metabolite transport, ion transport | ||

| VDAC3 channel | ATP, ADP, pyruvate, malate, and other metabolites, ions | Bax | Bcl-xL, NADH | Metabolite transport, ion transport | ||

| Mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) | – | Ca2+, other divalent cations | Ca2+, voltage-dependent, spermine | Mg2+, ruthenium red | Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake | [76–78] |

| ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel | – | K+ | GTP, GDP, diazoxide | ATP, ADP, glibenclamide, 5-hydroxydecanoate | Dissipation of the inner mitochondrial membrane potential | [79, 80] |

| Lysosome | ||||||

| TRP channel | TRPM2 | Non-selective/Ca2+-permeable | Heat ~35 °C, H2O2, [Ca2+]i, ADPR, cADPR, arachidonic acid | Extracellular H+, Zn2+, 2-APB, clotrimazole | Ca2+ mobilization from lysosome, H2O2-induced apoptosis | [10, 30, 31, 33] |

ADP adenosine 5′-diphosphate, ADPR adenosine 5′-diphosphate ribose, AMP adenosine 5′-monophosphate, 2-APB 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, ATP adenosine 5′-triphosphate, αβ-meATP αβ-methyleneadenosine 5′-triphosphate, BK large conductance calcium-activated potassium, cADPR cyclic adenosine 5′-diphosphate ribose, cAMP cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate, [Ca 2+ ] i cytosolic free calcium concentration, cGMP cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate, CNQX 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, DCPIB 4-(2-butyl-6,7-dichloro-2-cyclopentyl-indan-1-on5-yl)oxobutyric acid, DIDS 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid, FPL64176 2,5-dimethyl-4-[2-(phenylmethyl)benzoyl]-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxlic acid methyl ester, GDP guanosine diphosphate, GTP guanosine triphosphate, IK intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium, IP 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, Kir inward rectifier K+, MK-801 (5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate, 2-meSATP 2-methylthioadenosine 5′-triphosphate, NADH reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NBQX 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide, NNC 55-0396 (1S,2S)-2-(2-(N-[(3-benzimidazol-2-yl)propyl]-N-methylamino)ethyl)-6-fluoro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-isopropyl-2-naphtyl cyclopropanecarboxylate dihydrochloride, NO nitric oxide, NPPB 5-Nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid, NS004 1-(2-hydroxy-5-chlorophenyl)-5-trifluoromethyl-2-benzimidazolone, NS102 6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5-nitro-1H-benz[g]indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime, NS1619 1,3-dihydro-1-[2-hydroxy-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2H-benzimidazol-2-one, PIP 2 phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PKA protein kinase A, PLC phospholipase C, PPADS pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid, (S)-(-)-Bay K8644 S-(-)-1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid methyl ester, SK small conductance calcium-activated potassium, SKF96365 1-[2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]ethyl]imidazole, SNX 482 41 amino acid peptide (GVDKAGCRYMFGGCSVNDDCCPRLGCHSLFSYCAWDLTFSD), SUR sulfonylurea receptor, SZ(+)-(S)-202-791 isopropyl 4-(2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)-1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-3-pyridinecarboxylate, TTA-A2 (R)-2-(4-cyclopropylphenyl)-N-(1-(5-(2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy)pyridin-2-yl)ethyl)acetamide, TTA-P2 3,5-dichloro-N-[1-(2,2-dimethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoro-piperidin-4-ylmethyl]-benzamide, UCL 1684 6,12,19,20,25,26-hexahydro-5,27:13,18:21,24-trietheno-11,7-metheno-7H-dibenzo [b,n] [1, 5, 12, 16] tetraazacyclotricosine-5,13-diium dibromide, ZD7288 4-ethylphenylamino-1,2-dimethyl-6-methylaminopyrimidinium chloride, Z944 N-((1-(2-(tert-butylamino)-2-oxoethyl) piperidin-4-yl)methyl)-3-chloro-5-fluorobenzamide hydrochloride, – unknown, ? controversy

KATP, CaV and KV channel-mediated ion fluxes

The β cell plasma membrane is equipped with about 50 different types of ion channels (Table 1). The KATP channel-mediated K+ efflux sets the resting membrane potential and maintains low levels of β cell excitability (Table 1; Fig. 1) [1, 2, 15, 23]. Ca2+ influx through CaV channels, mainly CaV1.2 channels, contributes to the upstroke or depolarization phase of the action potential and controls all known molecular and cellular activities in the β cell, and in particular glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Table 1; Fig. 1) [2, 7, 8, 14]. K+ efflux mediated by KV2.1 delayed rectifier K+ channels, a predominant form of β cell KV channels, causes the downstroke or repolarization phase of the action potential and acts as a brake for insulin secretion (Table 1; Fig. 1) [2, 6]. These three critical ion fluxes in β cell signaling have attracted extraordinary attention and are discussed in detail in the later sections.

Ion fluxes through transient receptor potential (TRP) channels

In the β cell plasma membrane, there is a diverse repertoire of ion channels to assemble sophisticated ionic mechanisms [1]. In addition to KATP, CaV and KV channels, more than a dozen members of the TRP channel family exist in the β cell plasma membrane (Table 1) [30, 31]. Most β cell TRP channels are non-selectively permeable to cations including Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ [10, 30, 31]. Ca2+-impermeable TRPM4 and TRPM5 channels as well as highly Ca2+-permeable TRPV5 channels are also present in the β cell [30, 31]. β Cell TRP channels activate in response to chemical challenges, mechanical stimuli or thermal alterations in a voltage-dependent or voltage-independent manner [10, 30, 31]. However, it is still a challenging task to match different physiological scenarios to selective activation of β cell TRP channels. Cation influx through β cell TRP channels not only depolarizes the β cell plasma membrane to increase β cell excitability, but also contributes to [Ca2+]i to regulate Ca2+-dependent cellular processes including glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [10, 30, 31]. Table 1 lists basic information about β cell TRP channels. Here we highlight TRPM2 channels to exemplify the physiological and pathophysiological significance of β cell TRP channels. TRPM2 channels have been demonstrated to bring about important ionic events in regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [10, 30, 31, 33, 34]. TRPM2 knockout mice display glucose intolerance accompanied by insufficient elevation in plasma insulin levels. This is attributed to decreased [Ca2+]i response in TRPM2-null β cells and impaired insulin secretion from TRPM2-deficient islets exposed to high glucose [34]. Indeed, arachidonic acid, cADPR, ADPR, H2O2, [Ca2+]i and temperature changes have been shown to activate β cell TRPM2 channels [10, 30, 31, 33]. However, it appears that glucose employs a set of these signal molecules, e.g., arachidonic acid, [Ca2+]i and H2O2, rather one of them to activate TRPM2 channels under physiological conditions [30, 31, 33, 34].

TRPM2 channels localize not only in the β cell plasma membrane but also in lysosomes from which these channels mobilize Ca2+ to the cytosol compartment to participate in H2O2-induced apoptosis [33]. β Cells express antioxidant enzymes at relatively low levels and are vulnerable to oxidative damage [81]. Exposure of β cells to H2O2 gives rise to a significant increase in intracellular ADPR, which has been considered as the most potent and specific TRPM2 channel activator among all known endogenous TRPM2 channel-activating molecules [82]. ADPR activates TRPM2 channels by binding to the NUDT9-H domain of these channels to bring about both Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane TRPM2 channels and Ca2+ release via the lysosomal TRPM2 channels [33, 83]. Indeed, both of these two ionic events mediate H2O2-induced β cell apoptosis, but the former is more important than the latter [33]. However, the latter alone suffices to trigger β cell apoptosis [33].

A puzzling ion flux for initiation of β cell action potentials

The commonly used paradigm of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion simply attributes initiation of β cell action potentials to depolarization induced by closure of the KATP channel-mediated K+ efflux. In fact, this closure alone hardly suffices to trigger β cell action potentials and insulin secretion [1, 2, 15]. On top of the closure of the KATP channel-mediated K+ efflux, a puzzling ion flux, which forms a depolarizing inward current, occurs across the β cell plasma membrane to initiate action potentials and insulin secretion [1, 2, 15]. It has been suggested that influx of both Na+ and Ca2+ is involved [15]. However, the ion species responsible for and the molecular device conducting such a depolarizing inward current remain in dispute. Current findings open up the following possibilities. Some researchers interpret the puzzling ion flux as a Cl− efflux or a cation influx through TRP channels [40, 54, 84]. Others consider that the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel and volume-regulated anion channel mediate this depolarizing inward current [1, 57, 85, 86]. The mouse β cell undergoes sub-threshold depolarization when bathed in 5 mM glucose after exposure to 10 mM glucose. Subsequently, removal of extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ leads to an obvious repolarization of the β cell plasma membrane [15]. This demonstrates that influx of both Na+ and Ca2+ apparently contributes to β cell depolarization when more than 90 % of KATP channel conductance is blocked by exposure to 5 mM glucose [15, 87, 88]. The depolarizing inward current resulting from this cation influx is characterized by a linear voltage dependence between −90 and −50 mV, a whole-cell slope conductance of 0.25 nS and an extrapolated reversal potential of about −20 mV [15]. It should be pointed out that thorough investigation is needed to determine ion identities and conducting molecules of the puzzling ion flux which is critical for initiating β cell action potentials and triggering insulin secretion.

Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) ion channels and ryanodine receptor (RyR) ion channels

Ca2+ dynamics in the β cell depends not only on diverse Ca2+ fluxes across the plasma membrane but also on various Ca2+ shuttles among subcellular compartments. Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores is crucial for Ca2+ dynamics in the β cell [89]. The ligand-gated Ca2+ release channels, IP3Rs and RyRs, mainly localize in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that stores large amounts of Ca2+ [62–65, 89]. Upon activation of IP3Rs and RyRs by a variety of stimuli including neurotransmitters, hormones, metabolic fuels and Ca2+, stored Ca2+ rapidly releases into the cytosolic compartment through Ca2+-conducting pores of these ligand-gated channels resulting in complex dynamic changes in [Ca2+]i [62–65, 89]. Glucose-induced [Ca2+]i changes in the mouse islet manifest as fast oscillations with a period from several seconds to 1 min, slow oscillations with a period ranging from one to several minutes or mixed oscillations characterized by fast oscillations superimposed on slow oscillations [89–91]. These [Ca2+]i changes result from corresponding alterations in the membrane potential of the β cell and trigger corresponding oscillatory insulin secretion [89–91]. Mouse β cells within an islet display neither compound electrical bursting, namely clusters of membrane potential oscillations separated by prolonged silent intervals, nor mixed [Ca2+]i oscillations when the ER Ca2+ pool is depleted by the ER Ca2+ pump inhibitor thapsigargin or genetic ablation of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump SERCA 3 [91]. The complex dynamic changes in [Ca2+]i instruct not only exocytotic proteins to execute insulin exocytosis but also Ca2+-sensitive proteins, such as Ca2+-sensitive enzymes and Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors, to regulate corresponding molecular and cellular events [62–65, 89].

All three IP3R subtypes (IP3R1, IP3R2 and IP3R3) are present in the β cell ER membrane [62]. These IP3-gated ion channels open their Ca2+-conducting pores in response to de novo activation of phospholipase C-linked G protein-coupled receptors, e.g., muscarinic M3 receptors and purinergic P2Y receptors [62]. Particularly, the most important physiological insulin secretagogue glucose efficiently elevates IP3 levels in the β cell and consequently activates IP3Rs to release Ca2+ from IP3-sensitive stores into the cytoplasm [62]. This occurs because β cell PLC undergoes activation to produce IP3 in response to glucose-induced depolarization, glucose-evoked Ca2+ influx or glucose-initiated autocrine stimulation of P2Y receptors by ATP coreleased with insulin [62]. Eventually, Ca2+ released from IP3-sensitive stores participates in insulin granule trafficking and exocytosis as well as other Ca2+-dependent processes [62].

All three subtypes of RyRs, namely RyR1 RyR2 and RyR3, are embedded in the β cell ER membrane [64, 89]. In the physiological context, glucose-induced depolarization and Ca2+ influx as well as the glucose metabolism-derived molecules ATP, fructose 1,6-diphosphate, long-chain acyl CoA and cADPR activate these ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release channels [65, 89]. In response to these stimuli, RyRs undergo an extremely rapid conformational switch from an impermeable state to a highly permeable pore. The highly permeable pore allows Ca2+ in ryanodine-sensitive stores to rapidly release into the cytoplasm, where Ca2+ efflux from ryanodine-sensitive stores regulates insulin secretion and interacts with Ca2+-sensitive targets [65, 89].

ClC-3 Cl− channel-mediated Cl− entry into insulin granules

The insulin granule membrane mediates complex ion fluxes through several types of ion channels, e.g., KATP channels, ClC-3 Cl− channels, TRP channels, IP3R ion channels and RyR ion channels (Table 1) [30, 31, 66–72]. These ionic mechanisms play an important role in maturation, trafficking and priming of insulin granules [30, 31, 66–72]. The ClC-3 Cl− channel-mediated Cl− entry into insulin granules exemplifies the importance of ionic mechanisms occurring in the insulin granule membrane [69, 70]. Increase in the ATP/ADP ratio leads to an accelerated Cl− entry through the ClC-3 Cl− channel and a concomitantly elevated H+ uptake via the V-type H+-ATPase into the insulin granule [67]. Resultant intragranular acidification is not only prerequisite for conversion of proinsulin to insulin and formation of insulin crystals, but also activates the V0 domain of the V-type H+-ATPase, a pH sensor, which participates in priming and fusion of the secretory granule [92]. This is consistent with the fact that genetic ablation of ClC-3 Cl− channels severely impairs intragranular acidification and insulin secretion evoked by depolarization or glucose stimulation [69, 70].

The KATP conductance determines the excitability of the β cell plasma membrane

At rest, the β cell plasma membrane is more permeable to K+ than to other ionic species [2]. The concentration of K+ is greater inside the β cell (150 mM) than outside (5 mM). Such a concentration gradient drives a net diffusion of K+ across the plasma membrane out of the β cell. The K+ conductance sets the resting membrane potential of the β cell to near the K+ equilibrium potential (−75 mV) [2]. K+ channels embedded in the plasma membrane serve as molecular substrates for K+ conductance [93, 94]. The body is equipped with a variety of K+ channels due to the diversity of K+ channel genes [93, 94]. Virtually, all cells in the body express K+ channels [93, 94]. Generally speaking, all types of K+ channels are involved in stabilization of the membrane potential acting as a brake on electrical excitability. Open K+ channels drive the membrane potential closer to the K+ equilibrium potential and further away from the firing threshold of the action potential. Some types of K+ channels open in response to depolarization and ligand binding, but are otherwise closed [93, 94]. In contrast, other K+ channels are open at rest to sustain the resting membrane potential [93, 94].

Different types of cells employ distinct classes of K+ channels to set the resting membrane potential [93, 94]. The β cell alters its membrane potential below the action potential threshold by opening or closing KATP channels and thereby determining the excitability of the β cell plasma membrane (Fig. 1) [2, 13, 23, 95]. Noteworthy is that the β cell does not fire an action potential even though more than 90 % of the KATP channels are closed. Further closure of the remaining KATP channels (less than 10 %) leads to depolarization of the β cell plasma membrane up to the action potential threshold and action potential firing [15, 96]. β cell KATP channel activity exponentially decreases with increasing glucose concentration. Incubation with 2–3 mM glucose, commonly used to maintain basal insulin release in vitro, already inhibits 50 % of the KATP currents in the β cell, but still maintains a stable resting membrane potential and thus low level of β cell excitability. When glucose is elevated to a fasting blood glucose level of 5 mM, more than 90 % decrease in KATP channel activity, sub-threshold depolarization and corresponding increase in β cell excitability occur. Exposure to glucose concentrations above 7 mM completely blocks β cell KATP channels leading to supra-threshold depolarization and action potential firing [15, 87, 88]. Figure 1 shows that exposure to a stimulatory glucose concentration (16.7 mM) gradually closes KATP channels resulting in a corresponding depolarization and an equivalent decrease in the KATP conductance (gKATP) (Fig. 1). Consequently, β cell excitability gradually increases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of β cell responses to glucose stimulation. a Membrane potential changes in a mouse pancreatic β cell induced by a step increase in glucose concentration from 2.8 to 16.7 mM. KATP channels open at a basal glucose level (2.8 mM) and maintain low levels of β cell excitability. KATP channels gradually close, as manifested by a corresponding depolarization and an equivalent decrease in the KATP conductance (gKATP), following exposure to a stimulatory glucose concentration (16.7 mM). CaV1 channels open as soon as the β cell plasma membrane is depolarized to the firing threshold of action potentials. The CaV1 channel-mediated Ca2+ entry results in a rapid, further depolarization of the β cell plasma membrane causing the upstroke or depolarization phase of the action potential reflected by a rapid increase in the CaV1 conductance (gCaV1). The delayed rectifier K+ channel KV2.1 becomes activated to mediate a K+ efflux when the action potential reaches its peak. The KV2.1 channel-mediated efflux quickly repolarizes the β cell plasma membrane leading to the downstroke or repolarization phase of the action potential, which acts as a brake for insulin secretion due to shutting down the CaV channel-mediated Ca2+ entry. b Comparison of KATP channel activity, electrical activity and insulin secretion induced by different concentrations of glucose between human and mouse β cells [13, 15, 87, 88, 96, 239–242]

Structure and properties of β cell KATP channels

The β cell KATP channel mediates the resting K+ conductance that is effectively blocked by intracellular ATP and regulated by numerous physiological stimuli and pharmacological compounds [2, 13, 23, 95]. Obviously, alteration in the K+ conductance through β cell KATP channels shifts the membrane potential leading to changes in the excitability of the β cell plasma membrane. This makes β cells rely on KATP channels to initiate and end the β cell-unique function in terms of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [2, 13, 23, 95]. Therefore, it is of importance to understand the structural bases for β cell KATP channel conductivity and β cell KATP channel regulation as well as underlying mechanisms.

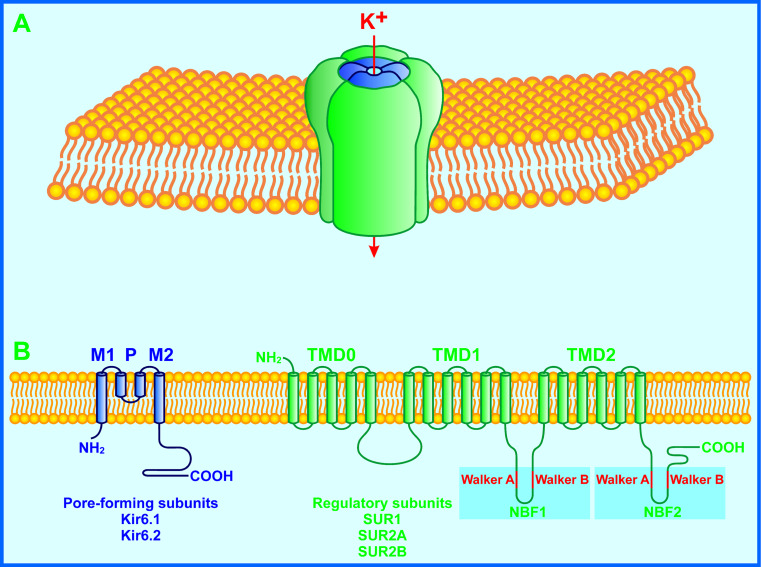

The KATP channel consists of potassium inward rectifier 6 (Kir6.x) and sulfonylurea receptor (SURx) subunits (Fig. 2) [3–5]. The former is a pore-forming subunit, being a member of the inward rectifier K+ channel family. The latter belongs to the ATP-binding cassette protein family and acts as a regulatory subunit [3–5]. Mammalian KATP channels are encoded by two Kir6.x genes, Kir6.1 (KCNJ8) and Kir6.2 (KCNJ11), and two SURx genes, SUR1 (ABCC8) and SUR2 (ABCC9). Both the SUR1 and SUR2 can be alternatively spliced into multiple isoforms. The alternatively splicing isoforms of SUR1 and SUR2 genes selectively express in different cell types with either Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 to form cell-type specific KATP channels [3–5].

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of a KATP channel. a The KATP channel subunit complex in the plasma membrane. Four Kir6.x and four SURx subunits physically associate with each other to assemble into a K+-conducting channel. Kir6.x subunits are situated in the middle of the complex to form a K+-conducting pore. SURx subunits are symmetrically grouped around Kir6.x subunits to serve as regulators of the K+-conducting pore. b Transmembrane topology and major alternative splicing isoforms of KATP channel subunits. The smaller Kir6.x subunit is composed of two transmembrane helices (M1 and M2), intracellular N- and C-terminal tails. The larger SUR1 subunit consists of a five-helix transmembrane domain (TMD0), two six-helix transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2) and two nucleotide-binding folds (NBF1 and NBF2) with extracellular N- and intracellular C-terminal ends. Each NBF contains the conserved Walker A and Walker B motifs. In mammalian genomes, two Kir6.x genes, Kir6.1 (KCNJ8) and Kir6.2 (KCNJ11), and two SURx genes, SUR1 (ABCC8) and SUR2 (ABCC9), have been identified. There are multiple alternative splicing isoforms of SUR1 and SUR2 subunits. Major ones are SUR1, SUR2A and SUR2B that selectively express in different cell types with either Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 to form cell-type specific KATP channels. The β cell KATP channel comprises the Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits

The β cell KATP channel is composed of the Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits (Fig. 2) [3–5]. The small Kir6.2 subunit contains two transmembrane helices (M1 and M2) as well as intracellular N- and C-terminal tails. The large SUR1 subunit comprises a five-helix transmembrane domain (TMD0), two six-helix transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2) and two nucleotide-binding folds (NBF1 and NBF2) with extracellular N- and intracellular C-terminal ends [3–5]. Four Kir6.2 and four SUR1 subunits physically associate with each other to assemble into a compact structure (~18 nm in cross-section and ~13 nm in height) [97]. Kir6.2 subunits stand in the middle of the structure and their M1 and M2 helices linked by an extracellular loop form a K+-conducting pore. The cytoplasmic regions of each Kir6.2 subunit constitute binding sites for ATP and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to stabilize closed and open states of the channel, respectively [5, 97]. It has been suggested that the ATP-binding site is situated 2 nm below the membrane. The ATP-binding site is juxtaposed and overlaps with the PIP2-binding site. SUR1 subunits are symmetrically grouped around Kir6.2 subunits to act as regulatory subunits. SUR1 subunit NBFs provide MgATP and MgADP binding sites [5, 97].

Electrophysiological properties of β cell KATP channels have been thoroughly characterized [2, 13, 23, 98]. These channels in inside-out patches exhibit unitary conductances of 50–65 pS in a symmetrical 140 mM K+ gradient and 20–30 pS in the physiological K+ gradient ([K+]o/[K+]i of 5/150 mM) in the absence of internal blocking cations [2, 98–102]. The KATP channel unitary conductance measured in cell-attached patches with pipette containing 5 mM K+ drops to 13–15 pS due to the presence of intracellular blocking ions [2, 103, 104]. The current–voltage relationship for single KATP channels in cell-attached patches shows a pronounced inward rectification as manifested by a small increase in currents at potentials above +20 mV [2, 101]. Whole-cell KATP currents range between 100 and 200 pA induced by +10 mV excursions from a holding potential of −70 mV in the physiological K+ gradient after washout of cytoplasmic ATP [105, 106]. Under the same experimental conditions, the maximum whole-cell KATP conductance falls within the range between 10 and 20 nS and the KATP channel unitary conductance is about 20 pS [2, 99, 105, 106]. The density of functional KATP channels in the β cell can be estimated according to the equation G = NPγ where G is the whole-cell conductance, N is the number of KATP channels in the β cell, P is the open probability of the channel and γ is the single-channel conductance. An estimate of 500–1,000 functional KATP channels per cell is obtained if P is taken as 1. However, this value is underestimated since that P is considerably less than 1. The open probability of β cell KATP channels is expected to lie between 0.1 and 0.4 and can maximally reach up to 0.8 [107]. Therefore, the β cell is equipped with more than the above-estimated 500–1,000 functional KATP channels. It is noteworthy that the input resistance of the resting human β cell is considerably higher than that of the resting mouse β cell. This is clearly manifested in cell input resistance measurements where the resting membrane conductance is 60 pS/pF in the human β cell and 700 pS/pF in the mouse β cell [13, 96]. This demonstrates that the fraction of open KATP channels in the resting human β cell are significantly less than those in the resting mouse β cell and may at least partly explain why lower glucose concentrations are required for initiation of action potential firing and insulin secretion in human β cells compared to mouse β cells [13].

Regulation of β cell KATP channels

To fine-tune the excitability of the β cell plasma membrane and consequently control β cell function and in particular glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, the β cell KATP channel is subjected to regulation by a variety of physiological stimuli and pharmacological compounds, some of which are discussed below.

Cytoplasmic nucleotides

The KATP channel is defined in terms of ATP inhibition of its conductivity. Such an ATP inhibition endows KATP channels with the ability to serve as molecular sensors of β cell energy metabolism [5]. The β cell efficiently takes up glucose through the high capacity, low affinity glucose transporter-2. Subsequently, glucose undergoes metabolism in both glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle to produce ATP. ATP binds to ATP-binding sites in the Kir6.2 subunits causing inhibition of KATP channels, reduction in the ATP-sensitive K+ conductance and elevation in the excitability of the β cell plasma membrane (Figs. 1, 2, 5) [2, 5, 8, 14]. The ATP binding generates the energetic push to shut the ligand-operated gate of the KATP channel. Apparently, there are four ATP binding sites per K+ conducting pore made up of four Kir6.2 subunits. However, occupation of one ATP binding site in a Kir6.2 subunit is sufficient to close the channel [5]. The precise underlying mechanism remains to be clarified. KATP channels in different cell types display distinct ATP sensitivities [3, 4]. In inside-out patches, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration for ATP on β cell KATP channels is 5–15 μM [3]. ATP at 1 mM can completely ablate the K+ conductance through β cell KATP channels in isolated membrane patches [3, 108]. ATP binding to Kir6.2 subunits and inhibition of their conductivity are Mg-independent and do not require ATP hydrolysis [3, 5, 108].

Fig. 5.

A scheme depicting functions and regulatory mechanisms of ion channels and cytosolic free Ca2+ in β cells. The β cell is equipped with three major types of ion channels, KATP, CaV1 and KV2.1. These channel-mediated ion fluxes establish the resting membrane potential, the depolarization and repolarization phases of the action potential, respectively, constituting complex electrical signaling systems. These electrical signaling systems are coupled to the versatile signaling molecule Ca2+ that participates in the regulation of all known molecular and cellular events, such as exocytosis, endocytosis, protein phosphorylation, gene expression, metabolism, differentiation, growth and even cell death. β Cell KATP, CaV1 and KV2.1 are regulated by a diverse range of mechanisms to generate distinct electrical signals under different physiological and pathological conditions. Ca 2+ /CaM Ca2+/calmodulin, CAC citric acid cycle, EV endocytotic vesicles, G GTP-binding protein, GLUT glucose transporter, GMS glucose metabolism-derived signal, GPCR GTP-binding protein-coupled receptor, IG insulin-containing granule, InsP 3 R InsP3 receptor, P phosphoryl group, PIP 2 phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PLC phospholipase C, PPase protein phosphatase, RyR ryanodine receptor, TKR tyrosine kinase receptor, ψ depolarization

The negatively charged ATP binds Mg2+ with a greater affinity than other cations and thus exists in the cell mostly in a complex with Mg2+ [109, 110]. As stated above, intracellular MgATP predominantly inhibits KATP channels by binding to Kir6.2 subunits, but indeed has a small stimulatory effect on these channels via interaction with SUR1 subunits. Both MgATP and MgADP interact with NBFs of the SUR1 subunits resulting in activation of KATP channels, elevation in the ATP-sensitive K+ conductance and reduction in the excitability of the β cell plasma membrane (Figs. 1, 2). Available data indicate that MgATP does not activate the channel directly and must be hydrolyzed to MgADP that makes the channel open by binding to NBFs of the SUR1 subunit [5, 108]. It is believed that there are two ATP binding pockets, namely sites 1 and 2. Site 1 is formed by the Walker A and Walker B motifs of NBF1 plus the linker motif of NBF2, whereas site 2 is composed of the Walker A and Walker B motifs of NBF2 plus the linker motif of NBF1 (Fig. 2). The latter hydrolyzes bound ATP. In intact cells, the stimulatory effect of Mg-nucleotides decreases the sensitivity to ATP inhibition [5, 108]. This cannot fully explain why intact β cells containing 1–5 mM ATP at rest exhibit significant KATP channel activity and further close KATP channels in response to glucose stimulation. Intracellular free MgADP concentration (about 50 µM) is namely too low to antagonize inhibition of KATP channels by 1–5 mM ATP [108, 111]. Consequently, other endogenous KATP channel openers such as phosphatidylinositols and long-chain acyl-CoA ester may also be considered in this context [108, 111].

Phosphatidylinositols

The lipid bilayer of the cell membrane not only physically hosts KATP channels, but also functionally interacts with these channels (Fig. 5). Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate, PIP2 and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate play important roles in stabilizing open states of KATP channels although these phosphatidylinositols just constitute a minor phospholipid component at the cytosolic side of the cell membranes [4, 5]. Decreases and increases of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate, PIP2 or phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in the cell membrane significantly inhibit and activate KATP channel activity, respectively, by altering the open probability of the channel (Fig. 5) [4, 5, 112, 113]. Intracellular application of PIP2 potently augments the whole-cell KATP conductance. Diminution in the plasma membrane PIP2 by P2Y receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C markedly decreases whole-cell KATP currents. Both heterologously expressed Kir6.2/SUR1 and β cell KATP channels in inside-out patches display a gradual run-down that can be effectively prevented by addition of PIP2 [112, 113]. Molecular and structural analyses indicate that the Kir6.2 subunit possesses a PIP2 binding site adjacent to the ligand-operated gate of the KATP channel. PIP2 occupation of this binding site causes the energetic pull to open the gate and stabilize the channel in an active conformation [5, 97]. Interestingly, PIP2 also potently counteracts the inhibitory effect of ATP on the KATP channel causing a drastic decrease in the ATP sensitivity of the channel [5, 112, 113]. This negative heterotropic interaction between PIP2 and ATP is believed to be due to the juxtaposition and partial overlap of PIP2 binding sites with ATP-binding sites in the Kir6.2 subunit [5]. This adds another explanation to the longstanding dilemma that KATP channels do not close in intact β cells containing 1–5 mM ATP at rest, but close following glucose stimulation.

Actin cytoskeletal network

In addition to phosphatidylinositols in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, the actin cytoskeletal network is also important in sustaining the KATP channel in an active form (Fig. 5) [114]. Actin depolymerizers significantly facilitate the run-down of KATP channel in inside-out patches, whereas actin polymerizers fully impede it. F-actins plus MgATP can evidently restore the activity of run-down KATP channels, but G-actins together with MgATP fail to do so [114].

G protein-coupled receptors

Activation of G protein-coupled receptors mediates autocrine feedback and parasympathetic input to β cells to facilitate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. This occurs, at least in part, due to reduced KATP channel activity resulting from decreased PIP2 and increased [Ca2+]i upon activation of P2Y receptors and muscarinic receptors in the β cell plasma membrane [112, 113, 115–117]. ATP coreleased with insulin serves as an endogenous ligand to activate both P2X and P2Y receptors. The P2Y receptor downstream target KATP channel undergoes closure in response to activation of this purinergic receptor (see “Phosphatidylinositols” for details) [112, 113, 116, 117]. Activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors significantly reduces KATP currents recorded in the rat islet β cell using a perforated-patch whole-cell recording [115]. As a result of the inhibition of KATP channels by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, the β cell becomes strongly depolarized to fire action potentials [115]. The effect is effectively ablated by inhibition of phospholipase C or chelation of intracellular Ca2+. Exposure of KATP channels in inside-out patches to 10 μM Ca2+ significantly reduces channel activity in the presence of ATP [115]. Ca2+ at higher concentrations effectively induces KATP channel rundown in the absence of ATP [114]. Comparatively speaking, the increased [Ca2+]i appears to be more important than the decreased PIP2 in down-regulation of KATP channel activity by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. This is because acetylcholine can no longer inhibit β cell KATP channel activity when the increased [Ca2+]i is prevented without influencing activation of PLC [115].

Protein kinase A

Protein phosphorylation is also a regulatory mechanism for β cell KATP channel conductivity and density (Fig. 5). Protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation of KATP channels and its functional consequences have been firmly verified [118]. At least, two PKA phosphorylation sites (threonine 224 and serine 372) have been verified in the Kir6.2 subunit. PKA catalytic subunits or activation of G protein-coupled receptors can effectively phosphorylate these two residues resulting in a significant increase in channel open probability [118]. The PKA phosphorylation site has also been identified in the SUR1 subunit [118]. The basal PKA activity is sufficient for phosphorylation of the SUR1 subunit at its serine 1571. Such a phosphorylation decreases burst duration, interburst interval and open probability of the KATP channel, but increases the number of the channel in the plasma membrane [118]. Indeed, the above data were obtained in heterologous expression systems and insulin-secreting MIN6 cells subjected to in vitro manipulation of PKA or G protein-coupled receptors. Nevertheless, physiological significances of these in vitro data can be inferred as follows. At basal glucose concentration, autonomic innervation and paracrine feedback loops likely suffice to activate β cell Gs protein-coupled receptors and thereby PKA phosphorylation of KATP channels. Such a KATP channel phosphorylation serves to preserve adequate KATP channel activity to set up the resting membrane potential of the β cell. As aforementioned, ATP concentrations (1–5 mM) in resting β cells could fully block KATP channels if there was no antagonism against such a blocking effect. In addition to stimulation by phosphatidylinositols and MgADP, Gs protein-coupled receptor-dependent PKA phosphorylation of β cell KATP channels is likely to be another mechanism counteracting inhibition of KATP channels by high concentration of ATP in resting β cells.

Interestingly, intracellular KATP channels have been visualized in chromogranin-positive/insulin-negative dense-core granules [73]. Glucose stimulation can recruit these KATP channels to the β cell plasma membrane via these novel secretory granules in a Ca2+- and PKA-dependent manner [73]. It should be pointed out that the increase in PKA activity concomitant with glucose stimulation promotes the recruitment of KATP channels to the β cell plasma membrane, but does not alter KATP channel activity [73]. This suggests that maximal PKA phosphorylation of KATP channels already occurs at basal glucose concentrations due to activation of Gs protein-coupled receptors by neurotransmitters such as adrenaline released from autonomic nerve terminals and hormones e.g., glucagon exocytosed from α cells. Therefore, the glucose-induced activation of PKA promotes secretory granule trafficking and exocytosis but cannot further phosphorylate KATP channels reducing β cell excitability during glucose stimulation. The recruited channels may act as a constituent of the exocytotic machinery to mediate insulin release independent of their electrical function since SUR1 subunits play an essential role in cAMP-dependent/PKA-independent insulin secretion by interacting with cAMP-GEFII, Piccolo, RIM2, Rab3, and CaV1.2 subunits [119]. Taken together, PKA phosphorylation not only regulates KATP channel conductivity, but also promotes its trafficking to the cell surface [4, 73].

Protein kinase C

Protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation regulates both the conductivity and the density of KATP channels in the plasma membrane [120, 121]. Brief activation of PKC results in phosphorylation of threonine 180 of the Kir6.2 subunit [121]. This phosphorylation occurs at Kir6.2Δ26 subunits alone or Kir6.2 associated with SUR1 or SUR2A subunits heterologously expressed in tsA201 cells [121]. It decreases KATP channel activity at lower ATP concentrations, but increases KATP channel activity at higher ATP concentrations [121]. The physiological relevance of the data remains elusive. Prolonged activation of PKC down-regulates the number of Kir6.2/SUR1 channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes or COS-7 cells [120]. Interestingly, this down-regulation still occurs when PKC consensus sites in Kir6.2 are mutated, but disappears when the dileucine motif is depleted from Kir6.2 [120]. This is because the dileucine motif targets its host proteins in the plasma membrane to endosomes by interacting with the AP2 complex, a critical regulator of dynamin-dependent endocytosis. Such endocytosis is vitally controlled by PKC phosphorylation [120]. Apparently, dynamin-dependent endocytosis rather than PKC phosphorylation of Kir6.2 subunits per se mediates the down-regulation of Kir6.2/SUR1 channels [120]. It would be interesting to clarify if down-regulation of β cell KATP channel density occurs in a physiological context where PKC is activated.

Pharmacological blockers

Owing to the importance of the β cell KATP channel in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, this channel has been identified as and proven to be an important therapeutic target in pharmacological treatment of type 2 diabetes and insulin hypersecretion associated with insulinoma and familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy [3, 4]. Both KATP channel blockers and openers have been developed and used to treat these diseases for decades. There are two classes of KATP channel blockers designed for therapeutic use, sulfonylureas and glinides [3, 4]. Although they are structurally dissimilar, they share similar pharmacological actions depending on equivalent mechanisms. Sulfonylureas and glinides function as insulin secretagogues by closing β cell KATP channels and secondarily opening β cell CaV channels. The following discusses β cell KATP channel blockers exemplified by sulphonylureas. The first generation of oral hypoglycemic sulfonylurea agents such as tolbutamide was derived from antibacterial sulfonamides as a consequence of the observations made during World War II, namely, that patients treated with these antibacterials often developed hypoglycemia. However, they are not satisfactorily potent. Therefore, pharmaceutists developed the second generation of sulfonylureas represented by glibenclamide with high potency. Glibenclamide binds to human SUR1 subunits expressed in COS-7 cells 40,000 times more strongly than tolbutamide [122]. The binding affinity and inhibition potency of glibenclamide are 20,000 times and 50,000 times higher than those of tolbutamide, respectively [122]. Glibenclamide is not only a high-potency antidiabetic drug, but also a useful research tool. It was this reagent that fished out its binding partner sulfonylurea receptor for the first time. The sulfonylurea binding site is localized in the intracellular loop between TMD0 and TMD1 of SURx subunits [3, 4]. A detailed picture of the binding site remains to be elucidated.

Pharmacological openers

KATP channel openers are a diverse group of drugs exhibiting a great chemical diversity and pharmacological selectivity. They increase cell membrane permeability to K+ resulting in cell membrane hyperpolarization and consequent inhibition of action potential generation. The well-characterized KATP channel opener diazoxide is commonly used to suppress excessive insulin secretion in patients with insulinoma and familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy by activating β cell KATP channels [3, 4]. The clinical effect of diazoxide depends on selective binding of this drug to the SUR1 subunit. This subunit carries a diazoxide binding site, but its precise location is still uncertain. Domain exchange between diazoxide-sensitive SUR1 and diazoxide-insensitive SUR2A subunits indicates that the TMD1 plus NBF1 from the SUR1 subunit is responsible for diazoxide binding [3, 4].

Ca2+ influx through β cell CaV channels mainly controls insulin secretion

Like other ion channel-mediated ion fluxes, Ca2+ influx through CaV channels alters the cell membrane potential. It contributes to the upstroke of the action potential in certain types of excitable cells. The pancreatic β cell is one of the excitable cells employing CaV channels in the generation of action potentials. During action potentials, the CaV channel-mediated Ca2+ influx into the β cell mainly controls insulin secretion although it is also involved in the regulation of other β cell functions [7, 8, 14, 123, 124]. The major β cell CaV channel CaV1 opens immediately when the β cell plasma membrane is depolarized to the firing threshold of action potentials following stimulation with high glucose (Fig. 1). Ca2+ entry through CaV1 channels leads to a rapid further depolarization of the β cell plasma membrane, namely the upstroke or depolarization phase of the action potential manifested as a rapid increase in the CaV1 conductance (gCaV1) (Fig. 1).

Structure, classification and properties of β cell CaV channels

The CaV channel is a multiple protein complex containing the CaVα1, CaVα2/δ, CaVβ and CaVγ subunits (Fig. 3) [8, 125–130]. The CaVα1 subunit as the principal element of the CaV channel complex constitutes a pore structure to conduct Ca2+ in response to membrane depolarization (Fig. 3). The CaVα2/δ, CaVβ and CaVγ subunit do not directly contribute to building up the Ca2+-conducting pore, but are intimately associated with the CaVα1 subunit to regulate its conductivity and trafficking. Therefore, they are referred to as auxiliary subunits (Fig. 3) [8, 125, 126]. Ten CaVα1 subunits, CaV1.1, CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV1.4, CaV2.1, CaV2.2, CaV2.3, CaV3.1, CaV3.2 and CaV3.3, have been characterized (Fig. 3). They associate with certain auxiliary subunits to mediate L-, P/Q-, N-, R- and T-type CaV currents, respectively (Fig. 3) [8, 125]. In general, all these types of CaV currents are recorded in β cells. They are conducted by CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV2.1, CaV2.2, CaV2.3, CaV3.1 and CaV3.2 subunits in combination with certain auxiliary subunits [7, 8, 11]. However, obvious interspecies differences in expression of CaV currents have been revealed in the β cell [7, 8]. For example, CaV3 currents are clearly visualized in the human and rat β cell, but not in the mouse β cell. CaV2.3 channels are not present in the human β cell [7, 8, 11, 13, 131].

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of a CaV channel. a The CaV channel subunit complex in the plasma membrane. The pore-forming subunit CaVα1 associates with regulatory subunits CaVβ, CaVγ, and CaVα2δ to assemble into functional CaV channels in the plasma membrane. b Transmembrane topology of CaV channel subunits. The CaVα1 subunit contains four homologous transmembrane domains (I to IV), each containing six transmembrane segments and a membrane-associated loop between transmembrane segments 5 and 6, three intracellular linkers, and intracellular N- and C-termini. The CaVβ subunit is entirely cytosolic. The CaVγ subunit comprises a conserved four-transmembrane domain, and intracellular N and C termini. The CaVα2δ subunit is a two-peptide dimer linked by disulfide bonds. The CaVα2 is an entirely extracellular polypeptide, and the CaVδ possesses a single transmembrane domain with a very short intracellular C-terminus and long extracellular portion. In mammalian genomes, ten CaVα1 subunits, four CaVβ subunits, four CaVα2δ subunits, and eight CaVγ subunits have been identified. They form distinct types of CaV channels in different cell types and mediate L-, P/Q-, N-, R- and T-type CaV currents, respectively. The β cells display all these types of CaV currents that are conducted by CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV2.1, CaV2.2, CaV2.3, CaV3.1 and CaV3.2 subunits in combination with certain auxiliary subunits. CaV1 channels dominate over the other types in the β cell

The CaVα1 subunit possesses four homologous domains, each consisting of six transmembrane segments (S1 to S6) and a membrane-associated pore loop (P-loop) between the S5 and S6 segments, three intracellular linkers, and N- and C-termini. The four homologous domains are structured into a Ca2+-conducting pore equipped with activation and inactivation gates and controlled by voltage sensors. Four pairs of the S5 and S6 segments along with the P-loops line the Ca2+-conducting pore. The Ca2+ selectivity of the pore relies on four glutamic acid residues situated in the four P-loops of high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels or two glutamic and two aspartic acid residues localized in the corresponding positions of low voltage activated Ca2+ channels. The S4 segments function as the principal voltage sensors in CaV channels. The depolarization-evoked movement of the voltage sensors results in the conformational change and/or physical reposition of activation and inactivation gates to open the channel and to reduce channel permeability, respectively [7, 8, 93, 125].

Three-dimensional structures of CaV channels have been partially depicted by electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography. Single-particle electron microscopy shows that CaV1.2 channels purified from bovine heart and expressed in β cells are complexed to a stable dimer consisting of two arch-shaped monomers [7, 8, 132]. This complex is composed of CaVα1, α2, β and δ subunits and is roughly toroidal in shape (19 nm in height, 19 nm in width and 14.5 nm in depth). The two arches contact at the extracellular and intracellular sides of the complex. The top end of the complex is termed the nose, whereas the bottom end of the complex is occupied by CaVβ subunits. There are two finger-like protrusions, i.e., finger domains, extending from the two arches that curl around on each side to the front and back side of the toroidal complex. The nose and finger domains are mainly formed by CaVα2 subunits. The two arches and two finger domains enclose a central aqueous chamber with a ~5 nm × 3 nm × 4 nm volume (height × width × depth) [132]. Recently, X-ray crystallography in combination with patch-clamp analysis has clearly dissected the structure–function relationships of the Ca2+ selectivity filter of CaV channels [133]. This filter is made of two high-affinity and one low affinity Ca2+-binding sites named Site 1 (high-affinity), Site 2 (high-affinity) and Site 3 (low affinity) from the extracellular to the intracellular side. Hydrated Ca2+ interacts with Sites 1 and 2 followed by Site 3 when passing through the filter. The interaction between these Ca2+-binding sites via a knock-off mechanism drives transient changes of the selectivity filter between two states with either one hydrated Ca2+ bound at site 2 or two hydrated Ca2+ ions bound at sites 1 and 3. The high-affinity binding of Ca2+ to Sites 1 and 2 prevents permeation of Na+ and other monovalent cations and high extracellular Ca2+ enables its inward movement by rapidly binding to Site 1. The ionic repulsion between Ca2+ ions bound at these sites cooperates with the stepwise change in Ca2+ binding affinity of these sites to guarantee rapid conductance despite of the intrinsic high affinity for Ca2+ binding [133]. The complex of the α1-interaction domain (AID) in the CaVα1 subunit with the CaVβ subunit has been visualized at the atomic level [134, 135]. The CaVβ subunit core is structured by a SH3 domain and a GK domain. The latter holds a hydrophobic groove which binds the α-helical AID. This provides the CaVβ subunit with the ability to directly modulate the movement of the IS6 segment in the CaVα1 subunit influencing channel pore gating, since the AID helix N-terminus is very close to the pore-lining segment IS6 [134, 135].

Combination of conventional whole-cell patch-clamp analysis and pharmacological manipulation reveals that CaV1, CaV2.1 and CaV2.3 channels mediate 50, 10–15 and 25 % of the integrated whole-cell CaV current, respectively, in the mouse β cell [131, 136]. The mouse β cell CaV current activates at around −50 mV, reaches peak amplitude (about 50 pA) between −10 and +10 mV, inactivates slowly and reverses at about +50 mV [7, 8, 137]. This reversal potential deviates somewhat from the Ca2+ equilibrium potential due to the presence of other ions [7, 8, 137]. The mouse β cell CaV current at −10 mV activates with a time constant of 1.28 ± 0.08 ms [137]. The same experimental approach has also been used to characterize whole-cell CaV currents in the human β cell [11, 13, 131]. The human β cell CaV current appears at potentials positive to −60 mV and reaches its peak density of 14 pA/pF at 0 mV, undergoes obvious inactivation and reverses at about +50 mV [11, 13, 131]. It activates with a time constant of 0.41 ± 0.02 ms at 0 mV and biphasically inactivates with a fast time constant of 6.8 ± 0.4 ms and a slow time constant of 65 ± 15 ms [11]. The human β cell engages CaV1, CaV2.1 and CaV3.2 channels to mediate CaV currents. CaV1 and CaV2.1 channels make an equal contribution (40–45 %) to the integrated whole-cell CaV current, whereas CaV3.2 channels only marginally contribute to a transient component (6 %) of the integrated whole-cell CaV current [11, 13, 131]. CaV3.2 channels activate at potentials positive to −60 mV, conduct maximal inward Ca2+ currents at −30 mV and undergo voltage-dependent inactivation with a half-maximal voltage of −65 mV and a time constant of about 40 ms at potentials positive to −50 mV [11, 13, 131]. CaV1 currents become detectable at −40 mV and peak between −20 and −10 mV, whereas CaV2.1 channels became active at −20 mV and conduct a maximal inward Ca2+ currents at 0 mV [11, 13, 131]. Both CaV1 and CaV2.1 currents activate quickly and can peak within less than 5 ms [11, 13, 131]. Noteworthy is that CaV1 channels rather than CaV2.1 channels inactivate in a Ca2+-dependent way with a time constant of 40 ms at 0 mV [11, 13, 131].

Regulation of insulin secretion by Ca2+ influx through β cell CaV channels

It is likely that all types of β cell CaV channels participate in the regulation of insulin secretion [7, 8, 14]. Ca2+ influx through β cell CaV1 channels plays a predominant role in control of insulin secretion over that mediated by other types of β cell CaV channels. It is responsible for 60–80 % of glucose-induced insulin secretion from mouse and rat islets and regulates both phases of insulin secretion, but more prominently the first phase [8, 136, 138]. Ca2+ entry through CaV2.1 channels is second only to that through CaV1 channels in the control of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in rodents [8]. CaV2.1 channels are the most important in regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in human β cells [11, 131]. It is still a matter of debate whether the CaV2.2 channel-mediated Ca2+ entry participates in the regulation of insulin secretion [8]. It has been shown that the CaV2.2 channel blocker ω-CTX GVIA produces the null effect on glucose-induced insulin secretion in human islets. On the contrary, this blocker has been observed to inhibit second phase glucose-induced insulin secretion from rat islets [8]. Both pharmacological blockade of the CaV2.3 channel and genetic ablation of the CaV2.3 subunit firmly confirm the important role of CaV2.3 channels in insulin secretion [14, 139]. Detailed analysis reveals that Ca2+ influx through CaV2.3 channels selectively contributes to the regulation of second phase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion without affecting the first phase [14, 139]. It is tempting to speculate that β cell CaV1 channels self-organize into triplets and physically associate with syntaxin 1 and SNAP-25 to form local high [Ca2+]i-driven exocytotic sites, whereas CaV2 channel-mediated Ca2+ influx contributes to global [Ca2+]i to recruit insulin granules to exocytotic sites [131, 140]. The differential localization and organization of CaV1 and CaV2 channels provide a reasonable explanation for selective regulation of first and second phase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by CaV1 and CaV2 channels [131, 140].

The regulation of insulin secretion by the CaV3 channel-mediated Ca2+ entry has been demonstrated in INS-1 cells [8, 141]. It is, however, uncertain that it occurs also in primary β cells although the non-selective CaV channel antagonist flunarizine, inhibiting both CaV1 and CaV3 channels, attenuates glucose- as well as K+-induced insulin secretion from perifused rat islets [8, 142].

Regulation of β cell CaV channels

Although the membrane potential determines the extent to which β cell CaV channels open, the conductivity and density of these channels are regulated by a diverse range of mechanisms that alter β cell CaV channel function and in particular Ca2+-dependent insulin secretion (Fig. 5) [7, 8, 14]. Generally speaking, these regulatory mechanisms coordinate with each other to drive adequate insulin secretion in the context of physiology [7, 8]. One or some of them predominate over others in a particular scenario [7, 8]. For example, parasympathetic activity and blood glucagon-like peptide-1 levels increase during food ingestion [7, 8]. They activate muscarinic receptors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors, respectively. This synchronous activation upregulates β cell CaV channel activity through stimulation of PKA and PKC and facilitates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [7, 8]. Obviously, the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor- and muscarinic receptor-mediated up-regulation of β cell CaV channel activity is more important than other mechanisms during food ingestion. We discuss different types of important regulatory mechanisms of β cell CaV channels below.

Protein kinases

β cell CaV channels carry multiple protein phosphorylation sites. Therefore, their Ca2+ conductivities are regulated by protein kinases and protein phosphatases (Fig. 5) [8]. It is clear that activation of PKA enhances the activity of β cell CaV1 channels [8, 143–146]. However, activation of PKC produces complicated effects on β cell CaV channels [147–149]. For example, depletion of PKC down-regulates L-, P/Q- and non-N-type CaV currents to the same extent in insulin-secreting RINm5F cells. Acute activation of PKC marginally increases CaV currents only in a small proportion of RINm5F cells (24 %). The effect occurs predominantly to CaV1 channels [8]. The PKG activator cGMP increases Ca2+ influx through CaV1 channels in rat pancreatic β cells [150]. However, it is uncertain that this effect results from activation of PKG since cGMP can produce a direct effect on CaV channels bypassing PKG [8, 151]. Likewise, it is not clear if calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) regulates β cell CaV channel activity. Indeed, the non-specific CaMKII inhibitors KN-62 and KN-93 inhibit Ca2+ influx through β cell CaV channels [152, 153]. However, they may bypass CaMKII to directly act on β cell CaV channels [8]. Inhibition of protein phosphatases with okadaic acid just produces a smaller increase under basal conditions, but a larger increase in CaV channel activity on top of activation of PKA in mouse pancreatic β cells [154]. This means that the phosphorylation state of mouse β cell CaV channels under basal conditions is low [8].

β cell CaV channels are also regulated by tyrosine kinase receptors (Fig. 5) [8, 155–158]. The nerve growth factor signaling pathway is involved in β cell CaV channel regulation [8, 155, 156]. Long-term incubation (5–7 days) with nerve growth factor increases the density of CaV1 channels in the β cell plasma membrane, whereas the acute action of this nerve growth factor makes these channels more active [8, 155, 156]. Activation of insulin receptors with the insulin mimetic L-783,281 raises cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in the mouse pancreatic β cell. The effect is significantly diminished by CaV1 channel blocker and absent in insulin receptor substrate-1-knockout β cells [8, 158]. However, the effect of acute activation of insulin receptors on β cell CaV channel activity has not been confirmed by patch-clamp analysis [8].

G protein-coupled receptors

The β cell is equipped with various G protein-coupled receptors, such as glucagon, glucagon-like peptide-1, somatostatin, opioid, galanin, adrenergic and muscarinic receptors [8, 159–177]. These receptors employ their partner G proteins as a brake on β cell CaV channel activity through physical association of G proteins with CaV channel pore-forming subunits (Fig. 5). They also regulate β cell CaV channel activity by manipulating protein kinases and second messengers (Fig. 5). Activation of glucagon, glucagon-like peptide-1 and opioid receptors enhances β cell CaV channel activity, whereas stimulation of galanin and α2-adrenergic receptors reduces it. With regard to muscarinic receptors, their activation can either enhance or reduce β cell CaV channel activity dependent on cell types [8].

Exocytotic proteins

β Cell CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 channels physically associate with exocytotic proteins such as syntaxin 1A, SNAP-25 and synaptotagmin [178, 179]. The association of β cell CaV channels with exocytotic proteins functions as an exocytotic signalosome in β cells. Such an exocytotic signalosome transduces bidirectional signaling to fine-tune both β cell CaV1 channel activity and exocytotic protein interaction affinity [8, 178–180]. CaV channels not only serve as Ca2+ conduits to control insulin secretion via their mediated Ca2+ entry, but also as signaling devices to regulate the insulin secretory process independent of Ca2+ influx [63, 181, 182]. The conformational change of the CaV1.2 subunit, driven by Ca2+ binding and depolarization, can instantaneously signal to the exocytotic machinery to release an appreciable amount of insulin prior to Ca2+ influx. This innovative view is supported by the following findings. The inorganic CaV1 channel blocker La3+, which blocks Ca2+ influx by binding to the polyglutamate motif (EEEE) in the selectivity filter, significantly supports glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from rat pancreatic islets and ATP release in INS-1E cells. The effect is independent of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and abolished by the organic CaV1 channel blocker nifedipine. This means that La3+ binding to the EEEE motif is sufficient to support glucose-stimulated insulin secretion at the very early phase [181, 182]. Intriguingly, the CaVβ3 subunit is not likely to be a necessary building blocker of β cell CaV channels. Instead, it interacts with the intracellular Ca2+ release machinery serving as a brake of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-mediated Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores in the β cell and thus negatively regulates insulin secretion [63].

Glucose metabolism-derived signals

Glucose metabolism activates a range of β cell signaling pathways that possibly participate in the regulation of β cell CaV channels (Fig. 5). It seems that acute administration of high glucose increases β cell CaV channel activity [183]. Chronic exposure to high or low glucose inhibits expression of β cell CaV channels [8, 184, 185]. Glucose- or K+ depolarization-induced elevation in intracellular inositol hexakisphosphate acts as a critical mechanism for regulation of a variety of molecular and cellular functions including β cell CaV1 channel activity [7, 8, 186–193]. Elevated inositol hexakisphosphate enhances β cell CaV1 channel activity through inhibition of protein phosphatases and/or activation of the adenylyl cyclase-PKA cascade [189, 194]. Alterations in inositol polyphosphates in a β cell line lead to the up-regulation of CaV1 channel activity [195].

Components in blood plasma

In addition to glucose, several other components in blood plasma can regulate β cell CaV channels (Fig. 5). The serum protein transthyretin significantly increases β cell CaV channel activity and plays an important role in maintaining β cell function [196]. Free fatty acids act as regulators of β cell CaV channels. The most abundant saturated plasma free fatty acid palmitate produces dual effects on β cell CaV currents, namely stimulatory at lower and inhibitory at higher concentrations [197]. Cholesterol also regulates β cell CaV channels in two opposite directions [198, 199]. Chronic inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis significantly reduces cholesterol in β cells. The resultant reduction of β cell cholesterol leads to a significant decrease in both β cell CaV channel activity and insulin exocytosis. The effect is effectively reversed by cholesterol repletion [199]. Exposure of mouse β cells to cholesterol-rich medium not only decreases glucose-stimulated mitochondrial ATP production, but also reduces β cell CaV channel activity [198]. These studies pinpoint that the β cell needs the appropriate amount of cholesterol and free fatty acids in blood plasma for its optimal function.

Ca2+ controls almost all known molecular and cellular events in the β cell