Abstract

An ever-increasing number of studies highlight the role of uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in a broad range of physiological and pathological processes. The knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of UCP2 regulation is becoming fundamental in both the comprehension of UCP2-related physiological events and the identification of novel therapeutic strategies based on UCP2 modulation. The study of UCP2 regulation is a fast-moving field. Recently, several research groups have made a great effort to thoroughly understand the various molecular mechanisms at the basis of UCP2 regulation. In this review, we describe novel findings concerning events that can occur in a concerted manner at various levels: Ucp2 gene mutation (single nucleotide polymorphisms), UCP2 mRNA and protein expression (transcriptional, translational, and protein turn-over regulation), UCP2 proton conductance (ligands and post-transcriptional modifications), and nutritional and pharmacological regulation of UCP2.

Keywords: UCP2, Mitochondrial uncoupling, Regulation

Introduction

UCP superfamily, ion transport, and uncoupling activity

Mitochondria are the source of power of eukaryotic cells by virtue of their ability to control substrate degradation and to produce high-yield ATP production. This process is known as oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and allows electrons derived from various substrates to move along multi-subunit enzyme complexes of the electron transport chain embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane. The reaction series culminate in the reduction of molecular oxygen at the level of complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) and the free energy difference is converted into an electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane by translocating protons from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space. Controlled return of protons into the matrix by the FoF1 ATP synthase drives the conversion of ADP into ATP. Importantly, conversion of substrate energy into ATP (‘coupling’) is not perfect and a considerable portion of free energy produced in the process may be lost as heat [1]. This event is associated to a wasteful proton backflow by the action of specialized mitochondrial carriers termed uncoupling proteins (UCPs) [2]. Thus far, five UCPs have been discovered in mammals [3]. The closely related UCPs are UCP1–UCP3. UCP1 is mainly expressed in brown adipose tissue and UCP3 in muscle and adipose tissues, whereas UCP2 has been found in several tissues, such as liver, brain, pancreas, adipose tissue, immune cells, spleen, kidney, and the central nervous system [4–9]. The other two members, UCP4 and UCP5, are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and are involved in mitochondrial membrane potential reduction [10]. It has been proposed that the structure of UCPs could be comparable to that of the ATP/ADP carrier (ANT) protein [11, 12]. All five UCPs and ANT share a common tripartite structure that consists of three repeat domains each with two hydrophobic α-helical transmembrane subdomains spanning the mitochondrial inner membrane [13]. The two helices within each repeat domain are linked by a long loop that is oriented on the matrix side of the membrane. Furthermore, sequence alignment and analysis of transmembrane domains suggest that UCPs 1–3 on one hand and UCPs 4 and 5 on the other belong to separate subfamilies [14]. It has been speculated that UCP4 might represent the ancestral UCP from which the other invertebrate, mammalian, and plant UCPs diverged. Phylogenetically, UCPs 1–3 possibly arose later during evolution and hence are likely to execute more specialized functions [15]. UCP1 is an important regulator of adaptive thermogenesis in mammals [16], while UCP2 and UCP3 can dissipate the proton gradient to prevent the proton-motive force from becoming excessive, thus decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by electron transport [17]. Indeed, UCP2 acts as a sensor of mitochondrial oxidative stress and its function is an important component of local feedback mechanisms controlling the production of mitochondrial ROS. As revealed by studies with UCP2-null mice, its antioxidant function is generally implicated in cyto-protective activities [18, 19].

In addition to proton, UCPs has been described to mediate transport of anions (such as Cl−, Br−, and NO3 −) across the mitochondrial inner membrane [20]. Thereafter, Hoang et al. [21], by using recombinant neuronal UCPs reconstituted into a liposome system, demonstrated an accumulation of positively charged residues at the bottom of the funnel-like structure close to the inner side of the vesicles. They suggested that small anions such as chloride could migrate from the cytoplasmic side and potentially accumulate through electrostatic interactions in the vicinity of the positively charged region located at the protein–matrix interface. This accumulation of small anions could induce local conformational changes in UCPs causing a channel-like opening and anion flux across the membrane. Thus, on the basis of the above described and other recent experimental evidences showing ion channel properties of UCPs [11], it would be conceivable that there is a hypothetical coexistence of inter-convertible fatty acid-mediated carrier (see “Regulation of proton conductance”) and channel modes as a mechanism for ion transport in UCPs.

However, despite UCP2 having been described to uncouple the respiratory chain from ATP synthesis by dissipating the proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane and despite it being phylogenetically a component of the UCP superfamily [22], its status as a functional UCP is much in doubt by several research groups. For instance, Couplan et al. [23] failed to observe any difference in the proton leak between wild-type and UCP2 knockout mice, when examining mitochondria from lung or spleen, the two organs expressing the highest level of UCP2. Furthermore, no consistent correlation between UCP2 (or UCP3) expression and increase in energy expenditure [24], as well as no increase in the ATP/ADP ratio in lung or spleen isolated mitochondria from Ucp2(−/−) mice, have been reported [23]. These results are in contrast with those obtained in pancreatic islets of Ucp2(−/−) mice where the absence of UCP2 was accompanied by an increased ATP level and higher insulin secretion [25]. Pecqueur et al. [26] showed that UCP2 promotes mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation while limiting mitochondrial catabolism of pyruvate, suggesting that the metabolic and proliferative alterations triggered by UCP2 have to be explained by an activity distinct from uncoupling. Altogether, the above-described contradictory data persuaded some authors that UCP2 does not uncouple at all [23, 26–32]. At present, some of the conflicting observations may be explained, at least partially, by the following considerations: because of the low amount of UCP2 found in mitochondria, it is technically hard to highlight its uncoupling activity; UCP2 uncoupling activity may need activation to display its uncoupling properties; and UCP2 recombinant expression systems may favor artifacts leading to nonspecific uncoupling of mitochondria. Furthermore, some discrepancies between studies performed with isolated mitochondria and with living cells could be explained by the hypothesis that, for some reason, the proton transport activity of UCP2 in isolated mitochondria could not be evidenced. Thus, despite the multiplicity of proton leakage pathways in mitochondria rendering difficult the identification of a single molecular determinant of the proton leakage pathways, stronger efforts need to be performed to finally clarify the uncoupling role of UCP2.

Pathological implications of UCP2

The wide tissue distribution of UCP2 means that its regulation has a role in several physiologic or pathologic events on the basis of the specific tissue/organ implicated. Among others, UCP2 can be involved in the regulation of atherosclerotic plaque formation [33, 34], in the immune response [5, 35, 36], in food intake, and in metabolic diseases [4, 37]. Thus, given its central role in regulating cellular energy transduction and mitochondrial ROS production, UCP2 may provide an attractive therapeutic target for diseases rooted in metabolic imbalance and oxidative damage.

Furthermore, several studies have established the key role that UCP2 has in tumorigenesis and in chemoresistance: the generally accepted assumption envisages that, during tumorigenesis, UCP2 is repressed to enhance oxidative stress, while it is activated or over-expressed in the subsequent stages of cancer development, determining chemoresistance and tumor aggressiveness by protecting cancer cells from apoptosis through the negative regulation of mitochondrial ROS production [38–42]. Accordingly, Derdak et al. [43] found that UCP2-null mice have a predisposition for enhanced tumorigenesis in the proximal colon, providing the first in vivo evidence for a link between mitochondrial UCPs and cancer, while another study revealed that highly expressed UCP2 is associated with colon cancer metastasis and tumor aggressiveness [44]. The dual regulation of UCP2 expression in the different stages of tumor development has also been demonstrated in breast cancer. In agreement with the knowledge that estrogens are a major risk factor for breast cancer initiation [45], and with the observation that mitochondria are the main source of estrogen-induced ROS in breast cancer cells [46], Sastre-Serra et al. [47] demonstrated that repression of UCPs by estrogens may play a key role in estrogen-induced breast carcinogenesis. On the other hand, over-expression of the antioxidant UCP2 has a function in breast cancer progression, in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that UCP2 over-expression in tumors may be a common phenomenon stimulating tumor progression, and it may serve as a promising antitumoral therapeutic target [48]. Intriguingly, Sayeed et al. [49] reported a significant association between UCP2 and tumor grade in primary breast cancer (n = 234), showing a synergistic link between UCP2 and established cellular pathways in conferring grade-associated functional phenotypes. They demonstrated that transcriptional repression of UCP2 by TGFβ-induced SMAD4 recruitment to the UCP2 promoter is associated with the conversion from well to moderately differentiated primary tumor cell lines, while abnormal UCP2 over-expression and consequent decrease of endogenous oxidative stress are observed in poorly differentiated tumor cells, known to be TGFβ-resistant. Interestingly, the contribution of UCP2 expression in cancer cells may also be associated with the inhibition of the pro-apoptotic p53 translocation to mitochondria by dissipation of the mitochondrial potential [50]. The authors suggested that UCP2 over-expression in cancer progression may be a result of a long-term selecting procedure, since any de-regulation that results in UCP2 up-regulation could help cancer cells to escape from p53-mediated apoptosis.

Recently, our research group demonstrated that UCP2 can be considered a valuable antiproliferative target in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. We observed that mitochondrial uncoupling by UCP2 is a mechanism of cancer cell resistance to the standard chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine by regulating mitochondrial superoxide production [51], and that UCP2 inhibition has a synergistic antiproliferative effect with gemcitabine in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Moreover, we demonstrated that UCP2 inhibition triggers ROS-dependent nuclear translocation of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH and autophagic cell death [52], which confirmed UCP2 involvement in autophagy regulation previously demonstrated by Pecqueur et al. [26] in a non-tumoral experimental system. Furthermore, Mailloux et al. [53] demonstrated that the chemical inhibition of UCP2 with genipin sensitizes multidrug-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cell lines to cytotoxic agents. In an article published in 1956, Otto Warburg [54] presented a reasoned hypothesis suggesting that the metabolic respiration of cancer cells was damaged and that this resulted in their pro-glycolytic phenotype even in the presence of oxygen. In recent years, Samudio et al. [55] demonstrated that the Warburg effect in leukemia–stroma cocultures is also mediated by induction of an energetically futile OXPHOS pathway in cancer cells via mitochondrial UCP2 activation, suggesting that paracrine effectors may activate basal levels of UCP2 to favor the short circuit of the mitochondrial electrochemical gradient. The authors showed that UCP2 induction by stromal microenvironment can contribute to increasing aerobic glycolysis in leukemia cells, providing the first demonstration that microenvironment also plays a role in the promotion and/or maintenance of the Warburg effect in cancer cells.

Regulation of UCP2

The regulation of UCP2 can occur in a concerted manner at various levels: Ucp2 gene mutation (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNP), UCP2 mRNA and protein expression (transcriptional, translational, and protein turn-over regulation), UCP2 proton conductance (ligands and post-transcriptional modifications), and nutritional and pharmacological UCP2 regulation. The novel findings concerning the molecular mechanisms of all these aspects are thoroughly described in this section.

Ucp2 gene polymorphisms

During the last few years, a large number of studies based on the analysis of frequent Ucp2 genetic variants have identified two of the most common polymorphisms of this gene: the promoter variant −866G>A (rs659366) and the missense polymorphism in codon 55 changing an alanine to a valine (Ala55Val, rs660339) [56]. The identified relative mean frequency is 37 % for −866G>A and 39.6 % for Ala55Val [56]. The impact of Ucp2 polymorphisms on different diseases, such as obesity, body-weight gain, type 2 diabetes (T2D), myocardial infarction, multiple sclerosis and other diseases, has been determined in many studies. We summarize in Table 1 the relationship between the different Ucp2 polymorphisms and various diseases, and the most relevant are described below.

Table 1.

Relationship between UCP2 polymorphisms and various diseases

| Polymorphism | Biological effect | Disease | Total subjects studied | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −866G>A (rs659366) | Higher UCP2 mRNA expression | Abdominal obesity | 2,367 | [80] |

| Obesity and hyperinsulinemia | 440 | [62] | ||

| Obesity treated with sibutramine | 131 | [81] | ||

| Diabetes and miocardial infraction | 901 | [67] | ||

| Obesity and T2D | 17,636 | [63] | ||

| Childhood obesity and metabolic disorders | 200 | [82] | ||

| T2D treated with rosiglitazone | 354 | [61] | ||

| T2D and high-sensitivity C reactive protein | 383 | [59] | ||

| T2D and coronary artery disease | 464 | [83] | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | 188 | [84] | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | 697 | [85] | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | 1097 | [86] | ||

| Chronic inflammation | ND | [87] | ||

| Hyperglycaemia in severe sepsis | 120 + 103 | [88] | ||

| T2D and LTL | About 1,000 | [89] | ||

| Stroke | 2,372 | [90] | ||

| Longevity | 598 | [74] | ||

| Ala55Val (rs660339) | Lower degree of uncoupling | Abdominal obesity | 2,367 | [80] |

| T2D | 1,406 | [70] | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | 697 | [85] | ||

| Weight regulation | 234 | [71] | ||

| Body fat and leptin levels | 150 | [73] | ||

| Morbid obesity | 304 | [72] | ||

| High acute insulin response to glucose | 155 | [69] | ||

| Longevity | 598 | [74] | ||

| −5331G>A | ND | T2D | 1,393 | [75] |

| Exon 8 deletion/deletion | ND | Fat tissue accumulation during PD | ND | [76] |

| Fat tissue accumulation during PD | 41 | [91] | ||

| 45 bp insertion/deletion in 3′UTR | ND | Obesity | 988 | [78] |

| Neural tube defects | 391 | [92] |

T2D type 2 diabetes, LTL leukocyte telomere length, PD peritoneal dialysis, ND not determined

−866G>A polymorphism

−866G>A is a functional polymorphism located in the proximal promoter region of the Ucp2 gene and putatively changes one or more transcription factor binding sites [57, 58]. In many studies, it has been demonstrated that the G allele is associated with lower UCP2 mRNA expression levels, suggesting a reduced protection against ROS production [59]. Indeed, Sesti et al. [60] demonstrated that increased level of UCP2 mRNA given by the presence of the A-allele translates into increased UCP2 protein, induced proton leakage, decreased ATP/ADP ratio, and decreased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). Furthermore, Yang et al. [61] observed that −866G>A polymorphism, associated with Trp64Arg mutation in β3-adrenergic receptor, is linked with the therapeutic efficacy of the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone, in Chinese T2D patients. On the other hand, since there has been evidence supporting a role for Ucp2 −866G>A polymorphism in the development of obesity and related metabolic disorders [62], Andersen et al. [63] performed the largest meta-analysis study so far about this variant using more than 17,000 Danish subjects and demonstrated that the −866G>A allele is associated with obesity and decreased insulin levels. Concerning the association of this polymorphism with an increased risk of chronic inflammatory diseases, Lapice et al. [59] demonstrated in T2D patients that the G allele is associated with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein plasma levels in diabetic patients in a gene dose–effect, thus showing a higher inflammatory status in carriers of the GG genotype compared to carriers of the AA/AG genotype. Furthermore, in 279 general Japanese subjects, it has been found that the −866 A/A genotype is associated with reduced LDL particle size, an event considered a significant risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease, in the absence of any variation in triglyceride, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and small dense LDL levels between genotypes [64]. Accordingly, LDL particles with a reduced size are described to be easily oxidized [65], thus increasing the atherosclerotic burden [66]. Altogether, these observations may be useful in the early identification of subjects susceptible to reduction in LDL particle size and coronary artery disease. Accordingly, another study made on 901 post-myocardial infarction patients indicated that −866G>A polymorphism may be considered a marker of cardiovascular risk and a potential marker of prognosis in T2D patients following acute myocardial infarction [67]. However, the analysis of all these studies revealed that ethnic differences, lifestyle, environmental and genomic factors, age, gender, and nutritional characteristics of the populations may result in extremely different effects of this polymorphism on obesity, T2D, lipid metabolism, and heart diseases.

Ala55Val polymorphism

The Ucp2 Ala55Val polymorphism is a missense variant in the exon 4 of the Ucp2 gene. It is associated with a lower degree of uncoupling, lower energy expenditure, higher risk of obesity, and higher incidence of diabetes [68]. Although Ala55Val polymorphism has been found to be associated with increased body mass index and incidence of T2D in multiethnic populations, several further studies have been addressed to evaluate its role on metabolic disease incidence in specific ethnic groups. In particular, Ala55Val polymorphism has been found to be significantly associated with increased insulin secretion in European–American women [69] and with a reduced risk of developing T2D in Asian Indians [70]. To definitely clarify the relationship between this Ucp2 polymorphism and diabetes risk in humans, Xu et al. [68] examined 17 articles (published from 1998 to 2011) with different outcomes from populations of different ethnic origins, concluding that Ala55Val polymorphism may be a risk factor for susceptibility to T2D in individuals of Asian descent, but not in individuals of European descent. The reason for this is unclear, but it may be that populations of different ethnicity also have environment/habit differences that affect their sensitivity to particular genomic variants.

Regarding weight gain, Heidema et al. [71] investigated the effects of the association of Ucp2 Ala55Val polymorphism with polymorphisms of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). They demonstrated that Ala55Val polymorphism strongly potentiates weight gain induced by CNTF and/or IL-6 polymorphisms. Although it has been shown that Ucp2 polymorphisms participate in the regulation of leptin-mediated food intake and Ala55Val polymorphism appears to exert an effect on obesity development [72] and on circulating leptin levels [73], Heidema et al. [71] demonstrated that weight gain induced by Ala55Val polymorphism occurs in a circulating leptin-independent manner.

Finally, Ala55Val polymorphism has also been found to be associated with two Ucp3 polymorphisms, rs1800849 (−55 C/T) and rs15763, which are significantly related to longevity [74]. This confirms the importance of energy use and modulation of ROS production in the aging process, and, on the basis of the different localization of these UCPs, suggests that the uncoupling process plays an important role in modulating aging especially in muscular and nervous tissues, which are indeed very responsive to metabolic alterations and are very important in estimating health status and survival in the elderly.

Other polymorphisms and mutations

Several studies correlate other UCP2 polymorphisms with different diseases. For example, Lee et al. [75] examined the effect of 23 SNPs in the Ucp2 gene on T2D and showed that patients with combinations of Ucp2 −5331G>A and Ucp3 −2078 C>T polymorphisms have an increased risk for T2D. In advanced chronic kidney disease, Ucp2 exon 8 deletion/deletion has been found to be significantly associated with the enhancement of body fat mass during peritoneal dialysis [76]. Moreover, significant correlations have been demonstrated between rare Ucp2 variants (G174D and A268G) and the promotion of insulin secretion [77], the 45 base-pair insertion/deletion in the 3′ untranslated region and an increased risk of developing obesity [78], or a novel alternative spliced variant of UCP2 (termed UCP-2as) and a tumor progression effect in osteogenic sarcoma [79].

Transcriptional regulation

Transcription factor binding sites of the UCP2 promoter

The gene encoding Ucp2 is located on chromosome 7 in mice [93] and chromosome 11 in humans [94] and contains eight exons and seven introns, spanning an 8- and 6.3-kb region, respectively. The transcription unit of Ucp2 gene is composed of two non-coding exons followed by six exons encoding the UCP2 protein. The analysis of the human and mouse Ucp2 promoter regions reveals the presence of several transcription factor binding sites including the specific protein-1 (Sp1) binding site, the sterol regulatory elements (SRE), the thyroid hormone response elements (TRE), and the E-box (helix–loop–helix protein binding sites). The transcriptional control of Ucp2 gene expression determines the levels of its mRNA and, to some extent, the levels of the corresponding protein in several tissues, including lung, kidney, pancreas, and white adipose tissue. A schematic summary of the overall regulatory network of human Ucp2 transcription is shown in Fig. 1.

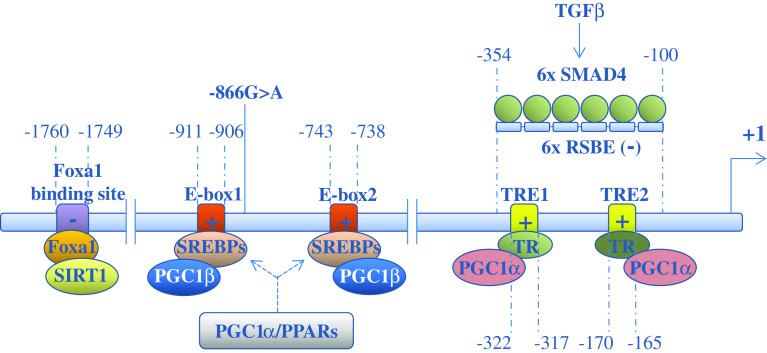

Fig. 1.

Transcriptional regulation of human Ucp2 gene. Schematic representation of the transcription factor binding sites and of their relative transcription factors/regulatory proteins involved in the regulation of human Ucp2 transcription. The positions of transcription factor binding sites represent nucleotide positions relative to the transcription start site. TRE thyroid hormone response elements, E-box helix–loop–helix protein binding sites, PPARs peroxisomal proliferators-activated receptors, SREBPs sterol response element binding proteins, TRs thyroid hormone receptors, PGC-1 PPARgamma coactivator-1, RSBEs repressive SMAD binding elements. The −866G>A polymorphism is shown. The symbols plus or minus in the transcription factor binding sites indicate activation or repression of Ucp2 transcription, respectively

PPAR family

The first described transcriptional activators of Ucp2 are long-chain fatty acid, which have been shown, in vitro [95] and in vivo [96], to induce up-regulation of Ucp2. Strikingly, in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, up-regulation of Ucp2 by polyunsaturated fatty acids is abolished by pre-treating the cells with actinomycin D, suggesting that long-chain fatty acids per se induce transcription of Ucp2 [95]. One possible candidate for transcriptional activation by long-chain fatty acids is peroxisomal proliferators-activated receptors (PPARs), a nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that regulates the metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids. Indeed, several studies have indicated that the PPAR transcription factor family regulates Ucp2 expression. Among the PPAR superfamily, PPARα is mainly expressed in organs that are critical in fatty acid catabolism, such as liver, heart, and kidney, and its most critical role is to modulate hepatic fatty acid catabolism [97] in order to counterbalance the increased ROS production. In liver, indeed, increased PPARα activity during accelerated fatty acid catabolism is associated with increased expression of UCP2 as well as other free radical scavengers [98, 99]. In line with this result, HepG2 cells or the liver of mice treated with acetic acid show increased expression of PPARα and UCP2, which is not observed in cells depleted of alpha2 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by siRNA [100], suggesting that PPARα induction is mediated by AMPK. PPARδ (also known as PPARβ) is the predominant PPAR isoform expressed in skeletal muscle, and selective ablation of its gene in skeletal muscle diminishes the oxidative capacity of this tissue, thus leading to the development of obesity and glucose intolerance [101]. Upon agonist stimulation of PPARδ, Krueppel-like transcription factor 5 (KLF5), which is a crucial regulator of energy metabolism, is deSUMOylated, and become associated with transcriptional activation complexes containing both the liganded PPARδ and CREB binding protein (CBP), which in this state can increase the expression of UCP2 [102]. The PPARγ subtype activates both lipogenic and lipid oxidation genes [103] and is highly expressed in adipocytes, where it is a master regulator of adipogenesis [104]. Induction of Ucp2 by a PPARγ agonist has been demonstrated in clonal adipocyte cell lines and isolated adipocytes [105–107]. In rat brain, Chen et al. [108–110] have demonstrated that rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, enhances UCP2 expression after cerebral ischemia or kainic acid-induced status epilepticus to protect against neuronal cell death in the hippocampus. The authors show that Ucp2 activation leads to decreased ROS production, reduced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis and retarded neuronal injury. The PPARs bind direct repeats of 5′-AGGTCA-3′ spaced by one nucleotide (DR1) as obligate heterodimers with the retinoid X receptors (RXRs) [111, 112]. However, so far, no such PPAR response elements (PPREs) have been annotated within or in vicinity of the Ucp2 gene. Thus, the PPAR-mediated regulation of UCP2 appears to be indirect, but has been reported to be dependent on the double E-box motif in the proximal promoter [113]. Recent findings have demonstrated that, in murine adipocytes, a PPARγ/RXR binding site located in intron 1 of the Ucp3 gene, which is located head to tail with Ucp2 gene on chromosome 7, facilitates PPARγ transactivation of the Ucp2 promoter [114]. Using the chromatin conformation capture technique, it was indeed demonstrated that the PPARγ/RXR binding site of Ucp3 loops out to simultaneously interact indirectly with intron 1 of the Ucp2 gene through a transcription factor complex at +400 relative to the transcription start site, giving rise to an heterologous transactivation. The importance of intron 1 in regulating Ucp2 transcription is also demonstrated by the presence of a silencer element in this region [115].

PGC-1α

UCP2 is a critical determinant in the regulation of insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells [25] by controlling ATP production. In these cells, its expression is linked to the activity of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator1-alpha (PGC-1α) [116]. Indeed, a coordinate up-regulation of pancreatic Ucp2 and PGC-1α gene expression has been observed in several animal models of T2D that are characterized by marked defects in insulin secretion [25]. In pancreatic beta-cells, PGC-1α has been shown to stimulate TR-mediated human Ucp2 gene expression via two TREs located in the proximal Ucp2 promoter region [117]. Since thyroid hormone is known to reduce the insulin secretory response to glucose [118], one of the causes of this effect might be its interaction with PGC-1α on the Ucp2 promoter and the subsequent Ucp2 expression. The reduction of insulin secretion following endurance exercise also seems to be determined by AMPK-mediated Ucp2 activation, probably by enhancing PGC-1α content [119]. PGC-1α can also indirectly induce Ucp2 gene expression by co-activating liver X receptor-mediated expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1c as well as dexamethasone-stimulated SREBP-2 expression. SREBP isoforms are known to regulate Ucp2 gene expression via either one of the two E-box motifs present on Ucp2 promoter [118]. In contrast to PGC-1α, PGC-1β binds and directly co-activates SREBPs [120] and has also been shown to up-regulate Ucp2 in pancreatic beta-cells, supporting a role of PGC-1β in the regulation of insulin secretion [121].

Foxa1

Furthermore, the transcription factor Foxa1 has been shown to control insulin secretion via Ucp2 regulation. Indeed, Foxa1-deficient islets have severely impaired GSIS and decreased insulin mRNA, together with partially uncoupled mitochondria secondary to up-regulation of Ucp2 [122]. Foxa1 is able to bind to the Ucp2 promoter at a preferred site located between −1,760 and −1,749 bp relative to the transcriptional start site of the gene. In this system, Foxa1 behaves as a repressor, although it is primarily considered an activator of transcription. This transcriptional inhibiting activity may depend on the interaction with Sirtuin1 (SIRT1), a potent transcriptional repressor that occupies the Ucp2 promoter in close proximity to the Foxa1 binding site [123]. SIRT1 is a member of the sirtuin family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylases that was also identified as a critical mediator of neuro-protection by resveratrol [124] acting through Ucp2 repression and the consequent increase of mitochondrial ATP-producing capacity [125].

SMAD4

A negative regulation of Ucp2 has also been shown following TGFβ signaling [49]. This paper reports a significant association between mitochondrial UCP2 expression and tumor grade in primary breast cancer. Indeed, it is demonstrated that moderately differentiated tumor cells are able to recruit TGFβ-induced SMAD4 to six repressive SMAD binding elements (RSBEs, −100 to −354) of the Ucp2 promoter, thus repressing gene transcription, while poorly differentiated tumor cells, which are TGFβ-resistant, display aberrant UCP2 up-regulation.

Translational regulation

miRNAs

Although UCP2 transcriptional regulation is the main mechanism being studied, translational events can also strongly influence protein abundance. Recently, a class of RNA regulatory genes known as microRNAs (miRNAs) has been found to introduce a whole new layer of protein regulation after transcription [126]. miRNAs act as endogenous sequence-specific suppressors of translation and thus can block target protein expression without affecting mRNA stability. Their widespread and important role in eukaryotes is highlighted by recent discoveries showing that they control a range of physiological processes including development, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and metabolism [126]. Generally, the production of mRNAs whose translation can be regulated is appropriate for a highly effective and rapid control of expression of genes with critical biological functions. Pecqueur et al. [127] reported that, although UCP2 mRNA has been found in mouse heart and skeletal muscle, no UCP2 protein can be detected in these tissues. Intriguingly, Chen et al. [128] demonstrated that the repression of Ucp2 expression in cardiac and skeletal muscle results from its targeting by a muscle-specific miRNA, miR-133a, which acts as an endogenous sequence-specific suppressor of translation without affecting mRNA stability. UCP2 has been shown to brake muscle development, thus a direct up-regulation of miR-133a by the myogenic regulatory transcription factor MyoD is required to proceed to myogenic differentiation. In addition, since enhanced UCP2 expression has recently been reported to play an important role in the development of heart failure [129], miR-133a targeting UCP2 may be considered a hidden disease regulator of this pathology, opening new exciting methods of treatment for muscle-related diseases.

Furthermore, the increased expression of miR-15a has been found to contribute to the intracellular accumulation of insulin by directly targeting and repressing UCP2 mRNA translation in pancreatic beta-cells [130]. A role for UCP2 in insulin secretion has been previously demonstrated, since UCP2 KO mice show higher ATP levels in islets and increased insulin secretion upon glucose stimulation. Conversely, UCP2 over-expression in cultured beta-cell lines reduces ATP levels and GSIS [25, 123]. Therefore, UCP2 inhibition by miR-15a increases insulin biosynthesis following glucose stimulation. For this activity, miR-15a may be considered an important candidate as an insulin secretion molecular target for the development of preventive or therapeutic agents against beta-cell disorders and diabetes mellitus.

hnRNP K

A yeast three-hybrid screen revealed that the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K), an ubiquitously expressed RNA-binding factor involved in multiple processes including mRNA translation [131], binds to UCP2 mRNA through sites located in the 3′ untranslated region of the transcript [132]. The authors demonstrated that expression of exogenous K protein augments the insulin-induced mitochondrial level of UCP2 protein without increasing UCP2 mRNA, suggesting that insulin stimulates translation of UCP2 mRNA in a process that involves the K protein [132]. More recently, it has been shown that adiponectin administration, an adipocyte-derived hormone possessing a wide range of beneficial functions against obesity-associated medical complications [133], restores mitochondrial functions, depletes lipid accumulation, and up-regulates UCP2 expression in liver tissues of adiponectin knockout mice [134]. Insights into the molecular mechanisms regulating UCP2 expression by adiponectin in hepatic endothelial cells revealed that it favors the translation of UCP2 mRNA through the enhancement of hnRNP K [135].

Miscellaneous

In support of the rationale for the translational control of UCP2 mRNA as a rapid response to oxidative stress, Giardina et al. [136] observed that the abundance of UCP2 in macrophages increases rapidly in response to treatments that promote mitochondrial superoxide production, such as rotenone, antimycin A, and diethyldithiocarbamate. This event has been reported to be associated with enhanced translational efficiency in the absence of UCP2 mRNA increase. These findings extend our understanding of the homeostatic function of UCP2 in regulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen production by identifying a feedback loop that senses mitochondrial reactive oxygen production, and increases inner mitochondrial membrane expression of the antioxidant UCP2. Another study showed that the increase in pulmonary UCP2 protein expression by starvation or lipopolysaccharide is not accompanied by an increase in the mRNA level [127], supporting the assumption that UCP2 responds to oxidative stress via translational regulation of the UCP2 mRNA. The UCP2 mRNA is characterized by a long 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), in which an upstream open reading frame (uORF) codes for a 36-amino acid sequence whose relative peptide production has not yet been demonstrated. The 5′UTR and uORF have an inhibitory role in the translation of UCP2. Hurtaud et al. [137] demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis experiments that the 3′ region of the uORF is a major determinant for this inhibitory role. In a subsequent article, the same authors described that UCP2 expression is stimulated by glutamine at physiological concentrations and that this control is exerted at the translational level through the uORF located in the 5′UTR of the UCP2 mRNA [138]. Further studies need to be addressed to elucidate the molecular events underlying this phenomenon and to unravel whether UCP2 is of any importance for the metabolism of glutamine. A schematic representation of the various regulatory regions of UCP2 mRNA at the translational level is shown in Fig. 2.

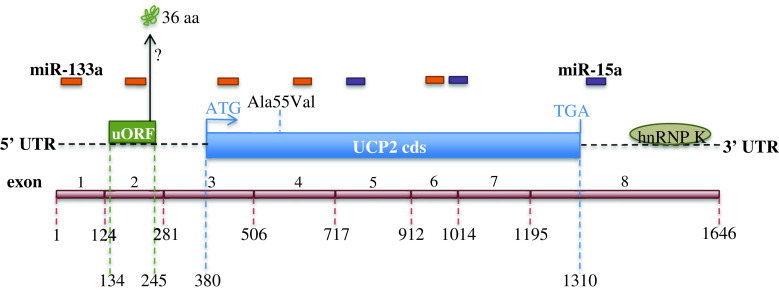

Fig. 2.

Translational regulation of UCP2. Schematic representation of the various regulatory regions of the UCP2 mRNA. The specific complementary sites of miRNA-133a and miRNA-15a in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR), in the UCP2 coding sequence (UCP2 cds), and in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the UCP2 mRNA (NM_003355) are represented on the basis of UCP2 mRNA sequence analysis performed using NCBI-Nucleotide web site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore). The position of the UCP2 exons and of the Ala55Val polymorphism are shown. uORF upstream open reading frame, hnRNP K heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K

Post-translational regulation

GSH is the major regulator of cellular redox status due to its high concentration, reductive potential, and involvement in quenching oxidative stress [139]. Covalent modification of proteins with GSH is also emerging as a key post-translational modification required for protein regulation in response to changes in redox environment. Reactive cysteine residues of cellular proteins are known sites of regulation by conjugation to GSH, a process referred to as glutathionylation. This is especially relevant for mitochondria because a large fraction of the mitochondrial proteome contains exposed thiols that can be covalently modified by GSH. Recently, the research group of Mary-Ellen Harper provided the first evidence that implicates reversible glutathionylation in the regulation of UCP2 activity [140]. They also showed that glutathionylation and ROS-induced deglutathionylation work in tandem to turn UCP2 off and on, respectively [140]. The same authors demonstrated that induction of glutathionylation not only deactivates UCP2-mediated proton leak but also enhances GSIS in Min6 insulinoma cells and pancreatic islets isolated from mice [141]. Collectively, their findings indicated that the glutathionylation status of UCP2 contributes to the regulation of GSIS. During the last year, the same authors demonstrated that pharmacological glutathionylation of UCP2 with diamide, a glutathionylation catalyst, sensitizes drug-resistant promyelocytic leukemia cells to chemotherapeutics [142], showing that targeted inhibition of UCP2 by glutathionylation can serve as a therapeutic approach to kill cancer cells.

Regulation of protein turnover

Several data have demonstrated the existence of UCP2 protein regulation, allowing a rapid decrease in UCP2 expression. Indeed, UCP2 is very unstable, with a half-life close to 30 min [143, 144], compared to 30 h for its homologue UCP1 [145], a difference that may highlight different physiological functions. Heat production by UCP1 in brown adipocytes is generally a long and adaptive phenomenon, whereas control of mitochondrial ROS by UCP2 needs more subtle regulation. The short UCP2 half-life is unusual for mitochondrial carriers whose half-lives are commonly accepted to be over 10 h. In addition, since UCP2 attenuates insulin secretion by regulated uncoupling which lowers the mitochondrial proton motive force and the cytosolic ATP:ADP ratio, the research group of Martin Brand characterized the content and regulation of UCP2 in INS-1E insulinoma cells [146]. They demonstrated that the short half-life of UCP2 allows rapid and dynamic fluctuations in the cellular UCP2 content in response to nutrients in the medium [146, 147], and that the ubiquitin proteasome system is involved in the rapid degradation of UCP2, providing the first demonstration that a mitochondrial inner membrane protein is degraded by the cytosolic ubiquitin proteasome [148]. However, the mechanism of interaction between this cytosolic machinery and UCP2 residing in the inner mitochondrial membrane remains unknown.

Regulation of proton conductance

The regulatory roles that mitochondrial uncoupling by UCP2 could play in the cells can occur over minutes and hours by the dynamic regulation of UCP2 concentration discussed earlier and over seconds by the activation of UCP2 proton conductance. The overall molecular events involved in the regulation of the uncoupling activity of UCP2 are represented in Fig. 3.

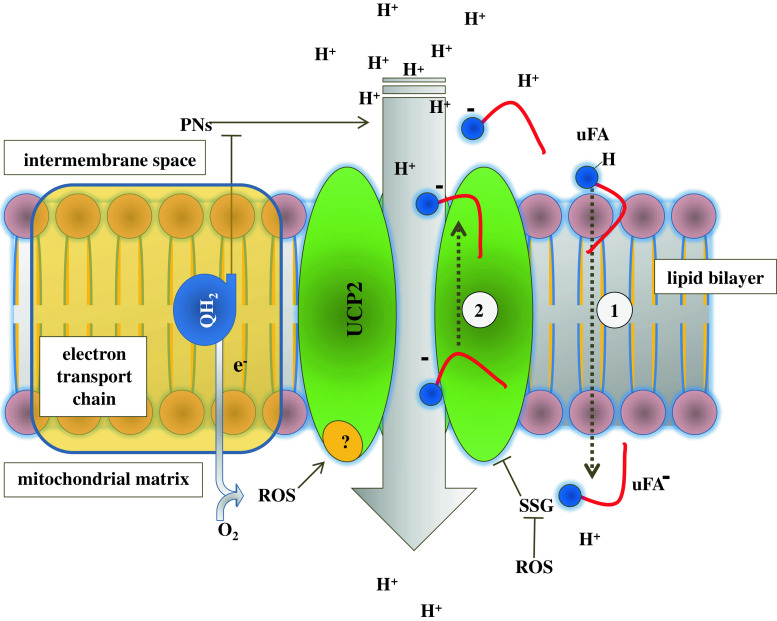

Fig. 3.

Post-translational and proton conductance activity regulation of UCP2. The overall molecular events involved in the regulation of the uncoupling activity of UCP2 are represented. The UCP2-mediated cycling hypothesis is shown. Unsaturated fatty acids (uFA) flip-flop along their interleaflet concentration gradient (1), and the subsequent backward transport of the anionic deprotonated uFA− is ensured by UCP2 (2). SSG glutathionylation, ROS reactive oxygen species, PNs purine nucleotides, QH 2 ubiquinol

ROS

Mitochondria are the main source of ROS, in particular superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical, within most cells. ROS production in mitochondria is sensitive to the proton motive force and ROS concentration is regulated by scavenging enzymes and the activation of UCPs, which decrease the mitochondrial inner membrane potential (ΔΨm). Furthermore, Wojtczak et al. [149] proposed that UCP2 could directly transport superoxide anions across the inner mitochondrial membrane, thus exporting this noxious molecule from the mitochondrial interior to the cytoplasm. Inducible UCP2-mediated proton leak by ROS has recently emerged as a major mechanism for the adjustment of the membrane potential to control mitochondrial ROS emission [150, 151]. By mildly uncoupling, the mitochondria can avoid the oversupply of electrons/reducing equivalents into the respiratory complexes and minimize the likelihood of electron interaction with oxygen. Brand’s group reported that superoxide generated in the mitochondrial matrix activates UCP2-mediated proton leak at the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane, establishing that superoxide does not need to be exported or to cycle across the inner membrane to cause uncoupling [152]. However, despite these observations, the exact biochemical nature of this UCP2 proton conductance activation remains elusive. Thus, although ROS regulation of UCP2 activity is an appealing suggestion, its validity has not yet been unquestionably established. Effects of ROS (and ROS products) on proton leak in mitochondria from different tissue origins have been shown, but several studies underline the difficulties to demonstrate whether these effects are directly mediated by UCP2 or by other mechanisms, such as, for instance, activation of mitochondrial permeability transition pore [23, 27, 29].

FAs

It has been well described that the most studied UCP1 mediates the fatty acid (FA)-dependent H+ influx resulting in the uncoupling of electron transport from ATP synthesis that leads to the rapid production of heat. Currently, two main models have been proposed to explain the mechanism of the FA-mediated proton transport by UCPs. The cofactor model proposes that FA carboxyl groups can buffer protons, thus enhancing the rate of proton movement [153, 154]. In the flip-flop model, protonated FA can flip-flop through the membrane bilayer along their interleaflet concentration gradient and dissociate a proton in the matrix because of the difference in pH, and FA anions can be transported back by UCPs through an unknown mechanism [155, 156]. Beck et al. [157] hypothesized that FAs− reach, by lateral diffusion, a weak binding site on UCPs which most probably only the anionic form can bind and that they are backward transported on the protein lipid interface. In addition, it has been suggested that acidic residues close to the surface and core of the protein may be required to induce FA-mediated proton transport [7]. Echtay et al. [153] showed that Asp28 in UCP1 (conserved in all UCPs 1–3) plays an important role in proton transport, and when mutated to Asn proton transport is drastically reduced (but retained on replacement with Glu, present in UCPs 4 and 5). Despite these observations, however, FAs have not yet been shown to directly bind UCP2 at a specific site.

In addition, Beck et al. [157] intriguingly demonstrated that both UCP1 and UCP2 can be activated much more effectively by polyunsaturated than by saturated FAs. In particular, UCP2 proton conductance increases in the following order: palmitic < oleic < eicosatrienoic < linoleic < retinoic < arachidonic acids [157]. The preferential activation of UCPs by polyunsaturated FAs may be of great physiological relevance in vivo. Indeed, suggestions have been made that ROS themselves, possibly via downstream lipid peroxidation products of polyunsaturated FAs, act in a negative feedback loop to attenuate their own production by inducing such a proton leak [158]. Of these ROS-derived lipid peroxidation products, HNE (4-hydroxynonenal), an unsaturated hydroxyalkenal, is known to be particularly reactive and is implicated in the protection from free-radical damage. It has been shown that cytotoxic HNE is also able to act as a signaling molecule, inducing mitochondrial uncoupling via the mitochondrial carriers, specifically UCPs (UCP1, UCP2 and UCP3) and ANT (adenine nucleotide translocase) [159]. The mechanism of induction of proton leak by HNE is unclear. It has been postulated that covalent modification by HNE could cause conformational changes in the UCPs, which allow the passage of protons back into the mitochondrial matrix [160]. However, the current model proposed for animal mitochondria [13] for the induction of UCPs by superoxide through the initiation of lipid peroxidation (the HNE pathway), which leads to feedback down-regulation of mitochondrial ROS production, cannot yet be applied to the UCPs of unicellular eukaryotes. This feature could be explained by the different localization of fatty acid degradation. Indeed, in contrast to animal cells where the major site for fatty acid β-oxidation is the mitochondrion, in yeast and protists, β-oxidation generally occurs in peroxisomes or glyoxysomes. Nonetheless, in the mitochondria of the protist Acanthamoeba castellanii, Woyda-Ploszczyca et al. [161] very recently demonstrated that exogenous addition of HNE is potentially able to induce UCP-mediated mitochondrial uncoupling and proton leak decreasing the yield of oxidative phosphorylation in an HNE concentration-dependent manner. To investigate the role of ΔΨm in UCP-mediated uncoupling, Rupprecht et al. [162] created planar membranes reconstituted with purified UCPs (UCP1 and UCP2) and/or unsaturated FAs. They demonstrated that UCPs and FAs decrease ΔΨm more effectively when it is sufficiently high, supporting the tight regulation of UCP-mediated proton conductance by ΔΨm. In this context, Parker et al. [163] proposed that stimulation of mitochondrial proton conductance by HNE requires a high mitochondrial membrane potential. This requirement should prevent both the uncoupling of mitochondria by non-mitochondrial ROS and its peroxidation products generated during high workload when mitochondria are functioning at a lower membrane potential.

Purine nucleotides

UCP2 fulfills its physiological function by FA-activated and purine nucleotide (PN)-inhibited H+ cycling process driven by mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). The results presented by Woyda-Ploszczyca et al. [164] obtained with non-phosphorylating A. castellanii mitochondria showed that the guanine and adenine nucleotides exhibit an inhibitory effect on the FA-induced UCPs sustained uncoupling in the following descending order: GTP > ATP > GDP > ADP ≫ GMP > AMP. Taking into account the apparent affinity of reconstituted UCPs for PNs [165, 166] and the concentration of nucleotides in vivo (at millimolar concentrations inside the cells), UCPs should be permanently inhibited under in vivo conditions, even in the presence of FAs, unless a regulatory factor or mechanism could alleviate the inhibition by PNs. It has been found that ubiquinol (QH2), but not oxidized Q, functions as a negative regulator of UCP inhibition by purine nucleotides [164]. When availability of the inhibitor (GTP) or the negative inhibition modulator (QH2) was changed, a competitive influence on the UCP activity was observed. QH2 decreased the affinity of UCPs for GTP and, vice versa, GTP decreased the affinity of UCPs for QH2 [164]. These data describe the kinetic mechanism of regulation of UCP2 affinity for purine nucleotides by endogenous QH2. It has been proposed that the purine nucleotide binding site in UCP1, as determined by site-directed mutagenesis, involves three basic arginine residues, Arg84, Arg183, and Arg277, conserved in all five UCPs [12, 167]. Two conserved tryptophan residues, Trp174 and Trp281, are located in close proximity to the Arg residues [167]. Hence, detection of nucleotide binding can be potentially observed by the changes in the microenvironment of these aromatic residues. Recently, Berardi et al. [11] sophisticatedly determined the structure of UCP2 in the presence of GDP using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) molecular fragment searching. They discovered that the nitroxide-labeled GDP binds inside the UCP2 channel covering residues of transmembrane helices 1–4. Intriguingly, their model is consistent with GDP binding deep within the UCP2 channel, similar to the proposed ADP binding site in ANT1 [168].

In addition, since ADP and ATP are capable of binding to and inhibiting UCPs and since CoA has a purine nucleotide moiety on one end, it can be plausible that CoA may bind to UCPs through its adenine-containing nucleotide element. Despite the interaction of CoA with UCPs having not yet been clearly characterized, Ivanova et al. [167] supported this interaction demonstrating that the fluorescence spectra of GDP/GTP addition and CoA addition show similar changes relative to the free protein spectra.

Nutritional regulation

In the last few years, some studies have been addressed to determine the impact of various substances contained in foods on the regulation of UCP2 expression [169]. In vivo studies indicate that physiological and pathological elevation of blood long-chain fatty acids resulting from fasting, high-fat diet, suckling of newborn pups, sepsis, or streptozotocin-induced diabetes induces up-regulation of UCP2. As discussed above, long-chain fatty acids can induce UCP2 at the transcriptional level. One probable candidate for transcriptional activation of UCP2 by long-chain fatty acids is represented by PPARs belonging to the lipid-activated receptor superfamily [170]. In particular, daily intake of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) has been shown to reduce body fat accumulation and to increase body metabolism by up-regulation of UCPs. Diet supplementation with CLA reduced both lipid accumulation in adipose tissues and triacylglycerol plasma levels, but did not augment hepatic lipid storage. Livers of mice fed a diet supplemented with CLA showed higher UCP2 mRNA levels and the isolated hepatic mitochondria showed higher uncoupling activity. These results indicate a beneficial and safe dosage of CLA for diet supplementation in mice, which induces UCP2 over-expression and uncoupling activity in mitochondria, preserving the lipid composition and the redox state of the liver [171].

Black soybean, a type of soybean with a black seed coat, has been widely used as a nutritionally rich food in Asia. Black soybean, called “Kokuzui” in Japan, has been utilized as a traditional herbal medicine for the prevention of diabetes, aiding liver and kidney functions, and enhancing diuretic actions. Black soybean seed coat, unlike yellow soybean seed coat, is rich in polyphenols, reported to play an important role in the prevention of diseases related to oxidative stress, including atherosclerosis, carcinogenesis, and inflammatory diseases. Kanamoto et al. [172] demonstrated that C57BL/6 mice fed for 14 weeks with a high-fat diet containing black soybean seed coat extract (BE) ameliorated obesity and glucose intolerance by up-regulating UCPs and down-regulating inflammatory cytokines. Indeed, BE suppressed fat accumulation in mesenteric adipose tissue, reduced the plasma glucose level, and enhanced insulin sensitivity in the high-fat diet-fed mice. The expression levels of UCP1 in brown adipose tissue and UCP2 in white adipose tissue were significantly up-regulated after BE rich diet.

Finally, Lionetti et al. [173] compared the effects in rats of raw donkey milk to those produced by intake of an iso-energetic amount of raw cow milk for 4 weeks. They discovered that diet supplementation with donkey milk enhanced mitochondrial activity/proton leakage and increased the activity and expression of mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyl transferase and UCP2. The beneficial effects observed in donkey milk-treated animals can be attributable, at least partially, to the UCP2-mediated association between decreased energy efficiency and reduced pro-inflammatory signs (TNF-α and LPS levels) together with the significant increase of antioxidant (total thiols) and detoxifying enzyme activities.

Pharmacological regulation

AMPK activators

It has been found that UCP2 expression/activity can be modulated by different drugs. Metformin, a drug used in the treatment of diabetes, does not influence insulin secretion but, rather, it helps to improve the control of glycaemia by promoting glucose utilization through an AMPK-mediated stimulation of catabolism. Indeed, metformin increases lipolysis and reduces triglyceride stores in adipocytes. The inhibition of the mitochondrial complex I by metformin supposedly causes an energy deficit that decreases ATP levels and activates AMPK. Additionally, inhibition of complex I is known to cause an increase in superoxide production. Since high ROS levels prompt the response of the cellular antioxidant defenses, the observed increase in UCP2 levels is consistent with its postulated role in the protection against oxidative damage. The enhanced UCP2 protein levels after treatment with metformin occurs by a translational control of UCP2 without changes in mRNA level [174]. Similarly, Kim et al. [175] reported that the AMPK activator 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) and the constitutive active form of AMPK inhibited palmitate-induced apoptosis through ROS suppression. The AMPK inhibitor compound C, the dominant-negative mutant of AMPK, and the UCP inhibitor guanosine diphosphate blocked the antiapoptotic and antioxidative effects of AICAR by inhibiting the AICAR-mediated UCP2 increase. Furthermore, over-expression of UCP2 inhibited palmitate-induced apoptosis and ROS generation, suggesting that the activation of AMPK inhibits palmitate-induced endothelial cell apoptosis through the suppression of ROS generation by UCP2 activation. In traditional Chinese medicine, berberine, an isoquinolone alkaloid found in plants, is reported to exert anti-fungal, anti-bacterial/viral, and anti-oncogenic effects, as well as a beneficial effect on diabetes and anti-atherogenic properties. Berberine has also been reported to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and to improve the endothelial function and dyslipidemia. Accordingly, Wang et al. [176] demonstrated that berberine significantly increases UCP2 mRNA and protein expression in an AMPK-dependent manner in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. In addition, they showed that chronic administration of berberine in mice significantly reduces aortic lesions, markedly reduces oxidative stress and expression of adhesion molecules in aorta, and significantly increases UCP2 level, concluding that berberine reduces oxidative stress and prevents vascular diseases via AMPK-dependent stimulation of UCP2 expression.

Chemotherapeutic drugs

Doxorubicin-based chemotherapy is limited by the development of dose-dependent left ventricular dysfunction and congestive heart failure caused by ROS. Since prior studies have shown that cardiac UCP2 and UCP3 mRNA expression is decreased with acute doxorubicin treatment, Bugger et al. [177] revealed that doxorubicin-induced heart failure is associated with a significant decrease in UCP2 and UCP3 protein expression, compared with nonfailing hearts. While the rates of state 3 and state 4 respiration and ATP synthesis were lower in mitochondria isolated from failing hearts, the respiratory control ratio was 15 % higher, and the ratio of ATP production to oxygen consumption was 25 % higher in mitochondria from failing hearts, indicating greater coupling between citric acid cycle flux and mitochondrial ATP synthesis. However, the decrease in the expression UCPs was associated with 50 % greater mitochondrial ROS generation. Thus, down-regulation of myocardial UCP2 and UCP3 in the setting of doxorubicin-induced heart failure is related to improved efficiency of ATP synthesis, which might compensate for abnormal energy metabolism, but this apparently beneficial effect is counterbalanced by greater oxidative stress. Taxol (paclitaxel), an antineoplastic drug used in the treatment of different tumor types, resulted in the activation of apoptosis signal-regulated kinase (ASK), c-jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), p38MAPK, and extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) together with the down-regulation of UCP2. In addition, ROS were induced and DNA-binding activity of the transcription factors AP-1, ATF-2, and ELK-1 was enhanced. Pretreatment of melanoma cells with the JNK inhibitor (SP600125) or the p38 inhibitor (SB203580) blocked taxol-induced UCP2 down-regulation, ROS generation, and apoptosis, whereas the ERK inhibitor (PD98059) had no such effects. These data provide evidence that taxol-induced mitochondrial stress occurs through the activation of both JNK and p38 pathways, previously described to be involved in UCP2 regulation [19], and suggest a novel role for UCP2 in the modulation of taxol-induced apoptosis of melanoma cells [178]. Our research group has recently demonstrated that the anticancer drug gemcitabine stimulates UCP2 mRNA expression suggesting that UCP2 could have a role in the acquired resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to chemotherapy. Moreover, we found that the basal level of UCP2 mRNA well correlates with IC50 values of gemcitabine, while, in agreement with the antioxidant role of UCP2, it inversely correlates with the constitutive endogenous amount of mitochondrial superoxide [51].

Other drugs

Genipin (methyl-2-hydroxy-9-hydroxymethyl-3-oxabicyclonona-4,8-diene-5-carboxylate), an extract from Gardenia jasminoides, has been shown to be a selective inhibitor of UCP2 and to improve insulin secretion. The specificity of genipin for UCP2 was confirmed using CHO cells stably expressing UCP2 in which genipin induced a 22 % decrease in state 4 respiration. These effects were absent in empty vector CHO cells expressing no UCP2 [53].

Since UCP2 appears to be one of the most interesting pharmacological targets in the therapy of several diseases, Rial et al. [179] performed a screening approach to discover small-molecule inhibitors of this mitochondrial protein. They showed that chromane derivatives can inhibit UCP2 in yeast mitochondria. In addition, chromane derivatives have been demonstrated to inhibit respiration and increase ROS levels in highly UCP2-expressing HT-29 cancer cells. Furthermore, they can synergistically act with chemotherapeutic agents in a pro-oxidant dependent manner, opening a promising line in the development of novel anticancer agents.

In addition, the synthetic immunomodulator muramyl dipeptide (MDP) induces in vivo mitochondrial proton leak and rapidly up-regulates the expression of UCP2. Pretreatment with vitamin E attenuates this up-regulation, suggesting that the MDP-induced ROS can up-regulate UCP2 expression in order to counteract the pro-oxidant effects of MDP [180].

Cyanide is a potent neurotoxicant that produces a rapid onset of toxicity and death within minutes. In sub-lethal toxicity, lesions of the central nervous system may develop which may manifest as a Parkinson-like syndrome. Since it has been shown that UCP-2 up-regulation may contribute to cell death by reducing expression of Bcl-2, Zhang et al. [181] reported that cyanide-induced death of dopaminergic cells is mediated by UCP2 up-regulation and reduced Bcl-2 expression. Interestingly, up-regulation of UCP2 has been associated with several models of brain injury and neurodegeneration in which the level of expression appears to regulate the level of cell injury [182, 183], thus representing a promising therapeutic target for neuronal diseases.

Finally, since general anaesthesia is associated with oxidative stress, hypothermia, and immune depression, Alves-Guerra et al. [184] recently aimed to evaluate the expression and the function of UCP2 during anaesthesia. They demonstrated for the first time that UCP2 responds to a physiological change induced by several anesthetics and a myorelaxant, as revealed by increased UCP2 protein content, in both immune and non-immune cells, after induction of anaesthesia with ketamine (20 mg/kg) or isoflurane (3.6 %) and sedation with the α2 adrenergic receptor agonist medetomidine (0.2 mg/kg) in mice. Intriguingly, up-regulation of UCP2 in the lung occurred in less than 1 h after injection of medetomidine, suggesting a translational control of UCP2 as shown in response to LPS, fasting, or glutamine treatment [127, 138]. After a plateau of 2–3 h, UCP2 protein returned to its basal level of expression in about 2 h, which is also in accordance with the short half-life of this protein previously described [144].

Concluding remarks

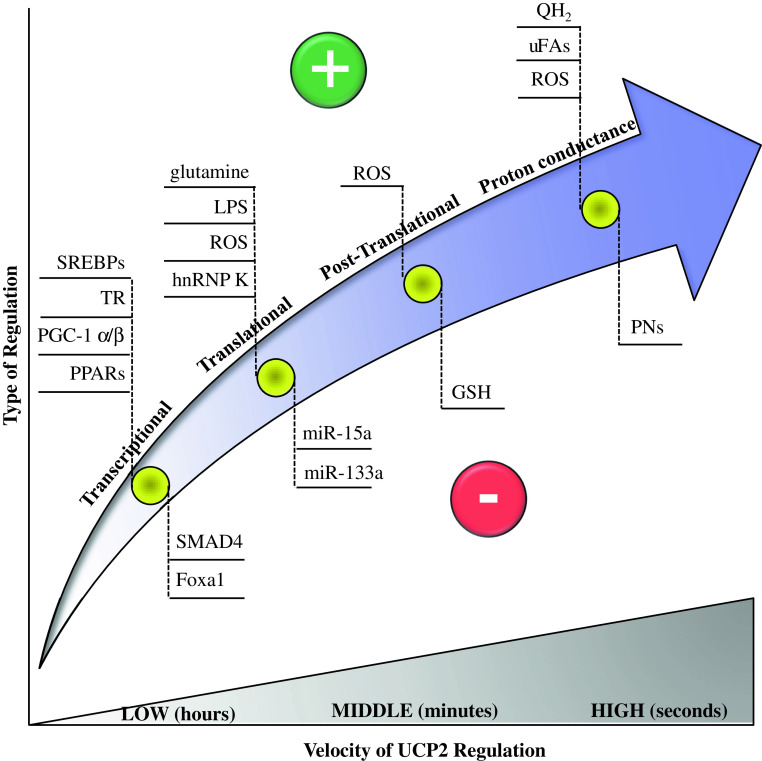

The broad tissue distribution of UCP2 expression, its effects on mitochondrial coupling efficiency, and ROS regulation are responsible for the increasing findings showing the involvement of UCP2 in body-wide physiological and pathological processes. These features make UCP2 an approaching drug target for the treatment of various disorders, including obesity, atherosclerosis, diabetes, immune diseases, neurodegenerative pathologies, and cancer progression. However, the knowledge of the molecular mechanisms at the basis of UCP2 regulation is of fundamental importance for the identification of efficient therapies against UCP2-related disorders. This review describes the most recent and relevant features of the molecular mechanisms of UCP2 regulation, which can occur at different stages, including genetic, protein expression/degradation, and protein activity levels. Figure 4 summarizes the overall molecular mechanisms of UCP2 regulation (transcriptional, translational, post-translational, and proton conductance regulation) and their relationship with the velocity of execution.

Fig. 4.

Summary of the overall molecular mechanisms of UCP2 regulation described in the text and their relationship with the velocity of execution. The symbols plus or minus indicate activation or repression of UCP2, respectively

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana Ricerca Cancro (AIRC), Milan, Italy; Fondazione CariPaRo, Padova, Italy; Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (PRIN, MIUR), Rome, Italy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brand MD, Brindle KM, Buckingham JA, Harper JA, Rolfe DF, Stuart JA. The significance and mechanism of mitochondrial proton conductance. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(Suppl 6):S4–S11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klingenberg M. Uncoupling protein—a useful energy dissipator. J Bioenergy Biomembr. 1999;31:419–430. doi: 10.1023/a:1005440221914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jezek P, Urbankova E. Specific sequence of motifs of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:63–70. doi: 10.1080/713803586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews ZB, Diano S, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins in the CNS: in support of function and survival. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:829–840. doi: 10.1038/nrn1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arsenijevic D, Onuma H, Pecqueur C, Raimbault S, Manning BS, Miroux B, Couplan E, Alves-Guerra MC, Goubern M, Surwit R, et al. Disruption of the uncoupling protein-2 gene in mice reveals a role in immunity and reactive oxygen species production. Nat Genet. 2000;26:435–439. doi: 10.1038/82565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong D, Vong L, Parton LE, Ye C, Tong Q, Hu X, Choi B, Bruning JC, Lowell BB. Glucose stimulation of hypothalamic MCH neurons involves K(ATP) channels, is modulated by UCP2, and regulates peripheral glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krauss S, Zhang CY, Lowell BB. The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:248–261. doi: 10.1038/nrm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ledesma A, de Lacoba MG, Rial E. The mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS3015. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-reviews3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon-Areces J, Dietrich MO, Hermes G, Garcia-Segura LM, Arevalo MA, Horvath TL. UCP2 induced by natural birth regulates neuronal differentiation of the hippocampus and related adult behavior. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu XX, Barger JL, Boyer BB, Brand MD, Pan G, Adams SH. Impact of endotoxin on UCP homolog mRNA abundance, thermoregulation, and mitochondrial proton leak kinetics. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E433–E446. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.2.E433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berardi MJ, Shih WM, Harrison SC, Chou JJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 structure determined by NMR molecular fragment searching. Nature. 2011;476:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelokhani-Niaraki M, Ivanova MV, McIntyre BL, Newman CL, McSorley FR, Young EK, Smith MD. A CD study of uncoupling protein-1 and its transmembrane and matrix-loop domains. Biochem J. 2008;411:593–603. doi: 10.1042/bj20071326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Echtay KS. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins—what is their physiological role? Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1351–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller PA, Lehr L, Giacobino JP, Charnay Y, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F, Giovannini N. Cloning, ontogenesis, and localization of an atypical uncoupling protein 4 in Xenopus laevis . Physiol Genomics. 2005;22:339–345. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanak P, Jezek P. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins and phylogenesis—UCP4 as the ancestral uncoupling protein. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard D, Picard F. Brown fat biology and thermogenesis. Front Biosci. 2011;16:1233–1260. doi: 10.2741/3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garlid KD, Jaburek M, Jezek P, Varecha M. How do uncoupling proteins uncouple? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diao J, Allister EM, Koshkin V, Lee SC, Bhattacharjee A, Tang C, Giacca A, Chan CB, Wheeler MB. UCP2 is highly expressed in pancreatic alpha-cells and influences secretion and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12057–12062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710434105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emre Y, Hurtaud C, Karaca M, Nubel T, Zavala F, Ricquier D. Role of uncoupling protein UCP2 in cell-mediated immunity: how macrophage-mediated insulitis is accelerated in a model of autoimmune diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19085–19090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709557104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klingenberg M, Huang SG. Structure and function of the uncoupling protein from brown adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1415:271–296. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoang T, Smith MD, Jelokhani-Niaraki M. Toward understanding the mechanism of ion transport activity of neuronal uncoupling proteins UCP2, UCP4, and UCP5. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4004–4014. doi: 10.1021/bi3003378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borecky J, Maia IG, Arruda P. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins in mammals and plants. Biosci Rep. 2001;21:201–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1013604526175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couplan E, del Mar Gonzalez-Barroso M, Alves-Guerra MC, Ricquier D, Goubern M, Bouillaud F. No evidence for a basal, retinoic, or superoxide-induced uncoupling activity of the uncoupling protein 2 present in spleen or lung mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26268–26275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadenas S, Buckingham JA, Samec S, Seydoux J, Din N, Dulloo AG, Brand MD. UCP2 and UCP3 rise in starved rat skeletal muscle but mitochondrial proton conductance is unchanged. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:257–260. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang CY, Baffy G, Perret P, Krauss S, Peroni O, Grujic D, Hagen T, Vidal-Puig AJ, Boss O, Kim YB, et al. Uncoupling protein-2 negatively regulates insulin secretion and is a major link between obesity, beta cell dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes. Cell. 2001;105:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pecqueur C, Bui T, Gelly C, Hauchard J, Barbot C, Bouillaud F, Ricquier D, Miroux B, Thompson CB. Uncoupling protein-2 controls proliferation by promoting fatty acid oxidation and limiting glycolysis-derived pyruvate utilization. FASEB J. 2008;22:9–18. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8945com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cannon B, Shabalina IG, Kramarova TV, Petrovic N, Nedergaard J. Uncoupling proteins: a role in protection against reactive oxygen species—or not? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The ‘novel’ ‘uncoupling’ proteins UCP2 and UCP3: what do they really do? Pros and cons for suggested functions. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:65–84. doi: 10.1113/eph8802502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholls DG. The physiological regulation of uncoupling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nubel T, Emre Y, Rabier D, Chadefaux B, Ricquier D, Bouillaud F. Modified glutamine catabolism in macrophages of Ucp2 knock-out mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Produit-Zengaffinen N, Davis-Lameloise N, Perreten H, Becard D, Gjinovci A, Keller PA, Wollheim CB, Herrera P, Muzzin P, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F. Increasing uncoupling protein-2 in pancreatic beta cells does not alter glucose-induced insulin secretion but decreases production of reactive oxygen species. Diabetologia. 2007;50:84–93. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shabalina IG, Nedergaard J. Mitochondrial (‘mild’) uncoupling and ROS production: physiologically relevant or not? Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1305–1309. doi: 10.1042/BST0391305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanc J, Alves-Guerra MC, Esposito B, Rousset S, Gourdy P, Ricquier D, Tedgui A, Miroux B, Mallat Z. Protective role of uncoupling protein 2 in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2003;107:388–390. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051722.66074.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moukdar F, Robidoux J, Lyght O, Pi J, Daniel KW, Collins S. Reduced antioxidant capacity and diet-induced atherosclerosis in uncoupling protein-2-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:59–70. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800273-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rousset S, Emre Y, Join-Lambert O, Hurtaud C, Ricquier D, Cassard-Doulcier AM. The uncoupling protein 2 modulates the cytokine balance in innate immunity. Cytokine. 2006;35:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rupprecht A, Brauer AU, Smorodchenko A, Goyn J, Hilse KE, Shabalina IG, Infante-Duarte C, Pohl EE. Quantification of uncoupling protein 2 reveals its main expression in immune cells and selective up-regulation during T-cell proliferation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diano S, Horvath TL. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derdak Z, Mark NM, Beldi G, Robson SC, Wands JR, Baffy G. The mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 promotes chemoresistance in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2813–2819. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robbins D, Zhao Y. New aspects of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) and their roles in tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:5285–5293. doi: 10.3390/ijms12085285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su WP, Lo YC, Yan JJ, Liao IC, Tsai PJ, Wang HC, Yeh HH, Lin CC, Chen HH, Lai WW, et al. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 regulates the effects of paclitaxel on Stat3 activation and cellular survival in lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:2065–2075. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang K, Shang Y, Liao S, Zhang W, Nian H, Liu Y, Chen Q, Han C. Uncoupling protein 2 protects testicular germ cells from hyperthermia-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harper ME, Antoniou A, Villalobos-Menuey E, Russo A, Trauger R, Vendemelio M, George A, Bartholomew R, Carlo D, Shaikh A, et al. Characterization of a novel metabolic strategy used by drug-resistant tumor cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:1550–1557. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0541com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derdak Z, Fulop P, Sabo E, Tavares R, Berthiaume EP, Resnick MB, Paragh G, Wands JR, Baffy G. Enhanced colon tumor induction in uncoupling protein-2 deficient mice is associated with NF-kappaB activation and oxidative stress. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:956–961. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuai XY, Ji ZY, Zhang HJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 expression in colon cancer and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5773–5778. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clemons M, Goss P. Estrogen and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:276–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felty Q, Singh KP, Roy D. Estrogen-induced G1/S transition of G0-arrested estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells is regulated by mitochondrial oxidant signaling. Oncogene. 2005;24:4883–4893. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sastre-Serra J, Valle A, Company MM, Garau I, Oliver J, Roca P. Estrogen down-regulates uncoupling proteins and increases oxidative stress in breast cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayyasamy V, Owens KM, Desouki MM, Liang P, Bakin A, Thangaraj K, Buchsbaum DJ, LoBuglio AF, Singh KK. Cellular model of Warburg effect identifies tumor promoting function of UCP2 in breast cancer and its suppression by genipin. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sayeed A, Meng Z, Luciani G, Chen LC, Bennington JL, Dairkee SH. Negative regulation of UCP2 by TGFbeta signaling characterizes low and intermediate-grade primary breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e53. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang F, Fu X, Chen X, Chen X, Zhao Y. Mitochondrial uncoupling inhibits p53 mitochondrial translocation in TPA-challenged skin epidermal JB6 cells. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dalla Pozza E, Fiorini C, Dando I, Menegazzi M, Sgarbossa A, Costanzo C, Palmieri M, Donadelli M. Role of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 in cancer cell resistance to gemcitabine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1856–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dando I, Fiorini C, Pozza ED, Padroni C, Costanzo C, Palmieri M, Donadelli M. UCP2 inhibition triggers ROS-dependent nuclear translocation of GAPDH and autophagic cell death in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mailloux RJ, Adjeitey CN, Harper ME. Genipin-induced inhibition of uncoupling protein-2 sensitizes drug-resistant cancer cells to cytotoxic agents. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samudio I, Fiegl M, McQueen T, Clise-Dwyer K, Andreeff M. The Warburg effect in leukemia-stroma cocultures is mediated by mitochondrial uncoupling associated with uncoupling protein 2 activation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5198–5205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dalgaard LT. Genetic variance in uncoupling protein 2 in relation to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and related metabolic traits: focus on the functional −866G>A promoter variant (rs659366) J Obes. 2011;2011:340241. doi: 10.1155/2011/340241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]