Abstract

Insulin/IGF-like signaling regulates the development, growth, fecundity, metabolic homeostasis, stress resistance and lifespan in worms, flies and mammals. Eight insulin-like peptides (DILP1-8) are found in Drosophila. Three of these (DILP2, 3 and 5) are produced by a set of median neurosecretory cells (insulin-producing cells, IPCs) in the brain. Activity in the IPCs of adult flies is regulated by glucose and several neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. One of these, short neuropeptide F (sNPF), regulates food intake, growth and Dilp transcript levels in IPCs via the sNPF receptor (sNPFR1) expressed on IPCs. Here we identify a set of brain neurons that utilizes sNPF to activate the IPCs. These sNPF-expressing neurons (dorsal lateral peptidergic neurons, DLPs) also produce the neuropeptide corazonin (CRZ) and have axon terminations impinging on IPCs. Knockdown of either sNPF or CRZ in DLPs extends survival in flies exposed to starvation and alters carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Expression of sNPF in DLPs in the sNPF mutant background is sufficient to rescue wild-type metabolism and response to starvation. Since CRZ receptor RNAi in IPCs affects starvation resistance and metabolism, similar to peptide knockdown in DLPs, it is likely that also CRZ targets the IPCs. Knockdown of sNPF, but not CRZ in DLPs decreases transcription of Dilp2 and 5 in the brain, suggesting different mechanisms of action on IPCs of the two co-released peptides. Our findings indicate that sNPF and CRZ co-released from a small set of neurons regulate IPCs, stress resistance and metabolism in adult Drosophila.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-012-1097-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Insulin signaling, Peptide hormones, Neuropeptides, Drosophila melanogaster

Introduction

Insulin/IGF-like signaling is conserved over animal evolution and is known to regulate development, growth, fecundity, metabolism, as well as stress resistance and lifespan [1–5]. In Drosophila the insulin/IGF-like signaling pathway has been extensively explored, especially during development, and in larvae and adults with respect to action on the fat body and resulting effects on metabolic homeostasis, stress responses and aging [1, 2, 6–8]. Eight insulin/IGF-like peptides (DILP1-8) have been identified in Drosophila [8–10], and three of these (DILP2, 3, 5) are produced in a set of neurosecretory cells (insulin producing cells, IPCs) in the pars intercerebralis of the brain [1, 8, 11, 12]. These DILPs are released as hormones into the circulation via neurohemal areas in the corpora cardiaca, aorta and anterior gut [11–13], and the IPCs have been genetically targeted for ablation or inactivation in several studies on DILP functions [12, 14–16].

It is less clear how the activity of the IPCs is controlled, and thus how DILP production and release is regulated in the fly. What are the links between nutritional status or various stresses and regulation of insulin release? In adult Drosophila there are indications that the IPCs have autonomous glucose sensing by means of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels [17, 18] similar to mammalian pancreatic beta cells [19]. Nutrient sensing in larvae appears to be by the fat body, which in turn signals with a humoral factor to the brain IPCs [20, 21]. Additionally, the IPCs are under regulatory control by neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. Thus, there is evidence that GABA, serotonin, octopamine, Drosophila tachykinin (DTK) and short neuropeptide F (sNPF) act on IPCs [22–28]. These studies have reported different activities downstream to the IPCs to monitor action of the ligands on these neurons, but it is not always evident whether bona fide insulin production and/or release was affected. For sNPF, however, it seems quite clear that the effects seen on growth are mediated by increased transcription of Dilp2 in the IPCs and increased DILP and MAP kinase signaling [23, 29]. Some of the IPCs were shown to express the sNPF receptor (sNPFR1) [23], known to be ancestrally related to neuropeptide Y (NPY) receptors [30, 31]. However, the sNPF-expressing neuronal pathway that activates the IPCs has not yet been identified. To solve this, we set out to identify sNPF-expressing neurons that target the IPCs and then test the effects of sNPF knockdown in these neurons on Dilp transcription, metabolism and stress resistance.

An earlier study suggested that in the larva a small set of sNPF-expressing neurons (DLPs), located among the lateral neurosecretory cells, sends axon terminations to the branches of the IPCs in the corpora cardiaca of the ring gland [32]. Here, we first confirmed the presence of the sNPF-producing DLPs in adult flies. Next, we employed the Gal4-UAS system to target these neurons for knockdown or overexpression of sNPF, and monitored the effects in various assays for insulin production, stress responses and metabolism.

We found that the sNPF-expressing DLPs additionally produce the neuropeptide corazonin (CRZ). Knockdown of CRZ in the DLPs results in phenotypes like those seen after sNPF knockdown. These observations are interesting since several studies have suggested that CRZ, whose receptor is an ortholog of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptors in mammals [33–35], is important in the regulation of stress responses [36–38]. Also, it has been shown that the CRZ-expressing DLPs in Drosophila co-express receptors for the diuretic hormones DH31 and DH44 [39]. DH44 is related to corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and DH31 to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) of mammals [39, 40]. Like GnRH, these mammalian peptides can act as stress hormones [41–43], and in the fly DH31 and DH44 may be released from the intestine and possibly signal nutritional stress to the CRZ neurons [36, 38, 39].

Our study suggests that IPCs are activated by sNPF and CRZ co-released from a small set of brain neurosecretory cells designated DLPs. The sNPF and CRZ expressing DLPs, which form inputs to the IPCs, may in turn receive signals from intestinal cells by means of the peptides DH31 and DH44 released into the circulation. Thus, a pathway can be postulated that uses peptides similar to the mammalian CGRP, CRF, GnRH and NPY as input signals to regulate IPCs in the fly brain and thereby influence metabolism and stress responses.

Materials and methods

Fly strains

The following Drosophila melanogaster Gal4 lines were used to drive the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) or other UAS constructs: snpfr1-Gal4 (stock no. 46547, see [44]) was from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC), Bloomington, IN; Crz-Gal4 and Akh-Gal4 were gifts from J.H. Park (Knoxville, TN) [45, 46]; snpf-Gal4 ([32] NP6301, order no. 113901) was obtained from the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center (DGRC), Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan; Dilp2-Gal4 from E. Hafen, Zürich, Switzerland [47] donated by Susan Broughton, Lancaster, UK. These Gal4 lines are in w 1118 background, except the Akh-Gal4 and snpf-Gal4 lines, which are in yw, and the Dilp2-Gal4, which is in w Dahomey.

For targeted interference we used: UAS-snpf-RNAi, UAS-snpf-RNAi (x, II) and UAS-snpf [22], both from K. Yu (Daejeon, Korea); UAS-Crz-RNAi (Transformant ID 44310) and UAS-CrzR-RNAi (44310) were from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC); UAS-Ork1.Δ-C [48] was from BDSC (stock no. 8928). The hypomorphic sNPF mutant flies sNPFc00448 [23] from Harvard Stock Center (Exelixis stock collection, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) were obtained from K. Yu. These UAS lines are all in w 1118 background. UAS-mcd8-GFP and w 1118 and Oregon R flies were from BDSC.

Antisera and immunocytochemistry

Adult Drosophila heads, anterior intestine with corpora cardiaca/allata or third instar larval central nervous systems (CNS) with ring glands were dissected out in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) (pH 7.4) and fixed in ice-cold 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB for 2–4 h. Adult brains were further dissected out for whole-mount immunocytochemistry. All the tissues were rinsed with 0.1 M PB three times during 1 h and washed in 0.01 M PBS with 0.25 % Triton-X (PBS-Tx) for 15 min before application of primary antisera. The primary antisera were diluted in 0.01 M PBS-Tx with 0.05 % sodium azide.

Incubation with primary antiserum for whole-mount tissues was performed for 48 h at 4 °C with gentle agitation. The following primary antisera were used: a rabbit antiserum (anti-sNPF) to a sequence of the Drosophila sNPF precursor [49] donated by J.A. Veenstra (Bordeaux, France) was used at a dilution of 1:4,000; a rat anti-DILP2 [20] donated by P. Léopold (Nice, France) was used at a dilution of 1:400. For detection of primary antisera we utilized Alexa 546 tagged goat anti-rabbit antiserum, Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit antiserum and Alexa 488 goat anti-mouse antiserum (all from Invitrogen), and Cy3-tagged goat anti-rat antiserum (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA) all at a dilution of 1:1,000. Tissues were rinsed thoroughly with PBS-Tx, followed by a final wash in 0.01 M PBS and then mounted in 80 % glycerol in 0.01 M PBS. For each experiment we analyzed at least ten adult brains and five intestines/corpora cardiaca or larval CNS.

Image analysis

Specimens were imaged with Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Jena, Germany) using 20×, 40× oil or 63× oil immersion objectives. Confocal images were processed with Zeiss LSM software for either projection of z-stacks or single optical sections. Images were edited for contrast and brightness in Adobe Photoshop CS3 Extended version 10.0.

Assays of survival of starved flies

We used 3-day-old male flies to assay survival of starving flies. Starvation experiments were performed according to the protocol of Lee and Park [46]. Flies were anesthetized on ice and then placed individually in 2-ml cotton-capped glass vials containing 500 μl of 0.5 % aqueous agarose, except in the assays in Fig. 4e, f (in these particular assays, flies were placed in 50-ml vials in groups of 15 flies). All vials were placed in an incubator with 12:12 light:dark conditions at 25 °C. The number of dead flies was recorded every 12 h until no living flies were left. As controls we used the parental strains crossed to w 1118, except in the sNPF rescue experiment (Fig. 4e). All experiments were run in three replicates with at least 69 flies of each genotype in each run.

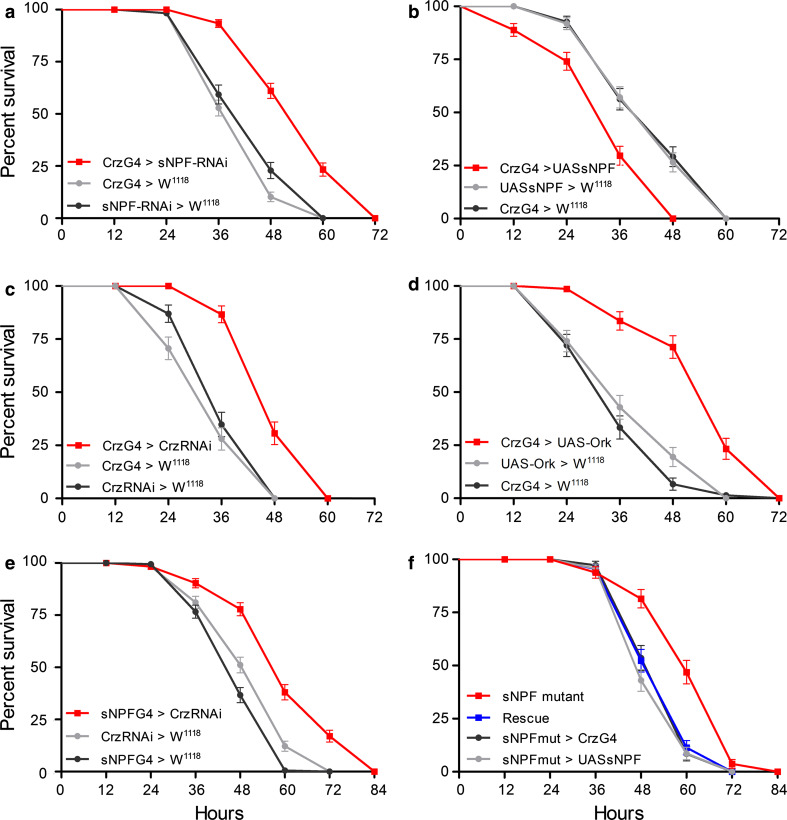

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of sNPF and corazonin in dorsolateral peptidergic neurons (DLPs) or inactivation of these neurons increases resistance to starvation in flies. All experiments were analyzed by the log-rank test, and in (a–f) experimental flies significantly differed (p < 0.0001) from both controls; no significant difference was seen between controls in these experiments (except in e). a Knockdown of sNPF in DLPs (CrzG4>sNPF-RNAi) significantly extends survival of starved flies compared to parental controls (Log Rank test, p < 0.0001 to both controls; n = 118–180 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). b Overexpression of sNPF in the DLPs (CrzG4>UASsNPF) decreases survival of starving flies (n = 92–105 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). c Diminishing corazonin in DLPs (CrzG4>Crz-RNAi) increases starvation resistance ( n = 69–75 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). d Inactivation (hyperpolarization) of the DLPs by expression of a constitutively active potassium channel, dOrk (CrzG4>UAS-Ork) strongly increases survival of starving flies (n = 73–85 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). e We also tested corazonin knockdown in sNPF expressing neurons (sNPFG4>CrzRNAi) and obtained an increased survival at starvation n = 180 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). Here, the experimental flies significantly differed (p < 0.0001) from both controls, but there was also a significant difference between the two controls (P = 0.0002). f The hypomorphic sNPFc00448 mutant (sNPF mutant) flies display significantly extended survival at starvation compared to the controls, and rescue flies (p = 0.0003 compared to rescue construct and parental controls; n = 90 for the four genotypes, 3 replicates). Expressing sNPF in the DLPs only in mutant background by crossing Crz-Gal4>sNPFc00448 flies to UAS-sNPF>sNPFc00448 flies (Rescue) is sufficient to restore starvation resistance to control levels. See also S Fig. 4 for survival data of sNPF mutant flies compared to wild type controls

Assays of carbohydrates and triacylglycerides

Male flies (3 days old) were used to measure concentrations of circulating glucose and trehalose together with whole-body glycogen and trehalose. Pre-weighed flies were decapitated, and hemolymph was collected by centrifugation (3,000g at 4 °C, 6 min). Hemolymph was used to measure circulating glucose and trehalose, whereas whole bodies were used for determination of glycogen and stored trehalose. All parameters were measured with a glucose assay kit involving glucose oxidase and peroxidase (Liquick Cor-Glucose diagnostic kit, Cormay, Poland). Trehalose was converted to glucose by porcine kidney trehalase (Sigma T8778) and glycogen by amyloglucosidase from Aspergillus niger (Sigma 10115). Glucose and trehalose are expressed as concentration in hemolymph, whereas glycogen and body trehalose are given as amount per wet weight. The amount of triacylglycerides (TAG) in fed and starved flies was determined with a Liquick Cor-TG diagnostic kit (Cormay, Poland) and calculated as amount per wet weight or as percent change after 24 h starvation. All genotypes were tested in four to five independent replicates (10–15 flies of each genotype in each sample), and two-way ANOVA was used to compare differences between genotypes.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Amounts of Dilp 2, 3 and 5 RNA were measured in heads by qPCR. RNA was isolated as described in [50], from four biological replicate samples of each genotype tested; 1 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. cDNA was synthesized in triplicates, which were subsequently pooled and diluted for qPCR. Expression of genes of interest was measured relative to that of the reference gene Actin88 (Act) using an ABI Prism 7000 instrument (Applied Biosystems) and a SensiFAST SYBR Hi-ROX Kit (Bioline) under conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Each analytical and standard reaction was performed in three technical replicates. The levels of Dilp2, 3 and 5 and Act were measured with the following primer pairs (all 5′–3′):

Dilp2F: AGCAAGCCTTTGTCCTTCATCTC and Dilp2R: ACACCATACTCAGCACCTCGTTG; Dilp3F: TGTGTGTATGGCTTCAACGCAATG and Dilp3R: CACTCAACAGTCTTTCCA-GCAGGG; Dilp5F: GAGGCACCTTGGGCCTATTC and Dilp5R: CATGTGGTGAGATTCG-GAGC; Act88F: AGGGTGTGATGGTGGGTATG and Act88R: CTTCTCCATGTCGTCCCAGT.

Data analysis

Data were collected and analyzed in Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was performed with Excel and Prism GraphPad v5.0.3. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed to analyze the trends in lifespan for survival curves that were obtained from starvation assays. For qPCR data, carbohydrates and TAG two-way ANOVA were used to compare differences between genotypes.

Results

Colocalization of sNPF and corazonin in adult brain neurosecretory cells

The Drosophila peptide precursor gene snpf (CG13968) encodes four related peptides sNPF1-4 [51, 52], known to activate a single receptor (CG7395) [30, 31]. Henceforth, we refer to these peptides collectively as sNPF. The CRZ precursor gene, Crz (CG3302), encodes CRZ and a putative additional peptide (Crz-associated peptide, CAP) [53, 54]. This CAP has a highly variable sequence among the different Drosophila species and has never been identified as a processed peptide in tissues [53, 55].

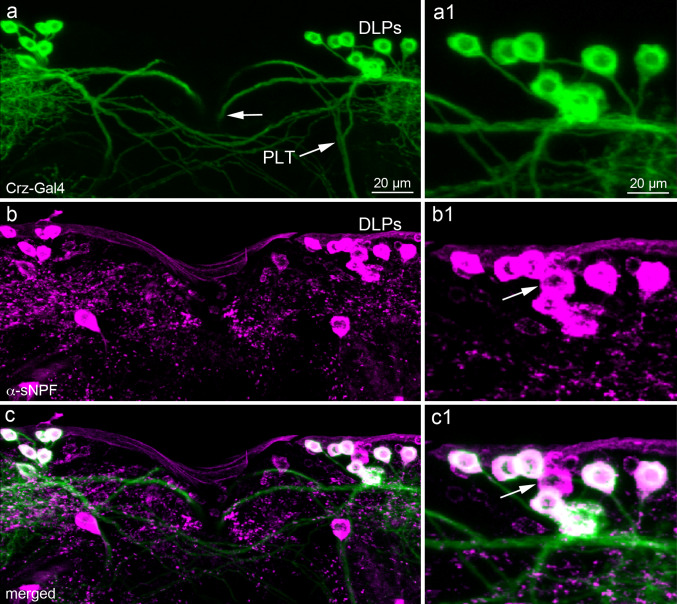

Previous studies have shown that sNPF is produced in numerous neurons in the adult Drosophila brain [32, 49], whereas CRZ (and CAP) is expressed only in bilateral clusters of six to seven dorsolateral neurons, DLPs [53, 56]. In the larval brain, there are three DLPs in each hemisphere, and they coexpress CRZ and sNPF [32]. Here we used sNPF immunocytochemistry combined with Crz-Gal4-driven GFP to show that the six to seven pairs of CRZ-expressing DLPs all display sNPF immunoreactivity also in the adult fly (Fig. 1). Some additional neurons in the same lateral neurosecretory cell cluster express sNPF, but not CRZ (Fig. 1c). The axons of the DLPs extend into the corpora cardiaca, corpora allata, anterior aorta and intestine (see Fig. 2f–h) as also shown earlier [56–58]. In the brain of adult flies, the Crz-Gal4 expression is only seen in these DLPs, and in male flies there is in addition a set of four neurons (ms-sCrz) in the abdominal ganglia [57]. These abdominal neurons do not colocalize sNPF (S. Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A set of lateral neurosecretory cells (DLPs) coexpress short neuropeptide F and corazonin. a–c Seven DLPs in each hemisphere can be visualized with Crz-Gal4 driven GFP (a, green) and sNPF immunolabeling (b, magenta). When images are merged, colocalization of markers is seen in DLPs as white (c). Two sets of axons emerge from the DLPs (indicated in panel a): one set running into the median bundle (at arrow) and another in the posterior lateral tract (PLT). Note that the sNPF immunolabeling is not readily seen in axonal processes. Further details of DLPs are shown in S Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. a1–c1 Details of the labeling of DLP cell bodies. Note that one cell body in the cluster produces sNPF, but not corazonin (arrow)

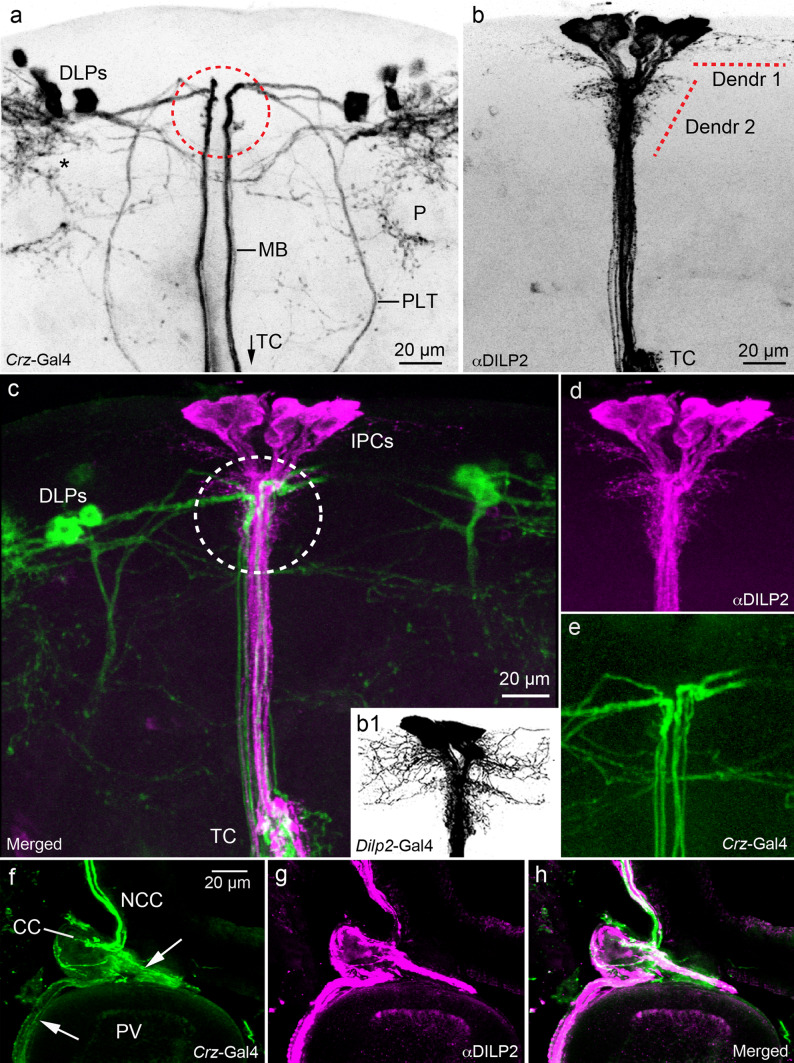

Fig. 2.

Spatial relations between corazonin/sNPF-expressing DLPs and DILP-producing IPCs in the Drosophila brain. a Morphological details of DLPs, a confocal stack of images of Crz-Gal4 expressing DLPs (inverted in Photoshop to increase contrast). Note the two major axon tracts from DLPs running ventrally towards the tritocerebrum (TC more ventrally, see c), the median (MB) and lateral (PLT) tracts. The DLPs arborize also in the dorsal lateral protocerebrum (asterisk) and around the mushroom body peduncle (P). The area indicated by a red circle corresponds to the Dendr 2 area in Fig 2b. b Details of DILP2 immunolabeled IPCs. Branches are seen in two regions of the pars intercerebralis (Dendr 1 and 2) and in the TC (only partly seen here). The bona fide dendrites of IPCs have not been identified, but could be among the pars intercerebralis branches. b1 Note that when using a Dilp2-Gal4 driver to display these Dendr 1 and 2 branches instead of DILP2 antiserum, they appear much more extensive (inverted image). c–e Double marking of the DLPs (green) and IPCs (magenta) to reveal superposition of some of their processes in the pars intercerebralis (circled area in c). See also S Fig. 2 for further details of superposition of DLP and IPC branches in the brain. f–h The axons of the DLPs (green) and IPCs (magenta) run via the corpora cardiaca (CC) nerves (NCC) into the CC and further into nerves (arrows) that supply axon terminations of the proventriculus (PV) foregut and crop duct (not shown). This is another site where the DLPs might regulate IPCs by corazonin and sNPF release

The fidelity of the Crz-Gal4 expression in DLPs has been confirmed by CRZ immunolabeling and in situ hybridization [53, 57]. Thus, we henceforth use the Crz-Gal4 driver as a marker for CRZ/sNPF expressing DLPs in the brain and to drive UAS constructs in these neurons in the subsequent experiments.

Relation between DLPs and insulin-producing cells (IPCs)

Using a combination of Crz-Gal4-driven GFP and anti-DILP2, we detected an apposition of processes of the DLPs and IPCs in the pars intercerebralis, median bundle (tract of axons along brain midline), tritocerebral neuropil, as well as in the corpora cardiaca and anterior midgut of adult flies (Fig. 2, S Fig. 2). The peripheral axons of the IPCs are slightly more extensive than those of the DLPs, and had projections further into the anterior midgut and crop (Fig. 2f–g, see also [13]). The position of the presumed dendrites of the IPCs in relation to processes of the DLPs are shown in Fig. 2c–e and S Fig. 2. It should be noted that the DLPs have further arborizations in the brain close to their cell bodies, around the mushroom body peduncles and in the tritocerebrum/subesophageal ganglion (Fig. 2a, c; S Fig. 2a, d). These branches do not superimpose those of IPCs, suggesting additional action of sNPF and CRZ in other brain circuits. Also in the larval brain and ring gland these DLP and IPC cell systems converge (S Fig. 3a–d). In the ring gland the axon terminations of the DLPs overlap with those of the IPCs mainly in the corpora cardiaca portion; in other regions they differ somewhat in spread (S Fig. 3c, d).

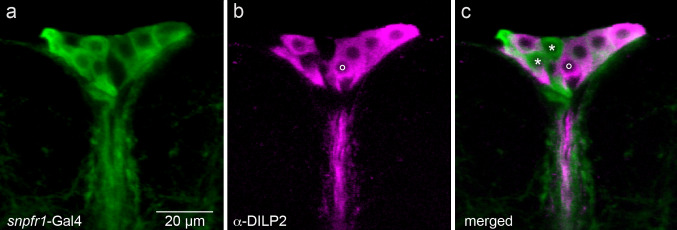

The sNPF receptor is expressed on IPCs in the adult brain

In Drosophila sNPF was shown earlier to regulate the transcription of Dilp2 in brain IPCs and the receptor sNPFR1 demonstrated by immunocytochemistry to be expressed in some of the IPCs [23]. Here we used snpfr1-Gal4-driven GFP combined with antiserum to DILP2 to determine the expression of the sNPFR1 in IPCs. We can show that most, but not all, of the DILP2-immunolabeled IPCs in the adult brain display snpfr1-Gal4 expression (Fig. 3). However, in the brain of the third instar larvae we could not detect any snpfr1-Gal4 expression in IPCs, only in adjacent neurons (S Fig. 3e–h). The combined data from immunocytochemistry [23] and promoter Gal4 expression shown here strongly suggest the presence of sNPFR1 at least in adult IPCs and that the IPCs thus may be directly targeted by sNPF released from the DLPs.

Fig. 3.

The DILP producing IPCs express the sNPF receptor (sNPFR1). a A snpfr1-Gal4 line drives GFP in a set of median neurosecretory cells. b The same section labeled with antiserum to DILP2 displaying cell bodies in the same cluster. c Merging the two channels reveals that the two markers are colocalized in most of the cell bodies in the cluster (except the ones indicated by asterisks and a small ring). Thus, most of the IPCs express the sNPFR1

Using several putative promoter Gal4 drivers (see [59]) for the CRZ receptor CG10698, we screened IPCs and adipokinetic hormone (AKH)-producing cells for GFP expression. Neither in larvae nor in adults could we detect any GFP expression in these cells. It should be noted that these Gal4 lines were produced with short coding sequences of putative enhancer/promoter regions [59], and they are thus unlikely to cover the entire expression pattern. According to the FlyAtlas database (http://www.flyatlas.org/ [60]), the receptor encoded by CG10698 is enriched in the salivary gland and fat body in adult Drosophila.

Manipulation of sNPF and CRZ levels in the DLPs results in altered starvation resistance

Since the sNPFR1 in IPCs has been shown to regulate insulin signaling in Drosophila [22, 23], we tested whether manipulations of sNPF in the DLPs has an effect on physiology that could be linked to insulin action. One aspect of insulin signaling in Drosophila is regulation of responses to stress, such as survival at starvation (stress resistance) [14]. Thus, we tested survival of transgene flies that had access to water, but no food. We employed the Gal4-UAS system to knock down or over express sNPF in the DLPs using the Crz-Gal4 driver crossed to UAS-snpf-RNAi and UAS-snpf, respectively. In all experiments we used 3- to 6-day-old male flies, unless otherwise indicated.

Flies with diminished sNPF levels in the DLPs (Crz-Gal4 > snpf-RNAi) display an extended life span when starved, compared to their parental controls (Fig. 4a). Median life span increased by about 38 %, from 37 to 51 h (p < 0.0001 compared to each control; Log-rank test, n = 118–180 for each genotype). Conversely, overexpression of sNPF in the DLPs (Crz-Gal4 > UAS-snpf) resulted in reduced survival when exposed to starvation (Fig 4b). Median life span was reduced by about 21 %, from 38 to 30 h (p < 0.0001 to controls, n = 92–105 for each genotype).

Since CRZ is colocalized with sNPF in the DLPs, we next diminished CRZ levels in these cells and monitored survival of starved flies. Knockdown of CRZ in the DLPs (Crz-Gal4 > Crz-RNAi) also resulted in increased survival at starvation (Fig 4c). Median life span increased by about 43 %, from 30 to 43 h (P < 0.0001 to controls, n = 69–75 for each genotype).

To affect release of both peptides in the DLPs, we silenced neurons with a constitutively active potassium channel, dOrk1 [48], which hyperpolarizes the neuronal membranes. This hyperpolarization of DLPs has been performed in an earlier study of CRZ signaling and affected stress resistance [38]. Starved flies with hyperpolarized DLPs (Crz-Gal4 > UAS-Ork) displayed an extended life span in comparison to controls (Fig. 4d). Median life span increased by about 70 %, from 31 to 53 h (p < 0.0001 to controls, n = 73–85 for each genotype).

We also performed CRZ knockdown in sNPF-producing cells by driving Crz-RNAi with an snpf-Gal4 line. Since the only cells that co-express sNPF and CRZ are the DLPs, this should produce the same phenotype as when manipulating peptide levels in DLPs with the Crz-Gal4. Indeed, flies with CRZ diminished in snpf-Gal4-expressing neurons display increased resistance to starvation (Fig. 4e, p < 0.0001 to controls, n = 180 for each genotype).

Our data so far suggest that both sNPF and CRZ in the DLPs affect the response to starvation; knockdown of each extends survival, and overexpression of sNPF abbreviates survival at starvation.

Next, we adopted another approach to investigate the role of sNPF in the DLPs. We utilized hypomorphic sNPF mutant flies (sNPFc00448), known to have strongly reduced sNPF peptide expression globally and reduced insulin signaling [23], for rescue experiments. Here, we show that the sNPFc00448 mutant flies display an extended lifespan when starved compared to controls (Fig. 4f, S Fig. 4) (P < 0.0001 to all controls, n = 76–108 for each genotype). We generated a recombinant strain that rescues the sNPF expression only in the DLPs in the mutant background (sNPFc00448/UAS-snpf > sNPFc00448/Crz-Gal4). We tested the rescue construct along with mutant flies (sNPFc00448) and the parental flies (sNPFc00448/UAS-snpf and sNPFc00448/Crz-Gal4) to monitor their survival when starved. We hypothesized that intact sNPF signaling in the DLPs in the rescue construct should result in a starvation phenotype similar to the parental controls (and wild type flies, S Fig. 4) in contrast to the increased survival of the sNPF mutants. Indeed, the flies with sNPF rescued in DLPs displayed a survival not significantly different from controls (p = 0.7542 compared to controls, n = 90 for each genotype), whereas the sNPFc00448 flies displayed an extended life span (p = 0.0003 compared to the rescue construct and parental controls, Fig. 4f).

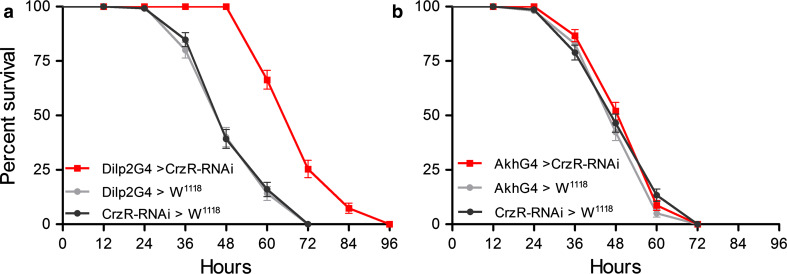

Knockdown of corazonin receptor in IPCs increases starvation resistance

It has already been shown that the sNPF receptor sNPFR1 is expressed in IPCs and that targeted manipulations of sNPFR1 affects insulin signaling [23]. Here we tested the effect of CRZ receptor (CrzR; CG10698) knockdown in IPCs on resistance to starvation, using Dilp2-Gal4 flies crossed to UAS-CrzR-RNAi. The CrzR-RNAi in IPCs drastically extends survival of starved flies (Fig. 5a) (p < 0.0001 compared to controls, n = 120 for each genotype). Since the AKH-producing cells are also close to the terminations of the DLPs, we tested the effect of driving CrzR-RNAi in these AKH cells. We utilized an Akh-Gal4 driver [61] to knock down the CrzR in the AKH cells, but observed no significant effect on survival of starved flies compared to controls (Fig. 5b, n = 150 for each genotype). These findings suggest that IPCs express the CrzR, but from our experiments here we cannot conclusively state that the AKH-producing cells do not express this receptor.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of the corazonin receptor in IPCs, but not AKH-producing cells increases starvation resistance. a Diminishment of the corazonin receptor by CrzR-RNAi targeted to insulin-producing cells (Dilp2G4 > CrzR-RNAi) extends the life span in starving flies compared to controls (P < 0.0001 to both controls; log-rank test, n = 120 for the three genotypes, three replicates). b Knockdown of the corazonin receptor in AKH-producing cells (AkhG4 > CrzR-RNAi) does not affect survival at starvation (no significant difference among the three genotypes; n = 150 for the three genotypes, three replicates)

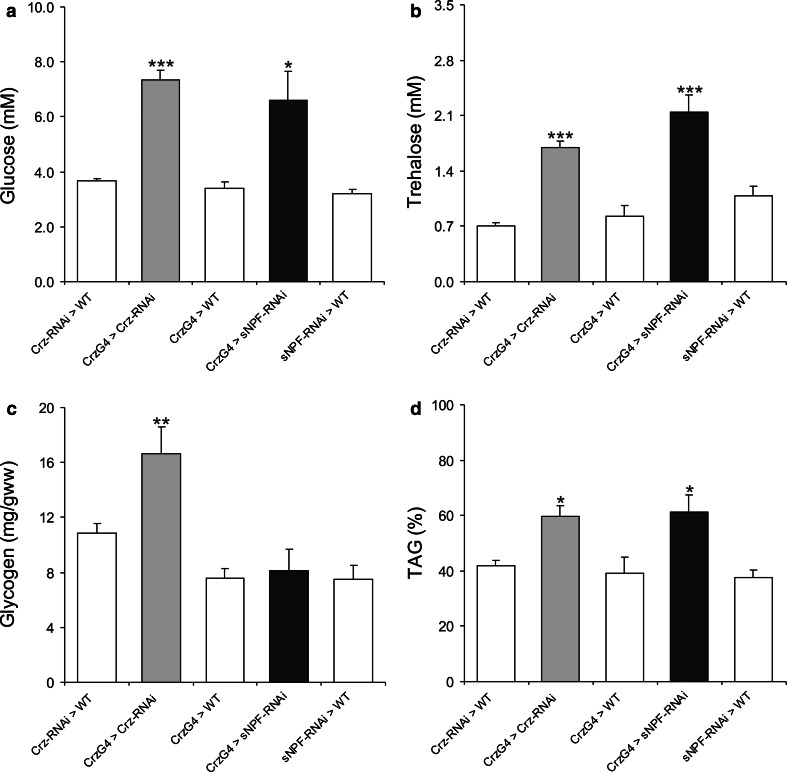

Diminished sNPF and CRZ in DLPs affect circulating carbohydrate and lipid levels

Previous studies have shown that DILPs produced by the brain IPCs have roles in the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis [6, 12, 14, 62]. Therefore, we assayed carbohydrate and triacylglyceride (TAG) levels to determine whether interference with sNPF and CRZ in DLPs affects metabolism, to suggest action of the two peptides on IPCs, and possibly insulin signaling.

We measured the hemolymph levels of glucose and trehalose in normally fed male flies of different genotypes. Flies with sNPF or CRZ knockdown in DLPs displayed significantly increased hemolymph levels of glucose (Fig. 6a) and trehalose (Fig. 6b) compared to parental controls (two-way ANOVA, statistics are shown in figure legends for all experiments). As a comparison, we measured whole-body trehalose in the same experimental flies (normally fed) and noted no significant changes in any of the peptide knockdown flies (S Fig. 5a).

Fig. 6.

Levels of carbohydrates and lipids are affected by knockdown of sNPF and corazonin in DLPs. In a–d data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n = 40–75 for each genotype, and experiments were performed in four to five independent replicates. a Both CRZ and sNPF knockdown in DLPs using the Crz-Gal4 (CrzG4 > sNPF-RNAi and CrzG4 > Crz-RNAi) results in increased glucose in hemolymph of fed flies compared to controls (WT = w 1118). b Also trehalose levels increase in both knockdown flies (fed normally). c Glycogen levels in normally fed flies are higher after CRZ-RNAi in the DLPs (CrzG4 > Crz-RNAi) than controls, but were not significantly changed after sNPF-RNAi in the same cells (CrzG4 > sNPF-RNAi). d The decrease in TAG levels after 24 h starvation was significantly different in both the CRZ and sNPF knockdown in DLPs

Carbohydrates are stored as glycogen in Drosophila, and we measured whole-body glycogen levels in normally fed flies (0 h) and flies starved for 24 h. Glycogen levels were significantly higher in fed CRZ knockdown flies than in controls (Fig. 6c). However, snpf-RNAi in DLPs did not affect glycogen levels in fed flies (Fig. 6c). In flies that were starved for 24 h, there was no significant difference between the different genotypes; all displayed decreased glycogen (S Fig. 5b).

Using the same genotypes we also measured the TAG levels in normally fed flies (0 h) and flies starved for 24 h. There was no significant difference in TAG levels of normally fed flies of the different genotypes (S Fig. 5c). However, after 24 h starvation, both peptide knockdown flies displayed a significantly smaller decrease in TAG levels compared to controls (Fig. 6d).

Our results suggest that the DLPs and their two peptides CRZ and sNPF play a role in the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis. Both glucose and trehalose levels in the hemolymph were affected in normally fed flies, and TAG levels were affected in starved flies. Since sNPF has been implicated in the regulation of IPCs and insulin signaling, it is likely that the sNPF and CRZ knockdown in DLPs, which results in carbohydrate and TAG phenotypes, is caused by decreased IPC activity and maybe diminished insulin signaling.

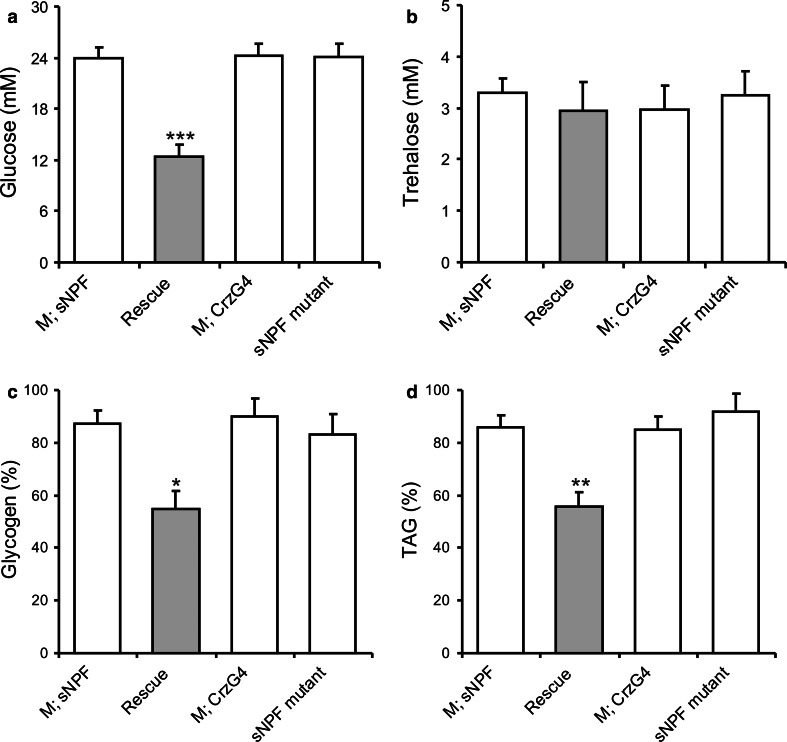

To extend this analysis we explored the sNPF mutant flies (sNPFc00448) and the rescue of the sNPF phenotype in DLPs in assays of carbohydrates and TAG. In mutant flies (including parental strains in mutant background), hemolymph glucose levels were significantly higher than in flies with sNPF rescued in DLPs (Fig. 7a). This suggests that the altered metabolism in sNPF mutants can be restored by rescue in DLPs alone. Trehalose levels in hemolymph were not significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 7b). However, whole-body glycogen (Fig. 7c) and TAG levels (Fig. 7d) were different between genotypes after 24 h starvation. Mutant flies with sNPF restored in DLPs displayed a more drastic reduction of glycogen and TAG than mutants. Levels of body trehalose, glycogen and TAG in fed flies are shown in S Fig. 6. Collectively, these results suggest that sNPF mutant flies display altered metabolism and that this can be partly restored by sNPF rescue in DLPs alone.

Fig. 7.

Levels of carbohydrates and lipids are affected in sNPF mutants and rescued by sNPF in DLPs. In a–d data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n = 40–75 for each genotype, and experiments were performed in four to five independent replicates. In genotypes similar to Fig. 4f, we tested the effect of the sNPF mutation (sNPF c00448 ) on carbohydrate and triacylglyceride (TAG) levels and the effect of rescuing sNPF expression only in DLPs in mutant background (Rescue). a The sNPF mutant and the two controls (M, sNPF; M, CrzG4), which are sNPF mutant flies crossed to the parental strains, display increased glucose levels in hemolymph in fed flies. Rescue of the sNPF expression in DLPs (Crz-Gal4/sNPFc00448 flies crossed to UAS-snpf-/sNPFc00448 flies, Rescue) leads to a significantly decreased level of glucose. b Trehalose levels in fed flies, however, are the same in all genotypes. c Change in body glycogen levels after 24 h starvation (% glycogen, with fed level set to 100 %) is significantly lower in the rescue flies than in mutant flies (and parental strains). d Also body TAG levels (% TAG) drop more after starvation than mutants and controls

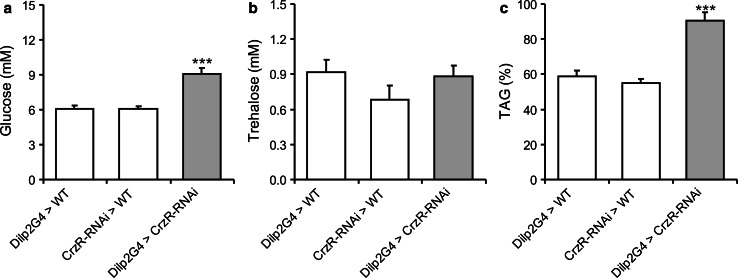

Finally, we monitored the effect of CrzR-RNAi in IPCs on carbohydrate and lipid levels to strengthen the evidence for an effect of CRZ on IPCs and indirectly the presence of the CrzR in these cells. Knockdown of the CrzR in IPCs resulted in significantly increased levels of glucose (Fig. 8a), but not trehalose (Fig. 8b), compared to parental controls. The decrease in TAG levels after 24 h starvation was reduced after CrzR-RNAi in IPCs (Fig. 8c). These data indicate altered metabolism after CrzR knockdown that might be due to decreased insulin signaling, and thus it appears as if the IPCs are directly targeted by CRZ.

Fig. 8.

Knockdown of the corazonin receptor in IPCs affects carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. In a–c, data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001, n = 40–75 for each genotype, and experiments were performed in four to five independent replicates. a Knockdown of the corazonin receptor in IPCs, using a Dilp2-gal4 driver (Dilp2G4 > CrzR-RNAi), results in an increase in hemolymph glucose in fed flies. b Trehalose levels in fed flies were not significantly altered after CrzR-knockdown. c Triacylglyceride (TAG) levels were significantly higher after CrzR knockdown in flies that had been starved for 24 h. The TAG levels are expressed as % remaining after starvation

In the context of the above experiments, all flies were weighed, and we therefore determined whether the CRZ and sNPF interference had any effects on growth. We found no significant difference between fly weights after snpf- and Crz-RNAi in DLPs or CrzR-RNAi in IPCs, but snpf mutants were significantly lighter than controls and the weight partly restored by sNPF rescue in DLPs (data not shown).

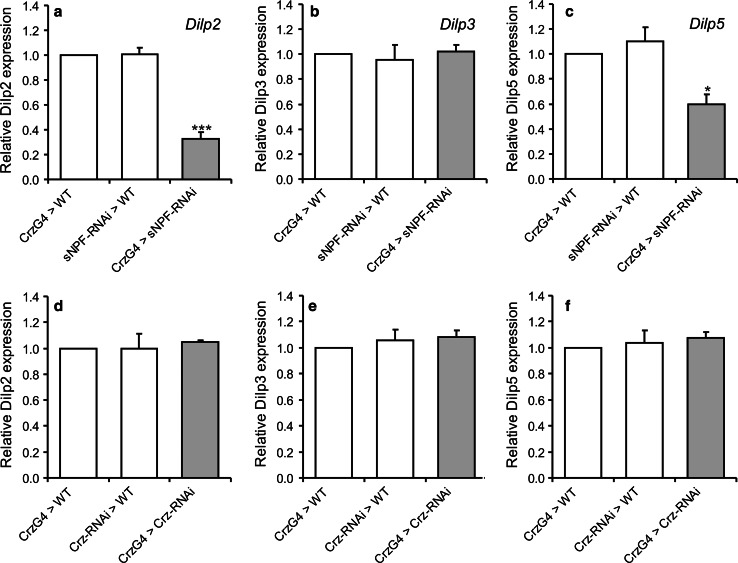

Diminished sNPF, but not CRZ, in DLPs affects Dilp transcript levels

To further test for effects of sNPF and CRZ on the IPCs, we analyzed transcript levels of Dilp2, 3 and 5 in brain by qPCR after targeted RNAi in DLPs. Knockdown of sNPF in DLPs using the Crz-Gal4 results in a significant decrease in Dilp2 and Dilp5, but not Dilp3 transcripts in the brain (Fig. 9a–c). This is partly consistent with data from Lee et al. [23]. These authors reported increases in Dilp1 and 2 transcripts after global overexpression of sNPF and overexpression of the sNPFR1 in IPCs, but did not measure Dilp3 and Dilp5 levels. On the other hand, we found that knockdown of CRZ in DLPs does not affect Dilp transcript levels in brain (Fig. 9d–f). This suggests that sNPF and CRZ have different actions on IPCs; both affect starvation resistance and metabolism, but only sNPF alters Dilp transcription.

Fig. 9.

Dilp transcription in brain is affected by sNPF, but not CRZ knockdown in DLPs. a–c Relative expression of Dilp2, 3 and 5 after sNPF-RNAi in DLPs (CrzG4 > sNPF-RNAi) was measured in head extracts. Only Dilp2 and 5 decrease significantly (two-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, n = 4 for each genotype). d–f Relative expression of Dilp2, 3 and 5 after Crz-RNAi in DLPs (CrzG4 > Crz-RNAi). No significant difference in expression was seen between genotypes (two-way ANOVA, n = 4 for each genotype)

Discussion

We have identified a bilateral set of peptidergic neurons, DLPs, in the lateral neurosecretory cell clusters that regulate activity in the brain IPCs of Drosophila. These DLPs produce both sNPF and CRZ. Thus, we have found one major neuronal source of sNPF that may be responsible for the previously described regulation of insulin-producing cells [22, 23]. These earlier experiments had not identified any specific sNPF-expressing neurons that act on the IPCs. We could also provide a further link in the role of CRZ in stress responses proposed from earlier studies [36–38]. Knockdown of CRZ in the DLPs results in the same starvation resistance and metabolic phenotypes as when sNPF is diminished in these cells or when the DLPs are silenced by expressing an active potassium channel. Our results, combined with those of Lee et al. [23], suggest that sNPF released from DLPs target the IPCs to increase production, and probably release of DILPs, and that this IPC activation affects stress resistance and metabolism. Whereas sNPF acts directly on the IPCs via the receptor sNPFR1, to affect Dilp transcription and possibly insulin release, we did not identify the mechanism by which the CRZ receptor acts in IPCs. Our experiments, however, indicate the presence of the CRZ receptor in IPCs since CrzR-RNAi in these cells increases starvation resistance, and increases circulating glucose and body TAG. Since we did not employ conditional interference with sNPF and CRZ in adult flies, we cannot exclude developmental effects of the manipulations. However, the sNPFR1 seems not to be expressed in larval IPCs, and we did not detect any effects of targeted sNPF and CRZ interference on growth.

We could confirm that the majority of the IPCs express the sNPFR1 in adult Drosophila, and that the axon terminations of the DLPs impinge on branches of the IPCs both in the dorsal brain (pars intercerebralis and median bundle) and in the tritocerebrum, as well as in the corpora cardiaca and anterior intestine. Lee et al. [23] showed that expression of a dominant negative form of the receptor sNPFR1 in IPCs decreased Dilp transcription and overexpression of sNPFR1 in the same cells produced the opposite effect. For analysis of interference with sNPF peptide, these authors used either a hypomorphic snpf mutant (sNPFc00448 ) or drove snpf-RNAi or sNPF overexpression with a Gal4 driver (MJ94) with widespread expression in sensory neurons [23]. Neither of these approaches identified neurons directly targeting the IPCs. We obtained the same phenotypes with the sNPFc00448 mutant as with the snpf-RNAi only in the DLPs, and importantly we could rescue the wild-type phenotype in stress resistance and metabolism by expressing sNPF only in the DLPs of the sNPF mutant flies. Thus, it appears that the DLPs are sufficient for this particular sNPF-mediated regulation of the IPCs.

Interestingly, the sNPF-producing DLPs coexpress CRZ, a peptide proposed to be multifunctional in various insects, including regulation of stress responses [36, 37]. CRZ has been implicated in the initiation of ecdysis [63] and maybe clock functions [64] in the moth Manduca sexta, in the regulation of pigmentation in locusts [65], in modulation of heart muscle contractions in cockroaches and a mosquito [66–68], and in Drosophila in the regulation of various stress responses [36, 38] and maybe in functions downstream of the principal clock neurons [53], as well as in the regulation of female fecundity [69]. Another finding relevant to the present study is that mutation of Klumpfuss, a gene that is involved in the regulation of food intake, leads to an upregulation of the Crz gene transcript that is larger than for all other neuropeptide genes [70].

Lee and colleagues [57] showed that genetic ablation of the DLPs resulted in a slight, but statistically significant, decrease in whole-body trehalose levels. These authors were at the time not aware of sNPF being colocalized in the DLPs and thus interpreted the phenotype after DLP ablation as resulting from CRZ depletion only. Another study demonstrated that ablation or electrical silencing of the CRZ-producing DLPs resulted in extended survival and hyperactivity of flies experiencing metabolic stress (starvation), whereas stimulation of the same neurons by expressing an active Na-channel resulted in the opposite phenotype [38]. We confirmed the starvation resistance phenotype obtained after inactivation of DLPs (using UAS-Ork) and diminishing CRZ (by RNAi) in these cells.

The receptor for CRZ (CG10698) is ancestrally related to mammalian GnRH receptors [34, 35, 61, 71] and is expressed on the fat body and heart, as well as in lower levels in the CNS (see FlyAtlas [60]). Our data show that knockdown of CRZ and sNPF in DLPs results in increased hemolymph levels of trehalose and glucose, which would suggest that CRZ and sNPF act on the IPCs to stimulate DILP release. Our data also indicate that CRZ knockdown leads to increased stores of glycogen in fed flies and that TAG levels remain higher after starvation than in controls. Similar results were obtained after CrzR-RNAi in IPCs, suggesting that CRZ acts on the IPCs to mediate the effects on metabolism.

Since knockdown of either sNPF or CRZ in the DLPs, and the silencing of the DLPs, produced the same phenotypes in all assays, except Dilp transcription, it is clear that these peptides cooperate to regulate metabolism and stress responses. A question is whether the peptides released from the DLPs target the same cells or if CRZ additionally acts as a circulating hormone. In other words, are the sNPF and CRZ receptors expressed on the same or partly different target cells? It seems possible that sNPF and CRZ target IPCs and that CRZ additionally acts on the fat body, known to express the CRZ receptor, but not sNPFR1 (FlyAtlas). Indeed, preliminary experiments reveal that CrzR-RNAi in the fat body increases starvation resistance (unpublished observations). Our analysis of receptor expression reveals sNPFR1 on IPCs, but not on AKH cells. The CRZ receptor was not detected on either of these cell types, but this may be a result of the incomplete expression seen in the Gal4 lines we tested. Indirect data, where CrzR-RNAi in the IPCs, but not AKH cells, results in increased starvation resistance and altered metabolism, strongly suggest that the receptor is expressed in the IPCs.

In summary, we can propose that the sNPF and CRZ expressing DLPs target the brain IPCs that express the CrzR and sNPFR1. These receptors seem to activate different downstream signal pathways in the IPCs: the activated sNPFR1 stimulates transcription of Dilp2 and Dilp5, and the CrzR acts stimulatory via some other mechanism. Both receptors may trigger activity in IPCs that leads to DILP release and subsequent effects on metabolism and stress resistance. Furthermore, the CRZ- and sNPF-producing DLPs are known to express receptors for the diuretic hormones DH31 and DH44 and one of the allatostatin-A receptors (DAR-2) [36, 39]. In Drosophila, the peptide ligands of these receptors are expressed both in neurons of the brain and endocrine cells of the midgut [40, 72–74]. It has been suggested that the DHs and allatostatin-A of gut endocrines function as circulating hormones to signal nutritional status or gut distension to the DLPs of the brain [36, 39]. This would provide a signaling pathway from the gut to the IPCs of the brain that can operate as a complement to the possible nutrient signaling from the fat body and/or circulation to the brain.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

S Fig 1 In male flies there is a small set of Crz-Gal4 expressing neurons in the last abdominal segment that do not produce sNPF. As seen in a - c Crz-Gal4 and sNPF expressing neurons in abdominal ganglia are distinct. Thus the use of the Crz-Gal4 driver to interfere with sNPF expression will only affect the two sets of DLPs in the brain. (TIFF 1,941 kb)

S Fig 2 Morphological details of superposition of DLPs and IPCs in the Drosophila brain. a The DLPs are displayed with Crz-Gal4-driven GFP (green) and IPCs with DILP2 immunolabeling (magenta). The DLPs send axons along the median bundle (MB) and posterior lateral tract (PLT), whereas the axons of the IPCs run in the MB. b Higher magnification of the same neurons showing the tight spatial relations between axon branches of the two neuron types in the median bundle. The region indicated with double arrow (Dendr) is where the IPCs (and DLPs to a lesser extent) have short lateral processes. c1 - c3 Details of the region indicated by double arrow in 1b. Note that both Crz-Gal4 (green) and DILP2 immunolabeled (magenta) axons have short side branches in this region and these may represent functional contacts between the two neuron types. d1 - d2 Another region where DLPs may contact IPCs is in the tritocerebrum (TC) on either side of the esophageal foramen (EF). Clearly the DLPs arborize in additional areas ventral to the TC, including the subesophageal ganglion, suggesting additional outputs and/or inputs. (TIFF 4,089 kb)

S Fig 3 Corazonin/sNPF, DILP2 and sNPFR1-expressing neurons in the third instar larva. a - c Crz-Gal4 (green) and DILP2 immunreactive neurons (aDILP2; magenta) in the larval brain and ring gland (RG). The DLPs and IPCs have processes that superimpose in the corpora cardiaca (CC) of the ring gland and in portions of the brain. For some reason the cell bodies of the mushroom body Kenyon cells (asterisk) display non-specific immunolabeling with anti-DILP2. d Detail of a ring gland where DLP and IPC processes superimpose in the CC, but not corpora allata (CA) of the ring gland (encircled). e - h Using the snpfr-Gal4 driver it appears that the IPCs (labeled with anti-DILP2) do not express the sNPF receptor in the larva. The "white cells" seen in g are above each other in this image stack and do not colocalize the markers. (TIFF 2,398 kb)

S Fig. 4 Hypomorphic sNPF mutant flies live longer when starved. The hypomorphic sNPF c00448 mutant (sNPF mutant) flies display significantly extended survival at starvation compared to two wild type controls (w 1118 and Oregon; OR) (p < 0.0001; n= 76-108 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). (TIFF 299 kb)

S Fig. 5 Whole body carbohydrate and lipid levels after corazonin and sNPF knockdown in DLPs. a Whole body trehalose levels (mg/g wet weight) in knockdown flies and parental controls is the same in all genoypes in fed flies. b Change in glycogen levels after 24 h starvation is also the same in all genotypes. c The TAG levels (mg/g wet weight) in normally fed flies do not differ significantly between genotypes. (TIFF 927 kb)

S Fig. 6 Whole body carbohydrate and lipid levels after in sNPF mutant flies and after rescue of sNPF in DLPs (in mutant background), compared to parental mutant flies. In a - c flies were fed normal food. a No difference between genotypes for whole body trehalose levels. b With sNPF rescue in DLPs the glycogen levels are higher than in mutants and controls. (**= p<0,01; Two way ANOVA). c Levels of TAG in fed flies are significantly higher after rescue of sNPF in DLPs (**= p<0.01; Two way ANOVA). (TIFF 535 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Broughton, E. Hafen, P. Léopold, J.H. Park, J.A. Veenstra, K. Yu, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Harvard Stock Center, and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center for flies and reagents. Å.M.E. Winther is gratefully acknowledged for technical advice. This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Carl Trygger Foundation (both to DRN).

References

- 1.Brogiolo W, Stocker H, Ikeya T, Rintelen F, Fernandez R, et al. An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr Biol. 2001;11:213–221. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonova Y, Arik AJ, Moore W, Riehle MR, Brown MR. Insulin-like peptides: structure, signaling, and function. In: Gilbert LI, editor. Insect endocrinology. New York: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2012. pp. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannakou ME, Partridge L. Role of insulin-like signalling in Drosophila lifespan. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Géminard G, Arquier N, Layalle S, Bourouis M, Slaidina M, et al. Control of metabolism and growth through insulin-like peptides in Drosophila . Diabetes. 2006;55:S5–S8. doi: 10.2337/db06-S001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span–from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker KD, Thummel CS. Diabetic larvae and obese flies—emerging studies of metabolism in Drosophila . Cell Metab. 2007;6:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broughton S, Alic N, Slack C, Bass T, Ikeya T, et al. Reduction of DILP2 in Drosophila triages a metabolic phenotype from lifespan revealing redundancy and compensation among DILPs. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grönke S, Clarke DF, Broughton S, Andrews TD, Partridge L. Molecular evolution and functional characterization of Drosophila insulin-like peptides. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombani J, Andersen DS, Leopold P. Secreted peptide Dilp8 coordinates Drosophila tissue growth with developmental timing. Science. 2012;336:582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1216689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garelli A, Gontijo AM, Miguela V, Caparros E, Dominguez M. Imaginal discs secrete insulin-like peptide 8 to mediate plasticity of growth and maturation. Science. 2012;336:579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1216735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao C, Brown MR. Localization of an insulin-like peptide in brains of two flies. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:317–321. doi: 10.1007/s004410100367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science. 2002;296:1118–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.1070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cognigni P, Bailey AP, Miguel-Aliaga I. Enteric neurons and systemic signals couple nutritional and reproductive status with intestinal homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;13:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broughton SJ, Piper MD, Ikeya T, Bass TM, Jacobson J, et al. Longer lifespan, altered metabolism, and stress resistance in Drosophila from ablation of cells making insulin-like ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3105–3110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405775102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broughton SJ, Slack C, Alic N, Metaxakis A, Bass TM, et al. DILP-producing median neurosecretory cells in the Drosophila brain mediate the response of lifespan to nutrition. Aging Cell. 2010;9:336–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karpac J, Hull-Thompson J, Falleur M, Jasper H. JNK signaling in insulin-producing cells is required for adaptive responses to stress in Drosophila . Aging Cell. 2009;8:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridell YW, Hoh M, Kreneisz O, Hosier S, Chang C, et al. Increased uncoupling protein (UCP) activity in Drosophila insulin-producing neurons attenuates insulin signaling and extends lifespan. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:699–713. doi: 10.18632/aging.100067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreneisz O, Chen X, Fridell YW, Mulkey DK. Glucose increases activity and Ca(2+) in insulin-producing cells of adult Drosophila . NeuroReport. 2010;21:1116–1120. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283409200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashcroft FM, Gribble FM. ATP-sensitive K+ channels and insulin secretion: their role in health and disease. Diabetologia. 1999;42:903–919. doi: 10.1007/s001250051247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geminard C, Rulifson EJ, Leopold P. Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila . Cell Metab. 2009;10:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombani J, Raisin S, Pantalacci S, Radimerski T, Montagne J, et al. A nutrient sensor mechanism controls Drosophila growth. Cell. 2003;114:739–749. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00713-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KS, You KH, Choo JK, Han YM, Yu K. Drosophila short neuropeptide F regulates food intake and body size. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50781–50789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KS, Kwon OY, Lee JH, Kwon K, Min KJ, et al. Drosophila short neuropeptide F signalling regulates growth by ERK-mediated insulin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:468–475. doi: 10.1038/ncb1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan DD, Zimmermann G, Suyama K, Meyer T, Scott MP. A nucleostemin family GTPase, NS3, acts in serotonergic neurons to regulate insulin signaling and control body size. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1877–1893. doi: 10.1101/gad.1670508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crocker A, Shahidullah M, Levitan IB, Sehgal A. Identification of a neural circuit that underlies the effects of octopamine on sleep: wake behavior. Neuron. 2010;65:670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birse RT, Söderberg JA, Luo J, Winther ÅM, Nässel DR. Regulation of insulin-producing cells in the adult Drosophila brain via the tachykinin peptide receptor DTKR. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:4201–4208. doi: 10.1242/jeb.062091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enell LE, Kapan N, Söderberg JA, Kahsai L, Nässel DR. Insulin signaling, lifespan and stress resistance are modulated by metabotropic GABA receptors on insulin producing cells in the brain of Drosophila . PLoS One. 2010;5:e15780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo J, Becnel J, Nichols CD, Nässel DR. Insulin-producing cells in the brain of adult Drosophila are regulated by the serotonin 5-HT(1A) receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:471–484. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0789-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KS, Hong SH, Kim AK, Ju SK, Kwon OY, et al. Processed short neuropeptide F peptides regulate growth through the ERK-insulin pathway in Drosophila melanogaster . FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2573–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng G, Reale V, Chatwin H, Kennedy K, Venard R, et al. Functional characterization of a neuropeptide F-like receptor from Drosophila melanogaster . Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:227–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mertens I, Meeusen T, Huybrechts R, De Loof A, Schoofs L. Characterization of the short neuropeptide F receptor from Drosophila melanogaster . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nässel DR, Enell LE, Santos JG, Wegener C, Johard HA. A large population of diverse neurons in the Drosophila central nervous system expresses short neuropeptide F, suggesting multiple distributed peptide functions. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewes RS, Taghert PH. Neuropeptides and neuropeptide receptors in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 2001;11:1126–1142. doi: 10.1101/gr.169901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park Y, Kim YJ, Adams ME. Identification of G protein-coupled receptors for Drosophila PRXamide peptides, CCAP, corazonin, and AKH supports a theory of ligand-receptor coevolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11423–11428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162276199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cazzamali G, Saxild N, Grimmelikhuijzen C. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a Drosophila corazonin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veenstra JA. Does corazonin signal nutritional stress in insects? Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39:755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boerjan B, Verleyen P, Huybrechts J, Schoofs L, De Loof A. In search for a common denominator for the diverse functions of arthropod corazonin: a role in the physiology of stress? Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010;166:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y, Bretz CA, Hawksworth SA, Hirsh J, Johnson EC. Corazonin neurons function in sexually dimorphic circuitry that shape behavioral responses to stress in Drosophila . PLoS One. 2010;5:e9141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson EC, Shafer OT, Trigg JS, Park J, Schooley DA, et al. A novel diuretic hormone receptor in Drosophila: evidence for conservation of CGRP signaling. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1239–1246. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabrero P, Radford JC, Broderick KE, Costes L, Veenstra JA, et al. The Dh gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a diuretic peptide that acts through cyclic AMP. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:3799–3807. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.24.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li XF, Bowe JE, Mitchell JC, Brain SD, Lightman SL, et al. Stress-induced suppression of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator in the female rat: a novel neural action for calcitonin gene-related peptide. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1556–1563. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XF, Bowe JE, Lightman SL, O’Byrne KT. Role of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-2 in stress-induced suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 2005;146:318–322. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahsai L, Carlsson MA, Winther ÅM, Nässel DR. Distribution of metabotropic receptors of serotonin, dopamine, GABA, glutamate, and short neuropeptide F in the central complex of Drosophila . Neuroscience. 2012;208:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi SH, Lee G, Monahan P, Park JH. Spatial regulation of Corazonin neuropeptide expression requires multiple cis-acting elements in Drosophila melanogaster . J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1184–1195. doi: 10.1002/cne.21594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee G, Park JH. Hemolymph sugar homeostasis and starvation-induced hyperactivity affected by genetic manipulations of the adipokinetic hormone-encoding gene in Drosophila melanogaster . Genetics. 2004;167:311–323. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikeya T, Galic M, Belawat P, Nairz K, Hafen E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila . Curr Biol. 2002;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nitabach MN, Blau J, Holmes TC. Electrical silencing of Drosophila pacemaker neurons stops the free-running circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:485–495. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johard HA, Enell LE, Gustafsson E, Trifilieff P, Veenstra JA, et al. Intrinsic neurons of Drosophila mushroom bodies express short neuropeptide F: relations to extrinsic neurons expressing different neurotransmitters. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1479–1496. doi: 10.1002/cne.21636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez-Ayala DJ, Sanz A, Vartiainen S, Kemppainen KK, Babusiak M, et al. Expression of the Ciona intestinalis alternative oxidase (AOX) in Drosophila complements defects in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vanden Broeck J. Neuropeptides and their precursors in the fruitfly, Drosophila melanogaster . Peptides. 2001;22:241–254. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(00)00376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nässel DR, Wegener C. A comparative review of short and long neuropeptide F signaling in invertebrates: any similarities to vertebrate neuropeptide Y signaling? Peptides. 2011;32:1335–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi YJ, Lee G, Hall JC, Park JH. Comparative analysis of Corazonin-encoding genes (Crz’s) in Drosophila species and functional insights into Crz-expressing neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2005;482:372–385. doi: 10.1002/cne.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veenstra JA. Isolation and structure of the Drosophila corazonin gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:292–296. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yew JY, Wang Y, Barteneva N, Dikler S, Kutz-Naber KK, et al. Analysis of neuropeptide expression and localization in adult Drosophila melanogaster central nervous system by affinity cell-capture mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1271–1284. doi: 10.1021/pr800601x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cantera R, Veenstra JA, Nässel DR. Postembryonic development of corazonin-containing neurons and neurosecretory cells in the blowfly, Phormia terraenovae . J Comp Neurol. 1994;350:559–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee G, Kim KM, Kikuno K, Wang Z, Choi YJ, et al. Developmental regulation and functions of the expression of the neuropeptide corazonin in Drosophila melanogaster . Cell Tissue Res. 2008;331:659–673. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siegmund T, Korge G. Innervation of the ring gland of Drosophila melanogaster . J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:481–491. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010319)431:4<481::AID-CNE1084>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pfeiffer BD, Jenett A, Hammonds AS, Ngo TT, Misra S, et al. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bharucha KN, Tarr P, Zipursky SL. A glucagon-like endocrine pathway in Drosophila modulates both lipid and carbohydrate homeostasis. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:3103–3110. doi: 10.1242/jeb.016451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teleman AA. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila . Biochem J. 2010;425:13–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim YJ, Spalovska-Valachova I, Cho KH, Zitnanova I, Park Y, et al. Corazonin receptor signaling in ecdysis initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6704–6709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wise S, Davis NT, Tyndale E, Noveral J, Folwell MG, et al. Neuroanatomical studies of period gene expression in the hawkmoth, Manduca sexta . J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:366–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tawfik AI, Tanaka S, De Loof A, Schoofs L, Baggerman G, et al. Identification of the gregarization-associated dark-pigmentotropin in locusts through an albino mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7083–7087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Predel R, Neupert S, Russell WK, Scheibner O, Nachman RJ. Corazonin in insects. Peptides. 2007;28:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Veenstra JA. Isolation and structure of corazonin, a cardioactive peptide from the American cockroach. FEBS Lett. 1989;250:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hillyer JF, Estevez-Lao TY, Funkhouser LJ, Aluoch VA. Anopheles gambiae corazonin: gene structure, expression and effect on mosquito heart physiology. Insect Mol Biol. 2012;21:343–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2012.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bergland AO, Chae HS, Kim YJ, Tatar M. Fine-scale mapping of natural variation in fly fecundity identifies neuronal domain of expression and function of an aquaporin. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Melcher C, Pankratz MJ. Candidate gustatory interneurons modulating feeding behavior in the Drosophila brain. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Staubli F, Jorgensen TJ, Cazzamali G, Williamson M, Lenz C, et al. Molecular identification of the insect adipokinetic hormone receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3446–3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052556499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Veenstra JA, Agricola HJ, Sellami A. Regulatory peptides in fruit fly midgut. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;334:499–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoon JG, Stay B. Immunocytochemical localization of Diploptera punctata allatostatin-like peptide in Drosophila melanogaster . J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:475–488. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hergarden AC, Tayler TD, Anderson DJ. Allatostatin-A neurons inhibit feeding behavior in adult Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3967–3972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200778109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S Fig 1 In male flies there is a small set of Crz-Gal4 expressing neurons in the last abdominal segment that do not produce sNPF. As seen in a - c Crz-Gal4 and sNPF expressing neurons in abdominal ganglia are distinct. Thus the use of the Crz-Gal4 driver to interfere with sNPF expression will only affect the two sets of DLPs in the brain. (TIFF 1,941 kb)

S Fig 2 Morphological details of superposition of DLPs and IPCs in the Drosophila brain. a The DLPs are displayed with Crz-Gal4-driven GFP (green) and IPCs with DILP2 immunolabeling (magenta). The DLPs send axons along the median bundle (MB) and posterior lateral tract (PLT), whereas the axons of the IPCs run in the MB. b Higher magnification of the same neurons showing the tight spatial relations between axon branches of the two neuron types in the median bundle. The region indicated with double arrow (Dendr) is where the IPCs (and DLPs to a lesser extent) have short lateral processes. c1 - c3 Details of the region indicated by double arrow in 1b. Note that both Crz-Gal4 (green) and DILP2 immunolabeled (magenta) axons have short side branches in this region and these may represent functional contacts between the two neuron types. d1 - d2 Another region where DLPs may contact IPCs is in the tritocerebrum (TC) on either side of the esophageal foramen (EF). Clearly the DLPs arborize in additional areas ventral to the TC, including the subesophageal ganglion, suggesting additional outputs and/or inputs. (TIFF 4,089 kb)

S Fig 3 Corazonin/sNPF, DILP2 and sNPFR1-expressing neurons in the third instar larva. a - c Crz-Gal4 (green) and DILP2 immunreactive neurons (aDILP2; magenta) in the larval brain and ring gland (RG). The DLPs and IPCs have processes that superimpose in the corpora cardiaca (CC) of the ring gland and in portions of the brain. For some reason the cell bodies of the mushroom body Kenyon cells (asterisk) display non-specific immunolabeling with anti-DILP2. d Detail of a ring gland where DLP and IPC processes superimpose in the CC, but not corpora allata (CA) of the ring gland (encircled). e - h Using the snpfr-Gal4 driver it appears that the IPCs (labeled with anti-DILP2) do not express the sNPF receptor in the larva. The "white cells" seen in g are above each other in this image stack and do not colocalize the markers. (TIFF 2,398 kb)

S Fig. 4 Hypomorphic sNPF mutant flies live longer when starved. The hypomorphic sNPF c00448 mutant (sNPF mutant) flies display significantly extended survival at starvation compared to two wild type controls (w 1118 and Oregon; OR) (p < 0.0001; n= 76-108 for the three genotypes, 3 replicates). (TIFF 299 kb)

S Fig. 5 Whole body carbohydrate and lipid levels after corazonin and sNPF knockdown in DLPs. a Whole body trehalose levels (mg/g wet weight) in knockdown flies and parental controls is the same in all genoypes in fed flies. b Change in glycogen levels after 24 h starvation is also the same in all genotypes. c The TAG levels (mg/g wet weight) in normally fed flies do not differ significantly between genotypes. (TIFF 927 kb)

S Fig. 6 Whole body carbohydrate and lipid levels after in sNPF mutant flies and after rescue of sNPF in DLPs (in mutant background), compared to parental mutant flies. In a - c flies were fed normal food. a No difference between genotypes for whole body trehalose levels. b With sNPF rescue in DLPs the glycogen levels are higher than in mutants and controls. (**= p<0,01; Two way ANOVA). c Levels of TAG in fed flies are significantly higher after rescue of sNPF in DLPs (**= p<0.01; Two way ANOVA). (TIFF 535 kb)