Abstract

Bacterial Trk and Ktr, fungal Trk and plant HKT form a family of membrane transporters permeable to K+ and/or Na+ and characterized by a common structure probably derived from an ancestral K+ channel subunit. This transporter family, specific of non-animal cells, displays a large diversity in terms of ionic permeability, affinity and energetic coupling (H+–K+ or Na+–K+ symport, K+ or Na+ uniport), which might reflect a high need for adaptation in organisms living in fluctuating or dilute environments. Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters are involved in diverse functions, from K+ or Na+ uptake to membrane potential control, adaptation to osmotic or salt stress, or Na+ recirculation from shoots to roots in plants. Structural analyses of bacterial Ktr point to multimeric structures physically interacting with regulatory subunits. Elucidation of Trk/Ktr/HKT protein structures along with characterization of mutated transporters could highlight functional and evolutionary relationships between ion channels and transporters displaying channel-like features.

Keywords: K+ transporter, Na+ transporter, H+–K+ symport, Na+–K+ symport, Bacteria, Fungi, Plants

Introduction

Potassium is an essential macroelement in every living organism. It is the major inorganic cation in the cell cytoplasm, where it is accumulated against a large transmembrane concentration gradient, by ca. 10-fold in animals and up to 103 to 105-fold in bacteria, fungi, and plants [1–3]. In the latter organisms, which are responsible for the entry of this cation (and of other mineral nutrients) in the trophic chains, the external solution that bathes the cell membrane can display fluctuating and very low K+ concentrations, often in the μM range [4]. Maybe related to this, bacteria, fungi, and plants possess two specific families of K+ transporters, named Trk/Ktr/HKT (acronyms for Transport of K+ in fungi and bacteria, K+ transporter in bacteria and High-affinity K+ transporter in plants) and HAK/Kup/KT (acronyms for High-affinity K+ uptake in fungi and plants, K+ uptake in bacteria and K+ transporter in plants), which are both absent from animal cells. The present review concentrates on the Trk/Ktr/HKT family. After a brief survey of K+ and Na+ requirements and transport in non-animal cells, we describe the predicted structures and evolutionary relationships of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters, then take stock of the available information on these systems in bacteria, fungi, and plants, with a stress on the functional properties of these systems (e.g., in terms of ionic selectivity and energetic coupling) and their roles in the organisms, and finally discusses structural data that have been obtained recently.

K+ and Na+ nutrition in plants, fungi, and bacteria

Roles of K+ and Na+ in the cytosol

K+ is an essential mineral nutrient in every organism, and the most abundant cation in the cytosol. Estimates of the cytosolic K+ concentration range between 50 and 250 mM in plants and fungi [3], between 300 and 500 mM in bacteria, and up to 1 M in bacteria when they are facing hyperosmotic media [5–8]. In contrast, Na+ is toxic at high concentrations in the cytosol. The levels at which toxicity can occur have not been investigated in detail and are likely to depend on cell types [9], but it is generally thought that the cytosolic concentration of Na+ should be controlled below 10–30 mM [10].

Preferential accumulation of K+ in the cytosol has been ascribed to the fact that this cation is “compatible” with water and protein structure even at high concentrations [2] due to its ionic radius, the magnitude of the electric field at its surface, and the structure of its hydration shell [11]. Also, in primitive cells that evolved in seawater, accumulation of K+ and exclusion of the more abundant cation present in the external solution, i.e., Na+, have probably provided the most straightforward way to energize the plasma membrane.

Besides its contribution to electrical neutralization of anionic groups, K+ plays a role in several basic physiological functions, such as control of the plasma membrane potential or osmotic adjustment and turgor regulation [2, 5]. The latter function has been extended, at least in plants, from a purely structural role to a motor function underpinning cell movements, e.g., nastic movements, which include the dramatic leaf movements of the Venus flytrap after a touch stimulus, or guard cell movements, which control stomatal aperture at the leaf surface and gas exchanges (CO2 uptake and water transpirational loss) between the plant and the atmosphere.

Despite its toxicity, Na+ can be substituted for K+ and used as cheap osmoticum in conditions of low K+ availability [3, 12]. In such environmental conditions, selective K+ uptake along with efficient control of Na+ accumulation and compartmentalization at the cell (vacuole) and tissue (e.g., leaf epidermis) levels can result in increased growth in fungi and plants [9, 13, 14].

K+ and Na+ uptake mechanisms in non-animal cells

The general organization of membrane transport in plants, fungi, and bacteria conforms to the chemiosmotic model. Primary electrogenic pumps excreting H+ or Na+ create a transmembrane electrochemical gradient that energizes secondary transport systems, transporters, or channels. When the availability of K+ in the external medium is limiting, the membrane potential can reach values as negative as −200 to −300 mV in fungi and plants [15–18]. These values are much more negative than those classically recorded in animal cells. Such hyperpolarized state stimulates K+ uptake through K+ uniporters, H+–K+ symporters (identified in plants, fungi, and bacteria), Na+–K+ symporters (in vivo evidence so far only in bacteria), or voltage-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (evidence that K+ channels can play such a role presently available only in plants [18–22]). In bacteria, P-type K+ uptake ATPases, named Kdp for K+-dependent growth [6, 23], can also directly contribute to K+ entry.

As indicated above, the Trk/Ktr/HKT and HAK/Kup/KT families have in common to be represented in bacteria, fungi, and plants, and to have no close homologues in animals. The two families differ, however, in their representation: while the Trk/Ktr/HKT family seems to be almost ubiquitous in plants, fungi, and bacteria [24–31], the representation of the HAK/Kup/KT family is more restricted and may be especially represented in organisms adapted to low K+ [32]. The two families also differ in terms of functional diversity. The HAK/Kup/KT gene family encodes K+ transporters [3, 29, 33] whereas the Trk/Ktr/HKT family, initially thought to comprise H+–K+ symporter genes, has now been shown to encode a larger variety of transporters, including Na+–K+ symporters and even transporters permeable to Na+ only [30, 34]. This diversity in functional properties allows the Trk/Ktr/HKT family to contribute to various functions besides K+ transport, such as desalination of the xylem sap and Na+ detoxification in plants [35].

In silico analyses and evolutionary relationships in the Trk/Ktr/HKT family

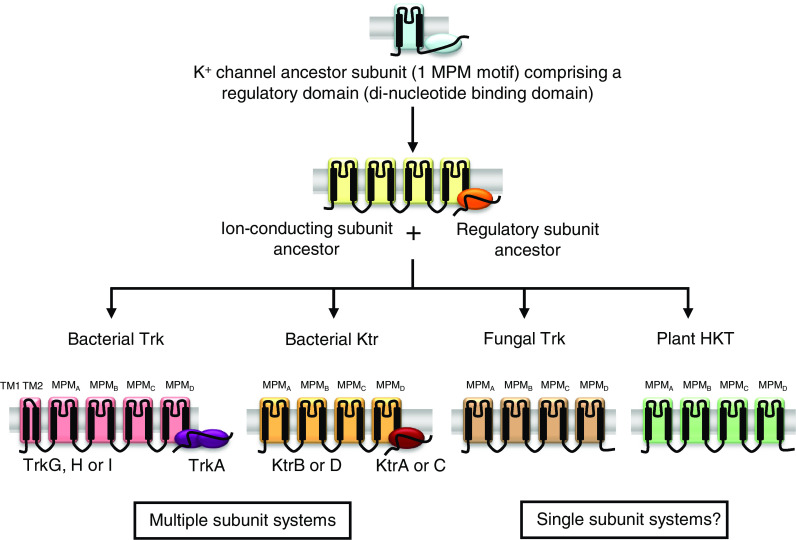

ScTrk1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was the first member of the Trk/Ktr/HKT family identified at the molecular level [25, 36]. Homologues were thereafter cloned in other fungi [29, 37], in bacteria [26, 38, 39], and plants [27, 30, 40]. They have been generically named Trk in fungi [25, 29, 37, 41, 42] and HKT in plants [27, 30, 40, 43]. In bacteria, they have been sorted into two distinct groups, named Trk [6, 24, 26, 39, 44–48] and Ktr [28, 38, 49, 50]. Bacterial Trk and Ktr systems are multimeric systems, each complex associating an ion-conducting transmembrane subunit (like TrkH, G, or I in Trk systems, and KtrB or D in Ktr systems) to at least one peripheral regulatory subunit (TrkA or E, and KtrA, C or E, respectively) (Fig. 1; Table 1 and below).

Fig. 1.

Proposed evolution of the Trk/Ktr/HKT family. Fungal Trk and plant HKT are single subunit systems whereas bacterial Trk and Ktr systems are multimeric complexes, associating an ion-conducting transmembrane subunit (TrkG, H or I, and KtrB or D) to at least one peripheral regulatory subunit (TrkA and KtrA or C). Bacterial Trk and Ktr ion-conducting subunits, fungal Trk, and plant HKT could have originated from a common K+ channel ancestor subunit with one MPM domain by a process of gene duplication and fusion [54]. Bacterial TrkA- and KtrA-type peripheral regulatory subunits could have been derived from the cleavage of the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of this K+ channel ancestor subunit, thus forming a distinct regulatory subunit [54]

Table 1.

Trk/Ktr/HKT systems in bacteria, fungi, and plants: number of genes, functional properties, and roles

| Transporter type | Regulatory subunits for transport | Organism | Number of genes | Ionic permeability | Functional type | Transport affinity | Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||||||

| Trk G, H, I |

TrkA-like TrkE-like |

Bacteria and archae except specific parasitic bacteria | 0–2 | K+ | H+–K+ | Low-aff K+ |

K+ uptake Osmotic adjustment |

[6, 8, 39, 45, 48] |

| Ktr B, D |

KtrA(or C)-like KtrE-like |

Bacteria and archae except specific parasitic bacteria | 0–2 | K+, Na+ | Na+–K+ | Low-aff K+ |

K+ uptake Osmotic adjustment |

[8, 28, 38, 49, 50, 74, 77] |

| Fungi | ||||||||

| Trk | ? | Yeast and filamentous | 1–2 |

K+ K+, Na+ Cl−? |

K+ transport H+–K+ Na+–K+? |

High-aff K+, low-aff K+? Low-aff K+, low-aff Na+ |

K+ uptake Membrane potential control Na+ uptake? |

[3, 25, 81, 99–101] |

| Plants | ||||||||

| HKT1; X | ? | Monocots and dicots | 1–8 | Na+ | Na+ transport | Low-aff Na+, high-aff Na+? |

Salt tolerance Long distance Na+ transport Osmotic adjustment? |

[34, 35, 120, 122–124] |

| HKT2; X | ? | Monocots | 2–4 | K+, Na+ | Na+–K+ | High-aff K+, low/high-aff Na+ | Na+ uptake by roots | [14, 35, 117, 122, 123] |

The hydrophobic transmembrane core of the bacterial Trk and Ktr ion-conducting subunits and of the fungal Trk and plant HKT typically displays four successively arranged MPM domains (abbreviation for transmembrane segment, pore, transmembrane segment). The bacterial Trk ion-conducting subunits display two further transmembrane segments in their N-terminal part, upstream of the first MPM domain. Hydropathy plot analyses of Trk/Ktr/HKT systems had initially supported a structural model comprising 10–12 transmembrane segments [25, 27, 51]. A first breakthrough in understanding the common hydrophobic core structure was achieved when two MPM motifs were identified in bacterial ion-conducting subunits, based on sequence comparisons with extensively characterized animal K+ channels [52]. Further analyses, based on resolution of the crystal structure of the bacterial KcsA K+ channel from S. lividans [53] and on multiple sequence alignments showing conservation of residues, led to the hypothesis of four sequential MPM motifs ([54]; Fig. 1). This proposed four-MPM topology has since received direct support from different kinds of approaches, including biochemical and immunocytochemical analyses [55, 56]. The four MPM domains are believed to be assembled with a fourfold radial symmetry, the four P domains being associated at the center of the hydrophobic structure to form the permeation pathway [54, 57]. A high degree of conservation of residues that are predicted to be located at the outer surface of the protein in eukaryotic Trk/HKT has led to the suggestion that two or four Trk or HKT monomers form dimer or tetramer complexes. In this model, the conserved residues constitute interacting regions between the monomers ([57] and below: “Structure–function of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters”).

Besides providing a common structural model for Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters, integration of information on the bacterial KcsA K+ channel structure into large-scale sequence comparisons of transmembrane domains has led to the hypothesis that the Trk/Ktr/HKT transporter family has evolved from an ancestral K+ channel subunit displaying a single MPM domain (like KcsA) into transporter proteins with four MPM domains by a process of gene duplication and fusion ([54]; Figs. 1, 2). In addition, these analyses pointed out sequence homologies between regulatory dinucleotide-binding domains present in the cytoplasmic C-terminus of many bacterial K+ channels and the TrkA- or KtrA-type peripheral regulatory subunits of bacterial Trk and Ktr systems (Fig. 2; inset and [28, 39, 44, 49, 50, 58]). Thus, it has been suggested that TrkA- and KtrA-type subunits originated from the cleavage of the C-terminal region of a K+ channel ancestor to form distinct regulatory polypeptides ([54]; Fig. 1). KtrA-type regulatory subunits contain a single domain with one dinucleotide-binding site, referred to as KTN (K+ transport, nucleotide binding [59]) or RCK (regulating the conductance of K+ [60, 61]) domain, whereas TrkA-type subunits most often contain two such domains. Sequences sharing homology with bacterial TrkA and KtrA-type regulatory subunits can be identified in fungal or plant genomes (unpublished), but the hypothesis that the encoded proteins contribute to the regulation of fungal Trk or plant HKT transporters has not yet received any experimental support.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the Trk/Ktr/HKT transporter family. Four branches, corresponding to fungal Trk and plant HKT transporters, and to bacterial Trk and Ktr ion-conducting subunits, are distinguished within the phylogenetic tree. The bacterial KcsA K+ channel displays a closer phylogenetic relationship to bacterial Trk and Ktr transporters than to the eukaryotic fungal Trk and plant HKT. Inset Phylogenetic tree of the bacterial TrkA and KtrA-type regulatory subunits. Multiple alignments of Trk/Ktr/HKT full polypeptides were performed using CLUSTALW 1.8. Phylogenetic trees were generated with the distance-based neighbor joining program NEIGHBOR from Phylip (version 3.573c, http://www.phylogeny.fr), and visualized using Phylodendron (http://iubio.bio.indiana.edu/treeapp/treeprint-form.html). One hundred bootstrap replicates were performed for the ion-conducting proteins and 1,000 for the regulatory proteins. Accession numbers of ion-conducting proteins: AaKtrB NP_214039; AtHKT1;1 NP_567354.1 (At4g10310); BsKtrB NP_390988; BsKtrD NP_389233; EcTrkG NP_415881; EcTrkH AAA67646; EhNtpJ BAA04279; HcTrk1 CAL36606.1; HeTrkH AAR91792; HeTrkI AAR91793; LbTrk1 XP_001879952.1; LbTrk2 XP_001880417.1; NcTrk1 XP_957340.1; NcTrk2 XP_959511.1; OsHKT1;1 Q7XPF8.2; OsHKT1;3 Q6H501.1; OsHKT1;4 Q7XPF7.2; OsHKT1;5 Q0JNB6.1; OsHKT2;1 Q0D9S3.1; OsHKT2;2 BAB61791.1; OsHKT2;3 Q8L481.1; OsHKT2;4 Q8L4K5.1; PaTrk1 XP_001905383.1; PaTrk2 XP_001908358.1; PpHKT XP_001763760.1; PtHKT1;1 XP_002325229.1; ScTrk1 NP_012406.1; ScTrk2 NP_012976.1; SIKcsA CAA86025.1; SpTrk1 NP_593934.1; SpTrk2 XP_001713037.1; SspNtpJ NP_441336.1; VaKtrB ZP_01261970.1; VaKtrD ZP_01258579.1; VaTrkG ZP_01262256.1; VaTrkH ZP_01261138.1. Accession numbers of regulatory subunits: BsKtrA NP_390541.1; BsKtrC NP_389334; EcTrkA NP_417748.1; HeTrkA AAR91791; SspKtrA NP_442775; VaKtrA ZP_01261971.1; VaTrkA ZP_01261140.1. Aa, Aquifex aeolicus VF5; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Bs, Bacillus subtilis; Ec, Escherichia coli; Eh, Enterococcus hirae; Hc, Hebeloma cylindrosporum; He, Halomonas elongata; Lb, Laccaria bicolor; Nc, Neurospora crassa; Os, Oryza sativa; Pa, Podospora anserina; Pp, Physcomitrella patens; Pt, Populus trichocarpa; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Sl, Streptomyces lividans; Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Ssp, Synechocystis sp. PCC6803; Va, Vibrio alginolyticus

Analyses of phylogenetic relationships within the Trk/Ktr/HKT transporter family and within TrkA/KtrA-type regulatory subunits are provided in Fig. 2. Four branches are clearly distinguishable in the tree obtained for the ion-conducting proteins (Fig. 2), corresponding to the plant HKT, fungal Trk and to each of the prokaryotic Trk and Ktr sub-families. The bacterial KcsA K+ channel is phylogenetically more closely related to prokaryotic Trk and Ktr transporters than to the eukaryotic Trk from fungi or to HKT from plants [54].

Trk and Ktr transporters in prokaryotes

Despite the large diversity of life styles in the prokaryote kingdom, from free-living habitat to commensalism, parasitism, or symbiosis, the universality of the use of K+ as endocellular cation and the rather limited number of K+ transport systems are striking [62]. Membrane proteins identified in bacteria as playing major roles in K+ transport are Trk, Ktr, and Kup transporters, Kdp pumps (P-type ATPases mediating low-rate high-affinity K+ uptake), K+ channels and K+ efflux systems including KefB and KefC [8]. The representation of these different types of transport systems varies among bacterial species. As a general trend, most intracellular parasites with greatly reduced genomes have no K+ channels as well as no specialized K+ uptake mechanisms, whereas extracellular pathogens that have no K+ channel genes possess Trk, Ktr, Kup, and Kdp systems (e.g., Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Haemophilus influenza, etc.) [62]. Free-living archaea and bacteria have K+ transporters, usually Trk (e.g., Escherichia coli) or Ktr (e.g., Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Bacillus subtilis) or both (e.g., Vibrio alginolyticus; see below), and sometimes Kup or Kdp homologues in addition or instead of Trk or Ktr systems (e.g., Corynebacterium glutamicum [63]). This variability probably reflects adaptation to different environmental niches.

The structural differentiation between the two bacterial subfamilies Trk and Ktr might correspond to an essential functional difference with respect to the ion species co-transported with K+, i.e., either H+ or Na+ (Table 1 and below). Trk transporters are thought to use H+ [64] and Ktr transporters Na+ [65]. The evolutionary selection for and presence of Ktr or Trk homologues with their distinct transport mechanisms regarding the co-transported counter ion may reflect a special response to salt stress. For bacteria living in saline environments, e.g., Halomonas elongata, or the extreme halophiles Halobacterium halobium and Halofeax volcanii, it may be advantageous to use Trk uptake systems [8], thus avoiding additional Na+ loading by the Na+-coupled co-transport of Ktr systems.

The E. coli model and Trk systems

Escherichia coli displays three types of K+ uptake systems, Trk, Kdp, and Kup [62], but no Ktr transport system (Table 2). The internal concentration of K+ in E. coli cells has been reported to be close to 200 mM in minimal media containing submicromolar K+ concentrations [1, 66] and to linearly increase with rising external osmolarity.

Table 2.

Nature and nomenclature of Trk/Ktr/HKT systems in model organisms

| Organism | Transporter | References |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli |

2 Trk conducting subunits: TrkG and TrkH 2 Trk regulatory subunits: TrkA and TrkE |

[6, 24, 26, 44, 45, 47, 68] |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 |

1 Ktr conducting subunit: KtrB 2 Ktr regulatory subunits: KtrA and KtrE |

[50, 72] |

| B. subtilis |

2 Ktr conducting subunits: KtrB and KtrD 2 Ktr regulatory subunits: KtrA and KtrC |

[49, 61, 73] |

| V. alginolyticus |

1 Ktr conducting subunit: KtrB 1 Ktr regulatory subunit: KtrA 1 Trk conducting subunit: TrkH 1 Trk regulatory subunit: TrkA |

[28, 39, 74] |

| S. cerevisiae | 2 Trk: ScTrk1 and ScTrk2 | [25, 41, 85] |

| S. pombe | 2 Trk: SpTrk1 and SpTrk2 | [37, 87, 88] |

| N. crassa | 2 Trk: NcTrk1 and NcTrk2 | [29, 93] |

| A. thaliana | 1 HKT: AtHKT1;1 | [30, 127] |

| O. sativa | 9 HKT: OsHKT1;1 to 1;5 and OsHKT2;1 to 2;4 | [116, 122] |

| V. vinifera | ≥4 HKT (subfamily 1) | [119] |

The K+-translocating TrkH subunit from E. coli has been extensively studied in pioneering works [24, 45, 47, 67, 68] and used for in silico elaboration of structural models [57]. TrkH is thought to display four sequential MPM domains and, like other bacterial Trk, two additional transmembrane segments (TM1 and TM2) located upstream from the first MPM motif (Fig. 1).

Escherichia coli strain K12 harbors a second K+-uptake system from the Trk subfamily, TrkG (Tables 1, 2), almost identical to TrkH and encoded by a foreign gene acquired through phage insertion. The two integral membrane proteins TrkH and TrkG determine the specificity and kinetics of cation transport [26, 47]. However, TrkG is not found in every E. coli strain, whereas TrkH is systematically present in E. coli and other enteric bacteria [48].

The translocating subunits TrkH and TrkG from E. coli have been shown to form multimeric functional transporters in association with a cytoplasmic regulating subunit named TrkA (Table 2). Individual disruption of either TrkH or TrkG does not preclude formation of functional complexes. Each protein alone is sufficient for high-level Trk activity, but the presence of the TrkA subunit is absolutely required as demonstrated by mutant studies [6, 24, 44, 45, 47]. The E. coli TrkA harbors two nucleotide-binding sites, (each one corresponding to a KTN/RCK domain ([39, 44, 58] and above). In general, TrkA subunits contain two nucleotide-binding sites situated in two similar subdomains [54], suggesting a gene duplication of a precursor (Fig. 1 and above). However, it should be noted that some TrkA from archeal species display a single nucleotide-binding domain. The E. coli TrkA subunit has been shown to bind NAD+ and/or NADH in vitro [58], possibly allowing K+ transporters to be responsive to the redox state of the cell. At present, it is not known whether dinucleotides influence transport activities in vivo ([59, 60] and below “Structure–function of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters”).

Another regulating partner belonging to a different class of proteins than TrkA has been identified in E. coli and named TrkE (or SapD) (Table 2). It maps with the sapABCDF operon coding for an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter of unknown function from the subgroup of peptide-uptake systems. TrkE confers ATP-responsiveness to the K+-uptake systems TrkH and TrkG [68], resulting in ATP-dependent stimulation of the K+ transport activity. Evidence has been obtained that this effect involves ATP binding rather than hydrolysis. It should be noted, however, that sensitivity of the K+ transport to ATP can occur in absence of TrkE. This suggests the involvement of at least one other protein, besides TrkE, in the ATP-dependent regulation [68].

The Trk system of E. coli has been described as mediating constitutive, low-affinity high-rate K+ transport energized by the proton-motive force (Table 1 and below “Selectivity and transport mechanisms in bacterial Trk and Ktr transporters”) as well as by ATP [69]. Currently, symport of 1 H+ with 1 K+ is assumed and ATP is thought to have a regulatory role only [8, 68, 70]. Affinity for K+ (KM) has been estimated to be close to 1 mM [6, 8].

As mentioned above, halophilic bacteria rely on Trk systems for K+ uptake, maybe because these systems are energized by co-transport with H+ rather than with Na+. Trk-mediated K+ uptake in the halophilic bacterium H. elongata involves three proteins, TrkH and TrkI which are both ion-conducting transmembrane subunits, and TrkA which is similar to E. coli TrkA and interacts with both transport subunits [48]. Thus, the Trk system of the halophilic species does not seem to be very different from that of E. coli. Mutant studies using a strain deleted in TrkH have shown that TrkI is the main K+ transport system in H. elongata [48].

Ktr systems in Synechocystis and B. subtilis

The cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 has a single Ktr ion-conducting subunit, KtrB, previously identified as NtpJ (slr1509) ([38, 71]; Table 2). The Ktr transport system is crucial for K+ uptake in Synechocystis, since the mutant (ΔntpJ) showed slow growth and K+ uptake, and also increased salt sensitivity [72]. Evidence is available that this ion-conducting subunit is part of a more complex Ktr system comprising, in addition to KtrB, two peripheral regulatory subunits KtrA (sll0493) and KtrE (slr1508) ([50]; Table 2). KtrA is distantly related to TrkA, the regulatory subunit of the Trk system (Fig. 2, inset). Its size is about half that of TrkA, with only a single KTN/RCK domain instead of two as in TrkA (Fig. 1). KtrE displays similarities to glycosyl transferases. Its contribution to Ktr transport activity has been demonstrated by expression experiments in E. coli [50]. The Synechocystis KtrABE system displays Na+-dependent K+ uptake [50], suggesting Na+–K+ symport activity (as in V. alginolyticus, Table 1 and below). It has been shown that the Ktr system plays a crucial role in the early phase of cell turgor regulation for adaptation to hyperosmotic shock in Synechocystis ([50]; Table 1).

In B. subtilis, the Ktr family comprises two different complete transport systems, KtrAB and KtrCD (Table 2). KtrB and KtrD (yubG & ykrM) are the ion-conducting subunits of these systems, and KtrA and KtrC (yuaA & ykqB) the peripheral regulatory subunits [49]. These two homologous transport systems differ with respect to their affinity for K+ (KM of 1 and 10 mM for KtrAB and KtrCD, respectively). Selectivity and affinity for Na+ has not been reported. The two K+ uptake systems KtrAB and KtrCD are necessary for adaptation to hyperosmolarity in B. subtilis [49]. Mutant strains defective in these transport systems exhibit growth defects when exposed to osmotic shock or to high osmolarity, demonstrating that K+ uptake via KtrAB and KtrCD is crucial in cellular adaptation to both suddenly imposed and prolonged osmotic stress (Table 1). Biochemical and structural analyses have provided evidence that the B. subtilis KtrA subunit can bind both ATP and NAD+/NADH via its KTN domain, and that KtrB forms homomeric dimers ([59, 61, 73] and below “Structure–function relationship of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters”).

Coexistence of Trk and Ktr systems in bacterial species

The marine bacterium V. alginolyticus is a well-described example of an organism harboring both Trk and Ktr transport systems (Table 2). The gene cluster TrkAH is coding for the Trk complex, which comprises the ion-conducting subunit TrkH and the regulating subunit TrkA [39]. The Ktr system comprises the ion-transporting subunit KtrB and its regulatory subunit KtrA [39]. Na+-dependent K+ uptake has been demonstrated for the KtrAB system [65], suggesting Na+–K+ symport activity (Table 1 and below). The affinity for K+ of this transport system has been found to lie in the submillimolar range [74].

Enterococcus hirae has been shown to have a Trk system (previously described as KtrI), assumed to operate as a H+–K+ co-transporter and to be regulated by ATP [75, 76], and a Ktr system (previously described as KtrII), which is independent of the proton-motive force [77]. Interestingly, the gene (NtpJ) encoding the ion-conducting subunit (KtrB) of the latter system was found to be present at the tail end of the vacuolar-type Na+ ATPase operon (ntp) of E. hirae. The ntp operon is known to be upregulated at the transcriptional level in response to increased Na+ concentrations [78]. Analyses of ion uptake in a mutant strain (ntpJ) have revealed that KtrB plays a major role in K+ transport [77, 78]. However, the fact that the sequence encoding KtrB is present in the vacuolar-type Na+ ATPase operon may indicate that KtrB-mediated K+ uptake is in some manner dependent on Na+, or on Na+ ATPase activity [38, 78].

Selectivity and transport mechanisms in bacterial Trk and Ktr transporters

As indicated above, the available information suggests that Trk and Ktr transporters differ in an essential manner with respect to the co-transported ionic species, i.e., H+ in Trk and Na+ in Ktr systems ([64, 65]; Table 1). However, information of crucial importance for analyzing energetic coupling and co-transport mechanisms is still missing. Most functional data have been gained by growth tests and K+ transport measurements in mutant strains, and/or by expression of transporters from E. coli or other organisms [79] in E. coli mutant strains defective for K+ uptake (due to deletion of endogenous Trk, Kup, and Kdp transport activities). In such experiments, K+-dependent Na+ uptake was not checked because of intrinsic Na+ uptake activity of the mutant strains used [74]. Furthermore, it is likely that the transmembrane electrical gradient, which was not measured in this type of experiments, is strongly altered by deletion of major K+ transport activities and thus different in wild-type, mutant, and complemented strains.

Data supporting the hypothesis that Trk systems can mediate H+–K+ symport activity have been mainly obtained in E. coli [8, 69, 70]. The major argument is that K+ transport is sensitive to pH and to effectors of the proton-motive force. Also, K+ uptake by the Trk system of E. coli (as well as by that of V. alginolyticus) has been shown to be Na+-independent [65]. In E. coli TrkH, the second MPM motif might be involved in H+ permeation, possibly by interaction with TM1 [57].

The hypothesis that Ktr systems mediate Na+–K+ symport activity is essentially supported by the fact that the transport activity is dependent on the presence of Na+, as mentioned above for the Ktr systems from Synechocystis [50] and V. alginolyticus [65]. Using the Michaelis–Menten formalism to describe the stimulation of K+ uptake by Na+ in the V. alginolyticus KtrAB system heterologously expressed in E. coli mutants has led to an affinity constant KM close to 40 μM [65]. Expression in E. coli of V. alginolyticus KtrB without KtrA revealed that KtrB subunit is able to mediate both Na+-independent K+ uptake as well as K+-independent Na+ uptake [74], suggesting that one function of KtrA is to confer coupling of K+ and Na+ fluxes to the Ktr complex. Another function of KtrA within the functional KtrAB complex may be to control the transport rate [74]. Regarding the ion-conducting subunit of the complex, site-directed mutagenesis experiments have demonstrated that the glycines in the selectivity filter of each of the four KtrB pore regions control the affinity of the transporter for both K+ and Na+ ([65, 74] and below “Structure–function relationship of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters”).

Since the current information on Trk/Ktr/HKT transporter structure essentially comes from bacterial systems (see below), it is a pity that these systems remain poorly characterized at the functional level. Clearly, the development of novel strategies allowing us to obtain more detailed information on electrophysiological properties of bacterial Trk and Ktr is eagerly awaited for.

Trk transporters in yeast and filamentous fungi

Yeast and filamentous fungi can colonize media strongly differing in their K+ availability, from the μM range, in poor soils, to the tens of mM range in litter, fruits or musts [3, 29, 42]. Based on the present knowledge, all organisms from the fungal kingdom should possess one or two K+ transporters belonging to the Trk family (Table 1), and some of them also transporters from the HAK family [3]. The presence of high-affinity HAK transporters induced by K+ starvation may present an ecological advantage for yeast/fungi growing in low-K+ environments [3, 29, 42]. It has also been suggested that the relative contribution of Trk and HAK transporters to K+ uptake depends on the pH of the external medium, HAK systems being more active at low pH and Trk transporters at neutral or slightly alkaline pH [3]. It is worth noting, however, that S. cerevisiae can grow on acidic media with low K+ concentrations (in the μM range) although K+ uptake is essentially mediated by Trk systems in this organism, which does not possess HAK systems [3, 80].

Evidence has been obtained in fungi that, related to their role in K+ uptake, Trk transporters are involved in the control of the cell membrane potential. Disruption of Trk genes results in strong membrane hyperpolarization, which affects the activity of other secondary transport systems ([3, 81]; Table 1). Through these basic functions, Trk transporter activity may be involved in highly integrated and essential processes. For instance, in the filamentous fungus model Podospora anserina, disruption of either of the two Trk genes results in an intriguing growth alteration phenotype, characterized by an incomplete penetrance and a variable expressivity [82].

Trk transporters in S. cerevisiae

Two Trk genes, named ScTrk1 and ScTrk2, are present in S. cerevisiae (Table 2). ScTrk1 was the first identified member from the Trk/Ktr/HKT family. It was cloned by functional complementation of a yeast mutant strain defective for K+ uptake [36] using a yeast genomic DNA library [25]. ScTrk1 and ScTrk2 share 55% identity, mostly in the hydrophobic transmembrane segments.

S. cerevisiae trk1 knock-out mutant strains display a severe decrease in K+ influx, retaining only the low-affinity K+ uptake activity. They are consequently unable to grow on media with a concentration of K+ lower than 1 mM [83]. Yeast trk2 mutants are phenotypically undistinguishable from wild-type cells, but disruption of both ScTrk1 and ScTrk2 results in a very severe phenotype: the double mutant cells require K+ concentrations higher than 10 mM to display normal growth, when compared to wild-type cells [41, 81]. Taken as a whole, these phenotypic features supported the hypothesis that ScTrk1 and ScTrk2 strongly differ in their affinity for K+ (Table 1), the former system being a high-affinity K+ transporter [25] and the latter a low-affinity one [84]. Direct measurements of K+ (Rb+) transport activity have provided further support to this hypothesis with regard to ScTrk1, which clearly appears in every report as a high-affinity K+ uptake system (monophasic Michaelis–Menten kinetics with a KM in the μM range) and the only (or at least the major) contributor to K+ uptake in common environmental conditions. The affinity for K+ and the physiological roles of ScTrk2 have remained more controversial [85]. Recently, it has been proposed that ScTrk2 could work as a high-affinity K+ transporter under very specific environmental conditions. Expression of this system would be repressed under standard conditions, probably by the transcriptional repressor Sin3, since Δtrk1 Δsin3 knock-out mutant cells (disrupted in both Trk1 and Sin3) can grow on low K+ media and at low pH, whereas Δtrk1 Δtrk2 Δsin3 mutant cells are unable to take up K+ and to grow in such conditions [86].

Trk transporters in other yeast species

Like S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe has two Trk systems for K+ uptake, SpTrk1 and SpTrk2 ([37, 87, 88]; Table 2). Interestingly, impaired K+ uptake, resulting in decreased growth rate on low K+ media, appears in S. pombe only upon disruption of both Trk genes, contrary to observations in S. cerevisiae. This suggests that in S. pombe, the two Trk transporters are partly redundant systems in standard conditions [89].

Trk transporters have also been identified in the soil yeast Schwanniomyces occidentalis and in the salt-tolerant marine yeast Debaromyces hansenii, which is closely related to the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Both S. occidentalis and D. hansenii possess a HAK-type transporter as well [42, 90]. For S. occidentalis, it has been proposed that SoTrk1 plays an important role in the control of the membrane potential and mediates K+ transport from high K+ concentrations, whereas SoHAK ensures K+ uptake from low K+ and acidic media [42]. For D. hansenii, which lives in marine habitats and thus in presence of K+ concentrations in the mM range, both DhTrk1 and DhHAK have been suggested to behave as low-affinity transporters [90].

Trk from filamentous fungi

Neurospora crassa has been used since the 1980s as a model to study the energization and mechanisms of K+ uptake in filamentous fungi [91, 92]. Patch-clamp analyses have brought direct evidence that H+–K+ symport systems are present at the plasma membrane and are responsible for K+ uptake from low K+ media [15]. The N. crassa genome comprises one HAK and two Trk genes, named NcHAK, NcTrk1 [29] and NcTrk2 ([93]; Table 2). Heterologous expression of NcHAK and NcTrk1 in S. cerevisiae ∆trk1 ∆trk2 double mutant cells has provided support to the hypothesis that NcHAK displays high-affinity H+–K+ symport activity allowing K+ uptake from low concentrations, whereas NcTrk1 contributes to K+ uptake from higher concentrations [29]. Interestingly, K+ (Rb+) uptake in N. crassa cells is competitively inhibited by Na+ in a large K+ concentration range, suggesting that both HAK and Trk transporters are also permeable to Na+ in this organism [29].

Trk genes are present in genomes of filamentous fungi sequenced recently [93–97]. A Trk transporter, HcTrk1, has been identified and characterized in the ectomycorrhizal fungus model Hebeloma cylindrosporum [98, 99]. Ectomycorrhizal symbiosis between fungi and woody plants strongly improves plant mineral nutrition, the fungal partner efficiently taking up mineral nutrients, including K+, from the soil and transferring them to the host plant. HcTrk1 is at present the sole member of the fungal Trk family that has been electrophysiologically characterized in detail (in Xenopus oocytes). The results indicated that this system is permeable to both K+ and Na+. Interactions between these two ion species during permeation have suggested Na+–K+ symport activity [99]. Laccaria bicolor, the first ectomycorrhizal fungus the genome of which has been made publicly available [96], harbors one HAK and two Trk genes, like N. crassa.

Selectivity and mechanisms of transport in fungal Trk

S. cerevisiae mutant strains defective in K+ uptake due to disruption of Trk transporter activity have been extensively used as heterologous systems to characterize the functional properties of Trk transporters from other organisms. Such studies have most often been carried out by analyzing K+ uptake kinetics, using Rb+ as a tracer of K+. It should be considered that this type of approach might provide a distorted view due to the fact that Rb+ is not a good tracer of K+, at least in some Trk transporters [3], and to the hyperpolarized state of the yeast mutant cells [81].

It is very likely that all fungal Trk transporters are permeable to K+ since they all complement S. cerevisiae mutant strains defective for K+ [29, 37, 42, 88, 90, 99]. Indirect evidence for permeability to Na+, besides K+, has been obtained in N. crassa or S. cerevisiae ([29, 100]; Table 1). Direct evidence for permeability to Na+ has been obtained in HcTrk1 from H. cylindrosporum. Surprisingly, this system was found to be even more permeable to Na+ than to K+ when expressed in Xenopus oocytes ([99]; Table 1).

Surprisingly, pH-sensitive macroscopic anionic (Cl−) conductances recorded in S. cerevisiae spheroplasts by patch-clamp experiments were not observed in ∆trk1 ∆trk2 mutant strains and thus required functional expression of ScTrk1 and/or ScTrk2. Therefore, in addition to their K+ transport activity, the Trk transport systems of this organism could also mediate large outward chloride fluxes ([101, 102]; Table 1). A similar Trk-mediated anionic conductance, but with distinctive features with respect to, e.g., sensitivity to pH and to inhibitors, has been identified in C. albicans [103]. It is thought that the permeation pathway responsible for this Cl− efflux activity is different from that permeable to K+, and is formed by symmetric arrangement of four Trk monomers within a multimeric complex. However, the physiological significance of this activity is poorly understood. It is not even clear whether this anionic channel-like activity is accessory or adventitious [101, 102].

Concerning the sensitivity to pH, Trk-mediated K+ transport activity in S. cerevisiae cells is little affected by changes in external pH in a large range of physiological values, from 4 to 8 [80]. HcTrk1 also does not display any sensitivity to pH between pH 5.5 and 8 when expressed in oocytes [99]. In contrast, sensitivity to pH has been shown for SpTrk1 from S. pombe. Indeed, in patch-clamp experiments on S. cerevisiae spheroplasts expressing SpTrk1, the recorded SpTrk1 currents were strongly stimulated by acidification of the medium in the physiological range [37]. This stimulating effect is classically considered as an indication of H+–K+ symport activity. It could, however, merely correspond to pH-dependent activation of the transporter, as reported for example in some inward K+ channels [104–106]. So far, none of the fungal Trk family members has been definitively demonstrated as endowed with the capacity to mediate active K+ uptake, against the transmembrane K+ electrochemical gradient. Active K+ uptake reported in fungal organisms, as N. crassa, has most often been ascribed to HAK transporters. However, some yeasts, like S. cerevisiae, can grow on low-K+ media at low pH values, the latter condition resulting in membrane depolarization, although they strictly rely on Trk transporter activity for K+ uptake. This fact strongly suggests that the Trk transporters of these organisms are able to mediate active K+ transport. Further support for this hypothesis is provided by the report that the K+ transport activities mediated by either ScTrk1 or a K+ channel (AKT1 from Arabidopsis thaliana) in S. cerevisiae cells displays distinctive sensitivity to the protonophore uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) [100]. Within the framework of the hypothesis that Trk systems can mediate active K+ transport, permeability to Na+ [99] and/or competitive inhibition of Trk-mediated K+ transport by Na+ [29, 100] may be indicative of a Na+–K+ co-transport mechanism. However, this hypothesis is weakened by experiments showing that Trk transport activity can be detected in S. cerevisiae in “absence” of added Na+ (nominal contaminating concentrations) [3]. Furthermore, in experiments carried out in media containing low Na+ concentrations (<4 μM), ScTrk1-mediated K+ uptake was found to neither consume external Na+ ions nor to depend on this cation [100]. So far, there is also little support for the hypothesis that the co-transported ion in this system is H+, in particular since the independence of Trk-mediated K+ transport activity from the external pH in the 4–8 range would be surprising for a H+–K+ symport [80, 100]. In this context, it has been suggested that active K+ transport in ScTrk1 involves direct coupling to a source of chemical energy rather than indirect energization by the electrochemical gradient of H+ or Na+. However, in the absence of any hint about the mechanism of direct chemical coupling, the mechanism of the active K+ uptake mediated by ScTrk1 is obscure.

In conclusion, the present knowledge on the mechanisms of (co)transport in fungal Trk systems, as in bacterial Trk and Ktr, is still very unsatisfactory. Patch-clamp analyses of fungal systems in yeast spheroplasts and two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings after heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes have provided original and exciting information, without any counterpart in bacterial systems, but crucial questions (regarding for instance the ability to mediate active transport and the energetic coupling mechanisms) deserve to be further investigated.

Plant HKT transporters

Soils in which plants develop, like the different media colonized by fungi and bacteria, can strongly vary in their K+ concentration, which can range from μM to mM [3, 107]. Compared to fungi and bacteria, plants possess a larger number of K+ transport systems, probably due to their higher complexity. For instance, at least 34 genes in Arabidopsis and 45 genes in rice [108, 109] are potentially encoding K+ transport systems involved in K+ uptake from the soil solution and subsequent transport of this cation in the organism, e.g., vacuolar compartmentalization or long distance transport in the plant vascular tissues. The HKT transporter family is one of five families of plant-transport systems shown to be or expected to be involved in K+ transport. The other four families are the HAK/Kup/KT transporter family, KEA H+/K+ antiporters, and two families of K+ channels, the Shaker family and the TPK family [110, 111].

Major roles in K+ transport across the plant plasma membrane have been ascribed so far to Shaker channels and HAK/Kup/KT transporters. The Shaker gene family, which comprises nine members in the dicotyledonous model plant Arabidopsis thaliana and ten members in the monocotyledonous model rice, encodes highly K+-selective inward or outward channels, which have been shown to play major roles in K+ uptake or release in various plant cells/tissues [111, 112]. Surprisingly, besides their contribution to low-affinity K+ transport, some inward channels are also involved in K+ uptake at low (submillimolar) concentrations [18, 21]. HAK/Kup/KT transporters form a large family, comprising 13 members in Arabidopsis and 26 members in rice. They are functionally more diverse than their fungal and bacterial homologues, including both high-affinity transporters likely working as H+–K+ symporters and low-affinity K+ transporters [32, 113]. Their roles in plants are not yet fully understood. Indications have however been obtained that high-affinity HAK/Kup/KT members are involved in root K+ uptake in conditions of low K+ availability [31, 114, 115].

Concerning the contribution of plant HKT transporters to K+ transport across the plasma membrane, it should be noted that the acronym HKT, initially given to these systems and standing for “high-affinity K+ transport”, may turn out to be inappropriate since there is no experimental support so far to the hypothesis that these transporters play a significant role in K+ transport in plants. Furthermore, unexpectedly, a large subset of plant HKT transporters has appeared to be permeable to Na+ only (see below). This has focused the research on the physiological roles of plant HKT towards adaptation to saline environments rather than K+ nutrition and, actually, most of the present knowledge on the roles of these systems concerns salt tolerance. However, data obtained in yeast and Xenopus oocytes show that some plant HKT systems are permeable to both K+ and Na+. Thus, the hypothesis that the plant HKT family also plays roles in K+ uptake in plants by mediating Na+-K+ co-transport still deserves to be considered.

Permeability to K+ and/or Na+ in plant HKT

The first cloned HKT transporter, TaHKT2;1 (formerly named TaHKT1 [116]), has been identified in wheat by functional complementation of a S. cerevisiae mutant strain defective for K+ uptake [27]. Functional characterization of TaHKT2;1 in yeast and Xenopus oocytes has revealed that TaHKT2;1 works as a Na+–K+ symport at least in these expression systems [117]. Surprisingly, other members of the plant HKT family, like AtHKT1;1, the unique HKT member in A. thaliana (Table 2), were subsequently found to be permeable to Na+ only [30]. At present, the available data suggest that all plant HKT transporters are permeable to Na+ and some of them are permeable to K+ also [35].

Site-directed mutagenesis experiments based on pore sequence comparison between bacterial and fungal Ktr/Trk members and plant HKT permeable to Na+ only, e.g., AtHKT1;1, or to both K+ and Na+, e.g., TaHKT2;1, have been aimed at identifying major determinants of transporter ionic selectivity (see “Mutagenesis analyses and molecular basis of ion selectivity”). A hallmark of plant transporters permeable to K+ is thought to be a glycine residue localized in the first of the four pore domains. The position corresponding to this residue is occupied by a glycine in bacterial and fungal Trk/Ktr as well [118], but by a serine in AtHKT1;1 and other plant HKT transporters shown to be permeable to Na+ only [118].

Differences in HKT transporter number and functions between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species

The HKT transporter family seems to be ubiquitous in plants, but the number of genes by which it is represented is highly variable between species [116].

Dicotyledonous species generally are believed to possess a low number of HKT genes. For instance, Arabidopsis and poplar possess only one HKT gene (Fig. 2). However, some dicotyledonous species have larger numbers of HKT genes. For example, at least four HKT genes can be found in the recently released grapevine genome sequence [119] (Tables 1, 2). Information on functional properties of dicotyledonous HKT transporters is still relatively scarce, except for the Arabidopsis member, AtHKT1;1, which has been extensively characterized (see below). Dicotyledonous HKT are generally assumed to be Na+-selective, based on functional data obtained for AtHKT1;1 and analyses of transporter pore sequences (see above) [35, 116]. It is worth noting, however, that HKT transporters from two dicotyledonous species, ice plant and eucalyptus, have been reported to display indications of permeability to K+ when expressed in E. coli and/or Xenopus oocytes [43, 120, 121]. Although these results have to be confirmed, they clearly point out the necessity for further characterization of the dicotyledonous HKT family at the functional level, especially regarding the ionic selectivity of these systems.

Monocotyledonous species are thought to possess a larger number of HKT genes than dicotyledonous species. For instance, rice possesses 8 or 9 HKT genes (depending on cultivars) (Table 2), six of which encode strongly divergent transporters (40–50% amino acid identity [122]). Eight homologues of rice HKT genes have been identified in barley, 5–11 in the different wheat genomes [123]. Based on phylogenetic relationships and functional properties, monocotyledonous HKT transporters can be sorted into two major subfamilies ([116]; Table 2), subfamily 1, which regroups members close to dicotyledonous HKT, and subfamily 2 which comprises members more divergent from dicotyledonous HKT (Fig. 2), in particular in their pore domains.

The number of members in the monocotyledonous subfamily 1 is variable according to the species, e.g., five in rice and barley, and 2–8 in the different wheat genomes ([122, 123]; Table 1). The HKT transporters from monocotyledonous subfamily 1 characterized so far are all highly selective for Na+ [119, 122, 124].

Members from subfamily 2 that have been characterized at the functional level, OsHKT2;1 and OsHKT2;2 from rice, TaHKT2;1 from wheat and HvHKT2;1 from barley, have been shown to be permeable to both Na+ and K+ at least at submillimolar Na+ and K+ concentrations when expressed in yeast and/or Xenopus oocytes [40, 117, 119, 125, 126]. In these conditions, a Na+-K+ symport behavior could be detected in these transporters when searched for [117, 119, 126]. Detailed analyses have revealed complex permeation properties, depending on external concentrations of Na+ and K+ (see below “Mechanisms of transport through plant HKT transporters”): the HKT2;1 and HKT2;2 transporters characterized so far become highly selective for Na+ in the presence of high external Na+ and are more or less inhibited by high external K+ concentrations [17, 119, 122].

Thus, two types of HKT transporters have been identified so far in higher plants: those described as Na+ transporters, present in all plant species, and those able to co-transport Na+ and K+, which have been proposed to be present only in monocotyledonous species. The physiological significance of this difference between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species is unclear.

AtHKT1;1 from the model plant A. thaliana

AtHKT1;1 works as a Na+-selective K+-insensitive transporter when expressed in Xenopus oocytes [30, 34]. In yeast, in accordance with the oocyte data, AtHKT1;1 was unable to restore growth of a K+-uptake-deficient mutant strain (∆trk1 ∆trk2) in the presence of 1 mM external K+ [127] and induced growth inhibition in a Na+ hypersensitive mutant at high external Na+ [30]. When expressed in E. coli, AtHKT1;1 was found to complement the growth defect of a K+-uptake-deficient mutant (lacking expression of Trk, Kup and Kdp transporters) and to enhance cell K+ uptake at high external K+ concentrations (10–20 mM) [30]. This may indicate a slight K+ permeability through AtHKT1;1 but also result from an indirect effect of AtHKT1;1 expression on membrane transport activity.

At the whole plant level, expression of AtHKT1;1 was found in vascular tissues of all Arabidopsis organs, more precisely in xylem parenchyma and/or phloem cells, depending on the studies [34, 128]. Mutant plants in which AtHKT1;1 activity was impaired (mutations resulting in loss of function or in decreased activity) overaccumulated Na+ in shoots when they were subjected to salt stress, and displayed growth hypersensitivity to salt [34, 127]. Further analyses of these lines revealed a reduced concentration of Na+ in the phloem sap compared to that in wild-type plants. In knock-out lines, this phenotype was accompanied by a higher concentration of Na+ in the xylem sap. Thus, it has been proposed that AtHKT1;1 is involved in preventing shoot Na+ overaccumulation via two mechanisms (Fig. 3): (i) desalination in roots of the ascending sap by mediating Na+ uptake in xylem parenchyma cells [128] and (ii) recirculation of shoot Na+ towards the roots by mediating Na+ loading into the phloem sap [34]. To date, xylem sap desalination in roots is thought to be the most important mechanism through which AtHKT1;1 controls shoot Na+ content [129, 130].

Fig. 3.

Functions of HKT transporters in planta. The schematic diagram presents three HKT transporters for which a role in planta has been obtained through complementary experimental approaches including localization at the tissue/cell level, functional characterization in heterologous systems and analysis of mutant plant phenotype. The rice OsHKT2;1 transporter plays a role in root Na+ uptake [14, 40]. AtHKT1;1, the only HKT member in Arabidopsis thaliana, and OsHKT1;5 from rice are involved in protecting plant leaves from Na+ over-accumulation during salinity stress [30, 34, 124, 128]. Ep epidermis, Cp cortex parenchyma, En endodermis, Pe pericycle, Xp xylem parenchyma cell, Bs bundle sheath cell, Mc mesophyll cell, Cc companion cell

Roles of other HKT transporters permeable to Na+ only

Information on the physiological role played by members from the monocotyledonous HKT subfamily 1 was revealed by the discovery that QTL controlling leaf Na+ accumulation in rice and wheat correspond to transporters from this subfamily [124, 131, 132]. For instance, in rice, a trait of leaf K+ homeostasis upon salt stress, SKC1, has been shown to correspond to the OsHKT1;5 gene [124]. OsHKT1;5 transcripts were localized in vascular tissues, mainly xylem parenchyma, of both roots and shoots, a localization reminiscent of that of AtHKT1;1 [124]. Overall, this has suggested a role for OsHKT1;5 in Na+ retrieval from the xylem sap upon salt stress, similar to that for AtHKT1;1 ([124]; Fig. 3). In wheat, HKT1;5-like genes have also been found to correspond to trait loci of Na+ exclusion from shoots upon salt stress [132]. Traits controlled by these wheat HKT1;5-like genes were similar to those controlled by OsHKT1;5 in rice [124, 133–135], suggesting a similar function for rice and wheat HKT1;5 homologues [132]. A slightly different trait of Na+ exclusion upon salt stress was found to involve another HKT gene from subfamily 1 in wheat, HKT1;4 [131, 135]. The identification of different Na+ exclusion traits in wheat involving two different members from subfamily 1 supports the hypothesis that the different subfamily 1 members in monocotyledonous species play distinct roles in the control of Na+ transport in planta. This hypothesis has received further support from the analysis of the expression patterns of three HKT genes from subfamily 1 in rice, OsHKT1;1, 1;3, and 1;5 [119, 124]. OsHKT1;1 and OsHKT1;3 display wider expression patterns than OsHKT1;5, including leaf bulliform cells (large epidermal cells involved in leaf rolling) and root cortex in addition to root and shoot vasculature. This suggests possible additional roles, such as Na+ uptake from the soil solution or osmotic regulation in bulliform cells, for these two subfamily members [119].

Roles of HKT transporters permeable to both Na+ and K+

Monocotyledonous subfamily 2 transporters permeable to both Na+ and K+ (in heterologous systems) and active at the plasma membrane of root peripheral layers [14, 136] are strongly upregulated at the transcriptional level in response to K+ starvation. This suggests that these systems play a role in plant K+ nutrition in conditions of low K+ availability in the soil solution, but no direct support for this hypothesis has been obtained so far [137]. Furthermore, no indication of Na+-coupled K+ transport has been obtained in terrestrial higher plants [100, 138, 139]. However, the lack of evidence for K+ transport through such systems in planta might be due to redundancy in K+ transport systems, e.g., Shaker K+ channels and HAK/Kup/KT K+ transporters [31, 111]. On the other hand, a role for HKT2;1 transporters in root Na+ uptake has been demonstrated in several plant species [14, 137]. In wheat, a comparison of wild-type plants with transgenic lines displaying low levels of TaHKT2;1 transcripts has suggested that TaHKT2;1 is involved in root Na+ uptake in the presence of high external Na+ (100–200 mM) [137]. Recent analyses of Arabidopsis transgenic lines overexpressing a HKT2;1-type transporter from Puccinellia tenuiflora (a salt-tolerant monocotyledonous plant) have suggested an ability of this system to mediate Na+ uptake in planta, at least in conditions of high external Na+ [136]. In rice, OsHKT2;1 has been demonstrated to be involved in nutritional Na+ uptake by roots in conditions of severe K+ starvation (Fig. 3): when grown at submillimolar Na+ (0.5 mM) concentrations and nominal K+ concentrations, oshkt2;1 knock-out mutant rice lines displayed reduced Na+ uptake by roots, reduced Na+ content in root and shoot tissues and reduced size and biomass [14]. Thus, evidence is available that monocotyledonous subfamily 2 HKT2;1/2;2-type transporters can contribute to Na+ uptake in planta in a large Na+ concentration range.

Mechanisms of transport through plant HKT transporters

In general, plant HKT transporters proved to be efficiently expressed in yeast and Xenopus oocytes [30, 40, 117, 120, 122, 124, 126]. Combination of yeast growth tests, ion-flux measurements (K+ and Na+ net fluxes or Rb+ and Na+ tracer uptakes in yeast) and electrophysiology (in Xenopus oocytes) has provided a detailed view of the transport properties of some plant HKT transporters, revealing a complex behavior in several systems, e.g., existence of several conduction modes depending on external K+ and Na+ concentrations or on the level of expression [17, 117, 126, 140].

HKT transporters permeable to Na+ only (in dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species) have been shown to differ in their affinity for Na+ in at least one order of magnitude, within the millimolar range [30, 119, 122, 124]. Most HKT Na+ transporters are able to work in both inward and outward direction except for one system from rice, OsHKT1;1, which has been shown to strongly inwardly rectify when expressed in Xenopus oocytes [119]. Thermodynamically, reported variations of current reversal potentials with external Na+ activity (40–50 mV/decade) [30, 119, 127] are consistent with the hypothesis that these systems transport mainly Na+. H+ is probably not co-transported, since Na+ currents were shown to be insensitive to pH [30, 119]. Slight permeability of these systems to other ions, e.g., K+ or possibly Cl− (see fungal Trk above), besides Na+, is not excluded since the slopes of reported reversal potentials are lower than expected for highly selective systems. The mechanism of Na+ transport through these systems has not been further analyzed. It is also unknown whether the Na+-selective HKT systems could display channel-like behavior.

HKT transporters permeable to both Na+ and K+ mediate high-affinity K+ uptake and high or low-affinity Na+ uptake when expressed in yeast or Xenopus oocytes [17, 117, 119, 122, 136]. They are able to function in both the inward and outward directions [40, 117, 119]. They display different permeation modes depending on external Na+ and K+ concentrations. At low external Na+ and K+ concentrations, they behave essentially as Na+–K+ symporters, as demonstrated by Na+-stimulated K+ uptake and K+-stimulated Na+ uptake when expressed in yeast [117, 126]. In Xenopus oocytes, analyses of current reversal potential dependency on Na+ or K+ activity also argue for coupled Na+ and K+ transports at low external Na+ and K+ concentrations (below 1–10 mM [117, 119]). It should be noted that the permeability to Rb+, which is commonly used as a tracer of K+, can be strongly different from that to K+ in these transporters. For instance, Rb+ permeability is weak in TaHKT2;1 (e.g., Rb+ influx 15 times lower than K+ influx [17]), but seems to be similar to that of K+ in OsHKT2;1 [119]. H+ does not seem to permeate nor regulate these systems [119]. Different stoichiometries of coupling between K+ and Na+ transports have been proposed (between 1:1 and 2:1 [117, 119, 126]). It is unclear so far whether this depends on the transporter considered and/or on the experimental conditions (e.g., Na+ and K+ concentrations). At high external Na+ concentrations (above 1–10 mM), these transporters lose their permeability to K+ and become Na+-selective systems (Na+ uniporters [17, 40, 119]). Increases in external K+ concentrations have been shown to result in reduced transport activity (Na+ influx in yeast cells and the exogenous conductance in oocytes) both in the Na+–K+ symport and Na+ uniport modes of the transporter [17, 119, 122]. This inhibition has been interpreted as reflecting a non- or weakly conductive state of the transporter at high K+ concentrations [119].

To account for the dual mode of transport (Na+–K+ symport or Na+ uniport) in TaHKT2;1, Rubio et al. [117] and Gassmann et al. [17] have proposed that two high-affinity binding sites, one for K+ and the other one for Na+, named K+- and Na+-coupling sites, respectively, are present in the transporter and need to be occupied for uptake to occur. Competitive binding of K+ and Na+ at the K+-coupling site was hypothesized to determine the permeation mode of the transporter, namely Na+–K+ symport or Na+ uniport. Inhibition of symport activity by “high” external K+ could be explained in the framework of this model, assuming that the binding of K+ at the Na+ coupling site results in a non- or weakly conductive state [119]. The presence of a third binding site has been proposed to account for the observed inhibition of the Na+ uniport mode by external K+ in OsHKT2;1 [119]. The proposed coupling sites would not be accessible from the cytoplasmic face of the transporter since the different conduction modes seem to be controlled by external Na+ and K+.

Structure–function relationship of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters

Mutagenesis analyses and molecular basis of ion selectivity

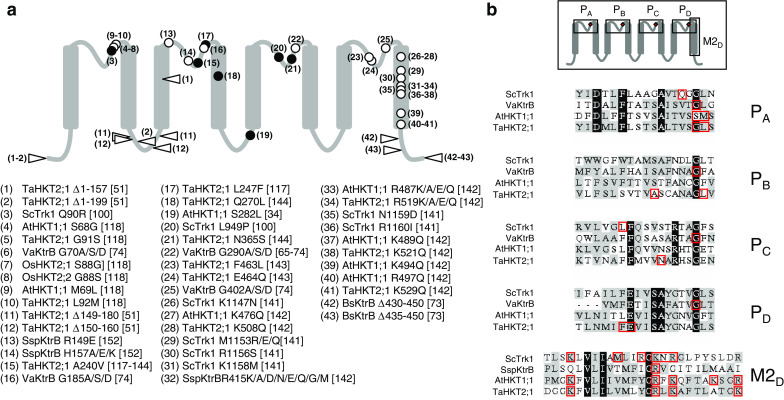

So far, most approaches aiming at deciphering the structure–function relationship of Trk/Ktr/HKT have been based on functional characterization of mutated transporters. Targeted residues in site-directed experiments have often been selected using the four-MPM structural model, essentially in the pore-forming regions and, to a lower extent, in the last transmembrane segment of the fourth MPM domain, which is predicted to interact with the innermost part of the pore [141, 142]. The effects of the mutations on the functional properties of the transporter were generally checked by comparing the ability of transformed cells (E. coli or S. cerevisiae) expressing either the wild-type or the mutated transporter to grow in the presence of low K+ and/or high Na+ concentrations. Differences in growth rate and in K+ and Na+ contents were taken as indications of changes in the transporter activity (V max) or affinity (K M) for K+ or Na+. For a few plant HKT transporters, in addition to functional studies in transformed S. cerevisiae cells, heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes and reversal potential analyses have provided more quantitative information on the changes in transporter permeability and ion selectivity. Figure 4 takes stock of these approaches as well as of mutational analyses performed before the four-MPM model was proposed [143], together with results from random mutagenesis experiments [100, 117, 144]. The whole set of data can be considered as consistent with the four-MPM model since most mutations targeting residues located in P domains affect transporter permeation properties. Attention has especially been focused on highly conserved glycine residues present in P regions at a position equivalent to that of a glycine in the selectivity filter of highly selective K+ channels. Mutagenesis experiments performed in bacterial Ktr and plant HKT [65, 74, 118], together with functional analyses of chimaeric transporters combining regions from different plant HKT transporters permeable or not to K+ [118] have led to the conclusion that K+ permeability requires the presence of glycine residues at the pinpointed positions in the pore domains. However, a plant HKT transporter (OsHKT2;1 from rice) whose first pore domain displays a serine instead of a glycine residue has recently been shown to be permeable to K+ [119], revealing that K+ permeability in HKT transporters does not depend only on the pinpointed pore glycine residues.

Fig. 4.

Structure–function relationship of Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters: compilation of data from mutagenesis studies using the four-MPM structural model. a Data from site-directed mutagenesis studies (open symbols; circle single-point mutation; triangle deletion) and from random mutagenesis (filled circles) are tentatively compiled along a diagrammatic representation of the four-MPM model, independently of the nature of the studied transporters (bacterial Ktr, fungal Trk, or plant HKT). Mutations are designated with numbers (facing the corresponding symbols in the diagrammatic representation). For each mutation (number), information regarding the corresponding organism and transporter, the mutated residue(s) and the literature reference is provided in the list below the diagram. b Transporters frequently used in site-directed mutagenesis analyses are the bacterial KtrB from V. alginolyticus and Synechocystis, the fungal Trk from S. cerevisiae and the plant transporters AtHKT1 from A. thaliana and TaHKT1 from T. aestivum. Sequence alignments of the four P regions (PA to PD) and of the last M2 transmembrane segment (M2D) from these four transporter proteins are shown. Mutated residues are boxed in red

A major interest of these mutagenesis studies is that they concern various transporters, cloned from different organisms and displaying distinctive ionic selectivities in terms of permeability to K+ and/or Na+. For instance, alignments of rather divergent transporter sequences known to display distinctive or common functional features may provide stimulating clues for investigating the structure–function relationship of these systems. However, at present, such comparative approaches are hampered by the fact that functional analyses have been performed in very different conditions, in terms of heterologous expression systems (E. coli or S. cerevisiae mutant strains, Xenopus oocytes), growth medium (for E. coli and S. cerevisiae transformed cells) and growth tests. It should also be emphasized that detailed electrophysiological analyses of mutated transporters are still too few [34, 117, 118, 142, 144]. Finally, while early in silico studies have suggested that Trk/Ktr/HKT ion-conducting transmembrane subunits form multimeric (probably tetrameric) structures [57], likely to give rise at the center of the multimeric assembly to an additional pore with distinctive permeation properties (possibly permeable to chloride [101–103] and above), such hypothesis of a multimeric structure has been poorly examined in mutagenesis experiments.

Structural data and models of permeation

The first resolved structure of a Trk/Ktr/HKT transporter will probably be obtained for a prokaryotic system. So far, structural analyses have essentially focused on regulatory KtrA-type subunits and the RCK/KTN (see above) domain of these proteins [59, 61, 73]. In each case, the solved structure contained RCK dimers. The most extensively characterized protein in these studies is probably the KtrA subunit from B. subtilis. The results have successively supported two conflicting models for the functional oligomeric arrangement of RCK domains: a tetrameric model (dimer of dimers) in the pioneering experiments [59], and an octameric model (tetramer of dimers) more recently [61].

RCK/KTN domains are also present in prokaryotic ligand-gated K+ channels and K+ efflux transport systems. Without exception, all the solved RCK/KTN structures comprise RCK/KTN homodimers. The dimeric arrangement displays a bilobed architecture. The lobe of each RCK domain has a Rossmann fold, and dimerization produces a cleft with potential ligand-binding sites between the two lobes [60, 145–148]. Interestingly, the Ca2+-gated K+ channel from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum MthK has been shown to comprise an octameric RCK structure [145–147], like recently proposed for the B. subtillis KtrA subunit [61]. It seems however, that octameric structures are not inherently necessary for RCK/KTN domain activity since a strictly dimeric arrangement, without any propensity to form higher-order assemblies, is more likely in the K+ efflux system KefC from E. coli [148].

The strictly conserved physical proximity of RCK/KTN domains to the cytoplasmic face of the transmembrane ion-conducting structure, close to the innermost pore region, suggests a crucial role in the regulation of the permeation process. Structural data strongly supporting this hypothesis have been obtained in the Ca2+-gated K+ channel MthK. Ca2+-binding or -unbinding to the channel RCK domains alters the relative orientation of the two RCK domains in the homodimer assembly. This can result in changes in the relative positions of the subunits within the RCK octameric ring, leading to expansion or contraction of the ring. These conformational changes would be transmitted to the transmembrane part of the channel, resulting in opening or closure of the pore [60, 145–147]. Thus, the RCK gating ring uses the free energy of Ca2+ binding to perform mechanical work to open the pore.

It is very likely that similar mechanisms, relying on conformational changes of the RCK/KTN ring upon ligand binding, are involved in regulation of prokaryotic Ktr transporters. Indeed, molecules known to play a role in the control of K+ uptake, NADH/NAD+ and ATP, can bind to the KtrA subunit from B. subtilis (as well as to that of Methanococcus jannaschii) [59]. Furthermore, evidence has been obtained that the octameric ring formed by the B. subtilis KtrA subunit complexed with NADH/NAD+ or ATP can adopt different conformations [61].

Regarding the structure of the whole Ktr system, biochemical analyses using B. subtilis KtrAB as a model indicate that the ion-conducting transmembrane subunit KtrB can exist as a stable dimer, both in the membrane and in solution in presence of detergent, the purified protein retaining its activity when reconstituted into liposomes [61, 73]. Similar indications that other transmembrane KtrB subunits can form homodimers have been obtained in Bacillus halodurans and Streptococcus pneumoniae Ktr systems [73]. Regions of the B. subtilis KtrB molecule that would be close to the interface of the two KtrB monomers within the dimeric structure have been probed using cysteine mutants and bifunctional cross-linkers [73]. The data are best explained within the framework of a model in which the two interacting KtrB monomers are present side-by-side, without extensive domain swapping since the removal of as little as ten residues from the C-terminus of KtrB causes the dimer to break down into stable monomers [61, 73]. Surprisingly, experimental evidence has been obtained (via size-exclusion chromatography experiments) that the KtrA/KtrB stoichiometry in the KtrAB protein complex is 8 RCK domains to 2 KtrB proteins, corresponding in all likelihood to one RCK octamer ring associated with a KtrB dimer. These results suggest that two permeation pathways are under the control of a single RCK octameric ring, which is in stark contrast to the original one ring/one pore model developed with the MthK channel [60, 145–147]. Of course, such a two-pore structure would raise the question as to whether the two permeation pathways are functionally independent. It is tempting to speculate that interactions between the two pathways could underlie co-transport activity and thereby active K+ transport in Trk/Ktr/HKT systems endowed with such properties.

So far, active transport by Trk/Ktr/HKT systems has been discussed within the framework of two models, the alternating-access model [3, 17, 100, 144] and the channel-like long pore model [74, 99]. The alternating access model describes carrier-mediated transport in terms analogous to enzyme kinetics. The transporter displays ion-binding sites and alternates between two conformations, in which the binding sites successively face the external or the internal medium. Ion exchanges between the binding sites and their surrounding medium occur as predicted by the mass action law and can therefore be described using the Michaelis–Menten formalism, in terms of (apparent) affinity constants. In the second model, permeation occurs through a long multi-substrate pore where several ions are simultaneously present. Because the pore is too narrow to allow the ions to pass one another, ions move in a single-file, hopping from one binding site to the next, each ion pushing the one ahead of it along. In this model, the exergonic flow of an ionic species in the pore down its electrochemical gradient is able to energize the endergonic flux of another ionic species by pushing it against its own gradient. Since Trk/Ktr/HKT have probably evolved from ion channels and are thought to display a channel-like permeation pathway, this latter model is likely to give a more realistic view of the transport process. However, the two models are not exclusive since the ion-binding sites and the two opposite transporter conformations postulated in the first model can respectively be thought of as corresponding to regions of the long pore and conformational changes of the pore [57]. As indicated above, analysis of Na+-K+ co-transport activity in a plant HKT transporter (OsHKT2;1 from rice; see above) within the framework of the alternating access model has led to hypothesize the presence of at least three binding sites: two coupling sites, one highly selective for K+ over Na+ and the other highly selective for Na+ over K+, and a regulatory site. The two selective coupling sites can be considered as ad hoc features taking into account that Na+–K+ symport activity was observed to display a fixed stoichiometry (1:1) within a large range of K+/Na+ concentration ratios [119]. Existence of a regulatory site allows to account for other complex properties of the transporter, such as strong blockage of transport activity by K+ when the concentration of this cation is raised in the mM range even in the presence of high Na+ concentrations (>30 mM) [119]. Faced with such a complexity, functional analyses have probably reached a limit in their ability to decipher the permeation mechanisms. It seems likely that further progress in understanding the permeation processes in Trk/Ktr/HKT systems will essentially depend on biochemical analyses and resolution of transporter structures.

Conclusions

The Trk/Ktr/HKT family is specific of non-animal cells and is one of the best-characterized families of transport systems, apart from ion channels. Trk/Ktr/HKT transporters are considered with increasing interest by a wide range of fundamental and applied disciplines, e.g., plant biology and agronomy [9, 14, 34, 122], cell biology [3, 117], or structural biology [57, 59, 61]). They play major roles in K+ entry into the living world [3, 8, 41], contribute to salt tolerance in cultivated plant species, and are likely to constitute potential targets for selective drug action since they have no close homologues in animals [103, 149–151]. At a molecular and mechanistic level, they offer the exciting opportunity to investigate transport or co-transport mechanisms in transporters displaying a channel-like permeation pathway, and thereby to decipher evolutionary relationships between channels and transporters [55–57]. Regarding the latter field of research, the functional diversity and complexity found in the Trk/Ktr/HKT family can be considered as a source of difficulties at the present moment, in particular due to the relative lack of structural data. It is very likely, however, that in the future, this diversity and complexity will reinforce the interest of the Trk/Ktr/HKT model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ina Talke (Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, Potsdam, Germany) for critical reading and helpful corrections of the manuscript. This work was supported by the ANR Génoplante TRANSPORTOME (ANR_06_GPLA_012 to C.C.-F.).

References

- 1.Schultz SG, Solomon AK. Cation transport in Escherichia coli. I. Intracellular Na and K concentrations and net cation movement. J Gen Physiol. 1961;45:355–369. doi: 10.1085/jgp.45.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarkson DT, Hanson JB. The mineral nutrition of higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1980;31:239–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.31.060180.001323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodríguez-Navarro A. Potassium transport in fungi and plants. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2000;1469:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(99)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashley MK, Grant M, Grabov A. Plant responses to potassium deficiencies: a role for potassium transport proteins. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:425–436. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein W, Schultz SG. Cation transport in Escherichia coli. V. Regulation of cation content. J Gen Physiol. 1965;49:221–234. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhoads DB, Waters FB, Epstein W. Cation transport in Escherichia coli. VIII. Potassium transport mutants. J Gen Physiol. 1976;67:325–341. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]