Abstract

Drugs targeting the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) remain the most efficacious analgesics for the treatment of pain, but activation of MOR with current opioid analgesics also produces harmful side effects, notably physical dependence, addiction, and respiratory depression. Opioid peptides have been accepted as promising candidates for the development of safer and more efficacious analgesics. To develop peptide-based opioid analgesics, strategies such as modification of endogenous opioid peptides, development of multifunctional opioid peptides, G-protein biased opioid peptides, and peripherally restricted opioid peptides have been reported. This review seeks to provide an overview of the opioid peptides that produce potent antinociception with much reduced side effects in animal models and highlight the potential advantages of peptides as safer opioid analgesics.

Keywords: peptide, opioid receptor ligand, safe analgesic, pain, structural modification

Introduction

The endogenous opioid system primarily modulates pain through the activation of the three classical opioid receptors, the μ- (MOR), δ- (DOR), and κ- (KOR) opioid receptors. While activating either receptor subtype produces analgesia, each receptor differentially mediates the adverse effects. Activation of MOR is linked to physical dependence, euphoria, and respiratory depression; activation of DOR causes convulsant effect and activation of KOR is associated with dysphoric and aversive effects. As a natural response to pain, the endogenous opioid peptides such as β-endorphin, enkephalins, and dynorphins are released from the enzymatic cleavage of their respective precursors proopiomelanocortin, proenkephalin, and prodynorphin.1 The endogenous opioid peptides and their related receptors are broadly expressed across the pain pathways. By binding to and activating the three opioid receptors, these endogenous opioid peptides act together to block pain signaling.2

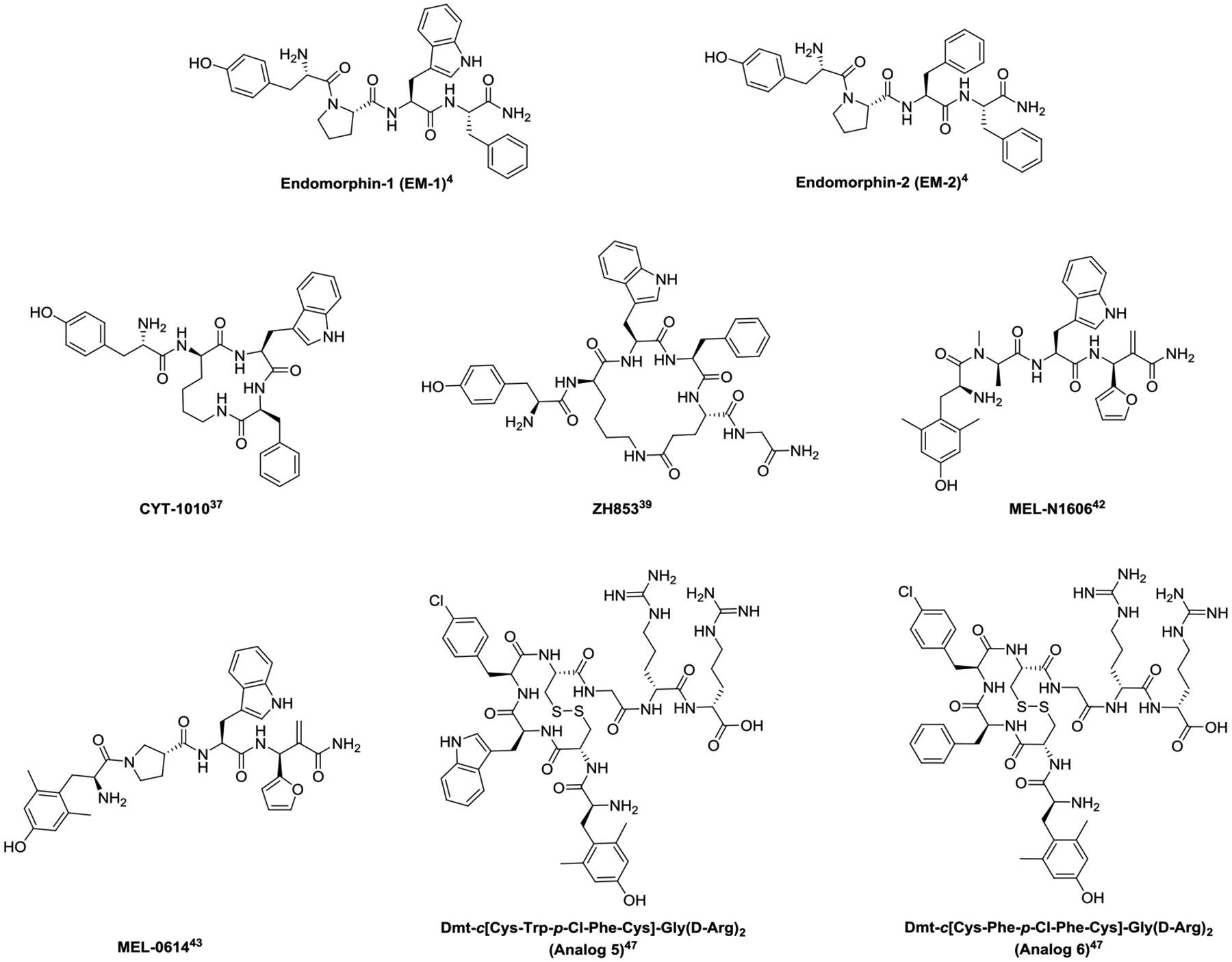

Endomorphins, EM-1 (Tyr1-Pro2-Trp3-Phe4, Fig. 1) and EM-2 (Tyr1-Pro2-Phe3-Phe4, Fig. 1) are another set of endogenous opioid peptides that have been isolated from bovine brains3 and human brain cortex tissues.4 However, whether EM-1 and EM-2 are endogenous in nature is not certain because the sequences are not found in the human genome and no precursors have been identified. EMs selectively bind to and activate the MOR.5 Among the endogenous opioid peptides, EM-1 and EM-2 have the highest binding affinity (Ki, μ = 0.36 ± 0.08 nM and 0.69 ± 0.16 nM, respectively) and selectivity for the MOR4 (δ/μ = 4,183 and 13,381, respectively, and κ/μ = 15,077 and 7,594, respectively). Intrathecal (i.t.) or intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of EMs produce efficacious antinociception in rodents, which is blocked by naloxone and MOR-selective antagonists β-funaltrexamine.6–7 Spinal administration of EM-1 produces analgesia with 6-time higher potency than morphine,8 and both EM-1 and EM-2 are without cardiorespiratory effects.9

Figure 1.

Structures of endomorphin analogs

The endogenous opioid system relieves pain without producing adverse effects; this differs dramatically from the small molecule opioid pain medications, which produce potent analgesia while exhibiting notorious side effects such as physical dependence, tolerance, addiction, respiratory depression, and constipation. However, endogenous opioid peptides cannot be directly utilized as drugs because they are rapidly inactivated by enzymatic degradation in vivo.10 To improve their pharmacokinetic property, various synthetic strategies, e.g., cyclization,11 D-amino acid12 or N-methylated amino acid13 replacements, stapling,14 lipidation,15 and glycosylation16 have been developed to modify the structures of the opioid peptides. These efforts have led to the synthesis and identification of a diverse array of close and distal analogs that exhibit improved stability and bioavailability compared with the parent endogenous opioid peptides.

Like small molecule opioid ligands, opioid peptides have also been designed to produce the distinct functional activities, such as G-protein biased agonism,17 dual- or multi-functional opioid activitis,18 and peripherally restricted opioid activities19 for fewer side effects. Compared to small molecule opioid ligands, opioid peptide ligands are more hydrophilic, larger in size, and less permeable to cell membrane. These physicochemical characteristics provide peptides with some unique advantages over small molecules in the context of safer opioid analgesics.

First, opioid peptides bind to the opioid receptors at more extended areas compared with small molecules. Like small molecules, opioid peptides reach to and bind at the bottom of the orthosteric binding pocket; additionally, they interact with the receptor at the extracellular loops as well.20 Simultaneous engagement of the orthosteric binding pocket and the extracellular vestibule of GPCRs has shown to cause additional conformational restriction of the receptor, leading to functional selectivity (bias) through increased specificity of signal transducer binding.21–23 Secondly, opioid peptides activate opioid receptors in a distinct receptor activation pattern that involves both plasma membrane and endosomal activations, while small molecule drugs, in addition to activating receptors at plasma membrane and endosomes, readily penetrate the cell membrane to drive the internal activation into the Golgi apparatus.24 The spatiotemporal specificity affects signal duration and downstream pathway selection, contributing to distinct downstream physiological effects.25–27 This suggests that the membrane permeability of ligand may have an impact on the therapeutic and side-effect profiles of opioid analgesics. In addition, opioid peptides have an analgesic duration profile shorter than small molecules.28–29 However, opioid peptides generally show fewer side effects than classic short-acting pain treatment such as fentanyl.

A great amount of research efforts has been conducted on the design, synthesis, and identification of peptide-based opioid ligands.30–33 For brevity, this review will primarily focus on opioid peptide ligands that have been reported to demonstrate potent antinociception with attenuated adverse effects in vivo. For a broader review of safer opioid ligands please refer to Varga et al. 2023,34 for a review of opioid peptidomimetics please refer to Lee 2022,35 and for a broader review of non-morphinan based opioid ligands please refer to Smith et al. 2022.36

Endomorphin Analogs

Since the discovery of EMs, various structural modification strategies have been utilized to improve their proteolytic stability/bioavailability. Cyclization of EMs has resulted in some EM analogs that produce potent antinociception with substantially reduced abuse potential and absence of respiratory depression in rodent models. Cyclic EM analogs are often achieved by replacing the Pro2 with a D-Lys2 and cyclizing through its side chain and the carboxylic terminal. CYT-1010 (Fig. 1), a cyclic EM-1 analog, maintains selective and potent binding at the MOR.37 CYT-1010 is under phase II clinical trials for pain management. In the phase I clinical trials, administration of CYT-1010 (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.) produces antinociception in the cold pressor test for pain without depressing breath at 0.15 mg/kg (i.v.) in human males.38

Adding Glu5 and Gly-NH26 to EM-1 while cyclizing through the side chains of the D-Lys2 and Glu5 leads to ZH853 (Fig. 1). In addition to producing potent and safer antinociception for treating acute pain in mice,39 ZH853 also provides effective pain relief in chronic pain models,40 shortens recovery time from inflammatory and postoperative pain and prevents the development of latent sensitization.41

Incorporating unnatural amino acids into peptides improves their stability against enzymatic degradation. Two distal EM analogs, MEL-N1606 and MEL-0614 (Fig. 1), generated from replacing multiple residues with unnatural amino acids show equal or greater antinociception but significant reduction of side-effect profile relative to morphine.42 MEL-N1906 has three replacements of Tyr1 with 2’,6’-dimethyl tyrosine (Dmt), Pro2 with N-Me-D-Ala, and Phe4 with (2-furyl)-α-methylene-β-amino propanoic acid, while MEL-0614 incorporates a β-Pro2. MEL-0614 also inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may account for their ability to modulate inflammatory pain.43

Conjugating an oligoarginine peptide to EM at C-terminus also improves its stability and bioavailability, as oligoarginine can enhance the delivery of peptides into cell and brain.44–45 Although attaching an oligoarginine to EM does not improve the binding affinity to MOR, its half-life in mouse brain and serum increases 3–5-fold over that of EM-1, indicating enhanced stability in serum and permeability to blood-brain barrier (BBB).46 Attaching an oligoarginine vector to cyclic EM analogs results in “Analog 5” (Dmt-c[Cys-Trp-p-Cl-Phe-Cys]-Gly-(D-Arg)2, Fig. 1) and “Analog 6” (Dmt-c[Cys-Phe(p-Cl)-Phe-Cys]-Gly-(D-Arg)2, Fig. 1). Analogs 5 and 6 produce potent antinociception in mice yet significantly less tolerance after chronic administration, significantly less constipation and locomotive impairment, and significantly less (Analog 5) or no (Analog 6) conditioned place preference compared to morphine.47

EM-2 analogs have been synthesized by replacing one or two of the residues with unnatural amino acids; these analogs showed selective agonism at MOR with varying degrees of bias toward G-protein. While none of them have been tested in animal models for analgesia or adverse effects, they may serve as a tool to understand the biological and pharmacological significance of biased agonism at MOR for safer opioid analgesia.48

Bifunctional and Multifunctional Opioid Peptides

Simultaneously interacting with two or more opioid receptor types, as well as activation of an opioid receptor and a non-opioid receptor can lead to efficacious pain relief with reduced side effects. This has been demonstrated by co-administration of DAMGO and DPDPE,49 chronic co-administration of morphine and naltrindole,50 and the bifunctional MOR/KOR ligands,51 MOR/NOP dual agonists,52 bifunctional MOR/σ1 ligands,53 and others MOR/non-opioid ligands.54–55 Though the mechanism is not currently known, evidence suggests these receptors may interact with and modulate each other.56–57 In the endogenous opioid system, while an individual endogenous opioid peptide preferentially activates one receptor over the other, as a whole they activate all opioid receptors.58 This mixed/balanced effects of the endogenous opioid peptides may account for their powerful analgesia without producing side effects.

MOR /DOR Dual Functional Peptides

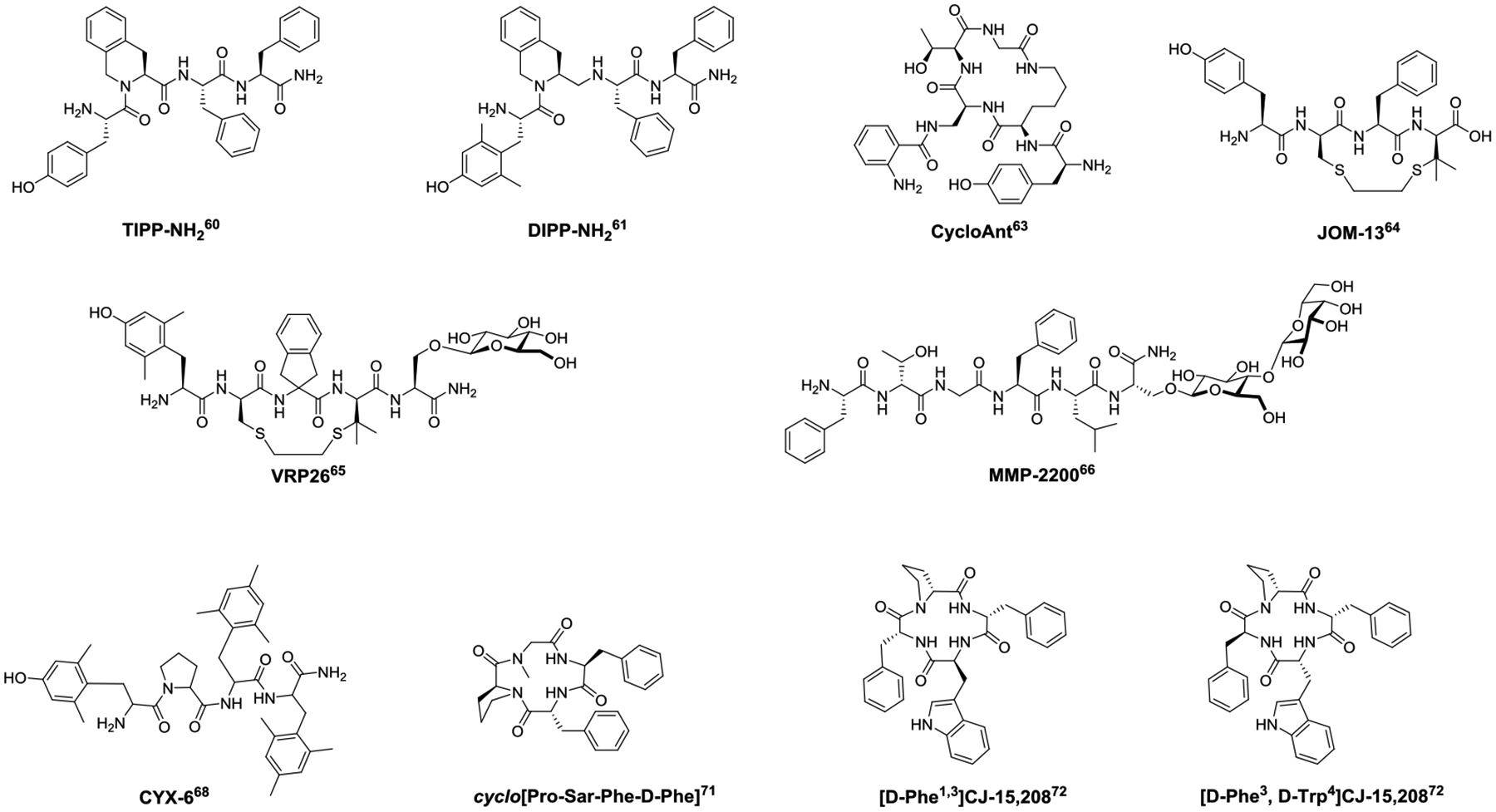

Dual functional peptide ligands activating MOR yet antagonizing DOR have shown efficacious analgesia with significantly improved side effect profiles compared to morphine.59 The first reported mixed MOR agonist/DOR antagonist peptide is TIPP-NH2 (Tyr-Tic-Phe-Phe-NH2) (Fig. 2), an EM-1 analog with a Pro2-to-Tic2 replacement.60 Replacement of Tyr1 with 3,5-dimethyltyrocine (Dmt) yielded DIPP-NH2; further introduction of a reduced peptide bond at Dmt-Tic yielded DIPP-NH2[Ψ] (Dmt-TicΨ[CH2NH]Phe-Phe-NH2) (Fig. 2).61 However, these peptides with mixed function of MOR agonist/DOR antagonist are unstable in vivo, limiting their application to tool compounds.62

Figure 2.

Structures of bifunctional and multifunctional opioid peptides.

Cyclized bifunctional MOR agonist/DOR antagonist peptides have a significantly improved in vivo stability profile. CycloAnt (Tyr-[D-Lys-Dap(Ant)-Thr-Gly]) (Fig. 2), a MOR agonist/DOR antagonist, was identified from deconvolution of a mixture-based cyclic peptide library containing 24,624 individual peptides using a phenotypic screening in mice.63 CycloAnt produces dose- and time-dependent antinociception with an ED50 of 0.7 mg/kg after intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration. It does not produce respiratory depression at doses up to 15 times the analgesic ED50. Chronic i.p. administration of CycloAnt at 3 mg/kg does not result in opioid-induced hyperalgesia, and significantly reduces signs of naloxone-precipitated withdrawal. The potent antinociception and low liability profile suggests it has a preferred pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile for systemic use as a potentially safer pain modulator.63 Other cyclic peptide-based MOR agonists/DOR antagonists include JOM-1364 (Tyr-c[D-Cys-Phe-D-Pen]OH) (Fig. 2) and VRP2665 (Dmt-c(SEtS)[DCys-Aic-DPen]-Ser(Glc)-NH2) (Fig. 2), which are cyclized by disulfide or dithioether bonds. VRP26 also incorporates a glycosylated serine Ser(Glc)5 and a tetrahydroquinoline motif (Aic)4. VRP26 produces a maximal antinociceptive effect at 10 mg/kg i.p. with an ED50 of 4.77 mg/kg. Mice given VRP26 at analgesic dose for 7 days do not develop significant tolerance, conditioned place preference, or naltrexone-precipitated withdrawal symptoms.64

Interestingly, dual functional MOR/DOR agonists have also been reported to produce potent antinociception with fewer opioid-associated side effects, demonstrated by MMP-2200, a derivative of Leu-enkephalin incorporating a Gly2-to-Thr2 replacement and a glycosylated Ser(Glc)6(Fig. 2). Compared to morphine, MMP-2200 produces significantly less naloxone precipitated withdrawal symptoms or antinociceptive tolerance, and does not show conditioned place preference.66–67 Therefore, peptides simultaneously modulating MOR and DOR hold great promise for the development of safe analgesics.

Multifunctional Opioid Peptides

Multifunctional ligands interacting with all three opioid receptors also produce potent and safer analgesia. CYX-6 (Fig. 2) (H-Dmt-Pro-Tmp-Tmp-NH2, where Tmp is a 2’,4’,6’-trimethylphenylalanine), with a mixed function of MOR agonist and DOR/KOR antagonist, shows potent antinociception with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory side effects after i.c.v. administration.68

Structural modification of a naturally occurring peptide CJ-15,208, cyclo[Phe-D-Pro-Phe-Trp] has yielded several multifunctional opioid peptides. CJ-15,208 binds primarily at the KOR, with an IC50 value of 47 nM, 260 nM, and 2600 nM, to the KOR, MOR, and DOR respectively.69 Both [L-Trp4]-CJ-15,208 and [D-Trp4]-CJ-15,208 isomers display KOR- and MOR- mediated antinociception.70 Modification of CJ-15,208 resulted in Cyclo[Pro-Sar-Phe-D-Phe] (Fig. 2), which is a dual KOR/MOR agonist and produces potent antinociception without MOR- and KOR-mediated side effects such as locomotive impairment, ambulation, respiratory depression, conditioned place preference or aversion.71 Investigation of the stereoisomeric effects of the Phe1,3 residues of CJ-15,208 led to the discovery of analogs with diverse in vivo functional profiles mediated by multiple opioid receptors, with [D-Phe1,3]CJ-15,208 (Fig. 2) primarily activating KOR and DOR, and [D-Phe3, D-Trp4]CJ-15,208 (Fig. 2) activating all three opioid receptors. These stereoisomers are orally active.72

G Protein-Biased Opioid Peptides

Activated opioid receptors are known to couple to two distinct downstream signaling pathways, mediated by G-protein and the β-arrestin, respectively. Preferential activation of the G-protein signaling pathway may lead to enhanced analgesia with reduced adverse effects.73–74

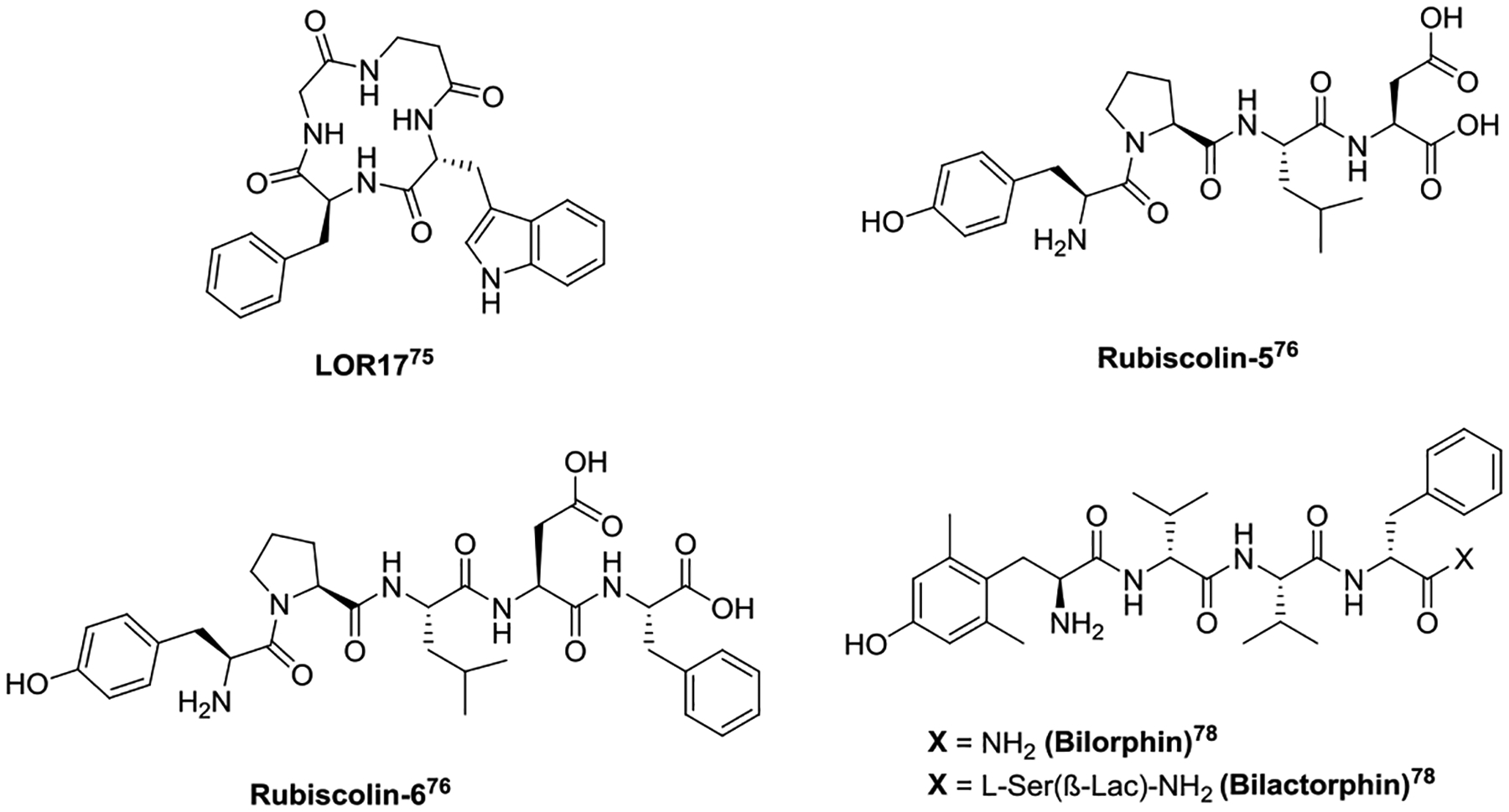

LOR17 (c[Phe-Gly-β-Ala-D-Trp]) (Fig. 3), a KOR-selective, G protein-biased agonist, provides significant antinociception in the mouse models of acute, inflammatory, and cancer pain without the KOR-associated side effects.75 Naturally occurring peptides Rubiscolin-5 (Tyr-Pro-Leu-Asp-Leu) (Fig. 3) and rubiscolin-6 (Tyr-Pro-Leu-Asp-Leu-Phe) (Fig. 3), which are derived from the large subunit of the enzyme spinach rubisco, are two DOR-selective, G protein-biased agonists. Both peptides show significant antinociceptive effects following i.c.v. or oral (p.o.) administration.76 Currently rubiscolin-6 (Rubixyl®) is under clinical evaluation for its potential to repair skin damage.77

Figure 3.

Structures of biased opioid peptides.

Derived from the naturally occurring peptide Bilaid C(Tyr-D-Val-Val-D-Phe), bilorphin (Dmt-D-Val-Val-D-Phe-NH2) (Fig. 3) is a potent and selective G protein-biased MOR agonist. Bilorphin only produces antinociception in mice after i.t. administration. Coupling a L-Ser(β-Lac)5 at bilorphin’s C-terminus resulted in the glycosylated analog bilactorphin (Fig. 3), which shows efficacious analgesia after subcutaneous (s.c.) (ED50 = 35 μmol/kg) as well as p.o. administration. Though bilactorphin does not possess the G protein-biased profile, glycosylation provided an effective way to improve the BBB permeability of a peptide.78

Peripherally Restricted Opioid Peptides

Opioid receptors are widely expressed throughout the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Under inflammatory condition, the expression levels of opioid receptors in the peripheral neuron are upregulated; inflammatory milieu may also improve opioid receptor function by more efficiently coupling to G-protein and inhibiting cAMP production.79–80 Restriction of opioid ligands to PNS can produce peripheral opioid analgesia whiling eliminating the adverse effects associated with activating the receptors in the CNS.81 Peptides generally have limited BBB accessibility; they are promising candidates for targeting opioid receptors in PNS.

Peripherally Restricted Peptide KOR agonists

KOR agonists are promising candidates for developing safer analgesics as they produce antinociception without the side effects of respiratory depression, tolerance, and addiction. In addition to pain, KOR agonists also can modulate inflammation, mood, and reward. However, activation of KOR in CNS can result in sedation, dysphoria, and hallucinations, limiting the clinical application of CNS-acting KOR agonists. Peripherally restricted KOR agonists have therefore received a lot of interest for the development of safer analgesics.

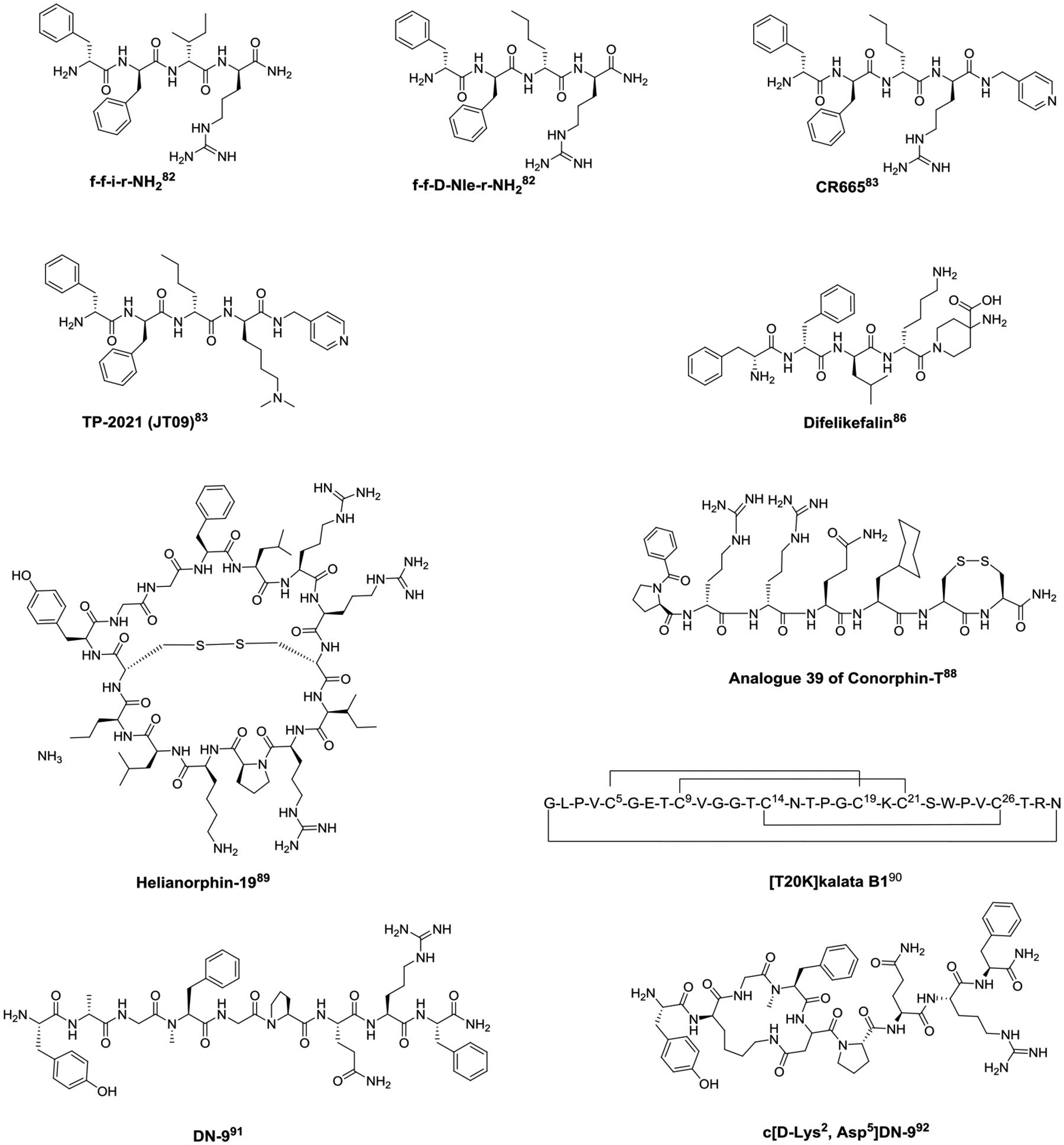

Several peripherally restricted KOR agonists are reported to provide potent analgesic activity without dysphoria or euphoria. These KOR ligands possess all D-amino acids and are analogs of the tetrapeptides f-f-i-r-NH2 (Fig. 4) and f-f-D-Nle-r-NH2 (Fig. 4) that were initially identified from screening a mixture-based tetrapeptide library.82 Capping the C-terminus of f-f-D-Nle-r-NH2 with 4-(aminomethyl)pyridine generated CR665 (Fig. 4). Replacing the D-Arg4 with Nε-dimethyl-D-lysine at CR665 led to the discovery of TP-2021 (formerly JT09, Fig. 4).83 CR665 and TP-2021 are both under clinical trial for their therapeutic application in pain management.84–85 Structural modification of f-f-i-r-NH2 has resulted in an FDA approved drug Difelikefalin (Fig. 4), which has the D-Leu3-to-D-Ile3 and D-Lys4-to-D-Arg4 replacements and a C-terminal capping with 4-aminopiperidinine-4-carboxylic acid. Difelikefalin is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe pruritus in hemodialysis patients;86 no symptoms of physical dependence were observed 2 weeks after discontinuation.87

Figure 4.

Structures of peripherally restricted opioid peptides.

Screening a synthetic peptide library constituted of marine cone snail venom derived peptides led to the discovery of Conorphin-T (NCCRRQICC), which exhibits moderate, selective agonism for KOR. Extensive structural modification of Conorphin-T resulted in Analogue 39 (Bz-PrrQ[CHA]CC-NH2) (Fig. 4), which selectively binds to and produces potent agonism at KOR, and has improved plasma stability compared to its parent peptide.88 Analogue 39 also demonstrated analgesia in a mouse model of colonic visceral hypersensitivity after administration to the mucosal surface of the colon, suggesting it may be useful in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.

Employing the molecular grafting approach to insert the dynorphin A 1–13 sequence into the scaffold of a plant-derived cyclotide generated a KOR agonist Helianorphin-19 (c-CYGGFLRRCIRPKLK) (Fig. 4). Helianorphin-19 produces potent KOR-regulated antinociception in the chronic visceral hypersensitivity mouse model after intracolonic administration, but neither alters mouse motor coordination in the rotarod test nor exhibits sensitivity for central pain in the jump-flinch test comparing to centrally active KOR agonist U50,488, suggesting a peripherally restricted KOR agonist may be clinically useful for the treatment of chronic abdominal pain.89

[T20K]kalata B1 (cyclo-GLPVCGETCVGGTCNTPGCTCSWPVCTRN), an orally bioavailable peptide found in ipeca root powder, is a candidate drug for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. T20K has recently been identified as a positive allosteric modulator of KOR, which increases the efficacy of dynorphin A1−13 and the potency and efficacy of U50,488 in functional cAMP assays.90 The discovery of T20K highlights the potential to design novel cyclotide-based allosteric modulators of KOR for developing safer treatments for pain as well as multiple sclerosis.

Other peripherally restricted opioid peptides

In addition to the peripherally restricted KOR agonist, DN-9 (Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-NMe-Phe-Gly-Pro-Gln-Arg-Phe-NH2) (Fig. 4) is reportedly a multifunctional MOR/KOR/neuropeptide FF receptor agonist that displays effective analgesia following s.c. administration in the mouse acute, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain models.91 A D-Ala2-to-D-Lys2 together with a Gly5-to-Asp5 replacement and subsequently cyclization through D-Lys2 and Asp5 led to the discovery of the amide cyclic DN-9 analog c[D-Lys2, Asp5]-DN-9 (Fig. 4). c[D-Lys2, Asp5]-DN-9 not only provides more potent analgesia than DN-9 after s.c. and p.o. administration in mice, but it can also be orally administrated.92 Though DN-9 and the c[D-Lys2, Asp5]-DN-9 are peripherally restricted, the cyclic disulfide analog of DN-9, OFP011 (c[D-Cys2, Cys5]-DN-9)93, and the hydrocarbon-stapled analogs94 are brain-permeable. The CNS-acting DN-9 analogs also show reduced side effects, suggesting their multifunctional activity is the main drive for low side-effect profile.

Future Perspectives for Opioid Peptides

The X-ray crystal structures of the MOR, DOR, and KOR were first reported in 2012, all of which are in antagonist-bound inactive states.95–98 The recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), particularly the single-particle cryo-EM technique, which provides comparable resolution to X-ray crystallography, have triggered an explosion of the structural determination of the opioid receptors. Crystal and cryo-EM structures of the opioid receptors have been reported not only in the agonist-bound active states99–101 but also in complex with G protein.102–106 The high-resolution cryo-EM structures of the entire family of opioid receptors in complex with the Gi protein and bound to their respective, highly selective endogenous or exogenous opioid peptides have recently been elucidated.20 These cryo-EM structures have offered molecular insights into the interactions between opioid peptides and their receptors. These new insights provide a molecular framework for the rational design and creation of new peptide or peptide-inspired ligands that can interact with their receptors in a similar way as do the endogenous opioid peptides.

Though many of the opioid peptides discussed in this review were discovered through traditional SAR studies, structure-based design has shown promises in designing opioid ligands through fine-tuning the opioid receptor-ligand interactions to improve their pharmacological profiles. Many successes have been achieved to discover safer small-molecule opioid ligands using structure-based design.107–108 Fentanyl derivatives were recently designed to target the MOR at both the orthosteric binding region and the Na+ binding pocket, which has been hypothesized to act as an efficacy and functional selectivity switch for opioid receptors, leading to biased and/or partial agonism. These derivatives demonstrated potent and effective analgesia with significantly fewer adverse effects than morphine.109

While small molecule ligands can be designed to interact with the Na+ binding subpocket and extracellular vestibule subpocket, opioid peptides with a relative larger molecular size may target both the orthosteric site and an additional subpocket more effectively to offer enhanced functional selectivity. Recently a computational approach was developed to design conjugates of De Novo cyclic peptide (DNCP) and β-naloxamine (β-NalA), a KOR partial agonist with a morphinan structure. The cryo-EM structure of human KOR bound to DNCP-β-NalA and G protein heterotrimer showed that the conjugate occupies the orthosteric binding site by β-NalA as well as the extracellular region with the DNCP moiety surrounded by ECL2, ECL3, TM6, and TM7. DNCP-β-NalA produces a potent KOR-mediated antinociception and anti-inflammatory effects, with reduced KOR-mediated side-effects in male mice.110 With the crystal and cryo-EM structures of the peptide-bound receptors and the advancements in algorithms for molecular modeling and dynamic simulations, we anticipate that the rational design and creation of new peptide or peptide-inspired safer opioid analgesics will be significantly facilitated.

Conclusion

Pain not only affects patients with impaired physical functioning and reduced quality of life, but also increases by 2–3 times anxiety, mood, and mental disorders in patients. While opioids remain the most effective analgesics, it is more crucial than ever to develop safer and efficacious opioid analgesics. In addition to their higher target affinity and lower toxicity relative to small molecules, opioid peptides may provide extra advantages over small molecule opioids due to their relatively larger size and higher hydrophilicity. Their larger size may help them engage additional subpockets of opioid receptors, leading to more selective downstream signaling, and partial and/or biased agonism, while their higher hydrophilicity may restrict them to the peripheral nervous system and/or prevent them from quickly reaching to and activating the Golgi opioid receptors after activation in membrane.

In the past, peptides were generally viewed as suboptimal drug candidates due to their poor bioavailability and metabolic instability. Recent advances in peptide synthesis such as cyclization, incorporation of D-amino acids or unnatural amino acids have led to metabolic stable opioid peptides.111 Furthermore, advances in formulation and drug delivery systems may provide solutions to overcome this barrier.112–113 Recent intranasal delivery of the opioid peptide antagonist, CTOP demonstrated improved brain delivery and enhanced antagonism in morphine-treated mice.114 This intranasal drug delivery technique may also improve the delivery of safer peptide opioid agonists to the brain.

The ligands highlighted in this review demonstrate that opioid peptides can produce potent analgesia with attenuated adverse effects through a variety of mechanisms. Multifunctional, biased, and peripherally restricted opioid peptides, as well as endomorphin analogs have all been proven to be promising methods for the development of safer opioid analgesics. With the high-resolution structures of each receptor type in complex with endogenous opioid peptides, design of opioid peptides that act biasedly, selectively or with mixed actions at opioid receptor types is achievable. Recent research on opioid receptor signaling, peptide structural modification, and drug formulation and delivery have deemed opioid peptides more advantageous than ever before.115–116

Footnotes

Peptide-based opioid ligands are promising candidates for the discovery and development of efficacious, safer, and non-/less addictive analgesics.

Declaration. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Margolis EB, Moulton MG, Lambeth PS, O’Meara MJ. The life and times of endogenous opioid peptides: Updated understanding of synthesis, spatiotemporal dynamics, and the clinical impact in alcohol use disorder. Neuropharmacol 2023; 225:109376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomes I, Sierra S, Lueptow L, Gupta A, Gouty S, Margolis EB, Cox BM, Devi LA. Biased signaling by endogenous opioid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2020; 117(21): 11820–11828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zadina JE, Hackler L, Ge LJ, Kastin AJ. A potent and selective endogenous agonist for the mu-opiate receptor. Nature 1997; 386(6624):499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackler L, Zadina JE, Ge LJ, Kastin AJ. Isolation of relatively large amounts of endomorphin-1 and endomorphin-2 from human brain cortex. Peptides 1997; 18(10):1635–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zadina JE, Hackler L, Ge LJ, Kastin AJ. A potent and selective endogenous agonist for the μ-opioid receptor. Nature 1997; 386: 499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone LS, Fairbanks CA, Laughlin TM, Nguyen HO, Bushy TM, Wessendorf MW, Wilcox GL. Spinal analgesic actions of the new endogenous opioid peptides endomorphin-1 and −2. Neuroreport 1997; 8(14):3131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg IE, Rossi GC, Letchworth SR, Mathis JP, Ryan-Moro J, Leventhal L, Su W, Emmel D, Bolan EA, Pasternak GW. Pharmacological characterization of Endomorphin-1 and Endomorphin-2 in mouse brain. J Pharmacol Exper Ther 1998; 286:1007–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Przewłocki R, Labuz D, Mika J, Przewłocka B, Tomboly C, Toth G. Pain inhibition by endomorphins. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999; 897:154–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czapla MA, Gozal D, Alea OA, Beckerman RC, Zadina JE. Differential cardiorespiratory effects of endomorphin 1, endomorphin 2, DAMGO, and morphine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162(3 Pt 1):994–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Manna S, Di Natale C, Florio D, Marasco D. Peptides as therapeutic agents for inflammatory-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19(9):2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perlikowska R, do-Rego JC, Cravezic A, Fichna J, Wyrebska A, Toth G, Janecka A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of cyclic endomorphin-2 analogs. Peptides 2010; 31(2):339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao L, Luo K, Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang D, Ma M, Zhou J, Cui J, Wang J, Han CZ, Liu X, Wang R. Design, synthesis, and biological activity of new endomorphin analogs with multi-site modifications. Bioorg Med Chem 2020; 28(9):115438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamska-Bartłomiejczyk A, Janecka A, Szabó MR, Cerlesi MC, Calo G, Kluczyk A, Tömböly C, Borics A. Cyclic mu-opioid receptor ligands containing multiple N-methylated amino acid residues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2017; 27: 1644–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muratspahić E, White AM, Ciotu CI, Hochrainer N, Tomašević N, Koehbach J, Lewis RJ, Spetea M, Fischer MJM, Craik DJ, Gruber CW. Development of a Selective Peptide κ-Opioid Receptor Antagonist by Late-Stage Functionalization with Cysteine Staples. J Med Chem 2023; 66:11843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varamini P, Mansfeld FM, Blanchfield JT, Wyse BD, Smith MT, Toth I. Lipo-endomorphin-1 derivatives with systemic activity against neuropathic pain without producing constipation. PLoS One 2012;7(8): e41909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosberg HI, Yeomans L, Anand JP, Porter V, Sobczyk-Kojiro K, Traynor JR, Jutkiewicz EM. Development of a bioavailable μ opioid receptor (μOR) agonist, δ opioid receptor (ΔOR) antagonist peptide that evokes antinociception without development of acute tolerance. J Med Chem 2014; 57:3148–3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conibear AE, Kelly E. A Biased view of μ-opioid receptors? Mol Pharmacol 2019; 96(5):542–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand JP, Montgomery D. Multifunctional opioid ligands. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2018; 247:21–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidhammer H, Al-Khrasani M, Fürst S, Spetea M. Peripheralization strategies applied to morphinans and implications for improved treatment of pain. Molecules 2023; 28(12):4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Zhuang Y, DiBerto JF, Zhou XE, Schmitz GP, Yuan Q, Jain MK, Liu W, Melcher K, Jiang Y, Roth BL, Xu HE. Structures of the entire human opioid receptor family. Cell 2023; 186(2):413–427.e17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Männel B, Hübner H, Möller D, Gmeiner P. β-Arrestin biased dopamine D2 receptor partial agonists: Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation. Bioorg Med Chem 2017; 25(20):5613–5628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCorvy JD, Butler KV, Kelly B, Rechsteiner K, Karpiak J, Betz RM, Kormos BL, Shoichet BK, Dror RO, Jin J, Roth BL. Structure-inspired design of β-arrestin-biased ligands for aminergic GPCRs. Nat Chem Biol 2018; 14(2):126–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bock A, Merten N, Schrage R, Dallanoce C, Bätz J, Klöckner J, Schmitz J, Matera C, Simon K, Kebig A, Peters L, Müller A, Schrobang-Ley J, Tränkle C, Hoffmann C, De Amici M, Holzgrabe U, Kostenis E, Mohr K. The allosteric vestibule of a seven transmembrane helical receptor controls G-protein coupling. Nat Commun 2012; 3:1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoeber M, Jullié D, Lobingier BT, Laeremans T, Steyaert J, Schiller PW, Manglik A, von Zastrow M. A genetically encoded biosensor reveals location bias of opioid drug action. Neuron 2018; 98(5):963–976.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godbole A, Lyga S, Lohse MJ, Calebiro D. Internalized TSH receptors en route to the TGN induce local Gs-protein signaling and gene transcription. Nat Commun 2017; 8(1):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsvetanova NG, von Zastrow M. Spatial encoding of cyclic AMP signaling specificity by GPCR endocytosis. Nat Chem Biol 2014; 10(12):1061–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunselman JM, Gupta A, Gomes I, Devi LA, Puthenveedu MA. Compartment-specific opioid receptor signaling is selectively modulated by different dynorphin peptides. Elife 2021; 10:e60270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aldrich JV, Patkar KA, McLaughlin JP. Zyklophin, a systemically active selective kappa opioid receptor peptide antagonist with short duration of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106(43):18396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nastase AF, Anand JP, Bender AM, Montgomery D, Griggs NW, Fernandez TJ, Jutkiewicz EM, Traynor JR, Mosberg HI. Dual Pharmacophores Explored via Structure−Activity Relationship (SAR) Matrix: Insights into Potent, Bifunctional Opioid Ligand Design. J Med Chem 2019; 62:4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Dooley CT, Misler JA, Debevec G, Giulianotti MA, Cazares ME, Maida L, Houghten RA. Fluorescent mu selective opioid ligands from a mixture based cyclic peptide library. ACS Comb Sci 2012; 14(12), 673–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mollica A, Guardiani G, Davis P, Ma SW, Porreca F, Lai J, Mannina L, Sobolev AP, Hruby VJ. Synthesis of stable and potent δ/μ opioid peptides: analogues of H-Tyr-c[D-Cys-Gly-Phe-D-Cys]-OH by ring-closing metathesis. J Med Chem 2007; 50:3138–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perlikowska R, Piekielna J, Gentilucci L, De Marco R, Cerlesi MC, Calo G, Artali R, Tömböly C, Kluczyk A, Janecka A. Synthesis of mixed MOR/KOR efficacy cyclic opioid peptide analogs with antinociceptive activity after systemic administration. Eur J Med Chem 2016; 109:276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamska-Bartłomiejczyk A, Janecka A, Szabó MR, Cerlesi MC, Calo G, Kluczyk A, Tömböly C, Borics A. Cyclic mu-opioid receptor ligands containing multiple N-methylated amino acid residues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2017; 27:1644–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varga BR, Streicher JM, Majumdar S. Strategies towards safer opioid analgesics-A review of old and upcoming targets. Br J Pharmacol 2023;180(7):975–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YS. Peptidomimetics and their applications for opioid peptide drug discovery. Biomolecules 2022; 12(9):1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith MT, Kong D, Kuo A, Imam MZ, Williams CM. Analgesic opioid ligand discovery based on nonmorphinan scaffolds derived from natural sources. J Med Chem 2022; 65(3):1612–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webster L, Schmidt WK. Dilemma of addiction and respiratory depression in the treatment of pain: A prototypical endomorphin as a new approach. Pain Med 2020; 21(5):992–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maione TE, Zadina JE, Fillingham R, Copa A, Cooper R. A phase I study of CYT-1010, a stabilized endomorphin I analog, in healthy male volunteers with additional pharmacodynamic evaluations (A1415). Poster presented at: American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting; October 15–19, 2011; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zadina JE, Nilges MR, Morgenweck J, Zhang X, Hackler L, Fasold MB. Endomorphin analog analgesics with reduced abuse liability, respiratory depression, motor impairment, tolerance, and glial activation relative to morphine. Neuropharmacology 2016; 105:215–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feehan AK, Morgenweck J, Zhang X, Amgott-Kwan AT, Zadina JE. Novel endomorphin analogs are more potent and longer-lasting analgesics in neuropathic, inflammatory, postoperative, and visceral pain relative to morphine. J Pain 2017; 18(12):1526–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feehan AK, Zadina JE. Morphine immunomodulation prolongs inflammatory and postoperative pain while the novel analgesic ZH853 accelerates recovery and protects against latent sensitization. J Neuroinflammation 2019; 16(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Zhao L, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Yang D, Mou L, Wang R. MEL-N16: A series of novel endomorphin analogs with good analgesic activity and a favorable side effect profile. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017; 8(10):2180–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui JM, Zhao L, Wang ZJ, Ma MT, Wang Y, Luo KY, Wang LQ, Wei S, Zhang XH, Han CZ, Liu X, Wang R. MEL endomorphins act as potent inflammatory analgesics with the inhibition of activated non-neuronal cells and modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Neuropharmacology 2020; 168:107992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang SR, Kim SB, Joe CO, Kim JD. Intracellular delivery enhancement of poly(amino acid) drug carriers by oligoarginine conjugation. J Biomed Mater Res A 2008; 86(1):137–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pham W, Zhao BQ, Lo EH, Medarova Z, Rosen B, Moore A. Crossing the blood-brain barrier: a potential application of myristoylated polyarginine for in vivo neuroimaging. Neuroimage 2005;28(1):287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang CL, Qiu TT, Diao YX, Zhang Y, Gu N. Novel endomorphin-1 analogs with C-terminal oligoarginine-conjugation display systemic antinociceptive activity with less gastrointestinal side effects. Biochimie 2015; 116:24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang YZ, Wang MM, Wang SY, Wang XF, Yang WJ, Zhao YN, Han FT, Zhang Y, Gu N, Wang CL. Novel Cyclic Endomorphin analogues with multiple modifications and oligoarginine vector exhibit potent antinociception with reduced opioid-like side effects. J Med Chem 2021; 64(22):16801–16819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piekielna-Ciesielska J, Malfacini D, Djeujo FM, Marconato C, Wtorek K, Calo’ G, Janecka A. Functional selectivity of EM-2 analogs at the mu-opioid receptor. Front Pharmacol 2023; 14:1133961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sutters KA, Miaskowski C, Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Analgesic synergy and improved motor function produced by combinations of mu-delta- and mu-kappa-opioids. Brain Res 1990; 530(2):290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdelhamid EE, Sultana M, Portoghese PS, Takemori AE. Selective blockage of delta opioid receptors prevents the development of morphine tolerance and dependence in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1991; 258(1):299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Provencher BA, Sromek AW, Li W, Russell S, Chartoff E, Knapp BI, Bidlack JM, Neumeyer JL. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of aminothiazolomorphinans at the mu and kappa opioid receptors. J Med Chem 2013; 56:8872–8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiguchi N, Ding H, Cami-Kobeci G, Sukhtankar DD, Czoty PW, DeLoid HB, Hsu F-C, Toll L, Husbands SM, Ko M-C. BU10038 as a safe opioid analgesic with fewer side effects after systemic and intrathecal administration in primates. Br J Anaesth 2019; 122: e95ee97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhuang T, Xiong J, Hao S, Du W, Liu Z, Liu B, Zhang G, Chen Y. Bifunctional μ opioid and σ1 receptor ligands as novel analgesics with reduced side effects. Eur J Med Chem 2021; 223:113658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cunningham CW, Elballa WM, Vold SU. Bifunctional opioid receptor ligands as novel analgesics. Neuropharmacology 2019; 151:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Starnowska-Sokół J, Przewłocka B. Multifunctional opioid-derived hybrids in neuropathic pain: Preclinical evidence, ideas and challenges. Molecules 2020; 25(23):5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Traynor JR, Elliott J. Delta-opioid receptor subtypes and cross-talk with mu-receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1993; 14(3):84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matthes HW, Smadja C, Valverde O, Vonesch JL, Foutz AS, Boudinot E, Denavit-Saubié M, Severini C, Negri L, Roques BP, Maldonado R, Kieffer BL. Activity of the delta-opioid receptor is partially reduced, whereas activity of the kappa-receptor is maintained in mice lacking the mu-receptor. J Neurosci 1998; 18(18):7285–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Froehlich JC. Opioid peptides. Alcohol Health Res World 1997; 21(2):132–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wtorek K, Piekielna-Ciesielska J, Janecki T, Janecka A. The search for opioid analgesics with limited tolerance liability. Peptides 2020; 130:170331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schiller PW, Nguyen TM, Weltrowska G, Wilkes BC, Marsden BJ, Lemieux C, Chung NN. Differential stereochemical requirements of mu vs. delta opioid receptors for ligand binding and signal transduction: development of a class of potent and highly delta-selective peptide antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992; 89(24):11871–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schiller PW, Fundytus ME, Merovitz L, Weltrowska G, Nguyen TM, Lemieux C, Chung NN, Coderre TJ. The opioid mu agonist/delta antagonist DIPP-NH2[Ψ] produces a potent analgesic effect, no physical dependence, and less tolerance than morphine in rats. J Med Chem 1999; 42(18):3520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aldrich JV, Kumar V, Murray TF, Guang W, Wang JB. Dual labeled peptides as tools to study receptors: nanomolar affinity derivatives of TIPP (Tyr-Tic-Phe-Phe) containing an affinity label and biotin as probes of delta opioid receptors. Bioconjug Chem 2009; 20(2):201–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Y, Eans SO, Ganno-Sherwood M, Eliasof A, Houghten RA, McLaughlin JP. Identification and pharmacological characterization of a low-liability antinociceptive bifunctional MOR/DOR cyclic peptide. Molecules 2023; 28(22):7548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mosberg HI, Omnaas JR, Medzihradsky F, Smith CB. Cyclic, disulfide- and dithioether-containing opioid tetrapeptides: development of a ligand with high delta opioid receptor selectivity and affinity. Life Sci 1988; 43(12):1013–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anand JP, Boyer BT, Mosberg HI, Jutkiewicz EM. The behavioral effects of a mixed efficacy antinociceptive peptide, VRP26, following chronic administration in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016; 233(13) :2479–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lowery JJ, Raymond TJ, Giuvelis D, Bidlack JM, Polt R, Bilsky EJ. In vivo characterization of MMP-2200, a mixed δ/μ opioid agonist, in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2011; 336(3):767–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stevenson GW, Luginbuhl A, Dunbar C, LaVigne J, Dutra J, Atherton P, Bell B, Cone K, Giuvelis D, Polt R, Streicher JM, Bilsky EJ. The mixed-action delta/mu opioid agonist MMP-2200 does not produce conditioned place preference but does maintain drug self-administration in rats, and induces in vitro markers of tolerance and dependence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2015; 132:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Imam MZ, Kuo A, Ghassabian S, Cai Y, Qin Y, Li T, Smith MT. Intracerebroventricular administration of CYX-6, a potent μ-opioid receptor agonist, a δ- and κ-opioid receptor antagonist and a biased ligand at μ, δ & κ-opioid receptors, evokes antinociception with minimal constipation and respiratory depression in rats in contrast to morphine. Eur J Pharmacol 2020; 871:172918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saito T, Hirai H, Kim YJ, Kojima Y, Matsunaga Y, Nishida H, Sakakibara T, Suga O, Sujaku T, Kojima N. CJ-15,208, a novel kappa opioid receptor antagonist from a fungus, Ctenomyces serratus ATCC15502. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2002; 55(10):847–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ross NC, Reilley KJ, Murray TF, Aldrich JV, McLaughlin JP. Novel opioid cyclic tetrapeptides: Trp isomers of CJ-15,208 exhibit distinct opioid receptor agonism and short-acting κ opioid receptor antagonism. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 165(4b):1097–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brice-Tutt AC, Wilson LL, Eans SO, Stacy HM, Simons CA, Simpson GG, Coleman JS, Ferracane MJ, Aldrich JV, McLaughlin JP. Multifunctional opioid receptor agonism and antagonism by a novel macrocyclic tetrapeptide prevents reinstatement of morphine-seeking behaviour. Br J Pharmacol 2020; 177(18):4209–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brice-Tutt AC, Senadheera SN, Ganno ML, Eans SO, Khaliq T, Murray TF, McLaughlin JP, Aldrich JV. Phenylalanine stereoisomers of CJ-15,208 and [d-Trp]CJ-15,208 exhibit distinctly different opioid activity profiles. Molecules 2020; 25(17):3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature 2000; 408(6813):720–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM. Morphine side effects in beta-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 314(3):1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bedini A, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Micheli L, Baiula M, Vaca G, De Marco R, Gentilucci L, Ghelardini C, Spampinato S. Functional selectivity and antinociceptive effects of a novel KOR agonist. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang S, Yunden J, Sonoda S, Doyama N, Lipkowski AW, Kawamura Y, Yoshikawa M. Rubiscolin, a delta selective opioid peptide derived from plant Rubisco. FEBS Lett 2001; 509(2):213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chajra H, Amstutz B, Schweikert K, Auriol D, Redziniak G, Lefèvre F. Opioid receptor delta as a global modulator of skin differentiation and barrier function repair. Int J Cosmet Sci 2015; 37(4):386–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dekan Z, Sianati S, Yousuf A, Sutcliffe KJ, Gillis A, Mallet C, Singh P, Jin AH, Wang AM, Mohammadi SA, Stewart M, Ratnayake R, Fontaine F, Lacey E, Piggott AM, Du YP, Canals M, Sessions RB, Kelly E, Capon RJ, Alewood PF, Christie MJ. A tetrapeptide class of biased analgesics from an Australian fungus targets the μ-opioid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019; 116(44):22353–22358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stein C, Machelska H. Modulation of peripheral sensory neurons by the immune system: implications for pain therapy. Pharmacol Rev 2011; 63(4):860–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stein C Towards safer and more effective analgesia. Vet J 2013; 196, 6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Machelska H; Celik M; Advances in achieving opioid analgesia without side effects. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9:1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dooley CT, Ny P, Bidlack JM, Houghten RA. Selective ligands for the m, d, and k opioid receptors identified from a single mixture based tetrapeptide positional scanning combinatorial library. J Biol Chem 1998; 273(30):18848–18856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beck TC, Reichel CM, Helke KL, Bhadsavle SS, Dix TA. Non-addictive orally-active kappa opioid agonists for the treatment of peripheral pain in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2019; 856:172396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arendt-Nielsen L, Olesen AE, Staahl C, Menzaghi F, Kell S, Wong GY, Drewes AM. Analgesic efficacy of peripheral kappa-opioid receptor agonist CR665 compared to oxycodone in a multi-modal, multi-tissue experimental human pain model: selective effect on visceral pain. Anesthesiology 2009; 111(3):616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Titan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2021, November 08). Sustained aint-pruritic effect of Titan’s TP-2021 implant reported today at neuroscience 2021. [Press release]. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/sustained-anti-pruritic-effect-of-titans-tp-2021-implant-reported-today-at-neuroscience-2021-301418931.html

- 86.Santino F, Gentilucci L. Design of κ-opioid receptor agonists for the development of potential treatments of pain with reduced side effects. Molecules 2023; 28(1):346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fishbane S, Jamal A, Munera C, Wen W, Menzaghi F. A phase 3 trial of difelikefalin in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(3):222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brust A, Croker DE, Colless B, Ragnarsson L, Andersson Å, Jain K, Garcia-Caraballo S, Castro J, Brierley SM, Alewood PF, Lewis RJ. J Med Chem 2016; 59:2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Muratspahić E, Tomašević N, Koehbach J, Duerrauer L, Hadžić S, Castro J, Schober G, Sideromenos S, Clark RJ, Brierley SM, Craik DJ, Gruber CW. J Med Chem 2021; 64:9042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Muratspahić E, Tomašević N, Nasrollahi-Shirazi S, Gattringer J, Emser FS, Freissmuth M, Gruber CW. Plant-derived cycliotides modulate k-opioid receptor signaling. J Nat Prod 2021; 84:2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu B, Zhang M, Shi X, Zhang R, Chen D, Chen Y, Wang Z, Qiu Y, Zhang T, Xu K, Zhang X, Liedtke W, Wang R, Fang Q. The multifunctional peptide DN-9 produced peripherally acting antinociception in inflammatory and neuropathic pain via μ- and κ-opioid receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2020; 177(1):93–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang M, Xu B, Li N, Zhang R, Zhang Q, Shi X, Xu K, Xiao J, Chen D, Niu J, Shi Y, Fang Q. Development of multifunctional and orally active cyclic peptide agonists of opioid/neuropeptide FF receptors that produce potent, long-lasting, and peripherally restricted antinociception with diminished side effects. J Med Chem 2021; 64(18):13394–13409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang M, Xu B, Li N, Zhang R, Zhang Q, Chen D, Rizvi SFA, Xu K, Shi Y, Yu B, Fang Q. OFP011 Cyclic Peptide as a Multifunctional Agonist for Opioid/Neuropeptide FF Receptors with Improved Blood−Brain Barrier Penetration. ACS Chem Neurosci 2022; 13:3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang M, Xu B, Li N, Zhang Q, Chen D, Wu S, Yu B, Zhang X, Hu X, Zhang S, Jing Y, Yang Z, Jiang J, Fang Q. All-Hydrocarbon Stapled Peptide Multifunctional Agonists at Opioid and Neuropeptide FF Receptors: Highly Potent, Long-Lasting Brain Permeant Analgesics with Diminished Side Effects. J Med Chem 2023; 66:17138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, Pardo L, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Granier S. Crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 2012; 485(7398):321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu H, Wacker D, Mileni M, Katritch V, Han GW, Vardy E, Liu W, Thompson AA, Huang XP, Carroll FI, Mascarella SW, Westkaemper RB, Mosier PD, Roth BL, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure of the human κ-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature 2012; 485(7398):327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Granier S, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. Structure of the δ-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature 2012; 485(7398):400–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thompson AA, Liu W, Chun E, Katritch V, Wu H, Vardy E, Huang XP, Trapella C, Guerrini R, Calo G, Roth BL, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor in complex with a peptide mimetic. Nature 2012; 485(7398):395–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, Kato HE, Livingston KE, Thorsen TS, Kling RC, Granier S, Gmeiner P, Husbands SM, Traynor JR, Weis WI, Steyaert J, Dror RO, Kobilka BK. Structural insights into μ-opioid receptor activation. Nature 2015; 524(7565):315–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhuang Y, Wang Y, He B, He X, Zhou XE, Guo S, Rao Q, Yang J, Liu J, Zhou Q, Wang X, Liu M, Liu W, Jiang X, Yang D, Jiang H, Shen J, Melcher K, Chen H, Jiang Y, Cheng X, Wang MW, Xie X, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of morphine and fentanyl by the human μ-opioid receptor. Cell 2022; 185(23):4361–4375.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Claff T, Yu J, Blais V, Patel N, Martin C, Wu L, Han GW, Holleran BJ, Van der Poorten O, White KL, Hanson MA, Sarret P, Gendron L, Cherezov V, Katritch V, Ballet S, Liu ZJ, Müller CE, Stevens RC. Elucidating the active δ-opioid receptor crystal structure with peptide and small-molecule agonists. Sci Adv 2019; 5(11): eaax9115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Koehl A, Hu H, Maeda S, Zhang Y, Qu Q, Paggi JM, Latorraca NR, Hilger D, Dawson R, Matile H, Schertler GFX, Granier S, Weis WI, Dror RO, Manglik A, Skiniotis G, Kobilka BK. Structure of the μ-opioid receptor-Gi protein complex. Nature 2018; 558(7711):547–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang H, Hetzer F, Huang W, Qu Q, Meyerowitz J, Kaindl J, Hübner H, Skiniotis G, Kobilka BK, Gmeiner P. Structure-based evolution of G protein-biased μ-opioid receptor agonists. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2022; 61(26):e202200269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qu Q, Huang W, Aydin D, Paggi JM, Seven AB, Wang H, Chakraborty S, Che T, DiBerto JF, Robertson MJ, Inoue A, Suomivuori CM, Roth BL, Majumdar S, Dror RO, Kobilka BK, Skiniotis G. Insights into distinct signaling profiles of the μOR activated by diverse agonists. Nat Chem Biol 2023; 19(4):423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Han J, Zhang J, Nazarova AL, Bernhard SM, Krumm BE, Zhao L, Lam JH, Rangari VA, Majumdar S, Nichols DE, Katritch V, Yuan P, Fay JF, Che T. Ligand and G-protein selectivity in the κ-opioid receptor. Nature 2023; 617(7960):417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen Y, Chen B, Wu T, Zhou F, Xu F. Cryo-EM structure of human κ-opioid receptor-Gi complex bound to an endogenous agonist dynorphin A. Protein Cell 2023; 14:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao B, Li W, Sun L, Fu W. The Use of computational approaches in the discovery and mechanism study of opioid analgesics. Front Chem 2020; 8:335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Uprety R, Che T, Zaidi SA, Grinnell SG, Varga BR, Faouzi A, Slocum ST, Allaoa A, Varadi A, Nelson M, Bernhard SM, Kulko E, Le Rouzic V, Eans SO, Simons CA, Hunkele A, Subrath J, Pan YX, Javitch JA, McLaughlin JP, Roth BL, Pasternak GW, Katritch V, Majumdar S. Controlling opioid receptor functional selectivity by targeting distinct subpockets of the orthosteric site. Elife 2021; 10:e56519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Faouzi A, Wang H, Zaidi SA, DiBerto JF, Che T, Qu Q, Robertson MJ, Madasu MK, El Daibani A, Varga BR, Zhang T, Ruiz C, Liu S, Xu J, Appourchaux K, Slocum ST, Eans SO, Cameron MD, Al-Hasani R, Pan YX, Roth BL, McLaughlin JP, Skiniotis G, Katritch V, Kobilka BK, Majumdar S. Structure-based design of bitopic ligands for the μ-opioid receptor. Nature 2023; 613(7945):767–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Muratspahić E, Deibler K, Han J, Tomašević N, Jadhav KB, Olivé-Marti AL, Hochrainer N, Hellinger R, Koehbach J, Fay JF, Rahman MH, Hegazy L, Craven TW, Varga BR, Bhardwaj G, Appourchaux K, Majumdar S, Muttenthaler M, Hosseinzadeh P, Craik DJ, Spetea M, Che T, Baker D, Gruber CW. Design and structural validation of peptide-drug conjugate ligands of the kappa-opioid receptor. Nat Commun 2023; 14(1):8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang L, Wang N, Zhang W, Cheng X, Yan Z, Shao G, Wang X, Wang R, Fu C. Therapeutic peptides: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022; 7:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cesaro A, Lin S, Pardi N, de la Fuente-Nunez C. Advanced delivery systems for peptide antibiotics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2023; 196:114733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jamaledin R, Di Natale C, Onesto V, Taraghdari ZB, Zare EN, Makvandi P, Vecchione R, Netti PA. Progress in Microneedle-Mediated Protein Delivery. J Clin Med 2020; 9(2):542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rayala R, Tiller A, Majumder SA, Stacy HM, Eans SO, Nedovic A, McLaughlin JP, Cudic P. Solid-phase synthesis of the bicyclic peptide OL-CTOP containing two disulfide bridges, and an assessment of its in vivo μ-opioid receptor antagonism after nasal administration. Molecules 2023; 28(4):1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Davenport AP, Scully CCG, de Graaf C, Brown AJH, Maguire JJ. Advances in therapeutic peptides targeting G protein- coupled receptors. Nat Rev Drug Disc 2020; 19:389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Muttenthaler M, King GF, Adams DJ, Alewood PF. Trends in peptide drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Disc 2021; 20:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]