Patients who have had cardiovascular disease and stroke are treated with aspirin to reduce their subsequent risk of vascular events or death and thereby to increase the length and quality of their life. This guideline aims to provide general practitioners with evidence linked recommendations on the use of aspirin as secondary prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease and stroke in patients at high risk of these disorders. It is assumed that doctors will use their knowledge and clinical judgment in managing individual patients in the light of available resources. Recommendations may not be appropriate for use in all circumstances. This is a summary of the full version of the guideline.1

Summary points

The use of aspirin in the secondary prophylaxis of vascular disease is cost effective

Aspirin should be used in patients with acute myocardial infarction, prior myocardial infarction, stable and unstable angina, and prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack

In acute myocardial infarction a dose of 150 mg daily should be used

In the other indications a dose of 75 mg daily should be used

Incidence

In general practice, patients with a raised risk of vascular disease present with several disorders—acute or previous myocardial infarction, unstable or stable angina, transient ischaemic attacks, and peripheral vascular disease. The incidence and prevalence of these conditions and the workload associated with them in general practice can be estimated from the recent national morbidity survey in general practice for England and Wales, and is shown in the table.2

Categorising evidence

Throughout this guideline the strength of statements on evidence and of recommendations is categorised according to the scheme discussed in the first paper in the series.3 The box below shows these categories in descending order of importance.

Categories of strength used in statements

Strength of evidence Ia—Evidence from meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials Ib—Evidence from at least one randomised controlled trial IIa—Evidence from at least one controlled study without randomisation IIb—Evidence from at least one other type of quasi-experimental study III—Evidence from descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies, and case-control studies IV—Evidence from expert committee reports or opinions or clinical experience of respected authorities, or both Strength of recommendations A—Directly based on category I evidence B—Directly based on category II evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I evidence C—Directly based on category III evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I or II evidence D—Directly based on category IV evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I, II, or III evidence

Use of aspirin

Aspirin as an antiplatelet agent

The potential importance of aspirin treatment in patients with a raised risk of vascular diseases has been well described in a recent meta-analysis, the latest update of work reported by the Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaborative Group.4 The treatment recommendations in this guideline draw on that work and, where necessary, develop it further by including subsequent trials. We have calculated a pooled risk ratio in relation to clinical subgroups and overall for the impact of antiplatelet treatment on subsequent myocardial infarction, stroke, and death from vascular causes.

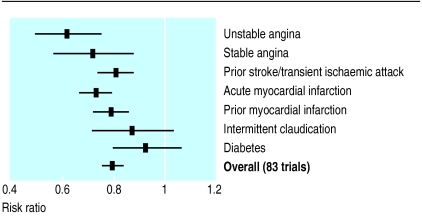

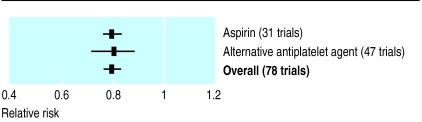

This meta-analysis of 83 randomised trials on antiplatelet treatment is summarised in figure 1, which shows that the overall pooled risk ratio is 0.79 (95% confidence interval 0.76% to 0.82%). Tests for heterogeneity provide good evidence of homogeneity between the trials included in this analysis (Q=74.81, df=82, P=0.70). Thus, strong evidence exists that antiplatelet treatment has a protective effect in patients at raised vascular risk. Trials used several different antiplatelet drugs, including aspirin. Indirect comparison of trials in which aspirin or an alternative antiplatelet drug was used provides no evidence of systematic differences in effect (fig 2).

Figure 1.

Risk ratio of non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes in patients at high risk of a vascular event. Meta-analysis of 83 trials

Figure 2.

Relative risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes in patients at high risk of a vascular event who were taking aspirin or an alternative antiplatelet drug. Meta-analysis of 78 trials

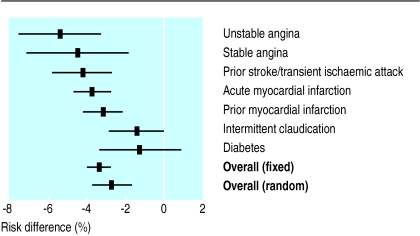

Substantially different risk reductions in mortality and morbidity are found for different disorders. This may be confounded by differences in the design of studies (particularly the length of follow up), but nevertheless reflects true variation in the potential benefits of treatment in diverse groups of patients. Pooled risk differences for each disorder are described in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Risk differences (%) for non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes in patients at high risk of a vascular event treated or not treated with an antiplatelet agent

While 5% of patients in the unstable angina trials benefit from aspirin, the mean benefit in patients with diabetes is much smaller, and the confidence intervals around it are wide. The overall estimate of effect is 3.4% (2.9% to 4.0%) in the fixed effects model. The substantial heterogeneity of effect between studies is unlikely to have occurred by chance (Q=107.38, df=82, P=0.032). The pooled estimate of overall effect in relation to the random effects model is 2.7% (1.7% to 3.7%).

Duration of treatment

The major trials of aspirin have used different study durations ranging from 1 to 48 months. Those recommendations that are made for treatment over a time period covered by the evidence from clinical trials are designated “A”; those that result from extrapolation beyond the period covered by a trial are designated “D.” However, in the case of unstable angina, a “D” recommendation was upgraded. This is because the evidence from trials in these patients extends for 18 months, and the guideline development group felt that after this time patients could be regarded as having stable angina and be treated under the recommendations for that condition.

Dosage of aspirin

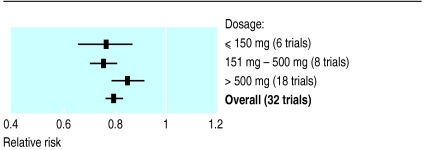

Trials have used different doses of aspirin; more recent trials have tended to use lower doses. There is no evidence that aspirin in doses greater than 75 mg provides greater benefit, and three recent major trials have used this regimen.5–8 Comparison of the effects of treatment in studies examined here, or in the broader range of comparisons reported by the antiplatelet trialists’ collaboration, shows no evidence of differences (fig 4).4 We have therefore recommended that the dosage for antiplatelet treatment should be 75 mg of aspirin daily, except in the case of acute myocardial infarction, where most of the evidence is provided by a single trial using twice that dose.9

Figure 4.

Relative risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes in relation to treatment with aspirin or an alternative antiplatelet agent. Meta-analysis of 32 trials

Aspirin and vascular disease

Acute myocardial infarction

Statement: giving aspirin within 24 hours of acute myocardial infarction lowers the risk of a vascular event over the subsequent month (Ia)

Nine trials have examined the role of antiplatelet treatment after acute myocardial infarction.9–19 These trials provide a pooled risk difference of 3.8% (2.8% to 4.7%). The pooled incidence rate difference, shown by random effects model, estimates that antiplatelet treatment for one month results in a 3.3% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes—or a number needed to treat value of 30. Limited follow up from the second international study of infarct survival9 indicates that the benefit of one month’s treatment with aspirin may be maintained for four years.20

Recommendations: acute myocardial infarction

Patients with a suspected acute myocardial infarction should be treated with 150 mg of aspirin daily (A)

Patients with proved acute myocardial infarction should be given 150 mg of aspirin daily for one month (A)

After one month, patients should be treated according to the section on previous myocardial infarction (A)

Previous myocardial infarction

Statement: aspirin given to patients who have previously had a myocardial infarction lowers their risk of a subsequent vascular event (Ia)

Within this area of investigation there are 11 trials, and average treatment periods vary from 12 to 41 months.21–40 Overall, these trials give a risk difference of 3.2% (2.2% to 4.2%) for myocardial infarction, stroke, or vascular death. The pooled incidence rate difference, shown by random effects model, estimates that antiplatelet treatment for one year results in a 1.5% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes—or a number needed to treat of 65.

Recommendations: previous myocardial infarction

Patients who have previously had a myocardial infarction should be treated with 75 mg of aspirin daily for three years (A)

After three years, aspirin should be continued long term at a dose of 75 mg daily (D)

Stable angina

Statement: aspirin given to patients with stable angina lowers their risk of having a subsequent vascular event (Ia)

In the six studies examining the effectiveness of antiplatelet treatment for patients with stable angina, the overall risk difference was 4.5% (1.9% to 7.1%).5,40–46 The pooled incidence rate difference, shown by random effects model, estimates that antiplatelet treatment for one year results in a 0.7% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes—or a number needed to treat of 150.

Recommendations: stable angina

Patients who have stable angina should be treated with aspirin 75 mg daily for four years (A)

After four years, aspirin should be continued long term at a dose of 75 mg daily (D)

Unstable angina

Aspirin given to patients with unstable angina lowers their risk of having a subsequent vascular event (Ia)

Seven trials provide evidence of the effectiveness of antiplatelet treatment in unstable angina.7,47–54 Overall, a risk difference of 5.5% (3.4% to 7.5%) in the incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes was achieved. There is no evidence of heterogeneity between estimates of treatment effect (Q=8.72, df=6, P=0.19). The pooled incidence rate difference, shown by random effects model, estimates that antiplatelet treatment for one year results in a 6.6% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes—or a number needed to treat of 15.

Recommendations: unstable angina

Patients with suspected unstable angina should be treated with 75 mg of aspirin daily for 18 months (A)

After 18 months, patients with a history of unstable angina should be treated in accordance with the recommendation for stable angina (A)

Previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack

Statement: aspirin given to patients with a history of transient ischaemic attack or mild to moderate stroke lowers their risk of a subsequent vascular event (Ia)

Within this area of investigation there are 19 trials, showing an overall risk reduction of 4.3% (2.8% to 5.8%).6,55–83 The pooled incidence rate difference, shown by random effects model, estimates that antiplatelet treatment for one year brings a 1.4% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes—or a number needed to treat of 69.

Recommendations: previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack

Patients with a history of a stroke or transient ischaemic attack should be treated with 75 mg of aspirin daily for four years (A)

Computed tomography is unnecessary before starting treatment in these patients (D)

After four years, aspirin should be continued long term at a dose of 75 mg daily (D)

Intermittent claudication

Statement: aspirin given to patients with intermittent claudication seems to have a small and statistically uncertain effect on the risk of a vascular event (Ia)

Substantial evidence from 23 randomised trials shows that antiplatelet treatment for intermittent claudication is unlikely to have a beneficial effect on the subsequent incidence of non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and death from vascular causes.84–110 Overall, the risk difference in favour of treatment is 1.3% (−0.1% to 2.7%), a difference of borderline significance. The use of antiplatelet treatment in patients with intermittent claudication for reasons other than secondary prophylaxis of vascular events is discussed elsewhere.4,111

Recommendations: intermittent claudication

Patients with intermittent claudication who have additional indications of raised vascular risk should be treated in line with the recommendations for that indication (D)

There is insufficient evidence to support use prophylactic aspirin in patients with intermittent claudication but no additional vascular risk factors (A)

Diabetes

Statement: aspirin given to patients with diabetes seems to have a small and statistically uncertain effect on the risk of a vascular event (Ia)

Within this area of investigation there are eight trials.112–122 These show an overall estimate of risk difference of 1.2% (−0.9% to 3.3%), which is of uncertain significance. There is no evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect between these trials (Q=7.66, df=7, P=0.36). The pooled incidence rate difference, shown by random effects model, estimates that antiplatelet treatment for one year brings a non-significant reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from vascular causes of 0.3%—or a number needed to treat of 360.

Recommendations: diabetes

Diabetic patients with additional indications of a raised risk of vascular events should be treated in line with the recommendations for those indications (D)

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of prophylactic aspirin in patients with diabetes but no additional risk factors (A)

Safety and cost effectiveness of aspirin

Side effects and costs of aspirin

Statement: the benefits of using aspirin in the secondary prophylaxis of vascular disease considerably outweigh the attributable risks of gastrointestinal or cerebrovascular bleeding (Ib) Statement: the use of aspirin is likely to be cost saving or cost neutral (IV)

The dosages, cautions, contraindications, and side effects of aspirin as an antiplatelet drug are described in the British National Formulary, section 2.9.123 All guideline recommendations for treatment apply only in the absence of recognised cautions, contraindications, side effects, or interactions as documented in the latest version of the formulary.

The net value of aspirin to individual patients must balance the increased risk of haemorrhage against the reduced likelihood of a cardiovascular event. A recent review examined all trials listed in the antiplatelet trialists’ collaboration for information on toxicity.124 When patients receiving aspirin and placebo were compared, the pooled odds ratio for all forms of gastrointestinal bleeding was 2.0 (1.5 to 2.8) and for bleeding leading to hospital admission was 1.9 (1.1 to 3.1). Similarly, when these groups were compared for either peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal symptoms leading to withdrawal of treatment, the pooled odds ratios were 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) and 1.5 (1.1 to 1.9). The review found a consistent tendency of lower rates of adverse events in lower dose trials.

Two major trials in which a dosage of 75 mg aspirin daily was used have been reported.5,6 It is possible to project the major benefits and risks attributable to this treatment regimen, but estimates should be treated with caution, since the trials did not have enough power to measure adverse effects at conventional levels of statistical significance. Assuming 1000 person years of treatment, the following effects are attributable to 75 mg of aspirin daily:

• (1) Ten patients with stable angina will avoid vascular events (non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction or sudden death). However, one patient will have a fatal bleed, one will have a major non-fatal bleed, and one patient will experience a minor bleed (where “bleed” includes stroke and gastrointestinal haemorrhage).

• (2) Twenty nine patients who have previously had a transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke will avoid a vascular event (non-fatal or fatal stroke or other vascular death). However, six patients will have a serious bleed (possibly fatal) and eight patients will suffer less serious bleeds.

Economic aspects

We found no adequate cost-benefit analyses of aspirin as an antiplatelet drug. The cost of aspirin itself is negligible. Generic aspirin, in 75 mg dispersible tablets, costs approximately £1 per year to prescribe, although proprietary brands may cost 10-20 times more. From a health service perspective, the net cost includes the cost of aspirin, treatment for attributable adverse events, and savings from fewer vascular events. Patients with vascular disease tend to consult their general practitioner regularly, and any increase in consultation because of treatment with aspirin would probably be small. Since the reduction in vascular events exceeds considerably the attributable adverse events, and given the nature of the medical interventions for both, aspirin treatment probably results in a net cost saving to the health service. The balance of costs could shift adversely if it were necessary to provide expensive H2 agonists to ameliorate gastrointestinal symptoms in a number of patients. The trials reported above, however, do not indicate that this would be the case. Aspirin is probably cost saving or cost neutral, although formal cost calculation has not proved possible because of inadequate hospital cost data.

Recommendation: secondary prophylaxis of vascular disease

Use of aspirin in the secondary prophylaxis of vascular disease is cost effective (D)

Research needs

The following research needs were identified by the guideline development group during the preparation of this document:

• (1) Many of the trials of antiplatelet treatment were conducted before the introduction of other important treatments for some groups of patients with ischaemic heart disease (for example, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors for heart failure): all potential interactions between the actions of relevant drugs have not been explored.

• (2) Further research on the appropriate duration of treatment is required.

• (3) A formal evaluation of the cost effectiveness of aspirin and other antiplatelet agents is required.

• (4) Further trials are needed to examine the effect of 75 mg of aspirin daily in patients with intermittent claudication or diabetes as the only risk factor for vascular disease.

Appendix

The guideline development group comprises the following members, in addition to the authors: Mr Mark Campbell, prescribing manager, Wolfson Unit of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Newcastle upon Tyne; Dr David Graham, general practitioner, Hexham; Dr Keith MacDermott, general practitioner, York; Dr Tony McKenna, general practitioner, Stockton-on-Tees; Dr Maureen Norrie, general practitioner, Eston, Middlesborough; Dr Colin Pollock, medical director, Wakefield Health Authority; Dr Helen Rogers, senior lecturer and consultant in stroke medicine, Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle; Dr Jeff Rudman, general practitioner, Distington.

The project steering group comprises: Professor Michael Drummond, Centre for Health Economics, University of York; Professor Andrew Haines, Department of Primary Care and Population Sciences, University College, London Medical School and Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine; Professor Ian Russell, Department of Health Sciences and Clinical Evaluation, University of York; Professor Tom Walley, Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Liverpool.

Table.

Diseases associated with a raised risk of vascular events—incidence, prevalence, and workload in a general practice, assuming a list size of 2000 patients

| Clinical condition | Classification category* | Incidence (new patients/GP/year) | Prevalence (patients consulting/GP/year) | Workload (condition related consultations/GP/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction | Acute myocardial infarction | 4.6 | 5.8 | 10.6 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | Old myocardial infarction | 1.0 | 6.0 | 2.2 |

| Unstable or stable angina | Angina pectoris | 10.4 | 22.8 | 52.8 |

| Transient ischaemic attack and prior stroke | Transient cerebral ischaemia | 5.0 | 6.0 | 9.4 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (intermittent claudication) | Other peripheral vascular disease | 4.8 | 8.0 | 14.2 |

| All conditions | 25.8 | 48.6 | 89.2 |

As morbidity statistics categories do not match the clinical groups exactly, classification details are presented.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for reviewing the full version of the draft guideline: Dr Phil Ayres, Dr Richard Baker, Professor Stuart Cobbe, Dr Chris Griffiths, and Dr Andrew Herxheimer. Janette Boynton, Julie Glanville, Susan Mottram, and Anne Burton are thanked for their contribution to the functioning of the guideline development group and the development of the practice guideline.

Footnotes

Funding: The work was funded by the Prescribing Research Initiative of the UK Department of Health.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.North of England Evidence Based Guidelines Development Project. Evidence based guideline for the use of aspirin for the secondary prophylaxis of vascular disease in primary care. Newcastle upon Tyne: Centre for Health Services Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick A, Fleming D, Charlton J. Morbidity statistics from general practice. Fourth national study 1991-1992. London: HMSO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles M, Freemantle N, Mason J. Methods of developing guidelines for efficient drug use in primary care. BMJ. 1998;316:1232–1235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet treatment. I. Prevention of death, myocardial infarction and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juul-Möller S, Edvardsson N, Jahnmatz B, Rosen A, Sorensen S, Ömblus R.for the Swedish Angina Pectoris Aspirin Trial Group. Double blind trial of aspirin in primary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with stable chronic angina pectoris Lancet 19923401421–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SALT Collaborative Group. Swedish aspirin low-dose trial (SALT) of 75 mg aspirin as secondary prophylaxis after cerebrovascular ischaemic events. Lancet. 1991;338:1345–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallentin LC for the Research Group on Instability in Coronary Artery Disease in Southeast Sweden. Aspirin (75 mg/day) after an episode of unstable coronary artery disease: long-term effects on the risk for myocardial infarction, occurrence of severe angina and the need for revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:1587–1593. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90489-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyman I, Larsson H Wallentin L for the Research Group on Instability in Coronary Artery Disease in Southeast Sweden (RISC) Prevention of serious cardiac events by low-dose aspirin in patients with silent myocardial ischaemia. Lancet. 1992;340:497–501. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91706-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet. 1988;ii:349–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmanis G, Vesterqvist O, Green K, Edhag O, Henriksson P. Effects of intermittent treatment with aspirin on thromboxane and prostacyclin formation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;ii:245–247. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjerre Knudsen J, Kjøller E, Skagen K, Gormsen J. The effect of ticlopidine on platelet functions in acute myocardial infarction., A double blind controlled trial. Thromb Haemost. 1985;53:3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funke Küpper AJ, Verheugt FWA, Jaarsma W, Roos JP. Proceedings of the X world congress on cardiology, Washington, DC, 1986. Failure of sulphinpyrazone to prevent left ventricular thrombosis in patients with AMI treated with oral anticoagulants; p. 419. . (Abstract 2414.) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funke Küpper AJ, Verheugt FWA, Peels CH, Galema TW. Effect of low dose acetyl salicylic acid on the frequency and hematologic activity of left ventricular thrombus in anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:917–920. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verheugt FWA, Funke Küpper AJ, Galema TW, Roos JP. Low dose aspirin after early thrombolysis in anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:904–906. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verheugt FWA, van-der-Laarse A, Funke Küpper AJ, Sterkman LGW, Galema TW, Roos JP. Effects of early intervention with low-dose aspirin (100 mg) on infarct size, reinfarction and mortality in anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:267–270. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90833-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gent AK, Brook CG, Foley TH, Miller TN. Dipyridamole: a controlled trial of its effect in acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1968;iv:366–368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5627.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones EW. Nottingham: University of Nottingham; 1985. A study of dazoxiben in the prevention of venous thrombosis after suspected myocardial infarction [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brochier ML.for the Flurbiprofen French Trial. Evaluation of flurbiprofen for prevention of reinfarction and re-occlusion after successful thrombolysis or angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction Eur Heart J 199314951–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ISIS Pilot Study Investigators. Randomized factorial trial of high-dose intravenous streptokinase, of oral aspirin and of intravenous heparin in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:634–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baigent C, Collins R. ISIS-2: 4 year mortality follow up of 17,187 patients after fibrinolytic and antiplatelet therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993;88:1–291. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentile R, Lagana B, Calcagni S. Proceedings of the X world congress on cardiology, Washington, DC, 1986. Borgia MC, Baratta L. Efficacy of platelet inhibiting agents in the prevention of reinfarction in smoker patients; p. 302. . (Abstract 1724) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breddin K, Loew D, Lechner K, Uberla KK, Walter E.on behalf of the German-Austrian Myocardial Infarction (GAMIS) Study Group. The German-Austrian aspirin trial: a comparison of acetylsalicylic acid, placebo and phenprocoumon in secondary prevention of myocardial infarction Circulation 198062(suppl V)63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anturane Reinfarction Italian Study (ARIS) Research Group. Sulphinpyrazone in post- myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1982;i:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elwood PC, Cochrane AL, Burr MI, Sweetnam PM, Williams GH, Welsby E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of mortality from myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1974;i:436–440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5905.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elwood PC. Trial of acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of mortality from myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1981;282:481. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6262.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persantine-Aspirin Reinfarction Study (PARIS) Research Group. Persantine and aspirin in coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1980;62:449–461. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persantine-Aspirin Reinfarction Study (PARIS) Research Group. The persantine-aspirin reinfarction study. Circulation 1980;62 (suppl V):V85-8. [PubMed]

- 28.Vogel G, Fischer C, Huyke R. Prevention of reinfarction with acetylsalicylic acid. In: Breddin HK, Loew D, Uberla K, Dorndoff W, Marx R, editors. Prophylaxis of venous peripheral cardiac and cerebral vascular diseases with acetylsalicylic acid. Stuttgart: Shattauer; 1981. pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel G. Fischer C, Huyke R. Reinfarktprophylaxe mit Acetylsalizylsäure. Folia Haematol (Leipz) 1979;106:797–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coronary Drug Project (CDP) Research Group. Aspirin in coronary heart disease. J Chronic Dis. 1976;29:625–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coronary Drug Project (CDP) Research Group. Aspirin in coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1980;62(suppl V):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coronary Drug Project (CDP) Research Group. The coronary drug project: design, methods and baseline results. Circulation. 1973;47(suppl 1):149. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.3s1.i-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anturane Reinfarction Trial (ART) Research Group. Sulfinpyrazone in the prevention of sudden death after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:250–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001313020502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anturane Reinfarction Trial (ART) Research Group. The anturane reinfarction trial: re-evaluation of outcome. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1005–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204223061640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherry S. The anturane reinfarction trial. Circulation. 1980;62(suppl V):73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temple BA, Pledger GW. The FDA’s critique of the anturane reinfarction trial. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1488–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012183032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elwood PC, Sweetnam PM. Aspirin and secondary mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1979;ii:1313–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elwood PC, Sweetnam PM. Aspirin and secondary mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1980;62(suppl V):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klimt CR, Knatterud GL, Stamler J, Meier P. Persantine-aspirin reinfarction study. Part II. Secondary coronary prevention with persantine and aspirin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:251–269. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aspirin Myocardial Infarction Study (AMIS) Research Group. AMIS: a randomized controlled trial of aspirin in persons recovered from myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1980;243:661–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker MC. Angina pectoris: a double blind study with dipyridamole. J Newark Beth Israel Hospital. 1967;18:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berglund U, Lassvik C, Wallentin I. Effects of the platelet inhibitor ticlopidine on exercise tolerance in stable angina pectoris. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:25–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berglund U, von Schenck H, Wallentin I. Effects of the platelet inhibitor ticlopidine on platelet function in men with stable angina pectoris. Thromb Haemost. 1985;54:808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wirecki M. Treatment of angina pectoris with dipyridamole: a long-term double blind study. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shar S, Schlant RC. Dipyridamole in the treatment of angina pectoris. JAMA. 1967;201:865–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chesebro JH, Webster MW, Smith HC, Frye RI, Holmes DR, Reeder GS, et al. Antiplatelet therapy in coronary disease progression: reduced infarction and new lesion formation. Circulation. 1989;80(suppl II):266. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis HD.for the Veterans Administration Co-operative Study Group. Unstable angina: status of aspirin and other forms of therapy Circulation 198572(suppl V)155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ALDUSA (aspirin at low dose in unstable angina) pilot study. Report from the coordinating center. Lyon: Unite de Pharmacologie Clinique; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aspirin Myocardial Infarction Study (AMIS) Research Group. AMIS: the aspirin myocardial infarction study: final results. Circulation. 1980;62(suppl V):79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prandoni P, Milani L, Barbiero M, Cardaioli P, Sanson A, Barbaresi F, et al. A combination of dipyridamole with low-dose aspirin in the treatment of unstable angina. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1991;39:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cairns JA, Gent M, Singer J. Finnie KJ, Froggatt GM, Holder DA, et al. Aspirin, sulfinpyrazone, or both in unstable angina. Results of a Canadian multicentre trial. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1369–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511283132201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balsano F, Rizzon P, Violi F, Scrutinio D, Cimmkiniello C, Aguglia F, et al. for the Studio della Ticlopidina nell’Angina Instabile Group. Antiplatelet treatment with ticlopidine in unstable angina: a controlled multicentre clinical trial Circulation 19908217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scrutinio D, Lagioia R, Rizzon P.on behalf of Studio della Ticlopidina nell’Angina Instabile Group. Ticlopidine treatment for patients with unstable angina at rest. A further analysis of the study of ticlopidine in unstable angina Eur Heart J 199112(suppl G)27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis HD, Davis JW, Archibald DG, Steinke WE, Smitherman TC, Doherty J, et al. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. Results of a Veterans’ Administration co-operative study. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:396–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308183090703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ross Russell RW. The effect of ticlopidine in patients with amaurosis fugax. Guildford: Sanofi Winthrop; 1985. (Sanofi internal report 105062/0051.) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gawel M, Rose FC. Use of sulphinpyrazone in the prevention of restroke and stroke in man. In: Rose FC, editor. Advances in stroke therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1982. p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reuther R, Dorndorf W, Loew D. Behandlung Transitorisch-ischamer Attacker mit Acetylsalicylsäure. Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1980;122:795–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reuther R. Dorndorf W. Aspirin in patients with cerebral ischaemia and normal angiograms or nonsurgical lesions. In: Breddin K, Dorndorf W, Loew D, Marx R, editors. Acetylsalicylic acid in cerebral ischaemia and coronary heart disease. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 1978. pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roden S, Low-Beer T, Carmalt M, Cockel R, Green I. Transient cerebral ischaemic attacks—management and prognosis. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:275–278. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.57.667.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robertson JT, Dugdale M, Salky N, Robinson H. The effect of a platelet inhibiting drug (sulfinpyrazone) in the therapy of patients with transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) and minor strokes. Thrombosis et Diathesis Haemorrhagica. 1975;34:598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Acheson J, Danta G, Hutchinson EC. Controlled trial of dipyridamole in cerebral vascular disease. BMJ. 1969;i:614–615. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5644.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Acheson J, Danta G, Hutchinson EC. Platelet adhesiveness in patients with cerebral vascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 1972;15:123–127. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(72)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sorensen PS, Pedersen H, Marquardsen J, Petersson H, Heltberg A, Simonsen N, et al. Acetylsalicylic acid in the prevention of stroke in patients with reversible cerebral ischaemic attacks. A Danish co-operative study. Stroke. 1983;14:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blakely JA. A prospective trial of sulfinpyrazone and survival after thrombotic stroke. Proceedings of VII international congress on thrombosis and haemostasis, 1979:161. (Abstract 42.)

- 65.Boysen G, Soelberg-Sørensen P, Juhler M, Andersen AR, Boas J. Olsen JS, et al. Danish very-low-dose aspirin after carotid endarterectomy trial. Stroke. 1988;19:1211–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fields WS, Lemak NA, Frankowski RF, Hardy RJ. Controlled trial of aspirin in cerebral ischaemia. Stroke. 1977;8:301–314. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fields WS, Lemak NA, Frankowski RF, Hardy RJ. Controlled trial of aspirin in cerebral ischaemia. Part II. Surgical group. Stroke. 1978;9:309–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.9.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lemak NA, Fields WS, Frankowski RF, Hardy RJ. Controlled trial of aspirin in cerebral ischaemia: an addendum. Neurology. 1986;36:705–710. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guiraud-Chaumeil B, Rascol A, David J, Boneu B, Clanet M, Bierme R. Prevention des récidives des accidents vasculaires cérébraux ischemiques par les anti-agrégants plaquettaires. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1982;138:367–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rascol A, Guiraud-Chaumeil B, Boneu B, David J, Clanet M. A long-term randomized trial of antiaggregating drugs in threatened stroke. In: Rose FC, editor. Advances in stroke therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1982. pp. 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canadian Co-operative Study Group. A randomized trial of aspirin and sulfinpyrazone in threatened stroke. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:53–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197807132990201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gent M, Barnett JHM, Sackett DL, Taylor DW. A randomized trial of aspirin and sulfinpyrazone in patients with threatened stroke. Results and methodologic issues. Circulation. 1980;62(suppl V):97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whisnant JP, Matsumoto N, Elveback LR. The Canadian trial of aspirin and sulphinpyrazone in threatened stroke. Am Heart J. 1980;99:129–130. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(80)90323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gent M, Blakely JA, Hachinski V, Roberts RS, Barnett HJM, Bayer NH, et al. A secondary prevention randomized trial of suloctidil in patients with a recent history of thromboembolic stroke. Stroke. 1985;16:416–424. doi: 10.1161/01.str.16.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Britton M, Helmers C, Samuelsson K. High-dose acetylsalicylic acid after cerebral infarction—a Swedish co-operative study. Stroke. 1987;18:325–334. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bousser MG, Eschwege E, Haguenau M, Lefauconnier JM, Thibult N, Touboul D, et al. AICLA controlled trial of aspirin and dipyridamole in the secondary prevention of athero- thrombotic cerebral ischaemia. Stroke. 1983;14:5–14. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bousser MG, Eschwege E, Haguenau M, Lefauconnier JM, Thibult N, Touboul D, et al. Essai coopératif contrôlé de prévention secondaire des accidents ischémiques cérébraux liés à athérosclérose par l’aspirine et le dipyridamole. Presse Med. 1983;12:3049–3057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gent M, Blakely JA, Easton JD, Ellis DJ, Hachinski VC, Harbison JW, et al. The Canadian American ticlopidine study (CATS) in thromboembolic stroke. Stroke. 1988;19:1203–1210. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.10.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gent M, Easton JD, Hachinski VC, Panak E, Sicurella J. Blakely JA, et al. The Canadian American ticlopidine study (CATS) in thromboembolic stroke. Lancet. 1989;i:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.UK-TIA Study Group. United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TM) aspirin trial: interim results. BMJ. 1988;296:316–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.UK-TIA Study Group. United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TM) aspirin trial: final results. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:1044–1054. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.12.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.ESPS Group. The European stroke prevention study (ESPS). Principal endpoints. Lancet. 1987;ii:1351–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.ESPS Group. The European stroke prevention study (ESPS) Stroke. 1990;21:122–130. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.8.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bourde C, Eschwege E, Verry M. Controlled clinical trial of an antiaggregating agent, ticlopidine, in vascular ulcers of the leg. Thomb Haemost. 1981;46:91. . (Abstract 0271.) [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bourde C, Giraud D. Correlations cliniques et téléthermographiques dans les ulcères de jambes d’origine vasculaire traités par un anti-aggrégant plaquettaire: la ticlopidine. J Mal Vasc. 1982;4:31. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stuart J, Aukland A, Hurlow RA, George AJ, Davies AJ. Ticlopidine in peripheral vascular disease. Proceedings of VI international congress of the Mediterranean League Against Thrombosism 1980:75-87. (Abstract 73.)

- 87.Adriansen H. Medical treatment of intermittent claudication: a comparative double-blind study of suloctidil, dihydroergotoxine, and placebo. Curr Med Res Opin. 1976;4:395–401. doi: 10.1185/03007997609111994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shaw K. Assessment of the effect of ticlopidine on diabetic pre-gangrene. Guildford: Sanofi Winthrop; 1983. (Sanofi internal report 001.6.241.) [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jones NAG, De Haas H, Zahavi J, Kakkar VV. A double blind trial of suloctidil v placebo in intermittent claudication. Br J Surg. 1982;69:38–40. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krause D. Double blind study—ticlopidine versus placebo—in intermittent claudication. Guildford: Sanofi Winthrop; 1983. (Sanofi internal report 001.6.170.) [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holm J, Lindblad L, Schersten T, Sunrkula M. Intermittent claudication: suloctidil vs placebo treatment. Vasa. 1984;13:175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verhaeghe R, Van Hoof A, Beyens G. Controlled trial of suloctidil in intermittent claudication. J Cardivasc Pharmacol. 1981;3:279–286. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Signorini GP, Salmistraro G, Maraglino G. Efficacy of indobufen in the treatment of intermittent claudication. Angiology. 1988;39:742–745. doi: 10.1177/000331978803900806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aukland A, Hurlow RA, George AJ, Stuart J. Platelet inhibition with ticlopidine in atherosclerotic intermittent claudication. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:740–743. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.7.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hess H, Keil-Kuri E. Proceedings of the colfarit symposion III. Cologne, 1975. Theoretische grundlagen der Prophylaxe Obliterinerender Arteriopathien mit Aggregationshemmern und Ergebnisse einer Langzeitstudie mit ASS (Colfarit) pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stiegler H, Hess H, Mietaschk A, Trampisch HJ, Ingrisch H. Einfluss von Ticlopidin auf die Periphere Obliterierende Arteriophie. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1984;109:1240–1243. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1069356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cloarec M, Caillard P, Mouren X. Double blind clinical trial of ticlopidine versus placebo in peripheral atherosclerotic disease of the legs. Thromb Res 1986;suppl VI:160.

- 98.Balsano F, Coccheri S, Libretti A, Nenci GG, Catalano M, Fortunato G, et al. Ticlopidine in the treatment of intermittent claudication: a 21-month double blind trial. J Lab Clin Med. 1989;114:84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Arcan JC, Blanchard J, Boissel JP, Destors JM, Panak E. Multicentre double blind study of ticlopidine in the treatment of intermittent claudication and the prevention of its complications. Angiology. 1988;39:802–811. doi: 10.1177/000331978803900904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Destors JM, Arcan JC. Evaluation des médicaments par voie orale de la claudication intermittente des membres inférieurs à la phase III des essais cliniques. Choix retenus dans l’étude ACT. Thérapie. 1985;40:451–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Katsumura T, Mishima Y, Kamiya K, Sakaguchi S, Tanabe T, Sakuma A. Therapeutic effect of ticlopidine, a new inhibitor of platelet aggregation, on chronic arterial occlusive diseases, a double blind study versus placebo. Angiology. 1982;33:357–367. doi: 10.1177/000331978203300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ellis DJ. Treatment of intermittent claudication with ticlopidine. In: Proceedings of International Committee on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 32nd Meeting, 1986:63:60. (Abstract addendum.)

- 103.Hess H, Mietaschk A, Deichsel G. Drug-induced inhibition of platelet function delays progression of peripheral occlusive arterial disease. A prospective double-blind arteriographically controlled trial. Lancet. 1985;i:415–419. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Colwell JA, Bingham SF, Abraira C, Anderson JW, Kwaan HC, et al. for the Co-operative Study Group. VA co-operative study on antiplatelet agents in diabetic patients after amputation for gangrene: I. Design, methods and baseline characteristics Controlled Clin Trials 19845165–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Colwell JA, Bingham SF, Abraira C, Anderson JW, Comstock JP, Kwaan HC, et al. Veterans Administration co-operative study on antiplatelet agents in diabetic patients after amputation for gangrene: II. Effects of aspirin and dipyridamole on atherosclerotic vascular disease rates. Diabetes Care. 1986;9:140–148. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schoop W, Levy H, Schoop B, Gaentzsch A. Experimentelle und Klinische Studien zu der sekundaren Prevention der Peripheren Arteriosklerose. In: Bollinger A, Rhyner K, editors. Thrombozytenfunktionshemmer, Wirkungsmechanismen, Dosierung und Praktische. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1983. pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schoop W. Levy H. Prevention of peripheral arterial occlusive disease with antiagreggants. Thromb Haemost. 1983;50:137. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schoop W. Spatergebnisse bei Konservitiver Therapie der Arteriellen Verschlusskrankheit. Der Internist. 1984;25:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Janzon L, Berqvist D, Boberg J. Boberg M, Eriksson I, Lindgarde F, et al. Prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke in patients with intermittent claudication, effects of ticlopidine. Results from STIMS, the Swedish ticlopidine multicentre study. J Intern Med. 1990;227:301–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Balsano F. Violi F. and ADEP Group. Effect of picotamide on the clinical progression of peripheral vascular disease. A double blind placebo controlled study. Circulation. 1993;87:1563–1569. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moher M, Lancaster T. Who needs antiplatelet therapy? Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:367–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pollock A, Wright AD. The effect of ticlopidine on platelet function in patients with diabetic peripheral arterial disease. Guildford: Sanofi Winthrop; 1979. (Sanofi internal report 105062/0019.) [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nyberg G, Larsson O, Westberg NG, Aurell M, Jagenburg R, Blohme G. A platelet aggregation inhibitor—ticlopidine—in diabetic nephropathy: a randomized double blind study. Clin Nephrol. 1984;21:184–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pannebakker MAUI, Jonker JJC, Den Ottolander GJH. Influence of sulphinpyrazone on diabetic vascular complications. In: Proceedings of VI international congress of Mediterranean League Against Thrombosis. Monte Carlo, 1980. (Abstract 167.)

- 115.Oakley NW, Dormandy JA, Flute PT. Investigation of the effect of ticlopidine in the incidence of cardiovascular events in selected high risk patients with diabetes. Guildford: Sanofi Winthrop; 1983. (Sanofi internal report 105062/0019.) [Google Scholar]

- 116.Belgian Ticlopidine Retinopathy Study Group (BTRS) Clinical study of ticlopidine in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 1992;204:4–12. doi: 10.1159/000310259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.DAMAD Study Group. Effect of aspirin alone and aspirin plus dipyridamole in early diabetic retinopathy—a multi-centre randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes. 1989;38:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mirouze J.on behalf of TIMAD Study Group. Ticlopidine in the secondary prevention of early diabetes-related microangiopathy: protocol of a multicentre therapeutic study (TIMAD study) Agents Actions 198415(suppl)230–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.ETDRS Investigators. Aspirin effects on mortality and morbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus. Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study report 14. JAMA. 1992;268:1292–1300. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490100090033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.ETDRS Research Group. Effects of aspirin treatment on diabetic retinopathy: ETDRS report number 8. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(suppl):757–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Breddin K, Loew D, Lechner K, Uberla KK, Walter E. Secondary prevention of myocardial infarction: a comparison of acetylsalicylic acid, placebo and phenprocoumon. Haemostasis. 1980;9:325–344. doi: 10.1159/000214375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Uberla K. Multicentre two year prospective study on the prevention of secondary myocardial infarction by ASA in comparison with phenprocoumon and placebo. In: Breddin K, editor. Acetylsalicylic acid in cerebral ischaemia and coronary heart disease. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 1978. pp. 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 123.British National Formulary. No 32. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Roderick PJ, Wilkes HC, Meade TW. The gastrointestinal toxicity of aspirin: an overview of randomised controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb05689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]