The challenge of meeting the demand for public services that are free at the point of use is increasing. Examples, in increasing order of complexity and controversy, include water, higher education, road space, and health care. These services are perceived as important to society in general, and demand is rising rapidly and unsustainably.

Such increases in demand can be managed either by reducing the demand—for example, by charging, as for water or road space—or by increasing the supply—for example, via increased funding, as with student loans. In health care, perversely, we do the opposite of both these approaches: we fuel demand by failing to manage it—for example, by not curbing expectations—and we are often forced to cut supply through lack of resources.

Demand for health care is undoubtedly rising. The average number of consultations for children in each of the first years of life (even after excluding surveillance and immunisations) has, in one general practice, risen from 3.73 per child in 1960 to 17.2 in 1990.1 We need to understand better how this ever increasing demand for health care is initiated and expressed and use this understanding to manage the whole system better. Professionals have the same increasing expectations from the service as the public does. Managing the pressure on the health service is as much about managing the expectations and rights of professionals to treat as it is about managing the expectations of patients to be treated.

Summary points

Demand management is about moving from merely struggling to meet the increasing demand for health services to shaping this demand so that health needs of individuals and populations are best served with the available resources

Managing demand does not only mean reducing it: where cost effective health care is underused, demand may need to be encouraged

The potential exists to develop more graduated access to health care

One important way of managing demand is to supply and clarify simple knowledge and advice

It may be possible to meet demand in different ways

Opportunities and incentives need to be provided for people to meet their perceived needs in ways that supplement formal health care

To many, managing demand for health care sounds like a euphemism for rationing via restricting supply. However, it is a broader approach: the consumption of any product or service is determined by the relation between supply and demand, and different tools are used to influence supply and demand. Historically, supply management has been the most potent tool in coping with the challenges in health care. In the past 15 years this has been supplemented by processes for assessing need.2 We now need to add demand management to these approaches.

What is demand management?

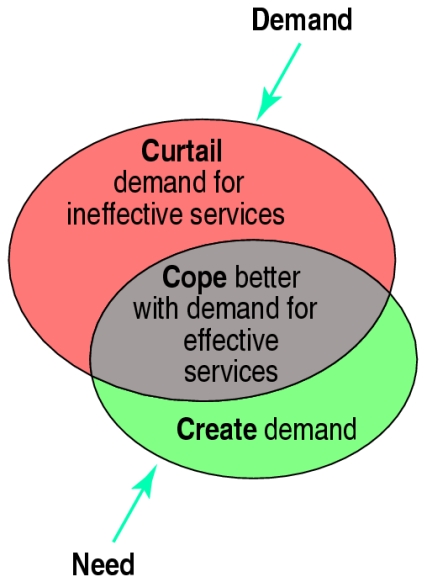

Demand management is the process of identifying where, how, why, and by whom demand for health care is made and then deciding on the best methods of managing this demand (which might mean curtailing, coping, or creating demand) such that the most cost effective, appropriate, and equitable health care system can be developed. Critically, it depends on understanding how the behaviour of those who express the demand—citizens and professionals—is changing. It is concerned with making more appropriate use of the health services (not necessarily reducing it or making it cheaper). More specifically, demand management “is the support of individuals so that they may make rational health and medical decisions based on a consideration of benefits and risks.”3 This definition comes from North America, where managing demand is an established discipline.

The many causes of a demand for health care need a variety of responses. For instance, some pressures may be best met, not by curtailing demand but by coping with it and meeting it in a radically different way. Recent examples include the use of helplines as a first point of access to health care in the home.4 The assumption that better informed people demand ever more health care may be unfounded. Studies of interactive information sources that allow patients to understand the advantages and disadvantages of prostate surgery show that increased information may persuade some people to avoid surgery.5 In a country with relatively high activity levels, such as America, this has been shown to reduce activity by up to 40%. In countries with lower activity rates it is not clear that the proportionate decrease would be the same,6 although it is important to find out.

Where is demand expressed?

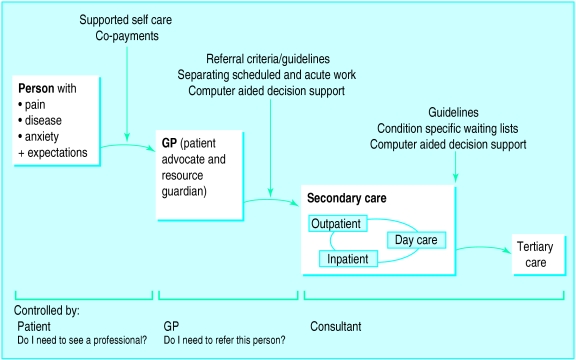

The figure shows the way in which people travel through the healthcare system. Most healthcare needs are met without recourse to formal healthcare services, so a vital part of demand management is supporting this self care. Similarly, most problems presented to primary care are dealt with without referral. Again, efforts to manage demand at this stage will be most rewarded. At the interfaces between successive parts of the system important decisions are made about how the expressed demand might be best met.

Traditional reasons for increasing demand

Cultural and behavioural (a much larger, informed and demanding middle class—consumerism, where the concept of rights is outpacing that of responsibility)

Technological (specifically information technology and health technology)

Epidemiological (long term care is now increasingly common relative to short term cure)

Ultimately, the best place to manage demand is before it meets the service—that is, through promoting self care. This needs more than simply exhortations not to use the service for minor complaints, but meaningful education and true empowerment of individuals, households, schools, and workplaces so we feel more competent and confident to meet simple health-care needs ourselves. This involves a bigger investment in advice lines, nurse practitioners, and self care manuals, and the continued enhancement of the roles of pharmacists and other health care professionals. NHS Direct, as proposed in the recent white paper on the NHS in England, has much to offer.4

Self care

—In helping people make more appropriate decisions about their own health we must not compromise safety but instead explicitly share risk. This involves assessing the best content and format of information in self-care manuals that integrate consistently with the advice from health care professionals over the telephone or other forms of technology. There is much to be learnt from the experience of health maintenance organisations in America, many of whom issue comprehensive manuals and free phone numbers on enrolment. Importantly, a high degree of consistency exists between the advice in the manuals and from the professionals.

Primary care

—In primary care general practitioners need to be supported to manage demand more extensively. Gatekeeping (more recently and appropriately called filtering) can be done much more successfully if primary care is supported with more knowledge sharing, more risk sharing, and a more graduated access from primary care to secondary care (or other statutory and voluntary services) (see boxes).

More graduated access from self to primary care

11 pm: 10 year old with sudden high fever and rash

Choices for parent:

| Traditional method | Developing methods |

| Ask family/friend | Ask family/friend |

| Call GP to come and visit | Consult self care manual |

The power of knowledge

The knowledge that underpins primary care (and the way it is used) is essential in managing demand. This can be divided into the fears, understanding, and expectations of the patient; the evidence from valid, relevant, and accessible research knowledge; and an up to date knowledge about the facilities and support available from fellow healthcare professionals (especially in secondary care). Access to research knowledge has been undergoing most change recently and has the potential to help manage demand more rationally and consistently. Knowledge sources for both professionals and the public need to change from being there “just in case” to being there “just in time.”

More graduated access from primary to secondary care

7 pm Friday: 74 year old man (living with wife) had funny turn, gone off legs

Choices for visiting general practitioner from the local cooperative:

| Traditional method | Developing methods |

| GP calls SHO on call | GP consults pocket decision support tool |

| SHO: “Send him in...” | GP phones hospital support service |

| Ambulance arrives | Hospital support service advises “Watchful waiting” and shares the risk |

| Patient arrives at hospital | Social services consulted by GP |

| Patient admitted | Telephone message to GP |

| Some weekend investigations | Midnight: paramedic drops in |

| Monday morning ward round | Night sitting service arranged |

| More investigations | Saturday morning visit from local nurse practitioner and social services |

| Wife can’t visit | Quick visit to hospital and back |

| Social support crumbles | Own GP visits |

| Challenging discharge |

Managing demand in secondary care and beyond needs another set of tools. Although fewer patients are seen than in primary care, many more resources are consumed. The ability to manage the pressure on the hospital’s front door is intimately related to the extent to which the healthcare professionals in the hospital are prepared to support colleagues in primary care. This support involves decision support, explicit knowledge on generalisable research (on effectiveness and cost effectiveness) and localised knowledge on availability, access, pre-referral support, and outreach services. It is important be able to be explicit about, and share the risk of, all decisions between the patient and the professionals (including the legal consequences9). For the general practitioner to refer and the physician to admit on increasingly smaller tolerances will cripple the system even more quickly. We need to be able explain and share risk between doctor and patient, between primary and secondary care. This implies having senior people on the front door, not only to manage acute illness quickly, but also to see the patient at the front door, and sometimes refer home again, as a practice acceptable to both patient and general practitioner. “If in doubt, admit” may become an unaffordable policy.

Practical ways of meeting the same needs

Coping with demand is about exploring better ways of meeting the same need—that is, increasing the efficiency and convenience of the system without compromising quality (see boxes).

Services can be offered...

| In a different place | Intermediate or primary care v secondary care, in the community v in hospital |

| In a different way | Drugs v surgery, watchful waiting v immediate intervention, reactive v proactive telephone v face to face |

| By different people | Self care, nurse practitioners, or pharmacists or citizens v doctors |

| At a different time | Sunday morning v Monday morning or vice versa |

| With different levels of shared responsibility between professional and public |

Creating demand may be an appropriate way of managing demand if there is a poor uptake of a preventive service—for example, breast screening—where early intervention would reduce the demand for alternative and less successful interventions later on. Examples of curtailing, coping and creating demand in heart disease are shown in the table.

Conclusion

We need to turn the consequence of the changing expectations in society into a fundamental part of the solution. We need to find the best ways of helping people make the most efficient and fair use of a service that will never have enough resources to do everything. Understanding of the ways of managing demand is in its infancy, though there is some evidence on their effectiveness. The remaining four articles in this series will explore the practical opportunities for demand management: before primary care, within primary care, between primary and secondary care, and within and beyond secondary care—in each case evaluating the available evidence.

Figure.

Boundaries in the healthcare system where demand is generated and examples of tools used to manage that demand

Table.

Example: of curtailing, coping, and creating demand

| Demand | Heart disease |

|---|---|

| Curtail | Disseminate information on the most cost effective interventions for preventing, diagnosing, and treating coronary heart disease |

| Cope | Prioritise cases for ambulance and early treatment with explicit triage criteria Ensure thrombolysis for all suitable patients is given within target time |

| Create | Ensure through public education that people recognise: • the symptoms of a heart attack • the importance of early treatment |

Acknowledgments

With particular thanks to Philip Hadridge.

References

- 1.Del Mar AR. Recorded consultation for children under 5 have increased considerably in general practice. BMJ. 1996;313:1334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7068.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens A, Gabbay J. Needs assessment needs assessment. Health Trends. 1991;23:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vickery DM, Lynch WD. Demand management: enabling patients to use medical care appropriately. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37:551–557. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pencheon D. NHS Direct: managing demand. BMJ. 1998;316:215–216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7126.215a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, Mulley AG, Jr, Henderson JV, Jr, Wennberg JE. Patient reactions to a program designed to facilitate patient participation in treatment decisions for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Care. 1995;33:771–782. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199508000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulter A. Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 1997;2:112–121. doi: 10.1177/135581969700200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ovretveit JA. Managing the gap between demand and publicly affordable health care in an ethical way. Eur J Pub health. 1997;7:128–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, Warner G, Gantley M, Kinmonth AL. Reattendance and complications in a randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ. 1997;315:350–352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7104.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peysner J. Boiled frogs and distant sails. Journal of the Medical and Dental Defence Unions. 1996;12:4. [Google Scholar]