General practitioners have acted as official gatekeepers to the United Kingdom hospital service since the inception of the NHS in 1948, but the roots of the referral system can be traced to the conflict between physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries in the 15th and 16th centuries.1 Specialists and general practitioners had to compete for paying patients until the early 20th century, when the issue was resolved with the establishment of registered general practice lists, a salaried hospital service, and a formal system of referral from one to the other. The gatekeeping role (more recently called filtering) of general practitioners is arguably the most important mechanism for managing demand in the NHS. The British referral system undoubtedly contributes to the low cost of health care relative to other countries. Healthcare systems which allow patients direct access to specialists—America, Germany, France, and Sweden—tend to incur higher costs than those that channel demand via general practitioner referrals, such as Britain, Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands.2 At its best the referral system ensures that most care is contained within general practice, and when specialist care is needed patients are directed to the most appropriate specialist. However, it is also a restrictive practice, initially introduced to protect the interests of doctors, which gives general practitioners a monopoly over primary medical care and restricts patients’ freedom of choice. Despite this the system has survived relatively unscathed by public criticism, a tribute to the widespread public confidence in general practitioners and to the fact that the gatekeepers have been very willing to open the gates to secondary care in response to patient demand.

Variations in referral rates

Evidence of wide variations in the rates at which general practitioners referred patients to specialist clinics began to emerge in the 1970s.3 Later studies using more sophisticated techniques of data collection and analysis confirmed the early impression that rates were variable but failed to identify any factors that could explain the major sources of variation.4 Referral rates increased steadily in line with increased consultation rates in general practice5; on average general practitioners make about 5 outpatient referrals per 100 consultations (12 referrals/100 registered patients) per year. Rates vary between individual general practitioners within practices and between practices. Estimates of the extent of variation between individual general practitioners are hard to calculate because of the difficulty in establishing a correct denominator, but it is fairly well established that rates vary between practices by at least threefold or fourfold.4

These large unexplained variations are disturbing to policymakers because they suggest inefficiencies, and few incentives seemed to exist for general practitioners to avoid referral. Some considered that many referrals were avoidable and that if a way could be found to curb the activities of the high referrers it would lead to greater efficiency.6 However, practices’ outpatient referral rates have been found to be strongly correlated with elective inpatient admission rates for their patients, which are equally variable.7 The finding that high referring practices also had high admission rates cast doubt on the view that these practices were referring many patients unnecessarily, since specialists appeared to be concurring with general practitioners’ judgements by admitting their patients to hospital in similar proportions.

Achieving a shift in the balance from secondary to primary care has been a central focus of recent policy initiatives and various attempts have been made to modify general practitioners’ referral behaviour (see box).

Strategies for managing demand at the interface

| Information and audit: | Feedback of referral rates |

| Decision support: | Measuring outcomes |

| Financial incentives: | Guidelines |

Information and audit

The requirement for general practitioners to collect data on their referrals to hospital specialties and report these in their annual reports has recently been dropped. In theory these data can be obtained from provider units, but many problems exist in interpreting referral data collected in this way.8 Comparative information can be a spur to action, but hopes that feedback of information on referral rates would lead general practitioners to change their referral behaviour proved overoptimistic.9 General practitioners were sceptical of the data on which the feedback was based and because referral rates in themselves do not reveal anything very useful about the quality of care, it was difficult to persuade them to use information about aggregate rates as a basis for auditing their own hospital referrals.

Referral rates are unsatisfactory indicators of quality because they can hide failures to refer as well as unnecessary referrals. Patients may be harmed if referral occurs too late and delay can lead to more major treatment being required at a later stage. There are various reasons for referring patients to specialist outpatient clinics (see box on next page). The complex factors influencing referral decisions contribute to the difficulties in reaching agreement on what is an appropriate rate of referral (see box on last page).

These criteria are hard to measure and routine data cannot provide answers. General practitioners, consultants, and patients often disagree about the purpose of referrals and differ in their assessments of appropriateness.10 Despite a widespread assumption that high referring general practitioners tend to refer unnecessarily, studies comparing referrals from high and low referring doctors have not confirmed this.11,12

Reasons for referring

Diagnosis

Investigation

Advice on treatment

Specialist treatment

Second opinion

Reassurance for the patient

Sharing the load, or risk, of treating a difficult or demanding patient

Deterioration in general practitioner-patient relationship, leading to desire to involve someone else in managing the problem

Fear of litigation

Direct requests by patients or relatives

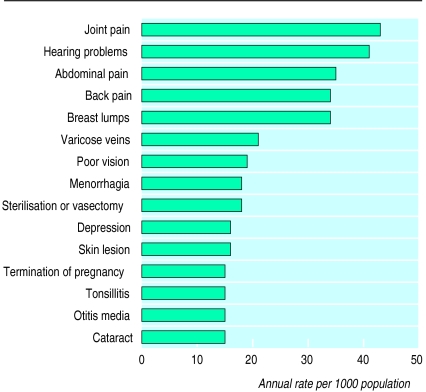

Despite the difficulties, collating and feeding back information about referral rates is an important first step in understanding patterns of demand for secondary care. Tracer studies to follow up patients referred with particular conditions or problems can also be illuminating,13 but ultimately the need is for referral decisions to be based on an understanding of the cost effectiveness of different forms of treatment and evidence on the most appropriate setting for these to be provided. It should be a priority to commission reviews and efficacy studies on treatment options for the conditions most commonly referred to specialists. The top 15 problems account for 28% of all outpatient referrals14 (see figure).

Decision support

Attempts to modify referral behaviour have usually relied on the development of clinical guidelines designed to assist decision making about when a referral is appropriate. Good evidence exists that guidelines can help change clinical behaviour, but they are likely to have an impact on practice only if they are agreed by those responsible for implementing them.15 The absence of evidence on the outcomes of referrals leads to widely differing opinions on when a referral is appropriate, which in turn makes it hard to achieve consensus on the need to implement referral guidelines. This type of local consensus development is difficult and time consuming, an activity for enthusiasts and therefore unlikely to have a major impact on the balance of care. Even if it were possible to eliminate referrals deemed to be inappropriate according to agreed guidelines, the effect on overall rates would probably be marginal at best.12

If achieving consensus among doctors is difficult, supporting shared decision making between doctor and patient may prove to be a more promising approach to managing demand at the interface. The development and use of information packages to allow patients to participate in decisions about their care is currently attracting interest. Research has shown that patients find it difficult to access the information they would like, that doctors consistently underestimate patients’ desire for information, and that many, but not all, patients want to play a more active role in decision making about their care.16

Evidence from America suggests that fears that better informed patients will demand more treatment may prove groundless. An interactive video which provides patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy with evidence based information about the treatment options reduced demand for prostatectomy among American patients17; and patients who were better informed about the risks and benefits of screening for prostate cancer were less likely to want the tests.18,19 In Britain, hysterectomy rates are strongly associated with educational level20: women with higher education, who tend to be more knowledgeable about treatment options, are much less likely to agree to hysterectomy than women without educational qualifications.21 Patients may turn out to be more risk averse than their doctors, so investing in decision support systems for patients may prove to be more cost effective than developing yet more clinical guidelines.

Financial incentives

The major thrust of government policy on primary care since 1989 has been the attempt to align clinical decisions and financial responsibility by providing incentives for general practitioners to provide more practice based services and by giving them the opportunity to manage secondary care budgets. In giving general practitioners financial incentives to perform minor operations, the government presumably hoped to remove some of the hospital workload. But evaluation of this policy showed no impact on the demand for hospital based minor surgery.22 Instead general practitioners’ willingness to perform these procedures seemed to encourage patients to come forward for treatment who would not otherwise have done so. The increased availability of equipment for near patient diagnostic testing in general practice has had a similarly disappointing impact, with investigation rates and costs continuing to increase.23 Simply increasing the supply of services in primary care is not enough to deliver the desired knock on effect on the demand for secondary care services.

Appropriate referrals are:

Necessary for the particular patient, in the light of presenting symptoms, age, previous treatment, etc.

Timely—neither too early nor too late in the course of the disease

Effective—the objectives of the referral are achieved

Cost effective—the benefits justify the costs

Fundholding brought the costs of prescribing, outpatient referrals, and elective admissions under the control of general practitioners for the first time, giving them a financial incentive to modify their behaviour. The effect on referrals was not dramatic: rates continued to rise in fundholding practices, although the increase was slightly less steep than in non-fundholding practices.24 Fundholders did use their financial leverage to achieve several beneficial changes, including investing in practice based services such as physiotherapy, counselling, and diagnostic equipment. They also negotiated direct access to many hospital diagnostic services, avoiding the need for specialist referral, but in general the effect has been to improve access for fundholders’ patients, rather than changing the pattern of provision or modifying the demand for specialist services.

Future developments

In announcing their intention to give primary care groups control of almost all of the budget for hospital and community health services (compared with the 20% controlled by fundholders), this government has adopted an even more radical approach to demand management.25 In theory both the incentive to deal with health problems within a primary care setting, and the scope to do so, will be much stronger. Larger primary care organisations covering populations of around 100 000 will contain a greater range of professional expertise, allowing for cross referral within the primary care group or trust, which may reduce the need for referrals to hospital based specialists. Unitary budget arrangements will encourage substitution of primary care services for secondary care. Eventually, primary care trusts may develop and run their own specialist services, thus blurring the boundaries between primary and secondary care. The role of the gatekeeper looks set to undergo a dramatic change.

Figure.

Top 15 problems referred to specialist outpatient clinics

References

- 1.Oswald N. The history and development of the referral system. In: Roland M, Coulter A, editors. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of General Practitioners; Office of Population Censuses and Surveys; Department of Health and Social Security. Morbidity statistics from general practice 1971-2. Second national survey. London: HMSO; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkin D. Patterns of referral: explaining variation. In: Roland M, Coulter A, editors. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Living in Britain: Results from the 1995 General Household Survey. London: Stationery Office; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secretaries of State for Health and Social Security, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland. Promoting better health: the government’s programme for improving primary health care. London: HMSO; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulter A, Seagroatt V, McPherson K. Relation between general practices’ outpatient referral rates and rates of elective admission to hospital. BMJ. 1990;301:273–276. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland M. Measuring referral rates. In: Roland M, Coulter A, editors. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Marco P, Dain C, Lockwood T, Roland M. How valuable is feedback of information on hospital referral patterns? BMJ. 1993;307:1465–1466. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6917.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grace JF, Armstrong D. Referral to hospital: perceptions of patients, general practitioners and consultants about necessity and suitability of referral. Family Practice. 1987;4:170–175. doi: 10.1093/fampra/4.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knottnerus JA, Joosten J, Daams J. Comparing the quality of referrals of general practitioners with high and average referral rates: an independent panel review. Br J General Pract. 1990;40:178–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fertig A, Roland M, King H, Moore T. Understanding variation in rates of referral among general practitioners: are inappropriate referrals important and would guidelines help to reduce rates? BMJ. 1993;307:1467–1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6917.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coulter A. Auditing referrals. In: Roland M, Coulter A, editors. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulter A. The interface between primary and secondary care. In: Roland M, Coulter A, editors. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Effective Health Care Bulletin No 8. Leeds: University of Leeds; 1994. Implementing clinical practice guidelines. . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulter A. Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1997;2:112–121. doi: 10.1177/135581969700200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Barrett P, Barry MJ, Barlow W, Fowler FJ. The effect of a shared decision-making program on rates of surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Care. 1995;33:765–770. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199508000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flood AB, Wennberg JE, Nease RF, Fowler FJ, Ding J, Hynes LM. The importance of patient preference in the decision to screen for prostate cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:342–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02600045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf AMD, Nasser JF, Wolf AM, Schorling JB. The impact of informed consent on patient interest in prostate-specific antigen screening. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1333–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuh D, Stirling S. Socioeconomic variation in admission for diseases of female genital system and breast in a national cohort aged 15-43. BMJ. 1995;311:840–843. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulter A, Peto V, Doll H. Patients’ preferences and general practitioners’ decisions in the treatment of menstrual disorders. Fam Pract. 1994;11:67–74. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowy A, Brazier J, Fall M, Thomas K, Jones N, Williams B. Minor surgery by general practitioners under the 1990 contract: effects on hospital workload. BMJ. 1993;307:413–417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6901.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rink E, Hilton S, Szczepura A, Fletcher J, Sibbald B, Davies C, et al. Impact of introducing near patient testing for standard investigations in general practice. BMJ. 1993;307:775–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6907.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surender R, Bradlow J, Coulter A, Doll H, Stewart-Brown S. Prospective study of trends in referral patterns in fundholding and non-fundholding practices in the Oxford region, 1990-4. BMJ. 1995;311:1205–1208. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7014.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Secretary of State for Health. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1998. (Cm 3807). [Google Scholar]