Developing countries have limited resources, so it is particularly important to invest in health care that works. The growing number of relevant systematic reviews can assist policymakers, clinicians, and consumers in making informed decisions. Developing countries have led the way in generating approaches to ensure professional standards of behaviour through interventions such as producing guidelines and introducing essential drug programmes, and by producing reliable research summaries to help ensure that policies are based on good evidence.

Summary points

Financial resources are limited in developing countries so it is vital that the health care provided is effective

The number of systematic reviews relevant to developing countries is increasing

Disseminating the findings of systematic reviews to policymakers, health professionals, and consumers is an essential prerequisite to changing practices

Practice guidelines and international programmes that provide essential drugs are well established and provide a powerful route for reinforcing evidence based practice

Large obstacles impede the implementation of evidence based practices, such as the unethical promotion of drugs; these problems need to be addressed by regulation

Action is required at all levels of healthcare systems, from consumers through to health professionals, ministries of health, and international organisations

Introduction

Yakamul, an illiterate villager in Papua New Guinea, was sitting by a fire listening to a health professional from the West tell her to take chloroquine throughout her pregnancy. She responded: “I ting merisin bilong ol wait man bai bagarapim mi [I think this Western medicine could harm me].” She had never attended a workshop in critical appraisal but she realised that medicine could do her more harm than good. Her response reminds health professionals to ask fundamental questions about the care we provide and of our responsibility to examine evidence using scientific methods. Eventually we tested Yakamul’s hypothesis about chloroquine treatment during pregnancy.1

Removing erroneous opinions from healthcare policy and practice is part of getting research findings into decision making. Practitioners work in good faith, but if they implement practices or policies that are ineffective they waste resources and may harm people. Nowhere is this consideration more important than in developing countries, in which many practitioners struggle to provide care on less than £7 per person each year.2 These countries do not have money to waste on a single treatment that is not effective. Equally important is the time and money that patients expend on their health care. If as health professionals we are providing care that is ineffective, then we are responsible for exacerbating patients’ deprivation and poverty.

Unfortunately, applying research findings to clinical decisions is not a simple process. Indeed, it is impossible if primary research asks questions that are irrelevant to the study participants. Tropical medicine has a long history of descriptive studies that benefit researchers but have no direct implications for participants. For example, a bibliography of research up to 1977 in Papua New Guinea identifies 135 publications that describe Melanesian blood groups but only 25 concerned with treating malaria.3 Recently, researchers have begun doing interventional studies that might help participants. Some complex interventions have been tested in randomised controlled trials, such as the effect of improved services to treat sexually transmitted diseases on the incidence of HIV.4

Even when research asks questions that might provide useful information, health professionals still confront an increasing pile of medical literature. An up to date systematic review of randomised controlled trials could have helped the health professional respond to Yakamul’s question. Systematic reviews offer a critical link in getting research into practice. Clinicians, managers, and patients can draw on them whether they live in Burkina Faso or the Cayman Islands.5 Reviews and interventions are internationally relevant, but implementation should be done nationally and locally, influenced by the resources available and circumstances. It is naive to believe that systematic reviews alone will change practice in the West or in developing countries.

This article examines the constraints on good practice in developing countries and identifies opportunities that will help the implementation of research findings by health professionals, policymakers, and patients. We aim to reflect our opinions and experiences and to generate discussion; we do not aim to be comprehensive.

Constraints on good practice

In theory, well organised government funded health systems in developing countries provide good value for money. In many countries, healthcare systems are inefficient, lack reliable funding, and employ large numbers of health workers for whom there are no incentives to provide effective care. Research led practice seems to be irrelevant when systems are in disarray. However, it is precisely these services that governments and international donors such as the United Kingdom’s health and population aid programme are attempting to improve through targeted activities; the donors’ logic seems to be that if you cannot make the system work, focus on delivering a single intervention that may save lives. For example, vitamin A supplementation is an intervention that a good systematic review shows is effective in decreasing the risk of illness and death in young children.6 As new ideas and research findings emerge, donors and policymakers add more “magic bullets” to the healthcare package. Over time this process leads to the development of a comprehensive package that the system was unable to deliver in the past. Nevertheless, there is little evidence that some established magic bullets work. For example, evidence that monitoring children’s growth prevents malnutrition and infant death is weak, yet every day health staff and mothers spend thousands of hours at health clinics weighing children.7 Standard guidelines for antenatal care in many countries recommend up to 14 visits per pregnancy, although a recent trial of fewer visits showed no adverse effects on pregnancy outcome.8 When healthcare interventions are being implemented the whole healthcare system should be considered, and activities for which evidence of impact is weak should be discarded and new evidence based activities should be added when appropriate.

An even bigger constraint on implementing effective healthcare practices is politics. The per capita allocations for health care by governments in developing countries may be modest, but the totals are large. Therefore, there will always be people with vested interests keen to influence the distribution of funds. Capital investment in new facilities and high technology equipment appeals to politicians and those who vote them in, even when these investments may be the least cost effective. Corruption creates incentives that militate against sensible decision making. These problems are universal, but evidence of effectiveness could provide some support for health professionals who are attempting to contradict claims that high technology will cure all.

Outside government, there are further perverse incentives that promote bad practice. Private practitioners sometimes prescribe regimens that are different and more expensive than those that are standard in the guidelines issued by the World Health Organisation.9 Knowledge is part of the problem; practitioners often depend on drug representatives for information. Commercial companies have much to gain from promoting drugs, whether or not they work. Because of inadequate regulation, promotional activities often extend beyond ethical limits set by many Western societies. At times they may come disguised as continuing medical education. The situation is aggravated by the lack of effective policy regarding marketing approval for drugs. In Pakistan, for example, the lack of any effective legislation means that authorities register about five new pharmaceutical products every day.10

Ultimately it is the medical profession that is the main constraint on change. One reason is that in many developing countries, ownership of equipment or hospital facilities by doctors is allowed, or even encouraged, by medical societies and training institutions. This creates conflicts of interest, which may explain the overuse of many diagnostic tests.11 Furthermore, clinicians and public health professionals in many developing countries are trained in programmes that incorporate traditional models of Western medical education. They base their medical knowledge on foreign (mainly European and US) medical literature, the opinions of foreign visitors, and the opinions of drug company representatives who are promoting new products. In developing countries, medical practitioners respect doctors who know about pathology. Clinicians in many developing countries believe that this scientific understanding is essential to designing rational treatment. Doctors also value the freedom to practise medicine as they deem best. Advocates of change need to be aware that some strategies designed to implement research findings will be perceived as a threat to this freedom.

Initiatives to develop evidence based care

Researchers, policymakers, and clinicians have already done much to engender a science led culture in developing countries. The Rockefeller Foundation in the United States has supported training in critical appraisal for over 15 years, producing clinicians committed to practising evidence based medicine in their own countries.12 Practitioners in developing countries are familiar with evidence based practice policies such as those for pneumonia in children,13 and practice guidelines have been used in Papua New Guinea since 1966.14 The availability of methodological tools for improving the validity of guidelines has increased dramatically; in the Philippines methodological issues in guideline development were identified, and an approach was developed that could be used by other developing countries.15 Furthermore, the WHO’s essential drugs programme has taken a strong lead internationally in advocating rational prescribing. Together with the International Network for the Rational Use of Drugs it has disseminated research about effectiveness. The network has also encouraged the development of management interventions to promote good prescribing practice.16,17

Sources of information about evidence based practice

| Type | Name | Details | Contact Information |

| Electronic journal | The Reproductive Health Library | Systematic reviews with | World Health Organisation, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland, or khannaj@who.ch |

| Websites | Australasian Cochrane | commentaries | http://som.flinders.ed.au/fusa/cochrane |

| Paper journals | Centre | Reviews of abstracts | Synapse.info@medlib.com, or |

| Summaries | The Cochrane Library | Web subscription | http://www.medlib.com/ |

| of potential sources | Effectiveness Update | Summaries of systematic | http://www.liv.ac.uk/lstm/ind98/edu/html |

| Ovid | reviews that are relevant to | http://www.ovid.com.dotm |

In 1997, some national governments began taking action to introduce research led practice in their countries. In Chile, the Ministry of Health has established with support from the European Union an office to promote the implementation of research findings. In Palestine, doctors are working with the health minister to establish a national committee on clinical effectiveness. In Thailand, the Ministry of Health and the National Health Services Research Institute are setting up an office to guide a national quality assurance programme (A Supachutikul, personal communication). In South Africa, the Medical Research Council has committed support to the production of systematic reviews and evidence based practice (J Volmink, personal communication). In Zimbabwe and South Africa, researchers are working with their governments to test ways of getting research into policy and practice.18 In the Philippines, the Department of Health has funded projects to develop evidence based guidelines for its cardiovascular disease prevention programme.19

International donors and organisations involved with health in the United Nations have influenced the content and direction of health services in developing countries. They have funded one-off systematic reviews such as the comprehensive review of vitamin A supplementation. Now there is more sustained interest by governments and ministries of health in the production of reliable systematic reviews that are relevant to health care in developing countries. The WHO has also conducted important systematic reviews into topics such as the use of rice based oral rehydration fluid20; some of these reviews are being kept up to date in The Cochrane Library, such as the review on the effectiveness and safety of amodiaquine hydrochloride in treating malaria.21 The effective health care in developing countries project, supported by the United Kingdom’s health and population aid programme, aims to produce and maintain over 30 systematic reviews in the next four years as part of the Cochrane Collaboration; researchers and clinicians in India, Chile, South Africa, and Zimbabwe are participating in the process.

The World Bank has constructed an essential package of effective healthcare interventions. Many assumptions were made about the effectiveness of treatments, and systematic reviews were not used in compiling the package, as there were very few available then.22 Now, however, there is the opportunity to refine the contents of the package on the basis of reliable evidence available from systematic reviews.

In the next few years there will be opportunities to draw on more reliable evidence of effectiveness. Methods to apply cost-utility analyses to systematic reviews are already being developed for this process (T Jefferson, personal communication). International donors are also promoting reform of the healthcare sector, especially in the areas of institutional change in governmental health policies. Implementation of reforms is affecting a number of developing countries. Although reforms are different in each country,23 change provides the opportunity for introducing evidence based approaches.

Evidence of effectiveness is also of interest to those who use healthcare services. In Pakistan the Network of Associations for the Rational Use of Medication has launched a consumer oriented journal, Sehat aur sarfeen, to help develop community pressure against poor pharmaceutical and prescribing practices. In India, the inclusion of medical services under the Consumer Protection Act has increased the accountability of doctors and made patients, especially those in urban areas, more aware of their rights as consumers.

Future directions

Given the current momentum, how can we promote the use of research findings in practice? We started this article by indicating that systematic reviews were necessary prerequisites to aid clinicians in making sense of evidence buried in a mass of conflicting opinion. Another prerequisite is to ensure that people in developing countries have access to up to date information (box). (Other sources of information can be found in an earlier article in this series by Glanville et al.24) It is important to disseminate research findings to a variety of audiences, including other health professionals, lay readers, and journalists. Many mechanisms for implementing good practice are already available in developing countries. In some, guidelines and standardised treatment manuals are better developed than in the West.14 Other guidelines are likely to become more evidence based over time. Reviews of specific interventions to change professional practice, such as those by Bero et al25 and those presented by Ross-Degnan et al (international conference on improving use of medicines, Chiang Mai, Thailand, April 1997), will help to ensure that change occurs, but dissemination efforts in developing countries need further evaluation.

Mechanisms for dissemination need to be integrated into healthcare policy and management; this can be done by using a multilevel approach. For example, in June 1995 a large trial showed that magnesium sulphate was the most effective treatment for eclampsia. At that time one third of the world’s obstetric practices were using other, less effective therapies.26 The first level of integration begins internationally, with the WHO ensuring that magnesium sulphate is included on the list of essential drugs. At the national level, ministries of health should include the drug in their purchasing arrangements and ensure that medical curriculums and clinical guidelines are consistent with best treatment practices. At the local level, midwives and doctors need to be aware of the drug’s value in treating eclampsia. Additionally, quality assurance programmes and informal clinical monitoring should include the treatment of eclampsia in their audit cycles.

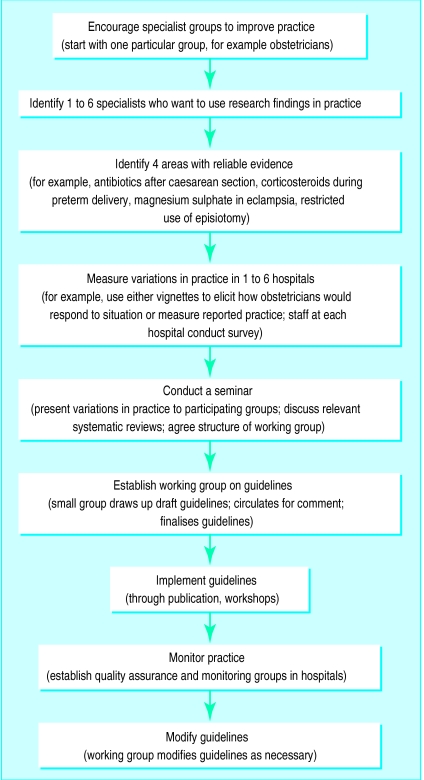

There are a variety of new initiatives to encourage practitioners and policymakers to assess and implement research evidence. Some clinicians examine variations in practice between themselves, for example in Thailand (A Supachutikul, personal communication), and a framework to assist clinicians in applying research evidence to their practice was developed in Chile at the Santiago seminar for getting research into policy (November 1995) (figure). In the Philippines, an ongoing study is looking at the use of standardised clinical encounters in evaluating practice variation. Another mechanism being investigated through the Reproductive Health Library is to ask health professionals how they would use the results from a particular systematic review in their practice of reproductive health; if successful, this intervention could be used in other clinical specialties.

In addition to addressing the need for the dissemination of information, policymakers must also address the barriers to wider acceptance of evidence based guidelines. In particular, policies on the ethical promotion of drugs, as well as policies governing continuing medical education and ownership of medical equipment need to be developed.

It is members of the public—irrespective of income or location—who make the ultimate decision whether to avail themselves of our care or advice. Paradoxically, people living in developing countries are sometimes the most critical of the care offered by health professionals. Yakamul was from a tribe that was poor: life was full of risks and time was always short. The villagers were not afraid to be selective about taking only the components that they valued from either traditional or Western health systems.27 As health professionals, we should remember that it is members of the public who need information about effectiveness. In communicating this information we should be honest, humble, and explicit when the evidence is equivocal.

Figure.

Framework for getting research findings into practice devised at the Santiago seminar for getting research findings into policy (November 1995)

Footnotes

Funding: RD, RS, and PG are part of the Effective Health Care in Developing Countries Project, supported by the United Kingdom Department for International Development and the European Union Directorate General XII. The funding organisations accept no responsibility for any information provided or views expressed.

Conflict of interest: None.

The articles in this series are adapted from Coping with Loss, edited by Colin Murray Parkes and Andrew Markus, which will be published in July.

References

- 1.Gulmezoglu AM, Garner P. Malaria in pregnancy in endemic areas. In: Garner P, Gelband H, Olliaro P, Salinas R, Volmink J, Wilkinson D, eds. Infectious diseases module, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [updated 4 March 1997].The Cochrane Library. Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 1998.

- 2.National Audit Office; Overseas Development Administration. Health and population overseas aid: report by the Comptroller and Auditor General. London: HMSO; 1995. (CH 782.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornabrook RW, Skeldon GHF. A bibliography of medicine and human biology of Papua New Guinea. Goroka: Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research; 1977. (Monograph series No 5.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosskurth H, Mosh F, Todd J, Mwijarimbi E, Klokke A, Senkorok, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346:530–536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garner P, Kiani A, Salinas R, Zaat J. Effective health care. Lancet. 1996;347:113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaton GH, Martorell R, Aronson KJ, Edmonston B, McCabe G, Ross AC, et al. Effectiveness of vitamin A supplementation in the control of young child morbidity and mortality in developing countries. Toronto: University of Toronto; 1993. (Administrative Committee on Coordination/Subcommittee on Nutrition discussion paper No 13.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross DA, Garner P. Growth monitoring. Lancet. 1993;342:750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munjanja SP, Lindmark G, Nyström Randomised controlled trial of reduced-visits programme in Harare, Zimbabwe. Lancet. 1996;348:364–369. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uplekar MW, Rangan S. Private doctors and tuberculosis control in India. Tuber Lung Dis. 1993;74:332–337. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(93)90108-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhutta TI, Mirza Z, Kiani A. 5.5 new drugs per day! The Newsletter. 1995;4:3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garner P, Kiani A, Supachutikul A. Diagnostics in developing countries. BMJ. 1997;315:760–761. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7111.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halstead SB, Tugwell P, Bennett K. The international clinical epidemiology network (INCLEN): a progress report. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:579–589. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90222-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shann F, Hart K, Thomas D. Acute lower respiratory tract infections in children: possible criteria for selection of patients for antibiotic therapy and hospital admission. Bull WHO. 1984;62:749–753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biddulph J. Standard regimens—a personal account of Papua New Guinea experience. Trop Doct. 1989;19:126–130. doi: 10.1177/004947558901900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Multisectoral Task Force on guidelines for the detection and management of hypercholesterolemia. Hypercholesterolemia guidelines development cycle. Philippines J Cardiol. 1996;24:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organisation. Interim report of the biennium, 1996-1997: action programme on essential drugs. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross-Degnan D, Laing R, Quick J, Ali H, Ofordi-Adjei D, Salako L, et al. A strategy for promoting improved pharmaceutical use: the international network for the rational use of drugs. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:1329–1341. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90037-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effectiveness Network (European Union) A statement of intent by three projects in the international co-operation with developing countries programme (framework 4). Brussels: European Union Directorate General; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Multisectoral Task Force on the detection and management of hypertension. Philippine guidelines on the detection and management of hypertension. Philippines J Intern Med. 1997;35:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gore SM, Fontaine O, Pierce NF. Impact of rice based oral rehydration solution on stool output and duration of diarrhoea: meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials. BMJ. 1992;304:287–291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6822.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olliaro P, Nevill C, Ringwald P, Mussano P, Garner P, Brasseur P. Systematic review of amodiaquine treatment in uncomplicated malaria. Lancet. 1996;348:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)06217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Bank. World development report 1993: investing in health. Washington: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez J, Sandiford P, Garner P. International transfers of NHS reforms. Lancet. 1994;344:956. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glanville J, Haines M, Auston I. Finding information on clinical effectiveness. BMJ. 1998;317:200–203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7152.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA.on behalf of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings BMJ 1998317465–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eclampsia Trial Collaborative Group. Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the collaborative eclampsia trial. Lancet. 1995;345:1455–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welsch RL. Washington: University of Washington; 1982. The experience of illness among the Ningerum of Papua New Guinea [dissertation] (Available through University Microfilms International, No 3592.) [Google Scholar]