I keep copies of all major acts of parliament relevant to health and health care. I have consulted them from time to time over the past seven years. However, it is the 1848 public health act (An Act for Promoting Public Health) that I have looked at most regularly. Why does this act fascinate me, and why did I wish to see further reflection on its background and consequences? The answers lie in an understanding of the context of the act and its consequences. This is not because of the act’s specific contents—though the regulations on slaughterhouses and the selling of meat are fascinating—but because of the general issues the act raises:

The principles of improving the public health

The role of the state in improving the health of the people

The organisation of public health at all levels in England and Wales

The consequences of the act and the manner in which it raised the profile of public health

- The links to current issues in health and health cre.

Summary points

- The 1848 act identified all the major public health issues of the time and established a structure for dealing with them

- Public health became the responsibility of local people

- Though health has improved immeasurably since 1848 some problems remain; the act’s approach remains relevant today

The purpose of the act was to promote the public’s health and to ensure “more effective provision ... for improving sanitary conditions of towns and populace places in England and Wales.” Such clarity of purpose is impressive. The background to the act was a remarkable piece of work on mortality and morbidity rates across the country. The work established clear inequalities in health and recognised that some fundamental issues, such as poverty, had to be addressed. In this sense the act is similar to the response to many other public health issues—most changes have occurred because of a failure in the systems or as a response to a crisis. Planning ahead on the basis of evidence and projections seems much more difficult. I will now discuss each of the general issues raised by the 1848 act.

Principles of improving public health

The 1848 act was written before the sciences of bacteriology and pathology were fully established and diagnostic criteria set. The comprehensiveness of the act, however, is impressive. The act included the organisation of public health and all major issues at the time—for example, poverty, housing, water, sewerage, the environment, safety, and food. It set out who was accountable and the penalties involved. It emphasised strong local involvement. If it was weak, it was perhaps on air quality, and on its failure to tackle rural issues in favour of “towns and populous places”—issues which were, and remain, problems. It does not specifically mention research (though data collection is emphasised), nor does it raise general educational issues, both of which would feature strongly in any current thinking.

Role of the state

The role of the state is a fundamental public health issue. Should the state intervene with laws and bylaws, or should information be provided and individuals have choice and be allowed to make up their own minds? How far should the state go to protect the health of its citizens? The 1848 act took the view that as many of the problems affected the population as a whole, water, or sewerage, then health improvement was the responsibility of national and local government, and “inspectors of nuisances” would be appointed to deal with problems.

Could this be done now? Would the vested interests of the blood or tripe boilers mean that legislation would be delayed? The process of legislation is one in which an idea for improving health or health care is championed by an individual or group and is translated into a clear policy which then provides the framework for the parliamentary draftsman. The process is carried out openly with debate, discussion, and where appropriate amendment, before the final act is given royal assent. It can require great courage and perseverance to take this process through to a conclusion in the light of opposition from groups or individuals.

It still leaves open to question the “nanny state” and how far government can go in legislating for improved health and protection of health. Those who drafted the 1848 act had no such doubts, though they were concerned mainly with public health and health protection, rather than with the health of individuals.

Organisation of public health

One of the most fascinating aspects of the 1848 act was its focus on organisation. National and local boards of health were to be set up that would be accountable to and funded by the Treasury in relation to visits and inspections. Superintending inspectors and officers of health could be appointed. Individual towns and cities could call for inspection if mortality was too high. There was a power to summon witnesses. A report would be published and submitted to the Privy Council. Subsequent finance, if required, would be raised through local rates. The contemporary relevance of these will be discussed later.

Consequences of the act

Perhaps the most important issues for me were the consequences of the act. The fact that the national and local boards of health could call for action to improve health meant that local people became involved in thinking about the health of their people, and the 19th century public health movement was formed. In Durham, for example, the city council, the cathedral, the university, and the medical profession petitioned for an inspection because local mortality was too high. A superintending inspector visited, summoned witnesses, and reported. This process was replicated up and down the country. Public health had arrived and was seen to be the responsibility of local people and their elected representatives. We could make this happen again.

Links to current issues

Most of the principles outlined above apply at present. The appointment of a minister for public health provides top level political input. The development of health improvement plans, health action zones, and healthy living centres and the creation of a strategy for health (set out in Our Healthier Nation1) provides the framework for action. This encourages health authorities, local government, trade unions, employers, voluntary bodies, universities, local groups, etc to become fully involved. Interestingly, the 1848 act heavily involved the church and church wardens, and religious organisations remain a relatively untapped resource for improving health.

Improving health is a multidisciplinary task, and all professionals need to participate. Health is not just about living longer, but about a better quality of life and wellbeing. I have wondered at times whether renaming my department the Department of Health and Happiness would send a signal about the relation between health and feeling better and improving the common weal.

The future

What then has changed over the past 150 years, and do we need a new act to continue to improve health in England? Health has improved immeasurably in all variables studied. Life span, mortality, disappearance of diseases, and quality of life have all improved considerably. Yet problems remain. Mortality in young men is still too high. There is still excess winter mortality—not so marked in other northern countries. Inequalities in health exist, and may even have become more marked. The role of women still needs strengthening. Mental health needs greater priority. Environmental problems, though different, are a continuing cause for concern.

So how can we continue to improve health in England? For the past six years I have published as part of the chief medical officer’s annual report on the state of the public health a series of principles that set the tone for assessing health issues and my response to new problems. These principles have been expanded recently in a book.2 How do they relate to current health issues?

Health for all

All citizens in the country need to be treated equally. This is an issue of social justice. The inequalities in health reflect a need to consider issues such as poverty, unemployment, housing, and the environment. No simple solutions exist—a range of policies is required.

A strategy for health

The Health of the Nation strategy and the recent strategy set out in Our Healthier Nation1 provide the vehicle for setting out a strategic approach, across government, to improving health. Through four key areas, and national targets which can be monitored on a regular basis, this approach allows a range of interests to be worked on with a common agenda. This partnership approach is critical. The chief medical officer’s project to strengthen the public health function, which has been in progress for the past year, has begun to identify ways in which this strategic view can be put into practice. There is a need for both capacity and capability and for a multidisciplinary organisation that could bring together in a powerful coalition all those concerned with improving the health of the people of England. The 1848 act had a board of health—a high level committee to oversee the changes proposed. Perhaps something similar would be useful now.

In terms of the NHS, the development of National Service Frameworks will provide some of the strategic input into providing a service to the whole community with equality of access and of quality of care. The cancer service framework, for example, shows how this might be done and what the difficulties are.3

Involvement of the public and patients

The involvement of the public and patients is central to improving health and health care. This was not a major feature of the 1848 act, other than at local authority level. We need to explore better ways of ensuring full public participation. Over the past few years this involvement has grown, and this is to be welcomed. Those who have responsibility for health and health care must ensure that they communicate effectively with the public on a whole range of issues—in particular, on risk and uncertainty.

Intelligence and surveillance

Public health cannot continue to improve unless the facilities exist for ensuring that we know what is happening and what is changing. These can range from the collection of statistics on cancer registration to “horizon scanning” for new approaches to treatment. Infectious disease surveillance provides an excellent example of a national system that is able to identify outbreaks and new organisms emerging. Part of our intelligence and surveillance strategy is to assess the impact on health of policies from all government departments and to consider the longer term consequences of new developments in areas of legislation unrelated to health.

Need for strong evidence base

Strong evidence is now at the heart of the process of improving health and is to be widely welcomed. The difficulties related to evidence based decisions are (a) generating the evidence and (b) taking action on the basis of the evidence both in the community and by the professions. Much evidence on how to improve health and the quality of care already exists. The potential to make things better exists. It is the implementation which is often lacking.

Importance of education, research, and ethical considerations

Many of the improvements listed above could occur if the professions and the public recognised the importance of education and the role of learning in changing attitudes and behaviour. The purpose of medical education,4 and the changes which have been introduced over the past few years, has been to improve the quality of care provided. In a similar way the public understanding of science has helped the public to recognise some of the complexities of clinical practice.

Research is fundamental to improving health, and investment in new methods of care and understanding of disease mechanisms must continue. The NHS research and development programme, the research councils, and the medical research charities provide a remarkable resource to develop the research agenda.

Ethical issues will remain central to improving health, and the value base which is adopted sets the overall framework for decision making. New methods of treatment and investigation raise new moral dilemmas, and each new method requires careful and public consideration.

Conclusion

So do we need a new public health act? Much of what has been discussed above needs no legislative framework; it requires the implementation of what is already known. In some areas—notably, in the field of infectious disease—there is a clearer case for legislation. Across government, legislation on the environment and food safety are under way and will bring a sharper focus to health issues. The potential for improvement is considerable, and much can be done if all concerned work to a shared agenda to improve health.

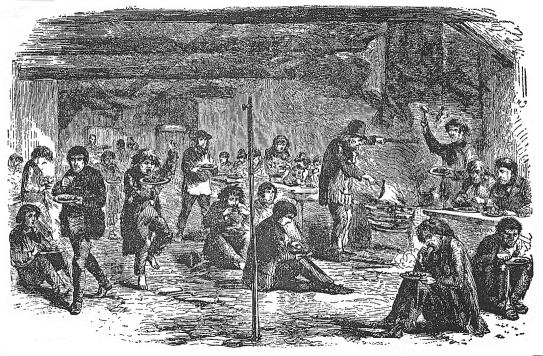

Figure.

Dinner at a cheap lodging house in mid-19th century London—predating legislation on food safety

Editorials by Alderslade, Palmer, Recent advances p 584, Education and debate pp 587, 592

Footnotes

Competing interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Secretary of State for Health. Our healthier nation: a consultation paper. London: Stationery Office; 1998. (Cm 3852.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calman KC. The potential for health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.A policy framework for commissioning cancer services. A report by the Expert Advisory Group on Cancer to the chief medical officers of England and Wales. London: Department of Health; 1995. (Calman-Hine report.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Working Group on Specialist Medical Training. Hospital doctors: training for the future. London: HMSO; 1993. [Google Scholar]