Abstract

Myxococcus xanthus is a gram-negative bacterium which has a complex life cycle that includes multicellular fruiting body formation. Frizzy mutants are characterized by the formation of tangled filaments instead of hemispherical fruiting bodies on fruiting agar. Mutations in the frz genes have been shown to cause defects in directed motility, which is essential for both vegetative swarming and fruiting body formation. In this paper, we report the discovery of a new gene, called frgA (for frz-related gene), which confers a subset of the frizzy phenotype when mutated. The frgA null mutant showed reduced swarming and the formation of frizzy aggregates on fruiting agar. However, this mutant still displayed directed motility in a spatial chemotaxis assay, whereas the majority of frz mutants fail to show directed movements in this assay. Furthermore, the frizzy phenotype of the frgA mutant could be complemented extracellularly by wild-type cells or strains carrying non-frz mutations. The phenotype of the frgA mutant is similar to that of the abcA mutant and suggests that both of these mutants could be defective in the production or export of extracellular signals required for fruiting body formation rather than in the sensing of such extracellular signals. The frgA gene encodes a large protein of 883 amino acids which lacks homologues in the databases. The frgA gene is part of an operon which includes two additional genes, frgB and frgC. The frgB gene encodes a putative histidine protein kinase, and the frgC gene encodes a putative response regulator. The frgB and frgC null mutants, however, formed wild-type fruiting bodies.

Myxococcus xanthus is a gram-negative bacterium that displays a complex life cycle. On nutrient-rich agar, rod-shaped vegetative cells spread outwards in organized groups referred to as swarms. In contrast, when nutrients are limiting, approximately 100,000 cells aggregate to form a fruiting body, within which individual cells differentiate into myxospores (for reviews, see references 8 and 28). Gliding motility and extracellular signaling are required for both vegetative swarming and developmental aggregation (7, 10, 29).

The Frz signal transduction pathway coordinates directed cell movements during both vegetative swarming and developmental aggregation of M. xanthus (for a review, see reference 35). The frz genes encode proteins that are homologous to chemotaxis proteins from the enteric bacteria (17, 18, 19). Mutations in the frz genes alter the reversal frequencies of individual cells (2), resulting in defects in directed motility to both attractant and repellent stimuli (26). Since there is a strong correlation between the behavior of cells under both vegetative and developmental conditions and the methylation of FrzCD, a methylated chemotaxis receptor protein, it has been suggested that the Frz signal transduction pathway processes both vegetative and developmental chemotactic signals (16, 26). During development, frz mutants fail to form fruiting bodies. Instead, they move in circular or spiral groups, forming tangled filaments of cells (36). It has been hypothesized that the frz mutants are defective in sensing self-generating chemotactic signals that are required to attract cells into aggregation centers (16, 26, 32). Although none of the chemotactic signals suggested to be responsible for developmental aggregation have yet been identified, we have described a gene called abcA that might be responsible for the transport of such a signal (34). The abcA mutant fails to form normal fruiting bodies; instead, it forms frizzy aggregates under developmental conditions. However, the frizzy phenotype of the abcA mutant could be rescued extracellularly by live cells or cell extracts of other strains of M. xanthus, suggesting that the AbcA protein (proposed to be an ATP-binding cassette [ABC] transporter) is involved in export of developmental signals rather than in the sensing of these signals. In this paper, we report the discovery of a second gene, called frgA (for frz-related gene), with a similar phenotype. The frgA mutant forms frizzy aggregates under developmental conditions but appears to retain normal chemotactic functions in a spatial chemotaxis assay. Most interestingly, the frizzy phenotype of the mutant can be rescued extracellularly by live cells or cell-free supernatant of developing cells of other strains, suggesting that the defect is in signal generation rather than signal transduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen) was used for DNA manipulation. M. xanthus was cultured vegetatively in Casitone-yeast extract (CYE) (4). Development of M. xanthus was initiated by placing 10 μl of 1,000 Klett cells (5 × 107 cells) on 1.5% agar plates containing CF (10) or MMC (23) medium. Liquid cultures were incubated at 32°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Agar plates were incubated at 34°C. Development of M. xanthus in submerged culture was carried out as described previously (14). The cell-free conditioned medium was obtained from a submerged culture that was developed in the MMC medium for 14 h at 34°C.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant feature | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| M. xanthus | ||

| DZ2 | Wild type | 3 |

| DZF1 | pilQ1 | 21 |

| DK1300 | sglG | 11 |

| DZ4148 | frzE | 26 |

| DZ4214 | DZ2::pKY520 frgA520 | This study |

| DZ4217 | DZ2::pKY566 frgB566 | This study |

| DZ4218 | DZ2::pKY563 frgC563 | This study |

| DZ4291 | DZ2::pKY583 frgA583 | This study |

| DZF3379 | frzE pilQ1 | 2 |

| DZF4216 | DZF1::pKY520 frgA520 pilQ1 | This study |

| DZF4290 | DZF1::pKY583 frgA583 pilQ1 | This study |

| DZF4332 | DZF1::pKY566 frgB566 pilQ1 | This study |

| DZF4333 | DZF1::pKY563 frgC563 pilQ1 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | Cloning vector; Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pZErO-2 | Cloning vector; Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pKY458 | pZErO-2 carrying 8.5-kb DNA from DZ4214 | This study |

| pKY468 | Cloning vector; Kmr | 6 |

| pKY520 | pZErO-2 carrying an internal DNA fragment of frgA | This study |

| pKY536 | pZErO-2 carrying 6-kb DNA from DZ4214 | This study |

| pKY563 | pZErO-2 carrying an internal DNA fragment of frgC | This study |

| pKY566 | pKY468 carrying an internal DNA fragment of frgB | This study |

| pKY583 | pCR2.1 carrying an internal DNA fragment of frgA | This study |

DNA manipulations and sequence analysis.

DNA manipulations were performed using standard protocols (24). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Operon Technologies, Inc. PCRs were carried out with Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) or Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) in the presence of 10% glycerol. Reverse transcription-PCR was performed as described elsewhere (33). Most of the DNA sequencing was carried out at the DBS sequencing facility at the University of California—Davis. Gapped BLAST was used for homology searches (1). DNA and amino acid sequences were analyzed using Gene Inspector (Textco Inc.) and Lasergene computer software (DNASTAR Inc.).

Plasmid construction.

The construction of a library of plasmids containing approximately 500-bp DNA fragments from M. xanthus has been described elsewhere (6). pKY458 carries an 8.5-kb XhoI DNA fragment from DZ4214 containing the C-terminal end of frgA and an 8-kb downstream region. Genomic DNA of DZ4214 was digested with XhoI, self-ligated, and used to transform E. coli to kanamycin resistance due to the presence of the construct pKY458. pKY536 carries a 6-kb PstI DNA fragment from DZ4214 containing the N-terminal half of frgA and a 3.5-kb upstream region. pKY536 was constructed as described for pKY458 construction except that PstI was used for DNA digestion instead of XhoI. pKY458 and pKY536 were used to determine the DNA sequence of frgABC and flanking regions. pKY520 is a derivative of pZErO-2 carrying a 420-bp internal DNA fragment of frgA (Fig. 1A). It was originally constructed as part of a plasmid library used to mutagenize strain DZ2 and was shown to recombine within the frgA gene. The plasmid DNA of pKY520 was isolated from DZ4214 by transforming E. coli with total genomic DNA from DZ4214. pKY563 is a derivative of pZErO-2 and carries a 278-bp PstI-NotI internal DNA fragment of frgC (Fig. 1A). pKY566 is a derivative of pKY468 carrying a 428-bp internal DNA fragment of frgB (Fig. 1A) which was PCR amplified with two oligonucleotides, 5′-GACCTCGAGGCGCGGGCCTGGTGCTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GACGGATCCGCGGCGATGGGGTTCTTGAG-3′. The PCR fragment was inserted into pKY468 as an XhoI-BamHI fragment. pKY583 is a derivative of pCR2.1 carrying a 665-bp internal PCR fragment of frgA (Fig. 1A) which was PCR amplified with two oligonucleotides, 5′-CCGCTGCGACTGAACATGCC-3′ and 5′-GGAGGCGACGTAGTCGAAGG-3′. The PCR fragment was directly ligated to the pCR2.1-TOPO DNA.

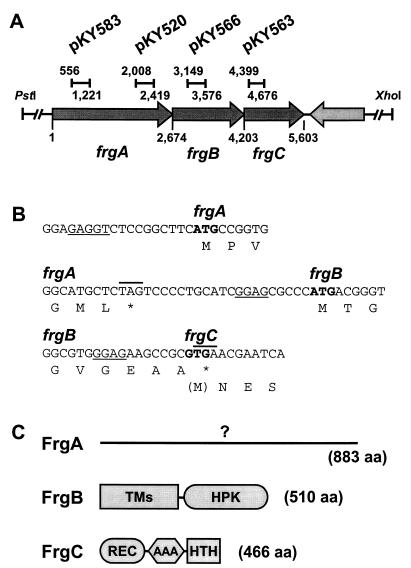

FIG. 1.

Organization of the frgA, frgB, and frgC genes and their protein products. (A) Physical map of the frgABC operon and the plasmids used to create insertion mutants. The numbers indicate the nucleotide position of each site from the translational start site of the frgA gene. The bars indicate the DNA fragment from each gene that was cloned into the respective plasmids and used for mutant construction, as described in the text. (B) Predicted ribosome binding sites (underlined) and termination codons (asterisks and lines above sequence) of the frgA, frgB, and frgC genes. The predicted initiation codons are highlighted in boldface. (C) Domain organization of the deduced products of the frgA, frgB, and frgC genes. FrgA is not similar to any protein in the database. FrgB contains eight predicted transmembrane domains (TMs; from amino acid (aa) residues 1 to 264) and a histidine protein kinase domain (HPK; from amino acid residues 283 to 498). FrgC consists of a receiver domain (REC; from amino acid residues 7 to 118), an ATPase domain (AAA; from amino acid residues 160 to 303), and a helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain (HTH; from amino acid residues 440 to 461).

Construction of M. xanthus mutants.

Plasmid DNAs were introduced into M. xanthus by electroporation under conditions described previously (12). All the plasmids used in this study are unable to replicate autonomously in M. xanthus. Thus, selection of transformants that were antibiotic resistant allowed the growth of only cells carrying a plasmid which had recombined into the chromosome. Mutants were selected by the method described previously (6). The mutations were characterized by PCR amplification or by restriction mapping after the DNA fragments containing the insertions were cloned.

Mutant characterization.

The vegetative and developmental behaviors of the mutants were observed microscopically with a Zeiss microscope and a Nikon Labphot-2 microscope. Images were captured with a Dage-MTI CCD-72 series camera. Developmental, swarming, chemotaxis, motility, and FrzCD methylation assays were carried out with the protocols described previously (27).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The frgABC nucleotide sequence has been deposited in the GenBank DNA sequence database (accession number AF204400).

RESULTS

Isolation of a new frizzy mutant.

M. xanthus DZ2 was mutagenized by insertion of a gene fragment as described previously (6). This method has the advantage of being more random than Tn5 mutagenesis. Briefly, we prepared a library of kanamycin-resistant plasmids carrying about 500 bp of random DNA fragments from M. xanthus DZ2. The plasmids were introduced into M. xanthus by electroporation. These plasmids cannot replicate in M. xanthus, so only cells carrying a plasmid that has recombined into the chromosome can grow in the presence of kanamycin. Since the DNA fragments are smaller than most genes, those carrying internal fragments of a gene should create insertion mutations upon recombination. Among 5,000 kanamycin-resistant colonies, we isolated a mutant strain, DZ4214, that showed a weak frizzy phenotype, forming frizzy aggregates around irregular fruiting bodies on CF agar.

A new locus responsible for frizzy aggregation.

Cloning and sequence analysis revealed that DZ4214 has an insertion of the plasmid pKY520 at the C-terminal end of an open reading frame (ORF) designated frgA (Fig. 1A). The insertion of pKY520, which carries a 420-bp internal DNA fragment of frgA, should delete only the C-terminal 74 amino acids from the frgA-encoded protein (883 amino acids). Therefore, we constructed another plasmid, pKY583, and used it to create an insertion mutant with a larger deletion. In this mutant only the N-terminal 407 amino acids of FrgA could be expressed. This insertion mutant (DZ4291) showed the same frizzy phenotype as DZ4214. Since the frizzy phenotype is more obvious in the FB strain DZF1 (pilQ1) than in the wild-type strain DZ2 (12), we used the plasmids pKY520 and pKY583 to create mutations in strain DZF1. The resultant strains, DZF4216 (frgA::pKY520) and DZF4290 (frgA::pKY583), showed clear frizzy aggregates under the developmental conditions shown in Fig. 2B.

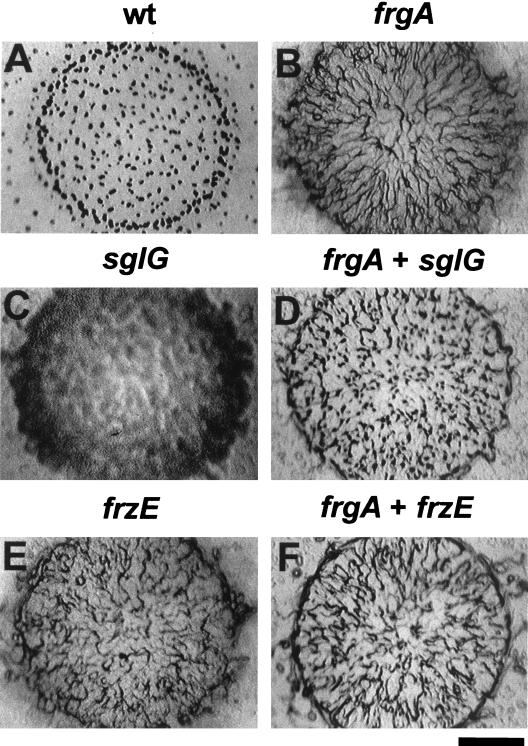

FIG. 2.

Developmental phenotype and extracellular complementation of the frgA mutant. Cells (10 μl at 2 × 109 cells/ml) were placed on CF agar plates and incubated at 34°C for 3 days and then photographed under a dissecting microscope (bar, 2 mm). (A) M. xanthus DZF1 forms wild-type (wt) fruiting bodies. (B) The frgA mutant (DZF4290) forms frizzy aggregates. (C) The sglG mutant (DK1300) is defective in aggregation. (D) The frgA mutant mixed with the sglG mutant in 4-to-1 ratio. (E) The frzE mutant (DZF3379) forms frizzy aggregates. (F) The frgA mutant mixed with the frzE mutant in 4-to-1 ratio.

Sequence analysis revealed two ORFs, designated frgB and frgC, downstream from frgA (Fig. 1A). These ORFs are oriented in the same direction as frgA. Therefore, we investigated whether all three ORFs were transcribed as one transcript. A primer originating in frgC (5′-GCACCACGTTGAGGCGGTAG-3′) was used to prepare cDNA with M. xanthus total RNA by reverse transcription. We then determined by PCR whether this cDNA encoded the frgA sequence. Two oligonucleotides, 5′-CCTTGGTGGCTTCTGGATGG-3′ and 5′-CGTGGAGGTGTTCGCGCTG-3′, that are complementary to the DNA sequence just upstream of and in frgA, respectively, were able to produce a 1,013-bp PCR product from the cDNA (data not shown). This indicates that frgA, frgB, and frgC are indeed transcribed as an operon. This finding is consistent with the proximity of the ORFs: the ORF designated frgB appears to be separated from frgA by only 20 bp (Fig. 1B), and the ORFs frgB and frgC are predicted to be translationally coupled (Fig. 1B). The ORF downstream from frgC is transcribed convergently, indicating that frgC is at the end of the operon. The DNA regions 3 kb upstream and 4 kb downstream of frgABC were also sequenced, but no other frz genes, fruiting genes, or motility genes were identified.

Insertion mutations in an operon usually block expression of downstream genes. This raised the possibility that the frizzy phenotype of the frgA insertion mutant might be caused by a polar effect on expression of frgB and/or frgC. To test this possibility, we created insertion mutations in frgB and frgC in both the DZ2 and DZF1 strains (Table 1), using the plasmids pKY566 and pKY563 (Fig. 1A). However, all of the resultant strains formed wild-type fruiting bodies on starvation medium rather than showing frizzy aggregates. This indicates that the frgA mutation is solely responsible for the frizzy aggregation seen in the mutants described above.

Analysis of frgABC.

The frgA gene is predicted to encode a protein of 883 amino acids (Fig. 1C). Hydropathy analysis indicates that FrgA should be a soluble protein. However, to date, FrgA is not similar to any protein in the sequence databases, and we were unable to determine anything about its function from the sequence data alone.

The frgB gene is predicted to encode a protein of 510 amino acids (Fig. 1C). The C-terminal region of the deduced protein, FrgB, is highly similar to histidine protein kinase domains common in two-component signal transduction systems. For example, the amino acid sequence from 269 to 510 of FrgB is 29.1 and 33.8% identical to the kinase domains of NtrB (5, 22) and HydH (30) from E. coli, respectively. However, the N-terminal half of FrgB, from amino acid residues 1 to 264, consists of at least eight transmembrane domains and does not show any similarity to the N-terminal regions of the proteins in this family.

The frgC gene is predicted to encode a protein of 466 amino acids. The deduced protein, FrgC, shows high similarity to response regulators of two-component sensory transduction systems. For example, FrgC is 45.7 and 45.0% identical to NtrC (15) and HydG (30) from E. coli, respectively. Like other members of this family, FrgC consists of a receiver domain, an ATPase domain, and a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif (Fig. 1C). This suggests that frgC encodes a transcriptional regulator. The NtrC-like proteins are known to interact with ς54 to regulate gene expression in other bacteria. Many genes encoding NtrC-like proteins have been identified in M. xanthus (13); however, frgC is not one of them. Since FrgB and FrgC are encoded by adjacent genes in a single operon, it is likely that these proteins interact and are components of the same two-component signal transduction pathway.

Characterization of the frgA mutant. (i) Developmental phenotype.

As described above, the frgA mutation causes frizzy aggregation under developmental conditions. The frizzy aggregation phenotype is weak in strain DZ2 (wild-type background), consisting of frizzy aggregates comingled with irregular fruiting bodies. However, when the mutation was introduced into strain DZF1, only frizzy aggregates were seen on starvation media, such as CF (Fig. 2B). A similar strain-dependent phenotype is seen with the abcA and frzZ mutants. While both abcA and frzZ mutants show the characteristic frizzy phenotype in strain DZF1, the abcA mutant does not show the frizzy phenotype in strain DZ2 and the frzZ mutant shows only a weak frizzy phenotype in this strain. In contrast, the frzA to -F mutants show the frizzy phenotype in both strains DZ2 and DZF1, although in strain DZ2 the frizzy aggregation pattern is less pronounced and sporulation is also defective (12). The frgA mutant showed the wild-type level of sporulation in both DZ2 and DZF1 backgrounds.

(ii) Swarming.

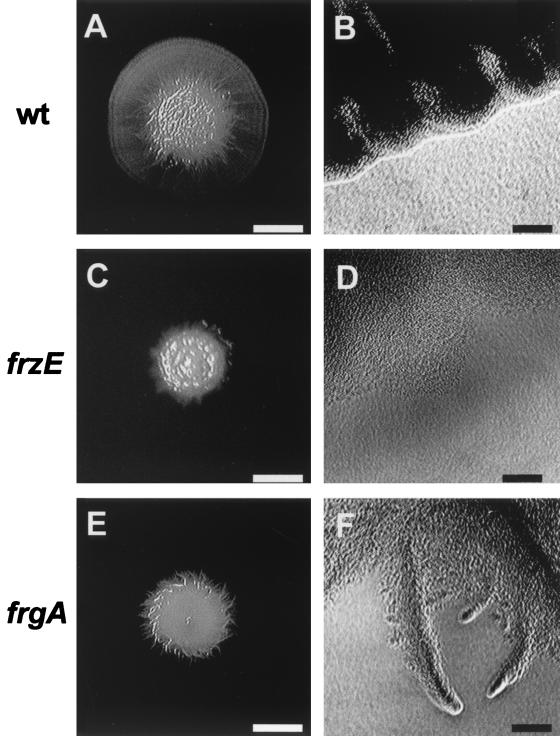

M. xanthus cells spread outward in an organized pattern on a solid surface under high-nutrient (vegetative) conditions. The frgA mutant is defective in swarming. Colonies expand at only 15% of the wild-type level on 0.3% CYE agar (Fig. 3) and 47% on 1.5% CYE agar in 2 days. The spreading ratio (the spreading area on 0.3% agar divided by the spreading area on 1.5% agar) was 0.5. Mutants with defects in S-motility spread less on soft agar than on hard agar (25), which is also true for the frz mutants. However, the frz mutants (except for frzS mutants [35]) are still able to move in the absence of A-motility, unlike S-motility mutants.

FIG. 3.

Vegetative swarming of the frgA mutant. M. xanthus DZ2 (wild type [wt]) (A and B), the frzE mutant (DZ4148) (C and D), and the frgA mutant (DZ4291) (E and F) were placed on CYE agar plates (0.3% agar) as described previously (25) and incubated at 34°C for 2 days. (A, C, and E) Overall colony morphology at a low magnification; (B, D, and F) edge of each colony at a higher magnification. White bars, 5 mm; black bars, 50 μm.

(iii) Chemotaxis and motility.

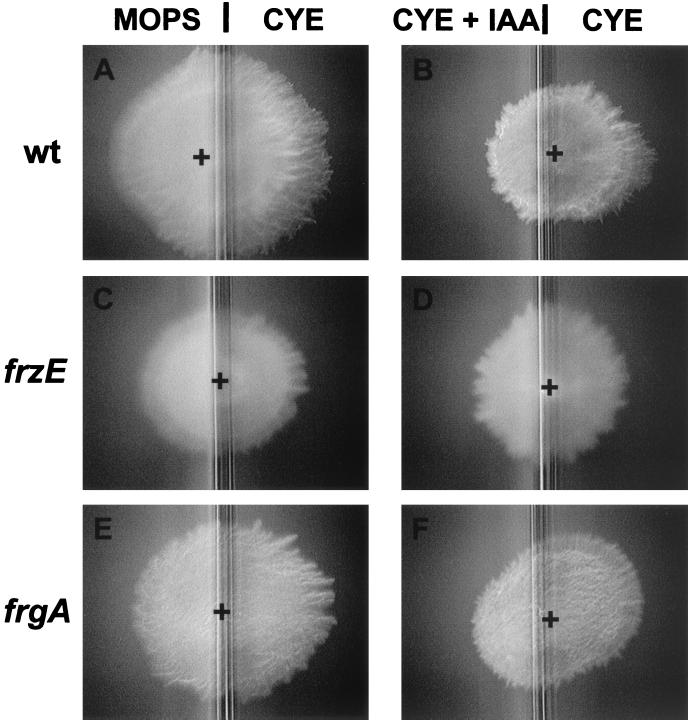

M. xanthus responds to a gradient of attractants (e.g., CYE medium) or repellents (e.g., isoamyl alcohol or dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) by modulating cellular reversal frequencies (26). The frzA to -F genes are essential for this response, and mutations in these genes cause defects in chemotaxis. In contrast, the frgA mutant responded normally to attractants (CYE medium) and repellents (DMSO and isoamyl alcohol) in a chemotaxis assay (Fig. 4). Wild-type M. xanthus reverses the direction of the gliding motility of individual cells every 6.8 min (2). Because of defects in the Frz transduction pathway, the majority of frz mutants rarely reverse, while the frzD mutant reverses every 2.2 min. In contrast, the frgA mutant showed wild-type levels of cell reversal. Thus, these results indicate that although the frgA mutant forms frizzy aggregates, it has an intact Frz transduction pathway. This phenotype was also observed in the abcA mutant (34).

FIG. 4.

Chemotaxis assay. M. xanthus DZ2 (wild type [wt]) (A and B), the frzE mutant (DZ4148) (C and D), and the frgA mutant (DZ4291) (E and F) were placed on compartmentalized agar plates as described previously (26). MOPS-CYE plates contain 10 mM MOPS buffer in the left side and the CYE medium in the right side. IAA-CYE plates contain 0.1% isoamyl alcohol in the CYE medium in the left side and the CYE medium in the right side. +, center of the original spot of cells.

(iv) FrzCD methylation.

FrzCD, a methylated chemotaxis protein, is demethylated and methylated during early development, and this modification pattern is altered in most frz mutants and many developmental mutants (9, 16). However, the frgA mutant showed the wild-type methylation pattern of FrzCD during early development (data not shown).

Extracellular complementation.

The phenotype of the frgA mutant described above and summarized in Table 2 is very similar to that of the abcA mutant. Since the frizzy phenotype of the abcA mutant can be complemented extracellularly by other strains, such as DK1300, we were interested in testing whether the frizzy phenotype of the frgA mutant might also be rescued by this strain. DK1300 harbors a mutation in sglG which results in defective S-motility and fruiting body formation (Fig. 2C). It is also known that the motility defects of the sglG mutant cannot be complemented extracellularly by other strains (11). When the frgA mutant, DZF4290, was mixed with DK1300 in a 4-to-1 ratio and placed on a CF agar plate, the mixed cell culture formed many fruiting bodies, as shown in Fig. 2D. All of the spores in the fruiting bodies were from the frgA mutant, which is kanamycin resistant, and none of the spores were from the sglG mutant, which is kanamycin sensitive. This suggested that the frizzy phenotype of the frgA mutant might be complemented extracellularly by other cells. To characterize the extracellular complementation further, we tested whether the cell-free culture supernatant (conditioned medium) from developing wild-type strain DZ2 can rescue the development of the frgA mutant. As shown in Fig. 5B, when the cell-free conditioned medium from the 14-h-old submerged culture of DZ2 was added, the frgA mutant formed mature fruiting bodies. In the absence of conditioned medium, the frgA mutant did not produce any fruiting bodies (Fig. 5A). This suggests that the frgA mutant is defective in producing extracellular molecules which are required for mound aggregation and fruiting body formation; when the molecule is supplied extracellularly, the frgA mutant is able to form fruiting bodies.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the phenotypes of the frgA, abcA, and frz mutants

| Phenotype | Form seen in mutant:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| frgA | abcA | frz | |

| Developmental aggregation in strain DZ2 (wild type) | Weak frizzy | Wild-type fruiting | Frizzy |

| Developmental aggregation in strain DZF1 (pilQ1) | Frizzy | Frizzy | Frizzy |

| Swarming on soft agar (0.3%) | Reduced | Normal | Reduced |

| Spatial chemotaxis (25) | Normal | Normal | Defective |

| Reversal frequency of individual cells | Normal | Normal | Altered |

| Conserved domains | Unknown | ABC transporter | Homologous to chemotaxis proteins |

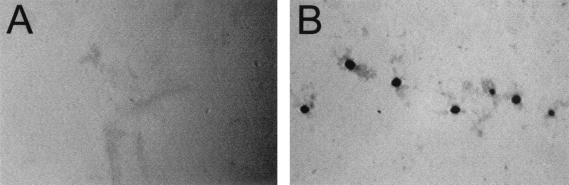

FIG. 5.

Extracellular complementation of the developmental defect of the frgA mutant in submerged culture by cell-free conditioned medium. The cell-free conditioned medium was from a submerged culture containing DZ2 cells developed in the MMC medium for 14 h at 34°C. Fruiting body development in submerged culture was carried out as described previously (14). (A) frgA mutant (DZF4290) with MMC medium only; (B) frgA mutant (DZF4290) with conditioned medium.

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that frzA to -F mutants are defective in sensing signals while the frgA mutant is defective in producing signals. Therefore, we tested whether the frz mutants still produce the signal that is missing in the frgA mutant. When the frgA mutant was mixed with the frzA, frzB, frzCD, frzD, frzE, and abcA mutants in a 4-to-1 ratio, the mixed cells did not form any fruiting bodies. Figure 2F shows the result with frzE. This indicates that the frz mutants and the abcA mutant are also defective in producing signals required by the frgA mutant, and it also suggests that the production of the signal for frgA requires the Frz signal transduction pathway and AbcA.

DISCUSSION

Developmental aggregation of M. xanthus is a multicellular event in which large numbers of cells move into aggregation centers and form hemispherical mounds of cells, the fruiting bodies. McVittie and Zahler provided the first evidence that developmental aggregation requires chemotaxis by showing that two layers of cells separated by a membrane formed fruiting bodies both above and below the membrane at the same locations (20). The signal molecules involved in aggregation remain unidentified, but they appear to be diffusible (20, 34). The frz mutants are defective in directed motility and chemotaxis and therefore cannot aggregate into fruiting bodies on starvation medium. They produce frizzy aggregates instead of fruiting bodies, suggesting that the cells fail to recognize aggregation centers; cells move without proper direction, forming tangled filaments. This behavior pattern can be the result of several possible defects, which include (i) failure to produce the hypothetical aggregation signals, (ii) failure to sense the signals, and (iii) failure to respond to the signal with changed behavior (reversing cell movements in an appropriate manner). The most studied frz genes, frzA to -G, appear to encode homologues of the chemotaxis proteins of the enteric bacteria: a methylated receptor, CheA, CheY, CheW, CheR, and CheB. The frz mutants are defective in a spatial chemotaxis assay and are defective in the control of cell reversals. The methylation of FrzCD, a methylated chemotaxis receptor protein, shows a strong correlation with the behavior of cells under both vegetative and developmental conditions. Therefore, it has been suggested that the Frz proteins sense and process both vegetative and developmental chemotactic signals.

In this paper, we report the identification of a new mutant, frgA, which appears to belong to the first group of predicted frizzy mutants: mutants that cannot produce the aggregation signals. The frgA mutant formed frizzy aggregates on starvation medium and showed some swarming on rich medium, although the level was reduced compared to that of the wild-type cells. However, cells also displayed normal chemotaxis responses in a spatial chemotaxis assay when tested for vegetative attractants (CYE media) or repellents (isoamyl alcohol and DMSO). Furthermore, cells showed the normal frequency of cell reversals on rich medium. Interestingly, the frizzy phenotype of the frgA mutant could be complemented extracellularly by live cells or cell-free supernatants from developing cells of other strains that did not show the frizzy phenotype. These results strongly suggest that FrgA is involved in producing an extracellular signal molecule that is essential for developmental aggregation and that this signal molecule can be provided by another cell. However, it is difficult to speculate on the specific function of FrgA, since it lacks any homologues in the databases.

The frgA mutant appears to have some phenotypic similarities to the abcA mutant. The abcA gene was originally identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for genes that encode proteins that might interact with FrzZ, domain 1 (34). FrzZ is a protein of unknown function that is necessary for developmental aggregation; it contains two CheY-like domains joined by a linker (31). The abcA mutant displays normal directed-motility behaviors, unlike most frz mutants, but forms frizzy aggregates under starvation conditions. The frizzy phenotype of the abcA mutant is complemented extracellularly by mixing it with live cells or cell extracts of other strains of M. xanthus (34). This observation suggested that the abcA mutant is defective in producing extracellular signal molecules; when the signals are supplied extracellularly, the mutant is able to form normal fruiting bodies. The AbcA protein has been assigned a role as an ABC transporter because of its extensive homology with other known transporters (34). Therefore, it was suggested that the protein could be involved in the export of putative signal molecules. Cell-mixing experiments suggested that the production of the signal for frgA requires a functional abcA, implying a connection between FrgA and AbcA. It would be interesting to determine whether FrgA and AbcA are involved in the same or different signal production pathways. Although the frgA and abcA mutants have many similar phenotypes, they also show differences. For example, the abcA mutant in the strain DZ2 background showed wild-type swarming and development. In contrast, the frgA mutant showed reduced swarming and a weak frizzy phenotype in the same background. At this time we do not understand the basis for these differences.

The frgB and frgC genes are part of the same operon as frgA, encoding a histidine protein kinase and a response regulator, respectively. Null mutations in frgB or frgC did not cause any obvious developmental defects. However, the mutations did cause slightly earlier fruiting body formation compared to the wild type. frgB and frgC may indeed have a function related to frgA, but this function may not be apparent in the mutants because of pathway redundancies or crosstalk between different signaling proteins.

Is the signal generated in part by FrgA directly recognized by the Frz signal transduction system? Since the frgA mutant shows normal methylation of FrzCD, the signal generated by FrgA may not be required for early mound formation. Not all mutants blocked in early development showed altered FrzCD methylation; however, these mutants did not form frizzy aggregates (9). Therefore, it is still an open question whether the signal generated by FrgA is recognized by the Frz system. Cell-mixing experiment did provide some evidence for a connection between FrgA and the Frz system. The frz mutants failed to rescue the frizzy phenotype of the frgA mutant, indicating that the frz mutants did not produce the signal that is missing in the frgA mutant. Thus, it appears that the function of FrgA is dependent on the Frz signal transduction system. However, the function of the Frz system does not appear to be dependent on FrgA. The frgA mutant showed normal chemotactic responses, suggesting that the Frz system is functioning normally in the mutant.

The Frz signal transduction system plays an essential role during developmental aggregation in M. xanthus, and defects in this system result in the failure of fruiting body formation. It has been hypothesized that the Frz signal transduction system responds to self-generated signals for fruiting body formation. In this study, we have identified the frgA gene that appears to be involved in generating extracellular signal molecules which are essential for developmental aggregation. The signal molecules have yet to be identified. The frgA mutant provides a second locus, in addition to the previously identified gene, abcA, which can be used to screen for signal molecules using an extracellular complementation assay. The study of these two genes should also help us to understand the role of the Frz signal transduction pathway in controlling intercellular movements during fruiting body formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mandy J. Ward and other members of the Zusman laboratory for helpful discussions and suggestions.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM20509.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackhart B D, Zusman D R. “Frizzy” genes of Myxococcus xanthus are involved in control of frequency of reversal of gliding motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8767–8770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos J M, Zusman D R. Regulation of development in Myxococcus xanthus: effect of 3′:5′-cyclic AMP, ADP, and nutrition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:518–522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campos J M, Geisselsoder J, Zusman D R. Isolation of bacteriophage Mx4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1978;119:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y M, Backman K, Magasanik B. Characterization of a gene, glnL, the product of which is involved in the regulation of nitrogen utilization in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:214–220. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.1.214-220.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho K, Zusman D R. Sporulation timing in Myxococcus xanthus is controlled by the espAB locus. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:714–725. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downard J, Ramaswamy S V, Kil K-S. Identification of esg, a genetic locus involved in cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7762–7770. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7762-7770.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dworkin M, Kaiser D. Myxobacteria II. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng Y, Yang Z, Downard J, Zusman D, Shi W. Methylation of FrzCD defines a discrete step in the developmental program of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5765–5768. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5765-5768.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagen D C, Bretscher A P, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenetic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1978;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Genetics of gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus (Myxobacterales): two gene systems control movement. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;171:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashefi K, Hartzell P L. Genetic suppression and phenotypic masking of a Myxococcus xanthus frzF-defect. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:483–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufman, R. I., and B. T. Nixon. 1996. Use of PCR to isolate genes encoding ς54-dependent activators from diverse bacteria. 178:3967–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kuner J M, Kaiser D. Fruiting body morphogenesis in submerged cultures of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:458–461. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.458-461.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kustu S, North A K, Weiss D S. Prokaryotic transcriptional enhancers and enhancer-binding proteins. Trends Biosci. 1991;16:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90163-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride M J, Zusman D R. FrzCD, a methyl-accepting taxis protein from Myxococcus xanthus, shows modulation during fruiting body formation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4936–4940. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4936-4940.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride M J, Weinberg R A, Zusman D R. “Frizzy” aggregation genes of the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus show sequence similarities to the chemotaxis genes of enteric bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:424–428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCleary W R, Zusman D R. FrzE of Myxococcus xanthus is homologous to both CheA and CheY of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5898–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCleary W R, McBride M J, Zusman D R. Developmental sensory transduction in Myxococcus xanthus involves methylation and demethylation of FrzCD. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4877–4887. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4877-4887.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McVittie A, Zahler S A. Chemotaxis in Myxococcus. Nature. 1962;194:1299–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison C E, Zusman D R. Myxococcus xanthus mutants with temperature-sensitive, stage-specific defects: evidence for independent pathways in development. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:1036–1042. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.1036-1042.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ninfa A J, Magasanik B. Covalent modification of the glnG product, NRI, by the glnL product, NRII, regulates the transcription of the glnALG operon in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5909–5913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbluh A, Rosenberg E. Autocide AMI rescues development in dsg mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1513–1518. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1513-1518.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi W, Zusman D R. The two motility systems of Myxococcus xanthus show different selective advantages on various surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3378–3382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi W, Köhler T, Zusman D R. Chemotaxis plays a role in the social behaviour of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:601–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi W, Köhler T, Zusman D R. Motility and chemotaxis in Myxococcus xanthus. Methods Mol Genet. 1994;3:258–269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimkets L J. Social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:473–501. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.473-501.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimkets L J. Intercellular signaling during fruiting-body development of Myxococcus xanthus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:525–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoker K, Reijnders W N M, Oltmann L F, Stouthamer A H. Initial cloning and sequencing of hydHG, an operon homologous to ntrBC and regulating the labile hydrogenase activity in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4448–4456. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4448-4456.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trudeau K G, Ward M J, Zusman D R. Identification and characterization of FrzZ, a novel response regulator necessary for swarming and fruiting-body formation in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:645–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5521075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward M J, Zusman D R. Regulation of directed motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:885–893. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4261783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward M J, Lew H, Treuner-Lange A, Zusman D R. Regulation of motility behavior in Myxococcus xanthus may require an extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5668–5675. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5668-5675.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward M J, Mok K C, Astling D P, Lew H, Zusman D R. An ABC transporter plays a developmental aggregation role in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5697–5703. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5697-5703.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward M J, Zusman D R. Developmental aggregation and fruiting body formation in the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. In: Brun Y V, Shimkets L J, editors. Prokaryotic development. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2000. pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zusman D R. “Frizzy” mutants: a new class of aggregation-defective developmental mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:1430–1437. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1430-1437.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]