Abstract

Transitioning out of elite sports can be a challenging time for athletes. To illuminate the gaps and opportunities in existing support systems and better understand which initiatives may have the greatest benefit in supporting athletes to transition out of elite sport, this study examined the lived experience of retired elite Australian athletes. Using a sequential mixed-methods approach, quantitative data were collected via a self-report online survey, while qualitative data were collected via semistructured interviews. In total 102 retired high-performance athletes (M=27.35, SD=7.25 years) who competed in an Olympic or Paralympic recognised sport at the national and/or international-level participated in the online survey, providing data across domains of well-being and athletic retirement. Eleven survey respondents opted in for the semistructured interview (M=28.9, SD=6.9 years) providing in-depth responses on their retirement experiences. Using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), latent variables were identified from the survey data and associations between retirement support, retirement difficulties, retirement experiences, well-being and mental health were determined. Interview data were thematically analysed. The structural model had good predictive validity for all nine latent variables, describing positive and negative associations of retirement experiences, mental health and well-being. Building an identity outside of sport, planning for retirement, and having adaptive coping strategies positively impacted retirement experiences. Feeling behind in a life stage and an abrupt loss of athletic identity had a negative impact on retirement experiences. Implications for sports policymakers are discussed, including support strategies that could better assist athletes in successfully transitioning from elite sports.

Keywords: Well-being, Risk factor, Mental, Health promotion, Athlete

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Athletes should be prepared for and supported through retirement.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Our findings have increased the understanding of the specific challenges and the potential strategies to maximise preparation for a successful retirement, which can guide sporting bodies as to the areas of greatest need or potential for improvement within existing support systems.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Sport policymakers might consider providing personalised and tailored retirement planning that actively engages athletes, commencing retirement preparation early in the athlete’s career, focusing on building multiple domains of self and providing clarity and agreement as to the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of all sport stakeholders to deliver a tailored support framework.

Introduction

The transition out of competitive sport is a dynamic process that may evolve over months or even years.1 Transitioning from competitive sport is a period of vulnerability for athletes characterised by complex and multifaceted changes in lifestyle, social, psychological and vocational domains.2 3 Retired athletes report emptiness, loss, grief and a decreased sense of purpose during this significant life change, with retirement a major risk factor for the onset of mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse and eating disorders.3–5 Given the well-known risks of transitioning out of elite sports, there is enormous scope for programmes to promote the well-being of retired athletes.6 Indeed, the recent Evidence-Informed Framework to Promote Mental Well-being in Elite Sport advocates that athletes should be prepared for and supported through retirement and that sporting bodies should equip athletes with the skills and resources required to transition out of the elite sporting environment while maintaining mental health and well-being.7

Research has revealed that preretirement interventions that address psychological, social, academic and vocational factors can support athletes to adjust to life after competitive sport.8 Postretirement planning that includes developing identities in non-athletic domains, such as pursuing a career/vocation, education or recreational activities, can enhance athlete well-being and well-being into retirement.9 10 Similarly, developing coping strategies such as help-seeking behaviours and psychosocial support from family, friends and coaches, enhances feelings of closeness in relationships through self-disclosure and creates shared narratives that can improve mental health and well-being.11 Notwithstanding this knowledge base, understanding what factors contribute to the mental health and psychological well-being of elite athletes in retirement is essential to developing support services for athletes as they transition out of sport.

There is a strong need for researchers and professionals working in elite sports to identify, understand and promote factors associated with positive outcomes of sporting retirement to lessen the significant challenges athletes encounter. More is known about the factors that increase the risk of a poor transition out of competitive sport or the risks of poor mental health and well-being, with relatively little exploration of positive factors in comparison. This present study investigated the lived experience of retired elite Australian athletes to better understand the specific challenges and the potential strategies required to maximise preparation for a successful retirement. Specifically, this study aimed to (1) examine the circumstances under which athletes retired and their satisfaction with retirement support systems and (2) examine the key factors and support system parameters for athletes to successfully transition from elite sports.

Methods

Study design and procedure

The authors’ acknowledge from an ontological perspective that social phenomena exist on a spectrum between objective and subjective concepts of reality.12 From an epistemological perspective, pragmatism asserts that the value and meaning of opinions and ‘facts’ captured in research data are assessed by examining their practical consequences in specific contexts.13 In accordance with this philosophical position, the authors adopted a sequential mixed-methods approach.14 The quantitative phase allowed us to collect data from many athletes across many measures (to identify trends and comparative analyses). The qualitative phase provided the opportunity to enhance our understanding and contextualise the relevance/ importance of key findings. We synthesised qualitative descriptions of athlete retirement circumstances and experiences with quantitative ratings of athlete perceptions of retirement supports to develop a comprehensive account of the key factors and support system parameters for athletes to successfully transition from elite sport.

Quantitative data were collected via a self-report online survey of approximately 40 min duration. The survey was developed in consultation with the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) Athlete Well-being and Engagement (AW&E) team. In addition to key demographic questions, the survey included a range of reliable and valid standardised measures (see online supplemental file). The AW&E managers embedded in national sporting organisations promoted the survey, inviting athletes who had retired within the last 6 years (ie, 2013–2018) to participate. A link to the anonymous survey was provided to the athletes via email. The survey was open for 9 months (April 2019 to January 2020). Participants provided informed consent online. A debriefing statement outlining support services was provided to participants.

bmjsem-2024-001991supp001.pdf (71KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2024-001991supp002.pdf (79.2KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2024-001991supp003.pdf (64.6KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2024-001991supp004.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)

Qualitative data were collected via in-depth semistructured interviews, with participants opting for this process at the end of the online survey. Written informed and verbal consent was obtained before the interviews via telephone/Skype/Zoom. The 1-hour interview focused on personal experiences of seeking formal and informal support in preparing for retirement, exploration of multiple roles and the strength of their current athletic identity, recommendations for appropriate support services and preretirement planning, and barriers and enablers to accessing well-being and engagement services that were available at the time (see online supplemental appendix A). After each interview, participants were advised about available support services.

This research study was approved by the Victoria University Human Ethics Research Committee (HRE19-022).

Participants

Individuals aged 18 years or older who had retired from elite sport within the last 6 years were invited to participate. An elite athlete was defined as a high-performance athlete competing in an Olympic or Paralympic-recognised sport at the national and/or international level. A total of 102 retired athletes commenced the survey, and 53 (52%) completed the entire set of measures. The sample represented 27 sports, with the greatest representation being sailing (15%), rowing (13%), swimming (11%), cycling (10%) and basketball (6%).

Eleven retired Australian elite athletes who completed the survey also opted in and participated in the semistructured interview. Interviews were conducted via telephone (n=9) and online (n=2) due to location differences.

Measures

Quantitative data collection

The quantitative survey instrument created on the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) included key measures that addressed five core aspects of athletic retirement as identified from the literature and reported in the introduction: retirement support, retirement difficulties, retirement experiences, psychological well-being and psychological distress.

Retirement support

Measured using the 8-item self-report subscale of the Athlete Retirement Questionnaire (ARQ),15 participants rated the support received from interpersonal and institutional support sources from very little (1) to very much (5). Sources of support included (A) social (comprised of items 1. family, 2. Friends and 3. spouse/partner), (B) sports teams (comprised of items 4. teammates and 6. coaches) and (C) sports organisations (comprised of items 5. local clubs, 7. state associations and 8. national sports organisations).

Retirement difficulties

Measured using the 11-item self-report subscale from the ARQ,15 participants self-reported difficulties that could be encountered during their retirement transition. They rated these from no problem (1) to a big problem (5). Retirement difficulties were divided into those related to their identity (eg, missing social aspect of sport, loss of (elite athlete) status, feeling incompetent in activities other than sport, lack of confidence) and life stresses (eg, job/school pressures, relationship difficulties with family/friends, personal illness (physical/ mental)).

Retirement experiences

Measured using the Retirement Experiences Questionnaire,16 a 10-item validated scale measuring enjoyable and negative experiences during retirement.16 Participants rated their perceptions of positive and negative retirement experiences from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4).

Psychological well-being

Measured using the Flourishing Scale,17 a validated 8-item self-report summary measure of psychological well-being (Cronbach’s α=0.87).18 Participants rated each item from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Psychological distress

Measured using Kessler’s K10 scale,19 a validated 10-item self-report global measure of psychological distress that assesses a range of symptoms (eg, feeling depressed, feeling nervous) experienced over the past 30 days on a scale from none of the time (1) to all of the time (5) with total scores ranging from 10 to 50 (Cronbach’s α=0.91).20

Qualitative data collection

Current literature on athlete retirement as described in the introduction was utilised as a starting point to formulate questions, and representatives from the AIS AW&E programme provided feedback. The interviews facilitated an in-depth exploration of personal experiences of seeking formal and informal support in preparing for retirement, the strength of their current athletic identity, recommendations for appropriate support services and preretirement planning and barriers and enablers to accessing well-being and engagement services. The full interview schedule can be viewed in the online supplemental files.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Data analysis was conducted in R (V.4.2). The data were checked for missingness using the naniar package21 (28.2% of values were missing and data were missing completely at random, x 2(41)=43.9, p=0.351). Missing values were handled using arithmetic mean imputation.22

Associations of retired athletes’ retirement experiences, mental health and well-being were examined using PLS-SEM using the SEMinR package.23

First, a measurement model was estimated. Retirement support from friends and family, sports teams and sports organisations; life stresses retirement difficulties; and positive and negative retirement experiences were defined as formative latent variables,24 while identity retirement difficulties; psychological well-being and psychological distress were defined as reflective latent variables. The recommendations for evaluating measurement models suggested by Hair et al 25 were used. The initial measurement model was modified, so factors that had a loading of less than 0.5 were removed from latent variables if the latent variable displayed inadequate internal consistency (rhoA<0.7) or convergent validity (average variance extracted (AVE)<0.50).

Next, a theorised structural model was estimated. The model estimated the associations between retirement support, retirement difficulties, retirement experiences, well-being and mental health. The model’s explanatory power was assessed using R2, and the predictive power was assessed using the root mean square error (RMSE). The RSME was estimated using k=4 and 10 repetitions. The RMSE from the structural model was compared with a naïve linear regression benchmark.25 The variance inflation factors from the final structural model were inspected to ensure that there were no multicollinearity issues. Bootstrapping with 10 000 resamples was used to calculate all estimated paths’ 95% CIs. Paths were considered statistically significant if their 95% CI did not straddle zero.

Power calculation

Partial least squares SEM uses an iterative approach to analysing the data, and, therefore, it is suggested that the sample size should be greater than 10 times the maximum number of inner or outer model links pointing at any latent variable in the model to achieve reliable results (a minimum sample size of 30 participants would be required for the current model). The study was sufficiently powered to determine a small-to-moderate relationship (r2=0.08) for the tested paths.26

Qualitative data

Interview data were analysed using thematic analysis (TA).27 TA was the chosen analytical method to identify themes across the qualitative data set by analysing individual experiences and uncovering patterns in participants’ lived experiences.28 As Braun et al 28 indicated, this design decision was informed by identifying patterns across a data set with a large sample size of 11.

Interview transcripts were read and reread while listening to the audio recordings by the process of familiarisation. The next phase involved coding, in which one researcher (CS) closely read the data and tagged a code for each piece that had some relevance to the research question using NVivo software. After initial codes were generated, data were reduced into smaller chunks of meaning for theme development to uncover overarching themes, themes and subthemes. An inductive approach was used to thematically group the codes into categories where the content itself guided the developing analysis. Categories were reviewed, modified and developed into themes to explain the phenomenon.27

Descriptive validity (eg, interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim) and theoretical validity (eg, the researchers met and discussed each code in relation to the theory) were used to guarantee the rigour of the results.27 Two researchers (CLB, AP) acted as ‘critical friends’ to the researcher (CS) who primarily engaged the qualitative data analysis. This practice served to provide oversight of the study and encouraged researcher reflexivity at a personal level (eg, acknowledging researcher subjectivity and biases) and an interpersonal level (eg, considering any interplay between researchers and participants) as well as exploration of alternative data interpretations.29 30

Results

Quantitative data

Descriptive Statistics

Overall, 102 retired athletes participated in this study and were included in the PLS-SEM analysis. Sample descriptive statistics are displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of survey respondents

| Variable | N (%) |

| Age (years) M (SD) | 27.35 (7.25) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 40 (39.2%) |

| Female | 60 (58.8%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (2.0%) |

| Children | |

| No children | 86 (84.3%) |

| One child | 8 (7.8%) |

| Multiple children | 8 (7.8%) |

| Sport category | |

| Olympic-sport athlete | 97 (95.1%) |

| Para-sport athlete | 4 (3.9%) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.0%) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 94 (92.2%) |

| Bisexual | 3 (2.9%) |

| Homosexual | 2 (2.0%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (1.0%) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (2.0%) |

| Country of birth | |

| Born in Australia | 93 (91.2%) |

| Born overseas | 8 (7.8%) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.0%) |

| Study/employment status | |

| Working full time | 43 (42.2%) |

| Working part time/casual | 16 (15.7%) |

| Studying full time | 32 (31.4%) |

| Studying part time | 6 (5.9%) |

| Other | 5 (4.9%) |

| Time since retirement | |

| 0–12 months | 16 (15.7%) |

| 1–2 years | 19 (18.6%) |

| 2–3 years | 17 (16.7%) |

| 3–4 years | 14 (13.7%) |

| 4–5 years | 7 (6.9%) |

| 5–6 years | 5 (4.9%) |

| 6+ years | 10 (9.8%) |

| Not reported | 14 (13.7%) |

| Living situation | |

| Living in family home (eg, parent’s home) | 34 (33.3%) |

| Renting | 28 (27.5%) |

| Own a home | 31 (30.4%) |

| Other | 8 (7.9%) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.0%) |

| Retirement experiences and well-being | |

| Retirement support friends and family M(SD)* | 3.54 (0.95) |

| Retirement support sport M(SD)* | 2.55 (1.07) |

| Retirement support sporting organisation M(SD)* | 1.67 (0.91) |

| Retirement difficulties – identity M(SD)† | 3.05 (1.14) |

| Retirement difficulties—life stresses M(SD)† | 2.26 (1.02) |

| Positive retirement experiences M(SD) | 15.88 (2.75) |

| Negative retirement experiences M(SD) | 11.45 (3.05) |

| Psychological well-being M(SD) | 45.63 (8.87) |

| Psychological distress M(SD) | 18.49 (8.12) |

For a list of the sports represented, see online supplemental appendix B.

*1 = very little support, 5 = very much support.

†1 = no problem, 5 = big problem.

Measurement model

Items with low loadings were removed from the original measurement model for positive retirement experiences, negative retirement experiences and life-stress retirement difficulties. In the final modified model, all variables had acceptable internal consistency (rhoc>0.7) and convergent validity (AVE>0.5). An overview of the internal consistency and convergent validity of each of the latent variables and the items that were removed from each latent variable are seen in online supplemental appendix C of the supplementary files.

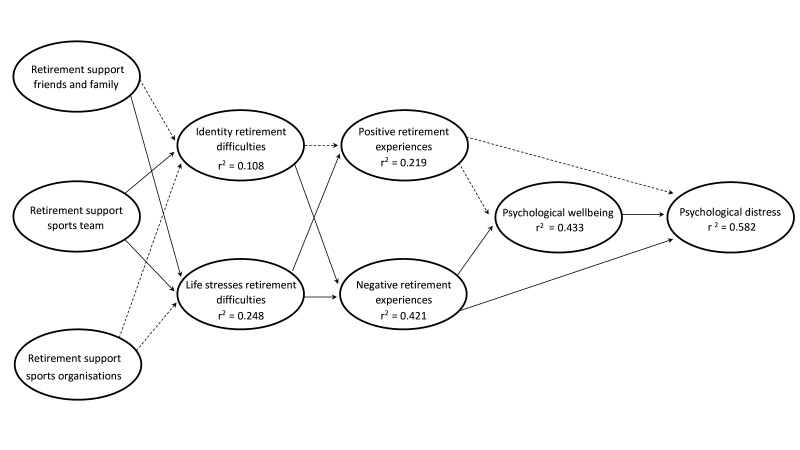

Structural model

The theorised structural model with the R2 value for each variable is displayed in figure 1. Coefficients for each of the paths are displayed in table 2. Results show that support from sporting teams was related to lower identity retirement difficulties. Support from friends and family and support from sports teams was related to lower life stresses and retirement difficulties. Support from sporting organisations was not related to retirement difficulties. In turn, identity difficulties were related to more negative retirement experiences, while life stresses were related to less positive and more negative retirement experiences. Negative retirement experiences were inversely related to psychological well-being and positively related to psychological distress, while positive retirement experiences were not related to psychological well-being or distress. Finally, psychological well-being was related to lower levels of psychological distress.

Figure 1.

Hypothesised structural model linking retirement support, retirement difficulties, retirement experience, psychological well-being and psychological distress. Dashed lines indicate the structural path was not significant.

Table 2.

Overview of structural model paths

| Path | B | 95% CI bootstrap |

| Retirement support friends and family → identity retirement difficulties identity | −0.055 | −0.31 to 0.14 |

| Retirement support friends and family → life stresses retirement difficulties | −0.354 | −0.58 to –0.12 |

| Retirement support team → identity retirement difficulties | −0.322 | −0.54 to –0.07 |

| Retirement support team → life stresses retirement difficulties | −0.266 | −0.45 to –0.03 |

| Retirement support sports organisations → identity retirement difficulties identity | 0.080 | −0.17 to 0.27 |

| Retirement support sports organisations → life stresses retirement | 0.045 | −0.20 to 0.24 |

| Identity retirement difficulties identity → positive retirement experiences | −0.126 | −0.4 to 0.11 |

| Life stresses retirement difficulties → positive retirement experiences | −0.391 | −0.64 to –0.1 |

| Identify retirement difficulties → negative retirement experiences | 0.469 | 0.31 to 0.62 |

| Life stresses retirement difficulties → negative retirement experiences | 0.269 | 0.07 to 0.48 |

| Positive retirement experiences → psychological well-being | 0.172 | −0.05 to 0.45 |

| Negative Retirement experiences → psychological well-being | −0.544 | −0.71 to –0.33 |

| Positive retirement experiences → psychological distress | −0.006 | −0.21 to 0.21 |

| Negative retirement experiences → psychological distress | 0.422 | 0.20 to 0.62 |

| Psychological well-being → psychological distress | −0.415 | −0.65 to –0.19 |

Overall, the hypothesised associations explained 10.8% and 24.8% of the variation in identity and life stress-related difficulties, respectively. Associations explained 21.9% and 42.1% of the variation in positive and negative retirement experiences, 43.3% of the variation in psychological well-being and 58.2% of the variation in psychological distress. The RMSE for the structural model and naïve linear regression benchmark are displayed in online supplemental appendix D. Results showed that the structural model had good predictive validity for all latent variables.

Qualitative data

Participant profiles

Table 3 reports the participants’ gender, age and years since retirement from an elite sporting career. The primary sports of the participants included cycling, rowing, soccer, hockey, skating and swimming.

Table 3.

Retired elite athlete participant information (17–37 years at time of retirement, M=28.9, SD=6.9)

| Retired Elite-Athlete (REA) | Gender | Age at retirement (years) | Years since retirement |

| REA 1 | Female | 33 | 5 years |

| REA 2 | Female | 35 | 2 years |

| REA 3 | Female | 17 | 1 year |

| REA 4 | Male | 31 | 2 years |

| REA 5 | Male | 19 | 1 year |

| REA 6 | Female | 37 | 1 year |

| REA 7 | Female | 31 | 3 years |

| REA 8 | Male | 26 | 4 years |

| REA 9 | Male | 32 | 2 years |

| REA10 | Female | 22 | 2 weeks |

| REA 11 | Male | 35 | 3 years |

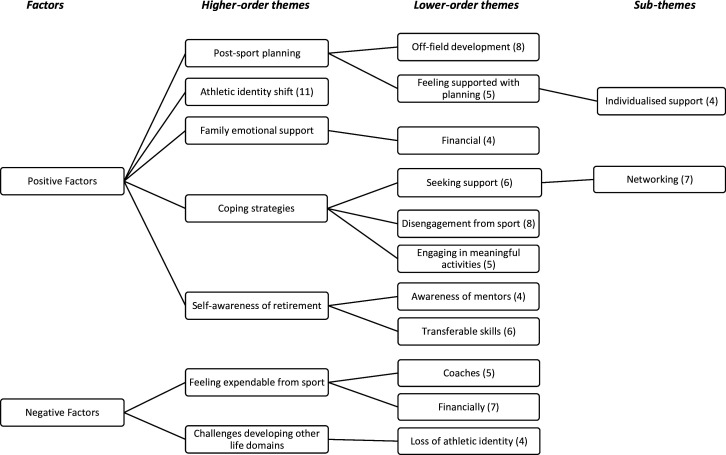

Thematic analysis

TA of the 11 semistructured interviews identified themes relating to positive and negative factors impacting retirement experiences (figure 2). Quotes describing retired athletes’ emergent themes from interview transcripts are presented in table 4.

Figure 2.

Retired athlete emergent themes from interview transcripts. Parenthesis refer to number of participants cited. All of the participants reported a good quality of life and flourishing following retirement from sport, however, the depth of data was not sufficient for this to be included as a discrete theme.

Table 4.

Quotes describing retired athlete emergent themes from interview transcripts

| Theme | Supporting quote |

| Post-sport planning | ‘I was invested in my study whilst I was still [in sport), you know, you always need that backup…’ (REA3) ‘…when I retired, I had other things to do. I had uni. I had a job’ (REA10) ‘I think that’s when sport’s looking at post-retirement pathways, that actually has to be the focus. You know, it’s great to say, “We offer all these things,” but when they're blanket-style approaches, are you really offering something that’s effective? So I think an individual focus would actually provide a lot of individuals with at least a degree of structure maybe for when they leave their sport….’ (REA11) |

| Athletic identity shift | ‘…you kind of become really comfortable with, essentially not a new identity but, maybe just a slightly new identity as an employee, as a father, or as a, ex [athlete)…’ (REA11) ‘…I just think the most important thing is that self-awareness and that attitude toward, and your opinion of yourself, that you're not an athlete. You're someone else as well. You're the person first, and you perform as an athlete, but you're a person without having to be, you know, that athlete 24/7, and to give yourself a break sometimes, but, yeah, I think that’s sort of just the most important thing that I probably took from my career, and the biggest thing that I learned that I was good at was just knowing myself and knowing who I was before I was an athlete’ (REA2) |

| Family emotional support | ‘…you know, just having people you can talk to. As I've said, my wife is wonderful. You know, she allows me the opportunity to be able to vent and to express frustration, and she appreciates that she can't solve any of that. But quite often just to have it out in the world, is a really good thing, you know’ (REA11) |

| Coping strategies | ‘So I wasn't just moping around in my room all day. So you know, after I quit, me and my friends, we all went camping and stuff like that. And then uni kept my mind busy. I was always just doing stuff, which I think helped. If I didn't, if I just stayed around and did nothing-- because one thing I noticed, as soon as I quit, you have so much free time on your hands… And you're like, “What do I do?” So and if you keep busy and don't just, you know, lounge around in the free time that you've got, then I think you'll adjust better’ (REA5). |

| Self-awareness of retirement | ‘Look, hindsight it’s a wonderful thing, you know? Like I really wish that I'd completed a uni degree in construction management. I'd be a lot better off than I am currently, which is why I've gone back to, to just do the diploma…you know, you need to plan for it. You need to do all this sort of stuff, and that’s something that’s-- I don't think-- I wish I knew’ (REA9) ‘I think having gone through it (…) having athletes that have successfully transitioned out to go and, I guess, share their experiences in retiring is probably the best way to, I guess, educate athletes on transitioning through because nothing, like I said, nothing can prepare you for it’ (REA7) |

| Feeling expendable from the sport | ‘…then, once that decision was made, there was-- you know, to be honest, there was no support from anyone. It was purely you're cast out and you gotta fend for yourself now. I even-- they even made me write my own press release. They didn't even write it’ (REA7) ‘…there was no formal follow up with any team doctors or any physios or anyone following my return from Europe. It was left to my own devices’ (REA11) |

| Challenges with other life domains | ‘I remember going to my 10-year high school graduation and everyone else from school was either married or with kids and had a mortgage because they'd been to uni. So I was like, “Wow, that’s cool. You guys are like doing what you're meant to be doing at this time of life.” And I was like, “I've got none of that”’ (REA1) ‘It’s a weird feeling not having a thing that defined you, not having that anymore. Yeah, there’s definitely a lot of grief and loss, big part of me. Almost like a bad breakup…’ (REA5). |

Post-sport planning

Participants discussed the benefit of expanding their interests outside of sports as a positive way to channel their athlete identity into other life domains. Investing in off-field development such as establishing a vocational domain, and feeling supported by sport to cultivate other life domains through individualised support that addresses challenges associated with post-sport planning, were key contributors to a positive retirement experience.

Athletic identity shift

All of the participants shared challenges with shifting from an athletic identity to other domains of their identity outside of sport. Athletes who could redefine their sense of self to focus on interpersonal domains, such as family, created a sense of competence and positive self-regard. Those athletes that could shift from one dominating sense of self (athlete) to another (non-athlete, eg, parent) highlight the importance of a complementary, holistic view of self, or multiple domains of identity, before and throughout an elite sporting career.

Family emotional support

Participants described the support they received from close family members (ie, parents and/or a partner/spouse) as positively impacting their retirement experiences, particularly if retirement was unplanned. Family support to ease financial pressures and their willingness and availability to discuss retirement difficulties was considered valuable and important support.

Coping strategies

Athletes who could engage in help-seeking behaviour and source support (ie, psychologist support or career assistance) seemed to have a more positive experience with their retirement. Seeking support through their sporting network (ie, a combination of former teammates, peers and high-performance staff) assisted with employment after sport and fewer athletes who did this reported difficulties during retirement. Disengagement or withdrawal from the sporting club/programme immediately after retirement seemed to facilitate a more positive transition into other life areas and engaging in meaningful activities as a coping strategy for managing difficult emotions.

Self-awareness of retirement

Awareness of the need to plan for and the importance of recognising the inevitability of retirement was a common theme. Specific types of support that may facilitate this included the role of mentors in building their awareness for retirement planning due to the mutual understanding between people who had been through similar experiences. Drawing on skills (ie, determination, hard work) learnt in sports and how to transfer these into other life domains was a positive factor in retirement.

Feeling expendable from the sport

The majority of participants felt devalued from their sporting organisation during retirement. This feeling of expendability arose immediately on retirement and continued months into retirement. Having no official contact, follow-up, or offers of support—including financial support for medical costs—from their sporting organisations, influenced athletes’ perceptions of their retirement experience. A disconnect between the athlete’s perception of support and how the organisations offer support initially and during retirement was identified. Some participants felt unsupported by coaches, that coaches focused on their role during the end of the season or after major competition, rather than considering the needs and well-being of the athletes.

Challenges with other life domains

Participants perceived various challenges in comparing the development of their life domains to that of their non-sporting peers. Most participants had a strong athletic identity, and some described difficulty dealing with the apparent loss of their athletic life domain or elite status.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore athletes’ satisfaction with retirement support systems and examine key factors and system parameters to optimise support transition from elite sport while maintaining mental health and well-being. Our findings complement the framework proposed by Purcell et al 7 on promoting mental well-being in elite sports by providing important evidence on elite athletes’ retirement experiences, which better informs sports on resource allocation and programme planning. In the quantitative phase, better retirement experiences were associated with having more support from sporting teams, friends and family, fewer life stressors and identified difficulties. Negative retirement experiences were associated with worse mental health and well-being. In the qualitative phase, building an identity outside of sport, planning for retirement and developing coping strategies positively impacted retirement experiences. On the other hand, feeling behind in a life stage and an abrupt loss of athletic identity had a negative impact on retirement experiences.

Factors contributing to positive retirement outcomes

Athletic identity and planning

While both the quantitative and qualitative phases of this study found that identity difficulties were related to more negative retirement experiences, the qualitative phase strengthened and complemented this by identifying tangible ways in which athletes could develop multiple domains of identity throughout an elite sporting career, including feeling supported by their sport to cultivate other life domains. Therefore, supported planning for retirement may mediate the strength and impact of the athlete’s identity.

Coping strategies

Our quantitative and qualitative findings identifying the value of social support in contributing to a more positive retirement experience are consistent with earlier research, showing that athletes adjusted well to life after sport when they sought support from family and friends to manage emotions.3 31 Given stigma is a major deterrent to help-seeking behaviour in sports,32 33 sporting bodies and organisations should continue to work towards normalising mental health concerns to encourage help-seeking behaviour.34 In addition, support through mentors can enhance athlete awareness of the importance of retirement planning, as mentors can offer a mutual understanding of retirement issues and concerns, provide comfort and familiarity35 and assist with the development of identities outside of sport.36 It is, therefore, beneficial that structured and unstructured support be available to athletes during the various phases of retirement.

Previous research states that staying involved in sports after retirement is important for successful adjustment by maintaining social connections,37 and our findings support this. While disengagement from sport immediately postretirement was used to manage distress, exercising for self-care and keeping in touch with sports-related friends were still strongly associated with positive retirement experiences. Therefore, clear communication and planning for athletes to stay involved with clubs and/or sporting organisations might support a more positive experience for retiring athletes.

Factors contributing to negative retirement outcomes

Perceived challenges with developing life domains

Our qualitative finding was that retired athletes who felt they were behind in a particular life stage resulting from their commitment to sport perceived this as having a negative impact on their mental health and well-being. Thus, it indicates that the concomitant development of other life domains and identities outside of elite competitive sports is important to reduce a sense of inadequacy of competence in things other than sports.

Support from sport

The quantitative phase of the study found that few participants felt supported by the sporting organisations or sporting teams, and both the path analysis and qualitative phase of the study complemented one another by indicating the importance of support from coaches in particular. We propose that structured and unstructured supports provided by sports bodies should aim to strengthen both emotion-focused and problem-focused approaches to coping as identified by.38

Our finding that athletes reported not knowing who is responsible for managing and supporting them at different stages of the transition out of competitive sport indicates that sporting organisations should incorporate support to increase knowledge and build skills to prepare and plan for life after competitive sport.39

The recent Framework to promote mental well-being in elite sports advocates that athletes should be prepared and supported for key sport-related transitions. Our current findings go beyond this by identifying that a tailored retirement support framework and clear guidance for athletes regarding who is responsible for managing and supporting them at different stages of the transition out of competitive sport would be beneficial in mitigating the negative retirement experiences reported in this study (Note: At the time of publication, the AIS and wider Australian high performance system have developed and implemented further strategies to better support retiring athletes. These include the AIS Career Practitioners Referral Network for individualised support on career development and planning, and individual support for current athletes to continue their education and complete work internships while competing; the AIS Athlete Accelerate programme to support retired woman athletes who wanted to pursue a career in high-performance sport; several community engagement programmes to assist athletes to further develop their identities by contributing to community programmes that aligned with their values; continued funding for athletes in their first year of retirement from elite sport and continued access to mental health services during retirement through the AIS Mental Health Referral Network).

Practical implications

Based on our key findings, the following practical considerations are offered to sports policymakers to enhance support services for athlete preretirement planning and strategies to improve accessibility to well-being and engagement services:

Provide personalised and tailored retirement planning that actively engages athletes.

Retirement preparation should commence early in the athlete’s career and focus on building multiple domains of self. Support that focuses on psychological preparation for the loss of athletic identity, elite status, a sense of purpose and routine may assist in mitigating feelings of inadequacy in other life domains.

Access to (sports) psychology, career development and mentoring from those with a shared understanding are key support components.

Associations of current psychological distress and psychological well-being are adaptable, and prospectively addressing these with the provision of specific programmes should be considered. These include enhancing social connections and support as well as help-seeking behaviours.

Provide clarity and agreement on all sport stakeholders’ roles, responsibilities and accountabilities to deliver a tailored support framework to manage the transition from competitive sport. This includes critical reflection on the contribution of sporting organisations, high-performance staff and coaches to retired athletes’ perceptions of feeling devalued, expendable and unsupported.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

Our combined results of path analyses with individual athlete descriptions of retirement experiences have enabled a deeper understanding of athletes’ experiences of existing support systems and the sort of support that might benefit athletes most. Despite the survey and interview samples reflecting a variety of sports, differing stages of retirement and different genders and ages, additional demographic information such as length of time as an elite athlete and sport type (ie, individual or team sport) was not gathered. As such, it was impossible to ascertain from these samples the differences or similarities between the length of elite athletic career, sports discipline, competitive experience or the impact of retirement at different ages on the retirement process. A comparative study of athletes across the high-performance continuum could provide such insights. In addition, a longitudinal approach to exploring different retirement stages and when support is required would provide additional knowledge on how athletes adapt to life after sport. Further research could also identify organisational structures that could be developed to support and enhance this retirement transition. Additionally, to determine possible factors specific to para-sport athletes and enable appropriate support, the experiences of Paralympic athletes should be explored. Finally, the transferability of the findings to environments in countries other than Australia is unknown.

Conclusion

Our findings have increased the understanding of the specific challenges and the potential strategies to maximise preparation for successful retirement. This can guide sporting bodies to the areas of greatest need or potential for improvement within existing support systems. Our findings are important as they can inform decisions around resource allocation and programme planning. This knowledge can be used to develop and implement physical and mental health, employment, education and well-being programmes for elite athletes transitioning out of competitive sports to increase the likelihood of positive retirement experiences.

Acknowledgments

We kindly thank Mr Matt Butterworth (Mental Health Manager) and Ms Christine Higgisson (Personal Development Adviser) from the Australian Institute of Sport for reviewing the manuscript and providing feedback on the implications of the findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: CLB: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualisation, supervision; CS: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualisation; MB: formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, visualisation; MP: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; MC: conceptualisation, methodology, writing—review and editing; AP: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualisation, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors guarantee the accuracy of the data and reviewed the manuscript. CLB serves as the guarantor of the work, accepting full responsibility for the work, the conduct of the study, the integrity of the data, and the decision to publish.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Institute of Sport, Canberra, Australia.

Competing interests: MC is employed by the Australian Institute of Sport, which is funded by the Australian Sports Commission.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Victoria University Human Ethics Research Committee (HRE19-022). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Taylor J, Ogilvie B. Career termination among athletes: is there life after sports? In: Singer RN, Hausenblas HA, Janelle CM, eds. Handbook of sport psychology. New York: Wiley, 2001: 672–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Souter G, Lewis R, Serrant L. Mental health and elite sport: a narrative review. Sports Med - Open 2018;4:57. 10.1186/s40798-018-0175-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown CJ, Webb TL, Robinson MA, et al. Athletes’ retirement from elite sport: a qualitative study of parents and partners’ experiences. Psychol Sport Exerc 2019;40:51–60. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gouttebarge V, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gorczynski P, et al. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:700–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cosh SM, McNeil DG, Tully PJ. Poor mental health outcomes in crisis transitions: an examination of retired athletes accounting of crisis transition experiences in a cultural context. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2021;13:604–23. 10.1080/2159676X.2020.1765852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rice SM, Purcell R, De Silva S, et al. The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review. sports medicine. Sports Med 2016;46:1333–53. 10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Purcell R, Pilkington V, Carberry S, et al. An evidence-informed framework to promote mental wellbeing in elite sport. Front Psychol 2022;13:780359. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.780359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wylleman P. An organizational perspective on applied sport psychology in elite sport. Psychol Sport Exerc 2019;42:89–99. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bennie A, Walton CC, O’Connor D, et al. Exploring the experiences and well-being of Australian Rio Olympians during the post-Olympic phase: a qualitative study. Front Psychol 2021;12:685322. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Debois N, Ledon A, Wylleman P. A lifespan perspective on the dual career of elite male athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc 2015;21:15–26. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown CJ, Webb TL, Robinson MA, et al. Athletes' experiences of social support during their transition out of elite sport: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Psychol Sport Exerc 2018;36:71–80. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgan G, Smircich L. The case for qualitative research. AMR 1980;5:491–500. 10.5465/amr.1980.4288947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelly LM, Cordeiro M. Three principles of pragmatism for research on organizational processes. Methodol Innov 2020;13:205979912093724. 10.1177/2059799120937242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Creswell JW, et al. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Sage Publishing: CA, 2003: 209–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sinclair DA, Orlick T. Positive transitions from high-performance sport. Sport Psychol 1993;7:138–50. 10.1123/tsp.7.2.138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robinson OC, Demetre JD, Corney R. Personality and retirement: exploring the links between the big five personality traits, reasons for retirement and the experience of being retired. Pers Individ Dif 2010;48:792–7. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res 2010;97:143–56. 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hone L, Jarden A, Schofield G. Psychometric properties of the flourishing scale in a new Zealand sample. Soc Indic Res 2014;119:1031–45. 10.1007/s11205-013-0501-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/s0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rice S, Walton CC, Pilkington V, et al. Psychological safety in elite sport settings: a psychometric study of the sport psychological safety inventory. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2022;8:e001251. 10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tierney N, Cook D, McBain M, et al. naniar: data structures, summaries, and visualisations for missing data. 2021. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/naniar/index.html

- 22. Kock N. Single missing data imputation in PLS-based structural equation modeling. J Mod Appl Stat Methods 2018;17:eP2712. 10.22237/jmasm/1525133160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ray S, Danks NP, Calero Valdez A, et al. seminr: building and estimating structural equation models. 2022. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/seminr/index.html

- 24. Bollen KA, Diamantopoulos A. In defense of causal-formative indicators: a minority report. Psychol Methods 2017;22:581–96. 10.1037/met0000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, et al. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook.2021. Available: 10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_1#DOI [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aguirre-Urreta M, Rönkkö M. Sample size determination and statistical power analysis in PLS using R: an annotated tutorial. CAIS 2015;36:33–51. 10.17705/1CAIS.03603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC, eds. Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise. London: Routledge, 2016: 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Olmos-Vega FM, Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L, et al. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide no. 149. Med Teach 2023;45:241–51. 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith B, McGannon KR. Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2018;11:101–21. 10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haslam C, Lam BCP, Yang J, et al. When the final whistle blows: social identity pathways support mental health and life satisfaction after retirement from competitive sport. Psychol Sport Exerc 2021;57:102049. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Barriers and Facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:157. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacIntyre TE, Jones M, Brewer BW, et al. Editorial: mental health challenges in elite sport: balancing risk with reward. Front Psychol 2017;8:1892. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moesch K, Kenttä G, Kleinert J, et al. FEPSAC position statement: mental health disorders in elite athletes and models of service provision. Psychol Sport Exerc 2018;38:61–71. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Young JA, Pearce AJ, Kane R, et al. Leaving the professional tennis circuit: exploratory study of experiences and reactions from elite female athletes. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:477–82; . 10.1136/bjsm.2005.023341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pink M, Saunders J, Stynes J. Reconciling the maintenance of on-field success with off-field player development: a case study of a club culture within the Australian football League. Psychol Sport Exerc 2015;21:98–108. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park S, Lavallee D, Tod D. Athletes' career transition out of sport: a systematic review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2013;6:22–53. 10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Pub. Co, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Knights S, Sherry E, Ruddock-Hudson M, et al. The end of a professional sport career: ensuring a positive transition. J Sport Manag 2019;33:518–29. 10.1123/jsm.2019-0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2024-001991supp001.pdf (71KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2024-001991supp002.pdf (79.2KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2024-001991supp003.pdf (64.6KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2024-001991supp004.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.