Obesity has risen to epidemic levels worldwide over the past few decades and has become a huge global health burden owing to its direct contribution to the development of some of the most prevalent chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and other cardiovascular diseases. Obesity is a disease of positive energy balance resulting from complex interactions between abnormal neurohumoral responses and an individual’s socioeconomic, environmental, behavioural, and genetic factors leading to a state of chronic inflammation. Understanding the complex nature of the disease is crucial in determining the best approach to combat its rising numbers. Despite recent advancements in pharmacological therapy for the treatment of obesity, reversing weight gain and maintaining weight loss is challenging due to the relapsing nature of the disease. Prevention, therefore, remains the key which needs to start in utero and continued throughout life. This review summarizes the role obesity plays in the pathophysiology of various cardiovascular diseases both by directly affecting endothelial and myocyte function and indirectly by enhancing major cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia. We highlight the importance of a holistic approach needed to prevent and treat this debilitating disease. Particularly, we analyse the effects of plant-based diet, regular exercise, and non-exercise activity thermogenesis on obesity and overall cardiorespiratory fitness. Moreover, we discuss the significance of individualizing obesity management with a multimodal approach including lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery to tackle this chronic disease.

Keywords: Obesity, Overweight, Cardiovascular disease, Adiposity, Holistic health, Healthy lifestyle, Heart disease risk factors, Cardiopulmonary fitness

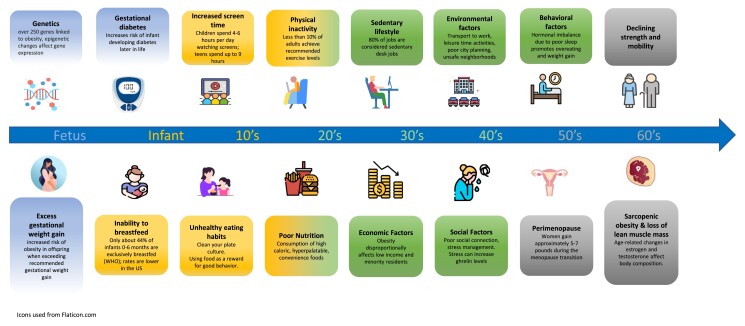

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Obesity is a complex metabolic disease unique to modern humans, defined by chronic positive energy balance leading to excess adiposity, and has become a major global public health problem. Obesity results in a state of chronic inflammation, abnormal hormonal and immune system responses, and ultimately systemic metabolic dysregulation.1 The aetiology of obesity is multifactorial with genetics, environmental factors, socioeconomic status, and behavioural factors all contributing to the development and persistence of obesity. Obesity is a major risk factor for many of the most prevalent global chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), kidney disease, chronic respiratory disease, and multiple types of cancers. It is estimated that obesity is directly responsible for at least 200 000 new cancer cases each year across Europe.2 The direct and indirect costs to society are immense placing significant strain on the health systems and other social resources in many countries.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines overweight individuals as having a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 and obese individuals having a BMI >30 kg/m2.2 Although BMI is not a perfect measure of obesity, it is easy to calculate and in most groups of people correlates well with the percentage of body fat and body fat mass. The prevalence of obesity has risen to epidemic levels in many countries in the past 50 years. As of 2011, nearly 1.5 billion people worldwide were overweight or obese, and it is estimated that almost 60% of adults and nearly one in three children (29% of boys and 27% of girls) in the WHO European Region are overweight or obese.2 In 2018, age-adjusted prevalence of obesity among adults in the USA based upon data collected for National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) was 42.4%.3 Initially a disease of wealthy people in high-income nations, obesity is now a disease of the poor due to global socioeconomic forces including the adoption of global free trade and economic growth and urbanization of low- and middle-income countries.3 In wealthy nations like the USA, overweight and obesity disproportionately affects low-income and minority residents. Non-Hispanic Black women have the highest rates of obesity in the USA—nearly 57%, compared with 44% in Hispanic American women, 40% in non-Hispanic White women, and 17% of non-Hispanic Asian women.3

Physiologically, humans evolved to store calories and conserve energy. This likely conveyed a reproductive and survival advantage, buffering against starvation and avoiding disease-induced anorexia (the thrifty gene hypothesis).4 While storing some amount of fat would have been advantageous, storing large amounts of fat would have increased susceptibility to predation. It is hypothesized that this absence of predation selection in the last 30 000 years allowed for genes that promote energy storage and obesity to persist and drift forward in the genetic journey of human evolution rather than be selected out (the drifty gene hypothesis).4,5 While genetic susceptibility for obesity plays a role in our current obesity epidemic, the evolution of our current obesogenic environment in the last 50 years is the catalyst for the rapid rise in obesity rates in this time frame. The modern Western lifestyle, particularly the overconsumption of hyperpalatable, calorie-dense foods, lack of physical activity (PA), and increased sedentary behaviours facilitated by dramatic shifts in global food production, economic changes in types of employment, transportation, the rise of suburban living, and loss of communal green spaces, contributes to the rising obesity rates.6 As this Western lifestyle has spread globally, we have seen the global rise in obesity in less economically developed nations across various ethnicities and across all age groups.

Once significant weight gain and obesity occurs for the individual, weight loss through healthy lifestyle interventions including severe calorie restricted diets, education about healthy food choices, and increasing PA and scheduled exercise most often fail to achieve and maintain significant weight loss (defined as 5–10% loss of initial body weight). Randomized controlled trials looking at weight loss through lifestyle interventions in obese individuals with and without diabetes, such as the Look AHEAD trial, have demonstrated modest metabolic benefits without a reduction in cardiovascular events or mortality benefit. In addition, lifestyle interventions for the management of obesity involving severe calorie restriction almost always demonstrate rapid weight regain even when weight maintenance therapy is provided.7,8 Undoubtedly, the key to combating the obesity pandemic is preventing people from becoming obese in the first place. This may sound like a modest goal but given the skyrocketing rates of obesity in children of all ages including infants and toddlers, this is no small task. Understanding the genetic predisposition and pathophysiology of obesity will inform the best prevention efforts both at the population health and individual level.

Contribution of obesity to cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors

Obesity directly and indirectly promotes CVD. Excess adiposity induces endothelial dysfunction, small vessel remodelling, and cardiomyocyte toxicity promoting atherosclerotic and vasospastic coronary heart disease, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure.11 Additionally, obesity is a major risk factor for the development of known cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and chronic kidney disease.1

Prolonged excess calorie intake leads to excessive fat storage surpassing the limited storage capacity of adipose tissue for fatty acids. This leads to increased circulating free fatty acids and abnormal storage of fatty acids in organs that play a prominent role in overall metabolic regulation like the liver, pancreas, and skeletal muscle. The lipotoxicity of fatty acids in circulation and stored in organs key for metabolic regulations results in oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation throughout the body.1 Adipose tissue is a complex secretory organ that plays several key roles in metabolism—modulating energy expenditure (EE), appetite, insulin sensitivity, bone metabolism, reproductive and endocrine functions, inflammation, and immunity. Adipocytes synthesize and secrete numerous proteins and hormones called adipokines which play important roles in endocrine regulation, immune function, and inflammation. Obese individuals have dysfunctional adipose tissue that secretes pro-inflammatory proteins like interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-18, while lean individuals’ adipose tissue mostly secretes anti-inflammatory proteins liketransforming growth factor beta, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13.1 The abnormal immune response and pro-inflammatory state induced by obesity promotes insulin resistance, hypertension, renal disease, atherosclerosis other chronic illnesses.1 Additionally, excessive adipose tissue in the epicardium surrounding the heart—frequently seen in overweight and obese individuals—promotes CVD. Epicardial adipose tissue leads to abnormal local adipokine expression, inflammatory cytokine production, and altered gene expression promoting coronary atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure.12

Coronary artery disease

Obesity and obesity-induced cardiovascular risk factors have both been linked to the coronary atherosclerotic burden in autopsy studies of children and young adults.11 In the absence of associated risk factors, obesity is thought to be directly associated with coronary atherosclerotic plaque formation primarily due to obesity-induced inflammation and increased oxidative stress resulting in apo-B lipoprotein oxidation and endothelial dysfunction.11 Several large prospective analyses have indicated that the link between obesity and coronary artery disease is mediated largely by hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, and other comorbidities, whereas other prospective studies suggest a significant residual risk in obese individuals even after accounting for these risk factors.13–15 Most likely both direct vascular dysfunction and injury from excess adiposity and indirect obesity-induced metabolic risk factors significantly contribute to coronary atherosclerosis and ischaemic heart disease.

Heart failure

Data from the ARIC study showed that the risk of developing heart failure related to obesity independent of other metabolic risk factors is higher compared with other forms of CVD with hazard ratios for severe obesity (BMI ≥35 vs. normal weight) of 3.74 [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.24–4.31] for heart failure (HF), 2.00 (95% CI 1.67–2.40) for coronary heart disease (CHD), and 1.75 (95% CI 1.40–2.20) for stroke (P < 0.0001 for comparisons of HF vs. CHD or stroke).13 Obesity is associated with structural and functional changes in the heart that adversely affects haemodynamics and left ventricular (LV) structure and function. Obesity leads to an increase in total blood and stroke volume. In normotensive patients, there is also a decrease in systemic vascular resistance, and the initial net effect is increased cardiac output.16 However over time, the left shift in the Frank–Starling curve due to an increased blood volume and preload results in negative LV remodelling, including LV chamber enlargement and hypertrophy.16 Other adverse responses to obesity include increases in intracardiac filling pressures as well as elevated pulmonary artery pressure. These long-term structural and haemodynamic adaptations predispose obese individuals to both diastolic and systolic heart failure.17 Data from the Framingham Heart Study suggest for every increase in unit of BMI, there is a 5% increased risk of developing heart failure in men and a 7% increased risk in women. The number of years a person is severely obese significantly impacts the prevalence of congestive heart failure, with a prevalence of 70 and 90% after 20 and 30 years, respectively.18 In addition to the direct effects of obesity on cardiac structure and function, the cascade of obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction and disease states are major contributors to obesity-related heart failure.17

Hypertension

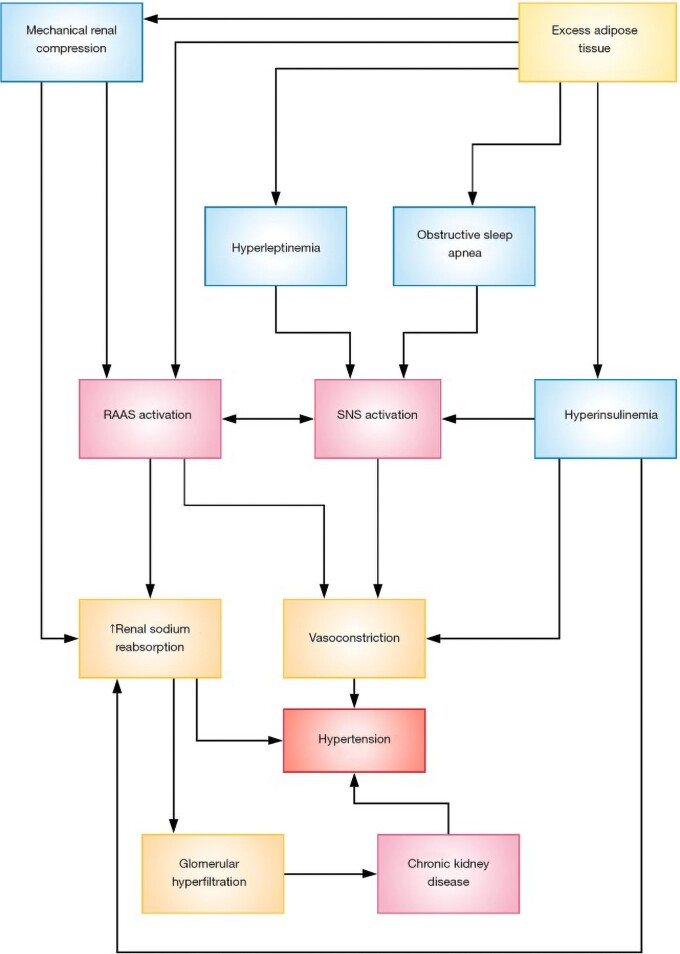

Individuals with hypertension defined as an untreated systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medications, have a two- to three-fold increased risk for all CVD events compared with non-hypertensive individuals. The relative risks of stroke and heart failure with hypertension are greater than for coronary heart disease.19 The relationship between obesity and hypertension is well established with estimates that obesity accounts for 65–78% of cases of essential hypertension9 (Figure 1). Numerous clinical trials and population studies have elucidated the mechanisms of obesity-related hypertension including insulin- and leptin-mediated stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system activating the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) system and renal sodium retention, direct activation of the RAAS system by increased angiotensinogen, angiotensin II, aldosterone, and inflammatory cytokine production in adipose tissue.20 Enhanced renal sodium absorption shifts the pressure natriuresis curve to the right, thereby necessitating higher arterial pressure to excrete the salt intake and maintain sodium balance and volume homeostasis. This mechanism explains the sodium sensitivity of obese patients with hypertension and the need for diuretic therapy in many of these patients.20

Figure 1.

Mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of obesity-related hypertension. RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; SNS, sympathetic nervous system. Reproduced from Shariq and McKenzie.9

Dyslipidaemia

Dyslipidaemia is the largest contributing factor to the development of atherosclerosis and subsequent atherosclerotic CVD in obese individuals.21 Numerous clinical trials including all the statin trials, population studies, and Mendelian randomization studies have clearly demonstrated the causal role of apo-B-containing lipoproteins in the initiation of atherosclerosis. The entrance of apo-B lipoprotein particles within the arterial wall is the fundamental step that initiates and drives the atherosclerotic process from beginning to end.22 Obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases are strongly linked to dyslipidaemia that promotes atherosclerosis. Approximately 60–70% of patients with obesity have abnormal lipids including elevated serum triglycerides, very low density lipoprotein, apolipoprotein B, non-HDL-C levels, and low serum HDL-C. LDL-C levels may or may not be significantly elevated, but there is an increase in small dense LDL particles which are pro-atherogenic because they are more easily oxidized and taken up by macrophages, enter the arterial wall more readily, and have a decreased affinity for the LDL receptor resulting in a prolonged time in the circulation.23 These abnormalities are driven by the combination of the greater delivery of free fatty acids and triglycerides to the liver from excess adipose tissue, insulin resistance, adipocyte dysfunction with reduced adiponectin and increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.24

Role of nutrition in preventing obesity

Controlling energy intake and EE through healthy lifestyle practices will be key to maintaining a healthy weight, optimizing metabolic function, and preventing obesity. Controlling energy intake sounds simple but is quite complex. The central nervous system (CNS) is the primary regulator of food intake with the hypothalamus functioning as the CNS hub for the detection of hunger and organization of eating behaviour based on complex neurohormonal inputs from the rest of the body and the environment.25 Extensive integration between the hypothalamus and other brain centres involved in the processing of external sensory information, cognition, emotional control, and reward-based decision-making takes place throughout the day leading an individual to decide to eat or not to eat. The integration between these vital brain centre differs between lean and obese individuals with direct and powerful implications on metabolic and CVD.25

Beyond its essential role in providing nutrients, food can be a powerful tool in the prevention and treatment of diseases including obesity. The concept that a healthy diet supports good health of the individual is not a novel concept. However, for dietary interventions to have meaningful effects on large populations of people, more efficacy data and scalable implementation strategies are needed. The standard American diet (SAD) is a high sugar, high-saturated fat diet predominantly made up of ultra-processed foods, and large amounts of animal products. This dietary pattern not only promotes weight gain, but also induces gut dysbiosis, metabolic dysregulation, and systemic inflammation. As the US diet has been exported across the globe, it is not surprising that poor diet is the number one risk factor for 11 of the most common chronic diseases that cause premature death and disability worldwide.26 In contrast to the SAD, plant-based dietary patterns high in vegetables, fruits, beans and legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds, and very low in added sugars and oils seem most advantageous for weight loss and healthy weight maintenance.

Findings from large-scale epidemiological studies indicate that whole plant-based diets result in healthy weight maintenance and reduce both the prevalence and incidence of overweight and obesity. This dietary pattern is effective at preventing obesity because it minimizes unhealthy ultra-processed and addictive foods, and because whole plant foods have low calorie density, low saturated fat, no dietary cholesterol, are rich in phytonutrients and antioxidants, and are high in fibre and water. These healthy attributes reduce inflammation and promote a diverse and symbiotic gut microbiome necessary for optimal metabolic and immune function as well as positive appetite regulation.

The Adventist Health Study-1 identified five factors promoting longevity and reducing the risk of cancer and CVD. These five factors included abstaining from tobacco use, having a lower (more normal) BMI, exercising often, following a vegetarian diet, and eating nuts frequently.27 Similarly, findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford) study have shown that vegans gain significantly less weight as they age compared with omnivores.24

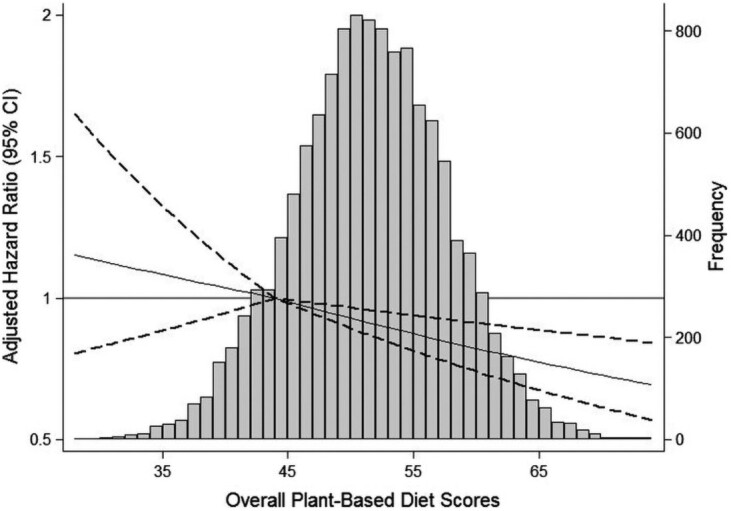

Whole food plant-based dietary patterns have also been shown to reduce CVD and mortality. Kim et al. used data from the ARIC trial to demonstrate that higher adherence to an overall plant-based diet emphasizing whole and minimally processed plant foods and lower amounts of animal foods was associated with a lower risk of incident CVD, CVDmortality, and all-cause mortality. Participants in the highest vs. lowest quintile for adherence to the overall plant-based diet index (PDI) had a 16, 31–32, and 18–25% lower risk of CVD, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality, respectively10 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incident cardiovascular disease, according to the continuous overall plant-based diet index. The histogram shows the distribution of scores for the plant-based diet index in grey. The solid lines represent the adjusted hazard ratios for incident cardiovascular disease, modelled using two linear spline terms with one knot at the 12.5th percentile of plant-based diet index (score, 44), which was used as the reference point. The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. ‘Reproduced from Kim et al.10

Prevention (across the life course)

Primordial prevention, defined as preventing the development of cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, starts in utero. Not only does excessive gestational weight gain increase the mother’s risk for long-term weight retention, but numerous studies demonstrate the influence of maternal pre-pregnancy weight and nutritional status, and gestational weight gain in the development of obesity in offspring.28–30 As a result, the Institute of Medicine Guidelines recommend that pre-pregnancy BMI be used to guide recommendations for gestational weight gain. If weight gain between prenatal visits is excessive [more than 1.5 lb (0.68 kg) per week] after the first trimester, clinicians should be evaluating the individual’s eating habits, as excessive gestational weight gain is primarily related to caloric intake above the metabolic needs of pregnancy. Effective behavioural counselling interventions should be offered.31 Pregnant or postpartum women should do at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic PA per weeks during and after pregnancy. Women who already do vigorous-intensity aerobic PA, such as running, can continue doing so during and after their pregnancy.32

Several studies have indicated a protective effect of breastfeeding on reducing the risk of childhood obesity. A meta-analysis including 26 studies with over 332 297 participants concluded that breastfeeding is inversely associated with a risk of early obesity in children aged 2–6 years. Moreover, there was a dose–response effect between the duration of breastfeeding and reduced risk of early childhood obesity.33 Data from 22 participating countries in the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative confirmed this beneficial effect.34 In separate studies, formula feeding was independently related to higher BMI growth patterns later in childhood,35 and early introduction of solid foods may further increase the risk of high childhood BMI among formula-fed infants compared with exclusively breastfed infants.36

Although the importance of breastfeeding is well recognized for infant and child health, there is growing interest in maternal health benefits and outcomes. Nursing may help mothers lower their risk of heart attack and stroke long after giving birth.37 A large prospective cohort study among nearly 300 000 women in China showed that a history of breastfeeding was associated with a 10% lower risk of CVD later in life. Moreover, each additional 6 months of breastfeeding was associated with a further 3–4% lower CVD risk.38 The mechanisms for these benefits have not been fully elucidated, and the observational nature of this study cannot conclude causation. However, breastfeeding increases metabolic expenditure by an estimated 480 kcal/day and may enable a more rapid reversal of metabolic changes in pregnancy, including improved insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism and greater mobilization of fat stores, to explain these findings at least partly.

Infancy seems to be one of the most important periods influencing health later in life and may thus represent the best time to prevent obesity and its adverse consequences.39 Specifically, the first 1000 days between pregnancy and the child’s second birthday represent a critical period affecting health and development and can set the stage for later obesity, diabetes, and chronic diseases. Concerted efforts by both parents to practice healthy eating themselves and serve as role models for their children are important. Monitoring the baby’s growth during early life with healthcare providers is crucial to direct change. Additional good practices include exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age, waiting until 4–6 months to introduce complementary feeding with early introduction of fruits and vegetables, repeating exposures to new foods if not accepted at first, and avoidance of ‘clean your plate’ feeding practices, and not using food as reward for good behaviour. Television and other screens should be turned off during meals.39

Childhood obesity begets adult obesity. Obese children have five times higher risk of adult obesity than normal-weight children.40 Further, childhood and adolescent obesity increases the incidence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in adulthood. Although an imbalance between caloric intake and PA is a principal cause of childhood and adolescent obesity, environmental factors are almost exclusively important for the development of obesity among children and adolescents.41 Treatment of obesity in this population is challenging and complex. Therefore, early identification and prevention is vital. Promoting PA is essential. Preschool-aged children (ages 3–5) should be physically active throughout the day with a reasonable target of 3 h/day of PA. Children and adolescents aged 6–17 should do 60 min or more of moderate-to-vigorous activity daily.32 One of the best predictors of regular PA in adulthood is participation in organized sports at a young age. Data from the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study concluded that a high level of PA at ages 9–18, especially when continuous, significantly predicted a high level of adult PA.42 In addition, increasing PA during the school day is a critical strategy for addressing childhood obesity and improving overall health to improve total daily PA levels of youth.43 Widespread use of smartphones and tablets may erode PA time by increasing sedentary time. Parents, guardians, and teachers can help maintain a healthy weight by helping kids develop healthy eating habits early on. Reduced consumption of unhealthy, calorie-dense, and ultra-processed foods is also necessary and discussed separately (see the Role of nutrition in preventing obesity section).

Over two-thirds of adults in the USA are overweight or obese. One’s ability to choose healthy lifestyle across the life course is strongly influenced by psychological health factors and social and structural determinants of health. Factors such as structural racism, discrimination, poverty, food insecurity, housing instability, neighbourhood safety, and lack of access to quality healthcare are key drives of differences in obesity rates across racial and ethnic groups. For example, food insecurity often means families must eat food that costs less but is also high in calories and low in nutritional value. Policies, such as healthy school meals for all students, improved nutritional quality of available foods, including nutrition assistance programmes, and expanded support for maternal and childhood health, are needed.44 Increasing awareness and resources for eating healthy on a budget, including tips and recipes, such as those offered on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, should be integrated into healthcare and community settings. MyPlate.gov, based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, can help with targeting daily food group targets and their portion sizes and planning future meals. In addition to a healthy eating plan, an active lifestyle will help maintain weight. Adults should aim for a minimum of 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous activity each week. Additional details are discussed in the Role of movement section.

Role of ageing

Ageing is associated with weight gain in both sexes, typically related to reductions in resting metabolic rate and often EE as well. On average, muscle mass declines with age, and even in older persons with stable weight, muscle is replaced by fat over time and preferentially accumulates both viscerally and ectopically rather than as subcutaneous fat. Sarcopenia, which is the loss of muscle mass and strength or physical function, naturally occurs with ageing. Sarcopenia synergistically worsens the adverse effects of obesity in older adults, resulting in sarcopenic obesity.45 Sarcopenic obesity leads to increased risk of frailty and activity of daily living disability in addition to metabolic impairments such as dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance. Sex-specific changes in muscle and fat composition are partly due to age-related changes in oestrogen and testosterone. Testosterone levels decline by ∼1% per year, which can negatively affect muscle mass and fat distribution in ageing. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 790 older men (65 years or older), raising testosterone concentrations for 1 year did not improve vitality or walking distance.46 Low testosterone levels as a consequence of obesity in men are reversible with lifestyle modification. The natural rise in serum testosterone in obese men is proportional to the amount of weight lost.47 Few clinical trials specifically focus on sarcopenic obesity; however, intentional weight loss in older adults improves morbidity and physical function.48 Weight loss plus combined aerobic and resistance exercise appears to be the most effective method for improving functional status of adults aged 65 years and older with obesity.49 From a nutritional perspective, distributing protein intake throughout the day may be beneficial in patients with sarcopenic obesity.50 Generally, 25–30 g of protein containing 2.5–2.8 g of leucine can slow frailty.45 However, further evidence is needed to support the effect of supplemental protein on functional outcomes in patients with sarcopenic obesity.

Weight gain with an increased tendency for central fat distribution is common among women in midlife, often a result of ageing and hormonal changes (and related symptoms) during the menopause transition is associated with several adverse metabolic consequences (insulin resistance, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension). On average, women gain ∼5–7 pounds (or 2–3 kg) over the course of the menopause transition, yet there is substantial interindividual variability.51 Therefore, the importance of weight management in midlife is critical to preventing cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in postmenopausal women.52 A systematic review compared weight loss success across different lifestyle interventions and reported that postmenopausal women with obesity who were randomized to either diet or exercise modification alone had greater weight and fat mass loss compared with controls, whereas combining both diet and exercise resulted in the greatest weight and fat mass loss.51 Unless a post-menopausal woman adjusts her caloric intake and/or consciously increases her PA level, a state of positive energy balance results, with associated weight gain. Initiating lifestyle modification programmes that incorporate diet and exercise (aerobic and resistance training) for women during perimenopause may be timelier and have a higher yield in terms of reducing future risk of cardiometabolic than waiting until the postmenopausal years, after substantial weight gain and fat mass accrual have already occurred. While prevention is ideal, weight management counselling to all women with an increased BMI, even when not specifically sought by the patient, should be instituted. Although intense interventions addressing diet and nutrition achieve more success in helping patients lose weight, physicians often do not have time to provide such counselling. Access to dieticians or formal weight loss programmes may also be limited depending on the healthcare system and socioeconomic factors. However, simple interventions, such as physician acknowledgement of patients’ weight, have been shown to increase the accuracy of patients’ perceptions of their weight, in addition to increasing their desire, attempts, and success to lose weight.53 This presents a useful first step for weight control.

Disruptions in sleep (shortened or interrupted sleep) become more prevalent in women as they age and particularly around menopause transition with a prevalence of 39–47 and 35–60% in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, respectively. Sleep disruption promotes increased energy intake due to a combination of altered appetite hormones and altered sensitivity to food reward and disinhibited eating. It is likely that women who experience sleep disruption during menopause may experience greater weight gain and abdominal fat gain compared with women who do not.51 Given sleep disruption is one of the main reasons why women seek medical care during menopause, future studies need to disentangle the degree to which sleep disruption alters individual behaviour (i.e. energy intake and PA) and metabolism across menopause and possibly exacerbates metabolic dysfunction and weight gain. Though hormone replacement therapy can help with vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbances related to menopause, oestrogen therapy does not prevent weight gain in postmenopausal females.54 Of note, a meta-analysis of 28 trials in 28 559 women found no evidence of an effect of hormone replacement therapy (unopposed oestrogen or combined oestrogen–progestin) on body weight or BMI,55 and current clinical guidelines do not recommend the use of menopausal hormone therapy for preventive indications.

Role of movement

Adults should aim for a minimum of 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous activity and 2 days of muscle strengthening activity each week.32 Physical activity is one of the best things people can do to improve their health. It is vital to healthy ageing and reduces the burden of chronic diseases. PA is associated with improvements in overall cardiovascular health and longevity and much of these benefits result from improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), which is a much stronger predictor of prognosis than exercise and PA alone.56 In this context, there has been debate about the relative effects of fitness vs. fatness on morbidity and mortality. Results from a meta-analysis of eight studies showed that fitness, perhaps the single most important predictor of overall health, did not completely abolish the adverse effects of BMI on mortality risk. However, the risk was still less than that in unfit individuals across all levels of BMI.57 In other words, low CRF is a stronger predictor of CVD mortality risk (more than double) than is elevated BMI.

The vast majority of studies investigating the effects of aerobic exercise training on weight loss suggest that achievement of the minimum levels of PA (∼150 min of moderate-intensity per week) without dietary restriction are generally unlikely to result in clinically significant weight loss (at least 5%).58 Therefore, the American College of Sports Medicine currently recommends 225–420 min/week of exercise for individuals attempting to lose weight.59 Caloric restriction in combination with exercise adherence (‘eat less and move more’) is recommended for the treatment of overweight and obese adults. For those who are unable to lose weight, but can maintain regular exercise habits, it remains important for clinicians to emphasize that improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors occur independent of weight loss. These include improvements in adiposity, insulin sensitivity, arterial compliance, endothelial function, lipid profiles, and CRF.58

Resistance training alone is unlikely to produce sufficient negative energy balance to result in clinically significant weight loss compared with aerobic training for at least a couple of reasons. First, aerobic training entails a higher total EE than resistance training. Second, potential gains in lean mass from resistance training can attenuate weight loss. The increase in lean body mass often translates into a higher resting metabolic rate and is perhaps more helpful with weight maintenance. Clinically, tracking body weight alone with resistance training may obscure potential improvements in overall body composition.59

Regular exercise activity can prevent weight regain. A staggering statistic is that 80% of individuals who achieve significant weight loss are not able to maintain the weight loss.60 This is likely multifactorial, including neurohormonal response to weight loss such as increases in appetite hormones (e.g. ghrelin) and reductions in anorexigenic hormones [leptin, glucagon-like peptie-1 (GLP-1)] in addition to reductions in compliance with self-monitoring/weighing habits, and reductions in resting metabolic rate with weight loss.61 There is strong evidence to demonstrate a relationship between greater amounts of PA and attenuated weight gain in adults. Moderate-intensity PA between 150 and 250 min/week appears to be effective to prevent weight gain.59 According to the American College of Sports Medicine, a realistic weight loss goal includes (i) burning 300–400 calories per workout session, (ii) preferably daily exercise, (iii) a daily calorie deficit of ∼500–1000 calories through regular PA and calorie monitoring, and (iv) no more than 2 pounds of weight loss per week.59

In addition to regular PA, adults should aim to sit less throughout the day. Sitting is now ubiquitous in modern society. In fact, up to 80% of jobs are now considered ‘sedentary’ desk jobs. An elegant study of US trends between 1960 and 2010 concluded that a decrease in occupation-related EE—about a difference of 120–140 calories burned per day—accounts for a significant portion of the increase in mean US body weight during these five decades.62 Not all movement is exercise, and ‘too little exercise’ is not equivalent to ‘too much sitting’. Non-exercise activity refers to light-intensity activities of 1.6–2.9 metabolic equivalents with examples including slow walking, standing, shopping, and occupation and self-care-related activities. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) is defined as the energy expended in spontaneous, non-exercise activities and is the most variable component of total EE, ranging from 300 to 2000 calories/day depending on an individual’s activities. For example, the EE of seated workers is around 700 calories/day compared with those with manual labour jobs (active construction work) up to 2300 calories/day.63 Targeting NEAT could be an essential tool for body weight control, particularly when decades of promoting exercise activity for public health benefits has had dismal results. From nationwide self-reported PA, the age-adjusted proportion who reported meeting the 2018 aerobic PA guidelines for Americans was 54.2% (only 24% if including the 2 days of muscle-strengthening activities).64 This is likely an over-estimated based on subjective questionnaire measurements. Data from the NHANES using accelerometry measures have estimated that only 9.6% of adults achieve recommended levels.58

What are the appropriate activities for increasing NEAT and what are realistic goals for daily amounts of NEAT? Increases in NEAT are categorized into individual-level approaches (occupation, transportation to work, leisure-time activities) vs. environmental re-engineering approaches (city planning, bike-accessible environments, walkways, safe neighbourhoods). It can be relatively easy to increase NEAT. Standing instead of sitting burns three times more calories per hour, and stair climbing more than 40 times resting levels.65 If the amount of PA necessary for weight loss approximates 2000–2500 calories per week—this would amount to ∼2.5 h of additional daily ambulation/standing (non-exercise activity) time integrated into one’s routine. Because occupation is the principal determinant of NEAT in adulthood, how NEAT can be primarily integrated at the site of occupation deserves attention. A small study of 15 sedentary office workers replaced sitting with standing an average of 90 min/day when given an adjustable sit–stand desk at work. While there was no change in body weight, significant improvements in fasting triglycerides, insulin resistance, and endothelial function of the superficial femoral artery occurred within 12 weeks and was sustained over 24 weeks.66 In a separate study, 25 sedentary adults working at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System used a walking treadmill workstation (slow pace, maximum 2 miles/h) for 2.5 h/day 5 days a week. After just 2 weeks, treadmill use at work led to a leaner phenotype (lean mass gain and fat mass loss measured by air displacement plethysmography).67 While both individual- and environmental-level approaches should be considered to increase NEAT, there is currently a lack of evidence as to whether one approach is more effective in terms of increasing PA levels and/or affecting body mass.68

Role of pharmacotherapy, weight loss surgery, and commercial weight loss programmes

Weight loss medications, weight loss surgery, and commercial weight loss programmes may also be considered for management of obesity. Pharmacotherapy is indicated for patients with BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater and obesity-related comorbidity or BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater. In a review of drug treatment for obesity, weight loss with orlistat was 2.94 kg (95% CI 1.27–5.82 kg); for naltrexone/bupropion, it was 6.15 kg (95% CI 3.25–9.78 kg); for phentermine/topiramate, it was 7.45 kg (3.88–9.76 kg); and for liraglutide, it was 5.50 kg (95% CI 2.97–10.62 kg).69 Although none of these four drugs produce a placebo-subtracted weight loss that exceed 10% on average, novel pharmacological agents targeting gastrointestinal peptides, including the GLP-1 agonists, targeting the complex neurohormonal mechanisms involved in weight control, seem to provide a more effective pharmacologic treatment strategy for management of obesity. Initially developed as treatment for Type 2 diabetes mellitus, these GLP-1 agonists improve glycaemic control by enhancing insulin secretion and inhibiting glucagon release from the pancreas as well as reducing appetite and food cravings through their neurohormonal actions in the brain.

Liraglutide and semaglutide are modified, long-acting analogues of native GLP-1. Liraglutide’s half-life is 13–15 h compared with semaglutide’s half-life of 165 h. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 338 participants, comparing liraglutide (3.0 mg subcutaneous daily) with semaglutide (2.4 mg subcutaneous once-weekly) in adults without diabetes and with a BMI ≥ 30 (mean BMI 37.5) demonstrated a mean weight loss of 6.4% for liraglutide and 15.8% for semaglutide at 68 weeks.70 Participants had significantly greater odds of achieving 20% or more weight loss with semaglutide vs. liraglutide [odds ratio 8.2 (95% CI 3.5–19.1)].70 The weight loss was accompanied by significantly greater improvements in several cardiometabolic risk factors, including waist circumference, total cholesterol level, very LDL cholesterol level, triglyceride level, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c, fasting plasma glucose, CRP, and diastolic blood pressure. The SELECT trial reveals that the benefits of semaglutide extend beyond biomarkers and weight loss. This randomized, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated reduction in composite of death from cardiovascular causes, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke by 20% in the semaglutide group compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.8; 95% CI 0.72–0.90; P < 0.001).71 Likewise, in patients with obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg subcutaneous weekly led to a larger reduction in heart failure-related symptoms and physical limitations, greater improvement in exercise function and more weight loss compared with placebo in the STEP-HFpEF trial.72

A newer drug, tirzepatide, a single molecule with a dual action given as a once-weekly injection that targets both the GLP-1 receptor and the glucose-insulin peptide receptor, appears to further potentiate weight reduction compared with GLP-1 agonists alone. Although tirzepatide demonstrated superiority in reducing weight loss at doses of 5, 10, and 15 mg compared with semaglutide 1 mg in the SURPASS-2 trial,73 a comparison of tirzepatide with semaglutide 2.4 mg has yet to be performed. While these medications are rapidly gaining popularity, long-term pharmacotherapy appears necessary for weight maintenance, as cessation of pharmacological treatment is frequently followed by weight regain, even with continued lifestyle intervention.74 Overall, pharmacologic treatment for obesity is not as effective as bariatric surgery for weight loss and weight maintenance.

Bariatric surgery is one of the fastest-growing operative procedures performed worldwide. In the USA, close to 2 million patients underwent bariatric surgery between 1993 and 2016, during which time the field has evolved from exclusively open surgery to 98% laparoscopic surgery.75 There are three major surgical procedures in wide use, with sleeve gastrectomy (SG) being most common, followed by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB). In the multicentre, NIH-funded longitudinal study of bariatric surgery, the median weight loss after 3 years for the 1513 patients undergoing RYGB was 31.5% [interquartile range (IQR): 24.6–38.4%]. For the 509 patients undergoing LAGB, the weight loss was about half as much at 16.0% (IQR: 8.1–23.1%).76 Furthermore, weight loss was sustained or even increased after 7 years for the RYGB and LAGB surgeries.77 Regardless of the procedure, most patients will regain some weight over time, typically around 5–10% in the first decade after surgery, and typically higher in the less invasive surgeries (LAGB) compared with the RYGB.78 In addition to significant weight loss, bariatric operations also improve many obesity-related health problems, such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia.79 Consequently, the risk of cardiovascular disease is lowered after bariatric surgery. A 2009 meta-analysis of 19 mostly observational studies with 1–3 years of follow-up reported a Type 2 diabetes remission rate of 78% and an improvement rate of 87%.80 Remission rates are higher in procedures with a greater percentage of excess body weight loss (more with RYGB than SG).

Commercial and proprietary weight loss programmes are popular obesity treatment options. A systematic review including 45 studies, 39 of which were randomized clinical trials, showed that Weight Watchers participants achieved 2.6% greater weight loss and Jenny Craig participants achieved 4.9% greater weight loss than control/education subjects at 12 months. Many of the other trials were shorter in duration (<12 months), had high attrition rates, and lacked blinding.81 Nonetheless, clinicians could consider referring overweight or obese patients to one of these commercial programmes though additional studies evaluating long-term outcomes are needed.

Holistic approach to weight management

Obesity is a chronic disease that is difficult to manage without holistic therapy. A systematic review on the outcomes of weight loss lifestyle modification programmes found that at 1 year, 30% of participants had a weight loss of at least 10% with another 25% of participants between 5 and 9.9% weight loss. About 50% of patients return to their original weight after ∼5 years.82 The 10-year follow-up data of the randomized clinical trial Diabetes Prevention Program showed that cumulative incidence of diabetes remained lower in the lifestyle group even in the setting of partial weight regain.83 Therefore, weight regain may not fully diminish benefits of weight loss on cardiometabolic health, and traditional lifestyle modifications programme likely require a greater focus on long-term weight management.

At our centre, we take a holistic approach to weight management. The Weight Management Clinics (part of the Medical Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery Program) are an appropriate option for anyone who is significantly overweight, especially individuals who are obese and struggle with related health issues, such as high blood pressure or cholesterol, heart disease, or diabetes. The focus is on individualized weight management strategies, management of other health conditions, and a comprehensive approach involving education, tools, and guidance.

Our multi-disciplinary team of specialists conducts a complete medical, dietary, and activity history to uncover factors that may have contributed to weight gain. To support individual weight loss goals, each patient receives a personalized treatment plan that may include nutritional recommendations, education, eating strategies, activity adjustments, lifestyle modification, psychotherapy or behavioural therapy, and management of medications. The treatment period depends on each patients’ degree of motivation and concurrent health conditions. For some patients, the evaluation determines that bariatric surgery will be the most effective means of achieving weight loss goals, at which time a referral to our Bariatric Surgery Program is made.

For patients concerned with cardiovascular risk related to overweight and obesity, our Preventive Cardiology Program provides individualized cardiovascular risk assessment, promotion of plant-based dietary recommendations, complex lipid disorders management (where diet composition and weight management are key), and healthy lifestyle recommendations designed to achieve Life’s Essential 8 (American Heart Association). Diets void of animal protein and rich in plants typically lead to weight loss without changes in PA amounts or levels. Therefore, self-motivated patients can achieve weight loss and improvement in cardiovascular risk factors with lifestyle coaching through the Preventive Cardiology Program.

Conclusions

According to the WHO, there are ∼2 billion adults who are overweight including 650 million people who meet criteria for being obese. If these rates do not slow down, it is expected that 2.7 billion adults will be overweight and over 1 billion will be obese by 2025. Obesity is a complex disease that results from interactions between the environment, and an individual’s lifestyle, behaviours, and genetic susceptibility. Poor nutrition due to alterations in the global food system in combination with the adoption of a sedentary lifestyle represents the main drivers of the obesity epidemic.

The excess adiposity that defines obesity and the neurohormonal dysregulation that it causes increase the risk of all forms of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors. Once an individual becomes significantly overweight and obese, reversing weight gain and restoring a healthy body weight and more importantly restoring metabolic health becomes extremely difficult. Therefore, preventing people from becoming overweight and/or obese needs to be the focus of global efforts at combating obesity, and needs to start in utero with providing pregnant woman with resources to maintain healthy nutrition, curb excess weight gain, encourage breastfeeding, and remain physically active throughout pregnancy and after delivery. Nutrition studies of all types conducted in the last 50–60 years have demonstrated that a whole food plant-based dietary pattern emphasizing the consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, beans and legumes, nuts, seeds, while minimizing ultra-processed foods and animal foods high in saturated fat and dietary cholesterol not only prevent overweight and obesity, but prevent lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors like high blood pressure and diabetes and well as all forms of cardiovascular disease. Although moderate amounts of physical exercise do not result in substantial weight loss, the overall health benefits of regular exercise and strong evidence to demonstrate a relationship between greater amounts of PA and attenuated weight gain in adults underscore the importance of routine exercise and PA. In a holistic approach, understanding the complex interplay between consumption of specific foods, health, PA levels, and disease outcomes has enormous potential to inform interventions for prevention and treatment of obesity and obesity-related diseases.

Contributor Information

Aimee Welsh, Division of Cardiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 W. Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA.

Muhammad Hammad, Division of Cardiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 W. Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA.

Ileana L Piña, Division of Cardiology, Thomas Jefferson University, 925 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Jacquelyn Kulinski, Division of Cardiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 W. Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA.

Author contribution

A.W. and J.K. designed and drafted the manuscript. A.W. drafted the central figure. I.L.P. contributed to the conception of the work and critically revised the manuscript. M.H. and J.K. finalized the Graphical Abstract. M.H. critically revised the manuscript. All gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Funding

This publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL162888. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Khanna D, Welch BS, Rehman A. Pathophysiology of obesity. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572076/ (20 October 2022). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/353747 World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022.

- 3. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. p 1–8. [PubMed]

- 4. Sellayah D, Cagampang FR, Cox RD. On the evolutionary origins of obesity: a new hypothesis. Endocrinology 2014;155:1573–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Speakman JR, Elmquist JK. Obesity: an evolutionary context. Life Metab 2022;1:10–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaczynski AT, Eberth JM, Stowe EW, Wende ME, Liese AD, McLain AC, et al. Development of a national childhood obesogenic environment index in the United States: differences by region and rurality. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020;17:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, Jakicic J, Rejeski J, Williamson D, et al. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity 2006;14:737–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. One-year behavioral treatment of obesity: comparison of moderate and severe caloric restriction and the effects of weight maintenance therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shariq OA, McKenzie TJ. Obesity-related hypertension: a review of pathophysiology, management, and the role of metabolic surgery. Gland Surg 2020;9:80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim H, Caulfield LE, Garcia-Larsen V, Steffen LM, Coresh J, Rebholz CM. Plant-based diets are associated with a lower risk of incident cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality in a general population of middle-aged adults. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després J-P, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;143:e984–e1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Konwerski M, Gąsecka A, Opolski G, Grabowski M, Mazurek T. Role of epicardial adipose tissue in cardiovascular diseases: a review. Biology 2022;11:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ndumele CE, Matsushita K, Lazo M, Bello N, Blumenthal RS, Gerstenblith G, et al. Obesity and subtypes of incident cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Boshuizen HC, Woodward M, Knekt P, et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1720–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1983;67:968–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alpert MA, Lavie CJ, Agrawal H, Kumar A, Kumar SA. Cardiac effects of obesity: pathophysiologic, clinical, and prognostic consequences-a review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2016;36:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gadde KM, Martin CK, Berthoud HR, Heymsfield SB. Obesity: pathophysiology and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alpert MA, Terry BE, Mulekar M, Cohen MV, Massey CV, Fan TM, et al. Cardiac morphology and left ventricular function in normotensive morbidly obese patients with and without congestive heart failure, and effect of weight loss. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD. Blood pressure, systolic and diastolic, and cardiovascular risks. US population data. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:598–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity-induced hypertension—interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res 2015;116:991–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wickramasinghe M, Weaver JU. Practical Guide to Obesity. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2018. p99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sniderman AD, Thanassoulis G, Glavinovic T, Navar AM, Pencina M, Catapano A, et al. Apolipoprotein B particles and cardiovascular disease: a narrative review. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:1287–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klop B, Elte JW, Cabezas MC. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients 2013;5:1218–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosell M, Appleby P, Spencer E, Key T. Weight gain over 5 years in 21,966 meat-eating, fish-eating, vegetarian, and vegan men and women in EPIC-Oxford. Int J Obes 2006;30:1389–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Peters JC. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation 2012;126:126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators . Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1859–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wynder EL, Lemon FR. Cancer, coronary artery disease and smoking: a preliminary report on differences in incidence between Seventh-day Adventists and others. Calif Med 1958;89:267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diesel JC, Eckhardt CL, Day NL, Brooks MM, Arslanian SA, Bodnar LM. Gestational weight gain and offspring longitudinal growth in early life. Ann Nutr Metab 2015;67:49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Diesel JC, Eckhardt CL, Day NL, Brooks MM, Arslanian SA, Bodnar LM. Is gestational weight gain associated with offspring obesity at 36 months? Pediatr Obes 2015;10:305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sridhar SB, Darbinian J, Ehrlich SF, Markman MA, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A, et al. Maternal gestational weight gain and offspring risk for childhood overweight or obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:259.e1–259.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Poston LP. Gestational weight gain. In Uptodate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc.http://www.uptodate.com (10 January 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018;320:2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma J, Qiao Y, Zhao P, Li W, Katzmarzyk PT, Chaput J-P, et al. Breastfeeding and childhood obesity: a 12-country study. Matern Child Nutr 2020;16:e12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rito AI, Buoncristiano M, Spinelli A, Salanave B, Kunešová M, Hejgaard T, et al. Association between characteristics at birth, breastfeeding and obesity in 22 countries: the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative—COSI 2015/2017. Obes Facts 2019;12:226–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Flores-Barrantes P, Iguacel I, Iglesia-Altaba I, Moreno LA, Rodriguez G. Rapid weight gain, infant feeding practices, and subsequent body mass index trajectories: the CALINA study. Nutrients 2020;12:3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Imai CM, Gunnarsdottir I, Thorisdottir B, Halldorsson TI, Thorsdottir I. Associations between infant feeding practice prior to six months and body mass index at six years of age. Nutrients 2014;6:1608–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kulinski JP. Life’s simple 7 1/2 for women. Circulation 2020;141:501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peters SAE, Yang L, Guo Y, Chen Y, Bian Z, Du J, et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of maternal cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of 300 000 Chinese women. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e006081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pietrobelli A, Agosti M, MeNu G. Nutrition in the first 1000 days: ten practices to minimize obesity emerging from published science. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee EY, Yoon KH. Epidemic obesity in children and adolescents: risk factors and prevention. Front Med 2018;12:658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Valimaki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Long MW, Sobol AM, Cradock AL, Subramanian SV, Blendon RJ, Gortmaker SL. School-day and overall physical activity among youth. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. State of Obesity 2022: Better Policies for a Healthier America. Trust for America's Health; 2022.

- 45. Batsis JA, Villareal DT. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:513–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Snyder PJ, Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Stephens-Shields AJ, Cauley JA, Gill TM, et al. Effects of testosterone treatment in older men. N Engl J Med 2016;374:611–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kelly DM, Jones TH. Testosterone and obesity. Obes Rev 2015;16:581–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S; American Society for Nutrition; NAASO The Obesity Society . Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obes Res 2005;13:1849–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Villareal DT, Aguirre L, Gurney AB, Waters DL.Sinacore DR, Colombo E, et al. Aerobic or resistance exercise, or both, in dieting obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1943–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deutz NE, Bauer JM, Barazzoni R, Biolo G, Boirie Y, Bosy-Westphal A, et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin Nutr 2014;33:929–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marlatt KL, Pitynski-Miller DR, Gavin KM, Moreau KL, Melanson EL, Santoro N, et al. Body composition and cardiometabolic health across the menopause transition. Obesity 2022;30:14–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kapoor E, Collazo-Clavell ML, Faubion SS. Weight gain in women at midlife: a concise review of the pathophysiology and strategies for management. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:1552–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pool AC, Kraschnewski JL, Cover LA, Lehman EB, Stuckey HL, Hwang KO, et al. The impact of physician weight discussion on weight loss in US adults. Obes Res Clin Pract 2014;8:e131–e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen Z, Bassford T, Green SB, Cauley JA, Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and body composition—a substudy of the estrogen plus progestin trial of the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Norman RJ, Flight IH, Rees MC. Oestrogen and progestogen hormone replacement therapy for peri-menopausal and post-menopausal women: weight and body fat distribution. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;2:CD001018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ozemek C, Laddu DR, Lavie CJ, Claeys H, Kaminsky LA, Ross R, et al. An update on the role of cardiorespiratory fitness, structured exercise and lifestyle physical activity in preventing cardiovascular disease and health risk. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2018;61:484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Barry VW, Caputo JL, Kang M. The joint association of fitness and fatness on cardiovascular disease mortality: a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2018;61:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Swift DL, McGee JE, Earnest CP, Carlisle E, Nygard M, Johannsen NM. The effects of exercise and physical activity on weight loss and maintenance. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2018;61:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:222S–225S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Soleymani T, Daniel S, Garvey WT. Weight maintenance: challenges, tools and strategies for primary care physicians. Obes Rev 2016;17:81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, Katzmarzyk PT, Earnest CP, Rodarte RQ, et al. Trends over 5 decades in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS One 2011;6:e19657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 2007;56:2655–2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;145:e153–e639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Levine JA. Nonexercise activity thermogenesis—liberating the life-force. J Intern Med 2007;262:273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bodker A, Visotcky A, Gutterman D, Widlansky ME, Kulinski J. The impact of standing desks on cardiometabolic and vascular health. Vasc Med 2021;26:374–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Malaeb S, Perez-Leighton CE, Noble EE, Billington C. A “NEAT” approach to obesity prevention in the modern work environment. Workplace Health Saf 2019;67:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. von Loeffelholz C, Birkenfeld AL. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis in human energy homeostasis. In Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dong Z, Xu L, Liu H, Lv Y, Zheng Q, Li L. Comparative efficacy of five long-term weight loss drugs: quantitative information for medication guidelines. Obes Rev 2017;18:1377–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, O’Neil PM, Rosenstock J, Sørrig R, et al. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022;327:138–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Esbjerg S, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med 2023;389:2221–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kosiborod MN, Abildstrøm SZ, Borlaug BA, Butler J, Rasmussen S, Davies M, et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1069–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Frias JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, Pérez Manghi FC, Fernández Landó L, Bergman BK, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021;385:503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Kandler K, Konakli K, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: the STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab 2022;24:1553–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Campos GM, Khoraki J, Browning MG, Pessoa BM, Mazzini GS, Wolfe L. Changes in utilization of bariatric surgery in the United States from 1993 to 2016. Ann Surg 2020;271:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA 2013;310:2416–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, Berk P, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) study. JAMA Surg 2018;153:427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, Smith VA, Yancy WS, Weidenbacher HJ, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg 2016;151:1046–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vest AR, Heneghan HM, Agarwal S, Schauer PR, Young JB. Bariatric surgery and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. Heart 2012;98:1763–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009;122:248–256.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gudzune KA, Doshi RS, Mehta AK, Chaudhry ZW, Jacobs DK, Vakil RM, et al. Efficacy of commercial weight-loss programs: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:501–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Montesi L, El Ghoch M, Brodosi L, Calugi S, Marchesini G, Dalle Grave R. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: a multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2016;9:37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009;374:1677–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]