Abstract

Viruses resembling human TT virus (TTV) were searched for in sera from nonhuman primates by PCR with primers deduced from well-conserved areas in the untranslated region. TTV DNA was detected in 102 (98%) of 104 chimpanzees, 9 (90%) of 10 Japanese macaques, 4 (100%) of 4 red-bellied tamarins, 5 (83%) of 6 cotton-top tamarins, and 5 (100%) of 5 douroucoulis tested. Analysis of the amplification products of 90 to 106 nucleotides revealed TTV DNA sequences specific for each species, with a decreasing similarity to human TTV in the order of chimpanzee, Japanese macaque, and tamarin/douroucouli TTVs. Full-length viral sequences were amplified by PCR with inverted nested primers deduced from the untranslated region of TTV DNA from each species. All animal TTVs were found to be circular with a genomic length at 3.5 to 3.8 kb, which was comparable to or slightly shorter than human TTV. Sequences closely similar to human TTV were determined by PCR with primers deduced from a coding region (N22 region) and were detected in 49 (47%) of the 104 chimpanzees; they were not found in any animals of the other species. Sequence analysis of the N22 region (222 to 225 nucleotides) of chimpanzee TTV DNAs disclosed four genetic groups that differed by 36.1 to 50.2% from one another; they were 35.0 to 52.8% divergent from any of the 16 genotypes of human TTV. Of the 104 chimpanzees, only 1 was viremic with human TTV of genotype 1a. It was among the 53 chimpanzees which had been used in transmission experiments with human hepatitis viruses. Antibody to TTV of genotype 1a was detected significantly more frequently in the chimpanzees that had been used in transmission experiments than in those that had not (8 of 28 [29%] and 3 of 35 [9%], respectively; P = 0.038). These results indicate that species-specific TTVs are prevalent in nonhuman primates and that human TTV can cross-infect chimpanzees.

A novel DNA virus has been recovered from patients with posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology and named TT virus (TTV) after the initials of the index patient (19, 22). TTV is an unenveloped, single-stranded, circular DNA virus with a genomic length of 3,808 to 3,853 nucleotides (nt) (2, 5, 13, 14, 23). Due to a circular genomic structure, TTV has been placed tentatively into the Circoviridae family (10). TTV DNA is detected in liver tissues at titers from 10 to 100 times higher than those in the corresponding sera (22). TTV is transmitted not only parenterally (19, 22) but also nonparenterally by a fecal-oral route, because it is excreted into the bile and then the feces of infected individuals (21, 35). The presumed dual mode of transmission may enhance the deep and broad penetration of TTV infection in the community in every country examined (1, 6, 18, 24, 26, 40; L. E. Prescott, P. Simmonds, and International Collaborators, Letter, N. Engl. J. Med. 339:776–777, 1998).

For a DNA virus, TTV has a markedly wide range of sequence divergence, in which it is classified into at least 16 genotypes separated by a difference of >30% within a partial sequence in the coding region (N22 region) spanning 222 to 231 nt (15, 21–24, 26, 29–32). Since sequence divergence is more marked in coding than noncoding regions, primers deduced from various genomic regions crucially influence the detection of TTV DNA by PCR (24, 28). PCR with primers deduced from noncoding regions can detect TTV DNA, irrespective of various genotypes, while PCR with primers from coding regions may be used to detect TTV DNA of particular genotypes (24).

Viruses resembling human hepatitis viruses have been identified in various animal species. They include counterparts of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in woodchucks (3), ground squirrels (25), ducks (11), herons (27), gibbons (20), and orangutans (39), as well as that of hepatitis E virus in pigs (12). Furthermore, HBV of a particular genotype has been found in chimpanzees and is presumed to infect them naturally (36).

Chimpanzees are susceptible to infection with TTV (14). Recently, TTV DNA sequences have been found in nonhuman primates and farm animals (9, 37). It remains to be seen, however, whether a single species of TTV infects humans and animals, as proposed (9), or they are infected with distinct TTVs characteristic of their own species. In this study, TTV DNA sequences were searched for in sera from nonhuman primates by two PCR methods with primers deduced from noncoding and coding regions (21, 22, 24). The results indicate that nonhuman primates are infected with TTVs of their own species, having marked sequence divergence from human TTV, and that chimpanzees can be cross-infected with human TTV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nonhuman primates.

Ten Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata), four red-bellied tamarins (Saguinus labiatus), six cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus), and five douroucoulis (Aotes trivirgatus) were caught in the wild in 1977 and their sera were collected. A total of 104 chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) were kept at Kumamoto Primates Park (Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. Ltd., Kumamoto, Japan). Of these, 46 were wild caught and the remaining 58 were bred at the Primates Park. Sera were collected from the chimpanzees during September 1991 through October 1997 during their health checkups. The serum samples had been kept at −20°C until testing. The animals studied were maintained and monitored under conditions that met all relevant requirements for the humane care and ethical use of primates in an approved facility.

Extraction of nucleic acids and amplification by PCR.

Nucleic acids were extracted from 50 to 100 μl of serum by using a High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) and dissolved in 40 to 80 μl of nuclease-free distilled water, and a 20-μl portion served as a template for amplification by PCR. TTV DNA was detected by the following two methods in the presence of Perkin-Elmer AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, N.J.) and the primers listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Positions and nucleotide sequences of oligonucleotide primers

| Primer | Polarity | Nucleotidea positions | Nucleotide sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | |||

| NG059 | Sense | 1900–1923 | 5′-ACA GAC AGA GGA GAA GGC AAC ATG-3′ |

| NG061 | Sense | 1915–1938 | 5′-GGC AAC ATG YTR TGG ATA GAC TGG-3′ |

| NG063 | Antisense | 2161–2185 | 5′-CTG GCA TTT TAC CAT TTC CAA AGT T-3′ |

| NG132 | Antisense | 204–223 | 5′-AGC CCG AAT TGC CCC TTG AC-3′ |

| NG133 | Sense | 91–115 | 5′-GTA AGT GCA CTT CCG AAT GGC TGA G-3′ |

| NG134 | Sense | 114–136 | 5′-AGT TTT CCA CGC CCG TCC GCA GC-3′ |

| NG147 | Antisense | 211–233 | 5′-GCC AGT CCC GAG CCC GAA TTG CC-3′ |

| NG162 | Sense | 1996–2015 | 5′-CTA CCT CTA TGG GCA GCA GC-3′ |

| NG164 | Sense | 2020–2040 | 5′-GGA TAT GTA GAA TTT TGT GCA-3′ |

| NG165 | Antisense | 2126–2145 | 5′-AAA GCC TTT TGT GGG GTC TG-3′ |

| NG174 | Antisense | 2065–2084 | 5′-ACA CAT CTG CAG TTG TGT TC-3′ |

| NG177 | Sense | 1955–1974 | 5′-GCA TAT ACG ACC CCT CTA AG-3′ |

| NG178 | Antisense | 2130–2149 | 5′-GGA CGA AGC CCC AGT TGT CA-3′ |

| NG180 | Antisense | 2115–2134 | 5′-GTG GGT CGT TGG TGT CTA TC-3′ |

| NG193 | Sense | 2061–2080 | 5′-CAT AGA CAT GAA CGC CAG AG-3′ |

| NG198 | Sense | 1924–1943 | 5′-CTG TGG ATA GAC TGG CTA AC-3′ |

| Chimpanzee | |||

| NG241 | Sense | N22 region | 5′-CAC AAA AGC AGA CAC CAA GTA C-3′ |

| NG242 | Antisense | N22 region | 5′-CCT TCT TTG TCT ATG TCG CC-3′ |

| NG243 | Sense | N22 region | 5′-GCC AGT TAG GAC CGT ACS AAG ACC-3′ |

| NG244 | Antisense | N22 region | 5′-GGC TGT GTG TAG GGR CAT TTG-3′ |

| NG255 | Sense | UTR | 5′-GGG TAC CCG AGG TGA GTT TAC ACA C-3′ |

| NG256 | Antisense | UTR | 5′-GCC CTC GGG ACG ACG CGC GGT CGG-3′ |

| NG257 | Sense | UTR | 5′-GGG TAC CCG AGG TGA GTT TAC ACA CCG AGG-3′ |

| NG258 | Antisense | UTR | 5′-GCC CTC GGG ACG ACG CGC GGT CGG CGG CAG-3′ |

| Japanese macaque | |||

| NG232 | Sense | UTR | 5′-CGG AGG TGA GTT TAC ACA CCG CAG-3′ |

| NG233 | Antisense | UTR | 5′-GCA CCC GCC CAG GGC TGG TCT GG-3′ |

| NG234 | Sense | UTR | 5′-CGG AGG TGA GTT TAC ACA CCG CAG TCA AGG-3′ |

| NG235 | Antisense | UTR | 5′-GCA CCC GCC CAG GGC TGG TCT GGG GTC G-3′ |

| Douroucouli | |||

| NG236 | Sense | UTR | 5′-CCG AGC GAC TGG GCG GGA GCC GGG-3′ |

| NG237 | Antisense | UTR | 5′-TCG CGC CTC GCT CCG CTC GGC AGA-3′ |

| NG238 | Sense | UTR | 5′-CCG AGC GAC TGG GCG GGA GCC GGG AAC ATC C-3′ |

| NG239 | Antisense | UTR | 5′-TCG CGC CTC GCT CCG CTC GGC AGA CGC TGC-3′ |

Nucleotide positions are numbered with reference to the TA278 isolate of 3739 nt (22).

(i) UTR PCR.

UTR PCR was performed by the method described previously (24). The first round of PCR was performed with primers NG133 (sense) and NG147 (antisense) for 35 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s, with an additional 7 min for the last cycle), and the second round was carried out with primers NG134 (sense) and NG132 (antisense) for 25 cycles under the same conditions. The amplification products of the first round of PCR were 143 bp long, and those of the second round were 110 bp.

(ii) N22 PCR.

N22 PCR was performed as documented elsewhere by PCR with seminested primers (21, 22). The first round of PCR was performed with primers NG059 (sense) and NG063 (antisense) for 35 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s, with an additional 7 min for the last cycle), and the second round was carried out with primers NG061 (sense) and NG063 (antisense) for 25 cycles under the same conditions. The amplification products of the first round of PCR were 286 bp, and those of the second round were 271 bp.

PCR with inverted nested primers for the amplification of full-length TTV genomes of nonhuman primates.

Full-length TTV genomes of nonhuman primates were amplified by PCR with inverted nested primers in the presence of TaKaRa LA Taq with GC buffer (TaKaRa Shuzo, Shiga, Japan). DNAs extracted from chimpanzee sera were used as templates in the first round of PCR with primers NG255 (sense) and NG256 (antisense) for 35 cycles (94°C for 45 s, with an additional 3 min in the first cycle; 63°C for 45 s; and 72°C for 4 min, with an additional 7 min for the last cycle). The second round of PCR was performed, on a 1-μl portion of the products of the first-round PCR, for 25 cycles with primers NG257 (sense) and NG258 (antisense) under the same conditions. The final products of PCR were run by electrophoresis on 1% (wt/vol) SeaKem GTG agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) to detect the band with the size of full genomic TTV (3.5 to 3.8 kb).

To amplify the genomic DNA of Japanese macaque TTV, DNA extracted from serum was amplified by first-round PCR with primers NG232 and NG233 followed by second-round PCR with primers NG234 and NG235, and for amplification of DNA of douroucouli TTV, DNA was amplified by first-round PCR with primers NG236 and NG237 and then by second-round PCR with primers NG238 and NG239 under the same conditions.

Genotyping human and chimpanzee TTVs.

Human TTV was classified into four common genotypes, 1, 2, 3, and 4 (24). By using amplification products of the first-round PCR with primers NG059 and NG063 as a template (286 bp), PCR was performed with type-specific primers in the presence of Perkin-Elmer AmpliTaq Gold (Roche Molecular Systems) for 25 cycles (95°C for 30 s, with an additional 9 min in the first cycle; 58°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 40 s, with an additional 7 min in the last cycle). The primer pairs specific for genotypes 1 to 4, respectively, were NG162-NG165, NG198-NG174, NG193-NG180, and NG177-NG178 (Table 1). The amplification products were subjected to electrophoresis on a 2 to 4% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel (FMC BioProducts) to detect bands compatible with genotypes 1 to 4, which were sized at 150, 161, 74, and 195 bp, respectively.

Genetic groups of chimpanzee TTV were determined by PCR with primers specific for two groups designated A and B. The primer pair for group A was NG241-NG242, and that for group B was NG243-NG244; they generated amplification products of 135 and 71 bp, respectively.

Determination of TTV sequences.

The amplification products separated on agarose gel electrophoresis were extracted and ligated into pT7 BlueT-Vector (Novagen Inc., Madison, Wisc.) or M13 phage vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Escherichia coli was transformed with them, and by using the obtained recombinant DNA as a template, both strands were sequenced by the Thermo Sequenase fluorescence-labelled primer cycle-sequencing kit with 7-deaza-dGTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, England) or BigDyeTerminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). At least three clones each were sequenced for the PCR products, and when they showed less than a 3% difference, the consensus sequence was adopted. When two or more kinds of clones with greater than 10% sequence difference were obtained, three clones each of a kind were sequenced to determine the consensus sequence. They were distinguished by Roman numerals after the clone name.

Computer analysis of nucleotide sequences.

Sequence analysis was performed with Genetyx-Mac version 10.1 (Software Development, Tokyo, Japan) and ODEN version 1.1.1 of DNA DataBank of Japan (National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan) (7). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (16).

Detection of antibodies to human TTV of genotype 1a.

Anti-TTV antibody of a specificity for genotype 1a was determined by immunoprecipitation with ICN/Cappel goat antiserum to human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (whole molecule) (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Aurora, Ohio) by the method described previously (34). In brief, the test serum was incubated with TTV particles of genotype 1a extracted from human feces and then separated into supernatant and precipitate fractions. Thereafter, TTV DNAs in both fractions were determined by PCR with a primer pair (NG164-NG165) specific for genotype 1a. The amplification products were subjected to electrophoresis and scanned for a band at an expected size (126 bp). The presence of a higher density of TTV DNA in the precipitate than in the supernatant fraction was taken as evidence for anti-TTV antibody of genotype 1a in the test serum.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data in this paper have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB032277 to AB032346.

RESULTS

Detection of TTV DNA in sera from nonhuman primates.

By means of UTR PCR (24), TTV DNA was detected in sera from 102 (98%) of 104 chimpanzees, 9 (90%) of 10 Japanese macaques, 4 (100%) of 4 red-bellied tamarins, 5 (83%) of 6 cotton-top tamarins, and all 5 (100%) of 5 douroucoulis. Thus, TTV DNA was highly prevalent in nonhuman primates, being detected in 125 (97%) of the 129 animals tested. Unlike the detection of TTV DNA in human sera, TTV DNAs in sera from nonhuman primates, except for those from chimpanzees, were amplified by the first but not the second round of PCR.

UTR sequences of TTV DNA in nonhuman primates.

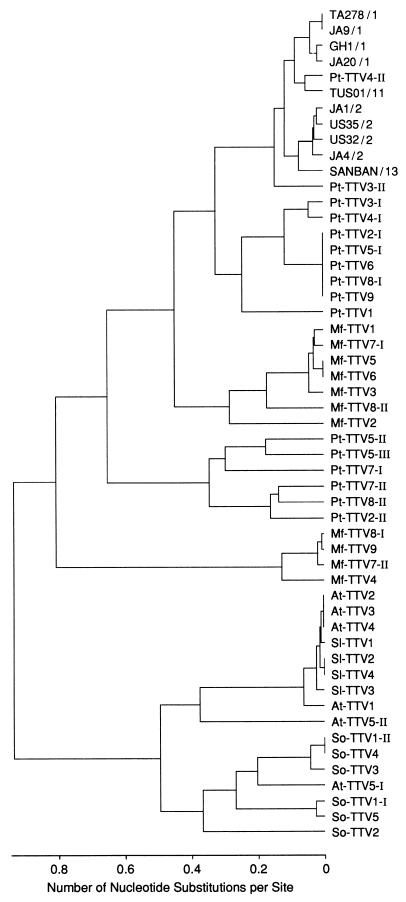

Amplification products of the first round of UTR PCR measuring 90 to 106 bp (primer sequences at both ends excluded) were sequenced for nine randomly selected chimpanzees and all 23 animals of the other species testing positive, including 9 Japanese macaques, 9 red-bellied or cotton-top tamarins and 5 douroucoulis. They were analyzed phylogenetically along with corresponding sequences of 10 human TTV isolates of various genotypes for which the entire sequence is determined (Fig. 1). The tree revealed phylogenetic differences of TTV depending on the species. Due to these phylogenetic differences, TTV of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) is referred to as Pt-TTV, that of Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) is referred to as Mf-TTV, that of red-bellied tamarins (Saguinus labiatus) is referred to as Sl-TTV, that of cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus) is referred to as So-TTV, and that of douroucoulis (Aotes trivirgatus) is referred to as At-TTV.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the UTR sequences of 53 TTV isolates from humans and nonhuman primates. The tree is constructed from the nucleotide sequence of the products by the first round of UTR PCR of 90 to 106 nt (primer sequences at both ends excluded). It consists of 10 human TTV isolates of various genotypes (indicated after the slashes), as well as 9 Pt-TTV isolates (Pt-TTV1 to Pt-TTV9) randomly selected from 102 chimpanzees (P. troglodytes), 9 TTV isolates from Japanese macaques (M. fuscata) (Mf-TTV1 to Mf-TTV9), 4 TTV isolates from red-bellied tamarins (S. labiatus) (Sl-TTV1 to Sl-TTV4), 5 TTV isolates from cotton-top tamarins (S. oedipus) (So-TTV1 to So-TTV5), and 5 TTV isolates from douroucoulis (A. trivirgatus) (At-TTV1 to At-TTV5). For animals from which two or three kinds of TTV isolates of different sequences were recovered, the isolates are distinguished by roman numerals at the end. All the included human TTV isolates have been characterized by the full-length sequences (2, 5, 14, 23).

Human TTV isolates were 85 to 100% similar within the UTR sequence, irrespective of distinct genotypes. The prototype TTV isolate (TA278) of genotype 1a was 66 to 90% similar to Pt-TTV, 62 to 72% similar to Mf-TTV, and only up to 57% similar to Sl-TTV/So-TTV and At-TTV.

Two genetic groups of Pt-TTV with intragroup differences of 75.8 to 100% and 70.0 to 88.0% and intergroup differences of 59.8 to 63.8% were recognized. Some Pt-TTVs did not belong to either of the two groups and possessed UTR sequences that clustered with human TTVs. They were Pt-TTV4-II and Pt-TTV3-II and were 83.2 to 93.7% and 82.1 to 86.5%, respectively, similar to human TTVs (Fig. 1).

Likewise, two genetic groups of Mf-TTV with intragroup differences of 79.2 to 100% and 85.8 to 100% and intergroup differences of 58.5 to 63.2% were identified. Similarly, two genetic groups of tamarin TTV were found, one infecting red-bellied tamarins (Sl-TTV) and the other infecting cotton-top tamarins (So-TTV), with intragroup differences of 96.9 to 100% and 67.6 to 100%, respectively, and intergroup differences of 68.6 to 71.8%. A single genetic group of At-TTV was detected in four of the five douroucoulis tested (At-TTV1 to At-TTV4), which showed 91.8 to 100% sequence similarity to Sl-TTV. In addition, two distinct strains of At-TTV were recovered from the remaining douroucouli (At-TTV5-I and At-TTV5-II). Of these, At-TTV5-I showed 95.0 to 96.0% similarity to three TTV isolates from cotton-top tamarins (So-TTV2, So-TTV3, and So-TTV4). Since At-TTV5-II showed only 64.7 to 84.6% similarity to any At-TTVs or tamarin TTVs, there would be three distinct genetic groups of At-TTV.

Circular structure and genomic length of TTVs from nonhuman primates.

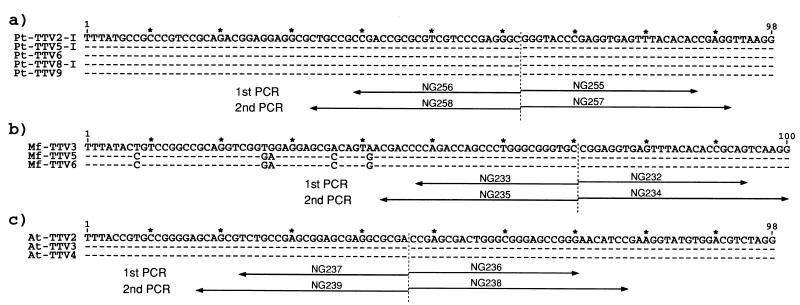

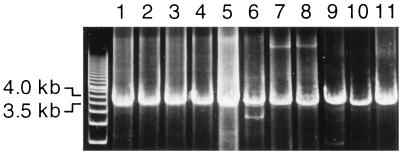

Primers were deduced from the UTR sequences of Pt-TTV, Mf-TTV, and At-TTV which spanned 98, 100, and 98 nt (primer sequences at both ends excluded), respectively (Fig. 2). They were used as inverted nested primers for amplification of the full-length circular TTV genomes by PCR. Five Pt-TTV isolates, three Mf-TTV isolates, and three At-TTV isolates were amplified, and the products of the second-round PCR were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis to estimate the genomic size (Fig. 3). They migrated to positions of 3.5 to 3.8 kb, which are comparable to or a little smaller than human TTV DNAs, which are 3,808 to 3,853 nt (2, 5, 13, 14, 23).

FIG. 2.

Inverted nested primers designed on the basis of UTR sequences of nonhuman primate TTVs. TTV isolates which have similar sequences in the amplification products of UTR PCR were selected. Primers were deduced from five sequences of Pt-TTV DNAs from chimpanzees (a), three sequences of Mf-TTV DNAs from Japanese macaques (b), and three sequences of At-TTV DNAs from douroucoulis (c) for the amplification of full-length circular TTV genomes by PCR. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the amplification products of full-length TTV DNAs by PCR with inverted nested primers. Full-length circular TTV genomes were amplified from five chimpanzees (lanes 1 to 5), three Japanese macaques (lanes 6 to 8), and three douroucoulis (lanes 9 to 11) and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. The pattern of a molecular size marker (500-bp DNA ladder [TaKaRa Shuzo]) is shown on the left.

Detection of human TTV DNA in nonhuman primates.

On the assumption that species specificity of TTV would be expressed more explicitly in the nucleotide sequence of coding regions, in spite of the universal detection of animal TTVs by UTR PCR, a sequence resembling human TTV DNA was searched for in sera from nonhuman primates by PCR with seminested primers deduced from the N22 region (21, 22); it is located in open reading frame 1 of the human TTV genome. Sera from 49 (47%) of the 104 chimpanzees tested positive for TTV DNA by N22 PCR. One-third of the chimpanzee TTV DNAs were amplified only by the first round of N22 PCR or only weakly by the second round of N22 PCR.

Genotypes of TTV DNAs in chimpanzees were determined by PCR with primer pairs specific for one or the other of genotypes 1 to 4 of human TTV (Table 2). TTV DNA in only one chimpanzee was determined to be genotype 1; TTV DNAs in the remaining 46 chimpanzees were not classified into any of genotypes 1 to 4. By contrast, TTV DNAs in 29 Japanese blood donors with viremia were classified into genotypes 1 to 4 or mixed genotypes (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Classification of TTV DNA by PCR with primers specific for two genetic groups of chimpanzee TTV or four common genotypes of human TTVa

| Animal or human | Total no. | No. (%) in Pt-TTV genetic group:

|

No. with human TTV genotype:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A and B | UCb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mixed | UCb | ||

| Chimpanzees | |||||||||||

| Bred | |||||||||||

| Experiments (+) | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Experiments (−) | 12 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Subtotal | 18 | 3 (17) | 5 (28) | 3 (17) | 7 (39) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Wild caught | |||||||||||

| Experiments (+) | 26 | 11 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Experiments (−) | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Subtotal | 31 | 14 (42) | 6 (19) | 8 (26) | 3 (10) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Total | 49 | 17 (35) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 10 (20) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 |

| Humans | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

Sera from chimpanzees testing positive for TTV DNA by N22 PCR (21, 22) were tested for genetic groups of Pt-TTV DNA by PCR with group-specific primers (see Materials and Methods), as well as for the genotypes of human TTV (24). As controls, sera from blood donors testing positive for TTV DNA by N22 PCR were tested in parallel.

UC, unclassifiable.

By sequence analysis of the amplification products of N22 PCR, TTV DNA in the single positive chimpanzee was determined to be genotype 1a, with 99% sequence similarity to the prototype human TTV isolate (TA278) of the same genotype. Of the 49 chimpanzees with TTV DNA in serum, 32 had been inoculated previously with human materials contaminated with HBV or suspected in the transmission of non-A, non-B hepatitis virus (later found to be hepatitis C virus). The single chimpanzee with TTV DNA of genotype 1a was among the 32 which had participated in transmission experiments. Hence, this chimpanzee may have been infected with human TTV in the experiments and retained it persistently.

Sequence analysis and genotypes of Pt-TTV.

Five chimpanzees were randomly selected from among the 49 chimpanzees that tested positive for TTV DNA by N22 PCR in serum. Then sequences within the N22 region of Pt-TTV DNAs were determined. The five Pt-TTV isolates were classified into one group of three and one group of two, with an intragroup similarity of 87.8 to 91.9% and 92.4%, respectively, and an intergroup similarity of 61.7 to 67.4%. They were assigned to genetic groups A and B, respectively, both of which would be specific for Pt-TTV.

Primers specific for groups A and B were deduced from sequences of the N22 region for classifying Pt-TTV by PCR. By using products by the first round of N22 PCR as a template, grouping was performed on TTV DNAs from 49 chimpanzees (Table 2). Group A was detected in 17 (35%) of them, group B was detected in 11 (22%), and a mixed infection with groups A and B was detected in 11 (22%); neither group A nor group B was detected in the remaining 10 (20%). Group A was found less often and mixed infection with groups A and B was more frequent in the 18 chimpanzees bred in the institution than in the 31 chimpanzees caught in the wild. The single chimpanzee infected with human TTV of genotype 1a was doubly infected with Pt-TTVs of groups A and B.

The occurrence of groups A and B, as well as a mixed infection with the two groups, was no different between bred and wild-caught chimpanzees, or between the chimpanzees with and without previous transmission experiments. Group A or B was not detected in any TTV DNAs from the 29 human carriers.

Sequence analysis was performed on TTV DNAs from 10 chimpanzees not classifiable into group A or B. Sequences of the DNA from nine of them were 90.5 to 100% similar to one another, indicating that they belonged to the same genetic group. The remaining sequence was only 52.8 to 55.8% similar to the others, and so it belonged to another genetic group. The 10 sequences were less than 59% similar to group A or B sequences. The genetic group represented by the nine Pt-TTVs was provisionally designated group C, and that represented by the single Pt-TTV was tentatively named group D.

Sequences were determined for TTV DNAs isolated from five chimpanzees and classified into group A by PCR with type-specific primers (Pt-TTV14 to Pt-TTV18) and those isolated from seven chimpanzees and classified into group B (Pt-TTV21 to Pt-TTV27). They were found to be similar to the sequences of three isolates of group A (Pt-TTV11 to Pt-TTV13) and those of two isolates of group B (Pt-TTV19 and Pt-TTV20), respectively, for which sequences had been determined for designing type-specific primers.

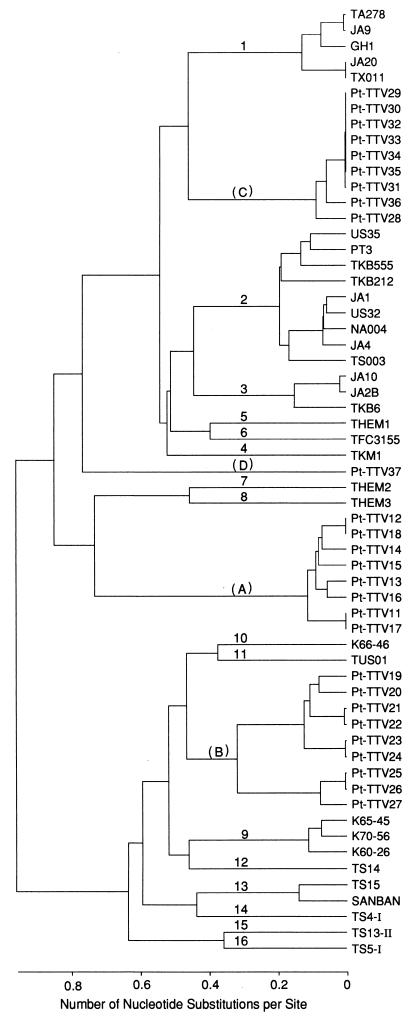

A pairwise analysis was performed on sequences of 222 to 225 nt in the N22 region of Pt-TTV DNAs from 27 chimpanzees, along with those of human TTV DNAs representing 16 distinct genotypes (2, 5, 14, 22–24). It gave rise to four distinct genetic groups of Pt-TTV (A, B, C, and D), which were clearly distinguished from any of the 16 genotypes of human TTV and were separated by a sequence difference of 35.0 to 52.8% from one another.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed on the basis of 27 sequences of Pt-TTV DNA, including 8 of genotype A, 9 of genotype B, 9 of genotype C, and 1 of genotype D, as well as on sequences of human TTV DNA of 16 distinct genotypes (Fig. 4). The tree exhibited four genetic groups of Pt-TTV (A through D) and 16 genotypes of human TTV (1 through 16). Genetic groups of Pt-TTV or genotypes of TTV did not cluster to make clades of their own but, rather, intermingled with one another.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the N22-region sequences of TTV isolates from humans and chimpanzees. The tree is constructed from the nucleotide sequence of the products by N22 PCR (222 to 225 nt; primer sequences at both ends excluded) of 27 Pt-TTV isolates (Pt-TTV11 to Pt-TTV37) in four genetic groups, along with 33 human TTV isolates of 16 distinct genotypes (2, 5, 14, 22–24). Genetic groups (A to D) of Pt-TTV are indicated in parentheses. Pt-TTV11 to Pt-TTV18 belonged to group A, and Pt-TTV19 to Pt-TTV27 belonged to group B. Pt-TTV28 to Pt-TTV36 were not amplified by primers specific for group A or B (tentatively assigned group C), similarly to Pt-TTV37 (group D).

Detection of TTV DNA by UTR PCR and N22 PCR in chimpanzees in various age groups.

The 58 bred chimpanzees were aged 5 months to 11 years, while the 46 wild-caught chimpanzees were estimated to be aged 12 to 26 years (Table 3). TTV DNA was tested for by UTR PCR and N22 PCR.

TABLE 3.

TTV DNA in bred or wild-caught chimpanzees in various age groups

| Origin and age (yr) | No. | No. (%) with TTV DNA detected by:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| UTR PCR | N22 PCR | ||

| Bred | |||

| <1 | 4 | 2 (50) | 0 |

| 1 | 7 | 7 (100) | 0 |

| 2–4 | 22 | 22 (100) | 7 (32) |

| 5–11 | 25 | 25 (100) | 11 (44) |

| Subtotal | 58 | 56 (97) | 18 (31) |

| Wild-caught | |||

| 12–19 | 32 | 32 (100) | 22 (69) |

| 20–26 | 14 | 14 (100) | 9 (64) |

| Subtotal | 46 | 46 (100) | 31 (67) |

| Total | 104 | 102 (98) | 49 (47) |

Of a total of 104 chimpanzees, TTV DNA was detected in 102 (98%) by UTR PCR. The two chimpanzees without detectable TTV DNA were aged 5 and 7 months, and both were bred. TTV DNA was detected by N22 PCR more frequently in wild-caught than bred chimpanzees (31 of 46 [67%] and 18 of 58 [31%], respectively; P = 0.0002 [chi-square test]). All the 11 bred chimpanzees younger than 2 years were negative for TTV DNA by N22 PCR.

Antibodies to human TTV in chimpanzee sera.

The detection of TTV of genotype 1a in a single chimpanzee, previously inoculated with human materials, indicated that other chimpanzees may have been exposed to and infected with human TTV during transmission experiments but resolved the infection. Anti-TTV specific for genotype 1a was tested for in sera from 53 chimpanzees by immune precipitation (34); the results are shown in Table 4. Anti-TTV was found more frequently in the chimpanzees that had undergone transmission experiments than in those that had not in the total (8 of 28 [29%] and 3 of 35 [9%]; P = 0.038), bred (2 of 4 [50%] and 3 of 29 [10%]; P = 0.038), and wild-caught (6 of 14 [43%] and 0 of 6 [0%]; P = 0.055) populations. There were no appreciable differences, however, in the prevalence of anti-TTV between bred and wild-caught chimpanzees (6 of 20 [30%] and 5 of 33 [15%], respectively; P = 0.196).

TABLE 4.

TTV DNA of genotype 1a and IgG anti-TTV of the same genotype in bred and wild-caught chimpanzees that had or had not been used in previous transmission experiments

| Origin | No. | No. (%) with:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| TTV DNA (genotype 1a) | IgG anti-TTVa (genotype 1a) | ||

| Bred | |||

| Experiments (+) | 13 | 0/13 | 2/4 (50) |

| Experiments (−) | 45 | 0/45 | 3/29 (10) |

| Subtotal | 58 | 0/58 | 5/33 (15) |

| Wild-caught | |||

| Experiments (+) | 40 | 1/40 (3) | 6/14 (43) |

| Experiments (−) | 6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| Subtotal | 46 | 1/46 (2) | 6/20 (30) |

IgG anti-TTV was determined by immunoprecipitation (34) in 53 selected chimpanzees.

DISCUSSION

There have been accumulating lines of evidence to indicate that TTV commonly infects humans (1, 15, 19, 22, 30–32, 34; L. E. Prescott, P. Simmonds, and International Collaborators, Letter, N. Engl. J. Med. 339:776–777, 1998). Although TTV was discovered recently, in 1997 (19), it seems to be well-adapted virus of humans and has been a persistent source of infection since the distant past. TTV has an extraordinarily wide range of sequence divergence, on the basis of which it is classified into at least 16 genotypes based on a difference of >30% in the sequence of a coding region (open reading frame 1) spanning 222 to 231 nt (the N22 region) (15, 21–24, 26, 29–32). The nucleotide sequence of the noncoding region is much more highly conserved, and PCR with primers deduced from it enables the detection of TTV DNA, irrespective of various genotypes (24, 28).

By using UTR PCR (24), nucleotide sequences resembling the human TTV genome were tested for in sera from nonhuman primates. Sera from 125 (97%) of 129 animals of the five species examined, including chimpanzees, Japanese macaques, red-bellied and cotton-top tamarins, and douroucoulis, tested positive for TTV DNA by UTR PCR. In normal blood donors, TTV DNA is also detected by UTR PCR very frequently (93 to 97%) (24, 28). In general, sequences of UTR of TTV DNAs from each nonhuman primate clustered in a phylogenetic analysis, indicating that there are TTVs similar to human TTV but specific for nonhuman primates. In addition, genetic groups with considerable sequence divergence were detected for TTV of each species.

With the use of PCR involving inverted nested primers, deduced from UTR sequences of animal TTVs, full-length genomic TTV DNAs were amplified for all nonhuman primates. The genomic lengths of animal TTVs ranged from 3.5 to 3.8 kb, comparable to or a little shorter than the reported human TTV genomes sized 3,808 to 3,853 nt (2, 5, 13, 14, 23). By the principle of PCR with inverted primers, they were circular like human TTV (13, 14, 23). There remains little doubt about a family of viruses characterized by a circular DNA genome of 3.5 to 3.9 kb infecting humans and nonhuman primates with very high prevalence rates.

Recently, Leary et al. (9) reported frequent detection of TTV DNA in farm animals, including 19% of chickens, 20% of pigs, 25% of cows, and 30% of sheep, by their improved PCR methods. On the basis of their findings, they speculated that domesticated farm animals would serve as a source of TTV infection in humans. Whether species-specific TTVs are present or whether TTV represents a single virus taxon infecting humans and animals alike is a matter of great concern, because it should influence the epidemiology of TTV infection in humans.

It should be determined whether the TTV DNA sequences found by Leary et al. (9) are relevant to the work of Tischer et al. (33), who found antibodies cross-reactive with porcine circovirus in many cows, mice, and humans. However, the genomic DNAs of three reported circoviruses, i.e., porcine circovirus, chicken anemia virus, and beak and feather disease virus of parrots, have sizes of 1,768 to 2,319 nt (17); they are much smaller than those of human and nonhuman primate TTVs.

Although human TTV shares UTR sequences TTVs of nonhuman primates and those of farm animals, it may differ in sequences in coding regions, reflecting species-specific TTVs. This concept was borne out by the detection of TTV DNA by PCR with seminested primers deduced from a coding-region sequence (N22 region) in open reading frame 1. By means of N22 PCR, TTV DNA was detected in sera from 49 (48%) of the 102 chimpanzees that tested positive for TTV DNA by UTR PCR. By contrast, TTV DNA was not detected by N22 PCR in any of the other 23 nonhuman primates, although they possessed TTV DNA detectable by UTR PCR. Hence, Pt-TTV would be more closely related to human TTV than to TTVs of the other nonhuman primates. Our results corroborate those of Verschoor et al. (37), who detected TTV DNAs in 60 (49%) of 123 chimpanzees of P. troglodytes verus species and 4 (67%) of 6 chimpanzees of P. paniscus species by PCR with primers deduced from the N22 region. They could not detect TTV DNAs by the N22 PCR in any other primates; we could not, either.

At least four genetic groups of Pt-TTV were identified which differ by >30% in the N22 region sequence of 222 to 225 nt. They were provisionally designated groups A, B, C, and D and differ from any of the 16 genotypes of TTV by >30% in sequence (Fig. 4). The four genetic groups of Pt-TTV, however, did not cluster in a clade separate from the 16 TTV genotypes in a phylogenetic tree. Human TTV genotypes intermingled with genetic groups of Pt-TTV. Furthermore, some Pt-TTVs had noncoding region sequences which were very similar to that of human TTV (Fig. 1). Hence, although no group A or B Pt-TTV sequences were detected in any sera containing TTV DNA from 29 Japanese blood donors tested, it is possible that some Pt-TTVs belong to unknown genotypes of human TTV. These results are in line with the report of Verschoor et al. (37); they observed that P. troglodytes verus TTV strains cluster with human TTV of a certain genotype while P. paniscus TTV strains cluster with that of another genotype. The relationship between these animal TTVs and a particular genotype of human TTV was much closer than that among human TTV strains of distinct genotypes. A situation like this was observed also for TTVs from tamarins and douroucoulises (Fig. 1).

Human and chimpanzee TTVs do not cluster into species-specific monophyla. Rather, some genetic groups of human and chimpanzee TTVs cluster to make human/chimpanzee clades, as has been reported for T-cell leukemia virus type 1 and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (4, 8, 39). Therefore, some genetic groups of Pt-TTV are closer to certain genotypes of human TTV and vice versa. How this happened is a matter of conjecture. There might have been a common ancestor of TTV that infected both species before they divided some 3 million years ago.

It is more likely that cross-species infection occurred from chimpanzee to humans via animal handling, particularly for viruses transmitted through contamination of blood, represented by retroviruses. Interspecies infection would be much easier for TTV, which is excreted in the feces for a possible fecal-oral transmission route (21). It would be worthwhile to test for Pt-TTV in sera from the individuals in Africa, where the chimpanzees were caught and analyze it phylogenetically.

One of our chimpanzees was infected with human TTV of genotype 1a, confirming cross-species infection as reported by Mushahwar et al. (14). This chimpanzee was among the 53 that participated in transmission experiments with human hepatitis viruses in the past. When anti-TTV of genotype 1a was tested for in the other 53 chimpanzees by immunoprecipitation (34), it was detected in 11. Anti-TTV of genotype 1a was detected significantly more frequently in the chimpanzees used in transmission experiments than in those not used in these experiments. Hence, at least 11 more chimpanzees had been infected with TTV of genotype 1a, most probably through human materials contaminated with TTV of this genotype, and resolved the infection by raising humoral antibodies. The low rate of persistent infection (1 of 12) suggested that infection of chimpanzees with human TTV would tend to be transient. This view is consistent with the resolution of TTV infection in both chimpanzees inoculated with human TTV (14).

Cross-species infection with human and chimpanzee viruses in limited genetic groups is not unprecedented. Some genetic groups of simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1 cluster with human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, and, on that basis, an interspecies transmission is postulated (8, 38). Recently, Gao et al. reported a lineage of simian immunodeficiency virus of chimpanzees that is closely related to all groups of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (4) and speculated that chimpanzees are the primary reservoir of this virus.

It would be premature to conceive a single taxon of TTV based on the frequent detection of TTV DNAs by UTR PCR in humans, nonhuman primates, and farm animals and to presume invariable zoonotic infection among them (9). Despite a common UTR sequence which forms TTVs of various species into a family, there may be species specificity for TTVs and cross-species infection would be restricted to closely related species. Comparison of full-length sequences of animal TTV DNAs will disclose similarities and differences in genomic areas among the members of the TTV family and will help classify TTVs and define their zoonotic infections. It is now feasible, by means of PCRs with inverted nested primers, to amplify the full-length genomic DNA of TTVs of chimpanzees and other nonhuman primates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charlton M, Adjei P, Poterucha J, Zein N, Moore B, Therneau T, Krom R, Wiesner R. TT-virus infection in North American blood donors, patients with fulminant hepatic failure, and cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;28:839–842. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erker J C, Leary T P, Desai S M, Chalmers M L, Mushahwar I K. Analyses of TT virus full-length genomic sequences. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1743–1750. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-7-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galibert F, Chen T N, Mandart E. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned woodchuck hepatitis virus genome: comparison with the hepatitis B virus sequence. J Virol. 1982;41:51–65. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.1.51-65.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson D L, Chen Y, Rodenburg C M, Michael S F, Cummins L B, Arthur L O, Peeters M, Shaw G M, Sharp P M, Hahn B H. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999;397:436–441. doi: 10.1038/17130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hijikata M, Takahashi K, Mishiro S. Complete circular DNA genome of a TT virus variant (isolate name SANBAN) and 44 partial ORF2 sequences implicating a great degree of diversity beyond genotypes. Virology. 1999;260:17–22. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohne M, Berg T, Muller A R, Schreier E. Detection of sequences of TT virus, a novel DNA virus, in German patients. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2761–2764. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-11-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ina Y. ODEN: a program package for molecular evolutionary analysis and database search of DNA and amino acid sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:11–12. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koralnik I J, Boeri E, Saxinger W C, Monico A L, Fullen J, Gessain A, Guo H G, Gallo R C, Markham P, Kalyanaraman V. Phylogenetic associations of human and simian T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I strains: evidence for interspecies transmission. J Virol. 1994;68:2693–2707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2693-2707.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leary T P, Erker J C, Chalmers M L, Desai S M, Mushahwar I K. Improved detection systems for TT virus reveal high prevalence in humans, non-human primates and farm animals. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2115–2120. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukert P D, de Boer G F, Dale J L, Keese P, McNulty M S, Randers J W, Tisher I. Family Circoviridae. In: Murphy F A, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Ghabrial S A, Jarvis A W, Martelli G P, Mayo M A, Summers M D, editors. Virus taxonomy. Classification and nomenclature of viruses: sixth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 166–168. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandart E, Kay A, Galibert F. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned duck hepatitis B virus genome: comparison with woodchuck and human hepatitis B virus sequences. J Virol. 1984;49:782–792. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.3.782-792.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng X J, Halbur P G, Shapiro M S, Govindarajan S, Bruna J D, Mushahwar I K, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Genetic and experimental evidence for cross-species infection by swine hepatitis E virus. J Virol. 1998;72:9714–9721. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9714-9721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyata H, Tsunoda H, Kazi A, Yamada A, Khan M A, Murakami J, Kamahora T, Shiraki K, Hino S. Identification of a novel GC-rich 113-nucleotide region to complete the circular, single-stranded DNA genome of TT virus, the first human circovirus. J Virol. 1999;73:3582–3586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3582-3586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mushahwar I K, Erker J C, Muerhoff A S, Leary T P, Simons J N, Birkenmeyer L G, Chalmers M L, Pilot-Matias T J, Dexai S M. Molecular and biophysical characterization of TT virus: evidence for a new virus family infecting humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3177–3182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naoumov N V, Petrova E P, Thomas M G, Williams R. Presence of a newly described human DNA virus (TTV) in patients with liver disease. Lancet. 1998;352:195–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nei M. Phylogenetic trees. In: Nei M, editor. Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York, N.Y: Columbia University Press; 1987. pp. 287–326. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niagro F D, Forsthoefel A N, Lawther R P, Kamalanathan L, Ritchie B W, Latimer K S, Lukert P D. Beak and feather disease virus and porcine circovirus genomes: intermediates between the geminiviruses and plant circoviruses. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1723–1744. doi: 10.1007/s007050050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niel C, de Oliveira J M, Ross R S, Gomes S A, Roggendorf M, Viazov S. High prevalence of TT virus infection in Brazilian blood donors. J Med Virol. 1999;57:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norder H, Ebert J W, Fields H A, Mushahwar I K, Magnius L O. Complete sequencing of a gibbon hepatitis B virus genome reveals a unique genotype distantly related to the chimpanzee hepatitis B virus. Virology. 1996;218:214–223. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto H, Akahane Y, Ukita M, Fukuda M, Tsuda F, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Fecal excretion of a nonenveloped DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion non-A-G hepatitis. J Med Virol. 1998;56:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto H, Nishizawa T, Kato N, Ukita M, Ikeda H, Iizuka H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Hepatol Res. 1998;10:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto H, Nishizawa T, Ukita M, Takahashi M, Fukuda M, Iizuka H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. The entire nucleotide sequence of a TT virus isolate from the United States (TUS01): comparison with reported isolates and phylogenetic analysis. Virology. 1999;259:437–448. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto H, Takahashi M, Nishizawa T, Ukita M, Fukuda M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Marked genomic heterogeneity and frequent mixed infection of TT virus demonstrated by PCR with primers from coding and noncoding regions. Virology. 1999;259:428–436. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeger C, Ganem D, Varmus H E. Nucleotide sequence of an infectious molecularly cloned genome of ground squirrel hepatitis virus. J Virol. 1984;51:367–375. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.2.367-375.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmonds P, Davidson F, Lycett C, Prescott L E, MacDonald D M, Ellender J, Yap P L, Ludlam C A, Haydon G H, Gillon J, Jarvis L M. Detection of a novel DNA virus (TTV) in blood donors and blood products. Lancet. 1998;352:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprengel R, Kaleta E F, Will H. Isolation and characterization of a hepatitis B virus endemic in herons. J Virol. 1988;62:3832–3839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.10.3832-3839.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K, Hoshino H, Ohta Y, Yoshida N, Mishiro S. Very high prevalence of TT virus (TTV) infection in general population of Japan revealed by a new set of PCR primers. Hepatol Res. 1998;12:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takayama S, Yamazaki S, Matsuo S, Sugii S. Multiple infection of TT virus (TTV) with different genotypes in Japanese hemophiliacs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:208–211. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka H, Okamoto H, Luengrojanakul P, Chainuvati T, Tsuda F, Tanaka T, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Infection with an unenveloped DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion non-A to G hepatitis in hepatitis patients and healthy blood donors in Thailand. J Med Virol. 1998;56:234–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199811)56:3<234::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Orito E, Nakano T, Kato T, Ding X, Ohno T, Ueda R, Sonoda S, Tajima K, Miura T, Hayami M. A new genotype of TT virus (TTV) infection among Colombian native Indians. J Med Virol. 1999;57:264–268. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199903)57:3<264::aid-jmv9>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Orito E, Ohno T, Nakano T, Kato T, Kato H, Mukaide M, Park Y M, Kim B S, Ueda R. New genotypes of TT virus (TTV) and a genotyping assay based on restriction fragment length polymorphism. FEBS Lett. 1998;437:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tischer I, Bode L, Apodaca J, Timm H, Peters D, Rasch R, Pociuli S, Gerike E. Presence of antibodies reacting with porcine circovirus in sera of humans, mice, and cattle. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1427–1439. doi: 10.1007/BF01322669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuda F, Okamoto H, Ukita M, Tanaka T, Akahane Y, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Determination of antibodies to TT virus (TTV) and application to blood donors and patients with post-transfusion non-A to G hepatitis in Japan. J Virol Methods. 1999;77:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ukita M, Okamoto H, Kato N, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Excretion into bile of a novel unenveloped DNA virus (TT virus) associated with acute and chronic non-A-G hepatitis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1245–1248. doi: 10.1086/314716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaudin M, Wolstenholme A J, Tsiquaye K N, Zuckerman A J, Harrison T J. The complete nucleotide sequence of the genome of a hepatitis B virus isolated from a naturally infected chimpanzee. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1383–1389. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-6-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verschoor E J, Langenhuijzen S, Heeney J L. TT virus (TTV) of non-human primates and their relationship to the human TTV genotypes. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2491–2499. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-9-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voevodin A F, Johnson B K, Samilchuk E I, Stone G A, Druilhet R, Greer W J, Gibbs C J., Jr Phylogenetic analysis of simian T-lymphotropic virus Type I (STLV-I) in common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): evidence for interspecies transmission of the virus between chimpanzees and humans in Central Africa. Virology. 1997;238:212–220. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warren K S, Heeney J L, Swan R A, Heriyanto, Verschoor E J. A new group of hepadnaviruses naturally infecting orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) J Virol. 1999;73:7860–7865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7860-7865.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodfield D G, Gane E, Okamoto H. Hepatitis TT virus is present in New Zealand. N Z J Med. 1998;111:195–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]