Abstract

The viral E2 protein is a major regulator of papillomavirus DNA replication. An important way to influence viral replication is through modulation of the activity of the E2 protein. This could occur through the action of truncated E2 proteins, called E2 repressors, whose role in the replication cycle of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) has not been determined. In this study, using cell lines that contain episomal copies of the “high-risk” HPV type 31 (HPV31), we have identified viral transcripts with a splice from nucleotide (nt) 1296 to 3295. These transcripts are similar to RNAs from other animal and human papillomaviruses and have the potential to fuse a small open reading frame (E8) to the C terminus of E2, resulting in an E8 ^E2C fusion protein. E8 ^E2C transcripts were present throughout the complete replication cycle of HPV31. A genetic analysis of E8 ^E2C in the context of the HPV31 genome revealed that mutation of the single ATG of the E8 gene, introduction of a stop codon downstream of the ATG, or disruption of the splice donor site at nt 1296 led to a dramatic 30- to 40-fold increase in the transient DNA replication levels in both normal and immortalized human keratinocytes. High-level expression of E8 ^E2C from heterologous vectors was found to inhibit E1-E2-dependent DNA replication of an HPV31 origin of replication construct as well as to interfere with E2's ability to transactivate reporter gene constructs. In addition, HPV31 E8 ^E2C strongly repressed the basal activity of the major viral early promoter P97 independent of E2. E8 ^E2C may therefore exert its negative effect on viral DNA replication through modulating E2's ability to enhance E1-dependent DNA replication as well as by regulating viral gene expression. Surprisingly, HPV31 genomes that were unable to express E8 ^E2C could not be maintained extrachromosomally in human keratinocytes in long-term assays despite high transient DNA replication levels. This suggests that the E8 ^E2C protein may play a role in copy number control as well as in the stable maintenance of HPV episomes.

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) induce hyperproliferative epithelial lesions at numerous body locations. Infection of the genital tract by a subset of HPV types, termed high-risk types, results in lesions that have the potential to progress to carcinomas (45). It is believed that all HPV infections take place in the basal layers of either cutaneous or mucosal epithelia. Following virus entry and the establishment of genomes as extrachromosomal elements, infected cells migrate from the basal layer and differentiate in the suprabasal layers. These differentiated cells are able to initiate productive virus replication and virion synthesis (19). In tissue culture, monolayer cultures of undifferentiated cells containing bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV1) or high-risk HPVs can maintain constant levels of extrachromosomal multicopy plasmids (19, 39). In these cells only the early region of the viral genome is transcribed. These monolayer cultures are thought to mimic virus-infected keratinocytes in the basal layer.

Many in vitro studies of papillomavirus replication have been carried out with BPV1 and the immortalized mouse C127 cell line. Recently a tissue culture model for the productive life cycle of high-risk HPV replication has been developed which allows for analysis of viral functions in the natural host cell (10, 11, 30). Use of these systems has demonstrated that many, but not all, of the basic requirements for DNA replication are conserved among different papillomaviruses. Papillomavirus replication requires two virus-encoded DNA-binding proteins, E1 and E2, as well as the viral origin of replication consisting of binding sites for E1 and E2 (39). The E1 protein functions as an initiator, as it binds specifically to the viral origin of replication, unwinds DNA, and interacts with several host cell proteins required for DNA replication (39). The viral E2 protein functions as an accessory replication factor by forming a complex with E1 and thereby increasing origin recognition by E1 (39). E2 has also been shown to regulate papillomavirus replication through its ability to modulate viral gene expression (26).

Papillomavirus DNA replication must be regulated in basal cells so that a constant copy number is maintained. An important way by which replication can be regulated is through a modulation of the activity of the E2 protein. This could occur by direct control of the levels of E2 expression as well as through the action of truncated E2 proteins, called E2 repressors. In BPV1, these repressors are generated either through translation initiation within the C terminus of E2 (E2C or E2TR) or by splicing of a small alternative open reading frame (ORF) in the E1 gene, termed E8, to the C terminus of E2 (E8-E2) (7, 13, 20, 21). Both the E8-E2 and E2C proteins contain the C-terminal domain of E2, which mediates dimerization of E2 proteins and specific DNA binding, but lack the N-terminal domain responsible for stimulation of transcription and replication (26). Both proteins inhibit E2 transactivation and focus formation when expressed in trans from expression vectors (7, 20, 22). Repressors appear to act as antagonists of E2 either by displacement of E2 molecules from their binding sites or through formation of inactive heterodimers (1, 24, 27).

Genetic analyses of BPV1 mutants revealed that the loss of E2C led to a 10- to 20-fold increase in DNA copy numbers in transformed cells, suggesting that E2C repressors may negatively regulate viral DNA replication and gene transcription (22, 36). In contrast, the loss of E8-E2 showed no detectable phenotype (22). The combination of both mutants resulted in a lower stable genome copy number and a reduced transformation frequency (22). Two recent observations indicated that E2 repressors may play an even more complex role in the viral replication cycle. The transformation defect of the E2 repressor double mutant could be reverted when specific phosphorylation sites that are common to all E2 species were mutated (23). Furthermore, E2-E2C heterodimers support in vitro replication of BPV1 DNA as well as E2 homodimers (24), suggesting that E2C proteins may not inhibit DNA replication by heterodimer formation. Overall, the role of the BPV1 E2 repressors in the viral life cycle remains complex and not fully defined.

The role of E2 repressors in the replication cycle of HPVs remains unclear. So far, in cells infected with high-risk HPV types 16 and 33 as well as low-risk HPV11, transcripts resembling the BPV1 E8-E2 message have been identified (7, 8, 37, 38). The putative proteins encoded by these transcripts have been termed E2C for HPV11, -16, and -33, but they are more similar to the BPV1 E8-E2 protein, since they all contain a small conserved E8 ORF fused to the C terminus of E2. The E8 ORF presumably provides the AUG for initiation of translation of the HPV E8 ^E2C fusion proteins. Transient overexpression assays and in vitro replication studies have suggested that HPV E2C proteins act as negative regulators of E2 (3–6, 25). However, since papillomavirus transcripts are generally polycistronic, it is unclear if and when the genes encoding E2 repressors are translated into proteins. In the present study, we have investigated the role of the E8 ^E2C protein in the viral replication cycle of the high-risk HPV31 by a genetic approach that allows the analysis of mutated HPV31 genomes in transient and stable assays. We find that the E8 ^E2C gene encodes a strong negative regulator of papillomavirus DNA replication and transcription, which acts early in the viral replication cycle to negatively regulate the copy number. Despite being a negative regulator, E8 ^E2C, surprisingly, is required for the long-term maintenance of HPV31 episomes in normal human keratinocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA analysis.

RNA was isolated from monolayer and raft cultures of CIN612-9E cells with TriZol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the directions of the manufacturer. Two micrograms of total cellular RNA was used in reverse transcription reactions with random hexanucleotide primers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) according to the directions of the manufacturer. RNasin (Promega) was added to prevent RNA degradation. HPV31 cDNAs were amplified from 1/10 of the cDNA made from monolayer cell RNA with primers P40 (HPV31 nucleotides [nt] 1270 to 1290; sense) and P3 (HPV31 nt 4050 to 4031; antisense). cDNA was denatured for 2 min at 94°C and amplified with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) in 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% gelatin, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 100 pmol of each primer for 50 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2.5 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were gel purified, reamplified for 15 cycles under the same conditions, cloned into PCRScript (Stratagene), and analyzed by DNA sequencing (Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit; Amersham Life Science). P65-E2B clones were derived from RNA isolated from raft cultures of CIN612-9E cells treated with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate. The cDNA was amplified with primers P65 (HPV31 nt 1212 to 1232; sense) and E2B (HPV31 nt 3836 to 3816; antisense) for 50 cycles as described above and cloned into PCRScript without reamplification. Antisense RNA probes were synthesized in vitro with an RNA transcription kit (Stratagene) and T7 RNA polymerase and used in RNase protection assays as previously described (16).

Recombinant plasmids.

Plasmid pBR322.HPV31 contains the HPV31 genome inserted into the EcoRI site of pBR322 (11). Plasmid pHPV31-E1N-TTL contains a stop codon in the E1 gene at nt 1039 (40). Mutations in the genomic context of HPV31 (E8-1250-STOP, E8-ATG, E8-1289-STOP, and SD1296 [see Fig. 3 for the exact changes]) were introduced by overlap-extension PCR (12). The mutated fragments were used to replace the BanII-SwaI fragment (HPV31 nt 815 to 1645) in pBR322.HPV31 and were verified by sequencing after cloning. In addition to the changes in E8, the mutation in plasmid pE8-1250-STOP changes the E1 residue 131 from aspartic acid to valine, and in plasmid pE8-STOP-1289, E1 residue 144 is changed from valine to isoleucine. The luciferase reporter plasmids pGL31URR and p6xE2BS-luc, as well as eukaryotic expression vectors for HPV31 E1 (pSG31E1) and E2 (pSXE2), have been described previously (9, 41). Plasmid pSGE8 ^E2C contains a reconstructed cDNA consisting of HPV31 nt 1212 to 1296 ^3295 to 3830 and was constructed as follows: an EcoRI fragment from plasmid pP65,E2B clone 1072 was excised and used to replace the EcoRI fragment in pSGE2 (9). The P63,P95 clone used for RNase protection analysis was generated by recombinant PCR as follows: The 5′ end of E1 (nt 878 to 1344) was amplified from HPV31b DNA with primers P66 (HPV31 nt 878 to 898; sense) and P7 (HPV31 nt 1341 to 1325; antisense) and cloned into PCRScript to generate pP66,P7. Nucleotides 878 to 1232 were amplified from this plasmid with primers P66 and P92 (HPV31 nt 1232 to 1212; antisense) and isolated by gel purification. The cDNA containing the 1296 ^3295 splice junction was amplified from pP65,E2B clone 1072 (nt 1212 to 1296 ^3295 to 3835) with primers P65 and P21b (HPV31 nt 3517 to 3496; antisense) and gel purified. Equimolar amounts of these PCR products were combined and amplified with flanking primers P66 and P21b. The recombinant PCR product containing nt 878 to 1296 ^3295 to 3835 was gel purified and cloned into PCRScript to generate pP66,P21b clone 7. The sequences between nt 991 and 3379 were subcloned by amplification with primers P63 and P95 to generate clone E8 ^E2C pP63,P95 (nt 991 to 1296 ^3295 to 3379). The sequence of this clone was verified by DNA sequence analysis.

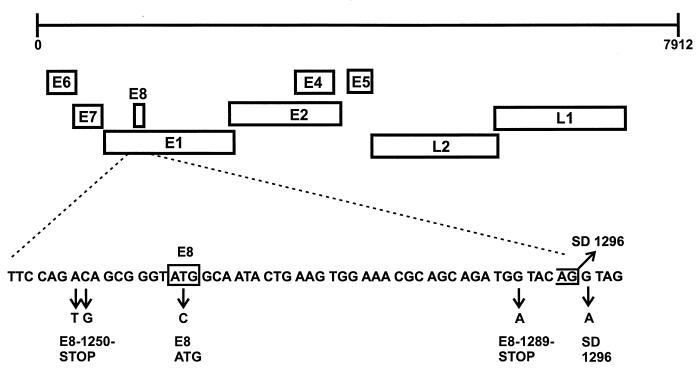

FIG. 3.

Diagram of mutations introduced into the HPV31 E8 ^E2C gene. The partial nucleotide sequence of the HPV31 E8 gene is shown below the genome of HPV31. The only ATG codon in E8 is enclosed in a box, and the splice donor consensus site at nt 1296 is indicated by an open box. Mutated nucleotides leading to the introduction of stop codons in E8 (E8-1250-STOP and E8-1289-STOP), the disruption of the ATG codon (E8-ATG), and the disruption of the splice donor consensus sequence (SD1296) are indicated below the arrows.

Generation, culture, and induction of differentiation of keratinocytes.

Normal human keratinocytes were derived from human foreskin epithelium and were maintained in keratinocyte growth medium (Clonetics). SCC13 cells, a human squamous cell carcinoma cell line (35); HPV31 genome transfectants; and the CIN612-9E cell lines were grown in E medium with mitomycin C-treated NIH 3T3 J2 fibroblast feeder cells (11, 29). Organotypic raft cultures of CIN612-9E cells were grown in the presence of tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate as described previously (29). Generation of HPV31 genome transfectants was performed as described previously (11) and was repeated three times with normal human keratinocytes isolated from two different donors.

Transient luciferase expression assay.

Approximately 105 SCC13 cells were seeded into 35-mm-diameter dishes the day before transfection. The next day the cells were cotransfected with the amounts of luciferase reporters and HPV31 expression vectors indicated in the figure legends. The total amount of transfected DNA was kept constant by adding the parental pSG5 expression plasmid DNA. Transfections and luciferase assays were performed as described previously (41) with the exception that 5 μl of Lipofectamine (Life Technologies) and 100 μl of lysis buffer per 35-mm-diameter dish were used. The results (see Fig. 6 and 7) are the average of several independent transfections as indicated in the legends.

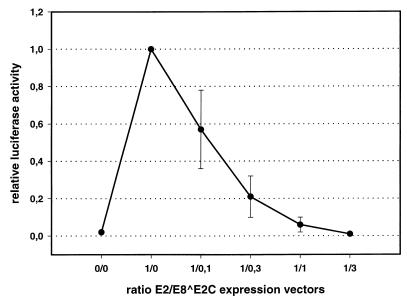

FIG. 6.

E8 ^E2C inhibits E2-mediated transactivation. SCC13 cells were transfected with 200 ng of the luciferase reporter plasmid p6xE2BS-luc alone or together with a fixed amount of the HPV31 E2 expression vector and increasing amounts of the HPV31 E8 ^E2C expression vector at the ratios indicated. Activities are expressed relative to transactivation by E2 alone. The data represent the average value of four independent experiments, and the standard deviation is indicated by error bars.

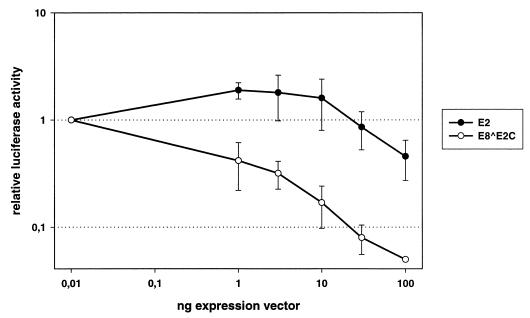

FIG. 7.

E8 ^E2C inhibits E2-independent expression of the HPV31 upstream regulatory region. SCC13 cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL31URR alone or together with increasing amounts of either the HPV31 E2 expression vector or the HPV31 E8 ^E2C expression vector. Luciferase activities are expressed relative to the activity in the absence of expression vectors, which corresponds to the value of 0.01 ng of expression vector. The data presented are the average of three independent experiments and the standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

Transient replication assay.

Replication assays with reporter plasmids were performed with SCC13 cells as described previously (41). Plasmids (3 μg) containing the various HPV31 genomes were digested with EcoRI to release the viral genome from the cloning vector and then religated under diluted conditions to facilitate intramolecular ligation. After ethanol precipitation, the ligation efficiencies of the products were monitored by agarose electrophoresis, and equal amounts were then transfected into 5 × 105 SCC13 or normal human keratinocytes grown in 60-mm-diameter dishes with the use of 15 μl of Lipofectamine and OptiMem (Life Technologies) or keratinocyte growth medium, respectively. The next day, the cells were split onto 100-mm-diameter dishes, and low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated 120 h posttransfection. The DNA was digested with DpnI to remove bacterial input DNA and BanII (for HPV genomes) or HpaI (for replication reporter constructs) to linearize the replicated DNA and subjected to Southern analysis.

Southern blot analysis.

Analysis of viral DNA by Southern blotting was essentially performed as described previously (41). Briefly, digested DNAs were separated in a 0.8% agarose gel at 70 V for 16 h. The DNA was then transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (GeneScreen Plus; Dupont, NEN) by alkaline transfer according to the manufacturer's instructions. Specific 32P-labeled probes to detect viral fragments were generated with the Ready-to-go DNA labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia). Hybridization was carried out in 50% formamide–4× SSPE–5× Denhardt's solution–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–20 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml at 42°C overnight (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7]). The blots were washed twice at room temperature in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS, followed by two washes in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS and then twice in 0.1× SSC–1% SDS at 50°C (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate). Hybridizing DNA species were visualized by autoradiography and quantitated by phosphorimaging on a Fuji BAS reader 1800.

RESULTS

Detection of spliced E8 ^E2C transcripts in cell lines containing episomal copies of HPV31.

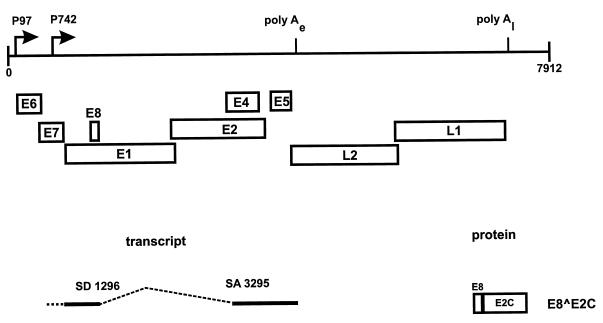

To investigate the role of potential E2 repressor species in the productive viral life cycle of high-risk HPVs, we first sought to identify transcripts that encode the spliced E8 ^E2C species. Transcripts encoding E8 ^E2C have been previously detected in cells infected with HPV11, -16, and -33 and BPV1 (7, 8, 37, 38). A common feature of these transcripts is their use of a splice donor site in the 5′ part of the E1 region, which is linked to a splice acceptor site in the E2-E4 region. To investigate whether a similar transcript is also present in HPV31-infected cells, we isolated RNA from the CIN612-9E cell line, which was derived from a CIN1 lesion and shown to contain approximately 50 copies of extrachromosomal HPV31b (2). RNA from CIN612-9E cells grown in monolayer culture was incubated with reverse transcriptase followed by PCR amplification with primers P40 (nt 1270 to 1290) and P3 (nt 4050 to 4031) from the 5′ part of the E1 region and the 3′ end of the early region of the HPV31 genome, respectively. To determine the exact nature of the transcript(s), the amplified cDNAs were cloned and sequenced. This analysis revealed that the majority of the clones (11 of 14) used a splice donor site at nt 1296 attached to a splice acceptor site at nt 3295 (Fig. 1). In the remaining three clones the splice donor at nt 1296 was connected to acceptor sites at nt 3298 or 3331, respectively. We have focused our attention on the major transcript species (1296 ^3295), since it could generate a protein that is very similar to the previously described HPV E2C and BPV1 E8-E2 proteins. The E8 ORF of HPV31 extends from nt 1204 to 1297, with a single ATG start codon at position 1259. To ensure that the potential E8 ATG start codon is included in the spliced 1296 ^3295 RNA, a reverse transcription-PCR experiment was conducted with primer P65 (nt 1212 to 1232) and primer E2B (3816 to 3836). The resulting products were cloned and sequenced. This revealed that transcripts were present that extend from nt 1212, utilize the 1296 ^3295 splice, and proceed to nt 3836. These transcripts can encode a complete E8 ^E2C fusion protein (Fig. 1).

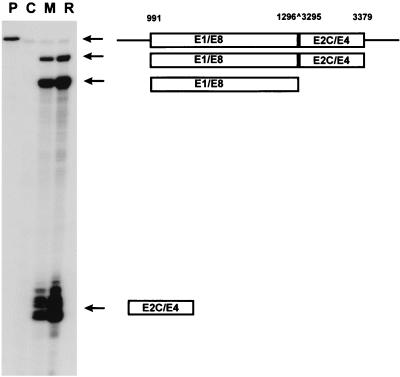

FIG. 1.

Identification of cDNA for E8 ^E2C from RNA from a cell line which maintains viral episomes. The linearized genome of HPV31 (nt 1 to 7912) with the various ORFs (E1 to E8, L1, and L2), the major early promoter P97 and the major late promoter P742, and the early (poly Ae) and late (poly Al) polyadenylation sites are shown at the top. The structure of a transcript that uses a splice donor site at nt 1296 which is linked to a splice acceptor site at nt 3295 is presented below. This transcript would create a fusion between a small ORF from the E1 region (E8) and the C-terminal portion of E2 (E2C), giving rise to an E8 ^E2C protein.

Next, it was important to determine whether the 1296 ^3295 transcript was abundantly expressed in cells, as PCR can detect low levels of aberrantly spliced messages. We therefore used RNase protection analysis to determine the levels of the 1296 ^3225 transcript in CIN612-9E cells. Total RNA was isolated from cells that were either grown in monolayer culture or induced to differentiate in the organotypic raft culture system. In this way, changes in the levels of this transcript during the nonproductive and the differentiation-dependent productive viral replication cycles could be determined. To specifically detect the spliced 1296 ^3295 transcript, we used a reconstructed cDNA (HPV31 nt 991 to 1296 ^3295 to 3397) to generate the antisense probe for RNase protection analysis. Three major protected species were detected: a 305-nt band derived from the E1-E8 exon alone (nt 991 to 1296), an 84-nt band protected by the E2C-E4 exon alone (nt 3295 to 3379), and a 389-nt band derived from a transcript containing the 1296 ^3295 splice junction and initiated upstream of nt 991 (Fig. 2). No fragments corresponding to transcripts initiated within E1 were observed.

FIG. 2.

RNase protection of RNA from undifferentiated and differentiated CIN612-9E cells. An E8 ^E2C transcript is present in HPV31-positive cells grown in monolayer culture or induced to differentiate in the raft system. RNase protection analysis was done of total RNA (20 μg) isolated from CIN612-9E grown in monolayer (M) or induced to differentiate in the organotypic raft culture system (R). A cDNA probe consisting of HPV31 nt 991 to 1296 (E1-E8) spliced to 3295 to 3379 (E2C-E4) was used as an antisense probe. In lane C the probe was hybridized to tRNA before digestion. Lane P received undigested probe. The protected fragments and their coding potentials are indicated on the right by arrows.

Levels of the spliced E8 ^E2C RNA changed only moderately after differentiation in raft cultures (Fig. 2, lane R), which indicated that an E8 ^E2C-encoding message is present in detectable amounts in monolayer cells and that the levels of this message are not strongly influenced by cell differentiation. An increase in the levels of transcripts containing the E2C-E4 exon was observed upon induction of differentiation. This was due to an increase of the E1 ^E4 transcript levels, which are spliced from nt 877 to 3295 and represent one of the major viral mRNAs expressed in the productive life cycle of HPV31 (16). These studies have identified a polycistronic transcript which would have the capacity to encode an E8 ^E2C protein initiated at the AUG codon at nt 1259 as well as the viral E5 protein. If this transcript is initiated by either the major early promoter P97 or the major late promoter P742, it can also encode a C-terminally truncated E1 protein (E1N) similar to the BPV E1M protein in an ORF overlapping the E8 ^E2C ORF (43).

The E8 ^E2C gene is a repressor of the transient replication of the HPV31 genome in keratinocytes.

To genetically investigate the role of the E8 ^E2C gene, we generated four different mutations in the E8 ORF or in the splice donor site used for the generation of E8 ^E2C in the whole genomic context of HPV31 (Fig. 3). The E8 ORF of HPV31 extends from 1204 to 1297 and could encode a 31-amino-acid peptide with a single ATG start codon at position 1259. The E8-1250-STOP mutation introduces a stop codon into the E8 ORF upstream of the single ATG codon, the second mutation changes the E8 ATG codon to ACG (E8-ATG), the third mutation places a stop codon into the E8 gene downstream of the ATG (E8-1289-STOP), and the fourth mutation disrupts the splice donor consensus signal at nt 1296 (SD1296). The E8 ATG and splice donor mutations are silent in the overlapping E1 replication gene, whereas both E8 stop codon mutations additionally introduce single-amino-acid changes in E1 (see Materials and Methods).

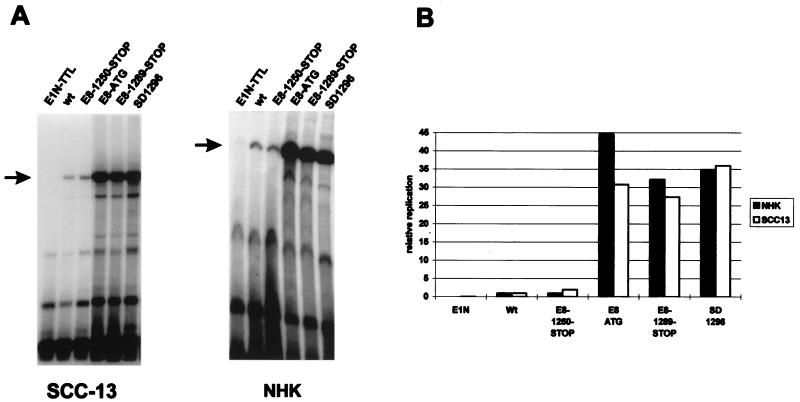

Since E2 repressor proteins have been implicated in the E2-mediated control of DNA replication and viral gene expression, we examined the effects of these mutants in a transient replication assay in keratinocytes that measures both transcription and replication properties of viral genomes (44). The wild-type HPV31 genome and genomes with mutations in E8 or in E1 alone were transfected into the immortalized keratinocyte cell line SCC13 or into normal human keratinocytes. The transient replication efficiency of the transfected genomes was determined 120 h posttransfection by DpnI digestion of low-molecular-weight DNA followed by Southern blotting (Fig. 4A). Quantitation of the linearized, DpnI-resistant DNA by phosphorimager analysis revealed no major differences in the relative replication efficiencies of the different genomes among normal and immortalized keratinocytes (Fig. 4B). The E1N-TTL mutant genome, which is unable to transiently replicate, served as a control for the completeness of the DpnI digestion (40). The E8-1250-STOP mutant genome was found to replicate at levels comparable to those of the wild type. Mutation of the E8 ATG, introduction of a stop codon downstream of the ATG (E8-1289-STOP), or disruption of the splice donor site at nt 1296 (SD1296) each led to a dramatic 30- to 40-fold increase in DNA replication levels. Several conclusions can be drawn from this experiment. First, the E8 ^E2C factor is a negative regulator of the transient replication of HPV31 DNA in undifferentiated keratinocytes. Second, we conclude that the E8 ^E2C ORF is most likely translated into a protein which initiates at the ATG at nt 1259, since introduction of a stop codon upstream (E8-1250-STOP) did not influence replication levels. Finally, since the phenotype of the SD1296 mutation was similar to those of the E8-ATG and E8-1289-STOP mutations, it appears that the E8 ^E2C fusion protein and not an N-terminally truncated E1N protein is responsible for the repression of transient replication.

FIG. 4.

Transient replication data for HPV31 mutant genomes. Immortalized (SCC13) or normal human keratinocytes (NHK) were transfected with religated HPV31 genomes as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed for transient replication by Southern blotting. (A) Representative autoradiographs of transient replication experiments performed with human keratinocytes. The arrows designate DpnI-resistant, replicated HPV31 DNA. All lanes from the SCC13 gel are from a single exposure of the same gel. (B) Quantitative analysis of the replication levels of the HPV31 genomes in panel A. The replication efficiencies of HPV31 mutant genomes are expressed relative to the HPV31 wild-type (wt) genome. Similar relative replication levels were observed in two other independent experiments.

The E8 ^E2C gene is a negative regulator of viral transcription and DNA replication.

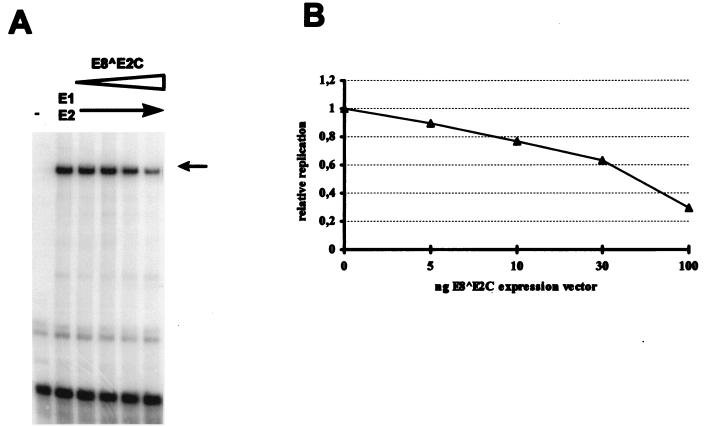

To gain further insight into the function of E8 ^E2C, we cloned a cDNA for E8 ^E2C into the eukaryotic expression vector pSG5. Expression of a full-length E8 ^E2C protein from this vector was verified by in vitro translation in the presence of [35S]methionine and by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown). We first investigated whether the E8 ^E2C protein modulates the E1-E2-dependent replication of the HPV31 origin of replication. The reporter plasmid pGL31URR contains the complete upstream regulatory region of HPV31, which includes the replication origin, all four conserved E2 binding sites, and the start site for the major early promoter P97 (41). The origin reporter plasmid was transfected into SCC13 cells by itself or together with expression vectors for the HPV31 E1 and HPV31 E2 proteins and various amounts of the E8 ^E2C expression vector. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated 72 h posttransfection, digested with DpnI, and analyzed by Southern blotting for replication of the reporter plasmid followed by quantitative phosphorimager analysis (Fig. 5B). The replication efficiency of the HPV31 ori plasmid was found to decrease in a concentration-dependent manner with the addition of increasing amounts of E8 ^E2C expression vector (Fig. 5A). This indicated that E8 ^E2C is an inhibitor of the E1-E2-dependent DNA replication of the viral origin, as has been demonstrated for the HPV11 E2C protein and the BPV1 E2C protein (5, 24, 25).

FIG. 5.

High-level expression of E8 ^E2C inhibits the E1-E2-dependent transient replication of an HPV31 origin-containing plasmid. SCC13 cells were transfected with 500 ng of plasmid pGL31URR alone (−) or cotransfected with 1 μg of HPV31 E1 expression vector, 100 ng of HPV31 E2 expression vector, and increasing amounts of HPV31 E8 ^E2C expression vector. Low-molecular-weight DNA was analyzed for replication of the reporter plasmid by Southern blotting. (A) Representative autoradiograph of a transient replication experiment. The position of the DpnI-resistant, replicated DNA is indicated by an arrow. (B) Quantitation of the experiment shown in panel A. Replication levels are expressed relative to the replication of pGL31URR in the presence of HPV31 E1 and E2 vectors. Similar results were obtained in three other independent experiments.

Since the transient replication capacity of the HPV31 genome is also determined by the expression levels of the viral replication proteins (14), it was necessary to investigate the ability of E8 ^E2C to modulate E2-dependent and -independent viral gene expression. We first measured the influence of E8 ^E2C on the E2-dependent transactivation of a reporter construct, in which six E2 binding sites are cloned upstream of a minimal simian virus 40 early promoter that drives luciferase expression (p6XE2BS-luc [41]). The luciferase reporter plasmid was transfected alone or together with an E2 expression vector (pSXE2) and increasing amounts of the E8 ^E2C expression vector into SCC13 cells. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and analyzed for luciferase activity. Cotransfection of E2 stimulated luciferase expression from the reporter construct an average of 50-fold. The addition of increasing amounts of the E8 ^E2C expression vector to the transient assays decreased luciferase activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6). This indicated that E8 ^E2C inhibits E2 transactivation. These data confirm and extend previous reports demonstrating that E8 ^E2C proteins (BPV1 E8-E2 and HPV11 and -16 E2C) function as E2 antagonists in replication and transcription assays (3–6, 25).

It was also important to determine whether E8 ^E2C has the ability to modulate viral transcription independently of E2. It has been reported that full-length E2 and its derivatives repress the activity of the major early HPV promoter commonly found immediately upstream of the E6 ORF (26), which is called P97 in HPV31 and P105 in HPV18. This promoter is responsible for the expression of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 and may also direct expression of replication proteins E1 and E2 (14, 16, 31, 34, 40, 42). To determine the extent to which E2 and E8 ^E2C modulate the HPV31 P97 promoter, a reporter plasmid which consists of the complete upstream regulatory region of HPV31 driving luciferase expression was cotransfected with increasing amounts of E2 or E8 ^E2C expression vectors into SCC13 cells (Fig. 7). Cotransfection of small amounts of E2 expression vector increased luciferase activity 1.8-fold, but this weak stimulation was no longer evident at 30 ng of input vector. With large amounts of E2 expression vector, luciferase activity was inhibited to about 46% of the basal levels. In contrast, cotransfection of increasing amounts of E8 ^E2C expression vector resulted in an immediate repression of P97 activity, which was further reduced to 5% of the basal activity with large amounts of input vector. This indicated that E8 ^E2C is a repressor of P97 activity, whereas full-length E2 both weakly activates and weakly represses P97.

Expression of E8 ^E2C is required for long-term episomal maintenance of HPV31 in normal human keratinocytes.

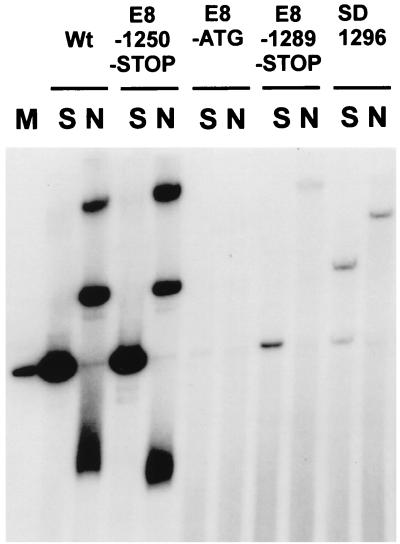

We next asked whether viral genomes with mutations in the E8 gene are stably maintained as extrachromosomal elements with altered copy numbers in human keratinocytes. Wild-type and mutated genomes were excised from the vector backbone, religated, and cotransfected with the pSV2neo plasmid into normal human keratinocytes. After selection of the cells with G418, colonies were pooled and expanded. Four to 6 weeks after transfection, total cellular DNA was extracted from the cells at passage 2, digested with restriction enzymes, and analyzed by Southern blotting (Fig. 8). Digestion of DNA from HPV31 wild-type and E8-1250-STOP-transfected cells with a noncutting enzyme (Fig. 8, lanes N) for HPV31 DNA gave rise to several prominent species which correspond to supercoiled, linear, open-circle, and concatemeric forms of viral DNA, consistent with extrachromosomal maintenance of HPV31 in these cell lines. In contrast, the pattern obtained with DNA from E8-ATG-, E8-1289-STOP-, and SD1296-transfected cells revealed only bands corresponding to high-molecular-weight DNA, consistent with viral DNA integrated into the host chromosomes. An off-size band obtained after digestion of DNA from SD1296-transfected cells with a single cutting enzyme (Fig. 8, lanes S) provided further evidence for the integration of the viral DNA, since this band is indicative of a joint fragment of viral and cellular DNA. Quantitative phosphorimaging analysis revealed that approximately 1 to 15 copies of viral DNA per cell were present in the E8-ATG, E8-1289-STOP, and SD1296 cell lines. We were able to detect extrachromosomal viral DNA in three independently generated HPV31 wild-type and E8-1250-STOP cell lines but found no evidence for extrachromosomal maintenance of E8 ^E2C mutants in transfected cells from the same experiments. This strongly suggests that E8 ^E2C mutant viral genomes cannot be maintained extrachromosomally, but we cannot rule out the possibility that these genomes are maintained extrachromosomally at copy numbers that are below one virus copy per cell. The presence of the mutations in the transfected cell lines was confirmed by PCR of viral DNA from total cellular DNA and sequence analysis (data not shown). This indicated that HPV31 genomes that are unable to express the E8 ^E2C gene cannot be stably maintained as episomes in normal human keratinocytes despite high transient replication levels.

FIG. 8.

E8 ^E2C mutant genomes fail to replicate as stable plasmids in long-term assays. Total cellular DNA (10 μg) from normal keratinocytes transfected with the HPV31 wild-type (Wt) or mutant (E8-1250-STOP, E8-ATG, E8-1289-STOP, and SD1296) genomes was isolated from pooled, G418-selected colonies at passage 2 and analyzed by Southern blotting. DNA was either digested with BamHI, a noncutter (N) of HPV31 DNA, or with EcoRV (S), which linearizes HPV31 genomes. Hybridizing species were detected with a 32P-labeled genomic HPV31 probe generated by random priming. Lane M received 100 pg of linearized HPV31 genome, which corresponds to 65 viral genomes per cell. The slightly different mobilities of viral DNA species of the HPV31 wild type compared to E8-1250-STOP in lanes N are due to gel artifacts and have not been observed in other experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have identified transcripts encoding E8 ^E2C repressor proteins from the high-risk-type HPV31 and demonstrated by genetic analysis that their expression is essential for copy number control as well as for the stable maintenance of HPV genomes as extrachromosomal elements in human keratinocytes. The E8-E2 protein was initially identified in BPV1-infected cells together with E2C as repressors of the action of the full-length E2 (7, 13, 20–22, 36). Genetic analysis of BPV1 indicated that E2C was the major negative regulator, whereas E8-E2 mutants only displayed a phenotype when combined with the E2C mutation (22, 36). In HPV31, no transcripts which would encode an E2C protein with a functional translation initiation codon have been identified (31, 32). This, together with our genetic data, indicates that E8 ^E2C is the major E2 repressor of HPV31. In addition, the only transcripts with the potential to encode E2 repressor proteins that have been identified in a variety of HPV types are equivalent to the BPV1 E8-E2 mRNA (7, 8, 37, 38).

Using keratinocytes that maintain stable episomal copies of HPV31 DNA, we detected transcripts which initiate upstream of nt 991 in the E1 ORF and are spliced from nt 1296 to 3295. These transcripts have coding potential for an E8 ^E2C fusion protein but may also encode a C-terminally truncated E1 protein (E1N). The transient replication properties of mutants (E8-ATG and E8-1289-STOP) in which only E8 ^E2C is mutated and that of a mutant (SD1296) where both E8 ^E2C and E1N are mutated were similar. This suggests that truncated E1 proteins do not play a major role in the transient replication of HPV31. Consistent with our observations, the BPV1 23-kDa truncated E1N phosphoprotein is not required for BPV1 replication in C127 cells (15). Finally, we were unable to detect any influence of an HPV31 E1N expression vector on E1-E2-dependent origin replication or on the activity of transcription reporter plasmids in transient assays (F. Stubenrauch, unpublished observations). If an HPV31 E1N protein exists, we believe it has a minimal effect on viral DNA replication in undifferentiated keratinocytes.

From the data presented, we cannot exclude the possibility that other HPV31 E2 repressor species are involved in the regulation of viral replication. There is evidence for HPV11 transcripts that would create fusion proteins between N-terminal portions of E1 and the E2C terminus, which inhibit E2 activity in reporter assays (4, 5). We have preliminary evidence that transcripts encoding E1N ^E2C fusion proteins similar to those detected in HPV11 are also expressed in cells maintaining HPV31 episomes (Stubenrauch et al., unpublished observations). In the case of HPV18, a transcriptional start site within the E2 ORF which might be used for the generation of an N-terminally truncated E2 protein similar to BPV1 E2C has been mapped on the basis of in vitro transcription and reporter constructs (18). While transcripts exhibiting a similar start site have been detected in HPV31, these messages would not encode a consensus translation start codon for an E2C protein (32).

In our study, mutation of the E8 ^E2C gene in the context of the intact viral genome increased transient replication of genomes approximately 30- to 40-fold over that seen with wild-type DNA. In addition, high-level expression of E8 ^E2C from heterologous vectors was found to inhibit E1-E2-dependent DNA replication of an HPV31 origin construct as well as to interfere with E2's ability to transactivate reporter gene constructs. These observations are consistent with the model in which E2 repressors inhibit E2 action by competition for binding sites and through heterodimer formation (1, 3–7, 20, 24, 25, 27). In addition to inhibiting E2 transactivation, HPV31 E8 ^E2C was found to strongly repress the major viral early promoter P97 independent of E2. This repression may regulate viral DNA replication levels by modulating the expression of the E1 and E2 replication proteins. Recent studies have suggested that a significant portion of E1- and E2-encoding transcripts initiate at P97 in HPV31 or P105 in HPV18 (14, 31, 34, 42). The full-length E2 protein represses P97 expression in large part by binding to the promoter-proximal E2 binding site 4 (HPV31-BS4). Mutation of this E2 binding site results in enhanced transient replication of HPV31 genomes and an inability to maintain viral episomes in long-term assays (40). These observations are consistent with a model in which E2 and/or E8 ^E2C regulates expression of E2 as well as that of E1 through binding site 4. The role of E8 ^E2C may be to control replication of HPV31 by modulating E2's ability to enhance E1-dependent DNA replication as well as by regulating viral gene expression.

Surprisingly, HPV31 genomes that were unable to express E8 ^E2C could not be maintained extrachromosomally at detectable levels in human keratinocytes in long-term assays despite high transient DNA replication levels. One possible explanation would be that the high-level replication of HPV31 E8 ^E2C mutant genomes induces cell death or has a cytostatic effect caused by increased expression of viral proteins. However, subclones of the W12 keratinocyte line stably maintain high-risk HPV16 DNA extrachromosomally at approximately 1,000 copies per cell for at least 15 passages (17). In addition, BPV1-transformed cells with high genome copy numbers do not undergo apoptosis or growth arrest (22, 23, 28, 36). Taken together, these data do not support the idea that high levels of papillomavirus replication are detrimental for cells. It is possible that E8 ^E2C plays an important role in the differentiation-dependent life cycle. A differentiation-dependent loss of E8 ^E2C protein or activity could increase viral copy numbers by 30- to 40-fold, leading to DNA amplification. However, this decrease would not be the result of a down regulation of the spliced 1296 ^3295 transcript, since we were able to detect significant amounts of transcript in cells induced to differentiate in the raft culture system.

In contrast to HPV31, BPV1 E2C or E8-E2 mutant genomes are stably maintained as extrachromosomal elements, suggesting that E2 repressors are not required for the maintenance of BPV1 (22, 36). Furthermore, Piirsoo and coworkers have demonstrated that the stable extrachromosomal maintenance of BPV1 origin plasmids requires only expression of the BPV1 E1 and E2 proteins (33). This discrepancy between BPV1 and HPV31 mutant genomes may be due to the cells used for the analysis of mutant genomes. Experiments with BPV1 have mainly been performed with mouse C127 cells or hamster CHO cells, which are both immortal cell lines, while our studies were performed with normal human keratinocytes, the natural target cells for HPV infection. Additionally, fundamental differences between papillomavirus species may exist with respect to the extrachromosomal maintenance of viral DNA. In line with this, stable maintenance of BPV1 origin plasmids in E1-E2-expressing CHO cells required at least seven E2 binding sites to be present on the plasmid (33), but only four highly conserved E2 binding sites are present among genital HPVs. A recent report demonstrated that the viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins are required for stable but not for transient DNA replication of HPV31 in normal human keratinocytes (42). This observation provides further evidence that the requirements for long-term extrachromosomal maintenance of high-risk HPV31 in normal human keratinocytes may be different from those for BPV1 in immortalized cells. It is also possible that E8 ^E2C deregulates the expression of a cellular gene(s) that is required for extrachromosomal maintenance of HPV31 in normal human keratinocytes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Colbert-Merchant and B. Schopp for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to F.S. (Stu 218/2-1) and by a grant from the NCI to L.A.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barsoum J, Prakash S, Han P, Androphy E J. Mechanism of action of the papillomavirus E2 repressor: repression in the absence of DNA binding. J Virol. 1992;66:3941–3945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3941-3945.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedell M A, Hudson J B, Golub T R, Turyk M E, Hosken M, Wilbanks G D, Laimins L A. Amplification of human papillomavirus genomes in vitro is dependent on epithelial differentiation. J Virol. 1991;65:2254–2260. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2254-2260.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvard V, Storey A, Pim D, Banks L. Characterization of the human papillomavirus E2 protein: evidence of trans-activation and trans-repression in cervical keratinocytes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5451–5459. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang C M, Broker T R, Chow L T. An E1M̂E2C fusion protein encoded by human papillomavirus type 11 is a sequence-specific transcription repressor. J Virol. 1991;65:3317–3329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3317-3329.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang C M, Dong G, Broker T R, Chow L T. Control of human papillomavirus type 11 origin of replication by the E2 family of transcription regulatory proteins. J Virol. 1992;66:5224–5231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5224-5231.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin M T, Hirochika R, Hirochika H, Broker T R, Chow L T. Regulation of human papillomavirus type 11 enhancer and E6 promoter by activating and repressing proteins from the E2 open reading frame: functional and biochemical studies. J Virol. 1988;62:2994–3002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2994-3002.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choe J P, Vaillancourt P, Stenlund A, Botchan M. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 encodes two forms of a transcriptional repressor: structural and functional analysis of new viral cDNAs. J Virol. 1989;63:1743–1755. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1743-1755.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doorbar J, Parton A, Hartley K, Banks L, Crook T, Stanley M, Crawford L. Detection of novel splicing patterns in a HPV16-containing keratinocyte cell line. Virology. 1990;178:254–262. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90401-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frattini M G, Laimins L A. The role of the E1 and E2 proteins in the replication of human papillomavirus type 31b. Virology. 1994;204:799–804. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frattini M G, Lim H B, Doorbar J, Laimins L A. Induction of human papillomavirus type 18 late gene expression and genomic amplification in organotypic cultures from transfected DNA templates. J Virol. 1997;71:7068–7072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7068-7072.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frattini M G, Lim H B, Laimins L A. In vitro synthesis of oncogenic human papillomaviruses requires episomal genomes for differentiation-dependent late expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3062–3067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki R K. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7351–7367. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubbert N L, Schiller J T, Lowy D R, Androphy E J. Bovine papilloma virus-transformed cells contain multiple E2 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5864–5868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubert W G, Kanaya T, Laimins L A. DNA replication of human papillomavirus type 31 is modulated by elements of the upstream regulatory region that lie 5′ of the minimal origin. J Virol. 1999;73:1835–1845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1835-1845.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubert W G, Lambert P F. The 23-kilodalton E1 phosphoprotein of bovine papillomavirus type 1 is nonessential for stable plasmid replication in murine C127 cells. J Virol. 1993;67:2932–2937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2932-2937.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hummel M, Hudson J B, Laimins L A. Differentiation-induced and constitutive transcription of human papillomavirus type 31b in cell lines containing viral episomes. J Virol. 1992;66:6070–6080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6070-6080.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeon S, Allen-Hoffmann B-L, Lambert P F. Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 into the human genome correlates with a selective growth advantage of cells. J Virol. 1995;69:2989–2997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2989-2997.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlen S, Beard P. Identification and characterization of novel promoters in the genome of human papillomavirus type 18. J Virol. 1993;67:4296–4306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4296-4306.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laimins L A. Human papillomaviruses target differentiating epithelium for virion production and malignant conversion. Semin Virol. 1996;7:305–313. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert P F, Spalholz B A, Howley P M. A transcriptional repressor encoded by BPV-1 shares a common carboxy-terminal domain with the E2 transactivator. Cell. 1987;50:69–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert P F, Hubbert N L, Howley P M, Schiller J T. Genetic assignment of multiple E2 gene products in bovine papillomavirus-transformed cells. J Virol. 1989;63:3151–3154. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3151-3154.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert P F, Monk B C, Howley P M. Phenotypic analysis of bovine papillomavirus type 1 E2 repressor mutants. J Virol. 1990;64:950–956. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.950-956.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehman C W, King D S, Botchan M R. A papillomavirus E2 phosphorylation mutant exhibits normal transient replication and transcription but is defective in transformation and plasmid retention. J Virol. 1997;71:3652–3665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3652-3665.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim D A, Gossen M, Lehman C W, Botchan M R. Competition for DNA binding sites between the short and long forms of E2 dimers underlies repression in bovine papillomavirus type 1 DNA replication control. J Virol. 1998;72:1931–1940. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1931-1940.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J S, Kuo S-R, Broker T R, Chow L T. The functions of human papillomavirus type 11 E1, E2, and E2C proteins in cell-free DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27283–27291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McBride A A, Romanczuk H, Howley P M. The papillomavirus E2 regulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18411–18414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McBride A A, Byrne J C, Howley P M. E2 polypeptides encoded by bovine papillomavirus type 1 form dimers through the common carboxyl-terminal domain: transactivation is mediated by the conserved amino-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:510–514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McBride A A, Howley P M. Bovine papillomavirus with a mutation in the E2 serine 301 phosphorylation site replicates at a high copy number. J Virol. 1991;65:6528–6534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6528-6534.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers C, Frattini M G, Hudson J B, Laimins L A. Biosynthesis of human papillomavirus from a continuous cell line upon epithelial differentiation. Science. 1992;257:971–973. doi: 10.1126/science.1323879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyers C, Mayer T J, Ozbun M A. Synthesis of infectious human papillomavirus type 18 in differentiating epithelium transfected with viral DNA. J Virol. 1997;71:7381–7386. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7381-7386.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozbun M A, Meyers C. Human papillomavirus type 31b E1 and E2 transcript expression correlates with vegetative viral genome amplification. Virology. 1998;248:218–230. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozbun M A, Meyers C. Temporal usage of multiple promoters during the life cycle of human papillomavirus type 31b. J Virol. 1998;72:2715–2722. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2715-2722.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piirsoo M, Ustav E, Mandel T, Stenlund A, Ustav M. Cis and trans requirements for stable episomal maintenance of the BPV-1 replicator. EMBO J. 1996;15:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Remm M, Remm A, Ustav M. Human papillomavirus type 18 E1 protein is translated from polycistronic mRNA by a discontinuous scanning mechanism. J Virol. 1999;73:3062–3070. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3062-3070.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rheinwald J G, Beckett M A. Tumorigenic keratinocyte lines requiring anchorage and fibroblast support cultures from human squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1981;41:1657–1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riese D J, II, Settleman J, Neary K, DiMaio D. Bovine papillomavirus E2 repressor mutant displays a high-copy-number phenotype and enhanced transforming activity. J Virol. 1990;64:944–949. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.944-949.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotenberg M O, Chow L T, Broker T R. Characterization of rare human papillomavirus type 11 mRNAs coding for regulatory and structural proteins, using the polymerase chain reaction. Virology. 1989;172:489–497. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snijders P J, van den Brule A J C, Schrijnemakers H F, Raaphorst P M, Meijer C J, Walboomers J M. Human papillomavirus type 33 in a tonsillar carcinoma generates its putative E7 mRNA via two E6* transcript species which are terminated at different early region poly(A) sites. J Virol. 1992;66:3172–3178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3172-3178.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stenlund A. Papillomavirus DNA replication. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 679–698. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stubenrauch F, Lim H B, Laimins L A. Differential requirements for conserved E2 binding sites in the life cycle of oncogenic human papillomavirus type 31. J Virol. 1998;72:1071–1077. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1071-1077.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stubenrauch F, Colbert A M, Laimins L A. Transactivation by the E2 protein of oncogenic human papillomavirus type 31 is not essential for early and late viral functions. J Virol. 1998;72:8115–8123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8115-8123.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas J T, Hubert W G, Ruesch M N, Laimins L A. Human papillomavirus type 31 oncoproteins E6 and E7 are required for the maintenance of episomes during the viral life cycle in normal human keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8449–8454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorner L, Bucay N, Choe J, Botchan M. The product of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 modulator gene (M) is a phosphoprotein. J Virol. 1988;62:2474–2482. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.7.2474-2482.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ustav M, Stenlund A. Transient replication of BPV-1 requires two viral polypeptides encoded by the E1 and E2 open reading frames. EMBO J. 1991;10:449–457. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.zur Hausen H. Molecular pathogenesis of cancer of the cervix and its causation by specific human papillomavirus types. In: zur Hausen H, editor. Human pathogenic papillomaviruses. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1994. pp. 131–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]