Abstract

Introduction:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) negatively affects musculoskeletal health, leading to reduced mobility and quality of life. In healthy populations, carnitine supplementation and aerobic exercise have been reported to improve musculoskeletal health. However, there are inconclusive results regarding their effectiveness and safety in CKD. We hypothesized that carnitine supplementation and individualized treadmill exercise would improve musculoskeletal health in CKD.

Methods:

We used a spontaneously progressive CKD rat model (Cy/+ rat) (n=11–12/gr): 1) Cy/+ (CKD-Ctrl), 2) CKD-carnitine (CKD-Carn), and 3) CKD-treadmill (CKD-TM). Carnitine (250mg/kg) was injected daily for 10-weeks. Rats in the treadmill group ran 4 days/week on a 5° incline for 10-weeks progressing from 30 min/day for week one to 40 min/day for week two to 50 min/day for the remaining eight weeks. At 32 weeks of age, we assessed overall cardiopulmonary fitness, muscle function, bone histology and architecture, and kidney function. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests.

Results:

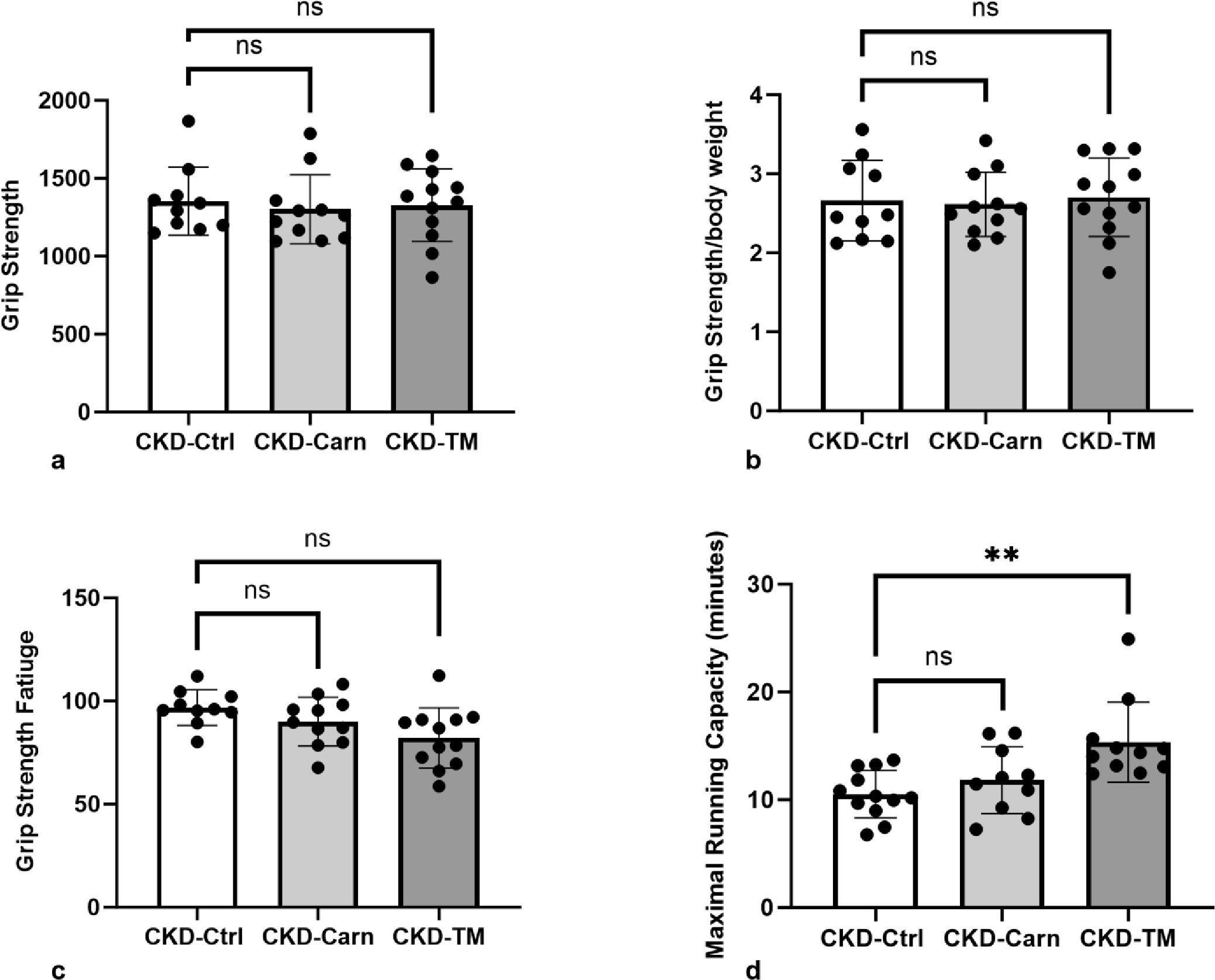

Moderate to severe CKD was confirmed by biochemistries for blood urea nitrogen (mean 43±5 mg/dl CKD-Ctrl), phosphorus (mean 8±1 mg/dl CKD-Ctrl), parathyroid hormone (PTH; mean 625±185 pg/ml CKD-Ctrl), and serum creatinine (mean 1.1±0.2 mg/ml CKD-Ctrl). Carnitine worsened phosphorous (mean 11±3 mg/dl CKD-Carn; p<0.0001), PTH (mean 1738±1233 pg/ml CKD-Carn; p<0.0001), creatinine (mean 1±0.3 mg/dl CKD-Carn; p<0.0001), cortical bone thickness (mean 0.5±0.1 mm CKD-Ctrl, 0.4±0.1 mm CKD-Carn; p<0.05). Treadmill running significantly improve maximal aerobic capacity when compared to CKD-Ctrl (mean 14±2 min CKD-TM, 10±2 min CKD-Ctrl; p<0.01).

Conclusion:

Carnitine supplementation worsened CKD progression, mineral metabolism biochemistries and cortical porosity, and did not have an impact on physical function. Individualized treadmill running improved maximal aerobic capacity but did not have an impact on CKD progression or bone properties. Future studies should seek to better understand carnitine doses in conditions of compromised renal function to prevent toxicity which may result from elevated carnitine levels and to optimize exercise prescriptions for musculoskeletal health.

Keywords: Chronic Kidney Disease, Skeletal Muscle, Bone, Strength, Physical Function

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common condition that affects approximately 35.5 million people in the United States [1]. The progression of kidney disease leads to biochemical, vascular, and bone abnormalities known as CKD-mineral bone disorder (MBD) and skeletal muscle deterioration known as sarcopenia [2–4]. These abnormalities are confounded by inactivity of patients with CKD compared to age-matched healthy individuals, increasing the trajectory of early mortality and declining physical function [5]. Physical function measures of walking speed and grip strength are significantly reduced in individuals with CKD [6]. These deficits have been associated with poor quality of life in CKD and the geriatric populations [7, 8]. In healthy Americans, studies support improved physical function and quality of life following aerobic exercise or carnitine supplementation [9–11]. Similar to clinical outcomes we have demonstrated bone and muscle changes with biochemical abnormalities in an animal model of slowly progressive CKD. These musculoskeletal changes coincided with higher oxidative stress, abnormalities in muscle mitochondria, and metabolism (via metabolomics) [12, 13]. Physical activity interventions in our rodent model have shown variable outcomes with an adverse response of increased muscle catabolism from standard progressive treadmill training [14], but positive responses of voluntary wheel running that improved CKD progression, bone, and muscle [15]. The progression of CKD coincides with inconsistent responses to exercise, and a carnitine deficiency via reduced renal synthesis which ultimately impairs musculoskeletal health [16, 17]. Carnitine supplementation has not been studied in our rat model, however the attenuation of carnitine deficiency within our animals may lead to improved musculoskeletal health. These results suggest that CKD may alter metabolic pathways and mitochondrial health that impair physical function, which indicates the need for careful consideration when prescribing exercise and supplements such as carnitine.

Carnitine is important for mitochondria fatty acid oxidation and may improve musculoskeletal performance and health with supplementation. Carnitine is endogenously produced in the liver, kidney, and brain, it is also a product of amino acids lysine and methionine, while exogenous sources are dietary (i.e., animal meat) [18, 19]. In those with advanced CKD, carnitine deficiency is prominent [17]. Deficiency arises from decreased appetite, energy levels, protein intake, and decreased biosynthesis in the kidney without liver compensation. Additionally, inflammation has been linked to the disruption of carnitine absorption in the intestine [16]. These abnormalities can cumulatively impair fatty acid transportation into the mitochondria for β-oxidation and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production [20]. Therefore, carnitine supplementation may be beneficial to overcome the metabolic deficits we previously found [13]. In healthy active adults, carnitine supplementation improved running speed, peak power, and reduced blood lactate levels during exercise testing [9, 21]. In the osteoporotic population, carnitine supplementation improved bone turnover markers (i.e., osteocalcin and osteopontin) in preclinical studies, which was further supported in clinical studies with increased bone mineral density (BMD) [22–24]. Clinically, the 2000 National Kidney Foundation (NFK)-K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines supported carnitine supplementation for the treatment of anemia during dialysis treatment [25], however a lack of Medicare coverage precluded recommendation adherence. However, the 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KIDIGO) group advised against carnitine supplementation in CKD due to the lack of evidence supporting its benefits and safety [26]. The discrepancies between the recommendations highlight the need for additional studies to demonstrate the efficacy of carnitine supplementation in CKD.

Aerobic exercise has also demonstrated many benefits in healthy and diseased populations. However, studies in CKD are inconsistent. In human studies, exercise prescriptions are highly individualized and adaptive throughout the lifespan or adjusted with chronic disease progression. Clinical meta-analyses have concluded that aerobic exercise is beneficial for maximal oxygen consumption, muscle strength, exercise duration, and quality of life for individuals with chronic kidney disease [27, 28]. However, aerobic exercise has been shown to have minimal to no effect for diastolic blood pressure, systolic blood pressure, left ventricular mass index, walking capacity, and muscle area [27]. Animal studies have demonstrated conflicting results on the presence of maladaptive oxidative stress levels and skeletal muscle catabolism/anabolism following aerobic exercise [29–31, 14, 32]. Given the inconsistencies in CKD-related exercise research we hypothesize that the dose of exercise needs further consideration, as most rodent studies use a single one-size-fits-all exercise regimen, compared to the individualized approach to exercise used with humans.

Given the severity of musculoskeletal disease, poor physical function of patients and animals alike with CKD, and our data on impaired fatty acid oxidation in muscle mitochondria we hypothesized that 1) carnitine supplementation would have a beneficial effect on metabolic adaptation evident by improved sarcopenia and/or CKD-MBD and 2) that an individualized structured treadmill program in CKD rats would have a beneficial effect on metabolic adaptation evident by improved sarcopenia and CKD-MBD. Our study compared the two treatments versus untreated CKD rats in a progressive model of CKD. We assessed overall cardiopulmonary fitness, muscle function, bone histology and architecture, and kidney function.

Methods

Animal Model:

Male Cy/+IU rats (CKD hereafter) aged 30–40 weeks demonstrate a slowly progressive cystic kidney disease that is due to a mutation in Anks6, a gene that codes for the protein SamCystin located at the base of cilia. Although its specific function is not fully elucidated, Anks6 binds with Anks3 and Bicc1 and thus may alter the nephronopthisis complex [33, 34], but the cilia are not directly affected. In this rat model, CKD-MBD develops spontaneously (on a normal phosphate diet) develops the tripartite manifestation of CKD-MBD (i.e. biochemical abnormalities, extraskeletal calcification, and abnormal bone) [2]. These animals also demonstrate impaired skeletal muscle strength, though cross-sectional area of the hindlimb muscles is not impacted by disease [35]. Female rats with or without an ovariectomy do not develop end-stage kidney disease [36, 37], thus only male animals were used. Given the established disease model we did not include normal littermates (NL; Cy+/+); only CKD rats were used [12, 32, 13]. Animals were bred in-house and weaned at 3 weeks of age for placement in individual housing at 10 weeks of age. Rats had 24 hour a day access to food (Envigo Teklad 2018SX autoclaved diet) and tap water [38]. All animals were housed in standard cages with a consistent light-dark cycle (6AM-6PM). Phenotyping via blood urea nitrogen (BUN) measurements took place at 10 weeks of age [38]. At 21 weeks of age, CKD animals were switched to a diet of casein-based protein (18%, unautoclaved), phosphorous (0.7%; 0.6% phosphate additives), and calcium (0.7%) (Envigo Teklad TD.04539), which has demonstrated a consistent and reproducible CKD-MBD phenotype [2]. Animals were assigned a study identification and randomly (simple randomization) divided into three groups (n=11–12/group): (1) CKD-Ctrl, and (2) CKD-TM (treadmill) (3) CKD-Carn (carnitine) and treated for 10 weeks. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane at 32 weeks of age to undergo a cardiac puncture for blood collection in Lithium Heparin coated blood collection tubes (BD 367884). Rats were then euthanized via exsanguination and bilateral pneumothorax for collection of the kidney, heart, aorta, tibia, femur, extensor digitorum longus (EDL), and soleus muscles. Collected tissues were weighed and then prepared for storage at −80°C. The right EDL and soleus muscles were prepared for histological analysis by cutting the middle third of the tissue then placing it on cork with optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) which was then frozen in liquid nitrogen chilled 2-methylybutane for 60 seconds. The kidney’s, heart, aorta, right EDL, and right soleus were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which adheres to the Guide for the Ethical Treatment of Animals to minimize pain and suffering.

Carnitine Supplementation:

Animals underwent daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of carnitine (CARNITOR® (levocarnitine), Leadiant Biosciences) from 22 to 32 weeks of age. Carnitine dosing was determined in a pilot study comparing 250mg/kg to 500mg/kg of carnitine 5 days per week for 5 weeks. We first demonstrated a 34% reduction in plasma carnitine (p<0.05; normal littermates: 33.3±1.7μM compared to CKD: 22.1±2μM). The 500mg/kg dose resulted in a two-fold increase in plasma carnitine levels compared to untreated normal littermates (normal littermates: 33.3±1.7μM compared to CKD 500mg/kg: 60.6±23μM). The 250mg/kg dose resulted in equivocal levels comparable to normal littermates (normal littermates: 33.3±1.7μM compared to CKD 250mg/kg: 35.9±3.3μM). The normalization of plasma carnitine with the 250 mg/kg dose supported the chosen dose in this current study. Carnitine treated CKD animals in this study were intraperitoneally injected with 250mg/kg of carnitine for 10 weeks (shown in Fig. S1).

Individualized Treadmill Training:

One week prior to training, animals were acclimated to the treadmills for 5 minutes, 4 days per week with progressive increases in both grade and speed to prepare for maximal running capacity testing and training. The limited duration was intended to acclimate the animal to the treadmill without resultant physiological adaptations. For the study, the individualized protocol was 4 days per week (i.e., Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday) at a 5-degree incline for 10 weeks. To facilitate gradual adaptation, animals ran for 30 minutes the first week, 40 minutes the second week, and 50 minutes for the remainder of the 10 weeks (shown in Fig. S1). The speed started at 12 m/min the first week, though it could be decreased if the animal demonstrated difficulty maintaining pace (see protocol for individualizing the treadmill therapy which is shown in Table S1) that resulted in speed increases, decreases or no change depending on the animal’s behavior and the protocol. These predetermined criteria were analogous to humans who base their training on perceived exertion. Exercise dosage was reported across three-time blocks: 1) the first 3 weeks of training (22–24 weeks of age; kidney function ~ 40–50% normal, CKD stage 3b), 2) the middle 4 weeks of training (25–28 weeks of age; function ~ 20–30% normal, stage 4), and 3) the last 3 weeks of training (29–31 weeks of age; function ~ 10–20% normal, stage 5).

Physical Function and Strength Measures:

Physical function was assessed in vivo by maximal running capacity and grip strength. Maximal running capacity was assessed on a single lane treadmill specific to rats after 4 days of acclimation at baseline and end point (Panlab Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). We have previously determined that the acclimation period improves the rats comfort level on the treadmill without causing a training effect. Following a 3-min warm up at 10 cm/s with a 10° grade, the treadmill was fixed at a 25° grade with an increase in speed every 3 minutes until exhaustion [39]. The warm-up period was subtracted from the final time to obtain maximal running capacity which is presented as time-to-fatigue (minutes). Voluntary grip strength was assessed by lowering rats onto the grid of a testing apparatus (GT3, Harvard Instruments). Once all four paws were in contact with the grid, the tail was gently and steadily pulled horizontally away from the grid until voluntary grip release. Each animal performed 3 repetitions with approximately 5-minute rest intervals [40]. Grip strength is presented as maximal force normalized to body weight [15].

Bone Microarchitecture and Cortical Porosity:

Microcomputed tomography (μCT; Skyscan 1172) included raw scans that were reconstructed, processed and analyzed with Bruker software (NRecon, DataViewer, CTAn, Billerica, MA, USA) using at a 12-μm resolution proximal tibias following euthanasia and bone dissection. Trabecular parameters were obtained from a location approximately 0.5 mm from the distal end of the growth plate and included a 1-mm area of interest that excluded cortical bone. Standard procedures were used to measure trabecular bone volume (BV/TV, %), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), and trabecular number (Tb.N) [41]. Cortical parameters were measured from 5 contiguous slices 4-mm below the last slice of trabecular bone. Cortical porosity was assessed from hand drawn regions encapsulating bone volume including the void spaces (pores) between the periosteal and endosteal surfaces. Cortical porosity was defined as the inverse of bone volume or the percent of void space within the cortical bone region [42].

Dynamic Histomorphometry:

Calcein (30mg/kg) injections were given to all animals 14 and 4 days before euthanasia for dynamic bone histomorphometry. Proximal tibias were fixed in neutral buffered formalin at the time of tissue collection then serially dehydrated and embedded in methyl methacrylate (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Frontal sections were serially cut 4-μm-thick to be analyzed unstained for fluorochrome calcein labels. A trabecular region of interest excluding primary spongiosa and endocortical surfaces was measured at 20X magnification. Total bone surface (BS), single-labeled surface (sLS), double-labeled surface (dLS), and inter-label distances were measured. Mineralized surface to bone surface, mineral apposition rate, and bone formation rate were calculated using previously reported methods [43]. A second 4 μm-thick section was stained with tartrate resistant alkaline phosphatase (TRAP) for assessment of osteoclasts. Sections were analyzed as osteoclast-covered trabecular surfaces normalized to total trabecular bone surface (Oc.S/BS, %) within the same region of interest as described above. All histomorphometric analyses were completed by the same individual and performed using BIOQUANT (BIOQUANT Image Analysis, Nashville, TN, USA). All nomenclature for histomorphometry follows standard usage [44].

Left Ventricular Mass Index and Heart Calcification:

Left ventricular mass index (LVMI) was calculated as the ratio of heart weight to body weight [45]. Aortic arch and heart calcification was assessed by incubating segments of aortic arches or atrium in 0.6 N HCl for 48 h (4μL/mg of aortic arch tissue and 1.25μ/mg of heart). The supernatant was analyzed for calcium using the o-cresolphthalein complex 1 method (Calcium kit; Pointe Scientific) and then normalized by tissue dry weight [46].

Blood Biochemistry:

Collected blood was centrifuged at 1200g for 10 minutes to obtain plasma for analysis by colorimetric assays for BUN (DIUR-100), creatinine (BioAssay Systems), calcium, and phosphorous (Pointe Scientific). ELISA kits (Quidel corporation) were used to measure intact PTH and FGF23. A DNA damage ELISA kit (Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY) was used to measure the plasma oxidative stress marker, 8-hydroxy-2’ -deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG).

Statistics:

Experimental units were represented by individual rats from all groups (CKD-Ctrl, CKD-TM, CKD-Carn). Data underwent assessment and removal of outliers by the ROUT method then normality and variance were assessed for all outcomes and log transformed as appropriate prior to analyses [47]. All outcomes were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons when appropriate. Results are reported as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted. All statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.0 (San Diego, CA) and statistical significance was set at α < 0.05.

Results

CKD progression was worsened following carnitine supplementation but was not impacted by exercise.

Carnitine treatment worsened serum creatinine (but not BUN) (shown in Fig. 1a–b). Carnitine supplementation also resulted in higher concentrations of plasma phosphorous, PTH, intact FGF23, and c-terminal FGF23 compared to CKD-Ctrl; individualized treadmill running had no effect on these parameters (shown in Fig. 1c–f). Calcium was not different between groups (CKD-Ctrl mean 7.9±2.9 mg/dl; CKD-Carn mean 8±2.4 mg/dl; CKD-TM mean 9.4±1.5 mg/dl; p=0.14). Plasma carnitine and serum 8-OHdG (i.e., oxidative stress marker) were significantly higher in the CKD-Carn group when compared to CKD-Ctrl, but were not impacted by CKD+TM (shown in Fig. 1 g–h). Body weight was not significantly different among the groups (CKD-Ctrl mean 518±53 g; CKD-Carn mean 498±27 g; CKD-TM mean 489±27 g; p=0.31).

Fig. 1.

Carnitine supplementation, but not treadmill running, significantly worsened CKD biochemistries. At 32 weeks of age, plasma and serum were assessed for a Creatinine, b BUN, c Phosphorous, d PTH, e intact FGF23, f c-terminal FGF23, g Carnitine, h 8-OHdG. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001.

Individualized Treadmill training, but not carnitine supplementation, improved physical function.

We first compared the average running distance and speed over the 10-week training period. Both distance and speed were consistently increased in blocks two and three when compared to block one, while parameters were similar across blocks two and three. The absence of change from period two to three may have been due to progression of CKD (shown in Table 1). Physical function assessed by grip strength included three different components, maximal strength (shown in Fig. 2a), grip strength normalized by body weight (shown in Fig. 2b), and grip fatigue (shown in Fig. 2c), without differences among the three groups. Maximal running capacity was not impacted by carnitine, but significantly higher following individualized treadmill training (shown in Fig. 2d). Neither carnitine nor individualized treadmill running impacted cardiovascular parameters of aortic arch calcification (CKD-Ctrl mean 3.9±1.0; CKD-Carn mean 3.8±0.81; CKD-TM mean 3.5±0.57; p=0.42), heart calcification (CKD-Ctrl mean 0.74±0.15; CKD-Carn mean 0.73±0.08; CKD-TM mean 0.69±0.09; p=0.58) or LVMI (CKD-Ctrl mean 0.31±0.03; CKD-Carn mean 0.32±0.02; CKD-TM mean 0.32±0.03; p=0.30). Similarly, neither intervention impacted muscle weight for soleus (CKD-Ctrl mean 189±32; CKD-Carn mean 183±23; CKD-TM mean 186±13; p=0.87) or EDL CKD-Ctrl (mean 235±31;CKD-Carn mean 220±13; CKD-TM mean 221±11; p=0.13).

Table 1.

Individualized Treadmill Training Average Speeds and Distances

| Block 1: CKD stage 3b | Block 2: CKD stage 4 | Block 3: CKD stage 5 | Overall P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Average Speed (m/min) | 12.24±0.42 | 15.62±2.8** | 14.86±2.76* | <0.01 |

| Average Distance (m) | 443±33 | 679±130**** | 660±115**** | <0.0001 |

Block 1: 22–24 weeks of age; kidney function ~ 40–50% normal, ckd stage 3b; Block 2: 25–28 weeks of age; function ~ 20–30% normal, stage 4; Block 3: 29–31 weeks of age; function ~ 10–20% normal, stage 5. Significant comparisons were found between blocks 1–2 and 1–3.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.0001.

Fig. 2.

Strength was not impacted by carnitine supplementation or exercise; however, maximal running capacity was significantly increased following individualized treadmill training. a Grip Strength, b Grip Strength/Body Weight, c Grip Strength Fatigue, and d Maximal Running Capacity. ** p<0.01.

Cortical thickness was lower following carnitine supplementation while individualized treadmill running did not impact bone structural parameters.

Carnitine supplementation led to significantly lower cortical thickness but did not affect cortical porosity or cortical bone area in CKD-Carn animals when compared to CKD-Ctrl animals. (shown in Fig. 3a–c). Neither carnitine supplementation nor individualized treadmill training significantly impacted trabecular bone parameters; BV/TV, Tb.Sp, Tb.N, compared to CKD-Ctrl animals (shown in Fig. 3d–g). Treadmill training, but not carnitine supplementation significantly improved trabecular thickness when compared to CKD-Ctrl animals (Fig. 3g). Despite the higher PTH with carnitine, dynamic histomorphometry showed no difference in response to either carnitine supplementation or individualized treadmill training: bone formation rate/bone surface (BFR/BS; shown in Fig. 3h), osteoclast surface/bone surface (OcS/BS; shown in Fig. 3i), mineral apposition rate (MAR; CKD-Ctrl mean 3±0.68 μm/d; CKD-TM mean 3.4±0.95 μm/d; CKD-Carn mean 3.7±1 μm/d; p=0.29), and mineralized surface/bone surface (MS/BS; CKD-Ctrl mean 28±7%; CKD-TM mean 29±4%; CKD-Carn mean 28±4%; p=0.83).

Fig. 3.

Bone parameters were worsened by carnitine supplementation but were not impacted by treadmill running. At 32 weeks of age bones were assessed for a Cortical Thickness, b Cortical Porosity, c Cortical Bone Area, d BV/TV, e Tb.Sp, f Tb.N, g Tb.Th, h BFR/BS, i OcS/BS.*p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Discussion

The deterioration of musculoskeletal health in individuals with CKD is evidenced by muscle weakness, fatigue, and increased risk of fracture [48–50]. In alignment with patient impairments, the Cy/+ rat model has demonstrated muscle and bone impairments of reduced skeletal muscle strength, maximal running capacity, cortical bone loss and reductions in mechanical properties [35, 15]. The traditional exercise interventions to treat muscle and/or sarcopenia lack sufficient evidence for efficacy. We hypothesized this was due to impaired mitochondrial function due to carnitine deficiency (and resulting fatty acid metabolism) or due to increased oxidative stress with a one-size-fits-all prescription for exercise in the setting of a progressive chronic disease. We, therefore, compared the administration of carnitine supplementation and individualized treadmill training to sedentary CKD controls in a CKD rat model to improve CKD-MBD and sarcopenia. Unexpectedly, carnitine supplementation worsened CKD progression markers as assessed by creatinine and measures of CKD-MBD (i.e., PTH, FGF-23, 8-OHdG) and cortical bone structure. Conversely, only individualized treadmill training improved maximal running capacity without affecting disease progression or bone properties.

Carnitine is a popular nutraceutical with an estimated global value of USD ~203 million, within a growing nutraceutical industry estimated at USD 20.5 billion [51, 52]. Nutraceuticals are commonly used by Americans, with ~60% reporting having taken a supplement, 39% having taken a sports-specific supplement, and 77% reporting they feel the industry is trustworthy [53]. Beyond supplementation, carnitine is found in red meat, poultry, fish, and dairy foods [54, 19, 55] as well as, energy drinks. Clinical use of carnitine for those with CKD has fluctuated over the years in response to the original K/DOQI recommendation supporting use in patients with anemia [25], to the more recent KIDIGO anemia guidelines which advise against carnitine supplementation in CKD for anemia or other indications due to the lack of evidence supporting its benefits and safety [26]. The divergent carnitine recommendations supported the exploration in the current study.

In the current study, 10 weeks of daily, I.P. injections of 250 mg/kg of carnitine worsened the progression of CKD, exacerbated CKD-MBD biochemistries and resulted in lower cortical bone thickness. The chosen dose of 250 mg/kg was derived from our pilot study, that was five weeks in duration, from 27 weeks of age (~20–30% of normal renal function) to 32 weeks of age (~10–20% of normal renal function). Despite the normalization of carnitine in our 5-week pilot study, the identified dose administered for 10 weeks resulted in supraphysiologic carnitine levels. This unexpected accumulation of carnitine after 10 weeks of injections compared to 5 weeks, suggests that we cannot rule out that carnitine supplementation led to the adverse effects on CKD progression and may serve as a limitation for the current study. The chosen moderate dose is in line with other preclinical studies that injected 100–500 mg/kg of carnitine with positive outcomes upon oxidative stress, biochemistries, and kidney health [56–58]. In a 5/6th nephrectomy model, 250mg/kg of I.P. carnitine for eight weeks improved creatinine, BUN, and glomerular damage [59]. The opposing outcomes may stem from the same dose used with differences in kidney disease etiology, and that our model has more severe progression. The 5/6th nephrectomy animals had less severe kidney disease with creatinine at end points of = ~0.75 mg/dl, while our current study with Cy/+ rats, demonstrated greater disease progression with creatinine = 1.14±0.21 mg/dl. Given that carnitine is excreted by the kidneys, these subtle differences in blood accumulation with differences in the level of kidney dysfunction point toward caution of the safety of carnitine. The negative outcomes that coincided with elevated carnitine levels observed in this current study support the need for well-controlled studies that consider disease progression and supplement regimen. Considerations should be made in the context of advanced CKD with/without dialysis, given the difference in carnitine clearance with dialysis [60].

In the current study, individualized treadmill training did not impact CKD or CKD-MBD biochemistries, muscle strength, muscle weight, or bone outcomes other than trabecular bone volume. However, it did improve maximal running capacity that cannot be attributed to changes in cardiac mass or calcification, as the exercised CKD animals were not different from CKD-Ctrl animals. Aerobic exercise is widely used to promote health and to prevent declines in physical function in aging and diseased populations [61, 62]. Treadmill training is a popular mode of aerobic exercise that to improves physical function, health, and quality of life when diseases such as diabetes and heart failure are present [63–65]. In the majority of human studies, the ‘dose’ of exercise is individualized to promote adherence and positive outcomes by preventing oxidative stress which can arise from overtraining [66]. Previous animal studies that lack such individualization can even be harmful. We previously demonstrated negative findings using a progressively increasing protocol in all rats: 60 min/day, 5 days/week, starting speed of 8m/min that progressed incrementally to 18 m/min over 10 weeks. Despite appropriate training, CKD rats demonstrated higher muscle catabolism and reduced satellite stem cell quiescence, which we attributed to greater exercise intensity requirements coinciding with progressive renal function deterioration [67]. In support of e a self-paced regimen, with slower speeds/lower intensity, our 10-week voluntary wheel running program in the Cy/+ rat improved biochemistries, physical function, and bone outcomes. Diseased animals from the voluntary wheel running study ran at an average speed of ~17 m/min and average distance of ~555 meters for the last four weeks of training [15]. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that an individualized rodent treadmill training program may improve musculoskeletal health by having strict criteria to reduce the intensity in an individual animal. To our knowledge, this approach is unique, and offers a more translational intervention.

The individualized approach was intended to enable the rat speed reductions, as opposed to progressive increases, in light of worsening of kidney disease towards end-stage renal disease during weeks 30–32 in this model [2]. The individualized treadmill training compared to our previously published wheel running study, resulted in the treadmill animals running at a slower pace (~15 m/min vs ~17 m/min, respectively), but for a longer distance (~660 m vs ~555 m, respectively). Given the speed is relatively similar the primary difference is the single bolus of treadmill as opposed to the intermittent participation in the wheel running animals; this difference may explain differences in bone improvements not identified in this study that were found in the wheel running study [15]. Limitations of the exercise training includes multiple rat handlers (due to intervention of adjusting the intensity and frequency) and the type of exercise. The use of aerobic exercise, without resistance training, may have also contributed to the lack of muscle size and strength outcomes. The improvements in maximal running capacity, without negative implications, suggest that we are moving toward training optimization for this population.

Summary

In summary, 10-weeks of carnitine injections worsened CKD progression and resulted in worsening CKD-MBD and decreased cortical bone structure. In contrast, our unique protocol of individualized treadmill training improved maximal running capacity without further worsening other CKD indicators but did not improve muscle strength. Nonetheless, our unique individualized protocol appears to be required, especially in a model with progressive and somewhat variable CKD progression due to the naturally occurring and severe progressive phenotype of the Cy/+ rat. Indeed, our results suggest that aerobic exercise alone is inefficient to elicit a positive adaptation and that further studies should explore the impact of aerobic exercise dosage and the addition of resistance training. Further, carnitine dosage should be investigated along the continuum of disease progression to optimize dose given the high over-the-counter usage.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure S1. Study timeline CKD+Ctrl, CKD+Carn, and CKD+TM groups. Treadmill program details listed in the CKD+TM section.

Supplemental Table S1. Protocol used to individualize treadmill training.

Acknowledgements

Treadmill protocols were implemented by Peyton Brandt, Duncan D’Amico, Kaytlin Galloway, and Jenna Hedlund.

Funding Sources

KGA is supported by NIH NIDDK K08 DK110429 and R03 DK125665.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of Ethics

All study procedures were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committees, approval number [21128].

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moe SM, Chen NX, Seifert MF, Sinders RM, Duan D, Chen X, et al. A rat model of chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder. Kidney Int. 2009. Jan;75(2):176–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avin KG, Moorthi RN. Bone is Not Alone: the Effects of Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015. Jun;13(3):173–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troutman A, Arroyo E, Lim K, Moorthi R, Avin K. Skeletal Muscle Complications in Chronic Kidney Disease. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2022. September/23;20:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Ng AV, Mulligan K, Carey S, Schoenfeld PY, et al. Physical activity levels in patients on hemodialysis and healthy sedentary controls. Kidney Int. 2000. Jun;57(6):2564–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu MD, Zhang HZ, Zhang Y, Yang SP, Lin M, Zhang YM, et al. Relationship between chronic kidney disease and sarcopenia. Sci Rep. 2021. Oct 15;11(1):20523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanden Wyngaert K, Van Craenenbroeck AH, Eloot S, Calders P, Celie B, Holvoet E, et al. Associations between the measures of physical function, risk of falls and the quality of life in haemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrology. 2020 2020/January/06;21(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad L, Fredrick J, Aruna R. The relationship between physical performance and quality of life and the level of physical activity among the elderly. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orer GE, Guzel NA. The Effects of Acute L-carnitine Supplementation on Endurance Performance of Athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2014;28(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brightwell CR, Markofski MM, Moro T, Fry CS, Porter C, Volpi E, et al. Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise improves skeletal muscle quality in older adults. Translational sports medicine. 2019;2(3):109–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fritzen AM, Andersen SP, Qadri KAN, Thøgersen FD, Krag T, Ørngreen MC, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise training and deconditioning on oxidative capacity and muscle mitochondrial enzyme machinery in young and elderly individuals. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(10):3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avin K, Chen N, Organ J, Zarse C, O’Neill K, Conway R, et al. Skeletal Muscle Regeneration and Oxidative Stress Are Altered in Chronic Kidney Disease. PLOS ONE. 2016. August/03;11:e0159411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avin K, Hughes M, Chen N, Srinivasan S, O’Neill K, Evan A, et al. Skeletal muscle metabolic responses to physical activity are muscle type specific in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Scientific Reports. 2021. May/07;11:9788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organ J, Allen M, Myers-White A, Elkhatib W, O’Neill KD, Chen N, et al. Effects of treadmill running in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports. 2018. September/14;16:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avin KG, Allen MR, Chen NX, Srinivasan S, O’Neill KD, Troutman AD, et al. Voluntary Wheel Running Has Beneficial Effects in a Rat Model of CKD-Mineral Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019. Oct;30(10):1898–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takashima H, Maruyama T, Abe M. Significance of Levocarnitine Treatment in Dialysis Patients. Nutrients. 2021. Apr 7;13(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulinski T, Cirulli M, Virmani MA. The Role of L-Carnitine in Kidney Disease and Related Metabolic Dysfunctions. Kidney and Dialysis. 2023;3(2):178–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira GC, McKenna MC. L-Carnitine and Acetyl-L-carnitine Roles and Neuroprotection in Developing Brain. Neurochem Res. 2017. Jun;42(6):1661–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durazzo A, Lucarini M, Nazhand A, Souto SB, Silva AM, Severino P, et al. The Nutraceutical Value of Carnitine and Its Use in Dietary Supplements. Molecules. 2020. May 1;25(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gnoni A, Longo S, Gnoni GV, Giudetti AM. Carnitine in Human Muscle Bioenergetics: Can Carnitine Supplementation Improve Physical Exercise? Molecules. 2020;25(1):182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koozehchian MS, Daneshfar A, Fallah E, Agha-Alinejad H, Samadi M, Kaviani M, et al. Effects of nine weeks L-Carnitine supplementation on exercise performance, anaerobic power, and exercise-induced oxidative stress in resistance-trained males. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem. 2018. Dec 31;22(4):7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aydin A, Halici Z, Albayrak A, Polat B, Karakus E, Yildirim OS, et al. Treatment with Carnitine Enhances Bone Fracture Healing under Osteoporotic and/or Inflammatory Conditions. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2015;117(3):173–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Wang C. Efficacy of L-carnitine in the treatment of osteoporosis in men. International Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;11(2):148–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed SA, Abd El Reheem MH, Elbahy DA. l-Carnitine ameliorates the osteoporotic changes and protects against simvastatin induced myotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022 2022/August/01/;152:113221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adult guidelines I. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2000 2000/June/01/;35(6, Supplement):s17–s104.10895784 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KIDGO) CKD Work Group. KIDGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guidline for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. 2012;2(4). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training in adults with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014. Sep;64(3):383–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pei G, Tang Y, Tan L, Tan J, Ge L, Qin W. Aerobic exercise in adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD): a meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019. Oct;51(10):1787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moningka NC, Sindler AL, Muller-Delp JM, Baylis C. Twelve weeks of treadmill exercise does not alter age-dependent chronic kidney disease in the Fisher 344 male rat. The Journal of Physiology. 2011;589(24):6129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Souza PS, da Rocha LGC, Tromm CB, Scheffer DL, Victor EG, da Silveira PCL, et al. Therapeutic action of physical exercise on markers of oxidative stress induced by chronic kidney disease. Life Sciences. 2012 2012/August/21/;91(3):132–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida T, Kakizawa S, Totsuka Y, Sugimoto M, Miura S, Kumagai H. Effect of endurance training and branched-chain amino acids on the signaling for muscle protein synthesis in CKD model rats fed a low-protein diet. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2017;313(3):F805–F14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avin K, Allen M, Chen N, Srinivasan S, O’Neill K, Troutman A, et al. Voluntary wheel running has beneficial effects in a rat model of CKD-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2019. September/09;30:ASN.2019040349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoff S, Halbritter J, Epting D, Frank V, Nguyen TM, van Reeuwijk J, et al. ANKS6 is a central component of a nephronophthisis module linking NEK8 to INVS and NPHP3. Nat Genet. 2013. Aug;45(8):951–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakey Z, Bihoreau MT, Piedagnel R, Delestre L, Arnould C, de Villiers A, et al. The SAM domain of ANKS6 has different interacting partners and mutations can induce different cystic phenotypes. Kidney Int. 2015. Aug;88(2):299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Organ J, Srisuwananukorn A, Price P, Joll J, Biro K, Rupert J, et al. Reduced skeletal muscle function is associated with decreased fiber cross-sectional area in the Cy/+ rat model of progressive kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2015. October/05;31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowley BD Jr, Rupp JC, Muessel MJ, Gattone VH 2nd. Gender and the effect of gonadal hormones on the progression of inherited polycystic kidney disease in rats. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997. Feb;29(2):265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vorland CJ, Lachcik PJ, Swallow EA, Metzger CE, Allen MR, Chen NX, et al. Effect of ovariectomy on the progression of chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) in female Cy/+ rats. Sci Rep. 2019. May 28;9(1):7936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moe SM, Chen NX, Newman CL, Organ JM, Kneissel M, Kramer I, et al. Anti-sclerostin antibody treatment in a rat model of progressive renal osteodystrophy. J Bone Miner Res. 2015. Mar;30(3):499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wisloff U, Helgerud J, Kemi OJ, Ellingsen O. Intensity-controlled treadmill running in rats: VO(2 max) and cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001. Mar;280(3):H1301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Argilés JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B, López-Soriano FJ. Cachexia and sarcopenia: mechanisms and potential targets for intervention. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015. Jun;22:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Müller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010. Jul;25(7):1468–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metzger CE, Newman CL, Tippen SP, Golemme NT, Chen NX, Moe SM, et al. Cortical porosity occurs at varying degrees throughout the skeleton in rats with chronic kidney disease. Bone Reports. 2022 2022/December/01/;17:101612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen NX, Srinivasan S, O’Neill K, Nickolas TL, Wallace JM, Allen MR, et al. Effect of Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGE) Lowering Drug ALT-711 on Biochemical, Vascular, and Bone Parameters in a Rat Model of CKD-MBD. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2020;35(3):608–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013. Jan;28(1):2–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozdemir O, Yavuz O, Hatipoğlu F. Effect of routine pathological procedure on morphometric parameters of the heart in rat models. Scientific Research and Essays. 2014. April/30;9:224–28. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen NX, O’Neill K, Chen X, Kiattisunthorn K, Gattone VH, Moe SM. Transglutaminase 2 accelerates vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37(3):191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006. Mar 9;7:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkinson TJ, Gould DW, Nixon DGD, Watson EL, Smith AC. Quality over quantity? Association of skeletal muscle myosteatosis and myofibrosis on physical function in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019. Aug 1;34(8):1344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu CY, Chen LR, Chen KH. Osteoporosis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Diseases: A Systemic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Sep 18;21(18). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gregg LP, Bossola M, Ostrosky-Frid M, Hedayati SS. Fatigue in CKD: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021. Sep;16(9):1445–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.L-carnitine Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Process (Bioprocess, Chemical Synthesis), By Product (Food & Medicines Grade, Feed Grade), By Application, By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2023 – 2030. p. 1–151. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christensen J Most US adults and a third of children use dietary supplements, survey finds. CNN Health: Cable News Network. A Warner Bros. Discovery Company.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dietary Supplement Use Reaches All Time High. In: Muckle C, editor.: Council for Responsible Nutrition; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 54.C.J. R. Carnitine. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Food an Nutrition board. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sayed-Ahmed MM, Eissa MA, Kenawy SA, Mostafa N, Calvani M, Osman A-MM. Progression of Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in a Carnitine-Depleted Rat Model. Chemotherapy. 2004;50(4):162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boonsanit D, Kanchanapangka S, Buranakarl C. L-carnitine ameliorates doxorubicin-induced nephrotic syndrome in rats. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006. Aug;11(4):313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canbolat EP, Sagsoz N, Noyan V, Yucel A, Kısa U. Effects of l-carnitine on oxidative stress parameters in oophorectomized rats. Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 2017;53(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abu Ahmad N, Armaly Z, Berman S, Jabour A, Aga-Mizrachi S, Mosenego-Ornan E, et al. l-Carnitine improves cognitive and renal functions in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Physiology & Behavior. 2016 2016/October/01/;164:182–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Evans AM, Faull R, Fornasini G, Lemanowicz EF, Longo A, Pace S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of L-carnitine in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing long-term hemodialysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000. Sep;68(3):238–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson E, Durstine JL. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Med Health Sci. 2019. Dec;1(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grevendonk L, Connell NJ, McCrum C, Fealy CE, Bilet L, Bruls YMH, et al. Impact of aging and exercise on skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity, energy metabolism, and physical function. Nature Communications. 2021 2021/August/06;12(1):4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collins E, Langbein WE, Dilan-Koetje J, Bammert C, Hanson K, Reda D, et al. Effects of exercise training on aerobic capacity and quality of life in individuals with heart failure. Heart & Lung. 2004 2004/May/01/;33(3):154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor JD, Fletcher JP, Mathis RA, Cade WT. Effects of Moderate- Versus High-Intensity Exercise Training on Physical Fitness and Physical Function in People With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Physical Therapy. 2014;94(12):1720–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maharaj SS, Nuhu JM. The effect of rebound exercise and treadmill walking on the quality of life for patients with non-insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries. 2015 2015/September/01;35(2):223–29. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawamura T, Muraoka I. Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Effects of Antioxidant Intake from a Physiological Viewpoint. Antioxidants (Basel). 2018. Sep 5;7(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Organ JM, Allen MR, Myers-White A, Elkhatib W, O’Neill KD, Chen NX, et al. Effects of treadmill running in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2018. Dec;16:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1. Study timeline CKD+Ctrl, CKD+Carn, and CKD+TM groups. Treadmill program details listed in the CKD+TM section.

Supplemental Table S1. Protocol used to individualize treadmill training.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.