The incorporation of lay perspectives in research and development in the health service is not only politically mandated in recent white and green papers but also has the potential to improve the relevance and impact of research and the quality of subsequent services.1 There are many ways of identifying lay views and incorporating these into decisions, but the methods used to achieve this need further evaluation. Traditional methods to encourage public participation—such as public meetings, patient participation groups, and complaints procedures—have met with limited success.2

During the past decade the technique named “rapid appraisal” has begun to make important contributions in the assessment of local needs and planning in the developed and developing countries (see box on p 441). Its use in the United Kingdom has been guided by the work of Chambers,3 Annett and Rifkin,4 and Ong,5 and Manderson and Aaby have described an “epidemic increase” in the use of this method.6 Rapid appraisal has now been used by community workers and primary healthcare teams to gain public involvement in the assessment of needs from the Isle of Skye to inner city London and from Belfast to Norway. Initially used for assessment of global needs it has also been used with specific groups of patients and to gain broad perspectives on accident and emergency services.7

Summary points

Rapid appraisal can be used to involve the public in the identification of local health needs and can supplement more formal methods of assessing needs

Rapid appraisal is best used in homogeneous communities: practice populations tend to be heterogeneous

Rapid appraisal can be modified to focus on the needs of specific groups of patients

The process of rapid appraisal can give a structured orientation to new workers in the community

Rapid appraisal can be adapted to introduce medical students to the concept of community diagnosis as a natural companion to individual clinical diagnosis

The technique of rapid appraisal

Rapid appraisal methods seek to gain community perspectives of local health and social needs and to translate these findings into action. Such methods have been designed to draw inferences, conclusions, hypotheses, or assessments in a limited period of time and are thus relevant to health service research.

Data are collected generally from three main sources:

Interviews with a range of local informants

Existing written records about the neighbourhood

Observations made in the neighbourhood or in the homes of the interviewees.

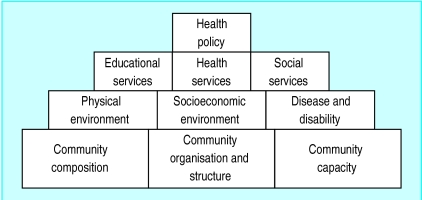

From the information thus collected an information “pyramid” can be assembled describing the neighbourhood’s problems and priorities (figure). The pyramid shape is a reminder that this method’s success depends on building a planning process that rests on a strong community information base.

The scientific rigour and the validity of the approach depend on triangulation. Data collected from one source are validated or rejected by checking with data from at least two other sources or methods of collection. Informants are not selected randomly but “purposefully”8—that is, asking a range of people who are in the best position to understand the issues. Professional insights can be incorporated by including relevant interviewees and summary health data from primary and secondary care. The World Health Organisation has published useful training materials.4

Rapid appraisal has great potential but also has important limitations. A sharing of practical experiences may be helpful for individual practices, groups of practices, and health authorities considering how to gain public involvement in assessing local health needs.

Public participation in assessing needs: five applications of rapid appraisal

In the first study an expanded primary healthcare team adapted this method to describe the health needs of a small housing estate of 1200 residents in central Edinburgh.9 In the second study, comprising the same population, a psychiatrist, community psychiatric nurse, and general practitioner focused an appraisal more specifically on mental health needs and suggested changes.10 In a third study three community psychiatric nurses, each with catchment areas of around 40 000 residents, used the format of rapid appraisal to orient themselves to their new areas while assessing the need for their services.11 Fourthly, with a population of 120 000 residents, an external researcher was commissioned to assess broad health needs with this approach—which in fact failed.12 Finally this technique was successfully used in a community profiling exercise in the University of Glasgow’s new undergraduate medical curriculum.13 Each of these studies is summarised below.

Study 1—Dumbiedykes health9

Objectives

—This study defined the broad health and social needs of a community and formulated joint action plans between the residents and local service providers.

Needs assessment team

—An expanded primary care team (general practitioner, health visitor, two social worker, and community education worker) carried out interviews in pairs.

Time spent

—Each member spent 4 hours a week on the study for 3 months.

Setting

—The study was carried out on a housing estate of 670 homes in central Edinburgh.

Results

—Top priorities for change were not related to the health service—such as a need for a bus to come into the estate; creation of play areas and dog free zones; the opening of a supermarket nearby. Suggestions to improve the running of local general practices and the care of people with mental illness were also raised.

Outcomes

—A health forum of residents and various professionals who worked in the area was created to meet regularly to seek to action changes. Those responsible for other sectors have responded enthusiastically to suggestions advocated by this forum, which is continuing after 4 years with strong involvement of social work, community education, housing, and voluntary sectors. The top priorities listed above have all been achieved.

Conclusions

—A primary care team can use rapid appraisal as a first step in the identification and meeting of local needs. Health professionals may play an effective part in encouraging local advocacy to other sectors. The rapid appraisal and subsequent health forum facilitated the meeting of local priority health needs.

Study 2—Mental health, alcohol, and drugs in Dumbiedykes10

Objectives

—The second study aimed to assess the needs that individuals, their carers, and the wider community have with respect to mental health problems and to seek suggestions for service developments from users and the wider community.

Needs assessment team

—The team comprised a community psychiatric nurse, a general practitioner, and psychiatrist. Interviews were carried out by the community psychiatric nurse alone, who spent about 1 day a week for 4 months on the study.

Setting

—The study was carried out on the same housing estate as study 1.

Results

—Many patients believed their most pressing problems were not related to health services but to employment, housing, and personal relationships. Many residents and local workers were concerned at the high concentration of people with mental health, alcohol, and drugs problems in the area. There was a lack of integration of mentally ill people into the local community. A change in housing allocation policy was considered the most useful intervention by many residents. A “one door” approach to health and social service provision was suggested.

Outcome

—A dialogue was initiated between the housing department and the local psychiatric directorate about clusters of mental illness within the locality to prevent mentally ill people from being “ghettoised.” A drop in club for the socially isolated was started in a community room.

Conclusions

—Rapid appraisal encouraged a holistic multidisciplinary approach to assessing the problems that mental illness, alcohol, and drugs can create for individual people, their relatives, and the wider community. A practice based community psychiatric nurse may have an important role in assessment of local needs. Rapid appraisal can be modified to focus on broad issues relating to a specific groups of patients.

Study 3—Assessing needs while orienting new practice based staff to their surroundings11

Objectives

—The third study concerned the introduction of newly employed community psychiatric nurses to their new neighbourhoods and examined local perceptions about mental health and illness.

Needs assessment team

—The team comprised three practice based community psychiatric nurses and a local general practitioner. Each nurse, with help from the author, carried out a rapid appraisal in his or her area. The findings were also collated to give a locality mental health profile.

Time spent

—Each community psychiatric nurse dedicated 6 hours a week during his or her first 3 months of employment.

Setting

—The study took place in three neighbourhoods each of 40 000 residents within south east Edinburgh.

Results

—The community psychiatric nurses were highly satisfied with their orientation to working in the community. An understanding of the broad health and health service needs of and available services for individuals with mental health problems living in the local communities was obtained by the nurses. Many suggestions for improving the quality of community and hospital based mental health services were received.

Outcome

—A single page directory of local mental health service resources was distributed to all practices. The locality commissioning general practitioners held a series of meetings with the local psychiatrists to voice community concerns about hospital based mental health services.

Conclusions

—This orientation exercise provided a structured induction for practice based community psychiatric nurses. The exercise also provided the nurses with community perspectives on need. The same process could also be used for other new primary healthcare workers.

Study 4—Community perceptions of health needs in south east Edinburgh12

Objectives

—This study aimed to assess public perceptions about local health needs and healthcare services and to gain views on how services could be improved.

Needs assessment team

—An external researcher with community development training was assisted by a general practitioner. They intended to carry out a rapid appraisal but this was considered impractical as the area under study was large and comprised several communities each of which could have been studied individually with rapid appraisal. Focus groups were used as an alternative, and these explored issues around the quality and coverage of primary care services.

Time spent

—The outside researcher spent 2 days a week for 3 months on the study.

Setting

—The area of study was in south east Edinburgh (120 000 residents)

Results

—Rapid appraisal could not be used as the area was too large but, more importantly, too diverse.

Outcome

—An alternative method was used, consisting of focus groups alone.

Conclusions

—Rapid appraisal could not be carried out without subdividing the area into natural communities where key informants are more likely to be knowledgable about local problems. There were insufficient resources for this. Rapid appraisal works best in small homogeneous communities. Large communities are likely to be diverse.

Study 5—Development of a community diagnosis exercise for medical students13

Objectives

—The last study introduced community diagnosis at an early stage of medical education as a natural companion to clinical diagnosis and by so doing actively engaged medical students in exploring local health and social needs.

Design

—Facilitated by local general practitioner tutors, groups of eight first year medical students working in pairs interviewed patients, carers, and local key informants about their perceptions of health and health needs. These findings were collated and contrasted with routinely available practice, hospital, census, and mortality statistics.

Time spent

—Students underwent three 3 hour sessions during the first year of their course.

Setting

—The students worked in 24 general practices around Glasgow.

Results

—Students were able to discover and show that individual key informants, health professionals, and health services each had different priorities and perspectives on needs for health and social care. Interviewing local residents and workers from other sectors added detail, depth, and hence understanding of the routine statistics.

Outcome

—The students gained opportunities within a community setting to learn actively about and see the social and environmental factors which determine health. The practice tutors were also informed by the process.

Conclusions

—Rapid appraisal promoted problem based learning about different perspectives regarding health and social needs. Students valued learning about the contrasting perspectives and information provided by different sources.

Discussion

Both “rapid appraisal” and “rapid epidemiological assessment” (when epidemiological and statistical methods are used alone for rapid health assessment14) offer alternatives to more formal resource intensive methods of gaining public and professional perceptions of need. Rapid appraisal has limitations and values, which are discussed in the light of the above case studies. Several of these issues are common to other methods of assessment of health needs or local health research in general.

Limitations

Bias

—Bias can occur when informants are chosen from groups that share similar views and are not offset with informants who may have a different view. This could result in inequitable provision of service or the neglect of minority groups of people with rare but important conditions. A researcher bias may exist because of professional training, ethnicity, sex, and theoretical perspectives. This may be minimised by using a multidisciplinary team or using local volunteers for interviewing, who might more easily tap the private accounts which people do not release to strangers. Bias might also result from the interviewer’s own subjectivity in listening, transcription, or analysis.

Limited data used

—Rapid appraisal allows only a brief time frame and uses limited resources. Thus discipline and focus are required to seek only those informants rich in information and highly relevant sources of routine data, which might guide and facilitate action. This time constraint allows only “proportionate accuracy,” and statistics so produced must be interpreted cautiously as they may be based on routinely collected data which may be of questionable accuracy, completeness, and reliability.

Training necessary for interviewing and understanding the technique

—Training is necessary to understand how the method might best be used in a specific context. Ong et al in South Sefton facilitated an initial 2 day workshop for the local team.15 They formulated interview schedules, scrutinised available data, and discussed potential informants. In Edinburgh an outside trainer was not used but WHO guidelines were followed closely,4 which cover the above points and give examples to consider. When outside researchers were used it showed just how much “soft” local information primary care clinicians know.

Project coordination can be logistically difficult

—The work can be intense and time consuming because of arranging meetings, writing up and analysing the data, and writing reports. Public participation, if taken seriously, takes time, effort, organisation, and patience. Time and effort spent on such an activity does of course bear an opportunity cost, which must be considered.

The difficulty of working with diffuse practice populations versus communities

—This is well documented16 and must be considered when rapid appraisal is implemented in primary care. Much demographic, census, and public health data are collected and analysed at ward level. Practice populations are often spread across several wards. Conversely, a single ward may be served by dozens of practices. Incorporation of both practice and area based data therefore requires care. A more geographic zoning of practice populations would substantially facilitate needs assessment.

Values

Rapid appraisal is community oriented

—Primary care clinicians require a balanced awareness of individual patient needs and of population-wide requirements. Individuals can be fully understood only in their social contexts, and populations can be understood in greater depth if there is contact with individual members. Rapid appraisal can furnish clinicians and managers with richer insights into local communities than can routine practice data and encourages community oriented primary care.17 Our rapid appraisal findings were necessarily context specific. Studies of similar areas have, however, found similar insights.

Necessity of public involvement

—Rapid appraisal involves lay people in assessing and planning. In these studies lay views and knowledge of local residents were clearly expressed. Available (but not generally accessed) resources were tapped, and in depth information about the area evolved. Most importantly this community development approach facilitated changes in health and non-health services. In Dumbiedykes a “health forum” continues to meet every 3 months to advocate changes to improve the quality of life locally.

Multisectoral nature and promotion of networking

—The participation of other local workers as key informants enabled them to speak out on health issues. The concept of community profiling is understood well by health visitors, social workers, housing officials, and some other sectors, which allowed the concept of rapid appraisal to be easily understood as a method of involving the public in community profiling. A further and more fundamental reason why a multisectoral approach is necessary is that other sectors may be more important for health and wellbeing than health services. Because people’s broad perspectives were heard, health service interventions (such as a call for more district nurses) were weighed against other options (such as the campaign to get a bus into the estate) to improve the quality of life locally.

Promotion of equality

—Rapid appraisal gives an adaptable structure to tackle inequalities in health in primary care.18 If more opportunities for participation in health are created for the whole of society, however, the most privileged sectors will probably be more adept at seizing them, illustrating the inverse care law. Thus it is important to focus on deprived areas otherwise rapid appraisal could promote a further unequal distribution of resources. There is no reason to consider that rapid appraisals should not work in more affluent communities, but it is the poor who need most help.

Rapid appraisal is flexible and multimethod

—Rapid appraisal provides an adaptable structure (the information triangle) to hold together data from various sources. In the second study a specific box was labelled “mental health services” to gather relevant observations, available written data, and interview data about such services. Rapid appraisal is in itself multimethod and can incorporate data that are immediately available from primary and secondary care or from the national census. A limited data collection exercise can be considered part of the appraisal and the results incorporated in the relevant box of the information triangle for consideration with the other sources of information. Often, however, useful summary data from such sources are not quickly available and separate exercises are required to collect such data which can be analysed at a later date. Focus group data, say from a meeting of a local residents committee, can supplement the interview data. Local workers or external researchers can use this method, although local ownership of the research process may make suggestions more likely to be actioned.

Rapid appraisal is satisfying

—Fostering closer links with community leaders and workers was rewarding for the researchers and gave them an increased knowledge of available community resources useful to their patients and clients. A clear view emerging from those general practitioners who have cultivated links with the community is that working like this can greatly improve job satisfaction.19 We found that patients’ expectations were realistic when they were informed and involved in discussions. Far from making huge and unreasonable demands, patients and community members made practical and achievable suggestions.

Rapid appraisal and other methods of assessment

A critical assessment of the use of rapid appraisal in the first study described above was carried out by applying three more traditional methods of assessment to the same population. These were postal survey, collation of data held in general practice and analysis of routinely available small area statistics.20 It was found that a postal survey can usefully give extra data about acute and chronic illness in the community and perceived needs for existing and potential services for both users and non-users. Practice data, increasingly accessible through computerisation, can best detail morbidity presenting to primary care, prescribing, and health promotion activities. Routine local statistics can detail socioeconomic indicators and allow comparisons with regional norms, which rapid appraisal did not permit. Each method yielded particular insights into health needs. Jordan and Wright have suggested that assessment of needs should be approached in much the same way as doing a jigsaw so that different pieces are put together to give a complete picture of local health.21 Rapid appraisal can provide key pieces of the jigsaw but not the complete picture.

Conclusions

Professionals and politicians need the public’s insights concerning health. Efforts are being made to establish some hierarchy of public priorities for health care. Unfortunately this process usually asks about a restricted set of health services22 rather than asking more fundamentally about what people think will improve their health. We found generally that people thought that health service issues were not a particular priority for them. They believed that health and the environment were inextricably linked and that solutions are beyond health care, which professionals are now confirming.23,24 They felt more competent to discuss housing, work, stress, and the local general practice and community nursing services rather than prioritise more distant health services.

Rapid appraisal is best applied to a population that can be considered as a community in some sense of the word. This technique may have a useful role to help primary care groups in England and local healthcare cooperatives in Scotland to assess needs while ensuring that the views of their local communities are ascertained; but the issue of size arises. While primary care groups are intended to relate to “natural communities” of around 100 000, each group will include a number of different and varied communities: communities of place, of membership of a minority ethnic group, of suffering from the same illness, or of people who share the experience of, say, being a single mother or living in poverty.25 Subdividing of these primary care groups into more natural groupings or neighbourhoods, where key informants are knowledgeable about local issues, will be necessary to listen to the multitudes of voices waiting to be heard. Priority should be given to study and help the poorer communities within primary care groups and promote equity, and rapid appraisal can help formulate a community development approach to permit this.

Time, inclination, and training are necessary for assessment of needs to function, especially with public participation. Rapid appraisal offers a practical way of involving the community in assessing and meeting needs, and the process itself may facilitate change. As an orientation and training process it promotes the attitudes and skills which professionals need to work effectively in the community. Its value to the NHS will depend on whether the process and data it generates is seen to be of use for purposes of public involvement and resource allocation. At worst rapid appraisal has the potential to be a misused tool to collect poor information for supporting decisions already made. At best it has the potential to give substance and effect to the rhetoric of community participation by providing tools, techniques, and data useful to primary care clinicians and managers. Health authorities and primary care trusts may facilitate local public involvement by providing training, protected time, and logistical support to primary care groups to allow them to hear the many local voices.

Figure.

Information pyramid constructed for rapid participatory appraisal

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all the authors involved in the five studies (references 9-13 below) which form the basis of this paper, and especially to H Davison, S Capewell, J Macnaughton, P Hanlon, and J McEwen, who developed the community diagnosis exercise in Glasgow, for allowing me to include it in this paper. I am also grateful to J Howie, D Black, S Gillam, and J Chowings for commenting on this article.

Footnotes

Funding: Lothian Health Promotion Department funded the first study, and Lothian Health Primary Care Development Fund assisted with studies three and four.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Entwistle VA, Renfrew MJ, Yearley S, Forrester J, Lamont T. Lay perspectives: advantages for health research. BMJ. 1998;316:463–466. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillam S, Murray SA. Needs assessment in general practice. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1996. (RCGP Occasional Paper No 73). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers R. Whose reality counts? Putting the first last. London: Intermediate Technology Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annett H, Rifkin SB. Guidelines for rapid participatory appraisal to assess community health needs. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong BN. Rapid appraisal and health policy. London: Chapman and Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manderson L, Aaby P. An epidemic in the field? Rapid assessment procedures and health research. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:839–850. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90098-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale J, Shipman C, Lacock L, Davies M. Creating a shared vision of out of hours care: using rapid appraisal methods to create an interagency, community oriented, approach to service development. BMJ. 1996;312:1206–1210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson JC. Selecting ethnographic informants. London: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray SA, Tapson J, Turnbull L, McCallum J, Little A. Listening to local voices: adapting rapid appraisal to assess health and social needs in general practice. BMJ. 1994;308:698–700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6930.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray SA, Chick J, Perry B. Mental health, alcohol and drugs: constructing a neighbourhood profile. Primary Care Psychiatry. 1996;2:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray SA, Fraser A. Careering around. Health Service J. 1997;107:32–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black D, Murray SA. “They’re better trained noo but they’re no family doctors”. Some community perceptions about the quality of primary care services. Glasgow: Communicable Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison H, Capewell S, Macnaughton J, Murray SA, Hanlon P, McEwen J. Community-oriented medical education in Glasgow: developing a community diagnosis exercise. Med Educ. 1999;33:55–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anker M. Epidemiology and statistical methods for rapid health assessment: introduction. World Health Stat. 1991;44(2):94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong BN, Humphries G, Annett H, Rifkin S. Rapid appraisal in an urban setting, an example from the developed world. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:909–915. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopton JL, Dlugolecka M. Need and demand for primary health care: a comparative survey approach. BMJ. 1995;310:1369–1373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6991.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillam S, Miller R. COPC—a public health experiment in primary care. London: King’s Fund; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benzeval M, Judge K, Whitehead M. Tackling inequalities in health: an agenda for action. London: King’s Fund; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neve H, Taylor P. Working with the community: general practitioners could gain much from greater involvement. BMJ. 1995;311:524–525. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7004.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray SA, Graham LJC. Practice based health needs assessment: use of four methods in a small neighbourhood. BMJ. 1995;310:1443–1448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6992.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan J, Wright J. Making sense of health needs assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47:695–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon J, Welch HG. Priority settings: lessons from Oregon. Lancet. 1991;337:891–894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson E. The woman on the kerb: health and the environment are inextricably linked. BMJ. 1994;309:142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judge K. Beyond health care. BMJ. 1994;309:1454–1455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6967.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHS Executive. In the public interest: developing a strategy for public participation in the NHS. London: Department of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]