Abstract

It is of great interest for gene therapy to develop vectors that drive the insertion of a therapeutic gene into a chosen specific site on the cellular genome. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is unique among mammalian viruses in that it integrates into a distinct region of human chromosome 19 (integration site AAVS1). The inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) flanking the AAV genome and the AAV-encoded nonstructural proteins Rep78 and/or Rep68 are the only viral elements necessary and sufficient for site-specific integration. However, it is also known that unrestrained Rep activity may cause nonspecific genomic rearrangements at AAVS1 and/or have detrimental effects on cell physiology. In this paper we describe the generation of a ligand-dependent form of Rep, obtained by fusing a C-terminally deleted Rep68 with a truncated form of the hormone binding domain of the human progesterone receptor, which does not bind progesterone but binds only its synthetic antagonist RU486. The activity of this chimeric protein, named Rep1-491/P, is highly dependent on RU486 in various assays: in particular, it triggers site-specific integration at AAVS1 of an ITR-flanked cassette in a ligand-dependent manner, as efficiently as wild-type Rep68 but without generating unwanted genomic rearrangement at AAVS1.

One of the major goals of gene therapy is to develop safe and reliable systems for the prolonged expression of a therapeutic gene (9). This result can be achieved by promoting integration of the desired DNA sequence into a predetermined site on the host genome (14). Therefore, considerable interest has been raised by the observation that the adeno-associated virus (AAV) integration machinery can be used for directing the integration of a transgene into a specific site on the human genome (31, 44).

AAV is a human defective parvovirus whose single-stranded genome, 4.7 kb long, is flanked by two inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and comprises two open reading frames (ORFs) called rep and cap, which code for nonstructural and structural proteins, respectively (4). AAV replicates only in cells coinfected by a helper virus, such as adenovirus (Ad) or herpes simplex virus, or undergoing genotoxic stress, such as UV treatment or X-ray irradiation (4). Under conditions which are not permissive for replication, AAV establishes a latent infection in which the viral genome integrates stably and efficiently into a defined region, AAVS1, of human chromosome 19 (q13.3-qter) (4, 26, 27, 44, 46).

The precise molecular mechanisms underlying AAV integration have not yet been fully elucidated, but it has been clearly established that two viral elements are required: the 145-bp ITRs and the Rep78 and/or Rep68 protein encoded by the rep ORF (14, 24, 31, 65). Rep78 and Rep68, which are respectively 623 and 536 amino acids (aa) long, are expressed from alternatively spliced transcripts initiated at the same promoter (the p5 promoter) and therefore differ only at their carboxy termini (4). The two proteins, which are essential not only for integration but also for AAV replication, have several biochemical activities in common: they both interact with a specific DNA sequence (Rep binding site) and they both have a strand- and site-specific endonuclease activity and an ATP-dependent DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA helicase activity (22, 23). In addition, they are able to modulate the activity of endogenous as well as heterologous promoters (21, 29, 39). In vitro and ex vivo experiments suggest that the earliest step in the integration process is when Rep78 and/or Rep68 tethers the two Rep binding sites present in the AAV ITR and in AAVS1 (8, 9, 15, 60). Following the formation of this Rep-mediated complex between AAV DNA and its target site in chromosome 19, Rep78 and/or Rep68 is postulated to specifically nick DNA within the ITR and AAVS1; subsequently, integration is likely to occur via a nonhomologous recombination process mediated by replication of the integrating DNA with the active participation of host factors responsible for DNA synthesis (32, 33, 56, 65).

The limited length of the DNA sequence which can be packaged into AAV particles, coupled with the need to maintain the rep ORF, precludes the use of AAV itself as a delivery vector for promoting site-specific integration of a transgene (14). However, recent results indicate that the AAV integration machinery works quite efficiently also when incorporated into a variety of alternative nonviral and viral delivery systems (31). It has in fact been demonstrated that Rep78 and/or Rep68, when delivered to cells either as an expression plasmid or as a recombinant protein, promotes the site-specific integration of an AAV ITR-flanked cassette contained in the same or in a separate plasmid (2, 30, 47, 52, 55). Furthermore, it was recently shown that a baculovirus/AAV hybrid vector, which carries both an AAV ITR-flanked transgene and a Rep expression cassette, was capable of driving integration of the ITR-flanked transgene at AAVS1 (38).

In considering the Rep78/68-based integration system as a new approach to gene therapy, it would be highly desirable to restrict Rep78/68 activity in target cells only to the time required for site-specific integration to occur, in order to minimize additional and possible detrimental effects. In fact, it has been shown that Rep proteins down-regulate the expression of human genes such as c-H-ras, c-fos, c-myc, and c-sis (18, 19, 62) and can inhibit the proliferation of some cell lines (4, 68). A further fact for consideration is that Rep-mediated integration at AAVS1 can lead to nonspecific genomic rearrangements at the same locus, and the frequency and severity of these might be attenuated or suppressed by setting a time limit to the activity of Rep proteins in target cells (2, 52).

With this in mind, we decided to generate an inducible form of Rep78/68 whose activity could be controlled by an externally added small-molecule ligand. In this paper we describe the construction of a ligand-dependent Rep chimeric protein, made up of a C-terminal Rep68 deletion mutant fused with a truncated form of the hormone binding domain (HBD) of the human progesterone receptor (PR), known to interact with the synthetic steroid RU486 but not with endogenous progesterone (3, 5, 57). This Rep/HBD fusion protein displays strictly RU486-dependent activity in a wide array of functional assays and promotes site-specific integration at AAVS1 without major nonspecific genomic rearrangements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis.

Expression vectors for Rep78 and Rep68 (plasmids pCMV/Rep78 and pCMV/Rep68) were obtained by cloning the coding regions for Rep78 and Rep68 under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer-promoter element contained in plasmid pcDNAIII (30). To obtain the cDNAs coding only for Rep78 or Rep68, the rep ORF, spanning from nucleotides 321 to 2252 of the AAV-2 genome (51), was subjected to PCR-based mutagenesis with the AAV-2 genome contained in plasmid pTAV2 (17) as a substrate. To generate the cDNA coding for Rep78, the internal start methionine for the small Rep proteins (Rep52 and Rep40) was mutated to glycine (nucleotides 993 to 995, ATG changed to GGA) and the splice donor site required for the expression of the spliced version Rep68 was eliminated by introducing a G-to-A transversion at nucleotide 1907 (30). The cDNA for Rep68 was obtained by first mutating the internal translational AUG as described above and then deleting the entire intron (positions 1907 to 2227) (30). C-terminal Rep68 deletion mutants (Rep1–484, Rep1–491, Rep1–502, and Rep1–520) were obtained by inserting stop codons at appropriate positions in the context of pCMV/Rep68 by PCR-mediated site-specific mutagenesis (1). Expression plasmid pCMV/Rep contains the whole rep ORF, with no mutations, cloned downstream of the CMV enhancer/promoter in plasmid pcDNAIII and codes for all four species of Rep. The cDNAs coding for the C-terminal deletion mutants were then cloned into pcDNAIII, thus creating expression plasmids pCMV/Rep1–484, pCMV/Rep1–491, pCMV/Rep1–502 and pCMV/Rep1–520. All Rep/PR fusions (Rep78/PR, Rep78int/PR, PR/Rep78, Rep68/PR, Rep68int/PR, PR/Rep68, Rep1–491/P, and Rep1–484/Pn) were generated by a PCR-based mutagenesis strategy: their corresponding cDNAs were cloned into pcDNAIII downstream of the CMV enhancer/promoter element, thus generating the expression vectors pCMV/Rep78/PR, pCMV/Rep78int/PR, pCMV/PR/Rep78, pCMV/Rep68/PR, pCMV/Rep68int/PR, pCMV/PR/Rep68, pCMV/Rep1–491/P, and pCMV/Rep1–484/Pn. The sequences of all mutants and fusions were verified by the dideoxy-sequencing method (1). The sequences of all oligonucleotides used for PCRs are available on request. Plasmid p5/LUC was constructed as follows: the p5 promoter region (nucleotides 1 to 319 of the AAV-2 sequence) (51) was PCR amplified from psub201 and then cloned as an EcoRV-HindIII fragment upstream of the luc gene contained in plasmid pGL2-Basic (Promega). Plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo, containing the expression cassette for the neomycin resistance gene (neo) and for the Hook gene, has been described previously (30). Plasmid pT7bhPRB-891, containing the C-terminal deletion of the HBD of the human progesterone receptor, was a generous gift of B. O'Malley and S. Tsai.

Cell culture and transfections.

293, HeLa, and Hep3B cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum plus glutamine and antibiotics at 37°C in 5% CO2. All transfections were performed by the calcium phosphate procedure (1).

Immunoblot analysis of transiently transfected cells and of stable transformants.

For analysis of Rep expression, 3 × 105 cells (Hela, 293, or Hep3B) were transfected with 10 μg of the various expression plasmids. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and total cellular extracts were prepared as described previously with minor modifications (53). Briefly, the cells were lysed in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–5 mM EDTA–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) by passage through a 1-ml syringe. The lysate was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid at room temperature for 15 min and then left in ice for additional 10 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min, pellets were washed in ice-cold acetone, resuspended in 60 μl of sample buffer, and incubated at 65°C for 15 min and then at 100°C for 3 min. Equivalent amounts of proteins were fractionated on an 8% polyacrylamide–SDS gel, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and detected by sequential incubation with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against AAV Rep proteins (dilution, 1:1,000) and then with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rat polyclonal anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antiserum (Promega no. S3731; dilution, 1:4,000). The polyclonal antiserum against Rep proteins was obtained by immunizing rabbits with purified recombinant Rep68 produced in Escherichia coli (30) and recognizes all four species of Rep.

To check the expression of the Hook gene product (sFv/PDGFR fusion protein) (6) in the stable transfectants, total cellular extracts were prepared as described above, fractionated on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. To detect the sFv/PDGFR fusion protein, the membranes were incubated first with monoclonal antibody 9E10.2 (dilution, 1:500), which recognizes the Myc.1 epitope tag (13) present as a tandem repeat near the transmembrane domain of sFv/PDGFR (6), and then with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat polyclonal anti-mouse IgG antiserum (Sigma no. A7434; dilution, 1:2,000). In all immunoblotting experiments, 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) was used as a blocking agent and for diluting the various antibodies.

Immunofluorescence experiments.

For immunofluorescence assays, cells (Hep3B, 293, or HeLa) were grown on glass coverslips and transfected with 10 μg of the expression vectors for the various Rep derivatives. At 36 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed with 3% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 20 min, washed with PBS, and incubated in 0.1 M glycine in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, the cells were permeabilized by incubation at room temperature for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and after a washing step, they were incubated for 20 min with the rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against AAV Rep proteins (diluted 1:200 in 10% goat serum in PBS). They were then washed with PBS and incubated for an additional 20 min with a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Pierce No. 31572; diluted 1:100 in 10% goat serum in PBS). After sequential washing steps in PBS and distilled water, the coverslips were mounted in Moviol containing 1 mg of para-phenylenediamine per ml and photographed by epifluorescence on a Leica Diaplan photomicroscope with fluorescein filters and a 63x planar objective.

p5 promoter repression assay.

For analysis of Rep repressing activity, 3 × 105 293 or HeLa cells were seeded in a 60-mm-diameter dish; 20 h later, they were cotransfected with 50 ng of the various expression plasmids and 5 μg of p5/LUC. At 15 h later, the cells were washed, and 100 nM RU486 was added to some of the cells. After 36 h, the cells were collected in 40 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5), centrifuged, resuspended in 250 mM Tris (pH 8.0), and lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was used for quantitation of luciferase activity as described previously (1) by using a Lumat luminometer (Berthold). Luciferase activity in cell lysates was normalized to the corresponding protein concentration.

Rescue-replication assay.

A total of 1.2 × 106 HeLa, 293, or Hep3B cells were seeded in a 10-mm-diameter dish and 18 h later were infected with Ad2 at a multiplicity of infection of 10. After 2 h of incubation, the medium was changed and the cells were transfected with 10 μg of plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo with or without 10 μg of the expression vectors for wild-type wt Rep78, Rep68, or their various derivatives. At 15 h after transfection, the cells were washed and incubated with fresh medium containing or not containing 100 nM RU486. At 48 h later, low-Mr DNA samples were isolated from cells by the procedure described by Hirt (20), digested extensively with DpnI (62), and analyzed by Southern blotting with a 32P-labeled DNA probe specific for neo sequence (1, 30).

In vitro translations.

Rep68, Rep1–484, Rep1–491, Rep1–502, and Rep1–520 were translated in vitro from plasmids pCMV/Rep68, pCMV/Rep1–484, pcDNA/Rep1–491, pcDNA/Rep1–502, and pcDNA/Rep1–520, respectively, with the TnT-T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer. The quantity of proteins used for in vitro experiments was normalized by densitometric analysis (with the GS-700 imaging densitometer with Molecular Analyst software [Bio-Rad]) of SDS-polyacrylamide gels loaded with increasing quantities of the various in vitro translation products.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed with 20,000 cpm of 32P-end-labeled AAV ITR. Reaction mixtures (10 μl) contained 10 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.9), 8 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), and different amounts of the in vitro-translated proteins. Following a 20-min incubation at room temperature, 2 μl of 20% Ficoll was added, samples were loaded on 4% polyacrylamide gels (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 29:1; 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE]) and electrophoresed at room temperature at 10 V/cm. The gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography for 6 h at −80°C.

trs endonuclease assay.

Endonuclease assays were performed essentially as previously described, using substrates with a single-stranded terminal resolution site (30, 48). Briefly, the double-stranded XbaI-PvuII fragments from plasmid psub201 (45) containing the AAV ITRs, were dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, purified from agarose gels, 5′-end labelled with polynucleotide kinase, and loaded on 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gels. The plus (trs+) strand was eluted from the gels in 0.5 M ammonium acetate (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA and annealed. For the endonuclease assay, the reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.4 mM ATP, 0.2 μg of bovine serum albumin, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 20,000 cpm of 32P-end-labeled substrate, and different amounts of the in vitro-translated proteins. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, the reactions were stopped with proteinase K for 30 min at 65°C, and the products were subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction, ethanol precipitated, and analyzed on an 8% sequencing gel.

PCR assay for site-specific integration.

For each assay, 1.2 × 106 HeLa cells were seeded in a 10-mm-diameter dish and 20 h later were cotransfected with 10 μg of the ITR/Hook-Neo plasmid alone or with 10 μg of one of the Rep or Rep/PR fusion expression plasmids. Transfected cells were serially passaged for 14 days. Total genomic DNA was then extracted (1), and 500 ng was used as a template for two consecutive rounds of nested PCR amplifications performed with two matched couples of ITR-specific and AAVS1-specific primers as described previously (30). The PCR products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized with an AAVS1-specific probe spanning nucleotides 210 to 1207 of the published AAVS1 sequence (27). For molecular cloning of the amplified ITR/AAVS1 junctions, the products of the second round of amplification which were detectable on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels were purified, filled with Klenow enzyme, cloned into plasmid pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene), and sequenced by the dideoxy sequencing method (1).

Isolation and Southern blot analysis of neomycin-resistant clones.

A total of 106 HeLa cells were seeded in a 10-mm-diameter dish and 20 h later were cotransfected with 10 μg of ITR/Hook-Neo plasmid and 10 μg of plasmid pCMV/Rep68 or pCMV/Rep1–491/P. At 15 h later, after a washing step, the cells cotransfected with pCMV/Rep1–491/P were treated for 12 h with 100 nM RU486 or left untreated. Subsequently, the medium was changed again and the cells incubated in normal medium for an additional 36 h. Selection was then carried out by growing cells in the presence of 700 μg of G418 per ml (70.6% active; effective concentration, 494.2 μg/ml). After 14 to 18 days of growth in selective medium, single-cell neomycin-resistant clones were isolated and expanded. For Southern blot analysis, genomic DNA was extracted and purified by standard procedures (1), digested with the restriction enzyme BamHI, and blotted onto a nylon membrane, which was sequentially hybridized with AAVS1- and neo-specific probes by published methods (1). The AAVS1-specific probe was a DNA fragment (derived from plasmid pRVK [K. Berns, Cornell Medical School, Ithaca, N.Y.]) spanning nucleotides 1 to 3525 of AAVS1, which was labelled with 32P by the random-priming reaction. A DNA fragment of 630 bp was used as a template in the random-priming reaction for generating the neo-specific probe.

RESULTS

RU486-dependent nuclear localization of full-length Rep78 and Rep68 fused to the HBD of the progesterone receptor.

To obtain ligand-dependent Rep78 and/or Rep68 proteins, we decided to generate fusions with a 42-aa C-terminal deletion of the human PR891-HBD (57). PR891-HBD (aa 642 to 891 of the human PR) was chosen because it binds synthetic progesterone antagonists, such as RU486, but not the progesterone or other natural steroids (5, 57); therefore, the activity of heterologous proteins fused to PR891-HBD cannot be affected by natural steroids (25, 50).

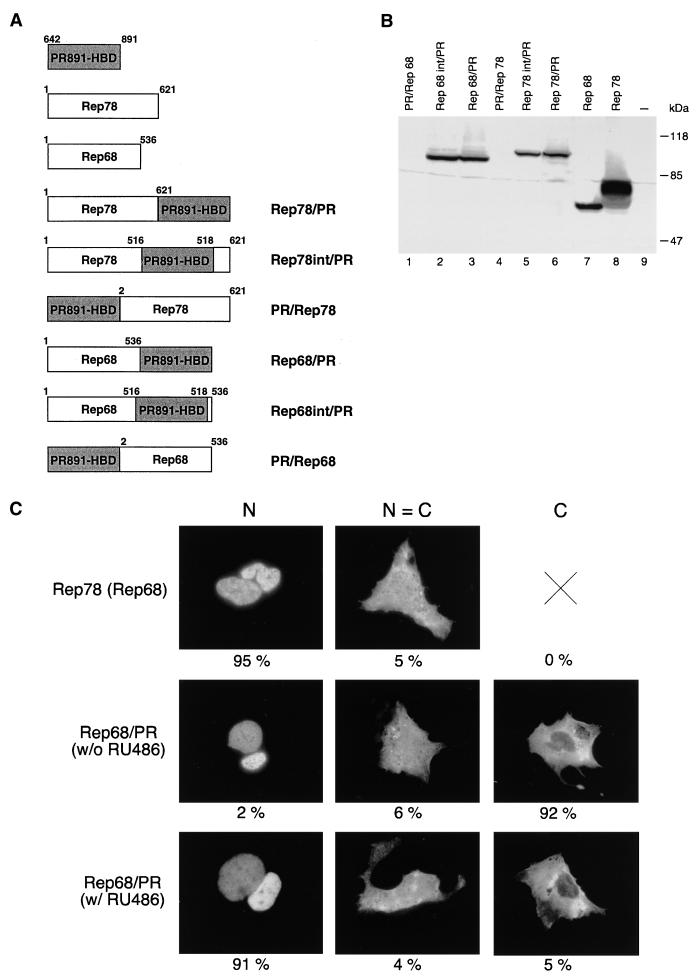

Since it is not possible to exactly anticipate on a rational basis the position in which the HBD must be fused with the heterologous moiety to obtain a stable, properly folded and ligand-dependent chimera, we constructed several different fusions. In four of them, the HBD was cloned either at the N terminus (PR/Rep78 and PR/Rep68) or at the C terminus (Rep78/PR and Rep68/PR) of both Rep78 and Rep68 (Fig. 1A). We also constructed two additional chimeras in which the HBD was introduced at the level of the splicing site (Rep78int/PR and Rep68int/PR [Fig. 1A]). In fact, evidence reported in the literature suggests that the splicing site in the rep ORF delimits a distinct C-terminal domain of the protein (12, 21); we therefore reasoned that insertion at this point should not dramatically affect protein folding and, with respect to C-terminal fusions, should bring the HBD in closer contact with the regions of Rep78/68 known to be important for DNA binding and nicking (11, 34, 37, 55, 61, 67).

FIG. 1.

Structure, expression, and intracellular distribution of fusion constructs derived from wt Rep78 and Rep68. (A) Diagram of the different chimeras made up of full-length Rep78 or Rep68 fused with the PR891-HBD. For all constructs, the HBD was the same (residues 642 to 891 of the human progesterone receptor). For PR891-HBD, Rep78, and Rep68, the numbers above the diagrams refer to the amino acid positions. For the fusions, the numbers do not refer to the amino acid position in the context of the fusion protein but instead indicate the amino acid positions of the corresponding parental Rep protein. (B) Expression levels of the various fusions in transiently transfected HeLa cells. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from HeLa cells transfected with the expression vectors for wt Rep78, wt Rep68, and the six different chimeras. wt Rep78, wt Rep68, and their derivatives were detected by immunoblotting with a rabbit polyclonal serum against Rep proteins. Lane 9 contains untransfected cells. (C) Representative micrographs of the staining patterns observed in Hep3B cells transfected with Rep78, Rep68, and the various Rep/PR fusions. Hep3B cells were transfected with 10 μg of the expression vectors pCMV/Rep78, pCMV/Rep68, and pCMV/Rep68/PR. In this last case, cells were treated (w/ RU486) or not (w/o RU486) with 100 nM RU486. The cells were stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the Rep moiety (see also Materials and Methods). The staining was classified into three categories: N, predominantly nuclear fluorescence; C, predominantly cytoplasmic staining; N = C, equal cytoplasmic and nuclear staining. At least 1,000 stained cells, obtained from a minimum of three experiments, were scored for each protein. The numbers below the micrographs represent the percentage of cells falling into each category.

Expression vectors for the six fusions were transfected into human adenocarcinoma-derived HeLa cells, and their expression levels were assessed by Western blotting experiments. As shown in Fig. 1B, the N-terminal fusions were undetectable in transfected cells (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 4) while the expression levels of the other four fusions were comparable to that of wt Rep68 (Fig. 1B, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). Similar results were obtained in Ad-transformed human embryonic kidney 293 cells and human hepatoma Hep3B cells (not shown). Notably, N-terminal fusions were produced by in vitro translation as efficiently as the wt Rep proteins were (data not shown), suggesting that their low expression in cells is due to intracellular instability. Further analysis was therefore restricted only to the four chimeric proteins expressed in vivo, namely, Rep78/PR, Rep78int/PR, Rep68/PR, and Rep68int/PR.

Rep78 and Rep68 are intranuclear proteins (21, 66); therefore, before testing the functional activity of our four chimeric proteins, we first analyzed their intracellular localization. Expression vectors for Rep78/PR, Rep78int/PR, Rep68/PR, and Rep68int/PR were thus transfected into Hep3B cells treated or not treated with 100 nM RU486, and the subcellular distribution of the fusion proteins was monitored by immunofluorescence analysis (see Materials and Methods). Control experiments were performed with Rep78 and Rep68. For each type of protein, at least 1,000 stained cells were analyzed and classified into three categories: N, containing cells showing predominantly nuclear staining; C, containing cells with predominantly cytoplasmic staining; and N = C, containing cells in which cytoplasm and nucleus are equally stained. The results were expressed as the percentages of stained cells in each category; they are summarized in Table 1, and examples of the immunocytochemical presentation of cells scored in the three different categories are shown in Fig. 1C. As expected, Rep78 and Rep68 showed a clear nuclear localization (N = 95% [Table 1 and Fig. 1C]). In contrast, Rep78/PR, Rep78int/PR, Rep68/PR, and Rep68int/PR were confined predominantly to the cytoplasm in the absence of RU486 (C ≥ 90% and N ≤ 2% [Table 1]) but migrated into the nuclei following hormone treatment (N ≥ 90% [Table 1]): representative results obtained with the Rep68/PR fusion are shown in Fig. 1C. These results were also obtained with HeLa and 293 cells (not shown) and demonstrated that within the sensitivity limits of immunofluorescence, nuclear translocation of the fusion proteins was under quite stringent hormonal control.

TABLE 1.

Effects of RU486 on the intracellular distribution of full-length Rep78 and Rep68 fused with PR891-HBD

| Protein | RU486 treatmenta | Intracellular localization (%)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N = C | C | ||

| Rep78 and Rep68 | − | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| Rep78/PR | − | 1 | 7 | 92 |

| + | 90 | 6 | 4 | |

| Rep78int/PR | − | 2 | 4 | 94 |

| + | 92 | 3 | 5 | |

| Rep68/PR | − | 2 | 6 | 92 |

| + | 91 | 4 | 5 | |

| Rep68int/PR | − | 1 | 4 | 95 |

| + | 91 | 4 | 5 | |

−, transfected cells were untreated; +, 100 nM RU486 was added to the culture medium.

Stained Hep3B cells were classified as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. At least 1,000 stained cells, obtained in three or more experiments, were analyzed for each protein, and the results are expressed as the percentage of cells included in each category.

The activity of full-length Rep78 and Rep68 fused to PR HBD is not hormone dependent.

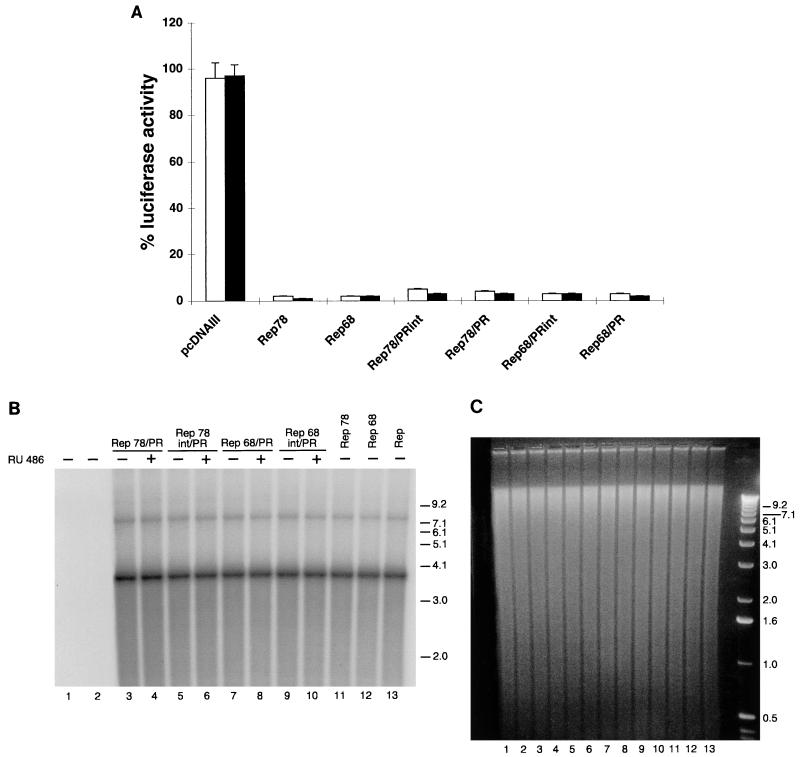

To determine whether the activity of the four chimeric constructs was hormone dependent, we tested them in a transcription repression assay. Rep78 and Rep68 inhibit transcription starting from the AAV p5 promoter (21, 29, 39). Expression vectors for the Rep/PR fusions were thus cotransfected with a plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of the p5 promoter (plasmid p5/LUC), in the presence or absence of 100 nM RU486. 293 cells were selected as recipient cells, because the p5 promoter is known to be highly active in this cell line (29). As expected, cotransfection of p5/LUC with expression vectors for Rep78 and Rep68 (pCMV/Rep78 and pCMV/Rep68, respectively) led to the complete inhibition of luciferase activity (98% repression [Fig. 2A]). The four chimeric proteins Rep78/PR, Rep78int/PR, Rep68/PR, and Rep68int/PR also acted as strong repressors in the absence of hormone treatment (Fig. 2A). Similar results were observed in HeLa cells, in which the p5 promoter had a lower but still detectable activity (reference 39 and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Activity of chimeras derived from wt Rep78 and Rep68. (A) Rep/PR fusions constitutively inhibit p5 promoter activity. 293 cells were transfected with 5 μg of plasmid p5/LUC and 50 ng of the expression plasmids pCMV/Rep78, pCMV/Rep68, pCMV/Rep78/PR, pCMV/Rep78int/PR, pCMV/Rep68/PR, and pCMV/Rep68int/PR (see Materials and Methods). In control experiments, the empty expression vector pcDNAIII was cotransfected with p5/LUC. At 15 h posttransfection, the cells were treated for 36 h or not treated with RU486. The luciferase activity observed in the presence of the different Rep and Rep derivative expression vectors was calculated as the percentage of that (arbitrarily assumed to be 100%) measured in cells transfected with p5/LUC and pcDNAIII. White columns show activity in the absence of RU486 treatment; black columns show activity in the presence of 100 nM RU486. Each column represents the mean and standard deviation for at least three different experiments, performed in duplicate with different plasmid preparations. (B) Constitutive activity of Rep/PR fusions in a rescue-replication assay. Ad-2-infected HeLa cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of the ITR/Hook-Neo plasmid and 10 μg of the expression plasmids pCMV/Rep78 (lane 11), pCMV/Rep68 (lane 12), pCMV/Rep78/PR (lanes 3 and 4), pCMV/Rep78int/PR (lanes 5 and 6), pCMV/Rep68/PR (lanes 7 and 8), or pCMV/Rep68int/PR (lanes 9 and 10). After 15 h, the cells were washed and incubated either with normal medium (−) or with medium containing 100 nM RU486 (+). After 48 h, low-molecular-weight DNA samples were isolated (20), digested with DpnI (62), and analyzed on Southern blots with a 32P-labelled neo-derived probe. The two bands corresponding to rescued monomeric (about 3.7-kb) and dimeric (about 7.5-kb) ITR-flanked cassette are visible. Higher-order multimeric forms were evident after longer exposures (data not shown). In control experiments, cells were transfected only with the ITR/Hook-Neo plasmid (lane 2). Untransfected cells are shown in lane 1. Lane 13 shows results obtained in cells cotransfected with 10 μg of plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo and 10 μg of plasmid pCMV/Rep, which express all four species of Rep (see also Materials and Methods). Molecular sizes are shown in kilobases. The autoradiogram shown is representative of five different experiments which all gave similar results. (C) Ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel which was blotted onto a nylon membrane. Numbering below the lanes is the same as in B.

The four chimeric proteins were further tested in a rescue-replication assay commonly used to monitor the ability of Rep78 and Rep68 to promote, in Ad-infected cells, the excision and replication of an ITR-flanked cassette contained in a cotransfected plasmid (45). The plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo (30), containing the expression cassette for the membrane-bound single-chain antibody (Hook) and for the neomycin resistance genes (neo) cloned between the AAV ITRs, was cotransfected with expression vectors for the four Rep/PR fusions in Ad-2-infected HeLa cells, treated or not treated with RU486. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated 63 h posttransfection (20), digested with DpnI to degrade input plasmid DNA (62), and fractionated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel. Monomeric and dimeric forms of the rescued and replicated ITR-flanked Hook-neo cassette were detected on Southern blots by using a 32P-labelled neo probe: the intensity of the signal was considered to be a measurement of the activity of the various Rep/PR fusions in the assay. The autoradiogram of one such experiment is presented in Fig. 2B: Fig. 2C shows the corresponding agarose gel, which was blotted onto a nylon membrane. No signal was detected in untransfected cells or in cells transfected only with ITR/Hook-neo (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2). In cells transfected with expression vectors for the Rep78/PR, Rep78int/PR, Rep68/PR, and Rep68int/PR chimeras, bands corresponding to rescued monomers and dimers were clearly detected in the absence of RU486 treatment (lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9); their intensities were similar to those monitored in cells transfected with wt Rep78 and Rep68 (lanes 11 and 12) and was not increased following RU486 treatment (lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10). Identical results were obtained with 293 and Hep3B cells (not shown). In conclusion, we found that the four chimeric Rep/PR proteins displayed a constitutive rather than hormone-inducible activity in both the p5 promoter repression and rescue-replication assays. This suggested that the relatively small amount of protein present in the nuclei of untreated cells (Table 1) was not only constitutively active but also sufficient to give a full response in our experimental settings (see also Discussion).

It is known that a constitutively nuclear fusion protein can be rendered hormone responsive by placing the HBD in close contact with the active domains of the heterologous protein (40, 41). We thus decided to generate a new set of fusions in which the distance of the HBD from the potentially regulatable activities of Rep was reduced. To do this, a few Rep68 deletion mutants were constructed to identify the minimal region of Rep retaining wild-type activity and then fuse it with PR891-HBD.

Identification of the minimal region of Rep68 retaining full activity in vitro and in vivo.

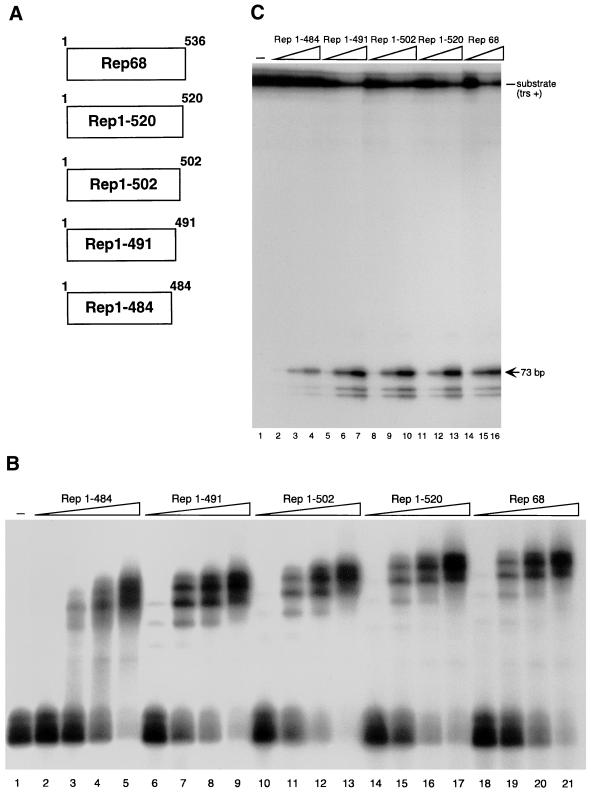

Since the N terminus of Rep68 is required for DNA binding, deletions were generated starting from the carboxy terminus of the protein (37). Four C-terminally truncated Rep68 derivatives were thus constructed, namely, Rep1–520, Rep1–502, Rep1–491, and Rep1–484, which lack the last 17, 35, 46, and 53 C-terminal amino acids, respectively. Their schematic structure is shown in Fig. 3A. No further deletions were constructed, because they have been previously reported to strongly impair DNA binding and endonuclease activity (34, 61, 67).

FIG. 3.

Structure and in vitro activity of Rep C-terminal deletion mutants. (A) Schematic representation of the Rep deletion mutants. Numbers to the right refer to amino acid positions. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay with wt and mutant Rep proteins. Rep68 and the four deletion mutants were translated in vitro, and equivalent amounts of the various proteins (normalized as described in Materials and Methods) were used in dose-dependent DNA binding assays. Reaction mixtures contained 20,000 cpm of 32P-5′-end-labeled AAV ITR and either no protein (lane 1) or increasing concentrations of the various proteins indicated above lanes 2 to 21. (C) Nicking activity of wild-type and mutant Rep proteins. A 20,000-cpm sample of 32P-5′-end-labeled AAV ITR containing a single-stranded trs (trs+ [48]) was incubated with increasing concentrations, normalized as in panel B, of in vitro-translated Rep68, Rep1–484, Rep1–491, Rep1–502, and Rep1–520. A standard endonuclease reaction was carried out (30, 48), and the reaction products were resolved on an 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The positions of the substrate (trs +) and of the released 73-bp fragment are indicated. The two labelled fragments shorter than 73 bp are the result of aberrant nicking sometimes observed when single-stranded trs+ substrates are used in Rep endonuclease assays (30, 48).

The four Rep68 derivatives were first analyzed in vitro. Rep1–520, Rep1–502, Rep1–491, and Rep1–484, as well as Rep68, were produced by in vitro translation and then assayed for their DNA binding and endonuclease activity. As shown in Fig. 3B and C, Rep1–520, Rep1–502, and Rep1–491 bound (Fig. 3B) and cleaved (Fig. 3C) a 5′-end-labelled hairpinned AAV ITR as efficiently as Rep68 did, while Rep1–484 displayed a weaker activity in both assays (Fig. 3B and C).

Immunoblotting analysis demonstrated that all four mutants were expressed at levels comparable to that of Rep68 in HeLa, Hep3B, and 293 cells (results not shown). The major Rep nuclear localization signal (NLS) spans a region between amino acids 485 to 510 which is highly enriched in positively charged residues (Lys and Arg) (21, 51, 66): since three of four deletion mutants lacked at least part of this sequence, we first checked their intracellular distribution. As shown in Table 2, progressive deletions from the C terminus of Rep68 gradually reduced the capacity of the mutants to localize into the nucleus. Rep1–520 behaved like Rep68 (N = 95% [Table 2]), and Rep1–484, which lacked the entire NLS, was found predominantly in the cytoplasm of all scored cells (C = 100% [Table 2]). Rep1–502 and Rep1–491 did not display a clear preferential subcellular compartimentalization but were still capable of localizing into the nuclei (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Intracellular distribution of Rep C-terminal deletion mutants

| Protein | Intracellular localization (%)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | N = C | C | |

| Rep1–520 | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| Rep1–502 | 57 | 42 | 1 |

| Rep1–491 | 16 | 42 | 42 |

| Rep1–484 | 100 | ||

Stained Hep3B cells were classified as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. A total of 600 stained cells, obtained from at least two different experiments, were analyzed for each protein, and the results are expressed as the percentage of cells included in each category.

The in vivo activity of the four mutants was then tested in both the p5 promoter-repression and the rescue-replication assays performed with various cell lines. As summarized in Table 3, Rep1–520, Rep1–502, and Rep1–491 displayed a wt-like activity in both tests. In contrast, Rep1–484 acted as a poor repressor and was totally inactive in the rescue-replication assay, in agreement with its reduced activity in vitro (Fig. 3B and C) and its mainly cytoplasmic distribution (Table 2). Finally, we checked the integration competence of the various Rep68 derivatives by using a recently developed PCR-based integration assay (30). HeLa cells were cotransfected with ITR/Hook-Neo and the various mutants and were then serially passaged for 14 days in the absence of selection. ITR/AAVS1 junctions were then selectively amplified by PCR and revealed by Southern blotting as described in the footnotes to Table 3 (30, 52, 55). As previously reported, under these experimental conditions no signal is detected in cells transfected only with the ITR/Hook-Neo cassette (reference 30 and data not shown). A positive signal, indicative of site-specific integration events at the AAVS1 site, was instead detected in cells in which plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo was cotransfected with the expression vectors for Rep78 or Rep68 and its derivatives Rep1–520, Rep1–502, and Rep1–491 (Table 3). Conversely, no site-specific integration was observed when Rep1–484 was used (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Activity of Rep68 C-terminal deletion mutants in transfected cells

| Protein | Repression of p5/LUC activity (%)a | Rescue-replicationb | Integrationc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rep78 | 98 ± 1 | + | + |

| Rep68 | 98 ± 1 | + | + |

| Rep1–520 | 97 ± 2 | + | + |

| Rep1–502 | 98 ± 1 | + | + |

| Rep1–491 | 95 ± 4 | + | + |

| Rep1–484 | 40 ± 3 | − | − |

Repression of p5/LUC activity was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. 293 or HeLa cells were cotransfected with plasmid p5/LUC and the expression vectors for the various Rep derivatives. Repression was calculated with respect to the luciferase activity observed in extracts from cells transfected with p5/LUC plasmid alone.

Rescue-replication of the Hook-neo cassette in Ad2-infected HeLa, 293, or Hep3B cells was monitored as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. +, detection of a rescue-replicated Hook-Neo cassette in the Hirt supernatant of transfected cells (the intensity of the signal was identical for all the active mutants); −, no replicated cassette could be detected. Similar results were obtained in all three cell lines.

HeLa cells were cotransfected with the expression vectors for the various mutants and plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo and then serially passaged for 14 days in the absence of selection. Genomic DNA was extracted and used as a template for two consecutive rounds of PCR with nested primers specific for the AAV ITRs and the AAVS1 site in human chromosome 19 to selectively amplify the ITR/AAVS1 junctions (30). Amplification products were then detected by Southern blot analysis with an AAVS1-derived probe (30, 52, 55). + and − indicate that AAVS1-positive signals were observed or not, respectively.

In summary, the experiments performed with Rep68 C-terminally deleted mutants demonstrated that Rep1–491 is the shortest variant which retains the capacity to localize into the nuclei, although it does so less efficiently than wt protein, while still displaying full in vitro and in vivo activity, including site-specific integration. However, Rep1–484 binds and nicks DNA with reduced efficiency in vitro and is poorly active in vivo, also because it lacks a functional NLS.

Construction of Rep1–484/Pn and Rep1–491/P.

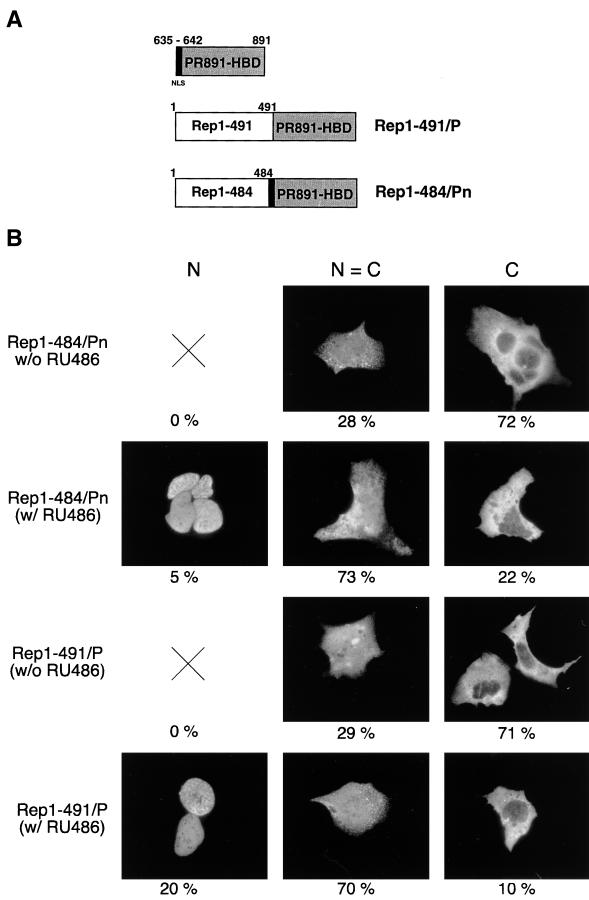

In an attempt to generate a hormone-dependent Rep protein, we constructed two new Rep/PR hybrid proteins (Fig. 4A). In the first, Rep1–491/P, the PR891-HBD was fused to the C terminus of Rep1–491. The second chimera, named Rep1–484/Pn, was generated by C-terminally fusing Rep1–484 to a slightly larger segment of the human PR (aa 635 to 891), which includes the major NLS (aa 638 to 642) of the human PR (16, 69); this motif was expected to facilitate the intranuclear localization of the fusion.

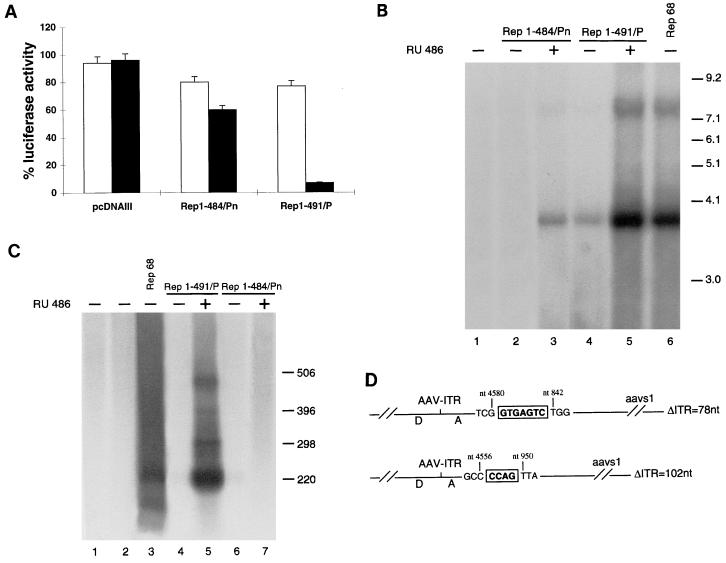

FIG. 4.

Structure and intracellular distribution of chimeras made up of Rep68 C-terminal deletion mutants fused with PR891-HBD. (A) Diagram of Rep1–491/P and Rep1–484/Pn chimeric constructs. The region of the human PR spanning from aa 635 to 891 is shown at the top of the figure: the NLS (aa 635 to 642), which is maintained in the Rep1–484/Pn fusion but absent in the Rep1–491/P chimera, is indicated in black. Numbers above the hybrid proteins refer to the amino acid position in the parental Rep protein (see also the legend to Fig. 1A). (B) RU486 affects the intracellular distribution of Rep1–491/P and Rep1–484/Pn. Hep3B cells were transfected with 10 μg of the expression vectors pCMV/Rep1–491/P and pCMV/Rep1–484/Pn and treated with 100 nM RU486 or left untreated. The cells were stained with an anti-Rep polyclonal serum and classified as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. At least 1,000 stained cells, obtained from a minimum of three experiments, were scored for each fusion. The numbers below the micrographs represent the percentage of cells falling into each category.

Rep1–484/Pn and Rep1–491/P were cloned into eukaryotic expression vectors; their expression levels in transfected HeLa, 293, and Hep3B cells were comparable to that of wt Rep68 (results not shown). Immunofluorescence experiments revealed that in untreated cells, both fusions were on average predominantly cytoplasmic or evenly distributed between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 4B). RU486 modestly increased the intranuclear accumulation of Rep1–484/Pn, whereas a more pronounced effect was observed for Rep1–491 (Fig. 4B). In this last case, upon hormone treatment there was a substantial increase in the number of cells stained exclusively in the nuclei (N = 20% [Fig. 4B]) and a drastic reduction in the number of cells in which Rep1–491/P was localized only in the cytoplasm (C = 71 and 10% in the absence and presence of RU486, respectively [Fig. 4B]). Similar results were obtained with Hep3B (Fig. 4B), HeLa, and 293 (results not shown) cells.

Ligand-dependent activity of Rep1–484/Pn and Rep1–491/P.

The two fusions were first tested for their capability to down-regulate the p5 promoter activity in 293 cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, both fusions displayed low repressing activity in the absence of the hormone (about 20% repression [Fig. 5A]): however, following RU486 treatment, Rep1–491/P strongly inhibited p5/LUC activity (94% repression [Fig. 5A]). The repressing activity of Rep1–484/Pn was also stimulated by the steroid but to a more limited extent (45% repression [Fig. 5A]). Similar results were obtained with HeLa cells (not shown).

FIG. 5.

Hormone-dependent activity of Rep1–491/P and Rep1–484. (A) Rep1–491/P and Rep1–484/Pn repress the p5 promoter in a ligand-dependent manner. 293 cells were transfected with 5 μg of plasmid p5/LUC and 50 ng of the expression plasmids pCMV/Rep68, pCMV/Rep1–491/P, and pCMV/Rep1–484/Pn. Luciferase activity was calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. White and black columns represent the activities measured in the absence and in the presence of 100 nM RU486, respectively. Each column represents the mean and standard deviation for at least three different experiments, performed in duplicate with different plasmid preparations. (B) RU486 stimulates the activity of Rep1–491/P and Rep1–484/Pn in a rescue-replication assay. Ad2-infected HeLa cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of the ITR/Hook-Neo plasmid and 10 μg of the expression plasmid pCMV/Rep68 (lane 6), pCMV/Rep1–491/P (lanes 4 and 5), or pCMV/Rep1–484/Pn (lanes 2 and 3). Cell treatment and analysis of low-molecular-weight DNA was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2B. Monomeric (about 3.7-kb) and dimeric (about 7.5-kb) forms of the rescued ITR-flanked cassette are visible: higher-order multimeric forms were detectable after longer exposures (data not shown). In control experiments, the ITR/Hook-Neo plasmid was cotransfected with the empty expression vector pcDNAIII (lane 1). Molecular sizes are shown in kilobases. The autoradiogram shown is representative of four different experiments which all gave similar results. (C) RU486-dependent site-specific integration mediated by Rep1–491/P. HeLa cells were transfected with 10 μg of plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo alone (lane 2) or together with 10 μg of the expression vector pCMV/Rep68 (lane 3), pCMV/Rep1–491/P (lanes 4 and 5), or pCMV/Rep1–484/Pn (lanes 6 and 7). At 15 h later, the cells were washed and incubated for 24 h with 100 nM RU486 or left untreated. ITR/AAVS1 junctions were amplified from the genomic DNA extracted from cells subcultured for 14 days and detected with an AAVS1-derived probe as described in the footnote to Table 3. Lane 1 contains untransfected cells. Molecular sizes are shown in base pairs. (D) Sequence analysis of ITR/AAVS1 junctions. The letters D and A refer to the accepted nomenclature for AAV/ITR sequences (4, 30, 46). The numbers above the diagrams refer to the last identifiable viral and AAVS1 nucleotides. Insertions between AAV/ITR and AAVS1 are boxed. AAVS1 breakpoints are based on published AAVS1 sequence (27). Nucleotide numbering of the AAV/ITR is relative to the right end of the AAV genome (51).

Rep1–484/Pn also displayed hormone dependence in the rescue-replication assay: in fact, rescue-replication of the ITR-flanked Hook-neo cassette was seen in Ad2-infected HeLa cells only upon RU486 treatment (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 2 and 3). However, the maximal activity was lower than that of wt Rep68 (compare lanes 3 and 6). Also, Rep1–491/P was at least partially hormone dependent in this assay: in fact, basal activity was detectable in the absence of RU486 (lane 4), but the activity was strongly enhanced by steroid treatment (compare lanes 4 and lane 5). The same results were observed with 293 and Hep3B cells (not shown).

The capability of Rep1–484/Pn and Rep1–491/P to mediate site-specific integration was then examined by using the PCR-based assay described above. As shown in Fig. 5C, no site-specific integration could be monitored in cells transfected with Rep1–484/Pn (Fig. 5C, lanes 6 and 7). In contrast, Rep1–491/P clearly triggered integration at AAVS1 in the presence of RU486 (lanes 4 and 5). It is worth noting that in this assay, the full-length Rep proteins fused with PR891-HBD also displayed a constitutive activity (data not shown). The heterogeneous size of the amplified AAVS1-positive bands is in agreement with the fact that Rep-mediated integration occurs in a region spanning more than 500 bp of human chromosome 19 (30, 44, 46, 65). To further verify that positive signals are indicative of true integration events, we cloned two junctions amplified from hormone-treated cells transfected with Rep1–491/P. Their sequences, shown in Fig. 5D, demonstrate that integration has occurred at nucleotides 842 and at 950 of AAVS1. In both cases, a complete ITR was not found, in line with all the ITR/AAVS1 junctions analyzed so far (30, 38, 42, 43, 46, 65).

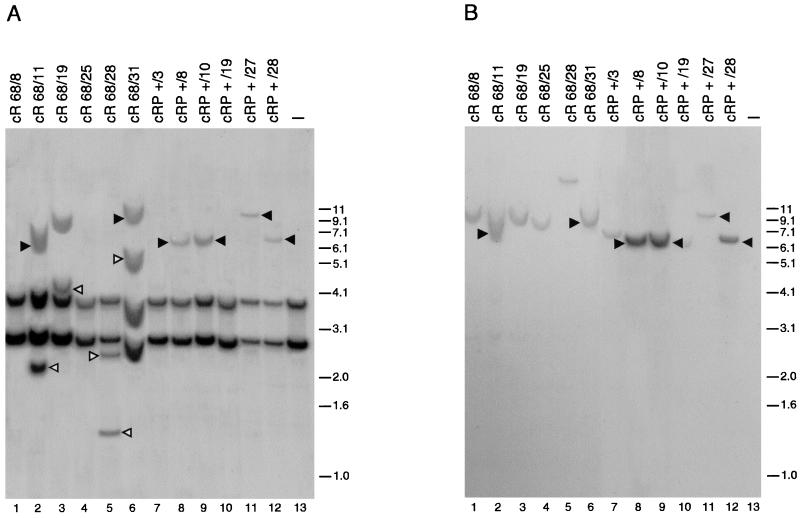

Rep1–491/P mediates site-specific integration in the absence of chromosomal rearrangements.

To better characterize the integration efficacy of Rep1–491/P, we performed Southern blot analysis of individual clones derived from HeLa cells cotransfected with the expression vector for Rep1–491/P and plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo. At 15 h posttransfection, the cells were incubated for 24 h with 100 nM RU486 and then grown in the absence of steroid treatment under selection with 700 μg of G418 per ml for 3 weeks. Genomic DNA was then extracted from individual clones and digested with the restriction enzyme BamHI, which has no recognition site in the ITR-flanked Hook-neo cassette and in the region of AAVS1 in which the great majority of integration events take place (27, 30, 46, 65). Digested DNA was then subjected to Southern blot analysis with AAVS1-derived and neo-derived probes. Site-specific integration was assigned to clones displaying an AAVS1 hybridizing band which was upshifted with respect to the bands observed in untransfected cells and which also cohybridized with the neo probe (30).

According to this criterion, site-specific integration was observed in 7 of 28 clones (25% frequency of site-specific integration) derived from cells cotransfected with ITR/Hook-Neo and the expression vector for Rep68. This integration efficiency is in line with previously published results (30). Also, Rep1–491/P was able to mediate integration at the AAVS1 site, and the frequency of site-specific integration was higher in the presence of RU486 treatment (25%; 7 positive clones of 28 analyzed) than in its absence (3.2%; 1 positive clone of 31), confirming that the activity of the fusion was in large part under hormonal control. Of the clones derived from Rep68-transfected cells, 40% showed additional AAVS1 bands not cohybridizing with the neo probe. As illustrated in Fig. 6, where the integration pattern of some representative clones is shown, these neo-negative bands were evident both in clones scored as positive for site-specific integration (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 6) and in those scored as negative (lanes 3 and 5). Interestingly, AAVS1-positive and neo-negative bands were not observed in any of the clones derived from cells transfected with Rep1–491/P and treated or not treated with RU486 (lanes 7 to 12 and data not shown). These results suggest that short-term (24-h) treatment with RU486 enables Rep1–491/P to promote site-specific integration as efficiently as wt Rep68 but with much less propensity to generate additional and undesired rearrangements at the AAVS1 site.

FIG. 6.

Southern blot analysis of HeLa neo-resistant clones derived from cells cotransfected with plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo and expression vectors for either wt Rep68 or Rep1–491/P. Transfection and selection of Neor clones were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Genomic DNA of isolated clones was digested with BamHI and blotted onto a nylon membrane. (A) Hybridization to an AAVS1-specific probe. (B) The same membrane after rehybridization to a neo-specific probe. Solid triangles mark upshifted bands which cohybridize with both probes and are therefore indicative of site-specific integration (panels A and B, lanes 2, 6, 8, 9, 11, and 12). Open triangles show nonspecific rearrangements (AAVS1-positive/neo-negative bands) observed in clones derived from cells cotransfected with wt Rep68 (panel A, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). cR68, clones derived from cells transfected with wt Rep68 (lanes 1 to 6); cRP +, clones derived from cells transfected with Rep1–491/P and treated for 12 h with 100 nM RU486 (lanes 7 to 12). Lane 13 contains untransfected cells. Molecular sizes are shown in kilobases.

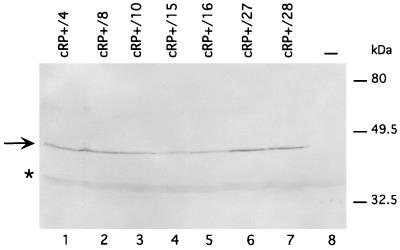

We finally checked whether the stable transformants scored as positive for site-specific integration also expressed the other gene, Hook, contained between the AAV ITRs in plasmid ITR/Hook-Neo. As shown in Fig. 7, Western blot analysis revealed that all seven stable transformants derived from cells transfected with Rep1–491/P also expressed the Hook gene protein product (sFv/PDGFR) (6). Conversely, the Hook gene protein product was detectable in only one of the seven AAVS1 integrants isolated from cells cotransfected with wt Rep68 (results not shown). This finding further suggests that Rep1–491/P promotes a more precise integration of an ITR-flanked cassette at the AAVS1 site.

FIG. 7.

Hook gene expression in site-specific integrants derived from HeLa cells cotransfected with ITR/Hook-Neo and Rep1–491/P and treated with RU486. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from cRP+ clones and run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Fractionated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was probed with anti-myc epitope tag antibody (13) as described in Materials and Methods. The arrow marks the band, of the expected size, corresponding to the single-chain antibody (sFv/PDGFR) encoded by the Hook gene (6). Asterisks indicate nonspecific product recognized by the anti-myc monoclonal antibody 9E10.2 in untransfected cells. Lane 8 contains untransfected HeLa cells.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we describe the construction and characterization of a ligand-dependent AAV Rep protein. Among the two ligand-dependent Rep/PR fusions generated, Rep1–491/P has the most interesting properties in that in various assays it displays a low basal activity which is highly stimulated by RU486 and, more importantly, promotes integration into the AAVS1 site in a ligand-dependent manner. The partial discrepancy in the results that emerged from the PCR-based integration assay (no junctions amplified from pooled and unselected cells in the absence of RU486 treatment [Fig. 5C, lane 4]) and the Southern blot analysis of individual selected clones (site-specific integration detected in 1 of 31 clones derived from untreated cells) might simply reflect different sensitivities of the two assays. Nevertheless, further work is required to clarify whether selection can increase the integration frequency even in the absence of hormone treatment.

Rep1–491/P has several advantages over wt Rep78 or Rep68 for gene therapy purposes. This chimera triggers site-specific integration in the presence of RU486 as efficiently as wt Rep68 does, and it does so without generating major unwanted rearrangements at the AAVS1 site, thus overcoming one of the major limitations of the AAV-based integration strategy (31). It is not yet clear how rearrangements are generated and whether they occur at the same time as or after the initial integration event (33), but our results with Rep1–491/P indicate that it is possible to prevent or at least reduce them by simply establishing a time limit to Rep activity in target cells. These results tempt us to speculate that rearrangements at AAVS1 are not a direct consequence of the integration process itself but, rather, might be ascribed to unrestrained activity of Rep at the integration locus. This is further corroborated by the recent report that AAVS1 rearrangements are also detected in cells transfected with a plasmid containing the entire rep ORF only and no ITR-flanked sequences (52; S. Lamartina and C. Toniatti, unpublished results).

We might hence envision the following scenario: after the initial integration event, rearrangements occur when constitutively active Rep78/68 binds and nicks its target sequence present not only at AAVS1 but also in the ITRs flanking the integrated transgene. This leads to partial replication, rearrangements, and, possibly, translocation of the region (2, 31, 32, 52). In relation to this last point, it is of interest that the Rep78 or Rep68 nicking sites located on the ITRs are maintained in all the AAVS1-ITR junctions sequenced so far and that in the majority of cases, the ITRs flanking the integrated DNA still retain their Rep binding site (30, 38, 42, 43, 46, 65). In contrast, Rep1–491/P is capable of triggering site-specific integration during the initial 24 h of RU486 treatment of transfected cells; following withdrawal of the hormone, it no longer binds and nicks DNA, thus reducing the instability of the region.

The two genes, Hook and neo, contained between the AAV ITRs were both expressed in all site-specific integrants derived from hormone-treated cells transfected with Rep1–491/P (Fig. 7). In addition, in six of seven clones the size of the single upshifted AAVS1 band are about 6.5 kb long (Fig. 6A, lanes 8, 9, and 12, and data not shown), a size which is consistent with the integration of one single copy of the full-length ITR/Hook-Neo cassette (3.7 kb). These findings are in striking contrast to what was observed, in this and previous studies, in site-specific stable integrants derived from cells cotransfected with wt Rep68 (Fig. 6A) (2, 47, 52). We should mention that integration of the Hook gene at AAVS1 in our selected clones could not be unequivocally demonstrated by Southern blotting, because the Hook-derived probe reveals a complex pattern of multiple bands on genomic DNA (Hook codes for a single-chain antibody [6]). The use of different ITR-flanked cassettes will therefore be required for a careful study of the fine structure of the integrated DNA. This will be the object of future work to clearly establish whether Rep1–491/P not only reduces nonspecific rearrangements but also can promote a more precise integration of the ITR-flanked cassette.

Shorter variants of Rep (Rep1–491 and Rep1–484) fused with PR891-HBD proved hormone dependent, while fusions with full-length Rep78 or Rep68 did not. The observation that tighter hormonal control can be achieved by reducing the distance between HBD and the active site of the heterologous moiety is not unprecedented (35, 40, 50). Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms by which heterologous proteins fused with HBDs are regulated by the cognate ligand have not yet been elucidated and are likely to vary according to the particular steroid receptor used (41, 54). A point to note is that in our case, the more stringent control achieved with the shorter fusions did not parallel a concomitant tighter regulation of their subcellular distribution. In fact, both fusions with Rep deletions and fusions with full-length Rep78/68 were predominantly cytoplasmic, presumably complexed with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) (49, 54), in the absence of RU486 and were localized into nuclei following hormone treatment. It is conceivable that the constitutive activity of full-length Rep proteins fused with PR891-HBD results from the highly sensitive assays we used to monitor Rep activity in transfected cells. Furthermore, immunofluorescence experiments gave a static representation of what is probably a dynamic situation in which, similarly to sex steroids such as progesterone, estrogen, and glucocorticoid receptors (54), a specific Rep/PR fusion continuously shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm with, at any given time, a major fraction of the protein being localized in one of the two compartments (28, 54). Nevertheless, our results suggest that regulation of intranuclear localization is probably neither the only nor the most important mechanism responsible for the ligand-dependent activity of Rep1–491/P and Rep1–484/Pn. Although we have no data to support this hypothesis, it is tempting to speculate that the major difference between full-length Rep/PR and deleted Rep/PR fusions is that only the latter require RU486 to assume the proper conformation, thus acquiring full activity and/or the ability to interact with specific intracellular proteins. In relation to this point, it has to be remembered that the progesterone receptor is predominantly nuclear, regardless of the presence of its ligand, but interacts with appropriate cofactors and stimulates transcription only in the presence of the hormone (28, 36, 64).

Rep78 and Rep68 repress the AAV p5 promoter: this repression is postulated to be mediated in part by direct binding to the p5 RBS and in part by interaction with as yet unidentified cellular factors that might facilitate repression (29, 39). Rep1–491/P efficiently down-regulated the p5 promoter in a hormone-dependent manner, although background activity (20% repression [Fig. 5A]) was also observed in the absence of RU486 treatment. It is worth noting that p5 promoter repression is an extremely sensitive test, as demonstrated by the behavior of mutant Rep1–484, which is unable to promote rescue-replication and to drive integration at AAVS1 but is still active in this assay (21). Further investigation is required to assess the activity of Rep1–491/P on heterologous promoters, but it is reasonable to expect that the chimeric protein, which is localized mainly in the cytoplasm in the absence of hormone treatment, should prove less capable than Rep78/68 of interfering with the expression of cellular genes and, ultimately, with cellular physiology. This hypothesis is further supported by the evidence that when transfected in 293 cells, Rep78 reduced their cloning efficiency by 80% while Rep1–491/P had only a modest effect in the absence of RU486 treatment (D. Rinaudo and C. Toniatti, unpublished results). These results complement previous reports indicating that the growth rate of 293 cells stably expressing an inducible Rep is altered and reduced in the presence of the inducer (68).

An interesting property of Rep1–491/P is that it is not responsive to endogenous steroids such as progesterone, thus rendering the use of this protein feasible not only for ex vivo but also for in vivo gene therapy. It has been recently reported that Rep-mediated site-specific integration at AAVS1 takes place in transgenic rodents (mice and rats) carrying the human AAVS1 site (43), and it would be of interest to test the integration competence of Rep1–491/P in this animal model. The ideal vector for in vivo utilization of Rep1–491/P and, in general, of the AAV integration machinery, has yet to be constructed, but one possible approach is that of introducing both an ITR-flanked transgene and a Rep1–491/P expression cassette into an Ad vector. This Ad/AAV chimeric virus would borrow properties from both Ad vectors (i.e., infectivity, high titer, and large capacity) and AAV (integration competence). We have recently constructed a helper-dependent Ad vector containing the Rep78 gene and demonstrated that this chimeric Ad/AAV vector is indeed capable of triggering site-specific integration of a codelivered ITR-flanked cassette in cultured cells (42). A further step in this direction will be to use the ligand-dependent Rep1–491/P for the generation of additional Ad/AAV hybrid vectors to be tested in AAVS1 transgenic rodents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to B. O'Malley and S. Tsai for PR891-HBd cDNA. We also thank Janet Clench for editing the manuscript and M. Emili for contributing graphical work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balagué C, Kalla M, Zhang W-W. Adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein and terminal repeats enhance integration of DNA sequences into the cellular genome. J Virol. 1997;71:3299–3306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3299-3306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baulieu E E. RU486: an antiprogestin steroid with contragestive activity in women. In: Baulieu E E, Segal J, editors. The antiprogestin steroid RU486 and human fertility control. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berns K I, Linden R M. The cryptic life stile of adeno-associated virus. Bioessays. 1995;17:237–245. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadepond F, Ulmann A, Baulieu E-E. RU486 (mifepristone): mechanisms of action and clinical use. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:129–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesnut J D, Baytan A R, Russell M, Chang M-P, Bernard A, Maxwell I H, Hoeffler J P. Selective isolation of transiently transfected cells from a mammalian cell population with vectors expressing a membrane anchored single-chain antibody. J Immunol Methods. 1996;193:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiorini J A, Wiener S M, Owens R A, Kyöstiö S R M, Kotin R M, Safer B. Sequence requirements for stable binding and function of Rep68 on the adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:7448–7457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7448-7457.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiorini J A, Yang L, Kotin R M, Safer B. Determination of adeno-associated virus Rep68 and Rep78 binding sites by random sequence oligonucleotide selection. J Virol. 1995;69:7334–7338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7334-7338.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crystal R G. Transfer of genes to humans: early lessons and obstacles to success. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:404–410. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunliffe V, Thatcher D, Craig R. Innovative approach to gene therapy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:709–713. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis M D, Wonderling R S, Walker S L, Owens R A. Analysis of the effects of charge cluster mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein in vitro. J Virol. 1999;73:2084–2093. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2084-2093.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Pasquale G, Stacey S N. Adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein interacts with protein kinase A and its homologue PRKX and inhibits CREB-dependent transcriptional activation. J Virol. 1998;72:7916–7925. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7916-7925.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evan G I, Lewis G K. Isolation of monolonal antibodies specific for c-myc proto-oncogene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3610–3616. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flotte T R, Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1995;2:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus is directed by a cellular DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10039–10043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guiochon-Mantel A, Loosfelt H, Lescop P, Sar S, Atger M, Perrot-Applanat M, Milgrom E. Mechanisms of nuclear localization of the progesterone receptor: evidence for interaction between monomers. Cell. 1989;57:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heilbronn R, Bürkle A, Stephan S, zur Hausen H. The adeno-associated virus rep gene suppresses herpes simplex virus-induced DNA amplification. J Virol. 1990;64:3012–3018. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3012-3018.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermonat P L. Inhibition of H-ras expression by the adeno-associated virus Rep78 transformation suppressor gene product. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3373–3377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermonat P L. Down-regulation of the human c-fos and c-myc proto oncogene promoters by adeno-associated virus Rep78. Cancer Lett. 1994;81:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hörer M, Weger S, Butz K, Hoppe-Seyler F, Geisen C, Kleinschmidt J A. Mutational analysis of adeno-associated virus Rep protein-mediated inhibition of heterologous and homologous promoters. J Virol. 1995;69:5485–5496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5485-5496.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Im D-S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin-binding protein Rep68 is an ATP dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im D-S, Muzyczka N. Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep68, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J Virol. 1992;66:1119–1128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1119-1128.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearns W G, Afione S A, Fulmer S B, Pang M G, Erikson D, Egan M, Landrum M J, Flotte T R, Cutting G R. Recombinant adeno-associated (AAV-CTFR) vectors do not integrate in a site-specific fashion in an immortalized epithelial cell line. Gene Ther. 1996;3:748–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellendonk C, Tronche F, Monaghan A-P, Angrand P-O, Stewart F, Schütz G. Regulation of Cre recombinase activity by the synthetic steroid RU486. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1404–1414. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotin R M, Siniscalco M, Samulski R J, Zhu X D, Hunter L, Laughlin C A, Laughlin S M, Muzyczka N, Rocchi M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2211–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotin R M, Linden R M, Berns K I. Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous recombination. EMBO J. 1992;11:5071–5078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunar Tyagi R, Amazit L, Lescop P, Milgrom E, Guiochon-Mantel A. Mechanisms of progesterone receptor export from nuclei: role of nuclear localization signa, nuclear export signal, and Ran guanosine triphosphate. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1684–1685. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.11.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyöstiö S R M, Wonderling R S, Owens R. Negative regulation of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) P5 promoter involves both the P5 Rep binding site and the consensus ATP-binding motif of the AAV Rep68 protein. J Virol. 1995;69:6787–6796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6787-6796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamartina S, Roscilli G, Rinaudo D, Delmastro P, Toniatti C. Lipofection of purified adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein: toward a chromosome targeting nonviral particle. J Virol. 1998;72:7653–7658. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7653-7658.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linden R M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus: a basis for a potential gene-therapy vector. Gene Ther. 1997;4:4–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linden R M, Ward P, Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11288–11294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarty D M, Ni T H, Muzyczka N. Analysis of mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep protein in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:4050–4057. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4050-4057.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nichols M, Rientjes J M J, Logie C, Stewart A F. FLP recombinase/estrogen receptor fusion proteins require the receptor D domain for responsiveness to antagonists, but not agonists. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:950–961. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.7.9944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oñate S A, Tsai S Y, Tsai M-J, O'Malley B W. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Kyöstio S R M, Carter B J. Identification of a DNA-binding domain in the amino terminus of adeno-associated virus Rep proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:997–1005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.997-1005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palombo F, Monciotti A, Recchia A, Cortese R, Ciliberto G, La Monica N. Site-specific integration in mammalian cells mediated by a new hybrid baculovirus–adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol. 1998;72:5025–5034. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5025-5034.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira D J, McCarty D M, Muzyczka N. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein acts as both a repressor and an activator to regulate AAV transcription during a productive infection. J Virol. 1997;71:1079–1088. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1079-1088.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picard D, Salser S J, Yamamoto K R. A movable and regulable inactivation function within the steroid binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1988;54:1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picard D. Steroid-binding domains for regulating the functions of heterologous proteins in cis. Trends Cell Biol. 1993;3:278–280. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Recchia A, Parks R J, Lamartina S, Toniatti C, Pieroni L, Palombo F, Ciliberto G, Graham F L, Cortese R, La Monica N, Colloca S. Site-specific integration mediated by a hybrid adenovirus/adenoassociated virus vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2615–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzuto G, Gorgoni B, Cappelletti M, Lazzaro D, Gloaguen I, Poli V, Sgura A, Cimini D, Ciliberto G, Cortese R, Fattori E, La Monica N. Development of animal models for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. J Virol. 1999;73:2517–2526. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2517-2526.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samulski R J. Adeno-associated virus: integration at a specific chromosomal locus. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:74–80. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samulski R J, Chang L S, Shenk T. A recombinant plasmid from which an infectious adeno-associated virus genome can be excised in vitro and its use to study in vitro replication. J Virol. 1987;61:3096–3101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3096-3101.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samulski R J, Zhu X, Xiao X, Brook J D, Housman D E, Epstein N, Hunter L A. Targeted integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) into human chromosome 19. EMBO J. 1991;10:3941–3950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04964.x. . (Erratum, 11:1228, 1992.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shelling A N, Smith M G. Targeted integration of transfected and infected adeno-associated virus vectors containing the neomycine resistance gene. Gene Ther. 1994;1:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snyder R O, Im D-S, Ni T, Xiao X, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. Features of the adeno-associated virus origin involved in substrate recognition by the viral Rep protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6096-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith D F. Dynamics of heat shock protein 90-progesterone receptor binding and the disactivation loop model for steroid receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1418–1429. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.11.7906860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spitkovsky D, Steiner P, Lukas J, Lees E, Pagano M, Schultze A, Joswig S, Piccard D, Tommasino M, Eilers M, Jansen-Dürr P. Modulation of cyclin gene expression by adenovirus E1A in a cell line with E1A-dependent conditional proliferation. 1994. J Virol. 1994;68:2206–2214. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2206-2214.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srivastava A, Lusby E W, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Surosky R T, Urabe M, Godwin S G, McQuiston S A, Kurtzman G J, Ozawa K, Natsoulis G. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins target DNA sequences to a unique locus in the human genome. J Virol. 1997;71:7951–7959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7951-7959.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Triezenberg S J, Kingsbury R C, McKnight S L. Functional dissection of VP16, the trans-activator of herpes simplex virus immediate early gene expression. Genes Dev. 1998;2:718–729. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai M-J, O'Malley B W. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urabe M, Hasumi Y, Kume A, Surosky R T, Kurtzman G J, Tobita K, Ozawa K. Charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the N-terminal half of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep78 protein. J Virol. 1999;73:2682–2693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2682-2693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urcelay E, Ward P, Wiener S M, Safer B, Kotin R M. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2038–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2038-2046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vegeto E, Allan G F, Schrader W T, Tsai M-J, McDonnell D P, O'Malley B W. The mechanism of RU486 antagonism is dependent on the conformation of the carboxy-terminal tail of the human progesterone receptor. Cell. 1992;69:703–713. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker S L, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein: identification of critical residues necessary for site-specific endonuclease activity. J Virol. 1997;71:2722–2730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2722-2730.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, O'Malley B W, Jr, Tsai S Y, O'Malley B W. A regulatory system for use in gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8180–8184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Carter B, Owens R A. Interaction of wild-type and mutant adeno-associated virus (AAV) rep proteins on AAV hairpin DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2440–2448. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2440-2448.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wobbe C R, Dean F, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. In vitro replication of duplex circular DNA containing the simian virus 40 DNA origin site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5710–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]