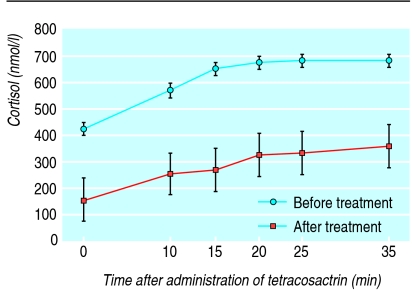

Editor—We agree with Findlay et al that the few case reports of Cushing’s syndrome due to nasal betamethasone drops in children may represent the tip of the iceberg.1 With colleagues we have performed a prospective study in nine adults with nasal polyposis treated with betamethasone drops for six weeks; we assessed the hypothalamopituitary-adrenal axis using a low dose (1 μg) tetracosactrin stimulation test, which may detect more subtle impairment of endogenous cortisol production than the standard test (250 μg).2 We found that all patients had significantly depressed cortisol concentrations when tetracosactrin was given after betamethasone treatment (figure; P<0.0001, analysis of variance for repeated measures).3

Gallagher and Mackay have suggested that in many cases patients tend to overcomply with treatment with nasal drops owing largely to difficulties in using the droplet dispenser.4 The perceived benefit of betamethasone over other topical nasal steroids is that its intranasal distribution is superior (because it is in drop form) to that achieved with aqueous sprays.5

We endorse the view that in rhinological disease betamethasone should be regarded as a systemic corticosteroid and caution should be exercised.

Figure.

Result of low dose tetracosactrin stimulation test before and after six weeks’ treatment with betamethasone nose drops

References

- 1.Findlay CA, MacDonald JF, Geddes N, Donaldson MDC. Childhood Cushing’s syndrome induced by betamethasone nose drops, and repeat prescriptions. BMJ. 1998;317:739–740. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7160.739. . (12 September.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, Rosner I, Shen-Orr Z, Adawi F, et al. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72:773–778. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-4-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gazis AG, Homer JJ, Page S, Jones NS. The effect of topical nasal betamethasone drops for nasal polyposis on adrenal function. Clin Otol. 1998;23:280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher G, Mackay I. Doctors and drops. BMJ. 1991;303:761. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6805.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy JG, Lee SW, Wilson CG. Intranasal drug delivery by spray and drops. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1985;37:294–297. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1985.tb05069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]