Abstract

Introduction:

Food allergic reactions can be severe and potentially life-threatening and the underlying immunological processes that contribute to the severity of reactions are poorly understood. The aim of this study is to integrate bulk RNA-sequencing of human and mouse peripheral blood mononuclear cells during food allergic reactions and in vivo mouse models of food allergy to identify dysregulated immunological processes associated with severe food allergic reactions.

Methods:

Bulk transcriptomics of whole blood from human and mouse following food allergic reactions combined with integrative differential expressed gene bivariate and module eigengene network analyses to identify the whole blood transcriptome associated with food allergy severity. In vivo validation immune cell and gene expression in mice following IgE-mediated reaction.

Results:

Bulk transcriptomics of whole blood from mice with different severity of food allergy identified gene ontology (GO) biological processes associated with innate and inflammatory immune responses, dysregulation of MAPK and NFkB signaling and identified 429 genes that correlated with reaction severity. Utilizing two independent human cohorts, we identified 335 genes that correlated with severity of peanut-induced food allergic reactions. Mapping mouse food allergy severity transcriptome onto the human transcriptome revealed 11 genes significantly dysregulated and correlated with severity. Analyses of whole blood from mice undergoing an IgE-mediated reaction revealed a rapid change in blood leukocytes particularly inflammatory monocytes (Ly6Chi Ly6G−) and neutrophils that was associated with changes in CLEC4E, CD218A and GPR27 surface expression.

Conclusions:

Collectively, IgE-mediated food allergy severity is associated with a rapid innate inflammatory response associated with acute cellular stress processes and dysregulation of peripheral blood inflammatory myeloid cell frequencies.

Keywords: food allergy, monocytes, neutrophils, IgE

Introduction

Severe food allergy-related reactions, termed food-triggered anaphylaxis, are serious life threatening reactions responsible for 30,000-120,000 emergency department visits, 2,000 - 3000 hospitalizations, and approximately 150 deaths per year in the United States 1,2. The onset of symptoms are variable, occurring within seconds to a few hours following exposure to the casual dietary allergen, and often affects multiple organ systems including gastrointestinal (GI), cutaneous, respiratory and cardiovascular 3. The recommended treatment for these food allergies is strict food avoidance and ready access to self-injectable epinephrine 4; however, accidental ingestion is unfortunately common 5,6.

The unpredictable nature and the daily risk for potential life-threatening reaction causes food allergy suffers and caregivers to experience significantly impaired quality of life 7–10. The poor quality of life combined with limited therapeutic options have led to intensive focus on the development and usage of approaches such as skin prick test (SPT), food specific IgE levels and basophil activation test (BAT) to accurately predict food allergy diagnosis, the likelihood of having a reaction and the severity of food allergic reactions. However, the utility of these approaches to predict food threshold dose and food reaction severity are somewhat conflicting 11–15. Furthermore, while there has been significant advancement in the understanding of the immunological processes that underlie food sensitization and effector phase of IgE-FcεRI-dependent mast cell (MC) degranulation the contribution of immunological pathways and processes to the severity of a food allergic reaction are poorly understood.

We have previously described a passive model of IgE-mediated oral antigen-induced food reaction whereby intestinal IL-9 transgenic mice are administered antigen specific IgE (anti-TNP-IgE) and subsequently challenged with a single oral dose of antigen [TNP-ovalbumin (OVA)] inducing an acute allergic reaction characterized by gastrointestinal (GI) and systemic symptoms 16. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that severity of the IgE-mediated reaction is dependent on IL-4-priming of the vascular endothelial compartment 17. Herein, we have utilized this experimental model system to induce mild to moderate and severe IgE-mediated food reactions in mice and performed mouse bulk transcriptomic analyses of whole blood during a food allergic reaction to identify key genes and pathways associated with progression of disease severity. We have mapped the differentially expressed genes that correlated with severity onto human bulk transcriptomic analyses of whole blood during a food allergic reaction to identify a common core innate immune program defined by inflammatory myeloid cell populations identifying an association between rapid innate immune activation and cellular stress and apoptosis response and development of severe food-induced reactions in mouse and humans.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Intestinal IL-9 transgenic (iIL9Tg) mice were generated as previously described18. Six-eight-weeks-old, age- and weight-matched littermates were used in all experiments. The mice were handled under an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols at University of Cincinnati and Michigan animal facility.

Mouse models of anaphylaxis:

For passive oral antigen-induced anaphylaxis, iIL9Tg mice, were sensitized and challenged as previously described17. Briefly, mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with 10 μg of anti-TNP-IgE (200 μL of saline) with or without IL-4C (recombinant, IL-4–neutralizing, anti–IL-4 monoclonal antibody [mAb] complex, 1:5 weight) (anti–IL-4 mAb, clone BVD4-1D11.2). Twenty-four hours later, mice were held in the supine position and orally gavaged with 250 μL of TNP-Ovalbumin (OVA; 50 mg) in saline. Before the intragastric (i.g.) challenge, mice were deprived of food for 5-6 hours. Challenges were performed with i.g. feeding needles (01-290-2B; Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, PA). For passive anaphylaxis, iIL9Tg mice were injected i.v. with 10 μg of anti-IgE (EM-95) in 100μl saline and anaphylaxis assessment performed17. Control mice were defined as mice that received anti-TNP IgE and subsequently received saline via i.g. challenge and did not experience shock (hypothermia) response 30 minutes following challenge (FC). Mice that experienced a mild to moderate reaction received anti-TNP IgE and subsequently received i.g. OVA-TNP and experienced a 1.5 - 1.9°C temperature loss within 30 minutes of oral FC. Mice that experienced a severe reaction received anti-TNP IgE and IL-4C and i.g. OVA-TNP and experienced a ≥ 3.7°C temperature loss within 30 minutes of the FC.

Anaphylaxis Assessments:

Hypothermia (significant loss of body temperature) was used as an indication of an anaphylactic reaction. Rectal temperature was taken with a rectal probe and a digital thermocouple thermometer (Model BAT-12; Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ, USA). Temperature was taken prior to the challenge and then every 15 min for 30 or 60 minutes to identify maximum temperature change as previously described17.

Processing of blood samples and RNA isolation.

Whole blood samples were collected from iIL9Tg mice 2 hours following the intragastric challenge into PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and frozen at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated using PAXgene Blood miRNA Kit and fully automated QIAcube system (Qiagen), according to manufacturer’s isolation protocol. The purity of isolated RNA was assessed using the NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer and integrity was determined on Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All samples used for library preparation had RNA integrity values greater than 7.0. Extracted RNA samples were stored at −80ºC before further processing.

Sample Library Preparation.

We performed library preparation using the TrueSeq stranded total RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After Ribo-Zero rRNA depletion, the remaining RNA was purified, fragmented, and primed for first strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II) and random primers, followed by second strand cDNA synthesis performed in the presence of dUTP. Blunt ended double strand DNA was 3’ adenylated and multiple indexing adapters (T-tailed) were ligated to the ends of the ds cDNA. Fragments with adapter molecules on both ends were selectively enriched with 15 cycles of PCR reaction. Forty-four libraries were normalized to the final concentration of 10 nM and then pooled in equimolar concentrations. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina Hiseq 2000 sequencing system in 2 × 100 sequencing cycles using pair-end sequencing mode.

RNA sequencing data analysis:

Mice transcriptome:

FASTQC program and Trimmomatic tool were used to examine the quality of raw reads and filtering poor quality reads, respectively. Genome indexing was performed using Bowtie2 and the reads were aligned to the mm9 mouse reference genome (GRCm38) using HiSAT2 program with the default options. We performed RNAseq analyses of n = 3 control, n = 5 mild-moderate and n = 4 severe reactive groups. Read counts were generated using the feature-counts function from the subRead package.

Differential gene expression:

Downstream analysis was performed using DEseq2 in R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and IDEP 9.1 webtool where the read counts were analyzed to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Given the small sample size and that our primary outcome was to capture all genes associated with food allergic severity we did not apply a false discovery rate (FDR) criteria and filtered DEGs using the less stringent criteria of p-value ≤ 0.05 and fold change (FC) > 2. Heatmaps were generated using python script using the normalized scale for top 50 differentially expressed genes.

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis:

Identification of GO biological processes using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8. Common and unique genes and pathways were identified and represented as Venn diagram (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). Network analysis was performed in Cytoscape3.7.1. To identify matrix of the correlation coefficients and the correlation p-values between significant DEGs and Temperature loss, we used flattenCorrMatrix function from Hmisc package in R.

Co-expression network analysis:

To create co-expression networks from mice transcriptome data, we used widely known clustering package Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) as previously described 19. This program constructs co-expression modules using hierarchical clustering on a correlation network generated from the transcriptome data. The minimum recommended sample size for WGCNA analyses is n = 15 total samples due to sample-to-sample variability within groups. As our in vivo experiments included usage of strain and aged matched mice and the co-efficient of variation of the temperature loss datasets was < 1 for all samples (control, mild-moderate and severe) and we performed these analyses with n = 12 total samples. Initially, pair wise Pearson correlation was calculated between each gene pair and a network adjacency was calculated by raising the co-expression similarity to a power β. We selected a soft-threshold power of 15 by performing an analysis of the network topology. Correlation network identified by the expression data were used to construct topological overlap matrix (TOM). Correlated genes were hierarchically clustered using ‘1 – TO’ as the distance measure, and the modules were defined by using a dynamic tree cutting algorithm 20. The genes are assigned to the module based on the highest module membership measure, also known as eigengene-based connectivity kME. Association of the modules with the severity were identified using the eigengene and topology connectivity test (p-value ≤ 0.05). FlattenCorrMatrix function was used to identify the correlation matrix for the gene’s present significant modules and the temperature loss data.

Gene expression threshold cutoff analyses:

All genes with a read count > 0 and average normalized counts were determined using IDEP 9.1 webtool. To identify uniquely expressed RNA transcripts specific to one condition, we used criteria of average normalized count > 5 in one group and < 5 in the comparative group. Identification of GO biological processes using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8. Common and unique genes and pathways were identified and represented as Venn diagram (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

Human transcriptome:

To identify the genes associated with severity of food allergic reactions, we utilized the raw RNAseq datasets derived from the serial whole blood samples obtained from 19 children before, during, and after randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled oral challenges to peanut (n = 19 subjects, discovery cohort)21. All clinical characteristics, allergy status, sample collection, sample library preparation and sequencing are described in 21. For RNAseq data analysis, the quality was analyzed using FASTQC and qualified raw reads were aligned to Human genome GRch38 using HiSAT2 program with the default options. Read counts were identified using the feature-counts function from the subRead package. DESeq2 package was used to identify the significantly DEGs for each combination of study groups (baseline, 2 hours and 4 hours for Placebo and Peanut) with the p < 0.05, FDR 10% and FC > 2. Downstream analysis such as pathways and the network analysis were performed as described above. To identify the genes associated with severity score, we used FC of all DEGs for each individual (by dividing the gene expression of Peanut 4 and Peanut 0) and severity score identified for each subject and performed correlation analysis in R. The severity score was determined using a threshold-weighted reaction severity score calculated for each individual as the product of symptom grade and dose factor as previously described 22. Scoring based on the product and combination of symptom grade and eliciting dose has been used in prior studies of peanut allergy severity 23,24. Peanut severity genes identified within an independent cohort (n = 21 subjects) are previously described 22. Study design, clinical characteristics, allergy status, sample collection, sample library preparation and sequencing of the replication cohort are described in 21,22. To identify core anaphylaxis severity transcriptome genes associated with food allergy severity the in vivo mouse severity gene set (429 genes) was mapped onto the human severity genes set (335 genes) using the MGI database to identify homologous genes.

Flow cytometry:

Peripheral blood from mice was collected into K3 EDTA tubes by submandibular puncture 2 or 6 hours following anti-IgE treatment. 100μl of whole blood was RBC-lysed and washed twice with staining buffer (2% FBS, 1 mM EDTA). Cell viability within samples was routinely assessed to be ~90-95% using trypan blue staining. Samples were Fc blocked using rat anti-mouse anti-CD16 / CD32 antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and stained with Anti-CLEC4E (MBL International, Woburn, MA) and/or GPR27-Biotin (Antibodies-Online Inc., Limerick, PA, USA) (1:50) at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes. Samples were washed twice with staining buffer and stained with Donkey anti-rat AF488 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) and Streptavidin-PECy7 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) (1:100 each) on ice for 30 minutes. Samples were washed twice and stained with rat anti-mouse antibodies for Ly6C-Allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7, Ly6G-Phycoerythrin (PE), CD11b-BV421 and armenian hamster anti-mouse CD3ε-Brilliant Violet (BV) 605 (1:100 dilution), with or without rat anti-mouse CD218a-APC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) (1:50) on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were subsequently washed twice and resuspended in 100μl of staining buffer. For analyzing expression of CLEC4E, GPR27 and CD218A respective Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) controls were used as previously described25. Samples were acquired using a NovoCyte (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and data was analyzed using FlowJo software (V9) (BD Biosciences).

Results:

To begin to define the dysregulated pathways associated with severe food allergic reactions we collected whole blood from control mice and mice that experienced mild-moderate and severe IgE-mediated food allergic reaction and performed bulk transcriptomics analysis on whole blood two hours following oral antigen exposure (Figure 1 and 2). Control mice were defined as mice that did not experience shock (hypothermia) response 30 minutes following oral food challenge (OFC). Mice that experienced a 1.5 - 1.9°C temperature loss within 30 minutes of oral FC were defined as mild to moderate reactive and mice that experienced ≥ 3.7°C temperature loss within 30 minutes of the FC were defined as severe reactive (Fig 1 and Fig 2A and B).

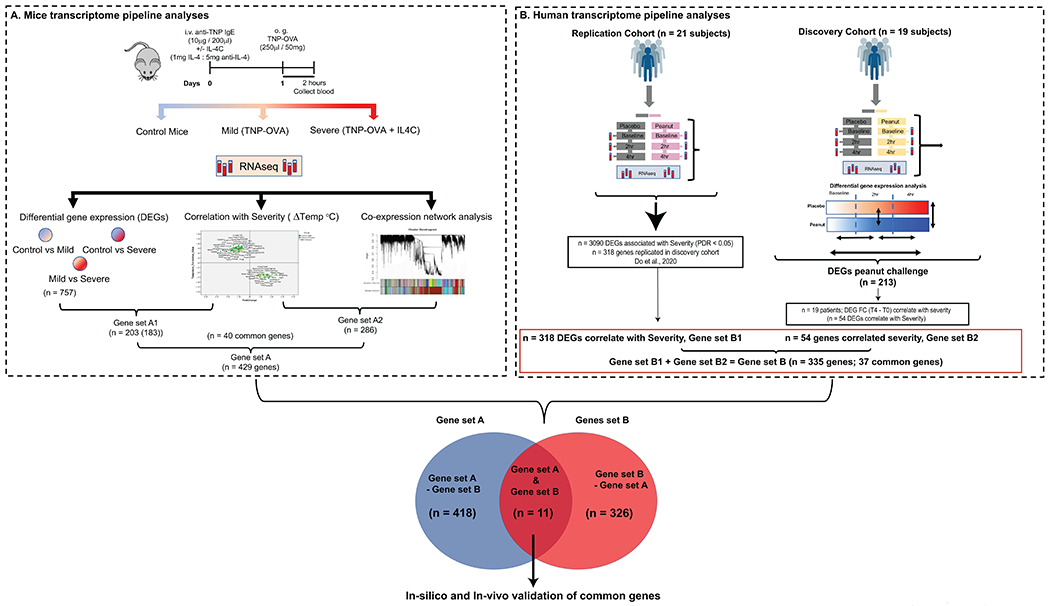

Figure 1: Flowchart of approach to identifying Food allergy severity transcriptome.

A. Graphic representation of the pipeline analyses identifying murine DEGs in whole blood that correlate with severity of oral antigen-induced IgE-mediated reaction. DEGs (FC > 2, p < 0.05) that correlated with severity (Temperature change) (203 genes) and WGCNA analysis identifying co-expression genes networks correlated with severity (n = 286 genes) identifying n = 429 unique genes described as Gene set A. B Human transcriptome and severity correlation. Pipeline for human analyses analyzing DEGs in whole blood that correlated with severity in peanut allergic individuals in discovery cohort (n = 19) and independent cohort (n = 21) who underwent physician-supervised peanut challenge. In the discovery cohort, of the DEGs (FC >2, FDR < 0.1 and p value < 0.05) between T4 and T0 of peanut challenge (n = 213), n = 54 genes correlated with severity. Mapping the n = 54 genes that correlated with severity onto the n = 318 genes that correlated with severity in the independent cohort (n = 21)22 identified 335 unique genes described as Gene set B. Mapping the murine and human unique genes that correlated with severity identified 11 core common genes described as anaphylaxis severity transcriptome.

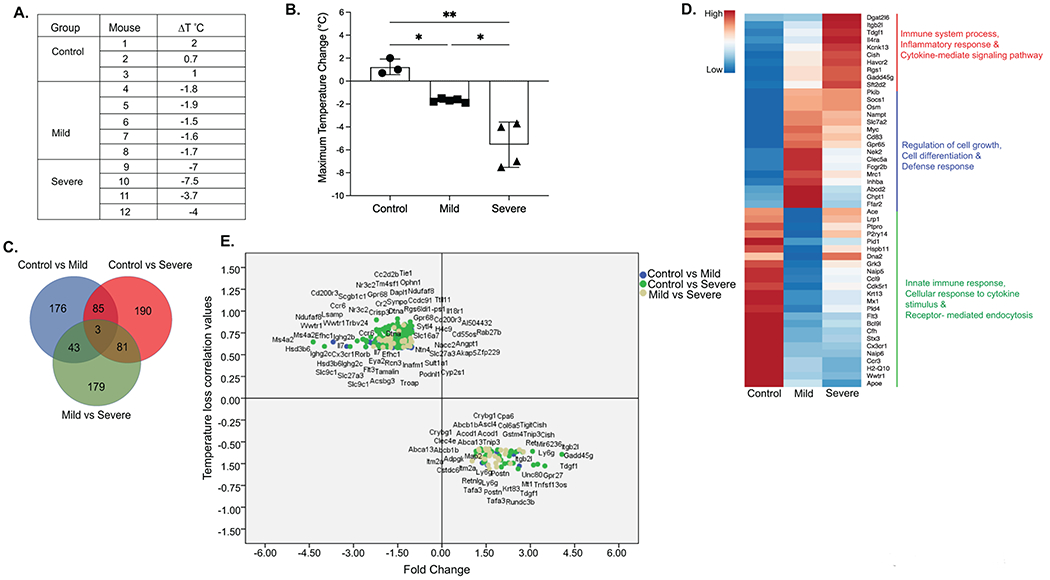

Figure 2: A. Whole blood differentially expressed genes associated with severity of IgE-mediated food allergy in mice.

A. Description of Anaphylaxis groups, treatment and Maximum temperature change (ΔT°C) in mice. B. Graphical representation of Maximum temperature change (ΔT°C) in iIL9Tg mice immunized with anti-TNP-IgE and subsequently received oral gavage OVA-TNP. Data represents mean ± SD of Maximum temperature change in mice 30 minutes following o.g. OVA-TNP. Symbols represents individual mice. * p<0.05, **p<001, ***p<0001. C. Venn diagram showing common and unique differential expressed genes (DEGs) from Pairwise differential gene expression analyses between Control vs Mild, Mild vs Severe and Control vs Severe groups (FC > 2, p < 0.05). D. Heatmap showing top 50 dysregulated genes in all the conditions. Biological processes for group specific genes extracted using DAVID analyses. E. Scattered plot showing FC of DEGs (FC > 2, p < 0.05) that correlated with Maximum temperature change (ΔT°C). Color code describes genes identified by group comparisons.

Data processing, normalization and quality control resulted in a RNA seq data set consisting of n = 20,728 genes from n = 12 blood samples (control n = 3; mild moderate n = 5 and severe n = 4). Comparison of the gene expression between the three groups (cut-off criteria p < 0.05; Fold Change (FC) > 2) identified a total of 757 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with 307 DEGs (81 upregulated and 226 down regulated) between the control and the mild-moderate reactive (mild transcriptome); 359 DEGs (136 upregulated and 223 down regulated) between the control and the severe reactive group (severe transcriptome) and 306 DEGs (186 upregulated and 120 down regulated) between the mild-moderate and the severe reactive group (Severe-specific transcriptome) (Supplementary Table S1). Mapping the DEGs identified 176 unique DEGs within the mild-moderate reactive transcriptome that were enriched for biological processes associated with defense response including Ffar2, mrc1, Fcgr2b (Fig 2 C and D); 190 unique DEGs within the severe reactive-specific transcriptome enriched for genes involved in immune system and inflammatory response including Itgb2l, Il4ra, cish, Havcr2, rgs1 and gadd45g (Fig 2C and D, Top 50 DEGs shown in 2D; Supplementary Table S2). A total of 85 common DEGs within the mild-moderate and severe reactive transcriptomes were enriched for biological processes associated with defense response including Socs1, Osm, nampt, Cd83 and Gpr65 and 179 DEGs between the mild and severe (Severe-specific transcriptome) (Fig 2C and D, Supplementary Table S2). To determine the relationship between DEG’s and severity of the food allergic reaction, we examined for a correlation between 757 DEGs and level of shock (maximum temperature loss). Of the 757 DEGs, 203 genes correlated with temperature loss (41 DEG negatively correlated and 162 DEGs positively correlated) (Fig 2E; Supplementary Table S3). Genes that negatively correlated with anaphylaxis severity were enriched for biological processes associated with inflammatory response, immunoglobulin mediated, innate response genes including Gpr27, Tdgf1, Gadd45g, Ly6g, Cish (Supplementary Table S4). Genes that positively correlated with severity (↓ DEG and ↓ Temperature Loss) were enriched for biological processes associated with cellular response to TNF, cellular response to lipopolysaccharide and innate immune response, T cell response genes including Cd200r3, Il18r1, Cx3cr1, Gpr68, Angpt1, Tie1, Ccr6, Il7, Trbv24 (Fig 2E and Supplementary Table S4).

We next performed Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify co-expressed gene modules that are associated with the severity traits. Using a total 27,600 gene transcripts, WGCNA identified 94 co-expression modules of which 14 modules were significantly enriched (≥ 30 genes and p < 0.05) (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S5). Performing eigengene and topology connectivity analyses of the 14 significant modules, 5 modules were associated with severe anaphylaxis group (Fig. 3A–C). Three modules; turquoise (1802 genes), midnightblue (176 genes) and white (124 genes) demonstrated a positive correlation with severe anaphylaxis (p < 0.05, r = 1, r = 0.71 and r = 0.64, respectively). 2 modules; purple (157 genes) and grey (333 genes) negatively correlated in severe anaphylaxis (p < 0.05, r = −0.57 and r = −0.86 respectively) (Figure 3B and C). Top pathways enriched within the severity modules that positively correlated with severity include innate immune response, inflammatory response, response to hypoxia and apoptotic processes, negative regulation of apoptotic process and positive regulation of apoptotic process (Supplementary Table S6). Top pathways enriched with severity modules that negatively correlated with severity included protein metabolic processes (protein phosphorylation proteolysis protein ubiquitination) and DNA regulatory processes (DNA repair and cellular response to DNA damage stimulus). Correlation analyses between the genes within these modules with temperature loss identified a total of 286 genes correlated with temperature loss of which 171 genes demonstrated a negative correlation and 115 genes demonstrated a positive correlation with severity (Figure 3C and Supplementary Table S7). We combined the DEGs that correlated with severity (n = 203) (Figure 1 and 2) and the WGNA analyses genes that correlated with severity (n = 286) (Fig 3) to define a gene set of 429 severity genes in the mouse (Figure 1).

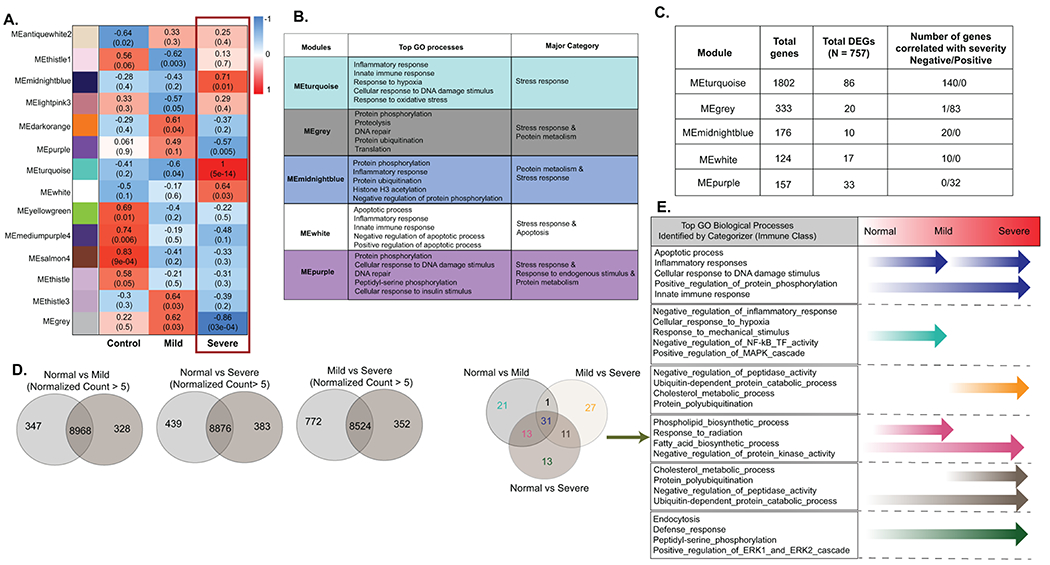

Figure 3: Identification of genes and pathways associated with progression of severe food allergy in mice.

A. Genes modules that significantly correlate with severity identified by WGCNA Co-expression network analysis. Gene modules were created using hierarchical clustering on a correlation network created from transcriptome data. 14 significant modules were identified with at least 30 genes criteria and p-value <0.05. 5 modules were found to be associated with severe anaphylaxis group. Positively correlated modules were shown in red color and negatively associated modules were shown in blue color. Top values describe significance and bracketed values correlation value. B. GO analyses of the five gene modules that significantly correlated with severity Genes were extracted from each gene module and GO analyses was performed using DAVID. To identify the major category of gene ontologies, parent ontologies were extracted using Categorizer database with Immune class category. C. Total number of genes identified within gene modules by WGCNA analyses and the total number of DEGs and genes that correlated with severity within each module. D. Venn diagram showing common and unique genes expressed in different severity conditions. Disease severity specific genes were identified by performing Pairwise gene expression analyses between control vs Mild, control vs severe and mild vs severe. Expressed genes (normalized count > 5) were identified in each group. E. Venn diagram representing gene ontologies associated with specific disease conditions derived from the identified Disease severity specific genes. A list of uniquely expressed genes were used to identify the biological processes (gene ontology) using DAVID analysis. C. Table showing Top 5 GO biological processes from (E) identified by Catagorizer (Immune class) enriched from the unique genes expressed during the different transitions of severity (normal → Mild; Mild → Severe and normal → Severe). The arrows represent biological processes specific to the transition of severity phases.

The WGCNA analyses revealed enrichment of modules associated with innate immune activation and cellular stress response in severity of the food allergic reaction. To define which of these processes were associated with the specific phases of the food allergic reaction (steady state – mild / moderate or mild / moderate - severe), we performed gene expression threshold cutoff analyses. To do this we identified uniquely expressed RNA transcripts specific to no food reaction (control), mild-moderate and severe food-induced reaction using a criterion of average normalized count > 5 in one group and < 5 in the comparative group (Fig 3D). The whole blood transcriptome of untreated mice consisted of 9315 genes, mild-moderate mice 9296 genes and the severe reactive consisted of 9259 genes (Supplementary Table S8). Mapping of the mild transcriptome onto the untreated transcriptome identified 328 unique genes, severe transcriptome onto the untreated transcriptome identified 383 genes and there were 352 genes that were unique in the severe compared with the mild-moderate transcriptome (Supplementary Table S8). Comparison of the expressed genes identified 328 genes specific to the mild reaction, 383 genes to the severe reaction and 352 genes between the mild and severe groups (Supplementary Table S8). GO pathway analysis of the uniquely expressed genes revealed enrichment of GO biological processes through food allergic severity progression (Fig 3B; Supplementary Table S9). We identified enrichment of biological processes associated with cellular response to hypoxia, negative regulation of inflammatory response and NF-kB transcription factor activity and response to mechanical stimulus in whole blood from control (steady state) to mild-moderate disease progression. Progression from the mild to severe phase was associated with the biological processes enriched including negative regulation of peptidase activity, ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, cholesterol metabolic process and protein polyubiquitination (Fig 3E). Comparison of the control to the severe reactive group identified enrichment of biological processes including defense response, peptidyl-serine phosphorylation and positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade. Enrichment of genes associated with GO biological processes observed throughout the course of disease progression (control to mild and mild to severe reactions) included innate immune response, inflammatory processes, apoptotic processes, cellular response to DNA damage stimulus, fatty acid biosynthetic process, and phospholipid biosynthetic process (Fig 3E and Supplementary Table S9). Collectively, these studies suggest that transition from steady state to mild-moderate disease is largely associated with whole blood innate immune activation and inflammation, whereas mild-moderate to severe disease progression is enriched for cellular stress, DNA damage and apoptotic response.

Recently, we performed RNAseq on serial whole blood samples from a cohort of peanut allergic subjects (n = 19, discovery cohort) and an independent cohort of peanut allergic subjects (n = 21) that underwent physician supervised double-blind oral food challenge to both peanut and placebo21. RNA seq performed at baseline (T0), two (T2) and four (T4) hours during the peanut and placebo challenge of peanut allergic subjects and in silico analyses involving linear mixed-effects and probabilistic causal gene network modeling identified six key driver genes (LTB4R, PADI4, IL1R2, PPP1R3D, KLHL2 and ECHDC3) and leukocytes associated with the peanut response module in acute peanut allergic reactions 21. However, the relationship of these key genes to disease severity was not examined. We re-analyzed the raw RNAseq datasets to identify all DEGs independent of factor variables (order, weights, age and individual collection dates) and performed correlation analysis to identify the DEGs that correlated with disease severity.

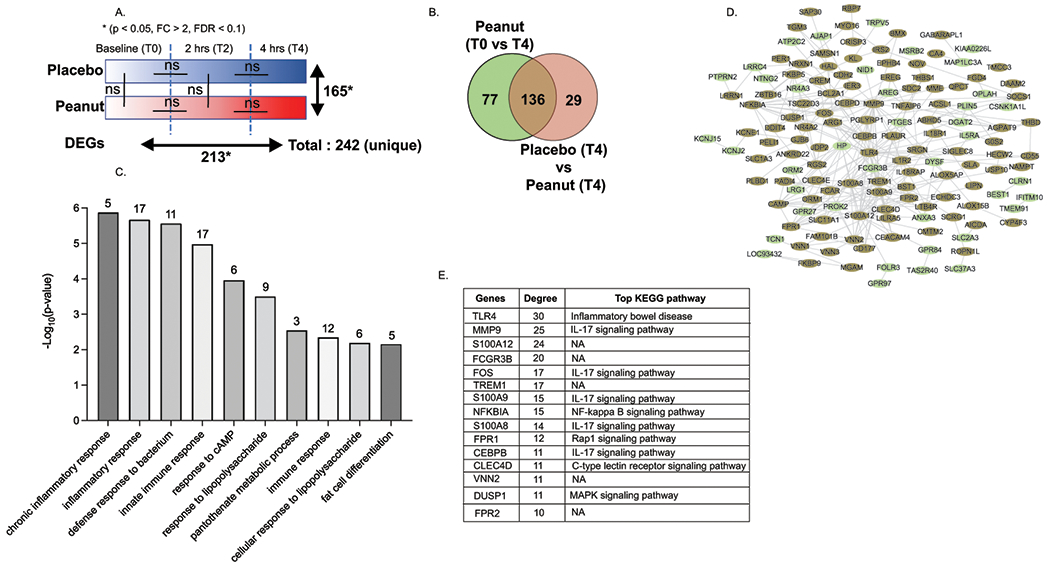

Similarly, to the previous study, comparative analysis of the RNA expression in whole blood at T0 and T2 between the placebo and peanut challenges from the discovery cohort revealed no significant differential expression of genes (p < 0.05, FC > 2, FDR < 0.1) (Figure 4A). Comparison between T0 and T2 and T2 and T4 post peanut challenge revealed no differentially expressed genes (Fig 4A; Supplementary Table S10). Comparison of baseline and T4-post PN-challenge identified 213 DEGs (p < 0.05, FC > 2, FDR < 0.1, Fig 4A). Comparison of genes expressed at T4-post placebo challenge versus T4-post PN-challenge revealed 165 DEGs (Fig 4A, Supplementary Table S10). Mapping the 165 DEGs between T4-post placebo and PN-challenge onto 213 DEGs between baseline and T4-post PN challenge identified a total of 242 unique DEGs (Fig 4A). Within the 242 unique DEGs, 136 DEGs were common between Peanut (T0 vs T4) and T4-post placebo and peanut challenge, 77 DEGS were specific to Peanut (T0 vs T4) and 29 DEGS unique to T4-post placebo and peanut challenge (Fig 4B). We combined the 136 common DEGs and 77 DEGs specific to T4 PN challenge to identify n = 213 DEGs dysregulated by PN challenge (Fig 4B; Supplementary Table S11). GO pathway analyses of the 213 genes revealed enrichment of genes involved in innate immune responses, defense response to bacterium and response to lipopolysaccharide (Fig 4C). Indeed, network pathway analysis of the 213 genes revealed that 162 genes possessed direct protein-protein interactions with the top interactive proteins including TLR4, MMP9, FCGR3B, TREM1, S100A9, NFKBIA that are associated with IL-17 and NF-kappa B signaling pathways (Fig 4D and E; Supplementary Table S12). Correlation analysis of the raw count expression of the n = 213 DEGs with disease severity only identified two genes that significantly correlated with severity (BEND7 p = 0.02; r = 0.052 and TLR8 p = 0.04, r = 0.052). We next performed correlation analyses of the fold change of the n = 213 DEGs with disease severity and identified n = 54 genes that correlated with severity within the discovery cohort (Figure 1B).

Figure 4: A. Identification of genes and pathways associated with progression of severe peanut-induced food allergy.

A. Graphical representation of blinded Food Challenge protocol and description of DEGs (p value < 0.05, FDR < 10% and FC > 2) in serial peripheral blood samples prior to and 2 hours and 4 hours following peanut challenge NA represents No DEGs identified between samples using the described criteria. Peanut baseline (To) vs Peanut 4hr had 213 DEGs while Placebo 4 vs Peanut 4 had 165 DEGs. There are a total 242 dysregulated gene when combined both the list. B Venn diagram representing Common and unique DEGs when comparing DEGs between Peanut T0 vs peanut T4 (n = 213) and Placebo T4 vs peanut T4 (n = 165). Unique and common genes associated with Peanut allergy when compared with Peanut at base and Placebo after 4 hr. C Bar plot representing the top biological process enriched in n = 242 DEGs following peanut challenge. Gene ontology analysis was performed using DAVID. Bar plot is constructed using −Log10 p values. The number of genes associated with the biological processes are shown on the top of each pathway bar column. D Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis of 242 genes. PPI interactions were identified using string database and network was constructed using Cytoscape tool. Color of each node (gene) represents whether common or unique DEG described in B. Green- unique to peanut T0 vs T4; brown- common between peanut T0 vs T4 and Placebo (T4) and Peanut (T4). E Top 15 highly interacted genes in network identified based on degree distribution. All the genes are arranged in high to low degree. Degree shows the direct connection with other genes in network.

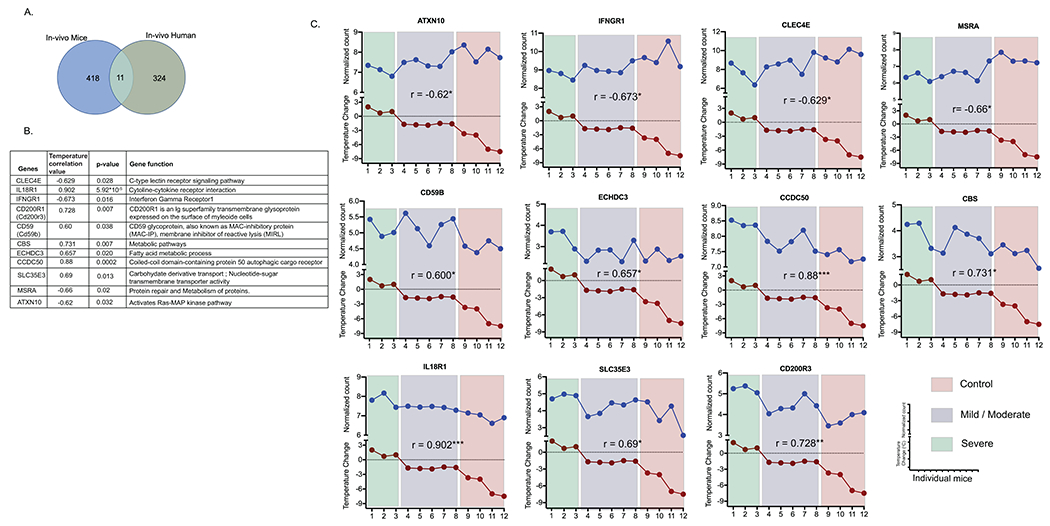

Using a linear mixed model approach, we have previously identified 3090 DEGs from whole blood that were associated with reaction severity (FDR > 0.05) in an independent cohort of peanut allergic subjects (n = 21 subjects), of which 318 genes were replicated in our discovery cohort (n = 19 subjects) 22. We pooled the n = 54 DEGs that correlated with severity in the current analyses with the 318 DEGs identified by Do et al., 22 to generate 335 genes that were differentially expressed following PN challenge and associated with severity (Fig 1). We next mapped the whole blood DEGs that correlated with severity from the mouse (n = 429 genes) onto the DEGs (n = 335 genes) identified within the human cohorts and identified 11 genes which we defined as food allergy severity core transcriptome (Fig 5A and B; Supplementary Table S13). These included four genes that negatively correlated with severity including CLEC4E, IFNgR1, MRSA and ATXN10 and seven genes that positively correlated with severity including IL-18R1, CD200R1, CD59, CBS, ECHDC3, CCDC50 and SLC35E3. Analyses of the individual mice within the steady state, mild and severe food allergic groups demonstrated a significant correlation with gene mRNA expression and disease severity (Fig 5C).

Figure 5: Common Food Allergy severity core transcriptome.

A. Venn diagram showing unique and common DEGs that correlate with severity in mouse and humans. The n = 429 mouse genes identified to correlate with severity were mapped onto the n = 335 genes identified within the discovery and independent cohorts from peanut allergic individuals identifying 11 common genes. B Table of correlation values, p values and the 11 genes identified as anaphylaxis severity core transcriptome in mice and human. Temperature loss correlation and p value of its significance is from mice transcriptome data. Gene functions were identified using KEGG database. C Scattered line graph showing gene expression (normalized counts) and maximum temperature Change during anaphylaxis in individual mice. Correlation value are also represented on each plot.

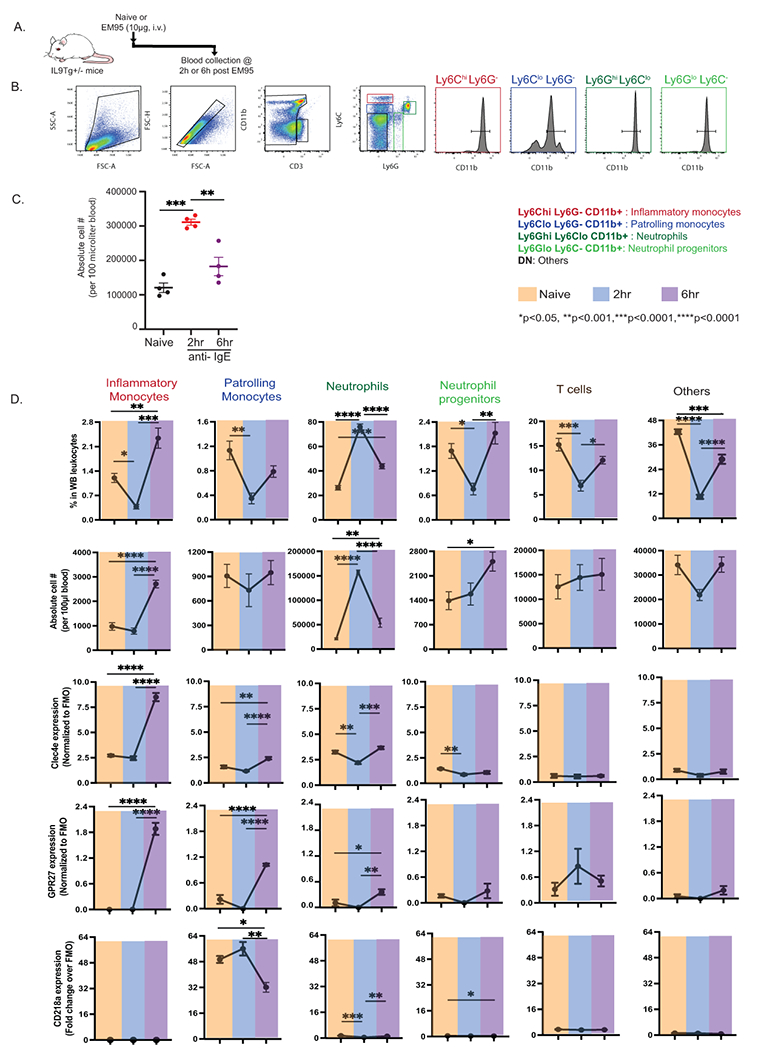

To determine whether changes in gene mRNA expression correlated with changes in protein expression in whole blood, we examined leukocytes in whole blood of IL9Tg mice at 2- and 6-hours following induction of passive IgE-mediated reaction (Fig 6A). Given the observed innate immune phenotype and alterations in myeloid cell populations as demonstrated by RNAseq, we primarily focused on identification of the myeloid cells compartment. Employing the myeloid cell markers CD11b, Ly6C and ly6G we were able to distinguish neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6G+), neutrophil progenitors (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6Glow), inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Chigh Ly6G−) and patrolling monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Clow Ly6G−) in the blood of mice (Figure 6B). Flow cytometry analyses revealed that anti-IgE induced a significant alteration in the absolute numbers of myeloid cell populations including neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6G+), neutrophil progenitors (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6Glow), inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Chigh Ly6G−) but not controlling monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Clow Ly6G−) (Figure 6A and B). Moreover, we observed a rapid increase in absolute numbers of neutrophils at two hours that returned to baseline levels by six hours (Figure 6C). Intriguingly neutrophil progenitor absolute numbers remained constant at two hours but significantly increased by six hours (Figure 6C and D). Similarly absolute frequency of inflammatory monocytes remained unchanged two hours but significantly increased 3-fold by six hours (Figure 6C and D). We next analyzed for changes in expression of the food allergy severity transcriptome genes on peripheral blood myeloid cells during IgE-mediated reaction. We focused our analysis on the food allergy severity transcriptome genes, Clec4e and Il18r1 (CD218A) and an Orphan G protein-coupled receptor Gpr27, a DEG in both mouse and human analyses and correlated with severity in the mouse but not in humans. Intriguingly, we revealed increased expression of CLEC4E and GPR27 on inflammatory monocytes six hours following induction of the IgE-mediated reaction (Fig 6D). Similarly, we observed increased expression of GPR27 and CLEC4E and decreased expression of CD218A on patrolling monocytes at six hours (Fig 6D). We observed decreased surface expression of CLEC4E and CD218A on neutrophils two hours following induction of the IgE-mediated reaction with levels significantly increasing 6 hours post challenge. We did not observe any significant different in expression of these molecules on T cells and other leukocytes at two- and six-hours post IgE challenge (Fig 6D) demonstrating that the altered expression was specific to myeloid cell compartment.

Figure 6. Flow cytometry analyses of myeloid cell populations in peripheral blood of mice following passive IgE-mediated anaphylaxis.

A. Experimental protocol, B. Representative flow plots showing identification of myeloid cell populations in the peripheral blood of mice gating on CD3− CD11b+ populations and gating on Ly6C and Ly6G populations. Following cell populations were defined as CD3− CD11b+ neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6G+), neutrophil progenitors (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6Glow), inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Chigh Ly6G−) and patrolling monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Clow Ly6G−) in the blood of mice. Cell populations (B) and absolute leukocyte count (C) in the blood of naïve (top panel) mice and mice treated with anti-IgE at 2 hours (Middle panel) and at 4 hrs (lower panel) following challenge. E. Percentage and Absolute count of neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6G+), neutrophil progenitors (CD11b+ Ly6C− Ly6Glow), inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Chigh Ly6G−) and patrolling monocytes (CD11b+ Ly6Clow Ly6G−) in the blood of naïve (orange) mice and mice treated with anti-IgE at 2 hours (blue) and at 4 hrs (purple) following challenge. Data represents mean ± SD of n = 4 mice from two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

Discussion

Herein we have integrated in vivo and in silico mouse and human data sets to identify core differentially expressed genes and pathways involved in the progression of a severe food allergic reaction. We identified enrichment of defense, innate immune, stress response, apoptosis and protein metabolism pathways within the whole blood through the progression of a food allergic reaction severity. The mouse-human core severity transcriptome consisted of 11 genes involved in defense and innate immunity (CLECE4E, IL18R1, IFNGR1, CD200R1, CD59) and stress response and apoptosis (CD59B, CBS, ECHDC3 AND SLC35E3) and we demonstrate rapid dysregulation of frequency and CLEC4E, GPR27 and CD218A expression on blood myeloid cell populations (inflammatory monocytes, patrolling monocytes and neutrophils) following IgE-mediated reaction in mice. Collectively, these studies reveal rapid innate immune activation and cellular stress and apoptosis response is associated with severity of food-induced reactions in mouse and humans.

We recently reported RNAseq on serial whole blood samples from a cohort of peanut allergic subjects (n = 19, discovery cohort) and an independent cohort of peanut allergic subjects (n = 21) that underwent physician supervised DBPCFC and identified six key driver genes associated with the peanut response module in acute peanut allergic reactions 21. Furthermore, we identified 3090 DEGs from whole blood that were associated with reaction severity (FDR > 0.05) in the peanut allergic subjects (n = 21 subjects), of which 318 genes replicated in our discovery cohort (n = 19 subjects) 22. The linear mixed-effects and probabilistic causal gene network modeling revealed key genes associated with disease severity however whether DEGs correlated with disease severity was not previously reported. Herein, we decided to use a discovery approach utilizing less stringent criteria to capture all genes associated with disease severity. We therefore, re-analyzed the raw RNAseq datasets from the n = 19 subject discovery cohort to identify all DEGs independent of factor variables (order, weights, age and individual collection dates) that correlated with disease severity and pooled those genes with the previously identified DEGs that were identified to be associated with disease severity 22 to generate 335 gene food allergy severity transcriptome in humans. We then mapped these DEGs onto DEGs from whole blood that correlated with disease severity in the mouse model system (n = 429) and identified 11 genes significantly dysregulated and correlated with severity.

The whole blood analyses in the mouse revealed enrichment of pathways involved in immune system, inflammatory response and cytokine mediated signaling pathway. Correlative analyses revealed significant dysregulation of a core interactive signaling network linked with innate immunity (Tlr3, Cx3cr1, Cxcl5, Ly6g, Klrk1, Il18r1, Acod1, Tnip3), complement activation (Cr2, Ncr1) and negative regulation of protease activity (serpinb6a, Serpinb6b and Sperinb2) with increased severity of the food-induced reaction. Similarly, peanut-induced DEGs in whole blood from peanut-challenged individuals were highly enriched for genes associated with innate immune response, response to lippolysaccharide and positive regulation of NF-KappaB transcription factor activity including CXCL8, S100A8, S100A9, TLR4, TLR2 AND NFKBIA. These observations are consistent with microarray analyses of patients that experienced food- drug- and insect-induced anaphylaxis that revealed increased mRNA of genes (TLR4, MYD88, TREM1, CD64) associated with innate immune activation 26 suggesting that anaphylactic reactions in general are linked with activation of these processes in leukocytes within the whole blood 27.

The 11 common genes significantly dysregulated and correlated with severity in human and mouse included CLEC4E, IL18R1, IFNGR1, CD200R1, CD59, CBS, ECHDC3, CCDC50, SLC35E3, MSRA and ATXN10. Notably, a number of these core anaphylaxis severity genes were innate immune genes including CLEC4E, IFNGR1, IL18R1, GPR27 AND CD59B. IFNGR1 is expressed by most hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells and plays an important role in host defense against intracellular bacterial pathogens and myeloid cells are a key target of IFNγ during early innate inflammatory responses 28. IFNγ activation of IFNGR1 receptor complex (IFNGR1 / IFNGR2) in monocytes induces classical M1 (microbicidal) activation state and STAT-1-dependent cytokine and chemokine gene transcription and myeloid cell reactive nitrogen and oxygen species formation 29. IL18R1 is a member of the interleukin one receptor family and is known to be expressed on neutrophils and monocyte populations 30,31 and IL-18R1 activation leads to downstream NFKB and MAP kinase signaling pathways in myeloid cells. IL18 is also known to reduce cytokine and chemokine expression in neutrophils and promote respiratory burst thereby promoting early innate immune responses 32. CD59B is a glycoprotein expressed on monocytes and granulocytes and is known to interfere with complement pathway C9 to C5b-C8 protein-protein interaction inhibiting the assembly of the membrane attack complex and lytic activity 33,34. Complement activation and LPS are known to enhance Cd59 mRNA expression via NFKB signaling and acts to protect immune cells from complement attack 35. While IgE-mediated responses do not activate the complement pathway directly, there is evidence supporting complement activation in anaphylaxis 36. CLEC4E (Mincle) is a C-Type Lectin Domain Family 4 Member E type II transmembrane C-type lectin receptor expressed in macrophages and neutrophils 37,38. CLEC4E is known to recognize multiple different ligands associated with cell stress including pathogens, glycolipids (β-glucosylceramide), cholesterol sulfate and the nuclear protein spliceosome-associated protein 130 (SAP130) released from necrotic cells. Activation of CLEC4E stimulates NFkB and MAPK-signaling cascades and downstream transcription of inflammatory genes39. CLEC4E deficiency is known to protect against tissue damage and subsequent atrophy of the kidney after ischemia–reperfusion injury 40. GPR27 is a highly conserved, orphan G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) expressed on granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils) and monocytes and has been linked with regulation of glucose homeostasis 41. The observed link between dysregulation of myeloid cell genes and severe IgE-mediated reaction is consistent with the observed increased expression of myeloid cell, neutrophils and monocytes genes in patients with anaphylaxis 26,42.

We identified that IgE-mediated reactions were associated with a rapid change in myeloid cell absolute numbers in blood with neutrophils increasing ~3-fold within 2 hours followed by an increase in inflammatory monocytes at 6 hours post reaction. Furthermore, we observed significant differential expression of CLEC4E, GPR27 and CD218A on both inflammatory and patrolling monocytes and neutrophil progenitors and neutrophils. Collectively, these observations suggest that IgE activation in mice is associated with rapid monocyte and neutrophil activation and tissue margination. Previous studies have reported increased myeloperoxidase levels in humans during anaphylaxis 42. Similarly, increased levels of neutrophil activation markers including MMP9, TREM1, S100A8 and S100A9 have been observed in the serum of patients during anaphylaxis42. We currently do not know the molecular basis of the rapid raise in peripheral blood neutrophil absolute numbers. Steady state peripheral blood circulating neutrophil levels are maintained by a fine balance between granulopoiesis, mobilization from the bone marrow and release of the pool of neutrophils marginated to the vascular endothelium 43. The observed change in mature neutrophils (Ly6GHiLy6ClowCD11b+) and not neutrophil progenitors (CD11b+ Ly6GlowLy6C−) absolute numbers in the blood at 2 hours suggests that the marginating pool of neutrophils maybe contributing to the neutrophilia. One challenge of studying neutrophil and monocyte activation in anaphylaxis in humans is the usage of epinephrine 21,26,42. β-adrenergic agonists are known to activate monocytes and neutrophils and alter circulating myeloid cell levels 44,45,43–45. The mouse studies were performed in the absence of epinephrine administration, suggesting that the observed monocyte and neutrophil changes that are observed in both human and mouse anaphylaxis may not be attributed to epinephrine.

Our gene expression threshold cutoff analyses identified novel genes expressed within the whole blood leukocyte populations during steady state, mild - moderate and severe conditions. These analyses provided insight intothe sequential genes and pathways associated with progression of the severity of the reaction. We identified that progression from steady state to mild / moderate disease was associated with enrichment of inflammatory and innate immune responses as well as evidence of stress response (apoptotic process, cellular response to DNA damage stimulus). Whereas progression from mild / moderate to severe reaction, was associated with significant enrichment of cellular stress and altered protein and cellular metabolism pathways suggesting increased cellular catabolism and stress. We identified Enoyl-CoA Hydratase Domain Containing 3 (ECHDC3) and Cystathionine beta-Synthase (CBS) as core anaphylaxis severity genes. ECHDC3 is a mitochondrial enzyme that is thought to be involved in β-oxidation pathway of fatty acid metabolism 46. CBS acts through regulation of hydrogen sulfide generation and homocysteine metabolism during hypoxia 47. Hypoxia is often associated with severe anaphylactic shock 48. Collectively, these studies suggest that progression to mild disease phenotype is linked with a dominant innate inflammatory immune activation and transition to severe phenotype is associated with cell catabolism and stress response. A causative role for the innate inflammatory immune activation to cell catabolism and stress response and the severity of the reaction remains to be determined. We speculate that that the increased innate immune activation of the whole blood myeloid cell compartment gives rise to innate NFkB-activating cytokines and activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-related mechanisms which promotes cellular stress and altered protein and cellular catabolism driving severity of the food allergic reaction.

We have utilized an integrative combinatorial approach employing mouse model systems and human data sets to identify dysregulation of critical genes and pathways involved in innate immune activation in the myeloid cell compartment in progression of severity of IgE mediated reactions. These studies identify new genes and pathways that may help explain the progression of the severity phenotype and possibly identify biological markers of IgE-mediated anaphylactic reactions.

Supplementary Material

Key message.

Food allergy severity transcriptome consists of innate immune activation, cellular stress, and apoptosis response genes

Dysregulation of Clec4e, Il18r1 (CD218A) and Gpr27 surface expression on inflammatory monocytes following IgE-mediated reaction.

These studies identify genes and pathways associated with progression of the severity of IgE-mediated reactions.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U19AI136053 (S.B.) and AI138177, AI140133 and AI112626; M-FARA; and the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center supported (to S.P.H.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Bibliography

- 1.Sampson HA. Anaphylaxis and emergency treatment. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1601–1608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross MP, Ferguson M, Street D, Klontz K, Schroeder T, Luccioli S. Analysis of food-allergic and anaphylactic events in the national electronic injury surveillance system. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Sampson HA. Food anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 Suppl):S1–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuman-Sunshine DL, Eckman JA, Keet CA, et al. The natural history of persistent peanut allergy. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2012;108(5):326–331 e323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sicherer SH, Burks AW, Sampson HA. Clinical features of acute allergic reactions to peanut and tree nuts in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1):e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren CM, Otto AK, Walkner MM, Gupta RS. Quality of Life Among Food Allergic Patients and Their Caregivers. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2016;16(5):38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avery NJ, King RM, Knight S, Hourihane JO. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2003;14(5):378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings AJ, Knibb RC, Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, King RM, Roberts G, Lucas JS. Management of nut allergy influences quality of life and anxiety in children and their mothers. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2010;21(4 Pt 1):586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flokstra-de Blok BM, Dubois AE, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, et al. Health-related quality of life of food allergic patients: comparison with the general population and other diseases. Allergy. 2010;65(2):238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hourihane JO, Grimshaw KE, Lewis SA, et al. Does severity of low-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges reflect severity of allergic reactions to peanut in the community? Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2005;35(9):1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wainstein BK, Studdert J, Ziegler M, Ziegler JB. Prediction of anaphylaxis during peanut food challenge: usefulness of the peanut skin prick test (SPT) and specific IgE level. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2010;21(4 Pt 1):603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ta V, Weldon B, Yu G, Humblet O, Neale-May S, Nadeau K. Use of Specific IgE and Skin Prick Test to Determine Clinical Reaction Severity. Br J Med Med Res. 2011;1(4):410–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summers CW, Pumphrey RS, Woods CN, McDowell G, Pemberton PW, Arkwright PD. Factors predicting anaphylaxis to peanuts and tree nuts in patients referred to a specialist center. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):632–638.e632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos AF, Du Toit G, Douiri A, et al. Distinct parameters of the basophil activation test reflect the severity and threshold of allergic reactions to peanut. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahrens R, Osterfeld H, Wu D, et al. Intestinal mast cell levels control severity of oral antigen-induced anaphylaxis in mice. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180(4):1535–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamani A, Wu D, Waggoner L, et al. The vascular endothelial specific IL-4 receptor alpha-ABL1 kinase signaling axis regulates the severity of IgE-mediated anaphylactic reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(4):1159–1172.e1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forbes EE, Groschwitz K, Abonia JP, et al. IL-9– and mast cell–mediated intestinal permeability predisposes to oral antigen hypersensitivity. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):897–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshpande V, Sharma A, Mukhopadhyay R, et al. Understanding the progression of atherosclerosis through gene profiling and co-expression network analysis in Apob(tm2Sgy)Ldlr(tm1Her) double knockout mice. Genomics. 2016;107(6):239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langfelder P, Zhang B, Horvath S. Defining clusters from a hierarchical cluster tree: the Dynamic Tree Cut package for R. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(5):719–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson CT, Cohain AT, Griffin RS, et al. Integrative transcriptomic analysis reveals key drivers of acute peanut allergic reactions. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Do AN, Watson CT, Cohain AT, et al. Dual transcriptomic and epigenomic study of reaction severity in peanut-allergic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1219–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flinterman AE, Knol EF, Lencer DA, et al. Peanut epitopes for IgE and IgG4 in peanut-sensitized children in relation to severity of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):737–743 e710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis SA, Grimshaw KE, Warner JO, Hourihane JO. The promiscuity of immunoglobulin E binding to peanut allergens, as determined by Western blotting, correlates with the severity of clinical symptoms. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2005;35(6):767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomar S, Ganesan V, Sharma A, et al. IL-4-BATF signaling directly modulates IL-9 producing mucosal mast cell (MMC9) function in experimental food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):280–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis A, Bosio E, Stone SF, et al. Markers Involved in Innate Immunity and Neutrophil Activation are Elevated during Acute Human Anaphylaxis: Validation of a Microarray Study. Journal of innate immunity. 2019;11(1):63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone SF, Bosco A, Jones A, et al. Genomic responses during acute human anaphylaxis are characterized by upregulation of innate inflammatory gene networks. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(2):163–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumatori A, Yang D, Suzuki S, Nakamura M. Cooperation of STAT-1 and IRF-1 in interferon-gamma-induced transcription of the gp91(phox) gene. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(11):9103–9111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S, Becker J, Bechheim M, et al. Characterizing the genetic basis of innate immune response in TLR4-activated human monocytes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida A, Takahashi HK, Nishibori M, et al. IL-18-induced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in human monocytes: involvement in IL-12 and IFN-gamma production in PBMC. Cellular immunology. 2001;210(2):106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung BP, Culshaw S, Gracie JA, et al. A role for IL-18 in neutrophil activation. J Immunol. 2001;167(5):2879–2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holt DS, Botto M, Bygrave AE, Hanna SM, Walport MJ, Morgan BP. Targeted deletion of the CD59 gene causes spontaneous intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2001;98(2):442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishra N, Mohata M, Narang R, et al. Altered Expression of Complement Regulatory Proteins CD35, CD46, CD55, and CD59 on Leukocyte Subsets in Individuals Suffering From Coronary Artery Disease. Frontiers in immunology. 2019;10:2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, Du Y, Ding P, et al. Mouse Cd59b but not Cd59a is upregulated to protect cells from complement attack in response to inflammatory stimulation. Genes and immunity. 2015;16(7):437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khodoun M, Strait R, Orekov T, et al. Peanuts can contribute to anaphylactic shock by activating complement. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(2):342–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee WB, Kang JS, Yan JJ, et al. Neutrophils Promote Mycobacterial Trehalose Dimycolate-Induced Lung Inflammation via the Mincle Pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto M, Tanaka T, Kaisho T, et al. A novel LPS-inducible C-type lectin is a transcriptional target of NF-IL6 in macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;163(9):5039–5048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drouin M, Saenz J, Chiffoleau E. C-Type Lectin-Like Receptors: Head or Tail in Cell Death Immunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2020;11:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka M, Saka-Tanaka M, Ochi K, et al. C-type lectin Mincle mediates cell death-triggered inflammation in acute kidney injury. J Exp Med. 2020;217(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chopra DG, Yiv N, Hennings TG, Zhang Y, Ku GM. Deletion of Gpr27 in vivo reduces insulin mRNA but does not result in diabetes. Scientific reports. 2020;10(1):5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Francis A, Bosio E, Stone SF, et al. Neutrophil activation during acute human anaphylaxis: analysis of MPO and sCD62L. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017;47(3):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berkow RL, Dodson RW. Functional analysis of the marginating pool of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Am J Hematol. 1987;24(1):47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou J, Yan J, Liang H, Jiang J. Epinephrine enhances the response of macrophages under LPS stimulation. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:254686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimitrov S, Lange T, Born J. Selective mobilization of cytotoxic leukocytes by epinephrine. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J, Ibrahim MM, Sun M, Tang J. Enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase in cancer. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2015;448:13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Omorou M, Liu N, Huang Y, et al. Cystathionine beta-Synthase in hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion: A current overview. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2022:109149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown SGA. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.