Abstract

This is a report of in vivo intraperitoneal biopanning, and we successfully identified a novel peptide to target the multiple peritoneal tumors of gastric cancer. A phage display library was injected directly into the abdominal cavity of mice bearing peritoneal tumors of human gastric cancer, and phages associated with the tumors were subsequently reclaimed from isolated samples. The tumor‐associated phages were amplified and the biopanning cycle was repeated five times to enrich for high affinity tumor‐selective binding peptides. Finally, a tri‐peptide motif, KLP, which showed homology with laminin 5 (a ligand for α3β1 integrin), was identified as a binding peptide for peritoneal tumors of gastric cancer. Phage clones displaying the sequence KLP showed 64‐fold higher binding to peritoneal tumors than control phage and were preferentially distributed in tumors rather than in normal organs after intraperitoneal injection into mice. In addition, the KLP phages were more likely to bind to cancer cells in malignant ascites derived from a patient with recurrent gastric cancer. Synthesized peptide containing the motif KLP (SWKLPPS) also showed a strong binding activity to peritoneal tumors without cancer growth effect. Liposomes conjugated with SWKLPPS peptide appeared significantly more often in tumors than control liposomes after intraperitoneal injection into mice. Furthermore, modification of liposomes with SWKLPPS peptide enhanced the antitumor activity of adriamycin on gastric cancer cells. The peptide motif KLP seems a potential targeting ligand for the treatment of peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 1075–1081)

Abbreviations:

- ADM

adriamycin

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- KLP

Lys‐Leu‐Pro

- LipADM

adriamycin encapsulated in control liposome

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- p.f.u.

plaque‐forming units

- SWK‐LipADM

adriamycin encapsulated in liposomes modified with stearoyl SWKLPPS.

Gastric cancer is the second‐most common cancer in the world. Approximately 700 000 patients a year die from gastric cancer worldwide.( 1 ) Peritoneal metastasis is the predominant metastatic pattern in advanced gastric cancer( 2 , 3 ) and the prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer is poor. The median survival time of such patients has been reported to be 3–6 months( 4 ) and a standard treatment for peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer has not yet been established.( 5 )

A big obstacle to establishing effective therapies for peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer is the countless localities, including invisible ones such as cancer cell clusters in malignant ascites. Therefore, the establishment of a methodology that could target individual peritoneal metastatic tumors would bring about a dramatic improvement in the therapeutic efficacy of treatments for peritoneal metastasis. Furthermore, identification of suitable ligands that associate uniquely with peritoneal tumors could enable the selective delivery of anticancer drugs to these tumors, thereby decreasing drug entry into non‐target cells and potentially allowing eradication of disseminated tumor tissues.

Candidate targeting agents have been studied by several groups attempting to confer tumor tropism. The ligands that have been evaluated include a large number of antibodies, including fragments and single chain Fv molecules( 6 ) and growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor( 7 ) and vascular endothelial growth factor.( 8 ) However, this empiric approach to the identification of targeting ligands has recently been largely superseded by the use of library‐based screening systems, which have been designed to allow iterative selection of high affinity ligands by repeated screening and enrichment of living libraries.( 9 )

In the current study, we used a phage panning technique in vivo to identify peptides that bind specifically to peritoneal metastatic tumors of gastric cancer. The peptide‐presenting phage library used was based on a combinatorial library of random peptide heptamers fused to a minor coat protein (pIII) of the M13 phage and contains approximately 2.8 × 109 different sequences.( 10 ) Panning with the library against peritoneal tumors in vivo permits the identification of binding peptide sequences by extrapolation from the corresponding DNA sequences of phages recovered from the tumor nodules.

This is a report of in vivo intraperitoneal biopanning, and we successfully identified peptides capable of binding to peritoneal metastatic tumors. In this strategy, phage libraries were injected directly into the abdominal cavity of mice bearing peritoneal metastatic tumors, and phages associated with the tumors were subsequently reclaimed from isolated samples. The tumor‐associated phages were then amplified and the biopanning cycle was repeated five times to enrich for high affinity tumor‐selective binding peptides. In addition, in order to confirm the feasibility of future applications of the identified peptides to clinical practice, the tumor‐binding and anticancer activities of one of the peptides were assessed after incorporation into liposomes.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Athymic female BALB/c nu/nµ mice, 6–7 weeks of age, originated from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan), and were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan). The mice were maintained in cages in a laminar airflow cabinet under specific pathogen‐free conditions and provided with free access to sterile food and water.

Cell lines and cell culture. AZ‐P7a cells, a human gastric carcinoma cell line, were kindly supplied by Dr T. Yasoshima (First Department of Surgery, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan). The AZ‐P7a cell line was derived from the AZ‐521 human gastric cancer cell line and was previously reported to show a high potential for peritoneal metastasis in nude mice.( 11 )

Huh‐7 cells, a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, were obtained from the Japan Health Science Foundation (Tokyo, Japan). DLD‐1 cells, a human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line, were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan).

All cells were maintained in RPMI‐1640 medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% FCS, 105 IU/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin (Sigma) in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cells were passaged and expanded by trypsinization of the cell monolayers followed by replating every 4 days.

Mouse model of peritoneal metastasis of human gastric cancer. For mouse inoculation, cells in log‐phase growth were harvested by trypsinization, and a medium containing 10% FCS was added. The cells were washed three times with PBS, resuspended in PBS, then maintained at 4°C until inoculation into mice. After fasting for 24 h, BALB/c nu/nµ mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with samples containing 1 × 107 AZ‐P7a cells in 0.5 mL PBS. After 3 weeks, the inoculated mice had developed peritoneal metastases, and histological examination confirmed that these disseminated tumors consisted of AZ‐P7a gastric cancer cells.

In vivo biopanning in mice with peritoneal metastases. In vivo biopanning was carried out using the above‐described mouse model of peritoneal metastasis. Three weeks after the inoculation of AZ‐P7a human gastric cancer cells, the mice were anesthetized with diethyl ether and injected intraperitoneally with 2 × 1011 p.f.u. of the phage library (Ph.D.‐7 M13 heptapeptide phage display peptide library kit; New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA) suspended in 1 mL of PBS. Twenty minutes after injection, the mice were killed and a few peritoneal metastatic tumor nodules were harvested from each mouse.

The harvested nodules were washed four times with PBS containing 0.5% Tween‐20 (polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monolaurate; Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) to eliminate any unbound phages, then weighed, minced and homogenized in 5 mL PBS containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) using a motor‐driven Teflon‐on‐glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 450g. for 5 min (GS‐15R; Beckman, Palo Alto, CA) and the supernatant was removed without disturbing the tissue pellet. The pellet was suspended in 5 mL of an acidic solution (0.2 M glycine‐HCl, pH 2.2) for 3 min before being centrifuged at 450g. for 5 min to remove any weakly bound phages.( 10 ) The remaining pellet (containing tightly bound phages) was neutralized by adding 750 µL of 1 M Tris‐HCl (pH 9.1), then resuspended in 3 mL of PBS containing 0.5% Tween‐20. The number of eluted phages was estimated by titering a small proportion on agar plates containing Escherichia coli strain ER2738 supplemented with 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl‐beta‐D‐galactopyranoside (Wako, Osaka, Japan) and isopropyl beta‐D‐thiogalactopyranoside (Wako). The remaining phages were amplified by early log phase culture of ER2738 for 5 h at 37°C with vigorous shaking (150 r.p.m). The amplified phages were isolated from the resulting culture according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol, concentrated, titered and used for subsequent rounds of biopanning. In total, five consecutive rounds of biopanning were carried out in triplicate.

Isolation and sequencing of phage DNA. After each round of biopanning, individual phage clones were isolated from each replicate and their total DNA was isolated according to the recommended protocol of the sequencing kit manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA). The resulting DNA was used for sequencing analysis with −96 primer together with a BigDye terminator v3.0 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The DNA sequences were determined using an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Searches for human proteins mimicked by the selected peptide motifs were carried out using online databases available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Evaluation of the binding activities of each selected phage to peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer. After five rounds of biopanning, some phage clones were identified as showing substantial binding to peritoneal metastases. The binding activity of individual phage clones was determined as follows. AZ‐P7a human gastric cancer cells were inoculated intraperitoneally into nude mice. After 3 weeks, the mice were anesthetized and injected intraperitoneally with 2 × 1011 p.f.u. of each selected phage clone suspended in 1 mL of PBS. Twenty minutes after injection, the mice were killed and a few peritoneal metastatic tumor nodules in addition to normal organs (liver, stomach and spleen) were harvested from each mouse. Samples obtained from the tumors and normal organs were weighed, washed with PBS and homogenized. Phages were quantified by titering multiple dilutions of the homogenate, as described above. A phage clone displaying no oligopeptide insert (insertless) was used as a negative control. The results were expressed as p.f.u./g tissue.

From the results of the above‐described experiments, KLP‐containing motifs (SWKLPPS and QPLLKLP) were selected as the most promising consensus sequences and studied in more depth.

Immunohistochemistry. Samples from tumors and normal organs were fixed in buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and mounted on slides. For phage immunolocalization, a rabbit anti‐fd bacteriophage antibody (Sigma) was used at 1:400 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated swine antirabbit immunoglobulins (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) were used as the secondary antibodies at 1:50 dilution. Positive signals were revealed by the addition of diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride.

Measurement of binding of selected phages to human cancer cell lines in vitro. The binding activities of selected phage clone to AZ‐P7a (human gastric carcinoma), DLD‐1 (human colorectal carcinoma) and Huh‐7 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells were determined in six‐well plates.

The cells were acclimatized at 4°C for 30 min, then washed briefly with PBS before the addition to each well of 5 × 107 p.f.u. of the selected phage clone diluted into 1 mL of RPMI‐1640 medium containing 1% BSA (Sigma). The phages were allowed to bind to the cells for 1 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. The media containing unbound phages were discarded, and the cells were then washed four times in PBS containing 1% BSA, before 1 mL of acidic solution (0.2 M glycine‐HCl, pH 2.2) was added for 5 min. The samples were then neutralized by adding 150 µL of 1 M Tris‐HCl (pH 9.1), and the cell‐associated phages were recovered by lysing the cells in 1 mL/well of 10 mM Tris‐HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA on ice for 1 h.

The recovery was determined by plaque infection assays of multiple dilutions of the eluted phages on bacterial lawns grown overnight on agar plates containing 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl‐beta‐D‐galactopyranoside and isopropyl beta‐D‐thiogalactopyranoside at 37°C.

Competitive inhibitory effects of synthesized peptides on phage accumulation in vitro and in vivo. The inhibitory effects of the synthesized peptides on phage accumulation were examined. AZ‐P7a cells were preincubated with 0.1 µM, 1 µM or 10 µM of the SWKLPPS peptide or QPLLKLP peptide (synthesized by SIGMA Genosys Japan, Ishikari, Japan) for 30 min at 4°C, and then 5 × 108 p.f.u. of the selected phage diluted in 1 mL RPMI containing 1% BSA was added. The phages were allowed to bind to the cells for 1 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Media containing unbound phages were discarded, and the cells were then washed four times for 5 min each in PBS containing 1% BSA, before the cell‐associated phages were recovered by lysing the cells in 1 mL/well of 30 mM Tris‐HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM EDTA on ice for 1 h. The number of phages recovered was determined by titering multiple dilutions of the eluted phages as described above. The same experiment was repeated using an irrelevant heptapeptide (TTPRDAY) as a control.

The selected phage clone (2 × 1011 p.f.u.) and 10 µM or 1 mM of each synthesized peptide were co‐injected intraperitoneally into the model mice with peritoneal metastases. The mice were anesthetized and killed 20 min after injection. The peritoneal metastatic tumor nodules were harvested, weighed, washed with PBS and homogenized. The tumor‐associated phages were quantified by titering multiple dilutions of the homogenate, as described above.

Evaluation of the mitogenicity of the SWKLPPS peptide in AZ‐P7a cells. AZ‐P7a cells were plated in 96‐well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well and incubated at 37°C in RPMI medium containing 10% FCS in either the presence or absence of 1 µM, 10 µM or 100 µM of the SWKLPPS peptide. After 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, the viability of the AZ‐P7a cells was assessed using the MTS assay, as described previously.( 12 ) Media were replaced with 120 µL of FCS‐free RPMI containing 20 µL of CellTiter 96 AQueous One solution reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), and the culture plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Next, 100 µL of the medium was transferred to a new 96‐well plate and the quantity of the formazan product present was determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm using a microplate autoreader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Binding of SWKLPPS‐conjugated phages to floating cells in malignant ascites derived from a patient with advanced gastric cancer. A 63‐year‐old male patient diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer had previously been treated by total gastrectomy and systemic chemotherapy. He was admitted to Shinshu University Hospital (Matsumoto, Japan) due to anorexia and severe abdominal distension. Therefore, an abdominal paracentesis was carried out to remove the ascites as a palliative treatment for his symptoms, and gastric cancer cells were cytologically proven to be present in the ascites. A part of the ascites was used for this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to the study.

The collected ascites were centrifuged at 250g. for 5 min and the supernatant was removed without disturbing the pellet. The pellet was suspended in 30 mL of PBS and centrifuged at 250g. for 5 min before the supernatant was removed. This procedure was then repeated. The final pellet was suspended in 30 mL PBS and transferred to a 6‐well plate (3 mL/well). After acclimatization of the cells at 4°C for 20 min, 5 × 108 p.f.u. of SWKLPPS phage or insertless control phage was added to each well of the plate. The phages were allowed to bind to the cells for 30 min at 4°C with gentle agitation. Then, the fluid was collected from each well, centrifuged at 250g. for 5 min and the supernatant was removed. After this procedure was repeated, the pellet was suspended in 2 mL of PBS. The number of phages binding to cells was determined by titering as described above.

Accumulation of SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes in tumors of mice with peritoneal metastases. Distearoylphosphatidylcholine (Nippon Fine Chemical, Osaka, Japan), cholesterol (Sigma) and the stearoyl 7 mer peptide SWKLPPS (molar ratio of 10:5:1) or distearoylphosphatidylcholine and cholesterol without a peptide conjugate (molar ratio of 10:5) were dissolved in chloroform, dried under reduced pressure and stored in vacuo for at least 1 h. Liposomes were prepared by rehydration of the thin lipid film with 0.3 M glucose then subjected to three cycles of freezing and thawing using liquid nitrogen. Next, the liposomes were sized by extruding them three times through a polycarbonate membrane filter with 100 nm pores. For a biodistribution study, a trace amount of [1α,2α(n)‐3H] cholesterol oleoyl ether (Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire, UK) was added to the initial solution.

Mice with peritoneal metastases were prepared as described above. After 2 weeks, the mice were anesthetized and injected with radiolabeled liposomes containing [1α,2α(n)‐3H] cholesterol oleoyl ether intraperitoneally. Twenty‐four hours after the injection, the mice were killed under diethyl ether anesthesia. The blood was collected from the carotid artery and centrifuged (600 g for 5 min) to obtain the plasma. After the mice had been bled, the tumors and normal organs (stomach, liver, spleen, kidney, lung and heart) were removed, washed with saline and weighed. The radioactivity in each sample was determined with a liquid scintillation counter (LSC‐3100; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan). The distribution data were presented as the percentage dose/100 mg wet tissue or the percentage dose/100 µL plasma.

Evaluation of anticancer activity of ADM‐encapsulated liposomes modified with SWKLPPS. ADM‐encapsulated liposomes were prepared by a modification of the remote‐loading method as described previously.( 13 ) The liposomal size and composition were the same as the accumulation study of liposomes. AZ‐P7a cells were plated on a 96‐well plate (5 × 103 cells/well in RPMI containing 10% FCS) and cultured in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24 h. Next, 20 µL LipADM or SWK‐LipADM was added to each well and allowed to bind to the cells for 30 min at 37°C. Then the mediums were changed to RPMI containing 10% FCS and the cells were cultured for a further 24 h. This experiment was repeated at the ADM concentration of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg/mL. Cell proliferation assay was carried out as follows: 10 µL of TetraColor One reagent containing tetrazolium monosodium salt (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well; cells were incubated for 3 h; and absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a reference wavelength at 630 nm in the microplate reader.

Statistics. The results are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of the data from three independent experiments. The significance of differences was evaluated using Student's t‐test or the Mann–Whitney U‐test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Approval for this study was obtained prior to experimentation from the ethics committee of Shinshu University, and all animal procedures were carried out in compliance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Shinshu University.

Results

Iteration of consensus oligopeptide sequence binding to peritoneal metastases. Five consecutive rounds of biopanning were carried out in mice with peritoneal metastases derived from human gastric cancer cells. The phage recovery from each round increased with the number of biopanning passages, except for the third round. After five rounds of selection, 14‐fold more phages were recovered from peritoneal nodules compared to using the native phage library.

After each round of biopanning, individual phage plaques were picked up. Their DNA was isolated and sequenced, and the corresponding amino acid sequences of the inserts were deduced. After the first and second rounds of biopanning, the tumor‐derived sequences displayed no distinguishable homology (data not shown). However, the tumor‐derived sequences from the third, fourth and fifth rounds displayed some consensus motifs, and these were selected as candidate peptides that can bind to peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer. After the fifth round of biopanning, 90–100 phage plaques were picked up from each replicate, and their DNA was sequenced. Next, we compared the relative frequencies of every tri‐peptide motif in each replicate. Tri‐peptide motifs with a frequency of 2.5% or more in the fifth round were selected as candidate binding peptides. The motif frequencies were calculated as the prevalence of each motif‐containing peptide divided by the total number of isolated peptides. KLP was the most frequently encountered tri‐peptide (3.7%), followed by Prp‐Pro‐Leu (PPL; 3.3%), Ile‐Pro‐Pro (IPP; 3.3%), Ala‐Asn‐Pro (ANP; 2.9%), Ser‐Pro‐Thr (SPT; 2.9%) and Ala‐Pro‐Leu (APL; 2.8%).

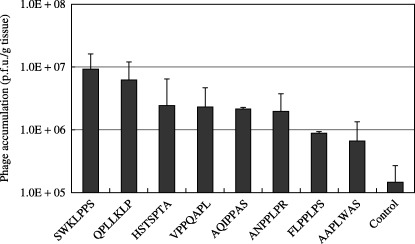

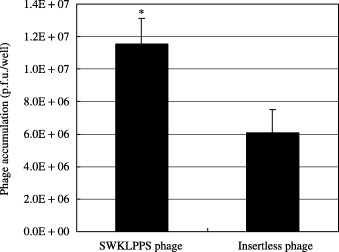

To determine which motif was the best binding peptide, the binding activities of selected phage clones expressing the candidate oligopeptides were assessed in vivo as described above. The phage clone expressing SWKLPPS showed the highest binding, with the recovery of 64‐fold more phages compared with the insertless phage (control) (Fig. 1). Similarly, QPLLKLP showed a 43‐fold higher recovery than the insertless phage. Therefore, the clones showing the best and second‐best recoveries (SWKLPPS and QPLLKLP, respectively) both included the KLP motif. Accordingly, the KLP motif was selected as the most promising motif for binding to peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer.

Figure 1.

In vivo binding activities of selected phage clones expressing the candidate peptides for binding to peritoneal tumors of gastric cancer. Each selected phage clone expressing the candidate peptides was injected intraperitoneally into model mice. The mice were killed 20 min after injection. Peritoneal tumor nodules were harvested from each mouse and homogenized, and the phages accumulated in the nodules were quantified by titering multiple dilutions of the homogenate. The results are expressed as p.f.u./g tissue, and a phage clone displaying no oligopeptide insert was used as a control.

Heptapeptides containing the consensus motif were analyzed using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information) to search for similarity to known human peptides. Interestingly, KLP showed homology with laminin 5, which was reported to be a ligand for α3β1 integrin.

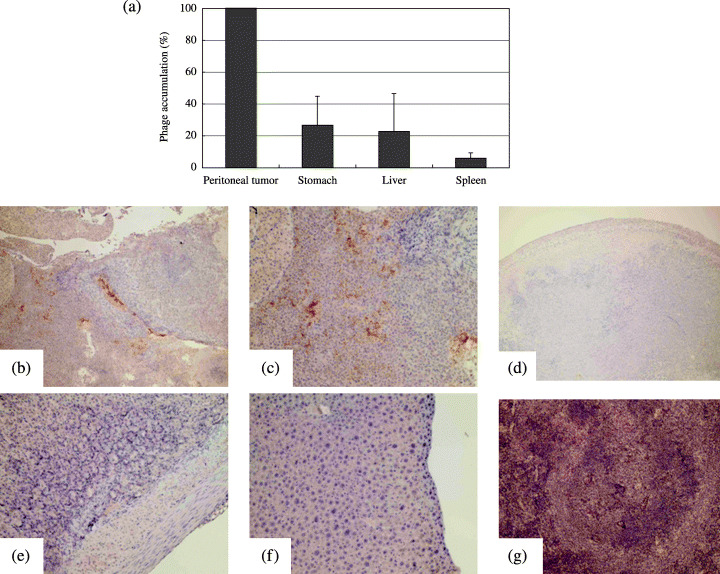

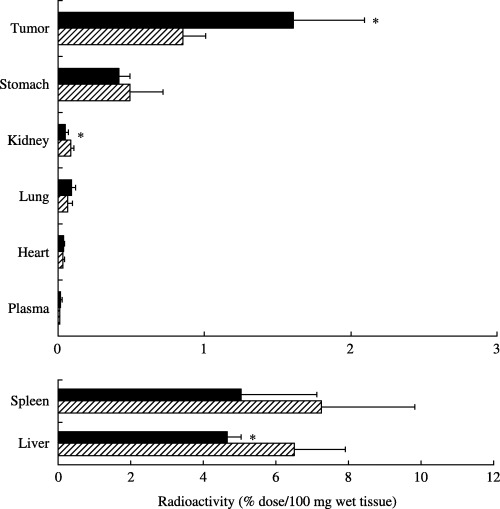

Distribution of the selected phage in the mouse model of peritoneal metastasis. The phage clone displaying the sequence SWKLPPS was injected intraperitoneally into the model mice with peritoneal metastases. The phage accumulation in the tumors and organs was quantified by titering. The mean accumulation of the SWKLPPS phage in normal organs was less than 30% of that in tumors (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Distribution of selected phage clones in model mice with peritoneal metastases. Twenty minutes after intraperitoneal injection of phage clones displaying the SWKLPPS sequence into model mice with peritoneal metastases, samples from the peritoneal tumors, normal stomach, liver and spleen were obtained. The distributions of the phages in the tumors and organs were quantified by titering and expressed as percentages of the accumulation in each organ compared to that in tumors (a). Simultaneously, the phage distributions were evaluated by immunohistochemistry (b–g). Phage accumulation is revealed by brown dots in each figure. (b, c) SWKLPPS phages in a tumor (magnification: ×40 and ×100, respectively). (d) Control phages in a tumor (magnfication: ×40). (e–g) SWKLPPS phages in the stomach, liver and spleen, respectively (magnification: ×100).

Immunohistochemistry was used to characterize the distribution of phage clones expressing the SWKLPPS peptide in the model mice with peritoneal metastases. The SWKLPPS phage showed strong binding to the tumor nodules (Fig. 2b,c), but only a low signal in normal organs such as the stomach, liver and spleen (Fig. 2e–g). Interestingly, the SWKLPPS phage appeared to be on the inside of the tumor nodules in addition to the surface, suggesting a possibility of penetration of the phage into the tumor nodules. However, the insertless phage only showed low signals in both tumors (Fig. 2d) and normal organs.

Binding activities of SWKLPPS‐conjugated phages to human cancer cell lines. The binding activities of the phage clone expressing the SWKLPPS peptides was evaluated on confluent cultures of DLD‐1 or Huh‐7 cells, in comparison with AZ‐P7a cells. The phages showed the greatest recovery from AZ‐P7a cells. The recovery of the SWKLPPS phage from AZ‐P7a cells was 1.3‐ and 13.9‐fold higher than those from DLD‐1 and Huh‐7 cells, respectively. The similar recoveries of the SWKLPPS phage from AZ‐P7a and DLD‐1 can be explained by the supposition that the receptors for SWKLPPS might be similarly expressed in DLD‐1 and AZ‐P7a cells. However, the SWKLPPS phage bound to AZ‐P7a cells 3‐fold more strongly than the control phage in this in vitro experiment.

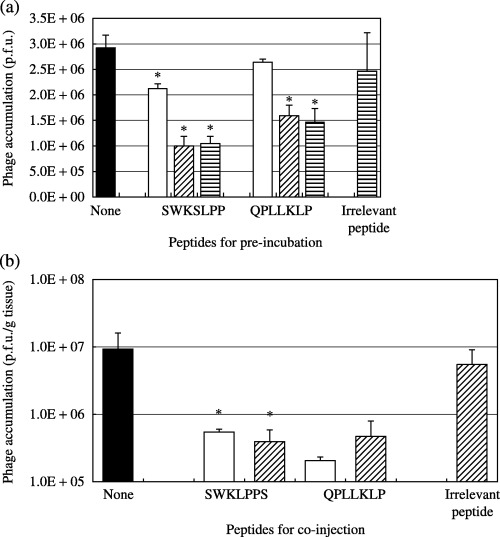

Competitive inhibitory effects of synthesized peptides on phage accumulation in vitro and in vivo. To confirm the capacity of the synthesized peptides to accumulate in tumors, AZ‐P7a cells were pre‐incubated with 0.1, 1 or 10 µM of the SWKLPPS or QPLLKLP peptide before the addition of 5 × 108 p.f.u. of the selected phages. The inhibitory effects of the synthesized peptides on phage accumulation were examined by titering the phages bound to cancer cells. It was found that pre‐incubation of cells with the SWKLPPS peptide caused 66% inhibition of the binding activity of the SWKLPPS phage to these cells (Fig. 3a). In addition, the binding of SWKLPPS phage was also inhibited by the addition of QPLLKLP peptide, indicating that the KLP motif played an important role in binding to the cancer cells in both SWKLPPS and QPLLKLP.

Figure 3.

Competitive inhibition of synthesized peptides against phage accumulation. AZ‐P7a cells were pre‐incubated with 0.1 (□), 1 (▨) or 10 µM (▤) of the SWKLPPS or QPLLKLP peptide for 30 min at 4°C, followed by the addition of 5 × 108 p.f.u. of the SWKLPPS phage in vitro. The inhibitory effects of the synthesized peptides on phage accumulation were examined by titering the phages bound to the cells (a). Similarly, the SWKLPPS phage (2 × 1011 p.f.u.) and 10 µM (□) or 1 mM (▨) of each synthesized peptide were co‐injected intraperitoneally into model mice with peritoneal metastases. The mice were killed 20 min after injection. Peritoneal tumor nodules were harvested, and the phages accumulated in the tumors were quantified by titering to confirm the in vivo inhibitory effects of the synthesized peptides on phage accumulation (b). An irrelevant heptapeptide (TTPRDAY, 10 µM in vitro and 1 mM in vivo) was used as a control. *P < 0.05 compared to the control.

These inhibitory effects of the SWKLPPS peptide were also confirmed in an in vivo experiment using the model mice with peritoneal metastases (Fig. 3b). Similar to the in vitro experiment, the binding of SWKLPPS phage to peritoneal tumor was inhibited by co‐injection of both of SWKLPPS and QPLLKLP peptides.

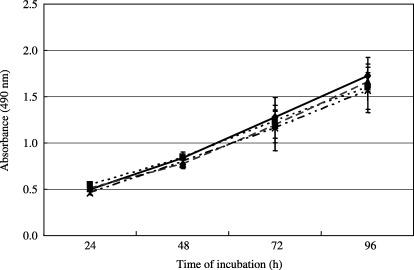

Assessment of the possible mitogenicity of the selected peptide. The possibility that the SWKLPPS peptide might play a role in cancer cell growth (promotion or inhibition) was evaluated using the MTS assay. The presence of the SWKLPPS peptide had no discernible effect on cell growth (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Assessment of the mitogenicity of the SWKLPPS peptide in AZ‐P7a cells. AZ‐P7a gastric cancer cells were incubated in 96‐well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well in the presence of 1 µM (▪), 10 µM (▴) or 100 µM (×) of the SWKLPPS peptide or without the peptide (◆). The cell viability was monitored after 24, 48, 72 and 96 h using the MTS assay. The quantity of the formazan product present was determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm using a microplate autoreader.

Binding of the SWKLPPS phage to floating cells in malignant ascites from a patient with gastric cancer. We carried out an ex vivo experiment investigating SWKLPPS phage binding to floating cells in malignant ascites from a patient with gastric cancer. The SWKLPPS phage or insertless phage was co‐incubated with malignant ascites from the patient, and the number of phages bound to the cells in the ascites was examined by phage‐titering. The results revealed that the SWKLPPS phage bound to cells significantly more than control phage (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Binding of the SWKLPPS phage to floating cells in malignant ascites from a patient with gastric cancer. The ex vivo binding activity of the SWKLPPS phage to floating cells in malignant ascites from a patient with gastric cancer was examined. The ascites from the patient was concentrated by centrifuge and co‐incubated with SWKLPPS phage or insertless phage in 6‐well plate. Then the number of phages binding to cells was determined by titering. *P < 0.05 compared to the control.

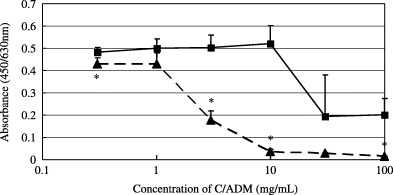

Tumor binding and anticancer activities of SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes in tumors. The accumulation of SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes in tumors of mice with peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer after intraperitoneal injection was examined. SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes accumulated in the tumors significantly more than control liposomes (Fig. 6). On the contrary, significantly less SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes appeared in the liver and kidney than control liposomes. In addition, we evaluated the anticancer activity of adriamycin‐encapsulated liposomes modified with SWKLPPS (SWK‐LipADM), using cell proliferation assay in vitro. SWK‐LipADM showed more efficient anticancer activity than control (LipADM) (Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

Biodistribution of SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes after intraperitoneal injection. Mice with peritoneal metastasis were anesthetized and injected with the radiolabeled liposomes containing [1á,2á(n)‐3H] cholesterol oleoyl ether with stearoyl 7 mer peptide SWKLPPS (▪) or without peptide conjugates (control, ▨) intraperitoneally. The mice were killed 24 h after injection, and blood was collected and centrifuged to obtain plasma. After the mice had been bled, the tumor and normal organs were removed, washed with saline and weighed. The radioactivity in samples was determined with a liquid scintillation counter. Data are represented as the percentage of the injected dose per 100 mg wet tumor tissue or 100 µL plasma. *P < 0.05 compared to the each control.

Figure 7.

Anticancer activity of SWK‐LipADM. After AZ‐P7a cells were plated on a 96‐well plate and cultured in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24 h, 20 µL LipADM or SWK‐LipADM was added to each well at the ADM concentration of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg/mL and allowed to bind to the cells for 30 min at 37°C. The mediums were changed to RPMI containing 10% FCS and cells were cultured for further 24 h. Cell proliferation assay with TetraColor One was carried out. * P < 0.01 compared to LipADM.

Discussion

In the present study, we used a phage display library to identify peptide sequences capable of binding to peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer, with the aim of enabling the use of ligands for delivery of agents to such peritoneal metastases. After five rounds of selection, the consensus sequence KLP was identified and the KLP‐containing peptides were examined in more depth. Sequence analysis revealed that KLP showed homology with laminin 5. Laminin 5 has been reported to serve as a high‐affinity ligand for α3β1 integrin.( 14 , 15 ) Immunohistochemical analysis of specimens of gastric cancer resected from more than 100 patients revealed that the expression of α3β1 integrin was positively correlated with the occurrence of peritoneal and liver metastases and with increased invasiveness of the tumors.( 16 ) AZ‐P7a cells, the human gastric cancer cell line used in this study, possess a high potential for peritoneal dissemination, and were reported to express a significantly higher level of α3 integrins than AZ‐521 cells, from which the AZ‐P7a cell line was derived.( 11 ) Taken together, there is a possibility that α3β1 integrin is one candidate for the binding site of the KLP peptide.

Phage display libraries have shown particular promise for elucidating receptor‐binding peptides, and have recently been used in vitro to identify receptor‐binding mimetics of fibroblast growth factor( 17 ) and vascular endothelial growth factor.( 18 ) However, the major strength of phage libraries is their suitability for application in vivo to enable the identification of ligands capable of targeting specific cells and organs.( 19 , 20 ) By carrying out the selection procedure in vivo, the identified ligands are likely to be active under physiological conditions and their receptors will be accessible with an appropriate route of administration. In particular, this avoids the selection of ligands that bind to receptors that are inaccessible in the polarized in vivo cellular anatomy. Targeting systems that work well in vitro but fail in vivo due to polarization or inaccessibility of the receptors is well known.( 21 ) Therefore, it was important that SWKLPPS was identified as a peptide that bound to peritoneal tumors in an in vivo experiment. Our study showed that the binding efficiency of the SWKLPPS phage to peritoneal tumors was greater in vivo than in vitro (64‐ versus 3‐fold higher than the control, respectively). One possible explanation for this difference is that SWKLPPS might bind to some receptors predominantly activated in vivo, and works better in vivo than in vitro.

As described above, in vivo biopanning procedures using phage display libraries have been used to identify binding peptides for certain organs and tumors.( 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ) and in the majority of these studies, the phage libraries were injected intravenously. In contrast, intraperitoneal in vivo biopanning was used in our study, and we isolated the tumor‐binding peptide SWKLPPS. Compared to intravenous injection, the intraperitoneal approach is clearly more useful for identifying peptides that bind to peritoneal metastases, as a larger number of phages reach the peritoneal tumors after intraperitoneal injection than after intravenous injection. Intraperitoneally injected agents, including phages, reach the tumor directly, whereas a considerable amount of intravenously injected agent is trapped by the reticuloendothelial system, such as the liver and spleen.

Another important advantage of intraperitoneal injection in animals bearing peritoneal metastases of human cancer is that the injected phages bind directly to the human cancer tissue itself. Contrary to this, if the phage is injected intravenously, the majority of the phages could bind to the mouse‐derived microvessels in the tumor rather than to xenografted human cancer cells. This advantage of intraperitoneal injection might have enabled the SWKLPPS phage to bind to cancer cells in ascites from a patient with carcinomatosa peritonitis, despite the fact that SWKLPPS was isolated using an animal study.

The SWKLPPS peptide showed no significant ability to mediate mitogenesis in vitro following binding to gastric cancer cells. This is important for application of a novel peptide to actual cancer treatment, as it is undesirable to give potent mitogens to cancer patients. In addition to this safety profile, SWKLPPS has several pharmacological advantages. The majority of targeting ligands in cancer therapy are relatively large proteins and have some pharmacological limitations, notably a short plasma half‐life, unwanted interactions with serum components and high costs of manufacture. In contrast, SWKLPPS is a simple peptide with excellent stability and a low manufacturing cost. Furthermore, despite consisting of only seven amino acid residues, SWKLPPS is expected to work sufficiently as a targeting ligand, as peptides containing three amino acid residues, such as RGD, have been reported to provide the minimal framework for structural formation and protein–protein interactions.( 23 ) In fact, the competitive inhibition of SWKLPPS phage binding to peritoneal tumors by the synthesized KLP‐containing peptide implies that the synthesized KLP peptide itself has a strong binding activity to peritoneal tumors both in vitro and in vivo.

Liposomes are one of the promising drug delivery systems for cancer treatment.( 24 ) In this study we developed SWKLPPS‐conjugated liposomes and these liposomes accumulated in the tumors significantly more than control liposomes after intraperitoneal injection. Less SWKLPPS liposomes appeared in the intra‐abdominal organs compared to the control (significant difference in the liver and kidney). Similar results have been reported after intravenous injection of peptide‐modified liposomes in tumor‐bearing mice.( 25 ) The reason for this characteristic of peptide‐modified liposomes is not clear at present. One possible explanation in our experiment is a subtraction effect in the biopanning procedure. Namely, in the intraperitoneal biopanning, phage‐selection for tumors could be regarded as a subtraction process for normal peritoneum covering the surface of organs (e.g., liver and kidney). Therefore it might not be strange that SWKLPPS shows the ability to bind tumors and avoid the normal peritoneum simultaneously. In addition, modification of liposomes with SWKLPPS could enhance the anticancer activity of ADM on AZ‐P7a gastric cancer cells. These results encourage us to attempt further investigations to confirm the antitumor effects of SWKLPPS‐conjugated anticancer agents in vivo, aiming for their application to clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Toshiki Tanaka for support in the SWKLPPS peptide synthesis, and Professor Koichi Hirata and Dr Takahiro Yasoshima for supplying the AZ‐P7a cells. This work was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Fujita Memorial Fund for Medical Research and the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology.

References

- 1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55: 74–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kodera Y, Nakanishi H, Yamamura Y et al. Prognostic value and clinical implications of disseminated cancer cells in the peritoneal cavity detected by reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction and cytology. Int J Cancer 1998; 79: 429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakakura C, Hagiwara A, Nakanishi M et al. Differential gene expression profiles of gastric cancer cells established from primary tumour and malignant ascites. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 1153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non‐gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer 2000; 88: 358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yanagihara K, Takigahira M, Tanaka H et al. Development and biological analysis of peritoneal metastasis mouse models for human scirrhous stomach cancer. Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 323–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kashentseva EA, Seki T, Curiel DT, Dmitriev IP. Adenovirus targeting to c‐erbB‐2 oncoprotein by single‐chain antibody fused to trimeric form of adenovirus receptor ectodomain. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 609–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher KD, Stallwood Y, Green NK, Ulbrich K, Mautner V, Seymour LW. Polymer‐coated adenovirus permits efficient retargeting and evades neutralising antibodies. Gene Ther 2001; 8: 341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Backer MV, Backer JM. Targeting endothelial cells overexpressing VEGFR‐2: selective toxicity of Shiga‐like toxin‐VEGF fusion proteins. Bioconjug Chem 2001; 12: 1066–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lorimer IA, Keppler‐Hafkemeyer A, Beers RA, Pegram CN, Bigner DD, Pastan I. Recombinant immunotoxins specific for a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor: targeting with a single chain antibody variable domain isolated by phage display. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 14815–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. New England BioLabs Inc. Ph.D‐7 Phage Display Peptide Library Kit: Instruction Manual. Version 2.7. Beverly: New England Biolabs Inc., 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nishimori H, Yasoshima T, Denno R et al. A novel experimental mouse model of peritoneal dissemination of human gastric cancer cells: different mechanisms in peritoneal dissemination and hematogenous metastasis. Jpn J Cancer Res 2000; 91: 715–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong JK, Kennedy PR, Belcher SM. Simplified serum‐ and steroid‐free culture conditions for high‐throughput viability analysis of primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci Meth 2001; 110: 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oku N, Doi K, Namba Y, Okuda S. Therapeutic effect of adriamycin encapsulated in long‐circulating liposome on Meth‐A‐sarcoma‐bearing mice. Int J Cancer 1994; 58: 415–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carter WG, Ryan MC, Gahr PJ. Epiligrin, a new cell adhesion ligand for integrin alpha 3 beta 1 in epithelial basement membranes. Cell 1991; 65: 599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takatsuki H, Komatsu S, Sano R, Takada Y, Tsuji T. Adhesion of gastric carcinoma cells to peritoneum mediated by alpha3beta1 integrin (VLA‐3). Cancer Res 2004; 64: 6065–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ura H, Denno R, Hirata K, Yamaguchi K, Yasoshima T. Separate functions of alpha2beta1 and alpha3beta1 integrins in the metastatic process of human gastric carcinoma. Surg Today 1998; 28: 1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maruta F, Parker AL, Fisher KD et al. Identification of FGF receptor‐binding peptides for cancer gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther 2002; 9: 543–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Binetruy‐Tournaire R, Demangel C, Malavaud B et al. Identification of a peptide blocking vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) ‐mediated angiogenesis. EMBO J 2000; 19: 1525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. Organ targeting in vivo using phage display peptide libraries. Nature 1996; 380: 364–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arap W, Haedicke W, Bernasconi M et al. Targeting the prostate for destruction through a vascular address. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 1527–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walters RW, Grunst T, Bergelson JM, Finberg RW, Welsh MJ, Zabner J. Basolateral localization of fiber receptors limits adenovirus infection from the apical surface of airway epithelia. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 10219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arap W, Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. Cancer treatment by targeted drug delivery to tumor vasculature in a mouse model. Science 1998; 279: 377–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arap W, Kolonin MG, Trepel M et al. Steps toward mapping the human vasculature by phage display. Nat Med 2002; 8: 121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamaguchi T, Matsumura Y, Nakanishi Y et al. Antitumor effect of MCC‐465, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin tagged with newly developed monoclonal antibody GAH, in colorectal cancer xenografts. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 608–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kondo M, Asai T, Katanasaka Y et al. Anti‐neovascular therapy by liposomal drug targeted to membrane type‐1 matrix metalloproteinase. Int J Cancer 2004; 108: 301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]