Abstract

Chronic infection of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is one of the major causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the world. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) has been long suspected to be involved in hepatocarcinogenesis, although its oncogenic role remains controversial. HBx is a multifunctional regulator that modulates transcription, signal transduction, cell cycle progress, protein degradation pathways, apoptosis, and genetic stability by directly or indirectly interacting with host factors. This review focuses on the biological roles of HBx in HBV replication and cellular transformation in terms of the molecular functions of HBx. Using the transient HBV replication assay, ectopically expressed HBx could stimulate HBV transcription and replication with the X‐defective replicon to the level of those with the wild one. The transcription coactivation is mainly contributing to the stimulatory role of HBx on HBV replication although the other functions may affect HBV replication. Effect of HBx on cellular transformation remains controversial and was never addressed with human primary or immortal cells. Using the human immortalized primary cells, HBx was found to retain the ability to overcome active oncogene RAS‐induced senescence that requires full‐length HBx. At least two functions of HBx, the coactivation function and the ability to overcome oncogene‐induced senescence, may be cooperatively involved in HBV‐related hepatocarcinogenesis. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 977–983)

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a worldwide health problem and is one of the major causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the world. However, new incidences of HBV infection have been dramatically reduced by several prevention programs. The crucial role of HBV in hepatocarcinogenesis is beyond doubt, however, the mechanism by which HBV causes transformation of hepatocytes remains uncertain.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) has long been suspected to play a positive role in hepatocarcinogenesis because HCC incidence has been reported in animals infected with mammalian hepadnaviruses. Among these hepadnaviruses, open reading frame‐X (X‐ORF) is conserved in the genomes. However, hepatocarcinogenesis has not been found in avian infected with avian hepadnaviruses where X‐ORF is absent. In addition to the putative contribution of HBx, other oncogenic mechanisms of the HBV‐related hepatocarcinogenesis have also been proposed, such as the integration‐dependent scenario of HBV DNA in host genomes,( 4 ) and the inflammation‐dependent scenario.( 5 ) Since no higher incidence of HCC has been reported in HBV‐expressing transgenic mice,( 6 ) host immunological responses to HBV infection (but not HBV proliferation by itself) might be primarily contributing to the HBV‐related hepatocarcinogenesis. HBx, a small protein of 154 amino acids, is a multifunctional regulator that modulates a variety of host processes through directly or indirectly interacting with virus and host factors.( 2 , 3 ) In this short review, we briefly summarize the life cycle of HBV, expression of HBx, and the molecular functions of HBx. We then focus on the recent progress on the biological roles of HBx in HBV replication and cellular transformation.

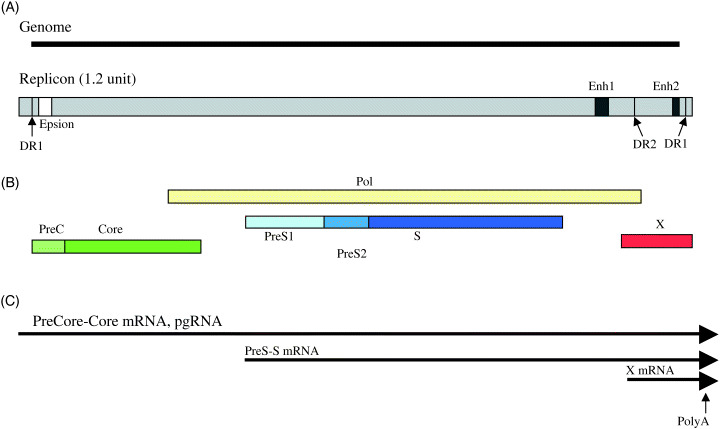

Expression and functions of HBx. HBV is a prototype of Hepadnaviridae, hepatotropic small DNA viruses, of which hosts are among limited species of water birds, squirrels and primates. The HBV genome is a 3.2‐kb circular, partially double‐stranded DNA molecule with four overlapping ORFs, PC‐C, PS‐S, P, and X‐ORFs (Fig. 1).( 7 ) Once HBV infection of hepatocytes occurs, its genome is converted to covalently closed circular (CCC) DNA, which serves as the template for transcription by the host RNA polymerase II, generating the 3.5‐, 2.4‐, 2.1‐, and 0.7‐kb transcripts under control of four HBV promoters (Cp, PS1p, Sp, and Xp), respectively (Fig. 1). Two HBV enhancers (Enh I and Enh II) positively regulate transcription of the HBV promoters in combination with the transcription factors that bind these promoters.( 7 , 8 , 9 ) HBV replicates by reverse transcription of the viral pregenomic 3.5‐kb RNA (pgRNA) using the HBV polymerase that catalyzes RNA‐dependent DNA synthesis and DNA‐dependent DNA synthesis.( 7 , 10 ) The reverse transcription of hepadnaviruses is unique among DNA viruses, and the primer of the reverse transcription is a tyrosine residue of an N‐terminal domain of Pol that is distinct from reverse transcription of retroviruses.( 10 )

Figure 1.

The HBV replication unit and genome structure. (A) Top is the linealized HBV genome. Bottom is the 1.2 genome‐unit of HBV DNA that is enough to synthesize pregenome (pg)RNA and DNA replication. DR1 and DR2 are the direct repeats, and the epsilon stem and loop structure in pgRNA is critical for the initiation of DNA replication. (B) The open reading frames of four genes are shown.( 1 ) (C) Major transcripts of HBV are shown. Enh1 positively regulates three transcripts, and Enh2 mainly contributes to transcription of pgRNA and PreC‐C mRNA.( 9 )

The X‐ORF is located downstream to Enh I and is partly overlapped by the P ORF at the N‐terminal, the PreC ORF and several cis‐elements of the PreC‐C promoter at the C‐terminal (Fig. 1). Therefore mutations in the C‐terminal portion may result in mutations of HBx and the cis‐elements at the same time. The X gene is transcribed independently from the other viral transcripts under the control of Enh I and X promoter. Enh I is responsive to many extracellular signals including 12‐O‐Tetradecanoylphorbol‐13‐acetate (TPA), Okadaic acid, IL‐6, and genotoxic stimuli that are important in an acute inflammatory response and cell proliferation in the liver.( 2 , 3 , 11 ) Furthermore Enh1 (and X promoter) is augmented by HBx, implying that the X gene is apparently under autoregulation.( 12 )

Detection and subcellular localization of HBx have long been controversial because of the quality of anti‐HBx antibodies. The reports on analysis of pX in Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus (WHV)‐infected woodchuck liver clearly demonstrated the amounts of pX in the range of 103−104 having the short and long half‐lives, the latter of which reflected that of pX in nuclear matrix.( 13 , 14 ) HBx in transient overexpression systems (around 105−106 molecules per transfected cell) is mainly in cytoplasm attached to membranes and its small portion in the nucleus.( 3 , 15 ) HBx has been reported to retain a nuclear export signal (NES), which binds Crm1, a critical factor for nuclear export,( 16 , 17 ) and HBx interacts with some transcription factors such as p53( 18 , 19 ) and Smad4,( 20 ) suggesting that HBx may modulate shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm.( 17 , 20 )

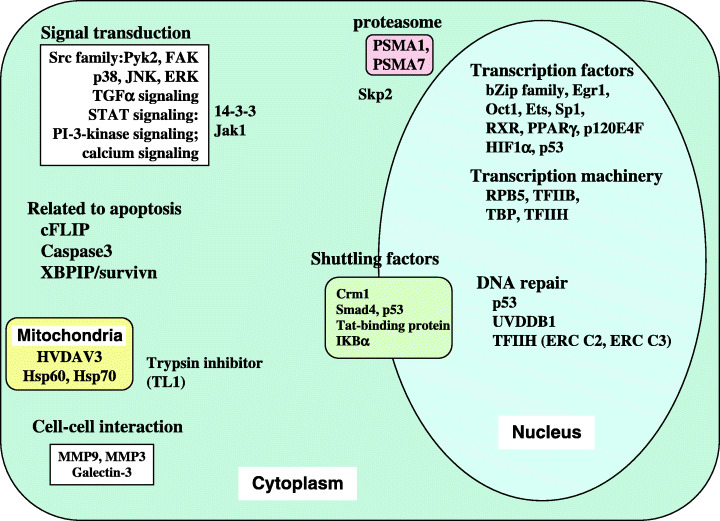

X protein has no homology to host proteins but shares homology to the other mammalian hepadnavirus pXs. The structure of HBx has been studied and the recombinant HBx has been reported by several groups, but no crystal model of HBx is available, probably reflecting that it is unstructured.( 2 ) HBx has been regarded as a multifunctional viral regulator that has been reported to modulate a wide variety of host functions (Fig. 2). A variety of the interacting partners of HBx have been identified and evaluated, but in some cases its partners have not been assessed (Fig. 2).( 2 , 3 )

Figure 2.

Host factors and functions modulated by HBx. The reported HBx‐interacting factors are shown. The functions and the targets shown in the white box are modulated by HBx. No HBx‐interacting partner related to these factors has been specified and HBx augments transcription of the factors. Some factors are described in previous reviews,( 2 , 3 ) and the HBx‐interacting proteins Skp2, p120E4F, and cFLIP were recently reported.( 70 , 71 , 72 )

The ‘transactivation’ function of HBx has been widely studied to elucidate the modulated expression of the HBV genes and host genes that include the genes that are critical or important for cell proliferation, cell cycle progress, acute immune response, protein degradation pathway, genetic stability, cell apoptosis, and also those involved in tissue organization (Fig. 2). Actually, some transcription activators including the leucine zipper family,( 21 ) p53( 18 , 19 ) and Smad4( 20 ) have been found to modulate gene expression by directly interacting with HBx in vivo and in vitro. Some DNA cis‐elements such as AP1, NFkB, SRE, and Sp1 were defined to be responsive to HBx using the reporter assays in vivo.( 2 , 3 , 22 ) However, it became clear that the defined cis‐elements are actually X‐responsive in certain contexts of promoters but not in the different promoters, and that the major of contributing cis‐element(s) in the strong promoters is usually X‐responsive.( 3 , 22 ) These results can not be explained solely by the suggestion that HBx transactivates transcription by interacting with transcription factors. In a different approach to decoding the apparent enigma, we first succeeded to identify a common subunit of RNA polymerases, RPB5, as a nuclear HBx‐interacting factor.( 23 ) By transcription assays using reporters in vivo, we found that HBx retains the coactivation function because it can augment activated transcription (transcription activated by transcription factors), but not basal transcription (transcription with basic promoter).( 24 ) Furthermore, activated transcription with HeLa nuclear extracts was further coactivated by the purified HBx in vitro. The involvement of general transcription factors in transcriptional modulation of HBx has been independently reported by Hahiv et al.( 25 ) Using a variety of truncation and substituted mutants of HBx, we mapped the coactivation domain within the C‐terminal, two thirds of which (aa 51–138), is identical to that of the ‘transactivation’. In contrast, the N‐terminal of HBx has the ability to down regulate ‘transactivation’, and was defined as the negative regulatory domain.( 26 )

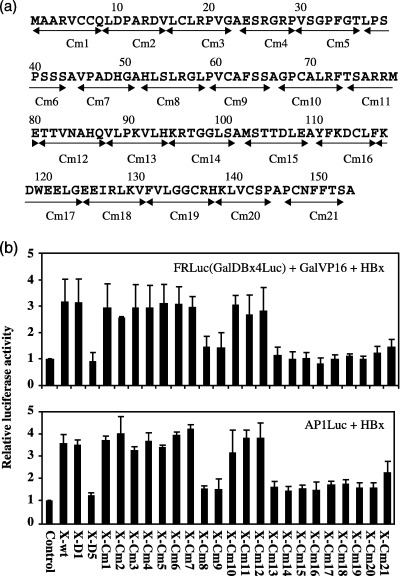

Recently Tang H et al. scanned the critical sequences of HBx for the coactivation using a series of clustered alanine‐substitution mutants (Fig. 3a).( 27 ) Two separate sequences within the coactivation domain were identified to be crucial for coactivation and exactly the same sequences were required for ‘transactivation’. These results strongly support the notion that the apparent ‘transactivation’ might be due to the coactivation of HBx as proposed in the previous report (Fig. 3b).( 24 , 27 ) The function of RPB5 in activated transcription has been analyzed in some parts( 28 ) but remains to be further explored. The transrepression of HBx was reported by inhibiting the p53‐dependent transcriptional activation,( 19 , 29 ) indicating the importance of the p53‐binding ability in regulating the p53‐dependent regulatory pathways. Also the other mechanism may be involved in the repression by HBx.( 30 ) HBx may modulate both transcriptional activation and repression because some transcription factors and/or transcription cofactors are involved in positive and negative ways to transcription in different promoters in different cells.

Figure 3.

Mapping of the HBx sequences necessary for coactivation and ‘transactivation’. (a) The amino acid sequence of HBx and a library of the clustered alanine substitution mutants (Cm1–Cm21) are shown. Each HBx‐Cm mutant harbors six or seven amino acid substitutions in a row.( 27 ) Transient expression of the HBx‐Cm mutants was similar to that of the wild HBx.( 27 ) (b) Transcription assay in vivo using luciferase reporters. Top is the coactivation assay. HepG2 cells were transiently introduced by pGalVP16 expressing the transactivator, pFR‐luc harboring the DNA‐binding sites for Gal4 and the luciferase gene, and the HBx expression plasmid. Control is the vacant plasmid, HBx‐D1 (aa 51–154) harbors the coactivation domain, and HBx‐D5 (aa 1–50) includes the negative regulatory domain. Bottom is the ‘transactivation’ assay using AP1‐Luc reporter and the HBx expression plasmid. A series of mutants, X‐Cm1 to X‐Cm21, are shown in (a). The results were according to the report by Tang et al.( 27 )

X protein has been reported to retain a variety of functions in addition to the coactivation function. Liang's group demonstrated the interaction between HBx and proteasome subunits that is necessary for ‘transactivation’ of HBx and for efficient HBV replication.( 31 , 32 ) The outcome of the interaction may suppress the process of antigen presentation in HBV‐infected cells. Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is another target of HBx because it directly binds DDB1( 33 ) and Xeroderma pigmentosa B (XBP) or Xeroderma pigmentosa D (XPD) helicase in general transcription factor IIH (TFIIH).( 34 ) The interaction may facilitate hepatocarcinogenesis in the presence of genotoxic stimuli, although the direct effect of HBx on NER reaction in vitro is not shown. Schneider's group reported several effects of HBx to modulate signaling pathways of protein kinases.( 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ) They proposed that HBx could augment the Src kinase family, including cytosolic calcium‐dependent proline rich tyrosine kinase (Pyk2) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK). The activation of a cytoplasmic calcium signaling pathway was argued to trigger the activation cascade of these kinases, which might sensitize cells to apoptosis in the presence of TNF‐α and also be critical in HBV replication.( 36 , 37 ) However, no direct partner of HBx in the activation of the calcium signaling pathway still remains obscure (Fig. 2). Several groups reported HBx directly interacts with mitochondria or mitochondrial proteins. These interactions seem to alter the trans membrane potential and enhance HBx‐mediated apoptosis.( 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 )

The biological role of HBx in HBV replication. X ORF is phylogenically conserved among mammalian hepadnavirus genomes, strongly indicating that HBx has some biological roles to facilitate or augment the viral life cycle. One possibility is a positive role of HBx on viral replication. Although several aspects of HBx have been explored by transgenic models and the stable or transient expression of HBx in different cell lines, the role of HBx in HBV replication has not been analyzed since the replication systems of HBV and WHV, replicons, was made available in the early 1990s (Fig. 1). Blum et al. constructed an expression plasmid of the 1.2 genome‐unit of HBV DNA with or without a single substitution that resulted in a termination at the 8th codon of X‐ORF, but has no effect on Pol‐ORF( 42 ) and evaluated the effect of HBx on HBV replication in Huh7 cells. A similar construct of a 1.2 genome‐unit WHV DNA with wild or mutant X‐ORF was circularized and introduced to woodchuck livers by injection.( 43 , 44 )

Chen et al. observed WHV infection in the woodchuck injected with the wild WHV DNA but not with the mutated X‐ORF.( 43 ) The result clearly demonstrates the essential role of X protein in WHV proliferation. In contrast, Blum et al. reported that HBV replication was observed both with the wild and X‐defective WHV DNA in Huh7 cells and in rat primary hepatocytes, concluding that HBx is not central to the viral life cycle.( 42 ) Later a similar result was also reported by Zheng et al. ( 45 ) These results with the HBV replicon systems are apparently different to the critical role of X protein in WHV replication in woodchucks, however, the experiments with the HBV replicons were addressed in the cells cultured in vitro. In the transgenic mice harboring the wild and X‐defective replicons, the positive contribution of HBx in HBV replication was reported.( 46 ) Later Bouchard MJ et al. demonstrated the strong contribution of HBx in HBV replication in HepG2 cells, since HBV replication with the wild HBV replicon was 5–10 times more efficient than that with the X‐ORF (–) mutant one.( 47 ) HBx was reported to increase the level of calcium in cells, which might be stimulatory for HBV replication because the treatment with drugs like gliotoxin and glibenclimide that augment cytoplasmic calcium ion partially rescued the HBV replication of the X‐deficient replicon. They argued that the role of HBx to stimulate HBV replication is not at the level of transcription of pgRNA but at the level of DNA replication. The detected amount of pgRNA core covered with viral capsids (assembled core) using the wild replicon is not much different to that with the X‐deficient replicon.( 42 ) They found that phosphorylation of the HBV core is critical for capsid assembly, which is required for the efficient assembly of pgRNA in replicating intermediate complexes.( 48 )

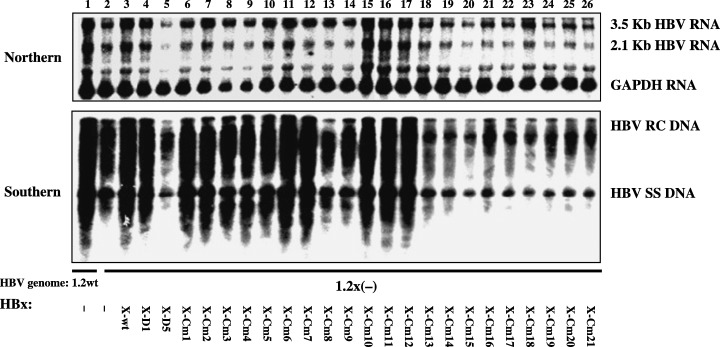

Recently the same question was addressed by Tang et al. who confirmed the stimulatory role of HBx in HBV replication.( 27 ) HBV replication was reduced by three times with the X‐deficient HBV replicon, compared with the wild one in HepG2 cells. Tang et al. found that the ectopically expressed HBx could augment HBV replication with the X‐deficient replicon to the level of the wild one, clearly indicating that the ectopical HBx can complement in trans to stimulate HBV replication. HBx stimulated the 3.5 kb transcript (including pgRNA) and the relaxed circle DNA at the similar extent (Fig. 4). As HBx can complement in trans, Tang et al. dissected the critical region of HBx for the stimulatory role in HBV replication and identified that the HBx‐D1 harboring the coactivation domain (aa 51–154) was sufficient to stimulate HBV replication. Next they addressed the amino acid sequences required for the stimulation of HBV replication by scanning them with the HBx‐cm library (Fig. 3a). This demonstrated that the two separate sequences within the coactivation domain were indispensable to augment both HBV transcription and replication. Interestingly the two sequences of HBx that were critical for augmentation of HBV transcription and replication were found to be identical to those required for the coactivation function (3, 4).( 27 ) Two lines of evidence strongly support the notion that the coactivation function of HBx mainly contributes to the stimulatory role in HBV replication. First, the augmentation of HBV transcription is always observed in parallel to HBV replication, strongly suggesting that the stimulation of HBV replication is mainly due to the enhanced transcription by HBx. Second, the sequences of HBx required for augmented HBV replication are the same as those for the transcription coactivation. As the synthesis of pgRNA is the first regulatory step of HBV replication, the transcriptional coactivation by HBx enhances HBV transcription including pgRNA synthesis that, in turn, augments HBV replication. The conclusion by Tang et al. is clearly different from the direct role of HBx in HBV replication reported by the previous studies.( 46 , 47 )

Figure 4.

Mapping of the HBx sequences required for the stimulation effect on HBV transcription and replication. HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the wild‐type HBV construct payw1.2 (1.2wt, lane 1) or the HBx‐minus HBV construct payw (42) 7 (1.2X(–), lanes 2–26) plus empty vector control (–, lanes 1 and 2), full‐length HBx expression vector (X‐wt, lane 3), different truncated HBx expression vectors (X‐D1, lane 4; X‐D5, lane 5), or a series of clustered mutated HBx expression vectors (X‐Cm1 to X‐Cm21, lanes 6–26, respectively). Top is RNA (Northern) hybridization analysis of HBV transcripts. The glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript was used as an internal control for RNA loading per lane. Bottom is DNA (Southern) hybridization analysis of HBV replication intermediates. HBV RC DNA, HBV relaxed circular DNA; HBV SS DNA, HBV single‐stranded DNA. The results were according to the report by Tang et al.( 27 )

Zhang et al. reported the involvement of proteasome in the stimulatory role of HBx in HBV transcription and replication.( 32 ) Their experiments demonstrated that HBx‐assisted enhancement of HBV transcription and replication is through the proteasome‐dependent pathway since inhibition of cellular proteasome activities enhanced HBV transcription and replication in an HBx‐dependent manner. Leupin reported that DDB1, the host factor involved in nuclear excision repair (NER), might be involved in the HBx‐dependent HBV transcription and replication, because the HBx mutant defective in the DDB1‐binding could not complement in trans, and the knock‐down of DDB1 reduced HBV transcription and replication with the wild HBV replicon. Interestingly, this effect was observed with HBx having the artificial NLS (nuclear localizing signal), but this was barely observed with the additional NES. This strongly suggests that the critical role of HBx in stimulating HBV transcription and replication might occur in the nucleus, where DDB1 is expected to function.( 49 ) These HBx‐interacting factors, proteasome and DDB1, were shown to affect not only HBV replication but also pgRNA transcription of HBV. It remains to be elucidated whether or not these host factors affect the HBV replication and transcription. The stimulatory effect of HBx on HBV transcription and replication was observed in HepG2 but not clearly in Huh7 cells (unpublished data Tang et al., 2003).( 49 ) The cell line‐specific requirement of HBx for efficient HBV transcription and replication suggests an interesting possibility that HBx might be critical for HBV transcription and/or replication in human primary hepatocytes. If this was the case, the apparent different results on the role of X protein with WHV and HBV would be due to the different cells they used to address the issue.

HBx in cellular transformation. The oncogenic property of HBx remains controversial in this field. Two experimental approaches have been applied to address the oncogenic property of HBx, transgenic mice expressing HBx in the liver and the cellular transformation assay using immortal rodent cells.

Firstly, Kim et al. showed the tumorigenic property of HBx when their transgenic male mice expressing HBx in liver developed HCC.( 50 ) The construct harbors the X gene regulation unit including Enh1, the X promoter, X‐ORF and the polyA signal (Fig. 1).( 50 ) Many groups also constructed the HBx‐expressing transgenic mice, all of which failed to develop HCC( 45 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ) except the case by Yu DY et al. whose construct harbored the X gene regulation unit as the previous one.( 55 ) The design of the X gene regulation unit might not be the reason for the failure to develop HCC because the same design was applied in other groups. The reason for the different results among the transgenic mice expressing HBx in liver remains unclear at present. In contrast, with the direct involvement of HBx in hepatocarcinogenesis, two groups found the pivotal role of HBx in transgenic mice in which the development of HCC was observed only in the presence of cMyc expression or carcinogens. They argued that HBx alone is not carcinogenic, but helps tumorigenesis collaborating with genotoxic stresses and/or oncogenes.( 51 , 52 , 56 )

The second experimental approach is the cellular transformation assay using immortal cell lines. Koike's group reported the transforming ability of HBx in NIH3T3 by introducing HBV DNA with DNA transfection.( 57 ) Following the same method, no positive result could be obtained in the other groups including ours (unpublished data, Nomura T, 2002). The transforming ability of HBx was examined with mouse hepatocyte‐derived cell lines from the TGFα transgenic mouse or immortalized by SV40 Large T antigen.( 58 , 59 , 60 ) In their reports the inefficient transformation of cells were observed, but some transformed clones expressing HBx were reported to form colonies in soft agar and tumors in nude mice.( 59 , 60 ) But later the expression of HBx alone was reported to show apparent antitransforming ability in rat embryo fibroblasts due to the induction of cell apoptosis.( 61 , 62 ) Cellular senescence and crisis are the host defense mechanisms to suppress tumorigenesis. Knowledge of cellular senescence has accumulated during the last decade demonstrating the profound difference between mouse and human systems in several aspects,( 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 ) especially the critical contribution of telomere checkpoint control in cellular senescence of human cells. Overcoming processes of active oncogene‐induced senescence (OIS) is critical for cancer formation, not only in vitro but also in vivo.( 64 , 65 , 66 ) Therefore, the effect of some factors that may facilitate to overcome cellular senescence would be examined in human cells.

We started to address the effect of HBx on cellular immortalization and/or transformation with human primary and immortalized cells (Oishi N et al. submitted) as no report on this address in human cells is available at present. We applied the human fibroblasts, BJ and TIG3 cells, and the immortalized clones of the BJ cells by human telomere reverse transcriptase (hTERT), although it is best for this purpose to use human hepatocytes that are difficult to access for experimental approaches. The expression retroviruses of the wild and several mutants of HBx were prepared and infected in these human cells. The cells expressing HBx were isolated and subjected to several analyzes (Table 1). The wild HBx‐expressing BJ cells or TIG3 cells stopped cell proliferation after certain PDs (population doubling), as the control cells did. The hTERT‐immortalized BJ and TIG3 cells did not show any change by the stable expression of wild HBx, indicating that HBx by itself can neither immortalize nor transform the human primary or hTERT‐immortalized cells (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of HBx on cellular transformation in human cells

| Retro virus vector | Cells: | Immortalization † | Colony formation ‡ | Tumor formation§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BJ | TIG3 | BJ‐hTERT | BJ‐hTERT | BJ‐hTERT | ||

| Empty Vector | – | – | + | – | nt | |

| HBx | – | – | + | – | nt | |

| HBx‐D1 | – | – | + | nt | nt | |

| HBx‐D5 | – | – | + | nt | nt | |

| RASv12 | – | – | – | – | nt | |

| RASv12 + HBx | – | – | + | + | 4/8 | |

| RasV12 + HBx‐D1 | – | – | + ¶ | – | 0/8 | |

| RasV12 + HBx‐D5 | – | – | – | – | 0/8 | |

| RasV12 + SV40LT + ST | nt | nt | + | + | 8/8 | |

By population doubling (PD) analysis;

‡ by sort agar assay;

1 × 106 cells were injected to 8‐week‐old female nude mice.

Growth rate is slower than the cells with those expressing RasV + HBx, and cellular senescence was observed to some extent. All results are by Oishi N, Masutomi K, Murakami et al. (submitted)

We examined next whether HBx retains the ability to overcome OIS by stably coexpressing active oncogene H‐Ras V12 and HBx in the hTERT‐immortalized human primary cells (RAS + HBx BJ‐hTERT). Active RAS caused cellular senescence within days, but RAS + HBx BJ‐hTERT kept cell proliferation more than 80 PD, indicating that HBx contributed to overcoming OIS in the cells (Table 1). In the PD analysis, the coactivation domain alone seemed to be enough to overcome OIS as RAS + HBx‐D1 BJ‐hTERT expressing the coactivation domain of HBx could overcome OIS. However, RAS + HBx‐D1 BJ‐hTERT was neither colonigenic nor tumorigenic although the RAS + HBx BJ‐hTERT was found to form colonies in soft agar and tumors in nude mice (Table 1). The negative regulatory domain in the full‐length HBx seems to be necessary for the anchorage‐independent proliferation. This finding is the first with human immortalized cells to demonstrate the helping role of HBx with active oncogene in tumor formation. To confirm the result, the hTERT‐immortalized BJ cells was scanned with the HBx‐Cm library in the presence of active RAS.( 27 ) The HBx‐cm‐mutants within the negative regulatory domain exhibited the ability to afford the phenotype like HBx‐D1, namely immortal in the PD analysis, but anchorage‐dependent in the soft agar assay. In contrast, the HBx‐cm‐mutants within the coactivation domain showed either the wild‐type phenotype or no ability to overcome OIS. The sequences necessary for overcoming OIS seem not to be the same as those necessary for coactivation (Fig. 3, unpublished data, 2006). The result may imply that other functions or the ability of HBx to interact with other factors might be critical to overcome OIS. Further fine mapping of the sequences necessary for the anchorage‐independent growth of cells and the other analyses may reveal the molecular mechanism of HBx involved in overcoming OIS. However, this result in the experimental model with human immortalized fibroblasts may not reflect the biological role of HBx in the liver, because overcoming processes of OIS seems to vary with tissue and tumor type.( 64 ) The role of HBx should therefore, be addressed with immortalized human hepatocytes in the near future.

Conclusion

Hepatocellhlar carcinoma happen in the background of chronic liver inflammation that correlates with the extent of HBV gene expression and replication, and host immune response. HBx primarily serves to augment HBV gene expression and replication as the transcriptional coactivator collaborating with host transcription factors. At the same time, HBx could stimulate transcription of host genes related to cell proliferation and inflammation that may afford better cellular environments for HBV replication. A better environment for HBV proliferation also augments host factors that relate to host defense response and apoptosis of cells. However, several maneuvers of HBV might escape HBV from host immune surveillance, such as the massive production of S antigen and intercellular transmission of HBV CCC molecules. The ability of HBx to overcome OIS may contribute to form tumors in the liver by keeping cell proliferation of cancer cells, although target host function(s) of HBx in overcoming OIS remains elucidated. These two different functions of HBx could be synergistic, since both of the inflammatory stimuli and oncogenic stimuli may positively regulate HBx expression that is under the autoregulation. The other documented functions of HBx may modulate host functions collaborating with the two critical functions in HBV proliferation, host immune response, or cellular immortalization and/or the transforming process. Knock‐down of HBx expression by si‐ or sh‐RNA methods has been reported to down‐regulate HBV transcription and replication.( 67 , 68 , 69 ) Down‐regulation of HBx might reduce HBV gene expression and replication and might also reduce the ability to overcome OIS. It is natural to expect that HBV replication and tumorigenic incidence would be reduced or prevented by the knock‐down of HBx or by specific inhibitors of HBx.

Acknowledgment

We thank all the members of the Division of Molecular Biology, Cancer Research Institute who contributed to the results in this review. This work was supported in part by Grants‐in‐Aid for scientific research and development (B) 17390091, and a Grant‐in‐Aid for scientific research in the priority area of oncogenesis (C) 18012018, from the Ministry of Education, Sports, Culture, and Technology, Japan.

References

- 1. Arbuthnot P, Kew M. Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Exp Pathol 2001; 82: 77–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murakami S. Hepatitis B Virus X protein: structure, function biology. Intervirol 1999; 42: 82–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murakami S. Hepatitis B Virus X protein: a multifunctional regulatory protein. J Gastroenterol 2001; 36: 651–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kajino K, Aoki H, Hino O. Genomic instability involved in virus‐related hepatocarcinogenesis. Intervirol 1995; 38: 170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chisari FV. Hepatitis B virus transgenic mice: models of viral immunobiology and pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1996; 206: 149–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Araki K, Miyazaki J, Yamamura K et al. Expression and replication of hepatitis B virus genome in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989; 86: 207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seeger C, Mason WS. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2000; 64: 51–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yen TSB. Regulation of hepatitis B virus gene expression. Semin Virol 1993; 4: 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doitsh G. Enhancer I predominance in hepatitis B virus gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 1799–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nassal M, Schaller H. Hepatitis B virus replication. Trends Microbiol 1993; 1: 221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murakami S, Cheong JH, Kaneko S et al. Transactivation of human hepatitis B virus X protein, HBx operates through a mechanism distinct from protein kinase C and okadaic acid activation pathways. Virol 1994; 199: 243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murakami S, Cheong JH, Kaneko S et al. Autoregulation of human hepatitis B virus X gene. In: Nishioka, K , Suzuki, H , Mishiro, S , Oda, T , eds. Viral Hepatitis and Liver Diseases. Tokyo: Springer Verlauf, 1994; 743–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dandri M, Schirmacher P, Rogler CE et al. Woodchuck hepatitis virus X protein is present in chronically infected woodchuck liver and woodchuck hepatocellular carcinomas which are permissive for viral replication. J Virol 1996; 70: 5246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dandri M, Petersen J, Rogler CE et al. Metabolic labeling of woodchuck hepatitis B virus X protein in naturally infected hepatocytes reveals a bimodal half–life and association with the nuclear framework. J Virol 1998; 72: 9359–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nomura T, Lin Y, Murakami S et al. Human Hepatitis B virus X protein is detectable in nuclei of transfected cells, and active for transactivation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999; 1453: 330–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forgues M, Marrogi AJ, Wang XW et al. Interaction of the hepatitis B virus X protein with the Crm1‐dependent nuclear export pathway. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 22 797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forgues M, Difilippantonio MJ, Wang XW et al. Involvement of Crm1 in hepatitis B virus X protein‐induced aberrant centriole replication and abnormal mitotic spindles. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23: 5282–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elmore LW, Hancock AR, Harris CC et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein and p53 tumor suppressor interactions in the modulation of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94: 14 707–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin Y, Nomura T, Murakami S et al. The transactivation and p53‐interaction functions of HBx are mutually interfering but distinct. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 5137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee DK, Park SH, Kim SJ et al. The hepatitis B virus encoded oncoprotein pX amplifies TGF‐beta family signaling through direct interaction with Smad4: potential mechanism of hepatitis B virus‐induced liver fibrosis. Genes Dev 2001; 15: 455–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrisani OM, Barnabas S. The transcriptional function of the hepatitis B virus X protein and its role in hepatocarcinogenesis. Int J Oncol 1999; 15: 373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cross JC, Wen P, Rutter WJ et al. Transactivation by hepatitis B virus X protein is promiscuous and dependent on mitogen‐activated cellular serine/threonine kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 8078–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheong JH, Yi MK, Murakami S et al. Human RPB5, a subunit shared by eukaryotic nuclear polymerases, binds human hepatitis B virus X protein and may play a role in X transactivation. EMBO J 1995; 14: 143–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin Y, Reoder RG, Murakami S et al. The HBV X protein is a co‐activator of activated transcription that modulates the transcription machinery and distal binding activators. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 27 097–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haviv I, Vaizel D, Shaul Y. pX, the HBV‐encoded coactivator, interacts with components of the transcription machinery and stimulates transcription in a TAF‐independent manner. EMBO J 1996; 15: 3413–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murakami S, Cheong JH, Kaneko S et al. Human hepatitis B virus X gene encodes a regulatory domain which represses transactivation of X protein. J Biol Chem 1994; 269: 15 118–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tang H, Delgermaa L, Murakami S et al. The transcriptional transactivation function of HBx protein is important for its augmentation role in hepatitis B virus replication. J Virol 2005; 79: 5548–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Le TTT, Zhang S, Murakami S et al. Mutational analysis of human RNA polymerase II subunit 5 (RPB5): the residues critical for interactions with TFIIF subunit RAP30 and Hepatitis B Virus X protein. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2005; 138: 215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Doitsh G, Shaul Y. HBV transcription repression in response to genotoxic stress is p53‐dependent and abrogated by pX. Oncogene 1999; 18: 7506–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ahn JY, Chung EY, Jang KL et al. Transcriptional repression of p21 (waf1) promoter by hepatitis B virus X protein via a p53‐independent pathway. Gene 2001; 275: 163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Z, Torii N, Liang TJ et al. Structural and functional characterization of interaction between hepatitis B virus X protein and the proteasome complex. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 15157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Z, Protzer U, Liang J et al. Inhibition of cellular proteasome activities enhances hepadnavirus replication in an HBX‐dependent manner. J Virol 2004; 78: 4566–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee TH, Elledge SJ, Butel JS. Hepatitis B virus X protein interacts with a probable cellular DNA repair protein. J Virol 1995; 69: 1107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jia L, Wang XW, Harris CC. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits nucleotide excision repair. Int J Cancer 1999; 80: 875–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klein NP, Schneider RJ. Activation of Src family kinases by hepatitis B virus HBx protein and coupled signaling to Ras. Mol Cell Biol 1997; 17: 6427–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bouchard MJ, Wang LH, Schneider RJ et al. Calcium signaling by HBx protein in hepatitis B virus DNA replication. Science 2001; 294: 2376–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bouchard MJ, Wang L, Schneider RJ. Activation of focal adhesion kinase by hepatitis B virus HBx protein: Multiple functions in viral replication. J Virol 2006; 80: 4406–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Takada S, Shirakata Y, Koike K et al. Association of hepatitis B virus X protein with mitochondria causes mitochondrial aggregation at the nuclear periphery, leading to cell death. Oncogene 1999; 18: 6965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huh KW, Siddiqui A. Characterization of the mitochondrial association of hepatitis B virus X protein, HBx. Mitochondrion 2002; 1: 349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanaka Y, Kanai F, Omata M et al. Interaction of the hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) with heat shock protein 60 enhances HBx‐mediated apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004; 318: 461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang SM, Sun DC, Wang SQ et al. HBx protein of hepatitis B virus (HBV) can form complex with mitochondrial HSP60 and HSP70. Arch Virol 2005; 150: 1579–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blum HE, Zhang ZS, Wands JR. Hepatitis B virus X protein is not central to the viral life cycle in vitro. J Virol 1992; 66: 1223–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen HS, Kaneko S, Miller RH et al. The woodchuck hepatitis virus X gene is important for establishment of virus infection in woodchucks. J Virol 1993; 67: 1218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zoulim F, Saputelli J, Seeger C. Woodchuck hepatitis virus X protein is required for viral infection in vivo . J Virol 1994; 68: 2026–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zheng Y, Johnson DL, Ou JH. Regulation of hepatitis B virus replication by the ras‐mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Virol 2003; 77: 7707–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu Z, Yen TS, Ou JH et al. Enhancement of hepatitis B virus replication by its X protein in transgenic mice. J Virol 2002; 76: 2579–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bouchard MJ, Puro RJ, Schneider RJ et al. Activation and inhibition of cellular calcium and tyrosine kinase signaling pathways identify targets of the HBx protein involved in hepatitis B virus replication. J Virol 2003; 77: 7713–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Melegari M, Wolf SK, Schneider RJ. Hepatitis B virus DNA replication is coordinated by core protein serine phosphorylation and HBx expression. J Virol 2005; 79: 9810–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leupin O, Bontron S, Strubin M et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein stimulates viral genome replication via a DDB1‐dependent pathway distinct from that leading to cell death. J Virol 2005; 79: 4238–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim CM, Koike K, Jay G et al. HBx gene of hepatitis B virus induces liver cancer in transgenic mice. Nature 1991; 351: 317–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee TH, Finegold MJ, Butel JS et al. Hepatitis B virus transactivator X protein is not tumorigenic in transgenic mice. J Virol 1990; 64: 5939–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Terradillos O, Billet O, Buendia MA et al. The hepatitis B virus X gene potentiates c‐myc‐induced liver oncogenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene 1997; 14: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reifenberg K, Lohler J, Schlicht HJ et al. Long‐term expression of the hepatitis B virus core‐e‐ and X‐proteins does not cause pathologic changes in transgenic mice. J Hepatol 1997; 26: 119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hu Z, Zhang Z, Liang TJ et al. Altered proteolysis and global gene expression in hepatitis B virus X transgenic mouse liver. J Virol 2006; 80: 1405–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu1 DY, Murakami S, Lee KK et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the transgenic mice expressing hepatitis B virus X‐protein. J Hepatol 1999; 31: 123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Madden CR, Finegold MJ, Slagle BL. Hepatitis B virus X protein acts as a tumor promoter in development of diethylnitrosamine‐induced preneoplastic lesions. J Virol 2001; 75: 3851–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shirakata Y, Kawada M, Koike K et al. The X gene of hepatitis B virus induced growth stimulation and tumorigenic transformation of mouse NIH3T3 cells. Jpn J Cancer Res 1989; 80: 617–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Oguey D, Dumenco LL, Fausto N et al. Analysis of the tumorigenicity of the X gene of hepatitis B virus in a nontransformed hepatocyte cell line and the effects of cotransfection with a murine p53 mutant equivalent to human codon 249. Hepatology 1996; 24: 1024–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Seifer M, Gerlich WH. Increased growth of permanent mouse fibroblasts in soft agar after transfection with hepatitis B virus DNA. Arch Virol 1992; 126: 119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Seifer M, Hohne M, Gerlich WH et al. In vitro tumorigenicity of hepatitis B virus DNA and HBx protein. J Hepatol 1991; 13 (Suppl 4): S61–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schuster R, Gerlich WH, Schaefer S. Induction of apoptosis by the transactivating domains of the hepatitis B virus X gene leads to suppression of oncogenic transformation of primary rat embryo fibroblasts. Oncogene 2000; 19: 1173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schuster R, Hildt E, Schaefer S et al. Conserved transactivating and pro‐apoptotic functions of hepadnaviral X protein in ortho‐ and avihepadnaviruses. Oncogene 2002; 21: 6606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim YC, Song KS, Ryu WS et al. Activated ras oncogene collaborates with HBx gene of hepatitis B virus to transform cells by suppressing HBx‐mediated apoptosis. Oncogene 2001; 20: 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Artandi SE, DePinho RA. Mice without telomerase: what can they teach us about human cancer? Nat Med 2000; 6: 852–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. Cancer: crime and punishment. Nature 2005; 436: 636–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Braig M, Lee S, Schmitt CA et al. Oncogene‐induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development. Nature 2005; 436: 636–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shlomai A, Shaul Y. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus expression and replication by RNA interference. Hepatology 2003; 37: 764–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hamasaki K, Nakao K, Eguchi K et al. Short interfering RNA‐directed inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication. FEBS Lett 2003; 543: 51–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chan DW, Ng IO. Knock‐down of hepatitis B virus X protein reduces the tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Pathol 2006; 208: 372–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kalra N, Kumar V. The X protein of hepatitis B virus binds to the F box protein Skp2 and inhibits the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of c‐Myc. FEBS Lett 2006; G580: 431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rui E, Moura PR, Kobarg J et al. Interaction of the hepatitis B virus protein HBx with the human transcription regulatory protein p120E4F in vitro . Virus Res 2006; 115: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim KH, Seong BL. Pro‐apoptotic function of HBV X protein is mediated by interaction with c‐FLIP and enhancement of death‐inducing signal. EMBO J 2003; 22: 2104–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]