Abstract

Aberrant DNA methylation is known as an important cause of human cancers, along with mutations. Although aberrant methylation was initially speculated to be similar to mutations, it is now recognized that methylation is quite unlike mutations. Whereas the number of mutations in individual cancer cells is estimated to be ∼80, that of aberrant methylation of promoter CpG islands reaches several hundred to 1000. Although mutations of a specific gene are very few in non‐cancerous (thus polyclonal) tissues (usually at 1 × 10−5/cell), aberrant methylation of a specific gene can be present up to several 10% of cells. Mutagenic chemicals and radiation are well‐known inducers of mutations, whereas chronic inflammation is deeply involved in methylation induction. Although mutations are induced in mostly random genes, methylation is induced in specific genes depending on tissues and inducers. Methylation is potentially reversible, unlike mutations. These characteristics of methylation are opening up new fields of application and research. (Cancer Sci 2009)

Aberrant DNA methylation is deeply involved in human carcinogenesis,( 1 , 2 , 3 ) and is often described as “genome‐overall hypomethylation and regional hypermethylation”. Genome‐overall hypomethylation was discovered in the early 1980s( 4 , 5 ) and has been shown to induce genomic instability and promote carcinogenesis.( 6 , 7 , 8 ) Regional hypermethylation denotes methylation of normally unmethylated CpG islands (CGI) and, in particular, methylation of a promoter CGI is known to silence its downstream gene by multiple mechanisms, including aberrant nucleosome formation.( 9 , 10 ) Inactivation of a tumor‐suppressor gene was first discovered for RB in 1993,( 5 , 11 ) and now a wide variety of tumor‐suppressor genes, including CDKN2A (p16), MLH1, and CDH1 (E‐cadherin), are known to be inactivated by aberrant methylation.( 2 ) In many types of cancers, aberrant promoter methylation is frequently observed and in some types of cancers, such as gastric cancers, aberrant methylation is more frequent than mutations in inactivating mechanisms of specific tumor‐suppressor genes.( 12 )

In the 1990s, investigators found that tumor‐suppressor genes can be inactivated by aberrant methylation of promoter CGI, and that most CGI analyzed by conventional methods were kept unmethylated, even in cancers. This made them think that genes with aberrant methylation of promoter CGI were tumor‐suppressor genes. Some investigators were inspired that they could identify tumor‐suppressor genes if they could identify aberrant methylation by genome‐wide screening methods.( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ) Actually, these methods contributed to the identification of important CGI in diagnostic purposes and isolation of tumor‐suppressor genes.( 3 ) In addition, the fact that aberrant methylation of promoter CGI is an alternative to a mutation for inactivation of tumor‐suppressor genes made many investigators think that epigenetic alterations would share similar features with mutations in other aspects, such as their frequencies in cancer and non‐cancerous tissues, inducers, and target genes.

However, recent findings by high‐resolution genome‐wide analysis of DNA methylation and by many other approaches have shown that aberrant DNA methylation has many unique features different from mutations (here, point mutations and small base deletions) (Table 1). In this review, we will summarize the contrasts between these two kinds of alterations: aberrant DNA methylation and mutations.

Table 1.

Comparison between mutations and DNA methylation

| Mutation | DNA methylation | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of alterations per cancer cell | ∼80 | Several hundred to 1000 | ( 18, 23, 27, 28, 29, 30 ) |

| Frequency of alterations of a specific gene in non‐cancerous tissues | 10−5/cell, up to 10−3/cell | 0.1 to several % up to several 10% of cells | ( 44, 46 ) |

| Inducers | Mutagenic chemicals, radiation, oxygen radical | Chronic inflammation, aging | ( 45, 56 ) |

| Target gene | Random | Specific | ( 18, 27, 37, 61 ) |

| Reversibility | Irreversible | Reversible | ( 18, 61, 70, 71, 72, 73 ) |

Detailed explanations are in individual sections.

Number of alterations in a cancer cell

Recent use of high‐throughput sequencing and high‐resolution microarray technologies has illuminated detailed genetic and epigenetic alterations in cancer cells.

Assessment of the role of genetic alterations in carcinogenesis. The assessment of whether a specific sequence alteration is a mutation and what the role of a mutation is in carcinogenesis is relatively straightforward. If a possible sequence change is specifically present in cancer tissues but not in non‐cancerous tissues, it is a somatic mutation. If the mutation alters the amino acid sequence of an encoded protein, it is a candidate for a driver mutation.( 17 , 18 ) Comparison between the incidence of mutations with amino acid alteration and that of silent mutations can provide information on whether there is a selection bias for cells with a mutation of the gene in carcinogenesis. Mutations that drive the initiation, progression, or maintenance of a cancer are classified as driver mutations, and mutations that simply accompany carcinogenesis or are produced as a result of transformation are classified as passenger mutations.

Number of driver and passenger mutations in cancers. As high‐throughput sequencing becomes more powerful, a wider selection of genes has been analyzed for broader ranges of cancers. By sequencing more than 20 000 transcripts in breast and colon cancers, it was estimated that approximately 80 non‐silent mutations are present in a typical cancer, and that <15 genes are likely to be driver mutations.( 18 ) By sequencing of a wide variety of cancers for selected genes (518 protein kinases), it was shown that lung cancers harbor more mutations than colon and gastric cancers, and that one‐third of cancers did not have any somatic mutations in these kinases.( 17 ) The presence of a limited number of driver mutations and a large number of passenger mutations was confirmed in these studies.

Assessment of the role of “aberrant” methylation in carcinogenesis. In contrast to mutations, assessment of the biological significance of “aberrant” DNA methylation is very difficult. At least, the effect of methylation on gene silencing and the role of the silencing in carcinogenesis need to be assessed separately and precisely.

To assess the effect on gene silencing, the location of a methylated region and the CpG density of the region are critically important.( 19 , 20 ) The methylation status of promoters with high CpG density, namely promoter CGI, has a clear association with decreased transcription whereas that of promoters with low CpG density are unclear. Depending on the relative position against a transcription start site (TSS), the degree of association between DNA methylation and decreased gene expression is different. Methylation of a 200–300‐bp upstream region of a TSS has been known to be consistently associated with repressed transcription.( 1 , 2 , 3 , 21 ) The region is now known as a “nucleosome‐free region” (NFR), which lacks a nucleosome( 9 ) and whose DNA methylation leads to formation of nucleosome(s) and represses transcription.( 10 ) Recent genome‐wide studies also support the idea that methylation of NFR is consistently associated with low gene transcription.( 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 ) At the same time, methylation of a far upstream region and exon 1 can also be associated with decreased transcription via methylation of the NFR. On the other hand, methylation of a gene body is occasionally associated with increased gene expression.( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ) It is noteworthy that, even within a CGI, the methylation status of different regions is occasionally heterogeneous and investigators should analyze an appropriate region.( 3 )

Even if limited to DNA methylation that causes gene silencing, the role of the DNA methylation in carcinogenesis needs to be carefully assessed. As described below, there are hundreds to 1000 genes with methylation of their NFR in cancer cells, and it is likely that most of them are passengers. Also as described below, genes without expression in normal cells tend to become methylated in cancers, and such genes without expression are unlikely to be tumor‐suppressor genes. To establish a gene with methylation of its NFR in cancers as a tumor‐suppressor gene, we need mutation analysis of the gene in cancers and functional analysis of the gene after its transduction into cancer cells and expression at a physiological level and after its knock down in normal cells. Most tumor‐suppressor genes are known to be inactivated by homozygous mutation, by combination of methylation and mutation, or by methylation of all copies, and methylation is more frequent than mutations.( 26 )

Number of methylation of CGI in NFR in cancers. Detailed pictures of CGI aberrantly methylated in cancers are becoming clear by microarray analysis combined with methylated DNA immunoprecipitation or methylated‐CpG island recovery assay using methylated‐DNA binding domain proteins.( 23 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ) As normalization of signals obtained by microarray is still under development( 23 , 31 , 32 , 33 ) and CGI in various positions against TSS and various regions within CGI have been analyzed so far, it is difficult to compare different reports at this time.

According to our previous studies focusing on methylation of NFR in promoter CGI,( 23 , 34 ) large fractions of them were methylated in gastric cancer cell lines (Table 2). Although there is controversy about how methylation in cell lines reflects that in primary cancers,( 35 , 36 ) it seems safe to estimate that one‐third to one‐half of CGI methylated in cell lines are also methylated in primary cancers. We currently estimate that several hundred to 1000 NFR in promoter CGI are methylated in a primary cancer cell. If not limited to NFR, 216–848 of 27 800 CGI are reported to be methylated in primary lung squamous cell cancers.( 30 ) If limited to methylation of NFR that can be detected by re‐expression after treatment with a demethylating agent, the number decreases markedly, such as to less than 1/100.( 23 ) These show that a large number of NFR and other CGI are methylated in cancers, which is in line with pioneering studies.( 37 , 38 ) The large number is in sharp contrast to the number of mutations in a cancer.

Table 2.

Estimated number of methylated CpG islands (CGI)

| Cell lines | Nucleosome‐free region | CGI (not restricted to promoters) |

|---|---|---|

| Stomach cancer | 641–1205 of 9624 (6.6–12.5%) | 3768–7310 of 30 533 (12.3–23.9%) |

| Prostate cancer | 501–800 of 8930 (5.6–8.6%) | 5593–7638 of 34 405 (16.3–22.2%) |

| Breast cancer | 480–673 of 8866 (5.4–7.6%) | 4118–4755 of 34 424 (12.0–13.8%) |

The number of nucleosome‐free regions and CGI analyzed are different in individual experiments because the number of probes assessed as functional was different in each experiment.

Methylation of a specific gene in a large fraction of cells in non‐cancerous tissues

DNA methylation shows a sharp contrast to mutations also in the fraction of cells with an alteration of a specific gene in non‐cancerous tissues. Moreover, the degree of accumulation of aberrant DNA methylation can be associated with cancer risk.

Meaning of the fraction of cells with an alteration in cancer and non‐cancerous tissues. The fraction of cells with an alteration (mutation or methylation) of a specific gene is often compared between cancer and non‐cancerous tissues. However, the meaning of the fraction is entirely different in the two kinds of tissues.

Not to mention, a cancer develops after multiple processes of clonal selection (Fig. 1). In non‐cancerous tissues, no selection for a cell with an alteration has been imposed yet, and thus the fraction of cells with the alteration is mainly determined by the frequency with which the alteration is induced. The frequency can be affected by the overall exposure level to its inducers and by the susceptibility of individual genes to undergo an alteration. In actual analysis, the proportion of target cells, such as content of epithelial cells in a sample with epithelial and stromal cells, also affects the fraction of cells with an alteration.

Figure 1.

Epigenetic field for cancerization and clonal selection in cancer. Normal epithelium consists of cells with little aberrant methylation. By exposure to inducers of methylation, specific genes are methylated in minor fractions of cells. A cancer develops from one of the cells that has already accumulated silencing of driver genes. From the viewpoint of assessment of an effect of an inducer, analysis of non‐cancerous tissues provides overall information on the genes methylated, and that of a cancer provides information on the genes stochastically methylated in the very precursor cell and driver genes.

In contrast, in cancer tissues, an alteration responsible for clonal growth (driver) is present in all the cancer cells. Even if an alteration is not a driver, if the alteration has taken place before the clonal growth started, it is present in all the cancer cells. In actual analysis, cancer samples contain a large contamination of non‐cancer cells, and the fraction of cells with the alteration is mainly determined by the fraction of cancer cells in a sample. If an alteration is induced after initiation of clonal growth, it can be present in a fraction of cancer cells, and its overall fraction is determined by the fraction within cancer cells and by the fraction of cancer cells within a sample.

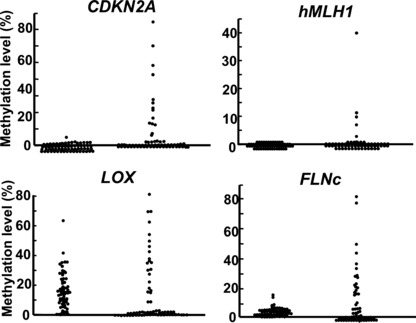

These theoretical considerations were substantiated by actual measurement of cells with methylation of specific genes in non‐cancerous and cancer tissues of gastric cancer patients (Fig. 2) and esophageal cancer patients.( 39 , 40 ) The methylation level, which reflects the fraction of DNA molecules with methylation and thus the fraction of cells with the methylation, shows a unimodal distribution in non‐cancerous tissues, especially for the weak tumor‐suppressor gene LOX and the marker gene FLNc.( 41 ) It shows a “bimodal” distribution, namely zero or positive, in cancer tissues, especially for the tumor‐suppressor genes CDKN2A and MLH1.

Figure 2.

Distribution patterns of methylation in non‐cancerous and cancer tissues. Methylation levels, which reflect fractions of cells with the methylation, were quantified in 66 paired samples of non‐cancerous and cancer tissues of gastric cancer patients (modified from Enomoto et al. ( 39 )). They showed a unimodal distribution in non‐cancerous tissues, and a “bimodal” distribution, namely zero or positive, in cancer tissues. This finding supports the idea that methylation in a non‐cancerous tissue reflects events in many cells in the tissue whereas that in a cancer tissue mostly reflects only events in its single precursor cell.

Rare presence of mutations in non‐cancerous tissues. Adjacent non‐cancerous tissues are often used as a control for cancer tissues, and are regarded not to have detectable levels of mutations. To detect accurately such low levels of mutations in non‐cancerous tissues, transgenic animals in which rare mutations can be quantified by selectable mutations of a marker gene have been developed.( 42 , 43 ) Using these transgenic animals and various carcinogenic factors, mutation frequencies of a specific marker gene in non‐cancerous tissues have been shown to be ∼10−5/cell, and to be 10−3/cell, even in a tissue heavily exposed to a mutagenic compound.( 44 ) This very low frequency of mutations in non‐cancerous tissues gives a rationale for the routine use of such tissues as a control.

DNA methylation in non‐cancerous tissues and aging. Once the situation goes to DNA methylation, many investigators noticed that trace amounts of DNA with methylation are present in non‐cancerous tissues of cancer patients. However, it is usually difficult to distinguish whether such methylation is a simple drift or fluctuation without any biological or pathological meaning or something associated with cancer development. A pioneering work by Issa et al. analyzed the correlation between age and levels of methylation, and convincingly showed that aging is one factor that induces DNA methylation.( 45 )

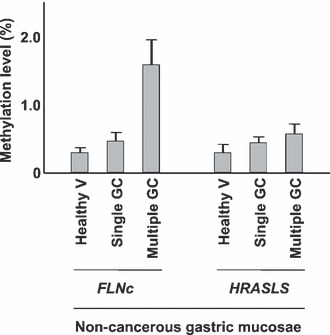

Association between methylation accumulation and cancer risk: Epigenetic field for cancerization. We systematically collected gastric tissue samples from healthy individuals and gastric cancer patients (non‐cancerous part) in an age‐matched manner.( 46 ) Methylation levels of eight CGI in various positions against TSS were accurately quantified. Methylation levels in non‐cancerous gastric tissues of gastric cancer patients were in the range 0.2–8.2%, and were much higher than those in gastric mucosae of healthy individuals. This showed that very high levels of methylation can be present in non‐cancerous tissues, different from mutations. The finding also suggested that accumulation of methylation is related to gastric cancer risk. Subsequently, gastric mucosae of patients with multiple gastric cancers were shown to have higher methylation levels than those of patients with a single gastric cancer (Fig. 3).( 47 ) These discoveries clearly demonstrated that methylation levels in gastric mucosae correlate with gastric cancer risk.

Figure 3.

Correlation between methylation level and cancer risk. Methylation levels of two marker genes (FLNc and HRASLS) were quantified in gastric mucosae of healthy individuals (healthy V), non‐cancerous gastric mucosae of patients with a single gastric cancer (single GC), and non‐cancerous gastric mucosae of patients with multiple gastric cancers (multiple GC) (modified from Nakajima et al. ( 47 )). This showed that accumulation levels of specific genes in non‐cancerous gastric mucosae can correlate with gastric cancer risk. Taken together with the findings in other types of cancers, quantification of methylation levels in normal‐appearing tissues is a promising cancer risk marker that reflects one’s own life history.

A higher incidence or level of methylation in non‐cancerous tissues of cancer patients than that in the corresponding tissues of healthy individuals was also observed for liver,( 48 ) colon,( 49 ) esophageal,( 50 ) and renal( 51 ) cancers. In these types of cancers, accumulation of methylation is likely to be involved in the formation of a field for cancerization (Fig. 1).( 52 ) The gene inactivated by methylation of its promoter CGI in non‐cancerous tissues might be a weak tumor‐suppressor gene that does not induce cellular transformation by itself, such as SFRP1,( 53 ) or might be a passenger that is methylated in parallel with tumor‐suppressor genes.

Inducers of methylation in contrast with those of mutations

Epidemiology indicates that cancer is mainly caused by environmental factors,( 54 ) and identification of inducers of aberrant DNA methylation, in addition to those of mutations, is critically important. However, only limited information is available for the inducers of aberrant methylation.( 55 )

Inducers of mutations. Clarification of inducers of mutations, namely mutagens, constitutes a large field of science, and comprehensive description is beyond the scope of this article. Simplistically, mutations are induced by exogenous mutagenic factors, such as chemicals and radiation, and endogenous factors, such as oxygen radicals.( 56 ) Mutagenic chemicals are contained in diverse sources, including tobacco smoke, overcooked food, and many synthetic chemicals.

Inducers of DNA methylation. To identify inducers of aberrant methylation in humans, analysis of non‐cancerous tissues is important because the methylation level in non‐cancerous tissues reflects how potently the methylation was induced by a factor (Fig. 1). Aging was the first factor that was identified to promote accumulation of DNA methylation,( 45 ) and quantification of methylation in non‐cancerous colonic tissues contributed to the identification.

Afterwards, the presence of methylation in colonic mucosae of patients with ulcerative colitis indicated that chronic inflammation is an important inducer of methylation.( 57 , 58 ) The importance of chronic inflammation was further supported by the presence of methylation in non‐cancerous liver tissue of patients with hepatitis,( 48 ) in inflammatory reflux esophagitis,( 59 ) and in non‐cancerous gastric tissue of individuals infected by Helicobacter pylori. ( 46 ) However, the molecular mechanisms of how chronic inflammation induces aberrant methylation are almost unknown.

There can be chemicals that induce aberrant DNA methylation, but few chemicals are known. If we want to identify a chemical whose primary mode of action is induction of gene silencing, methylation induction in NFR of multiple genes should be demonstrated. Methylation of an exon can be induced as a result of gene expression change, and methylation of a NFR of a specific gene can be induced as a result of loss of its expression, as described below. One of the reasons why methylation‐inducing chemicals have not been identified might be the lack of suitable assay systems, and efforts to develop such systems are being made.( 55 , 60 )

Gene specificity in methylation induction

Mutations are considered to affect random genes, with some preference for actively transcribed genes.( 18 , 61 ) Although there is sequence specificity depending on mutagenic factors,( 62 ) there is little gene specificity. Many investigators thought that DNA methylation would have a similar nature in random target genes, but it has now been shown that there is strong target gene specificity in methylation induction.

Presence of target gene specificity in methylation induction. It was initially found that specific CGI are methylated in specific tumor types, and the presence of gene specificity for methylation induction was indicated.( 27 , 37 ) However, analysis of a cancer tissue reveals only events in its single precursor cell, and the information obtained is very stochastic. Analysis of a panel of cancers can reflect events in the precursor cells of the cancers, but the number of precursor cells analyzed is still limited to the number of cancers analyzed.

In order to avoid selection bias by gene function, and to analyze as many cells as possible, analysis of a non‐cancerous tissue is advantageous. We analyzed methylation of a panel of genes in gastric mucosae with and without H. pylori infection, and showed that specific genes are methylated in gastric mucosae with H. pylori infection.( 63 ) We also analyzed the methylation levels of a panel of genes in esophageal mucosae, and found that specific genes are methylated in correlation with smoking history.( 40 ) These showed that specific inducers of aberrant DNA methylation induce methylation of specific genes. The presence of a “methylation fingerprint” of individual methylation inducers suggests that the fingerprint can be used as a marker for past exposure to specific carcinogenic factors in our lives.

Molecular mechanisms of target gene specificity. As a molecular mechanism for gene specificity, low transcription was suggested in pioneering studies that used an exogenously introduced gene and endogenous genes demethylated by a demethylating agent.( 64 , 65 ) Analysis of selected genes in embryonic stem cells, along with normal adult tissue, and cancer cells revealed that genes marked with trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) in embryonic stem cells are likely to become methylated in cancers.( 66 , 67 , 68 ) The finding was further supported by a genome‐wide analysis of genes with H3K27me3 in cancer cells and corresponding normal cells.( 19 )

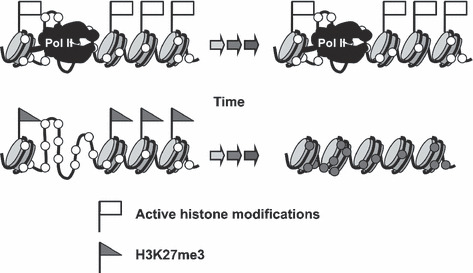

In addition to these factors that confer susceptibility to DNA methylation, the presence of RNA polymerase II (pol II), active or stalled, in NFR was shown to confer resistance to DNA methylation.( 34 ) Although the presence of active histone modifications also confers resistance, the effect of active histone modifications was overridden by the presence of pol II in multivariate analysis, suggesting that the presence of pol II is the final effector that protects NFR from DNA methylation. Taken all together, DNA methylation of NFR is protected by the presence of pol II regardless of transcription levels, and promoted by the presence of H3K27me3 (Fig. 4). Once DNA methylation is induced in susceptible NFR, the H3K27me3 mark almost disappears( 19 ) or decreases to a very low level.( 69 )

Figure 4.

Determinants of methylation destiny. Genes with RNA polymerase II (pol II), active or stalled, are resistant to DNA methylation, and genes with H3K27me3 are susceptible to DNA methylation. The presence of pol II is associated with the presence of active histone modifications, even if a gene is not actively transcribed. Open and closed circles show unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively.

Reversibility of alterations

One of the major differences, or most important difference, between mutations and DNA methylation is reversibility. Physiologically, epigenetic modifications undergo dynamic changes during development, differentiation, and reprogramming.( 70 , 71 ) In somatic cells the demethylating agents 5‐azacytidine and 5‐aza‐2′‐deoxycytidine have long been used in the laboratory.( 72 ) Now these agents have come into clinics and are showing very promising effects in hematological malignancies.( 73 ) The detailed pharmacological mechanisms and usage are summarized in the reviews cited above.

Future perspectives

Now, unique characteristics of DNA methylation are clear, but many questions still remain. Are there any chemicals that induce aberrant methylation of NFR directly, not as a result of gene expression changes? How does chronic inflammation induce aberrant DNA methylation? Do we know enough about the determinants of gene specificity?

At the same time, the biomedical application of DNA methylation is becoming more promising. The large number of genes methylated in a cancer increases the chance of successful identification of methylation biomarkers to predict patient prognosis and response to therapeutics. Cancer‐specific methylation can be used for detection of cancer cells. The presence of an epigenetic field for cancerization in normal‐appearing tissues can be used as a cancer risk marker, which reflects one’s own life history. The deep involvement of chronic inflammation in methylation induction indicates that suppression of components involved in the induction can be utilized as a target of cancer prevention. The methylation fingerprint can be used in epigenetic epidemiology.

Mutations have not been considered as a cause of disorders that involve irreversible alteration of cellular functions, such as neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, immunological disorders, and renal disorders. This was because mutations are rare events and cannot affect as many cells as the function of a tissue is affected as a whole. However, methylation can be induced in many more cells in a tissue, and genes affected are specific. This suggests that a critical gene can be inactivated in a significant fraction of cells, and raises the possibility that aberrant DNA methylation is causally involved in chronic disorders other than cancers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Hideyuki Takeshima for his comments. The work was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for the Third‐term Cancer Control Strategy Program from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

References

- 1. Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell 2007; 128: 683–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1148–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ushijima T. Detection and interpretation of altered methylation patterns in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature 1983; 301: 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feinberg AP, Tycko B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen RZ, Pettersson U, Beard C, Jackson‐Grusby L, Jaenisch R. DNA hypomethylation leads to elevated mutation rates. Nature 1998; 395: 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eden A, Gaudet F, Waghmare A, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal instability and tumors promoted by DNA hypomethylation. Science 2003; 300: 455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamada Y, Jackson‐Grusby L, Linhart H et al. Opposing effects of DNA hypomethylation on intestinal and liver carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 2007; 128: 707–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin JC, Jeong S, Liang G et al. Role of nucleosomal occupancy in the epigenetic silencing of the MLH1 CpG island. Cancer Cell 2007; 12: 432–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohtani‐Fujita N, Fujita T, Aoike A, Osifchin NE, Robbins PD, Sakai T. CpG methylation inactivates the promoter activity of the human retinoblastoma tumor‐suppressor gene. Oncogene 1993; 8: 1063–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ushijima T, Sasako M. Focus on gastric cancer. Cancer Cell 2004; 5: 121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ushijima T, Morimura K, Hosoya Y et al. Establishment of methylation‐sensitive‐representational difference analysis and isolation of hypo‐ and hypermethylated genomic fragments in mouse liver tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 2284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gonzalgo ML, Liang G, Spruck CH, 3rd , Zingg JM, Rideout WM, 3rd , Jones PA. Identification and characterization of differentially methylated regions of genomic DNA by methylation‐sensitive arbitrarily primed PCR. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 594–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang TH, Laux DE, Hamlin BC, Tran P, Tran H, Lubahn DB. Identification of DNA methylation markers for human breast carcinomas using the methylation‐sensitive restriction fingerprinting technique. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 1030–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toyota M, Ho C, Ahuja N et al. Identification of differentially methylated sequences in colorectal cancer by methylated CpG island amplification. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 2307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature 2007; 446: 153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 2007; 318: 1108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gal‐Yam EN, Egger G, Iniguez L et al. Frequent switching of Polycomb repressive marks and DNA hypermethylation in the PC3 prostate cancer cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones PA, Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics comes of age. Nat Genet 1999; 21: 163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y et al. Targeted and genome‐scale strategies reveal gene‐body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol 2009; 27: 361–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamashita S, Hosoya K, Gyobu K, Takeshima H, Ushijima T. Development of a novel output value for quantitative assessment in methylated DNA immunoprecipitation‐CpG island microarray analysis. DNA Res 2009; 16: 275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hellman A, Chess A. Gene body‐specific methylation on the active X chromosome. Science 2007; 315: 1141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rauch TA, Wu X, Zhong X, Riggs AD, Pfeifer GP. A human B cell methylome at 100‐base pair resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 671–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan TA, Glockner S, Yi JM et al. Convergence of mutation and epigenetic alterations identifies common genes in cancer that predict for poor prognosis. PLoS Med 2008; 5: e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keshet I, Schlesinger Y, Farkash S et al. Evidence for an instructive mechanism of de novo methylation in cancer cells. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayashi H, Nagae G, Tsutsumi S et al. High‐resolution mapping of DNA methylation in human genome using oligonucleotide tiling array. Hum Genet 2007; 120: 701–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao W, Kondo Y, Shen L et al. Variable DNA methylation patterns associated with progression of disease in hepatocellular carcinomas. Carcinogenesis 2008; 29: 1901–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rauch TA, Zhong X, Wu X et al. High‐resolution mapping of DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105: 252–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pelizzola M, Koga Y, Urban AE et al. MEDME: an experimental and analytical methodology for the estimation of DNA methylation levels based on microarray derived MeDIP‐enrichment. Genome Res 2008; 18: 1652–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Down TA, Rakyan VK, Turner DJ et al. A Bayesian deconvolution strategy for immunoprecipitation‐based DNA methylome analysis. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26: 779–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Straussman R, Nejman D, Roberts D et al. Developmental programming of CpG island methylation profiles in the human genome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16: 564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takeshima H, Yamashita S, Shimazu T, Niwa T, Ushijima T. The presence of RNA polymerase II, active or stalled, predicts epigenetic fate of promoter CpG islands. Genome Res 2009; 19: 1974–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Markl ID, Cheng J, Liang G, Shibata D, Laird PW, Jones PA. Global and gene‐specific epigenetic patterns in human bladder cancer genomes are relatively stable in vivo and in vitro over time. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 5875–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smiraglia DJ, Rush LJ, Fruhwald MC et al. Excessive CpG island hypermethylation in cancer cell lines versus primary human malignancies. Hum Mol Genet 2001; 10: 1413–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Costello JF, Fruhwald MC, Smiraglia DJ et al. Aberrant CpG‐island methylation has non‐random and tumour‐type‐specific patterns. Nat Genet 2000; 24: 132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weber M, Davies JJ, Wittig D et al. Chromosome‐wide and promoter‐specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat Genet 2005; 37: 853–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Enomoto S, Maekita T, Tsukamoto T et al. Lack of association between CpG island methylator phenotype in human gastric cancers and methylation in their background non‐cancerous gastric mucosae. Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 1853–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oka D, Yamashita S, Tomioka T et al. The presence of aberrant DNA methylation in noncancerous esophageal mucosae in association with smoking history: a target for risk diagnosis and prevention of esophageal cancers. Cancer 2009; 115: 3412–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaneda A, Wakazono K, Tsukamoto T et al. Lysyl oxidase is a tumor suppressor gene inactivated by methylation and loss of heterozygosity in human gastric cancers. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 6410–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kohler SW, Provost GS, Fieck A et al. Spectra of spontaneous and mutagen‐induced mutations in the lacI gene in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88: 7958–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tao KS, Urlando C, Heddle JA. Comparison of somatic mutation in a transgenic versus host locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nagao M, Ochiai M, Okochi E, Ushijima T, Sugimura T. LacI transgenic animal study: relationships among DNA‐adduct levels, mutant frequencies and cancer incidences. Mutat Res 2001; 477: 119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Issa JP, Ottaviano YL, Celano P, Hamilton SR, Davidson NE, Baylin SB. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet 1994; 7: 536–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maekita T, Nakazawa K, Mihara M et al. High levels of aberrant DNA methylation in Helicobacter pylori‐infected gastric mucosae and its possible association with gastric cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakajima T, Maekita T, Oda I et al. Higher methylation levels in gastric mucosae significantly correlate with higher risk of gastric cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15: 2317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kondo Y, Kanai Y, Sakamoto M, Mizokami M, Ueda R, Hirohashi S. Genetic instability and aberrant DNA methylation in chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis‐‐A comprehensive study of loss of heterozygosity and microsatellite instability at 39 loci and DNA hypermethylation on 8 CpG islands in microdissected specimens from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2000; 32: 970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shen L, Kondo Y, Rosner GL et al. MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 1330–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ishii T, Murakami J, Notohara K et al. Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma may develop within a background of accumulating DNA methylation in normal and dysplastic mucosa. Gut 2007; 56: 13–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arai E, Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Fujimoto H, Mukai K, Hirohashi S. Regional DNA hypermethylation and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 protein overexpression in both renal tumors and corresponding nontumorous renal tissues. Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ushijima T. Epigenetic field for cancerization. J Biochem Mol Biol 2007; 40: 142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Suzuki H, Watkins DN, Jair KW et al. Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes allows constitutive WNT signaling in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer‐‐analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ushijima T, Okochi‐Takada E. Aberrant methylations in cancer cells: Where do they come from? Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 206–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morley AA, Turner DR. The contribution of exogenous and endogenous mutagens to in vivo mutations. Mutat Res 1999; 428: 11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hsieh CJ, Klump B, Holzmann K, Borchard F, Gregor M, Porschen R. Hypermethylation of the p16INK4a promoter in colectomy specimens of patients with long‐standing and extensive ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 3942–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Issa JP, Ahuja N, Toyota M, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. Accelerated age‐related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 3573–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eads CA, Lord RV, Kurumboor SK et al. Fields of aberrant CpG island hypermethylation in Barrett’s esophagus and associated adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 5021–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Okochi‐Takada E, Ichimura S, Kaneda A, Sugimura T, Ushijima T. Establishment of a detection system for demethylating agents using an endogenous promoter CpG island. Mutat Res 2004; 568: 187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Loeb LA. A mutator phenotype in cancer. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 3230–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bennett WP, Hussain SP, Vahakangas KH, Khan MA, Shields PG, Harris CC. Molecular epidemiology of human cancer risk: gene‐environment interactions and p53 mutation spectrum in human lung cancer. J Pathol 1999; 187: 8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nakajima T, Yamashita S, Maekita T, Niwa T, Nakazawa K, Ushijima T. The presence of a methylation fingerprint of Helicobacter pylori infection in human gastric mucosae. Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 905–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. De Smet C, Loriot A, Boon T. Promoter‐dependent mechanism leading to selective hypomethylation within the 5′ region of gene MAGE‐A1 in tumor cells. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 4781–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Song JZ, Stirzaker C, Harrison J, Melki JR, Clark SJ. Hypermethylation trigger of the glutathione‐S‐transferase gene (GSTP1) in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2002; 21: 1048–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ohm JE, McGarvey KM, Yu X et al. A stem cell‐like chromatin pattern may predispose tumor suppressor genes to DNA hypermethylation and heritable silencing. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 237–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schlesinger Y, Straussman R, Keshet I et al. Polycomb‐mediated methylation on Lys27 of histone H3 pre‐marks genes for de novo methylation in cancer. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Widschwendter M, Fiegl H, Egle D et al. Epigenetic stem cell signature in cancer. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 157–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. McGarvey KM, Van Neste L, Cope L et al. Defining a chromatin pattern that characterizes DNA‐hypermethylated genes in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 5753–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gan Q, Yoshida T, McDonald OG, Owens GK. Concise review: epigenetic mechanisms contribute to pluripotency and cell lineage determination of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2007; 25: 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H et al. Genome‐scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 2008; 454: 766–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jones PA, Taylor SM. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell 1980; 20: 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Issa JP, Kantarjian HM. Targeting DNA methylation. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 3938–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]