Abstract

Cyclin D1 binds to the Cdk4 and Cdk6 to form a pRB kinase. Upon phosphorylation, pRB loses its repressive activity for the E2F transcription factor, which then activates transcription of several genes required for the transition from the G1‐ to S‐phase and for DNA replication. The cyclin D1 gene is rearranged and overexpressed in centrocytic lymphomas and parathyroid tumors and it is amplified and/or overexpressed in a major fraction of human tumors of various types of cancer. Ectopic overexpression of cyclin D1 in fibroblast cultures shortens the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that introduction of an antisense cyclin D1 into a human carcinoma cell line, in which the cyclin D1 gene is amplified and overexpressed, causes reversion of the malignant phenotype. Thus, increased expression of cyclin D1 can play a critical role in tumor development and in maintenance of the malignant phenotype. However, it is insufficient to confer transformed properties on primary or established fibroblasts. In this review, we summarize the role of cyclin D1 on tumor development and malignant transformation. In addition, our chemical biology study to understand the regulatory mechanism of cyclin D1 transcription is also reviewed. (Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 629–635)

In mammalian cells, the progression of replicating cells through the cell cycle is controlled by the sequential formation, activation, and subsequent inactivation of a series of specific cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) complexes. The second regulatory mechanism involves the binding of specific inhibitory proteins (p21WAF1, p27KIP1, p57KIP2) to cyclin–CDK complexes or the binding of specific inhibitory proteins directly to CDK4 (p15, p16INK1, p18, and p19). 1 , 2 , 3 ) There is now abundant evidence that disturbances in specific cyclins, CDKs, or the above‐mentioned inhibitory proteins play an important role in several types of human cancer. 1 , 2 , 3 ) The most frequent abnormalities relate to cyclin D1. The cyclin D1 gene encodes a regulatory subunit of the cdk4 and cdk6 holoenzyme complex, which phosphorylates and deactivates the tumor suppressor protein pRB. (3 ) The phophorylation of pRB results in its inactivation and the release of E2Fs that have been sequestered by the unphosphorylated (active) form of pRB. Once liberated by pRB inactivation, E2Fs then proceed to activate genes that are essential for advances into the late G1 and S phases. (4 ) Consistent with its growth‐promoting role, cyclin D1 can act as an oncogene. Indeed, rearrangement, amplification, and/or increased expression of the cyclin D1 gene and overexpression of its mRNA have been reported in several types of human cancer, including human parathyroid adenomas, B cell lymphomas, breast, colon, lung, bladder and liver cancers, and squamous carcinomas of the esophagus, head and neck. 2 , 5 , 6 ) The expression of cyclin D1 mRNA and protein peaks during mid‐G1 when growth factor‐deprived cells are restimulated to enter the cell cycle. 7 , 8 ) Inhibition of cyclin D1 expression either by antisense methodology or antibody microinjection lengthens the duration of the G1 phase and caused a reduction in proliferation and a loss of tumorigenicity in nude mice. 9 , 10 ) Overexpression of cyclin D1 leads to a shortened duration of the G1 phase decreased cell size and reduced serum dependency in rodent fibroblasts. 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) Although the cyclin D1 overexpressing rat fibroblasts formed colonies in soft agar, these colonies were much smaller in size than the macroscopic colonies seen with c‐Ha‐ras transformed rat fibroblast cells.(8) In addition, efficient tumor induction in nude mice with the cyclin D1 overexpressing rat fibroblast cells required the injection of a large number of cells and a latent period than in the case of c‐Ha‐ras transformed rat fibroblast cells.(8) Therefore, how cyclin D1 contributes to tumor development and malignant transformation was still obscure.

Effect of expression of antisense cyclin D1 cDNA on the malignant properties of cancer cells

To better assess the specific role of cyclin D1 on malignant properties, we stably expressed an antisense cyclin D1 cDNA construct in the tumorigenic human esophageal cell line TTn. In antisense cyclin D1 cells, there was marked inhibition of anchorage‐independent growth and the cells lost their tumorigenicity in nude mice. Furthermore, these cells displayed decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the medium obtained from these cells completely failed to induce tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). (14 ) Although the exact mechanism responsible for the latter effect is not known, these results provide evidence that cyclin D1 overexpression plays a role in enhancing tumor angiogenesis. Our results are consistent with an earlier study by Harada et al. who demonstrated that restoring wild type p16 expression to p16‐deleted glioma cells significantly reduced the expression of VEGF. (15 ) Because p16 binds to and inhibits cdk4, we presume that the suppression of VEGF expression by p16 in these glioma cells and by cyclin D1 antisense cDNA in TTn cells, occur through similar mechanisms, but the precise mechanisms remain to be determined.

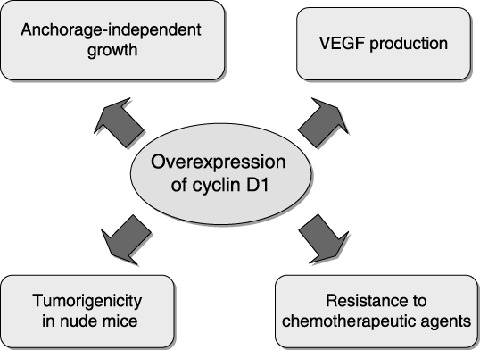

Previous reports indicate that cyclin D1 overexpression contributes to the resistance of several tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatinum (CDDP). 16 , 17 ) We also found that reduced expression of cyclin D1 in TTn cells was associated with an increase in chemosensitivity, not only to CDDP but also to 5‐FU, Adriamycin and VP16. Furthermore, the cyclin D1 antisense TTn cells displayed enhanced Fas antibody (CH11)‐induced apoptosis. It has been reported that activation of the Fas/FasL system is involved in the apoptosis induced by some chemotherapeutic agents, including VP16 and Adriamycin. (18 ) Therefore, it is likely that overexpression of cyclin D1 down‐regulates Fas expression in esophageal cancer cells, thereby enhancing resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. In addition, because esophageal cancer cells often overexpress FasL, resulting in protection from immune surveillance, (19 ) overexpression of cyclin D1 may protect cells from self‐destruction by decreasing Fas expression, thus enhancing their malignancy. Taken together, these results demonstrated that cyclin D1 can perform multiple functions as an oncogene, by enhancing several processes during malignant cell transformation, including abnormal growth, angiogenesis and resistance to apoptosis (Fig. 1). (14 ) These findings also provide further evidence that therapeutic strategies that target cyclin D1, or cyclin D1‐related functions, may have the dual advantage of suppressing the growth of cancer cells while enhancing their chemosensitivity.

Figure 1.

Functions of the cyclin D1 protein in tumor progression. Overexpression of cyclin D1 can confer tumor cells with enhanced malignancy through increases in anchorage‐independent growth and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production, and down‐regulation of Fas expression, leading to resistance to chemotherapeutic agents.

Overexpression of cyclin D1 contributes to malignancy by up‐regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor

Although overexpression of cyclin D1 can provoke a perturbed progression of the G1 phase of a cell cycle, 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) it is insufficient to confer transformed properties on primary or established fibroblasts. Nevertheless, cyclin D1 overexpression might be expected to cooperate with other proto‐oncogenes in transformation. This prediction has been confirmed in several systems. Cyclin D1 can cooperate with the Ras oncogene to transform primary baby rat kidney cells (3 ) and rat embryo fibroblasts, (4 ) and it can also cooperate with c‐Myc to induce B cell lymphomas in transgenic mice. (20 ) Moreover, it was shown that Ras requires cyclin D1 to transform mammary gland epithelial cells. (21 ) We found that overexpression of cyclin D1 rendered quiescent rodent fibroblast cells to respond to basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and there was enhanced cell cycle progression and Erk2 activation. (22 ) In addition, the expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor‐1 (FGFR‐1) was increased in cyclin D1‐overexpressing fibroblasts at both mRNA and protein levels when compared to normal cells. Therefore, we propose that overexpression of cyclin D1 stimulates the expression of FGFR‐1 transcriptionally, thereby sensitizing cells to bFGF. (22 )

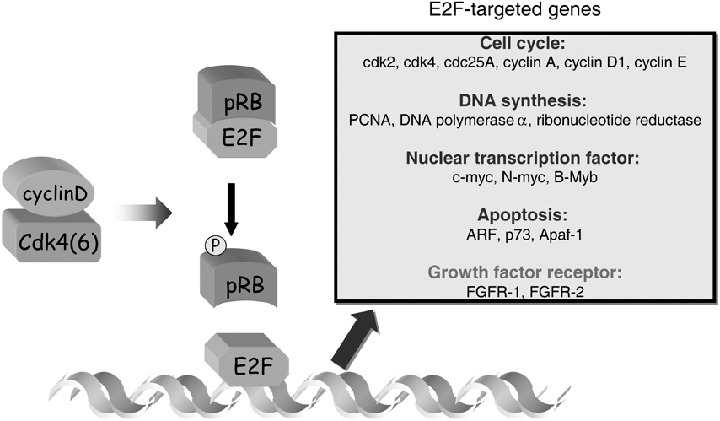

We also demonstrated that transcription of human or mouse FGFR‐1 is regulated by E2F‐1 through an E2F‐1 binding site within the promoter region of these two genes. (22 ) Previous studies indicate that E2F‐1‐mediated transcription is stimulated by an E2F‐1 regulatory loop that amplifies the expression of the E2F‐1 gene itself. 23 , 24 , 25 ) Overexpression of cyclin D1 induces hyperphosphorylation of pRB, thus resulting in activation of this positive feedback loop of E2F‐1‐mediated transcription. This mechanism apparently explains our finding that FGFR‐1 is expressed at increased levels in cyclin D1‐overexpressing cells. The pRB/E2F pathway has shown to be deregulated in a large majority of human tumors. The importance of the pRB/E2F pathway in normal growth control is emphasized by the frequent loss of pRB functions or the mutation of upstream regulators of pRB (e.g. cyclin D1, cdk4, or p16INK4a) in human tumors. Thus, although mutations in E2F have never been detected in human tumors, E2F might be a key regulator not only for inducing S‐phase entry but also in tumor development. Most, if not all, of the E2F‐targeted genes are growth/cell cycle‐regulated genes that are involved in the control of the cell cycle (e.g. cdk2 and 4, cdc25A, cyclin A, D, and E), DNA synthesis (e.g. PCNA, DNA polymerase a, ribonucleotide reductase), or nuclear transcription factor (c‐myc, N‐myc and B‐myb). p19ARF, p73 homolog of p53, and Apaf‐1 were also identified as E2F‐1‐targeted genes. However, growth factor or growth factor receptor genes have not yet been reported as E2F‐targeted genes. We demonstrated that FGFR‐1 represents a new class of genes targeted by E2F. (22 ) Moreover, we also found that FGFR‐2 is a target for E2F, and expression of mouse FGFR‐2 in the mid‐ to late‐G1 phase would be mediated, at least in part, by the activation of a cyclin D1/pRB/E2F pathway (Fig. 2). (26 ) Deregulated expression of various growth factor receptors is also seen in many types of human tumors, and frequently it correlates with both tumor progression and a poor prognosis. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is frequently overexpressed in many types of tumors, and its closely related ErbB2 is overexpressed in breast, ovarian and stomach cancers. (27 ) The hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) is also overexpressed up to 100‐fold in thyroid papillary carcinoma 28 , 29 ) when comparing normal epithelial cells to epithelial tumor cells. FGFR overexpression has been shown in brain, breast, prostate, thyroid, melanoma and salivary gland tumor samples in comparison to normal tissue by immunohistochemistry. (30 ) In these FGFR overexpressing tumor cases, one or more FGF is often also expressed, creating the possibility for autocrine FGF signaling. Because FGFs play important roles not only in embryonic development and cell proliferation but also in angiogenesis and wound healing, (30 ) they might enhance malignant properties of such cells, by autocrine mechanisms. However, the causes for the overexpression of most receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are largely uncharacterized. Therefore, our findings may provide new insights into the functional significance of the pRB/E2F pathway in regulating growth factor receptor expression and its coupling to enhanced cell growth and tumorigenesis.

Figure 2.

E2F‐targeted genes. The transcriptional activity of E2F‐1 is negatively regulated by the product of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene (pRB) and is indirectly regulated by a specific cyclin, such as the D‐type cyclins and their associated kinases (Cdk4 and Cdk6). Fibroblast growth factor receptor‐1 (FGFR‐1) and FGFR‐2 represent a new class of genes targeted by E2F. Their expressions are increased at the level of transcription by the overexpression of cyclin D1.

We examined whether or not bFGF stimulated the anchorage‐independent growth of the cyclin D1‐overexpressing fibroblasts, since this is a hallmark of malignantly transformed cells. We found a marked enhancement of colony formation when the cyclin D1‐overexpressing NIH3T3 clones were stimulated with bFGF. The anchorage‐independent growth of the bFGF‐stimulated cyclin D1‐overexpressing clones was comparable to that of c‐Ha‐ras transformed NIH3T3 cells. Stimulation by EGF caused only a small enhancement of anchorage‐independent growth of the cyclin D1‐overexpressing clones. In addition, when treated with bFGF, cyclin D1‐overexpressing NIH3T3 clones displayed enhanced invasion of a matrigel barrier compared to vector control clones. Thus, cyclin D1‐overexpressing cells display only a slight increase in two markers of malignant transformation, anchorage‐independent growth and invasion, but a marked increase in these two markers when treated with bFGF. (22 )

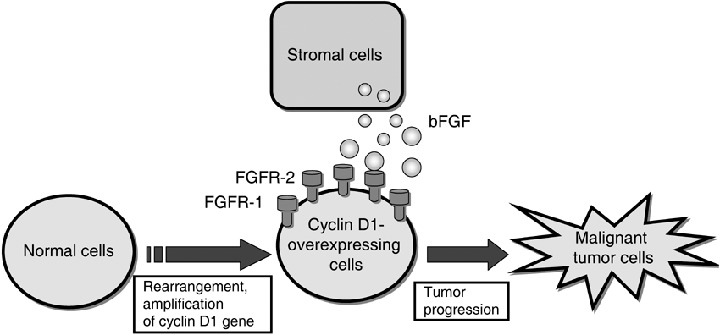

There is increasing evidence that in vivo, the malignant state emerges from complex interactions in the tumor‐host microenvironment in which the host participates in the induction, selection and expansion of neoplastic cells. (31 ) Because bFGF can stimulate growth and stromal invasion by tumor cells (31 ) it is likely that in vivo, the extracellular bFGF produced by stromal cells (32 ) or the locally activated host microenvironment might also enhance the proliferative and invasive behavior of cyclin D1‐overexpressing tumor cells, because of their increased expression of FGFR‐1 and FGFR‐2, thereby enhancing tumor progression (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Possible mechanism of tumor progression in Cyclin D1‐overexpressing tumor cells. Overexpression of cyclin D1 due to gene rearrangement, gene amplification or simply increased transcription can cooperate with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), which is produced by stromal cells, to cause further progression of transformation in established fibroblasts through induction of increased expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor‐1 (FGFR‐1) and FGFR‐2.

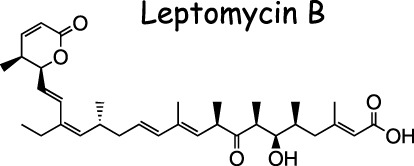

Mechanism of leptomycin B‐induced inhibition of cyclin D1 expression

Leptomycin B (LMB) (Fig. 4) is a Streptomyces metabolite (33 ) that causes the specific inhibition of CRM1‐dependent nuclear export of nuclear export signal (NES)‐containing proteins. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ) LMB was reported to inhibit cell cycle progression in fission yeast and mammalian cells. 38 , 39 ) However, the mechanism underlying LMB‐induced cell cycle arrest is still obscure. We found that LMB inhibited serum‐induced expression of cyclin D1, thereby inhibiting downstream events such as cyclin E expression and Cdk2 activation required for G1/S transition. (40 ) Furthermore, LMB was found to cause a significant reduction in promoter activity of cyclin D1, which was reflected in the overall decrease in cyclin D1 mRNA detected by Northern blot analysis. Thus, we proposed that the inhibition of cyclin D1 expression at the level of transcription by LMB is, at least in part, responsible for LMB‐induced cell cycle arrest at G1.

Figure 4.

Structure of leptomycin B.

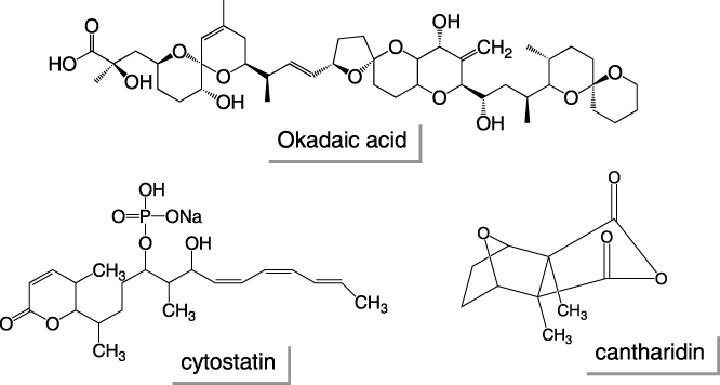

There is now a growing number of chemical inhibitors of signal transduction pathways. Chemical biology approaches using a chemical library with various inhibitors of signaling molecules enables us to easily study the signal transduction system involved in cellular events of interest. Therefore, we examined the mechanism underlying the LMB‐induced suppression of cyclin D1 transcription using a chemical biological approach. To explore the signal transduction system involved in the inhibition of cyclin D1 expression following LMB treatment, over 90 inhibitors of the signal transduction system in the ‘SCADS inhibitor kit I’ were assessed for their ability to reverse the suppressive effect of LMB on cyclin D1 promoter activity in NIH3T3 cells. After the screening of the library, we found that protein phosphatase 2 A (PP2A) inhibitors, such as okadaic acid, cantharidin or cytostatin, restored the LMB‐inhibited cyclin D1 expression (Fig. 5). Moreover, we also found that LMB induced the nuclear accumulation of PP2A in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 6). (40 )

Figure 5.

Structures of protein phosphatase inhibitors.

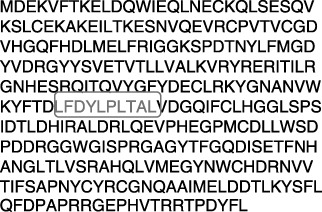

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the primary structure of PP2Acα (human) showing a putative nuclear export signal (NES) sequence. PP2A is a holoenzyme composed of three subunits, the catalytic subunit (PP2A/C), the structural A subunit (also known as PR65), and the regulatory B subunit. We searched for a leucine‐rich sequence with conserved spacings and hydrophobicity that fits the criteria established for a NES in the primary amino acid sequences of these three subunits, and we found that a NES lies between 149 and 158 in human PP2Acα. Nuclear export signals are boxed.

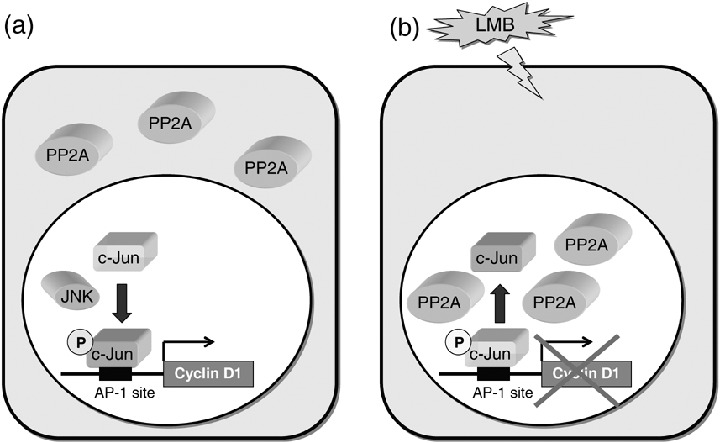

In view of our findings that LMB induced nuclear accumulation of PP2A and inhibited cyclin D1 expression, we hypothesized that the nuclear accumulation of PP2A by LMB might induce sustained dephosphorylation and inactivation of nuclear proteins involved in the regulatory mechanism of cyclin D1 expression. One such candidate nuclear protein is c‐Jun, an important component of transcription factor AP‐1. This idea had come from the following reported facts: (i) The activation of c‐Jun depends on the phosphorylation of Ser‐63 and Ser‐73, which enables c‐Jun to bind CBP (cAMP‐response element‐binding protein [CRBP]) and form a larger complex to activate the transcription. (41 ) (ii) PP2A represses AP‐1 activity by dephosphorylation of c‐Jun on Ser‐63. 42 , 43 , 44 ) (iii) c‐Jun enhances cell proliferation through the induction of cyclin D1 transcription, shown by several reports. 45 , 46 , 47 ) The possibility that the involvement of c‐Jun in the mechanism of LMB‐induced reduction of cyclin D1 expression was further supported by our findings that (40 ) (i) serum‐induced cyclin D1 expression is required for the AP‐1 site in the promoter region of the cyclin D1 gene, and the residual promoter activity of the AP‐1 site‐deleted or point‐mutated cyclin D1 promoter construct is no longer inhibited by LMB treatment. (ii) Overexpression of c‐Jun induced an increase in cyclin D1 promoter activity, indicating that c‐Jun is involved in cyclin D1 expression. Consistent with this result, fibroblasts derived from the c‐Jun−/– embryo display reduced the expression of cyclin D1. (48 ) (iii) The phosphorylation of c‐Jun at Ser‐63 and Ser‐73 is required for its transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 promoter. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that c‐Jun phosphorylation, mimicked by the use of aspartic acid residues at Ser‐63 and Ser‐73, significantly increased the positive effects of c‐Jun on cyclin D1 transcription. (49 ) (iv) The level of c‐Jun phosphorylated at Ser‐63 was significantly decreased in LMB‐treated NIH3T3 cells compared to untreated cells. (v) Okadaic acid restored the LMB‐induced repression of both the phosphorylation of c‐Jun at Ser‐63 and the expression of cyclin D1. (vi) LMB failed to inhibit the cyclin D1 promoter activity induced with the constitutive active mutant c‐Jun (S63/73D). Taken together, we proposed that the molecular mechanism for LMB‐inhibited cyclin D1 expression as follows: LMB induced nuclear accumulation of PP2A by inhibiting its CRM1‐dependent nuclear export, leading to the enhancement of dephosphorylation and the inactivation of c‐Jun in the nucleus, thereby reducing the transcription of the AP‐1‐responsive cyclin D1 gene (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Possible mechanism of leptomycin B (LMB)‐induced inhibition of cyclin D1 expression. (a) The phosphorylation of c‐Jun at Ser‐63 and Ser‐73 enables c‐Jun to activate the transcription of the AP‐1‐responsive cyclin D1 gene. (b) The nuclear accumulation of PP2A induced by LMB leads to sustained dephosphorylation of c‐Jun at Ser‐63, therefore reducing the transcription of the AP‐1‐responsive cyclin D1 gene.

Conclusions

In this review, we demonstrated that cyclin D1 could carry out multiple functions as an oncogene, by enhancing several processes during malignant cell transformation, including abnormal growth, angiogenesis and resistance to apoptosis. We also demonstrated that overexpression of cyclin D1 induced up‐regulation of FGFR‐1 and ‐2 expression, thereby sensitizing the cells to growth stimulation by bFGF. These findings raise the possibility that in vivo cyclin D1 overexpression can enhance tumor progression, at least in part, by potentiating the stimulatory efforts of bFGF, which is often produced by stromal cells, and the growth of adjacent tumor cells. In view of the multiple functions of cyclin D1 as an oncogene, targeting its expression seems to be warranted as cancer chemotherapy. LMB inhibited cyclin D1 expression at the level of transcription by inhibiting the CRM1‐dependent nuclear export of PP2A, leading to sustained dephosphorylation of c‐Jun in the nucleus. Further studies of the molecular control of cyclin D1 expression would be useful for the development of anticancer agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Screening Committee of Anticancer Drugs support through a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on the Priority Area ‘Cancer’ from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology for the generous gift of The SCADS inhibitor kit I.

References

- 1. Draetta GF. Mammalian G1 cyclins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1994; 6: 842–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunter T, Pines J. Cyclins and cancer. II: Cyclin D and CDK inhibitors come of age. Cell 1994; 79: 573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell 1994; 79: 551–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weinberg RA. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell 1995; 81: 323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Motokura T, Arnold A. Cyclin D and oncogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1993; 3: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sherr CJ. Mammalian G1 cyclins. Cell 1993; 73: 1059–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Won KA, Xiong Y, Beach D, Gilman MZ. Growth‐regulated expression of d‐type cyclin genes in human diploid fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992; 89: 9910–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang W, Kahn SM, Zhou P et al. Overexpression of cyclin D1 in rat fibroblasts causes abnormalities in growth control, cell cycle progression and gene expression. Oncogene 1993; 8: 3447–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou P, Jiang W, Zhang YJ et al. Antisense to cyclin D1 inhibits growth and reverses the transformed phenotype of human esophageal cancer cells. Oncogene 1995; 11: 571–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arber N, Doki Y, Han EK et al. Antisense to cyclin D1 inhibits the growth and tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 1569–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quelle DE, Ashmun RA, Shurtleff SA et al. Overexpression of mouse d‐type cyclins accelerates G1 phase in rodent fibroblasts. Genes Dev 1993; 7: 1559–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Resnitzky D, Gossen M, Bujard H, Reed SI. Acceleration of the G1/S phase transition by expression of cyclins D1 and E with an inducible system. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14: 1669–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Imoto M, Doki Y, Jiang W, Han EK, Weinstein IB. Effects of cyclin D1 overexpression on G1 progression‐related events. Exp Cell Res 1997; 236: 173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shintani M, Okazaki A, Masuda T et al. Overexpression of cyclin DI contributes to malignant properties of esophageal tumor cells by increasing VEGF production and decreasing Fas expression. Anticancer Res 2002; 22: 639–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harada H, Nakagawa K, Iwata S et al. Restoration of wild‐type p16 down‐regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and inhibits angiogenesis in human gliomas. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 3783–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kornmann M, Arber N, Korc M. Inhibition of basal and mitogen‐stimulated pancreatic cancer cell growth by cyclin D1 antisense is associated with loss of tumorigenicity and potentiation of cytotoxicity to cisplatinum. J Clin Invest 1998; 101: 344–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warenius HM, Seabra LA, Maw P. Sensitivity to cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum in human cancer cells is related to expression of cyclin D1 but not c‐raf‐1 protein. Int J Cancer 1996; 67: 224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simizu S, Shibasaki F, Osada H. Bcl‐2 inhibits calcineurin‐mediated Fas ligand expression in antitumor drug‐treated baby hamster kidney cells. Jpn J Cancer Res 2000; 91: 706–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gratas C, Tohma Y, Barnas C, Taniere P, Hainaut P, Ohgaki H. Up‐regulation of Fas (APO‐1/CD95) ligand and down‐regulation of Fas expression in human esophageal cancer. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 2057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lovec H, Sewing A, Lucibello FC, Muller R, Moroy T. Oncogenic activity of cyclin D1 revealed through cooperation with Ha‐ras: link between cell cycle control and malignant transformation. Oncogene 1994; 9: 323–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu Q, Geng Y, Sicinski P. Specific protection against breast cancers by cyclin D1 ablation. Nature 2001; 411: 1017–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tashiro E, Maruki H, Minato Y, Doki Y, Weinstein IB, Imoto M. Overexpression of cyclin D1 contributes to malignancy by up‐regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 via the pRB/E2F pathway. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 424–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsiao KM, McMahon SL, Farnham PJ. Multiple DNA elements are required for the growth regulation of the mouse E2F1 promoter. Genes Dev 1994; 8: 1526–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson DG, Ohtani K, Nevins JR. Autoregulatory control of E2F1 expression in response to positive and negative regulators of cell cycle progression. Genes Dev 1994; 8: 1514–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neuman E, Flemington EK, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG Jr. Transcription of the E2F‐1 gene is rendered cell cycle dependent by E2F DNA‐binding sites within its promoter. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14: 6607–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tashiro E, Minato Y, Maruki H, Asagiri M, Imoto M. Regulation of FGF receptor‐2 expression by transcription factor E2F‐1. Oncogene 2003; 22: 5630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor‐related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1995; 19: 183–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prat M, Narsimhan RP, Crepaldi T, Nicotra MR, Natali PG, Comoglio PM. The receptor encoded by the human c‐MET oncogene is expressed in hepatocytes, epithelial cells and solid tumors. Int J Cancer 1991; 49: 323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Di Renzo MF, Olivero M, Serini G et al. Overexpression of the c‐MET/HGF receptor in human thyroid carcinomas derived from the follicular epithelium. J Endocrinol Invest 1995; 18: 134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Powers CJ, McLeskey SW, Wellstein A. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors and signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer 2000; 7: 165–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumour–host interface. Nature 2001; 411: 375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dow JK. deVere White RW. Fibroblast growth factor 2: its structure and property, paracrine function, tumor angiogenesis, and prostate‐related mitogenic and oncogenic functions. Urology 2000; 55: 800–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hamamoto T, Gunji S, Tsuji H, Beppu T. Leptomycins A and B, new antifungal antibiotics. I. Taxonomy of the producing strain and their fermentation, purification and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983; 36: 639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj IW. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine‐rich nuclear export signals. Cell 1997; 90: 1051–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kudo N, Wolff B, Sekimoto T et al. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal‐mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp Cell Res 1998; 242: 540–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kudo N, Matsumori N, Taoka H et al. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 9112–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nishi K, Yoshida M, Fujiwara D, Nishikawa M, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Leptomycin B targets a regulatory cascade of crm1, a fission yeast nuclear protein, involved in control of higher order chromosome structure and gene expression. J Biol Chem 1994; 269: 6320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoshida M, Beppu T. Reversible arrest of proliferation of rat 3Y1 fibroblasts in both the G1 and G2 phases by trichostatin A. Exp Cell Res 1988; 177: 122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yoshida M, Nishikawa M, Nishi K, Abe K, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Effects of leptomycin B on the cell cycle of fibroblasts and fission yeast cells. Exp Cell Res 1990; 187: 150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tsuchiya A, Tashiro E, Yoshida M, Imoto M. Involvement of protein phosphatase 2A nuclear accumulation and subsequent inactivation of activator protein‐1 in leptomycin B‐inhibited cyclin D1 expression. Oncogene 2006; Sep 11, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bannister AJ, Oehler T, Wilhelm D, Angel P, Kouzarides T. Stimulation of c‐Jun activity by CBP: c‐Jun residues Ser63/73 are required for CBP induced stimulation in vivo and CBP binding in vitro. Oncogene 1995; 11: 2509–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ramirez CJ, Haberbusch JM, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. Retinoic acid induced repression of AP‐1 activity is mediated by protein phosphatase 2A in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem 2005; 96: 170–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Al‐Murrani SW, Woodgett JR, Damuni Z. Expression of I2PP2A, an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A, induces c‐Jun and AP‐1 activity. Biochem J 1999; 341: 293–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alberts AS, Deng T, Lin A et al. Protein phosphatase 2A potentiates activity of promoters containing AP‐1‐binding elements. Mol Cell Biol 1993; 13: 2104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watanabe G, Howe A, Lee RJ et al. Induction of cyclin D1 by simian virus 40 small tumor antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 12 861–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whang YM, Kim YH, Kim JS, Yoo YD. RASSF1A suppresses the c‐Jun – NH2‐kinase pathway and inhibits cell cycle progression. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 3682–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shiozawa T, Miyamoto T, Kashima H, Nakayama K, Nikaido T, Konishi I. Estrogen‐induced proliferation of normal endometrial glandular cells is initiated by transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 via binding of c‐Jun to an AP‐1 sequence. Oncogene 2004; 23: 8603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wisdom R, Johnson RS, Moore C. c‐Jun regulates cell cycle progression and apoptosis by distinct mechanisms. Embo J 1999; 18: 188–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bakiri L, Lallemand D, Bossy‐Wetzel E, Yaniv M. Cell cycle‐dependent variations in c‐Jun and JunB phosphorylation: a role in the control of cyclin D1 expression. Embo J 2000; 19: 2056–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]