Abstract

Melioidosis is a bacterial infection caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, that is common in tropical and subtropical countries including Southeast Asia and Northern Australia. The magnitude of undiagnosed and untreated melioidosis across the country remains unclear. Given its proximity to regions with high infection rates, Riau Province on Sumatera Island is anticipated to have endemic melioidosis. This study reports retrospectively collected data on 68 culture-confirmed melioidosis cases from two hospitals in Riau Province between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2021, with full clinical data available on 41 cases. We also describe whole genome sequencing and genotypic analysis of six isolates of B. pseudomallei. The mean age of the melioidosis patients was 49.1 (SD 11.5) years, 85% were male and the most common risk factor was diabetes mellitus (78%). Pulmonary infection was the most common presentation (39%), and overall mortality was 41%. Lung as a focal infection (aOR: 6.43; 95% CI: 1.13–36.59, p = 0.036) and bacteremia (aOR: 15.21; 95% CI: 2.59–89.31, p = 0.003) were significantly associated with death. Multilocus sequence typing analysis conducted on six B.pseudomallei genomes identified three sequence types (STs), namely novel ST1794 (n = 3), ST46 (n = 2), and ST289 (n = 1). A phylogenetic tree of Riau B. pseudomallei whole genome sequences with a global dataset of genomes clearly distinguished the genomes of B. pseudomallei in Indonesia from the ancestral Australian clade and classified them within the Asian clade. This study expands the known presence of B. pseudomallei within Indonesia and confirms that Indonesian B. pseudomallei are genetically linked to those in the rest of Southeast Asia. It is anticipated that melioidosis will be found in other locations across Indonesia as laboratory capacities improve and standardized protocols for detecting and confirming suspected cases of melioidosis are more widely implemented.

Author summary

Melioidosis is a disease caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. This disease can affect various organs such as the lungs, skin and soft tissues, central nervous system, internal organs, and others. The clinical manifestations vary, and the lack of laboratory examination support in some countries leads to underreporting of the disease. This also results in a varied death rate, ranging from 10–40% and even higher in some countries. The disease is endemic in the Southeast Asian region and northern Australia and is increasingly recognised in other tropical and sub-tropical locations globally. Indonesia has reported over 100 cases from at least 5 diverse regions. One province in Indonesia, Riau, located on the island of Sumatera bordering Malaysia, has been experiencing a relatively high number of melioidosis cases. This study reports melioidosis cases obtained from two referral hospitals in the province of Riau. The research explores the characteristics of patients, clinical manifestations, and outcomes in these cases. Additionally, the study analyzes factors influencing mortality from melioidosis in Riau. Phylogenetic analysis of six isolates of B. pseudomallei determined that B. pseudomallei in the province of Riau, Indonesia is genetically linked to those from neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia.

Introduction

Melioidosis is an infection caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, a Gram-negative, non-sporing environmental bacterium [1–3]. B. pseudomallei affects animals and humans and is endemic in Southeast Asia, northern Australia and other tropical and subtropical regions [1–4]. B. pseudomallei can be transmitted through skin inoculation, inhalation, or ingestion [5–7]. B. pseudomallei is remarkably resilient and can survive in various hostile environmental conditions, including nutrient deficient soil or even distilled water [8–10]. These bacteria exhibit the ability to persist within host cells by manipulating the host’s immune response, allowing it to evade the immune system [11,12]. B. pseudomallei is intrinsically resistant to antibiotics used to cover common causes of bacterial sepsis such as first- and second-generation cephalosporins, macrolides, colistin and aminoglycosides [13]. Currently, the management of melioidosis involves two phases: the acute phase, which aims to prevent sepsis-related deaths, and the eradication phase, which focuses on preventing recurrence/ relapse [13–16].

The estimation of melioidosis case numbers is challenging, particularly in regions with limited laboratory diagnostic capacity but also given the wide range of clinical presentations associated with melioidosis [15,17]; however, reports indicate an increasing number of melioidosis cases globally [18,19]. A modelling study conducted in 2016 estimated that there were 165,000 cases of melioidosis worldwide, with a predicted 89,000 deaths annually [20]. South Asian countries accounted for 44% of the predicted burden [20].

In Indonesia, the first case of melioidosis was diagnosed in Cikande, Banten Province in 1929 [21,22]. Similar to other countries in Asia, it is suspected that many cases of melioidosis in Indonesia go undiagnosed or unreported. The modelling study predicted that Indonesia may experience over 20,000 cases of melioidosis annually with over 10,000 deaths [20]. A study analyzing 146 confirmed cases of melioidosis based on culture results from various regions in Indonesia between 2012 and 2017 found an overall mortality rate of 43% [22]. Cases were reported from Sumatera, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Nusa Tenggara.

Riau Province, situated on Sumatera Island, is predicted to be endemic for melioidosis cases due to its proximity to high-incidence areas like Thailand and Malaysia. Based on the data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, the age-standardized Years of Life Lost (YLL) rates in Riau provinces, attributed to leading causes in 2019, closely align with those of Indonesia [23]. The six predominant risk factors for Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in Indonesia for the same year were elevated systolic blood pressure, tobacco consumption, dietary risks, high fasting plasma glucose, increased BMI (body mass index), and child/maternal malnutrition [23]. High BMI emerged as the dominant risk factor for Riau [23]. In this study, we report melioidosis cases observed in two hospitals in Riau Province over the past 13 years, and we also conducted whole genome sequencing on six isolates of B. pseudomallei from humans to progress insights into the global phylogeography of this species.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This study received approval from the Ethics Unit of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Riau (No. B/120/UN19.5.1.1.8/UEPKK/2021), and informed written consent was obtained from the patients prior to data collection.

Study locations, subjects and data collection

Riau Province spans an area of 87,023.66 km2 and has a population of 6,454,751 individuals. It is situated in the central part of the east coast of Sumatera Island and borders the Malacca Strait, adjacent to Malaysia. The province is traversed by the Siak River. which is the deepest river in Indonesia. The Siak River serves various purposes for the community.

Data for this study were collected from the microbiology laboratories of two hospitals in Riau Province. The data spanned from 1 January 2009, coinciding with the availability of bacterial culture examination in both hospitals, until 31 December 2021. These hospitals are Arifin Achmad Hospital, a government teaching hospital with 598 beds, and Eka Hospital, a private hospital with 300 beds.

B. pseudomallei identification was conducted using the Vitek 2 System (Biomeriuex, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Each culture of B. pseudomallei was documented and cross-referenced with the patients’ medical records. Additionally, patient data including age, sex, residence, admission date, clinical risk factors such as diabetes, presence of fever and sepsis, foci of infection, outcomes and type of culture specimens were extracted from the hospital’s record system. Sepsis is defined in accordance with the International Guidelines for the Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021 [24]. Six isolates of B. pseudomallei obtained from these cases underwent whole genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Statistical analysis

In order to asses risk factors or clinical presentations associated with melioidosis mortality, a logistic regression was conducted with outcome death and predictors demographic data, comorbid factors, and clinical presentations (presence of sepsis, fever, lung, and skin and soft tissue as infection foci) of 41 patients with complete data. All variables with p ≤ 0.1 in univariate logistic regression were included in multivariable logistic regression analysis. The final multivariable model used the backward elimination approach, in which variables that had the least significant effect on the model were removed. The crude odds ratio (OR) and adjusted OR (aOR) were calculated during univariate and multivariable modelling, respectively, together with the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All tests were two-sided and P value <0.050 considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v28.

Whole genome sequencing of B. pseudomallei isolates

Genomic DNA was extracted from purified colonies of B. pseudomallei using the Torax Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (Torax Biosciences Ltd., Newtownabbey, United Kingdom). The identification of the bacteria was confirmed using a real-time PCR assay that targeted a specific 115-bp segment within the type three secretion system 1 (TTS1) gene of B. pseudomallei [25]. Whole genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) at the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF), generating paired-end reads of 150 bp for each genome. Accession numbers for the six genomes are SAMN37878278 to SAMN37878283 (bioproject PRJNA1029745, SRA SRS19194652 to 7).

Multi-locus sequence types (MLST) were assigned in silico using the MLST assignment tool “mlst” (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) [26] and the PubMLST website (https://pubmlst.org/) [27]. Genomes were assembled de novo using shovill 1.1.0 which is based on SPAdes, with minimum length of 1,000 bp and default settings to correct sequencing errors and adaptors (https://github.com/tseemann/shovill) [28]. Average coverage was 128 reads. A core genome alignment was conducted on the six B. pseudomallei genomes from this study and 121 publicly available, global B. pseudomallei genomes (S1 Table) resulting in 163,182 core genome single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). This is with using the default settings of Snippy v4.6.0 [29] and the closed B. pseudomallei genome K96243 as reference (N50 4,074,542 bp; 2 contigs; size 7,247,547 bp, NC_006351.1 and NC_006350.1) [30]. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was generated in IQ-TREE v2.2.0.3 [31] using the nucleotide substitution model TVM+F+I+I+R5 selected by the ModelFinder and lowest BIC score [32] and the final tree was rooted using MSHR668 which was the most ancestral B. pseudomallei strain in a large phylogenetic study of B. pseudomallei from across the world and closely related Burkholderia species [33]. Bootstrapping was performed using 1,000 replicates (.tre file of consensus tree in S1 File). The tree was visualized using Ggtree v3.6.1 in R v4.1.2 (https://www.r-project.org/) [34]. The sequences of geographical and virulence genetic markers lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Yersinia-like fimbrial / Burkholderia thailandensis-like flagella and chemotaxis gene cluster (YLF/BTFC), Burkholderia intracellular motility A (bimA) gene and filamentous hemagglutinin (fhaB3) gene were extracted in silico using SRST2 v0.2.0 (https://github.com/katholt/srst2/tree/master) [35]: LPS A (wbil to apaH [location: 3196645–3215231] in K96243 [GenBank ref: NC_006350]), LPS B (BUC_3392 to apaH [location: 499502–535038] in B. pseudomallei 579 [GenBank ref: NZ_ACCE01000003]), LPS B2 (BURP840_LPSb01 to BURP840_LPSb21 [location: 241–26545] in B. pseudomallei MSHR840 [GenBank ref: GU574442]), BTFC (BURPS668_A0209 in B. pseudomallei MSHR668 [GenBank ref: CP000571.1]), YLF (BPSS0124 in B. pseudomallei K96243 [GenBank ref: NC_006350]), bimABm (BURPS668_A2118 in B. pseudomallei MSHR668 [GenBank ref: CP000571.1]), bimABp (BPSS1492 in B. pseudomallei K96243 [GenBank ref: NC_006350]) and fhaB3 (BPSS2053 in B. pseudomallei K96243 [GenBank ref: NC_006350]) [36].

Results

Demographics, clinical manifestations, risk factors, and outcomes of patients

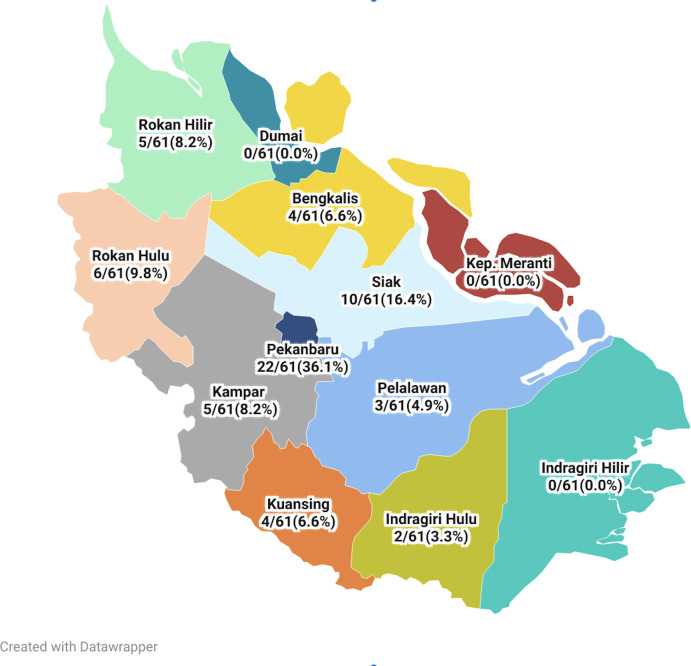

Between 2009 and 2021, a total of 68 patients with positive B. pseudomallei culture results were identified, with 35 patients from Arifin Achmad Hospital and 33 from Eka Hospital Pekanbaru. The patients originated from 9 out of 11 districts in Riau Province, with the commonest being Pekanbaru 26 patients (38.2%), followed by Siak 11 patients (16.2%), Rokan Hulu 7 patients (10.3%), Rokan Hilir 4 patients (5.9%) and others 20 patients (29.4%) (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Map of Riau Province and the distribution of patient residences (https://www.datawrapper.de/_/lNhtk/).

Due to retrospective data collection and one of the hospitals not utilizing electronic medical records, complete data for all variables were only obtained for 41 out of 68 patients. Subsequent data analysis was conducted on the 41 patients with complete data. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics, risk factors, clinical manifestations, patient outcomes, and the source of patient culture specimens. Among the patients with data available, the majority were male (85%), and 28% of patients were between 41–60 years of age (mean age 49.1) (SD 11.5) (Table 1). The distribution of cases was similar between the dry (49%) and rainy (51%) seasons. The most commonly identified risk factor was diabetes mellitus, affecting 32/41 patients (78%). Fever was reported in 27/41 cases (66%), while sepsis was documented in 22/41 cases (51%). The most frequently observed focal infection was in the lungs, affecting 16/41 cases (39%). The mortality rate from melioidosis was 41% (17/41 cases).

Table 1. Demographics, risk factors, clinical manifestations and patient outcomes.

| Variables | Complete sample |

|---|---|

| (n = 41) | |

| Demographics | |

| Male | 35 (85%) |

| Age, years (mean [SD]) | 49.1 (11.5) |

| Age, years | |

| 0–10 | 0 (0%) |

| 11–20 | 2 (5%) |

| 21–30 | 0 (0%) |

| 31–40 | 5 (12%) |

| 41–50 | 14 (34%) |

| 51–60 | 14 (34%) |

| 61–70 | 6 (15%) |

| 71–80 | 0 (0%) |

| Hospital admission | |

| Dry season (March-August) | 20 (49%) |

| Rainy Season (September-February) | 21 (51%) |

| Risk factors | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (78%) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection | 0 (0%) |

| Hazardous alcohol use | 1 (2%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (24%) |

| Chronic lung disease | 2 (5%) |

| Clinical manifestation | |

| Primary focus of infection | |

| Lungs | 16 (39%) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 8 (20%) |

| No evidence focal infection | 7 (17%) |

| Bone and joint | 2 (5%) |

| Lymph nodes | 3 (7%) |

| Central nervous system | 2 (5%) |

| Ear | 1 (2%) |

| Dental | 1 (2%) |

| Pericardial | 1 (2%) |

| Fever | 27 (66%) |

| Sepsis | 21 (51%) |

| Bacteremia | 21 (51%) |

| Outcome | |

| Recovered | 24 (59%) |

| Death from melioidosis | 17 (41%) |

| Specimen origin of B.pseudomallei isolate | |

| Blood | 21 (51%) |

| Pus | 13 (32%) |

| Sputum | 7 (17%) |

Univariate analysis found that sepsis (OR: 4.00; 95% CI: 1.06–15.14, p = 0.037), lung as a primary focus of infection (OR: 4.29; 95% CI: 1.13–16.31, p = 0.029), and bacteremia (OR: 11.33; 95% CI: 2.46–52.15, p<0.001) were associated with death (Table 2). In a multivariable model, lung as a focal infection (aOR: 6.43; 95% CI: 1.13–36.59, p = 0.036) and bacteremia (aOR: 15.21; 95% CI: 2.59–89.31, p = 0.003) were significantly associated with death (Table 2).

Table 2. Risk factors for mortality of melioidosis.

| Variable | Outcome | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death (n = 17) n (%) |

Recovered (n = 24) n (%) |

OR (95% CI) | P-value | aOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Sex Male Female |

15 (88%) 2 (12%) |

20 (83%) 4 (17%) |

1.50 (0.24–9.30) | 1.000 | ||

| Age > = 50 years | 9 (53%) | 13 (54%) | 0.95 (0.27–3.31) | 0.938 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (82%) | 18 (75%) | 1.56 (0.33–7.34) | 0.711 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (24%) | 6 (25%) | 0.92 (0.22–3.95) | 1.000 | ||

| Fever | 11 (65%) | 16 (67%) | 0.92 (0.25–3.39) | 0.896 | ||

| Sepsis | 12 (71%) | 9 (38%) | 4.00 (1.06–15.14) | 0.037* | ||

| Lung as primary focus of infection | 10 (59%) | 6 (25%) | 4.29 (1.13–16.31) | 0.029* | 6.43 (1.13–36.59) | 0.036* |

| Skin and soft tissue as primary focus of infection | 2 (12%) | 6 (25%) | 0.40 (0.07–2.28) | 0.433 | ||

| Bacteremia | 14 (82.4%) | 7 (29.2%) | 11.33 (2.46–52.15) | <0.001* | 15.21 (2.59–89.31) | 0.003* |

*significance at p = 0.05

OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Bacterial genomics and phylogenetic analysis

There were 6 isolates that were retrieved and available for WGS examination, originating from 5 patients. Isolates R6 and R9 originated from the same patient, with an interval between the two episodes of 4 months, and the patient did not receive oral eradication therapy, suggesting the likelihood of a relapse infection [37] (Table 3). MLST analysis revealed three STs, consisting of ST1794 (n = 3), ST46 (n = 2), and ST289 (n = 1). ST1794 is a novel isolate and has to date only been detected in Indonesia. Two isolates of ST1794 originated from the patient with relapsed melioidosis, and this patient and the other with ST1794 both came from the same district, Siak. All six genomes contained the YLF, LPS type B and Bp bimA markers. With the exception of R2, all isolates also contained the fhaB3 gene (Table 4).

Table 3. B. pseudomallei strains included in this study: Patient and clinical presentation details.

| Isolate | Patient | Hospital | Age (year) | Sex | Isolate date | Outcome | Primary focus of infection | Sepsis | Specimen | Resident |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 1 | EH | 48 | Male | 14 Nov 2019 | Recovered | Skin and soft tissue | Yes | Blood | Pekanbaru |

| R3 | 2 | EH | 52 | Female | 26 Dec 2019 | Recovered | CNS | No | Pus subdural | Siak |

| R6 | 3 | EH | 62 | Male | 19 May 2020 | Recovered | Lung | Yes | Sputum | Siak |

| R9 | 3 | EH | 62 | Male | 4 Jan 2020 | Recovered | Lung | No | Sputum | Siak |

| R10 | 4 | AA | 50 | Male | 30 Nov 2020 | Death | Skin and soft tissue | No | Pus chest wall | Rokan Hilir |

| R11 | 5 | EH | 40 | Male | 16 Feb 2021 | Recovered | Lung | Yes | Blood | Siak |

Table 4. B. pseudomallei strains included in this study: Geographical and genetic markers.

| Isolate | MLST | YLF-BTFC | LPS | bimA | fhaB3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 46 | YLF | A | Bp | Negative |

| R3 | 1794 | YLF | A | Bp | Positive |

| R6 | 1794 | YLF | A | Bp | Positive |

| R9 | 1794 | YLF | A | Bp | Positive |

| R10 | 46 | YLF | A | Bp | Positive |

| R11 | 289 | YLF | A | Bp | Positive |

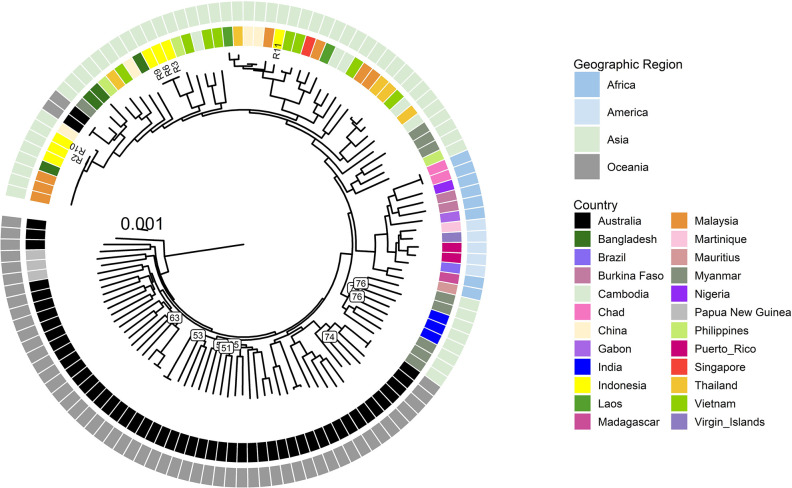

The phylogenetic analysis showed a clear clustering of the Indonesian B. pseudomallei genomes with B. pseudomallei genomes from other Asian countries (Fig 2). ST46 isolates R2 and R10 were closely related with each other (21 core SNPs difference) and other ST46 isolates from Malaysia and Bangladesh. R6 and R9 from the same patient had no core SNPs, confirming this was a relapsed infection. There was a difference of 12 SNPs between R3 and R6, both from patients with ST 1794 B. pseudomallei who lived in the same district. In contrast, there were 13,560 and 12,180 SNPs’ difference between the Indonesian isolates from different nodes and with different STs, such as R9 compared to R11 or R9 compared to R2. In comparison, there was a difference of 17,200 SNPs between R2 and an African isolate and 17,890 SNPs between R2 and an Australian B. pseudomallei genome.

Fig 2. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of B. pseudomallei from Riau (n = 6) with a global set of genomes (n = 121) and 163,182 core genome SNPs.

The scale bar indicates substitutions per site. Bootstrap support (using 1,000 replicates) for branches below 80% are shown revealing some deeper nodes with lower support while all main nodes were well supported.

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to report epidemiological and clinical data on melioidosis from a specific region in Indonesia and to include bacterial genomic analysis. Our findings showed that the demographic characteristics, including gender and age, of melioidosis patients in this region of Indonesia, are similar to previous studies conducted in Indonesia and other countries such as Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, China, and Australia. [22,38–42].

In Riau Province, the frequency of melioidosis cases during the dry and rainy seasons was nearly equal. This contrasts with northern Australia where the rainy season is a strong independent risk factor for melioidosis, with cases linked to rainfall in the two weeks before the onset of symptoms [43]. In Hainan, China, melioidosis cases peaked in August and September, coinciding with the rainy season, with the peak year being the one with the highest rainfall [41]. B. pseudomallei has been found in both, shallow and deeper soil levels [6]. During the rainy season these bacteria can proliferate and move to the surface, possibly due to aerotaxis [44,45]. The rainy season can therefore lead to increased exposure of individuals to muddy soil and water containing B. pseudomallei [44,45]. Data from the Riau Province Central Statistics Office indicates that there is a consistent pattern of both moderate and high rainfall throughout the entire year, in contrast to the Northern Territory of Australia which has a “wet-dry tropics” climate. Further investigation is necessary to examine the correlation between melioidosis occurrences and the fluctuating rainfall patterns in the Riau province, both within the year and between years.

The most common risk factor identified in this study was diabetes mellitus (DM) (78%). Approximately 80% of melioidosis patients have risk factors, including DM, hazardous alcohol consumption, and chronic lung disease [30,46]. In previous studies conducted in Indonesia, DM was the most prevalent risk factor, albeit with a lower percentage of 36% [22]. DM is also a major risk factor for melioidosis in Malaysia, China, and Australia [40–42]. DM impairs the immune system by suppressing chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and cytokine response to bacterial killing, thereby increasing the risk of infection [47]. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) are critical components of the innate immune response against B. pseudomallei [47]. However, the PMN response and the release of chemokines for IL-8 activation are delayed in DM [47]. Considering that Indonesia ranks fifth globally in terms of the number of DM cases, with 19.5 million estimated patients in 2021, proper identification and comprehensive management of melioidosis cases are crucial [48].

The most frequently reported clinical symptom among the patients in this study was fever (66%). In Singapore, fever was present in 81% of melioidosis cases (39). The most common presenting focus of infection observed was the lungs (39%). In previous research in Indonesia, the lungs were found to be the primary focus in 25% of cases [22]. These results from Indonesia are lower rates of pneumonia than seen in studies from Malaysia, Australia, and China, where pneumonia accounted for 41%, 52%, and 54% of presentations, respectively [40–42]. The lower rates of pneumonia from Indonesia may reflect ascertainment issues in data collection from the relatively small number of cases and further prospective studies are now required in Indonesia. The potential for aerosol spread of B. pseudomallei during the rainy season, possibly caused by rainfall during strong winds, may contribute to pneumonia as the most common symptom [44]. In this study, sepsis was recorded for 51% cases. In Kelantan, Malaysia, hospitalized patients with melioidosis had sepsis 69%, severe sepsis in 26%, and septic shock in 34% [40]. In the Darwin prospective melioidosis study 21% melioidosis cases had strictly defined septic shock [42].

The melioidosis mortality rate in Riau Province, according to this study, was 41% which is similar to reported 43% in a previous study in Indonesia [22], higher than reported from Malaysia (33%) and China (23%) [40,41]. Melioidosis death rates have declined from over 50% to under 10% in some other regions of the world [42]. However, numerous areas where melioidosis is prevalent still lack access to essential laboratory and treatment facilities, with severe resource limitations [15]. In this study, sepsis, lung as focus of infection and bacteremia were identified as risk factors for mortality due to melioidosis. This was consistent with other studies, showing that sepsis [49] and bacteremia [50] are strongly linked to mortality in melioidosis.

When we commenced this study, there was only a single record of B. pseudomallei from humans in Indonesia available in the international Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) database (https://pubmlst.org/bpseudomallei). WGS analysis showed a large genetic variability of the Indonesian genomes suggesting that B. pseudomallei has been established in Riau province for a long time. ST 46 is the most common isolate in Southeast Asia, with more than 150 records on the MLST website and was seen in three of our patients. ST289 is also seen in other Southeast Asian countries and was found in one patient in our study. We found a new MSLT type 1794 in three different patients. WGS also showed that all Riau province isolates contained the geographical marker LPS type A which is the most common LPS type in Thailand and Australia [51], as well as the YLF cluster which is widespread in Southeast Asia [52]. R2 was the only fhaB3 negative isolate and of interest, R2 was from a patient with cutaneous melioidosis. The absence of fhaB3 has been associated with localized skin lesions [53]. All isolates also contained the Bp bimA gene allele which is the more abundant allele in Southeast Asia [53]. The alternate bimA gene allele, Bm bimA, has been associated with neurological disease [54].

There are several limitations that should be acknowledged in this study. Firstly, the identification of B. pseudomallei for the majority of isolates was conducted using a phenotypic approach without genotypic confirmation. Only six isolates in this study were genetically confirmed as B. pseudomallei. The second limitation pertains to the completeness of the clinical data. Although efforts were made to collect comprehensive clinical information, there were remaining data gaps in this retrospective study.

Conclusion

The data collected in this study provides a valuable snapshot of the clinical presentation and mortality rate of melioidosis in a specific area of Indonesia. This disease is more commonly observed in males, typically impacting middle-aged individuals, with diabetes mellitus being the predominant risk factor. The lungs are the commonest site of infection. The mortality rate is notably high, comparable to that in some other developing nations. The WGS analysis effectively differentiates the genomes of B. pseudomallei in Indonesia from the ancestral Australian B. pseudomallei, clearly placing Indonesian B. pseudomallei within the Asian B. pseudomallei clade. It is expected that melioidosis may exist in many other regions of Indonesia, and this potential will be unmasked with the enhancement of laboratory capabilities and the widespread adoption of standardized guidelines for investigating suspected melioidosis cases. Further studies and WGS of larger and more geographically dispersed collections of B. pseudomallei are now needed to expand the understanding of the epidemiology of melioidosis and the phylogeography of B. pseudomallei across Indonesia.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(TRE)

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Arifin Achmad Hospital and Eka Hospital Pekanbaru for their collaboration and support. We would like to extend our appreciation to the Menzies School of Health Research for conducting and analyzing the WGS.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by DIPA Universitas Riau (DA,DR,IY). Grant number LPPM-UNRI/2023/KOM//1567/28. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript. Sponsor or funder's website https://lppm.unri.ac.id.

References

- 1.Kaestli M, Schmid M, Mayo M, Rothballer M, Harrington G, Richardson L, et al. Out of the ground: Aerial and exotic habitats of the melioidosis bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei in grasses in Australia: Burkholderia pseudomallei in grasses in Australia. Environ Microbiol. 2012. Aug;14(8):2058–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limmathurotsakul D, Wuthiekanun V, Chantratita N, Wongsuvan G, Amornchai P, Day NPJ, et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei is spatially distributed in soil in northeast Thailand. Carabin H, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010. Jun 1;4(6):e694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meumann EM, Limmathurotsakul D, Dunachie SJ, Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ. Burkholderia pseudomallei and melioidosis. Nat Rev Microbiol [Internet]. 2023. Oct 4 [cited 2023 Dec 8]; Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-023-00972-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie BJ, Jacups SP, Cheng AC, Fisher DA, Anstey NM, Huffam SE, et al. Melioidosis epidemiology and risk factors from a prospective whole-population study in northern Australia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004. Nov;9(11):1167–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Limmathurotsakul D, Kanoksil M, Wuthiekanun V, Kitphati R, deStavola B, Day NPJ, et al. Activities of daily living associated with acquisition of melioidosis in northeast Thailand: A matched case-control study. Small PLC, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013. Feb 21;7(2):e2072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PS, Chen YS, Lin HH, Liu PJ, Ni WF, Hsueh PT, et al. Airborne transmission of melioidosis to humans from environmental aerosols contaminated with B. pseudomallei. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015. Jun;9(6):e0003834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limmathurotsakul D, Wongsuvan G, Aanensen D, Ngamwilai S, Saiprom N, Rongkard P, et al. Melioidosis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei in drinking water, Thailand, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014. Feb;20(2):265–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas AD, Forbes-Faulkner JC. Persistence of Pseudomonas pseudomallei in soil. Aust Vet J. 1981. Nov;57(11):535–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wuthiekanun V, Smith MD, White NJ. Survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in the absence of nutrients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995. Sep;89(5):491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pumpuang A, Chantratita N, Wikraiphat C, Saiprom N, Day NPJ, Peacock SJ, et al. Survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in distilled water for 16 years. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011. Oct;105(10):598–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willcocks SJ, Denman CC, Atkins HS, Wren BW. Intracellular replication of the well-armed pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016. Feb;29:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moule MG, Spink N, Willcocks S, Lim J, Guerra-Assunção JA, Cia F, et al. Characterization of new virulence factors involved in the intracellular growth and survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Camilli A, editor. Infect Immun. 2016. Mar;84(3):701–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweizer HP. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei: Implications for treatment of melioidosis. Future Microbiol. 2012. Dec;7(12):1389–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dance D. Treatment and prophylaxis of melioidosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014. Apr;43(4):310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currie BJ. Melioidosis and Burkholderia pseudomallei: Progress in epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and vaccination. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022. Dec;35(6):517–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan RP, Marshall CS, Anstey NM, Ward L, Currie BJ. 2020. Review and revision of the 2015 Darwin melioidosis treatment guideline; paradigm drift not shift. Dunachie SJ, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Sep 28;14(9):e0008659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warner J, Rush C. Tropical fever in remote tropics: Tuberculosis or melioidosis, it depends on the lab. Microbiol Aust. 2021. Nov 12;42(4):173–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birnie E, Virk HS, Savelkoel J, Spijker R, Bertherat E, Dance DAB, et al. Global burden of melioidosis in 2015: A systematic review and data synthesis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. Aug;19(8):892–902. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30157-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savelkoel J, Dance DAB, Currie BJ, Limmathurotsakul D, Wiersinga WJ. A call to action: Time to recognise melioidosis as a neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022. Jun;22(6):e176–82. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00394-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limmathurotsakul D, Golding N, Dance DAB, Messina JP, Pigott DM, Moyes CL, et al. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat Microbiol. 2016. Jan 11;1(1):15008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tauran PM, Sennang N, Rusli B, Wiersinga WJ, Dance D, Arif M, et al. Emergence of Melioidosis in Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015. Dec 9;93(6):1160–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tauran P, Wahyunie S, Saad F, Dahesihdewi A, Graciella M, Muhammad M, et al. Emergence of melioidosis in Indonesia and today’s challenges. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018. Mar 13;3(1):32. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3010032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mboi N, Syailendrawati R, Ostroff SM, Elyazar IR, Glenn SD, Rachmawati T, et al. The state of health in Indonesia’s provinces, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2022 Nov;10(11):e1632–45. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00371-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021. Nov;49(11):e1063–143. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novak RT, Glass MB, Gee JE, Gal D, Mayo MJ, Currie BJ, et al. Development and evaluation of a real-time PCR assay targeting the type III secretion system of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2006. Jan;44(1):85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seemann T, mlst Github https://github.com/tseemann/mlst.

- 27.Jolley KA, Maiden MC. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010. Dec;11(1):595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seemann T [cited 8 August 2023] https://github.com/tseemann/shovill. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seemann T. Snippy: Rapid haploid variant calling and core genome alignment [Internet]. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy.git [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holden MTG, Titball RW, Peacock SJ, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Atkins T, Crossman LC, et al. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004. Sep 28;101(39):14240–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: A Fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015. Jan;32(1):268–74. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017. Jun;14(6):587–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price EP, Currie BJ, Sarovich DS. Genomic insights into the melioidosis pathogen, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2017. Sep;4(3):95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu G. Using ggtree to Visualize Data on Tree-Like Structures. Curr Protoc Bioinforma [Internet]. 2020. Mar [cited 2023 Aug 8];69(1). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com doi: 10.1002/cpbi.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.https://github.com/katholt/srst2/tree/master.

- 36.Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven LA, Schultz MB, Pope BJ, Tomita T, et al. SRST2: Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med. 2014. Dec;6(11):90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Limmathurotsakul D, Chaowagul W, Chantratita N, Wuthiekanun V, Biaklang M, Tumapa S, et al. A simple scoring system to differentiate between relapse and re-infection in patients with recurrent melioidosis. Currie B, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008. Oct 29;2(10):e327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wongratanacheewin S, Day NPJ, Teerawattanasook N, Chaowagul W, Limmathurotsakul D, Chaisuksant S, et al. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010. Jun 1;82(6):1113–7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chien JMF, Saffari SE, Tan AL, Tan TT. Factors affecting clinical outcomes in the management of melioidosis in Singapore: A 16-year case series. BMC Infect Dis. 2018. Dec;18(1):482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zueter A, Yean CY, Abumarzouq M, Rahman ZA, Deris ZZ, Harun A. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis in a teaching hospital in a North-Eastern state of Malaysia: A fifteen-year review. BMC Infect Dis. 2016. Dec;16(1):333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng X, Xia Q, Xia L, Li W. Endemic melioidosis in southern China: Past and present. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019. Feb 25;4(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Currie BJ, Mayo M, Ward LM, Kaestli M, Meumann EM, Webb JR, et al. The Darwin prospective melioidosis study: A 30-year prospective, observational investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021. Dec;21(12):1737–46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00022-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaestli M, Grist EPM, Ward L, Hill A, Mayo M, Currie BJ. The association of melioidosis with climatic factors in Darwin, Australia: A 23-year time-series analysis. J Infect. 2016. Jun;72(6):687–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiersinga WJ, Virk HS, Torres AG, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ, Dance DAB, et al. Melioidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2018. Feb 1;4(1):17107. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprague LD, Neubauer H. Melioidosis in animals: A review on Epizootiology, diagnosis and clinical presentation. J Vet Med Ser B. 2004. Sep;51(7):305–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DiOrio MS, Elrod MG, Bower WA, Benoit TJ, Blaney DD, Gee JE, et al. Fatal Burkholderia pseudomallei infection initially reported as a bacillus species, Ohio, 2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014. Oct 1;91(4):743–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gassiep I, Armstrong M, Norton R. Human melioidosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020. Mar 18;33(2):e00006–19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.IDF Diabetes Atlas 2021 10th ed [cited 2023 Aug 8]. International Diabetes Federation [Internet].2021. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resource-files/2021/07/IDFAtlas_10th_Edition_2021.pdf. [PubMed]

- 49.Raj S, Sistla S, Sadanandan DM, Kadhiravan T, Rameesh BMS, Amalnath D. Clinical Profile and predictors of mortality among patients with melioidosis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2023;15(2):72–8. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_134_22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mardhiah K, Wan-Arfah N, Naing NN, Hassan MRA, Chan HK. The cox model of predicting mortality among melioidosis patients in northern Malaysia: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021. Jun 25;100(25):e26160. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webb JR, Win MM, Zin KN, Win KKN, Wah TT, Ashley EA, et al. Myanmar Burkholderia pseudomallei strains are genetically diverse and originate from Asia with phylogenetic evidence of reintroductions from neighbouring countries. Sci Rep. 2020. Oct 1;10(1):16260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tuanyok A, Auerbach RK, Brettin TS, Bruce DC, Munk AC, Detter JC, et al. A horizontal gene transfer event defines two distinct groups within Burkholderia pseudomallei that have dissimilar geographic distributions. J Bacteriol. 2007. Dec 15;189(24):9044–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarovich DS, Price EP, Webb JR, Ward LM, Voutsinos MY, Tuanyok A, et al. Variable virulence factors in Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis) associated with human disease. Morici LA, editor. PLoS ONE. 2014. Mar 11;9(3):e91682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gora H, Hasan T, Smith S, Wilson I, Mayo M, Woerle C, et al. Melioidosis of the central nervous system; impact of the bimA Bm allele on patient presentation and outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2022. Feb 7;ciac111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(TRE)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.