Neck immobilisation is vital in patients with suspected cervical spine injuries and generally involves applying a hard cervical collar—usually by ambulance crew, nurses, or junior doctors. We present the case of a patient with ankylosing spondylitis who sustained a cervical fracture but had no cord injury initially. He became quadriplegic after a hard collar was applied in the emergency department, and he subsequently died.

Case report

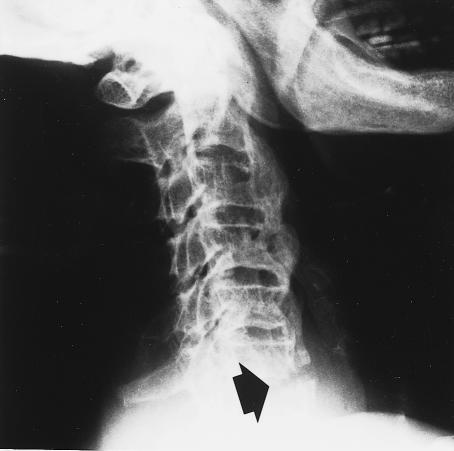

An 82 year old man fell down some stairs. He walked into the emergency department, without cervical immobilisation, complaining of neck pain. He had longstanding spinal stiffness and, because of a fixed flexion deformity of his neck, his line of vision was only a few paces ahead. There was tenderness over the spinous processes of C6 and C7, but no neurological abnormality in his limbs or sphincter disturbance were noted. Radiographs of the cervical spine showed ossification across the intervertebral discs at several levels, suggesting ankylosing spondylitis, and a fracture of the inferior plate of C6, but vertebral alignment was acceptable (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Radiographs taken on admission to the accident and emergency department showed spondylitis, fracture of the inferior endplate at C6 (arrow), and soft tissue swelling anterior to the fracture

The patient’s neck was then manipulated to a neutral position, despite his normal fixed flexion deformity, and a hard cervical collar of the appropriate size was applied. This procedure increased his neck pain and caused paraesthesia, followed by quadriplegia, laboured breathing, hypotension, and bradycardia. The man was intubated, ventilated, and transferred to our neurosurgical intensive care unit.

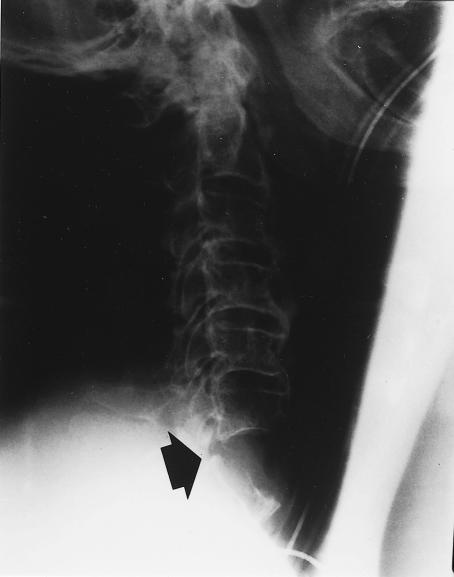

Radiographs of the cervical spine, taken when the patient arrived in intensive care wearing the neck collar, showed widening of the fracture, with angulation of the spine between C6 and C7 (fig 2). The collar was removed and the neck was flexed to reduce the fracture. The patient required large doses of noradrenaline to maintain his blood pressure. He developed pneumonia, renal failure, cardiac dysrhythmia, and myocardial infarction and died two days after admission to our unit.

Figure 2.

Lateral cervical spine with hard collar in situ, showing angulation of spine at fracture site (arrow)

Discussion

Ankylosing spondylitis is a generalised chronic inflammatory disease, the effects of which are seen mainly in the spine and sacroiliac joints.1 The cervical spine develops a fixed flexion deformity, and, after trauma to the cervical spine, spinal cord damage most commonly occurs between C5 and C7.2,3 The normally elastic ligaments of the spine, which limit displacement in trauma to the neck, are calcified in ankylosing spondylitis and are usually involved in the fracture. This renders such a fracture particularly unstable, similar to a fracture of a long bone.

According to the guidelines for advanced trauma life support, the simplest way of safeguarding the spinal cord is by limiting neck movements with a hard collar.4 However, hard collars may increase cerebrospinal fluid pressure,5 cause skin ulceration,6 reduce tidal volume,7 and cause dysphagia.8 Application of a hard cervical collar to a patient with ankylosing spondylitis has been reported to cause paraesthesia.9 We now report that this manoeuvre may also cause quadriplegia. The dangers of immobilising the cervical spine in an inappropriate position in patients with ankylosing spondylitis may not be appreciated by junior doctors working outside specialist units.

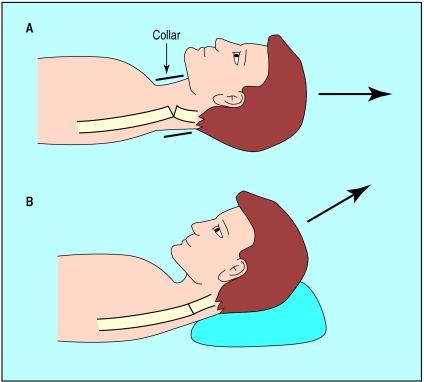

Great care should be exercised if there is a history of ankylosing spondylitis or a fixed flexion deformity of the cervical spine, or if the cervical spine radiographs are available and the patient is neurologically intact before the hard collar is fitted. If the usual alignment of the cervical spine is kyphotic, then the neck should not be immobilised in the neutral position but should be supported with sandbags on either side of the head and under the occiput to achieve neck flexion (fig 3). A halo brace should be applied rather than a hard collar. As a general rule, if the patient resists attempts to move the neck into a neutral position, the manoeuvre must be abandoned and urgent advice sought from a neurosurgical unit.

Figure 3.

Applying a hard collar to a patient with major cervical kyphosis and a fracture of the cervical spine (above) angulates the fracture and causes cord injury; immobilisation in flexion by placing sandbags under the occiput (below) reduces the fracture and prevents cord damage

Application of a hard collar may move the cervical spine into an unsatisfactory position and damage the spinal cord in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.9 This may also be the case in patients with rheumatoid arthritis10 and in children.11

References

- 1.Apley AG, Solomon L. Apley’s system of orthopaedics and fractures. 7th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995. pp. 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surin VV. Fractures of the cervical spine in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:79–84. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young JS, Cheshire DJE, Pierce JA, Vivian JM. Cervical ankylosis with acute spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1977;15:133–146. doi: 10.1038/sc.1977.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Advanced trauma life support for doctors. Student manual. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raphael JH, Chotai R. Effects of the cervical collar on cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:437–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb03482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt S. Skin necrosis caused by a semi-rigid cervical collar in a ventilated patient with multiple injuries. Injury. 1994;25:323–324. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(94)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd FM, Simon E, McKeown D, Patrick MR. The effect of a cervical collar on the tidal volume of anaesthetised adult patients. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:961–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb05928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton DJ, Curley JW. Dysphagia caused by a hard cervical collar. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:501–502. doi: 10.1080/02688699647168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podolsky SM, Hoffman JR, Pietrafesa CA. Neurologic complications following immobilization of cervical spine fracture in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:578–580. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(83)80305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Althoff B, Goldie IF. Cervical collars in rheumatoid atlanto-axial subluxation: a radiographic comparison. Ann Rheum Dis. 1980;39:485–489. doi: 10.1136/ard.39.5.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curran C, Dietrich AM, Bowman MJ, Ginn-Pease ME, King DR, Kosnik E. Pediatric cervical-spine immobilization: achieving neutral position? J Trauma. 1995;39:729–732. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199510000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]