We began this series by arguing that the private finance initiative, far from being a new source of funding for NHS infrastructure, is a financing mechanism that greatly increases the cost to the taxpayer of NHS capital development.1 The second paper showed that the justification for the higher costs of the private finance initiative—the transfer of risk to the private sector—was not borne out by the evidence.2 The third paper showed the impact of these higher costs at local level on the revenue budgets of NHS trusts and health authorities, is to distort planning decisions and to reduce planned staffing and service levels.3

All this raises questions about the direction of government policy on the NHS. Recent government commitments to increase clinical staffing levels and reverse the decline in bed capacity sit uneasily with a policy that seems to lead in the opposite direction. The government has consistently argued that the private finance initiative is no more than a procurement policy, with no implications for services other than increased efficiency. However, this ignores the importance of public-private partnerships to the government’s overall agenda.

Summary points

The private finance initiative does not provide new money for public services as the government claims

The high costs of capital under the private finance initiative translates into service and workforce cuts

The reduction in public provision of long term care, NHS dentistry, optical services, and elective surgical care shows the trajectory for the NHS under the private finance initiative

In the NHS, shrinkage in service provision combined with budget constraints could force primary care trusts to redefine entitlement to NHS care and to seek privately funded solutions for those who can afford to pay, leaving a rump service

The private finance initiative is a regressive instrument and is likely to increase inequalities in health and in wealth

The private finance initiative, as an explicit move towards the private provision of public services, is central to government policy. The Cabinet Office white paper states: “Distinctions between services delivered by the public and the private sector are breaking down in many areas, opening up the way to new ideas, partnerships and opportunities for devising and delivering what the public wants.”4 The private finance initiative in the NHS is part of a wider policy agenda affecting all government departments. The aim, according to the European Union, is to produce major savings in public spending and to create fresh opportunities for private business.5 In this paper we look at the justifications for this policy and identify some of the possible consequences across the NHS for the public, the workforce, and patients.

National and international dimensions

The third wave of private finance initiative hospital schemes brings planned private sector investment in the health service to around £3.1 billion.6 This greatly exceeds new government capital for the NHS over the same period. The private finance initiative in health is part of a broader government strategy to substitute private capital for government borrowing.

The private finance initiative and public-private partnerships are also expected to play a key role in modernising infrastructure where underinvestment has created a backlog of maintenance—estimated at £6bn in schools, universities, and hospitals alone. By the end of this year, the private finance initiative and public-private partnerships will account for 14% of overall public sector investment.7 The chancellor of the exchequer’s comprehensive spending review shows that planned private finance initiative investment for the four years 1998-9 to 2001-2 is £2.35bn for health; £3.62bn for environment, transport, and the regions; £1.08bn for defence; and £13.1bn for the public sector as a whole.8

The new public services agreements which departments were obliged to produce as part of the comprehensive spending review process further reinforces the new role of the private sector; the Department of Health committed itself to “modernise the service in partnership with the private sector, by ensuring that patients and clients have access to suitable facilities and can benefit from new technologies.”

The use of public-private partnerships is an international phenomenon promoted by global financial institutions. Public-private partnerships are being applied throughout the world and are known variously as design, build, finance, and operate (DBFO); build, own, operate, and transfer (BOOT); and build, operate, and transfer (BOT) schemes. These differ chiefly in the ultimate ownership of the underlying asset. Private finance for public services is integral to the structural adjustment programmes imposed by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank and a prerequisite for loans to developing countries.9 Both promote the use of “markets in infrastructure provision,”10 and the World Bank has adjusted its methods for appraising investment to make this easier. The World Trade Organisation’s “government procurement agreement” came into force in 1996 for a number of states, including those in the European Union, and opened up public contracts to international competition. Britain has been among the first states in the developed world to take up two key recommendations of the global financial institutions designed to facilitate the transfer of public services to private sector provision: commercial accounting and commercial investment appraisal.11 In our first paper we showed how the former, in the form of NHS capital charges, was a precondition of introducing public-private partnerships into the health service (capital charging or accrual accounting is now being extended to all government departments),1 and our second paper argued that the use by government of commercial investment appraisal techniques has distorted the estimation of the costs of the private finance initiative.2

Over the past six years the European Commission has advocated the use of public-private partnerships and has used government grants to set them up.12 In public-private partnerships the private sector provides services and the public sector purchases and funds them.13 Some of the largest projects are for transport, bridges, ports, water, and sewerage.14 This market was worth more than 720 billion ecus in 1994 (11.5% of the gross national product of the 15 member states of the European Union). The number of notices in the Official Journal of the European Community announcing large procurement projects has risen from 12 000 in 1987 to about 200 000 in mid-1999.

Justifying the cost

Efficiency gains from risk transfer

The European Investment Bank has acknowledged that public-private partnership is a more expensive form of infrastructure development than traditional procurement. In these circumstances, according to the bank, “The principal value for governments is the anticipated gains in management associated with the transfer of risk.”15 The policy rests largely on the claim that the private sector, by being less averse to risk, will structure projects so that they are managed more efficiently. Although the British government justifies the private finance initiative in similar terms, risk transfer remains unlikely in practice because private contractors seek whenever possible to protect their income from uncertainty.2 The penalties built into the system do not ensure efficiency of public services because they do not provide the public with alternative services in the event of failure of the private sector, as the privatised railways show.16

The recent crisis over private finance schemes for the new national insurance and passport agency computer systems (with private sector partners Siemens and Andersen Consulting) illustrate the problems. The Public Accounts Committee notes that the government’s refusal to fine the contractors “would result in the risk purportedly transferred to Andersen Consulting under the PFI contract being transferred back to the public sector.”17 This negates the key justification for the higher costs of the private finance initiative—the transfer of risk and the “efficiency” of the private sector. A major problem is that the financial information on which to judge the transfer of risk and the validity of the contracts has not been placed in the public domain. The proposed freedom of information legislation will not address this since information can still be withheld on the grounds of commercial confidentiality.

Reduced public expenditure?

The Treaty of Maastricht requires “greater public sector restraint and budgetary discipline, emphasising the need for increased efficiency in spending on economic and social infrastructure.”12 One of the justifications for public-private partnerships is that they reduce government borrowing. But Britain’s current economic performance is well within the Maastricht treaty’s criteria for public debt and deficit convergence on which continued membership of the European Union depends.

Bringing in new sources of funding

The only way in which the use of private finance can actually reduce government expenditure is through the creation of new income streams from sources other than taxation in order to fund returns to the private investors. European infrastructure policy, for example, has been linked to the ability to introduce or increase user charges.18 When new sources of funding are introduced in this way, investment can, in principle, take place without a corresponding increase in public debt or in corporate taxation necessary to fund it. The investment costs are shifted from society in general to the users of public services.

Creating the conditions for alternative funding

It is politically difficult to create alternative sources of funding within the NHS, which is funded almost entirely from general taxation and is free at the point of delivery. Alternative sources of funding that could be used to fund returns to investors do not exist. Cash can only be released by cutting services or by moving services to sectors where partial funding and user charges are practicable, or by redefining public services as private goods. Preventive, rehabilitation, mental health, disability, and long term care services continue to be withdrawn from the range of services available within the NHS, as does routine elective care.19 The experience of long term care is instructive here.

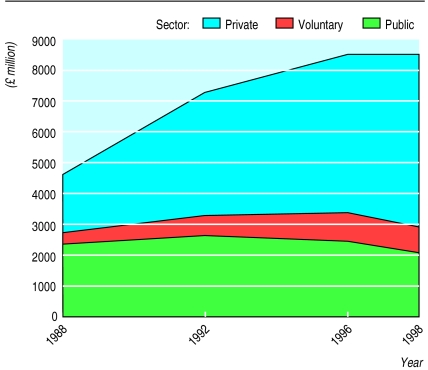

Throughout the 1980s the government used the social security budget to facilitate the reprovision of public long term care by the private sector in nursing and residential care homes (table 1).20 The shrinkage of public (NHS and local authority) provision combined with spending constraints allowed the NHS and local authorities to redefine their responsibilities for funding and provision of long term care.21 The implementation of the NHS and Community Care Act 1990 devolved the responsibility for long term care to local authorities and extended the scope to increase user charges through a means tested system.22 The guidance that followed the act required the NHS to introduce stringent eligibility criteria, known as continuing care criteria, to ration access to the much reduced long term care sector in the NHS. Since 1979 there has been a reduction of more than 100 000 long term care beds in the NHS. In 1979 the proportion of places in the private long term care sector was 18% (around 33 000). By 1998 the for-profit private long term care sector had 70% of the total market, and was now providing institutional care to more than 360 000 people (figure). Although one third of people in long term care are self funded, the remaining 71% are state funded: 50% by local authorities, 17% by income support under preserved rights, and 4% by the NHS. Recipients of local authority funding become financially eligible only after they have spent down their resources.23

Table 1.

Long term care market, 1998

| Sector | No of places | £ million |

|---|---|---|

| Private sector | 385 000 | 5 342 |

| Voluntary sector | 71 500 | 1 029 |

| Public sector: | 104 400 | 2 103 |

| NHS long stay geriatric care | 24 800 | 682 |

| NHS care of elderly mentally ill | 13 900 | 381 |

| NHS care of younger physically disabled | 1 600 | 45 |

| Local authority care of elderly and younger physically disabled | 64 100 | 995 |

| Non-residential care | 3 965 | |

| Total | 560 900 | 12 439 |

In long term care the private sector’s preference for accumulating assets and capital has meant the diversion of public funds to the acquisition and construction of assets owned and run by the private sector (tables 1 and 2). The emphasis on return on capital has fuelled the expansion in institutional private care provision at the expense of independent living and community care, and the numbers of households and people over 65 in receipt of community based services has fallen.24 It has also affected staffing levels. Within the acute NHS hospital sector (even with the pressures of technology and drug treatments) some 62% of revenue costs go on labour25; in the private acute hospital sector less than 40% of income goes on labour.26 Long term care is traditionally a labour intensive sector: staff costs account for 66% of NHS income for mental health and community services. In the top 10 private long term care companies, staff costs are less than 55% of income (see table on website). In the NHS, the average annual wage costs for community and mental health staff are £20 000 and £21 000 respectively. In the private sector employees’ average earnings are less than £8000 a year. The long term care sector is characterised by the use of non-unionised and casual workers. In 1996, care home assistants were among the 10 lowest paid occupations in Britain, with average rates of pay below £4 an hour.27 The top 10 long term care companies had operating profits as high as 28% of income in 1997. Ashbourn/Sun made an operating profit of £228m in 1997 (see table 3 and website). The former nationalised utilities tell the same story: profits for shareholders have been at the expense of jobs and wages in the labour force (see table 3).

Table 2.

Top 10 private providers of long term care in the United Kingdom, 1997

| Provider | No of beds | Employees’ average annual wage (£) | Profit/loss before tax (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashbourn/Sun | 8 343 | 6 900 | −3 |

| WHC | 5 972 | 6 600 | 12 |

| Tamaris | 5 628 | 7 000 | 3 |

| Cragemoor | 4 130 | 6 100 | 5 |

| Cresta Care | 3 642 | 6 700 | 5 |

| Highfield Group | 3 318 | NA | NA |

| ANS | 3 144 | 7 400 | 2 |

| Southern Cross | 2 652 | 3 200 | −1 |

| Advantage Healthcare | 2 911 | NA | NA |

BUPA=British Union Provident Association; WHC=Westminster Health Care; ANS=Associated Nursing Services; NA=not available.

1996 figures.

Table 3.

Changes in employment and dividends in former nationalised utilities since privatisation

| Period | No (%) change in employment (whole time equivalents) | Dividends (£m) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Gas | 1987-95 | −33 675 (−38) | 4354 |

| British Telecom | 1998-95 | −89 000 (−38) | 6745 |

| Water companies (10) | 1990-5 | −3 082 (−8) | 6862 |

| Electricity generation | 1992-6 | −8 996 (−43) | 1262 |

| Railtrack | 1996-9 | −520 (−5) | 434 |

Despite the obvious implications for cost and quality of care, the government remains committed to having the private sector continue to deliver services for the most vulnerable people in society. Health Minister Paul Boateng, at a conference in April 1998 on inter-agency collaboration, said that “the days when a local authority could get away with an approach to residential care which was always to prefer their own provision before that of the private sector are dead and gone and will not be tolerated,” and he went on to say: “Indeed if a local authority seeks persistently to undermine the private sector, that local authority will answer for it.”28 The political commitment to private business also informs the recent NHS Act 1999.

Creating business opportunities in health care

Primary care groups and trusts

The private finance initiative has to be seen within the wider context of NHS organisational reform. The newly created primary care groups in England and Wales and the newly established primary care trusts in Scotland will hold united budgets for hospital and community health services, prescribing, and general medical services. They will have to manage the consequences of revenue pressure (more than a third of health authorities and acute trusts are in serious financial difficulties) and a shrinking hospital sector. Many primary care trusts will achieve full commercial trust status in the next year or two. But health authorities have, in effect, committed primary care trusts to purchasing acute services from hospitals within the inflexible private finance initiative without a guaranteeing sufficient clinical revenue. How will they manage the budgets and balance the political requirements to limit waiting lists and emergency admissions? General practitioners are independent contractors to the NHS and the primary care trusts that they form will have a greater opportunity, compared with acute trusts and health authorities, to generate income rather than simply shunt costs between health and social services.29

The private sector consortium operating the new private finance initiative hospitals on behalf of the NHS will have commercial freedom to develop non-NHS services. By separating clinical income from budgets for hospital buildings and other services, the private finance initiative facilitates changes in the funding arrangements for the hospital sector such as the introduction of private insurance or private funding.30

Private sector interest

Partnerships are attractive to the private sector only if they are profitable. A new type of corporation almost wholly dependent on government contracts has arisen, providing shareholders with a high rate of return on capital employed. The financial institutions and banks are playing a leading role in the private finance initiative. Of the 12 existing consortiums that bid for the contract to manage the Department of Social Security’s estate, eight were led by banks.31 Norwich Union, which is to invest an initial £100m in a new joint venture to finance public-private partnership programmes with the Mill Group, has signed a contract to build primary care facilities for Bradford Community NHS Trust. A subsidiary of the largest health maintenance organisation in the United States, Columbia/HCA, has already teamed up with PPP (Private Patient Plan), the largest private health insurer in the United Kingdom.

In America in the 1990s hospitals became a growth industry that was especially attractive to entrepreneurs.32 Exporting the managed care business and its health maintenance organisations across the world is part of US foreign policy. Discussions between managed care corporations and British hospitals involved in the private finance initiative have taken place. Known as “the darlings of Wall Street,” the trillion dollar managed care business depends heavily on a mixture of public funding, private health insurance, and user charges.

Conclusion

“Most institutions on the scale of the NHS end not with a bang but with a whimper ... one possible endgame is that the middle classes lose confidence in the service and begin to make other arrangements.”33 The private finance initiative provides the conditions and the mechanisms for reversing the principles that health care should be funded out of general taxation, that public services should remain in public ownership, and that health services should be free at the point of delivery.The NHS has already undergone major redefinition with the redrawing of the boundaries of responsibility for long term care, NHS dentistry, optical services, and routine elective care. The private finance initiative continues this trend across the NHS and all public services. It is being implemented with virtually no public debate.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Market value by sector (£m), 1988-98

Acknowledgments

We thank Stewart Player for his work gathering the data on the long term care market.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

website extra: Sources of data in tables and figure are given on the BMJ’s website www.bmj.com

References

- 1.Gaffney D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. NHS capital expenditure and the private finance initiative—expansion or contraction? BMJ. 1999;319:48–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7201.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaffney D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. PFI in the NHS—is there an economic case? BMJ. 1999;319:116–119. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7202.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollock AM, Dunnigan M, Gaffney D, Price D, Shaoul J. Planning the new NHS: downsizing for the 21st century. BMJ. 1999;319:179–184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabinet Office. Modernising government. London: Stationery Office; 1999. para 2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Commission. Making the most of the opening of public procurement. Brussels: European Commission Directorate General; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Press release 0421. 7 July 1999.

- 7.Milburn A. Chief secretary to the treasury, speech at the private finance initiative transport conference, February 1999. (www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/pub/html/pspeech/cft202999; accessed July 1999.)

- 8.HM Treasury. Modernising public services for Britain—investing in reform. London: Stationery Office; 1998. (Cm 4011.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chussodovsky M. The globalisation of poverty: impacts of IMF and World Bank reforms. London: Zed Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank. World Bank development report 1994: infrastructure for development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton S. Accounting in an accrual world. Public Finance 1999 July 9:20-1.

- 12.European Commission. Government investment in the framework of economic strategy. Brussels: European Commission; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Commission. Public procurement in the European Union: exploring the way forward. Brussels: European Commission Directorate General; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinnock N. Using public private partnerships to develop transport infrastructure. Speech to public private partnerships conference, London, 24 February 1998. (europa.eu.int/en/comm/dg07/speech/sp9837.htm/; accessed July 1999.)

- 15.European Investment Bank. The EIB and public private partnerships. EIB Information. 1998;2:97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaoul J. Manchester: University of Manchester; 1999. Railpolitik: a stakeholder analysis of the railways in Britain. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Committee of Public Accounts. Twenty-third report: getting better value for money from the private finance initiative. London: House of Commons Committee Office; 1999. (HC 583.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fayard A. Paris: European Conference of Ministers of Transport; 1999. Overview of the scope and limitations of public-private partnerships. (Seminar paper.) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker A. Community care: past, present and future. In: Iliffe S, Munro J, editors. Healthy choices, future options for the NHS. London: Lawrence and Wishart; 1997. pp. 178–200. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macfarlane A, Pollock AM. Statistics and the privatisation of NHS and social services. In: Dorling D, Simpson L, editors. Statistics in society. London: Arnold; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrington C, Pollock AM. Decntralisation and privatisation of long term care in the UK and USA. Lancet. 1998;351:1805–1808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townsend P. The structured dependency of the elderly: a creation of social policy in the twentieth century. Ageing and Society. 1981;1:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royal Commission on Long Term Care. With respect to old age. London: Stationery Office; 1999. (Cm 4192-1.) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollock AM. The creeping privatisation of community care. Health Matters. 1995;20:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaoul J. Charging for capital in the NHS trusts: to improve efficiency? Management Accounting Research. 1998;9:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaoul J. NHS trusts—surprise champions of the premier efficiency league? Manchester: Department of Accounting and Finance, University of Manchester; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garner H. Undervalued work, underpaid women: women’s employment in care homes. London: Fawcett; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Community care market news. Laing and Busson Newsletter 1998-9;5.

- 29.Pollock AM. Hospital Doctor and Community GP. 1998. Primary care—from fundholding to health maintenance organisations. July:6-7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollock AM. The American way. Health Services Journal 1998 April 9:28-9.

- 31.National Audit Office. Department of Social Security: the prime project: the transfer of the Department of Social Security estate to the private sector. London: Stationery Office; 1999. (HC 370.) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuttner R. Columbia/HCA and the resurgence of the for-profit hospital business. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith R. The NHS: possibilities for the endgame. BMJ. 1999;318:209–210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.