The message to parents was clear: be afraid. Your family doctor may strike you and your children off the list without rhyme or reason.

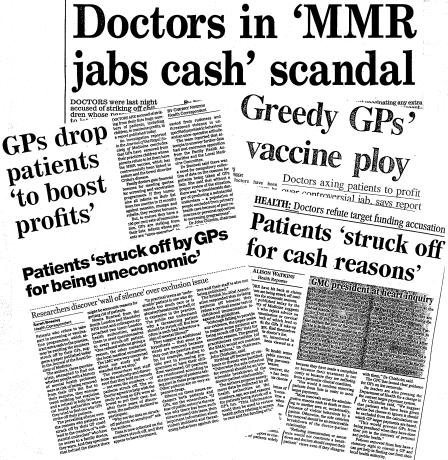

The Daily Mail led the clarion call to arms on Wednesday, 8 September. Next to a picture of a cute blond child and his smiling mother, its large print opening paragraph accused doctors of “striking off children whose parents refuse to let them have the controversial MMR jab.” On 13 September, the Independent told us that doctors were “striking from their lists huge numbers of patients, including children.”

What could possibly drive GPs to such cruelty against the small and defenceless? Lucre of course. The Express headline on 13 September trumpeted its outrage at our “Greedy GPs’ vaccine ploy” and called them “devious doctors.” The Daily Mail announced none other than a full blown “MMR jabs cash scandal.” You could almost picture the masked villains, stethoscopes around their necks, running from their surgeries with bags labelled “swag.”

Like proud detectives unravelling a complex sting operation, all three papers educated their readers about the sordid details of this “trim and win” swindle. GPs were being given “large bonuses” (Daily Mail) for reaching percentage targets for immunisation and screening. To keep these figures high, doctors were removing “uncooperative” parents (the Independent) and “women refusing a smear test” (the Express) from their lists. Had doctors really been caught red handed? Where was the evidence?

The clues could apparently be found in an enigmatic paper called “The struck-off mystery,” in September’s Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (1999;92:443-5). The paper was launched with a dramatic press release that talked of “millions of patients” being struck off each year.

Prompted by their observation during a psychiatric ward round that four out of six patients had been struck off since admission, Dr Neena Buntwal, a senior registrar in psychiatry, and her colleagues at the Bethlem and Royal Free Hospitals, audited 50 patients across their mental health unit. They found that 30% had been removed from their GP’s register at some point and so formulated a hypothesis that “behavioural and psychiatric disorders were a common reason for being struck off.”

Their sleuthing began with a direct appeal, through a local publicity campaign, to patients who had been struck off. The authors hoped to assess psychiatric illness in the members of this group and compare them with controls. Few patients came forward, and many GPs refused to display posters in their waiting rooms. Undeterred, the researchers approached two metropolitan family health authorities, asking them to send questionnaires to all patients who had been struck off their GP’s list. One authority refused to cooperate without giving a reason and the other contacted the local medical committee which demanded that the study be stopped.

After lengthy negotiations, the authority agreed to cooperate provided that GPs were given a chance to explain their actions. Three years after agreeing, the newly restructured local health authority wrote to the authors “stating they had sufficient reservations about our study to decline the release of any further information.” No data on reasons then. Unhelpful? Yes. Intriguing? Most definitely.

Raw data from the health authority show that there has been a three-fold increase in the number of patients removed from lists between 1994 and 1997. Assuming that the population has remained stable, this suggests an increase in the rate of removal, which clearly requires explanation. The authors proffer one version, and here, at last, the fingerprints almost match those of the tabloids: “If some patients are being struck off for economic reasons, this may be a reason why we have found it so difficult to carry out this research.”

Deep within the discussion section lies the source of the media’s panic. Patients on expensive atypical antipsychotic drugs could be financially unattractive to GPs, and there is at least one practice that “restricts its prescribing of antidepressants to tricyclics, openly for cost reasons.” And finally we come to the dastardly deed itself: a single paragraph raises the possibility of monetary gain by removing parents who decline the MMR triple vaccine for their children.

The tabloid furore was graphically illustrated by liberal quotation from this paragraph. The Daily Mail quoted Dr Buntwal as saying, “I have heard some GPs are even taking children off their lists during the age range when they are due to be vaccinated and returning them later.” Not a conclusion that could have been drawn from Dr Buntwal’s study.

Dr John Chisholm, chairman of the BMA’s General Practitioners Committee, tried to reassure the public. He criticised the psychiatrists for “failing to provide any evidence” for their allegations about doctors’ behaviour and rejected the idea of “millions” of patients being struck off, offering a more sobering figure of “one or two removals per GP each year.” Readers were reminded that “the sole criterion for removal should be an irretrievable breakdown of the doctor-patient relationship.”

The true crime, of course, is that health authorities are not obliged to keep data on why patients are being taken off lists. As the authors of the study point out, there may indeed be “a considerable danger of producing a substantial underclass—a population of people excluded from primary health care because of poor resources or personal opposition to screening programmes.” We will never know this without the compulsory collection of data. The lack of information makes for a dreary headline, as does talk of public health and policy. Instead the papers preyed on the anxieties of those who may already be vulnerable—parents worried about vaccination, patients with mental health problems, women who declined cervical smears. The struck off mystery remains just that: we still do not know why patients are being removed from GPs’ lists.